Abstract

Background

Terminally ill people experience a variety of symptoms in the last hours and days of life, including delirium, agitation, anxiety, terminal restlessness, dyspnoea, pain, vomiting, and psychological and physical distress. In the terminal phase of life, these symptoms may become refractory, and unable to be controlled by supportive and palliative therapies specifically targeted to these symptoms. Palliative sedation therapy is one potential solution to providing relief from these refractory symptoms. Sedation in terminally ill people is intended to provide relief from refractory symptoms that are not controlled by other methods. Sedative drugs such as benzodiazepines are titrated to achieve the desired level of sedation; the level of sedation can be easily maintained and the effect is reversible.

Objectives

To assess the evidence for the benefit of palliative pharmacological sedation on quality of life, survival, and specific refractory symptoms in terminally ill adults during their last few days of life.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2014, Issue 11), MEDLINE (1946 to November 2014), and EMBASE (1974 to December 2014), using search terms representing the sedative drug names and classes, disease stage, and study designs.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐RCTs, non‐RCTs, and observational studies (e.g. before‐and‐after, interrupted‐time‐series) with quantitative outcomes. We excluded studies with only qualitative outcomes or that had no comparison (i.e. no control group or no within‐group comparison) (e.g. single arm case series).

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened titles and abstracts of citations, and full text of potentially eligible studies. Two review authors independently carried out data extraction using standard data extraction forms. A third review author acted as arbiter for both stages. We carried out no meta‐analyses due to insufficient data for pooling on any outcome; therefore, we reported outcomes narratively.

Main results

The searches resulted in 14 included studies, involving 4167 adults, of whom 1137 received palliative sedation. More than 95% of people had cancer. No studies were randomised or quasi‐randomised. All were consecutive case series, with only three having prospective data collection. Risk of bias was high, due to lack of randomisation. No studies measured quality of life or participant well‐being, which was the primary outcome of the review. Five studies measured symptom control, using four different methods, so pooling was not possible. The results demonstrated that despite sedation, delirium and dyspnoea were still troublesome symptoms in these people in the last few days of life. Control of other symptoms appeared to be similar in sedated and non‐sedated people. Only one study measured unintended adverse effects of sedative drugs and found no major events; however, four of 70 participants appeared to have drug‐induced delirium. The study noticed no respiratory suppression. Thirteen of the 14 studies measured survival time from admission or referral to death, and all demonstrated no statistically significant difference between sedated and non‐sedated groups.

Authors' conclusions

There was insufficient evidence about the efficacy of palliative sedation in terms of a person's quality of life or symptom control. There was evidence that palliative sedation did not hasten death, which has been a concern of physicians and families in prescribing this treatment. However, this evidence comes from low quality studies, so should be interpreted with caution. Further studies that specifically measure the efficacy and quality of life in sedated people, compared with non‐sedated people, and quantify adverse effects are required.

Plain language summary

Sedation medication for relieving symptoms at the end of life

Background

People with diseases that are not curable may have a variety of symptoms at the end of life. These symptoms can include confusion (delirium), anxiety, restlessness, breathlessness (dyspnoea), pain, vomiting, and distress. Medicines that reduce consciousness (sedatives) may help relieve these symptoms when people are close to death.

Treatment with sedatives can vary in terms of the level of sedation (mild, intermediate, and deep), and duration (intermittent or continuous).

Study chara cteristics

We searched international databases in October 2012 and again in December 2014 for studies of terminally ill adults who required sedation in order to control symptoms. We found 14 studies of around 4000 people. The studies compared sedation versus non‐sedation. Most people in the studies had cancer (95%). The studies took place in hospices, palliative care units, hospitals, and the home.

Key results

Five studies showed that sedatives did not fully relieve delirium or breathlessness. There was no difference between the groups in terms of the other symptoms. There was no difference in time from admission or referral to death

Only one study reported side effects, and did not report any major problems.

Future studies should focus on how sedatives affect a person's quality of life, or peacefulness and comfort during the dying phase, and how well sedation controls the distressing symptoms. Side effects should be better reported.

Quality of evidence

The studies were not randomised controlled trials (where people are randomly allocated to one of two or more treatment groups), and so we judged the quality of the evidence as poor.

Background

Description of the condition

Terminally ill people experience a variety of symptoms in the last hours and days of life, including delirium, agitation, anxiety, terminal restlessness, dyspnoea, pain, vomiting, and psychological and physical distress. Terminal restlessness is an agitated delirium that occurs in some people during the last few days of life (Doyle 2008). The Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT) indicated that during their last three days of life, 80% of dying hospitalised people had severe fatigue, 50% severe dyspnoea, and 40% severe pain (Lynn 1997). In another study, the most commonly reported symptoms were fatigue, dyspnoea, and dry mouth, with the most distressing being fatigue, dyspnoea, and pain (Hickman 2001). Other distressing symptoms reported in this and other similar studies were noisy breathing, excess respiratory secretions, agitation, anxiety, constipation, nausea and vomiting, anorexia, incontinence, pressure sores, and insomnia (e.g. Cowan 2006; Morita 2005).

In the terminal phase of life (i.e. when the disease is progressive, far advanced, incurable, and death is imminent), these symptoms may become refractory, unable to be controlled by supportive and palliative therapies specifically targeted to these symptoms. Palliative sedation therapy is one potential solution to providing relief from these refractory symptoms.

Description of the intervention

Palliative sedation therapy has been described as "the use of sedative medications to relieve intolerable suffering from refractory symptoms by a reduction in patient consciousness" (De Graeff 2007). The therapy can vary in terms of level of sedation (mild, intermediate, and deep), and duration (intermittent or continuous). Sedation can be achieved by drugs that are primarily sedatives, and are not designed to treat the underlying condition or symptom, or by drugs that have some effect on the underlying symptom and have a secondary effect of causing somnolence.

Drug classes used for palliative sedation include benzodiazepines (particularly midazolam and clonazepam), antipsychotics, opioids, and hypnotics. They may be administered intravenously or subcutaneously.

How the intervention might work

Sedation in terminally ill people in the last hours or days of life is intended to provide relief from refractory symptoms that are not controlled by other methods. Sedative drugs such as benzodiazepines are titrated to achieve the desired level of sedation, and potentially the desired level of symptom control; the level of sedation can be easily maintained and the effect is reversible. Therefore, sedation may be useful in terminally ill people where symptom control cannot be achieved by drugs targeted at the specific symptom. There is also some concern as to whether this form of treatment may shorten life, and could be used to hasten death intentionally, similarly to euthanasia, so assessing the effects on survival is important.

Why it is important to do this review

There are existing Cochrane reviews on interventions for particular symptoms (e.g. interventions for noisy breathing in people near to death (Wee 2008), opioids for palliation of breathlessness (Jennings 2001), drug therapy for delirium in terminally ill people (Jackson 2004a), benzodiazepines and related drugs for insomnia in palliative care (Hirst 2009), and anxiety in palliative care (Jackson 2004b)), and one systematic review of one drug (propofol) for terminal sedation (McWilliams 2010). One systematic review was published after the commencement of this review (Maltoni 2012a), which reports on most of the studies included in this review. The focus of the review was survival. Our review aimed to bring together in one place the limited information on all drugs used to sedate terminally ill people, for all symptoms, specifically in the terminal phase of life, as distinct from the broader palliative care setting.

Objectives

To assess the evidence for the benefit of palliative pharmacological sedation on quality of life, survival and specific refractory symptoms in terminally ill adults during their last few days of life.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐RCTs, non‐RCTs, and observational studies (e.g. before‐and‐after, interrupted‐time‐series) with quantitative outcomes. We made this choice because we knew prior to starting the review that there would be few, if any, RCTs in this area. We excluded studies with only qualitative outcomes or that had no comparison (i.e. no control group or no within‐group comparison) (e.g. single arm case series).

Types of participants

We included studies of terminally ill adults (aged 15 years or greater) who required sedation in order to control symptom(s) (e.g. agitation, anxiety, insomnia, terminal restlessness, dyspnoea, and pain). We considered all terminal conditions (malignant and non‐malignant), in all settings (e.g. home, hospital, and palliative care institution).

Types of interventions

Any medication with a sedative effect (e.g. benzodiazepines, barbiturates, anaesthesia, opioids, antipsychotics, antihistamines, or other hypnotics) where the intention was sedation for symptom relief. Sedation may have been given continuously or intermittently, with the intention of reducing the level of consciousness to relieve symptoms. Sedation may have been deep (unconscious) or the person may have had periods when they were drowsy, but not unconscious. The comparator was no sedation. Sedative medications may have been given in very low doses (e.g. for sleep at night), but the intention was not to sedate to relieve intractable symptoms.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Quality of life or a person's well‐being. This would usually be measured by a proxy (e.g. doctor, nurse, carer), but in certain circumstances may have been measured by the person during periods of adequate consciousness. We used the term 'quality of life' to represent any domain related to the quality of the person's experience during the dying phase. This may have included peacefulness or comfort, carer's satisfaction with the person's experience, or a multi‐dimensional assessment of symptom control affecting quality of life, for example.

Secondary outcomes

Control of specific symptom(s) (e.g. agitation, anxiety, insomnia, terminal restlessness, dyspnoea, and pain).

Duration of symptom control.

Time to control of symptoms.

Adverse effects of treatment. For example, for antipsychotics these may include: worse drowsiness than intended, extrapyramidal effects, akathisia (restlessness), antipsychotic malignant syndrome, urinary retention, and constipation; and for benzodiazepines: drowsiness, ataxia, confusion, falls, increased restlessness, respiratory depression, and hypotension.

Duration of institutional care.

Time to death.

Carer satisfaction.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases:

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2014, Issue 11);

MEDLINE (Ovid) (1946 to November 2014);

EMBASE (Ovid) (1974 to December 2014).

Appendix 1 shows the search strategies. We applied no language or date restrictions.

We also searched clinical trials registries (ClinicalTrials.gov; the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch/)) in October 2012 and again in December 2014 to find any ongoing trials or to locate other publications that might not have been found in the database searches.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of relevant textbooks, review articles, and relevant studies.

We wrote to investigators known to be involved in previous studies, seeking information about unpublished or incomplete trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We used the search strategy described to obtain titles and abstracts of studies that may be relevant to the review. Two review authors (EB, MvD) independently screened the titles and abstracts, and discarded studies that were not applicable; however, we initially retained studies and reviews that might have included relevant data or information on studies.

Two review authors (EB, MvD) independently assessed the retrieved full‐text of these studies to determine which studies satisfied the inclusion criteria. A third review author was to act as arbiter if needed (GM).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (LM, ST) independently carried out data extraction using standard data extraction forms. We translated studies reported in non‐English language journals before assessment. Where more than one publication of one study existed, we grouped reports together and we used the publication with the most complete data in the analyses. Where relevant outcomes were only published in earlier versions, we used these data as well. We highlighted any discrepancy between published versions. A third review author (EB) acted as arbiter. One review author (EB) used Review Manager 5 software to enter data, which we would have used to perform meta‐analyses (RevMan 2014).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For RCTs, two review authors (LM, ST) independently assessed the following items using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2011). A third review author (EB) acted as arbiter.

Adequate sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting (reporting bias).

Other bias.

For non‐randomised, comparative trials, the first and second criteria were set to 'high risk of bias'. We included two additional criteria to assess selection bias in non‐randomised studies:

were baseline characteristics similar?

were baseline outcome measurements similar?

This follows the recommendations of the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) review group for assessing risk of bias in non‐randomised studies. For future updates of this review, we plan to use the Cochrane ACROBAT‐NRSi tool (Sterne 2014).

We assessed each of these criteria as low risk of bias, unclear risk of bias, or high risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Primary outcomes

Quality of life or a person's well‐being

We anticipated that studies would measure quality of life or a person's well‐being on a recognised quality of life continuous scale. Since there are many quality of life scales, we planned to use the standardised mean difference (SMD) (with standard deviation) between the intervention and control groups to include all comparative studies with a quality of life scale or well‐being scale as outcome. However, no included studies measured the primary outcome.

Secondary outcomes

Symptom control

Where studies reported symptom control on a continuous scale, we planned to use SMD (with 95% confidence interval (CI)) to combine them in a similar method to the primary outcome.

Where studies reported symptom control on a dichotomous scale (e.g. relief versus no relief), we planned to combine these studies using risk ratio (RR) in the intervention group compared with control (with 95% CI).

If data were reported using a short ordinal scale (e.g. no relief, some relief, moderate relief, good relief), we planned to combine the moderate and good relief categories, and the none and mild categories and include these with the dichotomous outcome studies.

Adverse effects of treatment

We planned to use the proportion of participants experiencing any adverse effect of treatment, and combine studies using RR (and 95% CI).

Duration of symptom control, time to control of symptoms, duration of institutional care, and time to death

If there had been sufficient studies to meta‐analyse duration of symptom control, time to control of symptoms, duration of institutional care, and time to death, we intended to use the generic inverse variance method to pool hazard ratios (Higgins 2011).

Carer satisfaction

We planned to pool studies where carer satisfaction was reported on a continuous scale by calculating the standardised mean difference (SMD) with standard deviation (SD).

Unit of analysis issues

We thought it unlikely that any studies would utilise a cluster or cross‐over design, so the unit of randomisation or allocation would have been the individual participant.

Dealing with missing data

If necessary we requested any further information from the study authors by written correspondence (e.g. emailing or writing (or both) to corresponding author(s)), however no additional relevant information was included in the review. We planned to perform a careful evaluation of important numerical data such as numbers of participants screened; numbers of randomised participants; and number of participants in the intention‐to‐treat (ITT), as‐treated, and per‐protocol (PP) populations; however, there were no randomised or quasi‐randomised studies. We investigated attrition rates, for example drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up, and withdrawals. We planned to appraise issues of missing data and imputation methods (e.g. last‐observation‐carried‐forward (LOCF)) critically (Higgins 2011); however, the level of reporting within studies was generally insufficient for us to assess this.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed the potential for publication bias by checking clinical trials registers for unpublished studies. If we had found more than 20 studies, we intended to use the funnel plot statistic and funnel plots to assess for the potential existence of small study bias (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

We planned to pool data using the random‐effects model as we expected heterogeneity of treatments and participants, but we also planned to use the fixed‐effect model to evaluate robustness of the model chosen and susceptibility to outliers.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to undertake subgroup analyses according to:

the condition causing the need for palliative care (i.e. malignant versus non‐malignant);

drug class; and

main symptom being treated.

There were insufficient studies to permit any of these subgroup analyses.

We planned to assess heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, and make a decision to either:

combine studies using a random‐effects model (where the I2 statistic was low to moderate, and the studies appeared to be reasonably similar); or

not combine all studies (where either the I2 statistic was moderate and reasons for heterogeneity were plausible and, therefore, indicated that combining studies was not appropriate, or the I2 statistic was high).

When combining studies, we intended to undertake post hoc subgroup analyses if sufficient studies existed in each subgroup of the plausible heterogeneity factor.

In investigating heterogeneity of the included studies, we planned to consider treatment factors such as the continuation or weaning of sedation, degree of sedation achieved, timing and dosage of medication, and study design factors such as the length of follow‐up, type of proxy used for quality of life measurement, and time of outcome measurement.

Sensitivity analysis

Since we planned to include included quasi‐randomised and non‐randomised comparative studies, we planned to investigate the effect of omitting such studies on the results using sensitivity analysis.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

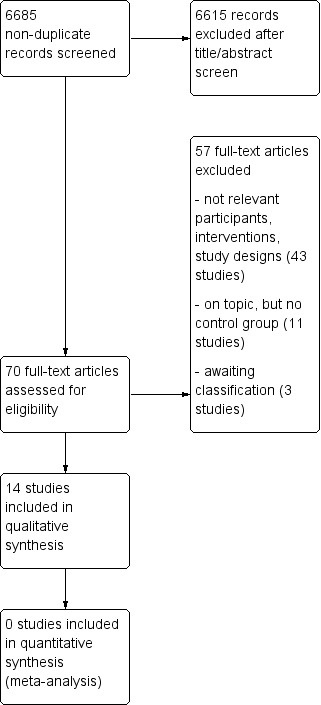

The searches resulted in 6685 citations to screen. After title and abstract screening, we reviewed 70 full‐text articles, resulting in 14 included studies and three awaiting classification (see Figure 1). We found no unpublished studies from clinical trials registers.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

See: Characteristics of included studies table.

We included 14 comparative studies (Alonso‐Babarro 2010; Bulli 2007; Caraceni 2012; Chiu 2001; Fainsinger 1998; Kohara 2005; Maltoni 2009; Maltoni 2012b; Muller‐Busch 2003; Radha Krishna 2012; Rietjens 2008; Stone 1997; Sykes 2003; Vitetta 2005). All studies compared a group of people who received palliative sedation with a concurrent control group who did not receive sedation. All were consecutive case series, however only four had prospective data collection (Bulli 2007; Chiu 2001; Maltoni 2009; Maltoni 2012b). One of these three used matching to select the controls (Maltoni 2009). The other 10 studies were retrospective chart reviews. None was randomised or quasi‐randomised.

The 14 studies included 4167 adults, of whom 1137 received palliative sedation. The proportion of people in each study receiving palliative sedation ranged from 12% to 67%. In all studies, the proportion of people with a cancer diagnosis was greater than 95%. The setting of the studies was hospices (seven studies), palliative care units (five studies), hospital oncology wards (three studies), and home‐based palliative care (two studies). Three studies involved more than one setting; Bulli 2007 was set in both the home and hospice, Chiu 2001 in hospice and palliative care units, and Stone 1997 in a hospital ward and a hospice.

The most commonly used drug to achieve palliative sedation was midazolam, which all 14 studies used. Other drugs were haloperidol (eight studies) and chlorpromazine (five studies). A small proportion of people received only opioids (morphine, fentanyl, and methadone), or propofol, other benzodiazepines (lorazepam, diazepam, clonazepam, flunitrazepam, and levomepromazine/methotrimeprazine), antihistamines (promethazine and chlorphenamine), phenobarbital, scopolamine hydrobromide, or ketamine hydrochloride.

The mean duration of sedation from initiation to death ranged from 19 hours (Rietjens 2008) to 3.4 days (Kohara 2005) in the nine studies that reported duration of sedation, although the Sykes 2003 study had a small group of people who received palliative sedation for seven days prior to death in addition to their larger group who received sedation in the last 48 hours of life.

The 14 comparative studies had control groups of concurrent participants in the same care setting who did not receive palliative sedation. Only the study by Maltoni matched control participants for age group, gender, reason for hospice admission, and Karnofsky performance status (Maltoni 2009). Four studies stated a funding source being their institution or a government granting body (Alonso‐Babarro 2010; Caraceni 2012; Chiu 2001; Maltoni 2009), and three studies stated that there were no competing interests to declare (Maltoni 2012b; Muller‐Busch 2003; Rietjens 2008).

The following table describes the included studies.

| Study | Setting | Study design | Number (%) in sedation group | Number in non‐sedated group | Two most common indications for sedation | Most common sedative(s) used | Type of sedation at commencement | Mean duration of sedation |

| Alonso‐Babarro 2010 | Home‐based care team | Retrospective cohort of consecutive cases | 29 (12%) | 236 | Delirium (62%), dyspnoea (14%) | Midazolam, levomepromazine | Dose titration to effective control of symptoms | 2.6 days (range 1‐10 days) |

| Bulli 2007 | 4 hospice and home‐based teams | Prospective cohort of consecutive cases | 136 (13%) | 939 | Not reported | Benzodiazepines, opioids, antipsychotics |

Continuous, deep | 68% ≤ 1 day, 25% 2‐4 days, 6% 5‐10 days |

| Caraceni 2012 | Palliative care team in tertiary care cancer hospital | Retrospective cohort of consecutive cases | 83 (64%) | 46 | Dyspnoea (37%), delirium (31%) | Benzodiazepine (48%), antipsychotic (45%), antipsychotic plus benzodiazepine (26%) | Not reported | Median 18 hours |

| Chiu 2001 | Hospice and Palliative care unit | Prospective cohort of consecutive cases | 70 (25%) | 206 | Delirium (57%), dyspnoea (23%) | Haloperidol (50%), midazolam (24%) | Intermittent (63%), continuous (37%) | Median 5 days |

| Fainsinger 1998 | Hospice | Retrospective cohort of consecutive cases | 23 (29%) | 53 | Delirium (87%), dyspnoea (4%) | Midazolam (91%), chlorpromazine and lorazepam (9%) | Continuous (61%), intermittent (30%) | 2.5 days (Median 1 day) |

| Kohara 2005 | Palliative care unit | Retrospective cohort of consecutive cases | 63 (51%) | 61 | Dyspnoea (63%), malaise/restlessness (40%) | Midazolam (98%), haloperidol (84%) | Continuous (69%), intermittent (30%) | 3.4 days |

| Maltoni 2009 | 4 hospices | Prospective matched cohort | 267 | 251 | Uncontrolled symptoms (53%), terminal phase of life (41%) | Lorazepam (38%), chlorpromazine (38%) | Continuous (44%), intermittent (56%), deep (38%), mild (62%) | 4 days (SD 6) (Median 2 days) |

| Maltoni 2012b | 2 palliative care units | Prospective cohort of consecutive cases | 72 (22%) | 255 | Delirium (61%), existential distress (38%) | Benzodiazepines (76%), antipsychotics (38%) | Continuous (92%), intermittent (6%) | 32.2 hours (range 25‐253) |

| Muller‐Busch 2003 | Palliative care unit | Retrospective cohort of consecutive cases | 80 (15%) | 468 | Pain (38%), dyspnoea (23%) | Midazolam | Titrated to symptom control, then intermittent if possible to control symptoms | Approx. 60 hours |

| Radha Krishna 2012 | Oncology ward in tertiary care hospital | Retrospective cohort of consecutive cases | 68 (29%) | 170 | Anxiety (24%), dyspnoea (21%) | Midazolam, haloperidol | Titrated to symptom control | Not reported |

| Rietjens 2008 | Acute palliative care unit | Retrospective cohort of consecutive cases | 68 (43%) | 89 | Terminal restlessness (62%), dyspnoea (47%) | Midazolam (75%), propofol (15%) | Not reported | Median 19 hours |

| Stone 1997 | Hospital support team and hospice | Retrospective cohort of consecutive cases | 30 (26%) | 85 | Delirium (60%), mental anguish (27%) | Midazolam (80%), haloperidol (37%) | Not reported | 1.3 days |

| Sykes 2003 | Hospice | Retrospective cohort of consecutive cases | 80 (34%) | 157 | Not reported | Midazolam, methotrimeprazine | Not reported | Not reported |

| Vitetta 2005 | Hospice | Retrospective cohort of consecutive cases | 68 (67%) | 34 | Not reported | Benzodiazepines, haloperidol | Titrated to symptom control, then intermittent | Not reported |

| SD: standard deviation. | ||||||||

Excluded studies

See: Characteristics of excluded studies table.

We found 11 studies that described the use of palliative sedation in case series of people, but they made no comparison with a control group.

Risk of bias in included studies

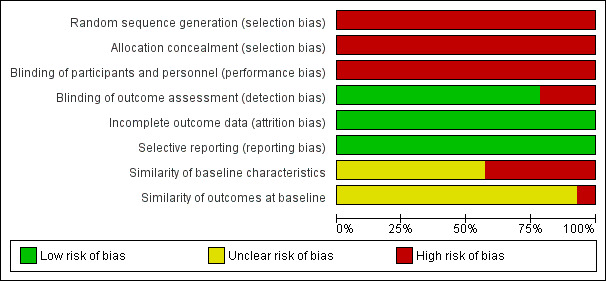

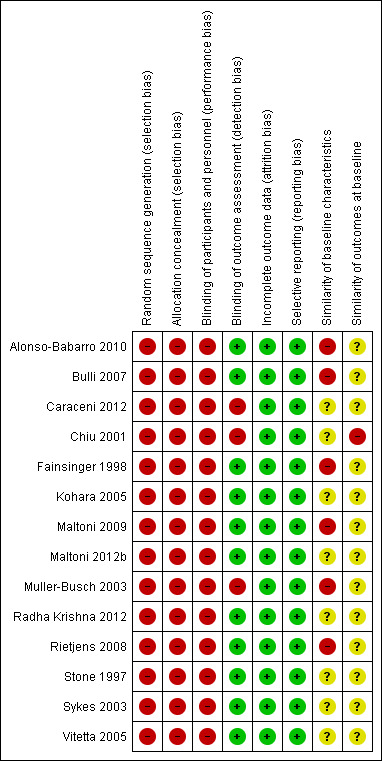

See Figure 2 and Figure 3 for 'Risk of bias' summary graphs.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

All 14 studies were at high risk of selection bias, as none was randomised or quasi‐randomised.

Blinding

No studies allocated people to treatment group; blinding of treatment was not possible; and blinded assessment of outcomes was not carried out; however, the main outcome assessed in the studies was survival, which is an objective measure. Therefore, they are all at high risk of performance bias, but low risk of detection bias. One study reported satisfaction with treatment, with people responding to the questionnaire being aware of treatment group, therefore, this study was at high risk of bias for satisfaction with treatment (Chiu 2001). Five studies assessed symptom control, and were at high risk of bias for the outcome symptom control .

Incomplete outcome data

All studies were consecutive case series. Studies did not generally report on the proportion of missing data for outcomes. One study reported that 9% of survival time data were missing (Chiu 2001).

Selective reporting

It is unlikely that any of the outcomes of this review were measured but not reported.

Other potential sources of bias

Since these were all non‐randomised studies, we assessed two further areas for risk of bias. Six studies reported on the difference between the sedated and non‐sedated groups on baseline characteristics (Alonso‐Babarro 2010; Bulli 2007; Fainsinger 1998; Maltoni 2009; Muller‐Busch 2003; Rietjens 2008). The five unmatched studies reported significant differences between the groups, so are at high risk of bias in comparing the outcomes between the groups. Whilst Maltoni 2009 matched participants on several factors, there was a significant difference between the groups in symptoms at admission, with the sedated group having more uncontrolled symptoms, as expected. Therefore, this study was also at high risk of bias. The other eight studies did not report a comparison of groups at baseline, so were at unclear risk of bias.

We also assessed whether the groups were alike at baseline on the outcomes to be measured in the study. Since survival is not an outcome that can be measured at baseline, all studies were at unclear risk of bias for survival. Only five studies measured an outcome other than survival.

Effects of interventions

Primary outcomes

No studies measured quality of life or well‐being.

Secondary outcomes

Five studies reported on symptom control (Caraceni 2012; Chiu 2001; Fainsinger 1998; Muller‐Busch 2003; Rietjens 2008). One study reported symptom control as odds ratios for prevalence of each symptom in the last seven days of life (Caraceni 2012); one as mean scores (Chiu 2001); one as adequacy of control rated good, fair, or poor (Fainsinger 1998); and two as symptom prevalence (Muller‐Busch 2003; Rietjens 2008). Therefore, we were unable to pool results for this outcome.

Caraceni 2012 reported only the odds ratio for comparison of sedated and non‐sedated groups for the prevalence of symptoms during the seven days before death, but did not report the counts or percentages that these were based on. CIs around the odds ratios were wide. There was no statistically significant difference between the sedated and non‐sedated groups in the prevalence of confusion, gastrointestinal symptoms, pain, or psychological distress. The odds ratio for recurrent agitation was 3.5 (95% CI 1.4 to 8.8), for recurrent drowsiness was 0.3 (95% CI 0.2 to 0.7), and for recurrent dyspnoea was 4.2 (95% CI 1.9 to 9.2), indicating that the sedated group was more likely to experience recurrent agitation and dyspnoea, but less likely to experience recurrent drowsiness than the non‐sedated group.

Chiu 2001 measured pain, dyspnoea, and delirium in 70 people in the sedated group and 206 people in the non‐sedated group, and found that pain scores and dyspnoea scores measured two days before death were similar between groups. The mean score for pain (10‐point scale) was 2.5 in the sedated group and 2.1 in the non‐sedated group (P value = 0.27, t‐test). The mean score for dyspnoea (10‐point scale) was 3.0 in the sedated group and 2.9 in the non‐sedated group (P value = 0.78, t‐test). However, mean delirium score two days before death was significantly worse in the sedated group (1.8 in the sedated group compared with 1.1 in the non‐sedated group, 0 to 3 scale, P value < 0.001, t‐test).

Fainsinger 1998 measured adequacy of overall symptom control as good, fair, or poor, daily for the day of death and six days prior in 23 people in the sedated group and 53 people in the non‐sedated group. Symptom control was significantly worse in the sedated group on the day of death and the two days prior (P value < 0.001). The percentage of people in the sedated group with good control was 61% on the day of death, 35% on the day prior, and 38% two days prior, compared with 96% on the day of death, 88% on the day prior, and 87% two days prior in the non‐sedated group.

Muller‐Busch 2003 measured prevalence of pain, dyspnoea, delirium, and anxiety over the course of admission, and during the last 48 hours of life. They did not report between‐group results, but rather the change over time in each group for each symptom. Pain improved significantly in both groups between admission and the last 48 hours of life; however, all other symptoms worsened significantly.

Rietjens 2008 measured symptom prevalence at 0 to 24 hours prior to death, and 25 to 48 hours prior to death. Only participants commencing sedation during this period were reported for the sedated group (45 for the 0 to 24 hours period, and 13 for the 25 to 48 hours period). That is, it was a measure of symptom control shortly after commencing sedation. Pain, constipation, nausea/vomiting, and anxiety were not significantly different between the sedated and non‐sedated groups. However, in both periods, the percentage of people with dyspnoea was significantly higher in the sedated group at 50% of people compared with 31% in the non‐sedated group at 0 to 24 hours prior to death, and 69% in the sedated group compared with 38% in the non‐sedated group 25 to 48 hours prior death. The percentage of people with delirium at 0 to 24 hours prior to death was also significantly worse in the sedated group (29% in the sedated group compared with 13% in the non‐sedated group), but not at 25 to 48 hours (31% in the sedated group compared with 23% in the non‐sedated group).

No studies measured duration of symptom control or time to control of symptoms in using comparative methods.

Only one study reported on unintended adverse effects of sedation (Chiu 2001). It stated that there were no significant adverse events in the sedated group; however, four of 70 (6%) participants appeared to have drug‐induced delirium. It was also reported that no respiratory suppression was noted.

The least biased time comparison possible between intervention and control groups was from admission/referral to death in this set of observational studies. Whilst all studies except one measured time from admission or referral to death, some used mean time, and some used median time. Measures of variance were frequently missing or indicated skewed data distributions; therefore, we were unable to pool results. We have reported these results in tabular form below.

Table: survival time comparison between sedated and non‐sedated groups, from time of admission or referral

| Study | Measurement unit | Survival time in the sedated group | Survival time in the non‐sedated group | Comparison |

| Alonso‐Babarro 2010 | Mean | 64 days (SD 60) | 63 days (SD 88) | P value = 0.963, t‐test |

| Bulli 2007 (cohort 1) | Median | 23 days | 23 days | NS, test not reported |

| Bulli 2007 (cohort 2) | Median | 24 days | 17 days | ‐ |

| Chiu 2001 | Mean | 28.5 days | 24.7 days | P value = 0.43, t‐test |

| Fainsinger 1998 | Mean | 9 days (SD 5) | 6 days (SD 7) | P value = 0.09, t‐test |

| Kohara 2005 | Mean | 28.9 days (SD 25.8) | 39.5 days (SD 43.7) | P value = 0.10, t‐test |

| Maltoni 2009 | Median | 12 days | 9 days | P value = 0.95, log‐rank test HR 0.92 (90% CI 0.80 to 1.06) |

| Maltoni 2012b | Mean | 11 days (95% CI 9 to 11) | 9 days (95% CI 7 to 11) | P value = 0.51, log‐rank test |

| Muller‐Busch 2003 | Mean | 21.5 days (SD 20.3) | 21.1 days (SD 23.6) | NS, t‐test |

| Radha Krishna 2012 | Median | 8 days (approx.)* | 8 days (approx.)* | P value = 0.78, log‐rank test |

| Rietjens 2008 | Median | 8 days | 7 days | P value = 0.12, test not reported |

| Stone 1997 | Mean | 18.6 days | 19.1 days | P value > 0.2, test not reported |

| Sykes 2003 | Mean | 14.3 days (95% CI 11.2 to 17.4)1 36.6 days (95% CI 31.5 to 41.7)2 |

14.2 days (95% CI 12.7 to 15.7) | P value = 0.23, t‐test P value < 0.001, t‐test |

| Vitetta 2005 | Mean | 36.5 days (SD 66) | 17.0 days (SD 43) | P value = 0.12, t‐test |

| CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; NS: not statistically significantly different; SD: standard deviation. * Times not reported; have been interpolated from survival curves. 1 people receiving palliative sedation for last 48 hours of life. 2 people receiving palliative sedation for last 7 days of life. 1 study gave results for the outcome of satisfaction with treatment, as reported by the medical staff, family, and participant (Chiu 2001). For the medical staff, satisfaction was rated as 71% yes, 20% fair, 9% no, 0% unavailable. For the family, satisfaction was rated as 67% yes, 20% fair, 4% no, 9% unavailable. For the participant, satisfaction was rated as 53% yes, 10% fair, 4% no, 33% unavailable. | ||||

Discussion

Summary of main results

No studies reported on the primary outcome of this review (i.e. quality of life or well‐being).

Four studies compared the sedated and non‐sedated groups for control of symptoms, and showed that despite sedation with the intent to control symptoms, delirium and dyspnoea were still troublesome symptoms in these people in the last few days of life, and were significantly worse in the sedated group. Control of other symptoms appeared to be similar in sedated and non‐sedated groups.

All studies except one compared survival time in the sedated and non‐sedated groups, and concluded that there was no statistically significant difference between the groups. This is important, as there has been extensive discussion in the literature about whether palliative sedation might shorten life, therefore leading to uncertainty by some physicians about whether to use this treatment for fear of the perception that they were performing a form of euthanasia (Billings 1996; De Graeff 2007; Rietjens 2006). The use of time from admission to death in comparative groups may be a weak measure of any potential effect of palliative sedation on shortening life. However, it is difficult to determine what the comparison would be in the group who did not receive sedation, and time from admission to death may be the only feasible comparative measure. Although we were unable to meta‐analyse this outcome, and CIs around the point estimates in individual studies were wide, there was consistency in this result over all studies, with 12 of the 13 studies having a longer survival time in the sedated group.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

No studies measured the primary outcome of this review, quality of life or well‐being, in a formal way. Many of the study reports discussed the 'settling' of symptoms in an anecdotal way; however, there were no quantitative reports.

Quality of the evidence

There were no randomised or quasi‐randomised trials, and it is unlikely that these will be done. Therefore, the best quality evidence will come from well‐designed observational studies. Only one study in this review attempted to reduce selection bias between the groups by matching groups on baseline characteristics (Maltoni 2009). However, it is likely that even if this is done, the groups will differ significantly in their level of symptom control, with people with more severe symptoms more likely to receive palliative sedation. Hence, even matching of controls cannot adjust for this confounder. It would be possible to adjust for this confounder (and others) statistically, but this was not done in any of the reported studies.

Potential biases in the review process

The search strategy for this review was wide; however, this was a difficult topic to search. It was possible that the search missed some studies, despite screening more than 5000 citations and screening the bibliographies of narrative reviews.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This is the first review, to our knowledge, that attempts to summarise only studies that have compared outcomes for sedated and non‐sedated people.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Although there is no evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and limited evidence from observational studies about the efficacy of palliative sedation in terms of a person's quality of life or symptom control, compared with non‐sedated people, there was evidence that palliative sedation does not hasten death, which has been a concern of physicians and families in prescribing this treatment. However, this evidence comes from low quality studies, so should be interpreted with caution.

Implications for research.

Measurement

Studies that specifically measure the efficacy of sedation in terms of a person's well‐being and control of symptoms, compared with non‐sedated people, are required. This therapy is widely used, in both continuous deep sedation and intermittent forms, but evidence is lacking on the success of controlling symptoms adequately. Adverse events reporting also needs to be improved in order to quantify the potential harms of treatment. Description of the depth of sedation, timing, and length of sedation was poorly reported in many studies, and the method of measuring and describing this was inconsistent between studies.

Design

Future studies should attempt to utilise control groups that are close in prognostic factors to the intervention group, in order to make the groups as alike as possible, except for the presence of sedation. Alternatively, statistical methods to adjust for differences between intervention and control groups could be used.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 22 November 2018 | Review declared as stable | Stable to 2024. See Published notes. |

| 22 November 2018 | Amended | Contact Person updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 11, 2012 Review first published: Issue 1, 2015

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 17 January 2017 | Review declared as stable | See Published notes. |

Notes

2017

A restricted search in January 2017 did not identify any potentially relevant studies likely to change the conclusions, although we are aware of one large study due to be published in 2017. Therefore, following discussion with the authors and editors, this review has now been stabilised for 12 months, at which point we will assess the review for updating.

2018

A restricted search in November 2018 did not identify any potentially relevant studies likely to change the conclusions. Following discussion with the authors and editors, this review has now been stabilised for five years, at which point we will assess the review for updating. If appropriate, we will update the review sooner if new evidence likely to change the conclusions is published, or if standards change substantially which necessitate major revisions.

The Contact Person has been updated from Elaine Beller to Geoffrey Mitchell.

Acknowledgements

The review authors would like to thank Jane Hayes and Joanne Abbott, Trials Search Co‐ordinators (TSCs) of the Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Review Group (PaPaS), for assistance with the search strategy, and Sarah Thorning, TSC of the Acute Respiratory Infections Group for assistance with management of references and databases.

Cochrane Review Group funding acknowledgement: the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the largest single funder of the Cochrane PaPaS Group.

Disclaimer: the views and opinions expressed therein are those of the review authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, National Health Service (NHS), or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

CENTRAL

#1MeSH descriptor: [Central Nervous System Depressants] explode all trees #2MeSH descriptor: [Anesthesia] explode all trees #3MeSH descriptor: [Benzodiazepines] explode all trees #4MeSH descriptor: [Barbiturates] explode all trees #5MeSH descriptor: [Histamine Antagonists] explode all trees #6MeSH descriptor: [Psychotropic Drugs] explode all trees #7(benzodiazepine* or barbiturate* or anaesthesia or anesthesia or opioid* or antipsychotic* or anti‐psychotic* or antihistamine* or anti‐histamine* or hypnotic* or sedat* or tranquil*):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #8(symptom* near/6 (relie* or control*)):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #9#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 #10MeSH descriptor: [Palliative Care] this term only #11MeSH descriptor: [Terminal Care] explode all trees #12MeSH descriptor: [Terminally Ill] this term only #13palliat*:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #14(terminal* near/6 (care or caring or ill*)):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #15(terminal‐stage* or terminal stage* or dying or (close near/6 death)):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #16(end near/3 life):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #17hospice*:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #18((end‐stage* or end stage*) near/6 (disease* or ill* or care or caring)):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #19((incurable or advanced) near/6 (ill* or disease*)):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #20#10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 #21#20 and #9

MEDLINE (Ovid)

1 exp Central Nervous System Depressants/

2 exp Anesthesia/

3 exp Benzodiazepines/

4 exp Barbiturates/

5 exp Histamine Antagonists/

6 exp Psychotropic Drugs/

7 (benzodiazepine* or barbiturate* or anaesthesia or anesthesia or opioid* or antipsychotic* or anti‐psychotic* or antihistamine* or anti‐histamine* or hypnotic* or sedat* or tranquil*).mp.

8 (symptom* adj6 (relie* or control*)).mp.

9 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8

10 Palliative Care/

11 exp Terminal Care/

12 Terminally Ill/

13 palliat*.mp.

14 (terminal* adj6 (care or caring or ill*)).mp.

15 (terminal‐stage* or terminal stage* or dying or (close adj6 death)).mp.

16 (end adj3 life).mp.

17 hospice*.mp.

18 ((end‐stage* or end stage*) adj6 (disease* or ill* or care or caring)).mp.

19 ((incurable or advanced) adj6 (ill* or disease*)).mp.

20 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19

21 9 and 20

22 randomized controlled trial.pt.

23 controlled clinical trial.pt.

24 randomized.ab.

25 placebo.ab.

26 clinical trials as topic.sh.

27 randomly.ab.

28 trial.ti.

29 exp Cohort Studies/

30 (cohort* or observational* or comparative* or quantitative* or (before and after) or (interrupted and time)).mp.

31 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30

32 21 and 31

EMBASE (Ovid)

1 exp Central Nervous System Depressants/

2 exp Anesthesia/

3 exp Benzodiazepines/

4 exp Barbiturates/

5 exp Histamine Antagonists/

6 exp Psychotropic Drugs/

7 (benzodiazepine* or barbiturate* or anaesthesia or anesthesia or opioid* or antipsychotic* or anti‐psychotic* or antihistamine* or anti‐histamine* or hypnotic* or sedat* or tranquil*).tw.

8 (symptom* adj6 (relie* or control*)).tw.

9 or/1‐8

10 Palliative Care/

11 exp Terminal Care/

12 Terminally Ill/

13 palliat*.tw.

14 (terminal* adj6 (care or caring or ill*)).tw.

15 (terminal‐stage* or terminal stage* or dying or (close adj6 death)).tw.

16 (end adj3 life).tw.

17 hospice*.tw.

18 ((end‐stage* or end stage*) adj6 (disease* or ill* or care or caring)).tw.

19 ((incurable or advanced) adj6 (ill* or disease*)).tw.

20 or/10‐19

21 9 and 20

22 "randomized controlled trial".tw.

23 "controlled clinical trial".tw.

24 randomized.ab.

25 placebo.ab.

26 "clinical trial (topic)"/

27 randomly.ab.

28 trial.ti.

29 exp Cohort Studies/

30 (cohort* or observational* or comparative* or quantitative* or (before and after) or (interrupted and time)).mp.

31 or/22‐30

32 21 and 31

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Alonso‐Babarro 2010.

| Methods | Design: retrospective medical record review of a consecutive case series for calendar years 2002‐2004, comparing people who received palliative sedation with people who did not Setting: home‐based care by palliative care team in Madrid, Spain |

|

| Participants | 245 people with cancer who died at home. 29 (12%) received palliative sedation. Indications for sedation were delirium (62%), dyspnoea (14%), nausea/vomiting/bowel obstruction (7%), seizures (7%), anxiety/psychoexistential suffering (7%), and pain (3%) | |

| Interventions | Palliative sedation treatment was according to a written protocol, using midazolam, then levomepromazine if midazolam not effective, then phenobarbital if levomepromazine not effective. Mean duration of sedation was 2.6 days (range 1‐10). Mean dose in the last 24 hours of life was midazolam 73.88 mg and levomepromazine 125 mg. Only 2 people received levomepromazine, and 0 required phenobarbital | |

| Outcomes | Survival after start of palliative care team care. Mean of 63.9 days (SD 60.0) in sedation group and 63.3 days (SD 88.1) in non‐sedation group | |

| Notes | Funding source: NIH grants (Alonso‐Babarro, Torres‐Vigil) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation or other allocation to treatment group |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding of treatment group possible |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Not done. Retrospective chart review. However, survival was an objective outcome |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All included participants' data reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of outcomes being measured but not reported |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics | High risk | Baseline differences in age (sedated group was younger), and awareness of prognosis (sedated group was more aware) |

| Similarity of outcomes at baseline | Unclear risk | Baseline comparison of the only outcome of this review that was reported was not possible (survival) |

Bulli 2007.

| Methods | Design: prospective consecutive case series in 2000 and 2003‐2004, comparing people who received palliative sedation with people who did not Setting: 4 home and hospice‐based palliative care teams in Florence, Italy |

|

| Participants | 1075 people; 1045 had cancer. 136 (13%) received palliative sedation. Indications for sedation were not reported. Baseline quality of life (Edmonton Symptom Assessment System questionnaire) was not statistically significantly different between the sedated and non‐sedated groups, although slightly lower in the sedated group | |

| Interventions | Treatment was at the team's discretion. 12% received opioids only (morphine, fentanyl, methadone), 16% combined opioids plus antipsychotics (haloperidol, chlorpromazine), 18% opioids plus benzodiazepines (midazolam, diazepam), and 54% opioids plus antipsychotics plus benzodiazepines. 68% received sedation for ≤ 1 day, 25% for 2‐4 days, and 6% for 5‐10 days | |

| Outcomes | Survival from time of start of palliative care team intervention. Median survival times in the sedated groups were 23 days (2000 cohort) and 24 days (2003‐2004 cohort). Median survival times in the non‐sedated groups were 23 days (2000 cohort) and 17 days (2003‐2004 cohort). Reported no other outcomes of this review | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation or other allocation to treatment group |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding of treatment group possible |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Treating team (aware of treatment) assessed outcomes; however, survival is an objective outcome |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants reported (consecutive case series) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of outcomes being measured but not reported |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics | High risk | Baseline quality of life similar. Sedated participants were statistically significantly younger, and had worse performance status (Karnofsky index) |

| Similarity of outcomes at baseline | Unclear risk | Baseline comparison of the only outcome of this review that was reported was not possible (survival) |

Caraceni 2012.

| Methods | Design: retrospective chart review of consecutive case series over a 5‐year period in Milan, Italy, comparing people who received palliative sedation with people who did not Setting: palliative care team in a tertiary care cancer hospital |

|

| Participants | 129 people with cancer. 83 (64%) received palliative sedation. Indications for sedation were predominantly dyspnoea (37%) and delirium (31%) | |

| Interventions | Protocol for palliative sedation not reported. 40 (45%) people received an antipsychotic, 43 (48%) benzodiazepine, and 23 (26%) antipsychotic plus benzodiazepine. 7 (10%) people received opioid‐only, and a minority of people received antihistamine and combinations of antipsychotics and benzodiazepines | |

| Outcomes | Prevalence of symptoms in the 7 days prior to death | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation or other allocation to treatment group |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding of treatment group possible |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Outcomes data collected from medical records |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants reported (consecutive case series) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of outcomes being measured but not reported |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics | Unclear risk | Baseline comparison not reported |

| Similarity of outcomes at baseline | Unclear risk | Baseline comparison not reported |

Chiu 2001.

| Methods | Design: prospective consecutive case series in 1998‐1999 comparing people who received palliative sedation with people who did not Setting: hospice and palliative care unit in Taiwan |

|

| Participants | 276 people with cancer. 70 (25%) received palliative sedation. Indications for sedation were delirium (57%), dyspnoea (23%), pain (10%), insomnia (7%), and severe itching (3%) | |

| Interventions | Protocol for palliative sedation not reported. 50% of people received haloperidol, 24% midazolam, 13% rapidly increasing morphine dose, 10% other benzodiazepines, and 3% chlorpromazine. The mean survival time was 12.6 ± 19.6 days from starting sedation to the time of death (median of 5 days). | |

| Outcomes | Survival from time of start of palliative care team intervention. Mean survival time was 28.5 days in sedated group and 24.7 days in non‐sedated group. Satisfaction with treatment for participant and family was reported in the sedated group only. 53% of people were satisfied, 10% rated satisfaction as fair, 4% poor, and 33% were unable to rate satisfaction (due to reduced level of consciousness). 67% of family rated satisfaction high, 20% fair, 4% poor, and 9% with data unavailable. Symptom scores for pain, dyspnoea, and delirium were compared at 2 days before death. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in mean score for pain and dyspnoea, but the sedated group had significantly higher mean score for delirium (1.80 in sedated group vs. 1.14 in non‐sedated group, 0‐3 scale, P value < 0.001). Unintended effects of sedation were reported as minor, with 4 people experiencing drug‐induced delirium | |

| Notes | Funding source: National Taiwan University Hospital | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation or other allocation to treatment group |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding of treatment group possible |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Treating team (aware of treatment) collected outcomes. Therefore, for the outcomes of symptom control and satisfaction with treatment, we rated this study at high risk of bias |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 24 (9%) people had missing data for survival time. Not differential between sedated and non‐sedated groups |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of outcomes being measured but not reported |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics | Unclear risk | Baseline comparison of most characteristics of palliative sedation and non‐sedated groups not reported |

| Similarity of outcomes at baseline | High risk | Non‐sedated group had significantly lower dyspnoea and delirium symptom scores. Baseline comparison of other outcomes not reported |

Fainsinger 1998.

| Methods | Design: retrospective chart review of consecutive case series, comparing people who received palliative sedation with people who did not Setting: hospice in Cape Town, South Africa |

|

| Participants | 79 people who died in the hospice; all but 3 had cancer; 76 had sufficient data for inclusion in analyses; 23 (29%) received palliative sedation; most (96%) had cancer. Indications for sedation were delirium (87%), dyspnoea (4%), and both delirium and dyspnoea (4%) | |

| Interventions | Protocol for palliative sedation not reported. 61% received continuous subcutaneous midazolam, 30% intermittent doses of benzodiazepines, and 9% chlorpromazine plus lorazepam. "Patients were sedated on average 2.5 days before death (median 1 day; range 4 hours–12 days)." | |

| Outcomes | Survival from time of admission to the hospice. Mean time 9 days (SD 5) in sedated group and 6 days (SD 7) in non‐sedated group. Adequacy of symptom control was measured daily, and reported for the last 6 days of life, demonstrating significantly poorer control of symptoms in the sedated group in the last 3 days of life. No other outcomes of this review were reported | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation or other allocation to treatment group |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding of treatment group possible |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Outcomes data collected from medical records. Survival is an objective outcome |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants reported (consecutive case series) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of outcomes being measured but not reported |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics | High risk | Non‐sedated group were significantly older, and had higher levels of dyspnoea and delirium |

| Similarity of outcomes at baseline | Unclear risk | Baseline comparison of outcome (survival) not possible |

Kohara 2005.

| Methods | Design: retrospective chart review of consecutive case series in calendar year 1999, comparing people who received palliative sedation with people who did not Setting: palliative care unit in Japan |

|

| Participants | 124 consecutive participants; 63 (51%) received palliative sedation; all had cancer. Indications for sedation were dyspnoea (63%), general malaise/restlessness (40%), pain (25%), agitation (21%), and nausea and vomiting (6%). 34 (54%) people had > 1 uncontrollable symptom | |

| Interventions | Protocol for palliative sedation not reported. In the sedated group, 98% of people received midazolam, 84% haloperidol, 10% scopolamine hydrobromide, 5% chlorpromazine, 2% flunitrazepam, and 2% ketamine hydrochloride. Mean time from start of sedation to death was 3.4 days | |

| Outcomes | Survival time from admission to the hospice. Mean time was 28.9 days (SD 25.8) in sedated group and 39.5 days (SD 43.7) in non‐sedated group. Mean time sedated was 3.4 days. Symptom prevalence for pain, constipation, dyspnoea, nausea/vomiting, delirium, and anxiety were reported for the periods 0‐24 hours before death and 25‐48 hours before death comparing sedated vs. non‐sedated groups. Only data from people beginning sedation during these periods were reported in the sedated group, demonstrating a significantly higher proportion of people in the sedated group having delirium (29% in sedated group vs. 13% in non‐sedated group). No other outcomes of this review were reported | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation or other allocation to treatment group |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding of treatment group possible |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Outcomes data collected from medical records. However, survival is an objective outcome |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants reported (consecutive case series) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of outcomes being measured but not reported |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics | Unclear risk | No baseline comparison of sedated and non‐sedated groups reported |

| Similarity of outcomes at baseline | Unclear risk | No baseline comparison of sedated and non‐sedated groups reported |

Maltoni 2009.

| Methods | Design: prospective, non‐randomised cohort study, with matching of sedated and non‐sedated participants on gender, age group, reason for admission, and Karnofsky performance status. On admission, if sedation was chosen for a participant, they were matched with a recent non‐sedated inpatient Setting: 4 hospices in Emilia‐Romagna, Italy from March 2005 to December 2006 |

|

| Participants | 518 people with cancer. 267 consecutive participants in the sedated group and 251 matched recent inpatients in the non‐sedated group. Reasons for admission were uncontrolled symptoms (53%), terminal phase of life (41%), and psychosocial distress (6%). Indications for palliative sedation were delirium or agitation (or both) (79%), dyspnoea (20%), pain (11%), vomiting (5%), psychological and physical distress (19%), only psychological distress (6%), and other reason (4%) | |

| Interventions | Criteria for initiating palliative sedation were standardised; however, protocol for administering sedation not reported. Sedation was achieved with antipsychotics in 84%, benzodiazepines in 54% and opioids in 26%. Mean duration of sedation was 4 days (SD 6) | |

| Outcomes | Survival time from admission to the hospice. Median time was 12 days in sedated group and 9 days in non‐sedated group. No other outcomes of this review were reported | |

| Notes | Funding: Istituto Oncological Romagnolo, Forli and Istituto Scientifico Romagnolo per lo Studio e la Cura dei Tumori | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation or other allocation to treatment group |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding of treatment group possible |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Outcomes data collected from medical records. However, survival is an objective outcome |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants reported (consecutive case series) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of outcomes being measured but not reported |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics | High risk | Matching was used to ensure baseline comparability on demographic variables. There were more people with uncontrollable symptoms in the sedated group (57%) compared with the non‐sedated group (49%) |

| Similarity of outcomes at baseline | Unclear risk | Baseline comparison of outcomes not possible (survival) |

Maltoni 2012b.

| Methods | Design: prospective, non‐randomised cohort study from October 2009 to June 2010 comparing people who received palliative sedation with people who did not Setting: 2 palliative care units in Italy |

|

| Participants | 327 consecutive participants; 72 (22%) received palliative sedation. Indications for palliative sedation were delirium (61%), existential distress (38%), dyspnoea (29%), pain (21%), and other reason (8%) | |

| Interventions | 96% achieved sedation with midazolam, 4% with another benzodiazepine. Mean duration of sedation was 32.2 hours (range 25‐253) | |

| Outcomes | Survival time from admission to the unit. Mean time was 11 days in sedated group and 9 days in non‐sedated group. Change in overall symptoms was reported only for the sedated group | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation or other allocation to treatment group |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding of treatment group possible |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Outcomes data collected from prospective database records. However, survival is an objective outcome |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants reported (consecutive case series) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of outcomes being measured but not reported |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics | Unclear risk | No baseline comparison of groups given |

| Similarity of outcomes at baseline | Unclear risk | Baseline comparison of outcome not possible (survival) |

Muller‐Busch 2003.

| Methods | Design: retrospective chart review of consecutive case series in 1995‐2002 comparing people who received palliative sedation with people who did not Setting: palliative care unit in Germany |

|

| Participants | 548 people who died in the palliative care unit; 10.5% had a non‐cancer diagnosis; 80 (15%) received palliative sedation | |

| Interventions | Protocol for palliative sedation not reported, although the unit had general guidelines for the initiation and maintenance of sedation. Sedation was achieved with midazolam in most cases | |

| Outcomes | Survival time from admission to the palliative care unit: Median 14.0 days and mean 21.1 (SD 23.6) days in the non‐sedated group, and median 15.5 days and mean 21.5 (SD 21.1) days in the sedated group. Symptom prevalence was reported at admission, during the course of admission, and in the last 48 hours before death. No other outcomes of this review were reported | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation or other allocation to treatment group |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding of treatment group possible |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Outcomes data collected from medical records. Survival is an objective outcome; however, we judged symptom control outcome at high risk of bias |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants reported (consecutive case series) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of outcomes being measured but not reported |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics | High risk | Sedated group significantly younger, and some differences in disease stage and cancer site |

| Similarity of outcomes at baseline | Unclear risk | Baseline comparison of outcome (survival) not possible. Baseline differences in proportions with pain, dyspnoea, anxiety (higher in sedated group), and delirium (lower in sedated group) |

Radha Krishna 2012.

| Methods | Design: retrospective chart review of consecutive case series from September 2006 to September 2007, comparing people who received palliative sedation with people who did not Setting: oncology ward in a tertiary care hospital in Singapore |

|

| Participants | 238 people with cancer; 68 (29%) received palliative sedation. Indications for sedation were anxiety (24%); dyspnoea (21%); agitation (19%); nausea (18%); dyspnoea and anxiety (9%); agitation and nausea (3%); confusion (3%); stiffness (3%); dyspnoea, anxiety, and stiffness (1%) | |

| Interventions | Protocol for palliative sedation not reported. Sedation was achieved with either midazolam (57% of participants) or haloperidol (43%). Duration of sedative use not reported | |

| Outcomes | Survival time from admission to the ward was reported in graphical form, and was not statistically significantly different between the sedated and non‐sedated groups (P value = 0.78, log‐rank test). No median survival times were reported, but they were approximately 8 days in both groups (interpolated from survival curves) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation or other allocation to treatment group |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding of treatment group possible |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Outcomes data collected from medical records. However, survival is an objective outcome |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants reported (consecutive case series) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of outcomes being measured but not reported |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics | Unclear risk | No baseline comparison of groups given |

| Similarity of outcomes at baseline | Unclear risk | Baseline comparison of outcome not possible (survival) |

Rietjens 2008.

| Methods | Design: retrospective chart review of consecutive case series comparing people who received palliative sedation with people who did not Setting: acute palliative care unit in an academic cancer hospital in The Netherlands |

|

| Participants | 753 people with cancer; 157 people died and were included in the analysis. 68 (43%) received palliative sedation. Indications for sedation were terminal restlessness (62%), dyspnoea (47%), pain (26%), and anxiety (6%) | |

| Interventions | Protocol for palliative sedation not reported. 75% received midazolam, 1% midazolam plus another benzodiazepine, 9% midazolam plus propofol, and 15% propofol only. Median duration of sedation was 19 hours (range 1‐125) | |

| Outcomes | Survival time from admission to the palliative care unit. Median time was 8 days in sedated group and 7 days in non‐sedated group. Symptom control was recorded at 0‐24 hours before death and 25‐48 hours before death comparing the non‐sedated group with people who began sedation at these time points. No other outcomes of this review were reported | |

| Notes | Declarations of interest: the authors stated that they "confirm that there are no financial or personal relationships with other people or organisations that could have inappropriately influenced the work" | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation or other allocation to treatment group |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding of treatment group possible |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Outcomes data collected from medical records. However, survival is an objective outcome |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants reported (consecutive case series) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of outcomes being measured but not reported |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics | High risk | Baseline comparison of demographic variables and symptoms was reported. Sedated participants were significantly younger, more had gastrointestinal tumours, and a shorter time to admission since diagnosis of metastatic tumours |

| Similarity of outcomes at baseline | Unclear risk | At baseline, symptom prevalence was similar in the 2 groups. Baseline comparison of other outcomes not possible (survival) |

Stone 1997.

| Methods | Design: retrospective chart review of consecutive case series, comparing people who received palliative sedation with people who did not Setting: hospital support team and hospice in London, UK (January to December 1994 for the support team, February 1995 for the hospice) |

|

| Participants | 115 people; 30 (26%) received palliative sedation for uncontrollable symptoms. Indications for sedation were agitated delirium (18), mental anguish (8), pain (6), dyspnoea (6), and other (1). No description of clinical diagnoses reported. Another group of participants received some sedative medications, but it appeared the indication was not for otherwise intractable symptoms | |

| Interventions | Protocol for palliative sedation not reported. 80% received midazolam, 37% haloperidol, 33% methotrimeprazine, and 3% phenobarbitone. Mean duration of sedation was 1.3 days. Mean doses of drugs on the day of death were midazolam 22 mg/24 hour, methotrimeprazine 64 mg/24 hour, and haloperidol 5 mg/24 hour | |

| Outcomes | Survival time from admission to the support team or hospice. Mean time was 18.6 days in sedated group and 19.1 days in non‐sedated group. No other outcomes of this review were reported | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No randomisation or other allocation to treatment group |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding of treatment group possible |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Outcomes data collected from medical records. However, survival is an objective outcome |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants reported (consecutive case series) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of outcomes being measured but not reported |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics | Unclear risk | Baseline comparison of groups only given for age and gender (not significantly different) |

| Similarity of outcomes at baseline | Unclear risk | Baseline comparison of other outcomes not possible (survival) |

Sykes 2003.