Abstract

Background

Hospital environments have recently received renewed interest, with considerable investments into building and renovating healthcare estates. Understanding the effectiveness of environmental interventions is important for resource utilisation and providing quality care.

Objectives

To assess the effect of hospital environments on adult patient health‐related outcomes.

Search methods

We searched: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (last searched January 2006); MEDLINE (1902 to December 2006); EMBASE (January 1980 to February 2006); 14 other databases covering health, psychology, and the built environment; reference lists; and organisation websites. This review is currently being updated (MEDLINE last search October 2010), see Studies awaiting classification.

Selection criteria

Randomised and non‐randomised controlled trials, controlled before‐and‐after studies, and interrupted times series of environmental interventions in adult hospital patients reporting health‐related outcomes.

Data collection and analysis

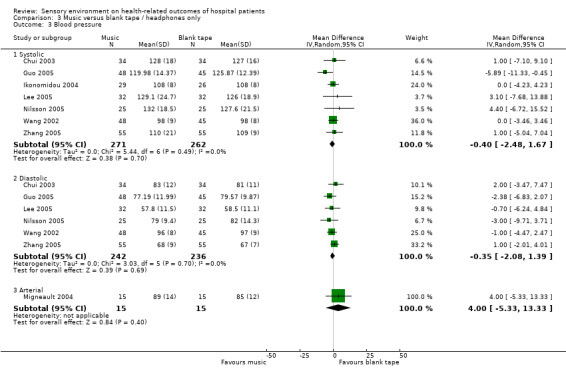

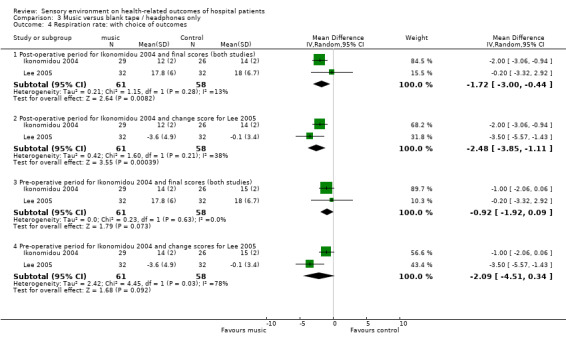

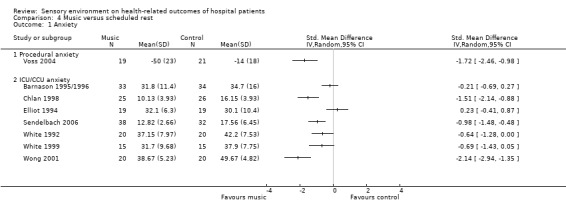

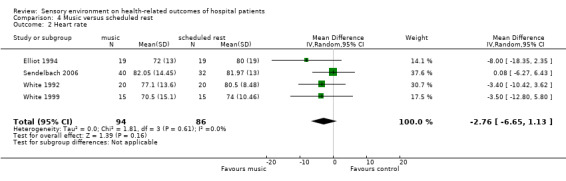

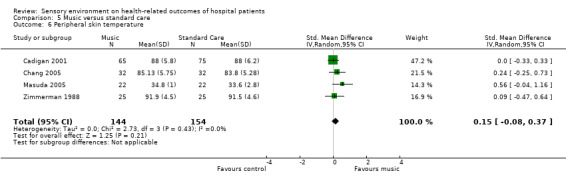

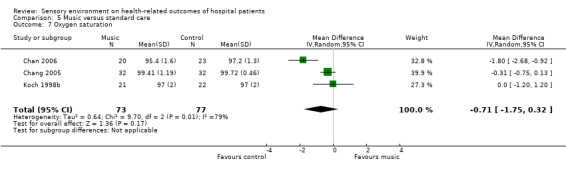

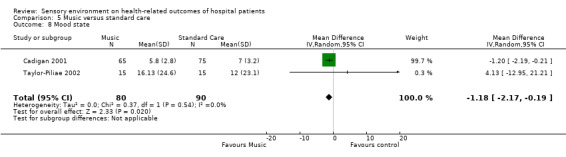

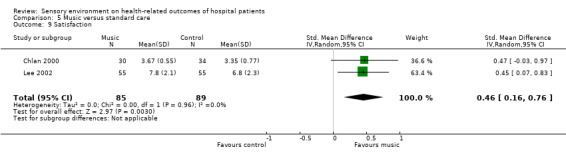

Two review authors independently undertook data extraction and 'Risk of bias' assessment. We contacted authors to obtain missing information. For continuous variables, we calculated a mean difference (MD) or standardized mean difference (SMD), and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each study. For dichotomous variables, we calculated a risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). When appropriate, we used a random‐effects model of meta‐analysis. Heterogeneity was explored qualitatively and quantitatively based on risk of bias, case mix, hospital visit characteristics, and country of study.

Main results

Overall, 102 studies have been included in this review. Interventions explored were: 'positive distracters', to include aromas (two studies), audiovisual distractions (five studies), decoration (one study), and music (85 studies); interventions to reduce environmental stressors through physical changes, to include air quality (three studies), bedroom type (one study), flooring (two studies), furniture and furnishings (one study), lighting (one study), and temperature (one study); and multifaceted interventions (two studies). We did not find any studies meeting the inclusion criteria to evaluate: art, access to nature for example, through hospital gardens, atriums, flowers, and plants, ceilings, interventions to reduce hospital noise, patient controls, technologies, way‐finding aids, or the provision of windows. Overall, it appears that music may improve patient‐reported outcomes such as anxiety; however, the benefit for physiological outcomes, and medication consumption has less support. There are few studies to support or refute the implementation of physical changes, and except for air quality, the included studies demonstrated that physical changes to the hospital environment at least did no harm.

Authors' conclusions

Music may improve patient‐reported outcomes in certain circumstances, so support for this relatively inexpensive intervention may be justified. For some environmental interventions, well designed research studies have yet to take place.

Keywords: Adult; Humans; Health Facility Environment; Interior Design and Furnishings; Outcome and Process Assessment, Health Care; Air Pollution, Indoor; Inpatients; Inpatients/psychology; Lighting; Music; Music/psychology; Odorants; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Temperature

Plain language summary

Sensory environment on health‐related outcomes of hospital patients

The hospital environment (such as sounds, pictures, aromas, design, air quality, furnishings, architecture, and layout), may have an impact on the health of patients within it. This review aims to summarise the best available evidence on hospital environments, in order to help people involved in the design of hospital environments make decisions that will benefit patients' health.

The review identified 102 relevant studies, 85 of which were on the use of music in hospital. Other environmental aspects considered were: aromas (two studies), audiovisual distractions (five studies), decoration (one study), air quality (three studies), bedroom type (one study), flooring (two studies), furniture and furnishings (one study), lighting (one study), temperature (one study), and multiple design changes (two studies). No studies meeting the inclusion criteria were found to evaluate: art, access to nature for example through hospital gardens, atriums, flowers, and plants, ceilings, interventions to reduce hospital noise, patient controls, technologies, way‐finding aids, or the provision of windows.

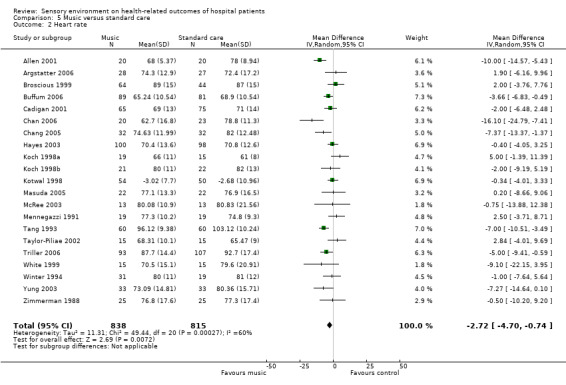

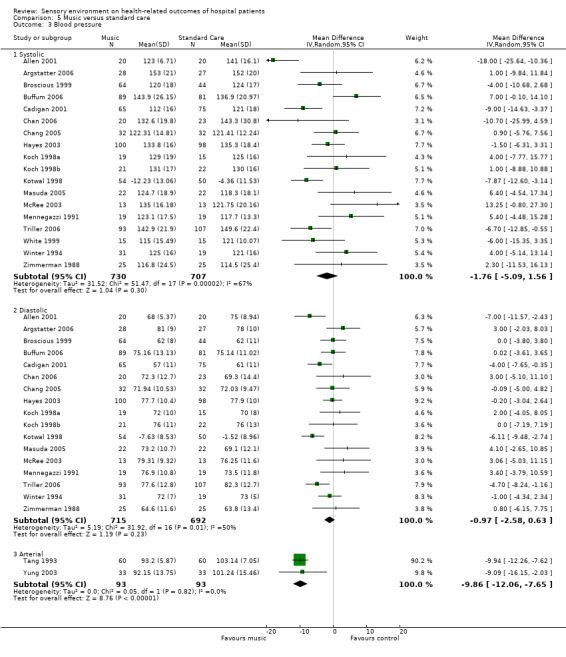

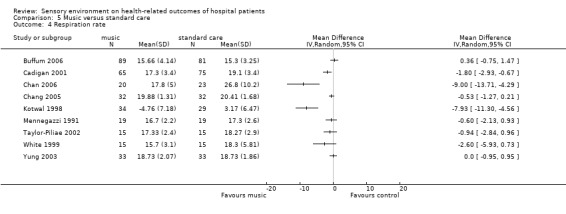

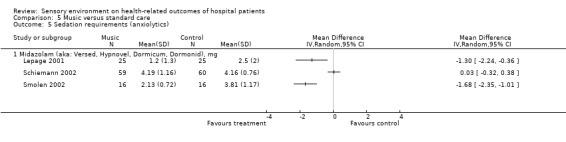

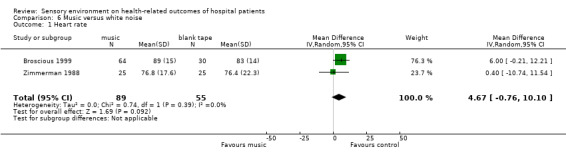

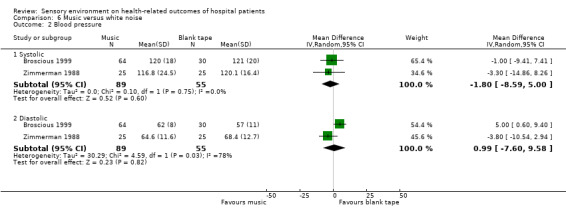

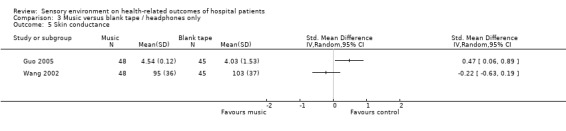

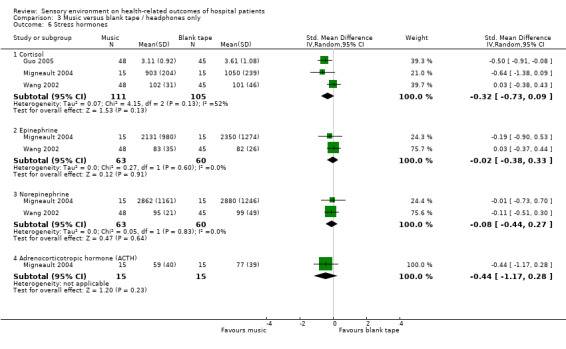

Overall, it appears that music in hospital may help improve patient‐reported outcomes such as anxiety; however, there is less evidence to support the use of music for physiological outcomes (such as reducing heart rate and blood pressure) and for reducing the use of medications. For other aspects of hospital environments, there are not very many well designed studies to help with making evidence‐based design decisions. The studies that have been included in this review show that physical changes made to 'improve' the hospital environment on the whole do no harm.

Background

The International Academy for Design and Health held its 7th World Congress in 2011, highlighting the growing multinational interest in environmental design that promotes health. A reform on a global scale is underway to make hospitals much more than places to go and receive treatment; hospitals are now being conceptualised as places that have the potential to positively impact health through being restorative, healing environments (Dilani 2001). The World Health Organization (WHO) highlights the important role of the environment in the health process, and calls for action towards creating supportive environments ('Ottowa' 2004). In accordance with this movement, international organisations such as The Centre for Health Design (CHD) have been established ('CHD' 2009). CHD's mission is 'to transform healthcare environments for a healthier, safer world through design research, education and advocacy'.

Other initiatives have been stimulated by the US‐based Society for the Arts in Healthcare ('SAH' 2009), which attempts to advance arts as an integral component in health care, and the UK‐based Medical Architecture Research Unit (Etheridge 2008), which provides research, consultancy, and training, with a vision to "explore the interface between health service organisational culture and the built environment response". Research into, and implementation of 'healing' healthcare environments is also being carried out in Japan (Cooper 2002; Takayanagi 2004), and across Europe (Pelikan 2001).

In the Middle East, various major investment projects have been supporting a rapid growth in the hospital sector (News 2004) and the hospital industry in the United States has been going through a major building boom with billions more dollars being spent on replacing or renovating old facilities (Babwin 2002). In the United Kingdom, the Private Finance Initiative (PFI) has prompted a renewed interest in hospital design, investing billions of pounds into the biggest new hospital building programme in the history of the NHS (Milburn 2001). Investments such as these have provided an opportunity for hospitals to be considered as 'therapeutic environments' (Gesler 2004), spurring on initiatives such as the UK‐based scheme in which the Kings Fund and the Department of Health offer grants to health authorities to enhance the environment ('Kings Fund' 2009).

Some argue that this expenditure is a waste of resources (Lipley 2001), whilst others have highlighted the lack of 'evidence‐based practice' when it comes to hospital design (Frumkin 2003). Schemes set up to enhance the hospital environment are sometimes not evaluated on the grounds that it is too logistically complex (Comer 1982), or by simply stating that the effects are obvious (Parker 2000). There is some empirical evidence in support of creating better environments in care facilities however, and researchers are finding that changes to the physical environment can positively influence patient outcomes (Devlin 2003; Rubin 1996). In an invitation‐only conference entitled 'Designing the 21st Century Hospital: serving patients and staff', held by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation ('Webcast' 2004), Craig Zimring and Roger Ulrich referred to a literature review they had conducted, finding over 600 studies on the effects of the hospital environment on patients, families and staff (Ulrich 2004a, later updated: Ulrich 2008). In their presentation of the research, Zimring and Ulrich emphasised the evidence mainly in terms of quantity and consistency of findings. Following the presentations, delegates discussed how worthwhile applying quality criteria to the current evidence would be, such as in a Cochrane systematic review.

Description of the intervention

The environment can be altered in endless ways. Some environmental changes may be detrimental to health (Thompson 2000), further exemplifying the need for using evidence‐based design. As a framework for assessing the evidence on hospital design, the literature could be considered in terms of whether it regards: (1) aspects that are added to the environment as positive distracters (such as art and music); and (2) aspects of the environment that are changed to reduce stressors (such as light, noise or air quality).

In this review, we are interested in elements of the sensory environment; that is, aspects of the hospital surroundings that can be seen, touched, smelt, or heard (such as the building design and layout, decor, furniture and furnishings, air quality and aromas/odours, and noises/sounds). In this review we utilise the phrase 'sensory environment' to define the hospital characteristics under study; in the literature, other terms are utilised such as 'healing environments', 'supportive environments', and 'health‐promoting environments'. We have opted for a less directive phrase as we are interested in determining which environmental factors have positive, negative, and neutral effects on the health of individuals.

How the intervention might work

Sensory environments have been advocated on the basis of their perceived ability to reduce anxiety, lower blood pressure, improve postoperative outcomes, reduce the need for pain medication, and shorten the hospital stay (Ulrich 1992); good design has also been implicated to improve quality of sleep (Hewitt 2002; Marberry 2002), reduce hospital acquired infections (Ulrich 2004b), and improve staff retention and well‐being (Neuberger 2003; Marberry 2002; Gross 1998). Theories underpinning these effects are wide‐ranging and stem from a variety of perspectives, for example: Attention Restorative Theory (a 'functionalist‐evolutionary' model; Kaplan 1989); a 'psycho‐evolutionary' model (Ulrich 1983) and the Biophilia Hypothesis (Ulrich 1993a); Henry's model of neuro‐endocrine responses (Parsons 1991, which incorporates the ideas of the 'Fight or Flight' response to environmental stressors and Selye's model of stress and disease, 'General Adaptation Syndrome'); the Intake‐Reject Hypothesis (Lacey 1974), a controversial hypothesis which has implications for distraction therapies; the 'Gate Control Theory' (Melzack 1965) and the 'Neuromatrix Theory' of pain (Melzack 1999); and the Broaden‐and‐Build model (Fredrickson 2000), which offers a premise for creating environments which help cultivate positive emotions. We will not go into a full explanation and debate of all these theories here, but suffice is to say that although there are some disparities between these explanatory models, and some sit controversially within their fields, they complement each other on the general principles that removing environmental stressors, and using the environment to calm, distract, and elicit positive emotions may have positive implications for health.

Why it is important to do this review

Clearly this is a broad and complex area of study, with the 'environment' being considered as an intervention influencing health‐related outcomes; nevertheless, it is imperative that the evidence‐base for sensory environments is assessed systematically, to ensure that patients are provided with the best possible opportunity to recover and that the system remains cost‐effective.

Objectives

To assess the effect of the sensory hospital environment on adult patient health‐related outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

In this area of research it may often be very difficult to conduct a Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) due to the nature of the intervention and logistical complexities. Therefore, this review included a variety of study designs: RCTs, (non‐randomised) Controlled Clinical Trials (CCTs), Controlled Before and After studies (CBAs), and Interrupted Time Series (ITS). To be included in the review, a CBA had to have two intervention sites and two concurrent control sites with outcomes measured both before and after the intervention was implemented. An ITS had to have at least three data collection points before the intervention, and at least a further three data collection points after the intervention. All studies must have been conducted prospectively.

Types of participants

The review included adults attending hospital as in‐patients, day hospital or out‐patients. Studies were included if over 90% of the participants were over 18. Both elective and non‐elective patients were included in the review. We have included all diagnoses including psychiatric patients (Gross 1998).

Where possible, studies were characterised by the type of hospital visit, where 90% of participants was considered as a cut‐off point for inclusion in a specific category. In‐patients were classed as those that required a hospital bed and required an overnight stay for tests or surgery; day‐patients were patients that required a hospital bed for specialised observation or health care for a limited number of hours of the day, but did not need to stay overnight; out‐patients were people who were referred to see a hospital consultant for a specialist opinion or examination and did not require a hospital bed.

Types of interventions

The review incorporated studies that investigated any aspect(s) of the sensory environment. Interventions were those that altered the environment by one or a mixture of the following ways.

(1) Providing positive distracters to complement the treatment already being administered. Positive distracters are elements of the sensory environment; they do not include therapies (such as bright light therapy), which are received instead of orthodox treatments. Patients could be offered a choice of distraction but we did not include instances when patients were actively involved in creating a distraction (e.g. creating a work of art). Positive distracters included:

aromas/scents (different aromas/patient choice of aroma versus none);

viewing artwork (comparing different styles/patient choice of art versus no art);

viewing performance art (versus none);

audiovisual distractions, such as television/video (absent versus present/differences between content/patient choice of content);

decoration (colour of walls etc.);

music (versus no music, different styles of music, or other environmental comparison);

access to nature, for example via atriums, gardens, window views, or indoor planting (versus no access to nature, other views or urban retreats).

(2) Reducing environmental stressors by implementing physical changes. We have not included changes that are made to policy (e.g. ensuring multi‐bed rooms are unisex). Physical changes to the sensory environment include:

noise‐reducing aids (e.g. sound‐absorbing ceiling tiles versus regular);

way‐finding aids (e.g. colour‐zoned areas, landmarks);

patient controls (e.g. access to lighting and ventilation controls);

lighting (e.g. natural versus fluorescent);

people/privacy (e.g. open versus closed wards, decentralised nurse stations).

(3) Multi‐faceted interventions: Some studies manipulate many variables and as such span across the above three broad categories of environmental interventions (such as when a whole ward is redesigned; Leather 2003). We have included these studies in the review provided they were not confounded with non‐environmental changes, such as changes to policy.

We excluded studies from the review if the intervention was not clearly defined (to the extent that it could be replicated). In order to meet this requirement, studies must have, where applicable, either:

provided the manufacturing details of the intervention being assessed, if appropriate;

provided pictures or diagrams, if appropriate;

provided a detailed description of the objective properties of the intervention, (e.g. an intervention of colour change needs to describe the specific hue; simply stating 'blue' is not specific enough);

provided a contact from which more detailed information could be sought.

All studies were carried out in a hospital setting. A hospital was defined (Ward 2008) as a health facility that:

provides communal care where there is an expectation that this care is time limited;

provides overnight accommodation;

provides nursing and personal care;

provides for people with illness and disability.

This definition includes hospices.

Studies may have been conducted in any area of the hospital grounds, such as general wards, specialist wards (e.g. Intensive Care Units), waiting rooms, common areas, and gardens.

Types of outcome measures

This review included all validated health‐related patient outcomes reported in the research. Outcomes of interest included validated measures of: anxiety; pain; length of hospital stay; patients' satisfaction; quality of sleep; aggression and mood; physiological outcomes; medication utilisation; hospital‐acquired infections; and mortality. We included a broad range of outcomes since the environment may affect many aspects of a patient's physical and psychological health and different interventions may be applicable to some outcomes and not others. When summarising the results of studies, we have reported up to five relevant outcomes for each comparison and grouped the remaining reported outcomes for that intervention under a heading "other outcomes".

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched databases covering the fields of health, medicine, psychology and architecture. To identify possible studies, a strategy for MEDLINE was developed using relevant MeSH terms and text words (dates searched 1902 to December 2006; Appendix 1). This strategy was adapted for other databases searched. These included: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; last searched January 2006; Appendix 2); EMBASE (January 1980 to February 2006; Appendix 3); Royal College of Nursing/British Nursing Index (BNI; January 1985 to August 2005; Appendix 4); PsycINFO (January 1806 to December 2006; Appendix 5); Construction and Building Abstracts (CBA; January 1985 to August 2005; Appendix 6); Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) library online catalogue (last searched December 2005; Appendix 7); InformeDesign (last searched January 2005; Appendix 8); NHS Estates Knowledge and Information Portal (Architecture in Healthcare Database; complete database searched November 2004); Avery Index to Architectural Periodicals (January 1996 to December 2001; Appendix 9); Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; January 1982 to August 2005; Appendix 10); Web of Science (January 1970 to January 2006; Appendix 11); Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA; January 1987 to December 2004; Appendix 12); UK National Research Register (last searched February 2006; Appendix 13); Architecture Publication Index (January 1978 to March 2002; Appendix 14); Turning Research Into Practice (TRIP) database plus (last searched January 2006; Appendix 15); and Zetoc (The British Library's Electronic Table of Contents; last searched January 2006; Appendix 16). This review is currently being updated (MEDLINE last search October 2010; Appendix 17), see Studies awaiting classification.

Searching other resources

We reviewed reference lists of relevant articles, sourced grey literature from relevant organisations' web pages (e.g. Centre for Health Design, NHS Estates and Facilities Division), and contacted researchers for further information and other potential studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

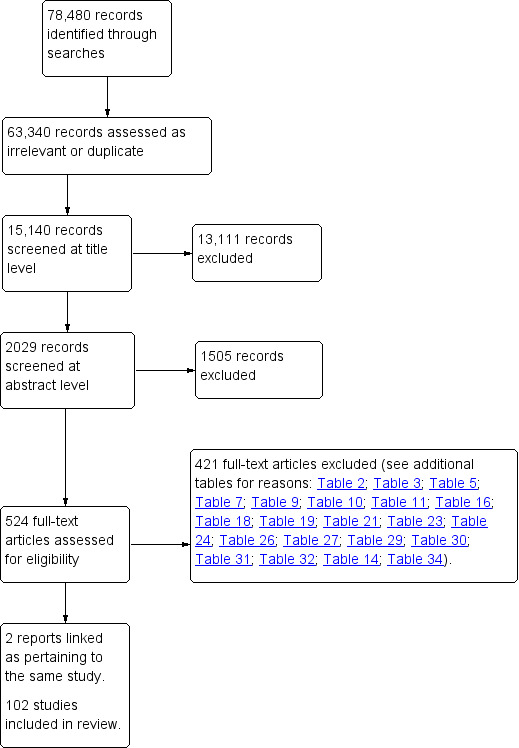

One review author (AD) conducted the initial search (Trials Search Co‐ordinator 'JM' conducted the EMBASE search). The initial search of databases retrieved 78,480 'hits'; these were screened for relevance and the majority of deleted records were double‐checked by a second review author. After screening, 15,140 titles were recorded on the main review database. Two review authors (AD/RS/DW/TD/EG) independently screened the studies obtained from the initial search. Each title was rated as 'hit' (maybe eligible), 'unsure' (probably not eligible) or 'reject' (not to be assessed further). Any disagreement with regard to eligibility was resolved through a third review author and discussion where necessary. We obtained full‐text (English and non‐English) papers for the 'hits' and abstracts for the 'unsures'. All abstracts (2029 total) were assessed independently by two review authors (AD/RS/DW/TD/EG) and rated as 'hit', 'unsure', or 'reject'. We then obtained full‐text papers (524 total) for 'hits' and 'unsures' and these were assessed for inclusion by at least two review authors. We discussed full‐text papers rated as 'unsure' in group meetings. A final corpus of 102 studies was selected for inclusion in the review (see Figure 1 for a flow diagram of the study process).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors undertook data extraction independently, using a modified version of the EPOC data collection checklist (AD/DG/HM/RS/DW/TD/EG). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion between review authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Retrieved studies were independently evaluated for risk of bias by two review authors (AD/DG/HM/RS/DW/TD/EG), using the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). For studies where there was difference of opinion a consensus was reached through discussion between review authors.

Data synthesis

The results section is structured alphabetically by intervention (and control) with multi‐intervention studies (e.g. whole ward redesign) being grouped as a separate category. Where appropriate, we have summarised the results of each intervention against different types of control (e.g. other form of environment, standard care) separately; this is because the effectiveness of interventions will vary depending on the comparison, and it may not be appropriate to combine all different types of control group together. Outcomes for individual interventions are looked at in turn and the heterogeneity of the studies explored.

For continuous variables, we calculated a mean difference (MD) for identical measures, or standardized mean difference (SMD), where different techniques were used to measure the same outcome domain, with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each study. For dichotomous variables, we calculated a risk ratio (RR) with 95% CI. We used sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of risk of bias ('similarities at baseline'; 'sequence generation'; 'concealment of allocation'; 'completeness of data'; and 'blinding of healthcare personnel'), and the influence of deciding to include individual studies that were ambiguous as to whether they met the inclusion criteria.

Where statistical analyses were inappropriate or unfeasible, a discursive account of the results is presented with supporting tables. When it was appropriate to combine the studies, we used a random‐effects model of meta‐analysis. We have presented continuous data that were reported using medians and ranges in tables only.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We identified the presence of statistical heterogeneity by visually examining the forest plots, and using the I2 test for heterogeneity (where it was considered that: 0% to 40% might not be important; 30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100% represents considerable heterogeneity). The importance of the observed value of I2 was evaluated in conjunction with (i) magnitude and direction of effects and (ii) strength of evidence for heterogeneity (i.e. P value from the Chi2 test). We explored heterogeneity qualitatively (based on the characteristics listed below), and with subgroup analyses (where appropriate).

Heterogeneity was explored based on:

case mix (reason for hospitalisation; psychiatric/non‐psychiatric);

hospital visit characteristics (in‐patient/out‐patient/day‐patient; area of hospital studied);

geography (countries in which studies were undertaken).

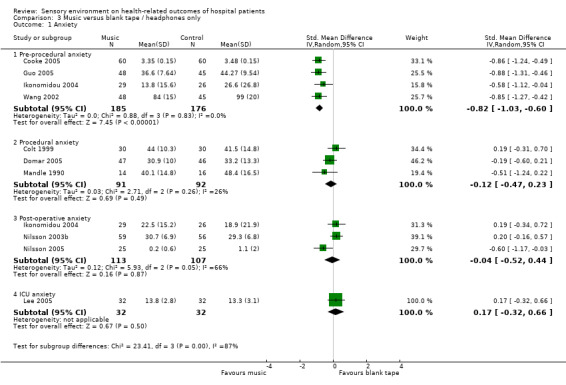

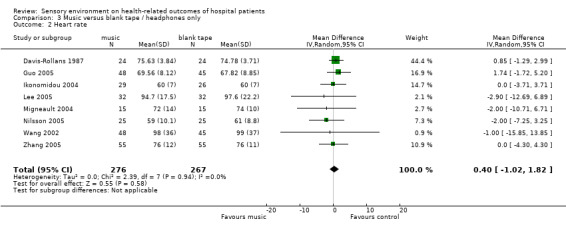

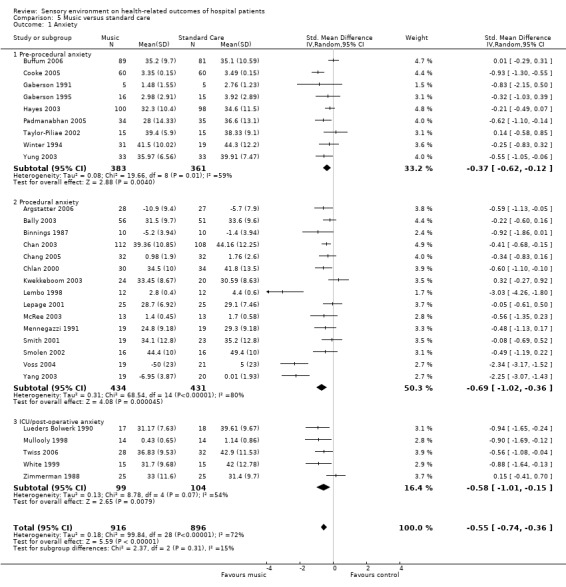

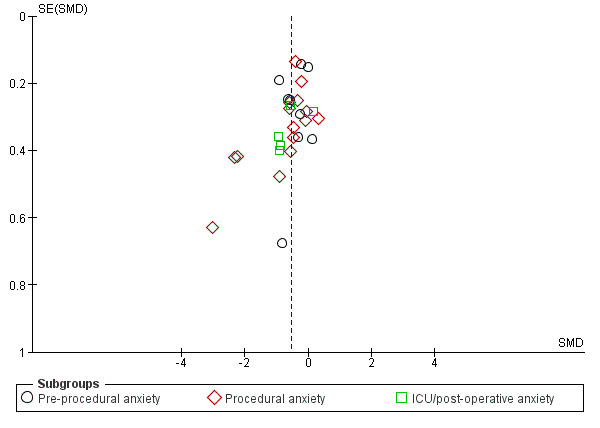

To aid interpretation, we have presented the findings for anxiety from studies on music in subgroups (this decision was made post‐hoc and is based on the following rationale); Given the temporal dependence of anxiety as a transitional state (Spielberger 1983), the studies have been grouped according to the methodological criteria of when the musical intervention was provided, i.e. according to whether music was provided in the waiting period prior to a medical procedure (and hence the outcome of anxiety was obtained after the music intervention but before the medical procedure), or if music was provided throughout a medical procedure (anxiety was measured after both the music and medical procedure), or music was provided in the post‐operative period, or in an intensive care environment. We have displayed Chi2 tests assessing subgroup differences where appropriate (i.e. when the data presented in each subgroup is independent).

Results

Description of studies

Overall, 102 studies have been included in this review; one study was published twice on the same population but with different outcomes reported (Barnason 1995/1996) and two studies (Barnason 1995/1996 ; Lembo 1998) explored more than one type of intervention. Environmental interventions explored were: those that provided positive distracters to complement healthcare treatment already being administered, to include aromas (two studies), audiovisual distractions (five studies), decoration (one study), music (85 studies); those that reduced environmental stressors by implementing physical changes, to include studies on air quality (three studies), bedroom type (one study), flooring (two studies), furniture and furnishings (one study), lighting (one study), and temperature (one study);and multifaceted interventions (two studies). No studies meeting the inclusion criteria were found to evaluate: art, access to nature for example through hospital gardens, atriums, flowers, and plants, ceilings, interventions to reduce hospital noise, patient controls, technologies, way‐finding aids, or the provision of windows.

Studies awaiting assessment

We have two studies published in Korean, which we have not yet been able to assess due to translation difficulties (Hur 2005; Son 2006), one ongoing study (Characteristics of ongoing studies), and a further 66 studies awaiting assessment which are part of an ongoing update of this review (Studies awaiting classification).

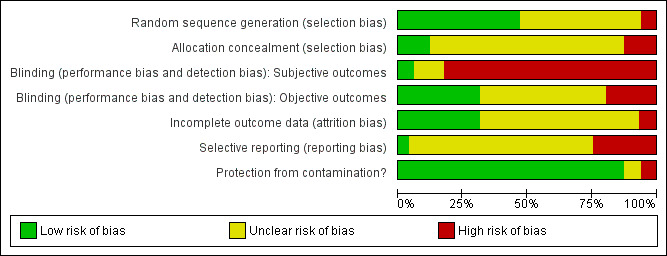

Risk of bias in included studies

A summary of risk of bias judgements for all studies can be seen in Figure 2. A narrative description for each intervention type is given below.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Effects of interventions

Providing positive distracters

Aromas

Description of studies on aromas:

One RCT (Graham 2003) and one CCT (Holmes 2002) have been included on the use of aromas in the hospital (Table 1). These studies investigated the use of aromas in 328 patients overall; in Graham 2003 it is unclear how many participants there are per group, and Holmes 2002 is a cross‐over trial of 15 psychiatric patients. The overall mean age was 65.64 years old, with 169 males and 159 females included in the studies. Studies were conducted in Australia and England. Patient groups assessed were those undergoing radiotherapy treatment, and psychiatric in‐patients in a psychogeriatric ward.

1. Aromas: Characteristics of included studies.

| Study ID | Methods | Participants | Interventions | Outcomes |

| Graham 2003 | RCT; 3 parallel groups. | DESCRIPTION: 313 patients undergoing radiotherapy, in Australia. NUMBERS: Unclear how many patients per group. AGE, mean (range): 65 (33‐90) years old. GENDER (male/female): 163/150. ETHNICITY: not described. INCLUSION CRITERIA: If a course of eight or more fractions of radiotherapy was prescribed. EXCLUSION CRITERIA: not described. | FRAGRANT PLACEBO: Patients were administered the carrier oil with low‐grade essential oils. The carrier oil was sweet almond cold‐pressed pure vegetable oil. The low‐grade fractionated oils (lavender, bergamot, and cedarwood) were of unknown purity (supplied by Naturistics, Hornsby, Australia). These fractionated oils were diluted with the carrier oil in a ratio of 1:2. NON‐FRAGRANT PLACEBO: Patients were administered the carrier oil only: sweet almond cold‐pressed pure vegetable oil. PURE ESSENTIAL OIL: 100% pure essential oils of lavender, bergamot, and cedarwood were administered in a ratio of 2:1:1 (supplied by "In Essence"). All patients were administered their study treatment via a necklace with a plastic‐backed paper bib, donned before radiotherapy treatment each day and removed after exiting the treatment bunker. Three drops of oil were applied to the bib. Typical duration lasted 15‐20 minutes. Patients were seated in waiting areas segregated according to study arm allocation to avoid cross‐exposure. | ANXIETY, DEPRESSION, and FATIGUE: Measured via the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and the Somatic and Psychological Health Report (SPHERE), which is composed of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) and Symptoms of Fatigue and Anergia (SOFA) scales. In a multivariate analysis: There were significantly fewer patients with anxiety >7 in the non‐fragrant placebo arm than both the essential oil (Odds ratio = 2.6, 95% CI = 1.1 to 6.1), and fragrant placebo (Odds ratio = 2.8, 95% CI = 1.1 to 6.7) groups. There were no significant differences between groups in depression scores, the General Health Questionnaire, and fatigue scale. |

| Holmes 2002 | CCT; Cross‐over trial, 2 conditions. | DESCRIPTION: 15 psychiatric inpatients in the communal area of a long‐stay hospital psychogeriatric ward for patients with behavioural problems, in England. NUMBERS: 15 patients; cross‐over trial. AGE, mean (SD): 79.0 (6.3) years old. GENDER (male/female): 6/9. ETHNICITY: not described. INCLUSION CRITERIA: International classification of disease (ICD)‐10 diagnostic criteria for severe dementia; evidence of agitated behaviour‐ defined as scoring > 3 on the Pittsburgh Agitation Scale at some point each day over the period of a week. EXCLUSION CRITERIA: none described. | LAVENDER: The communal area of the unit was diffused with a standard concentration of lavender oil (2%), using three aroma‐streams for a period of two hours between the period of 4pm and 6pm. PLACEBO: The communal area of the unit was diffused with water, using three aroma‐streams for a period of two hours between the period of 4pm and 6pm. A total of five treatments and five placebo trials were carried out for each patient over a period of two weeks. | AGITATION: Measured on the 16‐point Pittsburgh Agitation Scale by a blinded observer for the final hour of each two hour study period. Outcomes are presented as median scores for each patient in each condition. 9 patients showed an improvement with lavender. 5 patients showed no change with lavender. 1 patient showed a worsening of condition with lavender. Wilcoxon Signed‐Ranks test, P = 0.016 Of the 4 patients with Alzheimer's disease, 3 improved and 1 showed no change; of the 7 patients with vascular dementia, 5 improved and 2 showed no change; of the 3 patients with Dementia with Lewy Bodies, 2 showed no change and 1 worsened; the 1 patient with Fronto‐temporal lobe dementia improved. |

SD: standard deviation

Fragrances were administered via a necklace with a plastic‐backed paper bib (Graham 2003) and an aroma‐stream in the communal area (Holmes 2002). One study had three comparison groups (Graham 2003). Fragrances evaluated were: low‐grade fractionated oils (combination of lavender, bergamot, and cedarwood, diluted with a carrier oil), 100% pure essential oil (combination of lavender, bergamot, and cedarwood), and lavender oil (2%). Control conditions were: sweet almond cold‐pressed pure vegetable oil only; and water.

Outcomes assessed were: anxiety, depression, fatigue, and agitation.

We have tabulated 15 excluded studies (Table 2).

2. Aromas: Characteristics of excluded studies.

| Study ID | Reason for exclusion |

| Anderson 2004 | Intervention |

| Burns 2000a | Study design |

| Burns 2000b | Study design |

| Burns 2002 | Study design |

| Bykov 2003a | Setting and population |

| Girard 2004 | Editorial |

| Hudson 1995 | Study design |

| Hudson 1996 | Outcomes |

| Itai 2000 | Study design |

| Kane 2004 | Data unsuitable for cross‐over study |

| Kirkpatrick 1998 | Commentary |

| Lehrner 2000 | Setting |

| Louis 2002 | Setting |

| Redd 1994 | Aromas administered via nasal cannula, judged to be too invasive to constitute an 'environmental' intervention. |

| Tate 1997 | Intervention; outcome not validated |

Risk of bias in included studies on aromas:

One RCT and one CCT were included on hospital aromas. Methods of group assignment were via telephone contact to a data management centre (Graham 2003; adequacy unclear), and alternate days (Holmes 2002). Concealment of allocation is adequate in Graham 2003. Blinding (of patients, physicians, and outcome assessment) was attempted in Graham 2003. In this study 9% of patients in the non‐fragrant placebo group believed they had received pure essential oil, 25% in the fragrant placebo group believed they had received pure essential oil, and 24% in the pure essential oil group believed they had received the pure essential oil. Holmes 2002 blinded the outcome assessor to study group (through the use of nose callipers), although in this study it was not feasible to blind patients to the scent on the ward. Completeness of outcome data was satisfactory in the studies (> 80% complete). Graham 2003 did not report withdrawals and drop‐outs, and in Holmes 2002 there were no withdrawals. It is unclear whether or not there is selective outcome reporting in either study. Protection against contamination could not be achieved in Holmes 2002 as this was a cross‐over trial, however, for the other study, this was not a problem.

Findings from studies on aromas:

Anxiety

One study on patients undergoing radiotherapy treatment, measured the outcome anxiety on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale (Graham 2003). Graham 2003 reports a multivariate analysis, in which there were significantly fewer anxious patients (cases were classified as anxious when scoring > 7) in the non‐fragrant placebo group (13%), than in both the essential oil group (25%), odds ratio (OR) = 2.6 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.1 to 6.1), and fragrant placebo group (23%), OR = 2.8 (95% CI 1.1 to 6.7).

Other outcomes

Graham 2003 found no strong evidence of effects for depression, fatigue, and general health (data insufficient for extraction) between any of the three groups.

Findings from non‐randomised studies:

Holmes 2002 investigated agitation using the Pittsburgh Agitation Scale (PAS) in a psychogeriatric ward communal area (N = 15, cross‐over study) and reports a significant effect (Wilcoxon Signed‐Ranks test P value 0.016) in favour of the lavender oil aroma‐stream group (median PAS score = 3, range = 1 to 7) versus diffused water (median PAS score = 4, range 3 to 7).

Art

Description of studies on art:

No studies have been included on the use of art in hospital. We have tabulated 16 excluded studies (Table 3).

3. Art: Characteristics of excluded studies.

| Study ID | Reason for exclusion |

| Bower 1995 | Qualitative report |

| Breslow 1993 | Descriptive article |

| De Jong 1972 | Participants |

| Finkelstein 1971 | Intervention interactive |

| Finlay 1993 | Qualitative report |

| Green 1994 | News article |

| Guillemin 2000 | Qualitative |

| Homicki 2004 | Descriptive article |

| Litch 2006 | Narrative article |

| Mellor 2001 | Commentary |

| Palmer 1999 | No group comparisons presented, unable to obtain further details from authors |

| Staricoff 2001 | Study design |

| Staricoff 2003a | Study design (part of same study as Staricoff 2001) |

| Ulrich 1993b | Conference abstract, unable to obtain further details from author |

| Wikström 1992 | Setting |

| Wikström 1993 | Setting |

Audiovisual distractions

Description of studies on audiovisual distractions:

Five RCTs were conducted on audiovisual distractions (Table 4; NB. two articles report on Barnason 1995/1996; although the articles report differently on the choices of audiovisual distractions made available to the intervention group, the patient demographics and study designs are identical). These studies result in a total sample of 387 participants (Audiovisual group = 144, Control group = 243). Included patients had a mean age of 53.92 years old (range = 18 to 90), with 231 males and 156 females. Four studies were conducted in the USA and one was conducted in China. Three studies were carried out during endoscopy interventions, one was conducted during dressing changes for burns, and one during the post‐operative period.

4. Audiovisual: Characteristics of included studies.

| Study ID | Methods | Participants | Interventions | Outcomes | Notes |

| Barnason 1995/1996 | RCT; 3 parallel groups. | DESCRIPTION: 96 in‐patients in the cardiovascular ICU and progressive care units having undergone elective coronary artery bypass grafting, in USA. NUMBERS: Music group = 33, Music + video group = 29, Scheduled rest group = 34. AGE, mean (SD): 67 (9.9) years old. GENDER (male/female): 65/31. ETHNICITY: White = 96 (100%) INCLUSION CRITERIA: Orientated to person, time and place; speak and read English; 19 years or older; extubated within 12 hours of surgery; removal of intra‐aortic balloon pump within 12 hours of surgery. EXCLUSION CRITERIA: Currently using one of the intervention techniques; major hearing deficit. | MUSIC GROUP: Choice of 5 tapes: 'Country Western Instrumental' or 'Fresh Aire' by Mannheim Steamroller, 'Winter into Spring' by George Winston, or 'Prelude' or 'Comfort Zone' by Steven Halpern. Played via headphones for 30 minutes. MUSIC + VIDEO GROUP: Barnason 1995 states: Choice of 2 Steven Halpern tapes: 'Summer Wind' or 'Crystal Suite'. Each is 30 minutes of soft instrumental with visual imaging. Zimmerman 1996 states: Choice of three 30 minute videocassettes by Pioneer Artist ('Water's Path', 'Western Light', or 'Winter'). SCHEDULED REST: 30 minutes of rest in bed or chair, visitors and staff requested not to disturb. 2 x 30 min intervention periods during afternoons of post‐operative days 2 and 3. Lights dimmed. | Barnason 1995 reports: STATE ANXIETY: measured using STAI at three time‐points: pre‐operatively, before intervention on 2nd post‐operative day, and after intervention on 3rd post‐operative day. ANXIETY: taken using NRS before and after each intervention session. PHYSIOLOGICAL: HR (bpm) and BP (mm Hg) taken using the Kendall BP Monitor (Model 8200)‐ not enough data presented for extraction. MOOD: Measured using a NRS‐ not a validated outcome. Zimmerman 1996 reports: PAIN: Pain was measured with a 10‐point VRS before and after each session, and with the McGill Pain Questionnaire (scores are given for the subscales and the present pain index rating scale) administered once prior to the first session, and once after the second session. SLEEP: Measured with the Richards‐Campbell Sleep Questionnaire (RSQ), administered between 7am and 9am on the third post‐operative day. | Data extracted for state anxiety (STAI measure). Pain data are extracted for the end values on the VRS. Patients in the music group showed a significant improvement in mood after the 2nd intervention when controlling for pre‐intervention mood rating. No differences between groups were found for anxiety on either data collection tool. Physiological measures did not differ between groups, however there were significant differences over time (regardless of group), indicating a generalised relaxation response. Authors conclude that although no intervention was overwhelmingly superior, all groups demonstrated a relaxation response. |

| Diette 2003 | RCT; 2 parallel groups. | DESCRIPTION: 80 in‐patients and out‐patients undergoing FB in Mariland, USA. NUMBERS: Bedscapes group = 41, Control = 39 patients. AGE, mean (range): Bedscapes = 52.3 (21‐88); Control = 55.3 (30‐90). GENDER (Male/Female): Bedscapes = 16/25; Control = 22/17. ETHNICITY (White/African‐American): Bedscapes = 25/16; Control = 28/11. INCLUSION CRITERIA: 18 years or older, undergoing FB. EXCLUSION CRITERIA: Non‐English speaker, contact isolation, presence of encephalopathy or significant alteration in mental status, sensory deficits that preclude use of visual/auditory aid. | BEDSCAPES GROUP: Countryside river scene with associated sounds of nature played through headphones. Intervention available before, during, and after FB procedure. The scene was mounted by the bedside in the recovery area and on the ceiling in the procedure room. CONTROL GROUP: standard care. | ANXIETY: State anxiety via STAI; PAIN: Pain control during procedure measured by VRS. Values presented as % with good/excellent pain control. Due to unclear missing data (> 10%), it is unclear how many people this represents. ABILITY TO BREATHE: (poor to excellent) rating scale. Validity unclear. SATISFACTION WITH CARE: Ratings of: willingness to return, privacy, safety, overall rating of facility. Validity unclear. Outcomes obtained via a follow‐up survey administered on the second day following the procedure. Out‐patients completed form and returned it by mail. In‐patients forms were collected from their hospital room. | SDs for anxiety have been estimated from P value of a t‐test. Adverse events: 1 patient in the treatment group urinated on the bronchoscopy table. The patient felt that this had occurred because of hearing sounds of running water. |

| Lee 2004a | RCT; 3 parallel groups. | DESCRIPTION: 157 day‐patients undergoing colonoscopy in an Endoscopy Suite in Hong Kong, China. NUMBERS: Visual distraction = 52 patients, Audiovisual distraction = 52 patients, Control group = 53 patients. AGE, mean (SD): Visual distraction = 45.6 (10.2), Audiovisual distraction = 48.8 (11.3), Control group = 46.3 (11.4). GENDER (male/female): Visual distraction = 25/27, Audiovisual = 27/25, Control group = 23/30. ETHNICITY: not described. INCLUSION CRITERIA: Undergoing elective day‐case colonoscopy. EXCLUSION CRITERIA: History of allergy to propofol and/or alfentanil. Receive a colectomy. | VISUAL DISTRACTION: Eyetreck system (olympus) with preset home made movie (mainly scenic views), patient wears earphones but with no sound. AUDIOVISUAL DISTRACTION: Same as visual distraction with the addition of classical music played through earphones. CONTROL: Standard care. All groups received PCS using a mixture of propofol and alfentanil. | PAIN: scored using 10 cm VAS; SATISFACTION: measured using 10 cm VAS; Willingness to repeat procedure (using 10 cm VAS); ANALGESICS: Dose of PCS consumed; PHYSIOLOGICAL: Hypotensive episodes; Oxygen desaturation; RECOVERY TIME: nurse assessed | |

| Lembo 1998 | RCT; 3 parallel groups. | DESCRIPTION: 37 patients undergoing flexible sigmoidoscopy in Calfornia, USA. NUMBERS: Audiovisual group = 13, audio alone group = 12, control group = 12. AGE, mean (SD): Audiovisual group = 58 (7), Audio alone group = 60 (8), Control group = 59 (7) years old. GENDER: Male = 37 (100%). ETHNICITY: not described. INCLUSION CRITERIA: Undergoing routine screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. EXCLUSION CRITERIA: none described. | AUDIOVISUAL: Virtual‐i glasses, personal display system showing an ocean shoreline with corresponding sounds (via headphones) AUDIO ALONE: Sounds of the ocean shoreline only played via headphones. CONTROL: No intervention, standard care. | DISCOMFORT: Measured via VAS which asked patients to rate their level of abdominal discomfort from faint to severly intense. STRESS SYMPTOMS: Measured 6 subscales (arousal, stress, anxiety, anger, fatigue, and attention) using 12 VAS. | Data for discomfort entered as pain scores. Data extracted for review on anxiety and anger. Arousal and attention not considered health‐related outcomes. There was no difference between groups on the stress and fatigue subscales, data not reported for extraction. |

| Miller 1992 | RCT; 2 parallel groups. | DESCRIPTION: 17 in‐patients undergoing burns care treatment and dressings change in a Burn Special Care Unit, Cincinnati, USA. NUMBERS: Audiovisual group = 9, Control group = 8. AGE, mean: Audiovisual group = 40.9, Control group = 27.8 GENDER (male/female): Audiovisual group = 9/0, Control group = 7/1. ETHNICITY (white/black): Audiovisual group = 8/1, Control group = 7/1. INCLUSION CRITERIA: 10‐40% body surface burn; expected length of stay >/= 1 week; Adult patients, 18 years or older. EXCLUSION CRITERIA: Substance abuse disorder; unable to see/or hear; psychotic; under 18 years old; cannot understand English; mentally retarded; disorientated; multiple trauma injuries. | AUDIOVISUAL GROUP: "Muralvision" (Muralvision Studios, Inc., Eugene, Ore.)‐ on a bedside television, video programmes composed of scenic beauty (ocean, desert, forest, flowers, waterfalls, and wildlife) with accompanying music. CONTROL GROUP: Standard care. Participants were exposed to their treatment group on 10 occasions during dressing change. | PAIN: Measured via the McGill Pain Questionnaire, with the Pain Rating Index and Present Pain Intensity scales. ANXIETY: Measured via the STAI. Outcomes were measured within 2 minutes at the end of each dressing change. Outcomes are reported as the overall means and standard errors for the 10 dressing changes. | For data extraction in the review, change scores from baseline were calculated and associated estimated standard deviations, using the F statistics provided. |

SD: standard deviation; STAI: State Trait Anxiety Inventory; VAS: visual analogue scale

Audiovisual interventions were all nature‐based, with Diette 2003 consisting of a static "photomural" of nature and the remaining being video‐based (Lee 2004a and Lembo 1998 used video eye glasses, and Barnason 1995/1996 and Miller 1992 used a bedside television). Diette 2003 and Lembo 1998 played nature sounds which corresponded to the visual distraction, and Barnason 1995/1996, Lee 2004a, and Miller 1992 played accompanying music. Three studies had more than one control group. Control groups consisted of: standard care alone (N = 4; Diette 2003; Lee 2004a; Lembo 1998; Miller 1992), visual distraction alone (N = 1; Lee 2004a), audio distraction alone (N = 2; Barnason 1995/1996; Lembo 1998), and scheduled rest (N = 1; Barnason 1995/1996).

Outcomes investigated were: Anxiety (N = 4), patient‐reported pain (N = 5), heart rate (N = 1), blood pressure (N = 1), sedation medication requirement (N = 1), sleep (N = 1), satisfaction (N = 1), hypotensive episodes (N = 1), oxygen desaturation (N = 1), recovery time (N =1), anger (N =1), stress (N = 1), and fatigue (N = 1).

We have tabulated 16 excluded studies on audiovisual distractions (Table 5).

5. Audiovisual: Characteristics of excluded studies.

| Study ID | Reason for exclusion |

| Allen 1989 | Intervention |

| Egger 1981 | Study design |

| Friedman 1992 | Study design |

| Hoffman 2000 | Intervention‐ interactive virtual reality |

| Hoffman 2001 | Intervention‐ interactive virtual reality |

| Holden 1992 | Intervention‐ patient education video |

| Martin 1999 | Inadequate information provided (Ulrich study) |

| Oyama 2000 | Intervention interactive |

| Pruyn 1998 | Unclear validity of outcomes |

| Schneider 2003 | Intervention interactive |

| Schneider 2004 | Intervention interactive |

| Schofield 2000 | Intervention‐ snoezelen |

| Singer 2000 | Population, < 90% over 18 years old. |

| Tse 2003 | Setting |

| Ulrich 2003 | Setting |

| Wint 2002 | Participants not adults |

Below, we summarise findings for the following comparisons:

Audiovisual distraction versus audio distraction (music)

Audiovisual distraction versus scheduled rest

Audiovisual distraction versus standard care alone

Audiovisual distraction versus visual distraction

Visual distraction versus standard care alone

Risk of bias in included studies on audiovisual distractions:

Five RCTs were included on audiovisual distractions. For Lembo 1998 and Miller 1992, the method of randomisation is unclear; Lee 2004a allocated patients via a computer‐generated list; Barnason 1995/1996 drew lots; and Diette 2003 allocated patients according to clinic day (which was randomised to intervention and control). Of the five included studies, it is unclear if concealment of allocation was used in four studies, and it was not used in one (Barnason 1995/1996 ). Lee 2004a reports blinding of recovery nurses (who assessed some outcomes) to patient allocation, and blinding of the endoscopists to two patient groups (but not to the standard care group). In the remaining studies blinding of healthcare personnel was not possible. Only Lee 2004a was judged to address incomplete outcome data, and the others remain unclear. Lee 2004a reported withdrawals and drop‐outs (eight patients; unclear from which groups), the reasons for which appear unrelated to the interventions, and Barnason 1995/1996 reports that all participants completed the study. Barnason 1995/1996 and Diette 2003 have been judged to be at risk of selective outcome reporting, whilst the remaining studies are unclear. All studies offered protection against contamination.

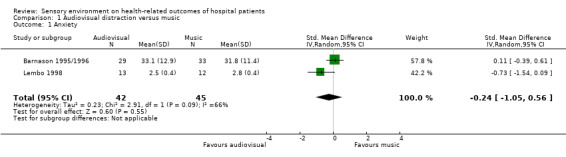

Findings from studies on audiovisual distraction versus audio distraction (music):

Anxiety

Two studies (Barnason 1995/1996; Lembo 1998) reported on the outcome anxiety (audiovisual group = 42, audio group = 45). Although both studies showed no strong evidence that the intervention had an effect (both individually and when combined: standardised mean difference (SMD) −0.24, 95% CI −1.05 to 0.56, P Value = 0.55), when combined they demonstrate moderate statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 65.6%, Chi2 = 2.91, df = 1, P value = 0.09; Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Audiovisual distraction versus music, Outcome 1 Anxiety.

Exploring the heterogeneity of studies on anxiety:

With only two studies, it is difficult to explore the reasons for heterogeneity in terms of methodological and clinical differences. Both studies are subject to risk of bias; neither study had adequate allocation concealment and in Barnason 1995/1996 allocation concealment was not used. Additionally, Lembo 1998 was a very small study with no power calculation. Both studies were conducted in the USA and used video visual images. Barnason 1995/1996 was conducted on post‐operative patients and Lembo 1998 was conducted on patients undergoing an endoscopic procedure.

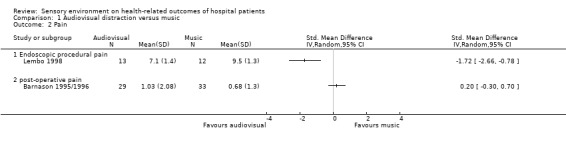

Pain

Two studies (Barnason 1995/1996; Lembo 1998) reported on the outcome pain (audiovisual group = 42, audio group = 45). With one small study (N = 25) in favour of audiovisual distraction (Lembo 1998: SMD −1.72, 95% CI −2.66 to −0.78), and the other (N = 62) showing no strong evidence that the intervention had an effect (Barnason 1995/1996: SMD 0.20, 95% CI −0.30 to 0.70), the studies combine with considerable statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 92%; Analysis 1.2), so we have not pooled these studies in a meta‐analysis.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Audiovisual distraction versus music, Outcome 2 Pain.

Exploring the heterogeneity of studies on pain:

The comparison of Barnason 1995/1996 with Lembo 1998 has already been assessed for the outcome anxiety above.

Heart rate

Studies with insufficient data for extraction:

One study (Barnason 1995/1996; audiovisual N = 29, music N = 33) collected data on heart rate and reported that there was no strong evidence that the intervention had an effect.

Blood pressure

Studies with insufficient data for extraction:

One study (Barnason 1995/1996; audiovisual N = 29, music N = 33) collected data on blood pressure and reported that there was no strong evidence that the intervention had an effect.

Other outcomes

Lembo 1998 additionally reported on anger and fatigue (data insufficient for extraction). This study (audiovisual group = 13, audio group = 12) found the audiovisual group to have significantly lower anger scores (mean difference (MD) −0.40 points on a 10‐point visual analogue scale (VAS), 95% CI −0.68 to −0.12, P value = 0.005) and no difference in fatigue ratings. Barnason 1995/1996 (audiovisual = 29, music = 33) collected data on sleep quality to find no strong evidence that the intervention had an effect (MD 0.40 on the Richards‐Campbell Sleep Questionnaire, 95% CI −0.71 to 1.51, P value = 0.48).

Findings from studies on audiovisual distraction versus scheduled rest:

Anxiety

One study (Barnason 1995/1996) reported on anxiety (audiovisual group N = 29, scheduled rest N = 34) and found no strong evidence for an intervention effect (MD −1.60 points on the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), 95% CI −8.74 to 5.54, P value = 0.66).

Pain

One study (Barnason 1995/1996) reported on pain (audiovisual group N = 29, scheduled rest group N = 34) and found no strong evidence for an intervention effect (MD 0.15 points on a 10 point verbal rating scale (VRS), 95% CI −0.82 to 1.12, P value = 0.76).

Heart rate

Studies with insufficient data for extraction:

One study (Barnason 1995/1996; audiovisual N = 29, scheduled rest N = 34) collected data on heart rate and found no strong evidence for an intervention effect.

Blood pressure

Studies with insufficient data for extraction:

One study (Barnason 1995/1996; audiovisual N = 29, scheduled rest N = 34) collected data on blood pressure and found no strong evidence for an intervention effect.

Other outcomes

One study (Barnason 1995/1996 reported on sleep quality (audiovisual group N = 29, scheduled rest group N = 34) and found scores to significantly favour the audiovisual group (MD 1.57 on the Richards‐Campbell Sleep Questionnaire, 95% CI 0.47 to 2.67, P value = 0.005).

Findings from studies on audiovisual distraction versus standard care alone:

Anxiety

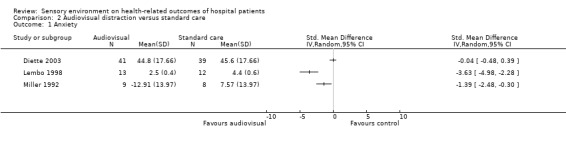

Three studies reported on anxiety (audiovisual group = 63, standard care group = 59). The largest of these studies (Diette 2003; N = 80) showed no strong evidence that the intervention had an effect, whilst the smaller two studies (Lembo 1998; Miller 1992) have significant findings favouring audiovisual distraction. When combined these studies show considerable statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 93%; Analysis 2.1) so we have not pooled these studies in a meta‐analysis.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Audiovisual distraction versus standard care, Outcome 1 Anxiety.

Exploring the heterogeneity of studies on anxiety:

With few studies it is difficult to explore reasons for heterogeneity. All three studies are subject to risk of bias with unclear allocation concealment. Other than the size and quality of the individual studies, a further explanation for the differences in findings could be that the intervention Diette 2003 utilised was a static picture, whereas the other studies utilised video. All studies were conducted in the USA, with two (Diette 2003; Lembo 1998) being conducted on endoscopy patients and the other being conducted on patients undergoing burns dressing changes.

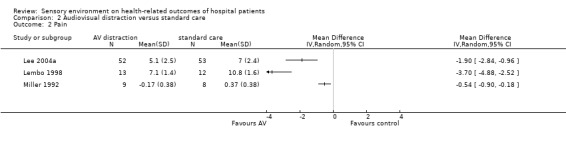

Pain

Three studies (Lee 2004a; Lembo 1998; Miller 1992) reported sufficient information for extraction on pain (Analysis 2.2). Although all three studies were significantly in favour of audiovisual distraction for pain relief, there is considerable heterogeneity between study effect estimates (I2 = 93%), therefore we have not pooled these studies in a meta‐analysis.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Audiovisual distraction versus standard care, Outcome 2 Pain.

Exploring the heterogeneity of studies on pain:

With few studies it is difficult to explore reasons for heterogeneity. All three studies are subject to risk of bias, with unclear allocation concealment. All three studies used a video audiovisual distraction. Two were conducted in patients undergoing an endoscopic procedure and one (Miller 1992) was conducted during burns dressing changes. Two were conducted in the USA and one (Lee 2004a) was conducted in China.

Studies with insufficient data for extraction:

Diette 2003 also reported on pain scores; this study, which used static pictures also found a significant effect for pain in favour of patients who received an audiovisual distraction.

Sedation medication requirements

Lee 2004a reported on propofol requirement in patients undergoing an endoscopy procedure in China. This study found that those who received an audiovisual distraction (N = 52) required significantly less sedation medication than those who received standard care (N = 53), MD −0.37 mg/kg (95% CI −0.58 to −0.16, P value = 0.0005).

Other outcomes

Other health‐related outcomes reported were recovery time (Lee 2004a), oxygen desaturation episodes (Lee 2004a), hypotensive episodes (Lee 2004a), satisfaction (Lee 2004a), anger (Lembo 1998), and fatigue (Lembo 1998). Outcomes (each from just one study) favouring audiovisual distraction were anger (MD −2.20 cm on a 10 cm VAS, 95% CI −2.63 to −1.77, P value < 0.00001) and satisfaction (MD 2.30 cm on a 10 cm VAS, 95% CI 1.28 to 3.32, P value < 0.00001). There is no strong evidence of an intervention effect for recovery time, oxygen desaturation episodes, hypotensive episodes, or fatigue.

Findings from studies on audiovisual distraction versus visual distraction:

Pain

Lee 2004a found that audiovisual distraction (N = 52) is significantly better than visual distraction alone (N = 52) at reducing patient‐reported pain (MD −1.10 cm on a 10 cm VAS, 95% CI −2.01 to −0.19, P value = 0.02).

Sedation medication requirements

Lee 2004a found that audiovisual distraction (N = 52) is significantly better than visual distraction alone (N = 52) at reducing sedation medication requirements (MD −0.36 mg/kg, 95% CI −0.62 to −0.10, P value = 0.006).

Other outcomes

Lee 2004a also reported on recovery time, satisfaction, episodes of oxygen desaturation, and episodes of hypertension. For these outcomes there is no strong evidence that audiovisual distraction was more effective than visual distraction alone.

Findings from studies on visual distraction versus standard care alone:

Pain

Lee 2004a found no significant difference for patient‐reported pain (MD −0.80 cm on a 10 cm VAS, 95% CI −1.68 to 0.08, P value = 0.07) between a visual distraction group (N = 52) and standard care (N = 53).

Sedation medication requirements

Lee 2004a found no significant difference for sedation medication (propofol) requirements (MD −0.01 mg/kg, 95% CI −0.28 to 0.26, P value = 0.94) between a visual distraction group (N = 52) and standard care (N = 53).

Other outcomes

Lee 2004a found that patients allocated to a visual distraction group (N = 52) were significantly more satisfied (MD 2.10 cm on a 10 cm VAS, 95% CI 1.08 to 3.12, P value < 0.0001) than those allocated to standard care (N = 53).

Decoration

Description of studies on decoration:

One RCT on hospital décor has been included in the review (Table 6; Edge 2003). In this study there were 39 participants overall; 13 patients were assigned to beige rooms, 10 to purple, nine to green, and seven to orange. In Edge 2003 participants' ages ranged from 26 to 89 years old (average unknown), with 20 males and 19 females. The study was conducted in the USA on patients in a cardiac care unit.

6. Decoration: Characteristics of included studies.

| Study ID | Methods | Participants | Interventions | Outcomes | Notes |

| Edge 2003 | RCT; 4 parallel groups. | DESCRIPTION: 39 in‐patients (10 post‐operative for cardiac surgery, 29 undergoing cardiac observations) in a cardiac care unit in Florida, USA. NUMBERS: Beige = 13, Purple = 10, Green = 9, Orange = 7. AGE: 26 to 89 years old. GENDER (male/female): 20/19. ETHNICITY: not described. INCLUSION CRITERIA: Admitted to unit between February and March 2003. EXCLUSION CRITERIA: Colour blind; non‐English speaking; not able to understand or confused. | BEIGE: Walls remained original colour of beige (similar to Sherwin Williams colour SW6658) in four rooms. PURPLE: Wall at foot of bed painted purple (SW6556) in two rooms. GREEN: Wall at foot of bed painted green (SW6451) in two rooms. ORANGE: Wall at foot of bed painted orange (SW6346) in two rooms. Otherwise rooms were of same decor and intervention colours were co‐ordinated with colours already present in the rooms (e.g. on bed curtains). Artwork was removed from the rooms. Rooms were double occupancy with western outlook. Curtains were combination of orange, yellow, green, blue, and purple. Laminate countertops were green, and floors were orange and green. Furniture was neutral shades of white, grey, or beech wood. | ANXIETY: Measured via STAI on day of discharge (after 2 to 5 days in hospital). Presented as mean (SD). No significant differences reported. LENGTH OF STAY: Extracted from patient notes by researcher (days). No SDs presented. No significant differences reported. PAIN MEDICATION REQUESTS: Extracted from patient notes by researcher. Presented as number of patients making requests and number of requests made (no SDs presented), subgrouped by first day, middle days, and final day. No significant differences reported. | Partients in this study were not approached for informed consent until Day 3 of the study. |

STAI: State Trait Anxiety Inventory

The intervention colours were painted on to one wall at the foot of the patient beds, and were colour co‐ordinated with the rest of the room (e.g. with the colours in the curtains). Colour descriptors were: beige (original room colour, similar to Sherwin Williams colour SW6658), purple (SW6556), green (SW6451), and orange (SW6346).

Health‐related outcomes assessed were: anxiety, pain medication requests, and length of stay.

Twelve excluded studies have been tabulated on decoration (Table 7).

7. Decoration: Characteristics of excluded studies.

| Study ID | Reason for exclusion |

| Becker 1980 | Outcomes not validated |

| Cooper 1989 | Qualitative report |

| Dickinson 1995 | Setting |

| Hewawasam 1996 | Study design |

| Hussian 1987 | Study design |

| Jacobs 1974 | Participants |

| Knobel 1985 | Descriptive article |

| Namazi 1989 | Study design |

| Rabin 1981 | Descriptive article |

| Rice 1980 | Outcomes |

| Steer 1975 | Counfounding |

| Steffes 1985 | Staffing confound |

Risk of bias in included studies on decoration:

In the one RCT (Edge 2003) on decoration, participants were randomly assigned by administrative staff, but the method is unclear, and concealment of allocation was not used. Blinding of group allocation was not possible. Length of stay and pain medication requests were obtained from patient records, and subjective anxiety assessment was not blinded. The study is small, but of the consenting participants completeness of data was achieved. The author does give a description of withdrawals, drop‐outs, and non‐consenting patients (participants were approached for consent after allocation). Overall 11 patients were not included in the study for reasons seemingly unrelated to the intervention (Table 6), and one of whom was withdrawn by the researcher because she felt the patient was falsely answering the questions on anxiety (because the patient feared that high anxiety would affect her length of stay). This study is at risk of selective outcome reporting. It is likely that there was adequate protection against contamination.

Findings from studies on decoration:

Anxiety

Studies with insufficient data for extraction:

Edge 2003 found no strong evidence of an effect between groups for the outcome anxiety.

Pain medication requests

Studies with insufficient data for extraction:

Edge 2003 found no strong evidence of an effect between groups for the outcome pain medication requests.

Length of stay

Studies with insufficient data for extraction:

Edge 2003 found no strong evidence of an effect between groups for the outcome length of stay.

Music

Description of studies on music:

The 85 included RCTs investigating music (Table 8), resulted in a total sample of 6061 patients. Including two cross‐over trials (of 24 and 20 participants respectively; Davis‐Rollans 1987; Wong 2001). There were 2980 patients allocated to music, and 3124 allocated to a control (leaving one unknown case due to poor reporting in Taylor 1998). Patient characteristics were not reported in all of the studies; however, based on the 69 studies that reported information on mean age (details for 1108 participants remain unknown), the mean population age was 53.82 years old (range 14 to 99 years old; NB. > 90% of participants were 18 or older). Based on the 71 studies that reported information on gender, there were 2874 males and 2642 females included in the review (545 unknown cases). Studies were conducted in 16 different countries, predominantly the USA (N = 43) and China (N = 10). Five studies were conducted in each of Sweden and Canada, four in Germany, three in each of England and Taiwan, two in each of Australia, Japan, Turkey, and India, and one in each of Spain, Austria, Thailand, Slovenia, and Poland (NB. one study was carried out in two countries). The use of music was investigated in patients waiting for medical procedures (N = 13), undergoing endoscopic examinations (N = 12), undergoing percutaneous or surgical medical interventions (N = 34), undergoing non‐invasive medical procedures (N = 6), during labor (N = 1), post‐surgery (N = 7), in coronary care or intensive care environments (N = 10), or in ward environments (N = 2).

8. Music [RCT]: Characteristics of included studies.

| Study ID | Methods | Participants | Interventions | Outcomes | Notes |

| Allen 2001 | RCT; 2 parallel groups. | DESCRIPTION: 40 day‐patients undergoing ophthalmic surgery in New York, USA. NUMBERS: 20 patients in each group. AGE, mean (range): Music group = 74 (51‐87), Control group = 77 (64‐88) years old. GENDER (male/female): Music group = 5/15, Control group = 5/15. ETHNICITY: not described. INCLUSION CRITERIA: Ambulatory surgical patients scheduled on the rosters of two ophthalmic surgeons. EXCLUSION CRITERIA: none described. | MUSIC GROUP: Patient choice of 22 types of music (e.g. soft hits, classical guitar, chamber music, folk music, popular singers from 1940's and 1950's), played via headphones throughout pre‐operative, surgical, and post‐operative periods. CONTROL GROUP: Standard care. | PHYSIOLOGICAL: HR and BP measured via Propaq Monitor (Protocol Systems, Inc., Beaverton, OR) every 5 minutes during pre‐operative, surgical, and post‐operative period. Averages for the last three recorded measures within each time period were used for analysis in the paper. For purposes of review, data is extracted for the mean post‐operative scores only. COGNITIVE APPRAISAL: Two Likert scales used to measure questions on coping and stress, validity unclear. Not extracted for review. | |

| Andrada 2004 | RCT; 2 parallel groups. | DESCRIPTION: 118 out‐patients undergoing colonoscopy in a Digestive Endoscopy Unit in Spain. NUMBERS: Music group = 63 patients, Control group = 55 patients. AGE, mean (SD): Music group = 46 (14.22), Control = 49 (13.88). GENDER (Male/Female): Music group = 31/32, Control group = 28/27. ETHNICITY: not specified. INCLUSION CRITERIA: 18‐75 years old, scheduled for ambulatory examination. EXCLUSION CRITERIA: anacusis or significant bilateral hearing loss, senile dementia, cognitive disorders, acute or chronic confusional syndromes, treatment with anxiolytic medication in 72 hours prior to examination. | MUSIC GROUP: Series of classical tracks (e.g. Bach, Grieg, Mozart, Delibe, Faure, and Mendelssohn) played via headphones during procedure. CONTROL GROUP: Wore headphones but did not receive music throughout the procedure. | ANXIETY: State anxiety measure pre and post procedure using the STAI; Reported as post ‐ pre difference with 95% CI. ABNORMAL EVENTS: BP, capillary oxygen saturation, and HR were monitored using a Datex‐Ohmeda 3800 pulse oximeter and Nissei KTJ‐20 sphygmomanometer. Abnormal events arising from these parameters e.g. hypoxaemia, hypotension, hypertension, bradycardia, and tachycardia were recorded. | There were no significant differences between groups regarding abnormal events. This data has not been extracted for the review. |

| Argstatter 2006 | RCT; 3 parallel groups. | DESCRIPTION: 83 in‐patients undergoing cardiac catheterization in Germany. NUMBERS: Music group = 28, Control group = 27, Coaching group excluded from review. There are some discrepancies as to reported numbers in the paper, which also states there were 28 people in the control group. AGE, mean (SD) [range]: Music group = 65.8 (8.4) [49‐83], Control group = 67.5 (14.0) [28‐83]. GENDER (male/female): Music group = 16/12, Control group = 15/12. ETHNICITY: not described. INCLUSION CRITERIA: Patients were undergoing cardiac catheterization for the first or second time. EXCLUSION CRITERIA: none described. | MUSIC GROUP: Music was played via headphones, which were worn half on so patients could still hear the medical personnel, during the cardiac catheterization. A music therapist was present only to control the volume. Music played was "Entspannung" [relaxation] by Markus Rummel, composed specially for relaxation. CONTROL GROUP: Standard care. This group did not have the addition of a music therapist present during the cardiac catheterization. COACHING GROUP: Excluded from review. | ANXIETY: Measured via the STAI before and after cardiac catheterization. Unclear whether post measurements were taken on the following day after cardiac catheterization. PHYSIOLOGICAL: BP and Pulse are reported as pre‐ and post‐measurements. Unclear how measurements were obtained. SUBJECTIVE MUSIC QUESTIONNAIRE: excluded from review. | |

| Ayoub 2005 | RCT; 3 parallel groups. | DESCRIPTION: 90 patients undergoing urological surgery with spinal anaesthesia and PCS in Connecticut (USA) and Beirut (Lebonon). NUMBERS: Music group = 31, White noise = 31, Operating room noise = 28. AGE, mean (SD): Music group = 55 (12), White noise = 54 (12), OR noise = 57 (10) years old. GENDER (male/female): Music group = 28/3, White noise = 29/2, OR noise = 24/4. ETHNICITY: Unclear, although 36 recruited in USA, and 54 recruited in Lebonon. INCLUSION CRITERIA: 18‐60 years old; ASA status I‐III (although Table1 states music group had a classification of V). EXCLUSION CRITERIA: On psychiatric medications; a history of affective disorders. | MUSIC GROUP: Patients brought own music from home. WHITE NOISE: Delivered by SoundSpa Acoustic Relaxation Machine. OR NOISE: Delivered by mini‐amplifier speaker via occlusive headphones. This Radio Shack (R) has mini‐microphone for voice acquisition. All groups wore occlusive headphones. | PROPOFOL REQUIREMENTS: Recorded as mg/kg/min and % of patients not using any propofol. Unclear if data presented are the SDs, and if the data presented as mg/kg/min is based on the total N or % of patients who used propofol. Observers Assessment of Alertness/Sedation Scale (OAA/S): Data not presented. PACU LENGTH OF STAY. (not primary outcome)‐ unclear whether the numbers presented are mean and SD. | Data not extracted for meta‐analysis. |

| Bally 2003 | RCT; 2 parallel groups. | DESCRIPTION: 107 patients undergoing diagnostic coronary angiography or a percutaneous intervention procedure, in Ontario, Canada. NUMBERS: Music group = 56 patients, Control group = 51 patients. AGE, mean (SD): Music group = 59 (11), Control group = 58 (11). GENDER (Male/Female): at enrolment: Music group = 34/24, Control group = 30/25. ETHNICITY: not specified. INCLUSION CRITERIA: 1st time diagnostic coronary angiography or a percutaneous intervention procedure, speak and read English, cognitively orientated. EXCLUSION CRITERIA: major auditory deficits. | MUSIC GROUP: patient selected music (classical, soft rock, relaxation, country, own/other) played via headphones before, during, and after procedure, continued as the patient desired. CONTROL GROUP: standard care (no music). | ANXIETY: State Anxiety via STAI pre and post procedure; PAIN INTENSITY: measured via 100mm VAS pre and post procedure (data extracted); PAIN RATING: measured via VRS pre and post procedure; APICAL HR (bpm): measured via cardiac monitor; BP (mm Hg): measured via pressure dynamometer and arterial pressure monitoring; HR and BP were taken at 4 points: (1) baseline; (2) after sheath insertion; (3) end of procedure; (4) after procedure, before sheath removal. Not enough information provided for data extraction of HR and BP. | See Cepeda 2006 for details on music for pain relief. |

| Barnason 1995/1996 | RCT; 3 parallel groups. | DESCRIPTION: 96 in‐patients in the cardiovascular ICU and progressive care units having undergone elective coronary artery bypass grafting, in USA. NUMBERS: Music group = 33, Music+video group = 29, Scheduled rest group = 34. AGE, mean (SD): 67 (9.9) years old. GENDER (male/female): 65/31. ETHNICITY: White = 96 (100%) INCLUSION CRITERIA: Orientated to person, time and place; speak and read English; 19 years or older; extubated within 12 hours of surgery; removal of intra‐aortic balloon pump within 12 hours of surgery. EXCLUSION CRITERIA: Currently using one of the intervention techniques; major hearing deficit. | MUSIC GROUP: Choice of 5 tapes: 'Country Western Instrumental' or 'Fresh Aire' by Mannheim Steamroller, 'Winter into Spring' by George Winston, or 'Prelude' or 'Comfort Zone' by Steven Halpern. Played via headphones for 30 minutes. MUSIC + VIDEO GROUP: Barnason 1995 states: Choice of 2 Steven Halpern tapes: 'Summer Wind' or 'Crystal Suite'. Each is 30 minutes of soft instrumental with visual imaging. Zimmerman 1996 states: Choice of three 30 minute videocassettes by Pioneer Artist ('Water's Path', 'Western Light', or 'Winter'). SCHEDULED REST: 30 minutes of rest in bed or chair, visitors and staff requested not to disturb. 2 x 30 min intervention periods during afternoons of post‐operative days 2 and 3. Lights dimmed. | Barnason 1995 reports: STATE ANXIETY: measured using STAI at three time‐points: pre‐operatively, before intervention on 2nd post‐operative day, and after intervention on 3rd post‐operative day. ANXIETY: taken using NRS before and after each intervention session. PHYSIOLOGICAL: HR (bpm) and BP (mm Hg) taken using the Kendall BP Monitor (Model 8200)‐ not enough data presented for extraction. MOOD: Measured using a NRS‐ not a validated outcome. Zimmerman 1996 reports: PAIN: Pain was measured with a 10‐point VRS before and after each session, and with the McGill Pain Questionnaire (scores are given for the subscales and the present pain index rating scale) administered once prior to the first session, and once after the second session. SLEEP: Measured with the Richards‐Campbell Sleep Questionnaire (RSQ), administered between 7am and 9am on the third post‐operative day. | Data extracted for state anxiety (STAI measure).

Patients in the music group showed a significant improvement in mood after the 2nd intervention when controlling for pre‐intervention mood rating. No differences between groups were found for anxiety on either data collection tool. Physiological measures did not differ between groups, however there were significant differences over time (regardless of group), indicating a generalised relaxation response.

Authors conclude that although no intervention was overwhelmingly superior, all groups demonstrated a relaxation response. See Cepeda 2006 for details on music for pain relief. |

| Binnings 1987 | RCT; 2 parallel groups. | DESCRIPTION: 20 patients undergoing regional anaesthesia in North Carolina, USA. NUMBERS: 10 patients in each group. AGE: Not stated. GENDER: Not stated. ETHNICITY: Not stated. INCLUSION CRITERIA: Patients scheduled for regional anaesthesia, 18‐65 years old. EXCLUSION CRITERIA: Taking tranquilizers or psychoactive medication. | NATURE TAPES: choice of sounds of birds, the ocean, a lagoon, or deeply resonant chimes, played for the duration of the surgery. CONTROL: standard care. | STATE ANXIETY: STAI administered pre‐operatively and one hour post‐operatively to calculate the change score. SEDATION MEDICATION: amount of Methohexital (mg) and Fentanyl (cc) administered by the anaesthetist was recorded. The anaesthetist was instructed to administer as much sedation as needed for a safe and comfortable experience with regional anaesthesia. Data extracted for Fentanyl for analysis ( P < 0.025 for differences between groups for both medications in favour of nature sounds). | Scores given for state anxiety are outside of the normal range for this questionnaire (20‐80). Method of calculating scores is not described. SDs calculated from t‐values presented for the difference in means between groups. |