Abstract

Background

An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is an abnormal ballooning of the major abdominal artery. Some AAAs present as emergencies and require surgery; others remain asymptomatic. Treatment of asymptomatic AAAs depends on many factors, but an important one is the size of the aneurysm, as risk of rupture increases with aneurysm size. Large asymptomatic AAAs (greater than 5.5 cm in diameter) are usually repaired surgically; very small AAAs (less than 4.0 cm diameter) are monitored with ultrasonography. Debate continues over the appropriate roles of immediate repair and surveillance with repair on subsequent enlargement in people presenting with asymptomatic AAAs of 4.0 cm to 5.5 cm diameter. This is the third update of the review first published in 1999.

Objectives

To compare mortality, quality of life, and cost effectiveness of immediate surgical repair versus routine ultrasound surveillance in people with asymptomatic AAAs between 4.0 cm and 5.5 cm in diameter.

Search methods

For this update, the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator searched the Specialised Register (February 2014) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2014, Issue 1). We checked reference lists of relevant articles for additional studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials in which men and women with asymptomatic AAAs of diameter 4.0 cm to 5.5 cm were randomly allocated to immediate repair or imaging‐based surveillance at least every six months. Outcomes had to include mortality or survival.

Data collection and analysis

Three members of the review team independently extracted the data, which were cross‐checked by other team members. Risk ratios (RR) (endovascular aneurysm repair only), hazard ratios (HR) (open repair only), and 95% confidence intervals based on Mantel‐Haenszel Chi2 statistic were estimated at one and six years (open repair only) following randomisation. We included all relevant published studies in this review.

Main results

For this update, four trials with a combined total of 3314 participants fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Two trials compared surveillance with immediate open repair; two trials compared surveillance with immediate endovascular repair. Overall, the risk of bias within the included studies was low and the quality of the evidence high. The four trials showed an early survival benefit in the surveillance group (due to 30‐day operative mortality with surgery) but no significant differences in long‐term survival (adjusted HR 0.88, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.75 to 1.02, mean follow‐up 10 years; HR 1.21, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.54, mean follow‐up 4.9 years; HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.93, median follow‐up 32.4 months; HR 1.01, 95% CI 0.49 to 2.07, mean follow‐up 20 months). A pooled analysis of participant‐level data from two trials (with a maximum follow‐up of seven to eight years) showed no statistically significant difference in survival between immediate open repair and surveillance (propensity score‐adjusted HR 0.99; 95% CI 0.83 to 1.18), and that this lack of treatment effect did not vary by AAA diameter (P = 0.39) or participant age (P = 0.61). The meta‐analysis of mortality at one year for the endovascular trials likewise showed no significant association (RR at one year 1.15, 95% CI 0.60 to 2.17). Quality‐of‐life results among trials were conflicting.

Authors' conclusions

The results from the four trials to date demonstrate no advantage to immediate repair for small AAA (4.0 cm to 5.5 cm), regardless of whether open or endovascular repair is used and, at least for open repair, regardless of patient age and AAA diameter. Thus, neither immediate open nor immediate endovascular repair of small AAAs is supported by currently available evidence.

Plain language summary

Surgery for small abdominal aortic aneurysms that do not cause symptoms

An aneurysm is a ballooning of an artery (blood vessel), which, in the case of an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), occurs in the major artery in the abdomen (aorta). Ruptured AAAs cause death unless surgical repair is rapid, which is difficult to achieve. Surgery is considered necessary for people with aneurysms of more than 5.5 cm in diameter or who have associated pain, to relieve symptoms and to reduce the risk of rupture and death. However, risks are associated with surgery. Surgical repair consists of insertion of a prosthetic inlay graft, either by open surgery or endovascular repair.

Small asymptomatic AAAs are at low risk of rupture and are monitored through regular imaging so they can be surgically repaired if they subsequently enlarge. This review identified four well‐conducted, controlled trials that randomised 3314 participants with small (diameter 4.0 cm to 5.5 cm) asymptomatic AAAs to immediate repair or regular, routine ultrasounds to check for aneurysm growth (surveillance). Among the patients randomised to surveillance, the aneurysm was repaired if it was enlarging, reached 5.5 cm in diameter, or became symptomatic. The four trials showed an early survival benefit in the surveillance group because of the number of deaths within 30 days of surgery (operative mortality). The trials did not show a meaningful difference in long‐term survival between immediate repair and selective surveillance over the three to eight years of follow‐up. Some 31% to 75% of the participants randomised to surveillance eventually had the aneurysm repaired. Overall, the risk of bias within the included studies was low and the quality of the evidence high. The results from the four trials conducted to date suggest no overall advantage to immediate surgery for small AAAs (4.0 cm to 5.5 cm). A pooled analysis of the two trials comparing immediate open surgical repair to surveillance demonstrated that this result holds true regardless of patient age or aneurysm size (within the range of 4.0 cm to 5.5 cm diameter). Furthermore, the more recent trials, which focused on the efficacy of endovascular repair, also failed to show a benefit over surveillance. Quality‐of‐life results among trials were conflicting. Thus, neither immediate open nor immediate endovascular repair of small AAAs is supported by the current evidence.

Background

Description of the condition

An aneurysm is an abnormal dilatation of an artery. This can occur in any artery including the abdominal aorta, below the branches to the renal arteries (Ernst 1993; Stonebridge 1996). Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) are rare in people under 50 years of age, but thereafter prevalence increases sharply with increasing age (Lederle 1997; Lederle 2000). AAAs occur in about 5% of men aged 65 to 74 years and are approximately 3 times more common in men than in women (Lederle 1997a; Lederle 2000). Low prevalence rates have been observed for African‐American males compared to white males, and black race has been identified as having a strong negative association with AAA (Lederle 1997; Lederle 2000).

The cause of AAA is likely to be multifactorial (Shah 1997). It may result from a change in the composition of the collagen and elastin matrix in the media of the arterial wall due to excessive proteolysis. AAAs often coincide with atherosclerosis in the aortic wall, but it is not known if atherosclerosis is involved in the pathogenesis of aneurysms. Inflammation of the aortic wall also appears to be influential. The main well‐established risk factor is cigarette smoking, with smokers having a two‐ to three‐fold increased risk of AAA compared to nonsmokers (Lederle 1997; Lederle 2003). Aneurysms also occur more frequently in close relatives of people who have suffered an AAA, but a mode of inheritance has not been demonstrated (Ballard 1999).

The progression of AAA can vary considerably (Ernst 1993). Some people remain asymptomatic (no evidence of significant groin, back, or abdominal pain) throughout life, while others present with symptoms such as back pain, pulsating abdominal mass, or pulsating popliteal/femoral artery, or as emergencies following rupture. The risk of rupture increases with aneurysm size; mortality following rupture is high (approximately 60% die before reaching hospital) (Ballard 1999).

Description of the intervention

Ruptured AAAs require emergency surgical repair, which has a mortality rate of 40% to 50%. The outcome of surgery is highly dependent on the patient's presenting features, including general clinical condition (Ernst 1993; Stonebridge 1996). Surgery for patients with symptomatic AAAs is considered necessary to relieve symptoms and to reduce the risk of rupture and death.

In the case of asymptomatic AAAs, however, management depends on the size of the aneurysm. To date, no medical therapy has been shown to reduce the rate of size change or risk of rupture among people with asymptomatic AAAs (Ballard 1999; Ernst 1993; UKSAT); however, randomised controlled trials examining the efficacy of exercise, doxycycline, and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in limiting AAA progression are under way (Golledge 2011). Surgery is performed on larger aneurysms (greater than 5.5 cm in diameter), while very small aneurysms (less than 4.0 cm in diameter), in which the risk of rupture is low, are monitored for growth through regular imaging, usually ultrasonography. For small AAAs (4.0 cm to 5.5 cm diameter), there has been considerable debate as to the most beneficial course of treatment, that is immediate repair versus surveillance and selective repair of AAAs that subsequently enlarge (Lederle 1996). Much of this debate centres around the uncertainty of risk of rupture for small AAAs.

How the intervention might work

A literature review conducted by a RAND Corporation panel in 1991 assessed the appropriateness and necessity of surgery for AAAs and found reports of risk of rupture, based on referral case series, as high as 5% per year for AAAs greater than 5.0 cm and 3% to 5% per year for AAAs equal to or less than 5.0 cm (Ballard 1992), which supports arguments in favour of the aggressive approach of immediate repair. Population data, however, suggest that risk of rupture for AAAs less than 5.0 cm is less than 1% per year, under which scenario the merits of selective surveillance are apparent (Ballard 1992; Nevitt 1989). Recent evidence suggests the risk of rupture can be lowered even further through pharmacologic management, such as use of statins and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (Hackam 2006; Mosorin 2008; Powell 2008). Similarly, population studies suggest that early reports of expansion rates of approximately 0.4 cm per year for AAAs between 4.0 cm and 6.0 cm in diameter had overestimated growth by approximately 0.2 cm per year (Bernstein 1984; Nevitt 1989), inaccurately favouring aggressive intervention. A recent meta‐analysis pooling individual patient data for more than 15,000 patients included in studies of small AAA growth and rupture found increasing growth rates with increasing diameters, but estimated that to control the risk of rupture to less than 1%, a surveillance interval of only once every 8.5 years (95% confidence interval (CI) 7.0 to 10.5) would be necessary in a man with a 3.0 cm AAA; or once in 17 months (95% CI 14 to 22) in a man with a 5.0 cm AAA (Bown 2013).

Why it is important to do this review

The 'grey area' of care for small AAAs, resulting from the uncertainty surrounding the risk of rupture versus the risk of intervention and expansion rates identified by the RAND panel, highlighted the need for randomised controlled trials comparing immediate surgery and selective surveillance as treatment options. This led to the design of the Aneurysm Detection and Management (ADAM) trial (ADAM), the United Kingdom Small Aneurysm Trial (UKSAT) (UKSAT), and the Canadian Trial, which used open surgery to perform the repairs. Later, when endovascular repair became available, the Comparison of Surveillance Versus Aortic Endografting for Small Aneurysm Repair (CAESAR) and the Positive Impact of Endovascular Options for Treating Aneurysms Early (PIVOTAL) were conducted, using endovascular repair as the surgical option. Most recently, pooling the participant‐level data from the ADAM and UKSAT trials has enabled the investigation of the possibility that age or AAA diameter might affect survival differences between immediate repair and surveillance (Filardo 2013; Filardo 2014). As the current guidelines for management of AAA state, “[d]ebate remains for patients presenting with AAAs between 4.0 cm and 5.4 cm regarding the most appropriate role for either immediate treatment or surveillance and selective repair for those aneurysms that subsequently enlarge beyond 5.4 cm” (Chaikof 2009). This review synthesised the existing evidence regarding those management strategies.

Objectives

To compare mortality, quality of life, and cost effectiveness of immediate surgical repair versus routine ultrasound surveillance in people with asymptomatic AAAs between 4.0 cm and 5.5 cm in diameter.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in which participants were randomly allocated to immediate surgery versus ultrasound surveillance.

Types of participants

Men or women of any age with an asymptomatic AAA. The aneurysm was restricted to the abdominal aorta distal to the renal arteries. The maximum antero‐posterior diameter, measured using ultrasound or computerised tomography (CT) scanning, must have been at least 4.0 cm and less than 5.5 cm. The aneurysm should have been non‐tender on examination and the patient assessed as generally fit for surgery.

Types of interventions

Surgical repair of the aneurysm consisting of insertion of a prosthetic inlay graft either by open surgery (abdominal or retroperitoneal route) or by endovascular repair. Surveillance of the maximum antero‐posterior diameter was to be performed regularly, with a maximum interval of six months.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The outcome measures included at least one of the following:

life expectancy, expected number of years of life remaining following randomisation;

mortality, death rate during a specified period of time following randomisation;

quality of life, a standard generic measure using a validated instrument encompassing typical domains such as pain, health perceptions, mental health, and physical and social functioning.

Secondary outcomes

The costs, from trial data, a specific survey, or routine statistics, which might have included:

direct hospital costs, all hospital costs attributable to inpatient stays, surgery, and outpatient attendances including ultrasound surveillance;

other health service costs, non‐hospital costs such as general practitioner attendances, ambulance transfers, convalescence;

societal costs, non‐health service costs to society such as loss of productivity, time off work, sickness benefit.

The following outcome measures were of interest but were not included in a meta‐analysis because they were relevant to only one arm of a trial or were of doubtful validity:

cause of death, mortality by underlying cause of death according to the International Classification of Diseases;

operative mortality, measured as 30‐day or 'in hospital' mortality;

rupture, rate of aneurysm rupture diagnosed at postmortem, operation, or certified as the underlying cause of death.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For this update, the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator (TSC) searched the Specialised Register (February 2014) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTAL) (2014, Issue 1), part of The Cochrane Library (www.thecochranelibrary.com). See Appendix 1 for details of the search strategy used to search CENTRAL. The Specialised Register is maintained by the TSC and is constructed from weekly electronic searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED, and through handsearching relevant journals. The full list of the databases, journals, and conference proceedings which have been searched, as well as the search strategies used, are described in the (Specialised Register) section of the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group module in The Cochrane Library (www.thecochranelibrary.com).

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of relevant studies. We supplemented the searches with information from experts in the field and from handsearches of the following conference proceedings.

The International Society for Vascular Surgery Congress (through to 2011)

The Society for Vascular Surgery Annual Meeting (through to 2013)

The Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery Annual Symposium (through to 2014)

The European Society for Vascular Surgery Annual Meeting (through to 2013)

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

All review authors identified the trials comparing surgical repair versus selective surveillance for small AAAs.

Data extraction and management

Three members of the research team (GF, MAMM, BdG) abstracted the data, which other team members (DJB and JTP) cross‐checked. The data collected on each trial included information on the participants (age and sex distribution, aneurysm size), the interventions (graft type, frequency of ultrasound surveillance), and the outcomes (as specified in Criteria for considering studies for this review).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The review authors discussed each of the trials and agreed on their inclusion or exclusion based on the adequacy of the random allocation, attainment of adequate sample size, and completeness of follow‐up. The nature of the interventions did not permit participants or observers to be blinded, and so this lack did not disqualify trials from inclusion. In addition, we assessed the risk of bias of the included studies using the 'Risk of bias' tool as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).The following domains were assessed and judged to be at low risk of bias, high risk of bias, or unclear risk of bias: selection bias, performance and detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other sources of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We estimated risk ratios (RR) (endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) only), hazard ratios (HR) (open repair only) and 95% CIs based on Mantel‐Haenszel Chi2 statistic to assess the efficacy of the intervention at one year (endovascular and open repair) and six years (open repair only) following randomisation. The HRs reported for open repair were estimated from a participant‐level meta‐analysis that was executed to summarize evidence from the UKSAT and ADAM trials (Filardo 2013; Filardo 2014).

Unit of analysis issues

Each participant with an AAA of diameter 4.0 cm to 5.5 cm who received immediate surgical repair versus routine ultrasound surveillance was the unit of analysis.

Dealing with missing data

None of the studies included in this review used single or multiple imputation procedures to deal with missing data. However, the incidence of missing data was very low.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. We considered I2 values of 50% or greater to indicate substantial heterogeneity. Moreover, we used a Chi2 test to assess heterogeneity in the participant‐level meta‐analysis we executed to summarise evidence from the UKSAT and ADAM trials. If we identified heterogeneity, we explored reasons for it.

Assessment of reporting biases

All included studies published findings on the main study outcome of this review.

Data synthesis

RRs (EVAR only), HRs (open repair only), and 95% CIs based on Mantel‐Haenszel Chi2 statistic were estimated. We calculated the RR summary estimates by employing a fixed‐effect model meta‐analyses approach. We estimated HRs from a participant‐level meta‐analysis we executed to summarise evidence from the UKSAT and ADAM trials (Filardo 2013; Filardo 2014).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We analysed and presented separately studies comparing immediate EVAR to surveillance and studies comparing immediate open repair to surveillance. Given the differences in surgical techniques, we did not estimate the overall effect associated with immediate repair irrespective of the type of surgery compared to surveillance. Accordingly, we executed tests for heterogeneity for each meta‐analysis, one reporting on immediate EVAR versus surveillance and one reporting on immediate open repair versus surveillance.

Sensitivity analysis

We included all relevant published studies in this review; accordingly, we did not carry out a sensitivity analysis.

Results

Description of studies

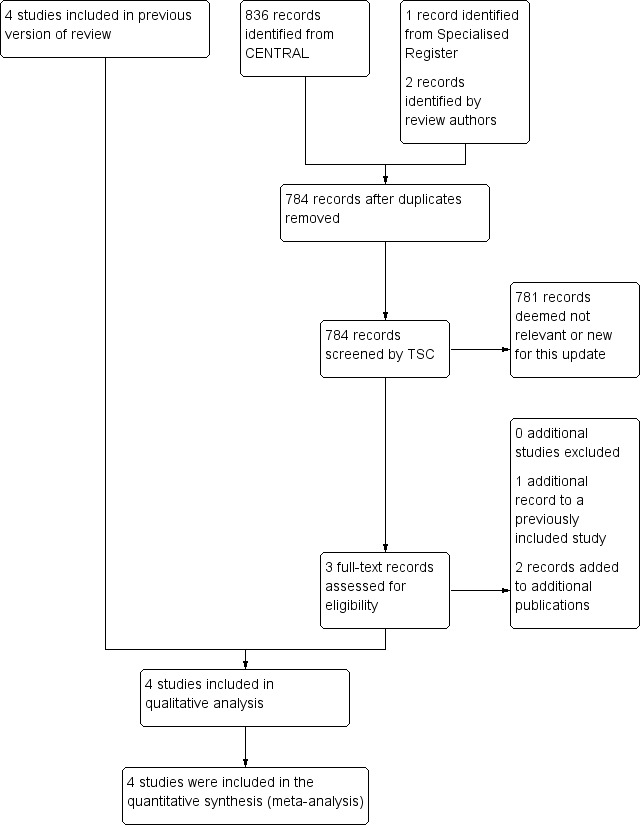

See Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Results of the search

We identified four relevant randomised controlled trials from the electronic searches (ADAM; CAESAR; PIVOTAL; UKSAT) and one from personal communication (Canadian Trial).

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies. Four randomised controlled trials, the UKSAT, ADAM, CAESAR, and PIVOTAL trials, fulfilled the criteria for consideration in the present review. We used results from analyses of pooled participant‐level data from the UKSAT and ADAM trials in the comparison of immediate open repair to selective surveillance (Filardo 2013; Filardo 2014).

All four trials enrolled people with small (4.0 cm to 5.5 cm) non‐tender, asymptomatic AAAs and who were considered fit for surgery. The trials excluded people who were considered unfit for surgery, had symptoms associated with the aneurysm, were unable to attend the follow‐up visit, or were unable to give informed consent. The ADAM study further excluded people who had received a revascularization procedure within three months of enrolment, had a myocardial infarction within six months of enrolment, or were expected to survive less than five years because of invasive cancer or another life‐threatening disease. The CAESAR trial, besides excluding those people not anatomically suitable for endovascular repair, further excluded people who had severe co‐morbidities or a suprarenal or thoracic aorta equal to or greater than 4.0 cm in diameter, or that needed urgent repair. The PIVOTAL study further excluded people who had had an abdominal or thoracic repair, an aneurysm originating equal to or less than 1.0 cm from the most distal main renal artery, life expectancy of less than 3 years, Society for Vascular Surgery score greater than 2 with the exception of age and controlled hypertension, baseline serum creatinine level greater than 2.5 mg/dL, or when the person did not meet the indications for use of the endograft device.

Lastly, age inclusion criteria were 50 to 79 years, 50 to 79 years, 40 to 90 years, and 60 to 76 years for the ADAM, CAESAR, PIVOTAL, and UKSAT studies, respectively. Despite the relatively wider age range eligible for inclusion in the ADAM, CAESAR, and PIVOTAL trials, the majority of the participants fell within the same age range as the UKSAT trial: 88%, approximately 70%, and approximately 70%, respectively. This is perhaps unsurprising given that AAA prevalence is much higher in older age groups.

Study designs were similar, with participants randomly allocated to either immediate surgery or selective surveillance. In the four trials, most participants assigned to the immediate‐surgery group received endovascular or standard open repair within six weeks of randomisation. Likewise, in all four trials, participants assigned to selective surveillance were followed, without repair, at regular intervals (at minimum once every six months), and surgery was performed within six weeks if a) the aneurysm reached 5.5 cm in diameter; or b) the aneurysm enlarged by a minimum of 0.7 cm in six months (ADAM), 1.0 cm in one year (UKSAT), greater than 1.0 cm in one year (CAESAR), or a minimum of 0.5 cm between two six‐month assessments (PIVOTAL); or c) the aneurysm became symptomatic. Adherence to assigned treatment was very high across the four trials (UKSAT had the lowest adherence rate at 92.6%), and at the end of the trials, mortality status was ascertained in 100% (ADAM; PIVOTAL; UKSAT) and 98% (CAESAR) of participants. Approximately 62%, 48%, 31%, and 75% of the participants in the selective‐surveillance group of the ADAM, CAESAR, PIVOTAL, and UKSAT studies, respectively, eventually underwent aneurysm repair.

In total, 3314 participants with asymptomatic AAAs of antero‐posterior diameter 4.0 cm to 5.5 cm were randomised to immediate surgery (n = 1680: 569 in ADAM, 182 in CAESAR, 366 in PIVOTAL, and 563 in UKSAT; 50.7%) or routine ultrasound or computed tomography surveillance every six months (three months if diameter 5.0 cm to 5.5 cm in ADAM and UKSAT) (n = 1634: 567 in ADAM, 178 in CAESAR, 362 in PIVOTAL, and 527 in UKSAT; 49.3%). The primary outcome of the included studies was all‐cause mortality and secondary outcomes were AAA‐related death, morbidity and quality of life. Follow‐up for vital status ranged from 3.5 to 8.0 years (mean 4.9 years) in the ADAM trial; median 32.4 months (interquartile range (IQR) 21.0 to 44.1) in the immediate endovascular repair group and 30.9 (IQR 18.3 to 45.3) in the surveillance group in the CAESAR trial; 20 plus or minus 12 months (range 0 to 41 months) in the PIVOTAL trial; and up to 12 years (range 8 to 12 years, mean 10 years) in the UKSAT trial.

Excluded studies

The trial that did not fulfil the criteria for consideration was the Canadian Trial, which ended early because of inadequate recruitment and was not sufficiently complete for inclusion in this review (Cole CW, personal communication, 1998). See Characteristics of excluded studies.

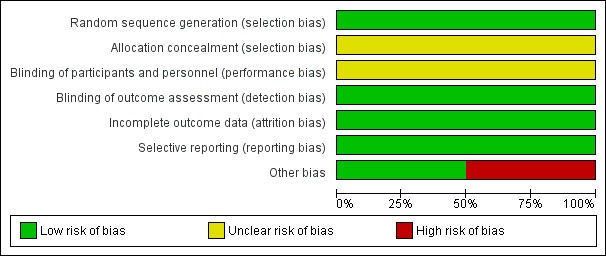

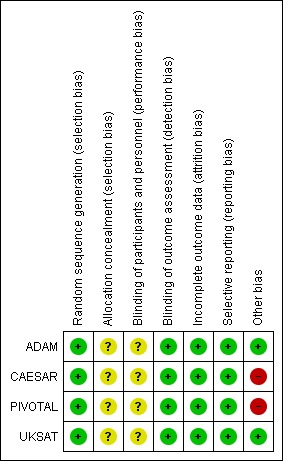

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 2 and Figure 3 for the 'Risk of bias' summary.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

The methods of randomisation of the included studies ensured good balance across study groups. Adherence to assigned treatment was high, with the lowest adherence rate across the four trials at 92.6% (ADAM; CAESAR; PIVOTAL; UKSAT). Risk of allocation bias was very low.

Blinding

The nature of the interventions did not permit the blinding of participants or observers, so we judged each included trial as being at an unclear risk of performance and detection bias (ADAM; CAESAR; PIVOTAL; UKSAT).

Incomplete outcome data

We ascertained mortality status in 100% (ADAM; PIVOTAL; UKSAT) and 98% (CAESAR) of participants. Moreover, the included studies experienced low loss to follow‐up rates. Risk of attrition bias was very low.

Selective reporting

All included studies published findings on the primary outcome measures of this review and reported on the outcomes pre‐planned in their protocols (ADAM; CAESAR; PIVOTAL; UKSAT). Risk of selective reporting bias was very low.

Other potential sources of bias

The CAESAR trial was originally funded by Cook Medical. In December 2006, during the enrolment phase of the trial, Cook Medical withdrew sponsorship, and the trial continued as full spontaneous research. According to the CAESAR study team, the design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of reports regarding the trial were at all times conducted independently from the sponsor. However, we could not exclude a possible conflict of interest in the CAESAR trial given that the sponsor of the study, Cook Medical, withdrew. The PIVOTAL trial was sponsored by Medtronic Vascular, who hold the PIVOTAL trial study database. Two members of the PIVOTAL research team who received funding from and were consultants for Medtronic declared conflicts of interest; a third member of the PIVOTAL research team had previously been a consultant for Medtronic. The Vascular Surgery Academic Co‐ordinating Center of the Cleveland Clinic was independently responsible for the conduct of the study and its analysis. Other potential sources of bias for the remaining trials included in this review were not identified and are therefore unclear.

Effects of interventions

In both the UKSAT and ADAM studies, the 30‐day operative mortality in the immediate‐surgery group (5.5% UKSAT and 2.1% ADAM) led to an early mortality disadvantage in this study group. The lower 30‐day operative mortality rate observed in the ADAM trial was expected due to the more restrictive study inclusion and exclusion criteria of the trial and better lung and renal function of the participants.

In the UKSAT study, the long‐term mortality (follow‐up range: 8 to 12 years, mean 10 years) was 63.9% in the immediate‐surgery group and 67.3% in the surveillance group. The UKSAT investigators found no statistically significant difference in long‐term survival between the immediate‐surgery and surveillance groups (adjusted HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.02). However, the hazards were nonproportional among study groups, as revealed by the survival curves crossing at approximately the three‐year mark; the risk associated with operative mortality in the immediate repair group resulted in an initial survival disadvantage for this study group compared to the selective‐surveillance group. The estimated adjusted HRs were in the direction of greater benefit of immediate surgery for younger patients and those with larger aneurysms, but none of the tests for interaction was statistically significant.

At the end of the ADAM trial follow‐up (range 3.5 to 8.0 years, mean 4.9 years), the observed mortalities in the immediate repair and the selective‐surveillance groups were 25.1% and 21.5%, respectively. However, as in the UKSAT study, the long‐term survival was not statistically significantly different between study groups (adjusted HR 1.21, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.54). The authors did not report violation of the proportional hazard assumption. Study results showed a possible modification of effect with age and AAA size but, as in the UKSAT study, none of the tests for interaction was significant. However, the analysis of the pooled participant‐level data from the ADAM and UKSAT trials demonstrated no significant difference in survival between immediate open repair and surveillance, regardless of patient age or aneurysm diameter (Filardo 2013; Filardo 2014).

In the CAESAR and PIVOTAL trials, the 30‐day operative mortality in the immediate‐surgery group (0.6% CAESAR and 0.3% PIVOTAL) led to an early disadvantage in terms of survival in this study group. The lower 30‐day mortality rate observed in the CAESAR and PIVOTAL studies, compared to the UKSAT and ADAM trials, was expected, due to the use of endovascular repair.

At the end of the CAESAR trial follow‐up (maximum: 54 months, median: 32.4 months), the estimated all‐cause mortalities for the immediate‐surgery group and the selective‐surveillance groups were 14.5% and 10.1%, respectively. However, long‐term survival was not statistically different between study groups (HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.93; P = 0.6). The authors did not report a violation of the proportional hazard assumption.

At the end of the PIVOTAL trial follow‐up (range 0 to 41 months, mean 20 plus or minus 12 months), the estimated all‐cause mortalities for the immediate‐surgery and selective‐surveillance groups were both 4.1%, and long‐term survival did not significantly differ between groups (HR 1.01, 95% CI 0.49 to 2.07; P = 0.98). The authors reported no evidence of nonproportional hazards between the two groups over time.

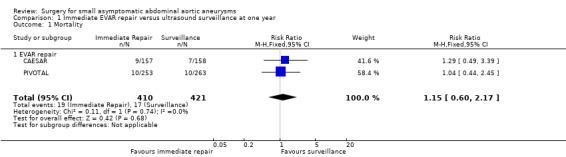

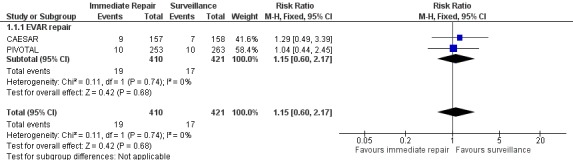

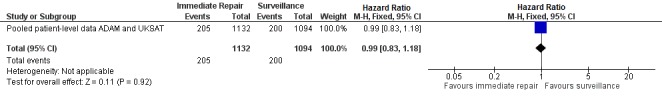

We performed meta‐analyses of mortality at one year to assess the effect of endovascular aneurysm repair (CAESAR and PIVOTAL only) and up to six years to assess the effect of open repair (ADAM and UKSAT). The meta‐analysis regarding the efficacy of immediate endovascular repair revealed a non‐significantly greater risk of mortality (RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.60 to 2.17; I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.1; Figure 4). Likewise, the analysis of pooled participant‐level data from the UKSAT and ADAM trials we conducted to assess mortality up to six years found no difference in survival between immediate open repair and surveillance (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.18; Chi2 test for interaction P = 0.92; Figure 5) (Filardo 2013; Filardo 2014). Additional analyses conducted using this pooled data set showed this lack of a statistically significant difference in survival persisted regardless of patient age (propensity‐adjusted P = 0.61) or AAA diameter (propensity‐adjusted P = 0.39) within the range of 4.0 cm to 5.5 cm (Filardo 2013; Filardo 2014).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Immediate EVAR repair versus ultrasound surveillance at one year, Outcome 1 Mortality.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: Immediate repair (either EVAR or open surgery) versus ultrasound surveillance at one year, outcome: 1.1 Mortality.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: Immediate repair (open surgery) versus ultrasound surveillance at six years.

In UKSAT, quality of life was assessed using the 20‐item Medical Outcomes Study short‐form. At randomisation, quality of life was similar in the two groups, but immediate‐surgery participants reported minor improvements in current health perceptions and less negative changes in bodily pain. In the ADAM trial, quality of life was assessed using the SF‐36. The immediate‐surgery and surveillance groups did not differ significantly for most SF‐36 scales at most of the time points measured, but the immediate‐surgery group scored significantly higher in general health (P < 0.01), particularly during the first two years following randomisation, and lower in vitality (P < 0.05). However, more participants became impotent after randomisation to immediate repair compared with surveillance (P < 0.03), but this difference did not become apparent until more than one year after randomisation. Maximum activity level did not differ significantly between the two randomised groups, but decline over time was significantly greater in the immediate repair group (P < 0.02). In the CAESAR trial, comparable quality of life (SF‐36) scores were seen in the immediate endovascular repair and surveillance groups at randomisation. At six months, the total SF‐36 and the physical and mental domain scores were all significantly higher with respect to baseline in the immediate‐repair group, while participants in the surveillance group scored lower. However, differences between the two groups diminished over time so that at the last assessment (one year or more after randomisation), there was no significant difference between immediate repair and surveillance (P = 0.25). The PIVOTAL trial compared quality of life between the immediate endovascular repair and surveillance groups in the 710 participants who completed the EQ‐5D instrument at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months. There were no statistically significant differences between the intervention groups at baseline on any of the EQ‐5D domains, and no treatment‐related differences were seen in either the quality‐of‐life domains or the utility score at 12 or 24 months follow‐up. Immediate endovascular repair participants did report significantly lower (P = 0.03) visual analog scale scores at 12 months, but this difference did not persist at 24 months.

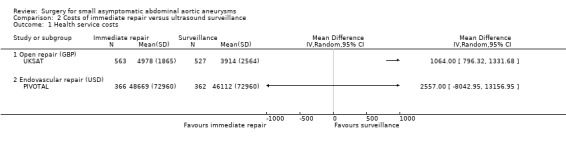

In UKSAT, the mean health service costs per participant over the 4 to 6 years follow‐up period postrandomisation were higher in the surgery than the surveillance group (GBP4978 versus GBP3914; difference GBP1064, 95% CI GBP796 to GBP1332). This estimate accounted for semi‐annual surveillance visits, aneurysm repair, and any associated follow‐up. For example, if surveillance was conducted only once per annum, the mean cost difference in favour of surveillance widened to GBP1256 (95% CI GBP990 to GBP1522). A 25% increase in cost of aneurysm repair further increased the difference, to GBP1636 (95% CI GBP1340 to GBP1932). The PIVOTAL trial reported significantly greater total medical costs (including AAA‐related office visits and imaging studies, AAA repair (endovascular device or open surgery), and other inpatient care (including secondary procedures, emergency department visits, other hospitalisations, and rehabilitation and skilled nursing facility care) in the immediate endovascular repair group at 6 months (USD33,471 versus USD5520; difference USD27,951, 95% CI USD25,156 to USD30,746), but greater total medical costs in the surveillance group in months 7 to 48 (USD40,592 versus USD15,197; difference USD25,395, 95% CI USD15,184 to USD35,605). These differences balanced out across the full 48 months studied such that there was no significant difference in total medical costs between the two interventions (USD48,669 in immediate endovascular repair versus USD46,112 in surveillance; difference USD2557, 95% CI ‐USD8043 to USD13,156). No cost data were available for the remaining two trials (ADAM; CAESAR).

Discussion

The results from the four trials to date suggest no overall advantage to immediate repair for small AAA (ADAM; CAESAR; PIVOTAL; UKSAT). Furthermore, the more recent trials focused on the efficacy of endovascular repair and still failed to show benefit (CAESAR; PIVOTAL), and analysis of the pooled participant‐level data from the earlier open‐repair trials showed that the lack of any treatment‐related survival benefit was consistent across all participant ages and aneurysm diameters within the small AAA range (Filardo 2013; Filardo 2014). Thus, the currently available evidence supports neither immediate open nor immediate endovascular repair of small AAAs. Our results affirm the Society for Vascular Surgery's strong recommendation in favour of surveillance for people with a fusiform AAA of 4.0 cm to 5.4 cm (Chaikof 2009). While the development of endovascular technology offers a significantly reduced operative mortality compared to open surgery and better short‐term survival in general (Lederle 2009; Prinssen 2004; United Kingdom EVAR Trial Investigators 2010), its efficacy is limited by high rates of re‐operation for complications unique to endovascular repair over longer follow‐up, including stent migration, stent wire fracture, metal fatigue, graft insertion site problems, and endoleak (Becquemin 2011; De Bruin 2010; EVAR Trial Participants 2005; Wilt 2006). For small AAA in particular, immediate endovascular repair does not appear to be superior to surveillance (see Figure 4, which shows a non‐significant benefit in favour of surveillance), and its use could expose patients to unnecessary risk and ultimately higher healthcare costs (Ballard 2012). Likewise, Figure 5 shows that immediate open repair offers no superior outcomes compared to surveillance for people with small AAAs.

However, it should be kept in mind that the results presented here all derive from randomised controlled trial settings which, particularly for the surveillance group, may not reflect current practice in terms of either the resources available for care or the patient compliance with follow‐up schedules that can be expected. Thus, while we can conclude that there is no significance difference in efficacy between immediate repair and surveillance in small AAAs, the question regarding effectiveness requires further investigation, particularly for small AAAs approaching the 5.5 cm cut‐off, where a recent meta‐analysis suggests an eight‐month surveillance interval is needed to adequately manage the risk of expansion past 5.5 cm (Bown 2013), and poor compliance with surveillance could tip the balance on patients' risks towards greater benefit with immediate repair. As there is currently no registry containing surveillance data for small AAAs, a large, prospective, population‐based comparative effectiveness study is needed (Ballard 2012).

Future research should include investigating the possible differences in quality of life between the various management strategies available for small AAA, taking into account that these might differ by age, and the evidence that moderate exercise (rather than the strict limitation on physical activity previously advised for people with unrepaired small AAA) benefits patients under surveillance (Myers 2010; Tew 2012). Additionally, the risks of rupture and those associated with repair need to be elucidated in women. There is some evidence that these risks differ in men and women with AAA (Abedi 2009; Lo 2013; McPhee 2007; Mehta 2012; UKSAT), but studies to date have generally included very few women, and, in the absence of sufficient data to rigorously examine the competing risks and the timing of intervention in women (Rudarakanchana 2013), recommendations for management in women remain a 'best guess' guided largely by the evidence available for men.

Establishing optimal treatment guidelines for people with small AAAs becomes even more relevant to improving public health and patient outcomes when the likelihood of increased AAA screening in the future is taken into account. The evidence from three randomised population screening trials, summarised in a Cochrane review, shows the benefits of screening older men for AAA (Cosford 2007). A national screening programme for all men aged 65 years and older has started in the United Kingdom (UK Screening), and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends AAA screening for men aged 65 to 75 years who have ever smoked (U.S. Preventive Task Force). The Society for Vascular Surgery has also recommended screening of all men aged 60 to 85 years for AAA; women aged 60 to 85 years with cardiovascular risk factors; and men and women aged 50 years and older with a family history of AAA (Kent 2004). These recommendations are based on evidence that screening for AAA and repair of large AAAs (5.5 cm or more in diameter) leads to decreased AAA‐specific mortality. However, the USPSTF also indicates that there is possible evidence of harms of screening and immediate treatment, including an increased number of surgeries with associated clinically significant morbidity and mortality and short‐term psychological harms (U.S. Preventive Task Force). These harms are of most concern for people with aneurysms in the 4.0 cm to 5.5 cm AAA size range, for whom current treatment guidelines are ambiguous.

Summary of main results

Findings from this review indicate that there was no survival advantage with immediate repair compared to selective surveillance in people with asymptomatic aneurysms sized 4.0 cm to 5.5 cm in diameter. Results from the UKSAT, ADAM, CAESAR, and PIVOTAL trials showed no significant differences in survival between the study treatment groups; the analysis of the pooled participant‐level data from the ADAM and UKSAT studies showed that this held true regardless of participant age or AAA diameter for open repair (Filardo 2013; Filardo 2014). In the absence of long‐term, participant‐level data for the PIVOTAL and CAESAR trials, we cannot draw firm conclusions about the long‐term effects of immediate endovascular repair. However, findings to date suggest no advantage to immediate surgery for small AAA, and the currently available evidence supports neither immediate open nor immediate endovascular repair of small AAAs. The Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines strongly recommend surveillance for people with a fusiform AAA of 4.0 cm to 5.4 cm (Chaikof 2009).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This review was based on all trials to date that were suitable for inclusion. However, one limitation of the present review is the low proportion of women and non‐white races in the trials. The gender imbalance is exacerbated by the late onset of the disease in women and by the approximately three times higher prevalence of AAA in men than in women, and the black race has been identified as having a strong negative association with AAA (Lederle 1997; Lederle 2000). Thus, while it is indisputable that the study results might be difficult to generalise to women and non‐white men, this review provides critical data that can benefit the population with the highest prevalence of AAA and, therefore, the vast majority of people with AAA. Future research regarding the management of small AAA should focus on minorities and women, as data regarding these populations are lacking. In particular, future research should assess whether the AAA‐management recommendations, which are based on studies in which women are underrepresented, are applicable to women given their smaller body frames and, therefore, smaller abdominal aortas. This is critical given the evidence that risk of rupture, risks associated with repair, and progression of disease may differ between men and women (Abedi 2009; Brown 2003; Lo 2013; McPhee 2007; Mehta 2012; RESCAN Collaborators 2013; UKSAT).

Quality of the evidence

The UKSAT, ADAM, CAESAR, and PIVOTAL trials were very similar in design and, more importantly, were all well‐conducted studies. All relevant studies were identified and included in this review. Moreover, all relevant data were obtained. In summary, besides the possible bias deriving from the conflicts of interest regarding the CAESAR and PIVOTAL trials, the quality of evidence summarised in this review is high.

Potential biases in the review process

Three members of the research team (GF, MAMM, BdG) independently abstracted the data, which were cross‐checked by other team members (DJB and JTP). To further reduce bias, the role of JTP (trialist in the UKSAT study and author in the present review) in abstracting the data was limited to cross‐checking the information abstracted.

Strengths of the present review regarding potential biases are: 1) all relevant studies were identified and included in the review; 2) all the studies included in the review had very similar designs and methods; 3) relevant data for all studies were obtained; and 4) all the studies included in the review shared the same main primary outcome, and this outcome is the outcome of interest for this review too. However as reported, we cannot exclude possible bias deriving from the conflicts of interest identified in the CAESAR and PIVOTAL trials.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

To our knowledge, this is the only systematic review published to date on this topic.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The current evidence supports delaying the timing of AAA repair until the aneurysm reaches 5.5 cm in diameter. Findings from the four trials to date suggest no advantage to immediate repair of small AAAs, irrespective of whether open or endovascular repair is used. The results of the analysis of the pooled participant‐level data ADAM and UKSAT trials show that for open repair, this remains consistent, regardless of participant age or AAA diameter. Unfortunately, long‐term data from the two trials investigating endovascular repair are not available, so we can only draw firm conclusions regarding outcomes after the first few years for open repair.

Implications for research.

Future research needs to move away from the “procedure as a solution” focus that has dominated AAA research and management to date and focus on what remains unknown about the disease itself. Large, prospective, population‐based studies are needed to investigate disease progression in relation to AAA morphology (including shape, size, location, volume, and ratio of healthy aorta to the aneurysm). An early focus of this work should be to determine whether AAA volume is superior to diameter as a measure of disease progression. Another important question is whether efficacy or effectiveness of the various treatment options (open repair, endovascular repair, and the emerging medical management options) differs based on AAA morphology. Finally, research regarding the risks related to and management of small AAAs in minorities and women is urgently needed, as data regarding these populations are lacking. In particular, future research should assess whether the AAA management recommendations, which are based on studies in which women are underrepresented, are applicable to women given their smaller body frames and, therefore, smaller abdominal aortas.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 26 June 2014 | New search has been performed | Searches re‐run. No new studies included. |

| 26 June 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Searches re‐run. No new studies included. Relevant review sections updated according to current Cochrane standards. Conclusions not changed. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 1999 Review first published: Issue 4, 1999

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 17 October 2011 | New search has been performed | New author added |

| 17 October 2011 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | CAESAR and PIVOTAL results included in the analysis |

| 20 May 2008 | New search has been performed | ADAM trial results incorporated in analysis. CAESAR and PIVOTAL trials added to ongoing studies. |

| 8 April 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

The review authors thank Briget da Graca for abstracting data from the two most recent publications included in this review, as well as for background research and writing in preparing this manuscript, and Gerry Fowkes for his contribution to previous versions of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

| #1 | MeSH descriptor: [Endovascular Procedures] explode all trees | 6017 |

| #2 | MeSH descriptor: [Stents] explode all trees | 3314 |

| #3 | MeSH descriptor: [Vascular Surgical Procedures] this term only | 652 |

| #4 | MeSH descriptor: [Blood Vessel Prosthesis] explode all trees | 452 |

| #5 | MeSH descriptor: [Blood Vessel Prosthesis Implantation] this term only | 508 |

| #6 | endovasc*:ti,ab,kw | 941 |

| #7 | endostent*:ti,ab,kw | 1 |

| #8 | (stent* or graft* or endograft*):ti,ab,kw | 18089 |

| #9 | (surger* or surgic* or repair):ti,ab,kw | 88118 |

| #10 | (EVAR):ti,ab,kw | 74 |

| #11 | RAAA:ti,ab,kw | 5 |

| #12 | (EVRAR):ti,ab,kw | 1 |

| #13 | endoprosthe*:ti,ab,kw | 203 |

| #14 | Palmaz:ti,ab,kw | 91 |

| #15 | Zenith or Dynalink or Hemobahn or Luminex* or Memotherm or Wallstent:ti,ab,kw | 128 |

| #16 | Viabahn or Nitinol or Hemobahn or Intracoil or Tantalum:ti,ab,kw | 155 |

| #17 | MeSH descriptor: [Ultrasonography, Doppler] explode all trees | 2391 |

| #18 | MeSH descriptor: [Ultrasonography] this term only | 816 |

| #19 | MeSH descriptor: [Tomography] explode all trees | 10690 |

| #20 | screen* or ultrasound or scan* or surveillance | 61201 |

| #21 | #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 | 162640 |

| #22 | MeSH descriptor: [Aortic Aneurysm] explode all trees | 767 |

| #23 | aneurysm* near/4 (abdom* or thoracoabdom* or thoraco‐abdom* or aort*) | 1154 |

| #24 | (aort* near/3 (ballon* or dilat* or bulg*)) | 69 |

| #25 | AAA | 453 |

| #26 | MeSH descriptor: [Aorta, Abdominal] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Surgery ‐ SU] | 179 |

| #27 | #22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 | 1458 |

| #28 | #21 and #27 in Trials | 836 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Immediate EVAR repair versus ultrasound surveillance at one year.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mortality | 2 | 831 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.60, 2.17] |

| 1.1 EVAR repair | 2 | 831 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.60, 2.17] |

Comparison 2. Costs of immediate repair versus ultrasound surveillance.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Health service costs | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Open repair (GBP) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Endovascular repair (USD) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Costs of immediate repair versus ultrasound surveillance, Outcome 1 Health service costs.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

ADAM.

| Methods | Study design: intention to treat Method of randomisation: equal probability of assignment to each of the two study groups using automated telephone/computer Concealment of allocation: unblinded | |

| Participants | Country: United States Number: 1136 Age: 50 to 79 years Sex: men (n = 1126) and women (n = 10) Inclusion criteria: small (4.0 cm to 5.5 cm) non‐tender asymptomatic AAAs considered fit for immediate surgery. Patients who were considered unfit for immediate surgery, had symptoms associated the aneurysm, were unable to attend the follow‐up visit, or were unable to give informed consent were excluded. Patients who received a revascularization procedure within 3 months of enrolment, who had a myocardial infarction within 6 months of enrolment, or who were expected to survive less than 5 years because of invasive cancer or other life‐threatening disease were also excluded. | |

| Interventions | Treatment: surgery, n = 569 of whom 527 had immediate aneurysm repair; 42 had no elective operation due to death, refusal, etc. Surveillance, n = 567 of whom 349 had aneurysm repair when they met the criteria listed below (in 9%, the procedures were performed despite an AAA that did not meet the repair criteria listed below). Participants assigned to the immediate‐surgery group received standard open repair within 6 weeks after randomisation, while participants assigned to selective surveillance were followed without repair at similar regular intervals (at minimum once every 6 months), and surgery was performed within 6 weeks if: a) the aneurysm reached 5.5 cm; or b) the aneurysm enlarged by a minimum of 0.7 cm in 6 months or 1.0 cm in 1 year; or c) the aneurysm became symptomatic. | |

| Outcomes | Primary: survival during mean follow‐up (range 3.5 to 8.0 years, mean 4.9 years) (30‐day surgical mortality) Secondary: healthcare costs | |

| Notes | Supported by the Cooperative Studies Program of the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development, Washington, DC, USA | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | The method of randomisation was of equal probability of assignment to each of the two study groups using automated telephone/computer. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Concealment of allocation: unblinded |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Cannot blind participants |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Unlikely given the study outcome (mortality) and low lost‐to‐follow‐up rate. Vital status was assessed using the same methodology for both participants in the immediate‐repair group and participants in the routine ultrasound surveillance group‐‐in case misclassification occurred this would have been non‐differential and its impact on the study results would be limited. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Unlikely given the study outcome (mortality) and low lost‐to‐follow‐up rate |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Authors published findings on all the study outcomes including the study outcome of this review. |

| Other bias | Low risk | We did not identify other possible risk of bias. |

CAESAR.

| Methods | Study design: intention to treat Method of randomisation: Randomisation was designed with equal probability (1:1 ratio) of assignment to either immediate endovascular repair or surveillance by means of a computed‐generated random number list, stratified by centre using a permuted block design and carried out online through the Internet. Concealment of allocation: unblinded |

|

| Participants | Country: Italy Number: 360 Sex: men (n = 345) and women (n = 15) Age: 50 to 79 years Inclusion criteria: people with small (4.1 cm to 5.4 cm) asymptomatic AAAs, without high surgical risk, and who would have benefited from immediate repair. Patients were excluded if they had severe co‐morbidities or a suprarenal/thoracic aorta ≥ 4.0 cm, needed urgent repair, or were unable or unwilling to give informed consent or follow the protocol. |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: surgery, n = 182 of whom 175 had immediate endovascular surgery; 6 declined treatment and 1 underwent open repair according to person's choice. Surveillance, n = 178 of whom 172 had aneurysm repair when they met the criteria below (6 patients had endovascular repair against protocol: 5 per patient choice and 1 with a surgeon not participating in the study). Participants assigned to immediate endovascular repair underwent aneurysm repair a median of 22 days after randomisation, while participants assigned to surveillance were seen every 6 months and repair allowed if the aneurysm grew to 5.5 cm diameter in size, rapidly increased in diameter (> 1 cm/year), or became symptomatic. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary: mortality from any cause Secondary: 1) aneurysm‐related deaths (defined as death caused directly or indirectly by aneurysm rupture or aneurysm repair), 2) aneurysm rupture, 3) perioperative (30 days or inpatient) or late adverse events (defined according to SVS/AAVS reporting standards), 4) conversion to open repair, 5) loss of treatment options (anatomical suitability for endovascular repair), and 6) aneurysm growth rate |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation was designed with equal probability (1:1 ratio) of assignment to either immediate endovascular repair or surveillance by means of a computed‐generated random number list, stratified by centre using a permuted block design and carried out online through the Internet. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Concealment of allocation: unblinded |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Cannot blind participants |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Unlikely given the study outcome (mortality) and low lost‐to‐follow‐up rate. Vital status was assessed using the same methodology for both participants in the immediate‐repair group and participants in the routine ultrasound surveillance group‐–in case misclassification occurred this would have been non‐differential and its impact on the study results would be limited. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Unlikely given the study outcome (mortality) and low lost‐to‐follow‐up rate |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Authors published findings on the main study outcome of this review. |

| Other bias | High risk | Conflicts of interest: The sponsor of the study, Cook Medical, withdrew. |

PIVOTAL.

| Methods | Study design: intention to treat Method of randomisation: The randomisation procedure was created with equal probability of assignment to each of the treatment groups by means of a computer‐generated random‐number code. Concealment of allocation: unblinded |

|

| Participants | Country: United States Number: 728 Sex: men (n = 631) and women (n = 97) Age: 40 to 90 years Inclusion criteria: people with small (4.0 cm to 5.0 cm) AAAs. Patients were excluded from the study if they had evidence of symptoms referable to the aneurysm, an abdominal or thoracic repair, an aneurysm originating ≤ 1.0 cm from the most distal main renal artery, life expectancy of < 3 years, inability to provide informed consent, predicted noncompliance with the protocol, SVS score > 2 with the exception of age and controlled hypertension, baseline serum creatinine level > 2.5 mg/dL, or when the patient did not meet the indications for use of the endograft device. |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: surgery, n = 366 of whom 322 had immediate endovascular surgery; 4 underwent open surgery, 6 underwent repair outside of the 30‐day window of randomisation, 9 were withdrawn per patient request, 10 were withdrawn per physician request for deteriorating health status between randomisation and scheduled repair, 2 were treated with an endograft device that was not in the protocol, and 13 received no repair for reasons not specified. Surveillance, n = 362 of whom 100 had aneurysm repair when they met the criteria listed below. Participants assigned to immediate endovascular repair underwent aneurysm repair ≤ 30 days of randomisation, while participants assigned to surveillance were seen at 1 month, 6 months, and every 6 months thereafter for a minimum of 36 months and a maximum of 60 months after operation. Participants were offered aneurysm repair when symptoms thought referable to the aneurysm developed, when the diameter of the aneurysm reached 5.5 cm, or when the aneurysm enlarged ≥ 0.5 cm between any 2 6‐month assessments. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary: to determine whether immediate endovascular repair of aneurysms 4.0 cm to 5.0 cm in diameter is superior to surveillance with respect to the frequency of rupture or aneurysm‐related death. Secondary: N/A |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | The randomisation procedure was designed to provide equal probability of assignment to each of the treatment groups by means of a computer‐generated random‐number code. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Concealment of allocation: unblinded |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Cannot blind participants |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Unlikely given the study outcome (mortality) and low lost‐to‐follow‐up rate. Vital status was assessed using the same methodology for both participants in the immediate‐repair group and participants in the routine ultrasound surveillance group‐‐in case misclassification occurred, this would have been non‐differential and its impact on the study results would be limited. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Unlikely given the study outcome (mortality) and low lost‐to‐follow‐up rate |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Authors published findings on the main study outcome of this review. |

| Other bias | High risk | Conflicts of interest: The study was funded by Medtronic Vascular, which now holds the trial database. The funding source was not specified in the report of trial results, but was specified in the 2009 paper describing the rationale and protocol for the study (PIVOTAL). In addition, two members of the research team were acknowledged as paid consultants of Medtronic. |

UKSAT.

| Methods | Study design: intention to treat Method of randomisation: concealed randomisation using automated telephone/computer Concealment of allocation: unblinded | |

| Participants | Country: United Kingdom Number: 1090 Sex: men (n = 902) and women (n = 188) Age: 60 to 76 years Inclusion criteria: asymptomatic (non‐tender) infrarenal aneurysm. Maximum anteroposterior diameter 4.0 cm to 5.5 cm. Fit for elective surgery. | |

| Interventions | Treatment: surgery, n = 563 of whom 528 had immediate aneurysm repair; 35 had no elective operation due to death, refusal, etc. Control: surveillance, n = 527 of whom 401 had aneurysm repair when they met the criteria listed below. Participants assigned to the immediate‐surgery group received standard open repair within 6 weeks after randomisation, while participants assigned to selective surveillance were followed without repair at similar regular intervals (at minimum once every 6 months), and surgery was performed within 6 weeks if: a) the aneurysm reached 5.5 cm; or b) the aneurysm enlarged by a minimum 1.0 cm in 1 year; or c) the aneurysm became tender or symptomatic. | |

| Outcomes | Primary: survival during mean follow‐up (range 8 to 12 years, mean 10 years) (30‐day surgical mortality) Secondary: healthcare costs | |

| Notes | The Medical Research Council and the British Heart Foundation supported this trial. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Concealed randomisation using automated telephone/computer |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Concealment of allocation: unblinded |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Cannot blind participants |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Unlikely given the study outcome (mortality) and low lost‐to‐follow‐up rate. Vital status was assessed using the same methodology for both participants in the immediate‐repair group and participants in the routine ultrasound surveillance group‐‐in case misclassification occurred, this would have been non‐differential and its impact on the study results would be limited. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Unlikely given the study outcome (mortality) and low lost‐to‐follow‐up rate |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Authors published findings on all the study outcomes including the study outcome of this review. |

| Other bias | Low risk | We did not identify other possible risk of bias. |

AAVS: American Association for Vascular Surgery SVS: The Society for Vascular Surgery

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Canadian Trial | This trial was begun but stopped because of an inadequate rate of recruitment after n = 104 had been enrolled (Cole CW, personal communication, 1998). |

Differences between protocol and review

We did not report the overall effect for the 30‐day mortality in this review. Inherent within the comparison between immediate repair and surveillance with selective repair is the fact that early mortality is always lower in the surveillance group; participants in the immediate‐repair group underwent a surgery that carries at least some risk of operative mortality (how great a risk depending on whether open or endovascular surgery was used) almost immediately after enrolment, while patients in the surveillance group were simply monitored. As such, 30‐day mortality is not a measure of interest. However, since the 30‐day mortality effects differed between the included studies, we did report these effects for each individual study in the descriptions of the included studies.

A second difference between this update of the review and the original protocol was the use of hazard ratios to describe one‐ and six‐year survival for the ADAM and UKSAT. We based this decision on the fact that, when we conducted this review, we had the participant‐level data for these two studies and were able to pool these data to estimate the hazard ratios. Since we only had tabular data for the CAESAR and PIVOTAL trials, we could not estimate a hazard ratio for the one‐year survival comparison between immediate endovascular repair and surveillance. As such, we estimated a risk ratio in this case.

For this update the term 'immediate' has replaced 'early' throughout the text, to be consistent with the trials' definition.

Contributions of authors

All review authors identified trials and agreed on their inclusion or exclusion, adequacy of randomisation, attainment of adequate sample size, and completeness of follow‐up. For this update, two members of the research team (GF and BdG) abstracted the data, which were cross‐checked by the remaining review authors.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

-

The Chief Scientist Office, Scottish Government Health Directorates, the Scottish Government, UK.

The PVD Group editorial base is supported by the Chief Scientist Office.

-

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), UK.

The PVD Group editorial base is supported by a programme grant from the NIHR.

Declarations of interest

JTP was a co‐investigator in the UKSAT study and DJB was a co‐investigator of the ADAM trial. GF: none known JTP: none known MAMM: none known DJB: none known

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

ADAM {published data only}

- Filardo G, Lederle FA, Ballard DJ, Hamilton C, Graca B, Herrin J, et al. Effect of age on survival between open repair and surveillance for small abdominal aortic aneurysms. American Journal of Cardiology 2014;114(8):1281‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo G, Lederle FA, Ballard DJ, Hamilton C, Graca B, Herrin J, et al. Immediate open repair vs surveillance in patients with small abdominal aortic aneurysms: survival differences by aneurysm size. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2013;88(9):910‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, Acher CW, Ballard DJ, Littooy FN, et al. Quality of life, impotence, and activity level in a randomized trial of immediate repair versus surveillance of small abdominal aortic aneurysm. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2003;38(4):745‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, Chute EP, Hye RJ, Makaroun MS, et al. Aneurysm Detection and Management Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Investigators. The aneurysm detection and management study screening programme: validation cohort and final results.. Archives of Internal Medicine 2000;160(10):1425‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, Chute EP, Littooy FN, Bandyk D, et al. Aneurysm Detection and Management (ADAM) Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group. Prevalence and associations of abdominal aortic aneurysm detected through screening.. Annals of Internal Medicine 1997;126(6):441‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, Gordon IL, Chute EP, Littooy FN, et al. The Aneurysm Detection and Management (ADAM) Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Investigators. Relationship of age, gender, race, and body size to infrarenal aortic diameter.. Journal of Vascular Surgery 1997;26(4):595‐601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederle FA, Wilson SE, Johnson GR, Littooy FN, Acher C, Messina LM, et al. Design of the abdominal aortic Aneurysm Detection and Management Study. Journal of Vascular Surgery 1994;20(2):296‐303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederle FA, Wilson SE, Johnson GR, Reinke DB, Littooy FN, Acher CW, et al. Immediate repair compared with surveillance of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. New England Journal of Medicine 2002;346(19):1437‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

CAESAR {published data only}

- Cao P, Rango P, Verzini F, Parlani G, Romano L, Cieri E, for the CAESAR Trial Group. Comparison of Surveillance Versus Aortic Endografting for Small Aneurysm Repair (CAESAR): Results from a randomised trial. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 2011;41(1):13‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao P, CAESAR Trial Collaborators. Comparison of Surveillance vs Aortic Endografting for Small Aneurysm Repair (CAESAR) trial: study design and progress. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 2005;30(3):245‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rango P, Verzini F, Parlani G, Cieri E, Romano L, Loschi D, et al. Quality of life in patients with small abdominal aortic aneurysm: the effect of early endovascular repair versus surveillance in the CAESAR trial. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 2011;41(3):324‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCT00118573. Comparison of Surveillance Versus Aortic Endografting for Small Aneurysm Repair. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct/show/NCT00118573?order=1 (accessed 14 November 2011). [DOI] [PubMed]

PIVOTAL {published data only}

- Eisenstein EL, Davidson‐Ray L, Edwards R, Anstrom KJ, Ouriel K. Economic analysis of endovascular repair versus surveillance for patients with small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2013;58(2):302‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCT00444821. The (PIVOTAL) study. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct/show/NCT00444821?order=1 (accessed 8 April 2014).

- Ouriel K. The PIVOTAL study: a randomized comparison of endovascular repair versus surveillance in patients with smaller abdominal aortic aneurysms. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2009;49(1):266‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouriel K, Clair DG, Kent CK, Zarins CK, PIVOTAL investigators. Endovascular repair compared with surveillance for patients with small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2009; Vol. 50, issue 2:449. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ouriel K, Clair DG, Kent KC, Zarins CK, for the Positive Impact of Endovascular Options for treating Aneurysms Early (PIVOTAL) Investigators. Endovascular repair compared with surveillance for patients with small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2010;51(5):1081‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

UKSAT {published data only}

- Brown LC, Thompson SG, Greenhalgh RM, Powell JT, UK Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Fit patients with small abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) do not benefit from early intervention. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2008;48(6):1375‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo G, Lederle FA, Ballard DJ, Hamilton C, Graca B, Herrin J, et al. Effect of age on survival between open repair and surveillance for small abdominal aortic aneurysms. American Journal of Cardiology 2014;1148(8):1281‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo G, Lederle FA, Ballard DJ, Hamilton C, Graca B, Herrin J, et al. Immediate open repair vs surveillance in patients with small abdominal aortic aneurysms: survival differences by aneurysm size. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2013;88(9):910‐19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The UK Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Final 12‐year follow‐up of surgery versus surveillance in the UK Small Aneurysm Trial. British Journal of Surgery 2007;94(6):702‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The UK Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Health service costs and quality of life for early elective surgery or ultrasonographic surveillance for small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Lancet 1998;352(9141):1656‐60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The UK Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Mortality results for randomised controlled trial of early elective surgery or ultrasonographic surveillance for small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Lancet 1998;352(9141):1649‐55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The UK Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. The UK Small Aneurysm Trial: design, methods and progress. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 1995;9(1):42‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The United Kingdom Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Long‐term outcomes of immediate repair compared with surveillance of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. New England Journal of Medicine 2002;346(19):1445‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Canadian Trial {unpublished data only}

- Cole CW. [personal communication]. Conversation with review authors Dr Ballard and Prof Powell 1998.

Additional references

Abedi 2009

- Abedi NN, Davenport DL, Xenos E, Sorial E, Minion DJ, Endean ED. Gender and 30‐day outcome in patients undergoing endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR): an analysis using the ACS NSQIP dataset. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2009;50(3):486‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ballard 1992

- Ballard DJ, Etchason JA, Hilborne LH, Campion ME, Kamberg CJ, Solomon DH, et al. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Surgery. A Literature Review and Ratings of Appropriateness and Necessity. Santa Monica (CA): RAND, 1992. [Google Scholar]

Ballard 2012

- Ballard DJ, Filardo G, Graca B, Powell JT. Clinical practice change requires more than comparative effectiveness evidence: abdominal aortic aneurysm management in the USA. Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research 2012;1(1):31‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Becquemin 2011

- Becquemin JP, Pillet JC, Lescalie F, Sapoval M, Goueffic Y, Lermusiaux P, et al. A randomized controlled trial of endovascular aneurysm repair versus open surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysms in low‐ to moderate‐risk patients. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2011;53(5):1167‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bernstein 1984

- Bernstein EF, Chan EL. Abdominal aortic aneurysm in high‐risk patients. Outcome of selective management based on size and expansion rate. Annals of Surgery 1984;200(3):255‐63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bown 2013

- Bown MJ, Sweeting MJ, Brown LC, Powell JT, Thompson SG. Surveillance intervals for small abdominal aortic aneurysms: a meta‐analysis. JAMA 2013;309(8):806‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brown 2003

- Brown PM, Zelt DT, Sobolev B. The risk of rupture in untreated aneurysms: the impact of size, gender, and expansion rate. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2003;37(2):280‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chaikof 2009

- Chaikof EL, Brewster DC, Dalman RL, Makaroun MS, Illig KA, Sicard GA, et al. The care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm: the Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2009;50(4 Suppl):S2‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cosford 2007

- Cosford PA, Leng GC, Thomas J. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002945.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

De Bruin 2010