Abstract

Background

This is an update of a review last published in Issue 9, 2009, of The Cochrane Library. Pulse oximetry is used extensively in the perioperative period and might improve patient outcomes by enabling early diagnosis and, consequently, correction of perioperative events that might cause postoperative complications or even death. Only a few randomized clinical trials of pulse oximetry during anaesthesia and in the recovery room have been performed that describe perioperative hypoxaemic events, postoperative cardiopulmonary complications and cognitive dysfunction.

Objectives

To study the use of perioperative monitoring with pulse oximetry to clearly identify adverse outcomes that might be prevented or improved by its use.

The following hypotheses were tested.

1. Use of pulse oximetry is associated with improvement in the detection and treatment of hypoxaemia.

2. Early detection and treatment of hypoxaemia reduce morbidity and mortality in the perioperative period.

3. Use of pulse oximetry per se reduces morbidity and mortality in the perioperative period.

4. Use of pulse oximetry reduces unplanned respiratory admissions to the intensive care unit (ICU), decreases the length of ICU readmission or both.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2013, Issue 5), MEDLINE (1966 to June 2013), EMBASE (1980 to June 2013), CINAHL (1982 to June 2013), ISI Web of Science (1956 to June 2013), LILACS (1982 to June 2013) and databases of ongoing trials; we also checked the reference lists of trials and review articles. The original search was performed in January 2005, and a previous update was performed in May 2009.

Selection criteria

We included all controlled trials that randomly assigned participants to pulse oximetry or no pulse oximetry during the perioperative period.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed data in relation to events detectable by pulse oximetry, any serious complications that occurred during anaesthesia or in the postoperative period and intraoperative or postoperative mortality.

Main results

The last update of the review identified five eligible studies. The updated search found one study that is awaiting assessment but no additional eligible studies. We considered studies with data from a total of 22,992 participants that were eligible for analysis. These studies gave insufficient detail on the methods used for randomization and allocation concealment. It was impossible for study personnel to be blinded to participant allocation in the study, as they needed to be able to respond to oximetry readings. Appropriate steps were taken to minimize detection bias for hypoxaemia and complication outcomes. Results indicated that hypoxaemia was reduced in the pulse oximetry group, both in the operating theatre and in the recovery room. During observation in the recovery room, the incidence of hypoxaemia in the pulse oximetry group was 1.5 to three times less. Postoperative cognitive function was independent of perioperative monitoring with pulse oximetry. A single study in general surgery showed that postoperative complications occurred in 10% of participants in the oximetry group and in 9.4% of those in the control group. No statistically significant differences in cardiovascular, respiratory, neurological or infectious complications were detected in the two groups. The duration of hospital stay was a median of five days in both groups, and equal numbers of in‐hospital deaths were reported in the two groups. Continuous pulse oximetry has the potential to increase vigilance and decrease pulmonary complications after cardiothoracic surgery; however, routine continuous monitoring did not reduce transfer to an ICU and did not decrease overall mortality.

Authors' conclusions

These studies confirmed that pulse oximetry can detect hypoxaemia and related events. However, we found no evidence that pulse oximetry affects the outcome of anaesthesia for patients. The conflicting subjective and objective study results, despite an intense methodical collection of data from a relatively large general surgery population, indicate that the value of perioperative monitoring with pulse oximetry is questionable in relation to improved reliable outcomes, effectiveness and efficiency. Routine continuous pulse oximetry monitoring did not reduce transfer to the ICU and did not decrease mortality, and it is unclear whether any real benefit was derived from the application of this technology for patients recovering from cardiothoracic surgery in a general care area.

Keywords: Humans; Oximetry; Anesthesia Recovery Period; Hospital Mortality; Hypoxia; Hypoxia/diagnosis; Hypoxia/mortality; Monitoring, Intraoperative; Monitoring, Intraoperative/methods; Postoperative Complications; Postoperative Complications/prevention & control; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Does monitoring oxygen level with a pulse oximeter during and after surgery improve patient outcomes?

Oxygen is carried around the body attached to haemoglobin in the blood. By passing light through the skin, pulse oximeters monitor how much oxygen the blood is carrying. Hypoxaemia—when the level of oxygen in the blood falls below optimal levels—is a risk during surgery when patient breathing and ventilation may be affected by anaesthesia or other drugs. Medical staff often monitor patients during and after surgery using pulse oximetry, but it is not clear whether this practise reduces the risk of adverse events after surgery. We reviewed the evidence on the effect of pulse oximeters on outcomes of surgical patients. In this update of the review, the search is current to June 2013. We identified five studies in which a total of 22,992 participants had been allocated at random to be monitored or not monitored with a pulse oximeter. These studies were not similar enough for their results to be combined statistically. Study results showed that although pulse oximetry can detect a deficiency of oxygen in the blood, its use does not affect a person's cognitive function and does not reduce the risk of complications or of dying after anaesthesia. These studies were large enough to show a reduction in complications, and care was taken to ensure that outcomes were assessed in the same way in both groups. The studies were conducted in developed countries, where standards of anaesthesia and nursing care are high. It is possible that pulse oximetry may have a greater impact on outcomes in other geographical areas with less comprehensive provision of health care.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Continuous pulse oximetry versus no/intermittent pulse oximetry for perioperative monitoring.

| Continuous pulse oximetry versus no/intermittent pulse oximetry for perioperative monitoring | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients undergoing surgery requiring anaesthesia Settings: Intervention: continuous pulse oximetry versus no/intermittent pulse oximetry | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Continuous pulse oximetry versus no/intermittent pulse oximetry | |||||

| Episodes of hypoxaemia (SpO2 < 90%) | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 235 (two studies) | See comment | Results not pooled. Significantly lower incidence of hypoxaemia in oximetry group in OR and in recovery room |

| Changes to patient care | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 21,037 (three studies) | See comment | Results not pooled. Two studies showed increased numbers of changes in ventilatory support and increased oxygen in oximetry group |

| Complications | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 20,802 (one study) | See comment | No reduction seen in number of cardiovascular, respiratory, neurological or infectious complications |

| In‐hospital mortality | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 22,021 (two studies) | See comment | Results not pooled. No difference in mortality between oximetry and control groups |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

Background

.

Description of the condition

Recent studies have suggested that hypoxaemia is common in the operating theatre and in the recovery room. Hypoxaemia is one of the most feared adverse events during anaesthesia and in the recovery period. For the individual patient, it is unpredictable at which level of hypoxaemia the brain, heart and other organs suffer adverse effects and to what extent irreversible damage may arise. Many factors, such as cardiac output, haemoglobin concentration and oxygen demand, affect the lowest tolerable value of oxyhaemoglobin saturation (Bendixen 1963). The occurrence and possible pathogenesis of perioperative hypoxaemia were described many years ago (Laver 1964; Nunn 1965).

Description of the intervention

The introduction of the pulse oximeter, a clinical monitor of oxygen saturation and pulsation levels, has made it possible to monitor perioperative hypoxaemia by using a non‐invasive continuous measuring technique (Severinghaus 1992). The greatest value of pulse oximetry lies in its ability to provide an early warning of hypoxaemia. Monitoring with pulse oximetry might improve patient outcomes by enabling early diagnosis and, consequently, correction of perioperative events that might cause postoperative complications or even death (Cooper 1984). An operational definition of such an event is an undesirable incident that required intervention and did, or possibly could, cause complications or death. Such events may be attributed to pathophysiological processes, malfunction of the gas supply or equipment or human error, for example, oesophageal intubation or anaesthetic mismanagement. For many of these events, hypoxaemia is possibly the most common mechanism responsible for eventual adverse outcomes (Cooper 1987).

Why it is important to do this review

Many departments and societies of anaesthesiology have adopted standards for perioperative patient monitoring, including the use of pulse oximetry, to improve anaesthesia care in accordance with the hypothesis that this may reduce perioperative complications. Monitoring with pulse oximetry permits early diagnosis and treatment of hypoxaemia, thus reducing the incidence and severity of this condition (Canet 1991; Cote 1991). Only a few randomized clinical trials of pulse oximetry performed during anaesthesia and in the recovery room describe perioperative hypoxaemic events, postoperative cardiopulmonary complications, cognitive dysfunction or admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) (Cote 1988; Cote 1991; Møller 1994; Moller 1998; Ochroch 2006). It is important to review available studies to assess whether monitoring with pulse oximetry confers long‐term benefit for patients.

Objectives

To study the use of perioperative monitoring with pulse oximetry to clearly identify adverse outcomes that might be prevented or improved by its use.

The following hypotheses were tested.

Use of pulse oximetry is associated with improvement in the detection and treatment of hypoxaemia.

Early detection and treatment of hypoxaemia reduce morbidity and mortality in the perioperative period.

Use of pulse oximetry per se reduces morbidity and mortality in the perioperative period.

Use of pulse oximetry reduces unplanned respiratory admissions to the ICU, decreases the length of ICU readmission or both.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomized and quasi‐randomized controlled trials examining the use of pulse oximetry or no pulse oximetry during the perioperative period, including in the operating theatre and in the recovery room. We included trials irrespective of blinding, numbers of participants randomly assigned or the language of the article.

Types of participants

We included patients,18 years of age and older, who were undergoing surgery with anaesthesia.

Types of interventions

We included the following intervention: monitoring with pulse oximetry compared to no monitoring with pulse oximetry during the anaesthesia and recovery periods.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome measures were postoperative complications and mortality from all causes, assessed at the end of the follow‐up period scheduled for each trial.

Any serious complications that occurred during anaesthesia or in the postoperative period: admittance to postoperative intensive care due to respiratory insufficiency, circulatory insufficiency or infection; respiratory insufficiency due to pneumonia (fever, chest x‐ray or positive culture), atelectasis (chest x‐ray) or pneumothorax (diagnosed on chest x‐ray), or requiring intervention; cardiovascular insufficiency (cardiac arrest, cardiac failure or myocardial infarction); renal and hepatic insufficiency; neurological and cognitive dysfunction (measuring memory function using the Weschler memory scale) or serious infection requiring antibiotics.

Intraoperative or postoperative mortality.

Secondary outcomes

-

Events detectable by pulse oximetry.

Hypoxaemia (pulse oximetry estimate of arterial oxyhaemoglobin saturation (SpO2) < 90%, corresponding to arterial oxygen tension < 7.9 kPa).

-

Causes of events.

Patient respiratory causes of hypoxaemia (pneumothorax, bronchospasm, air embolus, respiratory depression, apnoea, airway obstruction, pneumonia, ventilatory failure and pulmonary emboli).

Patient mechanical causes of hypoxaemia (oesophageal or main stem intubation, mucus plug or kinked endotracheal tube).

Delivery system causes of hypoxaemia (anaesthesia machine and gas supply problems).

-

Interventions that may prevent, attenuate or shorten these events include:

airway support;

endotracheal intubation;

manual or mechanical ventilation;

oxygen treatment;

pressors and inotropes; and

fluid treatment.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2013, Issue 5), see Appendix 1; MEDLINE via Ovid SP (1966 to June 2013), see Appendix 2; EMBASE via Ovid SP (1980 to June 2013), see Appendix 3; CINAHL via EBSCO host (1982 to June 2013), see Appendix 4; ISI Web of Science (1956 to June 2013), see Appendix 5; and LILACS via the BIREME interface (1982 to June 2013), see Appendix 6. The original search was performed in January 2005 with an update in May 2009.

We searched the following databases of ongoing trials by using the free‐text terms oximetry, oxymetry andpulse oximetry.

Current Controlled Trials, including the UK Clinical Trials Gateway and The Wellcome Trust.

ClinicalTrials.gov.

KoreaMed.

Indian Medlars Center (IndMED).

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry.

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP).

German Clinical Trials Register.

The Netherlands National Trial Register.

We imposed no language restrictions.

Searching other resources

We handsearched the bibliography of each article to look for relevant references.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We selected trials to be included in the systematic review based on the results of the search. For the updated search from 2009 to 2013, three review authors (KH, AN and AS) scanned the titles and abstracts of reports identified by electronic searching to produce a list of possibly relevant reports. Two review authors (AN and AS for this update; TP and AM for previous searches) independently assessed all studies for inclusion. We retrieved all eligible studies in full text.

Data extraction and management

We extracted the following data on randomization and blinding procedures.

Numbers of randomly assigned participants.

Numbers of participants not randomly assigned and the reasons for this.

Exclusion after randomization.

Dropouts.

Methods of hypoxaemia assessment in both intervention and control groups.

Methods of recording clinical interventions in both intervention and control groups.

Blinding of participants and observers.

We extracted data on perioperative complications and deaths.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool has been introduced since the last update (Higgins 2011). In this update, two review authors (AN and AS) reviewed all included studies using this tool in RevMan 5.2 to assess the quality of study design and the extent of potential bias. We considered the following domains.

Sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants, personnel and outcomes assessors.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcomes reporting.

We considered a study to be at low risk of bias from sequence generation if details of the randomization method were given, such as computer‐generated numbers or centralized randomization by telephone. We considered a study to be at low risk of bias from allocation concealment if appropriate methods were described, such as numbered or coded identical containers administered sequentially; an on‐site computer system that could be accessed only after the characteristics of an enrolled participant had been entered; or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes.

For this review topic, it is impossible for the personnel involved to be blinded to the allocation of the participant, as the intervention involves monitoring oxygen levels and then taking appropriate follow‐up action. Different patterns of care based on results of pulse oximetry are the aim of the intervention; therefore a high risk of performance bias will be inevitable. The risk of detection bias will depend on the outcome considered. Detection bias of hypoxaemia will be minimized if all participants are monitored but results are screened/ hidden from the clinical staff in the control group. Detection bias for complications and transfer to the ICU can be minimized if personnel not involved in the care of participants assess these outcomes. Mortality will be at low risk of detection bias.

Statistics

We used Review Manager version 5.2 (RevMan 5.2) in this update. The decision whether to meta‐analyse data was based on an assessment of whether study population, intervention, comparison and outcomes were sufficiently similar to ensure a clinically meaningful result.

Summary of findings

In this update, we used the principles of the GRADE system to perform an overall assessment of evidence related to each of the following outcomes (Guyatt 2008).

Complications.

Mortality.

Hypoxaemia.

Related interventions.

The GRADE approach incorporates risk of bias, directness of evidence, heterogeneity of data, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias to provide an overall measure of how confident we can be that our estimate of effect is correct. AN used GRADEPRO software to create a 'Summary of findings' table for each outcome and AS and TP reviewed and checked the table.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

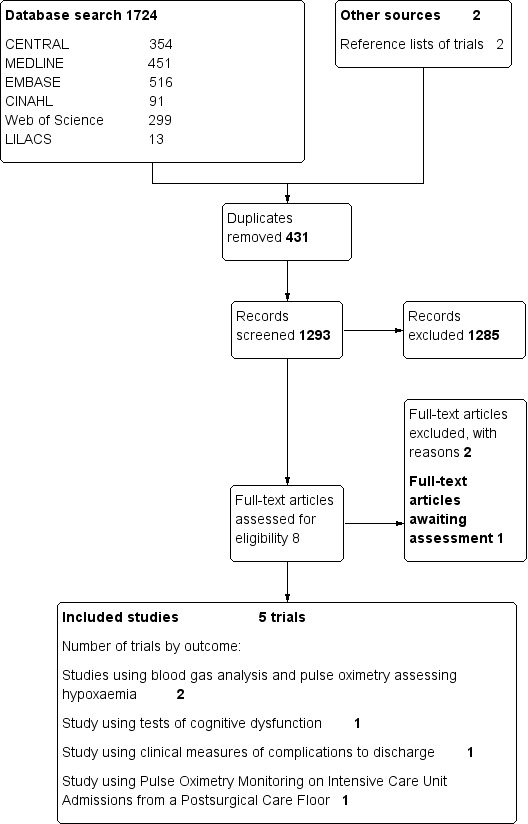

The existing review had five included studies with a total of 22,992 participants. In this new update, we found 261 new papers in our searches of electronic databases. One study was potentially eligible (Haines 2012); we reviewed this in full text but have been unable to contact the study authors to clarify eligibility (Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). We found no new studies in our updated search of clinical trial databases or review of reference lists. Overall search results for this review (including all updates) are summarized in Figure 1.

1.

Search results.

Included studies

Five studies are included in the review (Bierman 1992; Moller 1992a; Moller 1993b; Moller 1993c; Ochroch 2006) with a total of 22,992 participants. These studies are summarized in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Study populations

Two studies focused on participants undergoing cardiac surgery and studied the effect of pulse oximetry monitoring in the cardiac ICU (Bierman 1992) or in the cardiac recovery ward (Ochroch 2006) rather than during surgery. Participants in the other three included studies were undergoing general surgery and were monitored from the time arrival to the operating room (OR) until discharge from the recovery room postanaesthesia care unit (PACU).

Intervention and comparison

Intervention groups in all included studies were monitored with continuous displayed pulse oximetry, with alarms sounding in two studies (Bierman 1992; Moller 1992a), and were monitored at a telemetry station in Ochroch 2006. Methods of oxygen saturation monitoring in control groups varied and were poorly described. In two studies, the control group also received continuous pulse oximetry, but the results were not available to staff (Bierman 1992; Moller 1992a), except in cases of prolonged desaturation in one study (Bierman 1992). Intermittent blood gas readings (at least every six hours) were specified in Bierman 1992, and in Ochroch 2006 the control group received intermittent oximetry monitoring as required.

Outcomes

Four studies reported hypoxaemia outcomes in intervention and control groups (Bierman 1992; Moller 1992a; Moller 1993b; Moller 1993c). In two studies (Bierman 1992; Moller 1992a), these outcomes were based on continuous pulse oximetry monitoring in both groups, but in Moller 1993b and Moller 1993c, the method of detection of hypoxaemia differed between intervention and control groups. Three studies reported interventions or variations in care aimed at preventing or attenuating hypoxaemia and resulting complications (Bierman 1992; Moller 1993b; Moller 1993c). All three studies reported numbers of changes in ventilatory support and doses of oxygen given. Bierman 1992 and Moller 1993c also reported the numbers of blood gas analyses performed, and Moller 1993c reported on the use of pharmacological agents to reverse neuromuscular blockade or the effects of opioids.

Moller 1993c reported the incidence of a range of complications on the seventh postoperative day (POD7) or at discharge, including respiratory, cardiovascular and neurological disorders and infections. Moller 1993b reported on the cognitive function of participants before and after surgery (POD7 and in a subsample at three months). Ochroch 2006 studied the unplanned transfer of participants from the standard recovery ward to intensive care and in‐hospital mortality.

Excluded studies

We excluded two studies because of ineligible design (Cullen 1992; Mateer 1993). See Characteristics of excluded studies for additional details.

Risk of bias in included studies

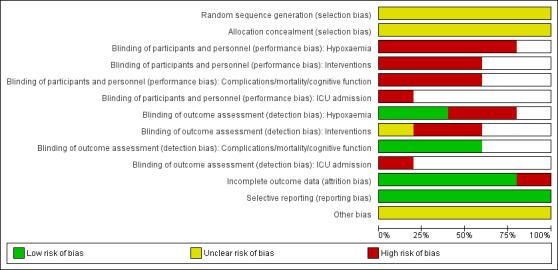

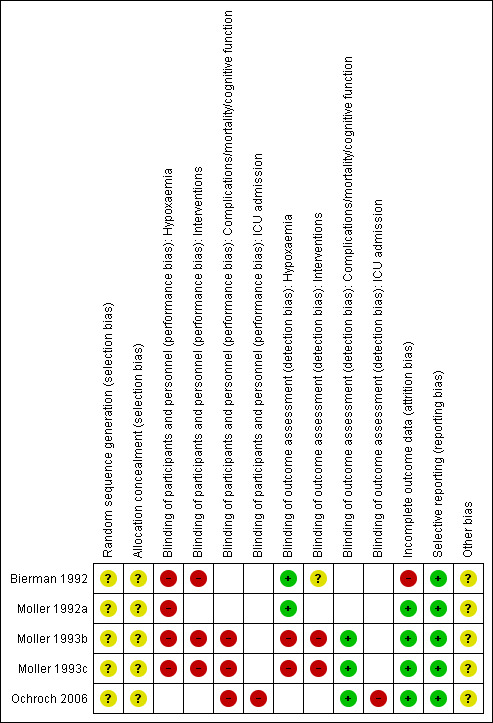

Risk of bias assessments for included studies are summarized in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

All of the included studies gave insufficient details concerning random sequence generation and allocation concealment, and we rated all studies to be at unclear risk of selection bias. Two studies used a cluster‐randomized design with operating theatres randomly assigned to using or not using pulse oximetry after participants undergoing elective surgery had been allocated to lists, with emergency cases assigned by drawing envelopes from a stack (Moller 1993b; Moller 1993c). Three studies mentioned the use of sealed envelopes but did not give full details of whether the envelopes were opaque and sequentially numbered (Moller 1993b; Moller 1993c; Ochroch 2006).

Blinding

In all included studies, study personnel were not blinded to participant allocation and were able to modify the care received according to pulse oximetry results. We therefore concluded that all studies were at high risk of performance bias for all outcomes.

In two studies (Bierman 1992; Moller 1992a), hypoxaemia was assessed by pulse oximetry in both control and intervention groups, and the data were recorded automatically. We rated these studies at low risk of detection bias for hypoxaemia. In Moller 1993b and Moller 1993c, the method of detection of hypoxaemia in the control group was not fully described and relied on clinical observation and arterial blood gas analysis. We considered the hypoxaemia outcome to be at high risk of detection bias in these studies.

In Moller 1993b and Moller 1993c, OR personnel, who were aware of participants' allocation, recorded changes to participant care. However, staff who assessed postoperative complications or cognitive function were unaware of participant allocation. We considered that these studies were at high risk of detection bias for changes to participant care but at low risk of detection bias for complications. In Bierman 1992, it was unclear how changes to participant care were recorded. In Ochroch 2006, staff on the ward made the decision to transfer a participant to ICU with no standardized criteria reported. We considered this outcome to be at high risk of detection bias, but in‐hospital mortality to be at low risk.

Incomplete outcome data

Dropout rates varied between 5% and 10% in all included studies, with a maximum of 14.6% in Moller 1993b due to the more complicated cognitive function test. We considered most studies to be at low risk of attrition bias because the attrition rate was similar in both groups. Bierman 1992, however, reported more withdrawals from the control group due to technical problems.

Selective reporting

We found no evidence of selective reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Most studies were supported in some way by the manufacturers of the monitoring equipment. In most studies, this took the form of the loan of the equipment. Nellcor supported Ochroch 2006 with an unsupported grant. The role and precise involvement of the manufacturers were unclear.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Searching yielded five reports. All outcome measures in the included studies were extracted and are detailed in the table Characteristics of included studies. The types of outcome measures were separated into perioperative complications and events detectable by pulse oximetry that could result in complications. This is considered in the same way below.

Studies used various ways to assess postoperative outcomes.

Events with hypoxaemia measured with blood gas analysers or pulse oximetry (two trials).

Tests of cognitive function: Wechsler memory scale, continuous reaction time and subjective perception of cognitive dysfunction (test of memory) (one trial).

Clinical outcomes: respiratory, cardiovascular and neurological complications following anaesthesia (one trial).

Unplanned respiratory admissions to the ICU, decreased length of ICU readmission or both (one trial).

Due to the variety of study population, comparison group and outcome variables in the five studies, there are no two groups which could be combined by formal meta‐analysis.

Incidence of hypoxaemia

Both studies assessed as having low risk of detection bias for hypoxaemia found an increased incidence of hypoxaemia in the control group. In the study of Bierman 1992, clinically unapparent desaturations were detected in seven of 15 participants in the control group without pulse oximetry compared with none in the pulse oximetry group. Moller 1992a found that hypoxaemia was reduced in the pulse oximetry group, both in the operating theatre and in the recovery room. During observation in the recovery room, the incidence of hypoxaemia in the pulse oximetry group was 1.5 to three times less, and no participant experienced extreme or severe hypoxaemia. In the pulse oximetry group, the lowest recorded SpO2 value in the recovery room (mean 89.4%) was greater than the value in the group without pulse oximetry (mean 87.2%).

Both of the studies at high risk of detection bias for hypoxaemia reported an increased incidence of hypoxaemia in the intervention group. In Moller 1993c, hypoxaemia was detected in 818/10,312 (7.9%) in the oximetry group compared with 41/10,490 (0.4%) in the control group. In this study, a higher rate of hypoventilation and endobronchial intubation was reported in the oximetry group, consistent with better identification of ventilation problems in the oximetry group. In Moller 1993b, 7.8% of participants in the oximetry group were diagnosed with hypoxaemia in the OR and 11.7% in the recovery room compared with 0.3% in the OR and 0.5% in the OR for participants in the control group.

Changes in patient care

In Bierman 1992, the number of changes in ventilatory support per postoperative intensive care unit (ICU) stay was not different between groups, whereas the dose of supplemental oxygen was adjusted more frequently (usually lowered) in the group without pulse oximetry. No evidence was found of a significant difference between groups regarding the duration of postoperative mechanical ventilation or ICU stay. In Moller 1992a, participants in the oximetry group were more likely to receive supplemental oxygen (45% compared with 35% receiving more than 3 L/min of oxygen in the recovery room). Moller 1993c also reported increased use of supplemental oxygen in the PACU in the oximetry group (6.5% receiving more than 3 L/min compared with 2.8% in the control group). The proportion of participants discharged from the recovery room with an order for supplemental oxygen was 13.3% in the oximeter group and 3.5% in the control group.

In Bierman 1992, the number of blood gas analyses was greater in the control group than in the oximetry group (mean 23.2 (standard deviation (SD) 8.8) vs 12.4 (7.5); P < 0.001). By contrast, Moller 1993c found no difference between groups. This is likely to reflect the protocol in Bierman 1992, which specified blood gas analyses at least every six hours in the control group.

In Moller 1993c, more participants in the oximetry group received naloxone, and these individuals had a longer stay in the PACU. The higher proportion of participants treated with naloxone in the oximetry group may be an example of how the oximeter readings pointed to a problem to which the staff reacted.

Cognitive dysfunction

Moller 1993b demonstrated that postoperative cognitive function, as measured by the Wechsler memory scale and by continuous reaction time, was independent of perioperative monitoring with pulse oximetry. Postoperative subjective reports (by questionnaire) of cognitive deficits revealed no statistically significant difference: 7% in the pulse oximetry group and 11% in the group without pulse oximetry believed their cognitive abilities had decreased. No statistically significant difference was noted in the ability to concentrate (10% vs 9%). This study reported no evidence of lessened postoperative cognitive impairment after perioperative monitoring with pulse oximetry.

Clinical measures of complications to the time of discharge

The study of Moller 1993c, including 20,802 surgical participants randomly assigned to monitoring with pulse oximetryor no monitoring, found that one or more postoperative complications occurred in 10% of participants in the oximetry group and in 9.4% in the control group. The two groups did not differ in the number of cardiovascular, respiratory, neurological, or infectious complications. The duration of hospital stay was a median of five days in both groups. An equal number of in‐hospital deaths occurred in the two groups: 1.1% in the oximeter group and 1.0% in the control group; a total of seven deaths were classified as possibly anaesthesia related: three deaths in the oximetry group and four in the control group. The seven deaths did not display any specific pattern. A questionnaire completed by the anaesthesiologists revealed that 18% of them had experienced a situation in which a pulse oximeter had helped to avoid a serious event or complication, and that 80% felt more secure when they used a pulse oximeter. Although monitoring with pulse oximetry prompted several changes in participant care, no evidence showed a reduction in the overall rate of postoperative complications when perioperative pulse oximetry was used.

The study of Ochroch 2006 also reported no difference in in‐hospital mortality between intervention and control groups, with 14 deaths among 589 participants (2.4%) in the intervention group and 14 among 630 (2.2%) in the control group.

Intensive care unit admissions from postsurgical care

The study of Ochroch 2006 included 1219 participants enrolled from approximately 8300 patients who met the eligibility criteria. Rates of readmission to the ICU were similar in monitored and unmonitored groups. Of the 93 participants (8% of all participants) who were transferred to the ICU after enrolment, 40 were in the monitored group of 589 participants (6.7%) and 53 were in the unmonitored group of 630 participants (8.5%) (P = 0.33). Participants transferred to the ICU did not differ from those not transferred to the ICU (“discharged”) in terms of age, gender, race or surgical service. Starting in the cardiothoracic intensive care unit (CTICU) before transfer to the study floor was significantly associated with return to an ICU (odds ratio (OR) 2.1; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.3 to 4.9; P= 0.001). Reasons for transfer back to the ICU (determined by blinded review of ICU transfer notes) differed between monitored and unmonitored groups, with more pulmonary events reported in the unmonitored group compared with the continuous pulse oximetry (CPOX) monitored group (27/630 vs 8/ 589; P = 0.002). The use of CPOX did not impact on duration of stay in the hospital or total estimated cost of hospitalization when the entire cohort was examined. Routine CPOX and usual care groups had similar numbers of days from enrolment to discharge from the study, numbers of days from enrolment to discharge from the hospital, estimated costs while on the study floor and estimated costs for the entire hospital stay. The effects of death on study outcomes were assessed by reexamining study outcomes in a sensitivity analysis without including data from these participants. Deaths did not affect outcomes and did not produce or enhance differences between groups.

Discussion

Methodological quality

Statistical analysis of data

Summary of main results

The latest updated search added no new studies, but the included studies confirmed that pulse oximetry improves the detection of hypoxaemia and related events such as hypoventilation. Alterations to participant care were more frequent in monitored participants. However, no evidence suggests that continuous monitoring with pulse oximetry reduced the incidence of postoperative complications or mortality (Table 1).

Perioperative hypoxaemia and postoperative complications

Comparisons of overall rates of perioperative hypoxaemia and postoperative complications are difficult with the present randomized studies because of the limited numbers of studies and participants, and because of differences in the types of outcomes investigated. It appears that general rates of hypoxaemia and complications in the present studies are at the same level as those reported in other studies (Mlinaric 1997; Moller 1998; Pedersen 1994; Rheineck 1996; Stausholm 1997).

The demonstration of reduced extent of hypoxaemia and the ability to detect and correct potentially harmful events and to make several changes in patient care with pulse oximetry monitoring contrast with the fact that no reduction in the number of postoperative complications was found (Moller 1993c). The fact that patients monitored with pulse oximetry have no change in outcome, despite the fact that they tend to be given more oxygen and naloxone (Moller 1993c), is worth emphasizing. It indicates that merely increasing saturation levels from marginal to satisfactory probably is not going to make a difference in patient outcomes. In other words, the use of pulse oximetry as an early warning of moderate hypoxaemia does not appear to be beneficial even if the appropriate responses are instituted earlier than they would have been without pulse oximetry. This result conflicts with most anaesthesiologists' beliefs. In the closed claims analyses of adverse respiratory events in anaesthesia, the authors judged that better monitoring would have prevented adverse outcomes in 72% of the claims (Caplan 1990; Tinker 1989). In the general analysis of the role of monitoring devices in the prevention of anaesthetic mishaps, nearly 60% of the instances of death and brain damage were considered preventable by application of additional monitors. These studies have several limitations, including absence of a control group, a probable bias toward adverse outcomes and reliance on data provided by participants rather than by objective observers.

Postoperative cognitive dysfunction

The relationship between perioperative hypoxaemia and impaired postoperative cognitive function is debated (Krasheninnikoff 1993). Moller 1993b found that 9% of surgical participants thought that their mental function had deteriorated. In a more recent study (Moller 1998), postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the elderly, as identified by neuropsychological tests, was present in 25.8% of participants one week after surgery, and in 9.9% three months after surgery. However, hypoxaemia was not a significant risk factor for cognitive dysfunction at any time. Perioperative monitoring with pulse oximetry did not appear to affect participants' postoperative cognitive function. Tests of cognitive function are valuable in the study of anaesthetic drug effects, but many participants had unexplained complaints of impaired cognitive function that were not verified by objective tests (Moller 1998). One may speculate that application of a broader range of neuropsychological assessments than were used in the Moller 1998 study could have detected varying deficits of an enduring nature. Using a broad range of tests, investigators have described moderate to severe cognitive dysfunction that lasted for several months after coronary bypass surgery (Townes 1989).

Pulse oximetry monitoring on intensive care unit admissions from postsurgical care

The randomized clinical trial of third‐generation CPOX technology (Ochroch 2006) reported that routine CPOX monitoring was not associated with an overall decreased transfer to ICU or with mortality. In this population of patients after cardiothoracic surgery, the use of CPOX was associated with reduced postoperative ICU admissions for pulmonary complications. It is possible that CPOX monitoring increases overall nursing vigilance, resulting in increased non‐respiratory ICU transfers. If appropriate, such transfers may contribute to the benefits of CPOX observed in this study. If such transfers represent inappropriately aggressive care, then there is the potential for routine CPOX monitoring to further reduce ICU readmissions with further training of nurses. If a real benefit of CPOX is seen in reduced ICU transfer, then lack of reduction in the absolute rate of return to an ICU by CPOX use can also be considered a dilutional effect. The large group of participants who did well regardless of the monitoring overwhelms any beneficial effect of monitoring in the much smaller group, which may have benefited from the monitoring. This is similar to perioperative data, which show a decreased rate of hypoxaemia when pulse oximetry is used (Moller 1992a) but no change in rare outcomes (myocardial infarction, stroke and death) (Moller 1993c).

Anaesthetists' perception of risk

The study of Moller 1993c showed that 18% of participating anaesthesiologists reported one or more situations in which they thought pulse oximetry helped to avoid a serious event or complication. This subjective reporting suggests an effect of pulse oximetry monitoring on outcome, but objective figures for the rate of postoperative complications do not confirm this. A large contrast was also evident between the objective results of the study of Moller 1993c and the subjective opinions of participating anaesthesiologists regarding the usefulness of pulse oximetry.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The included studies come from countries (USA and Denmark) where standards of anaesthesia and nursing care are high. Almost all of the data were collected by a single group of investigators in Denmark (Moller 1992a; Moller 1993b; Moller 1993c). This reduces the generalizability of the results in terms of what might be found in other geographical areas where standards of care and assessment methods may be lower and pulse oximetry may have a greater impact on outcomes. Because the detected hypoxic events were treated, we do not really know what the differences in outcomes would have been if hypoxic events were neither detected nor treated. The studies were relatively well controlled and did not reproduce situations with a high likelihood of disaster.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of randomization and allocation concealment in the included studies was often unclear from the study report, but there was nothing to suggest processes that introduced bias. Blinding of personnel to the allocation was impossible for this topic, and so all outcomes were at high risk of performance bias. The intervention being tested in practise is oximetry monitoring and resulting changes to care. Two studies paid careful attention to reducing detection bias for complications (Moller 1993b; Moller 1993c), but other studies had the potential for increased detection of outcomes in the intervention group (Ochroch 2006). Although power analyses were not reported, Moller 1993c had a sufficient sample size to detect a change in complication rates from 9.5% to 8% with 80% power at 5% significance. It is therefore unlikely that a substantial reduction in complications was missed by this study.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The proliferation of monitors in anaesthesia is obvious. The goal of monitoring as an adjunct to clinical decision making is to directly reduce the incidence of complications. This is based on the premise that unambiguous and accurate information, which is readily interpretable and available, will help the anaesthesiologist in choosing and initiating correct therapeutic interventions. The unanswered question is whether the individual anaesthesiologist's performance—the human factor—is perhaps far more important than implementing new monitoring equipment or other new safety initiatives in a situation in which we wish to reduce the rate of postoperative complications. However, we do not know whether pulse oximetry might protect against the human factor when that factor is negligent.

Pulse oximetry monitoring substantially reduced the extent of perioperative hypoxaemia, enabled the detection and treatment of hypoxaemia and related respiratory events and promoted several changes in patient care. The implementation of perioperative pulse oximetry monitoring was not, however, the breakthrough that could reduce the number of postoperative complications. The question remains whether pulse oximetry improves outcomes in other situations. Pulse oximetry has already been adopted into clinical practice all over the world. It may be a tool that guides anaesthesiologists in the daily management of patients, in teaching situations, in emergencies and especially in caring for children. Although results of studies are not conclusive, the data suggest that there may be a benefit for a population at high risk of postoperative pulmonary complications. Results of the studies of general surgery indicate that perioperative monitoring with pulse oximetry does not improve clinically relevant outcomes, effectiveness or efficiency of care despite an intense, methodical collection of data from a large population.

Implications for research.

The science of human factors includes the psychological and mental factors that affect performance in the workplace. Monitoring systems should fit naturally with the way the anaesthesiologist works, thinks and interacts with the patient, the equipment and the operating room environment, so monitoring systems can, together with vigilance and clinical decision making, bring significant benefit.

Existing evidence demonstrates that pulse oximetry reduces the incidence of hypoxaemia but does not improve overall patient outcomes and does not reduce morbidity and mortality. We found no RCTs on pulse oximetry published after 2006. The use of oximeters is now so widespread that many anaesthesiologists in the developed world will not consider working without one. It is therefore uncertain whether any new large RCTs are likely to be performed (Shah 2013). All existing studies were conducted in affluent Western hospitals with good standards of patient care. The benefit of pulse oximetry monitoring has not been evaluated in more challenging healthcare settings, but there may be ethical queries about such studies.

The potential for continuous pulse oximetry to allow early intervention, or perhaps prevention of pulmonary complications, needs to be explored. Future studies might usefully include an evaluation of clinicians’ responses to oximetry readings, perhaps shaped by clinical pathways or protocolized interventions. As the present studies illustrate, the problems are multitudinous. The worst problem is clearly the huge numbers of participants needed. By limiting the inclusion criteria to a specific subgroup of participants (e.g. participants older than 65 years, with cardiac risk factors, with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status III and IV or undergoing acute abdominal surgery), isolating more rigorous outcome variables and establishing wide co‐operation between departments and countries, new monitoring and anaesthesia safety studies could be launched in the future.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 March 2014 | New search has been performed | The existing search strategy was updated from May 2009 to June 2013. This yielded 261 new potential titles. We found no new included studies, but one additional study is awaiting assessment The review was converted to new review format, and we used the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool to assess the quality of included studies. We added a 'Summary of findings' table |

| 14 March 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | This review is an update of the previous Cochrane systematic review

(Pedersen 2009), which included five RCTs. Three new authors joined the review team for this update: Amanda Nicholson, Andrew Smith and Sharon Lewis. The contact person has been changed to Amanda Nicholson Our review reached the same conclusions as were reached in the previous version |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2000 Review first published: Issue 3, 2001

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 October 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 7 September 2009 | Amended | New order of authors, previously: Pedersen T, Møller AM, Hovhannisyan K; now:Møller AM. |

| 15 May 2009 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | A new author Karen Hovhannisyan has joined the review team. He replaces Bente Dyrlund Pedersen who co‐authored Pedersen 2003a. |

| 15 May 2009 | New search has been performed | We re‐ran the search strategy in all the databases up to May 2009. We searched three new databases (CINAHL, ISI Web of Science, and LILACS). We retrieved 133 studies. We identified and included one new randomized controlled trial in the review (Ochroch 2006). This new study has not changed the review's conclusion. |

| 16 January 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 27 July 2005 | New search has been performed | Second Update, Issue 4, 2005: We found no new randomized controlled trials examining the impact of perioperative monitoring with pulse oximetry. |

| 31 January 2003 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | First Update, Issue 2, 2003. We found no new randomized controlled trials examining the impact of perioperative monitoring with pulse oximetry. |

Acknowledgements

We thank Mathew Zacharias and Rodrigo Cavallazzi for editing the current updated version of this review.

We would like to acknowledge Nete Villebro, Janet Wale and Kathie Godfrey for their contributions to the plain language summary in the previous review (Pedersen 2005). We also would like to acknowledge Dr Bente Dyrlund Pedersen's contributions to our previous review (Pedersen 2003a).

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy for CENTRAL

#1 (operation or peri?op* or post?op* or intra?op* or surg*):ti,ab #2 (pulse near ox?met*) #3 MeSH descriptor Oximetry explode all trees #4 (#1 AND ( #2 OR #3 ))

Appendix 2. Search strategy for MEDLINE (Ovid SP)

1 (operation or perioperat* or postoperat* or intraoperat* or surg*).mp. 2 ((pulse adj6 oximet*) or (pulse adj6 oxymet*)).mp. or exp Oximetry/ or oxymet*.ti,ab. 3 ((randomized controlled trial or controlled clinical trial).pt. or randomized.ab. or placebo.ab. or clinical trials as topic.sh. or randomly.ab. or trial.ti.) and humans.sh. 4 1 and 3 and 2

Appendix 3. Search strategy for EMBASE (Ovid SP)

1 (operation or perioperat* or postoperat* or intraoperat* or surg*).mp. 2 exp Pulse Oximetry/ or exp Oximetry/ 3 ((pulse adj6 oximet*) or (pulse adj6 oxymet*) or oxymet* or oximet*).mp. 4 3 or 2 5 (placebo.sh. or controlled study.ab. or "random*".ti,ab. or trial*.ti.) and human*.ec,hw,fs. 6 1 and 4 and 5

Appendix 4. Search strategy for CINAHL (EBSCO host)

S1 TX (operation or perioperat* or postoperat* or intraoperat* or surg*) S2 (MH "Perioperative Care+") S3 (MH "Postoperative Care+") S4 (MH "Intraoperative Care+") or (MH "Intraoperative Monitoring+") S5 S4 or S3 or S2 or S1 S6 (MM "Pulse Oximeters") or (MM "Pulse Oximetry") S7 TX (pulse and ox?met*) S8 S7 or S6 S9 S8 and S5 S10 (MM "Random Assignment") or (MH "Clinical Trials+") S11 AB random* S12 TI trial S13 AB placebo S14 S13 or S12 or S11 or S10 S15 S14 and S9

Appendix 5. Search strategy for ISI Web of Science

# 1 TS=(operation or perioperat* or postoperat* or intraoperat* or surg*) # 2 TS=((pulse SAME oximet*) or (pulse SAME oxymet*) or oxymet*) # 3 #2 AND #1 # 4 TS=(random* or ((controlled or clinical) SAME trial*) or placebo) # 5 #4 AND #3

Appendix 6. Search strategy for LILACS (BIREME)

("OXYMETER" or "OXYMETRY" or "puls oximet$") and (operation or perioperat$ or postoperat$ or intraoperat$ or surg$)

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bierman 1992.

| Methods | Single‐centre RCT. Cardiac ICU, University Hospital, Pittsburgh, USA | |

| Participants | 35 participants undergoing cardiac surgery | |

| Interventions | Intervention group: N = 20. Pulse oximetry (NellcorN‐200) by bedside. Finger/earlobe probe. Alarms on. Continuous access and monitoring in lieu of blood gases but blood gases whenever required, at least each morning Control group: N = 15. Pulse oximetry (NellcorN‐200). Finger/earlobe probe. Readout by bedside masked and data transmitted to remote site. Blood gases at least every six hours. Bedside nurse notified of hypoxic episodes < 90% SpO2 >5 minutes or SpO2 between 90% and 93% lasting > 10 minutes | |

| Outcomes | Clinically undetected hypoxic episodes < 94% Number of blood gas analyses Length of stay in ICU Changes in ventilator support and blood gas . |

|

| Other monitoring | Continuous arterial BP, pulmonary art pressure, ECG and mixed venous saturation monitoring | |

| Location and duration of monitoring | Participants monitored from arrival on cardiac ICU. Not clear how long monitoring continued | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "patients were randomly assigned". No further details |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "patients were randomly assigned". No further details |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Hypoxaemia | High risk | Staff responded to available data and modified treatment accordingly |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Interventions | High risk | Staff responded to available data and modified treatment accordingly |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Hypoxaemia | Low risk | Same monitors used in intervention and control groups. Trend recordings printed every 12 hours and examined to determine number and duration of desaturations to < 94% |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Interventions | Unclear risk | Not clear whether information on interventions was based on automated data or was manually recorded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 1/ 21 withdrawn from intervention group because of cardiovascular problems 3/18 withdrawn from control group: two for problems with telemetry and one because of respiratory problems |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes specified in Methods reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Nellcor loaned telemetry system and two pulse oximeters |

Moller 1992a.

| Methods | Two‐centre RCT: one teaching hospital and one major hospital in Denmark | |

| Participants | 200 adult participants undergoing elective surgery expected to last longer than 20 minutes and performed under general, spinal or epidural anaesthesia | |

| Interventions | Intervention group: N = 100. Available pulse oximetry (Radiometer/Ohmeda). Alarms on. Finger probe Control group: N = 100. Pulse oximetry (Radiometer/Ohmeda) in sealed box. Data stored. Alarms off. Finger probe |

|

| Outcomes | Episodes of hypoxia: mild 86% to 90% oxygen saturation, moderate 81% to 85%; severe 76% to 80%; extreme < 76% Time spent hypoxic < 90% SpO2 |

|

| Other monitoring | OR: ECG, arterial pressure every 5 minutes, central venous pressure (CVP) if indicated Recovery ECG and CVP continuous BP, HR and respiratory rate every 15 minutes |

|

| Location and duration of monitoring | Monitoring in OR and in recovery room. From arrival in OR to discharge from recovery room or after six hours if still in recovery room | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "patients allocated randomly to two group(s)". No further details given |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "patients allocated randomly to two group(s)". No further details given |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Hypoxaemia | High risk | Staff responded to available data and modified treatment accordingly |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Hypoxaemia | Low risk | Same monitors in use in intervention and control groups. Data stored electronically |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 4/104 in intervention group & 2/ 102 in control group excluded because of lack of co‐operation or poor peripheral perfusion |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes specified in Methods reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Ohmeda and Radiometer provided meters for the study |

Moller 1993b.

| Methods | Two‐centre cluster‐randomized RCT: one teaching hospital and one major hospital in Denmark | |

| Participants | 736 adult participants undergoing elective surgery expected to last longer than 20 minutes and performed under general, spinal or epidural anaesthesia. Each day, four participants from each surgical department selected for cognitive testing | |

| Interventions | Intervention group: N = 358. pulse oximetry (Radiometer/Ohmeda). Intervene if SpO2< 93%. Finger probe Control group: N = 378. Not monitored by pulse oximetry at any time | |

| Outcomes | Incidence of hypoxia during anaesthesia defined as cyanosis, arterial oxygen < 7.8 kPa, SaO2 < 90%, or SpO2 < 90% Changes to patient care Cognitive function (Wechsler memory scale): preoperatively, POD7. Participants with score decreased by 10 or more points were tested again after three months Participant–reported assessment of whether cognitive abilities had changed following anaesthesia at six weeks postoperatively |

|

| Other monitoring | OR: ECG, arterial pressure every 5 minutes, CVP if indicated Recovery room ‐ECG & CVP continuously. BP, HR & respiratory rate every 15 minutes. |

|

| Location and duration of monitoring | Monitoring in the operating theatre and in the recovery room. Monitored from just before induction until discharge from recovery room | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | ORs were cluster‐randomized on a daily basis after participants had been assigned. No details of randomization method |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation sent in sealed envelope after allocation of participants. No possibility of changing participants. For emergency cases, an envelope containing the random assignment was drawn from a stack |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Hypoxaemia | High risk | Staff responded to available data and modified treatment accordingly |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Interventions | High risk | Staff responded to available data and modified treatment accordingly |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Complications/mortality/cognitive function | High risk | Staff responded to available data and modified treatment accordingly |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Hypoxaemia | High risk | Hypoxia detection differed in intervention and control groups and was recorded by OR personnel who were not blinded to participant allocation |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Interventions | High risk | Changes in care recorded by OR personnel who were not blinded to participant allocation |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Complications/mortality/cognitive function | Low risk | Nurses undertaking cognitive function testing unaware of allocation. Patient reported outcome unclear |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 125/861 (14.6%) participants did not complete study, but equally distributed between intervention and control groups |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes specified in Methods reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Statistical methods have not allowed for clustering Ohmeda and Radiometer provided meters for study Many other funders listed. None obviously commercial |

Moller 1993c.

| Methods | Multi‐centre cluster‐randomized RCT, three teaching hospitals and two major hospitals in Denmark Not blinded, elective participants were assigned to an operating room the day before surgery, and pulse oximeters were assigned to operating rooms randomly |

|

| Participants | 20,802 adult participants undergoing elective surgery expected to last longer than 20 minutes and performed under general, spinal or epidural anaesthesia | |

| Interventions | Intervention group: N = 10,312. Pulse oximetry (Radiometer/Ohmeda). Intervene if SpO2 < 93%. Finger probe Control group: N = 10,490. No monitoring |

|

| Outcomes | Incidence of hypoxia during anaesthesia defined as cyanosis, arterial oxygen < 7.8 kPa, SaO2 < 90% or SpO2 < 90% Events during monitoring: Changes to patient care Postoperative complications: respiratory, cardiovascular, neurological and infectious; duration of recovery room stay and ICU admittance. At POD7 or discharge Death |

|

| Other monitoring | OR: ECG, arterial pressure every 5 minutes, CVP if indicated Recovery room: ECG and CVP continuously. BP, HR and respiratory rate every 15 minutes |

|

| Location and duration of monitoring | Participants assigned a pulse oximeter were monitored from just before induction of anaesthesia until discharge from the PACU | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | ORs were cluster‐randomized on a daily basis after participants had been assigned. No details of randomization method |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation sent in sealed envelope after allocation of participants. No possibility of changing participants. For emergency cases, an envelope containing the random assignment was drawn from a stack |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Hypoxaemia | High risk | Staff responded to available data and modified treatment accordingly |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Interventions | High risk | Staff responded to available data and modified treatment accordingly |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Complications/mortality/cognitive function | High risk | Staff responded to available data and modified treatment accordingly |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Hypoxaemia | High risk | Hypoxia recorded by OR personnel (form A). These staff members were not blinded, and methods for detecting hypoxaemia differed in the two groups |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Interventions | High risk | Changes in care recorded by OR personnel (form A). These staff members were not blinded to allocation |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Complications/mortality/cognitive function | Low risk | Form B for complications completed by staff unaware of allocation. Standardized definitions for complications |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 938/21,740 excluded: 366 because participant was receiving a second anaesthetic during admission, 475 for randomizing errors. Exclusions were equally distributed between control and intervention groups |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes specified in Methods reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Statistical methods have not allowed for clustering Ohmeda and Radiometer provided meters for study |

Ochroch 2006.

| Methods | Single‐centre RCT. University hospital, Philadelphia, USA | |

| Participants | 1219 participants recovering from cardiac and thoracic surgery | |

| Interventions | Intervention group: N = 589. Continuous monitoring using Nellcor central station network CPOX system Oxinet II via telemetry station Control group: N = 630. Intermittent assessment as nurse required. Standalone monitors available. “Typical use" |

|

| Outcomes | Admission to ICU Reason for transfer Length of stay in ICU Costs of hospital stay In‐hospital mortality |

|

| Other monitoring | Concurrent continuous ECG telemetry | |

| Location and duration of monitoring | Surgery care ward—telemetry station. USA. Monitored from admission to discharge/transfer to ICU/other ward | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "randomly generated group assignments". No further details |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "Sequential sealed envelopes". No further details |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Complications/mortality/cognitive function | High risk | Staff responded to available data and modified treatment accordingly |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) ICU admission | High risk | Staff responded to available data and modified treatment accordingly |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Complications/mortality/cognitive function | Low risk | In‐hospital mortality at low risk of bias |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) ICU admission | High risk | No standardized admission criteria. Blinded chart review, but staff completing charts were not blinded. Reasons for admissions differed between groups |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No apparent losses |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes specified in Methods reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Only 1219 of a total of 8300 potential participants enrolled. Not clear why so many participants not enrolled, possibly related to nurse staffing levels Study funded by Nellcor—unrestricted grant |

ICU: Intensive care unit. N: Numbers. PACU: Postanaesthesia care unit.

CVP: Central venous pressure.

OR: Operating room.

BP: Blood pressure.

HR: Heart rate.

SpO2 (%): Saturation level of oxygen in haemoglobin, estimated from pulse oximetry.

SaO2 (%): Saturation level of oxygen in haemoglobin, measured in arterial blood.

PaO2: Partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood.

POD: Postoperative day. Day of surgery = POD0

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Cullen 1992 | A non‐randomized study of 17,093 surgical participants expected to enter the recovery room and then return to floor care. During the first 28 weeks of the study, only seven pulse oximeters were available for shared use in 51 ORs. For the subsequent 37 weeks, pulse oximeters were placed and were used on essentially all participants in all 51 anaesthetizing locations |

| Mateer 1993 | A non‐randomized study of 191 consecutive adult participants to determine whether pulse oximetry improves recognition of hypoxaemia during emergency endotracheal intubation. An observation period of complications lasted only five minutes after intubation, and no events or complications were observed during anaesthesia or in the postoperative period |

min: Minutes. OR: Operating room.

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Haines 2012.

| Methods | Published in abstract only. Unclear design. May not be a randomized trial |

| Participants | 32 participants undergoing bariatric surgery |

| Interventions | Continuous pulse oximetry in 24 hours postoperatively versus intermittent pulse oximetry |

| Outcomes | Episodes of hypoxaemia |

| Notes | Study author emailed on 30/9/2013 |

Differences between protocol and review

The Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool was used in this update to assess the quality of included studies, and a 'Summary of findings' table was included.

Contributions of authors

Tom Pedersen (TP), Amanda Nicholson (AN), Karen Hovhannisyan (KH), Ann Merete Møller (AM), Andrew F Smith (AS), Sharon R Lewis (SL)

Conceiving the review: TP, AM

Co‐ordinating the review: TP, AM

Undertaking electronic and manual searches: TP, AM, KH

Screening search results: TP, AM, KH, AN

Organizing retrieval of papers: KH

Screening retrieved papers against inclusion criteria: TP, AM, KH, AN,AS

Appraising quality of papers: TP, AM, AN, AS

Extracting data from papers: TP, AM, AN

Writing to authors of papers for additional information: TP

Obtaining and screening data on unpublished studies: TP

Data management for the review: TP, AM

Entering data into Review Manager (RevMan 5.2): TP, KH

RevMan statistical data: TP, AM

Other statistical analysis not using RevMan: TP, AM

Double entry of data: TP, AM

Interpretation of data: TP, AM

Statistical inferences: TP, AM

Writing the review: TP, AM, KH, AN, SL

Securing funding for the review: TP

Guarantor for the review (one author): TP

Person responsible for reading and checking review before submission: TP

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

-

NIHR Cochrane Collaboration Programme Grant. Enhancing the safety, quality and productivity of perioperative care. Project Ref: 10/4001/04, UK.

- This grant funds the work of AN, AS and SL on this review

Declarations of interest

Tom Pedesen is a co‐author of one study included in the review (Moller 1993c).

Amanda Nicholson: From March to August 2011, AN worked for the Cardiff Research Consortium, which provided research and consultancy services to the pharmaceutical industry. The Cardiff Research Consortium has no connection with AN's work with The Cochrane Collaboration. AN's husband has small direct holdings in several drug and biotech companies as part of a wider balanced share portfolio. See Sources of support.

Karen Hovhannisyan: none known.

Ann Merete Møller: none known.

Andrew F Smith: none known.

Sharon R Lewis: none known.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Bierman 1992 {published data only}

- Bierman MI, Stein KL, Snyder JV. Pulse oximetry in the postoperative care of cardiac surgical patients. Chest 1992;102:1367‐70. [PUBMED: 1424853] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moller 1992a {published data only}

- Moller JT, Jensen PF, Johannessen NW, Espersen K. Hypoxaemia is reduced by pulse oximetry monitoring in the operating theatre and in the recovery room. British Journal of Anaesthesia 1992;68(2):146‐50. [PUBMED: 1540455] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moller 1993b {published data only}

- Moller JT, Svennild I, Johannessen NW. Perioperative monitoring with pulse oximetry and late postoperative cognitive dysfunction. British Journal of Anaesthesia 1993;71(3):340‐7. [PUBMED: 8398512] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moller 1993c {published data only}

- Moller JT, Johannessen NW, Espersen K, Ravlo O, Pedersen BD, Jensen PF, et al. Randomized evaluation of pulse oximetry in 20,802 patients: II. Perioperative events and postoperative complications. Anesthesiology 1993;78(3):445‐53. [PUBMED: 8457045] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller JT, Pedersen T, Rasmussen LS, Jensen PF, Pedersen BD, Ravlo O, et al. Randomized evaluation of pulse oximetry in 20,802 patients: I. Design, demography, pulse oximetry failure rate, and overall complication rate. Anesthesiology 1993;78(3):436‐44. [PUBMED: 8457044] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ochroch 2006 {published data only}

- Ochroch EA, Russell MW, Hanson WC 3rd, Devine GA, Cucchiara AJ, Weiner MG, et al. The impact of continuous pulse oximetry monitoring on intensive care unit admissions from a postsurgical care floor. Anesthesia and Analgesia 2006;102(3):868‐75. [PUBMED: 16492843] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Cullen 1992 {published data only}

- Cullen DJ, Nemeskal AR, Cooper JB, Zaslavsky A, Dwyer MJ. Effect of pulse oximetry, age, and ASA physical status on the frequency of patients admitted unexpectedly to a postoperative intensive care unit and the severity of their anesthesia‐related complications. Anesthesia and Analgesia 1992;74:177‐80. [PUBMED: 1731535] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mateer 1993 {published data only}

- Mateer JR, Olson DW, Stueven HA, Aufderheide TP. Continuous pulse oximetry during emergency endotracheal intubation. Annals of Emergency Medicine 1993;22:675‐9. [PUBMED: 8457094] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Haines 2012 {published data only}

- Haines KL, Downs JB, Mullen MB, Klonsky JA, Gallagher SF. Scheduled, Intermittent oximetry fails to detect postoperative hypoxemia after bariatric surgery. Journal of Surgical Research 2012;172(2):287. [EMBASE: 70651408] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Bendixen 1963

- Bendixen HH, Hedley‐Whyte J, Laver MB. Impaired oxygenation in surgical patients during general anaesthesia with controlled ventilation. New England Journal of Medicine 1963;269:991‐6. [PUBMED: 14059732] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Canet 1991

- Canet J, Ricos M, Vidal F. Postanesthetic hypoxemia and oxygen administration. Anesthesiolgy 1991;74:1161‐2. [PUBMED: 2042775] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Caplan 1990

- Caplan RA, Posner KL, Ward RJ, Cheney FW. Adverse respiratory events in anesthesia: a closed claim analysis. Anesthesiology 1990;72:828‐33. [PUBMED: 2339799] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cooper 1984

- Cooper JB, Newbower RS, Kitz RJ. An analysis of major errors and equipment failures in anesthesia management: considerations for prevention and detection. Anesthesiology 1984;60:34‐42. [PUBMED: 6691595 ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cooper 1987

- Cooper JB, Cullen DJ, Nemeskal R, Hoaglin DC, Gevirtz CC, Csete M, et al. Effects of information feedback and pulse oximetry on incidence of anesthesia complications. Anesthesiology 1987;67:686‐94. [PUBMED: 3674468] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cote 1988

- Cote CJ, Goldstein EA, Cote MA, Hoaglin DC, Ryan JF. A single‐blind study of pulse oximetry in children. Anesthesiology 1988;68:184‐8. [PUBMED: 3277484] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cote 1991

- Cote CJ, Rolf N, Liu LM, Goudsouzian NG, Ryan JF, Zaslavsky A, et al. A single‐blind study of combined pulse oximetry and capnography in children. Anesthesiology 1991;74:980‐7. [PUBMED: 1904206] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guyatt 2008

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck‐Ytter Y, Schunemann HJ. What is "quality of evidence" and why is it important to clinicians?. BMJ. 2008/05/06 2008; Vol. 336, issue 7651:995‐8. [PUBMED: 18456631] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011; Vol. 343. [PUBMED: 22008217] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Krasheninnikoff 1993

- Krasheninnikoff M, Ellitsgaard N, Rude C, Moller JT. Hypoxaemia after osteosynthesis of hip fractures. International Orthopaedics 1993;17(1):27‐9. [PUBMED: 8449619 ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Laver 1964

- Laver MB, Morgan J, Bendixen HH, Radford EP. Lung volume, compliance, and arterial oxygen tensions during controlled ventilation. Journal of Applied Physiology 1964;19:725‐33. [PUBMED: 14195585] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mlinaric 1997

- Mlinaric J, Nincevic N, Kostov D, Gnjatovic D. Pulse oximetry and capnometry in the prevention of perioperative morbidity and mortality. Lijecnicki Vjesnik 1997;119:113‐6. [PUBMED: 9490372] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moller 1998

- Moller JT, Cluitmans P, Rasmussen LS, Houx P, Rasmussen H, Canet J, et al. Long‐term postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the elderly ISPOCD1 study. ISPOCD Investigators. International Study of Post‐Operative Cognitive Dysfunction. Lancet 1998;351:857‐61. [PUBMED: 9525362] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Møller 1994

- Møller JT. Anesthesia related hypoxemia. The effect of pulse oximetry monitoring on perioperative events and postoperative complications. Danish Medical Bulletin 1994;41(5):489‐500. [PUBMED: 7859517 ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nunn 1965

- Nunn JF, Bergman NA, Coleman AJ, Jones DD. Factors influencing the arterial oxygen tension during anaesthesia with artificial ventilation. British Journal of Anaesthesia 1965;37:898‐914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pedersen 1994

- Pedersen T. Complications and death following anaesthesia. A prospective study with special reference to the influence of patient‐, anaesthesia‐, and surgery‐related risk factors. Danish Medical Bulletin 1994;41(3):319‐31. [PUBMED: 7924461] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 5.2 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.2. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012.

Rheineck 1996

- Rheineck‐Leyssius AT, Kalkman CJ, Trouwborst A. Influence of motivation of care providers on the incidence of postoperative hypoxaemia in the recovery room. British Journal of Anaesthesia 1996;77:453‐7. [PUBMED: : 8942327] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Severinghaus 1992

- Severinghaus JW, Kelleher JF. Recent developments in pulse oximetry. Anesthesiology 1992;76:1018‐38. [PUBMED: 1599088] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shah 2013

- Shah A, Shelley KH. Is pulse oximetry an essential tool or just another distraction? The role of the pulse oximeter in modern anesthesia care. Journal of Clinical Monitoring and Computing 2013;27(3):235‐42. [PUBMED: 23314807] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stausholm 1997

- Stausholm K, Rosenberg‐Adamsen S, Edvardsen L, Kehlet H, Rosenberg J. Validation of pulse oximetry for monitoring of hypoxaemic episodes in the late postoperative period. British Journal of Anaesthesia 1997;78:86‐7. [PUBMED: 9059211 ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tinker 1989