Abstract

Background

Fulvestrant is a selective oestrogen receptor down‐regulator (SERD), which by blocking proliferation of breast cancer cells, is an effective endocrine treatment for women with hormone‐sensitive advanced breast cancer. The goal of such systemic therapy in this setting is to reduce symptoms, improve quality of life, and increase survival time.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of fulvestrant for hormone‐sensitive locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer in postmenopausal women, as compared to other standard endocrine agents.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Breast Cancer Specialised Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP), and ClinicalTrials.gov on 7 July 2015. We also searched major conference proceedings (American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium) and practice guidelines from major oncology groups (ASCO, European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and Cancer Care Ontario). We handsearched reference lists from relevant studies.

Selection criteria

We included for analyses randomised controlled trials that enrolled postmenopausal women with hormone‐sensitive advanced breast cancer (TNM classifications: stages IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC) or metastatic breast cancer (TNM classification: stage IV) with an intervention group treated with fulvestrant with or without other standard anticancer therapy.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data from trials identified in the searches, conducted 'Risk of bias' assessments of the included studies, and assessed the overall quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach. Outcome data extracted from these trials for our analyses and review included progression‐free survival (PFS) or time to progression (TTP) or time to treatment failure, overall survival, clinical benefit rate, toxicity, and quality of life. We used the fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis where possible.

Main results

We included nine studies randomising 4514 women for meta‐analysis and review. Overall results for the primary endpoint of PFS indicated that women receiving fulvestrant did at least as well as the control groups (hazard ratio (HR) 0.95, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.89 to 1.02; P = 0.18, I2= 56%, 4258 women, 9 studies, high‐quality evidence). In the one high‐quality study that tested fulvestrant at the currently approved and now standard dose of 500 mg against anastrozole, women treated with fulvestrant 500 mg did better than anastrozole, with a HR for TTP of 0.66 (95% CI 0.47 to 0.93; 205 women) and a HR for overall survival of 0.70 (95% CI 0.50 to 0.98; 205 women). There was no difference in PFS whether fulvestrant was used in combination with another endocrine therapy or in the first‐ or second‐line setting, when compared to control treatments: for monotherapy HR 0.97 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.04) versus HR 0.87 (95% CI 0.77 to 0.99) for combination therapy when compared to control, and HR 0.93 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.03) in the first‐line setting and HR 0.96 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.04) in the second‐line setting.

Overall, there was no difference between fulvestrant and control treatments in clinical benefit rate (risk ratio (RR) 1.03, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.10; P = 0.29, I2 = 24%, 4105 women, 9 studies, high‐quality evidence) or overall survival (HR 0.97, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.09, P = 0.62, I2 = 66%, 2480 women, 5 studies, high‐quality evidence). There was no significant difference in vasomotor toxicity (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.18, 3544 women, 8 studies, high‐quality evidence), arthralgia (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.09, 3244 women, 7 studies, high‐quality evidence), and gynaecological toxicities (RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.57, 2848 women, 6 studies, high‐quality evidence). Four studies reported quality of life, none of which reported a difference between the fulvestrant and control arms, though specific data were not presented.

Authors' conclusions

For postmenopausal women with advanced hormone‐sensitive breast cancer, fulvestrant is at least as effective and safe as the comparator endocrine therapies in the included studies. However, fulvestrant may be potentially more effective than current therapies when given at 500 mg, though this higher dosage was used in only one of the nine studies included in the review. We saw no advantage with combination therapy, and fulvestrant was equally as effective as control therapies in both the first‐ and second‐line setting. Our review demonstrates that fulvestrant is a safe and effective systemic therapy and can be considered as a valid option in the sequence of treatments for postmenopausal women with hormone‐sensitive advanced breast cancer.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Anastrozole; Antineoplastic Agents, Hormonal; Antineoplastic Agents, Hormonal/adverse effects; Antineoplastic Agents, Hormonal/therapeutic use; Breast Neoplasms; Breast Neoplasms/drug therapy; Breast Neoplasms/mortality; Breast Neoplasms/pathology; Disease-Free Survival; Estradiol; Estradiol/adverse effects; Estradiol/analogs & derivatives; Estradiol/therapeutic use; Fulvestrant; Neoplasms, Hormone-Dependent; Neoplasms, Hormone-Dependent/drug therapy; Nitriles; Nitriles/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Triazoles; Triazoles/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Fulvestrant in the treatment of postmenopausal women with advanced hormone‐sensitive breast cancer

Review question

We reviewed the evidence concerning the effectiveness and safety of fulvestrant in prolonging time without further progression of cancer in women with advanced hormone‐sensitive breast cancer. We found nine studies testing whether or not fulvestrant is superior to other treatment options.

Background

Seventy percent of breast cancers are sensitive to hormones, and there are a variety of endocrine therapies that lower or block female hormones to treat these cancers. Fulvestrant is one such endocrine therapy that can be used to treat hormone‐sensitive breast cancers by blocking oestrogen. It is administered by monthly injection for women with advanced disease. The definition of advanced disease is when the primary cancer in the breast has either spread to heavily involve the lymph nodes or grown to a considerably large size (stage III) or when the cancer has spread beyond the breast and the lymph nodes to other tissues or organs, or both (stage IV). The goal of treatment in these settings is to improve quality of life, reduce symptoms caused by the cancer, and extend length of life. It is noteworthy that the studies examined in this review predominantly used a lower dose of fulvestrant (250 mg) as compared to the now standard, more effective, and approved dose of 500 mg.

Study characteristics

The evidence is current to 7 July 2015. Our review identified nine clinical trials that compared the effectiveness and safety of fulvestrant against other standard treatments for advanced hormone‐sensitive breast cancer and pooled the data from these trials to analyse all the data together. Three different endocrine therapies were analysed as comparator drugs against fulvestrant. Two of these drugs were the aromatase inhibitors anastrozole and exemestane, which lower oestrogen levels in postmenopausal women, and the third was tamoxifen, which works by blocking oestrogen. Four of the studies were in the first‐line setting, meaning that fulvestrant was tested against these endocrine therapies as the initial treatment for advanced disease. Five of the studies tested fulvestrant in the second‐line or more setting, meaning after the women had progressed on a prior initial treatment for advanced disease. Two studies examined fulvestrant in combination with anastrozole against anastrozole alone, and the other seven studies compared fulvestrant alone with other comparator drugs.

Key results

We found that fulvestrant was at least as effective as the other three standard endocrine therapies used in the treatment of advanced hormone‐sensitive breast cancer and is possibly more effective at the new standard dose of 500 mg, rather than the lower dose of 250 mg, which was previously used and tested in all but one of the included studies. We also found that combining fulvestrant with an aromatase inhibitor did not improve effectiveness, and neither was effectiveness influenced by whether fulvestrant was used as the first treatment upon diagnosis of advanced disease or after another endocrine therapy. This was evident in the pooled data analysis for both survival time without progression of cancer and the rate of tumour shrinkage or stabilisation due to fulvestrant as compared with the other endocrine therapies. In addition, fulvestrant‐treated women did not experience worse side effects than those receiving the comparator endocrine therapies, and quality of life was equivalent in both fulvestrant‐treated women and women treated with the other endocrine therapies.

Fulvestrant can therefore be considered an effective and safe treatment for postmenopausal women with advanced hormone‐sensitive breast cancer, when treatment with endocrine therapy is indicated.

Quality of the evidence

All studies were of high quality.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Fulvestrant versus other endocrine treatment.

| Fulvestrant versus any other endocrine therapy for hormone‐sensitive advanced breast cancer | ||||||

| Patient or population: women with hormone‐sensitive advanced breast cancer Setting: cancer centre Intervention: fulvestrant Comparison: any other standard endocrine therapy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with any other standard endocrine therapy | Risk with fulvestrant | |||||

| Time to progression follow‐up: range 8.9 months to 38 months | Low‐risk population | HR 0.95 (0.89 to 1.02) | 4258 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2,3,4 | ||

| 500 events per 10001 | 482 events per 1000 (460 to 507) | |||||

| High‐risk population | ||||||

| 600 events per 10001 | 581 events per 1000 (558 to 607) | |||||

| Clinical benefit rate follow‐up: range 8.9 months to 38 months | Study population | RR 1.03 (0.97 to 1.10) | 4105 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH 3 | ||

| 486 per 1000 | 501 per 1000 (471 to 535) | |||||

| Mortality follow‐up for overall survival: range 8.9 months to 38 months | Low‐risk population | HR 0.97 (0.87 to 1.09) | 2480 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH 2,3 | ||

| 350 deaths per 10005 | 342 deaths per 1000 (313 to 375) | |||||

| High‐risk population | ||||||

| 400 deaths per 10005 | 391 deaths per 1000 (359 to 427) | |||||

| Vasomotor toxicity follow‐up: range 8.9 months to 38 months | Study population | RR 1.02 (0.89 to 1.18) | 3544 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH 2 | ||

| 170 per 1000 | 174 per 1000 (151 to 201) | |||||

| Arthralgia follow‐up: range 8.9 months to 38 months | Study population | RR 0.96 (0.86 to 1.09) | 3244 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH 2 | ||

| 225 per 1000 | 216 per 1000 (193 to 245) | |||||

| Gynaecological toxicity follow‐up: range 8.9 months to 38 months | Study population | RR 1.22 (0.94 to 1.57) | 2848 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH 4 6 | ||

| 68 per 1000 | 83 per 1000 (64 to 107) | |||||

| Quality of life assessed with: FACT‐B or FACT‐ES questionnaire follow‐up: range 8.9 months to 38 months | None of the studies reported a difference in quality of life between women receiving fulvestrant and other endocrine treatments | ‐ | (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; FACT‐B: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐Breast; FACT‐ES: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐Endocrine Symptoms; HR: hazard ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1The baseline risk for the control groups was calculated at 12 months for those women at relatively low risk (first‐line treatment) and at 6 months for those women at high risk (after first‐line treatment). 2Although heterogeneity was detected (I2 ranged from 55% to 66%), this can be explained by the different doses of fulvestrant (250 mg and 500mg), different comparator drugs, and different lines of treatment. 3Less than 80% of women in both arms in one study, Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004, had oestrogen receptor ‐positive tumours. 4Eight of the nine studies investigated fulvestrant 250 mg rather than the standard 500 mg dose, the latter which has been demonstrated to be superior in a randomised trial (CONFIRM: Di Leo 2010; Di Leo 2012). 5The baseline risk for the control groups was calculated at 24 months for those women at relatively low risk (first‐line treatment) and at 12 months for those women at high risk (after first‐line treatment). 6The agent used in the control arm varied across studies; the nature of gynaecological toxicity associated with tamoxifen can differ from that with the aromatase inhibitors.

Background

Description of the condition

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer for women worldwide (Ferlay 2010). Some women present with metastatic disease (that is disease that has spread beyond the breast and lymph nodes) at diagnosis, while some women will go on to develop metastatic disease despite improvements in adjuvant therapies.

Palliative treatments are available where the goal of therapy is to relieve symptoms, improve quality of life, and prolong survival. The systemic treatment options for women with metastatic breast cancer include cytotoxic chemotherapies and, for women with oestrogen receptor (ER)‐ or progesterone receptor (PgR)‐positive tumours, endocrine therapy is an important therapeutic option. Treatment decisions are based upon a number of factors, including the tumour characteristics (oestrogen and progesterone receptor status, HER2/neu receptor status), patient factors, and the extent and rapidity of disease progression.

The goal of endocrine therapy is to block oestrogen‐induced proliferation of breast cancer cells. In postmenopausal women, three broad classes of endocrine therapy are used clinically to treat hormone‐responsive breast cancer. First, selective oestrogen receptor modifiers (SERMs), such as tamoxifen, directly bind to the ER and are oestrogen receptor agonist‐antagonists (that is they activate the ER in some tissues and block the ER in other tissues). Second, aromatase inhibitors (AIs), such as letrozole, anastrozole, and exemestane, reduce the production of oestrogen through inhibition of the aromatase enzyme (which converts androgen to oestrogen) in peripheral tissues including bone, muscle, and adipose tissue, and within the tumour itself. Third, the newest class of agents are the selective oestrogen receptor down‐regulators (SERDs), such as fulvestrant, which bind to the ER and induce its degradation (Pietras 2006).

Seventy‐five per cent of breast cancers in postmenopausal women are hormone receptor‐positive (Bundred 2005). Among postmenopausal women with metastatic ER‐positive or PgR‐positive breast cancer, endocrine therapy may produce initial clinical benefit for greater than 80% of these patients (Buzdar 1998). The tolerability and effective anti‐tumour activity of endocrine therapies make these treatments the ideal first‐line choice for most women with metastatic hormone‐sensitive breast cancer. A response to previous endocrine therapies is often predictive of response to further endocrine manipulation in metastatic breast cancer. Despite initial sensitivity to sequential endocrine treatments, disease progression on these agents will ultimately occur for the majority of patients (Bundred 2005). In general, the length of clinical benefit shortens with each subsequent endocrine therapy, and then other treatments such as cytotoxic chemotherapy may be considered.

Description of the intervention

Fulvestrant is the only SERD in clinical use at present. Unlike other endocrine agents, which are provided as oral medication, fulvestrant is administered intramuscularly once per month, and requires an initial loading dose. Some reported adverse effects include nausea, pain, and headaches.

How the intervention might work

Fulvestrant competitively binds to and blocks the ER which accelerates the degradation of the ER protein. This leads to complete inhibition of oestrogen signalling through the oestrogen receptor (Wakeling 2000). Fulvestrant has no oestrogen‐agonist properties, and is considered to be a pure antagonist.

Why it is important to do this review

It is important to understand whether fulvestrant is equivalent to, better than, or inferior to standard hormonal therapies (tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors) as first‐ or second‐line treatment for locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer, in order to guide clinical practice.

Additional time on effective endocrine therapy may delay the need for cytotoxic chemotherapy. For women with hormone receptor‐positive metastatic or locally advanced breast cancer, assessing whether there is benefit of additional endocrine therapy or not has utility, and this will allow appropriate timing of other active treatments such as cytotoxic chemotherapy. Existing meta‐analyses have not included all available efficacy data and trial quality assessments (Al‐Mubarak 2013; Flemming 2009; Valachis 2010).

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of fulvestrant for hormone‐sensitive locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer in postmenopausal women, as compared to other standard endocrine agents.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials that met the inclusion criteria.

Types of participants

Postmenopausal women who had hormone‐sensitive breast cancer (ER‐positive or PgR‐positive, or both) and who were diagnosed with locally advanced breast cancer (TNM classifications: stages IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC) or metastatic breast cancer (TNM classification: stage IV).

We included trials where postmenopausal women was reasonably defined (acceptable definitions included more than 1 year since last menstruation, or tested as postmenopausal from oestradiol and follicle‐stimulating hormone levels based on the evaluation standards at each institution, or women who had undergone bilateral ovarian ablation).

Types of interventions

Intervention group: fulvestrant with or without other standard anticancer treatments (e.g. endocrine therapy or chemotherapy, or both).

Comparator 1: any standard endocrine agents (tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors) not containing fulvestrant.

Comparator 2: any other anticancer treatment (e.g. chemotherapy).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Progression‐free survival (PFS), defined as time between randomisation and tumour progression, or death from any cause. If PFS was not reported, we included time to progression (TTP), defined as the period from randomisation to time of progression, or time to treatment failure (TTF), defined as time to progression, relapse, or death from any cause in this analysis.

Secondary outcomes

Overall survival (OS): defined as the time from date randomised to date of death from any cause.

Clinical benefit rate: defined as the proportion of women with an objective response or a best overall tumour assessment of stable disease (stable disease: less than 50% decrease and less than 25% increase with the appearance of no new lesions) for 24 or more weeks.

Quality of life: defined as an expression of well‐being and measured using a validated scale (e.g. 36‐Item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36), European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT)).

Tolerability: toxicity and tolerability of therapy were included, as recorded by adverse events (as graded by National Cancer Institute (NCI) Toxicity Criteria).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases on the 7 July 2015.

The Cochrane Breast Cancer Specialised Register. Details of search strategies used by the Cochrane Breast Cancer Group (CBCG) for the identification of studies and the procedures used to code references are outlined in the CBCG's module at www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clabout/articles/BREASTCA/frame.html. Trials with the key or text words "fulvestrant, Faslodex, advanced breast cancer, metastatic breast cancer, locally advanced breast cancer, selective oestrogen receptor down‐regulator" were extracted and considered for inclusion in the review.

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (via the Cochrane Library, Issue 6, 2015). See Appendix 1.

MEDLINE (via OvidSP) from 2008 to 7 July 2015. See Appendix 2.

EMBASE (via EMBASE.com) 2008 to 7 July 2015. See Appendix 3.

The World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx) for all prospectively registered and ongoing trials. See Appendix 4.

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/). See Appendix 5.

We did not impose any restriction on language.

Searching other resources

We searched conference proceedings of the meetings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) (2003 to 2013, www.asco.org) and the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (2005 to 2013, www.sabcs.org) for relevant abstracts.

If available, we included clinical practice guidelines from major oncology groups (ASCO, European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and Cancer Care Ontario) in the discussion.

We performed a directed search for published guidelines of endocrine treatment for metastatic breast cancer by searching the Canadian Medical Association Infobase (www.cma.ca/En/Pages/clinical‐practice‐guidelines.aspx), the National Guideline Clearinghouse (www.guideline.gov), the National Health and Medical Research Council Australia (www.nhmrc.gov.au/) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (www.nice.org.uk).

We handsearched references from relevant studies and consulted experts to ensure completeness of the search.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (CL and NW) independently reviewed all abstracts and potentially eligible full‐text articles using the aforementioned inclusion criteria. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus after discussion. We recorded excluded studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We included articles published in any language, and translated articles when required.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (CL and NW) independently extracted data from the included studies using standard data extraction forms. We collected information on study design, participants, setting, interventions, follow‐up, and funding sources. Any discrepancies regarding the extraction of quantitative data were resolved after discussion.

For studies with more than one publication, we extracted outcome data from the most up‐to‐date version of the study and listed the final or updated version of each study as the primary reference.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (CL and NW) judged and graded each selected study using The Cochrane Collaboration's 'Risk of bias' assessment tool as outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Grades given by each review author were compared and any disagreements resolved by discussion. The tool contains seven domains, and we assigned each domain a judgement related to the risk of bias. A judgement of 'low' indicated a low risk of bias, 'high' indicated a high risk of bias, and 'unclear' indicated an unclear or unknown risk of bias. The seven domains were:

sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding of participants, personnel;

blinding of outcome assessment;

incomplete outcome data;

selective outcome reporting (we cross‐checked trial protocols and trial result publications); and

other sources of bias.

We reported the judgements of these domains for each trial in the 'Risk of bias' table.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (for example clinical benefit, toxicities), we expressed the treatment effect as a risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). We identified gynaecological, arthralgia, and vasomotor toxicities as the three most common toxicities associated with endocrine therapies and assessed these toxicities.

We did not need to meta‐analyse continuous outcomes (for example quality of life) in this review, however should we need to do so in future updates, we will express the treatment effect as the mean difference (MD) or the standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales have been used.

For time‐to‐event outcomes (for example progression‐free survival, overall survival, time to progression), we expressed the treatment effect as a hazard ratio (HR). Where possible, we extracted the HR and associated variances directly from the trial publications. In future updates of this review, if we cannot obtain the HR and associated variances directly from the trial publication, we will obtain these data indirectly using the methods described by Tierney et al by employing other available summary statistics or data extracted from published Kaplan‐Meier curves (Tierney 2007).

Unit of analysis issues

There were no unit of analysis issues.

Dealing with missing data

There were no missing data. In future review updates where data are missing, we will contact the original investigators (by written correspondence) to request missing data. If we cannot obtain significant missing data, we may perform a sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity by using the Chi2 test and the I2 statistic (Cochran 1954; Higgins 2003), as well as visual inspection of forest plots.

For the Chi2 test, we used a P value of 0.10 rather than the conventional value of 0.05 to determine the statistical significance. The I2 statistic indicated the percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance; we considered that an I2 value of 30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity, 50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity, and 75% to 100% as considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2011). We evaluated the value of the I2 statistic alongside the magnitude and direction of effects and the P value for the Chi2 test for heterogeneity (Higgins 2011).

As there was no statistical evidence of heterogeneity in the majority of the studies analysed in this review, we used the fixed‐effect model. When there was moderate heterogeneity (in assessment of overall survival, and vasomotor, arthralgia and gynaecological toxicity), we used the random‐effects model and explored sources of heterogeneity, however we ultimately used a fixed‐effect model for these given that the conclusions were the same based on the fixed‐effect and random‐effects analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not conduct a test for funnel plot asymmetry as we had fewer than 10 studies. In future review updates, we will follow the recommendations on testing for funnel plot asymmetry as described in Section 10.4.3.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

For dichotomous outcome variables, we used a fixed‐effect (Mantel‐Haenszel method) analysis, and a random‐effects method when we found moderate heterogeneity (DerSimonian and Laird method).

For continuous outcome variables, we conducted a fixed‐effect (inverse‐variance method) analysis. If we deemed random‐effects analysis to be appropriate, we employed the inverse‐variance method together with the DerSimonian and Laird method.

For time‐to‐event variables, we conducted a fixed‐effect (inverse‐variance method) analysis, if appropriate. If we observed moderate heterogeneity, we employed a random‐effects (inverse‐variance and DerSimonian and Laird method) analysis.

We performed all analyses using Review Manager software (RevMan 2012), in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

We described the quality of the available evidence in 'Summary of findings' tables in line with recommendations from Section 11.5 of the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011). We used GRADEproGDT to develop the tables (GRADEproGDT). In the 'Summary of findings' table we renamed 'overall survival' as 'mortality' for clarity.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We undertook the following analyses, except for analysis (3) 'additional lines of therapy', which did not apply to our selected studies. We included any studies that met our selection criteria and tested fulvestrant as below.

First‐line therapy.

Second‐line therapy.

Additional lines of therapy.

Dose of fulvestrant.

Single‐agent fulvestrant compared to combination therapy as the intervention arm.

Sensitivity analysis

We judged most of the studies to be at low risk of bias for each 'Risk of bias' domain. In future reviews, we will conduct a sensitivity analysis of low versus high/unclear risk of bias. We will assign studies with more than four out of seven domains with an unclear/high risk of bias an overall 'Risk of bias' assessment of unclear/high risk.

In our review we pooled data irrespective of the progression‐free survival (PFS) definition adopted, and conducted a sensitivity analysis of studies that defined PFS as per our protocol definition versus any other definition. The sensitivity analysis did not change the results.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We identified 1315 records from database searching and 171 from other sources, with 1333 resultant records after de‐duplication (see Figure 1). After screening the 1333 records by title and abstract, we excluded 1301 records from the review and assessed 32 full‐text records for eligibility. Of these 32 full‐text records, we excluded three articles, as two reports of one study pertained to gefitinib (a non‐standard treatment for breast cancer), and one other study was a single‐arm, non‐comparative study (see Characteristics of excluded studies). Of the remaining 29 records, 28 records related to nine included studies (EFECT; FACT; FIRST; Howell, Fulvestrant vs Anastrozole 2002; Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004; Mehta 2012; Osborne 2002; SoFEA; Xu 2011), which we included for qualitative synthesis and meta‐analysis, and one ongoing study (NCT01602380).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Design

Across nine studies 4514 women were enrolled and included in the analyses overall. Breakdown of the women accrued per trial was: EFECT, 693; FACT, 514; FIRST, 205; Howell, Fulvestrant vs Anastrozole 2002, 451; Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004, 587; Mehta 2012, 707; Osborne 2002, 400; SoFEA, 723; Xu 2011, 234.

Accrual centres and periods for each of the studies were: EFECT: 138 centres worldwide between August 2003 to November 2005; FACT: across 77 centres in 11 countries between January 2004 to March 2008; FIRST: across 62 centres in nine countries; Howell, Fulvestrant vs Anastrozole 2002: across 62 centres in nine countries (accrual period not reported); Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004; across 171 centres in 26 countries and recruitment took place between November 1998 and June 2000; Mehta 2012: between June 2004 and July 2009 with no reporting of accrual sites; Osborne 2002: in North America and did not report accrual time period; SoFEA: across 82 UK centres and four South Korean centres between March 2004 and August 2010; and Xu 2011: across 19 centres between November 2005 and September 2007, with the women being accrued solely in China.

Participants

All participants included in the review were postmenopausal women with hormone‐sensitive breast cancer (although in one study, Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004, only about 80% of the women had proven hormone‐sensitive disease). The median age ranged from 54 to 67 years. All women had advanced breast cancer, locally advanced or metastatic disease with either bone only or visceral metastases, and some with both. Four studies included only those who had relapsed in the first instance and were naïve to treatment in the metastatic setting (FACT; FIRST; Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004; Mehta 2012). Five studies enrolled women who had received prior treatment for metastatic disease (EFECT; Howell, Fulvestrant vs Anastrozole 2002; Osborne 2002; SoFEA; Xu 2011).

Interventions

All nine included studies compared fulvestrant as the intervention against an established standard breast cancer treatment, that is the aromatase inhibitors anastrozole (non‐steroidal) and exemestane (steroidal), and the selective oestrogen receptor modulator tamoxifen. In two studies, FACT and Mehta 2012, the intervention was a combination therapy with fulvestrant plus aromatase inhibitor (anastrozole) versus anastrozole alone. All studies except one tested fulvestrant at the 250 mg dose level; FIRST was the only study to dose fulvestrant at the now‐approved current and standard dosing of 500 mg intramuscular injections monthly (CONFIRM: Di Leo 2010; Di Leo 2012). As a result of these trials, the more appropriate dose of fulvestrant is now acknowledged as 500 mg. Additionally, some studies dosed fulvestrant with loading regimens in the initial month of trial treatment (EFECT; FACT; FIRST; Mehta 2012; SoFEA), but the review authors decided that this would not confound the data included in the analyses. See Characteristics of included studies tables for further description of the individual studies.

Co‐interventions

Bisphosphonates were allowed, provided women had commenced prior to entry to the trial in Howell, Fulvestrant vs Anastrozole 2002, Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004, and Osborne 2002. Initiation of bisphosphonates was not allowed during the trials.

Outcomes

Time to progression (EFECT; FACT; Howell, Fulvestrant vs Anastrozole 2002; Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004; Osborne 2002; Xu 2011) or progression‐free survival (Mehta 2012; SoFEA) were the primary outcomes for eight of nine studies and was reported as a secondary outcome in the FIRST study.

Clinical benefit rate was the primary outcome of the FIRST study. The other eight studies all reported clinical benefit rate data as a secondary outcome.

Five studies reported overall survival data as a secondary outcome (FACT; FIRST; Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004; Mehta 2012; SoFEA).

Excluded studies

We excluded three studies (Carlson 2009; Carlson 2012; Perey 2007); see Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

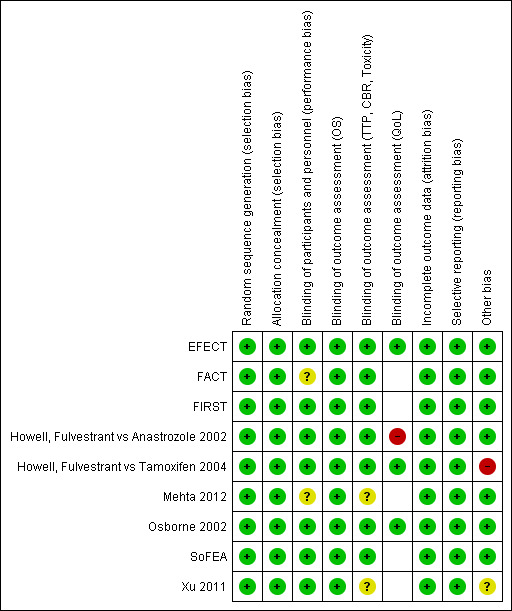

See Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

We considered all nine studies to be adequate in allocation of designated study drug, and hence results were unlikely to be influenced by selection bias. In particular, FACT, Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004, and SoFEA described computer‐generated randomisation for allocation of study treatments for women enrolled in the trial. In Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004, the "apparent imbalance in the number of patients randomly assigned to the two treatment groups arose purely by chance because each center randomly assigned patients to treatment by blocks of four, and in many cases, these blocks were incomplete due to limited patient numbers at each center” (page 1608). Trials reported by EFECT, Osborne 2002, and Xu 2011 were explicitly described as randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled studies, although the specific methods by which randomisation and allocation were performed were not detailed. In the remaining studies, FIRST, Howell, Fulvestrant vs Anastrozole 2002, and Mehta 2012, women were said to be randomised, although the logistical details were not outlined. This is not unusual in modern international cancer trial reports and does not signify any lack of quality. Overall, the participant population characteristics in all studies were well matched, indicating adequate randomisation. Our overall assessment was that although some of the studies did not report the details of allocation, selection bias was unlikely to be relevant in these rigorously conducted, randomised clinical trials.

Blinding

Of the nine studies, four were double blind and therefore at low risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel and most outcome assessments (EFECT; Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004; Osborne 2002; Xu 2011). FIRST described blinding of investigators to scans despite this not being a blinded study, and therefore was also considered to be at low risk of bias. Similarly, we considered Howell, Fulvestrant vs Anastrozole 2002 to be at low risk of bias despite not being a blinded study, as the way participants were monitored during the course of the study was described in exactly the same way in each intervention arm. However, for patient‐reported QoL measures, the study was considered to be at high risk of bias. Although FACT was an open‐label (unblinded) study and SoFEA was a partially blinded study, we deemed the conduct of these studies to minimise the risk of bias and classified them as at low for risk of bias for outcome assessment of progression‐free survival, clinical benefit rate, and toxicity. FACT and Mehta 2012 were judged to be at unclear risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel. Four of the nine studies reported quality‐of‐life results but not the data (EFECT; Howell, Fulvestrant vs Anastrozole 2002; Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004; Osborne 2002) and three of these studies were judged to be at low risk of bias (EFECT; Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004; Osborne 2002). All studies used Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐Breast (FACT‐B) to measure quality of life, except for EFECT, which used Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐Endocrine Symptoms (FACT‐ES) to measure quality of life.

Incomplete outcome data

There was no reason to believe that attrition bias was a significant factor in any of the nine included studies, as each study had similar attrition rates (being small) across intervention and control. In no study was there sufficient rate of attrition to constitute a high risk of bias.

Selective reporting

All of the outcomes reported in the methods sections were reported in the results.

Other potential sources of bias

We identified no other potentially serious sources of bias. Less than 80% of women in both arms of Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004 were oestrogen receptor positive. Other than this effect‐modifying factor, all prespecified outcomes in the methods were reported in the results section of the trial publications. The number of women in each treatment group was different in Xu 2011 but in general, baseline characteristics were comparable between the two groups.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

The effects of the intervention for time‐to‐event outcomes, that is progression‐free survival and overall survival, were reported as hazard ratios (HRs) in study reports and extracted for meta‐analysis. In order to include all data that broadly measured time during which the women receiving the assigned treatment maintained disease control, we took 'progression‐free survival' to include progression‐free survival (PFS), time to progression (TTP), and time to treatment failure (TTF). We extracted clinical benefit rates (CBR) and toxicity data (determined and categorised by two review authors as the most relevant to the review: vasomotor, arthralgia, and gynaecological) as proportions with incidence divided by the sample size for each of the intervention and control groups.

For assessments of the overall quality of the evidence for each outcome, see Table 1.

Progression‐free survival/Time to progression

PFS was the primary endpoint for eight studies, with the exception of FIRST, in which the primary endpoint was CBR and the secondary endpoint was TTP. EFECT, FACT, FIRST, Howell, Fulvestrant vs Anastrozole 2002, Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004, Osborne 2002, and Xu 2011 measured TTP, and Mehta 2012 and SoFEA measured PFS.

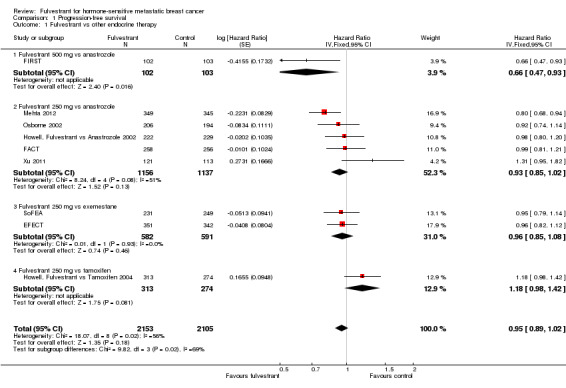

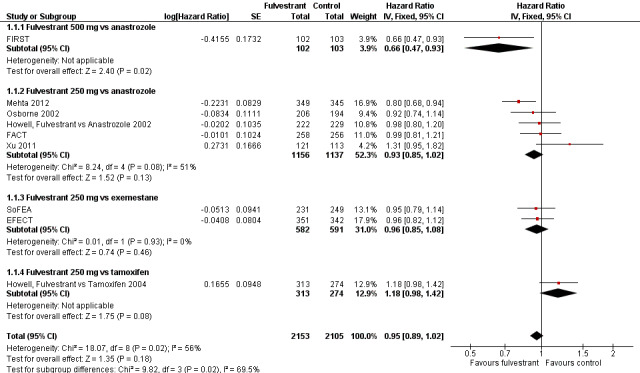

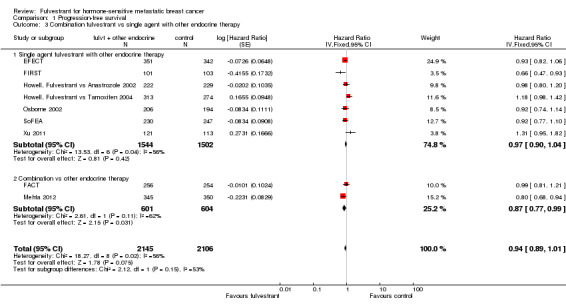

We found no difference in PFS with fulvestrant compared to control overall in the nine included studies (HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.02; 4258 women; 9 studies; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.1; Figure 3). There was moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 56%, P = 0.02). Of the 2153 women receiving fulvestrant, there were 1701 women whose disease progressed, and of the 2105 women receiving control, there were 1723 who progressed. In the one study that tested fulvestrant at the currently approved and now standard dose level of 500 mg against anastrozole, women treated with fulvestrant 500 mg did better than those receiving anastrozole, with a HR of 0.66 (95% CI 0.47 to 0.93; 205 women).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progression‐free survival, Outcome 1 Fulvestrant vs other endocrine therapy.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Progression‐free survival, outcome: 1.1 Fulvestrant vs other endocrine therapy.

A sensitivity analysis excluding SoFEA and Mehta 2012, which measured PFS instead of TTP (unlike the other seven studies) had a similar result (HR 1.00, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.08).

In the five studies comparing 250 mg fulvestrant versus anastrozole, the HR was 0.93 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.02; 2293 women; Analysis 1.1) with 903 events for 1156 women in the fulvestrant arm and 916 events for 1137 women in the control group. In two studies comparing 250 mg fulvestrant with exemestane, the HR was 0.96 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.08; 1173 women; Analysis 1.1) with 509 events for 582 women in the fulvestrant arm and 532 events for 591 women in the exemestane arm. When 250 mg fulvestrant was compared to tamoxifen in a single study, the HR was 1.18 (95% CI 0.98 to 1.42; 587 women; Analysis 1.1), with 226 of 313 women progressing in the fulvestrant arm and 196 of 274 women progressing in the tamoxifen arm.

When TTP was measured excluding the one study in which less than 80% of study participants were proven to have hormone‐sensitive breast cancer (Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004), the HR was 0.93 (95% CI 0.86 to 0.99; 3671 women; I2 = 43%). This is an indication of effect modification, as the effect of fulvestrant was lower than that for the other studies.

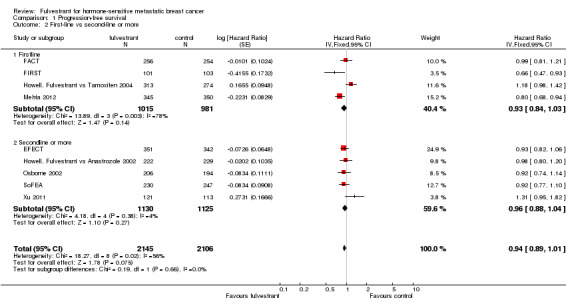

The relative activity of fulvestrant was the same whether tested as first‐line treatment (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.03; 1996 women; 4 studies; Analysis 1.2) or second‐line treatment (HR 0.96, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.04; 2255 women; 5 studies; Analysis 1.2). Similarly, the effect on PFS did not differ for fulvestrant used in combination with another endocrine agent (HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.99; 1205 women; 2 studies; Analysis 1.3) or as a single agent (HR 0.97, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.04; 3046 women; 7 studies; Analysis 1.3).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progression‐free survival, Outcome 2 First‐line vs second‐line or more.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progression‐free survival, Outcome 3 Combination fulvestrant vs single agent with other endocrine therapy.

Clinical benefit rate

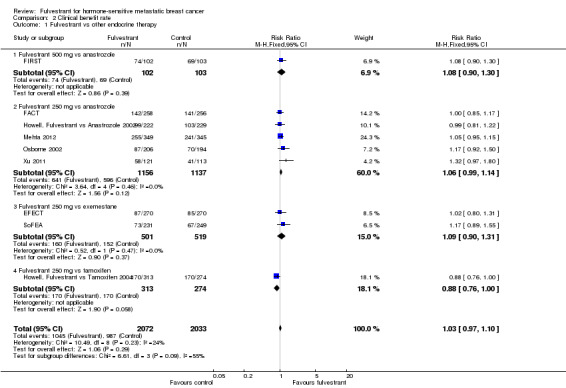

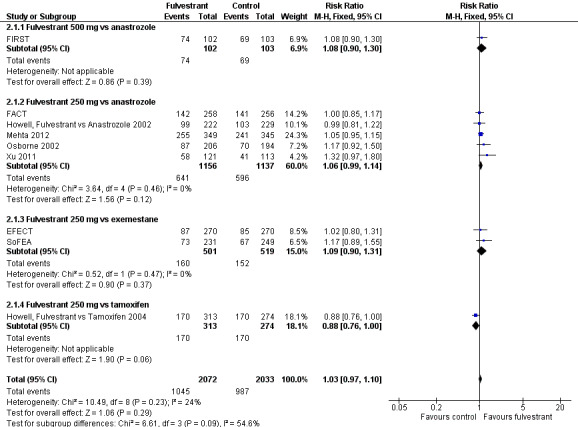

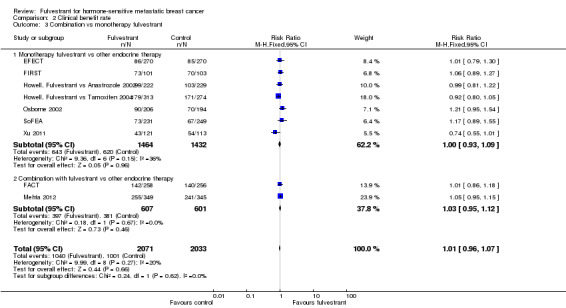

We could assess all nine studies for CBR and found no significant differences between fulvestrant and the comparators: RR 1.03 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.10; 4105 women; high‐quality evidence; Analysis 2.1; Figure 4) and no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 24%; P = 0.23). For the different comparators: there was one study of fulvestrant 500 mg versus anastrozole (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.30; 205 women; Analysis 2.1) and five studies of fulvestrant 250 mg versus anastrozole (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.14; 2293 women; Analysis 2.1). Two studies examined fulvestrant 250 mg versus exemestane (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.31; 1020 women; Analysis 2.1), and one study examined fulvestrant 250 mg versus tamoxifen (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.00; 587 women; Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Clinical benefit rate, Outcome 1 Fulvestrant vs other endocrine therapy.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Clinical benefit rate, outcome: 2.1 Fulvestrant vs other endocrine therapy.

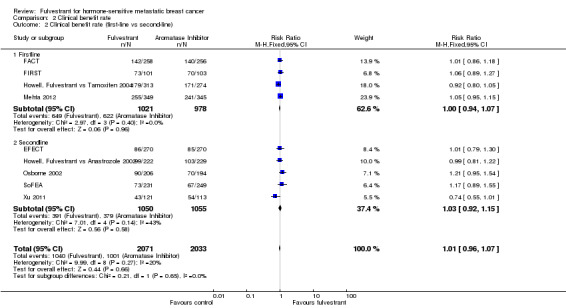

In the first‐line setting, there was no significant difference between fulvestrant and other endocrine therapy (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.07; 1999 women; 4 studies; Analysis 2.2). This was similar in the second‐line setting in which five studies were included (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.15; 2105 women; Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Clinical benefit rate, Outcome 2 Clinical benefit rate (first‐line vs second‐line).

There were two studies of fulvestrant combined with other endocrine therapy versus the other endocrine therapy alone (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.12; 1208 women; Analysis 2.3) and seven studies of single‐agent fulvestrant versus other endocrine therapy (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.09; 2896 women; Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Clinical benefit rate, Outcome 3 Combination vs monotherapy fulvestrant.

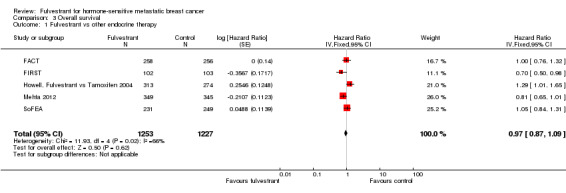

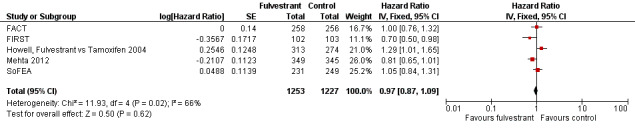

Overall survival

Five studies reported data concerning overall survival (HR 0.97, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.09; P = 0.62; 2480 women; I2 = 66%; high‐quality evidence; Analysis 3.1; Figure 5), with 636 deaths for the 1253 women treated with fulvestrant compared to 642 deaths for 1227 women in the control arms. Overall survival data for FIRST at the 500 mg dose of fulvestrant compared to anastrozole showed a benefit for the intervention over control (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.98; Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Overall survival, Outcome 1 Fulvestrant vs other endocrine therapy.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Overall survival, outcome: 3.1 Fulvestrant vs other endocrine therapy.

Toxicity

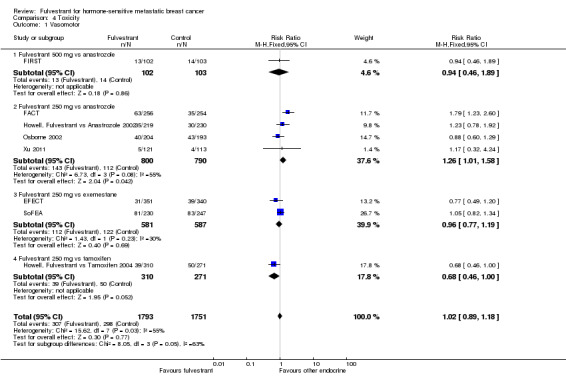

As there are various toxicities associated with fulvestrant and the different control treatments (both non‐steroidal and steroidal aromatase inhibitors and tamoxifen), we examined the three most common toxicities: vasomotor, arthralgia, and gynaecological toxicities. These toxicity data are summarised as RRs, such that an RR greater than 1.0 means toxicity is worse with fulvestrant. Although there was some variation between the individual trials in the three examined toxicities, overall summary statistics were not significantly different between fulvestrant and the comparator drugs.

Eight studies examined vasomotor toxicity (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.18; 3544 women; high‐quality evidence; Analysis 4.1). In FIRST, where the 500 mg dose of fulvestrant was used versus anastrozole in 205 women, the RR was 0.94 (95% CI 0.46 to 1.89; Analysis 4.1). Additionally, the RR for fulvestrant 250 mg versus anastrozole was 1.26 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.58; 1590 women; 4 studies; I2 = 55%; P = 0.03; Analysis 4.1), and the RR for fulvestrant 250 mg versus exemestane was 0.96 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.19; 1168 women; 2 studies; I2 = 30%; Analysis 4.1). In the study of fulvestrant 250 mg versus tamoxifen the RR was 0.68 (95% CI 0.46 to 1.00; 581 women; 1 study; Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Toxicity, Outcome 1 Vasomotor.

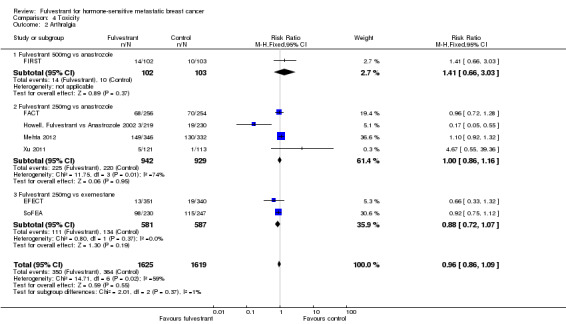

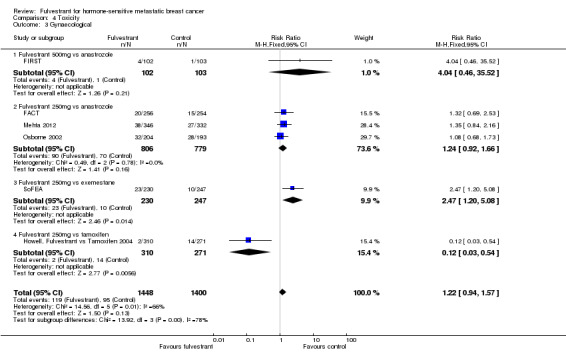

Seven studies examined arthralgia and found the incidence of anthralgia was comparable in the fulvestrant and control arms overall (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.09; 3244 women; I2 = 59%; P = 0.02; high‐quality evidence; Analysis 4.2). For fulvestrant 500 mg dose versus anastrozole the RR was 1.41 (95% CI 0.66 to 3.03; 205 women; Analysis 4.2), while for fulvestrant 250 mg dose versus anastrozole the RR was 1.00 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.16; 1871 women; 4 studies; Analysis 4.2). For fulvestrant 250 mg versus exemestane, two studies were examined and the pooled RR was 0.88 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.07; 1168 women; 2 studies; Analysis 4.2).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Toxicity, Outcome 2 Arthralgia.

Gynaecological toxicity included urinary tract infection, vulvovaginal dryness, vaginal haemorrhage, vaginitis, and pelvic pain. Overall, six studies reported gynaecological toxicity and no difference was observed between fulvestrant and control arms (RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.57; 2848 women; I2= 66%; P = 0.01; high‐quality evidence; Analysis 4.3). For the FIRST study, the RR for fulvestrant 500 mg versus anastrozole was 4.04 (95% CI 0.46 to 35.52; 205 women), whereas for fulvestrant 250 mg, the RRs were: fulvestrant 250 mg versus anastrozole RR 1.24 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.66; 1585 women; 3 studies; Analysis 4.3), fulvestrant 250 mg versus exemestane RR 2.47 (95% CI 1.20 to 5.08; 477 women; 1 study; Analysis 4.3), and fulvestrant 250 mg versus tamoxifen RR 0.12 (95% CI 0.03 to 0.54; 581 women; 1 study; Analysis 4.3).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Toxicity, Outcome 3 Gynaecological.

Quality of life

Four studies reported quality of life that was assessed with Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐Breast (FACT‐B) or Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐Endocrine Symptoms (FACT‐ES) questionnaires with follow‐up ranging from 8.9 months to 38 months. None of the studies reported a difference in quality of life as per their analyses between participants receiving fulvestrant and other endocrine treatments but numerical data were not presented.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The a priori primary endpoint for this review was PFS (encompassing TTP and TTF if reported). Our main finding was that when fulvestrant is compared with other endocrine agents as treatment for postmenopausal advanced hormone‐sensitive breast cancer, there is no statistically significant difference in PFS (HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.02; Figure 3). We observed similar findings for the clinical benefit rate and overall survival (Figure 4; Figure 5).

It is noteworthy that a randomised trial compared fulvestrant doses and found that the 500 mg dose was superior to the 250 mg dose for PFS (HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.94 ‐ CONFIRM trial (Di Leo 2010; Di Leo 2012)). Due to these findings, 500 mg is now the recommended dose. Of the nine studies included in this review, only a single trial used the 500 mg dose (FIRST), and a PFS benefit was reported for fulvestrant. It is thus possible, though not proven, that had the other eight studies tested the higher dose of fulvestrant, the findings of the review may have been different. A confirmatory trial of fulvestrant 500 mg versus 250 mg has finished accrual, and the results are eagerly awaited (NCT01602380).

The review also demonstrated that the relative efficacy of fulvestrant did not seem to vary whether it was used in combination with another endocrine agent or as a single agent, or whether it was used as first‐line or subsequent treatment.

It is interesting that the FIRST trial also reported an overall survival benefit for the higher dose of fulvestrant, although overall survival differences are in fact rarely seen in endocrine therapy trials, because most of these women go on to have multiple other treatments (more endocrine therapies as well as several chemotherapy agents), which distort any effect on overall survival. Lack of an overall survival benefit should therefore not be seen as a sign of lack of effect in endocrine therapy trials (or reviews).

The pooled toxicity data were prospectively divided into three categories based on clinical experience. Overall, fulvestrant was not significantly more toxic than other endocrine therapies, although a difference was found in two individual studies. For vasomotor toxicity, the RR was 1.02 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.18) across eight studies examining 3544 women (Analysis 4.1); for arthralgia, the RR was 0.96 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.09) across seven studies examining 3244 women (Analysis 4.2); and for gynaecological toxicity (which encompassed all reported toxicity of urogenital/gynaecological origin), the RR was 1.22 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.57) across six studies of high quality, which included 2848 women (Analysis 4.3).

Four studies reported quality‐of‐life data, and they did not find a difference in quality of life between the fulvestrant and control groups.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Clinical heterogeneity

Clinical heterogeneity was apparent in both the study participants and the interventions.

Women were treated in both the first‐line or second‐line or more settings for hormone‐sensitive metastatic breast cancer. However, this did not alter the outcomes of the analysis.

As mentioned previously, the Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004 study included more than 20% women whose breast cancers were not hormone sensitive.

With regard to the interventions tested, there was clinical heterogeneity between not only the dosing as described above, but also in the scheduling of fulvestrant, as some studies treated with loading doses and others did not. However, we judged that this was not likely to impact the outcomes. In two studies (FACT; Mehta 2012), the intervention was a combination of fulvestrant and anastrozole, which was compared to anastrozole alone. The other seven studies tested fulvestrant monotherapy as the intervention. Whether fulvestrant was used in combination therapy or monotherapy, we observed no differences in outcome between the studies.

Length of follow‐up

The median length of follow‐up varied across the studies, ranging from 8.9 months (range 0 to 54 months) for FACT, 13 months for EFECT, 18.8 months for fulvestrant and 12.9 months for anastrozole for FIRST, 21.3 months for Osborne 2002, 22.6 months for Howell, Fulvestrant vs Anastrozole 2002, 14.5 months for efficacy and safety and 31.1 months for survival for Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004, 37.9 months for SoFEA, 4 years for Mehta 2012, and Xu 2011 (unknown).

Quality of the evidence

The available evidence is sufficient for the review authors to make robust conclusions in assessing the efficacy and safety of fulvestrant for hormone‐sensitive locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer in postmenopausal women.

For the outcome TTP, we downgraded the risk of bias to moderate, as although I2 ranged from 55% to 66%, indicating heterogeneity, this could be accounted for by both the different dose levels of fulvestrant tested, different comparator drugs, combination fulvestrant versus fulvestrant monotherapy, and different lines of treatment. In addition, we noted that fewer than 80% of women in both arms in one study had oestrogen receptor‐positive tumours (Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004), and eight of the nine included studies investigated fulvestrant 250 mg rather than the standard 500 mg dose, which has been demonstrated to be superior to 250 mg dose in a randomised trial (CONFIRM: Di Leo 2010; Di Leo 2012).

For the outcome CBR, we did not downgrade the risk of bias, as heterogeneity was low (I2 = 24%), although I2 = 55% across subgroups defined by fulvestrant dose and comparator treatment indicates some heterogeneity in effect on CBR. Across all studies, the methods by which CBR were tested were consistent and without influence from bias.

For the outcome overall survival, the available data were of high quality and not influenced by bias.

Although we acknowledged that there is subjectivity in assessing and grading toxicity data, we concluded that this would not introduce bias in our results above and beyond what is acceptable for toxicity data collection, and therefore these data would be of high quality.

For the four studies that reported data on quality of life, we deemed that there would be little in the way of bias affecting these data given that quality of life was measured by validated instruments, and these data would hence would be of high quality.

Potential biases in the review process

There were no potential biases identified in the review process.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

There were four previous meta‐analyses and one systematic review pre‐dating our review.

Al‐Mubarak 2013 published a meta‐analysis in 2013 that examined eight of the nine trials included in our review except Xu 2011, finding no difference in TTP between fulvestrant and control groups (HR 0.94, P = 0.18), although in their analyses of toxicities they found less arthralgia in the fulvestrant group than in the control group.

Valachis 2010 published a meta‐analysis in 2009 examining four trials that tested fulvestrant at 250 mg, which were also included in our review (EFECT; Howell, Fulvestrant vs Anastrozole 2002; Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004; Osborne 2002), with a total of 2125 women. Valachis et al found no difference between fulvestrant and other hormonal agents for overall survival (HR 1.047, 95% CI 0.688 to 1.592), TTP (pooled HR 0.994, 95% CI 0.691 to 1.431), and CBR (pooled odds ratio (OR) 1.044, 95% CI 0.828 to 1.315). Regarding toxicity, there were fewer joint disorders (OR 0.621, 95% CI 0.424 to 0.909; P = 0.014) in women receiving fulvestrant.

Tan 2013 meta‐analysis in 2013 examined two trials that we also included in our review that tested fulvestrant at 250 mg in combination with anastrozole versus anastrozole alone, with a total of 514 women (FACT; Mehta 2012). The HR for PFS was 0.88 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.09, 95% prediction intervals (PI) 0.65 to 1.21), overall survival 0.88 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.08; 95% PI 0.68 to 1.14), and the pooled OR for response rate was 1.13 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.63; 95% PI 0.78 to 1.65), which did not show a significant difference between fulvestrant and anastrozole in combination versus anastrozole.

The systematic review by Flemming 2009 examined EFECT, Howell, Fulvestrant vs Anastrozole 2002, Howell, Fulvestrant vs Tamoxifen 2004, and Osborne 2002. Flemming et al found no difference between fulvestrant and control of either anastrozole or exemestane across efficacy and safety endpoints in the second‐line endocrine‐therapy setting. Fulvestrant at 250 mg was therefore recommended as an alternative therapy to aromatase inhibitors in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer who experienced recurrence on adjuvant endocrine therapy or in the second‐line metastatic setting.

The network meta‐analysis by Cope 2013 with parametric survival models in 2013 demonstrated that “Fulvestrant 500 mg is expected to be more efficacious than fulvestrant 250 mg, megestrol acetate, and anastrozole 1 mg and at least as efficacious as exemestane and letrozole 2.5 mg in terms of PFS among postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer after failure on endocrine therapy.”

Gong 2014 published a meta‐analysis in 2014 that examined four trials, three of which we included in our review (Howell, Fulvestrant vs Anastrozole 2002; Osborne 2002; Xu 2011), and one that we excluded from our review (Carlson 2009; Carlson 2012 as it used gefitinib; see Characteristics of excluded studies). These four studies included 1226 women in the meta‐analysis, which found no difference in efficacy or tolerability/toxicity between fulvestrant and anastrozole with TTF (HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.17), complete response (RR 1.79, 95% CI 0.93 to 3.43), and partial response (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.21).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

As evidenced from our pooled data from 4514 women examined in our review, fulvestrant (mostly administered at the anachronistic dose of 250 mg) was as effective as other standard endocrine therapies with respect to efficacy (measured by PFS, CBR, overall survival), toxicity, and quality of life. It is important to highlight that even at this inferior dose (Di Leo 2010; Di Leo 2012), fulvestrant was as effective and well tolerated as other comparator endocrine therapies. In our one included study of fulvestrant at the 500 mg dose level, fulvestrant was superior to anastrozole (FIRST).

In the context of treating women with advanced hormone‐sensitive breast cancer in clinic, we are mindful that the goal of systemic therapy is to optimise quality of life and survival by maximising each available line of systemic therapy, provided tolerability and toxicity permit. In this context, our review demonstrated that fulvestrant is as effective and well tolerated as other standard endocrine therapies in both the first‐ and second‐line settings for the treatment of advanced disease. We also demonstrated that there is no benefit or utility for the co‐prescription of fulvestrant with other endocrine therapy in two studies included in our review.

Our findings are that fulvestrant monotherapy at the standard 500 mg dose should be considered as an effective and safe option in the treatment of postmenopausal women with advanced hormone‐sensitive breast cancer when treatment with endocrine therapy is indicated.

Implications for research.

We await the results of the phase III study, NCT01602380, which further tests the 500 mg dose level of fulvestrant compared to anastrozole. Any future studies examining and testing efficacy and toxicity of fulvestrant should use the 500 mg dose level rather than 250 mg. More research is required to test 500 mg fulvestrant with other standard therapies, that is steroidal aromatase inhibitors and tamoxifen, to assess whether at the standard dose fulvestrant is in fact superior to these other comparators rather than simply equivalent.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the advice received from Dianne O'Connell and Jessica Barrett. We also acknowledge the authors that were involved in the first draft of this protocol and are not involved in further developments of the protocol and review stage: E Amir, J Beyene, P Shah, and H Chen. We acknowledge Orit Freedman and Mark Clemons for their contribution during the protocol phase of our review. We also thank Melina Willson for her invaluable contribution and guidance in the processes and conduct of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL

MeSH descriptor: [Breast Neoplasms] explode all trees

breast near cancer*

breast near neoplasm*

breast near carcinoma*

breast near tumour*

breast near tumor*

#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6

locally advance* breast cancer* or locally advance* breast neoplasm* or locally advance* breast carcinoma* or locally advance* breast tumour* or locally advance* breast tumor* or metastatic breast cancer* or metastatic breast neoplasm* or metastatic breast carcinoma* or metastatic breast tumour* or metastatic breast tumor*

#7 and #8

Fulvestrant or Faslodex or selective oestrogen receptor down‐regulator* or selective estrogen receptor down‐regulator* or SERD

#9 and #10

Appendix 2. MEDLINE

| 1 | randomized controlled trial.pt. |

| 2 | controlled clinical trial.pt. |

| 3 | randomized.ab. |

| 4 | placebo.ab. |

| 5 | drug therapy.fs. |

| 6 | randomly.ab. |

| 7 | trial.ab. |

| 8 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 |

| 9 | exp Breast Neoplasms/ |

| 10 | (breast adj6 cancer$).mp. |

| 11 | (breast adj6 neoplasm$).mp. |

| 12 | (breast adj6 carcinoma$).mp. |

| 13 | (breast adj6 tumour$).mp. |

| 14 | (breast adj6 tumor$).mp. |

| 15 | ((locally advanced or metastatic) adj5 (breast$ adj5 (neoplasm$ or cancer$ or tumo?r$ or carcinoma$))).mp. |

| 16 | 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 |

| 17 | Fulvestrant.mp. |

| 18 | Faslodex.mp. |

| 19 | selective oestrogen receptor down‐regulator*.mp. |

| 20 | selective estrogen receptor down‐regulator*.mp. |

| 21 | SERD.mp. |

| 22 | 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 |

| 23 | 8 and 16 and 22 |

| 24 | Animals/ not Humans/ |

| 25 | 23 not 24 |

Appendix 3. EMBASE

random* OR factorial* OR crossover* OR cross AND over* OR placebo* OR (doubl* AND blind*) OR (singl* AND blind*) OR assign* OR allocat* OR volunteer* OR 'crossover procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp

'breast'/exp OR 'breast disease'/exp AND 'neoplasm'/exp OR 'breast tumor'/exp OR (breast* NEAR/5 neoplas*):ab,ti OR (breast* NEAR/5cancer*):ab,ti OR (breast* NEAR/5 carcin*):ab,ti OR (breast* NEAR/5 tumo*):ab,ti OR (breast* NEAR/5 metasta*):ab,ti OR (breast* NEAR/5malig*):ab,ti

'metastatic breast cancer'/exp OR 'metastatic breast cancer' OR 'metastatic breast neoplasm' OR 'metastatic breast carcinoma' OR'metastatic breast tumour' OR 'metastatic breast tumor' OR 'locally advanced breast cancer' OR 'locally advanced breast neoplasm'OR 'locally advanced breast carcinoma' OR 'locally advanced breast tumour' OR 'locally advanced breast tumor'

#2 OR #3

'fulvestrant'/exp OR fulvestrant

'faslodex'/exp OR faslodex

'selective oestrogen receptor down‐regulator'

'selective estrogen receptor down‐regulator'

serd

#5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9

#1 AND #4 AND #10

#11 NOT ([animals]/lim NOT [humans]/lim)

#12 AND [embase]/lim

Appendix 4. WHO ICTRP

Basic Searches:

1. Fulvestrant (SERDs) for hormone‐sensitive metastatic breast cancer

2. Metastatic breast cancer AND Fulvestrant

3. Metastatic breast cancer AND Faslodex

4. Metastatic breast cancer AND selective oestrogen receptor down‐regulator

5. Metastatic breast cancer AND selective estrogen receptor down‐regulator

6. Metastatic breast cancer AND SERM

7. Locally advanced breast cancer AND Fulvestrant

8. Locally advanced breast cancer AND Faslodex

9. Locally advanced breast cancer AND selective oestrogen receptor down‐regulator

10. Locally advanced breast cancer AND selective estrogen receptor down‐regulator

11. Locally advanced breast cancer AND SERM

Advanced Searches:

1. Title: Fulvestrant (SERDs) for hormone‐sensitive metastatic breast cancer

Recruitment Status: ALL

2. Condition: metastatic breast cancer or locally advanced breast cancer

Intervention:Fulvestrant or Faslodex or selective oestrogen receptor down‐regulator% or selective estrogen receptor down‐regulator% or SERD

Recruitment Status:

ALL

Appendix 5. ClinicalTrials.gov

Basic Searches:

1. Fulvestrant (SERDs) for hormone‐sensitive metastatic breast cancer

2. Metastatic breast cancer AND Fulvestrant

3. Metastatic breast cancer AND Faslodex

4. Metastatic breast cancer AND selective oestrogen receptor down‐regulator

5. Metastatic breast cancer AND selective estrogen receptor down‐regulator

6. Metastatic breast cancer AND SERM

7. Locally advanced breast cancer AND Fulvestrant

8. Locally advanced breast cancer AND Faslodex

9. Locally advanced breast cancer AND selective oestrogen receptor down‐regulator

10. Locally advanced breast cancer AND selective estrogen receptor down‐regulator

11. Locally advanced breast cancer AND SERM

Advanced Searches:

1. Title: Fulvestrant (SERDs) for hormone‐sensitive metastatic breast cancer

Recruitment: All studies

Study Results: All studies

Study Type: All studies

Gender: All studies

2. Condition: metastatic breast cancer or locally advanced breast cancer

Intervention:Fulvestrant or Faslodex or selective oestrogen receptor down‐regulator* or selective estrogen receptor down‐regulator* or SERD

Recruitment: All studies

Study Results: All studies

Study Type: All studies

Gender: All studies

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Progression‐free survival.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Fulvestrant vs other endocrine therapy | 9 | 4258 | Hazard Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.89, 1.02] |

| 1.1 Fulvestrant 500 mg vs anastrozole | 1 | 205 | Hazard Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.47, 0.93] |

| 1.2 Fulvestrant 250 mg vs anastrozole | 5 | 2293 | Hazard Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.85, 1.02] |

| 1.3 Fulvestrant 250 mg vs exemestane | 2 | 1173 | Hazard Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.85, 1.08] |

| 1.4 Fulvestrant 250 mg vs tamoxifen | 1 | 587 | Hazard Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.98, 1.42] |

| 2 First‐line vs second‐line or more | 9 | 4251 | Hazard Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.89, 1.01] |

| 2.1 Firstline | 4 | 1996 | Hazard Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.84, 1.03] |

| 2.2 Secondline or more | 5 | 2255 | Hazard Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.88, 1.04] |

| 3 Combination fulvestrant vs single agent with other endocrine therapy | 9 | 4251 | Hazard Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.89, 1.01] |

| 3.1 Single agent fulvestrant with other endocrine therapy | 7 | 3046 | Hazard Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.90, 1.04] |

| 3.2 Combination vs other endocrine therapy | 2 | 1205 | Hazard Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.77, 0.99] |

Comparison 2. Clinical benefit rate.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Fulvestrant vs other endocrine therapy | 9 | 4105 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.97, 1.10] |

| 1.1 Fulvestrant 500 mg vs anastrozole | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.90, 1.30] |

| 1.2 Fulvestrant 250 mg vs anastrozole | 5 | 2293 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.99, 1.14] |

| 1.3 Fulvestrant 250 mg vs exemestane | 2 | 1020 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.90, 1.31] |

| 1.4 Fulvestrant 250 mg vs tamoxifen | 1 | 587 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.76, 1.00] |

| 2 Clinical benefit rate (first‐line vs second‐line) | 9 | 4104 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.96, 1.07] |

| 2.1 Firstline | 4 | 1999 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.94, 1.07] |

| 2.2 Secondline | 5 | 2105 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.92, 1.15] |

| 3 Combination vs monotherapy fulvestrant | 9 | 4104 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.96, 1.07] |

| 3.1 Monotherapy fulvestrant vs other endocrine therapy | 7 | 2896 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.93, 1.09] |

| 3.2 Combination with fulvestrant vs other endocrine therapy | 2 | 1208 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.95, 1.12] |

Comparison 3. Overall survival.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Fulvestrant vs other endocrine therapy | 5 | 2480 | Hazard Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.87, 1.09] |

Comparison 4. Toxicity.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vasomotor | 8 | 3544 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.89, 1.18] |

| 1.1 Fulvestrant 500 mg vs anastrozole | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.46, 1.89] |

| 1.2 Fulvestrant 250 mg vs anastrozole | 4 | 1590 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.26 [1.01, 1.58] |

| 1.3 Fulvestrant 250 mg vs exemestane | 2 | 1168 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.77, 1.19] |

| 1.4 Fulvestrant 250 mg vs tamoxifen | 1 | 581 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.46, 1.00] |

| 2 Arthralgia | 7 | 3244 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.86, 1.09] |

| 2.1 Fulvestrant 500mg vs anastrozole | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.41 [0.66, 3.03] |

| 2.2 Fulvestrant 250mg vs anastrozole | 4 | 1871 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.86, 1.16] |

| 2.3 Fulvestrant 250mg vs exemestane | 2 | 1168 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.72, 1.07] |

| 3 Gynaecological | 6 | 2848 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.94, 1.57] |

| 3.1 Fulvestrant 500mg vs anastrozole | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.04 [0.46, 35.52] |

| 3.2 Fulvestrant 250mg vs anastrozole | 3 | 1585 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.92, 1.66] |

| 3.3 Fulvestrant 250mg vs exemestane | 1 | 477 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.47 [1.20, 5.08] |

| 3.4 Fulvestrant 250mg vs tamoxifen | 1 | 581 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.12 [0.03, 0.54] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

EFECT.

| Methods | "Double‐blind, randomised placebo controlled trial of fulvestrant compared with exemestane after prior nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor therapy in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor‐positive, advanced breast cancer: results from EFECT" Accrued between August 2003 and November 2005 693 women enrolled across 138 centres worldwide Women randomly assigned to either fulvestrant or exemestane |

|

| Participants | Postmenopausal women with incurable, locally advanced, or metastatic breast cancer whose disease had relapsed during treatment of adjuvant endocrine therapy or during treatment with palliative NSAI for metastatic disease. Women were categorised as AI sensitive if the investigator determined that the woman had a CR, PR, or SD for at least 6 months during treatment with the AI for ABC. All other women, including all those who received the AI as adjuvant therapy, were defined as AI resistant. Female patients Median age 63 Well balanced between both groups, except fulvestrant cohort had a slightly greater number of women with both ER‐positive and PgR‐positive tumours (67.5%) vs exemestane (56.4%). Approximately 60% of women had 2 or more prior lines of hormonal therapy |

|

| Interventions | Intervention:

Fulvestrant: loading dose regimen was used, 500 mg on day 0, 250 mg on days 14 and 28, and 250 mg every 28 days thereafter. Placebo for fulvestrant was “oily excipient placebo was injected into each buttock”, administered at the same scheduling as fulvestrant. Comparator: Exemestane: tablets administered orally daily 25 mg dose. Placebo for exemestane was a “matched” tablet |

|

| Outcomes | TTP: at time of analysis, 82.1% of fulvestrant group and 87.4% of exemestane group had experienced a defined progression event. Median TTP was 3.7 months in both groups, with no statistically significant difference CBR: 7.4% of fulvestrant group and 6.7% of exemestane group had a documented response. In women with visceral involvement, CBR was 29% and 27% in the fulvestrant and exemestane arms, median DOR was 13.5 months fulvestrant and 9.8 exemestane Tolerability and toxicity: well tolerated in study, with 2% of fulvestrant‐treated women and 2.6% of exemestane‐treated women withdrawing because of an adverse event. Drug‐related SAEs were rare, occurring in 1.1% and 0.6% in each arm. No woman died due to drug‐related AE QOL: measured by FACT‐ES and TOI. No significant difference between arms |

|

| Notes | Inclusion criteria:

Postmenopausal > 60 years or age > 45 years with amenorrhoea for > 12 months or FSH in postmenopausal range or prior bilateral oophorectomy.

HR +ve disease, WHO‐PS 0 to 2, life expectancy of at least 3 months, and the presence of at least 1 measurable or assessable lesion. Up to 1 prior chemotherapy regimen for the treatment of ABC allowed. Exclusion criteria: Life‐threatening metastatic visceral disease, brain or leptomeningeal metastases, prior exposure to either fulvestrant or exemestane, extensive radiation or cytotoxic chemotherapy within the last 4 weeks, or history of bleeding diathesis or need for long‐term anticoagulation. Trial sponsored by AstraZeneca. Unspecified as to whether AstraZeneca was involved in the analyses |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Explicitly described as randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study with study drugs randomly allocated. The precise method of random allocation is frequently not discussed in detail in publications of major international co‐operative group studies |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Double‐blind, double‐dummy trial |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blind, double‐dummy trial |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (OS) | Low risk | OS unlikely to be affected by bias |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (TTP, CBR, Toxicity) All outcomes | Low risk | TTP defined as number of days from date of random assignment until the date of objective disease progression as per RECIST criteria. All women seen by a physician monthly until month 6 and every 3 months thereafter. Tumour assessment was performed every 8 weeks from baseline until month 6 and then every 3 months until disease progression |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (QoL) | Low risk | Measured with 2 instruments, FACT‐ES and TOI |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Data for efficacy outcomes were analysed and summarised on an ITT basis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes in the methods are reported in the results section of the trial publication |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified |

FACT.