Abstract

Background

Overground gait training forms a major part of physical therapy services for chronic stroke patients in almost every setting. Overground gait training refers to physical therapists' observation and cueing of the patient's walking pattern along with related exercises, but does not include high‐technology aids such as functional electrical stimulation or body weight support.

Objectives

To assess the effects of overground physical therapy gait training on walking ability for chronic stroke patients with mobility deficits.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (last searched March 2008), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library Issue 2, 2008), MEDLINE (1966 to May 2008), EMBASE (1980 to May 2008), CINAHL (1982 to May 2008), AMED (1985 to March 2008), Science Citation Index Expanded (1981 to May 2008), ISI Proceedings (Web of Science, 1982 to May 2006), Physiotherapy Evidence Database (http://www.pedro.org.au/) (May 2008), REHABDATA (http://www.naric.com/research/rehab/) (1956 to May 2008), http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (May 2008), http://www.controlled‐trials.com/ (May 2008), and http://www.strokecenter.org/ (May 2008). We also searched reference lists of relevant articles, and contacted authors and trial investigators.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing overground physical therapy gait training with a placebo intervention or no treatment for chronic stroke patients with mobility deficits.

Data collection and analysis

Pairs of authors independently selected trials. Three authors independently extracted data and assessed quality. We contacted study authors for additional information.

Main results

We included nine studies involving 499 participants. We found no evidence for a benefit on the primary variable, post‐test gait function, based on three studies with 269 participants. Uni‐dimensional performance variables did show significant effects post‐test. Gait speed increased by 0.07 metres per second (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.05 to 0.10) based on seven studies with 396 participants, timed up‐and‐go (TUG) test improved by 1.81 seconds (95% CI ‐2.29 to ‐1.33), and six‐minute‐walk test (6MWT) increased by 26.06 metres (95% CI 7.14 to 44.97) based on four studies with 181 participants. We found no significant differences in deaths/disabilities or in adverse effects, based on published reports or personal communication from all of the included studies.

Authors' conclusions

We found insufficient evidence to determine if overground physical therapy gait training benefits gait function in patients with chronic stroke, though limited evidence suggests small benefits for uni‐dimensional variables such as gait speed or 6MWT. These findings must be replicated by large, high quality studies using varied outcome measures.

Plain language summary

Overground physical therapy gait training for chronic stroke patients with mobility deficits

Stroke is a leading cause of serious, long‐term disability in the United States, with 700,000 new or recurrent attacks each year. Two‐thirds of survivors have difficulty walking immediately after suffering a stroke, and six months later over 30% still cannot walk without assistance. Overground gait training forms a major part of physical therapy services for chronic stroke patients and is aimed at improving gait function. Overground gait training involves the physical therapist observing and cueing the patient's walking pattern, along with related exercises(it does not include use of high‐technology aids). We reviewed nine studies, with 499 participants, that investigated the effectiveness of overground gait training for improving overall measures of gait function. No evidence was found for a benefit on gait function at the end of the trial, based on the three available studies (269 participants). Other single measures of performance did show significant effects post‐test. Gait speed increased by 0.07 metres per second, based on seven studies with 396 participants. The timed 'up‐and‐go' test improved by 1.81 seconds, and the six‐minute‐walk test increased by 26.06 metres, based on four studies with 181 participants. Even fewer data were available at three‐month follow up. No significant differences in deaths/disabilities or in adverse effects were found between groups. Therefore, we found insufficient evidence to determine if overground physical therapy gait training improves gait function in patients with chronic stroke. The more targeted interventions for overground gait training used in recent studies suggest small and short‐term benefits for performance measures like gait speed, the timed up‐and‐go test, and distance walked in six minutes. Along with the small number of large, high quality, randomised controlled trials, limitations of this review include the wide range of disabilities in the stroke patients involved, the slow rate of recovery for chronic stroke patients, incomplete descriptions of the experimental interventions in studies of community physical therapy that included overground gait training, the blunt nature of the primary variable ‐ gait function, the limited duration of follow up (generally less than four months), and the diverse outcomes measured in the trials. Additional well‐designed randomised controlled trials of sufficient size and quality are needed to clarify the effects of overground physical therapy gait training.

Background

Stroke is a leading cause of serious, long‐term disability in the United States, with about 700,000 new or recurrent attacks each year (AHA 2005). Almost two‐thirds of the immediate survivors have initial mobility deficits (Jorgensen 1995; Shaughnessy 2005), and six months after a stroke over 30% of survivors still cannot walk independently (Jorgensen 1995; Mayo 2002; Patel 2000). However, the relatively high rate of walking independence may mask substantial mobility deficits. One year after a stroke, half of community‐dwelling stroke survivors (and thus survivors with relatively good recovery) could not complete a six‐minute‐walk test (6MWT) and those that did were only able to walk 40% of their predicted normal distance (Mayo 1999). Intensive rehabilitation services, including physical therapy, can aid significant recovery within the first three to six months (Duncan 2002; Duncan 2005; OST 2003). However, few studies have addressed whether additional services for chronic patients (more than six months since stroke) will lead to further recovery in mobility, and if so which aspects of the services are most important.

Within physical therapy services for stroke, gait training forms the major component of interventions, at least for acute patients (less than six months since stroke) (Jette 2005). Gait training refers to a wide range of physical therapy interventions, all aimed at improving the functional activity of ambulation. Overground gait training, perhaps the predominant form, includes a physical therapist's observation and manipulation of the patient's gait over a regular floor surface, and is often accompanied by practice walking overground, and exercises specifically designed to improve gait. Overground gait training is performed in virtually every setting from home care to small outpatient to large rehabilitation units and reflects a basic element of physical therapist training. Recently, efforts aimed at improving rehabilitation of gait have shifted toward increased amounts of gait practice through use of mechanical devices or fitness oriented exercise protocols. A systematic review that considered treadmill training with or without body weight support for stroke patients did not find significant and consistent benefits compared with other gait training methods (Moseley 2003). A systematic review that considered fitness programmes for stroke patients (Saunders 2004) found no evidence that cardiorespiratory training, or a combination of cardiorespiratory and strength training, leads to an increase in comfortable walking speed. In contrast, that review did find limited evidence that cardiorespiratory training improves functional ambulation category and maximum walking speed though those gains were achieved through the use of high‐technology devices like treadmills with or without body weight support. Interestingly, no systematic review has specifically addressed whether the less technologically demanding intervention of overground gait training is effective at improving mobility in stroke patients. While there is an overwhelming clinical consensus that overground gait training is needed during the acute stage of recovery for those patients who can not walk independently (Bates 2005), there has been little discussion of whether overground gait training would be beneficial for chronic patients with continuing mobility deficits.

Objectives

The purpose of this review is to evaluate whether overground physical therapy gait training is effective at improving walking ability for chronic stroke patients with mobility deficits. We measured effectiveness based on:

multi‐dimensional measures of gait function;

performance measures such as overground gait speed, the timed up‐and‐go test (TUG) and the 6MWT;

adverse events, and death or disability.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing overground physical therapy gait training with no intervention or a control intervention (other rehabilitative techniques that do not include gait training).

Types of participants

Adults (over 18 years) who have had a stroke at least six months prior to inclusion in the study and who have mobility deficits; that is, they use an assistive device, exhibit an abnormal gait pattern or have slowed gait speed. Participants must have the cognitive ability to follow directions and participate in physical therapy treatments. There were no restrictions on the participants' living environment or the setting in which care was received.

Types of interventions

Overground gait training was the intervention of interest. For the purposes of this review, we defined overground gait training as treatment that consisted of at least one of the following:

real‐time cueing of the patient's gait through the use of manual, verbal, positional, or rhythmic cueing techniques;

practice of the walking pattern overground; and/or

pre‐gait activities such as step‐up and step‐down exercises, dynamic balance training, weight‐bearing exercises to strengthen the lower extremities, and other exercises that require standing and weight shifting.

Interventions that did not include consistent face‐to‐face interactions between the therapist and patient (such as home exercise programmes) or whose primary goal was not to improve gait (such as progressive resistance training using exercises for isolated muscle groups) do not fit within this definition. In addition, gait training interventions that focus on the use of treadmills, complex technical equipment such as body weight supported treadmill training, functional electrical stimulation, biofeedback based on electromyography (EMG) or joint‐position measurement, or virtual reality systems, do not fit within this definition. The rationale for this restrictive definition is to focus on the types of gait training that are available in a typical community‐based physical therapy facility or during home‐care visits by a physical therapist.

We only included studies if the main intervention was overground gait training as defined above. We excluded studies that only used treadmill training, only used technologically demanding forms of gait training like body weight supported treadmill training, only used progressive resistance training without gait‐oriented exercises, or only included home‐care programmes. We included interventions that combined overground gait training with other rehabilitation techniques if the main intervention focused on either full‐gait activities (items 1 and 2 from the above definition) or on pre‐gait activities (item 3).

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcome measure is gait function. Gait function was assessed by any of various multi‐dimensional, ordinal scales that evaluate gait function and that are validated for use with stroke patients. Suitable scales included the following:

Rivermead Motor Assessment (RMA) (Finch 2002; Lincoln 1979) or the Rivermead Mobility Index (RMI) (Collen 1991; Hsieh 2000);

Motor Assessment Scale (MAS) (Carr 1985; Teasell 2005);

Stroke Rehabilitation Assessment of Movement (STREAM) (Daley 1997);

Barthel Index (Mahoney 1965; Teasell 2005).

In three studies (Green 2002; Lin 2004; Wade 1992) multiple outcome measures fit our definition of 'walking ability.' In Green's study, the RMI and the Barthel Index were reported; Lin reported both the STREAM and the Barthel Index; Wade reported both the RMA and the Barthel Index.

When considering which of the scales to designate as the primary measure of walking ability, we relied on the purpose and type of instrument. Since the goal of overground gait training is to improve the patient's ability to walk in a functional context, we preferred a multi‐dimensional scale that directly measured walking performance within a functional context. Both the RMI and the STREAM are clinical observation instruments designed to measure motor performance for persons with stroke. The RMI uses a hierarchical scoring system to measure motor performance for three subscales: Total Body Movements; Leg and Trunk Movements; and Arm Movements. The STREAM is designed to evaluate basic motor ability and also has three subscales: Voluntary Motor Upper Extremity; Voluntary Motor Lower Extremity; and Basic Mobility. The Barthel Index has 10 items and is designed to measure functional independence in self‐care and mobility rather than functional performance per se. It is administered in various formats including observational, written, and oral self‐reports. All four scales are validated for use with stroke patients and have shown adequate internal validity and test‐retest reliability (Finch 2002; Teasell 2005). Since the RMI and STREAM are focused more precisely on judging the quality of motor performance, as opposed to the Barthel's focus on ability to function independently, we preferred the RMI or the STREAM over the Barthel Index. In each of the studies that evaluated at least one of these measures, the study provided data on either the RMI or the STREAM but not both, and also provided data on the Barthel Index. Hence, we designated the RMI or STREAM as the primary outcome measure depending on which was available, and then considered the Barthel Index as an unanticipated secondary measure that provided information on the participant's ability (or inability) to function independently.

Several other secondary outcome measures assessed independent walking performance with objective, quantitative variables.

Gait speed measured over a short distance (10 metres or less) (Finch 2002; Murray 1967).

TUG (Matthias 1986; Podsiadlo 1991; Teasell 2005).

6MWT (Butland 1982; Finch 2002).

We analysed three additional secondary outcome measures when available in the identified studies: quality of life, adverse events, and death or disability. Quality of life was measured by validated multi‐dimensional, ordinal, scales such as the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Health Survey Questionnaire, the Frenchay Activities Index, the Nottingham Health Profile, the Quality of Life Index, and the Stroke Adapted Sickness Impact Profile (Finch 2002). The prevalence of adverse events during the treatment period was used as a measure of the safety of the intervention. Adverse events were categorised into injurious falls, other injury, major cardiovascular events, and any other adverse outcomes. Death and disability was defined based on the Stroke Unit Trialists' Collaboration definitions for death or dependency, and death or institutional care (Duncan 2002). The criterion for dependency is a score less than 18 on the Barthel Index or greater than two on the Modified Rankin Scale, while institutional care refers to care in a residential home, nursing home or hospital at the end of the scheduled follow up.

For inclusion in the analysis, outcome measures must have been recorded prior to the intervention and immediately following the intervention. We examined follow‐up data for the follow‐up point closest to three months after the intervention.

Search methods for identification of studies

See the 'Specialized register' section in the Cochrane Stroke Group module in The Cochrane Library.

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group's Trials Register, which was last searched by the Review Group Co‐ordinator in March 2008. In addition we searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library Issue 2, 2008), MEDLINE (1966 to May 2008), EMBASE (1980 to May 2008), CINAHL (1982 to May 2008), AMED (1985 to March 2008), Science Citation Index Expanded (1981 to May 2008), ISI Proceedings (Web of Science, 1982 to May 2006), the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (http://www.pedro.org.au/) (May 2008), REHABDATA (http://www.naric.com/research/rehab/) (1956 to May 2008), http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ (May 2008), http://www.controlled‐trials.com/ (May 2008), and http://www.strokecenter.org/ (May 2008) (see Appendix 1).

In an effort to identify further published, unpublished and ongoing trials, we:

examined the reference lists from retrieved articles;

liaised with investigators of identified trials and authors of relevant Cochrane physiotherapy reviews; and

used Science Citation Index Cited Reference Search to track relevant papers.

We carried out the above searches in April 2006 and updated them in Spring 2008. When we combined the results and removed duplicates, we identified 3793 citations.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of trials

The studies retrieved by the electronic search were distributed to three review authors (RAS, EP, and YS). Based on titles and, where available, abstracts, each review author deleted the obviously irrelevant studies (that is, obviously false hits such as 'running during a tennis stroke'). We obtained abstracts for all remaining references. Two review authors (RAS and EP or RAS and YS) independently screened the remaining abstracts, classifying each study as 'definitely irrelevant' or 'possibly relevant'. Where there was disagreement between review authors, a third review author assessed the abstract, and discussion among the three review authors led to consensus. We obtained full references for all studies classified as 'possibly relevant'. The three review authors applied the selection criteria to these studies. We resolved disagreements by discussion to reach consensus.

Data extraction

For each study selected, the three review authors extracted and documented data relating to study participants (such as patients' age, time since stroke, side of hemiplegia, initial walking ability), details of the intervention, methodological quality, and numeric results, and recorded this information on a data coding form.The three review authors resolved disagreements by discussion. For those articles that did not contain sufficient information, we contacted the study authors.

Quality assessment

The three review authors independently assessed the methodological quality of the studies, with disagreements resolved by discussion. We evaluated quality according to the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008), by reporting the score for each of the 11 items contained in the PEDro Scale for Rating Quality of Randomized Controlled Trials (Maher 2003), and by determining whether validity has been established for each relevant outcome measure from the study. We considered the last category from the Cochrane Handbook (detection bias) in two parts: blinding of evaluators and reporting bias.

The PEDro scale is based on the Delphi List (Verhagen 1998) and includes the following items: specification of eligibility criteria; random allocation to groups; concealed allocation; groups similar at baseline; blinding of participants, therapists and assessors; primary outcome measure obtained from at least 85% of participants; presence of an intention‐to‐treat analysis; reporting of results of between‐group statistical comparisons; and report of point measures and measures of variability.

If an article did not contain information on the methodological criteria, we contacted the study authors for additional information.

Data synthesis

We conducted meta‐analyses for the comparisons listed in the 'Types of studies' section at the end of the treatment period, and again for data from the latest time point within the three months following the end of the intervention. Thus, we conducted meta‐analyses for the following two comparisons on all available variables:

Comparison 01: Overground gait training versus a control intervention at the end of the treatment period; and

Comparison 02: Overground gait training versus a control intervention at the three‐month follow‐up time point.

The review authors checked all the extracted data for agreement, with conflicts resolved through mutual discussion. Where necessary, we contacted study authors to request more information or data.

We used the Cochrane Review Manager software, RevMan 5.0, for all analyses (RevMan 2008).

For the primary outcome measure of walking ability, data were derived from validated, multi‐item, ordinal rating scales. The scales were treated as continuous data. Since various trials used different measurement scales (a scale of 1 to 15 for the RMI versus a scale of 1 to 100 for the STREAM), we calculated the meta‐analysis for gait function based on the standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). For the other outcome measure based on multi‐item ordinal data (Barthel Index), all of the trials used a single scale and thus, we analysed them using the mean difference (MD) method. For the continuous variables (gait speed, TUG, 6MWT) every study used the same unit of measure, hence, we did the meta‐analyses by calculating the MD and 95% CI. For the continuous variables, some trials provided only post‐test scores, while others provided change scores indicating post‐test/pretest, or follow‐up/pretest. We used change scores when they were available, along with a measure of their variability (Pang 2005; Salbach 2004; Wall 1987; Yang 2006) in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Section 9.4.5.2 (Higgins 2008). For dichotomous variables like death or dependency, we calculated relative risk (RR) and 95% CI. If the results were significant, we calculated the number needed to treat and 95% CI.

We quantified homogeneity between trial results using the I2 statistic. If the trials were homogeneous, we used a fixed‐effect model to combine the results across trials and checked the robustness of the results using a random‐effects model. If there was substantial heterogeneity (I2 > 50%), we calculated the overall effects using a random‐effects model and we performed a series of sensitivity analyses to investigate the reason for the heterogeneity. The sensitivity analyses included true versus unclear randomisation, concealed versus unconcealed allocation, acceptable versus unacceptable number of withdrawals, blinded versus unblinded outcome assessment, and the use of a validated or unvalidated outcome measure. If the data were highly heterogeneous we did not calculate overall effects.

We planned to test for publication bias using funnel plots, but did not do so because so few studies (fewer than nine) were available for any given analysis.

We planned three subgroup analyses. The first was designed to assess the effects of initial walking ability using the cut point established for walking dependency defined in a previous Cochrane Review (Moseley 2003). The second subgroup analysis investigated the nature of the intervention, comparing trials that used real‐time cueing versus those that used a combination of real‐time cueing and pre‐gait activities versus those that used only pre‐gait activities. The third subgroup analysis considered the extent of training defined as net hours of training. We planned the third subgroup analysis in case a substantial discrepancy in the extent of training was seen between trials. In that case, the cut point was the mid point of the range of values for extent of training observed in the identified studies. We performed each subgroup analysis only if a sufficient number of studies was available and the original finding showed a statistically significant effect (Sandercock 2006). In those cases, the Deeks method for investigating differences between subgroups was used (Deeks 2008).

Results

Description of studies

We identified a total of 3793 studies by July 2008. We considered 92 for further review based on their abstracts and titles. Of those, we excluded 82 studies as shown in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table, and one study is ongoing. The most common reason for exclusion was that the participants were not chronic stroke patients or the control group included gait training and therefore could not serve as a true control. We reviewed the nine remaining studies in detail (see the 'Characteristics of included studies' table). Taken together, the included studies recruited 499 participants, and their data were assessed in the following comparisons:

Comparison 1: Overground gait training versus control at the end of treatment;

Comparison 2: Overground gait training versus control at three‐month follow up.

All of the included studies were randomised controlled trials (RCTs), although two used randomised cross‐over designs (Lin 2004; Wade 1992). Follow‐up data were reported in five studies (Dean 2000; Green 2002; Lin 2004; Wade 1992; Wall 1987). For the two studies using cross‐over designs (Lin 2004; Wade 1992), only the first phase of the data was analysed here, rendering the comparison a randomised comparison between an intervention group and a no treatment control group. For these two studies, follow‐up data could not be analysed as the control group received the experimental intervention during the usual follow‐up period.

In addition, for two studies (Salbach 2004; Wall 1987) parts of the data reported by the study authors did not meet our criteria, hence we only extracted parts of the data. In the Salbach trial (Salbach 2004), only 61 of 91 participants had a stroke at least six months before the beginning of the study. The author provided data on those 61 participants for us through personal communication (Salbach 2004). In the Wall study (Wall 1987), participants were randomised to one of four groups (on‐site physical therapy; home exercise programme; half on‐site and half home exercise; no treatment). Two of the treatment groups met our definition for overground gait training (on‐site physical therapy; and half on‐site and half home exercise) and one group met our definition for a control group that refrained from walking exercises (no treatment group). We excluded data from the group that received home exercise only as it did not meet our definition for either the experimental or control interventions. Because the number of participants in the two treatment groups was small (five participants for each), they were combined following the methods outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Section 7.7.3.8 (Higgins 2008).

The number of participants for studies in Comparison 1 'Overground gait training versus control at the end of treatment' varied from 10 (Wall 1987) to 170 (Green 2002). For comparison 2 'Overground gait training versus control at three‐month follow up', the number of participants varied from 12 (Dean 2000) to 63 (Pang 2005). Note that these figures only count those participants who were assigned to groups that are analysed here. In Salbach (Salbach 2004) and Wade (Wade 1992), additional participants were enrolled and completed the original studies but are not considered here.

We have detailed the characteristics of participants in the included studies in Table 1, and summarise the information here.

1. Study participants.

| Study | Age | Sex | Time since stroke | First stroke? | Mobility criteria | Cognitive criteria | Comorbidities |

| Dean 2000 | No limit; Exp = 66 y; Ctl = 62 y | 5 F; 7 M | ≥ 6 mo | Yes | Can walk 10 m independently with or without assistive device | — | Medical conditions that preclude participation |

| Green 2002 | > 50 y; Exp = 72 y; Ctl = 74 y | 75 F; 95 M | > 1 y | No | None | Dementia | Severe comorbidity, bedfast |

| Lin 2004 | No limit; Exp = 61 y; Ctl = 63 y | 6 F; 14 M | > 1 y | No | BI score between 5 and 14 | Inability to follow directions | None |

| Pang 2005 | > 50 y; Exp = 66 y; Ctl = 65 y | 26 F; 37 M | > 1 y | Yes | Can walk 10 m independently with or without assistive device Hemiparesis | — | Serious cardiac disease, uncontrolled blood pressure, pain while walking, other neurological conditions, or other serious diseases that preclude participation |

| Salbach 2004 | No limit; Exp = 69 y; Ctl = 73 y | 35F; 56 M | < 1 y, but only analysed data for > 6 mo | No | Can walk 10 m independently with or without assistive device Results of 6MWT below age and gender norms | Minimum score on mental competency test (MMSE) | Comorbidity that would preclude participation in either intervention, neurological deficit caused by metastatic disease |

| Wade 1992 | No limit; Exp = 72 y; Ctl = 72 y | 47 F; 47 M | > 1 y; < 7 y | No | — | None | None |

| Wall 1987 | 45 to 70 y; Exp and Ctl not reported | Not reported | > 1.5 y; < 10 y | No | Can walk with or without a cane, reduced support phase time on affected limb; stroke related mobility deficit | Cognitive disturbances | Serious unstable medical condition, intractable pain, incontinence |

| Yang 2006 | 45 to 74 y; Exp = 57 y; Ctl = 60 y | 16 F; 32 M | 36 m to 120 m post‐stroke | Yes | Hemiparetic, able to walk 10 m without an assistive device | Able to understand instructions and follow commands | Medically stable, no medical condition that would preclude participation, no health condition for which exercise in contraindicated |

| Yang 2007 | 45 to 80 y; Exp = 59 y; Ctl = 59 y | 11F; 14 M | 1 y to 28 y post‐stroke | Yes | Hemiparetic, able to walk 10 m without an assistive device | Able to understand instructions and follow commands | Medically stable, no health condition for which exercise in contraindicated, no neurologic or orthopedic diseases that might interfere with the study |

6MWT: 6‐minute‐walk test BI: Barthel Index Ctl: control Exp: experimental F: female m: metres M: male mo: months y: years

The average age of participants in any one group ranged from 57 years for the experimental group in Yang 2006 to 74 years in the control group for Green 2002. In all studies both sexes were represented. The percentages varied from 30% female in Lin 2004 to 50% female in Wade 1992.

The average time since stroke onset ranged from 6.1 months in the control group in Salbach 2004 to 64 months in the control group in Yang 2006. For one study (Salbach 2004), there was no preset limit on the required time since stroke. Thus, we communicated with the authors to obtain data for only those participants who began the study within six months since stroke onset. For one study, the required time since stroke was six months (Dean 2000). For six studies, the required time since stroke was one year (Green 2002; Lin 2004; Pang 2005; Wade 1992; Yang 2006; Yang 2007). For one study the required time since stroke was 18 months (Wall 1987). In two of the nine studies, an outer limit of five, seven or 10 years was set for time since stroke (Wade 1992; Wall 1987). In four studies, participants were only included if they had suffered only one stroke (Dean 2000; Pang 2005; Yang 2006; Yang 2007). The other studies allowed any number of strokes before the study began.

Mobility at beginning of study was assessed using various criteria. The most common was that the participant had to be able to walk independently for 10 metres with or without an assistive device (Dean 2000; Pang 2005; Salbach 2004; Yang 2006; Yang 2007). For those studies, the participant also had to have hemiparesis (Dean 2000; Pang 2005; Yang 2006; Yang 2007), or a walking deficit resulting from the most recent stroke (Salbach 2004). One study defined the criteria as an acceptable range of scores on the Barthel Index (Lin 2004), and two studies included a multi‐part definition listing various mobility deficits (Wade 1992; Wall 1987).

Six of the studies excluded participants due to some aspect of cognitive functioning (Green 2002; Lin 2004; Salbach 2004; Wall 1987; Yang 2006; Yang 2007). Of those, three referred to the inability to follow directions (Lin 2004; Yang 2006; Yang 2007), one to cognitive disturbances (Wall 1987), one to a minimum score on a test of mental competency (Salbach 2004) and one to dementia (Green 2002). Three studies did not specifically address cognitive function (Dean 2000; Pang 2005; Wade 1992), though both Dean and Pang may have excluded people with cognitive deficits since they allowed exclusion for 'medical conditions that precluded participation'. The exclusion criteria for defining other comorbidities were also variable. Restrictions ranged from none (Lin 2004), to a list of specific conditions (Pang 2005), to 'medically stable' (Yang 2006; Yang 2007), to leaving the decision about medical readiness to the participant's physician (Salbach 2004).

All of the studies used a sample of convenience. For two studies participants were recruited from a research database (Dean 2000; Wade 1992); for four studies participants came from hospitals or rehabilitation centres (Pang 2005; Salbach 2004; Wall 1987; Yang 2006); and for the remaining three studies participants were recruited from the community, including from some hospitals or rehabilitation centres (Green 2002; Lin 2004; Yang 2007).

Four studies reported using an intention‐to‐treat analysis (Green 2002; Pang 2005; Salbach 2004; Wade 1992). Of those four studies, only Salbach (Salbach 2004) imputed results for those participants who could not be evaluated while the other three used 'available case analysis.' The remaining studies did not report whether or not they used an intention‐to‐treat approach. Due to the low rate of participant withdrawals in four of the remaining five studies, however this omission is not likely to impose substantial bias.

The overground gait training intervention varied considerably across studies as shown in Table 2.

2. Interventions and controls.

| Study | Intervention | Individual or group | Frequency, duration | Setting | Control | Intervention details |

| Dean 2000 | Circuit training with functional lower extremity exercises | Group (4 to 6 patients supervised by 2 therapists) | 60 minutes per session, 3 times per week for 4 weeks; Net = 12 hours | Community setting | Upper extremity exercise programme with participant seated | Circuit training class with exercises aimed at strengthening the lower extremities and practising locomotor tasks 10 workstations were incorporated into the circuit training including: (1) sitting and reaching in different directions; (2) sit‐to‐stand from various chair heights; (3) stepping forward, backward, and sideways; (4) heel lift in standing; (5) standing with constrained base of support and tandem reaching for objects; (6) reciprocal leg flexion and extension in standing; (7) standing up from a chair, walking short distance, and returning to the chair; (8) walking on a treadmill; (9) walking over various surfaces and obstacles; and (10) walking over slopes and stairs |

| Green 2002 | Standard PT with emphasis on mobility skills | 1 to 1 | Variable length session with average of 44 minutes; 0 to 22 sessions with median of 3 per patient; frequency not reported; typical net = 2.25 hours | Home or community setting | No treatment | Individualised problem‐solving Included gait re‐education, exercise therapy, functional exercises, and balance re‐education |

| Lin 2004 | Standard PT with emphasis on mobility skills | 1 to 1 | 60 minutes per session, 1 session per week for 10 weeks Net = 10 hours | Home | No treatment | Motor facilitation, postural control training, functional ambulation and ADL training |

| Pang 2005 | Aerobic and mobility exercise programme | Group (9 to 12 patients supervised by 3 therapists) | 60 minutes per session, 3 times per week for 19 weeks Net = 57 hours | Community setting | Upper extremity exercise programme with participant seated | Cardiorespiratory and mobility exercises with time ranging from 10 minutes in week 1 to 30 minutes in week 19 Included mobility and balance tasks, leg muscle strengthening The exercise programme included: brisk walking; sit‐to‐stand; alternate stepping onto lower rises; walking in different directions; tandem walking; walking through an obstacle course; sudden stops and turns during walking; walking on different surfaces; standing on foam, balance disc, or wobble board; standing with one foot in front of the other; kicking ball with either foot; partial squats; and toe rises |

| Salbach 2004 | 10 walking‐related tasks | 1 to 1 | Variable length session; 3 times per week for 6 weeks Typical net = 9 hours | Community setting | Upper extremity exercise programme with participant seated | 10 walking related tasks designed to strengthen the lower extremities and enhance walking balance, speed and distance Included up to 10 minutes on treadmill per session Marching on the spot; stepping onto a step; walking forward, backward, and sideways between parallel lines or balance beam; kicking a ball against a wall; sit‐to‐stand; standing from a chair to walk and sit on a chair; walking over an obstacle course; 10 minutes walking at comfortable speed; 5 minutes of walking while carrying a grocery bag; walking 5 minutes at maximum speed; 5 minutes of walking backwards; and 5 minutes of climbing stairs |

| Wade 1992 | Standard PT with emphasis on mobility skills | 1 to 1 | Variable length sessions with average of 124 minutes (includes travel time); 1 to 11 sessions with mean of 4 per patient; frequency not reported Typical net = 8 hours | Home | No treatment | Problem‐solving approach and advice to caregivers Re‐education of abnormal gait components, supervised practice walking inside and outside, standing balance, obstacle courses, walking on uneven surfaces |

| Wall 1987 | Exercises to improve gait Intensity increased systematically |

1 to 1 | 60 minutes per session, 2 times per week for 6 months Net = 48 hours | Community setting | No treatment | 10 exercises for 5 minutes each designed to improve the gait pattern by increasing the ability of patients to transfer weight through the hemiplegic leg and increase time on affected leg in single support Exercises intensity progressed systematically |

| Yang 2006 | Task‐oriented progressive resistance strength training using pre‐gait activities, designed as a circuit training class | Group class | 30 minutes per session, 3 sessions per week for 4 weeks Net = 6 hours | Not reported | No treatment | Circuit training class 6 stations included standing and reaching in different directions; sit to stand from various chair heights; stepping forward, backwards, and sideways onto and off of blocks of various heights; heel rise and lowering while maintaining standing |

| Yang 2007 | Dual‐task walking exercises using a ball or other objects | Not reported | 30 minutes per session, 3 times per week for 4 weeks Net = 6 hours | Not reported | No treatment | Ball exercises, including walking while manipulating 1 or 2 balls Various sized balls were held, bounced, kicked while participants walked in a controlled setting Variable practice for walking conditions included walking forward, walking backward, walking on a circular route, and walking on an S‐shaped route |

ADL: activities of daily living PT: physical therapy

Three of the studies described their intervention as standard physical therapy care designed to improve a broad range of functional deficits including mobility and balance (Green 2002; Lin 2004; Wade 1992). We determined that the physical therapy care included a substantial amount of overground gait training based on the descriptions of the intervention, or because the results documented the types of physical therapy services provided, and/or based on personal communication with the study authors (Wade 1992). In those three studies, the therapy provided was tailored to the individual patient and the particular therapeutic services provided to each participant varied. For the other six studies, the intervention consisted of a standardised set of exercises uniquely designed by the investigators to improve gait and that were described within the report or in another published source. None of the studies provided an additional aspect to the intervention other than the physical therapy services described.

Five of the studies used one‐to‐one training approaches. For two studies that used group training the ratio of participants to instructors varied from 2:1 to 4:1 (Dean 2000; Pang 2005) and for the other two no information was given on the size of the group (Yang 2006; Yang 2007). The net treatment time provided by the intervention varied from a low of 0 treatment sessions for some participants in Green (Green 2002) to 57 sessions of 60 minutes each in Pang (Pang 2005). This translates into a net duration of treatment that ranged from 0 to 57 hours over a course of anywhere from 0 to six months. In the two studies where the number of sessions was determined individually for each participant, the range was 0 to 22 sessions in Green (Green 2002) and one to 11 sessions in Wade (Wade 1992). The setting for the intervention varied. Two studies provided the intervention only at the participant's home (Lin 2004; Wade 1992). One study provided the intervention both at home and at a community setting (Green 2002). Four studies provided the intervention only at a community setting (Dean 2000; Pang 2005; Salbach 2004; Wall 1987), and two did not report where the intervention was given (Yang 2006; Yang 2007).

The nature of the control intervention differed among the included trials. Four studies provided no treatment for the control group (Green 2002; Wall 1987; Yang 2006; Yang 2007). Two others (Lin 2004; Wade 1992) used a randomised cross‐over design so that the control group received the same treatment as given to experimental group during the second phase of the experiment. To reduce bias, however, the second phase of those studies was not considered here. The remaining studies provided some type of sham exercise programme for the control group. In Dean (Dean 2000), Pang (Pang 2005), and Salbach (Salbach 2004), the sham condition involved seated exercises for the upper extremities.

With regards to reporting of the primary outcome measure, only three of the included studies reported data on a multi‐item, ordinal scale of gait function. Two studies used the RMI (Green 2002; Wade 1992), one study used the STREAM (Lin 2004), and all three reported the aggregate scores. Those three studies also each reported the Barthel Index, which we analysed as an unanticipated secondary measure. The other included studies did not report any multi‐dimensional scale of walking ability in a functional context, and hence could not be assessed on our primary outcome measure.

With regards to our other secondary measures, all of the included studies reported some direct measure of walking performance. Seven of the included studies measured 'comfortable' or 'preferred' gait speed ‐ five based on a 10‐metre walk test (Dean 2000; Green 2002; Wade 1992; Yang 2006; Yang 2007), the others based on walking across a shorter distance (Salbach 2004; Wall 1987). In three studies, participants walked without an assistive device (Dean 2000; Yang 2006; Yang 2007). Assistive devices were allowed in three studies (Pang 2005; Salbach 2004; Wade 1992), whereas that detail was not reported in the other studies (Green 2002; Lin 2004; Wall 1987). In addition to gait speed, three studies assessed the TUG test (Dean 2000; Salbach 2004; Yang 2006), and four studies assessed the 6MWT (Dean 2000; Pang 2005; Salbach 2004; Yang 2006).

We expected to report on three additional secondary outcome measures: quality of life, adverse events, and death or disability. None of our included studies reported data on quality of life, however. Information on adverse events, and death or disability is provided by all nine studies.

All studies measured the outcome variables immediately before (within one week of) the intervention. In addition, for one study (Wade 1992) baseline variables were also measured a second time prior to the intervention to establish reliability of measurements. The assessment closest to the beginning of the intervention was used for reporting the baseline data. All studies measured the outcome variables immediately following the intervention. In one study (Wall 1987), the outcome variables were also measured monthly throughout the six‐month intervention period. Only data from the end of the intervention are used here. Three studies provided data for one or more follow‐up periods (Dean 2000 ‐ two months later; Green 2002 ‐ three and six months; Wall 1987 ‐ one, two, and three months later). For consistency across studies, we analysed the follow‐up data collected closest to three months after the intervention (Dean 2000 ‐ two months later; Green 2002 ‐ three months; Wall 1987 ‐ three months later).

Risk of bias in included studies

We carried out a pilot study of quality assessment on five articles; three that had been categorised as possibly relevant and two classified as irrelevant. The three review authors agreed on nine of the 11 PEDro criteria for all five studies, and for three of the four Cochrane criteria for all five studies. We resolved the remaining instances of disagreement by discussion leading to consensus. We considered this level of agreement acceptable to proceed with the full quality review.

All three authors assessed the methodological quality of the nine included studies using both the Cochrane items and the PEDro scale. The authors demonstrated 100% agreement on the Cochrane items and 99% agreement (98 out of a total of 99 test items) on the PEDro scale. The one item of disagreement was regarding blinding of participants in Salbach 2004, and it was resolved after discussion. We counted 10% of the PEDro test items and 9% of the Cochrane items as 'unknown' due to missing information.

We contacted seven trialists by email, requesting additional information on randomisation, nature of the experimental intervention, details of outcome measurement, results for subsets of participants, and adverse events. We received responses from five of the seven study authors (Dean 2000; Pang 2005; Salbach 2004; Wade 1992; Wall 1987) who provided details of methodology. In addition, email responses from Dean, Pang and Wade provided additional information on adverse events (Dean 2000; Pang 2005; Wade 1992). After receiving this information the following changes were made: concealed allocation was confirmed for Pang and Wade (Pang 2005; Wade 1992). In both cases, assignment was conducted by a co‐worker not involved in other aspects of the study. In addition, Wade verified that the random allocation was done using a random numbers table (Wade 1992). Personal communication from Salbach provided the subset of data needed for the participants from that study who met our inclusion criteria (Salbach 2004). We used published data only for two studies (Green 2002; Lin 2004). The ratings for the Cochrane items are listed in Table 3, and for the PEDro items in Table 4. The allocation concealment classification is detailed in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table. All studies were of good quality with quality scores based on Cochrane criteria ranging from 1.5 to 3, and PEDro scores ranging from 6 to 9.

3. Assessment of study quality.

| Study ID | Sequence generation | Concealed allocation | Blind participants, evaluators | Incomplete data | Selective reporting | Other bias | Cochrane score |

| Dean 2000 | Y: participants ranked according to gait speed and grouped into pairs Each pair was randomised by blind card drawing procedure |

Y: randomisation was performed by a person independent from the rest of the study | N: participants and treating therapists were not blind | N: 25% drop‐outs at post‐test, 33% drop‐outs at follow up 2 participants withdrew prior to the intervention (Exp = 1, Ctl = 1) with 1 of those citing transportation costs as the problem, a third participant (Ctl) withdrew prior to post‐test due to a serious medical condition At follow up, 1 additional participant (Exp) was unavailable |

P: outcomes assessor inadvertently observed a training session which may have resulted in incomplete blinding No reporting bias |

— | 1.5 |

| Green 2002 | Y: participants randomised to groups using random number table and 4‐length permuted blocks | Y: concealed allocation to groups by sealed, opaque envelopes delivered by an assistant blind to the study | N: participants and treating therapists were not blind | Y: 5% drop‐outs at post‐test, 11% drop‐outs at follow up During the treatment phase, 7 participants (Exp = 4, Ctl = 3) withdrew for unreported reasons, and 2 other participants (Ctl) died During the follow‐up phase, 5 participants (Exp = 4 and Ctl = 1) died, and 5 participants (Exp = 3 and Ctl = 2) withdrew for unreported reasons |

Y: outcome assessors were blind to group allocation at baseline, throughout treatment and at post‐test, but not for follow ups No reporting bias |

— | 3 |

| Lin 2004 | Unknown: randomisation is reported, but no procedures are given for randomisation | Unknown No procedures are given for allocation concealment |

Y: participants and treating therapists were blind | Y: 5% drop‐outs at post‐test 1 participant (Exp) withdrew during the intervention phase due to an unstable medical condition |

Y: outcome assessors were blind to group allocation | — | 3 |

| Pang 2005 | Y: participants stratified by sex Each participant was randomised by drawing ballots by an investigator independent of assessment and recruitment |

Y: randomisation was performed by an investigator independent of assessment and recruitment | N: participants and treating therapists were not blind | Y: 5% drop‐outs at post‐test During the intervention phase, 3 participants (Exp = 2, Ctl = 1) withdrew, 2 dropped out due to time constraints, and 1 (Exp) because he found the exercise too fatiguing |

Y: outcome assessors were blind to group allocation No reporting bias |

— | 3 |

| Salbach 2004 | Y: participants were stratified into blocks according to 3 levels of comfortable gait speed Randomisation was done by computer generated stratified random blocks |

Y: allocation was concealed by sealed envelopes created by a person blind to the study | N: participants and treating therapists were not blind | Y: 3% drop‐outs at post‐test 7 participants (Exp = 3, Ctl = 4) withdrew during the intervention phase: 1 (Exp) experienced groin pain, 2 (Exp = 1, Ctl = 1) wanted some other intervention, 1 (Exp) was unwilling to travel, 3 (Ctl) developed other medical conditions |

Y: outcome assessors were blind to group allocation No reporting bias |

— | 3 |

| Wade 1992 | Y: "Randomisation was restricted randomisation (permuted blocks of 10) with random number tables" | Y: allocation was concealed from the investigators and was performed by an assistant who took no part in further aspects of the study | N: participants and treating therapists were not blind | Y: 5% drop‐outs at post‐test, 9% drop‐outs at follow up 5 participants (Exp = 4, Ctl = 1) withdrew during the intervention phase for unreported reasons An additional 3 participants (Exp = 1, Ctl = 2) withdrew during the follow‐up period for unreported reasons |

Y: outcome assessors were blind to group allocation No reporting bias |

— | 3 |

| Wall 1987 | Unknown: randomisation is reported, but no procedures are given for randomisation | Unknown: no procedures are given for allocation concealment | N: participants and treating therapists were not blind | Y: no drop‐outs reported | P: did not report if outcome assessors were blind No reporting bias |

— | 1.5 |

| Yang 2006 | Unknown: randomisation is reported, but no procedures are given for randomisation | Y: allocation was concealed from the investigators and was performed by an independent person distributing sealed envelopes | Y: participants and treating therapists were blind | Y: no drop‐outs reported | Y: outcome assessors were blind to group allocation | — | 2.5 |

| Yang 2007 | Unknown: randomisation is reported, but no procedures are given for randomisation | Y: allocation was concealed from the investigators and was performed by an independent person distributing sealed envelopes | Y: participants and treating therapists were blind | Y: no drop‐outs reported | Y: outcome assessors were blind to group allocation | — | 2.5 |

Ctl: control Exp: experimental N: no P: possible Y: yes

4. PEDro scores.

| Study ID | PEDro score | Eligibility criteria | Baseline similar | Intention‐to‐treat | Statistics | Means & SDs |

| Dean 2000 | 7 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Green 2002 | 9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lin 2004 | 9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pang 2005 | 9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Salbach 2004 | 8 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Wade 1992 | 9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Wall 1987 | 6 | Vague | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Yang 2006 | 9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Yang 2007 | 9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

SD: standard deviation

Six studies (Dean 2000; Green 2002; Pang 2005; Salbach 2004; Yang 2006; Yang 2007) used a parallel group design with true randomisation to groups, while one study (Wall 1987) reported randomisation but no procedures were given. Two trials (Lin 2004; Wade 1992) used a cross‐over design with random allocation to the order of treatments. One study (Lin 2004) did not describe the method of randomisation, while one study (Wade 1992) used restricted randomisation (permuted blocks of 10) with random number tables.

Seven studies (Dean 2000; Green 2002; Pang 2005; Salbach 2004; Wade 1992; Yang 2006; Yang 2007) used concealed allocation of participants to groups, while two studies (Lin 2004; Wall 1987) did not describe allocation concealment.

One reason for the relatively low Cochrane quality scores relates to a problem found in most physical therapy studies; it is nearly impossible to keep the therapists providing the treatment and the participants blind as to whether they are receiving a behavioural intervention or not. As a result, only one of the nine studies (Lin 2004) was able to achieve blinding of therapists providing treatment. In contrast, the assessors were blinded to group allocation in six of the included studies (Lin 2004; Pang 2005; Salbach 2004; Wade 1992; Yang 2006; Yang 2007), blinding of assessors was incomplete in one study (Dean 2000), and blinding of assessors occurred at baseline and immediately after treatment but not in subsequent follow ups in one study (Green 2002). Blinding of assessors was not reported in one study (Wall 1987).

The withdrawal rate by the end of treatment was 15% or less in eight studies and was considered acceptably low based on the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomised controlled trials (Maher 2003); in contrast, it was 25% in one study (Dean 2000). The withdrawal rate for those studies reporting follow‐up data was also less than 15% for two studies (Green 2002; Wall 1987), but 33% (two participants each from the experimental and control groups) for Dean 2000.

Effects of interventions

Comparison 1: Gait training versus control at end of treatment

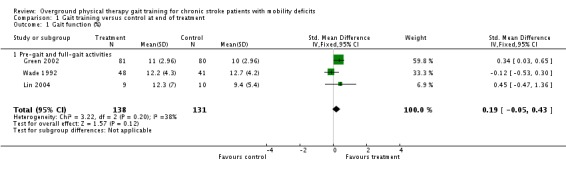

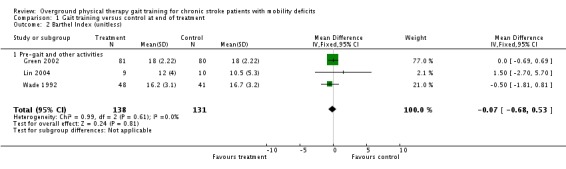

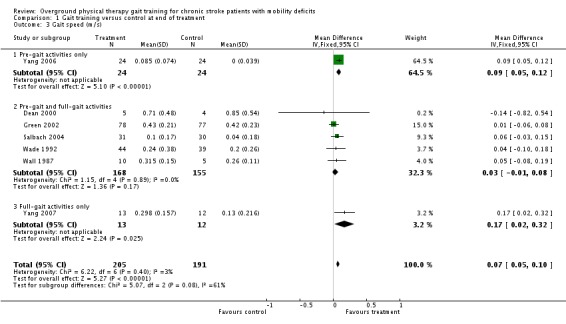

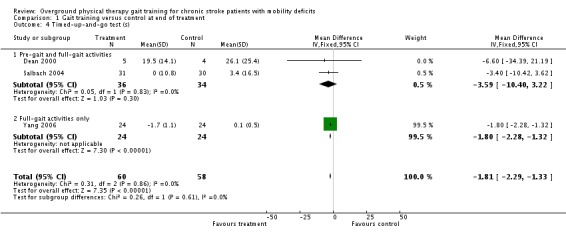

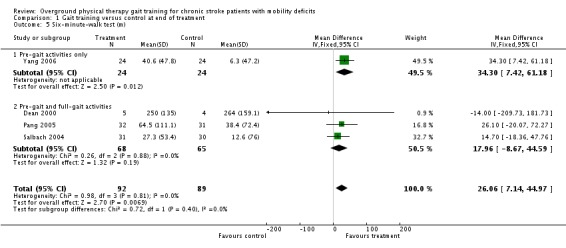

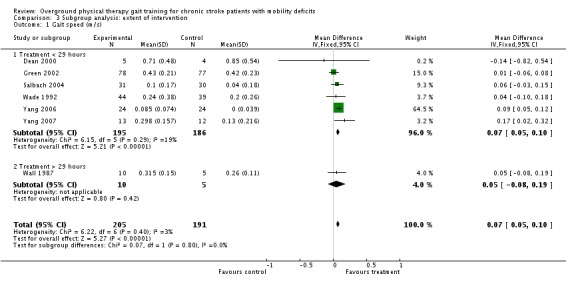

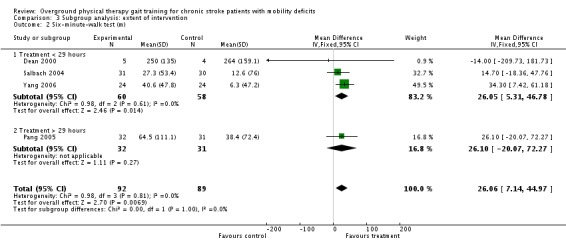

For the primary variable of gait function, we found no statistically significant difference between the experimental gait training group and the control group at the end of the treatment period (Analysis 1.1). In contrast, there were statistically significant differences for the secondary variables of gait speed, TUG test, and 6MWT, but not for the variable of Barthel Index (Analysis 1.2). For gait speed, the gait training group walked an average of 0.07 m/sec faster (95% CI 0.05 to 0.10) than the control group, as shown in Analysis 1.3. For the TUG test, the gait training group moved 1.81 seconds faster (95% CI ‐2.29 to ‐1.33) than the control group (Analysis 1.4). Similarly, for the 6MWT, the gait training group walked an average of 26.06 metres further (95% CI 7.14 to 44.97) than the control group, as shown in Analysis 1.5. Data for these comparisons came from three studies and 269 participants for gait function and the Barthel Index, from seven studies and 396 participants for gait speed, from three studies and 118 participants for the TUG test, and from four studies and 181 participants for the 6MWT. There was no evidence of substantial heterogeneity for any of the variables as shown by I2 values below 50%. Moreover, none of the results changed notably when we ran the analyses using a random‐effects model.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Gait training versus control at end of treatment, Outcome 1 Gait function (%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Gait training versus control at end of treatment, Outcome 2 Barthel Index (unitless).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Gait training versus control at end of treatment, Outcome 3 Gait speed (m/s).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Gait training versus control at end of treatment, Outcome 4 Timed‐up‐and‐go test (s).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Gait training versus control at end of treatment, Outcome 5 Six‐minute‐walk test (m).

Comparison 2: Gait training versus control at three‐month follow up

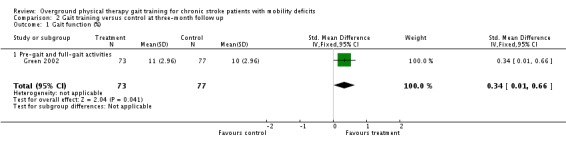

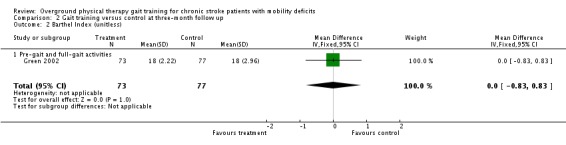

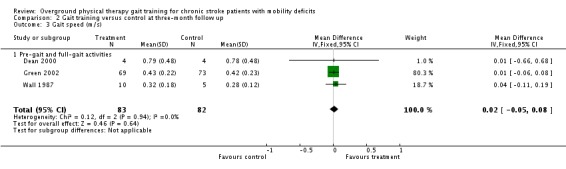

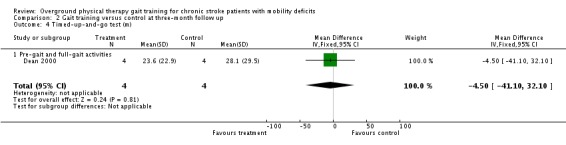

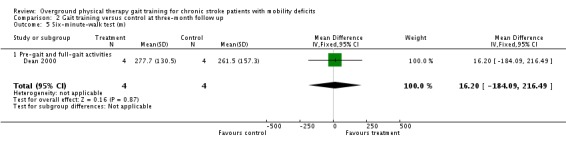

At the end of the three‐month follow‐up period, we found a statistically significant difference between the experimental and control interventions for the primary variable of gait function. The gait training group improved their gait function by a standardised mean difference of 0.34 units (95% 0.01 to 0.66) compared with the control group (Analysis 2.1), but this was based on results from only one study with 150 participants. We found no significant differences for the variables of Barthel Index (Analysis 2.2), gait speed (Analysis 2.3), TUG test (Analysis 2.4), or 6MWT (Analysis 2.5). Data for the secondary variables were derived from one study and 150 participants for the Barthel Index, three studies and 165 participants for gait speed, one study with eight participants for the TUG test, and one study of 34 participants for the 6MWT. The I2 values for all variables were below 50% indicating no substantial amount of heterogeneity. Additionally, results did not change substantially when we ran the analyses using a random‐effects model.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Gait training versus control at three‐month follow up, Outcome 1 Gait function (%).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Gait training versus control at three‐month follow up, Outcome 2 Barthel Index (unitless).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Gait training versus control at three‐month follow up, Outcome 3 Gait speed (m/s).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Gait training versus control at three‐month follow up, Outcome 4 Timed‐up‐and‐go test (m).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Gait training versus control at three‐month follow up, Outcome 5 Six‐minute‐walk test (m).

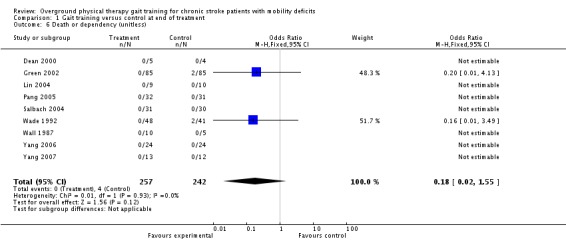

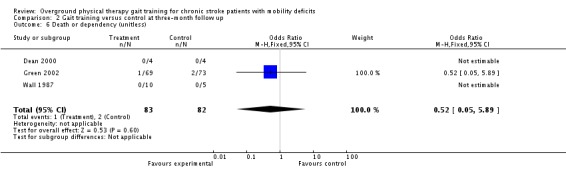

Other outcomes

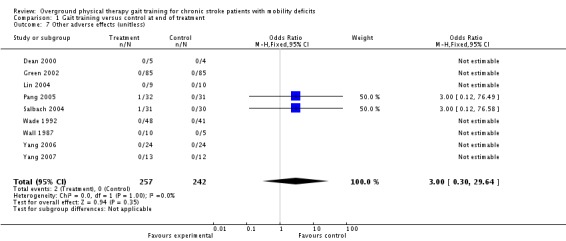

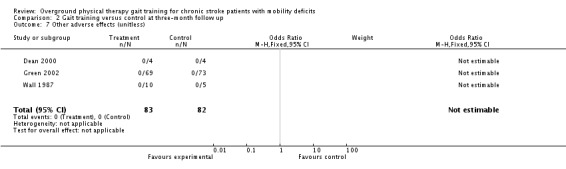

We analysed adverse events only in terms of 'death or dependency' and 'other adverse effects'. We did not analyse 'death or institutionalisation' since none of the included studies reported new instances of dependency or institutionalisation, and thus 'death or dependency' became equivalent to 'death or institutionalisation'. A total of four deaths occurred within the intervention period and these all occurred in the control groups, as shown in Analysis 1.6. During the three‐month follow‐up period, three deaths occurred in one study, as shown in Analysis 2.6. However, the odds ratio did not differ significantly from one either at the end of treatment or at follow up. Two adverse effects occurred within the experimental groups during the intervention period, but this did not result in a significant risk for the experimental condition (Analysis 1.6). One participant from Pang 2005 dropped out because he found the exercise too fatiguing, and one participant from Salbach 2004 dropped out due to groin pain. No other injuries or medical complications that could be plausibly linked to the intervention occurred in any study either during the intervention or follow‐up periods (Analysis 1.7; Analysis 2.7). Five falls that related to study procedures were reported in one study (Pang 2005) though none of them led to injury.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Gait training versus control at end of treatment, Outcome 6 Death or dependency (unitless).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Gait training versus control at three‐month follow up, Outcome 6 Death or dependency (unitless).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Gait training versus control at end of treatment, Outcome 7 Other adverse effects (unitless).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Gait training versus control at three‐month follow up, Outcome 7 Other adverse effects (unitless).

Subgroup analyses

We planned to do three subgroup analyses.

Effect of initial ability to walk independently as defined in Moseley (Moseley 2003).

Effect of type of gait training (full‐gait activities only versus a combination of full‐gait and pre‐gait activities versus pre‐gait activities only).

Extent of intervention ( more than or less than 29 hours).

For the first subgroup analysis, insufficient data were available within the included trials to determine which participants met the definition of walking dependency. Only two studies reported scales that could be used to determine the level of walking dependency among participants (Green 2002; Wade 1992), and data on gait function for dependent walkers could not be effectively separated from data for independent walkers for those studies. Moreover, very few participants met the definition for walking dependency even in these two studies ‐ just 14% in the Wade study, and less than 1% in the Green study. Given these impediments, we did not conduct a formal statistical analysis of the subgroups.

For the subgroup analysis on the type of gait training, one study used full‐gait activities only (Yang 2007), six studies used a combination of full‐gait and pre‐gait activities (Dean 2000; Green 2002; Pang 2005; Salbach 2004; Wade 1992; Wall 1987), and one study used only pre‐gait activities (Yang 2006). For Comparison 1, the only variables that showed significant effects overall were the secondary variables of gait speed, TUG test, and 6MWT. Hence, we conducted subgroup analyses for those secondary variables although results should be interpreted with caution since in each case only one of three subgroups was represented by multiple studies. For gait speed, a trend was evident between subgroups (Chi2 = 5.07, df = 2, P = 0.08), suggesting that the pre‐gait only subgroup and the full‐gait only subgroup continued to show differences between experimental and control interventions, whereas the combination subgroup (pre‐gait and full‐gait activities) did not (Analysis 1.3). No subgroup differences were evident for the TUG test (Analysis 1.4) or the 6MWT (Analysis 1.5). For Comparison 2, no subgroup analyses could be tested since the only variable that showed an overall effect (gait function) had only one study contributing data.

We also conducted analysis of subgroups with regards to extent of intervention. The net amount of training ranged from 2.25 hours to 57 hours, and the studies were divided according to the mid point of the range of net intervention durations or 29 hours. Thus, the subgroup analysis compared the two long‐duration studies (Pang 2005; Wall 1987) versus the seven short‐duration studies (Dean 2000; Green 2002; Lin 2004; Salbach 2004; Wade 1992; Yang 2006; Yang 2007). For Comparison 1, the only variables that showed significant effects overall were gait speed, TUG test, and 6MWT. We could not conduct the subgroup analysis for TUG test, however, since all of the studies fell into the low‐intensity subgroup. We found no significant subgroup differences for gait speed or 6MWT (Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.2). These results should be interpreted with caution since the high‐intensity group was represented by a single study in both subgroup analyses. At the end of the three‐month follow‐up period, the only variable that showed a significant effect overall was gait function, and insufficient data were available to perform the subgroup analysis.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis: extent of intervention, Outcome 1 Gait speed (m/s).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis: extent of intervention, Outcome 2 Six‐minute‐walk test (m).

Sensitivity analysis

We addressed a number of sensitivity analyses.

True versus unclear randomisation.

Concealed versus unconcealed allocation.

Acceptable versus unacceptable number of withdrawals.

Blinded versus unblinded outcomes.

Due to the small number of studies within each comparison, we examined sensitivity by performing post‐hoc analyses that eliminated one or more potentially biased studies to confirm the robustness of the original results.

True versus unclear randomisation

Five studies used true randomisation and four studies did not report how randomisation was achieved (Lin 2004; Wall 1987; Yang 2006; Yang 2007). We analysed all variables again after eliminating the studies with unclear randomisation procedures for Comparisons 1 and 2. Results for the secondary variables at the end of treatment were altered (Table 5); in this analysis, we found no significant effects for gait speed, the TUG test, or the 6MWT at the end of treatment. The results for Comparison 2 remained as previously reported.

5. Sensitivity analysis: true randomisation?

| Outcome or subgroup | Studies | Participants | Statistical method | Effect estimate |

| 1.1 Gait function (%) | 2 | 250 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.17 (‐0.08 to 0.42) |

| 1.2 Barthel Index (unitless) | 2 | 250 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.11 (‐0.72 to 0.50) |

| 1.3 Gait speed (m/s) | 4 | 208 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.03 (‐0.02 to 0.08) |

| 1.4 Timed up‐and‐go test (s) | 2 | 70 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐3.59 (‐10.40 to 3.22) |

| 1.5 Six‐minute‐walk test (m) | 3 | 133 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 17.96 (‐8.67 to 44.59) |

| 2.1 Gait function (%) | 1 | 150 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 (0.01 to 0.66) |

| 2.2 Barthel Index (unitless) | 1 | 150 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.00 (‐0.83 to 0.83) |

| 2.3 Gait speed (m/s) | 2 | 150 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.01 (‐0.06 to 0.08) |

| 2.4 Timed up‐and‐go test (s) | 1 | 8 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐4.50 (‐41.10 to 32.10) |

| 2.5 Six‐minute‐walk test (m) | 1 | 8 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 16.20 (‐184.09 to 216.49) |

m: metres s: second

Concealed versus unconcealed allocation

Seven studies reported concealed allocation of participant assignment and two studies did not report the details of how participants were assigned to groups (Lin 2004; Wall 1987). No substantial changes to the existence, direction or extent of significant effects resulted from eliminating the two studies that lacked concealed allocation. Moreover, the changes to effect size were minimal for gait speed, TUG test, and 6MWT at the end of treatment and for gait function at the three‐month follow up (Table 6).

6. Sensitivity analysis: concealed allocation?

| Outcome or subgroup | Studies | Participants | Statistical method | Effect estimate |

| 1.1 Gait function (%) | 2 | 250 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.17 (‐0.08 to 0.42) |

| 1.2 Barthel Index (unitless) | 2 | 250 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.11 (‐0.72 to 0.50) |

| 1.3 Gait speed (m/s) | 6 | 381 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.07 (0.05 to 0.10) |

| 1.4 Timed up‐and‐go test (s) | 3 | 118 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.81 (‐2.29 to ‐1.33) |

| 1.5 Six‐minute‐walk test (m) | 4 | 181 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 26.06 (7.14 to 44.97) |

| 2.1 Gait function (%) | 1 | 150 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 (0.01 to 0.66) |

| 2.2 Barthel Index (unitless) | 1 | 150 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.00 (‐0.83 to 0.83) |

| 2.3 Gait speed (m/s) | 2 | 150 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.01 (‐0.06 to 0.08) |

| 2.4 Timed up‐and‐go test (s) | 1 | 8 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐4.50 (‐41.10 to 32.10) |

| 2.5 Six‐minute‐walk test (m) | 1 | 8 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 16.20 (‐184.09 to 216.49) |

m: metres s: second

Acceptable versus unacceptable number of withdrawals

Eight of the nine studies reported an acceptable number of withdrawals (less than 15% of the total). As a result, we did a sensitivity analysis after removing the one study with a large number of withdrawals (Dean 2000). In the Dean study, 25% of participants were unavailable for the post‐test, and 33% withdrew prior to follow up. When the Dean study was removed from the analyses for which it had reported data, no substantial changes in the existence, direction or extent of significant effects occurred (Table 7); however the TUG test and the 6MWT could no longer be evaluated at follow up as only the Dean study contributed to those analyses.

7. Sensitivity analysis: acceptable number of withdrawals?

| Outcome or subgroup | Studies | Participants | Statistical method | Effect estimate |

| 1.1 Gait function (%) | 3 | 269 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.19 (‐0.05 to 0.43) |

| 1.2 Barthel Index (unitless) | 3 | 269 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.07 (‐0.68 to 0.53) |

| 1.3 Gait speed (m/s) | 6 | 390 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.07 (0.05 to 0.10) |

| 1.4 Timed up‐and‐go test (s) | 2 | 111 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.81 (‐2.29 to ‐1.33) |

| 1.5 Six‐minute‐walk test (m) | 3 | 172 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 26.43 (7.43 to 45.44) |

| 2.1 Gait function (%) | 1 | 150 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 (0.01 to 0.66) |

| 2.2 Barthel Index (unitless) | 1 | 150 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.00 (‐0.83 to 0.83) |

| 2.3 Gait speed (m/s) | 2 | 176 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.02 (‐0.05 to 0.08) |

| 2.4 Timed up‐and‐go test (s) | 0 | — | — | — |

| 2.5 Six‐minute‐walk test (m) | 0 | — | — | — |

m: metres s: second

Blinded versus unblinded outcomes

Seven of the nine studies reported that evaluators were blind to group allocation. The Dean study noted that one evaluator may have become partially exposed to group allocation part way through the study (Dean 2000), and the Wall study did not report on blinding (Wall 1987). Hence, we ran a sensitivity analysis removing the Dean and Wall studies, and no substantial changes in the existence, direction or extent of results occurred either at the end of treatment or at follow up (Table 8).

8. Sensitivity analysis: blind evaluators?

| Outcome or subgroup | Studies | Participants | Statistical method | Effect estimate |

| 1.1 Gait function (%) | 3 | 269 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.19 (‐0.05 to 0.43) |

| 1.2 Barthel Index (unitless) | 3 | 269 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.07 (‐0.68 to 0.53) |

| 1.3 Gait speed (m/s) | 5 | 372 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.07 (0.05 to 0.10) |

| 1.4 Timed up‐and‐go test (s) | 3 | 109 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.81 (‐2.29 to ‐1.33) |

| 1.5 Six‐minute‐walk test (m) | 3 | 172 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 26.43 (7.43 to 45.44) |

| 2.1 Gait function (%) | 1 | 150 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 (0.01 to 0.66) |

| 2.2 Barthel Index (unitless) | 1 | 150 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.00 (‐0.83 to 0.83) |

| 2.3 Gait speed (m/s) | 1 | 142 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.01 (‐0.06 to 0.08) |

| 2.4 Timed up‐and‐go test (s) | 0 | — | — | — |

| 2.5 Six‐minute‐walk test (m) | 0 | — | — | — |

m: metres s: second

Discussion

The primary aim of this review was to evaluate the effect of overground physical therapy gait training on the gait function of chronic stroke patients with mobility deficits. Results were mixed, with no significant effect for the primary variable at the end of treatment but small effects for several secondary variables. Our mixed findings may be due to the small number of studies that met the inclusion criteria, the small number of enrolled participants, and the lack of consistent outcome measures used in the included studies.

For the primary variable of gait function, meta‐analysis revealed that gait training (as compared to the control intervention) did not have a significant effect at the end of treatment. At follow up, there was a significant effect for the one study that measured gait function. Since the effect size at follow up (0.34, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.66) was a value generally considered to be small (Cohen 1988), and it was based on a single study, this result should be interpreted with caution. The lack of a sufficient number of trials precludes the review authors from making a conclusive statement about the effect of overground physical therapy gait training on gait function in patients with chronic stroke.

Results for the secondary variables of Barthel Index, gait speed, TUG, and 6MWT were mixed. Meta‐analysis revealed statistically significant effects for gait speed, TUG test, and 6MWT immediately after treatment. These effects can be compared to the 'smallest real difference' values derived for chronic stroke patients with hemiparesis (Flansbjer 2005). The smallest real difference provides a 95% CI around the standard error of the measurement, showing how large a change is needed to have 95% confidence that observed changes are not due to measurement error. Flansbjer and colleagues report smallest real difference intervals of 0.15 to 0.25 m/sec for gait speed, 2.59 to 3.75 seconds for the TUG test, and 37.3 to 66.0 metres for the 6MWT. The effect sizes from our meta‐analysis did not reach the lower end of these smallest real difference ranges, suggesting that while these secondary variables show statistically significant effects, the observed changes are unlikely to translate into reliable and important clinical improvements. For the variable Barthel Index, no significant effects were evident. At the three‐month follow up, no significant effects were evident among the secondary variables. Taken together, the observed effects for gait speed, TUG, and 6MWT are limited but may suggest a promising area for future work. The results for the TUG test and the 6MWT especially reflect recent research focused on well‐documented, specific, therapeutic protocols for overground gait training (Dean 2000; Pang 2005; Salbach 2004; Yang 2007; Yang 2007), some of which used methodologically rigorous placebo conditions but still included fewer than 100 participants each (Dean 2000; Pang 2005; Salbach 2004).

Very few adverse events or adverse effects were reported in the included studies. These results appear to reflect the relative safety of the experimental intervention in these studies as information on adverse events was obtained for all of the included studies either from the published article or from personal communication. Additional adverse events that did not lead to injury or medical complications or that appeared to be unrelated to the experimental procedures (new strokes, cancer diagnoses, falls in participants on a waiting list) may not have been recorded however, as they were not reported systematically.

Subgroup analyses on type of intervention (real‐time cueing only versus mixed types versus pre‐gait training only) and on extent of intervention (less than 29 hours versus more than 29 hours) revealed no significant effects. However, the results must be interpreted cautiously due to the small number of studies contributing.

Sensitivity analyses generated only one substantial change from the primary analyses. When studies with unclear randomisation procedures were eliminated, the secondary variables (gait speed, TUG test, and 6MWT) no longer showed significant effects at the end of the treatment phase. This lends additional caution to interpretation of the results, especially given that at most four studies contributed to the remaining analyses. Sensitivity analyses addressing unconcealed allocation, a large number of withdrawals, or unblinded evaluators did not change either the existence or size of effects notably.

Along with the relative paucity of large, high quality, randomised controlled trials on the effectiveness of overground gait training, limitations of this review include the large variability in the disability status of chronic stroke patients with mobility deficits, the slow rate of overall recovery for chronic stroke patients, the limited descriptions of the experimental interventions in studies focused on broadly‐based community physical therapy services that included overground gait training, the blunt nature of the primary variable ‐ gait function, the limited duration of follow up (generally no more than three months), and the diversity of outcome variables used by the included studies.