Abstract

Background

The use of ultrasound guidance for regional anaesthesia has become popular over the past two decades. However, it is not recognized by all experts as an essential tool. The cost of an ultrasound machine is substantially higher than the cost of other tools such as a nerve stimulator.

Objectives

To determine whether ultrasound guidance offers any clinical advantage when neuraxial and peripheral nerve blocks are performed in children in terms of increasing the success rate or decreasing the rate of complications.

Search methods

We searched the following databases to March 2015: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE (OvidSP), EMBASE (OvidSP) and Scopus (from inception to 27 January 2015).

Selection criteria

We included all parallel randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated the effects of ultrasound guidance used when a regional blockade technique was performed in children, and that included any of our selected outcomes.

Data collection and analysis

We assessed selected studies for risk of bias by using the assessment tool of The Cochrane Collaboration. Two review authors independently extracted data. We graded the level of evidence for each outcome according to the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) Working Group scale.

Main results

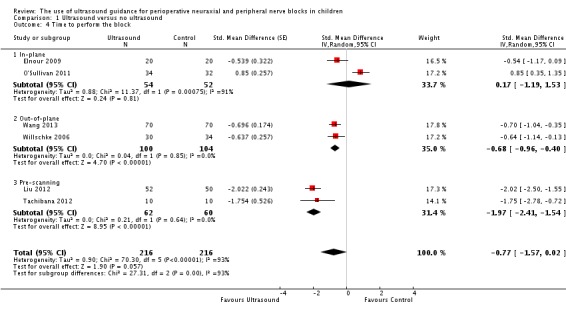

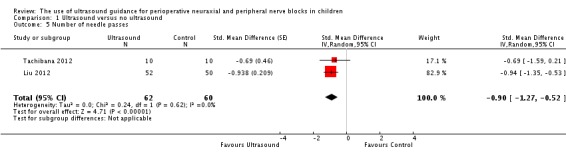

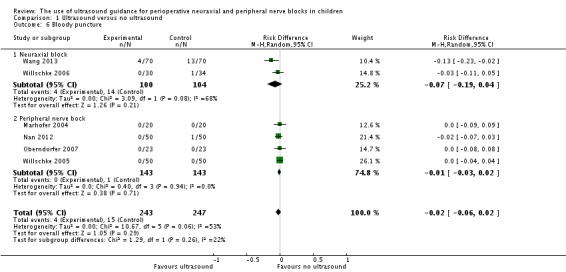

We included 20 studies (1241 participants) for which the source of funding was a government organization (two studies), a charitable organization (one study), an institutional department (four studies) or an unspecified source (11 studies); two studies declared that they received help from the industry (equipment loan). In 14 studies (939 participants), ultrasound guidance increased the success rate by decreasing the occurrence of a failed block: risk difference (RD) ‐0.11 (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.17 to ‐0.05); I2 = 64%; number needed for additional beneficial outcome for a peripheral nerve block (NNTB) 6 (95% CI 5 to 8). Blocks were performed under general anaesthesia (usual clinical practice in this population); therefore, haemodynamic changes to the surgical stimulus (rather than classic sensory/motor blockade evaluation) were used to define success. For peripheral nerve blocks, the younger the child, the greater was the benefit. In eight studies (414 participants), pain scores at one hour in the post‐anaesthesia care unit were reduced when ultrasound guidance was used; however, the clinical relevance of the difference was unclear (equivalent to ‐0.2 on a scale from 0 to 10). In eight studies (358 participants), block duration was longer when ultrasound guidance was used: standardized mean difference (SMD) 1.21 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.65; I2 = 73%; equivalent to 62 minutes). Here again, younger children benefited most from ultrasound guidance. Time to perform the procedure was reduced when ultrasound guidance was used for pre‐scanning before a neuraxial block (SMD ‐1.97, 95% CI ‐2.41 to ‐1.54; I2 = 0%; equivalent to 2.4 minutes; two studies with 122 participants) or as an out‐of‐plane technique (SMD ‐0.68, 95% CI ‐0.96 to ‐0.40; I2 = 0%; equivalent to 94 seconds; two studies with 204 participants). In two studies (122 participants), ultrasound guidance reduced the number of needle passes required to perform the block (SMD ‐0.90, 95% CI ‐1.27 to ‐0.52; I2 = 0%; equivalent to 0.6 needle pass per participant). For two studies (204 participants), we could not demonstrate a difference in the incidence of bloody puncture when ultrasound guidance was used for neuraxial blockade, but we found that the number of participants was well below the optimal information size (RD ‐0.07, 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.04). No major complications were reported for any of the 1241 participants. We rated the quality of evidence as high for success, pain scores at one hour, block duration, time to perform the block and number of needle passes. We rated the quality of evidence as low for bloody punctures.

Authors' conclusions

Ultrasound guidance seems advantageous, particularly in young children, for whom it improves the success rate and increases the block duration. Additional data are required before conclusions can be drawn on the effect of ultrasound guidance in reducing the rate of bloody puncture.

Keywords: Child; Humans; Ultrasonography, Interventional; Nerve Block; Nerve Block/methods; Perioperative Care; Perioperative Care/methods; Peripheral Nervous System; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Ultrasound guidance for injecting local anaesthetics in children to block pain transmission

Background

A local anaesthetic can be injected into the spine or around the nerves to block pain transmission to avoid putting the patient to sleep for surgery or to treat postoperative pain. This is called ‘regional blockade’. Finding an effective alternative to general anaesthetics or traditional painkillers is particularly important for children because they might be more likely to suffer adverse effects from general anaesthesia or opioid painkillers, and because pain in early life might do long‐term harm. Regional blockade can be performed by inserting a needle into the skin at a place that is determined by palpation of bones or a pulsatile vessel. An electric needle producing a muscle contraction can also be used to find a suitable location. Over the past three decades, clinicians have started to use ultrasound to locate the nerves, but these machines are expensive and require additional clinician expertise. A Cochrane review has already found that ultrasound guidance does not increase the rate of success of regional blockade but does reduce harmful effects in adults. We wanted to know whether effects in children are the same.

Search date

Evidence is current to March 2015.

Study characteristics

We included 20 randomized controlled trials in which ultrasound was compared with another method of nerve localization for regional blockade in children.

Study funding sources

Sources of funding included a government organization (two studies), a charitable organization (one study) and an institutional department (four studies). Two studies declared that they received help from the industry (equipment loan). The source of funding was unclear for 11 studies.

Key results

Ultrasound guidance decreased the occurrence of a failed block (actual rate without ultrasound 25%). If six blocks were performed, one fewer participant would have a failed block if ultrasound guidance was used. The identified studies used children from different age groups. If we compare results by age, we find that the younger the child, the greater was the reduction in failed blocks. Pain scores at one hour after surgery were reduced when ultrasound guidance was used, but the reduction in pain was small. When ultrasound guidance was used, the time that lapsed before the child needed additional painkillers after surgery was increased by approximately 62 minutes from the usual mean time ranging from 11 minutes to seven hours. Here again, the younger the child, the longer was the difference in delay to the appearance of pain. Time to perform the block was reduced when ultrasound guidance was used for pre‐scanning before a block in the spine was performed (equivalent to 2.4 minutes less from a mean time of 3.2 minutes in the control group). Ultrasound guidance reduced the number of needle passes required to perform the block: mean 0.6 needle pass per participant (from a mean of 1.6 in the control group). Data are needed to show whether ultrasound guidance also reduces the number of unwanted needle entrances into a blood vessel (actual rate without ultrasound 14%). No major complications were reported in any of the 1241 participants.

Quality of evidence

The quality of the evidence was rated as high for decreased occurrence of a failed block, improved pain scores at one hour, increased block duration, reduced time needed to perform regional blockade when ultrasound guidance was used as pre‐scanning before a block in the spine and a decreased number of needle passes. The level of evidence was rated as low for the number of unwanted needles entered into a blood vessel.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Ultrasound guidance compared with no ultrasound guidance for children

| Ultrasound guidance compared with no ultrasound guidance for children | ||||||

| Patient or population: children Settings: Data were collected in Austria (1 study), Belgium (1 study), Canada (1 study), China (3 studies), Egypt (1 study), India (2 studies), Japan (1 study), Ireland (1 study), South Africa (4 studies), Turkey (2 studies) and United States of America (3 studies) Intervention: ultrasound guidance Comparison: no ultrasound guidance | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No ultrasound guidance | Ultrasound guidance | |||||

| Success (analysed as decreased failure rate) | Study population | Risk difference 0 (0 to ‐0.07) | 507 (8 studiesa) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ highb,c,d,e,f,g,h,i | Only studies on peripheral nerve blocks were retained for this outcome | |

| 254 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to ‐18) | |||||

| Low | ||||||

| 25 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to ‐2) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 350 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to ‐25) | |||||

| Pain scores at 1 hour after surgery | Mean pain scores at 1 hour after surgery in the intervention groups was 0.29 standard deviations lower (0.54 to 0.04 lower) | 308 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ highb,d,f,h,j,k,l,m | One study (Lorenzo 2014) was excluded for this outcome to reduce the amount of heterogeneity (see Effects of interventions). The reduction is equivalent to 0.2 on the Children’s and Infant’s Postoperative Pain Scale (CHIPPS scale: 0 = no pain, 10 = maximal pain) |

||

| Block duration Time to request of first analgesic Follow‐up: 0 to 1 day | Mean block duration in intervention groups was 1.21 standard deviations higher (0.76 to 1.65 higher) | 358 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ highb,c,d,f,h,k,n,o | Mean prolongation of the block was equivalent to 62 minutes | ||

| Time to perform the procedure Ultrasound guidance used as pre‐scanning before neuraxial block | Mean time to perform the procedure in intervention groups was 1.97 standard deviations lower (2.41 to 1.54 lower) | 122 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ highd,h,k,m,p,q,r,s | This is equivalent to 2.4 minutes when ultrasound guidance was used as pre‐scanning before neuraxial block | ||

| Number of needle passes | Mean number of needle passes in intervention groups was 0.90 standard deviations lower (1.27 to 0.52 lower) | 122 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ highd,h,k,m,p,q,r,t | Mean difference is equivalent to 0.6 needle pass per participant | ||

| Bloody puncture | Study population | Risk difference ‐0.07 (‐0.19 to 0.04) | 204 (2 studiesu) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb,d,e,h,l,m,r,v | For this outcome, we retained only studies in which ultrasound guidance was used for neuraxial block | |

| 135 per 1000 | ‐9 per 1000 (‐26 to 5) | |||||

| Low | ||||||

| 20 per 1000 | ‐1 per 1000 (‐4 to 1) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 200 per 1000 | ‐14 per 1000 (‐38 to 8) | |||||

| *The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: Confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

aFor this outcome, we retained only studies performed on peripheral nerve blocks bAllocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessors were judged adequate for 50% or more of the studies cAn explanation was found for the heterogeneity dDirect comparisons performed on the population of interest; the outcome is not a surrogate marker eThe number of participants included is lower than the optimal information size for a large trial fNo evidence of publication bias, or correcting for the possibility of one, would not modify the conclusion gRisk ratio smaller than 0.5 hNo confounding factor justifying upgrading the evidence identified iFor peripheral nerve blocks, an inverse correlation between effect size and age was noted jFor this outcome, we excluded 1 study. I2 = 31% after exclusion of 1 study kOptimal information size achieved lNo evidence of a large effect mNo evidence of a dose‐response effect nSMD 1.21 oThe effect was inversely proportional to age; younger participants benefitted most from ultrasound guidance pWe retained only 2 studies for this outcome: Allocation concealment was unclear and blinding of the outcome assessor was not feasible for this outcome qI2statistic smaller than 25% rPublication bias assessment not available because of the low number of studies retained sSMD ‐1.97 tSMD ‐0.90 uFor this outcome, we retained only studies on neuraxial blocks vI2 statistic greater than 50%

Background

In 2005, in the United States alone, approximately 647,000 children were discharged from a short stay hospital after they had undergone a surgical procedure (DeFrances 2007). Anaesthesiologists are involved in these procedures at various steps of the process, amongst which anaesthesia for the procedure itself and treatment of postoperative pain are of the utmost importance. Although a vast majority of surgeries in children are performed with the child under general anaesthesia, concerns have been raised about the safety of inhalational agents for the developing brain of a child (Chiao 2014). As such, regional anaesthesia has been identified as a possible favourable replacement for general anaesthesia for specific surgeries (Nemergut 2014). Furthermore, in 2000, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) suggested that pain should be considered as the fifth vital sign, and that under treatment of pain should constitute abrogation of a fundamental human right (White 2007). After this statement was issued, an increase in the use of opioids for treatment of patients with acute postoperative pain was observed, as was an increase in opioid side effects (White 2007). Postoperative pain relief is of particular importance in children. Pain experienced early in life may induce organic brain changes that can make children susceptible to an exaggerated brain response when pain is experienced later in life (Hohmeister 2010). These brain changes are frequently referred to as neuroplasticity. Young children often are unable to understand what is happening to them, and this may increase their distress, leading to an increase in their inability to convey what exactly is making them uncomfortable. In response to this situation, care providers may under treat or over treat children experiencing postoperative pain. In one study performed in children, adverse events requiring an intervention (therefore judged as clinically relevant) occurred in 22% and 24% of patients with patient‐controlled analgesia (PCA) administered by trained relatives or nurses and by the patients themselves, respectively (Voepel‐Lewis 2008). Opioid‐based regimens may therefore provide suboptimal treatment for postoperative pain in children.

Description of the condition

Regional blockade interrupts pain transmission to the brain and may be used during the surgery itself as a replacement for general anaesthesia (regional anaesthesia), or for treatment of postoperative pain (regional analgesia). In adults, regional analgesic techniques decrease postoperative opioid consumption (Guay 2006), making them a potentially interesting alternative or adjunct to opioid‐based regimens for treatment of children with postoperative pain. Regional blockade techniques can be classified as central neuraxial blocks (spinal, epidural, combined spinal and epidural or caudal) or as peripheral nerve blocks. The use of regional blockade in children is considered reasonably safe today (Long 2014; Polaner 2012). For a total of 14,917 regional blocks performed on 13,725 study participants from 1 April 2007 through 31 March 2010, no deaths or complications with sequelae lasting longer than three months were reported (95% confidence interval (CI) 0 to 2 per 10,000 blocks) (Polaner 2012). For neuraxial blocks, 183 adverse events were reported, at an incidence of 3% (95% CI 26 to 35 per 1000) (Polaner 2012). The most common adverse event (104, or 2% of the total and 57% of all events) was inability to place the block, or block failure (Polaner 2012). Ninety‐three per cent of neuraxial blocks were placed without imaging guidance. Inability to place the block or a failed block was also the most common adverse event for upper extremity blocks and was reported in six of 1000 lower limb blocks (Polaner 2012).

Description of the intervention

Ultrasound refers to an oscillating sound pressure wave at a frequency above the upper limit audible to the human ear (approximately 20 kHz). In nature, bats use ultrasounds as a guide for night flights. Ultrasounds emitted by the animal are reflected when they hit an obstacle. The same principle has been applied to develop devices in which ultrasound is used to create two‐dimensional (2‐D) or even three‐dimensional (3‐D) pictures (Feinglass 2007). Ultrasound has been used for regional blockade for almost three decades. The pioneers to whom use of ultrasound for regional blockade could be attributed include P. La Grange (La Grange 1978), R.L. Ting (Ting 1989), T.‐J. Wu (Wu 1993) and S. Kapral (Kapral 1994). The probe emitting and receiving ultrasounds is placed over the area of the body in which the local anaesthetic will be injected. After appropriate visualization of the target, the needle may be advanced in‐plane (parallel to the beam), allowing visualization of the entire needle during its trajectory, or out‐of‐plane (perpendicular to the beam). The local anaesthetic is then injected under visualization. For neuraxial blocks, ultrasound guidance can be used in real time to observe advancement of the needle within the epidural space or within the intrathecal canal (Niazi 2014), but most often it is used as a pre‐puncture guide to identify the exact vertebral level needed, to find an appropriate intervertebral space sufficient to allow passage of the needle, to determine the depth to which the needle should be advanced for placement of its tip at the chosen location and to visualize the spread of the local anaesthetic. For peripheral nerve blocks, ultrasound guidance allows visualization of target nerves, advancement of the needle (in‐plane technique) and spread of the local anaesthetic.

How the intervention might work

In children, regional anaesthetic techniques are usually performed with the child under deep sedation or under general anaesthesia. Fortunately, this does not seem to increase the risk of complications associated with regional anaesthesia (Taenzer 2014). However, as the child cannot express any paraesthesia‐related discomfort (with potential needle placement inside a neural structure), visualization may be even more important in this age group. Regional blockade may be performed with the use of landmarks, a nerve stimulator or ultrasound guidance. Ultrasound guidance allows adequate visualization of nerves and other structures relevant to the performance of both neuraxial and peripheral nerve blocks, particularly in children, in whom relevant structures are relatively superficial. Failed block is the most common problem in paediatric regional anaesthesia when neuraxial blocks are performed without the use of an imaging technique (Polaner 2012), and inadvertent vascular puncture occurs in 2% (95% CI 12 to 21 per 1000) of children undergoing neuraxial block. Ultrasound may decrease inadvertent vascular puncture (Walker 2009). Thus ultrasound guidance for regional anaesthesia in children may improve the success rate while decreasing the rate of complications.

Why it is important to do this review

The use of ultrasound guidance for regional anaesthesia has become popular over the past two decades. However, ultrasound is not recognized by all experts as an essential tool. Indeed, many authorities believe that no actual evidence suggests that ultrasound guidance would decrease the occurrence of important complications such as neurological damage (Neal 2008). A Cochrane review determined that ultrasound guidance appeared to reduce the incidence of vascular puncture or haematoma formation in adults but yielded a similar success rate (Walker 2009). The cost of an ultrasound machine varies, but most machines used in the clinical practice of regional anaesthesia cost approximately USD 40,000 or more (Liu 2010). Thus, equipment required to use ultrasound guidance is substantially more expensive than other tools, such as those used for nerve stimulation, which can be acquired for approximately USD 1000 or less (Liu 2010). In 2010, a comprehensive review of the paediatric literature concluded that additional outcome‐based, prospective, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were needed to prove the benefits of ultrasound guidance over conventional methods in children (Tsui 2010).

Objectives

To determine whether ultrasound guidance offers any clinical advantage when neuraxial and peripheral nerve blocks are performed in children in terms of increasing the success rate or decreasing the rate of complications.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all parallel RCTs that evaluated the effect of ultrasound guidance when a regional blockade technique was performed in children and that included any of our selected outcomes.

We excluded observational studies, quasi‐randomized trials, cross‐over trials and cluster‐randomized trials.

We excluded no studies on the basis of language of publication or publication status.

Types of participants

We included studies performed in children (≤ 18 years of age) undergoing any type of surgical procedure (open or laparoscopic) for which a neuraxial (spinal, epidural, caudal or combined spinal and epidural) or peripheral nerve block (any peripheral nerve block including fascial (fascia iliaca, transversus abdominis plane, rectus sheath blocks) or perivascular blocks), for surgical anaesthesia (alone or in combination with general anaesthesia) or for postoperative analgesia, was performed with ultrasound guidance.

We excluded studies in which regional blockade was used to treat chronic pain.

Types of interventions

We included studies in which ultrasound guidance was used to perform the technique in real time (in‐plane or out‐of‐plane), as pre‐scanning before the procedure or to evaluate the spread of the local anaesthetic so the position of the needle could be adjusted or the block complemented. For control groups, any other technique used to perform the block including landmarks, loss of resistance (air or fluid), click, paraesthesia, nerve stimulator, transarterial or infiltration was accepted.

We discarded no studies on the basis of the specific technique used as the comparator.

Types of outcome measures

We evaluated differences between treatment and control groups based on the following outcomes.

Primary outcomes

Success rate (study author's definition).

Pain scores in the post‐anaesthesia care unit (PACU).

Block duration (study author's definition).

Secondary outcomes

Time to perform the procedure.

Number of needle passes.

Minor complications (bloody puncture).

Major complications: local anaesthetic toxicity (signs of systemic toxicity including seizure or cardiac arrest), infection, neurological injury (transient or lasting longer than one month).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Appendix 1; 2015, Issue 3), MEDLINE (OvidSP) (from 1946 to March 2015; Appendix 2), EMBASE (OvidSP) (from 1982 to March 2015; Appendix 3) and Scopus (from inception to 27 January 2015) (Appendix 4).

Searching other resources

We looked at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (January 2015), http://isrctn.org (January 2015), http://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/index.htm (January 2015),

http://www.anzctr.org.au (January 2015), http://www.trialregister.nl/ (January 2015) and https://udract.ema.europa.eu/ (January 2015) to identify trials in progress.

We screened the reference lists of all studies retained (during data extraction) and of the recent meta‐analysis or reviews related to the topic (March 2015). We screened conference proceedings of anaesthesiology societies for 2012, 2013 and 2014, published in three major anaesthesiology journals: British Journal of Anaesthesiology (January 2015),European Journal of Anaesthesiology (January 2015) and Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (January 2015). We also looked for abstracts on the Website of the American Society of Anesthesiologists for the same years (2012 through 2014) (January 2015).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We (JG and SK) screened the list of all titles and abstracts identified by the search above. We retrieved and independently read potential articles for inclusion to determine their eligibility. We resolved discrepancies by discussion without the need for help from the third review author (SS). We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Moher 2009), We listed all reasons for exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

We selected studies, extracted data (assessment of risk of bias in included studies; types of outcome measures; assessment of heterogeneity) and entered the data onto our data extraction sheet. We entered first the site where the study was performed and the date of data collection (to facilitate exclusion of duplicate publications), then whether the study was included in the review or the reason for rejection. After we reached agreement, one review author (JG) entered the data and the moderators for heterogeneity exploration into Comprehensive meta‐analysis (https://www.meta‐analysis.com/). Also, after agreement was reached, the same review author (JG) entered the risk of bias evaluation into RevMan. We resolved disagreements by discussion and contacted study authors to request additional information when required. We then transferred data for analysis to RevMan in the format required to include the maximal number of studies (events and total number of participants for each group; mean, standard deviation and number of participants included in each group; or generic inverse variance if necessary). When possible, we entered the data into an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the quality of the included studies by using the tool of The Cochrane Collaboration found in RevMan 5.3 (Higgins 2011). We resolved disagreements by discussion. We considered a trial as having low risk of bias if we assessed all of the following criteria as adequate, and as having high risk of bias if one or more of the criteria were assessed as inadequate. We assessed the risk of bias based on the basis of information presented in the reports, with no assumptions made.

Generation of the allocation sequence of interventions: We considered randomization adequate if it was generated by a computer or by a random number table algorithm. We judged other processes, such as tossing of a coin, adequate if the whole sequence was generated before the start of the trial. We considered the trial as quasi‐randomized if a non‐random system, such as dates, names or identification numbers, was used.

Concealment of allocation: We considered concealment adequate if the process that was used prevented patient recruiters, investigators and participants from knowing the intervention allocation of the next participant to be enrolled in the study. We considered concealment inadequate if the allocation method allowed patient recruiters, investigators or participants to know the treatment allocation of the next participant to be enrolled in the study.

Blinding of participants and personnel: We considered blinding adequate if both the participant and personnel taking care of the participant were blinded to the intervention. We considered blinding inadequate if participants or personnel were not blinded to the intervention.

Blinding of outcome assessment: We considered blinding adequate if the outcome assessor was blinded to the intervention. We considered blinding inadequate if the outcome assessor was not blinded to the intervention.

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias): We considered the trial adequate if all dropouts or withdrawals were accounted for, the number of dropouts was small (< 20%) and similar for both interventions and reasons for dropping out of participants sounded reasonable. We considered the trial inadequate if reasons for dropping out of the patient were not stated or did not sound reasonable, the number was high (≥ 20%) or the number differed greatly between groups.

Selective reporting (reporting bias): We considered a trial as having low risk of bias if all measurements stated in the Methods section were included in the Results, and as having high risk if only a portion of the results mentioned in the Methods section were given in the Results section. We considered per‐protocol results (not intention‐to‐treat (ITT)) as selective reporting.

Any other risk of bias: We considered any other reason that may have influenced study results. We considered an apparent conflict of interest as representing a risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We reported results as risk differences (RD) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for dichotomous data (success rate, minor and major complications) and as mean differences (MDs) and 95% CIs for continuous data (pain scores, block duration, time to perform the procedure) as much as was feasible. If some of the continuous data were given on different scales (pain scores), or if results were provided with P values (number of attempts or needle passes), we presented the results as standardized mean differences (SMDs) and 95% CIs. For SMDs, we considered 0.2 a small effect, 0.5 a medium effect and 0.8 a large effect (Pace 2011). When an effect was noted, a number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) or a number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) was calculated from the odds ratio. We gave results for dichotomous data as risk ratios (RRs or RDs) as the odds ratio (OR) is not easily understood by clinicians (Deeks 2002; McColl 1998). We used the OR for calculation of the NNTB and NNTH (http://www.nntonline.net/visualrx/), as this value is less likely to be affected by the side (benefit or harm) on which data are entered (Cates 2002; Deeks 2002). When no effect was noted, we calculated the optimal information size to make sure that enough participants were included in the retained studies to justify a conclusion on the absence of effect (Pogue 1998) (http://www.stat.ubc.ca/˜rollin/stats/ssize/b2.html). We considered a difference of 15% (increase or decrease) as the minimal clinically relevant difference.

Unit of analysis issues

We included only parallel‐group trials. If a study contained more than two groups, we fused two groups (by using the appropriate formula for adding standard deviations when required) if we thought that they were equivalent according to the criteria of our protocol (taking our factors for heterogeneity exploration into account), or we separated them and split the control group in half if we thought that they were different.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors to ask for apparent missing data. We did not consider medians as equivalent to means. Instead, we used the P value and the number of participants included in each group to calculate the effect size. We did not use imputed results. We entered data as ITT data as much as was feasible. If we could not do this, we assigned the study as having high risk of bias for selective reporting and entered the data on a per‐protocol basis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered clinical heterogeneity before pooling results and examined statistical heterogeneity before carrying out any meta‐analysis. We quantified statistical heterogeneity by using the I2 statistic and entered data in the way (benefit or harm) that yielded the least heterogeneity. We quantified the amount of heterogeneity as low (< 25%), moderate (50%) or high (75%), depending on the value obtained for the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003).

Assessment of reporting biases

We examined publication bias by using a funnel plot followed by Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill technique for each outcome. Publication bias is the risk of bias introduced by the possibility that medical journals publish studies favouring one treatment more often than studies favouring another. When no publication bias and no small‐study effect are noted, if a graph is constructed with standard error or precision (1/standard error) on the y‐axis and the logarithm of the OR on the x‐axis, studies should be equally distributed on both sides of a vertical line passing through the effect size found (log odds ratio). The entire graph should have the shape of a reversed funnel. Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill analysis corrects the asymmetry by removing extremely small studies from the positive side (re‐computing the effect size at each iteration until the funnel plot is symmetrical around the new effect size). The algorithm then adds the original studies back into the analysis and imputes a mirror image for each. The latter step does not modify the ’new effect size’ but corrects the variance, which was falsely reduced by the first step. Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill analysis yields an estimate of what would be the effect size (OR, RR, etc) if no publication bias was present.

Data synthesis

We analysed the data by using RevMan 5.3 and Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis Version 2.2.044 (www.Meta‐Analysis.com) with fixed‐effect models for comparisons with a low level of heterogeneity as assessed by the I2 statistic (I2 < 25%) and random‐effects models for comparisons containing a moderate or high amount of heterogeneity (I2 ≥ 25%) (Higgins 2003). Fixed‐effect and random‐effects models provide the same results in the absence of statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). When statistical heterogeneity is noted, random‐effects models usually widen the CI, thus decreasing the chance of finding an effect when no effect is present. However, they may increase the weight of smaller studies. We presented the characteristics of included and excluded studies in the Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables. We presented the risk of bias assessment in a risk of bias graph. We presented results for each comparison as forests plots when appropriate. For comparisons with fewer than two available studies, and for those that included a moderate or high level of heterogeneity after heterogeneity exploration, we provided the results in narrative format.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We explored any amount of heterogeneity, but we focused more specifically on comparisons with more than a small amount of heterogeneity (I2 ≥ 25%) (Higgins 2003), and we explored the heterogeneity by applying Egger’s regression intercept (to assess the possibility of a small‐study effect; Rucker 2011) and by performing visual inspection of the forest plots with studies placed in order according to a specific moderator, subgroupings (categorical moderators) or meta‐regressions (continuous moderators). We considered the following factors when exploring heterogeneity: type of block (neuraxial vs peripheral nerve block), type of comparator (nerve stimulator vs other), age and type of guidance (pre‐scanning vs real‐time (in‐plane or out‐of‐plane)) and combined methods (ultrasound plus nerve stimulator compared with other modalities vs ultrasound alone compared with other modalities).

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis (based mainly on the risk of bias assessment (allocation concealment and blinding of the assessor) or on an outlier) could also be performed for results with heterogeneity.

Summary of findings

We used the principles of the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system (Guyatt 2008) to assess the quality of the body of evidence associated with the following specific outcomes in our review.

Success rate.

Pain scores in PACU.

Block duration.

Time to perform the procedure.

Number of needle passes.

Minor complications.

We constructed a 'Summary of findings' (SoF) table using GRADE software (http://tech.cochrane.org/revman/gradepro).

The GRADE approach appraises the quality of a body of evidence on the basis of the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association reflects the item assessed. The quality of a body of evidence reflects within‐study risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of the evidence, heterogeneity of the data, precision of effect estimates, amplitude of the effect size and risk of publication bias.

For risk of bias, we judged the quality of evidence as adequate when most information was derived from studies at low risk of bias; we downgraded the quality by one level when most information was provided by studies at high or unclear risk of bias and we downgraded the quality by two levels when the proportion of information from studies at high risk of bias was sufficient to affect interpretation of results. For inconsistency, we downgraded the quality of evidence by one level when the I2 statistic was 50% or higher without satisfactory explanation, and by two levels when the I2 statistic was 75% or higher with no explanation. We did not downgrade the quality of evidence for indirectness, as all outcomes were based on direct comparisons, were performed on the population of interest and were not surrogate markers (Guyatt 2011a). For imprecision (Guyatt 2011b), we downgraded the quality of evidence by one level when the confidence interval around the effect size was large or overlapped an absence of effect and failed to exclude an important benefit or harm; when the number of participants was lower than the optimal information size (unless the sample size was ≥ 2000 participants or the number of events included was ≥ 400); and we downgraded the quality by two levels when the confidence interval was very wide and included both appreciable benefit and harm. For publication bias, we downgraded the quality of evidence by one level when correcting for the possibility of publication as assessed by Duval and Tweedie’s fill and trim analysis changed the conclusion. We upgraded the quality of evidence by one level when the effect size was large (risk ratio < 0.5 or > 2.0), and by two levels when the effect size was very large (RR < 0.2 or > 5.0) (Guyatt 2011c). For SMD, we used 0.8 as the cutoff point for a large effect (Pace 2011). We also upgraded the quality by one level when evidence of a dose‐related response was found. We upgraded the quality by one level when possible effect of confounding factors would reduce a demonstrated effect or would suggest a spurious effect when results show no effect. When the quality of the body of evidence is high, further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. When the quality is moderate, further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. When the quality is low, further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. When the quality is very low, any estimate of effect is very uncertain (Guyatt 2008).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

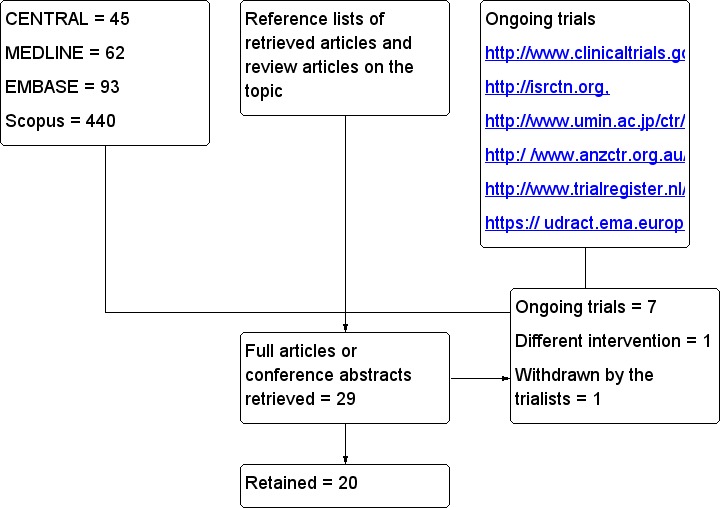

Upon completing the electronic search, we screened 640 titles/abstracts. Among these abstracts or from the reference list of potentially relevant studies, we found 29 trials that met our criteria for inclusion. Seven are ongoing trials (Characteristics of ongoing studies), one studied a different intervention and one was withdrawn by the study authors because of a problem with data collection (Characteristics of excluded studies). Therefore, we retained 20 studies (Figure 1) for this review.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram. Search results.

Included studies

The 20 studies included 1241 participants: in 624, the block was performed with ultrasound, and in 617, it was performed without ultrasound. The mean age of participants ranged from 0.9 to nine years.

The following surgeries were performed: circumcision (Faraoni 2010; O'Sullivan 2011), umbilical hernia repair (Dingeman 2013; Flack 2014; Gurnaney 2011), inguinal hernia repair (Kendigelen 2014; Nan 2012; Sahin 2013; Wang 2013; Weintraud 2009), inguinal hernia/orchidopexy (Willschke 2005), low urological/perineal surgery (Liu 2012), open pyeloplasty (Lorenzo 2014), major abdominal or thoracic surgery (Willschke 2006), the Nuss procedure for pectus excavatum (Tachibana 2012) and upper (Elnour 2009; Marhofer 2004; Ponde 2009) or lower limb surgery (Oberndorfer 2007; Ponde 2013).

The following blocks were performed: brachial plexus block (Elnour 2009; Marhofer 2004; Ponde 2009), sciatic and femoral nerve blocks (Oberndorfer 2007; Ponde 2013), ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric nerve blocks (Nan 2012; Weintraud 2009; Willschke 2005), penile nerve block (Faraoni 2010; O'Sullivan 2011), rectus sheath block (Dingeman 2013; Flack 2014; Gurnaney 2011), transversus abdominis plane blocks (Kendigelen 2014; Lorenzo 2014; Sahin 2013), thoracic epidural (Tachibana 2012), thoracic or lumbar epidural (Willschke 2006) and caudal blocks (Liu 2012; Wang 2013).

Ultrasound guidance was used in real time with an in‐plane (Elnour 2009; Faraoni 2010; Flack 2014; Gurnaney 2011; Lorenzo 2014; O'Sullivan 2011; Ponde 2009; Ponde 2013; Sahin 2013), out‐of‐plane (Marhofer 2004; Nan 2012; Oberndorfer 2007; Wang 2013; Weintraud 2009; Willschke 2005; Willschke 2006) or unspecified technique (Dingeman 2013; Kendigelen 2014), or as pre‐scanning (Liu 2012; Tachibana 2012). Ultrasound guidance was compared with infiltration (Dingeman 2013; Flack 2014; Gurnaney 2011; Kendigelen 2014; Lorenzo 2014), with landmarks (Faraoni 2010; Liu 2012; Nan 2012; O'Sullivan 2011; Sahin 2013; Tachibana 2012; Wang 2013; Weintraud 2009; Willschke 2005; Willschke 2006) or with a nerve stimulator (Elnour 2009; Marhofer 2004; Oberndorfer 2007; Ponde 2009; Ponde 2013).

The source of funding was a government organization (Flack 2014; Nan 2012), a charitable organization (Dingeman 2013) or an institutional department (Faraoni 2010; O'Sullivan 2011; Ponde 2013; Wang 2013), or the source was unspecified (Elnour 2009; Gurnaney 2011; Kendigelen 2014; Liu 2012; Lorenzo 2014; Marhofer 2004; Oberndorfer 2007; Ponde 2009; Sahin 2013; Tachibana 2012; Weintraud 2009). Two studies declared that they received help from the industry (equipment loan; Willschke 2005; Willschke 2006).

Excluded studies

We excluded one study (Triffterer 2012), which evaluated the cranial spread of caudally administered local anaesthetics in infants and children by means of real‐time ultrasonography. Ultrasound was used for all participants; therefore the study included no comparator, as was required by our inclusion criteria (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

Ongoing studies

We found seven ongoing trials (ACTRN12608000488303; ACTRN12613000595718; AT032012; NCT01136668; NCT01698268; NCT02321787; NCT02341144) that could fit our criteria for inclusion (Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Awaiting classification

No studies are awaiting classification.

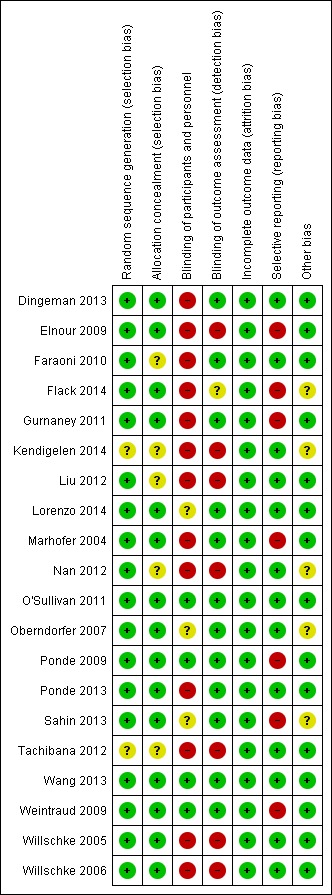

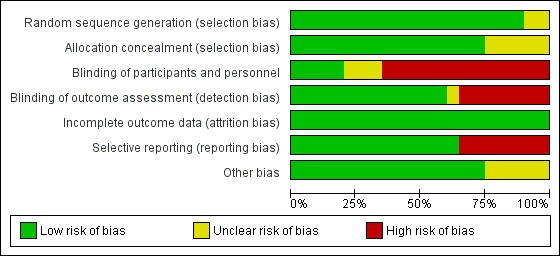

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias of the retained studies can be found in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Kendigelen 2014 was available as an abstract only. When information available in the report was insufficient, we rated the item as having high risk for blinding and as having unclear risk for all other items.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

We judged the sequence of randomization as appropriate for all studies except Kendigelen 2014 (abstract only) and Tachibana 2012 (for which no details were provided). Allocation concealment was judged as adequate for almost 75% of the included studies (Dingeman 2013; Elnour 2009; Flack 2014; Gurnaney 2011; Lorenzo 2014; Marhofer 2004; O'Sullivan 2011; Oberndorfer 2007; Ponde 2009; Ponde 2013; Sahin 2013; Wang 2013; Weintraud 2009; Willschke 2005; Willschke 2006). We rated this item as having unclear risk for the remaining six studies, one of which was available only as an abstract (Kendigelen 2014).

Blinding

We judged blinding of personnel taking care as adequate for less than 25% of the included studies (O'Sullivan 2011; Ponde 2009; Wang 2013; Weintraud 2009). We judged blinding of outcome assessors as adequate for over 50% of the studies (Dingeman 2013; Faraoni 2010; Gurnaney 2011; Lorenzo 2014; Marhofer 2004; O'Sullivan 2011; Oberndorfer 2007; Ponde 2009; Ponde 2013; Sahin 2013; Wang 2013; Weintraud 2009).

Incomplete outcome data

We judged all studies as adequate for this item.

Selective reporting

Data were not reported in intention‐to‐treat for more than 50% of the studies (Elnour 2009; Flack 2014; Gurnaney 2011; Marhofer 2004; Ponde 2009; Sahin 2013; Weintraud 2009). For three studies (Flack 2014; Marhofer 2004; Ponde 2009), pain scores were measured but were not provided.

Other potential sources of bias

We judged more than 75% of the studies (Dingeman 2013; Elnour 2009; Faraoni 2010; Gurnaney 2011; Liu 2012; Lorenzo 2014; Marhofer 2004; O'Sullivan 2011; Ponde 2009; Ponde 2013; Tachibana 2012; Wang 2013; Weintraud 2009; Willschke 2005; Willschke 2006) as exempt from other risks of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

Success rate (study authors’ definition)

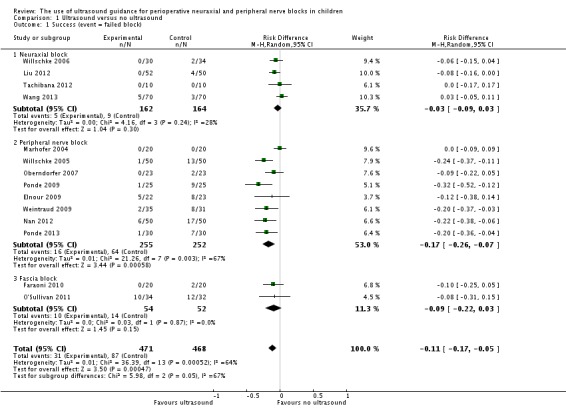

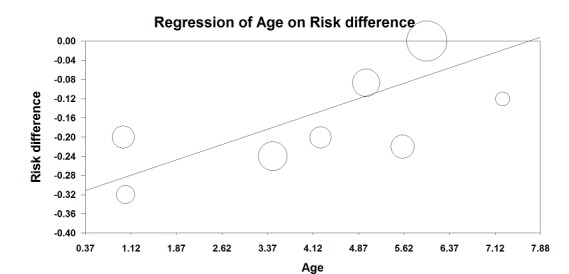

This outcome was available for 14 studies (Elnour 2009; Faraoni 2010; Liu 2012; Marhofer 2004; Nan 2012; O'Sullivan 2011; Oberndorfer 2007; Ponde 2009; Ponde 2013; Tachibana 2012; Wang 2013; Weintraud 2009; Willschke 2005; Willschke 2006) (939 participants). We included in Table 3 the definition used by study authors for failed blocks. Data are presented as 'decreased failure rate'. Ultrasound guidance decreased the failure rate (RD ‐0.11, 95% CI ‐0.17 to ‐0.05), with I2 statistic of 64% (Analysis 1.1). Egger's regression intercept showed the possibility of a small‐study effect (P value = 0.02; two‐sided test). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed no evidence of publication bias. This effect differed from one subgroup to another (Analysis 1.1; I2 = 67%). For peripheral nerve blocks, the effect was inversely proportional to the age of the participant; younger children benefited most from ultrasound guidance (P value = 0.003; Figure 4). If a failure rate of 25% is assumed (incidence in the study population; Table 1), the NNTB for peripheral nerve blocks would be six (95% CI 5 to 8). The optimal information size for a large trial for a 25% decrease in failure rate would be 1724 (862 per group) (alpha 0.05; beta 0.2; one‐sided test).

Table 1.

Definitions used by study authors for successful blockade

| Study | Type of block | Timing of blockade | Definition |

| Elnour 2009 | Axillary brachial plexus block | Under general anaesthesia before surgical incision in both groups | The procedure was considered a failure when:

|

| Faraoni 2010 | Penile nerve block | Under general anaesthesia before surgical incision in both groups | Ineffective block was defined as an increase in heart rate and mean arterial pressure > 20% above baseline values |

| Liu 2012 | Caudal block | Under general anaesthesia 10 to 15 minutes before surgical incision in both groups | Unsuccessful caudal puncture after 4 attempts (n = 2 in the control group) or signs of pain, such as body movement, tachycardia and tachypnoea during surgery |

| Marhofer 2004 | Infraclavicular brachial plexus block | Propofol sedation, 30 minutes before surgical incision in both groups | Procedure was considered a failure if ≥ 2 of the 4 nerves (ulnar, radial, median and musculocutaneous) could not be blocked effectively |

| Nan 2012 | Ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve blocks | Under general anaesthesia before surgical incision in both groups | Inadequate analgesia was defined as an increase of heart rate > 10% of baseline level, which needed to elevate the sevoflurane concentration to 3% to 4% during surgery |

| O'Sullivan 2011 | Penile nerve block | Under general anaesthesia ≥ 10 minutes before surgical incision in both groups | Procedure was considered a failure if a rise in heart rate or respiratory rate > 25% from baseline occurred in response to surgical stimulus |

| Oberndorfer 2007 | Sciatic and femoral nerve blocks | Under general anaesthesia ≥ 20 minutes before surgical incision in both groups | Procedure was considered a failure if a rise in heart rate > 15% of baseline value occurred at skin incision or during surgery |

| Ponde 2009 | Infraclavicular brachial plexus block | Under general anaesthesia before surgical incision in both groups | Procedure was considered a failure if a pain response to surgical stimulus occurred, defined as an increase in heart rate and arterial blood pressure > 20% of basal rate or non‐specific body movement in response to surgical stimulus and withdrawal of blocked limb in response to incision |

| Ponde 2013 | Sciatic and femoral nerve blocks | Under general anaesthesia ≥ 20 minutes before surgical incision in both groups | Procedure was considered a failure when:

|

| Tachibana 2012 | Thoracic epidural anaesthesia | Under general anaesthesia before surgical incision in both groups | Procedure was considered a failure if a participant complained of severe postoperative pain despite sufficient epidural administration of local anaesthetics |

| Wang 2013 | Caudal block | Under general anaesthesia ≥ 15 minutes before surgical incision in both groups | Procedure was considered a failure if a participant had motor or haemodynamic response, as indicated by an increase in mean arterial pressure or heart rate > 15% compared with baseline values obtained just before skin incision and subsequent to surgical procedure |

| Weintraud 2009 | Ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve blocks | Under general anaesthesia ≥ 15 minutes before surgical incision in both groups | Procedure was considered a failure if participant had an increase in heart rate or mean arterial blood pressure > 10% compared with baseline during operation |

| Willschke 2005 | Ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve blocks | Under general anaesthesia ≥ 15 minutes before surgical incision in both groups | Procedure was considered a failure if participant had an increase in heart rate or mean arterial pressure > 10% after skin incision or during surgery |

| Willschke 2006 | Thoracic or lumbar epidural anaesthesia | Under general anaesthesia ≥ 15 minutes before surgical incision in both groups | An increase in heart rate or blood pressure > 20% from baseline was considered to reflect inadequate analgesia and was managed by bolus administration of levobupivacaine 0.25% 0.3 millilitres per kilogram of body weight through the epidural catheter. If this was unsuccessful, the epidural block was considered to have failed |

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Ultrasound versus no ultrasound, Outcome 1 Success (event = failed block).

Figure 4.

Occurence of a failed peripheral nerve block for ultrasound guidance versus no ultrasound (log risk ratio of failure vs age in years). The superiority of ultrasound guidance was greater in younger children; P value = 0.003.

We retained only studies on peripheral nerve block for quality of evidence for this outcome. We did not downgrade the evidence for risk of bias because 50% or more of the included studies were judged as adequate for allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessors. We did not downgrade the quality for inconsistency because we could explain the heterogeneity (Analysis 1.1; Figure 4). We used only direct comparisons and downgraded the level by one for imprecision due to a low number of participants (below the optimal information size) (Guyatt 2011). We found no evidence of publication bias. We upgraded the evidence for a large effect size and for a dose‐response effect for success rate when ultrasound guidance was used for peripheral nerve blocks (Figure 4; the younger the child, the greater was the effect size). We found no reason to upgrade the level of evidence for confounding factors. We rated the level of evidence for this item as high.

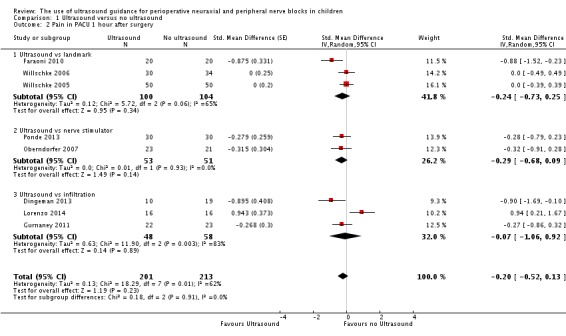

Pain scores in the post‐anaesthesia care unit (PACU)

Pain scores at one hour in the PACU were available for eight studies (Dingeman 2013; Faraoni 2010; Gurnaney 2011; Lorenzo 2014; Oberndorfer 2007; Ponde 2013; Willschke 2005; Willschke 2006) (414 participants). We did not find differences for pain scores at one hour in the PACU (SMD ‐0.20, 95% CI ‐0.52 to 0.13; I2 = 62%) when all studies were included (Analysis 1.2). Upon exclusion of one study (Lorenzo 2014), in which a transversus abdominis plane block was used for open pyeloplasty, ultrasound guidance would decrease pain scores in the PACU at one hour (SMD ‐0.29, 95% CI ‐0.54 to ‐0.04; I2 = 31%). Egger's regression intercept showed no evidence of a small‐study effect, and Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed no evidence of publication bias. When the study at lowest risk of bias among the studies for which pain scores were available as means and standard deviations (Ponde 2013; standard deviation in the control group 0.9) is considered, the mean reduction in pain at one hour in the PACU found in our meta‐analysis would be equivalent to 0.2 on the Children’s and Infants’ Postoperative Pain Scale (CHIPPS scale; 0 = no pain, 10 = maximal pain; Buttner 2000). On the basis of Gurnaney 2011 (mean value 4.35; standard deviation 3.1 for the control group), 238 (119 per group) would be required for a large trial, eliminating a difference of 1 on a score from 0 to 10 (alpha 0.05; beta 0.2; one‐sided test).

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Ultrasound versus no ultrasound, Outcome 2 Pain in PACU 1 hour after surgery.

For pain scores in the PACU at one hour, we did not downgrade the evidence for risk of bias because 50% or more of the included studies were judged as adequate for allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessors. We did not downgrade for inconsistency because the amount of heterogeneity was low (I2 = 31%) after exclusion of one study in which the type of block used might have not been ideal for the type of surgery performed (Lorenzo 2014). We used direct comparisons only. The optimal information size was achieved; therefore, we did not downgrade for imprecision. No evidence of publication bias, large effect size or dose response was found, and we did not identify other significant confounding factors to justify upgrading. We rated the level of evidence for this outcome as high.

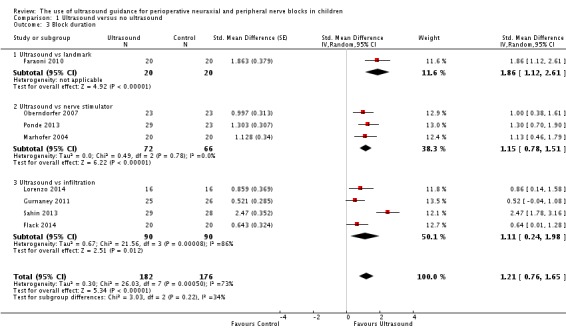

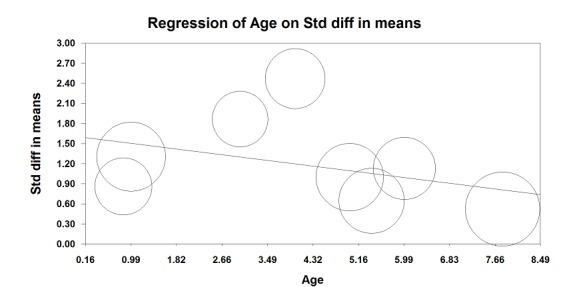

Block duration (study authors’ definition)

This outcome was available for eight studies (358 participants) (Faraoni 2010; Flack 2014; Gurnaney 2011; Lorenzo 2014; Marhofer 2004; Oberndorfer 2007; Ponde 2013; Sahin 2013). Ultrasound guidance increased block duration (SMD 1.21, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.65; I2 = 73% (Analysis 1.3). Egger's regression intercept showed no statistically significant evidence of a small‐study effect. Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed that one study might be missing to the right of mean for an adjusted point of estimate (1.31, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.75; random‐effects model). This effect was inversely proportional to age (P value = 0.04); younger children benefited most from ultrasound guidance (Figure 5). The mean prolongation of the block found in our meta‐analysis is equivalent to 62 minutes. On the basis of Ponde 2013 (mean time and standard deviation before request of the first analgesic in the control group 457 ± 51 minutes), eight participants (four per group) would be required in a simple trial to eliminate a 25% difference (alpha 0.05; beta 0.2; two‐sided test).

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 Ultrasound versus no ultrasound, Outcome 3 Block duration.

Figure 5.

Meta‐regression: time to request for the first analgesic versus age. Younger children are those in whom the effect of ultrasound guidance is larger (P value = 0.04).

For block duration, we did not downgrade the evidence for risk of bias because 50% or more of the included studies were judged as adequate for allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessors. We did not downgrade the evidence for inconsistency because we could explain the heterogeneity (Analysis 1.3; Figure 5). We included only direct comparisons. The optimal information size was achieved; therefore, we did not downgrade for imprecision. We did not downgrade for publication bias because correcting for this possibility would not change the conclusion. We upgraded the evidence by one because we found a large effect size (SMD 1.21 or > 0.8), and we upgraded the evidence because we found a dose‐response gradient (Figure 5; the younger the child, the larger was the effect size). We did not identify other significant confounding factors to justify upgrading. We rated the level of evidence for this item as high.

Secondary outcomes

Time to perform the procedure

This outcome was available for six studies (Elnour 2009; Liu 2012; O'Sullivan 2011; Tachibana 2012; Wang 2013; Willschke 2006) (362 participants). We found no differences between treatment groups when all studies were included in the analysis (SMD ‐0.77, 95% CI ‐1.57 to 0.02; I2 = 93%), and Egger's regression intercept showed no significant evidence of a small‐study effect. Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed the possibility of publication bias for an adjusted point of estimate of SMD ‐1.10 (95% CI ‐2.04 to ‐0.17). Ultrasound guidance decreased the time required to perform the block only when used as an out‐of‐plane technique (SMD ‐0.68, 95% CI ‐0.96 to ‐0.40; I2 = 0%) or as pre‐scanning before a neuraxial block (SMD ‐1.97, 95% CI ‐2.41 to ‐1.54; I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.4). A significant difference was noted among the three subgroups (I2 = 93%). This difference between ultrasound guidance versus no ultrasound guidance was equivalent to 94 seconds for an out‐of‐plane technique and 2.4 minutes when ultrasound guidance was used as pre‐scanning before a neuraxial block was performed. Based on Liu 2012 (mean time and standard deviation of the control group 3.2 ± 1.2 minutes), 46 participants (23 per group) would have been required, to eliminate a one‐minute difference (alpha 0.05; beta 0.2; two‐sided test).

Analysis 1.4.

Comparison 1 Ultrasound versus no ultrasound, Outcome 4 Time to perform the block.

For time to perform the procedure, we rated the quality for pre‐scanning before a neuraxial block. We downgraded the level of evidence for risk of bias because for the two studies retained, allocation concealment was unclear and blinding of the outcome assessor was not feasible for this outcome. We found no significant inconsistency (I2 < 25%). We included only direct comparisons and did not downgrade the level of evidence for imprecision because the optimal information size was achieved. Publication bias could not be assessed. We upgraded the quality of evidence because the effect size was large (SMD ‐1.97 or > 0.8). We did not identify significant confounding factors to justify upgrading or dose response. We rated the level of evidence as high.

Number of needle passes

This outcome was available for only two studies (Liu 2012; Tachibana 2012) (122 participants). Ultrasound guidance reduced the number of needle passes (SMD ‐0.90, 95% CI ‐1.27 to ‐0.52; I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.5). This difference was equivalent to a mean of 0.6 fewer needle passes per participant. On the basis of Liu 2012 (mean 1.6 and standard deviation 0.6), a trial would have to include 12 participants (six per group) to eliminate a difference of one needle pass (alpha 0.05; beta 0.2; two‐sided test).

Analysis 1.5.

Comparison 1 Ultrasound versus no ultrasound, Outcome 5 Number of needle passes.

For number of needle passes, we downgraded the level of evidence for risk of bias because for the two studies retained, allocation concealment was unclear and blinding of the outcome assessor was not feasible for this outcome. We found no significant inconsistency (I2 < 25%) and included only direct comparisons. We did not downgrade the level of evidence for imprecision because the optimal information size was achieved, and we upgraded the evidence because the effect size was large (SMD ‐0.90 or > 0.8). We did not identify significant confounding factors to justify upgrading or dose response. We rated the level of evidence as high.

Minor complications (bloody puncture)

This outcome was available for six studies (Marhofer 2004; Nan 2012; Oberndorfer 2007; Wang 2013; Willschke 2005; Willschke 2006) (490 participants). Ultrasound did not decrease the incidence of bloody punctures (RD ‐0.02, 95% CI ‐0.06 to 0.02; I2 = 53%; Analysis 1.6). Eger's regression intercept showed no evidence of a small‐study effect, and Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed the possibility of publication bias for an adjusted point of estimate (RD ‐0.04, 95%CI ‐0.04 to 0.01) (random‐effects model). Only two trials studied the effect of ultrasound for neuraxial blocks (Wang 2013; Willschke 2006) and showed a moderate amount of heterogeneity (RD ‐0.07, 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.04; I2 = 68%). Given a basal rate of 13.5% for bloody puncture during neuraxial block in children, the optimal information size for a large trial for a 25% decrease would be 2226 (1113 per group).

Analysis 1.6.

Comparison 1 Ultrasound versus no ultrasound, Outcome 6 Bloody puncture.

For bloody punctures, we did not downgrade the evidence for risk of bias because 50% or more of the included studies were judged as adequate for allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessors. We downgraded the quality by one for inconsistency (I2 > 50%). We used only direct comparisons and downgraded the level by one for imprecision due to a low number of participants (below the optimal information size). We did not downgrade the level for publication bias because applying a correction would not modify the conclusion. We found no evidence of a large effect size or dose response gradient, and we did not identify any significant confounding factors to justify upgrading. We rated the level of evidence as low.

Major complications

No major complications were reported in any of the included studies (see Table 4).

Table 2.

Complications

| Peripheral nerve block | |||

| Study | Type of block | Minor complications | Major complications |

| Elnour 2009 | Axillary brachial plexus block | No intravascular injection Local bruising 2/17 in the ultrasound group vs 3/15 in the nerve stimulator group Local axillary pain 3/17 in the ultrasound group and 8/15 in the nerve stimulator group Transient post‐block paraesthesia 2/17 in the ultrasound group and 4/15 in the nerve stimulator group (which resolved within 5 days as reported by parents and participants in the follow‐up surgical clinic 1 week later) |

Major complications (e.g. unintentional intravascular injection, persistent neurological deficit) did not occur in either group |

| Marhofer 2004 | Infraclavicular brachial plexus block | No clinical signs of inadvertent puncture of major vessels | No clinical signs of pneumothorax, infection or haematoma |

| Nan 2012 | Ilioinguinal or iliohypogastric nerve block | 1 case in group no ultrasound had needle puncturing into blood vessels | No other adverse event was observed in the 2 groups |

| Oberndorfer 2007 | Sciatic and femoral nerve blocks | No clinical signs of inadvertent puncture of major vessels | No clinical signs of nerve damage, infection or haematoma |

| Ponde 2009 | Infraclavicular brachial plexus block | No complications were related to the regional anaesthetic technique | No complications were related to the regional anaesthetic technique |

| Ponde 2013 | Sciatic and femoral nerve blocks | Not reported | Not reported |

| Weintraud 2009 | Ilioinguinal‐iliohypogastric nerve block | Not reported | The ultrasound‐guided technique resulted in higher Cmax (SD) and AUC values (Cmax: 1.78 (0.62) vs 1.23 (0.70) mcg/mL, P value < 0.01; AUC: 42.4 (15.9) vs 27.2 (18.1) mcg 30 min/mL, P value < 0.001). No signs of clinical toxicity |

| Willschke 2005 | ilioinguinal block | All anaesthetic procedures were uneventful; no clinical evidence of complications such as small bowel or major vessel puncture | All anaesthetic procedures were uneventful |

| Fascia block | |||

| Study | Type of block | Minor complications | Major complications |

| Dingeman 2013 | Rectus sheath block | No adverse events requiring immediate medical attention associated with the surgical procedure or the postoperative course were reported in either group | No adverse events requiring immediate medical attention associated with the surgical procedure or the postoperative course were reported in either group |

| Faraoni 2010 | Penile nerve block | Not reported | Not reported |

| Flack 2014 | Rectus sheath block | Not reported | Peak plasma bupivacaine concentration was higher following ultrasound rectus sheath block: median: 631.9 ng/mL (IQR: 553.9 to 784.1 vs 389.7 ng/mL, IQR: 250.5 to 502.7; P value = 0.002). Time to peak concentration was longer in the USGRSB group (median 45 minutes, IQR: 30 to 60 vs 20 minutes, IQR: 20 to 45; P value = 0.006). No measured plasma bupivacaine concentration exceeded 1 mcg/mL. No adverse events and no clinical evidence of toxicity were noted |

| Gurnaney 2011 | Rectus sheath block | Not reported | Not reported |

| Kendigelen 2014 | Transersus abdominis plane block | No adverse effects related to the transversus abdominis plane block were identified | No adverse effects related to the transversus abdominis plane block were identified |

| Lorenzo 2014 | Transersus abdominis plane block | Not reported | No local anaesthetic‐specific adverse events were noted |

| O'Sullivan 2011 | Penile nerve block | No complications of either technique were reported | No complications of either technique were reported |

| Sahin 2013 | Transersus abdominis plane block | Not reported | Not reported |

| Neuraxial block | |||

| Study | Type of block | Minor complications | Major complications |

| Liu 2012 | Caudal | Not reported | Not reported |

| Tachibana 2012 | Thoracic epidural | Not reported | No participants experienced severe side effects |

| Wang 2013 | Caudal | Bloody puncture had an incidence of 18.6% in group landmarks and 5.7% in group ultrasound (P value < 0.05) | No dural puncture nor systemic reaction to LA was reported in both groups |

| Willschke 2006 | Thoracic (n = 59) or lumbar (n = 5) epidural | Blood was aspirated in 1 child in the control group | No dural puncture occurred in either group |

AUC: area under the curve for blood concentrations of local anaesthetics

Cmax: maximal blood concentration of local anaesthetic

IQR: interquartile range

LA: local anaesthetic

N: number

mcg: microgram

SD: standard deviation

USGRSB: ultrasound‐guided rectus sheath block

Discussion

In their large prospective study, Polaner et al (Polaner 2012) found that failed block and inadvertent vascular puncture were common problems encountered in paediatric regional anaesthesia. Our meta‐analysis showed that ultrasound guidance increases the success rate (or decreases the failure rate) (Table 1). However, results revealed some heterogeneity when all studies were included. The increased success rate was most evident for peripheral nerve block, for which the amplitude of the effect size (difference between ultrasound guidance and no ultrasound guidance) was inversely proportional to the age of the participant; younger children benefited most from ultrasound guidance (Figure 4). Ultrasound guidance also significantly prolonged block duration (longer time to first request of an analgesic); here again the effect was more evident in studies performed in younger participants (Figure 5). Thus, the younger the child, the more likely he/she is to benefit from ultrasound guidance. Findings of our review did not allow us to determine the exact age at which ultrasound will no longer be useful.

Pain scores at one hour after surgery were reduced when ultrasound guidance was used; however, this difference probably was not clinically relevant (equivalent to ‐0.2 on a scale from 0 to 10). For this outcome, we excluded one study from the analysis (Lorenzo 2014). The amount of heterogeneity was moderate (62%) when all studies were included and low (31%) when the study from Lorenzo et al was excluded. Lorenzo et al compared transversus abdominis plane blocks (0.4 mL/kg bupivacaine 0.25% with epinephrine) versus wound infiltration for open pyeloplasty (both before surgical incision). All surgeries followed a similar muscle‐splitting access by which the tip of the ipsilateral 12th rib was used as a landmark for incisions systematically smaller than 2 to 2.5 cm. Involved dermatomes were approximately T7 to T10 (Lorenzo 2014). The exact location of the injection for the transversus abdominis plane block (subcostal/iliac or mid‐axillary/posterior area) was not pre‐specified. The study was stopped prematurely at the interim analysis after enrolment of one‐third of the planned total recruitment on the basis that the transversus abdominis plane block was ineffective for this type of surgery. This block has been received with mixed degrees of enthusiasm in the literature because of its high variability in numbers and in the distribution of dermatoma blocked depending on the exact site of injection and the dose or volume used (Borglum 2012; Lee 2010). Therefore, the distribution of the sensory block may not have covered the surgical incision in the study by Lorenzo et al. For this reason, we chose to exclude this study from the analysis. In our opinion, the failure was specific to this type of block for this specific type of surgery and should not be considered failure of ultrasound guidance.

Time to perform the block was reduced by ultrasound guidance when used as an out‐of‐plane technique or as pre‐scanning before neuraxial block. The mean difference was small ‐ equivalent to 2.4 minutes when used as pre‐scanning. Ultrasound guidance accordingly reduced the number of needle passes required to perform the block (0.6 per procedure).

We could not demonstrate a difference in minor complications (bloody punctures), but our findings might show a trend towards a reduction in complications for the subgroup of studies in which ultrasound guidance was used for neuraxial block. Additional data are required before firm conclusions can be drawn.

None of the included studies reported major complications (Table 4). As a result of the extremely low incidence of major complications associated with paediatric regional anaesthesia, the incidence of these very rare events is best evaluated by large prospective studies.

Summary of main results

Ultrasound guidance increases the success rate of regional anaesthesia and decreases pain at one hour after surgery, time to perform the block and the number of needle passes. It also increases block duration (Table 1). For the success rate of peripheral nerve block and block duration, the effect was inversely correlated with age, meaning that the younger the child, the more likely it is that he/she will benefit from ultrasound guidance (Figure 4; Figure 5). The reduction in pain scores at one hour after surgery was small and may not have been clinically relevant. No major complications were reported in any of the included studies.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Our review included both peripheral and neuraxial blocks in children from birth to 18 years of age undergoing a wide variety of surgeries. For this reason, we had to subgroup the studies according to pre‐defined criteria in our heterogeneity exploration. However, we are confident that the evidence obtained is sufficient to allow us to draw valid conclusions as reflected by the high level of evidence for five of our outcomes (success, pain at one hour, block duration, time to perform the procedure and number of needle passes; Table 1). Major complications could not be evaluated in our review because of their extremely rare incidence. More data would be useful regarding the possibility of decreased bloody puncture when ultrasound is used for neuraxial block.

Quality of the evidence

Details of the reasons justifying upgrading or downgrading the quality of evidence are given in the results section under effects of intervention (Effects of interventions). We rated the quality of evidence as high for success, pain at one hour, block duration, time to perform the procedure and number of needle passes. We rated the quality as low for minor complications (Table 1).

Potential biases in the review process

As the result of our extensive search, we are confident that we included the available literature on this topic. Studies included were all relatively recent (from 2004 to 2014) and therefore probably reflect quite well actual medical practice and technology. Although doses and volumes of injected solution varied, they seemed appropriate for the surgical indications for which they were used in most studies.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Unlike the Cochrane review on ultrasound guidance for peripheral nerve block in adults, we could not demonstrate a reduction in the rate of inadvertent vascular puncture (Walker 2009). However, we believe that additional paediatric data are required before firm conclusions can be drawn. Our finding that increased success and longer duration of block was inversely correlated with the age of participants represents interesting new information. We also found that ultrasound reduces the time to perform the block, but in our review, this proved true only when ultrasound was used with an out‐of‐plane technique or as pre‐scanning before neuraxial block.

Authors' conclusions

Evidence of high quality suggests that ultrasound guidance increases the success rate and increases block duration for regional blockade in children. Although we do not have enough information to state a specific age limit, evidence indicates that improved success rate and increased block duration were more pronounced in studies including younger children. Ultrasound guidance also seems to lead to slight improvement in pain scores at one hour after surgery and decreases time to perform the block in some situations (pre‐scanning before neuraxial block and out‐of‐plane techniques). The amplitude of the effect for these two outcomes was very small and therefore may not be clinically relevant. Ultrasound guidance also decreases the number of needle passes, but as a vast majority of blocks in children are performed with the child under deep sedation or general anaesthesia, the clinical relevance of this finding is arguable. No major complications were reported in any of the included studies. The incidence of lasting severe neurological complications is fortunately very low; therefore, it is unlikely that an optimal sample size could ever be achieved for this outcome with RCTs. No local anaesthetic toxicity was reported in the included studies, but here again, the number of participants included in our review is probably insufficient to eliminate a difference in the incidence of local anaesthetic toxicity when ultrasound guidance is used for regional blockade in children. Altogether, whether or not these differences justify the extra cost of ultrasound guidance may need to be evaluated.

Additional studies are required to support or refute the use of regional anaesthesia for postoperative pain in children (Suresh 2014). For peripheral nerve blocks, we found only studies on single‐shot blocks. If ultrasound guidance also improves the success rate for continuous peripheral nerve blocks in children, differences in pain and opioid‐related adverse effects after surgery may become more clinically relevant. Studies conducted to evaluate the cost/benefit ratio of ultrasound guidance versus nerve stimulator, while taking into account savings of time spent in the operating room (blocks are often performed with the child asleep in the operating room), could prove helpful. Finally, additional data are required before it can be determined whether ultrasound guidance can reduce the incidence of bloody puncture during neuraxial blockade in children.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Jason Hayes, David Faraoni, Harshad Gurnaney, Peter Marhofer, Stephan Kettner, Michael O'Sullivan, Vrushali Ponde and Gildasio S. De Oliveira Jr., who provided additional information on their studies or took the time to inform us that their original data were no longer available.

We are also in debt to Jiang Jia for translation of Liu 2012 and Nan 2012.

Finally, we would like to thank Rodrigo Cavallazzi (Content Editor); Jing Xie (Statistical Editor); Kevin Walker and Vaughan L Thomas (Peer Reviewers) and Sheila Page (Consumer Referee) for help and editorial advice provided during preparation of this systematic review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library) search strategy