Abstract

Background

The low uptake of HIV voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) has hindered global attempts to prevent new HIV infections and has limited scale‐up of HIV care and treatment. Globally, only 10% of HIV‐infected individuals are aware of their HIV status. One approach to increase uptake is home‐based HIV VCT, which may be effective in increasing the number of patients on treatment and preventing new infections.

Objectives

To establish the effect of home‐based HIV VCT on uptake of HIV testing

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE (February 2007), EMBASE (February 2007), CENTRAL (February 2007), AIDSearch (February 2007), LILACS, CINAHL and Sociofile. We also contacted relevant researchers. The original review search strategy was updated in 2008.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing home‐based HIV VCT with other testing models

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected studies, assessed methodological quality, and extracted data. We planned to conduct statistical analysis using the Review Manager software and calculate summary statistics (relative risks (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI)) for primary outcomes.

Main results

Only one study from developing countries met the inclusion criteria and was included in the review. The study, a cluster randomised trial (10 clusters, n=849) compared VCT uptake between an optional location (including home‐based) and a local clinic location in a population‐based HIV survey. The study showed a higher uptake of VCT among participants in the optional‐location group. Uptake was significantly greater in the optional‐location group in those who were pre‐test counselled only (RR=4.6; 95% CI 3.58 to 5.91); pretest counselled and tested (RR=4.6; 95% CI 3.51 to 5.92); and post‐test counselled and received the test result (RR=4.8; 95% CI 3.62 to 6.21). This study, however, had significant methodological problems limiting further analysis and interpretation.

Authors' conclusions

Although home‐based HIV VCT has the potential to enhance VCT uptake in developing countries, insufficient data exist to recommend large‐scale implementation of home‐based HIV testing. Further studies are needed to determine if home‐based VCT is better than facility‐based VCT in improving VCT uptake.

Plain language summary

Home‐based HIV voluntary counselling and testing

The HIV/AIDS epidemic remains a significant global health problem, especially in developing countries. The rate of uptake of voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) is low, and only about one in 10 eligible people have access to VCT in developing countries. Challenges of HIV testing include the difficulty of getting to testing sites and the cost of being tested. Researchers assumed that providing HIV testing or results or both in homes compared to in a healthcare facility would lead to higher uptake of HIV testing. This review attempted to evaluate this assumption. We found only one published study from developing countries and none from developed countries. The only study included in the review showed an increase in VCT uptake after home‐based VCT intervention. Because of the limited evidence to date, however, further research is needed to evaluate if home‐based VCT is better than facility‐based VCT or other testing methods.

Background

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a collection of signs and symptoms associated with life‐threatening immune deficiency, is caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a human retrovirus (Gallo 2003). Worldwide, about 33 million people are infected with HIV, with over 97% in low‐ and middle‐income countries and 67% in sub‐Saharan Africa alone (UNAIDS 2008). The virus is a major public health problem in developing countries. Early diagnosis and timely access to care can improve the course of the disease and potentially reduce the rate of transmission. The virus is diagnosed among both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals. Amongst asymptomatic people, HIV voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) is the first step to effective HIV/AIDS care and is a central point in HIV prevention in developing and developed countries (De Zoysa 1995, Kaiser 2005, Summers 2000). This intervention is vital in developing countries, particularly in remote areas where delivery of health services is fragmented and laboratory facilities are limited.

Voluntary counselling and testing consists of a pre‐test counselling session with a trained counsellor, an HIV antibody test, and a post‐test session in which an individual is given results and counselled on reducing HIV‐risk behaviours to ensure they remain uninfected (if tested negative) or avoid infecting others (if tested positive). People who test positive also are provided with emotional support, referred to treatment programs, and encouraged to disclose their status to their sexual partners. The target groups for VCT are usually those at high risk of HIV infection; but in countries with generalized epidemics, VCT is aimed at the entire population.

Different models of HIV testing include:

Mandatory HIV testing: This type of HIV testing is performed without obtaining consent from individuals. The testing was proposed to address HIV among specific populations; for example among pregnant women to prevent HIV transmission to their unborn children. This method of testing has been used in medical circumstances when a patient is unconscious, his or her parent or guardian is absent, or knowledge of the patient's HIV status is essential for optimal treatment. Likewise, testing without consent has been used for sexual offenders, prisoners, and military recruits. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and World Health Organization (WHO) recommend that such testing be conducted only when it is accompanied by counselling for both HIV‐positive and HIV‐negative people and when HIV‐infected persons can be referred to medical and psychosocial services (UNAIDS 2004). Where used, the benefits of mandatory testing do not outweigh potential harms when compared to VCT (Nakchbandi 1998). Mandatory testing is not ideal as a public health intervention due to human rights issues. It may cause people to avoid seeking healthcare or being tested and is unlikely to lead to behaviour change. As a result, UNAIDS does not support mandatory testing of individuals (UNAIDS 2004).

Voluntary counselling and testing (VCT): VCT is the recommended method of HIV testing and relies on individuals presenting themselves for testing and giving voluntary informed consent. Several models of VCT are available:

Free‐standing services: This model offers VCT at locations away from health services and provides frequent referral of patients to care and support services. It is associated with dedicated staff, flexible working hours, and strong community links. Staff burn‐out, however, may limit the availability of services, and HIV/AIDS stigma can restrict client attendance.

Integrated VCT: The service is usually incorporated into existing health settings such as sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics, tuberculosis (TB) clinics, family planning services, and mother and child health services. It offers ease of cross‐referral and is less costly to operate than free‐standing services. This model, however, may not reach certain groups, such as young people and men who normally are unwilling to go to health facilities. Equally, staff may not be committed to the program in the presence of competing interests.

Mobile or community outreaches: This model involves using a van or other mobile means to reach "hard‐to‐reach" populations. It can improve access, be anonymous, and link to other services, but it can be expensive. It requires considerable resources (equipment, staffing), makes it difficult to ensure follow‐up after post‐test counselling, and requires extensive community mobilization to guarantee service uptake.

Home‐based VCT: This is a door‐to‐door VCT service that occurs in people's homes (Figure 1 (TASO 2005); Figure 2 (TASO 2005)). Lay counsellors or community health workers conduct house visits to offer pre‐test counselling to the entire household, obtain consent from eligible members, test, and provide results and post‐test counselling. This service can be cost‐effective, address the needs of the entire family at once, make the discussion on prevention and behavioral change more effective, diminish perceived stigma, and facilitate counselling and disclosure among discordant couples. Alternately, this service is time consuming, family disclosure (parents to children) may be challenging because parents must deal with knowledge of their status first, and testing everyone at the same time may result in premature disclosure and adverse social outcomes.

1.

A housewife undergoing HIV testing in the comfort of her home (Gave permission to use photograph)

2.

TASO Jinja counsellor & tester performing HIV rapid test at home and taking a dry blood spot for quality control (Gave permission to use photograph)

Routine (or opt‐out) testing and counselling (RTC): Testing usually is provided with other tests during a patient's clinical visit, as part of routine medical care. Pre‐test counselling is offered in groups, with more emphasis on post‐test counselling. Patients refusing the test are considered to have opted out. This model has been implemented in several countries in prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission, TB, and STI clinics and in medical wards (Alcorn 2006). Recently, RTC has been recommended by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as one of the methods to increase rates of early diagnosis (CDC 2006). Although reduced start‐up cost is associated with RTC, it has been criticized for removing the "voluntariness" from HIV testing. Following the WHO recommendations (WHO 2007) for RTC in generalized epidemics where treatment is available, Uganda, for example, continues to implement RTC, starting first with a few research sites (CDC 2006) then including more healthcare facilities. From a public health perspective, the primary aim of RTC is to increase the number of people who know their HIV status and to get those who test positive into clinical care sooner (MOH‐Uganda 2005). In the context of increased access to treatment and care for HIV‐infected individuals, the main goal of RTC is to ensure access to clinical care earlier (Liechty 2004; MOH‐Uganda 2005), and the secondary goal is to prevent HIV transmission and acquisition (MOH‐Uganda 2005). Diagnostic counselling and testing: This method is initiated by a health worker as part of the diagnostic work‐up for patients presenting with symptoms or signs attributable to HIV‐related diseases. The service aims to assist rapid diagnosis and management. One example is HIV testing for all TB patients as part of their routine management.

VCT coverage and implementation of various models in resource‐limited settings: Voluntary counselling and testing is an effective prevention intervention in resource‐constrained countries (VCT Efficacy 2000); however, the rate of coverage remains low for many reasons (Prabhat 2002; Coovadia 2000). Worldwide, only one in 10 HIV‐positive individuals know their status, and the majority in developing countries do not have access to HIV VCT (Global Report 2007). In one study in Uganda, although 70% of people wanted to be tested, only 15% had been tested (Kamya 2007). Among the reasons for not testing were HIV‐related stigma, distance to testing sites (and associated transport costs), and returning to receive results for post‐test counselling when rapid testing was not performed (Morin 2006). A national study in Uganda also showed that among 70% of adults who wanted to receive testing only 6% had been tested (UBOS 2001). Similarly, nearly 50% of hospitalised patients in Uganda have HIV infection, but HIV testing is rarely available and never routinely offered to patients (Wanyenze 2004). Prior to wide availability of rapid testing, those tested in hospitals and other facilities were less likely to return for their results (Wolff 2005; Fylkesnes 1999). In Zimbabwe, inconvenience of testing location and testing hours were reported as the main reasons for not being tested previously by respondents accessing VCT at a mobile testing site (Morin 2006).

Making rapid HIV testing more broadly available and accessible could have a considerable effect on the prevention of HIV infection and uptake of results in developing countries. In southwestern Uganda, an intervention to deliver HIV test results to people in their homes increased the uptake of results from 10% to 37% (Wolff 2005). Likewise, after the implementation of home‐based VCT in Uganda, 5000 people in 2000 homes received VCT over a one‐year period. In more than 65% of the homes, at least one family member agreed to participate in testing (Murana 2005). A cohort study in Rakai district in southwestern Uganda also showed an increase in VCT uptake from 35% to 65% (Matovu 2002). Equally, in Mukono (a rural Ugandan district), one‐time delivery of HIV results after community‐wide mobilization achieved an uptake of 93% (Were 2003). In a bid to scale up VCT, Lesotho also has embarked on a nationwide, home‐based VCT program (WHO 2005). By the end of 2007, it was expected that all households would be offered HIV tests through door‐to‐door VCT services. The impact of this program in getting people into care and changing their sexual behaviour was anticipated to be significant (WHO 2005).

Most of the home‐based VCT programs targeted family members of HIV‐infected persons to initiate care services for HIV‐positive individuals and preventive interventions for those with undiagnosed HIV infection. A program in eastern Uganda identified previously undiagnosed HIV infection in 25% of adult family members and recruited 10% of children of index clients into an antiretroviral program (Mermin 2005, Were 2003). In the same location, of the 176 HIV‐positive family members tested, 74% had HIV infection and had not been tested previously (Were 2006). Home‐based VCT has many other advantages. In addition to increasing VCT coverage, it may improve HIV prevention efforts, enhance HIV awareness, and provide an entry point to home‐based care (Were 2006).Testing household members increases family diagnosis of HIV infection, and targeting older siblings of index HIV‐exposed children can reduce paediatric mortality. In Guyana, testing older siblings of HIV‐exposed infants has been implemented and has shown encouraging results (Guyana 2005). Moreover, home‐based VCT encourages disclosure of HIV status, reduces depression and anxiety, enhances family adherence and support, and increases risk reduction within HIV‐discordant couples. The Ugandan VCT model focusing on home‐based counselling at the time people received HIV test results was highly acceptable to the community and also increased the uptake of HIV results compared to facility‐based VCT (Wolff 2005).

Confidentiality of HIV test results at home often is cited as a reason for skepticism about wider implementation of home‐based VCT. In one of the Ugandan experiences, confidentiality was not breached when more than 300 individuals were tested. Fears of unfavourable social occurrences after home‐based VCT were also proven unfounded when positive social relationships and community support substantially increased three months after enrolment (Were 2006). Gaps and challenges

The rate of VCT coverage in many developing countries is low. It is a considerable challenge to get families and couples to attend healthcare facilities for HIV testing. Given the low uptake of facility‐based testing and the urgent need to respond to the HIV epidemic, home‐based VCT may be an alternative model to increase VCT uptake and coverage in developing countries. Primary studies have evaluated the uptake of VCT in various settings and more recently in the home environment. However, no systematic review has been conducted to establish the most effective method to increase the uptake of HIV testing. Our review assessed the effectiveness of home‐based VCT to improve uptake of HIV testing.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of home‐based HIV VCT in improving the uptake of HIV testing

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing home‐based VCT with alternative VCT models, including facility‐based VCT. Both published and unpublished studies were considered for inclusion. Studies comparing the intervention group with historical controls were excluded.

Types of participants

Adults (male and female), aged ≥15 years, either HIV negative or unaware of HIV status, were screened for HIV infection after giving informed consent. Developing countries were defined as low‐ and middle‐income countries with a score of <0.9 on the Human Development Index (UNDP 2006).

Types of interventions

Intervention group: Home‐based VCT is defined as the provision of HIV voluntary counselling, or testing, or both, in the home with any of the following features:

Provision of pre‐test counselling in the home followed by: "performance of HIV rapid testing at home" or "drawing specimens" that are later sent to laboratories for HIV testing;

Provision of HIV test results and post‐test counselling in the home;

Referral for care of home‐based study participants who have HIV‐positive test results.

Comparison group: Alternative VCT delivery methods outside the home environment, including in hospitals, stand‐alone VCT sites, health centres, and mobile clinics.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were HIV pre‐test counselling accepted, HIV post‐test counselling offered and test results received, and HIV infection diagnosed based on rapid tests.

The secondary outcome measure was mean score on subject satisfaction level with quality of VCT received.

Search methods for identification of studies

The original review, published in 2007, used a search strategy developed for the HIV/AIDS Review Group. Relevant trials were identified in MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL, AIDSearch, LILACS, CINAHL and Sociofile. In addition, we contacted authors who had published on the topic for unpublished and ongoing studies.

For this update of the review, the search strategy was further refined in 2008 with the assistance of the HIV/AIDS Review Group's Trials Search Coordinator. We formulated a comprehensive and exhaustive search strategy in an attempt to identify all new relevant studies regardless of publication status (published, unpublished, in press, and in progress).

There was no restriction on language or publication status in our search. We used the following broad search terms: "HIV," "voluntary counselling and testing" and "home‐based" in combination with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy and the HIV/AIDS search strategy developed by the Cochrane HIV/AIDS Review Group.

We searched the following electronic databases:

MEDLINE (1980 to 2008), in February 2007 and again in December 2008 using the strategy documented in Appendix 1: PubMed Search Strategy: 5 December 2008.

Embase online (1980‐2008), in February 2007 and again in December 2008 using the strategy documented in Appendix 2: EMBASE Search Strategy: 5 December 2008.

(CENTRAL (1980‐2008), in December 2008 using the search strategy documented in Appendix 3: Cochrane Library Search Strategy: 5 December 2008.

NLM Gateway (2007‐2008), Searched December 2008 using the strategy documented in Appendix 4: NLM GATEWAY Search Strategy: 5 December 2008

AIDSearch which also includes major AIDS meetings [(International AIDS Society (IAS) Pathogenesis and Treatment (2001 to 2005), International AIDS Conferences (1985 to 2006), Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (1996 to 2006) and] conference abstracts (1980‐2007), in February 2007 using the search strategy documented in Appendix 5: AIDSearch Search Strategy: February 2007. This database was not searched in December 2008 as it ceased publication in 2008.

Other databases searched include LILACS, CINAHL and Sociofile, searched in December 2008 using the broad search terms: "HIV," "voluntary counselling and testing" and "home‐based."

We contacted authors who have published on the topic to establish if they were aware of any unpublished or ongoing studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

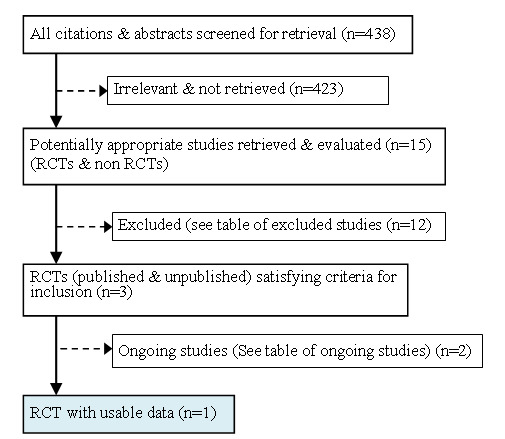

All studies identified from various sources were read and screened independently by two authors (MB and OA) for eligibility. Differences between the authors were resolved by the third author (SMK) in consultation with the editors of the HIV/AIDS Review Group. Studies were included if they met the inclusion criteria. The reasons for exclusion of studies were documented. See "Characteristics of excluded studies" and study the flow diagram (Figure 3).

3.

Flowchart: Study selection

Data extraction

The authors (MB, OA) independently extracted data using the pre‐designed data extraction forms. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or in consultation with the third author (SMK). Where data were unclear or missing, authors were contacted for additional information. The identified ongoing studies were listed in the table of ongoing studies. (See “Characteristics of ongoing studies"). The following data were extracted when available (See "Characteristics of included studies"): administrative details (identification, authors, publication status, year the study was conducted); methods (study design, recruitment method, number of participants enroled and recruited and analysed, setting, type of HIV tests and testing site, consent and ethical approval); participants (age, location, socio‐economic status, history of previous HIV testing; inclusion and exclusion criteria); intervention (type, duration); outcomes (subjects who accepted counselling and testing); study results (number of participants experiencing the event and the total number in each group for dichotomous outcomes); and notes.

Assessment of methodological quality of included studies

The authors (MB and OA) independently evaluated the elements of included trials for risk of bias using a standard form. They included the randomisation method to generate allocation sequence; the adequacy of allocation concealment; blinding (i.e. providers, participants, outcome assessors); incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other sources of bias.The methodological quality of the selected studies also was assessed independently and classified as "yes," "unclear," or "no" based on the methods described in the Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook (Higgins 2005) and the editorial policy of the HIV/AIDS Review Group on inclusion and appraisal of experimental and non‐experimental (observational) studies (Cochrane 2006), and with guidance from the Cochrane Non‐Randomised Studies Methods Group.

Data analysis

Only one cluster randomised study (Fylkesnes 2004) was included in the current review. Data were not entered into Review Manager (RevMan) software (RevMan 2003) because the authors did not describe if or how they had adjusted for the clustering effect in their study. Likewise, we were unable to determine the cluster size or the intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICC), and we did not have the necessary information to estimate the ICC for the study. Hence, we reported the findings in the text without calculating a relative risk (with 95% confidence interval). The study did not report our secondary outcome of interest.

Results

Description of studies

The search strategy identified 15 relevant studies from all sources (Figure 3). Of the 15 studies, 12 were excluded (See "Table of excluded studies"), two were ongoing (See "Table of ongoing studies"), and only one study met the inclusion criteria (Fylkesnes 2004).

Included studies

The only study included was a cluster randomised study (Fylkesnes 2004) (n=2445) conducted in Chelston, a residential area in Lusaka, Zambia. The study participants are described in the table of included studies. Ten clusters (enumeration areas) representing 44% of all households from a previous survey (Fylkesnes 1999) were randomly selected and randomised to receive VCT at the "local clinic" (n=1102) or at an "optional location" (n=1343). Later, 442 and 407 subjects from the clusters who were randomised to receive VCT at the local clinic and an optional location, respectively, expressed their willingness to be tested. Subjects from the optional‐location group were visited at home by a counsellor and were offered to choose the setting for counselling (home, clinic, or other location). The majority (84%) selected home‐based counselling. A day later, they were revisited at home by a counsellor, gave consent, received pre‐test counselling, and gave a sample of blood for HIV testing. The next day, a counsellor returned for home post‐test counselling. Subjects in the local‐clinic location group received both VCT and test results on the same day at a nearby clinic. Blood samples from both groups were tested at the local clinic. Primary outcomes were subjects' readiness to be tested, accepting pre‐test counselling, accepting both pre‐test counselling and testing, and accepting both post‐test counselling and receiving results.

Excluded studies

Spielberg 2000 was conducted in the United States and compared receipt of results by telephone versus clinic visit. This study was excluded because it did not compare home‐based HIV testing against another testing model.

Suggaravetsiri 2003 offered household members HIV testing at home, but there was no comparison group. This study was excluded for lack of a comparison group.

Were 2003 was conducted in a rural Ugandan district where one‐time delivery of HIV results was implemented after community‐wide mobilization. The study was excluded because results were published as a letter without critical study details and because attempts to contact the authors failed.

Wolff 2005 was a non‐randomised (pre‐post) comparative study that compared the uptake of HIV‐test results during two time periods following implementation of home delivery of test results. The study was excluded because it did not satisfy the criteria for an RCT.

Yoder 2006 was conducted in Uganda and assessed acceptance or refusal of results at home following VCT after a survey. The study was excluded because there was no comparison.

Ongoing studies

Currently, two ongoing studies (Charlebois 2007; Jaffar 2005) in Uganda are assessing the effectiveness of home‐based VCT. The Charlebois study (Charlebois 2007) has started recruiting patients from the clinic in Mulago, Kampala. The study will randomise 600 households (family and members) of index TB patients to home‐based VCT and TB‐clinic‐based VCT groups to assess the uptake of HIV testing and the effectiveness of the two interventions in linking those who test positive to care. In the Jaffar study (Jaffar 2005), patient recruitment has ended and follow‐up continues. The data from these two studies will be included in this review when available.

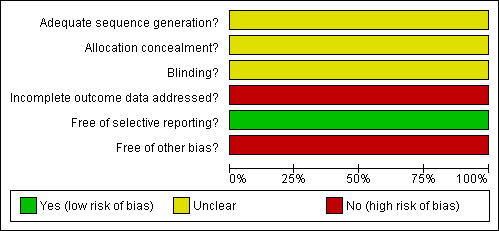

Risk of bias in included studies

See Characteristics of included studies for full details, Figure 4: Methodological quality graph, and Figure 5: Methodological quality summary for graphical summary of risk of bias.

4.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgments about each methodological quality item presented as percentages in included study

5.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgments about each methodological quality item for included study

Allocation sequence generation: The study did not describe the method used for generating the random allocation sequence of clusters (enumeration areas) and study participants. Hence, the risk of bias regarding this domain was marked as unclear.

Allocation concealment: The method of allocation concealment used was not clearly stated. As a result, we were unable to decide the level of risk of bias introduced into the trial. We rated this domain as unclear.

Blinding: The study did not report blinding of investigators, counsellors, laboratory technicians or participants. Therefore, the risk of bias was graded as unclear. However, counsellors collected blood specimens from participants and took them to a local health facility for HIV testing. They also collected and delivered test results to participants at home. It is possible that both counsellors and assessors (laboratory technicians) were not blinded.

Incomplete outcome data: The risk of bias due to incomplete outcome reporting was rated as high in the study. A significant number of randomised subjects were excluded from analysis for not agreeing to HIV testing (i.e. 60% from the local clinic and 70% from the optional location).

Selective outcome reporting: The study stated that the primary outcome of interest was acceptability of HIV VCT. The risk of bias associated with this domain is low.

Other bias: The cluster sizes or the ICC were not reported by authors.

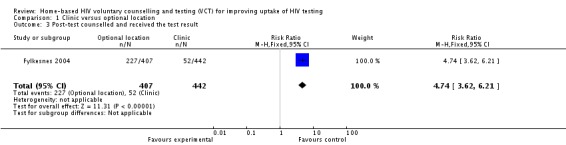

Effects of interventions

This review included only one study (Fylkesnes 2004) the data of which were not entered into RevMan (RevMan 2003) to calculate the relative risk with the 95% confidence interval because the authors reported neither the cluster sizes nor the ICC to adjust for the clustering in the study. We also did not have the necessary information to calculate an ICC. Hence, we reported the results in the text below.

This cluster randomised study compared VCT uptake between the local clinic and an optional location. The optional location included home, clinic, or other locations. Initially, 2445 subjects from 10 clusters (enumeration areas) were randomised to the local clinic (n=1102) and an optional location, mostly at home (n=1343). Over half (65.3%, n=1596) did not want to be tested after randomisation (n=660 (60%) local clinic, n=936 (70%) optional location) and only 34.7% (n=849) of the total number of people randomised expressed willingness to be tested from the two groups (n=442 local clinic, n=407 optional location). Authors assessed the primary outcomes based on participants who expressed willingness to be tested after randomisation and reported their findings as follows.

Primary outcomes:

Pre‐test counselled only: The acceptability of pre‐test counselling alone was 13.3% (59/442) and 61.4% (250/407) in the clinic and optional location groups, respectively (RR=4.6; 95% CI 3.58 to 5.91).

Pre‐test counselled and HIV tested: In the clinic group, the acceptability of pre‐test counselling and HIV testing was 12.4% (55/442) compared to 57% (231/407) in the optional group (RR=4.6; 95% CI 3.51 to 5.92).

Post‐test counselled and received the test result: The proportion of subjects who were post‐test counselled and who received their result was 12% (52/442 ) and 56% (227/407) between VCT at the local clinic and at home, respectively (RR=4.7; 95% CI 3.62 to 6.21).

Diagnosis of HIV infection: No data were reported.

Secondary outcome: Did not report on level of subject satisfaction with quality of VCT received.

Discussion

The human immunodeficiency virus is a major public health problem in developing countries. Early diagnosis based on HIV testing is a central component of comprehensive HIV prevention programs. Regrettably, VCT uptake in developing countries is poor. Testing can be provided at health facilities, free‐standing sites, homes, market places, schools, and other sites. Many developing countries are now placing increased emphasis on home‐based HIV VCT as a public health intervention. Massive scale‐up of home‐based VCT is taking place in Lesotho, Swaziland (WHO 2005), and Botswana (Botswana 2003; Weiser 2006). Uganda and Lesotho have already implemented home‐based VCT. In developed countries, such as the United States, widespread promotion of HIV VCT has improved uptake, with nearly 50% of people aged 15‐44 years old reporting having had an HIV test. As a result of the implementation of home collection and self‐testing (Hutchison 2006), the need for home‐based VCT implementation may be less (Anderson 2005) in developed countries. This review was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of home‐based VCT.

There were no published studies of home‐based VCT from developed countries and only one published cluster randomised study (Fylkesnes 2004) from a developing country. This study (Fylkesnes 2004) was based on acceptability of HIV counselling and testing in urban Zambia. The study showed an increase in uptake of VCT among participants who were offered VCT at an optional testing location (including home‐based VCT) away from a healthcare facility when compared to participants who were offered VCT at a healthcare facility. However, the study has limitations. Over 65% (1596) of the total subjects did not agree to testing after randomisation (70% from the optional location group, 60% from the facility group). Data were analysed based on those who expressed willingness to be tested and not with intention to treat. Equally, it was unclear how the authors adjusted for the clustering effect in their analysis. Despite it being requested, the authors did not offer any information about the cluster sizes, and we were unable to establish the ICC in order to adjust for the clustering in the study. As a result, data were not entered into RevMan to calculate the relative risk (and 95% CI) for their primary outcomes. Instead, we reported their findings in text in this review.

There are several limitations with the current review. Only one study was identified and included in the review. The data could not be entered into RevMan due to the abovementioned reasons. We had initially planned to evaluate subject satisfaction levels with quality of VCT received (secondary outcome). However, these data were not reported in the study as an outcome.

Various issues require further research in the context of home‐based VCT in developing countries. Home‐based testing has many advantages. It circumvents the stigma associated with going for testing, especially to a free‐standing VCT site, and it is more likely to lead to detection of undiagnosed HIV (Were 2006) and to identify discordant couples. Given these advantages, home‐based VCT may be an effective way of delivering HIV prevention services in populations not reached by earlier prevention efforts. Testing and receipt of results at home also is associated with more confidentiality than testing and receipt of results in facilities (Yoder 2006). Although one non‐randomised comparative (pre/post evaluation) study (Wolff 2005) not included in the review supported higher uptake of results at home, at present there is no conclusive evidence to indicate that home‐based VCT is superior to other HIV VCT models. It also is unclear how the testing behaviours of persons in rural settings differ from or are similar to those in urban areas within home‐based VCT. The included study (Fylkesnes 2004) was primarily conducted in an urban setting where the socio‐demographic characteristics and testing behaviours of participants may be different from those of people residing in rural areas.

Based on the available evidence, the impact of home‐based VCT on the uptake of HIV testing is unclear in developing countries. More research is needed to determine the potential impact of home‐based VCT on increasing the uptake of HIV testing.

Currently, there are two ongoing randomised studies on the review topic in Uganda (Charlebois 2007, Jaffar 2005). Attempts to obtain data from the investigators were unsuccessful. The results from these studies will be included when they become available.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Due to limited research conducted to date, there is no strong evidence to indicate the effectiveness of home‐based testing for increasing VCT uptake in developing countries. Current sources of data on home‐based testing are limited to one study in Zambia, and the study was not methodologically rigorous. Hence, based on the available evidence, we cannot recommend large‐scale implementation of home‐based VCT in developing countries in preference to other forms of HIV counselling and testing.

Implications for research.

Some African countries have already implemented home‐based VCT and others are considering it as one of the central elements of their HIV prevention program. However, no systematic evaluation has yet been conducted to assess the effects of home‐based testing in comparison to other VCT approaches. There is a need for further research to provide reliable evidence on the beneficial impact of home‐based testing on VCT uptake and other HIV prevention‐related outcomes in developing countries. Likewise, given the significant cost involved in implementing the program, future studies should examine the cost‐effectiveness of the method compared to alternative testing models (routine/opt‐out, home self‐testing, mobile vans, standard facility). The results from two ongoing studies in Uganda may clarify the beneficial effect of home‐based testing.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 June 2010 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New search (July 2008). |

| 16 June 2010 | New search has been performed | Also corrected an error in calculating confidence intervals (re: Fylkesnes 2004) in the previous published version of the review. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2007 Review first published: Issue 4, 2007

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 June 2009 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

Dr Moses Bateganya was awarded the Reviews for Africa Programme Fellowship (www.mrc.ac.za/cochrane/rap.htm) funded by a grant from the Nuffield Commonwealth Program, through The Nuffield Foundation. He is also part of the HIV/AIDS Mentoring Programme. In addition, the authors wish to acknowledge Joy Oliver and Elizabeth Pienaar for their contribution in reporting search results and other editorial advice during the revision.

Appendices

Appendix 1. PubMed Search Strategy: 5 December 2008

| Search | Most Recent Queries | Time | Result |

| #6 | Search #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 Limits: Publication Date from 2007/02/26 to 2008/12/05 | 02:00:50 | 94 |

| #5 | Search #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 | 01:58:19 | 676 |

| #4 | Search VOLUNTARY COUNSELLING OR VOLUNTARY COUNSELING OR VOLUNTARY TESTING OR HIV TESTING OR VCT OR HBVCT | 01:57:50 | 27585 |

| #3 | Search HOME‐BASED OR HOME BASED OR HOMEBASED OR door to door OR door‐to‐door OR home care services OR homecare services OR homecare OR home care OR home‐care OR home access OR home OR in‐home OR domicile | 01:57:37 | 561073 |

| #2 | Search randomised controlled trial [pt] OR controlled clinical trial [pt] OR randomised controlled trials [mh] OR random allocation [mh] OR double‐blind method [mh] OR single‐blind method [mh] OR clinical trial [pt] OR clinical trials [mh] OR ("clinical trial" [tw]) OR ((singl* [tw] OR doubl* [tw] OR trebl* [tw] OR tripl* [tw]) AND (mask* [tw] OR blind* [tw])) OR ( placebos [mh] OR placebo* [tw] OR random* [tw] OR research design [mh:noexp] OR comparative study [mh] OR evaluation studies [mh] OR follow‐up studies [mh] OR prospective studies [mh] OR control* [tw] OR prospectiv* [tw] OR volunteer* [tw]) NOT (animals [mh] NOT human [mh]) | 01:57:16 | 2990040 |

| #1 | Search HIV Infections[MeSH] OR HIV[MeSH] OR hiv[tw] OR hiv‐1*[tw] OR hiv‐2*[tw] OR hiv1[tw] OR hiv2[tw] OR hiv infect*[tw] OR human immunodeficiency virus[tw] OR human immune deficiency virus[tw] OR human immuno‐deficiency virus[tw] OR human immune‐deficiency virus[tw] OR ((human immun*) AND (deficiency virus[tw])) OR acquired immunodeficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immunodeficency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome[tw] OR ((acquired immun*) AND (deficiency syndrome[tw])) OR "sexually transmitted diseases, viral"[MESH:NoExp] | 01:56:53 | 238257 |

Appendix 2. Em base Search Strategy: 5 December 200 8

| No. | Query | Results | Date |

| #3 | (('human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus infection') OR ('human immunodeficiency virus infection'/de OR 'human immunodeficiency virus infection')) OR ((('human immunodeficiency virus'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus') OR ('human immunodeficiency virus'/de OR 'human immunodeficiency virus'))) OR (hiv:ti OR hiv:ab) OR ('hiv‐1':ti OR 'hiv‐1':ab) OR ('hiv‐2':ti OR 'hiv‐2':ab) OR ('human immunodeficiency virus':ti OR 'human immunodeficiency virus':ab) OR ('human immuno‐deficiency virus':ti OR 'human immuno‐deficiency virus':ab) OR ('human immunodeficency virus':ti OR 'human immunodeficency virus':ab) OR ('human immune‐deficiency virus':ti OR 'human immune‐deficiency virus':ab) OR ('acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome':ti OR 'acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome':ab) OR ('acquired immunodeficency syndrome':ti OR 'acquired immunodeficency syndrome':ab) OR ('acquired immunodeficiency syndrome':ti OR 'acquired immunodeficiency syndrome':ab) OR ('acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome':ti OR 'acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome':ab) | 284,959 | 05 Dec 2008 |

| #4 | random*:ti OR random*:ab OR factorial*:ti OR factorial*:ab OR cross?over*:ti OR cross?over:ab OR crossover*:ti OR crossover*:ab OR placebo*:ti OR placebo*:ab OR ((doubl*:ti AND blind*:ti) OR (doubl*:ab AND blind*:ab)) OR ((singl*:ti AND blind*:ti) OR (singl*:ab AND blind*:ab)) OR assign*:ti OR assign*:ab OR volunteer*:ti OR volunteer*:ab OR (('crossover procedure'/de OR 'crossover procedure') OR ('crossover procedure'/de OR 'crossover procedure')) OR (('double‐blind procedure'/de OR 'double‐blind procedure') OR ('double‐blind procedure'/de OR 'double‐blind procedure')) OR (('single‐blind procedure'/de OR 'single‐blind procedure') OR ('single‐blind procedure'/de OR 'single‐blind procedure')) OR (('randomized controlled trial'/de OR 'randomized controlled trial') OR ('randomized controlled trial'/de OR 'randomized controlled trial')) OR allocat*:ti OR allocat*:ab | 833,825 | 05 Dec 2008 |

| #5 | 'home based' OR (('home'/de OR 'home') OR ('home'/de OR 'home')) AND based OR homebased OR door AND to AND door OR door‐to‐door OR (('home'/de OR 'home') OR ('home'/de OR 'home')) AND care AND services OR (('homecare'/de OR 'homecare') OR ('homecare'/de OR 'homecare')) AND services OR (('homecare'/de OR 'homecare') OR ('homecare'/de OR 'homecare')) OR (('home'/de OR 'home') OR ('home'/de OR 'home')) AND care OR (('home care'/de OR 'home care') OR ('home care'/de OR 'home care')) OR (('home'/de OR 'home') OR ('home'/de OR 'home')) AND access OR (('home'/de OR 'home') OR ('home'/de OR 'home')) OR 'in home' OR domicile | 166,809 | 05 Dec 2008 |

| #6 | voluntary AND (('counselling'/de OR 'counselling') OR ('counselling'/de OR 'counselling')) OR voluntary AND (('counselling'/de OR 'counselling') OR ('counselling'/de OR 'counselling')) OR voluntary AND testing OR (('hiv'/de OR 'hiv') OR ('hiv'/de OR 'hiv')) AND testing OR vct OR hbvct | 13,162 | 05 Dec 2008 |

| #7 | #3 AND #4 AND #5 AND #6 | 26 | 05 Dec 2008 |

| #8 | #3 AND #4 AND #5 AND #6 AND [2007‐2008]/py | 6 | 05 Dec 2008 |

Appendix 3. Cochrane Library Search: 5 December 2009

| ID | Search | Hits |

| #1 | hiv OR hiv‐1* OR hiv‐2* OR hiv1 OR hiv2 OR (HIV INFECT*) OR (HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS) OR (HUMAN IMMUNEDEFICIENCY VIRUS) OR (HUMAN IMMUNE‐DEFICIENCY VIRUS) OR (HUMAN IMMUNO‐DEFICIENCY VIRUS) OR (HUMAN IMMUN* DEFICIENCY VIRUS) OR (ACQUIRED IMMUNODEFICIENCY SYNDROME) OR (ACQUIRED IMMUNEDEFICIENCY SYNDROME) OR (ACQUIRED IMMUNO‐DEFICIENCY SYNDROME) OR (ACQUIRED IMMUNE‐DEFICIENCY SYNDROME) OR (ACQUIRED IMMUN* DEFICIENCY SYNDROME), from 2007 to 2008 | 1097 |

| #2 | MeSH descriptor HIV Infections explode all trees in MeSH products, from 2007 to 2008 | 15 |

| #3 | MeSH descriptor HIV explode all trees in MeSH products, from 2007 to 2008 | 15 |

| #4 | ((ANIMAL OR ANIMALS) AND (NOT HUMANS)) , from 2007 to 2008 | 31 |

| #5 | HOME‐BASED OR HOME BASED OR HOMEBASED OR door to door OR door‐to‐door OR home care services OR homecare services OR homecare OR home care OR home‐care OR home access OR home OR in‐home OR domicile, from 2007 to 2008 | 1638 |

| #6 | VOLUNTARY COUNSELLING OR VOLUNTARY COUNSELING OR VOLUNTARY TESTING OR HIV TESTING OR VCT OR HBVCT, from 2007 to 2008 | 527 |

| #7 | (#1 OR #2 OR #3), from 2007 to 2008 | 1097 |

| #8 | (#5 AND #6 AND #7), from 2007 to 2008 | 57 |

| #9 | (#8 AND NOT #4), from 2007 to 2008 | 57 |

Appendix 4. NLM GATEWAY Search Strategy : 5 December 200 8

| Number | Search | Items Found |

| #6 | Search: (#1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4) Limit: 2007:2008 | 185 |

| #5 | Search: (#1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4) | 1127 |

| #4 | Search: VOLUNTARY COUNSELLING OR VOLUNTARY COUNSELING OR VOLUNTARY TESTING OR HIV TESTING OR VCT OR HBVCT | 42270 |

| #3 | Search: HOME‐BASED OR HOME BASED OR HOMEBASED OR door to door OR door‐to‐door OR home care services OR homecare services OR homecare OR home care OR home‐care OR home access OR home OR in‐home OR domicile | 603654 |

| #2 | Search: ((randomized controlled trial [pt] OR controlled clinical trial [pt] OR randomized controlled trials [mh] OR random allocation [mh] OR double‐blind method [mh] OR single‐blind method [mh] OR clinical trial [pt] OR clinical trials [mh] OR ("clinical trial" [tw]) OR ((singl* [tw] OR doubl* [tw] OR trebl* [tw] OR tripl* [tw]) AND (mask* [tw] OR blind* [tw]))) OR (( placebos [mh] OR placebo* [tw] OR random* [tw] OR research design [mh:noexp] OR comparative study [mh] OR evaluation studies [mh] OR follow‐up studies [mh] OR prospective studies [mh] OR control* [tw] OR prospectiv* [tw] OR volunteer* [tw]))) NOT (animals [mh] NOT human [mh]) | 3188582 |

| #1 | Search: (HIV Infections[MeSH] OR HIV[MeSH] OR hiv[tw] OR hiv‐1*[tw] OR hiv‐2*[tw] OR hiv1[tw] OR hiv2[tw] OR hiv infect*[tw] OR human immunodeficiency virus[tw] OR human immunodeficency virus[tw] OR human immuno‐deficiency virus[tw] OR human immune‐deficiency virus[tw] OR ((human immun*) AND (deficiency virus[tw])) OR acquired immunodeficiency syndrome[tw]) OR (acquired immunodeficency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome[tw] OR ((acquired immun*) AND (deficiency syndrome[tw])) OR "sexually transmitted diseases, viral"[MESH:NoExp]) | 336828 |

Appendix 5. AIDSearch Sear ch Strategy : February 2007

| #1 | PT=RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL |

| #2 | PT=CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIAL |

| #3 | RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS |

| #4 | RANDOM ALLOCATION |

| #5 | DOUBLE BLIND METHOD |

| #6 | SINGLE BLIND METHOD |

| #7 | PT=CLINICAL TRIAL |

| #8 | CLINICAL TRIALS OR CLINICAL TRIALS, PHASE 1 OR CLINICAL TRIALS, PHASE II OR CLINICAL TRIALS, PHASE III OR CLINICAL TRIALS, PHASE IV OR CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIALS OR MULTICENTER STUDIES |

| #9 | (SINGL* OR DOUBL* OR TREBL* OR TRIPL*) NEAR6 (BLIND* OR MASK*) |

| #10 | CLIN* NEAR6 TRIAL* |

| #11 | PLACEBO* |

| #12 | PLACEBOS |

| #13 | RANDOM* |

| #14 | RESEARCH DESIGN |

| #15 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 |

| #16 | ANIMALS NOT (HUMAN AND ANIMALS) |

| #17 | #15 NOT #16 |

| #18 | HOME‐BASED OR HOME BASED OR HOMEBASED OR door to door OR door‐to‐door OR home care services OR homecare services OR homecare OR home care OR home‐care OR home access OR home OR in‐home OR domicile |

| #19 | VOLUNTARY COUNSELLING OR VOLUNTARY COUNSELING OR VOLUNTARY TESTING OR HIV TESTING OR VCT OR HBVCT |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Clinic versus optional location.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pre‐test counselled only | 1 | 849 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.60 [3.58, 5.91] |

| 2 Pre‐test counselled and HIV tested | 1 | 849 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.56 [3.51, 5.92] |

| 3 Post‐test counselled and received the test result | 1 | 849 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.74 [3.62, 6.21] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Clinic versus optional location, Outcome 1 Pre‐test counselled only.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Clinic versus optional location, Outcome 2 Pre‐test counselled and HIV tested.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Clinic versus optional location, Outcome 3 Post‐test counselled and received the test result.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Fylkesnes 2004.

| Methods | Cluster randomised study conducted in Chelston, a residential area of Lusaka, Zambia. Using the Zambian census of population mapping system, 24 standard enumeration areas (SEA) in Chelston (2786 households) was established. Ten clusters or SEAs (44% of all households) were selected by probability proportional to the measure of size using the number of households in each area (Fylkesnes 1999; Fylkesnes 2004). In the sampled SEAs, all households and members aged ≥15 years were listed and contacted. Two thousand four hundred forty‐five subjects from 10 clusters (SEAs), aged ≥15 years, were randomised. Later, 849 subjects expressed willingness to participate in the study (i.e. to be tested for HIV). The study obtained ethical approval from the National AIDS Research Committee of Zambia. Participants gave informed consent. | |

| Participants | Men and women household members aged ≥15 years who lived in 10 clusters or enumeration areas in Chelston, found at home during the time of the survey and who expressed willingness to be tested for HIV. No exclusion criteria reported. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group (VCT at optional location): A counsellor conducted home visits and offered subjects a choice of counselling at home, clinic or other location. The majority (84%) elected home counselling. The following day, a counsellor visited subjects at home and obtained consent, offered pre‐test counselling and collected blood for HIV testing. A counsellor revisited subjects the next day for post‐test counselling Control group (VCT at local clinic): Gave blood for HIV testing, received VCT and results at local clinic on the same day |

|

| Outcomes | Acceptability was defined as using services and was measured at three stages: Pre‐test counselled only, pre‐test counselled and HIV tested, and post‐test counselled and received the test result. | |

| Notes | The study was conducted in 1999. Counsellors were recruited from different geographical areas. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Randomisation method not clearly reported. Authors reported as "The sampling design to select 10 clusters (SEAs) was probability proportional to the measure of size using the number of households in each area." No detail on how participants were recruited after the 10 clusters were selected. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Blood specimen from subjects was collected by counsellors and tested by technicians at a local facility. No detail if participants, counsellors or technicians were blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Randomisation included 2445 subjects, but analysis excluded 1596 (65.3% of total subjects randomised) because they did not agree to HIV testing (60% for the local clinic and 70% for the optional location). |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | We had no access to the study protocol, but the study stated that acceptability of VCT was the primary outcome. |

| Free of other bias? | High risk | Authors did not account for clustering in the analysis. Cluster sizes or the ICC were not reported. The unit of analysis was at subject level and not at cluster level (enumeration areas). |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Bunnell 2006 | Prospective study offered home‐based HIV testing to all participants and their household members but no control (facility‐based testing) |

| Corbett 2007 | Cluster‐randomised study (retrospective secondary analysis) investigated the effects of delivery of counselling and testing on HIV incidence among employees at work places. No comparison group and not home‐based VCT |

| Corbett 2006 | Cluster randomised study. Compared VCT uptake at work place on‐site and offsite. Home‐based VCT was not offered |

| Fylkesnes 1999 | This study was part of a population‐based survey. Counselling, testing and receipt of HIV results did not occur at the home setting. Although it evaluated VCT uptake, it did not address the review question. |

| Hutchison 2006 | A review without original data |

| Kassler 1998 | Evaluated two HIV testing protocols. Rapid testing and same‐day results versus standard protocol with results after two weeks |

| Matovu 2002 | Presented experiences on provision of VCT in a research setting |

| Spielberg 2000 | Study was conducted in the United States. It compared dry blood spots to oral fluid collection for HIV testing and also compared receipt of results by phone or by clinic visit. Did not compare home‐based HIV testing against other testing model. |

| Suggaravetsiri 2003 | Household members were offered HIV testing at home, but there was no comparison group. |

| Were 2003 | The study results were published as a letter without critical study details. Attempts to contact the authors failed. |

| Wolff 2005 | The study was a non‐randomised (pre‐post) comparative study of home delivery of HIV test results and not home testing among serosurvey participants in four villages where a population cohort was established since 1990 for an annual HIV serologic survey (Seeley 1991). The study only compared the uptake of HIV‐test results (percentages and rate ratios) in the year the option of home delivery was introduced and the previous year when test results were collected only at a local facility. The study did not satisfy the criteria for an RCT comparing home‐ and facility‐based testing. |

| Yoder 2006 | The home‐based VCT survey only assessed acceptance or refusal of results at home. Participants were not given an option of receipt of results at an alternative site. |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Charlebois 2007.

| Trial name or title | Family‐Based HIV Voluntary counselling and testing in Patients at Risk for Tuberculosis in Kampala, Uganda |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial involving 600 households of index TB patients or those suspected to have TB and compare uptake of testing between home‐based VCT and TB‐clinic‐based VCT for family and household members |

| Participants | Household members of patients being evaluated for TB |

| Interventions | Home‐based voluntary counselling and testing |

| Outcomes | Uptake of VCT and linkage of those who test HIV‐positive to care |

| Starting date | 2007 |

| Contact information | Dr Edwin Charlebois, University of California, San Francisco, USA |

| Notes | This study has started recruiting patients at the TB clinic in Mulago Kampala and is expected to stop recruitment in 2011 |

Jaffar 2005.

| Trial name or title | Comparison of Facility and Home‐Based ART Delivery Systems in Uganda |

| Methods | Cluster randomised trial. The study catchment divided into clusters and the clusters were stratified into nine strata according to urban/rural area, distance to the TASO Jinja clinic, and estimated number of HIV‐infected subjects. The strata contained between two and eight clusters each. Within each stratum, equal numbers of clusters were randomised to the two study arms (home‐based and facility‐based treatment). |

| Participants | Household members aged ≥18 years of index patients were recruited into the home‐ and facility‐based arms of the study |

| Interventions | Household HIV testing |

| Outcomes | Acceptability of HIV testing |

| Starting date | 2005 |

| Contact information | Shabbar Jaffer PhD, London School of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, United Kingdom |

| Notes | Recruitment of patients in the main study ended and follow‐up continues. |

Contributions of authors

Dr Moses Bateganya conceived the review topic; screened citations; selected the relevant articles; entered, analysed and interpreted the data; and revised the review. Dr Omar Abdulwadud contributed to the development of the protocol; screened citations for relevance and inclusion; performed data entry, analysis, and interpretation; and revised the review. Dr Susan M. Kiene provided editorial advice, resolved disagreements regarding studies, performed quality assessment of included studies, and contributed to data interpretation.

Sources of support

Internal sources

-

Cochrane HIV/AIDS mentoring programme, South Africa.

Mentoring during the development of the protocol as well as during the revision

Reviews for Africa Programme Fellowship (www.mrc.ac.za/cochrane/rap.htm), funded by a grant from the Nuffield Commonwealth Program, throughThe Nuffield Foundation, UK.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

We declare that none of the authors has affiliation with or involvement in any organization or entity with a different financial interest in the subject matter of the review, for example, employment, consultancy, stock ownership, honoraria or expert testimony.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Fylkesnes 2004 {published data only}

- Fylkesnes K, Siziya S. A randomised trial on acceptability of voluntary HIV counseling and testing. Tropical Medicine and International Health 2004;9:566‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Bunnell 2006 {published data only}

- Bunnell R, Ekwaru JP, Solberg P, Wamai N, Kajura‐Bikako W, Were W, et al. Changes in sexual behavior and risk of HIV transmission after antiretroviral therapy and prevention interventions in rural Uganda. AIDS 2006;20:85‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Corbett 2007 {published data only}

- Corbett EL, Makamure B, Cheung YB, Dauya E, Matambo R, Bandason T, et al. HIV incidence during a cluster‐randomised trial of two strategies providing voluntary counseling and testing at the workplace, Zimbabwe. AIDS 2007;21:483‐89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Corbett 2006 {published data only}

- Corbett EL, Dauya E, Matambo R, Cheung YB, Makamure B, Bassett MT, et al. Uptake of workplace HIV counseling and testing: a cluster‐randomised trial in Zimbabwe. PLoS Med 2006;3(7):1005‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fylkesnes 1999 {published data only}

- Fylkesnes K, Haworth A, Rosensvard C, Kwapa PM. HIV counseling and testing: overemphasizing high acceptance rates a threat to confidentiality and the right to know. AIDS 1999;13:2469‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hutchison 2006 {published data only}

- Hutchison AB, Branson BM, Kim A, Farnham PG. A meta‐analysis of the effectiveness of alternative HIV counseling and testing methods to increase knowledge of HIV status. AIDS 2006;20:1597‐04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kassler 1998 {published data only}

- Kassler WJ, Alwano‐Edyegu MG, Marum E, Biryahwaho B, Kataaha P, Dillon B. Rapid HIV testing with same‐day results: a field trial in Uganda. International Journal of STD & AIDS 1998;9:134‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Matovu 2002 {published data only}

- Matovu JKB, Kigozi G, Nalugoda F, Wabwire‐Mangeni F, Gray RH. The Rakai Project counseling programme experience. Tropical Medicine and International Health 2002;7(12):1064‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Spielberg 2000 {published data only}

- Spielberg F, Critchlow C, Vittinghoff E, Coletti AS, Sheppard H, Mayer KH, et al. Home collection for frequent HIV testing: acceptability of oral fluids, dried blood spots and telephone results. AIDS 2000;14:1819‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Suggaravetsiri 2003 {published data only}

- Suggaravetsiri P, Yanai H, Chongsuvivatwong V, Naimpasan O, Akarasewi. Integrated counseling and screening for tuberculosis and HIV among household contacts of tuberculosis patients in an endemic area of HIV infection: Chiang Rai, Thailand. International Journal Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2003;7(12):S424‐31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Were 2003 {published data only}

- Were W, Mermin J, Bunnel R, Ekwaru JP, Kaharuza F. Home‐based model for HIV voluntary counseling and testing. Lancet 2003;361(9368):1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wolff 2005 {published data only}

- Wolff B, Nyanzi B, Katongole, Ssesanga D, Ruberantwari A, Whitworth J. Evaluation of a home‐based voluntary counseling and testing intervention in rural Uganda. Health Policy and Planning 2005;20(2):109‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yoder 2006 {published data only}

- Yoder PS, Katahoire AR, Kyaddondo D, Akol Z, Bunnell R, Kaharuza F. Home‐based HIV testing and counseling In a survey context in Uganda. United States Agency for Intenational Development 2006.

References to ongoing studies

Charlebois 2007 {unpublished data only}

- Charlebois E. Family‐based HIV voluntary counselling and testing in patients at risk for tuberculosis, Uganda. Ongoing study.

Jaffar 2005 {published and unpublished data}

- Jaffar S. Comparison of facility and home‐based ART delivery systems in Uganda. Ongoing study.

Additional references

Alcorn 2006

- Alcorn K, Smart T. Routine opt‐out counseling and testing: findings from the 2006 PEPFAR meeting. Third Annual PEPFAR Meeting, Durban South Africa. http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite. (accessed 18‐09‐06).

Anderson 2005

- Anderson JE, Chandra A, Mosher WD. HIV testing in the United States, 2002. Adv Data 2005;363:1‐32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Botswana 2003

- Botswana National Strategic Framework for HIV/AIDS 2003‐2009. Gabarone: National AIDS Coordinating Agency. http://openlibrary.org/b/OL3739126M/Botswana_national_strategic_framework_for_HIV_AIDS_2003‐2009 (Accessed August 2007).

CDC 2006

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Recommends Routine, Voluntary HIV Screening in Health Care Settings. http://www.cdc.gov/od/oc/media/pressrel/r060921.htm (accessed 22‐09‐06).

Cochrane 2006

- The Cochrane Collaborative Review Group on HIV Infection and AIDS. Inclusion and appraisal of experimental and non‐experimental (observation) studies. www.igh.org/Cochrane (accessed 21 September 2006).

Coovadia 2000

- Coovadia, Hoosen M. Access to Voluntary Counseling and Testing for HIV in Developing Countries. Annals of New York Academy of Sciences 2000;918:57‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

De Zoysa 1995

- Zoysa I, Phillips KA, Kamenga MC, O'Reilly KR, Sweat MD, White RA, et al. The role of HIV counseling and testing in changing risk behavior in developing countries. AIDS 1995;9 Suppl A:S95‐101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fylkesnes 1999

- Fylkesnes K, Haworth A, Rosenvard C, Kwapa PM. HIV counseling and testing: over emphasizing high acceptance rates a threat to confidentiality and the right not to know. AIDS 1999;13:2469‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gallo 2003

- Gallo RC, Montagnier L. The discovery of HIV as the cause of AIDS. New England Journal of Medicine 2003;349(24):2283‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Global Report 2007

- Global HIV Prevention Working Group. Bringing HIV Prevention to Scale: An Urgent Global Priority. Prevention Working Group. http://www.globalhivprevention.org/pdfs/PWG‐HIV_prevention_report_FINAL.pdf (Accessed Dec 2009). Prevention Working Group, 2007:8‐9. [Google Scholar]

Guyana 2005

- Guyana Ministry of Health. PMTCT Implementation. Personal communication 2005.

Higgins 2005

- Higgins JPT, Green S, Editors. Cochrane handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.5 [updated may 2005]. www.cochrane.org/resources/handbook/hbook.htm. John Wiley & Sons, LTD, (accessed 31 May 2005); Vol. In The Cochrane Library, issue 3.

Kaiser 2005

- Kaiser Family Foundation. HIV testing in the United States. Kaiser Family Foundation Fact Sheet http://www.kff.org/hivaids/loader.cfm (accessed 19‐09‐06) 2005.

Kamya 2007

- Kamya MR, Wanyenze R, Namale A. Routine HIV testing: the right not to know versus the rights to care, treatment and prevention. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2007;85:5. [Google Scholar]

Liechty 2004

- Liechty CA. The evolving role of HIV counseling and testing in resource‐limited settings: HIV prevention and linkage to expanding HIV care access. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2004;1(4):181‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Matovu 2002

- Matovu JK, Kigozi G, Nalugoda F, Wabwire‐Mangeni F, Gray RH. The Rakai project counseling program experience. Tropical Medicine and International Health 2002;7:1064‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mermin 2005

- Mermin J. A Family‐Based Approach to Preventive Care and Antiretroviral Therapy in Africa. 12th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Boston http://www.retroconference.org/Search_Abstract_2005/Default.aspx (accessed 19‐09‐06). 2005.

MOH‐Uganda 2005

- MOH‐Uganda. Uganda National Policy Guidelines for HIV Counseling and Testing, 2005. http://www.aidsuganda.org/sero/HCT%20policy.pdf (Accessed August 2007) 2005.

Morin 2006

- Morin SF, Khumalo‐Sakutikwa G, Charlebois ED. Removing barriers to knowing HIV status. Same‐day Mobile HIV testing in Zimbabwe. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 2006;41(2):218‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Murana 2005

- Murana E, Okello BN. High uptake of Voluntary Counseling and Testing (VCT) services using the mobile and home‐to‐home (M&H‐H) approaches in 2 two districts in eastern Uganda, through the AIDS Information Centre (AIC). International AIDS Society (IAS) Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment , Rio de Janeiro July 24‐27, 2005. 2005; Vol. 3rd: Abstract No. TuPp0204, issue TuPp0204.

Nakchbandi 1998

- Nakchbandi IA, Longenecker JC, Ricksecker MA, Latta RA, Healton C, Smith DG. A decision analysis of mandatory compared with voluntary HIV testing in pregnant women. Annals of Internal Medicine 1998;128(9):760‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Prabhat 2002

- Prabhat Jha, Anne Mills, Kara Hanson, Lilani Kumaranayake, Lesong Conteh, Christoph Kurowski, et al. Improving the health of the global poor. Science 2002;295:2036‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2003 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (REVMan). Version 4.2 for Windows. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2003.

Summers 2000

- Summers T, Spielberg F, Collins C, Coates T. Voluntary counseling and testing and referral for HIV: new technologies, research findings create dynamic opportunities. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 2000;25(Suppl 2):128‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

TASO 2005

- The AIDS Support Organisation. Home Based Testing at TASO Jinja Uganda. TASO Uganda Photo Archive 2005.

UBOS 2001

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics and ORC/Macro International Inc. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2000‐2001. Entebbe and Colverton, MD: UBOS and Macro International 2001.

UNAIDS 2004

- UNAIDS. UNAIDS/WHO Policy Statement on HIV Testing. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/vct/en/hivtestingpolicy04.pdf (Accessed August 2007) 2004.

UNAIDS 2008

- UNAIDS. The Report on the Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic 2008. http://www.unaids.org/en/HIV_data/2008GlobalReport/default.asp (accessed 15 June 2010).

UNDP 2006

- UNDP. The Human Development Indices. United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report. http://hdr.undp.org/hdr2006/statistics/documents/hdi2004.pdf 2006.

VCT Efficacy 2000

- Voluntary HIV‐1 Counseling and Testing Efficacy Study Group 2000. Efficacy of voluntary HIV‐1 counseling and testing in individuals and couple in Kenya, Tanzania, and Trinidad. A randomised trial. Lancet 2000;356:103‐12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wanyenze 2004

- Wanyenze R, Kamya M, Liechty C, Guzman D, Ronald A, Wabwirw‐Mangeni. HIV testing practices in Mulago Hospital. www.retroconference.org/2004/cd/PDFs/578.pdf (accessed 12/09/06). 2004; Vol. V‐12.

Weiser 2006

- Weiser S, Heisler M, Leiter K, Korte F, Tlou S, DeMonner S, Phaladze N, Bangsberg D, Iacopino V. Routine HIV Testing in Botswana: A Population‐Based Study on Attitudes, Practices, and Human Rights Concerns.. PLoS Medicine July 18, 2006; Vol. 3, issue 7:1013‐22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Were 2003

- Were W, Mermin J, Bunnel R, Ekwaru JP, Kaharuza F. Home‐based model for HIV voluntary counseling and testing. Lancet 2003;361(9368):1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Were 2006

- Were WA, Mermin JH, Wamai N, Awor AC, Bechange S, Moss S, et. Al. Undiagnosed HIV infection and couple HIV discordance among household members of HIV‐Infected people receiving antiretroviral therapy. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 2006;43(1):1‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WHO 2005

- WHO. Lesotho launches groundbreaking HIV campaign on World AIDS Day. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2005/pr64/en/index.html (accessed 10/09/06) Vol. 2005.

WHO 2007

- WHO. Guidance on provider‐initiated HIV testing and counselling in health facilities. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241595568_eng.pdf (Accessed August 2007) 2007; Vol. NA:6‐8.

Wolff 2005

- Wolff B, Nyanzi B, Katongole, Ssesanga D, Ruberantwari A, Whitworth J. Evaluation of a home‐based voluntary counseling and testing intervention in rural Uganda. Health Policy and Planning 2005;20(2):109‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]