Abstract

Background

Unilateral spatial neglect causes difficulty attending to one side of space. Various rehabilitation interventions have been used but evidence of their benefit is lacking.

Objectives

To assess whether cognitive rehabilitation improves functional independence, neglect (as measured using standardised assessments), destination on discharge, falls, balance, depression/anxiety and quality of life in stroke patients with neglect measured immediately post‐intervention and at longer‐term follow‐up; and to determine which types of interventions are effective and whether cognitive rehabilitation is more effective than standard care or an attention control.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (last searched June 2012), MEDLINE (1966 to June 2011), EMBASE (1980 to June 2011), CINAHL (1983 to June 2011), PsycINFO (1974 to June 2011), UK National Research Register (June 2011). We handsearched relevant journals (up to 1998), screened reference lists, and tracked citations using SCISEARCH.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of cognitive rehabilitation specifically aimed at spatial neglect. We excluded studies of general stroke rehabilitation and studies with mixed participant groups, unless more than 75% of their sample were stroke patients or separate stroke data were available.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected studies, extracted data, and assessed study quality. For subgroup analyses, review authors independently categorised the approach underlying the cognitive intervention as either 'top‐down' (interventions that encourage awareness of the disability and potential compensatory strategies) or 'bottom‐up' (interventions directed at the impairment but not requiring awareness or behavioural change, e.g. wearing prisms or patches).

Main results

We included 23 RCTs with 628 participants (adding 11 new RCTs involving 322 new participants for this update). Only 11 studies were assessed to have adequate allocation concealment, and only four studies to have a low risk of bias in all categories assessed. Most studies measured outcomes using standardised neglect assessments: 15 studies measured effect on activities of daily living (ADL) immediately after the end of the intervention period, but only six reported persisting effects on ADL. One study (30 participants) reported discharge destination and one study (eight participants) reported the number of falls.

Eighteen of the 23 included RCTs compared cognitive rehabilitation with any control intervention (placebo, attention or no treatment). Meta‐analyses demonstrated no statistically significant effect of cognitive rehabilitation, compared with control, for persisting effects on either ADL (five studies, 143 participants) or standardised neglect assessments (eight studies, 172 participants), or for immediate effects on ADL (10 studies, 343 participants). In contrast, we found a statistically significant effect in favour of cognitive rehabilitation compared with control, for immediate effects on standardised neglect assessments (16 studies, 437 participants, standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.35, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.09 to 0.62). However, sensitivity analyses including only studies of high methodological quality removed evidence of a significant effect of cognitive rehabilitation.

Additionally, five of the 23 included RCTs compared one cognitive rehabilitation intervention with another. These included three studies comparing a visual scanning intervention with another cognitive rehabilitation intervention, and two studies (three comparison groups) comparing a visual scanning intervention plus another cognitive rehabilitation intervention with a visual scanning intervention alone. Only two small studies reported a measure of functional disability and there was considerable heterogeneity within these subgroups (I² > 40%) when we pooled standardised neglect assessment data, limiting the ability to draw generalised conclusions.

Subgroup analyses exploring the effect of having an attention control demonstrated some evidence of a statistically significant difference between those comparing rehabilitation with attention control and those with another control or no treatment group, for immediate effects on standardised neglect assessments (test for subgroup differences, P = 0.04).

Authors' conclusions

The effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation interventions for reducing the disabling effects of neglect and increasing independence remains unproven. As a consequence, no rehabilitation approach can be supported or refuted based on current evidence from RCTs. However, there is some very limited evidence that cognitive rehabilitation may have an immediate beneficial effect on tests of neglect. This emerging evidence justifies further clinical trials of cognitive rehabilitation for neglect. However, future studies need to have appropriate high quality methodological design and reporting, to examine persisting effects of treatment and to include an attention control comparator.

Plain language summary

Cognitive rehabilitation for spatial neglect following stroke

The benefit of cognitive rehabilitation (therapy) for unilateral spatial neglect, a condition that can affect stroke survivors, is unclear. Unilateral spatial neglect is a condition that reduces a person's ability to look, listen or make movements in one half of their environment. This can affect their ability to carry out many everyday tasks such as eating, reading and getting dressed, and restricts a person's independence. Our review of 23 studies involving 628 participants with stroke found insufficient high quality evidence to tell us the effect of therapy designed for treating neglect. We did find some limited evidence which suggested that such therapy might be helpful, but the quality of this evidence was poor and more research is needed to confirm this finding. People with neglect should continue to receive general stroke rehabilitation services and to have the opportunity to take part in high‐quality research.

Background

Description of the condition

Stroke can affect cognitive as well as physical and sensory abilities (Wade 1985). Cognitive deficits include a disorder of spatial awareness known as unilateral spatial neglect. The most widely quoted definition of neglect is a description of the resulting behavioural disabilities: "fails to report, respond, or orient to novel or meaningful stimuli presented to the side opposite a brain lesion" (Heilman 1993). This definition does not describe the causal mechanism of neglect but indicates that it is not simply due to sensory or motor defects. Neglect is a disorder which can reduce a person's ability to look, listen or make movements towards one half of their environment. This can also affect their ability to carry out many everyday tasks, such as eating, reading and getting dressed (Katz 1999). Stroke may differentially affect our ability to direct our attention in the visual, auditory or tactile modalities. Since different types of neglect can occur, several terms are used in clinical practice, such as visual neglect, motor neglect, hemineglect, and inattention (Bailey 1999). Although people do sometimes neglect their ipsilesional (same) side, most researchers and clinicians focus on the far more common neglect of contralesional (opposite) side space.

The reported incidence of neglect in stroke patients has varied from as high as 90% (Massironi 1988) to as low as 8% (Sunderland 1987). The figures depend on the operational definition, selection criteria for patients and method of assessment employed (Bailey 1999; Bowen 1999; Ferro 1999). A previous systematic review found that, in 16 of the 17 studies making the comparison, contralesional neglect occurred more often after right than left hemisphere stroke (Bowen 1999). Cognitive dysfunction, such as neglect, can determine the outcome of rehabilitation by adversely affecting mobility, discharge destination, length of hospital stay, meal preparation and independence in self‐care skills (Barer 1990; Bernspang 1987; Neistadt 1993). In the light of these functional implications, it is not surprising that the rehabilitation of neglect is an important aim in stroke rehabilitation.

Description of the intervention

Cognitive rehabilitation is the collective label for a wide range of therapeutic interventions (Lincoln 2012). These share a common purpose, to reduce the adverse effects that cognitive impairments have on a person’s ability to perform everyday activities, their social role participation and quality of life. There are two very different approaches known as restitutive and compensatory. Techniques using the restitutive approach aim to alter the underlying cognitive impairment. Compensatory techniques include teaching strategies to make behavioural adjustments. The emphasis in compensatory strategies is on coping with and finding ways of adapting to existing impairments. Restitution approaches are more often used in the early stage of the stroke pathway when plasticity is thought to be greatest, and compensatory strategies are typically used later. However, this is not a hard and fast rule. In most countries cognitive rehabilitation is provided by psychologists and occupational therapists or their assistants, although other professionals are also involved, for example orthopists for prisms.

It is common to categorise neglect interventions as involving either bottom‐up or top‐down processing (Parton 2004). Top‐down approaches aim to train the person to voluntarily compensate for their neglect and require awareness of the disorder. Methods include training in scanning and usually provide feedback (Pizzamiglio 2004). Top‐down approaches focus on the level of disability rather than impairment. Bottom‐up approaches do not require awareness of the disorder. They aim to modify underlying factors, i.e. to alter the impaired representation of space. Prism‐wearing and prism adaptation training are popular recent examples of a bottom‐up approach (Rossetti 1998). By wearing base‐left wedge prisms in spectacles visual space is perturbed to the right making it more likely to be seen. Other examples of bottom‐up processing approaches include eye patching and the use of devices to stimulate the neglected side. We included both bottom‐up and top‐down approaches, and categorised each intervention within this framework.

Why it is important to do this review

The two main reasons for this review are, first, that neglect is a major problem for people with stroke and secondly, there is clinical uncertainty about the effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation. Neglect affects long‐term outcome. It can impede active participation in stroke rehabilitation programs and decrease independence in activities of daily living (ADL) and quality of life (Jehkonen 2006). Several recent reviews have argued that cognitive rehabilitation is effective for people with various cognitive impairments including neglect after a stroke (Cicerone 2005; Jutai 2003) or a traumatic brain injury (Cicerone 2009). Some of the non‐randomised evidence included in these reviews may introduce bias. This updated review aimed to systematically consider the evidence from RCTs on the effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation aimed at spatial neglect.

Objectives

To assess whether cognitive rehabilitation improves functional independence, neglect (measured using standardised assessments), destination on discharge, falls, balance, depression/anxiety and quality of life in stroke patients with neglect measured immediately post‐intervention and at longer‐term follow‐up; to determine which types of intervention are effective and whether cognitive rehabilitation is more effective than standard care or an attention control.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

For the first version of this review we sought all controlled trials in which cognitive rehabilitation was compared with a control treatment. In addition to well‐designed randomised controlled trials (RCTs), we considered other studies (such as those described as quasi‐random) for inclusion but, if selected, we assigned these a lower methodological quality score. However, in the previous version (2006) and this update, we excluded all non‐randomised studies to reduce selection bias. These are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Types of participants

This review was confined to trials that included participants with neglect following stroke. Stroke was confirmed by neurological examination or brain scanning, or both, and neglect by neuropsychological assessment. Thus, we excluded studies that included participants whose deficits were the result of head trauma, brain tumour or any other brain damage unless a subgroup of those with stroke could be identified for which there were separate results, or more than 75% of participants in the sample were stroke patients. We excluded studies of people with general perceptual problems unless a subgroup with neglect could be identified. A separate review has been published on cognitive rehabilitation for people with perceptual problems (Bowen 2011).

Types of interventions

To be included in the review, a clinical trial had to report a comparison between an active treatment group that received one of various cognitive rehabilitation programs for neglect versus a control group that received either an alternative form of treatment or none. Cognitive rehabilitation was broadly defined to include therapy activities designed to directly reduce the level of the neglect impairment or the resulting disability. We excluded drug treatments. Cognitive rehabilitation could include structured therapy sessions, computerised therapy, prescription of aids and modification of the participants' environment as long as these were specific to neglect. The aim was to directly target the neglect rather than to examine whether people with neglect happened to benefit from general rehabilitation services.

Types of outcome measures

We were interested in outcomes at two timepoints: (1) immediately after the end of an intervention, and (2) persisting beyond the end of intervention (i.e. follow‐up outcome).

Primary outcomes

Ratings on measures of functional disability: we included the following scales: Catherine Bergego Scale, Everyday Neglect Questionnaire, Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living scale, Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, Frenchay Activities Index, Rivermead ADL, Edmans EADL, Modified Rankin Scale, Barthel ADL Index, Functional Independence Measure, Katz Index of Activities of Daily Living, and Rehabilitation Activities Profile. When more than one of these scales was reported, we used the scale listed first above. We excluded functional measures designed for a specific study e.g. obstacle avoidance, observation of an ADL task.

For the 2006 update of the review the primary outcome was defined as 'Ratings on measures of functional disability: activities of daily living (ADL) scales: Barthel Index (BI), Functional Independence Measure (FIM), Frenchay Activities Index (FAI), or neglect‐specific ADL measures'. As this was not a comprehensive list of functional disability measures, we extended the scales listed in order to be more comprehensive and to avoid having to make decisions after the identification of studies. We checked back through the studies included in the 2006 update and this clarification did not lead to any changes to the outcomes included from those studies.

Secondary outcomes

Performance on standardised neglect assessments: target cancellation (single letter, double letter, line, shape), line bisection. In addition to a conventional subtest score (such as letter cancellation) the behavioural summary score from the Behavioural Inattention Test (BIT) was used when available. In this updated review we removed outcomes of attention and drawing tests to reduce the number of outcomes being reviewed and to concentrate on those most relevant to neglect.

Discharge destination: whether a person was discharged to live in their own home or to a care facility was included where available, with deaths before discharge treated as not discharged to their own home.

Balance: Berg balance scale, Functional Reach, Get up and go test, Standing Balance test, Step Test or other standardised balance measure. We did not include measures of weight distribution or postural sway during standing, as the relationship between ability to maintain balance and these outcomes is not established.

Falls: number of reported falls, Falls Efficacy Scale.

Depression/anxiety: e.g. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Beck Depressive Inventory, General Health Questionnaire, Geriatric Depression Scale.

Quality of life and social isolation: EQ5D (Health‐related quality of life scale, Quality of Well Being scale, SF36).

Adverse events: (any reported adverse events, excluding falls).

The 2006 update of the review only included secondary outcomes (1) and (2). For the 2013 update we extended these to reflect outcomes of importance to people with stroke. No studies had been excluded on the basis of not having suitable outcome measures and we were therefore confident that this change did not require us to repeat any previous searches. We re‐appraised all studies included in the 2006 update of the review and extracted data on any of the additional secondary outcomes.

Search methods for identification of studies

See the 'Specialized register' section in the Cochrane Stroke Group module. We searched for relevant trials in all languages and arranged translation of trial reports published in languages other than English.

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register, which was last searched by the Managing Editor in June 2012. In addition, we searched the following electronic databases: MEDLINE (1998 to June 2011; Appendix 1), EMBASE (1998 to June 2011; Appendix 2), CINAHL (1998 to June 2011; Appendix 3), PsycINFO (1998 to June 2011; Appendix 4), and the National Research Register (June 2011). We developed the search strategies with the help of the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator.

For the purpose of this and other reviews (Lincoln 2001; Das Nair 2007), we originally searched simultaneously for trials in four areas of stroke rehabilitation (cognitive rehabilitation, occupational therapy, speech therapy, and treatment for mood disorders) using online computerised bibliographic databases: MEDLINE (1966 to 1998), BIDS EMBASE (1980 to 1998), CINAHL (1983 to 1998), PsycLIT (1974 to 1998) and CLINPSYCH (1980 to November 1994). We conducted these computerised searches using combinations of the following descriptors/key words: stroke/cerebrovascular accidents/neurological disability and randomised controlled/clinical trials/random allocation/double blind method and rehabilitation/remedial therapy/treatment/intervention and cognitive/unilateral neglect/visuospatial/visuoperceptual/memory/attention span/concentration/hemianopia/attentional deficits/activities of daily living/occupational therapy/leisure/dressing/self‐care/domiciliary rehabilitation.

-

To ensure that studies not listed in the above databases were not overlooked, in 1999 we handsearched all volumes of the journals listed below. The 1999 handsearch included a broad range of journals as it covered studies in four areas of rehabilitation, only one of which (neglect) was relevant to this specific review. Therefore, for the 2006 update we checked the Master List of journals that is searched by The Cochrane Collaboration (www.cochrane.us/masterlist.asp). We found that the journals relevant to neglect had been handsearched. The resulting studies would be found from the search of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) carried out quarterly by the Cochrane Stroke Group and we did not wish to duplicate effort:

American Journal of Occupational Therapy (1947 to 1998);

Aphasiology (1987 to 1998);

Australian Occupational Therapy Journal (1965 to 1998);

British Journal of Occupational Therapy (1950 to 1998);

British Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation (1994 to 1998);

Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy (1970 to 1998);

Clinical Rehabilitation (1987 to 1998);

Disability Rehabilitation (1992 to 1998), formerly International Disability Studies (1987 to 1991), formerly International Rehabilitation Medicine (1979 to 1986);

International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders (1998), formerly European Journal of Disorders of Communication (1985 to 1997), formerly British Journal of Disorders of Communication (1977 to 1984);

Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings (1994 to 1998), formerly Journal of Clinical Psychology (1944 to 1994);

Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities (1992 to 1998), formerly Journal of the Multihandicapped Person (1989 to 1991);

Journal of Rehabilitation (1963 to 1998);

International Journal of Rehabilitation Research (1977 to 1998);

Journal of Rehabilitation Science (1989 to 1996);

Neuropsychological Rehabilitation (1987 to 1998);

Neurorehabilitation (1991 to 1998);

Occupational Therapy International (1994 to 1998);

Physiotherapy Theory and Practice (1990 to 1998), formerly Physiotherapy Practice (1985 to 1989);

Physical Therapy (1988 to 1998);

Rehabilitation Psychology (1982 to 1998);

The Journal of Cognitive Rehabilitation (1988 to 1998), formerly Cognitive Rehabilitation (1983 to 1987).

We screened reference lists of all relevant articles.

We used the three citation index databases Science Citation Index (SCI), Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and Arts and Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI) for citation tracking of relevant included studies.

Data collection and analysis

The pre‐1999 searching and selection activities were carried out simultaneously for four reviews. We carried out the most recent updated searches for this review in 2012.

Selection of studies

For this update one review author (CH or AP) screened the titles of records obtained from searches of the electronic databases and excluded irrelevant papers. Two authors (CH and AB or AP) independently assessed the abstracts of the remaining papers and we obtained the full text of papers that were considered possibly relevant. At least two review authors (NBL, AB for 1999 and 2006 versions; NBL, AB, CH and AP for 2013 version) independently selected studies to be included in this review using the four inclusion criteria (types of trials, participants, interventions and outcome measures). We independently assessed the methodological quality of the studies, with reference to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Cochrane Handbook), selected, entered, and cross‐checked data for analysis. We resolved disagreements by discussion.

Data extraction and management

We extracted study characteristics and outcome data. We recorded the following information: method of participant assignment, adequacy of concealment, adequacy of matching at baseline, description of intervention, sample size, numbers lost to follow‐up, types of dependent variable(s), blinding at outcome assessment, reported results and publication details. If these data were not available or unclear from the reports then we contacted the study authors for further information or clarification. We used intention‐to‐treat analyses where possible. We categorised the type of intervention as either a bottom‐up or top‐down processing rehabilitation approach; two review authors categorised each intervention independently and resolved any differences through discussion involving another review author.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For the 2006 update we assessed all studies for quality of allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessor, and rated those assessed to be at low risk of bias as 'A'. We rated those assessed to be of unclear risk of bias or high risk of bias as 'B'. For this version of the review two review authors independently documented risk of bias for all new studies, classifying each as being at 'high risk', 'low risk' or 'unclear risk' for the following potential biases, using the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias (Cochrane Handbook, Chapter 8).

Allocation concealment (selection bias): studies with adequate concealment included those that used either central randomisation at a site remote from the study, computerised allocation in which records were in a locked readable file that could be assessed only after entering participant details, or the drawing of opaque envelopes. Studies with inadequate concealment included those using open list or table of random numbers, open computer systems, or drawing of non‐opaque envelopes. Studies with unclear concealment included those with no or inadequate information.

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias): adequate masking included studies that stated that a masked (blinded) outcome assessor was used, and did not identify any 'unmasking'. Inadequate blinding included studies that did not use a masked outcome assessor, or where the report clearly identified that 'unmasking' occurred during the study. We documented blinding as unclear if there was no or insufficient information to judge whether or not an outcome assessor was masked.

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias): studies adequately addressing incomplete outcome data either had: no missing outcome data; missing outcome data that were unlikely to be related to true outcome; missing outcome data that were balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; a reported effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes that were not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size; or missing data that had been imputed using appropriate methods. Studies inadequately addressing incomplete outcome data either had: missing outcome data that were likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups; a reported effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size; or as‐treated analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation. We documented the addressing of incomplete outcome data as unclear if there was insufficient information to allow us to assess this.

Free of systematic differences in baseline characteristics of groups compared: we assessed a study to be at low risk of bias if there were no differences between groups at baseline; at high risk of bias if there were systematic differences in baseline characteristics of the groups; and at unclear of bias if baseline data were not reported, or if it was unclear whether differences were systematic or random.

Adjustment for baseline differences in the analyses: we assessed a study to be at low risk of bias if either there were no baseline differences (i.e. adjustment is not required) or if appropriate adjustment for the baseline differences had been computed. We assessed a study to be at high risk of bias if there were baseline differences and no adjustment had been computed. We reported this as unclear if there was insufficient information to allow us to assess this.

For the 2006 version of the review, we only documented information on allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessor. We systematically assessed risk of bias relating to other methodological features in the earlier studies during this update.

Measures of treatment effect

Where a cross‐over design was used we only included data from the first treatment period. Where initial participants were randomised but later allocations were non‐randomised, we only included the study if we could extract the data on those randomised. If not we excluded the study.

Unit of analysis issues

We treated activities of daily living (ADL) data, such as the Barthel Index (BI), as continuous measures and we requested or calculated the mean and standard deviation (SD) data. We are aware that there is a difference of opinion regarding how to deal with ordinal level ADL scales. We have treated them as interval level measures, as in practice it makes relatively little difference. This is supported by a study of parametric versus nonparametric methods in stroke trials, which recommended that means and SDs should be reported (Song 2005). We analysed outcomes as the standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence interval (CI). We used random‐effects models.

For all analyses of continuous data, we entered data so that a higher score represented a favourable outcome, and the right label of the graph favoured the experimental group. For some of the neglect assessments studies reported outcomes for which a low score was better; for example for 'number of errors' in cancellation tests and 'line bisection'. We multiplied these outcomes, for which a low score was better, by ‐1 in order to pool them with other neglect assessments for which the direction of effect was opposite.

We used odds ratios (ORs) for 'discharge destination', comparing the numbers discharged to their own homes. We treated deaths before discharge as 'not discharged to their own home'. In this way those discharged home were compared with those not discharged home. We calculated ORs for the outcome 'falls', comparing the number of events (falls) within each group.

We used the Cochrane Review Manager 5.1 software for all analyses (RevMan 2011).

Data synthesis

We compared a rehabilitation approach with any other control for both immediate and persisting effects. The controls used were standard care, no treatment or 'attention control' (i.e. where the control group were given extra hours of contact in addition to their standard care to ensure the experimental and control groups had similar amounts of attention from a therapist). We also compared alternative neglect therapies.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to carry out subgroup analysis to explore the effect of comparison with an attention control, compared with comparison with no treatment or standard care.

In this update we also added a subgroup comparison of bottom‐up or top‐down interventions (see Description of the intervention). We categorised bottom‐up approaches as either prisms, patching or other interventions, and top‐down approaches as either feedback or cueing, visual scanning training or mental imagery.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of only including studies with adequate allocation concealment or adequate blinding (i.e. studies assessed to be at low risk of bias).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The results of this review are based on 23 studies involving 628 participants.

In the 2006 version of this review we included 12 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (306 participants). We did not document details of the searching process and identification of these RCTs. Details of 22 studies that we excluded during the 2006 update, when we removed quasi‐randomised trials, are documented as excluded studies.

For the 2006 version, we identified one RCT of spatial neglect and placed it in 'Studies awaiting assessment' (Cubelli 1993). We have subsequently been unable to get further information relating to this study, and have therefore moved it to excluded studies. In the 2006 version, we listed three ongoing RCTs (Kerkhoff 2005; Rossetti 2005; Turton 2005). The latter has been completed and entered into this update as Turton 2010 (replacing Turton 2005). Multiple publications by Kerkhoff made it difficult to identify which publication corresponded with the Kerkhoff 2005 study that had been identified through personal communication in 2006. However, we identified a report published in 2006 that we have assumed refers to the previously ongoing study. This study did not randomly allocate participants to groups and we have therefore excluded Kerkhoff 2005 (see Characteristics of excluded studies for more information). We have not been able to gain further information for Rossetti 2005 and have therefore left this as an ongoing study. We did not identify any additional ongoing trials for this update.

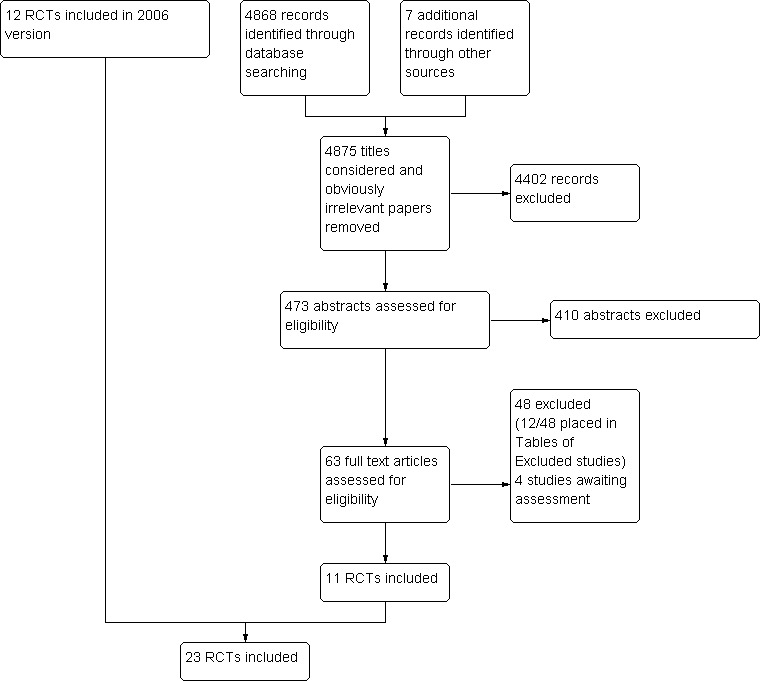

For this update, we identified 11 additional RCTs. One review author (CH or AP) considered 4875 titles and excluded 4402 obviously irrelevant studies, leaving 473 for consideration. Two review authors (CH, AB or AP) applied selection criteria to these 473 abstracts and classified 63 as possibly relevant. Two review authors (CH, AB or AP) assessed the full papers of these 63 abstracts, leading to the inclusion of 11 RCTs. There was insufficient information for four studies: we have categorised these as studies awaiting classification. We added details of 12 of the 48 excluded studies to the Characteristics of excluded studies table; the remainder were very obviously not relevant to this review. We did not document details of searches prior to this update, but Figure 1 illustrates the results of the 2012 searches, added to the 12 studies included in 2006.

1.

Study flow diagram, detailing results of 2012 searches added to 2006 results.

Included studies

We included data from 628 participants in 23 RCTs: 12 from the 2006 version of this review: Cherney 2002; Cottam 1987; Edmans 2000; Fanthome 1995; Kalra 1997; Robertson 1990; Robertson 2002; Rossi 1990; Rusconi 2002; Weinberg 1977; Wiart 1997; Zeloni 2002, and an additional 11 RCTS identified for this update: Ferreira 2011; Fong 2007; Kerkhoff 2012a; Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009; Mizuno 2011; Nys 2008; Polanowska 2009; Schroder 2008; Tsang 2009; Turton 2010; Welfringer 2011).

Studies had small sample sizes, with a mean size of 27 participants. Four studies had 10 or fewer participants (Cherney 2002: n = 4; Ferreira 2011: n = 10; Kerkhoff 2012a: n = 6; Zeloni 2002: n = 8) and two studies had 50 or more participants (Kalra 1997: n = 50; Fong 2007: n = 60). Statistical power was rarely commented on, but some studies (such as Cherney 2002, Ferreira 2011, Kalra 1997 and Welfringer 2011) did explicitly state that they were intended as pilot or feasibility studies.

All studies were of people with neglect after stroke. However, some studies reported that participants also had visual sensory deficits. Complete hemianopia was present in three of the six participants in the experimental group and one of six participants in the control group in Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009, and in three out of 18 participants in the experimental group and in three of the 20 participants in the control group in Mizuno 2011. In Rossi 1990 some of the participants may have had visual sensory deficits (visual field defects or scanning problems) as well as or instead of neglect: there were 12 out of 18 participants with a visual sensory deficit in the experimental group and 15 of 21 participants in the control group.

Twenty of the 23 included studies only included participants with right hemisphere stroke (Cherney 2002; Cottam 1987; Fanthome 1995; Ferreira 2011; Fong 2007; Kerkhoff 2012a; Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009; Mizuno 2011; Nys 2008; Polanowska 2009; Robertson 1990; Robertson 2002; Rusconi 2002; Schroder 2008; Tsang 2009; Turton 2010; Weinberg 1977; Welfringer 2011; Wiart 1997; Zeloni 2002). The others included those with either left or right hemisphere lesions, although in each study there were more people with right hemisphere lesions.

Six of the centres contributing to the 23 RCTs were based in the UK (Edmans 2000; Fanthome 1995; Kalra 1997; Robertson 1990; Robertson 2002; Turton 2010); four were based in North America (Cherney 2002; Cottam 1987; Rossi 1990; Weinberg 1977); three in Germany (Kerkhoff 2012a; Schroder 2008; Welfringer 2011); two in Italy (Rusconi 2002; Zeloni 2002); two in Hong Kong (Fong 2007; Tsang 2009), and one each in France (Wiart 1997), Netherlands (Nys 2008), Finland (Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009), Brazil (Ferreira 2011), Poland (Polanowska 2009), and Japan (Mizuno 2011).

Many studies recruited from inpatient rehabilitation hospitals (such as Cottam 1987; Fong 2007; Mizuno 2011; Polanowska 2009; Rusconi 2002; Tsang 2009) or specialist inpatient stroke services (for example, Edmans 2000; Kalra 1997; Nys 2008; Turton 2010). In some cases it was not clear where participants were recruited, and whether or not they were inpatients (Ferreira 2011; Kerkhoff 2012a; Schroder 2008; Welfringer 2011). The average age of participants was over 60 years for most studies; it was just under 60 years in four studies (Kerkhoff 2012a; Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009; Polanowska 2009; Welfringer 2011). Three studies explicitly mentioned an age exclusion criterion: Robertson 2002 excluded participants who were aged over 80 years, Mizuno 2011 only included participants aged between 41 and 89 years, and Welfringer 2011 only included participants aged between 20 and 75 years. Many studies excluded participants on the basis of previous dementia or stroke, or current cognitive or communication problems, on the grounds that these would adversely affect responsiveness to therapy. In one study the neglect data were extracted from a larger study (Edmans 2000).

Interventions studied

A broad range of interventions were investigated (for full details see Characteristics of included studies). For 21 of the 23 included studies, the experimental intervention could be classified as either being a top‐down (12) or bottom‐up (9) rehabilitation approach. The remaining two were both classified as being a mix of top‐down and bottom‐up approaches.

Top‐down approaches

Twelve studies investigated the effect of top‐down approaches to rehabilitation (Cherney 2002; Cottam 1987; Edmans 2000; Fanthome 1995; Ferreira 2011; Kerkhoff 2012a; Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009; Robertson 1990; Rusconi 2002; Weinberg 1977; Welfringer 2011; Wiart 1997). The intervention included some sort of visual scanning training in seven studies (Cherney 2002; Cottam 1987; Ferreira 2011; Kerkhoff 2012a; Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009; Robertson 1990; Weinberg 1977); a form of feedback or cueing in four studies (Edmans 2000; Fanthome 1995; Rusconi 2002; Wiart 1997); and mental practice or imagery in two studies (Ferreira 2011; Welfringer 2011). Some approaches involved multiple strategies, for example in Wiart 1997 a therapist participated, actively guiding and giving feedback whilst the participant used the fitted pointer. Fanthome 1995 used specially adapted glasses which gave auditory feedback if the participant failed to scan the neglected side; Wiart 1997 fitted participants with a 'vest' with a metal pointer attached. Some interventions involved training with a therapist. For example, various scanning tasks were used to demonstrate the participant's deficit and show how a strategy could improve performance (Cherney 2002). A therapist was present in both arms of the Rusconi 2002 study but only provided cueing and feedback in the 'experimental' arm. This latter study is an example of cognitive rehabilitation versus an attention control, as participants in both arms received equal amounts of time/attention from a therapist. What differed was the nature of the therapy, i.e. whether or not cueing and feedback were provided by the therapist. In two studies both randomised treatment groups received a top‐down approach; Ferreira 2011 compared one group receiving a visual scanning intervention with another receiving mental practice, and Kerkhoff 2012a compared a group receiving optokinetic stimulation with another receiving standard visual scanning training. Both these studies were classified as comparisons of one cognitive rehabilitation approach versus another.

Bottom‐up approaches

Ten studies investigated the effect of bottom‐up approaches to rehabilitation (Fong 2007; Kalra 1997;Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009; Mizuno 2011; Nys 2008; Robertson 2002; Rossi 1990; Tsang 2009; Turton 2010; Zeloni 2002). Four of these studies investigated fitting prisms to spectacles in order to shift the image towards the neglected side (Mizuno 2011; Nys 2008; Rossi 1990; Turton 2010). Three studies investigated the effect of half‐field eye patching, using glasses or goggles (Fong 2007; Tsang 2009; Zeloni 2002). One study investigated a therapy‐directed intervention comprising spatio‐motor cueing aimed at integrating attention and limb movement (Kalra 1997), and another investigated an 'arm‐activation' intervention where the affected limb performed active arm exercises in the neglected part of space (Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009). The principle behind these approaches is that movements of the affected limb in the neglected part of space will result in improvements in attention skills and appreciation of spatial relationships on the affected side. Robertson 2002 provided a 'limb activation device' fitted to the wrist, leg or shoulder.

Mixed top‐down and bottom‐up approaches

Two of the 23 studies investigated interventions that comprised both top‐down and bottom‐up approaches to rehabilitation. Polanowska 2009 and Schroder 2008 both compared a visual scanning intervention (a top‐down approach) with a visual scanning intervention combined with a type of electrical stimulation (a bottom‐up approach). Both studies compared one cognitive rehabilitation approach with another. The group receiving the additional electrical stimulation was labelled the experimental group and the control was the group receiving visual scanning only (or visual scanning plus placebo electrical stimulation). Schroder 2008 included two experimental groups: one receiving visual scanning plus transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TENS) and one receiving visual scanning plus optokinetic stimulation (OKS). For analysis we have entered these as two studies (Schroder 2008 TENS and Schroder 2008 OKS) and have entered half the control group within each 'study'.

Comparison interventions

We classified 18 of the 23 studies as having a comparison of cognitive rehabilitation versus any other control (Cherney 2002; Cottam 1987; Edmans 2000; Fanthome 1995; Fong 2007; Kalra 1997; Mizuno 2011; Nys 2008; Robertson 1990; Robertson 2002; Rossi 1990; Rusconi 2002; Tsang 2009; Turton 2010; Weinberg 1977; Welfringer 2011; Wiart 1997; Zeloni 2002). Eleven of these 18 studies compared an experimental intervention with an attention control (Cherney 2002; Edmans 2000; Fong 2007; Kalra 1997; Mizuno 2011; Nys 2008; Robertson 1990; Robertson 2002; Rusconi 2002; Turton 2010; Wiart 1997). The remaining seven compared an experimental treatment with no treatment or standard care (Cottam 1987; Fanthome 1995; Rossi 1990; Tsang 2009; Weinberg 1977; Welfringer 2011; Zeloni 2002).

Five studies compared two different active treatments (Ferreira 2011; Kerkhoff 2012a; Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009; Polanowska 2009; Schroder 2008). We did consider that the 'arm‐activation' intervention investigated by Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009 could have been classified as an attention control. However, the dose of intervention given to this group was not the same as the dose given to the visual scanning intervention group (20 to 30 hours for the arm activation group and 10 hours for the visual scanning group). Furthermore, this intervention was considered to be based on principles of spatio‐motor cueing, where the affected limb is moved within the neglected part of space and this comparison intervention was therefore classified as a bottom‐up approach, and Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009 categorised as comparing one active cognitive rehabilitation intervention with another active cognitive rehabilitation intervention.

Dose of interventions

The nature of the interventions was usually well described, as were the number, frequency and duration of therapy sessions. The number of sessions varied from four (Nys 2008) to 40 (Rusconi 2002) over a duration of one to 12 weeks. Sessions ranged from daily to once a week and lasted from 30 to 75 minutes each. The Rossi 1990 study provided the highest 'dose' of rehabilitation as participants in the experimental arm wore their prisms during all daytime activities for four weeks.

Outcomes

Fifteen of the 23 included studies measured functional disability during activities of daily living, the primary outcome of interest. Five reported the Barthel Index (BI) (Edmans 2000; Kalra 1997; Robertson 2002; Rossi 1990; Rusconi 2002); four the Functional Indepedence Measure (FIM) (Ferreira 2011; Fong 2007; Tsang 2009; Wiart 1997) and one the Catherine Bergego scale (Turton 2010). Mizuno 2011 and Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009 assessed both the Catherine Bergego Scale and FIM; we used data for the Catherine Bergego Scale within meta‐analyses. Nys 2008 and Polanowska 2009 stated that the BI was administered but no useable data were provided. Similarly, one study used the Frenchay Activities Index but no data were available (Robertson 1990).

Only six studies reported ADL outcomes at follow‐up (persisting effects) (Ferreira 2011; Fong 2007; Mizuno 2011; Robertson 2002; Turton 2010; Wiart 1997). Mizuno 2011 recorded follow‐up at the time of hospital discharge, rather than at a set time following the end of the intervention.

Twenty‐two of the 23 included studies (all except Robertson 2002) reported a standardised assessment of neglect. One study reported discharge destination (Kalra 1997). In addition, one study reported that the Beck Depression Inventory was administered, but no data were provided post‐intervention (Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009); and one study reported the frequency of falls during the study period (Rossi 1990). No other relevant outcome data were reported i.e. balance, quality of life and social isolation, and adverse events (excluding falls).

Excluded studies

Thirty‐six studies are listed as excluded, with details provided in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

The original version of this review included 22 studies that were quasi‐randomised: these were removed from the review in the 2006 update and were listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Examples of non‐random methods were: allocating the first set to one arm and the second to the other (Rossetti 1998; Tham 1997); alternate allocation (Pizzamiglio 2004), allocating by bed number (Paolucci 1996), bed availability (Loverro 1988) or date of admission (Harvey 2003).

For this update, we have added a further 14 studies as excluded studies. The review authors discussed 12 of these in detail before they were excluded (Akinwuntan 2010; Bar‐Haim 2011; EEG‐NF 2009; Keller 2006; Kerkhoff 2012b; Koch 2012; Osawa 2010; Serino 2006; Serino 2009; Song 2009; Toglia 2009; Van Os 1991). One study was previously listed as ongoing (Kerkhoff 2005) and one previously listed as awaiting assessment (Cubelli 1993). The reasons for exclusion are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. The review authors particularly discussed Song 2009, which was a RCT of an intervention aimed at neglect in participants with stroke. However, the intervention studied was low‐frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), which the review authors agreed would be inappropriate to class as a cognitive rehabilitation approach. We initially decided, based on a published English abstract, to include Keller 2006. However, during appraisal of the full German version of the published study we ascertained that the study did not appear to be randomised, and we therefore excluded it.

Risk of bias in included studies

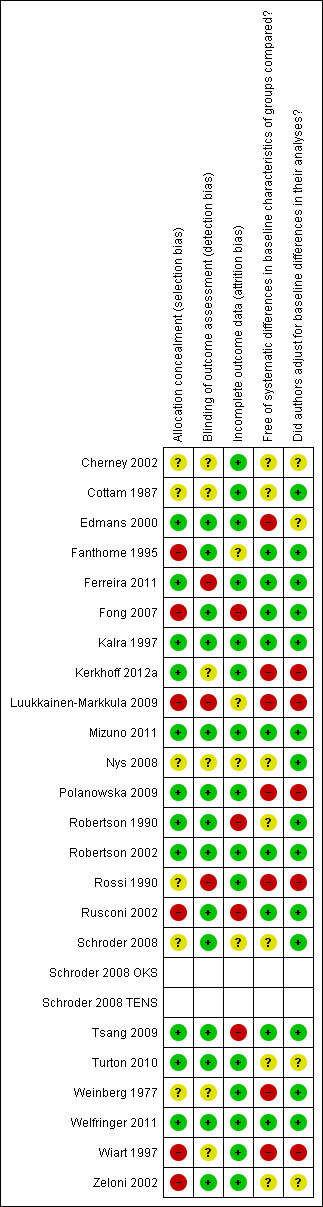

Information on risk of bias is provided in the Characteristics of included studies table and summarised in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

We assessed 11 of the included RCTs as having low risk of bias with adequate allocation concealment (Edmans 2000; Ferreira 2011; Kalra 1997; Kerkhoff 2012a; Mizuno 2011; Polanowska 2009; Robertson 1990; Robertson 2002; Tsang 2009; Turton 2010; Welfringer 2011). Six studies provided insufficient details to determine adequacy of allocation concealment (Cherney 2002; Cottam 1987; Nys 2008; Schroder 2008; Rossi 1990; Weinberg 1977) and six studies had methods of allocation concealment that we assessed to be at high risk of bias (Fanthome 1995; Fong 2007; Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009; Rusconi 2002; Wiart 1997; Zeloni 2002).

Blinding

We assessed 14 of the included RCTs to have adequate blinding of outcome assessor (Edmans 2000; Fanthome 1995; Fong 2007; Kalra 1997; Mizuno 2011; Polanowska 2009; Robertson 1990; Robertson 2002; Rusconi 2002; Schroder 2008; Tsang 2009; Turton 2010; Welfringer 2011; Zeloni 2002). This information was not provided for six studies (Cherney 2002; Cottam 1987; Kerkhoff 2012a; Nys 2008; Weinberg 1977; Wiart 1997) and three studies did not have a blinded outcome assessor (Ferreira 2011; Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009; Rossi 1990).

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed 15 of the included RCTs as having dealt appropriately with incomplete outcome data (Cherney 2002; Cottam 1987; Edmans 2000, Ferreira 2011; Kalra 1997; Kerkhoff 2012a; Mizuno 2011; Polanowska 2009; Robertson 2002; Rossi 1990; Turton 2010; Weinberg 1977; Welfringer 2011; Wiart 1997; Zeloni 2002. Four were assessed to be at high risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data (Fong 2007; Robertson 1990; Rusconi 2002; Tsang 2009), and insufficient information was available to assess four studies (Fanthome 1995; Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009; Nys 2008; Schroder 2008).

Other potential sources of bias

We assessed nine of the included RCTs to be free of systematic differences in baseline characteristics of the groups compared (Fanthome 1995; Ferreira 2011; Fong 2007; Kalra 1997; Mizuno 2011; Robertson 2002; Rusconi 2002; Tsang 2009; Welfringer 2011). Seven had some baseline differences (Edmans 2000; Kerkhoff 2012a; Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009; Polanowska 2009; Rossi 1990; Weinberg 1977; Wiart 1997) and for seven studies this information was not provided (Cherney 2002; Cottam 1987; Nys 2008; Robertson 1990; Schroder 2008; Turton 2010; Zeloni 2002).

We assessed 14 of the included RCTs to have made adequate adjustments for baseline differences or have no need for adjustment (Cottam 1987; Fanthome 1995; Ferreira 2011; Fong 2007; Kalra 1997; Mizuno 2011; Nys 2008; Robertson 1990; Robertson 2002; Rusconi 2002; Schroder 2008; Tsang 2009; Weinberg 1977; Welfringer 2011). Five had not made adequate adjustments (Kerkhoff 2012a; Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009; Polanowska 2009; Rossi 1990; Wiart 1997), and for four studies this information was not provided (Cherney 2002; Edmans 2000; Turton 2010; Zeloni 2002).

Originally we planned to assess whether or not studies were free from other sources of bias. However, we found this difficult, and could not agree on our assessment of risk of bias for this category so we removed it and used the Notes section in the Characteristics of included studies table for any other potential sources of bias. We considered Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009 to be at high risk of bias because of differences between the groups in the amount of intervention and standard therapy received.

Effects of interventions

We included 23 studies in this review, involving 628 participants. However, five studies did not compare cognitive rehabilitation with a control intervention, instead comparing two active cognitive rehabilitation interventions (Ferreira 2011; Kerkhoff 2012a; Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009; Polanowska 2009; Schroder 2008). Thus, we have included 18 studies in comparisons of a cognitive rehabilitation approach versus any control, and have included five studies in a comparison of one cognitive rehabilitation approach versus another.

For the comparisons of a cognitive rehabilitation approach versus any control we pooled data within analyses of:

measures of functional disability immediately after the end of rehabilitation or on discharge (10 studies, 343 participants);

measures of functional disability persisting over time (five studies, 143 participants);

standardised neglect assessments immediately after the end of rehabilitation or on discharge (16 studies, 437 participants);

standardised neglect assessments persisting over time (eight studies, 172 participants).

For each of these comparisons and outcomes we also completed various subgroup analyses; for example for the immediate effect on measures of functional disability we explored the type of control group (attention control or other/no‐treatment control). We also explored the type of rehabilitation approach (bottom‐up or top‐down) and the various types of bottom‐up and top‐down interventions. We completed sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of studies with adequate allocation concealment and adequate blinding only.

We included data for two additional outcomes within the comparison of cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: immediate effect. These were discharge destination (one study, 50 participants) and frequency of falls (one study, 39 participants).

For the comparison of one cognitive rehabilitation approach versus another we combined data within analyses of:

measures of functional disability immediately after the end of rehabilitation or on discharge (two studies, 21 participants);

measures of functional disability persisting over time (two studies, 22 participants);

standardised neglect assessments immediately after the end of rehabilitation or on discharge (five studies (six comparisons), 98 participants);

standardised neglect assessments persisting over time (four studies (five comparisons), 86 participants).

We calculated a standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) using a random‐effects model for all comparisons and outcomes, with the exception of discharge destination and frequency of falls when we calculated an odds ratio (OR).

Ratings on measures of functional disability

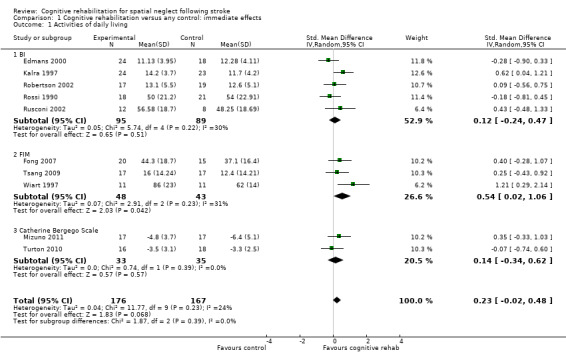

Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: immediate effects

For this comparison (versus any control), 10 studies (343 participants) provided usable data for a measure of disability immediately after the end of rehabilitation or on discharge, five with the BI (Edmans 2000; Kalra 1997; Robertson 2002; Rossi 1990; Rusconi 2002), three with the FIM (Fong 2007; Tsang 2009; Wiart 1997) and two with the Catherine Bergego scale (Mizuno 2011; Turton 2010). Two studies collected disability data but these were not available for the review (Robertson 1990: Frenchay Activities Index; Nys 2008: BI), and two others did not compare to a control (Ferreira 2011; Polanowska 2009).

Analyses demonstrated no statistically significant effect in favour of cognitive rehabilitation: SMD 0.23, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.48, heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.04; Chi² = 11.77, df = 9 (P = 0.23); I² = 24% (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: immediate effects, Outcome 1 Activities of daily living.

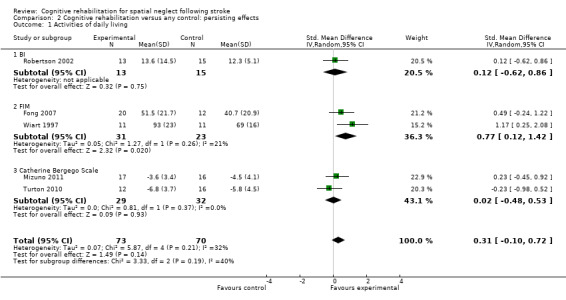

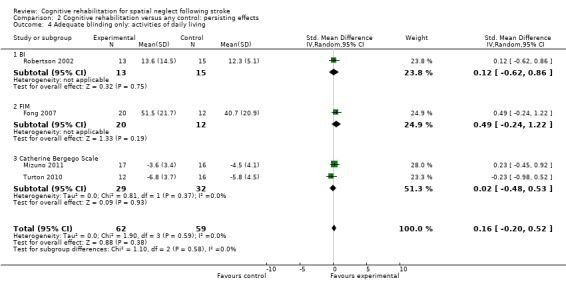

Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: persisting effects

For this comparison (versus any control) five studies (143 participants) provided data for a measure of disability persisting over time, one with the BI (Robertson 2002), two with the FIM (Fong 2007; Wiart 1997) and two with the Catherine Bergego Scale (Mizuno 2011; Turton 2010).

Analyses demonstrated no statistically significant effect of cognitive rehabilitation (SMD 0.31, 95% CI ‐0.10 to 0.72, heterogeneity: Chi² = 5.87, df = 4 (P = 0.21); I² = 32%) (Analysis 2.1). Subgroup analysis of the FIM data (two studies, 53 participants) showed a statistically significant effect in favour of cognitive rehabilitation (SMD 0.77, 95% CI 0.12 to 1.42, heterogeneity: Chi² = 1.27, df = 1 (P = 0.26); I² = 21%). However, the groups in Wiart 1997 were not well‐matched, with the experimental group being younger and having a higher baseline FIM score (66) than the control group (54). Outcomes assessed on the BI (Robertson 2002) and Catherine Bergego scale (Mizuno 2011; Turton 2010) favoured neither group.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: persisting effects, Outcome 1 Activities of daily living.

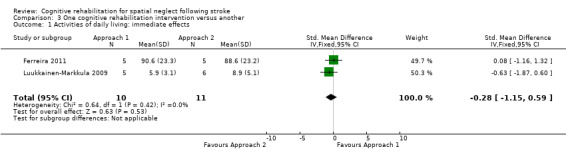

One cognitive rehabilitation intervention versus another: immediate effects

Two studies (21 participants) compared two active cognitive rehabilitation interventions and included an immediate measure of disability (Ferreira 2011; Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009). Ferreira 2011 compared the effect of visual scanning mental practice, measuring disability using the FIM. Both interventions are based on the top‐down processing approach. Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009 compared the effect of a top‐down processing approach (visual scanning) with a bottom‐up approach (arm activation), measuring disability using the Catherine Bergego Scale.

There was no significant different between the two interventions: SMD ‐0.28, 95% CI ‐1.15 to 0.59 (Analysis 3.1). Visual scanning was entered as Approach 1 for both studies.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 One cognitive rehabilitation intervention versus another, Outcome 1 Activities of daily living: immediate effects.

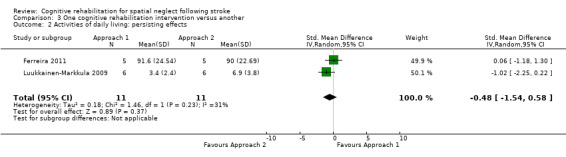

One cognitive rehabilitation intervention versus another: persisting effects

Two studies (22 participants) compared two active cognitive rehabilitation interventions and included a follow‐up measure of disability (Ferreira 2011; Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009) (see above for details).

There was no significant difference between the two interventions: SMD ‐0.48, 95% CI ‐1.54 to 0.58 (Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 One cognitive rehabilitation intervention versus another, Outcome 2 Activities of daily living: persisting effects.

Subgroup analyses

Type of control: immediate effects

Eight of the studies (170 participants) that measured disability immediately after the intervention phase had an attention control group (Edmans 2000; Fong 2007; Kalra 1997; Mizuno 2011; Robertson 2002; Rusconi 2002; Turton 2010; Wiart 1997), while two (73 participants) had a no‐treatment or non‐attention control (Rossi 1990; Tsang 2009).Tests for subgroup differences demonstrated no evidence of statistically significant differences between the groups with or without an attention control (P = 0.33) (Analysis 1.9).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: immediate effects, Outcome 9 Type of control: activities of daily living.

Type of control: persisting effects

We planned to explore the effect of the type of control (attention control versus no treatment or standard care) for measures of disability persisting over time. However, all of the five studies (Fong 2007; Mizuno 2011; Robertson 2002; Turton 2010; Wiart 1997) included in Comparison 2.1 (cognitive rehabilitation versus any control for measures of disability persisting over time) had an attention control, so further subgroup analysis was not required (Analysis 2.1).

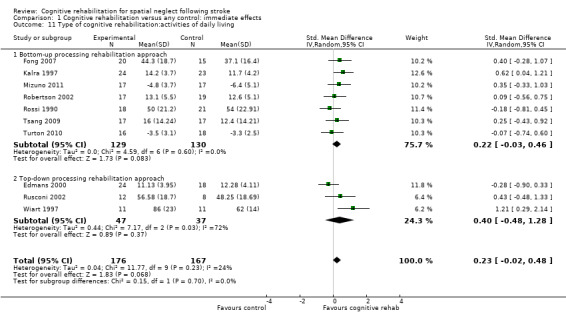

Type of rehabilitation approach: immediate effects

Seven studies of bottom‐up approaches (259 participants) and three studies of top‐down approaches (84 participants) included a measure of disability immediately at the end of rehabilitation. Test for subgroup differences demonstrated no evidence of statistically significant differences between the group comparing bottom‐up approaches with control and the group comparing top‐down approaches with control (P = 0.70) (Analysis 1.11).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: immediate effects, Outcome 11 Type of cognitive rehabilitation:activities of daily living.

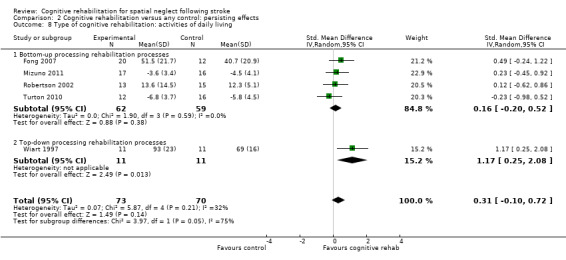

Type of rehabilitation approach: persisting effects

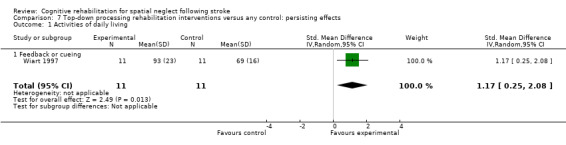

Four studies of bottom‐up approaches (121 participants) and one study of a top‐down approach (22 participants) included a measure of disability persisting over time. Tests for subgroup differences between bottom‐up and top‐down interventions approached statistical significance (P = 0.05). There were no significant differences between bottom‐up approaches and control: SMD 0.16, 95% CI ‐0.20 to 0.52 (Analysis 2.8.1). A statistically significant effect in favour of the single top‐down approach was found (SMD 1.17, 95% CI 0.25 to 2.08). However, there were baseline differences between groups in this study.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: persisting effects, Outcome 8 Type of cognitive rehabilitation: activities of daily living.

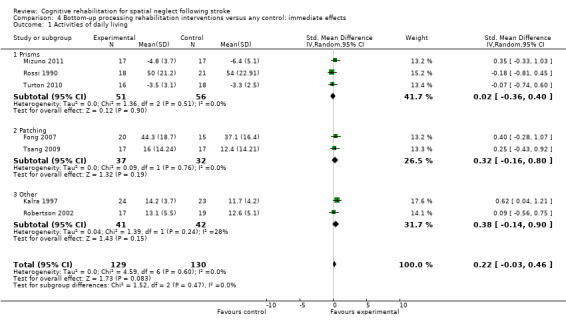

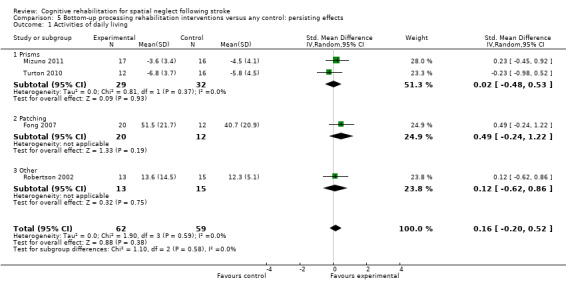

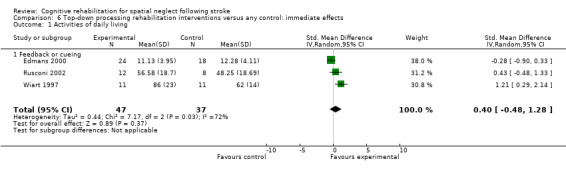

Types of rehabilitation interventions (Comparisons 4.1, 5.1, 6.1 and 7.1)

Comparison 4.1 explores the effects of different types of bottom‐up interventions (e.g. prisms, eye‐patching) on immediate effects of disability (Analysis 4.1), and Comparison 5.1 the effects on persisting effects of disability (Analysis 5.1). Comparison 6.1 explores the effects of different types of top‐down interventions (e.g. feedback, visual scanning training) on immediate effects of disability (Analysis 6.1), and Comparison 7.1 the effects of persisting effects of disability (Analysis 7.1). These analyses demonstrated no evidence of any significant differences between any of the subgroups (P > 0.05).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Bottom‐up processing rehabilitation interventions versus any control: immediate effects, Outcome 1 Activities of daily living.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Bottom‐up processing rehabilitation interventions versus any control: persisting effects, Outcome 1 Activities of daily living.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Top‐down processing rehabilitation interventions versus any control: immediate effects, Outcome 1 Activities of daily living.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Top‐down processing rehabilitation interventions versus any control: persisting effects, Outcome 1 Activities of daily living.

Sensitivity analyses

We carried out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of high or unclear risk of bias due to inadequate allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessor on the activities of daily living (ADL) outcome.

Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: adequate allocation concealment only

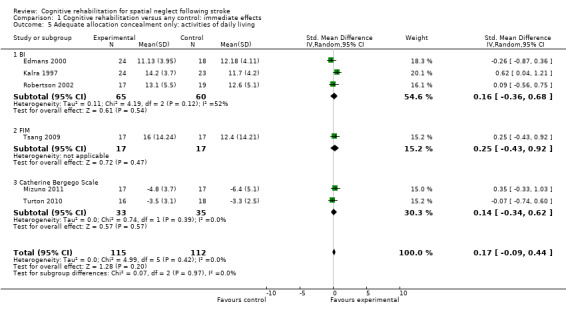

For immediate effect on ADL: including only the six out of 11 studies that clearly had adequate allocation concealment (low risk of bias) removed the significant effect that was found when including all studies (Comparison 1.1): SMD 0.17, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.44, heterogeneity: Chi² = 4.99, df = 5 (P = 0.42); I² = 0% (Analysis 1.5). The significant effect on the FIM was no longer present, with only one study that measured the FIM having adequate allocation concealment (Tsang 2009).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: immediate effects, Outcome 5 Adequate allocation concealment only: activities of daily living.

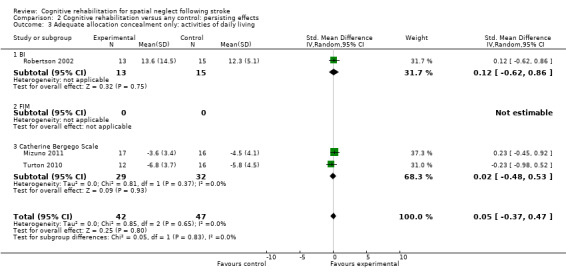

For persisting effect on ADL: only three of the five studies had adequate allocation concealment so a sensitivity analysis including only these studies resulted in a reduced effect size and reduced heterogeneity but did not alter the overall result of no significant effect (SMD 0.05, 95% CI ‐0.37 to 0.47, heterogeneity: Chi² = 0.85, df = 2 (P = 0.65); I² = 0%) (Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: persisting effects, Outcome 3 Adequate allocation concealment only: activities of daily living.

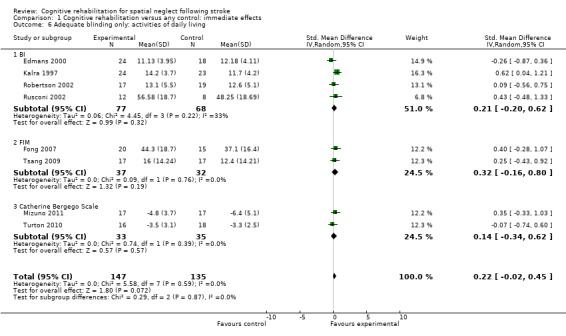

Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: adequate blinding only

For immediate effect on ADL: including only the eight of 11 studies with blinded outcome assessor (low risk of bias) removed the significant effect which was found when including all studies (Comparison 1.1): SMD 0.22, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.45, heterogeneity: Chi² = 5.58, df = 7 (P = 0.59); I² = 0% (Analysis 1.6). The significant effect on the FIM was no longer present, but only two studies which used the FIM had blinded outcome assessment (Fong 2007; Tsang 2009).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: immediate effects, Outcome 6 Adequate blinding only: activities of daily living.

For persisting effect on ADL: including only studies with blinded outcome assessor removed one study from the analysis (Wiart 1997); this did not alter the overall result of no significant effect (SMD 0.16, 95% CI ‐0.20 to 0.52, heterogeneity: Chi² = 1.90, df = 3 (P = 0.59); I² = 0%) (Analysis 2.4) but did remove the significant effect of the FIM.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: persisting effects, Outcome 4 Adequate blinding only: activities of daily living.

Performance on standardised neglect assessments

All except one of the 23 included studies (Robertson 2002) provided data on standardised tests of neglect that were suitable for inclusion, although there was no one measure common to all studies and some used more than one measure. We used a pre‐specified hierarchical system to select one neglect test outcome from each study. Thus 19 of the 20 studies comparing cognitive rehabilitation versus any control and all three studies comparing one cognitive rehabilitation approach with another have data pooled in meta‐analyses. Two studies provided data at follow‐up but not immediately after treatment (Cottam 1987; Fanthome 1995), and many reported immediate but not persisting effects (detailed below).

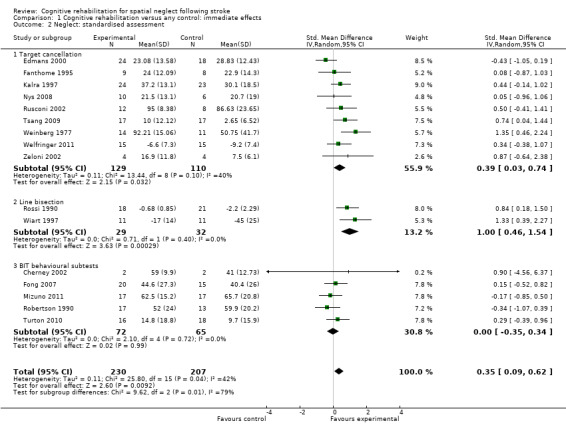

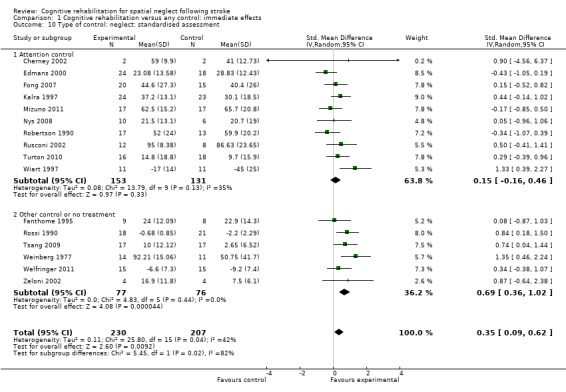

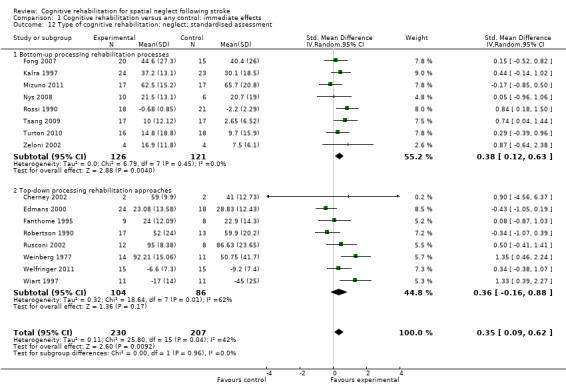

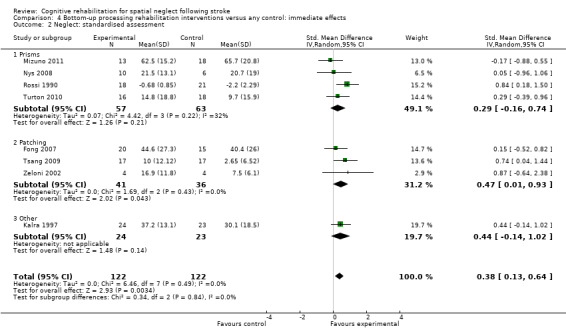

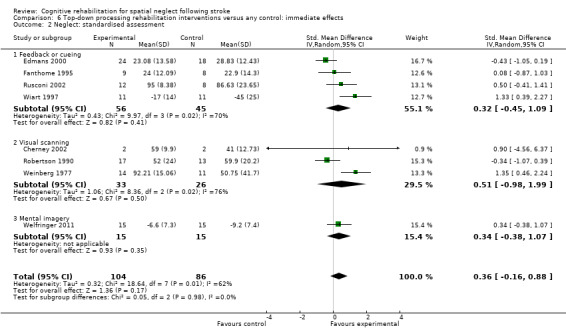

Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: immediate effects

Sixteen studies (437 participants) included standardised neglect assessment data for the immediate effect of a comparison of cognitive rehabilitation versus any control. Nine studies had measures of target cancellation (Edmans 2000; Fanthome 1995; Kalra 1997; Nys 2008; Rusconi 2002; Tsang 2009; Weinberg 1977; Welfringer 2011; Zeloni 2002); two had measures of line bisection (Rossi 1990; Wiart 1997); and five had measures of BIT behavioural subtests (Cherney 2002; Fong 2007; Mizuno 2011; Robertson 1990; Turton 2010).

The combined analysis found a significant effect in favour of cognitive rehabilitation (SMD 0.35, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.62, heterogeneity: Chi² = 25.80, df = 15 (P = 0.04); I² = 42%) (Analysis 1.2). There was a statistically significant effect in favour of cognitive rehabilitation for the nine studies using cancellation tests (SMD 0.39, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.74, heterogeneity: Chi² = 13.44, df = 8 (P = 0.10); I² = 40%) and two studies using line bisection (SMD 1.00, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.54, heterogeneity: Chi² = 0.71, df = 1 (P = 0.40); I² = 0%) but not for the studies using the BIT.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: immediate effects, Outcome 2 Neglect: standardised assessment.

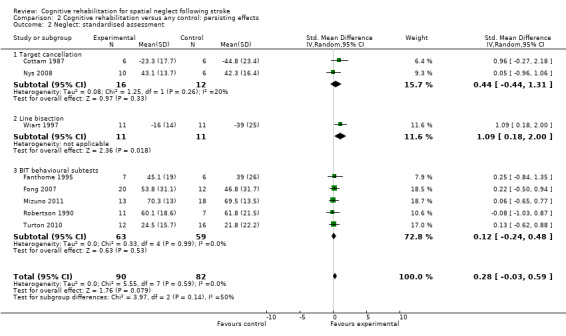

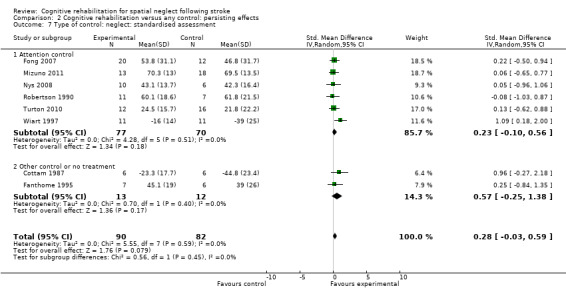

Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: persisting effects

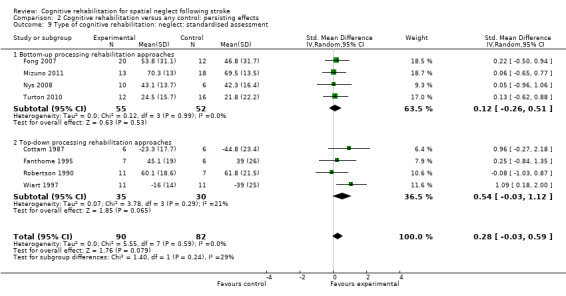

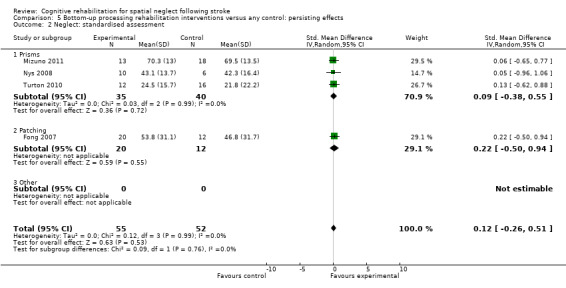

Eight of the studies (172 participants) included standardised neglect assessment data for the persisting effect of a comparison of cognitive rehabilitation versus any control. One study had a measure of star cancellation (Nys 2008); one had line bisection (Wiart 1997), and five provided the BIT behavioural subscale (Fanthome 1995; Fong 2007; Mizuno 2011; Robertson 1990; Turton 2010). In addition, one study (Cottam 1987) reported the number of errors during cancellation: as this was the only neglect measure for this study it was entered as a cancellation outcome (with data multiplied by ‐1 to ensure direction of effect was consistent with other outcomes).

The combined analysis found no significant effect of cognitive rehabilitation (SMD 0.28, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.59, with no heterogeneity (Chi² = 5.55, df = 7 (P = 0.59); I² = 0%)) (Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: persisting effects, Outcome 2 Neglect: standardised assessment.

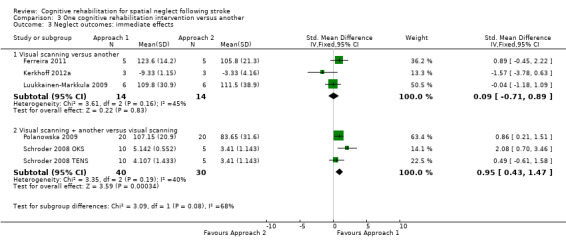

One cognitive rehabilitation intervention versus another: immediate effect

Five studies comparing different cognitive rehabilitation interventions reported neglect test outcomes (Ferreira 2011; Kerkhoff 2012a; Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009; Polanowska 2009; Schroder 2008). Three of the studies compared visual scanning training with another cognitive rehabilitation intervention; the other interventions comprised a top‐down approach (mental practice) for Ferreira 2011, and a bottom‐up approach for Kerkhoff 2012a (optokinetic stimulation, OKS) and Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009 (arm activation). For each of these studies the visual scanning training was entered as Approach 1 and the other intervention as Approach 2. Pooling data within this subgroup demonstrated no statistically significant differences between Approach 1 and Approach 2 (SMD 0.09, 95% CI ‐0.71 to 0.89, heterogeneity: Chi² = 3.61, df = 2 (P = 0.16); I² = 45%) (Analysis 3.3).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 One cognitive rehabilitation intervention versus another, Outcome 3 Neglect outcomes: immediate effects.

The other two studies investigated the addition of other interventions to visual scanning training. Schroder 2008 compared visual scanning training with the addition of either transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) or OKS. We have entered these as Schroder 2008 OKS and Schroder 2008 TENS and we have entered the OKS and TENS groups as Approach 1 and the control visual scanning training intervention as Approach 2. Polanowska 2009 compared visual scanning training plus electrical somatosensory stimulation (Approach 1) with visual scanning training plus placebo electrical stimulation (Approach 2). Pooling data within this subgroup demonstrated a statistically significant effect in favour of Approach 1 (SMD 0.95, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.47, heterogeneity: Chi² = 3.35, df = 2 (P = 0.19); I² = 40%) (Analysis 3.3.2), suggesting that a combination of visual scanning training plus bottom‐up interventions such as OKS or electrical stimulation may have added benefit. However, there is considerable heterogeneity.

One cognitive rehabilitation intervention versus another: persisting effects

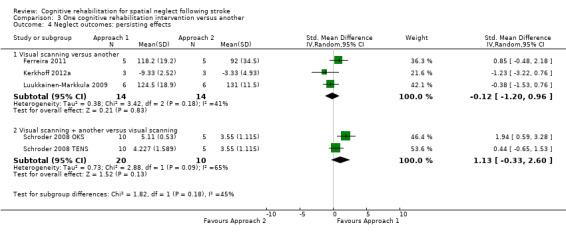

Four of the five studies comparing different cognitive rehabilitation interventions (see descriptions in preceding paragraphs) reported persisting neglect test outcomes (Ferreira 2011; Kerkhoff 2012a; Luukkainen‐Markkula 2009; Schroder 2008). No statistically significant effect in favour of either Approach 1 or 2 was found, for either the subgroup comparing a visual scanning intervention with another cognitive rehabilitation intervention (SMD ‐0.12, 95% CI ‐1.20 to 0.96) or for the subgroup comparing a visual scanning intervention plus another cognitive rehabilitation intervention with a visual scanning intervention alone (SMD 1.13, 95% CI ‐0.33 to 2.60) (Analysis 3.4). There was considerable heterogeneity within these subgroup analyses (heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.38; Chi² = 3.42, df = 2 (P = 0.18); I² = 41% and Tau² = 0.73; Chi² = 2.88, df = 1 (P = 0.09); I² = 65% respectively).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 One cognitive rehabilitation intervention versus another, Outcome 4 Neglect outcomes: persisting effects.

Subgroup analyses

Type of control: immediate effects

Ten of the studies (284 participants) that measured immediate effect on neglect tests had an attention control group (Cherney 2002; Edmans 2000; Fong 2007; Kalra 1997; Mizuno 2011; Nys 2008; Robertson 1990; Rusconi 2002; Turton 2010; Wiart 1997), while six (153 participants) had a no‐treatment or non‐attention control (Fanthome 1995; Rossi 1990; Tsang 2009; Weinberg 1977; Welfringer 2011; Zeloni 2002). Testing for subgroup differences demonstrated some evidence of a statistically significant difference between the group with an attention control group and the group without (P = 0.04). There was no statistically significant effect in favour of cognitive rehabilitation (SMD 0.15, 95% CI ‐0.16 to 0.46) for the studies with an attention control, but there was a statistically significant effect for the studies without an attention control (SMD 0.69, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.02) (Analysis 1.10).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: immediate effects, Outcome 10 Type of control: neglect: standardised assessment.

Type of control: persisting effects

Six of the studies (147 participants) that measured persisting effect on neglect tests had an attention control group (Fong 2007; Mizuno 2011; Nys 2008; Robertson 1990; Turton 2010; Wiart 1997), while two (25 participants) had a no‐treatment or non‐attention control (Cottam 1987; Fanthome 1995). Tests for subgroup differences demonstrated that there were no statistically significant differences between the groups with or without an attention control (P = 0.45) (Analysis 2.7).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: persisting effects, Outcome 7 Type of control: neglect: standardised assessment.

Type of rehabilitation approach: immediate effects

Eight studies of bottom‐up approaches (244 participants) and eight studies of top‐down approaches (190 participants) included a standardised neglect assessment immediately at the end of rehabilitation. Tests for subgroup differences demonstrated that there were no statistically significant differences between the group comparing bottom‐up approaches with control and the group comparing top‐down approaches with control (P = 0.96) (Analysis 1.12).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: immediate effects, Outcome 12 Type of cognitive rehabilitation: neglect: standardised assessment.

Type of rehabilitation approach: persisting effects

Four studies of bottom‐up approaches (107 participants) and four studies of top‐down approaches (65 participants) included a standardised neglect assessment persisting over time. Tests for subgroup differences demonstrated that there were no statistically significant differences between the group comparing bottom‐up approaches with control and the group comparing top‐down approaches with control (P = 0.24) (Analysis 2.9).

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: persisting effects, Outcome 9 Type of cognitive rehabilitation: neglect: standardised assessment.

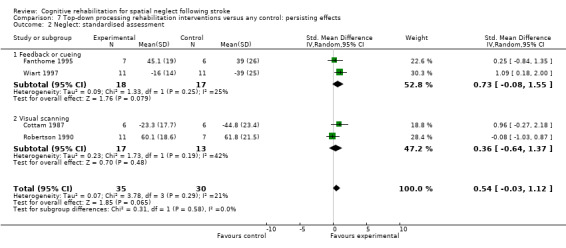

Types of rehabilitation interventions

Comparison 4.2 explores the effects of different types of bottom‐up interventions (e.g. prisms, eye‐patching) on immediate effects on neglect outcomes (Analysis 4.2), and Comparison 5.2 the effects on persisting effects on neglect (Analysis 5.2). Comparison 6.2 explores the effects of different types of top‐down interventions (feedback, visual scanning training) on immediate effects on neglect outcomes (Analysis 6.2), and Comparison 7.2 the effects of persisting effects on neglect outcomes (Analysis 7.2). These analyses demonstrated no evidence of significant differences between any of the subgroups (P > 0.05).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Bottom‐up processing rehabilitation interventions versus any control: immediate effects, Outcome 2 Neglect: standardised assessment.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Bottom‐up processing rehabilitation interventions versus any control: persisting effects, Outcome 2 Neglect: standardised assessment.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Top‐down processing rehabilitation interventions versus any control: immediate effects, Outcome 2 Neglect: standardised assessment.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Top‐down processing rehabilitation interventions versus any control: persisting effects, Outcome 2 Neglect: standardised assessment.

Sensitivity analyses

We carried out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of high or unclear risk of bias due to inadequate allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessor on the neglect test outcomes.

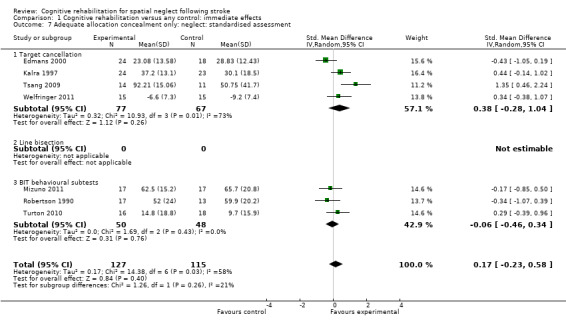

Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: adequate allocation concealment only

For immediate effect on neglect: including only studies that clearly had adequate allocation concealment (low risk of bias) resulted in an analysis of seven studies (242 participants). The results of the analysis changed from showing an effect in favour of cognitive rehabilitation to showing no effect of cognitive rehabilitation (SMD 0.17, 95% CI ‐0.23 to 0.58). There was substantial heterogeneity: Chi² = 14.38, df = 6 (P = 0.03); I² = 58% (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: immediate effects, Outcome 7 Adequate allocation concealment only: neglect: standardised assessment.

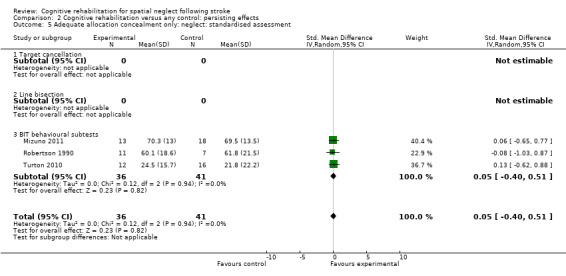

For persisting effect on neglect: only three studies (77 participants) with data had adequate allocation concealment; there remained no effect of cognitive rehabilitation (SMD 0.05, 95% CI ‐0.40 to 0.51, heterogeneity: Chi² = 0.12, df = 2 (P = 0.94); I² = 0%) (Analysis 2.5).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: persisting effects, Outcome 5 Adequate allocation concealment only: neglect: standardised assessment.

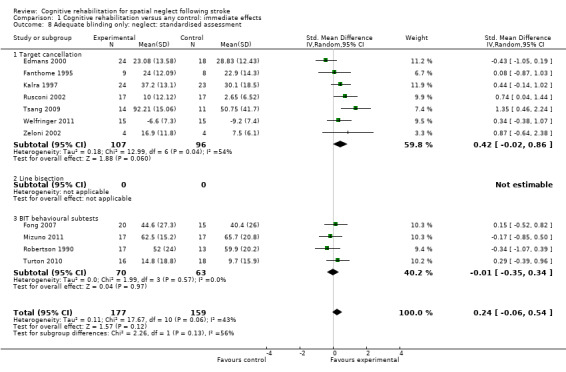

Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: adequate blinding only

For immediate effect on neglect: including only studies with blinded outcome assessors resulted in an analysis including 11 studies (336 participants), changing the result from showing an effect in favour of cognitive rehabilitation to showing no effect of cognitive rehabilitation (SMD 0.24, 95% CI ‐0.06 to 0.54, heterogeneity: Chi² = 17.67, df = 10 (P = 0.06); I² = 43%) (Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: immediate effects, Outcome 8 Adequate blinding only: neglect: standardised assessment.

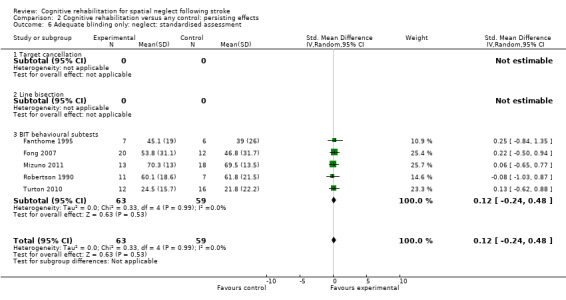

For persisting effect on neglect: including only studies with blinded outcome assessors included four studies (122 participants); there remained no effect of cognitive rehabilitation (SMD 0.12, 95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.48, heterogeneity: Chi² = 0.33, df = 4 (P = 0.99); I² = 0%) (Analysis 2.6).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: persisting effects, Outcome 6 Adequate blinding only: neglect: standardised assessment.

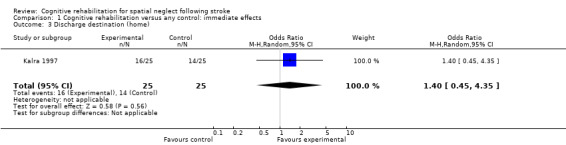

Discharge destination

Only one RCT (50 participants), assessed as being at low risk of bias for allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessment, investigated discharge destination as an outcome (Kalra 1997). The odds of being discharged home were not significantly higher for the experimental group (OR 1.40, 95% CI 0.45 to 4.35, P = 0.56) (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cognitive rehabilitation versus any control: immediate effects, Outcome 3 Discharge destination (home).

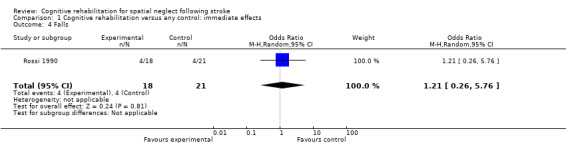

Falls