Abstract

Background

Standing up from a seated position is one of the most frequently performed functional tasks, is an essential pre‐requisite to walking and is important for independent living and preventing falls. Following stroke, patients can experience a number of problems relating to the ability to sit‐to‐stand independently.

Objectives

To review the evidence of effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving sit‐to‐stand ability after stroke. The primary objectives were to determine (1) the effect of interventions that alter the starting posture (including chair height, foot position, hand rests) on ability to sit‐to‐stand independently; and (2) the effect of rehabilitation interventions (such as repetitive practice and exercise programmes) on ability to sit‐to‐stand independently. The secondary objectives were to determine the effects of interventions aimed at improving ability to sit‐to‐stand on: (1) time taken to sit‐to‐stand; (2) symmetry of weight distribution during sit‐to‐stand; (3) peak vertical ground reaction forces during sit‐to‐stand; (4) lateral movement of centre of pressure during sit‐to‐stand; and (5) incidence of falls.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (June 2013), CENTRAL (2013, Issue 5), MEDLINE (1950 to June 2013), EMBASE (1980 to June 2013), CINAHL (1982 to June 2013), AMED (1985 to June 2013) and six additional databases. We also searched reference lists and trials registers and contacted experts.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials in adults after stroke where: the intervention aimed to affect the ability to sit‐to‐stand by altering the posture of the patient, or the design of the chair; stated that the aim of the intervention was to improve the ability to sit‐to‐stand; or the intervention involved exercises that included repeated practice of the movement of sit‐to‐stand (task‐specific practice of rising to stand).

The primary outcome of interest was the ability to sit‐to‐stand independently. Secondary outcomes included time taken to sit‐to‐stand, measures of lateral symmetry during sit‐to‐stand, incidence of falls and general functional ability scores.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened abstracts, extracted data and appraised trials. We undertook an assessment of methodological quality for random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessors and method of dealing with missing data.

Main results

Thirteen studies (603 participants) met the inclusion criteria for this review, and data from 11 of these studies were included within meta‐analyses. Twelve of the 13 included studies investigated rehabilitation interventions; one (nine participants) investigated the effect of altered starting posture for sit‐to‐stand. We judged only four studies to be at low risk of bias for all methodological parameters assessed. The majority of randomised controlled trials included participants who were already able to sit‐to‐stand or walk independently.

Only one study (48 participants), which we judged to be at high risk of bias, reported our primary outcome of interest, ability to sit‐to‐stand independently, and found that training increased the odds of achieving independent sit‐to‐stand compared with control (odds ratio (OR) 4.86, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.43 to 16.50, very low quality evidence).

Interventions or training for sit‐to‐stand improved the time taken to sit‐to‐stand and the lateral symmetry (weight distribution between the legs) during sit‐to‐stand (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.34; 95% CI ‐0.62 to ‐0.06, seven studies, 335 participants; and SMD 0.85; 95% CI 0.38 to 1.33, five studies, 105 participants respectively, both moderate quality evidence). These improvements are maintained at long‐term follow‐up.

Few trials assessing the effect of sit‐to‐stand training on peak vertical ground reaction force (one study, 54 participants) and functional ability (two studies, 196 participants) were identified, providing very low and low quality evidence respectively.

The effect of sit‐to‐stand training on number of falls was imprecise, demonstrating no benefit or harm (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.22, five studies, 319 participants, low quality evidence). We judged the majority of studies that assessed falls to be at high risk of bias.

Authors' conclusions

This review has found insufficient evidence relating to our primary outcome of ability to sit‐to‐stand independently to reach any generalisable conclusions. This review has found moderate quality evidence that interventions to improve sit‐to‐stand may have a beneficial effect on time taken to sit‐to‐stand and lateral symmetry during sit‐to‐stand, in the population of people with stroke who were already able to sit‐to‐stand independently. There was insufficient evidence to reach conclusions relating to the effect of interventions to improve sit‐to‐stand on peak vertical ground reaction force, functional ability and falls. This review adds to a growing body of evidence that repetitive task‐specific training is beneficial for outcomes in people receiving rehabilitation following stroke.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Stroke Rehabilitation, Movement, Movement/physiology, Postural Balance, Postural Balance/physiology, Posture, Posture/physiology, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Time Factors

Plain language summary

Interventions for improving the ability to rise to stand from sitting following stroke

Question

We wanted to assess the effectiveness of training, exercises or other interventions aimed at helping people who have had a stroke stand up independently from a sitting position, compared with usual care or no intervention.

Background

Rising to stand from sitting is one of the most frequently performed tasks of daily living and is something people need to be able to do to start walking. After a stroke, people may have difficulty rising to stand from sitting. This review looked at the effect of training or exercises on ability to rise to stand, and also aimed to look at the effect of different chair positions that might help people rise to stand.

Study characteristics

We identified 13 studies up to June 2013. These studies included 603 participants who had had a stroke. Twelve of the studies investigated the effect of different types of training or exercise: six studies (276 participants) investigated repetitive sit‐to‐stand training, four studies (264 participants) investigated an exercise training programme that included sit‐to‐stand training, one study (12 participants) included a training programme (sitting training) aiming to improve sit‐to‐stand, and one study (42 participants) investigated feedback (information about the symmetry of weight taken through the feet) during sit‐to‐stand. One of the studies investigated the effect of starting posture for sit‐to‐stand: this study (nine participants) compared sit‐to‐stand with a cane and without a cane. This study measured people during three tests of rising to stand with a cane, and three tests of rising to stand without a cane; there was no training period.

Key results

Combining the results of these studies provides us with evidence that training or exercises aiming to improve sit‐to‐stand performance have beneficial effects compared with usual care, no treatment or an alternative intervention: people who participated in training or exercises got faster at rising to stand and increased the amount of weight that they took through the leg affected by the stroke. There was also some evidence that these beneficial effects were still present several months after the end of training. Sit‐to‐stand training did not seem to affect the number of falls that people had, although the evidence was of poor quality. There was not enough evidence to say what the ideal amount of training or exercise was, but the results do suggest that training three times a week for two to three weeks may be enough to have a beneficial effect. We did not find any evidence of effects on outcomes other than time to sit‐to‐stand or the weight through the affected leg, or any evidence that the length of the training programme or the time since the participants had their stroke made any difference to outcomes. The studies that we found mainly included people who were able to walk and sit‐to‐stand independently at the start of the study, so these results are only relevant to this group of people. In other words, these results are not relevant to people who are unable to sit‐to‐stand independently and further research is needed to investigate the effect of sit‐to‐stand training for these people. The available studies suggest that effective interventions can either be specific repetitive training of sit‐to‐stand or exercise programmes that include repetitive sit‐to‐stand. The evidence is insufficient to reach conclusions relating to the duration or intensity of training.

Quality of the evidence

We found insufficient evidence relating to our primary outcome of ability to sit‐to‐stand independently to reach any generalisable conclusions. However, we found moderate quality evidence, from a relatively low number of small studies, that interventions to improve sit‐to‐stand may have a beneficial effect on the speed of rising to stand and the weight taken through the affected leg. We found insufficient evidence to reach any conclusions about the effect of sit‐to‐stand training on other outcomes. We recommend large clinical trials to confirm the results of this review, and to investigate the effects of different numbers of repetitions and durations of therapy. Future studies should include a measure of functional ability, and should measure long‐term outcomes as well as outcomes straight after therapy.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Any intervention compared with control for improving sit‐to‐stand ability following stroke | ||||

|

Patient or population: people with stroke Intervention: any therapy intervention or training for sit‐to‐stand Comparison: control intervention, usual care or no treatment | ||||

| Outcomes | Treatment effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Ability to sit‐to‐stand independently | OR 4.86 (95% CI 1.43 to 16.50) | 48 participants (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | 1 small study, judged to be at high risk of bias |

|

Time (to sit‐to‐stand) |

SMD ‐0.34 (95% CI ‐0.62 to ‐0.06) (favours intervention) |

346 participants (7 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | Sensitivity analyses found no difference in direction of effect Significant result maintained at follow‐up (149 participants; 4 studies; SMD ‐0.45 (95% CI ‐0.78 to ‐0.12)) |

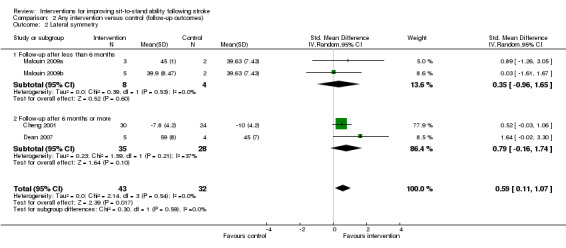

| Lateral symmetry | SMD 0.85 (95% CI 0.38 to 1.33) (favours intervention) |

105 participants (5 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | Sensitivity analyses found no difference in direction of effect Significant result maintained at follow‐up (75 participants; 3 studies; SMD 0.59 (95% CI 0.11 to 1.07)) |

| Peak vertical ground reaction force | SMD ‐0.02 (95% CI ‐0.55 to 0.52) | 54 participants (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | 1 small study, with poor reporting of methodological criteria |

| Falls (number of participants falling) | OR 0.75 (95% CI 0.46 to 1.22) | 319 participants (5 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | Methodological limitations with 3 of the 5 studies |

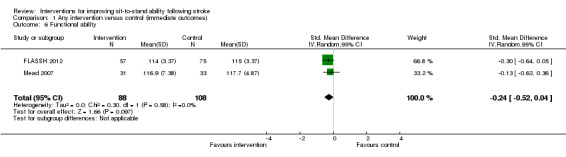

| Functional ability | SMD ‐0.24 (95% CI ‐0.52 to 0.04) | 196 participants (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | 2 studies, judged to be at low risk of bias, demonstrating consistent results |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||

CI: confidence interval OR: odds ratio SMD: standardised mean difference

Background

Standing up from a seated position is one of the most frequently performed functional tasks, and it is an essential pre‐requisite to walking (Alexander 2000). The ability to stand up without assistance is important for independent living (Alexander 2000), and preventing falls (Cheng 2001).

After a stroke, individuals can experience a number of problems relating to the ability to sit‐to‐stand independently. Rehabilitation of the sit‐to‐stand movement is therefore an important goal after stroke. To facilitate and promote evidence‐based practice it is necessary to know the evidence of effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving the ability to sit‐to‐stand after stroke.

Description of the condition

The inability to sit‐to‐stand independently can prevent independent function during activities of daily living. It is common for people with hemiplegia to demonstrate considerable asymmetry of weight distribution during rising to stand, with significantly increased weight‐bearing on the unaffected side (Cheng 1998; Durward 1994; Engardt 1992). People who have had a stroke also commonly exhibit a reduced peak vertical reaction force, an increased time to complete the movement of rising to stand and a larger medio‐lateral centre of pressure displacement compared with healthy adults (Cheng 1998).

Description of the intervention

Interventions aimed specifically at improving ability to sit‐to‐stand independently include:

a range of rehabilitation interventions, such as repetitive practice of sit‐to‐stand, and of the components required for movement from sitting to standing: muscle strength training and provision of feedback;

a range of interventions that alter the movement of rising to stand, such as changing the chair height, chair design or starting posture of the movement.

How the intervention might work

These interventions may work by restoration of impairments (e.g. improved muscle strength, motor learning), compensation for impairments (e.g. increased chair height) or substitution for impairments (e.g. provision of arm rests to aid sit‐to‐stand using arms).

Why it is important to do this review

A recent Cochrane review of repetitive task training after stroke investigated the effect of repetitive task training on measures of sit‐to‐stand; seven trials were included and a significant effect of repetitive task training was found (standardised effect 0.39, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 0.18 to 0.61) (French 2007). This review provides convincing evidence that repetitive practice may be beneficial for sit‐to‐stand. Our review differs substantially from the repetitive task training review, which focuses on a specific treatment (repetitive training). Our proposed review focuses on a specific outcome (sit‐to‐stand ability) and will include any treatments providing that improving ability to sit‐to‐stand was a goal of the treatment. This potentially includes a wide range of different treatments such as altering chair height or design; changing the starting posture for the movement; muscle strengthening; or providing feedback during training. As stated previously, sit‐to‐stand is essential for function, and important for walking and safe independent living; synthesis of the evidence relating to interventions to improve sit‐to‐stand ability is therefore important. We are unaware of any previous systematic reviews focusing specifically on this topic.

Objectives

To review the evidence of effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving sit‐to‐stand ability after stroke. The primary objectives were to determine (1) the effect of interventions that alter the starting posture (including chair height, foot position, hand rests) on ability to sit‐to‐stand independently; and (2) the effect of rehabilitation interventions (such as repetitive practice and exercise programmes) on ability to sit‐to‐stand independently. The secondary objectives were to determine the effects of interventions aimed at improving ability to sit‐to‐stand on: (1) time taken to sit‐to‐stand; (2) symmetry of weight distribution during sit‐to‐stand; (3) peak vertical ground reaction forces during sit‐to‐stand; (4) lateral movement of centre of pressure during sit‐to‐stand; and (5) incidence of falls.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included controlled trials where participants were randomly assigned. We planned to include the first phase of cross‐over studies where the order of assignment was determined randomly. We included trials with or without blinding of participants, treating therapist(s) and assessor(s). We documented and explored these parameters within the review.

Types of participants

We included trials enrolling adult participants (aged over 18 years) with a clinical diagnosis of stroke (World Health Organization definition, Hatano 1976), which could be either ischaemic or haemorrhagic in origin (with confirmation of the clinical diagnosis using imaging not compulsory).

Types of interventions

We included any interventions that:

aimed to affect the ability to sit‐to‐stand by altering the posture of the patient, or the design of the chair; or

stated that the aim of the intervention was to improve the ability to sit‐to‐stand; or

involved an exercise intervention that included repeated practice of the movement of sit‐to‐stand (task‐specific practice of rising to stand).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was defined as the ability to sit‐to‐stand independently.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were outcomes relating to sit‐to‐stand movement:

time taken to sit‐to‐stand (or sit‐to‐walk);

measures of lateral symmetry during sit‐to‐stand; including weight distribution, lateral movement of centre of pressure during sit‐to‐stand;

peak vertical ground reaction forces during sit‐to‐stand;

joint kinematics; including range of movement at the hip, knee or ankle.

Additional outcomes:

incidence of falls;

general functional ability scores (e.g. Barthel Index).

We documented when outcomes were recorded in relation to the end of the intervention period.

Search methods for identification of studies

See the 'Specialized register' section in the Cochrane Stroke Group module. We searched for relevant trials in all languages and planned to arrange translation of trial reports published in languages other than English.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (June 2013), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2013, Issue 5) (Appendix 1), MEDLINE (Ovid) (1950 to June 2013) (Appendix 2), EMBASE (Ovid) (1980 to June 2013) (Appendix 3), CINAHL (EBSCO) (1982 to June 2013) (Appendix 4) and AMED (Ovid) (1985 to June 2013) (Appendix 5).

We also searched the following databases and trials registries (June 2013):

British Nursing Index (Ovid) (from 1993) (Appendix 6);

REHABDATA (http://www.naric.com/?q=en/REHABDATA)(Appendix 7);

OTseeker (http://www.otseeker.com/) (Appendix 8);

Physiotherapy Evidence database (PEDro, http://www.pedro.fhs.usyd.edu.au/index.html), Chartered Society of Physiotherapy Research Database (Appendix 9);

OT Search (http://www1.aota.org/otsearch/index.asp);

Dissertation abstracts (http://wwwlib.umi.com/dissertations/search);

ClinicalTrials.gov (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/);

National Research Register (https://portal.nihr.ac.uk/Pages/NRRArchiveSearch.aspx);

UK Clinical Research Network Portfolio Database (http://public.ukcrn.org.uk/search/);

Current Controlled Trials (http://www.controlled‐trials.com/) (which also includes the UK Clinical Trials Gateway);

EU Clinical Trials Register (https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu);

Stroke Trials Registry (www.strokecenter.org/trials/);

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/).

We developed search strategies in consultation with the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator to avoid duplication of effort.

Searching other resources

In an effort to identify further published, unpublished and ongoing trials, we:

checked reference lists of all relevant articles;

contacted investigators known to be involved in research in this area;

used Science Citation Index cited reference search for forward tracking of important papers.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One review author (AP or CG) read the titles and abstracts of the identified references and eliminated any obviously irrelevant studies. We obtained the full text of the remaining studies and then, based on the inclusion criteria (types of studies, types of participants, aims of interventions, outcome measures), two review authors (AP, CG or BD) independently ranked these as 'include' or 'exclude'. We included studies classified as 'include' by both review authors at this stage and excluded trials classified as 'exclude' by both review authors. If there was disagreement between review authors, or a decision could not be reached, we reached consensus through discussion, including a third review author where necessary.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (AP, CG or BD) independently extracted data from the studies using a standard data extraction form. We attempted to obtain any missing data by contacting trial authors. Where possible we documented:

participant details (including age, gender, place of residence, type of stroke, time since stroke, initial functional ability, co‐morbid conditions, pre‐morbid disability);

the inclusion and exclusion criteria;

a brief description of the intervention (we classified the intervention using the three groups defined in Types of interventions and documented details including, where relevant, the nature of the intervention, duration/intensity/frequency of the intervention, details of the chair, involvement of treating therapist and qualifications and experience of treating therapist(s));

the comparison intervention;

the outcomes.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (AP, CG or BD) independently assessed the risk of bias by answering the following questions for each included study, and documenting this information using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011).

Was random sequence generation adequate?

We considered studies to have low risk of bias in relation to random sequence generation if the study described an adequate random component in the sequence generation process. Adequate methods for random sequence generation included random number tables, computer random number generators, coin tossing, shuffling cards or envelopes, throwing dice, drawing lots and randomised minimisation. Studies judged to be at high risk of bias included those where a non‐random component was described in the sequence generation process. Inadequate methods of random sequence generation included methods that were systematic such as dates or hospital/clinic numbers and methods that involved judgement or non‐random categorisation, such as preference of patient or availability of the intervention. If there was insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement of 'low risk' or 'high risk' we documented this as unclear.

Was allocation adequately concealed?

Studies with adequate concealment include those that have used central randomisation at a site remote from the study; computerised allocation, in which records are in a locked readable file that can be accessed only after entering patient details; and the drawing of opaque envelopes. Studies with inadequate concealment include those using an open list or table of random numbers, open computer systems or drawing of non‐opaque envelopes. Studies with unclear concealment will include those with no or inadequate information in the report.

Was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately concealed from the outcome assessor?

We considered studies adequately concealed if the outcome assessor was masked and the report did not identify any unmasking. We considered studies inadequately concealed if the outcome assessor was not masked or where the report clearly identified that unmasking occurred during the study. We documented concealment as unclear if a study did not state whether or not an outcome assessor was masked or there was insufficient information to judge.

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?

Studies adequately addressing incomplete outcome data have no missing outcome data, missing outcome data that were unlikely to be related to true outcome, missing outcome data that were balanced in numbers across intervention groups with similar reasons for missing data across groups, a reported effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes that was insufficient to have clinical relevance to observed effect size, or missing data that had been imputed using appropriate methods. Studies inadequately addressing incomplete outcome data either have missing outcome data that were likely to be related to true outcome with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups, a reported effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size, or as‐treated analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation. We documented the addressing of incomplete outcome data as unclear if there was insufficient reporting to allow assessment, or if this was not addressed in the report.

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias?

We assessed whether studies had any other important risk of bias such as a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used, an extreme baseline imbalance, a claim to have been fraudulent or some other problem. As we found it difficult to ever be certain, due to potential poor reporting, whether a study was free of any other problems that put it at a high risk of bias, we decided that it was unhelpful to class studies as 'low risk' of bias due to other factors (as this would more likely be as a consequence of poor reporting than of genuine confidence that the study was at low risk of bias). Therefore, we did not include the assessment of whether studies were free of other problems in the 'Risk of bias' tables or summary figures, but we documented relevant information in the notes section for each study.

We produced a 'Risk of bias' summary figure to illustrate the potential biases within each of the included studies.

We resolved any disagreements through discussion, including a third review author if necessary. We attempted to contact study authors for clarification and to obtain missing data when required.

Measures of treatment effect

For each comparison, we used the study results for ability to sit‐to‐stand independently, measures of sit‐to‐stand ability, incidence of falls and general functional ability, if documented. We used RevMan 5.2 for all analyses (RevMan 2012).

Unit of analysis issues

We analysed outcomes providing dichotomous data using the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) employing a random‐effects model with exploration of sources of heterogeneity. We analysed continuous outcomes as mean differences (MD) where the same scales were used, and standardised mean differences (SMD) where different studies reported different scales, with 95% CI. We treated activities of daily living data, such as the Barthel Index, as continuous outcomes and recorded mean and standard deviation data.

Dealing with missing data

If an included study did not report a particular outcome, we planned not to include that study in the analysis of that outcome. If an included study had missing data (e.g. reported means but not standard deviations for the follow‐up data) we contacted the study authors requesting the required data. If the data were unavailable, we planned to take logical steps to enter an assumed value. Such steps may have included estimating a standard deviation based on a reported standard error, or estimating a follow‐up standard deviation based on a baseline value. We planned to perform sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of entering assumed values.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We subjected all results to a random‐effects meta‐analysis to take account of statistical heterogeneity. We determined heterogeneity using the I2 statistic (I2 greater than 50% was considered substantial heterogeneity). If heterogeneity was found to be present, we planned to explore and present possible causes.

Assessment of reporting biases

We attempted to avoid reporting biases by using a comprehensive search strategy that included searching for unpublished studies and searching trials registers.

Data synthesis

We planned to synthesise the data from the included studies within two key comparisons.

Therapy interventions and training for sit‐to‐stand versus control or no intervention

We anticipated that this comparison might include data from studies comparing:

augmented feedback interventions for sit‐to‐stand versus control or no augmented feedback;

muscle strengthening exercise/programme for sit‐to‐stand versus control or no intervention;

exercise/balance training programme aimed at improving sit‐to‐stand versus control or no intervention;

joint mobilisations for sit‐to‐stand versus control or no intervention;

task‐specific practice of sit‐to‐stand versus control or no interventions.

Altered chair design or starting posture for sit‐to‐stand versus control or no intervention

We anticipated that this comparison might include data from studies comparing:

sit‐to‐stand from higher chair versus sit‐to‐stand from lower chair;

sit‐to‐stand using arm rests versus sit‐to‐stand without arm rests;

sit‐to‐stand from 'natural' starting position versus sit‐to‐stand from 'prescribed' starting position;

sit‐to‐stand from one 'prescribed' starting position versus sit‐to‐stand from another 'prescribed' starting position;

sit‐to‐stand with eyes open versus sit‐to‐stand with eyes closed;

sit‐to‐stand with shoes off versus sit‐to‐stand with shoes on.

However, we found no studies suitable for inclusion within meta‐analyses that investigated the effect of altered chair design or starting posture, and have therefore been unable to carry out this comparison.

We documented and reported information relating to usual care, including any treatment provided to participants in this group and the amount/intensity and duration of interventions.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If there were sufficient data (pre‐stated as five or more studies within a comparison), we planned to carry out subgroup analyses to explore types of stroke (ischaemic versus haemorrhagic), time since onset of stroke (less than six months post‐stroke versus more than six months post‐stroke), initial dependency (Barthel score less than 15 or equivalent versus Barthel score of more than 15), and age (less than 75 years versus more than 75 years). Sufficient data were available to enable us to carry out a subgroup analysis to explore time since onset of stroke. In addition, we carried out subgroup analyses to explore the type of intervention and the duration/intensity of the intervention.

Sensitivity analysis

We completed sensitivity analyses based on the methodological quality of studies (method of randomisation, blinding of outcome assessor, intention‐to‐treat analysis, type of study). We carried out sensitivity analysis only if there were five or more studies within a comparison.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Our search strategy identified 2255 titles and after the initial screening of titles and abstracts by one author (AP or CG) we eliminated 2157 irrelevant papers. We obtained the full text of the remaining 98 papers and after further assessment 66 studies did not meet the selection criteria and so we excluded them.

There was insufficient information to reach a decision about the inclusion of 18 additional studies (Atchison 1995; Camargos 2009; Chumbler 2011; Dean 2006; FFF 2010; Finestone 2012; Fraser 2012; Guttman 2011; Guttman 2012; Hirano 2010; Kerr 2012; Korner‐Bitensky 2013; Lecours 2008; Moore 2012; Rodrigues‐De‐Paula 2010; Rose 2009; Zhong 2006; Zhu 2006), and attempts to contact the authors of these studies are ongoing (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). We also identified one ongoing trial that appears to be relevant for inclusion (ACTIV 2012) (see Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Thus we identified a total of 13 studies for inclusion in this review. (See Figure 1 for a summary flow diagram).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Thirteen studies (603 participants) met the inclusion criteria for this review (Barreca 2004; Barreca 2007; Blennerhassett 2004; Britton 2008; Cheng 2001; Dean 2000; Dean 2007; Engardt 1993; FLASSH 2012; Hu 2013; Malouin 2009; Mead 2007; Tung 2010).

Interventions studied

Twelve of the 13 included studies investigated a type of therapy intervention or training for sit‐to‐stand. These included:

six studies (276 participants) that investigated repetitive sit‐to‐stand training (Barreca 2004; Barreca 2007; Britton 2008; Cheng 2001; Malouin 2009; Tung 2010);

four studies (264 participants) that investigated an exercise training programme, which included sit‐to‐stand training (Blennerhassett 2004; Dean 2000; FLASSH 2012; Mead 2007);

one study (12 participants) that included a training programme (sitting training) aimed to improve sit‐to‐stand (Dean 2007); and

one study (42 participants) that investigated augmented feedback during sit‐to‐stand (Engardt 1993).

One of the included studies, with nine participants, investigated the effect of altered chair design or starting posture for sit‐to‐stand. This was a study comparing sit‐to‐stand with a cane and without a cane (Hu 2013).

Malouin 2009 included two repetitive sit‐to‐stand training intervention groups; one intervention combined repetitive sit‐to‐stand with cognitive training and the other intervention combined repetitive sit‐to‐stand with mental practice. We have included both of these intervention groups in our analyses, with the intervention including cognitive training entered as Malouin 2009a and the intervention including mental practice entered as Malouin 2009b. (Data from the control group were 'shared' between these 'studies', with half the number of control group participants allocated to each 'study').

Cheng 2001 provided both visual and auditory feedback as part of the repetitive sit‐to‐stand training. However, this study was comparing the intervention with a control group that was not doing repetitive sit‐to‐stand training; hence we agreed that this was an investigation of the effectiveness of a repetitive sit‐to‐stand training regime, and not an investigation of the effect of feedback.

FLASSH 2012 investigated an intervention programme that was specifically targeted at the reduction of falls in participants at high risk of falling. The exercise component of the multifactorial falls prevention programme might have included practice of sit‐to‐stand; however, the intervention was individually tailored, and not all participants would have completed practice of sit‐to‐stand. We planned to explore the effect of including this study in a sensitivity analysis.

Intensity and duration of interventions

Most of the intervention periods lasted between 30 and 60 minutes each day delivered either three times per week (Barreca 2004; Barreca 2007; Dean 2000; Malouin 2009; Mead 2007; Tung 2010), or five times per week (Blennerhassett 2004; Britton 2008; Cheng 2001; Dean 2007), or between three and five times per week (FLASSH 2012). The exception was Engardt 1993, where the intervention lasted just 15 minutes, but was delivered three times each day (five days a week).

The study duration was either two weeks (Britton 2008; Dean 2007), three weeks (Cheng 2001), four weeks (Blennerhassett 2004; Dean 2000; Malouin 2009; Tung 2010), six weeks (Engardt 1993), or 12 weeks (Barreca 2007, Mead 2007). Barreca 2004 continued to deliver the intervention for the duration of the time that the participant was an in‐patient. In FLASSH 2012, participants were given a home exercise programme, and adherence was measured for 12 months.

Hu 2013 was a repeated‐measure design with no intervention period. Participants completed three trials of sit‐to‐stand in each of the two conditions, in a randomised order.

Included participants

Sample sizes in the included studies were generally low, ranging from 12 or fewer (Dean 2000; Dean 2007; Hu 2013; Malouin 2009), to 66 (Mead 2007), and 156 (FLASSH 2012).

Five of the studies included participants who were on average between 30 and 51 days post‐stroke (Barreca 2004; Blennerhassett 2004; Britton 2008; Dean 2007; Engardt 1993); three studies included participants who were on average between 2.8 and 8 months post‐stroke (Cheng 2001; FLASSH 2012; Hu 2013; Mead 2007); and three studies included participants who were on average more than one year post‐stroke (Dean 2000; Malouin 2009; Tung 2010). Time after stroke is not stated for Barreca 2007.

Six of the studies only included participants who were already able to sit‐to‐stand independently (Britton 2008; Cheng 2001; Engardt 1993; Hu 2013; Malouin 2009; Tung 2010), and three required ability to walk independently (Blennerhassett 2004; Dean 2000; Mead 2007). In contrast Dean 2007 and Barreca 2004 included participants who had independent sitting balance (assessed using the sitting balance item of the Motor Assessment Scale for Stroke and the Postural Control item of the Chedoke McMaster Stroke Assessment respectively), but were not required to be able to sit‐to‐stand or walk independently. Barreca 2004 and Barreca 2007 excluded participants who were already able to sit‐to‐stand independently. This information was not provided for FLASSH 2012.

Outcome measures

Barreca 2004 measured outcome either at the time of discharge from hospital, or when a participant was first able to sit‐to‐stand independently. Eleven of the included studies all measured outcomes immediately after the end of the intervention. Seven of these studies also included a follow‐up measure; this was at three weeks (Malouin 2009), two months (Dean 2000), six to seven months (Blennerhassett 2004; Cheng 2001; Dean 2007; Mead 2007), and 33 months (Engardt 1993). In FLASSH 2012 outcome was assessed 12 months after the implementation of the intervention programme.

Primary outcomes

Only two studies assessed our primary outcome of the ability to sit‐to‐stand independently (Barreca 2004, Barreca 2007). In the majority of the other studies (all except Dean 2007), all participants were able to sit‐to‐stand independently prior to recruitment, meaning that this outcome was not appropriate as a measure of effect.

Secondary outcomes

Nine studies included a measure of time (time taken to sit‐to‐stand: Britton 2008; Cheng 2001; Engardt 1993; Hu 2013; Mead 2007; Tung 2010; time taken to sit‐to‐walk: Blennerhassett 2004; Dean 2000; number of sit‐to‐stand repetitions in 30 seconds: FLASSH 2012). Data from FLASSH 2012 were multiplied by ‐1 as the measurement of number of sit‐to‐stand repetitions has a direction opposite to the measurement of time (i.e. decreased time is beneficial; increased number of repetitions is beneficial).

Seven studies included a measure of lateral symmetry during sit‐to‐stand; including symmetry of weight distribution (Britton 2008; Dean 2000; Dean 2007; Engardt 1993; Hu 2013; Malouin 2009), and lateral movement of centre of pressure during sit‐to‐stand (Cheng 2001).

One study included a measure of peak vertical ground reaction forces during sit‐to‐stand (Cheng 2001).

One study included a measure of the maximum anterior‐posterior (A‐P) movement of centre of pressure during sit‐to‐stand (Cheng 2001).

Additional outcomes

Five studies reported the incidence of falls (Barreca 2004; Cheng 2001; Dean 2007; FLASSH 2012; Mead 2007). However, Dean 2007 only reported falls as an adverse event, rather than having a falls as a planned outcome measure.

Two studies reported general functional ability, using the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) (FLASSH 2012; Mead 2007).

Data used in analyses within this review

Barreca 2007 is only reported as an abstract, and does not present data suitable for inclusion within the analyses in this review. We have attempted to contact the author of this study and will include these data in future updates of this review if we are able to obtain them. Hu 2013 is a repeated‐measures, randomised, cross‐over study and no data are available for before the cross‐over, and therefore no data from this study are included within analyses.

Thus, data from 11 studies are included within this review (Barreca 2004; Blennerhassett 2004; Britton 2008; Cheng 2001; Dean 2000; Dean 2007; Engardt 1993; FLASSH 2012; Malouin 2009; Mead 2007; Tung 2010).

All analyses within this review have been carried out using outcomes measured immediately after the end of the intervention. The exceptions for this are Cheng 2001, where only follow‐up (six‐month) data were reported and FLASSH 2012, where data were only recorded at 12 months; we have pooled these follow‐up data with the data from immediately after the end of the intervention for other studies (making the assumption that the follow‐up data will be a conservative estimate of the data at the immediate end of the intervention), but have explored the effect of doing this using sensitivity analyses.

Cheng 2001 was the only study to include data for outcomes of peak vertical ground reaction force and anterior‐posterior centre of pressure displacement. These data have been included within analyses in the comparison of intervention versus control (immediate outcomes). However, as noted above, these data actually pertain to six‐month follow‐up data.

Four studies reported follow‐up data for a measure of time (Blennerhassett 2004; Cheng 2001; Dean 2000; Mead 2007), and three reported follow‐up data for a measure of lateral symmetry (Cheng 2001; Dean 2000; Malouin 2009), but data were only available for a maximum of one study for the other outcome measures. We have therefore pooled follow‐up data for the outcomes of time and lateral symmetry only. (Note: the data for Cheng 2001 are the same data as used in the analysis of immediate outcomes.)

As FLASSH 2012 investigated a falls prevention programme that may, or may not, have incorporated sit‐to‐stand exercise for individual participants, we planned to explore the effect of including this study with sensitivity analysis.

FLASSH 2012 reported median values, inter‐quartile ranges and P values for the differences between groups. The P values were used to estimate a standard deviation for both groups, and the median values were entered in place of mean values. We had already planned to remove this study in a sensitivity analysis due to the study design (see above), so no further sensitivity analysis was planned to explore the use of these estimated data values.

Excluded studies

After two independent review authors assessed the full text of 98 papers, we excluded 66 of these studies. For 34 of these 66 excluded studies it was necessary to look at the full paper to determine whether repetitive sit‐to‐stand training was incorporated into another type of exercise or training intervention as insufficient details were provided in the abstract. Reasons for exclusion of the remaining 32 are listed in Characteristics of excluded studies; these studies either specifically investigate sit‐to‐stand or are focused on an intervention that the review authors considered was highly likely to involve sit‐to‐stand training. We identified several studies that investigated interventions that were of relevance to this review, often using a cross‐over design, but the order of delivery of different conditions was not truly randomised. This excluded all the studies that we had identified investigating the effect of altered chair design or starting posture for sit‐to‐stand (e.g. Bjerlemo 2002; Brunt 2002; Roy 2006).

We had insufficient information to reach decisions about the inclusion or exclusion for a further 18 studies (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification) and we identified one ongoing trial (ACTIV 2012).

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 2 for a summary of the risk of bias in included studies. We judged four studies to be at low risk of bias for all methodological parameters assessed (Blennerhassett 2004; Dean 2007; FLASSH 2012; Tung 2010).

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

We judged five of the studies to be at high risk of bias for one or more methodological criteria. We assessed Barreca 2004 to be at high risk of bias for several methodological parameters, while we assessed the four other studies to be at high risk of bias for one methodological parameter: Britton 2008 failed to have a blinded outcome assessor, we considered Dean 2000 and Hu 2013 to have inadequate allocation concealment and we considered Engardt 1993 to have dealt with incomplete data inappropriately. In addition, we noted that Britton 2008 and Tung 2010 had unbalanced demographic variables between treatment groups. We also noted that the instruction to participants in Dean 2000 to sit‐to‐stand with equal weight distribution during baseline and post‐intervention assessment might introduce some bias into the measurement of weight‐bearing symmetry compared with studies where this instruction was not given.

There were insufficient details to be certain of the risk of bias for several parameters for Barreca 2007, Cheng 2001 and Engardt 1993, and for allocation concealment for Malouin 2009 and Mead 2007.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

1. Any therapy intervention or training for sit‐to‐stand versus control: immediate effect of intervention

We included 10 studies in this comparison: five studies (164 participants) that investigated repetitive sit‐to‐stand training (Barreca 2004; Britton 2008; Cheng 2001; Malouin 2009; Tung 2010), four studies (264 participants) that investigated an exercise training programme that included sit‐to‐stand training (Blennerhassett 2004; Dean 2000; FLASSH 2012; Mead 2007), and one study (12 participants) that included a training programme (sitting training) aiming to improve sit‐to‐stand (Dean 2007).

1.1 Ability to sit‐to‐stand independently

Only one small study, judged to be at high risk of bias, assessed our primary outcome of ability to sit‐to‐stand independently (Barreca 2004, 48 participants). This study demonstrated a statistically significant effect of the intervention when compared with control (odds ratio (OR) 4.86, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.43 to 16.50) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any intervention versus control (immediate outcomes), Outcome 1 Ability to sit‐to‐stand independently.

1.2 Time taken to sit‐to‐stand (or sit‐to‐walk)

Seven studies (335 participants) measured the time to sit‐to‐stand (Britton 2008; Cheng 2001; Mead 2007; Tung 2010), or sit‐to‐walk (Blennerhassett 2004; Dean 2000), or number of sit‐to‐stands in a specified time (FLASSH 2012), and demonstrated a statistically significant effect of intervention when compared with control (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.34, 95% CI ‐0.62 to ‐0.06) with low heterogeneity (I² = 29%) (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any intervention versus control (immediate outcomes), Outcome 2 Time.

Sensitivity analysis to remove FLASSH 2012, as not all participants may have done sit‐to‐stand training, demonstrated that there was a more significant effect (SMD ‐0.51, 95% CI ‐0.79 to ‐0.23) with no heterogeneity (I² = 0%). There was no significant difference between the subgroup of studies measuring sit‐to‐stand time and those measuring sit‐to‐walk time (P value = 0.75). Additional sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of removing Cheng 2001, as these data were follow‐up data and not from immediately after the end of the intervention, demonstrated no change in the direction of the effect (SMD ‐0.41, 95% CI ‐0.73 to ‐0.08).

1.3 Lateral symmetry

Five studies (105 participants) measured lateral symmetry by assessing either weight distribution (Britton 2008; Dean 2000; Dean 2007; Malouin 2009), or centre of pressure (Cheng 2001), and demonstrated a statistically significant effect of the intervention when compared with control (SMD 0.85, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.33) with little heterogeneity (I² = 10%). The test for subgroup differences suggested that there was little difference between the subgroup assessing weight distribution and the subgroup assessing centre of pressure (P value = 0.12) (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any intervention versus control (immediate outcomes), Outcome 3 Lateral symmetry.

Sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of removing Dean 2000, as this study gave participants specific instructions to sit‐to‐stand with symmetrical weight distribution, did not impact on the significance of the results (SMD 0.80, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.30). Sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of removing Cheng 2001, as these data were follow‐up data and not from immediately after the end of the intervention, demonstrated no change in the direction of the effect (SMD 1.19, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.84). However, removing Cheng 2001 from the analysis did reduce the heterogeneity from I² = 10% to I² = 0%.

1.4 Peak vertical ground reaction force

Only one study assessed peak vertical ground reaction force during sit‐to‐stand (Cheng 2001, 54 participants). This found no statistically significant effect of the intervention when compared with control (SMD ‐0.02, 95% CI ‐0.55 to 0.52) (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any intervention versus control (immediate outcomes), Outcome 4 Peak vertical ground reaction force.

1.5 Falls

Five studies (319 participants) reported the number of participants falling during the intervention period (Barreca 2004; Cheng 2001; Dean 2007; FLASSH 2012; Mead 2007). Analysis suggests that there is no significant effect of the intervention when compared with control (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.22). Removal of FLASSH 2012, as this study was specifically aimed at reduction of falls and included multifactorial falls prevention interventions, did not affect the direction of the result (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.72) (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any intervention versus control (immediate outcomes), Outcome 5 Falls (number of participants falling).

Additional sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of removing Barreca 2004, as this study was assessed to be at high risk of bias, and Dean 2007, as falls were reported as an adverse event rather than an outcome, did not affect the direction of the result (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.87).

1.6 Functional ability

Two studies (196 participants) reported functional ability at the end of the intervention (FLASSH 2012; Mead 2007). There was no statistically significant effect of the intervention when compared with control (SMD ‐0.24, 95% CI ‐0.52 to 0.04) (Analysis 1.6). Sensitivity analysis to remove FLASSH 2012 did not affect the result (SMD ‐0.13, 95% CI ‐0.62 to 0.36).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any intervention versus control (immediate outcomes), Outcome 6 Functional ability.

2. Any therapy intervention or training for sit‐to‐stand versus control: follow‐up effects

Due to availability of data we have pooled follow‐up data for the outcomes of time and lateral symmetry only.

2.1 Time taken to sit‐to‐stand (or sit‐to‐walk)

Four studies (149 participants) reported follow‐up data for a measure of time (Blennerhassett 2004; Cheng 2001; Dean 2000; Mead 2007), and demonstrated a statistically significant effect of the intervention when compared with control (SMD ‐0.45, 95% CI ‐0.78 to ‐0.12) with no heterogeneity (I² = 0%) (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Any intervention versus control (follow‐up outcomes), Outcome 1 Time.

2.2 Lateral symmetry

Three studies (75 participants) reported follow‐up data for a measure of lateral symmetry (Cheng 2001; Dean 2000; Malouin 2009), and demonstrated a statistically significant effect of the intervention when compared with control (SMD 0.59, 95% CI 0.11 to 1.07) with no heterogeneity (I² = 0%) (Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Any intervention versus control (follow‐up outcomes), Outcome 2 Lateral symmetry.

3. Subgroup analysis: type of intervention

Three different types of therapy intervention or training for sit‐to‐stand were included within the trials in Analysis 1. These interventions included repetitive sit‐to‐stand training (Barreca 2004; Britton 2008; Cheng 2001; Malouin 2009; Tung 2010), exercise training programmes that included sit‐to‐stand training (Blennerhassett 2004; Dean 2000; FLASSH 2012; Mead 2007), and a training programme (sitting training) aiming to improve sit‐to‐stand (Dean 2007). There were data available for more than five studies for the outcomes of 'Time' and 'Lateral symmetry'. We therefore carried out subgroup analyses to explore the effect of the type of intervention for these outcomes.

3.1 Time taken to sit‐to‐stand (or sit‐to‐walk)

Data were available from three studies investigating repetitive sit‐to‐stand (Britton 2008; Cheng 2001; Tung 2010), and four investigating exercise programmes (Blennerhassett 2004; Dean 2000; FLASSH 2012; Mead 2007). Subgroup analysis suggested that there were no significant differences between subgroups of different types of intervention in time taken to sit‐to‐stand (or sit‐to‐walk) (P value = 0.19). There remained no significant differences between subgroups when data from FLASSH 2012 were removed from the analysis (P value = 0.69) (Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis: type of intervention, Outcome 1 Time.

3.2 Lateral symmetry

Data were available from three studies investigating repetitive sit‐to‐stand (Britton 2008; Cheng 2001; Malouin 2009); one investigating an exercise programme (Dean 2000), and one investigating sitting training aiming to improve sit‐to‐stand (Dean 2007). Subgroup analysis indicated that there were no significant differences between subgroups of different types of interventions in lateral symmetry during sit‐to‐stand (P value = 0.11) (Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis: type of intervention, Outcome 2 Lateral symmetry.

4. Subgroup analyses: duration and intensity of intervention

We carried out subgroup analyses to explore the effect of interventions that were either delivered for a different number of weeks, or that were delivered for a different number of sessions per week, for the outcomes of 'Time' and 'Lateral symmetry'. These analyses indicated that there were no significant differences between subgroups for number of weeks or number of sessions per week for the outcome of 'Time' (P value = 0.68 and P value = 0.25 respectively) or 'Lateral symmetry' (P value = 0.81 and P value = 0.81 respectively). We did not include data from FLASSH 2012 in this subgroup analysis as the duration and intensity was dependent on adherence by the participant (Analysis 4.1; Analysis 4.2; Analysis 4.3; Analysis 4.4).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup analysis: duration and intensity of intervention, Outcome 1 Weeks of intervention: Time.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup analysis: duration and intensity of intervention, Outcome 2 Sessions per week: Time.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup analysis: duration and intensity of intervention, Outcome 3 Weeks of intervention: Lateral symmetry.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup analysis: duration and intensity of intervention, Outcome 4 Sessions per week: Lateral symmetry.

5. Subgroup analyses: time post‐stroke

We carried out subgroup analyses to explore the effect of including participants who were at different times post‐stroke. We divided these, according to the descriptions of participants provided within studies, into 30 to 51 days post‐stroke, 2.8 to 6 months post‐stroke or more than one year post‐stroke, and completed subgroup analyses for the outcomes of 'Time' and 'Lateral symmetry'. These analyses indicated that there were no significant differences between subgroups relating to time post‐stroke for the outcomes of 'Time' (P value = 0.86) or 'Lateral symmetry' (P value = 0.22) (Analysis 5.1; Analysis 5.2).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Subgroup analysis: time post‐stroke, Outcome 1 Time.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Subgroup analysis: time post‐stroke, Outcome 2 Lateral symmetry.

6. Feedback versus no feedback

One study (42 participants) investigated augmented feedback during sit‐to‐stand (Engardt 1993), comparing the effects of repetitive sit‐to‐stand training with auditory feedback of weight‐bearing symmetry with repetitive sit‐to‐stand training with no auditory feedback. Data were available for the outcomes of 'Time' and 'Lateral symmetry'; analyses demonstrated no significant benefit of the feedback (SMD ‐0.11, 95% CI ‐0.82 to 0.61 and SMD 0.53, 95% CI ‐0.20 to 1.26 respectively) (Analysis 6.1; Analysis 6.2).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Feedback versus no feedback, Outcome 1 Time.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Feedback versus no feedback, Outcome 2 Lateral symmetry.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We identified 13 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (603 participants) that investigated the effectiveness of interventions to improve sit‐to‐stand. Twelve of the studies compared a type of therapy intervention or training for sit‐to‐stand with a control intervention; one study investigated the effect of using a cane during sit‐to‐stand. We included data from 11 RCTs (482 participants) in meta‐analyses.

Only one of these studies (48 participants), which we judged to be at high risk of bias, reported our primary outcome of interest, ability to sit‐to‐stand independently, finding a significantly increased odds of achieving independent sit‐to‐stand in the intervention group. However, the majority of the RCTs (nine studies, 422 participants) included participants who were already able to sit‐to‐stand or walk independently, meaning that there is very little evidence relating to ability to achieve independent sit‐to‐stand. Rather, most evidence relates to improvements in sit‐to‐stand ability in people who are already independent.

Meta‐analyses revealed that immediately after therapy interventions or training for sit‐to‐stand the time taken to sit‐to‐stand and the lateral symmetry (weight distribution between the legs or centre of pressure displacement) during sit‐to‐stand is significantly improved. Subgroup analyses found no evidence of significant subgroup differences between groups with different types of intervention, duration or intensity of intervention or of time post‐stroke of included participants. Meta‐analyses of follow‐up data revealed that the immediate improvement in the time taken to sit‐to‐stand and the lateral symmetry (weight distribution between the legs) during sit‐to‐stand was maintained beyond the period of the intervention.

We found some limited evidence, from five RCTs, that the interventions did not have a significant effect on the number of falls. However, there were methodological issues with three of these RCTs, limiting the ability to generalise from this result. We identified very few trials that assessed the effect of sit‐to‐stand training on peak vertical ground reaction force (one study, 54 participants) and functional ability (two studies, 196 participants), providing very low and low quality evidence respectively in relation to these outcomes.

In summary, this review has found insufficient evidence relating to our primary outcome of ability to sit‐to‐stand independently to reach any generalisable conclusions. However, we found moderate quality evidence that interventions to improve sit‐to‐stand have a significantly beneficial effect on secondary outcomes of time taken to sit‐to‐stand and lateral symmetry during sit‐to‐stand, in the population of people with stroke who were already able to sit‐to‐stand independently, with some evidence that this effect is maintained long‐term.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The evidence that has been pooled within analyses relates only to the population of people with stroke who are able to either sit‐to‐stand or walk independently prior to the intervention. Thus this evidence is only applicable to improving ability in people with stroke who are able to sit‐to‐stand, and cannot be generalised to the population of people with stroke who are unable to sit‐to‐stand independently.

We primarily found RCTs investigating the effect of therapy interventions and training to improve sit‐to‐stand, and did not find any evidence relating to the effect of altered chair design and only one cross‐over study investigating starting posture (use of a cane) for sit‐to‐stand. This review is therefore unable to reach any conclusions relating to the effect of different chair designs or starting postures during training of, or performance of, sit‐to‐stand.

Although our analyses include a low number of small studies, the results of the studies are consistent and there was relatively low heterogeneity for the analyses relating to the outcomes of time and lateral symmetry, increasing our confidence in the generalisability of this evidence.

Quality of the evidence

The sample sizes in the included studies were generally very low, ranging from 12 to 156 participants. We judged only four of the included studies to be at low risk of bias for all methodological criteria assessed, and we judged five studies to be at high risk of bias for at least one methodological criterion assessed. We judged one study to be at high risk of bias for more than one methodological feature; however, this study did not contribute any data to the key analyses relating to time or lateral symmetry.

Potential biases in the review process

We included studies that investigated exercise programmes that included sit‐to‐stand. There is the possibility that we may have failed to identify all RCTs of exercise programmes that included sit‐to‐stand training. However, if the study included an outcome specific to sit‐to‐stand our search strategy ought to have been successful at identifying these studies. In some cases we identified RCTs of exercise programmes that did not explicitly state that the intervention was (or was not) aimed at improving sit‐to‐stand ability. As it is difficult to be certain about the absence of a statement, in these cases we therefore checked whether sit‐to‐stand had been assessed as an outcome. We excluded studies if there was no explicit statement of intent to improve sit‐to‐stand ability and there was no outcome related to sit‐to‐stand ability. Studies that we excluded on this basis are described in the Characteristics of excluded studies table as being excluded because "outcomes did not meet the criteria of this review".

We searched for studies that investigated the effect of altered chair design or starting posture for sit‐to‐stand. We found a number of studies that investigated sit‐to‐stand performance in people with stroke under a number of different conditions, including different chair heights and foot positions. Although some of these studies stated that there was some 'randomisation' of the order of different conditions, we judged that the order of the presentation of conditions was not truly randomised for all except one of these studies. It could be argued that one would not expect any carry‐over in levels of performance of sit‐to‐stand between different conditions, and that therefore a truly randomised order of allocation of conditions is not a necessary criterion to achieve low risk of bias within these studies. Consequently, it may be unrealistic to expect to identify any RCTs investigating the effect of altered chair design or starting posture for sit‐to‐stand, as best evidence relating to chair design or starting posture may come from repeated‐measures studies. We will need to consider whether, for future updates of this review, we continue to search for RCTs investigating chair design or starting posture within a single session.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

There is a growing body of evidence from systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of RCTs that effective rehabilitation components are high‐intensity, repetitive and task‐specific in nature (Langhorne 2009), and our review adds to this body of evidence. We are unaware of any previous systematic reviews focusing specifically on interventions to improve ability to sit‐to‐stand.

Our review is in agreement with a Cochrane review investigating the effect of repetitive task training to improve functional ability after stroke, which found a significant effect of repetitive task training on sit‐to‐stand outcomes (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.35, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.13 to 0.56) (French 2007). The French 2010 Cochrane review included eight studies that had some measure of sit‐to‐stand ability; our review only included three of these eight studies (Barreca 2004; Blennerhassett 2004; Dean 2000). We excluded the other five studies from our review because the intervention was not specifically aimed at improving sit‐to‐stand ability; one at the full paper stage (Dean 1997), and four at the title/abstract stage (Howe 2005; Langhammer 2000; Salbach 2004; van Vliet 2005). Our review identified four RCTs of repetitive sit‐to‐stand training that are not included in the French 2007 review; one study that does not appear to have been identified (Cheng 2001), and three that have been published after the date of the last search (Britton 2008; Malouin 2009; Tung 2010). Thus, our review is in agreement with the conclusions of the French 2007 review that repetitive training is beneficial for sit‐to‐stand. However, the advantages of our review are that our evidence is specific to interventions which are aimed at improving sit‐to‐stand, and that we have identified additional studies of repetitive sit‐to‐stand training.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The conclusions are limited by the low number of small studies included within this review. However, this review provides moderate quality evidence that therapy and training interventions that are specifically aimed at improving sit‐to‐stand may be effective at improving sit‐to‐stand time and performance (lateral symmetry), in people who are able to sit‐to‐stand independently after stroke, and that this effect may be sustained beyond the period of the intervention. This review thus adds to the body of evidence that repetitive task‐specific training is beneficial within stroke rehabilitation.

There is insufficient evidence to make any conclusions about the effect of sit‐to‐stand training on global measures of functional ability after stroke.

The available studies suggest that effective interventions can either be specific repetitive training of sit‐to‐stand or exercise programmes that include repetitive sit‐to‐stand. The evidence is insufficient to make conclusions relating to the duration or intensity of training.

Implications for research.

Further, appropriately powered, well‐designed randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of sit‐to‐stand training are essential to confirm the results of this review, which are currently based on a low number of very small studies. Current evidence demonstrates benefits associated with repetitive sit‐to‐stand training, and there is now a need for RCTs that clearly investigate the effect of different durations and intensities of training. Future RCTs should include a measure of global functional ability, and should include a follow‐up outcome measure as well as an outcome measured immediately after the end of the intervention. Studies that explore methods of augmenting repetitive sit‐to‐stand training (e.g. the addition of feedback) would be beneficial.

Studies to investigate the effect of sit‐to‐stand training on people unable to sit‐to‐stand independently are required, as there is currently a lack of evidence relating to this population. Systematic reviews of the non‐randomised evidence relating to the effect of seat design and starting posture are required, as this evidence potentially provides useful information relating to these issues.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2008 Review first published: Issue 5, 2014

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 22 March 2012 | New search has been performed | This protocol has been updated since the previous version was withdrawn from Issue 6, 2011 of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. It now conforms to the latest format for Cochrane reviews, and new authors have been added. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Brenda Thomas, Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator, for her assistance in developing the search strategy; Paola Durando for assisting with literature searches; and Gillian Mead and Susan Lewis for providing data relating to the Mead 2007 trial. We are very grateful to everyone who provided peer‐review on versions of this review; including Heather Goodare and another consumer reviewer who provided valuable comments.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) search strategy

#1 [mh ^"cerebrovascular disorders"] or [mh "basal ganglia cerebrovascular disease"] or [mh "brain ischemia"] or [mh "carotid artery diseases"] or [mh "intracranial arterial diseases"] or [mh "intracranial embolism and thrombosis"] or [mh "intracranial hemorrhages"] or [mh ^stroke] or [mh "brain infarction"] or [mh ^"stroke, lacunar"] or [mh ^"vasospasm, intracranial"] or [mh ^"vertebral artery dissection"] or [mh "brain injuries"] or [mh "brain injury, chronic"] #2 stroke or poststroke or "post‐stroke" or cerebrovasc* or brain next vasc* or cerebral next vasc* or cva* or apoplex* or SAH #3 (brain* or cerebr* or cerebell* or intracran* or intracerebral) near/5 (isch*emi* or infarct* or thrombo* or emboli* or occlus*) #4 (brain* or cerebr* or cerebell* or intracerebral or intracranial or subarachnoid) near/5 (haemorrhage* or hemorrhage* or haematoma* or hematoma* or bleed*) #5 [mh ^hemiplegia] or [mh paresis] #6 hemipleg* or hemipar* or paresis or paretic or brain next injur* #7 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 #8 "sit‐to‐stand" #9 (sit or sitting or rise or rising) near/5 (stand or standing) #10 stand* next up #11 (stand or standing or rise or rising or "getting up") near/10 (seat or seated or chair or sitting) #12 #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 #13 #7 and #12

Appendix 2. MEDLINE (Ovid) search strategy

1. cerebrovascular disorders/ or exp basal ganglia cerebrovascular disease/ or exp brain ischemia/ or exp carotid artery diseases/ or exp intracranial arterial diseases/ or exp "intracranial embolism and thrombosis"/ or exp intracranial hemorrhages/ or stroke/ or exp brain infarction/ or vasospasm, intracranial/ or vertebral artery dissection/ 2. (stroke or poststroke or post‐stroke or cerebrovasc$ or brain vasc$ or cerebral vasc$ or cva$ or apoplex$ or SAH).tw. 3. ((brain$ or cerebr$ or cerebell$ or intracran$ or intracerebral) adj5 (isch?emi$ or infarct$ or thrombo$ or emboli$ or occlus$)).tw. 4. ((brain$ or cerebr$ or cerebell$ or intracerebral or intracranial or subarachnoid) adj5 (haemorrhage$ or hemorrhage$ or haematoma$ or hematoma$ or bleed$)).tw. 5. hemiplegia/ or exp paresis/ 6. (hemipleg$ or hemipar$ or paresis or paretic).tw. 7. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 8. sit‐to‐stand.tw. 9. ((sit or sitting or rise or rising) adj5 (stand or standing)).tw. 10. ((stand or standing) adj up).tw. 11. ((stand or standing or rise or rising or getting up) adj10 (seat or seated or chair or sitting)).tw. 12. 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 13. 7 and 12

Appendix 3. EMBASE (Ovid) search strategy

1. cerebrovascular disease/ or basal ganglion hemorrhage/ or cerebral artery disease/ or cerebrovascular accident/ or stroke/ or exp carotid artery disease/ or exp brain hematoma/ or exp brain hemorrhage/ or exp brain ischemia/ or exp intracranial aneurysm/ or exp occlusive cerebrovascular disease/ 2. stroke patient/ or stroke unit/ 3. (stroke or poststroke or post‐stroke or cerebrovasc$ or brain vasc$ or cerebral vasc$ or cva$ or apoplex$ or SAH).tw. 4. ((brain$ or cerebr$ or cerebell$ or intracran$ or intracerebral) adj5 (isch?emi$ or infarct$ or thrombo$ or emboli$ or occlus$)).tw. 5. ((brain$ or cerebr$ or cerebell$ or intracerebral or intracranial or subarachnoid) adj5 (haemorrhage$ or hemorrhage$ or haematoma$ or hematoma$ or bleed$)).tw. 6. hemiparesis/ or hemiplegia/ or paresis/ 7. (hemipleg$ or hemipar$ or paresis or paretic).tw. 8. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 9. sitting/ or standing/ or *weight bearing/ 10. sit‐to‐stand.tw. 11. ((sit or sitting or rise or rising) adj5 (stand or standing)).tw. 12. ((stand or standing) adj up).tw. 13. ((stand or standing or rise or rising or getting up) adj10 (seat or seated or chair or sitting)).tw. 14. 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 15. 8 and 14

Appendix 4. CINAHL (EBSCO) search strategy

S21 – S13 and S20 S20 ‐ S14 or S15 or S16 or S17 or S18 or S19 S19 ‐ TI ((stand or standing or rise or rising or getting up) N10 (seat or seated or chair or sitting)) or AB ((stand or standing or rise or rising or getting up) N10 (seat or seated or chair or sitting)) S18 ‐ TI ((stand or standing) N1 up) or AB ((stand or standing) N1 up) S17 ‐ TI ((sit or sitting or rise or rising) N5 (stand or standing)) or AB ((sit or sitting or rise or rising) N5 (stand or standing)) S16 ‐ TI sit‐to‐stand or AB sit‐to‐stand S15 ‐ (MH “balance, postural”) or (MH “weight‐bearing”) or (MH “seating”) S14 ‐ (MH “rising”) or (MH “sitting”) or (MH “standing”) S13 ‐ S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S6 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 S12 ‐(MH "Gait Disorders, Neurologic+") S11 ‐TI ( hemipleg* or hemipar* or paresis or paretic ) or AB ( hemipleg* or hemipar* or paresis or paretic ) S10 ‐(MH "Hemiplegia") S9 ‐S7 and S8 S8 ‐TI ( haemorrhage* or hemorrhage* or haematoma* or hematoma* or bleed* ) or AB ( haemorrhage* or hemorrhage* or haematoma* or hematoma* or bleed* ) S7 ‐TI ( brain* or cerebr* or cerebell* or intracerebral or intracranial or subarachnoid ) or AB ( brain* or cerebr* or cerebell* or intracerebral or intracranial or subarachnoid ) S6 ‐S4 and S5 S5 ‐TI ( ischemi* or ischaemi* or infarct* or thrombo* or emboli* or occlus* ) or AB ( ischemi* or ischaemi* or infarct* or thrombo* or emboli* or occlus* ) S4 ‐TI ( brain* or cerebr* or cerebell* or intracran* or intracerebral ) or AB ( brain* or cerebr* or cerebell* or intracran* or intracerebral ) S3 ‐TI ( stroke or poststroke or post‐stroke or cerebrovasc* or brain vasc* or cerebral vasc or cva or apoplex or SAH ) or AB ( stroke or poststroke or post‐stroke or cerebrovasc* or brain vasc* or cerebral vasc or cva or apoplex or SAH ) S2 ‐(MH "Stroke Patients") OR (MH "Stroke Units") S1 ‐(MH "Cerebrovascular Disorders") OR (MH "Basal Ganglia Cerebrovascular Disease+") OR (MH "Carotid Artery Diseases+") OR (MH "Cerebral Ischemia+") OR (MH "Cerebral Vasospasm") OR (MH "Intracranial Arterial Diseases+") OR (MH "Intracranial Embolism and Thrombosis") OR (MH "Intracranial Hemorrhage+") OR (MH "Stroke") OR (MH "Vertebral Artery Dissections")

Appendix 5. AMED (Ovid) search strategy

1. cerebrovascular disorders/ or cerebral hemorrhage/ or cerebral infarction/ or cerebral ischemia/ or cerebrovascular accident/ 2. (stroke or poststroke or post‐stroke or cerebrovasc$ or brain vasc$ or cerebral vasc$ or cva$ or apoplex$ or SAH).tw. 3. ((brain$ or cerebr$ or cerebell$ or intracran$ or intracerebral) adj5 (isch?emi$ or infarct$ or thrombo$ or emboli$ or occlus$)).tw. 4. ((brain$ or cerebr$ or cerebell$ or intracerebral or intracranial or subarachnoid) adj5 (haemorrhage$ or hemorrhage$ or haematoma$ or hematoma$ or bleed$)).tw. 5. hemiplegia/ 6. (hemipleg$ or hemipar$ or paresis or paretic).tw. 7. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 8. sitting/ or seating/ or weight bearing/ 9. sit‐to‐stand.tw. 10. ((sit or sitting or rise or rising) adj5 (stand or standing)).tw. 11. ((stand or standing) adj up).tw. 12. ((stand or standing or rise or rising or getting up) adj10 (seat or seated or chair or sitting)).tw. 13. 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 14. 7 and 13

Appendix 6. British Nursing Index (Ovid) search strategy

1. stroke/ or stroke rehabilitation/ or stroke services/ 2. (stroke or poststroke or post‐stroke or cerebrovasc$ or brain vasc$ or cerebral vasc$ or cva$ or apoplex$ or SAH).tw. 3. ((brain$ or cerebr$ or cerebell$ or intracran$ or intracerebral) adj5 (isch?emi$ or infarct$ or thrombo$ or emboli$ or occlus$)).tw. 4. ((brain$ or cerebr$ or cerebell$ or intracerebral or intracranial or subarachnoid) adj5 (haemorrhage$ or hemorrhage$ or haematoma$ or hematoma$ or bleed$)).tw. 5. (hemipleg$ or hemipar$ or paresis or paretic).tw. 6. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 7. sit‐to‐stand.tw. 8. ((sit or sitting or rise or rising) adj5 (stand or standing)).tw. 9. ((stand or standing) adj up).tw. 10. ((stand or standing or rise or rising or getting up) adj10 (seat or seated or chair or sitting)).tw. 11. 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 12. 6 and 11

Appendix 7. REHABDATA search strategy

We used the following search strategy for REHABDATA.

| 'Exact phrase' | 'At least one of the words' |

| Sit to stand | Stroke |

| Sit to stand | CVA |

| Sit to stand | Hemiplegia |

| Sit to stand | Hemiparesis |

| Getting up | Stroke |

| Getting up | CVA |

| Getting up | Hemiplegia |

| Getting up | Hemiparesis |

| Standing | Stroke |

| Standing | CVA |

| Standing | Hemiplegia |

| Standing | Hemiparesis |

| Chair | Stroke |