Abstract

Background

One of the main aims of routine antenatal care is to identify the 'at risk' fetus in order to apply clinical interventions which could result in reduced perinatal morbidity and mortality. Doppler ultrasound study of umbilical artery waveforms helps to identify the compromised fetus in 'high‐risk' pregnancies and, therefore, deserves assessment as a screening test in 'low‐risk' pregnancies.

Objectives

To assess the effects on obstetric practice and pregnancy outcome of routine fetal and umbilical Doppler ultrasound in unselected and low‐risk pregnancies.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group Trials Register (28 February 2015) and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials of Doppler ultrasound for the investigation of umbilical and fetal vessels waveforms in unselected pregnancies compared with no Doppler ultrasound. Studies where uterine vessels have been assessed together with fetal and umbilical vessels have been included.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed the studies for inclusion, assessed risk of bias and carried out data extraction. In addition to standard meta‐analysis, the two primary outcomes and five of the secondary outcomes were assessed using GRADE software and methodology.

Main results

We included five trials that recruited 14,624 women, with data analysed for 14,185 women. All trials had adequate allocation concealment, but none had adequate blinding of participants, staff or outcome assessors. Overall and apart from lack of blinding, the risk of bias for the included trials was considered to be low.

Overall, routine fetal and umbilical Doppler ultrasound examination in low‐risk or unselected populations did not result in increased antenatal, obstetric and neonatal interventions. There were no group differences noted for the review's primary outcomes of perinatal death and neonatal morbidity. Results for perinatal death were as follows: (average risk ratio (RR) 0.80, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.35 to 1.83; four studies, 11,183 participants). Only one included trial assessed serious neonatal morbidity and found no evidence of group differences (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.06 to 15.75; one study, 2016 participants).

For the comparison of a single Doppler assessment versus no Doppler, evidence for group differences in perinatal death was detected (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.99; one study, 3891 participants). However, these results are based on a single trial, and we would recommend caution when interpreting this finding.

There was no evidence of group differences for the outcomes of caesarean section, neonatal intensive care admissions or preterm birth less than 37 weeks.

When the quality of the evidence for the main comparison of 'All Doppler versus no Doppler' was assessed with GRADE software, the outcomes of perinatal death and serious neonatal morbidity data were graded as of low quality. Evidence for the outcome of stillbirth was graded according to regimen subgroups ‐ with a moderate quality rating for stillbirth (fetal/umbilical vessels only) and a low quality rating for stillbirth (fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery vessels). Evidence for admission to neonatal intensive care unit was assessed as of moderate quality, and evidence for the outcomes of caesarean section and preterm birth less than 37 weeks was graded as of high quality.

There is no available evidence to assess the effect on substantive long‐term outcomes such as childhood neurodevelopment and no data to assess maternal outcomes, particularly maternal satisfaction.

Authors' conclusions

Existing evidence does not provide conclusive evidence that the use of routine umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound, or combination of umbilical and uterine artery Doppler ultrasound in low‐risk or unselected populations benefits either mother or baby. Future studies should be designed to address small changes in perinatal outcome, and should focus on potentially preventable deaths.

Plain language summary

Doppler ultrasound of fetal blood vessels in normal pregnancies

One of the main aims of routine antenatal care is to identify babies who are not thriving in the womb. It is possible that medical interventions might improve outcomes for these babies, if they can be identified. Doppler ultrasound uses sound waves to detect the movement of blood in vessels. It is used in pregnancy to study blood circulation in the baby, uterus and placenta. Using it in high‐risk pregnancies, where there is concern about the baby's condition, shows benefits. However, its value as a screening tool in all pregnancies needs to be assessed as there is a possibility of unnecessary interventions and adverse effects. The review of trials of routine Doppler ultrasound of the baby’s vessels in pregnancy identified five studies involving more than 14,000 women and babies. The studies were not of high quality and were all undertaken in the 1990s. There were no improvements identified for either the baby or the mother, though more data would be needed to prove whether it is effective or not for improving outcomes.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound.

| All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound | ||||||

| Patient or population: Pregnant women in unselected or low‐risk populations. Settings: Trials took place in Australia, France and the UK. Intervention: All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No Doppler ultrasound | All routine Doppler ultrasound | |||||

| Perinatal death (stillbirth and neonatal death including anomalies) | Study population | RR 0.8 (0.35 to 1.83) | 11183 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 9 per 1000 | 7 per 1000 (3 to 16) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 7 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (2 to 13) | |||||

| Serious neonatal morbidity | Study population | RR 0.99 (0.06 to 15.75) | 2016 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 | ||

| 1 per 1000 | 1 per 1000 (0 to 16) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 1 per 1000 | 1 per 1000 (0 to 16) | |||||

| Stillbirth ‐ Fetal/umbilical vessels only | Study population | RR 0.34 (0.12 to 0.95) | 6877 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | Evlidence for the stillbirth outcome has been graded separately according to subgroup. | |

| 4 per 1000 | 1 per 1000 (0 to 4) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 4 per 1000 | 1 per 1000 (0 to 4) | |||||

| Stillbirth ‐ Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | Study population | RR 1.41 (0.44 to 4.46) | 5276 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,5 | ||

| 6 per 1000 | 9 per 1000 (3 to 27) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 6 per 1000 | 8 per 1000 (3 to 27) | |||||

| Caesarean section (elective and emergency) | Study population | RR 0.98 (0.85 to 1.13) | 6373 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| 108 per 1000 | 106 per 1000 (92 to 122) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 102 per 1000 | 100 per 1000 (87 to 115) | |||||

| Preterm birth (before 37 weeks) | Study population | RR 1.02 (0.86 to 1.21) | 12162 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| 51 per 1000 | 52 per 1000 (44 to 62) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 47 per 1000 | 48 per 1000 (40 to 57) | |||||

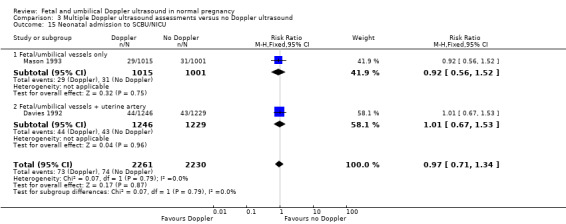

| Neonatal admission to special care baby unit/neonatal intensive care unit | Study population | RR 0.99 (0.84 to 1.17) | 7477 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | ||

| 66 per 1000 | 65 per 1000 (55 to 77) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 35 per 1000 | 35 per 1000 (29 to 41) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 67%). 2 Wide confidence interval crossing the line of no effect. 3 Few events and wide confidence interval crossing the line of no effect (‐2). 4 Most of the pooled effect from a study with design limitations ‐ specifically problems with randomisation. 5 Statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 63%).

Background

Description of the condition

One of the main aims of routine antenatal care is to identify the 'at risk' fetus in order to apply clinical interventions which could result in reduced perinatal morbidity and mortality (RCOG 1997). The routine use of a screening test should be based on proven clinical effectiveness, to avoid subjecting a large group of normal women to anxiety and inappropriate intervention with subsequent risk of iatrogenic morbidity and mortality.

In the majority of cases fetal death can be attributed to a 'known' cause such as maternal disorder (hypertension, diabetes and others), fetal pathology (congenital abnormalities, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR)), placental pathologies or intrapartum complications. The rate of unexplained fetal deaths decreased from 3.5 per 1000 total births in the1960s to 1.1 to 1.9 per 1000 in the 1990s (Chibber 2005; Fretts 1992; Huang 2000). Unrecognised IUGR remains the main cause of unexplained stillbirths in otherwise uncomplicated pregnancies. Two recent studies identified fetal growth restriction in 43% (Gardosi 2005) and 52% (Froen 2004) of unexplained stillbirths, respectively, concluding that IUGR was the strongest risk factor for an unexplained intrauterine death.

It is important to highlight that fetal growth restriction is often confused with the concept of being small‐for‐gestational age. Some fetuses are constitutionally small and they do not have increased perinatal mortality or morbidity. Inability to distinguish easily between small but healthy fetuses and those who are failing to reach their growth potential has hampered attempts to find appropriate treatment for growth restriction (Soothill 1993). Growth‐restricted fetuses are at increased risk of mortality and morbidity (Bernstein 2000; Fisk 2001). The serious morbidity includes intraventricular haemorrhage, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, necrotising enterocolitis, infection, pulmonary haemorrhage, hypothermia and hypoglycaemia (Fisk 2001). Early antenatal detection, treatment where appropriate, and timely delivery could minimise the risks significantly.

Description of the intervention

Doppler ultrasound technology is based on the Doppler shift, a physical principle of the change of ultrasound frequency when aimed at the moving object (e.g. red blood cell) (Campbell 1983; Fitzgerald 1977; Nelson 1988; Owen 2001). Different Doppler methods are used in obstetrics: continuous‐wave, pulsed‐wave, colour and power Doppler flow (Eik‐Nes 1980; Mires 2000).

Doppler ultrasound examination can be performed as a part of a more detailed ultrasound assessment that includes fetal biometry and anatomical survey, or as a separate ultrasound examination.

Flow of the umbilical and fetal arteries is most often quantified either by pulsatility index or resistant index (Burns 1993; Nelson 1988). These indices reflect the down stream vascular resistance by quantifying the differences between the peak systolic and the end‐diastolic velocity within blood vessels of interest in each cardiac cycle. A high ratio in umbilical artery indicates a high vascular impedance and possible feto‐placental compromise. In extreme circumstance the blood flow at the end of diastole may be absent or even reversed.

Initial Doppler studies have been restricted to the umbilical artery, but other fetal vessels have recently become a focus of interest including middle cerebral artery and ductus venosus.

How the intervention might work

Although stillbirths and fetal complications related to placental problems are rare in uncomplicated pregnancy, the impact is devastating. Current methods for the assessment of fetal well‐being and detection of compromised fetus in the routine antenatal care include: symphysis fundal height measurement from the 24th week (Neilson 1998a; NICE 2008), fetal movements charts (Mangesi 2007) and antenatal cardiotocography (Pattison 1999). None of them, however, have proven ability to make an impact on perinatal mortality and morbidity.

Observational and longitudinal studies of Doppler ultrasound in unselected or low‐risk pregnancies have raised doubts about its efficacy and authors have cautioned against its introduction into obstetric practice without supportive evidence from randomised trials (Beattie 1989; Goffinet 1997; Sijoms 1989). The relatively low incidence of preventable adverse perinatal outcomes in low‐risk and unselected populations present a challenge in evaluating the clinical effectiveness of routine Doppler ultrasound, as large numbers are required to provide definitive evidence.

Why it is important to do this review

Any screening test has not only potential for benefit, but also for harm (Barnett 1995). Subjecting a large group of low‐risk patients to a screening test with a relatively high false positive rate is likely to cause anxiety and lead to inappropriate intervention and subsequent risk of iatrogenic morbidity and mortality.

Although epidemiological studies and a Cochrane review have found no correlation between the use of fetal Doppler ultrasound and adverse neurological outcome in childhood development, childhood malignancies and birth weight (Neilson 1998b; Salvesen 2007), some concern about the association between the left‐handedness in males and exposure to Doppler ultrasound has been expressed (Kieler 2001; Kieler 2002; Salvesen 1999).

Considering that no recent studies have been done regarding the fetal exposure to Doppler ultrasound and the fact that the acoustic output of a modern equipment has increased (Barnett 2001; Duck 1991; Henderson 1997) indicates that Doppler ultrasound in obstetrics should be used only if of proven value (in terms of improved outcome, good specificity and sensitivity).

The continuous assessment of the evidence to provide the balanced view of effectiveness, safety and cost‐effectiveness is, therefore, essential. In this review, we will focus on fetal and umbilical Doppler ultrasound in low‐risk and unselected pregnancies. There are other reviews on 'Fetal and umbilical Doppler ultrasound in high‐risk pregnancies' (Alfirevic 2013) and on 'Utero‐placental Doppler ultrasound for improving pregnancy outcome' (Stampalija 2010).

Objectives

To assess the effects of routine fetal and umbilical Doppler ultrasound, or a combination of uterine Doppler ultrasound and umbilical Doppler ultrasound, in unselected and low‐risk pregnancies on obstetric practice and pregnancy.

A low‐risk population is defined as a population where those considered at risk have been excluded. Criteria of 'at risk' are defined variably and this is taken into consideration.

In the context of this review 'unselected' pregnant population refers to a mixture of pregnant women with no identified risk factors and those who may have some risk factors but the trialists have not reported them separately.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials of routine fetal and umbilical Doppler ultrasound, or a combination of uterine Doppler ultrasound and umbilical Doppler ultrasound, in unselected or low‐risk pregnancies. We included quasi‐randomised trials, but planned to undertake sensitivity analysis by trial quality. Had we identified studies that were published as conference abstracts only, we would have tried to contact the authors for further details. We would have included them but undertaken sensitivity analyses of trial quality (see Sensitivity analysis).

Types of participants

Pregnant women in both unselected and low‐risk populations.

Types of interventions

Routine Doppler ultrasound of the fetal and umbilical artery circulation in pregnancy in unselected or low‐risk populations. We included studies that considered the combination of utero‐placental Doppler and fetal or umbilical Doppler in normal pregnancies in this review.

If appropriate, we performed stratified analyses of all outcome measures in the following comparisons:

all routine Doppler versus no Doppler/concealed Doppler examinations (i.e. caregivers not aware of results);

single Doppler measurement versus no Doppler/concealed Doppler examinations;

multiple Doppler measurement versus no Doppler/concealed Doppler examinations.

Types of outcome measures

We selected outcome measures with the help of a proposed core data set of outcome measures (Devane 2007).

Primary outcomes

Perinatal death (stillbirths and neonatal deaths including anomalies)

Serious neonatal morbidity ‐ composite outcome including hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy, intraventricular haemorrhage, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, necrotising enterocolitis

Secondary outcomes

Stillbirth (as defined by trialists)

Neonatal death (all neonatal deaths up to 28 days after birth)

Any death after randomisation (all losses or deaths after randomisation, including miscarriage) (non‐prespecified outcome)

Any potentially preventable perinatal death after randomisation (from 24 weeks and excluding congenital malformations, chromosomal abnormalities and termination of pregnancy)

Fetal acidosis

Apgar score less than seven at five minutes

Caesarean section (both elective and emergency)

Elective caesarean section

Emergency caesarean section

Spontaneous vaginal birth

Operative vaginal birth

Induction of labour

Neonatal resuscitation required

Infant requiring intubation/ventilation

Neonatal fitting/seizures

Preterm birth (before 37 completed weeks of pregnancy)

Infant respiratory distress syndrome

Meconium aspiration

Neonatal admission to special care or intensive care unit, or both

Infant birthweight

Gestational age at birth

Length of infant hospital stay

Long‐term infant/child neurodevelopmental outcome

Women’s views of care/satisfaction

We have reported non‐prespecified outcomes if we consider them to be important.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (28 February 2015).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

We looked for additional studies in the reference lists of the studies identified.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For the methods used when assessing the trials identified in the previous version of this review, seeAlfirevic 2010.

For this update, we used the following methods when assessing the reports identified by the updated search.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author.

We planned to create a Study flow diagram to map out the number of records identified, included and excluded.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author. Data were entered into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we planned to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s prespecified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias [See table 8.5c in the Handbook]

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we planned to assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. In future updates, we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

For this update the quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach (Schunemann 2009). The following key outcomes for the comparison of 'all routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound' were assessed.

Perinatal death (stillbirths and neonatal deaths including anomalies)

Serious neonatal morbidity

Stillbirth ‐ fetal/umbilical vessels subgroup

Stillbirth ‐ fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery

Caesarean section (elective and emergency)

Preterm birth < 37 weeks

Neonatal admission to Special care baby unit/neonatal intensive care unit

GRADEprofiler (GRADE 2014) was used to import data from Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2014) in order to create a ’Summary of findings’ table. A summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for each of the above outcomes was produced using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference if outcomes had been measured in the same way between trials. We planned to use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

For this update, we have not included any cluster‐randomised trials. If in future updates we identify eligible cluster‐randomised trials, we will include these in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. We will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Handbook [Section 16.3.4 or 16.3.6] using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Cross‐over trials

This is not an appropriate design for this review question.

Other unit of analysis issues

In studies including multiple pregnancies, because of non‐independence, we would have used cluster‐trial methods and consulted a statistician to help with the analyses.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. In future updates, if more eligible studies are included, we will explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, analyses were carried out, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, that is, we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if the I² was greater than 30% and either Tau² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. We explored all outcomes by prespecified subgroups (see below).

Assessment of reporting biases

In future updates, if there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis, we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar.

Where there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary, if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary was treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful, we did not combine trials. Where we used random‐effects analyses, the results were presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We analysed all outcomes by subgroups to explore the clinical difference between regimens of Doppler ultrasound. We considered whether an overall summary was meaningful if substantial heterogeneity was not evident. Where necessary, we used random‐effects analysis to produce the summary.

We carried out the following subgroup analysis for all outcomes in all three comparisons:

Fetal/umbilical Doppler ultrasound only versus fetal/umbilical and uteroplacental Doppler ultrasound.

We assessed subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2014). We reported the results of subgroup analyses quoting the I² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value. Where we found evidence of substantial subgroup differences with a P value of < 0.10, we have reported subtotals only for the outcome in question.

Sensitivity analysis

For this update, we did not perform any sensitivity analysis. In future updates, we will perform sensitivity analysis on the primary outcomes based on trial quality, separating high‐quality trials from trials of lower quality. 'High quality' will, for the purposes of this sensitivity analysis, be defined as a trial having adequate sequence generation and allocation concealment.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search identified 20 publications, of which we have included five studies that recruited 14,624 women, with data analysed for 14,185 women, and 20 meta‐analyses. We have excluded eight studies. For further details of trial characteristics, please refer to the tables of Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

An updated search on 28 February 2015 identified two further reports (Forward 2014; Stoch 2012). These studies were additional reports for the already included Newnham 1993 and were added to the references.

Included studies

The five included studies were all undertaken in the 1990s. Three studies used fetal/umbilical vessels only (French Doppler 1997; Mason 1993; Whittle 1994). Two studies used both uterine vessels and umbilical vessels (Davies 1992; Newnham 1993). One study looked at a single assessment at 28 to 34 weeks (French Doppler 1997), three studies looked at more than one assessment (Davies 1992; Mason 1993; Newnham 1993) and one study had a mixture of some women receiving a single assessment and others more than one assessment (Whittle 1994).

Excluded studies

We excluded five studies because they studied uterine Doppler ultrasound only and not fetal and umbilical Doppler or a combination of uterine plus fetal and umbilical Doppler (Ellwood 1997; Goffinet 2001; Snaith 2006; Subtil 2000; Subtil 2003). These studies will be assessed in a separate review on 'Utero‐placental Doppler ultrasound for improving pregnancy outcome'. We excluded two studies because the previous review authors had tried to contact these authors for information needed for studies to be included and had received no response (Gonsoulin 1991; Schneider 1992). We excluded one study because it had high risk of bias; we needed further information before being able to include it (Scholler 1993).

Risk of bias in included studies

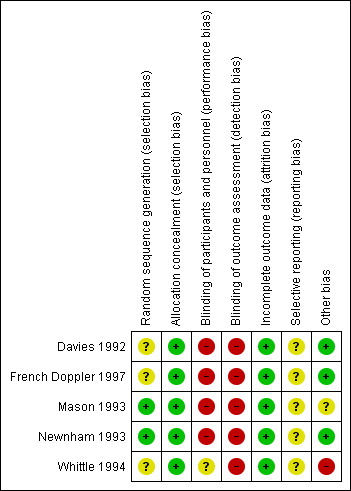

We assessed risk of bias of each included study according to the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2009) and summarised in Figure 1.

1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

Two studies had adequate sequence generation and allocation concealment (Mason 1993; Newnham 1993). Whittle 1994 had adequate allocation concealment but unclear sequence generation; the randomisation process for this trial led to very different group sizes, which the authors attributed to problems with sequence (see the Characteristics of included studies for further detail). Neither Davies 1992 nor French Doppler 1997) described sequence generation, though in both trials, randomisation was conducted in blocks and allocation concealment was adequate.

Blinding

All trials were assessed as of high risk of bias due to lack of blinding of staff and participants. Whittle 1994 was assessed as unclear because only women in the "revealed group had results recorded in the case notes." Staff would have been aware of group assignment for a proportion of women in this trial, but it was unclear if blinding would have functioned for those in the concealed ultrasound group.

All trials were assessed as of high risk of bias due to lack of blinding of outcomes assessors.

Incomplete outcome data

Four studies showed minimal loss of data either by withdrawal after randomisation or by loss to follow‐up less than 6% (Davies 1992; French Doppler 1997; Mason 1993; Newnham 1993). The fifth study reported no loss of outcome data (Whittle 1994).

Selective reporting

Since we did not assess the trial protocols of the included studies, we cannot comment on whether all the prespecified outcomes are reported on. We contacted authors for Newnham 1993 because they mentioned collecting data that were not presented in usable form for this review. We have not had a reply.

Other potential sources of bias

Three studies appeared to be free from other potential biases (Davies 1992; French Doppler 1997; Newnham 1993) and for one study this seemed unclear (Mason 1993). The fifth study was assessed as having high risk of bias in that there was a considerable difference in the numbers of women allocated to the two groups (1642 and 1344), which probably indicates a problem with the randomisation (Whittle 1994). This was discussed and explained by the authors as “...due to secretarial error in preparation of the envelopes ... previously used random numbers had been ‘recycled’ through the study.” This was considered to be a possible high risk of bias in this study.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

1) All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound (five studies, 14,185 women)

Five studies addressed this comparison (Davies 1992; French Doppler 1997; Mason 1993; Newnham 1993; Whittle 1994).

Primary outcomes

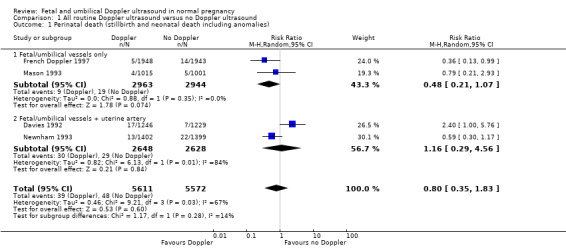

1. Perinatal death (stillbirths and neonatal deaths including anomalies)

Due to the large heterogeneity for this outcome (Tau² = 0.47; Chi² = 9.22, df = 3 (P = 0.03); I² = 67%), we used a random‐effects meta‐analysis. The average risk ratio (RR) across studies was (RR 0.80, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.35 to 1.83); four studies, 11,183 participants, Analysis 1.1), indicating that on average there is no statistically significant reduction identified in the risk of perinatal death when Doppler ultrasound is used. A prediction interval for the underlying relative risk in any future study is also very wide (95% prediction interval = 0.03 to 24.87), reflecting the large heterogeneity identified and the small number of studies.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 1 Perinatal death (stillbirth and neonatal death including anomalies).

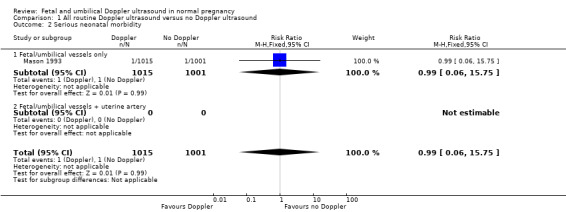

2. Serious neonatal morbidity

Based on a single study, there was no significant difference identified in serious neonatal morbidity (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.06 to 15.75; one study, 2016 participants, Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 2 Serious neonatal morbidity.

Secondary outcomes

We found few significant differences for the whole range of the secondary outcomes (Analysis 1.3 to Analysis 1.20). Subgroup analyses for stillbirth and for potentially preventable perinatal death showed group differences, as described below.

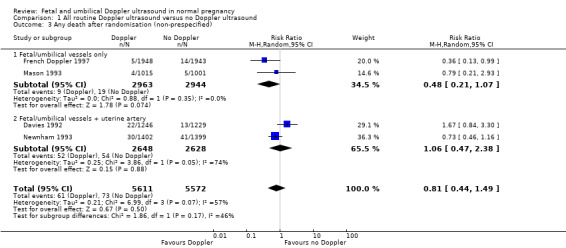

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 3 Any death after randomisation (non‐prespecified).

1.20. Analysis.

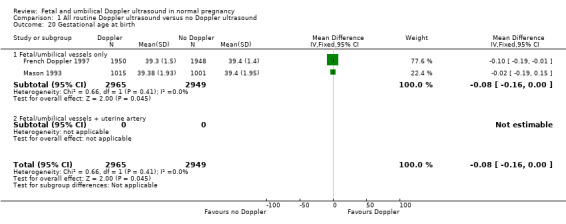

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 20 Gestational age at birth.

These analyses included the following mortality outcomes.

Any death after randomisation (average RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.49; Tau² = 0.25; I² = 74%; four trials, 11,183 participants; Analysis 1.3)

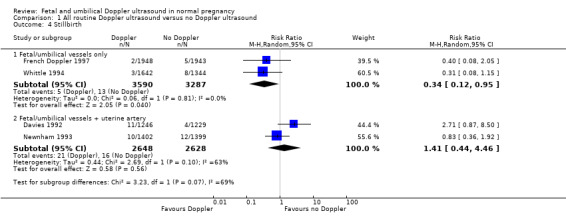

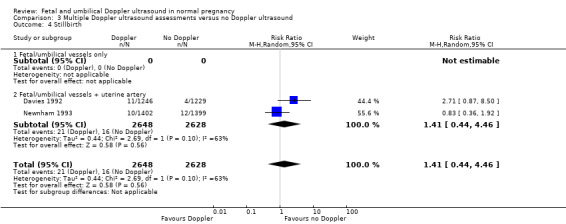

Stillbirth ‐ Data for stillbirth were not pooled because there was evidence of differences between subgroups (Chi² = 3.23, df = 1 (P = 0.07), I² = 69.0%). There could be important clinical differences between women who received different Doppler protocols. Subgroup analysis of fetal/umbilical vessels only showed that Doppler may have improved rates of stillbirth (average RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.95; two trials, 6877 participants), where the subgroup of fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery found no group differences (average RR 1.41, 95% CI 0.44 to 4.46; two trials, 5276 participants; heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.44; I² = 63%; Analysis 1.4)).

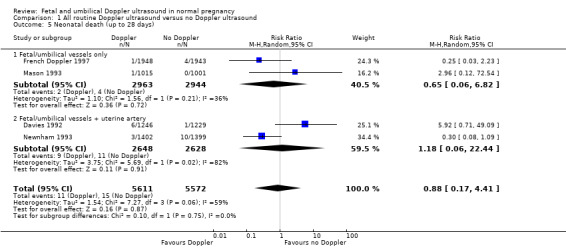

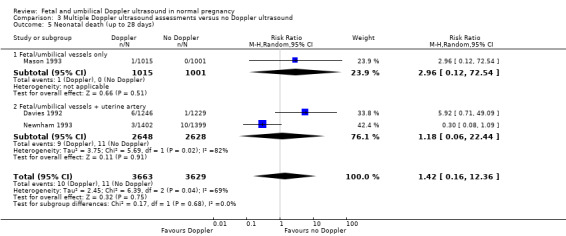

Neonatal death up to 28 days (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.17 to 4.41; four studies, 11,183 participants; heterogeneity: Tau² = 1.54; Chi² = 7.27, df = 3 (P = 0.06); I² = 59%; Analysis 1.5). Two studies assessed fetal vessels only and showed no statistically significant difference (French Doppler 1997; Mason 1993), while two studies using a combination of fetal and utero‐placental Doppler (Davies 1992; Newnham 1993) showed no significant difference and large heterogeneity (Tau² = 3.75; Chi² = 5.69, df = 1 (P = 0.02); I² = 82%; Analysis 1.5).

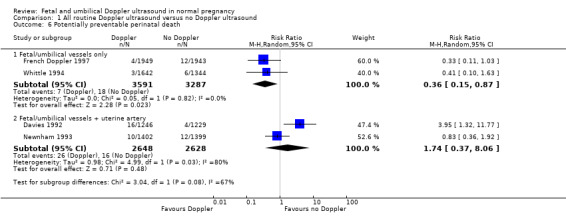

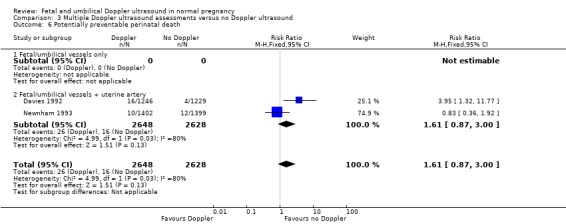

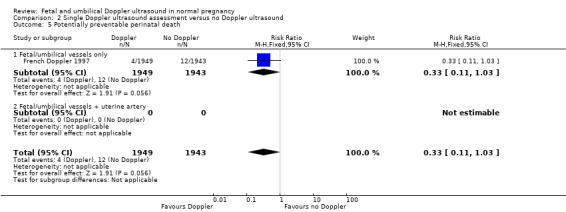

Potentially preventable perinatal death ‐ data for potentially preventable perinatal death were not pooled because there was evidence of subgroup differences (Chi² = 3.04, df = 1 (P = 0.08), I² = 67.1%). There could be important clinical differences between women who received different Doppler protocols. Two trials (French Doppler 1997; Whittle 1994) assessed fetal vessels only (average RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.87, 6878 participants), and for this subgroup the intervention seemed to make a difference. Two other trials ( Davies 1992; Newnham 1993) assessed fetal and the uterine artery and found no group differences (average RR 1.74, 95% CI 0.37 to 8.06; 5276 participants) and high heterogeneity (Tau² = 0.98; I² = 80%; Analysis 1.6).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 4 Stillbirth.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 5 Neonatal death (up to 28 days).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 6 Potentially preventable perinatal death.

There were no significant group differences for any of the remaining secondary outcomes, including the following:

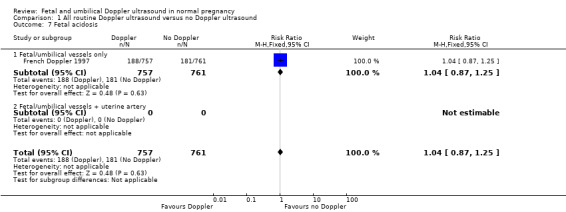

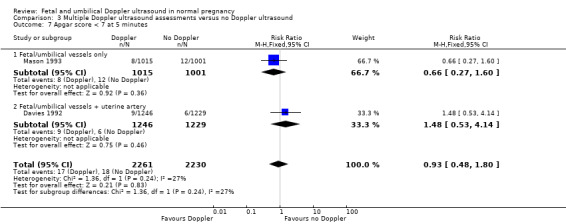

Fetal acidosis (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.25; one study, 1518 participants; Analysis 1.7).

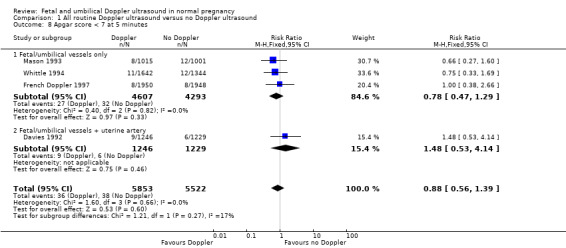

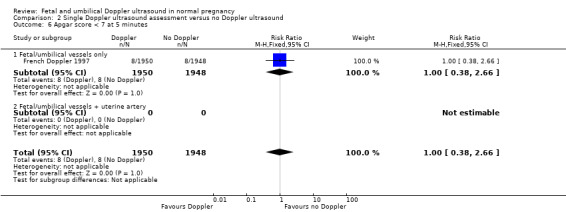

Apgar score less than seven at 5 minutes (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.39; four studies, 11, 375 participants; Analysis 1.8).

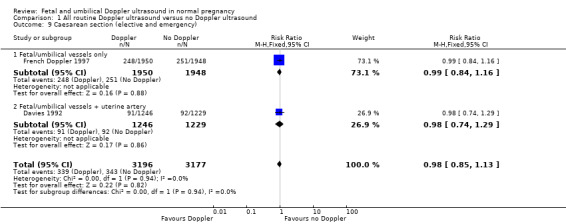

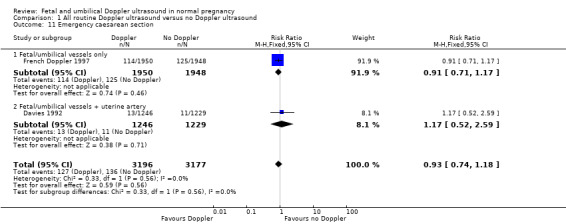

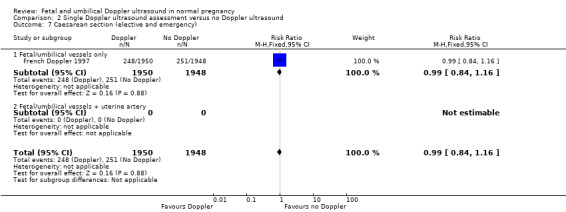

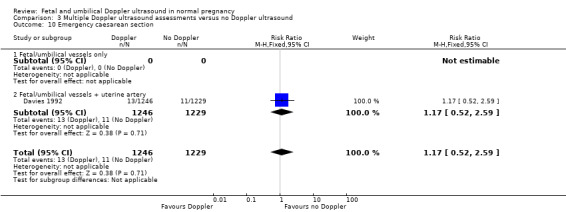

Caesarean section, elective and emergency (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.13; two studies, 6373 participants; Analysis 1.9).

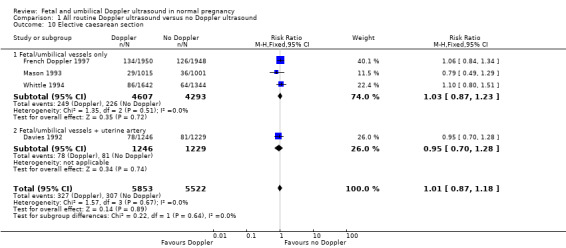

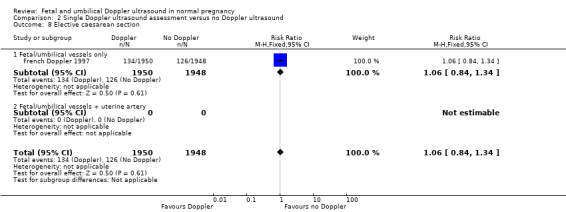

Elective caesarean section (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.18; four studies, 11,375 participants; Analysis 1.10).

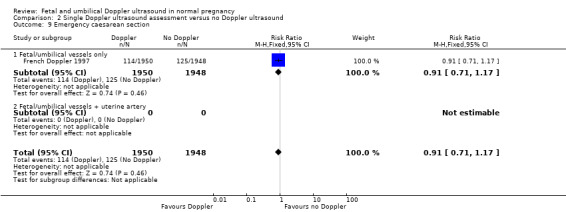

Emergency caesarean section (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.18; two studies, 6373 participants; Analysis 1.11).

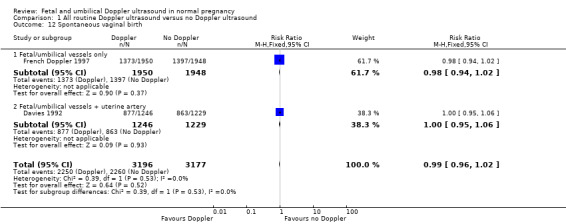

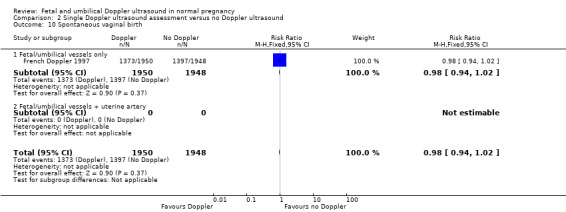

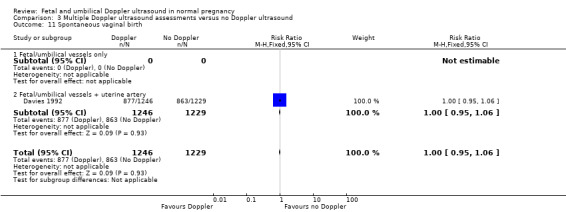

Spontaneous vaginal birth (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.02; two studies, 6373 participants; Analysis 1.12).

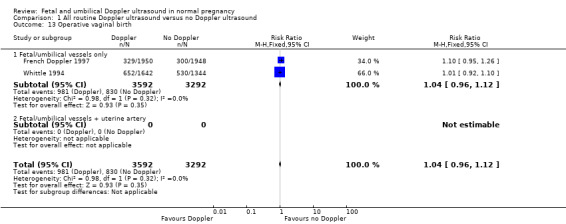

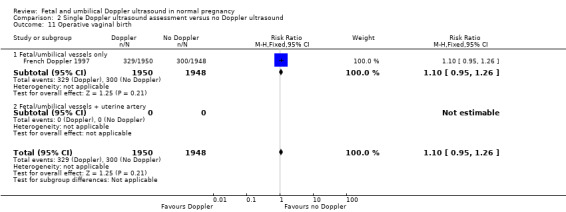

Operative vaginal birth (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.12; two studies, 6884 participants; Analysis 1.13).

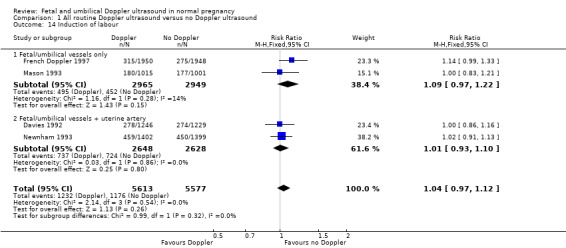

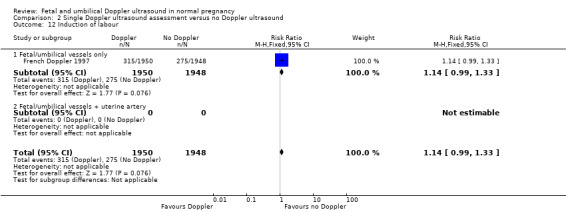

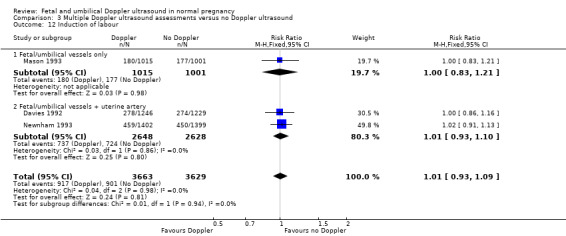

Induction of labour (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.12; four studies 11,190 participants; Analysis 1.14).

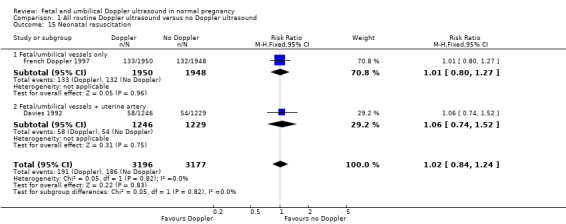

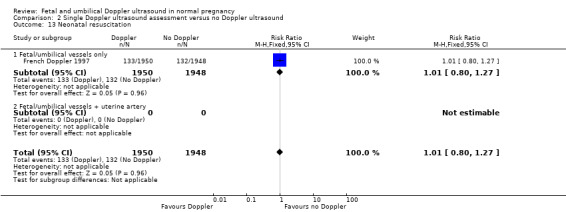

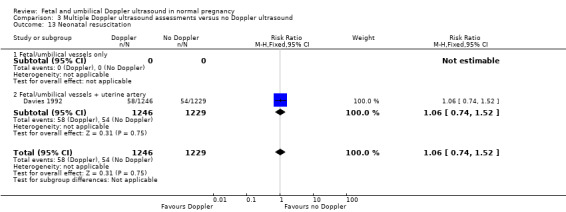

Neonatal resuscitation (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.24; two studies, 6373 participants; Analysis 1.15).

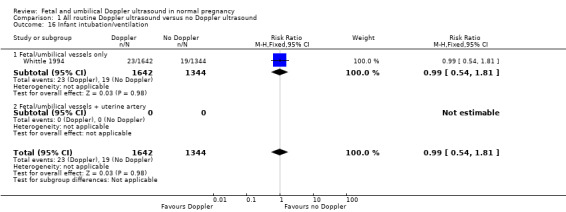

Infant intubation/ventilation (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.81; one study, 2986 participants; Analysis 1.16).

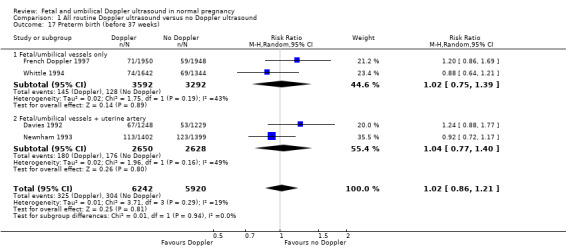

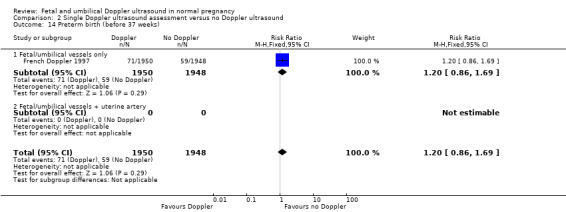

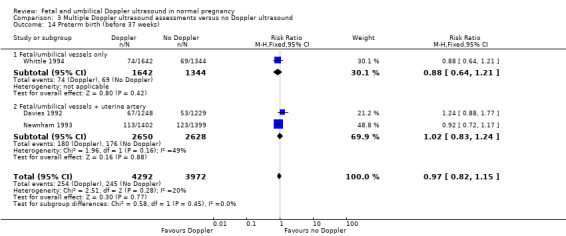

Preterm birth before 37 weeks (average RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.21; four studies, 12,162 participants; Analysis 1.17). Two trials studied fetal vessels only and two additional trials examined the fetal vessels + uterine artery; both subgroups had substantial heterogeneity, but there was no evidence of subgroup differences.

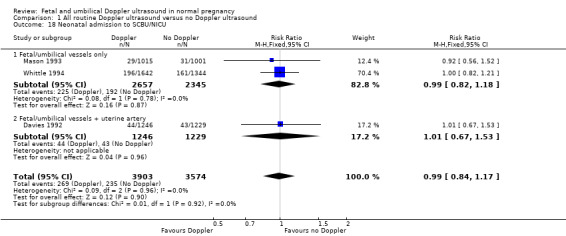

Neonatal admission to special care baby unit/neonatal intensive care unit (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.17; three studies, 7477 participants; Analysis 1.18).

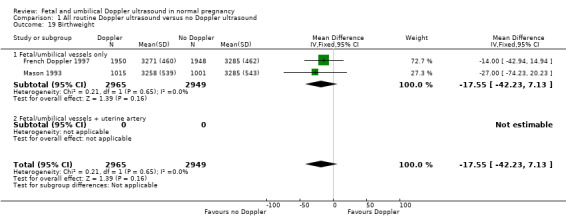

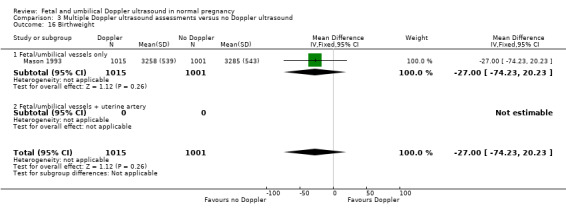

Birthweight (g) (mean difference (MD) ‐17.55, 95% CI ‐42.23 to 7.13; two studies, 5914 participants; Analysis 1.19).

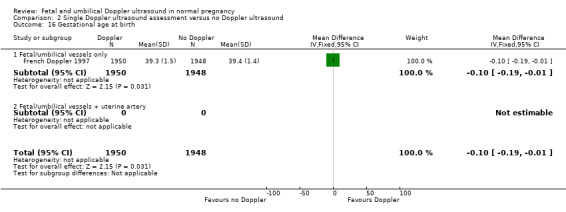

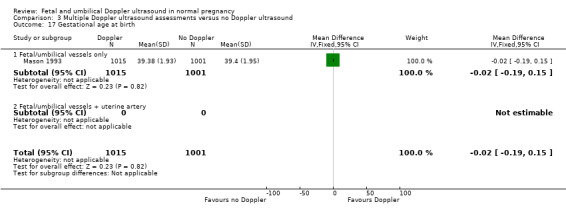

Gestational age at birth (MD ‐0.08, 95% CI ‐0.16 to ‐0.00; two studies, 5914 participants; Analysis 1.20).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 7 Fetal acidosis.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 8 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 9 Caesarean section (elective and emergency).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 10 Elective caesarean section.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 11 Emergency caesarean section.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 12 Spontaneous vaginal birth.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 13 Operative vaginal birth.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 14 Induction of labour.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 15 Neonatal resuscitation.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 16 Infant intubation/ventilation.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 17 Preterm birth (before 37 weeks).

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 18 Neonatal admission to SCBU/NICU.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 19 Birthweight.

None of the included trials in this review reported the outcomes of neonatal seizures/fits, infant respiratory distress syndrome, meconium aspiration, or women's views/satisfaction.

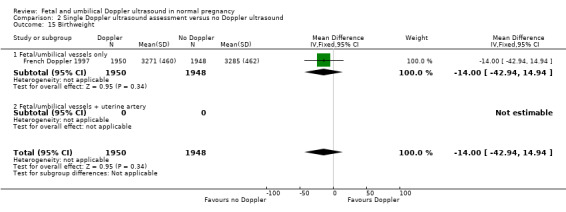

2) Single Doppler ultrasound assessment versus no Doppler ultrasound (one study, 3898 women)

Only one study addressed this comparison (French Doppler 1997).

Primary outcomes

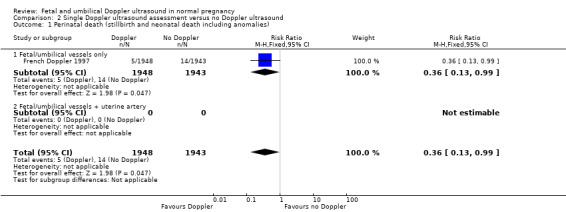

Fewer women in the single Doppler group experienced the outcome of perinatal death (stillbirth and neonatal death including anomalies) (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.99; one study, 3891 participants; Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Single Doppler ultrasound assessment versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 1 Perinatal death (stillbirth and neonatal death including anomalies).

Serious neonatal morbidity was not assessed.

Secondary outcomes

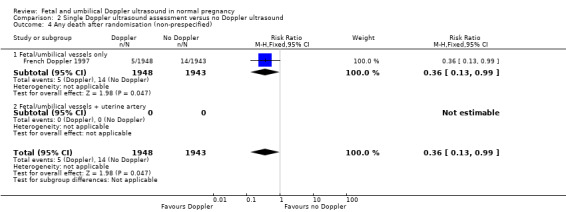

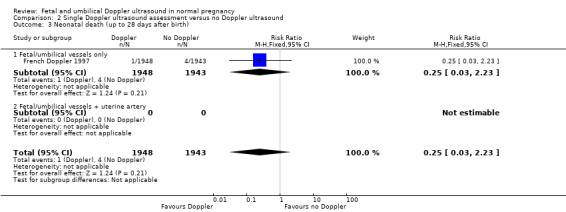

There were significant group differences in rates of any death after randomisation (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.99; one study, 3891 participants; Analysis 2.4).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Single Doppler ultrasound assessment versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 4 Any death after randomisation (non‐prespecified).

There were no statistically significant differences identified in any of the other secondary outcomes that were assessed (Analysis 2.2 to Analysis 2.16).

2.2. Analysis.

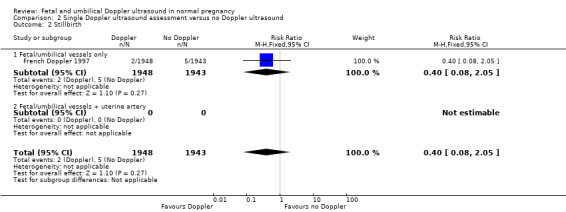

Comparison 2 Single Doppler ultrasound assessment versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 2 Stillbirth.

2.16. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Single Doppler ultrasound assessment versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 16 Gestational age at birth.

This one trial (French Doppler 1997) did not report the outcomes of fetal acidosis, neonatal seizures/fits, infant respiratory distress syndrome, infant requiring intubation/ventilation, meconium aspiration, neonatal admission to special care baby unit/neonatal intensive care unit or women's views/satisfaction.

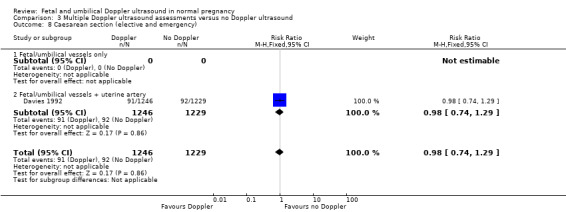

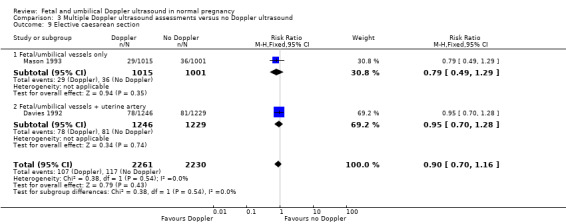

3) Multiple Doppler ultrasound assessments versus no Doppler ultrasound (three studies, 7301 women)

Three studies addressed this comparison (Davies 1992; Mason 1993; Newnham 1993). One study combined the data from women having one assessment and some having more than one assessment (Whittle 1994); these data are only included in Comparison 1 ‐ 'All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler routine ultrasound'.

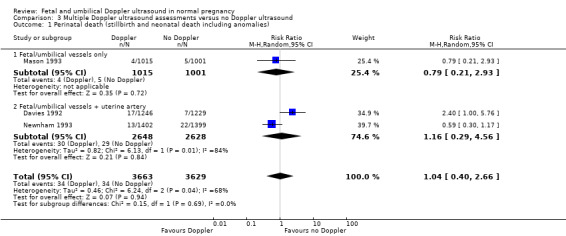

Primary outcomes

For perinatal death, a random‐effects meta‐analysis showed that the average intervention effect across studies was not statistically significant (average RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.40 to 2.66; three studies, 7292 participants; Analysis 3.1). Perinatal deaths showed large heterogeneity (Tau² = 0.46; I² = 68%). The prediction interval for the intervention effect in any future study was extremely wide.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Multiple Doppler ultrasound assessments versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 1 Perinatal death (stillbirth and neonatal death including anomalies).

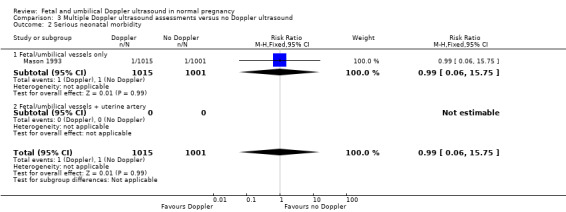

From a single study, Mason 1993, there were no significant group differences for the outcome of serious neonatal morbidity (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.06 to 15.75; one study, 2016 participants; Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Multiple Doppler ultrasound assessments versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 2 Serious neonatal morbidity.

Secondary outcomes

There were no statistically significant group differences for the following mortality outcomes.

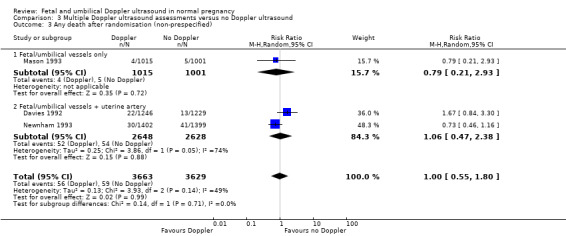

Any death after randomisation (average RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.80; three studies, 7292 participants; Heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.13; I² = 49%; Analysis 3.3).

Stillbirth (average RR 1.41, 95% CI 0.44 to 4.46; two studies, 5276 participants; Heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.44; I² = 63%; Analysis 3.4). Both trials in this analysis examined the fetal vessels + uterine artery.

Neonatal death (average RR 1.42, 95% CI 0.16 to 12.36; three studies, 7292 participants; I² = 69%; Analysis 3.5).

Potential preventable perinatal death (average RR 1.61, 95% CI 0.87 to 3.00; two studies, 5276 participants; heterogeneity: Chi² = 4.99, I² = 80%); Analysis 3.6). Both trials in this analysis examined the fetal vessels + uterine artery.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Multiple Doppler ultrasound assessments versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 3 Any death after randomisation (non‐prespecified).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Multiple Doppler ultrasound assessments versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 4 Stillbirth.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Multiple Doppler ultrasound assessments versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 5 Neonatal death (up to 28 days).

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Multiple Doppler ultrasound assessments versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 6 Potentially preventable perinatal death.

There were no statistically significant differences identified in any of the other secondary outcomes which were assessed (Analysis 3.7 to Analysis 3.17).

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Multiple Doppler ultrasound assessments versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 7 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

3.17. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Multiple Doppler ultrasound assessments versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 17 Gestational age at birth.

The trials did not report the outcomes of fetal acidosis, operative vaginal birth, infant requiring intubation/ventilation, neonatal seizures/fits, infant respiratory distress syndrome, meconium aspiration, or women's views/satisfaction.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review includes data from 14,185 women from five studies (Davies 1992; French Doppler 1997; Mason 1993; Newnham 1993; Whittle 1994). All trials had adequate allocation concealment, but none had adequate blinding of participants, staff or outcome assessors. Overall and apart from lack of blinding, the risk of bias for the included trials was considered to be low.

No differences in perinatal mortality were noted for the main comparison of all Doppler regimens versus no Doppler ultrasound.There were no group differences noted for the review's primary outcomes of perinatal death and neonatal morbidity. Only one included trial assessed serious neonatal morbidity and found no evidence of group differences.

For the main comparison of 'All Doppler versus No Doppler', subgroup analyses according to ultrasound regimen (fetal/umbilical vessels only versus fetal/umbilical vessels and uterine artery) found evidence of group differences for two outcomes. A subgroup of trials (French Doppler 1997; Whittle 1994) that examined fetal/umbilical vessels only showed that Doppler made a difference in the rates of stillbirth. These stillbirth results were not replicated in the subgroup of trials (Davies 1992; Newnham 1993) that considered both fetal/umbilical vessels and the uterine artery. Data for these subgroups were not pooled because there was evidence of subgroup differences. Similarly, a subgroup of two trials (French Doppler 1997; Whittle 1994) that assessed fetal/umbilical vessels only showed a reduction in potentially preventable perinatal death. However, two trials (Davies 1992; Newnham 1993) that assessed fetal vessels and the uterine artery found no evidence for group differences in preventable deaths. Data for potentially preventable perinatal death for all four studies were not pooled again, because there was evidence of subgroup differences. There could be important clinical differences between women who received different Doppler protocols for both of these outcomes. Finally, we would also suggest caution when interpreting these results because these are subgroup analyses of secondary outcomes with few trials per subgroup.

For the comparison of a single Doppler assessment versus no Doppler, significant groups differences in perinatal death were also detected. However, these results are based on a single trial, and we would recommend caution when interpreting this finding. Overall, the number of participants included in analyses in this review remains too small to detect small, but potentially significant changes in perinatal outcome (Chalmers 1989). No differences in perinatal death were found for the final comparison of multiple Doppler assessments versus no Doppler.

The results from Davies for the outcome potentially preventable perinatal death suggest that routine Doppler ultrasound in unselected pregnancies assessing both umbilical and uterine artery Doppler may do more harm than good, but the authors acknowledged that the increase in perinatal deaths was an unexpected finding and may have occurred by chance (Davies 1992). Furthermore, the authors state that the study was not designed to test the ability of routine Doppler ultrasound examinations to reduce perinatal mortality, because a much larger number of participants would need to be included in a such a trial to test this hypothesis.

There was no evidence of group differences for the outcomes of caesarean section, neonatal intensive care admissions or preterm birth less than 37 weeks.

We would like to note that In the Perth study (Newnham 1993), there was an unexpected finding of a greater risk of intrauterine growth restriction in the serial ultrasound and Doppler examination group (i.e. the intensive monitoring group). The authors report, "A written diagnosis of intrauterine growth restriction was observed more frequently in the medical records of women in the intensive group than in the regular group (relative risk 2.07; 95% CI 1.34 to 3.21)," but they do not provide data in a format in which we can include in our review. (We have written to the authors and to the Lancet to try to obtain these data.) The authors state that multiple logistic regression analyses indicated that this was probably not a chance effect, and it is possible that frequent exposure to ultrasound may have influenced fetal growth. This finding was not associated with increased perinatal morbidity and mortality, and follow‐up of these children at one year of age found that the difference in growth was no longer discernible (Newnham 1996). This is, however, a further finding which suggests more harm than good, and the authors stress the need for further investigation of the effects of frequent ultrasound exposure on fetal growth.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Routine fetal and umbilical Doppler ultrasound examination in low‐risk or unselected populations did not result in increased antenatal, obstetric and neonatal interventions, and no overall differences were detected for substantive short‐term clinical outcomes such as perinatal mortality. There is no available evidence to assess the effect on substantive long‐term outcomes such as childhood neurodevelopment and no data to assess maternal outcomes, particularly psychological effects.

Future studies should be designed to address small changes in perinatal outcome, and should focus on potentially preventable deaths

Quality of the evidence

We included five trials that recruited 14,624 women, with data analysed for 14,185 women. All trials had adequate allocation concealment, but none had adequate blinding of participants, staff or outcome assessors. Overall, and apart from lack of blinding, the risk of bias for the included trials was considered to be low. For GRADE assessments, we did not downgrade the evidence for specific outcomes for all trials' lack of blinding.

When evidence quality was assessed with GRADE software, the outcomes of perinatal death and serious neonatal morbidity data were graded as of low quality. Perinatal death was downgraded for heterogeneity and for imprecision, while serious neonatal morbidity was downgraded for imprecision. Evidence for the outcome of stillbirth was graded according to regimen subgroups. We assessed stillbirth (fetal/umbilical vessels only) as of moderate quality due to potential risk of bias in the contributing trial, and stillbirth (fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery vessels) received a low quality rating due to imprecision and heterogeneity. Evidence for admission to neonatal intensive care unit was assessed as of moderate quality (downgraded once for potential risk of bias), and evidence for the outcomes of caesarean section and preterm birth less than 37 weeks was graded as of high quality. Please see the Table 1 below.

Potential biases in the review process

Evidence in this review was derived from studies identified in a detailed search process. Trials comparing interventions of Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler that have not been published may not have been identified. We attempted to minimise bias in the review process by having two review authors independently extract data.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A brief literature search identified very few recent systematic reviews on the use of Doppler ultrasound in low risk populations. Studying unselected or low‐risk populations, Goffinet 1997 found no group differences between women who received Doppler or no Doppler. In a trial of the use of Doppler for multiple pregnancy, Giles 2003 found similar rates of antenatal, peripartum and neonatal outcomes, including unexplained fetal death, in women who received Doppler or no Doppler. Stampalija 2010 also identified no benefit to women or infants from Doppler ultrasound in the second trimester for women at low risk of hypertensive disorders. A retrospective cohort study (Morales‐Rosello 2014) suggested that Doppler may be useful for detecting appropriate for gestational age fetuses who do not reach growth potential at term. In an overview of recent research in low‐ and high‐risk women, O'Connor 2013 concluded that the use of Doppler measures in "appropriately grown and large for gestational age fetuses has yet to be fully validated." The wider literature corroborates the results of our review on the use of Doppler in low‐risk or unselected populations.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

When we take into account the perinatal mortality including anomalies, there is no conclusive evidence that Doppler ultrasound makes a difference. There is some evidence that umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry may reduce the risk of potentially preventable perinatal deaths. However, these findings are based on few trials and subgroup analyses. For these reasons, we conclude that existing data do not provide robust enough evidence that the use of routine umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound, or combination of umbilical and uterine artery Doppler ultrasound in low‐risk or unselected populations benefits either mother or baby. Until further research can support new practices, Doppler ultrasound examination should be reserved for use in high‐risk pregnancies (Alfirevic 2013).

Implications for research.

If there is to be future research into fetal and umbilical Doppler ultrasound examination in low‐risk or unselected populations, a large trial with adequate power to test hypotheses related to perinatal outcome is required. Trials should focus on potentially preventable deaths and inclusion criteria should reflect that. It would also be important to include assessment of neurodevelopment and assessment of maternal outcomes and psychological effects on the mother.

Several of our prespecified secondary outcomes were not measured in any trial included in this review.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 June 2015 | Amended | Added Acknowledgements statement. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 1999 Review first published: Issue 2, 2000

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 27 March 2015 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Review updated. |

| 27 March 2015 | New search has been performed | Search updated on 28 February 2015 and two reports identified (Forward 2014; Stoch 2012). Both studies were added to references as additional follow‐up data for Newnham 1993. Background and Methods have been updated and a 'Summary of findings' table incorporated ‐ see Differences between protocol and review for details. |

| 28 January 2010 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New review team substantially updated the review. |

| 20 May 2009 | New search has been performed | Search updated. Six new trials excluded (Ellwood 1997; Goffinet 2001; Scholler 1993; Snaith 2006; Subtil 2000; Subtil 2003). |

| 6 November 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 5 February 2007 | Amended | Review withdrawn from publication. |

| 14 January 2000 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Professor AM Weindling (Professor of Perinatal Medicine, University of Liverpool) for advice on neonatal outcomes to the authors of the original version of this review (Bricker 2007). Also to Dr JA Davies, and to Professor J Newnham and Dr Sharon Evans for also providing further information on their trials (Davies 1992; Newnham 1993) to the authors of the original version of this review (Bricker 2007).

Our thanks to Leanne Bricker, James P Neilson and Gill Gyte for their work on the previous version of this review.

Richard Riley who provided help with the statistical analysis, in particular with the random‐effects analyses and prediction intervals.

Nancy Medley's work was financially supported by the UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), Department of Reproductive Health and Research (RHR), World Health Organization. The named authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. All routine Doppler ultrasound versus no Doppler ultrasound.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Perinatal death (stillbirth and neonatal death including anomalies) | 4 | 11183 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.35, 1.83] |

| 1.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 2 | 5907 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.21, 1.07] |

| 1.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 2 | 5276 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.29, 4.56] |

| 2 Serious neonatal morbidity | 1 | 2016 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.06, 15.75] |

| 2.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 2016 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.06, 15.75] |

| 2.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Any death after randomisation (non‐prespecified) | 4 | 11183 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.44, 1.49] |

| 3.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 2 | 5907 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.21, 1.07] |

| 3.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 2 | 5276 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.47, 2.38] |

| 4 Stillbirth | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 2 | 6877 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.12, 0.95] |

| 4.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 2 | 5276 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.41 [0.44, 4.46] |

| 5 Neonatal death (up to 28 days) | 4 | 11183 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.17, 4.41] |

| 5.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 2 | 5907 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.06, 6.82] |

| 5.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 2 | 5276 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.06, 22.44] |

| 6 Potentially preventable perinatal death | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 2 | 6878 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.15, 0.87] |

| 6.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 2 | 5276 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.74 [0.37, 8.06] |

| 7 Fetal acidosis | 1 | 1518 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.87, 1.25] |

| 7.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 1518 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.87, 1.25] |

| 7.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 4 | 11375 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.56, 1.39] |

| 8.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 3 | 8900 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.47, 1.29] |

| 8.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 1 | 2475 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.48 [0.53, 4.14] |

| 9 Caesarean section (elective and emergency) | 2 | 6373 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.85, 1.13] |

| 9.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.84, 1.16] |

| 9.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 1 | 2475 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.74, 1.29] |

| 10 Elective caesarean section | 4 | 11375 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.87, 1.18] |

| 10.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 3 | 8900 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.87, 1.23] |

| 10.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 1 | 2475 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.70, 1.28] |

| 11 Emergency caesarean section | 2 | 6373 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.74, 1.18] |

| 11.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.71, 1.17] |

| 11.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 1 | 2475 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.52, 2.59] |

| 12 Spontaneous vaginal birth | 2 | 6373 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.96, 1.02] |

| 12.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.94, 1.02] |

| 12.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 1 | 2475 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.95, 1.06] |

| 13 Operative vaginal birth | 2 | 6884 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.96, 1.12] |

| 13.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 2 | 6884 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.96, 1.12] |

| 13.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14 Induction of labour | 4 | 11190 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.97, 1.12] |

| 14.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 2 | 5914 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.97, 1.22] |

| 14.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 2 | 5276 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.93, 1.10] |

| 15 Neonatal resuscitation | 2 | 6373 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.84, 1.24] |

| 15.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.80, 1.27] |

| 15.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 1 | 2475 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.74, 1.52] |

| 16 Infant intubation/ventilation | 1 | 2986 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.54, 1.81] |

| 16.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 2986 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.54, 1.81] |

| 16.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 17 Preterm birth (before 37 weeks) | 4 | 12162 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.86, 1.21] |

| 17.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 2 | 6884 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.75, 1.39] |

| 17.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 2 | 5278 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.77, 1.40] |

| 18 Neonatal admission to SCBU/NICU | 3 | 7477 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.84, 1.17] |

| 18.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 2 | 5002 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.82, 1.18] |

| 18.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 1 | 2475 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.67, 1.53] |

| 19 Birthweight | 2 | 5914 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐17.55 [‐42.23, 7.13] |

| 19.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 2 | 5914 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐17.55 [‐42.23, 7.13] |

| 19.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 20 Gestational age at birth | 2 | 5914 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.08 [‐0.16, ‐0.00] |

| 20.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 2 | 5914 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.08 [‐0.16, ‐0.00] |

| 20.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 2. Single Doppler ultrasound assessment versus no Doppler ultrasound.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Perinatal death (stillbirth and neonatal death including anomalies) | 1 | 3891 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.13, 0.99] |

| 1.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3891 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.13, 0.99] |

| 1.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Stillbirth | 1 | 3891 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.08, 2.05] |

| 2.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3891 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.08, 2.05] |

| 2.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Neonatal death (up to 28 days after birth) | 1 | 3891 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.03, 2.23] |

| 3.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3891 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.03, 2.23] |

| 3.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Any death after randomisation (non‐prespecified) | 1 | 3891 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.13, 0.99] |

| 4.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3891 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.13, 0.99] |

| 4.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Potentially preventable perinatal death | 1 | 3892 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.11, 1.03] |

| 5.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3892 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.11, 1.03] |

| 5.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.38, 2.66] |

| 6.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.38, 2.66] |

| 6.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7 Caesarean section (elective and emergency) | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.84, 1.16] |

| 7.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.84, 1.16] |

| 7.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Elective caesarean section | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.84, 1.34] |

| 8.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.84, 1.34] |

| 8.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9 Emergency caesarean section | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.71, 1.17] |

| 9.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.71, 1.17] |

| 9.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10 Spontaneous vaginal birth | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.94, 1.02] |

| 10.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.94, 1.02] |

| 10.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Operative vaginal birth | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.95, 1.26] |

| 11.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.95, 1.26] |

| 11.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12 Induction of labour | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.99, 1.33] |

| 12.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.99, 1.33] |

| 12.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 13 Neonatal resuscitation | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.80, 1.27] |

| 13.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.80, 1.27] |

| 13.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14 Preterm birth (before 37 weeks) | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.20 [0.86, 1.69] |

| 14.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.20 [0.86, 1.69] |

| 14.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 15 Birthweight | 1 | 3898 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐14.0 [‐42.94, 14.94] |

| 15.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3898 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐14.0 [‐42.94, 14.94] |

| 15.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 16 Gestational age at birth | 1 | 3898 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.10 [‐0.19, ‐0.01] |

| 16.1 Fetal/umbilical vessels only | 1 | 3898 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.10 [‐0.19, ‐0.01] |

| 16.2 Fetal/umbilical vessels + uterine artery | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Single Doppler ultrasound assessment versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 3 Neonatal death (up to 28 days after birth).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Single Doppler ultrasound assessment versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 5 Potentially preventable perinatal death.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Single Doppler ultrasound assessment versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 6 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Single Doppler ultrasound assessment versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 7 Caesarean section (elective and emergency).

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Single Doppler ultrasound assessment versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 8 Elective caesarean section.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Single Doppler ultrasound assessment versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 9 Emergency caesarean section.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Single Doppler ultrasound assessment versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 10 Spontaneous vaginal birth.

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Single Doppler ultrasound assessment versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 11 Operative vaginal birth.

2.12. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Single Doppler ultrasound assessment versus no Doppler ultrasound, Outcome 12 Induction of labour.

2.13. Analysis.