Abstract

Background

Bullying has been identified as one of the leading workplace stressors, with adverse consequences for the individual employee, groups of employees, and whole organisations. Employees who have been bullied have lower levels of job satisfaction, higher levels of anxiety and depression, and are more likely to leave their place of work. Organisations face increased risk of skill depletion and absenteeism, leading to loss of profit, potential legal fees, and tribunal cases. It is unclear to what extent these risks can be addressed through interventions to prevent bullying.

Objectives

To explore the effectiveness of workplace interventions to prevent bullying in the workplace.

Search methods

We searched: the Cochrane Work Group Trials Register (August 2014); Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; The Cochrane Library 2016, issue 1); PUBMED (1946 to January 2016); EMBASE (1980 to January 2016); PsycINFO (1967 to January 2016); Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL Plus; 1937 to January 2016); International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS; 1951 to January 2016); Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA; 1987 to January 2016); ABI Global (earliest record to January 2016); Business Source Premier (BSP; earliest record to January 2016); OpenGrey (previously known as OpenSIGLE‐System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe; 1980 to December 2014); and reference lists of articles.

Selection criteria

Randomised and cluster‐randomised controlled trials of employee‐directed interventions, controlled before and after studies, and interrupted time‐series studies of interventions of any type, aimed at preventing bullying in the workplace, targeted at an individual employee, a group of employees, or an organisation.

Data collection and analysis

Three authors independently screened and selected studies. We extracted data from included studies on victimisation, perpetration, and absenteeism associated with workplace bullying. We contacted study authors to gather additional data. We used the internal validity items from the Downs and Black quality assessment tool to evaluate included studies' risk of bias.

Main results

Five studies met the inclusion criteria. They had altogether 4116 participants. They were underpinned by theory and measured behaviour change in relation to bullying and related absenteeism. The included studies measured the effectiveness of interventions on the number of cases of self‐reported bullying either as perpetrator or victim or both. Some studies referred to bullying using common synonyms such as mobbing and incivility and antonyms such as civility.

Organisational/employer level interventions

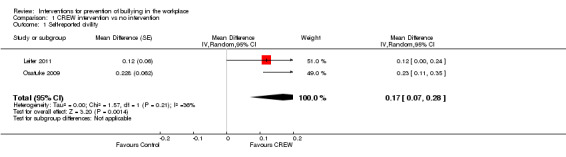

Two studies with 2969 participants found that the Civility, Respect, and Engagement in the Workforce (CREW) intervention produced a small increase in civility that translates to a 5% increase from baseline to follow‐up, measured at 6 to 12 months (mean difference (MD) 0.17; 95% CI 0.07 to 0.28).

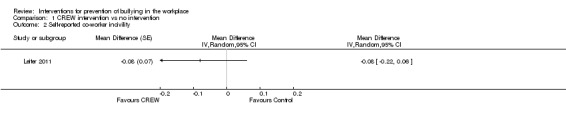

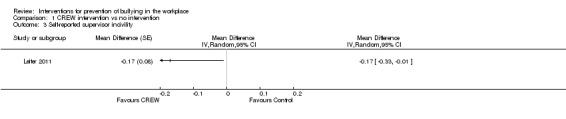

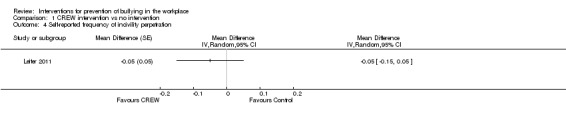

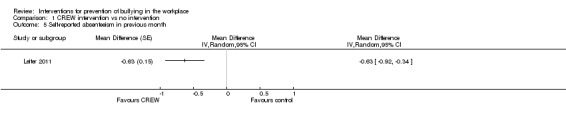

One of the two studies reported that the CREW intervention produced a small decrease in supervisor incivility victimisation (MD ‐0.17; 95% CI ‐0.33 to ‐0.01) but not in co‐worker incivility victimisation (MD ‐0.08; 95% CI ‐0.22 to 0.08) or in self‐reported incivility perpetration (MD ‐0.05 95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.05). The study did find a decrease in the number of days absent during the previous month (MD ‐0.63; 95% CI ‐0.92 to ‐0.34) at 6‐month follow‐up.

Individual/job interface level interventions

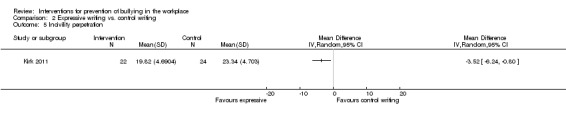

One controlled before‐after study with 49 participants compared expressive writing with a control writing exercise at two weeks follow‐up. Participants in the intervention arm scored significantly lower on bullying measured as incivility perpetration (MD ‐3.52; 95% CI ‐6.24 to ‐0.80). There was no difference in bullying measured as incivility victimisation (MD ‐3.30 95% CI ‐6.89 to 0.29).

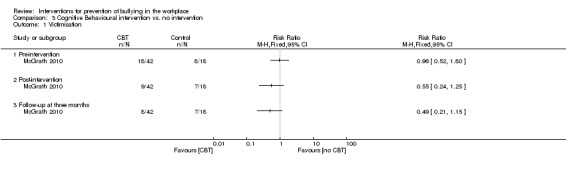

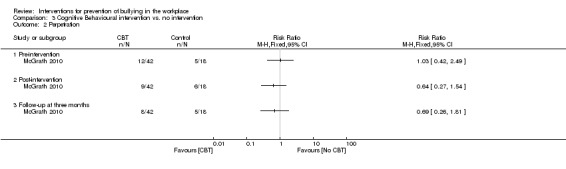

One controlled before‐after study with 60 employees who had learning disabilities compared a cognitive‐behavioural intervention with no intervention. There was no significant difference in bullying victimisation after the intervention (risk ratio (RR) 0.55; 95% CI 0.24 to 1.25), or at the three‐month follow‐up (RR 0.49; 95% CI 0.21 to 1.15), nor was there a significant difference in bullying perpetration following the intervention (RR 0.64; 95% CI 0.27 to 1.54), or at the three‐month follow‐up (RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.26 to 1.81).

Multilevel Interventions

A five‐site cluster‐RCT with 1041 participants compared the effectiveness of combinations of policy communication, stress management training, and negative behaviours awareness training. The authors reported that bullying victimisation did not change (13.6% before intervention and 14.3% following intervention). The authors reported insufficient data for us to conduct our own analysis.

Due to high risk of bias and imprecision, we graded the evidence for all outcomes as very low quality.

Authors' conclusions

There is very low quality evidence that organisational and individual interventions may prevent bullying behaviours in the workplace. We need large well‐designed controlled trials of bullying prevention interventions operating on the levels of society/policy, organisation/employer, job/task and individual/job interface. Future studies should employ validated and reliable outcome measures of bullying and a minimum of 6 months follow‐up.

Keywords: Humans, Absenteeism, Bullying, Bullying/prevention & control, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Controlled Before‐After Studies, Organizational Culture, Organizational Policy, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Social Skills, Workplace, Workplace/psychology

Plain language summary

Are there ways in which workplace bullying can be prevented?

Background

Bullying in the workplace can reduce the mental health of working people. It can also harm the organisations where these people work. There has been much research about bullying in the workplace. However, most studies have looked at how to manage bullying once it has happened, rather than trying to stop it happening in the first place. Many people who have been bullied choose to leave their job rather than face up to the bully. It is important to know if the actions workplaces take to prevent bullying are effective.

Our review question

What are the benefits of different ways of trying to prevent bullying in the workplace?

What the studies showed

We included five studies conducted with 4116 participants that measured being victim of bullying or being a bully and consequences of bullying such as absenteeism. We classified two interventions as organisational‐level, two as individual‐level and one as multi‐level. There were no studies about interventions conducted at the society/policy level.

Organisational‐level interventions

Two studies found that organisational interventions increased civility, the opposite of bullying, by about five percent. One of these studies also showed a reduction in coworker and supervisor incivility. They also found that the average time off work reduced by over one third of a day per month.

Individual‐level interventions

An expressive writing task with 46 employees, showed a reduction in the amount of bullying. A cognitive behavioural educational intervention was conducted with 60 employees who had a learning disability, but there was no significant change in bullying.

Multilevel interventions

One study evaluated a combination of education and policy interventions across five organisations and found no significant change in bullying.

What is the bottom line?

This review shows that organisational and individual interventions may prevent bullying in the workplace. However, the evidence is of very low quality. We need studies that use better ways to measure the effect of all kinds of interventions to prevent bullying.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Organisational level workplace culture intervention versus no intervention.

| Controlled before and after study | |||||

| Patient or population: Employees Setting: Workplaces in US and Canada Intervention: CREW: complex group‐based, at the organisational level Comparison: no intervention | |||||

| Outcomes | Absolute effects* | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no intervention | Risk with CREW (95% CI) | ||||

| Self‐reported workplace civility, on a scale of 1 to 5; higher score more civility Follow‐up: 6 to 12 months | Mean civility score was 3.58 points | Mean civility score was 0.17 higher (0.07 higher to 0.28 higher) | 2969 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝1 VERY LOW | |

| Self‐reported co‐worker incivility, on a scale of 0 to 6; higher score more frequent incivility Follow‐up: 6 months |

Mean coworker incivility score was 0.76 points | Mean co‐worker incivility score was 0.08 lower (0.22 lower to 0.06 higher) | 907 (1study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝1 VERY LOW | |

| Self‐reported supervisor incivility, on a scale of 0 to 6; higher score more frequent incivility Follow‐up: 6 months |

Mean supervisor incivility score was 0.57 points | Mean supervisor incivility score was 0.17 lower (0.33 lower to 0.01 lower) | 907 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝1 VERY LOW | |

| Self‐reported frequency of incivility instigation, on a scale of 0 (never) ‐ 6 (daily) **; higher score more frequent incivility Follow‐up: 6 months |

Mean incivility instigation score was 0.50 | Mean incivility instigation score was 0.05 lower (0.15 lower to 0.05 higher) | 907 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝1 VERY LOW | |

| Self‐reported days of absenteeism in previous month. Follow‐up: 6 months | Mean absenteeism in previous month was 0.83 days | Mean absenteeism in previous month was 0.63 days lower (0.92 lower to 0.34 lower) | 907 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝1 VERY LOW | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) ** 0‐6 scale confirmed by email correspondence from author CI: Confidence interval. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 We would have downgraded the quality of evidence twice due to high risk of bias caused by study limitations (lack of randomisation and blinding, and use of self‐reporting instrument) and once due to imprecision (limited sample available for outcome measurement, limited matching pre‐ and post intervention). However, once was enough to reach very low quality evidence as we started at low quality evidence because the included studies used a controlled before‐after design. We found no reason to upgrade the quality of the evidence.

Summary of findings 2. Multilevel educational intervention versus no intervention.

| Five‐arm cluster randomised trial | |||

| Patient or population: employees Setting: workplaces in several locations in the UK Intervention: education and policy development, at organisational level Comparison: no education | |||

| Outcomes | Effect of the intervention | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Bullying assessed with: Self report Follow up: mean 6 months | Insufficient data reported for analysis | 1041 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 |

| Absenteeism assessed with: organisational data | Insufficient data reported for analysis | 1041 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval. | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||

1 We would have downgraded the quality of evidence once due to high risk of bias caused by study limitations (lack of blinding and use of self‐reporting instrument) and twice due to imprecision (study conducted in mixed settings and with unclear number of participants). However, once was enough to reach very low quality evidence as we started at low quality evidence because the included studies used a controlled before‐after design. We found no reason to upgrade the quality of the evidence.

Summary of findings 3. Individual level expressive‐writing versus control‐writing.

| Controlled before and after study | |||||

| Patient or population: employees Setting: New South Wales and Queensland, Australia Intervention: expressive writing, at the individual level Comparison: control writing | |||||

| Outcomes | Absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with Control writing | Risk with Expressive‐Writing | ||||

| Self‐reported frequency of incivility victimisation. Follow up: 2 weeks | Mean number of incivility victimisations was 26 | Mean incivility victimisation in the intervention group was 3.3 fewer occurrences (5.4 fewer to 1.2 fewer) | 46 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝1 VERY LOW | |

| Self‐reported frequency of incivility perpetration. Follow up: 2 weeks | Mean number of incivility perpetrations was 23 | Mean incivility perpetration in the intervention group was 3.5 fewer occurrences (6.2 fewer to 0.8 fewer) | 46 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝1 VERY LOW | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1. We would have downgraded the quality of evidence twice due to high risk of bias caused by study limitations (lack of randomisation and blinding, and use of self‐reporting instrument) and once due to imprecision (small sample size). However once was enough to reach very low quality evidence as we started at low quality evidence because the included studies used a controlled before‐after design. We found no reason to upgrade the quality of the evidence.

Summary of findings 4. Individual level cognitive behavioural intervention versus no intervention.

| Controlled before and after study | ||||||

| Patient or population: Adult workers with a learning disability Setting: three work centres in South West Ireland Intervention: cognitive behavioural intervention, at the individual level Comparison: waiting‐list control (i.e. no treatment) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

|

Risk with no intervention (Waiting‐list control) |

Risk with cognitive behavioural intervention |

|||||

| Self‐reported victimisation. Post intervention. | 39 per 100 (18 to 64) |

21 per 100 (11 to 37) |

RR 0.55 (0.24 to 1.25) |

60 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝1 VERY LOW | |

| Self‐reported victimisation. Three‐month follow‐up. | 39 per 100 (18 to 64) |

19 per 100 (9.1 to 35) |

RR 0.49 (0.21 to 1.15) |

60 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝1 VERY LOW | |

| Self‐reported perpetration. Post intervention. |

33 per 100 (14 to 59) |

21 per 100 (11 to 37) |

RR 0.64 (0.27 to 1.54) |

60 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝1 VERY LOW | |

| Self‐reported perpetration. Three‐month follow‐up. |

28 per 100 (11 to 54) |

17 per 100 (7.5 to 32) |

RR 0.69 (0.26 to 1.81) |

60 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝1 VERY LOW | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group Grades of Evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1. We would have downgraded the quality of evidence twice due to high risk of bias caused by study limitations (lack of randomisation and blinding, and use of self‐reporting instrument) and once due to imprecision (small sample size). However, once was enough to reach very low quality evidence as we started at low quality evidence because the included studies used a controlled before‐after design. We found no reason to upgrade the quality of the evidence.

Background

Numerous terms and concepts have been used as synonyms for bullying. These include psychological terror (Leymann 1990), and work abuse (Bassman 1992). Bullying in the workplace has also been described as: "harassment, intimidation, aggression, bad attitude, coercive management, personality clash, poor management style, brutalism and working in a funny way" by Adams 1992. In the United States (US) and Canada, terms such as 'harassment' (Brodsky 1976), 'workplace trauma and employee abuse' (Wilson 1991), 'petty tyranny' (Ashforth 1994), and 'incivility' (Cortina 2001), are used. The term 'bullying' is now visible in the literature (Vessey 2009), and 'mobbing' is also used when describing harassment or bullying of employees (Einarsen 2000; Vandekerckhove 2003). In the context of the workplace, 'mobbing' can also indicate behaviour by a group of people against an individual, or as a synonym for bullying. In Australia, the most commonly used term is 'horizontal violence', which refers specifically to bullying by peers or colleagues at the same organisational level (McKenna 2003). Occasionally, the term 'harassment' has been used interchangeably with bullying. A differentiation between bullying and harassment has been proposed by McMahon 2000, who stated that bullying is abuse of power and this is the factor that differentiates harassment from bullying. It is important to note that there is legislation against 'harassment' within the United Kingdom (UK) and European law, which relates specifically to behaviour directed at individuals because of their colour, race, creed, gender, or sexual orientation (European Foundation 2010). As noted above, the terms incivility and bullying are increasingly being used interchangeably. According to Namie 2003 visualising organisational disruption on a 10‐point continuum incivility is located between 1 and 3 and workplace bullying between 4 and 9. Clark 2011 developed a 'continuum of incivility' of unacceptable workplace behaviours, based primarily on interactions with work colleagues. They argue that incivility that goes unchallenged may be perceived as bullying.

Health‐service unions have classified bullying in the workplace as "humiliating an individual, especially in front of colleagues, picking on someone; belittling someone, undermining someone’s ability to do their job; and abusive or threatening behaviour" (RCM 1996; Royal College of Nursing 2002; UNISON 1997). Major work in this area has been undertaken by Einarsen 2009, with the result that work‐related, person‐related, and physical intimidation‐type behaviours have been incorporated into the Revised Negative Acts Questionnaire. However, some concerns have been raised about the limitations of a definitive list of bullying behaviours, as there are a number of ways in which bullying can manifest itself, and these are difficult to encapsulate in a single measure, even if the instrument has good validity and reliability (Carponecchia 2011). Another issue of importance is the misconception that managers and supervisors are the sole perpetrators of bullying. There is evidence that employees can also bully managers (Gillen 2008).

Schreurs 2010 argues that before bullying takes place, several antecedents need to be present. These have been identified in the literature as role conflict, role ambiguity, level of workload, and level of autonomy in the job (Baillien 2009; Samnani 2012). Stress inherent in the job or the environment has also been named as a triggering factor (Hauge 2007; Hauge 2009). Organisational change can also lead to bullying (Skogstad 2007). This is manifest in situations where managers enforce change or conformity by bullying their employees (Beale 2011; Vartia 1996). Gillen 2008 identified perception of the victim, an individual's locus of control, power, distance, and a permissive culture in the workplace as precursors to bullying. The workplace culture influences how employees behave towards one another (Cleary 2009; Keashly 2010). Lutgen‐Sandvik 2014 argue that when bullying is not recognised and prevented, organisations will not meet their full potential. There is also evidence that employees emulate behaviour that they see in other colleagues, so that they can fit in with the workplace culture, thus coming to perceive bullying as normal (Gillen 2007).

There is wide variation in the reporting and recording of bullying around the world. This may be due to a number of factors, such as: lack of clarity in definition, variation in time frames assigned by the researcher, problems with validity and reliability of measurement, and organisational culture and structures (Zapf 2011). In the first study of workplace bullying in France, Neidhammer 2007 reported that 10% of the population studied had been exposed to bullying within the previous 12 months (N = 3132 men and 5562 women). A survey on working conditions by the European Foundation 2010 reported rates as high as 11% in Belgium and 10.7% in Luxemburg, and as low as 2.7% in Montenegro and 3% in Poland, in response to the question: "Have you been subjected to bullying or harassment in the last year?" It is clear that the criteria set by researchers, such as duration and frequency of bullying behaviour, invariably impact on the incidence levels recorded. Two studies of NHS Trust employees in the UK help to demonstrate this, with a prevalence of between 11% (self‐reported exposure to bullying in the preceding six months (Hoel 2000)), and 38% (exposure to one or more types of bullying behaviours during the previous year (Quine 1999)). More recently, in a cross‐sectional study by Carter 2013, 20% of 2950 Health‐service staff reported having been bullied in the previous six months. However, other factors may also impact on these findings, such as workplace and gender (Zapf 2011). Nielsen 2009 reported on a study of 2539 Norwegian employees, where the incidence of workplace bullying ranged from 2% to 14.3%, depending on how the behaviour was measured and frequency estimated. In the US, a 70% rate of exposure to bullying behaviour was recorded among registered nurses (N = 212), although a time criterion was not set by the researchers (Vessey 2010). An Australian workplace project included responses from 5743 workers from six states and territories, and reported that 6.8% of respondents had experienced bullying in the last six months (Safe Work Australia 2012).

The consequences of bullying have implications for the individual and the organisation. Berry 2012 reported the negative impact of bullying on novice nurses' ability to manage their workload. Generally, employees who have been bullied have lower levels of job satisfaction, higher levels of anxiety and depression, and are more likely to leave their job (Ball 2002; Quine 2001; Vessey 2010). Tehrani 2004 noted that of the 67 healthcare professionals who they had identified as having been bullied, 44% were experiencing high levels of post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). For the individual, the effects of bullying are considered to be more devastating than all other types of workplace stress put together (Hogh 2011). Building on the work of Kivimäki 2003, Nielsen 2012 suggested that early intervention was necessary to prevent bullying and subsequent psychological distress becoming a 'vicious circle' in which the victim of bullying becomes susceptible to more bullying. Indeed, prolonged exposure to workplace bullying has been identified as a key predictor of mental ill‐health five years later (Einarsen 2015). The consequences for the organisation are most often reported in financial terms. A report commissioned by the Dignity at Work Partnership has estimated that the total cost of bullying for organisations in the UK in 2007 was approximately GBP 13.75 billion (Giga 2008). In real terms, these costs arise from higher levels of sickness absence, recruitment costs associated with a propensity for staff to leave, and decreased productivity (Johnson 2009). However, Beale 2011 has argued that some employers do not tackle bullying because they benefit from its existence in the workplace. They suggest that a certain level of bullying by managers in organisations is tolerated, as it is seen as an effective means of controlling the workforce.

It is clear that workplace bullying and its prevalence, manifestations, and consequences has been the subject of a growing body of research throughout the world. There are an increasing number of organisations that provide employee assistance programmes, including counselling, as a means of dealing with the consequences of bullying (Tehrani 2011). Such management approaches are costly, deal with the aftermath of bullying, and have been largely ineffective, with high financial, individual, and organisational costs (Hoel 2011). However, what is less clear are the measures that can be put in place before the onset of bullying. Simply put, prevention of bullying requires a proactive approach and management tends to be reactive and problem‐focused.

Description of the condition

Three attributes are commonly assigned to bullying: first, the behaviour is repeated (this excludes one‐off events or personal attacks); second, the bullying behaviour has a negative effect on the victim; and third, the victim finds it difficult to defend him or herself (Einarsen 2011; Gillen 2007; Zapf 2011). There is also a fourth attribute, 'intent' of the bully, but as yet, there is no consensus about including it in definitions. Nevertheless, 'intent' is sometimes used to differentiate incivility from bullying. It has been suggested that incivility is unintentional and often circumstantial, such as a result of workplace pressures (Clark 2011). Commonly ascribed definitions of bullying used by researchers at an international level include the identification of physical actions, disruptive, psychological behaviours, and acts of incivility (Einarsen 1996; Einarsen 2011). Feblinger 2009 described various behaviours associated with incivility, similar to those listed in instruments that measure bullying (Einarsen 2009; Gillen 2007).

Bullying has been defined as: “the often intentional, repeated, persistent, offensive, abusive, intimidating, malicious or insulting behaviour, abuse of power, or unfair penal sanctions against which the victim finds it difficult to defend him or herself. It has a negative effect on the recipient, which makes them feel upset, threatened, humiliated or vulnerable; undermines their self‐confidence; and which may cause them to suffer stress” (Gillen 2008). This is similar to the Einarsen 2011 definition: "Bullying at work means harassing, offending, socially excluding someone, or negatively affecting someone’s work tasks. In order for the label bullying (or mobbing) to be applied to a particular activity, interaction or process it has to occur repeatedly and regularly (e.g. weekly) and over a period of time (e.g. about six months). Bullying is an escalating process in the course of which the person confronted ends up in an inferior position and becomes the target of systematic negative social acts. A conflict cannot be called bullying if the incident is an isolated event, or if two parties of approximately equal strength are in conflict". Although universally accepted, the Einarsen 2011 definition does not include reference to the negative effect of the bullying behaviour on the victim, i.e. that it causes stress, nor does it include reference to the issue of intent. We used the Einarsen 2011 definition of bullying in this review as it is more commonly known, and has been used extensively in research studies.

Description of the intervention

We considered all interventions within the workplace that were aimed at preventing bullying. Prevention of bullying can be more difficult to define (than bullying itself), as it may occur indirectly from other actions, such as achieving a positive workplace culture. Interventions may be targeted at individual employees, groups of employees, or organisations as a whole, and aim to prevent new cases of bullying or to prevent further instances of bullying of those who have already suffered from it. We used the levels of 'society/policy', 'organisation/employer', 'job/task' and 'Individual/job interface' to classify prevention interventions according to Vartia 2011.

Interventions aimed at preventing bullying in the workplace may be internally derived and developed, but more often are influenced by local, national or international policy (Leka 2008). According to Lamontagne 2007 interventions may be classified as primary (preventative), secondary (ameliorative), or tertiary (reactive). For the purpose of this review, we considered only primary interventions.

Vartia 2011 identified four different levels of bullying interventions as follows:

Society/policy

These interventions are normally law‐ or regulation‐based, with agreements of individual companies, for example, the Dignity at Work Partnership 2007, or European Legislation, such as the Framework Agreement on Harassment and Violence at Work (European Social Dialogue 2007). These set the standards of accepted behaviour, which are cascaded to employers who are actively encouraged to implement them.

Organisation/employer

These interventions are derived most often from law‐ or regulation‐based initiatives such as health and safety directives and the legislation described above. By definition, they are workplace‐specific and deal with the organisation's policy, aims, and expectations for the culture of the workplace, setting out clearly expected and agreed levels of behaviour. Such policies and procedures are often the first step that workplaces take when trying to influence workplace bullying (Carponecchia 2011). These documents should clearly indicate the types of behaviour that are considered unacceptable and describe a reporting mechanism for those who perceive themselves to be 'bullied' (Salin 2008b). Pre‐intervention surveys may also be carried out to establish baseline levels. Although it should be remembered that reports of bullying often rise following the introduction of a new intervention. This is perhaps because workers are now more aware of what bullying is.

Job/task

These interventions relate specifically to the job that employees are expected to do and the psychosocial environment in which they work. A risk assessment, including the identification of antecedents of bullying within the organisation, is used to inform a risk‐reduction intervention.

Individual/job interface

These interventions relate specifically to training, such as assertiveness training, or educational interventions aimed at altering behaviour or perception.

Interventions may operate at one or more of these levels. They may be targeted at individuals, in particular managers or supervisors, using a prevention perspective. They may focus on policy, procedures, and guidelines, or on locally designed and implemented education and training, which may be facilitated by occupational health departments.

How the intervention might work

Interventions to prevent workplace bullying may work by:

strengthening the policies and culture of intolerance of bullying in the workplace by processes of engagement with employees;

providing a safe environment within which mediation and negotiation may take place when problematic behaviour (not bullying) is first identified;

undertaking risk assessments of job‐related precursors to bullying; and

providing awareness‐raising or education sessions that will encourage employees to reconsider their behaviour and how they interact with colleagues.

Why it is important to do this review

Bullying has been shown to cause widespread emotional harm and distress (Gillen 2008; Hogh 2011). It is viewed as a negative behaviour in the workplace that leads to increased absences, lower productivity (Fisher‐Blando 2008), or continuing inability to work (Hogh 2011). Mental health and well‐being issues are increasingly recognised as being responsible for employee absence and turnover. This is a crucial factor in recruiting and maintaining a healthy workforce, which is currently of particular importance in healthcare services in particular (World Health Organization 2008), and in business in general, when organisations are attempting to keep costs low (CIPD 2013). It was important to do this review in order to determine the effectiveness of interventions that currently exist to prevent bullying in the workplace. Prevention is important, as often the damage that is caused by bullying is difficult to undo, and has long‐term consequences on employees' health and well‐being (Gillen 2012; Butterworth 2013).

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of workplace interventions to prevent bullying in the workplace.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all studies that evaluated the effectiveness of interventions to prevent bullying in the workplace (those targeted at individual employees, groups of employees, and organisations as a whole). We included randomised controlled trials (RCT) and cluster‐randomised controlled trials (cRCT) of person‐directed interventions. As it is more difficult to randomise whole companies or work units, we also included controlled before and after (CBA) studies and interrupted time‐series (ITS) studies of organisational interventions.

Types of participants

We included all studies where participants were employees in paid work within private, public, or voluntary organisations.

Types of interventions

We considered for inclusion all interventions aimed at primary prevention of bullying in the workplace. We excluded interventions that were focused on managing behaviours associated with bullying. Prevention is a proactive approach, which aims to reduce the incidence of bullying, while management of bullying is reactive in nature, often only responding when the detrimental impacts on individuals, groups of employees, and organisations are evident.

The interventions may have been targeted at an individual employee, a group of employees, or an organisation as a whole. We excluded interventions that were not clearly defined or that did not have a theoretical underpinning. We included studies that compared interventions with each other, with usual practice, or with no intervention. We also included interventions where groups acted as their own control. We classified included interventions according to the four levels identified by Vartia 2011 (see Description of the intervention) where possible and as multilevel interventions when they engaged multiple levels. We included studies that reported:

clearly stated aims for the implementation of interventions;

clear and detailed description of the content and nature of the intervention that enabled the reader to fully understand it; and

an explanation of the intervention's theoretical underpinnings.

We considered for inclusion all interventions aimed at individuals to prevent bullying by means of:

informational or educational interventions aimed at altering behaviour or perception;

organisational policy or incentives that discourage bullying;

enhancements to reporting mechanisms that make it easier for individuals to report problematic behaviour: and

health and safety policies that include identification of bullying as a risk.

We also considered for inclusion all interventions targeted at groups of employees or organisations as a whole to prevent bullying by means of:

Informational or media campaigns to change policy;

Incentives to change policy or encourage adherence to policies (either positive or negative); or

Interventions that will alter the accepted culture of the organisation.

Types of outcome measures

Bullying is a complex phenomenon. Hence outcome measures should reflect that complexity. We included studies that used outcome measures related to prevention of workplace bullying, i.e. outcomes that showed a change in the number of reported cases of bullying perpetration, victimisation, or level of absenteeism. Self‐reported outcomes were taken in preference to secondary observations.

Primary outcomes

We included studies that reported on the number of cases of self‐reported bullying, whether recorded by perpetrator or victim. Hence we defined the primary outcome as the number of occurrences of bullying perpetration or victimisation, or both. Perpetration refers to a measurable act of bullying, while victimisation refers to recipients' reports of such action. We also accepted common synonyms such as mobbing and incivility and antonyms such as civility. We included dichotomous, categorical, integer and continuous measures of bullying.

Secondary outcomes

When included studies reported intervention effectiveness with consequential measures of bullying, namely stress, depression, absenteeism or sick leave, in addition to our primary outcome, we included these data.

We used only the primary outcomes as inclusion criteria. We used the secondary outcomes only to explain the findings of the primary outcomes because the included studies using our secondary outcomes are only a subset of all studies that reported our primary outcomes.

Search methods for identification of studies

We systematically searched for reports on the effectiveness of one or more interventions to prevent bullying in the workplace. The search strategy consisted of key words, including commonly used synonyms for bullying, the workplace setting, employees, and workplace interventions.

Electronic searches

We conducted a search in the following databases:

The Cochrane Work Group Trials Register (August 2014; update search not undertaken as small number of papers were retrieved in the original search).

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; The Cochrane Library 2016, issue 1).

PUBMED (1946 to January 2016).

EMBASE (1980 to January 2016).

PsycINFO (1967 to January 2016).

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL Plus; 1937 to January 2016).

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA; 1987 to January 2016).

ABI Global (earliest record to January 2016).

International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS; 1951 to January 2016).

Business Source Premier (BSP) (earliest record to January 2016).

OpenGrey (Previously known as OpenSIGLE‐System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe; 1980 to December 2014; update search not undertaken as small number of papers retrieved in original search).

We used an initial strategy developed by the Cochrane Work Group's Information Specialist, outlined in Appendix 1, which we adapted as required for each database. Our search focused primarily on titles and abstracts, with the aim of reducing the number of irrelevant articles retrieved. The Cochrane Work Group's Information Specialist and PG conducted the literature searches.

Searching other resources

Initially, we used a common online search engine to locate relevant websites to access otherwise unpublished material. We also searched the reference lists of all returned studies to identify potential additional studies. We also contacted experts in this area of research (frequently cited authors) to minimise potential studies being missed and to identify unpublished material that may be relevant. We also handsearched proceedings of conferences that focused on the issue of workplace bullying that we found during our database and website searches.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We discarded all duplicate publications of studies. To identify potentially eligible studies, at least two review authors (PG and one other review author by rotation) screened all titles and abstracts. All authors (PG, MS, GK, CB, AL) undertook a calibration exercise to ensure consistency in selection of potentially eligible papers. Then two review authors (all authors were involved) independently read the abstracts and titles selected for possible inclusion. We screened the references without conferring, against the inclusion criteria. We only conferred once we had individually decided which papers should be included in the review. When a pair of authors could not agree, a third member of the review team arbitrated. We did not blind ourselves to authors, journal, or date of publication.

Data extraction and management

We designed a data extraction form based on forms developed for other Cochrane Work Group reviews. Two review authors extracted data using the agreed form (PG and one other review author by rotation). We resolved disagreements through discussion with at least one other review author. We filed all studies that had data extracted along with the data extraction forms for the purpose of an audit trail. One review author (PG) transferred all data into RevMan 5.3 (RevMan 2014), and another review author (GK) checked the accuracy of the data transfer.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For randomised controlled trials, three review authors (PG, MS, GK) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included studies according to the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

For non‐randomised designs, we adapted the approach advocated by Downs 1998, and supported by Deeks 2003. We based our assessment of risk of bias solely on the two internal validity scales consisting of 13 items, as they were the most appropriate in this case (Verbeek 2012). In order to report the ROB outcome in RevMan 2014, we had to adapt the scoring slightly. Instead of using scores 1 or 0 we assessed each item as 'high risk', 'low risk', or 'unclear risk', depending on the study information provided. We independently assessed the internal validity of studies using the Downs 1998 Checklist. For the non‐randomised studies allocation concealment is not applicable so we judged them to have a high risk of bias. Pairs of review authors independently examined the risk of bias of the included studies. We resolved disagreements by discussion.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated risk ratios (RRs) for dichotomous outcomes and means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous outcomes. When the results could not be entered in the data tables, we described them in the Characteristics of included studies and in the text.

We did not identify any interrupted time‐series studies (ITS) that met our inclusion criteria. If these are included in future versions of the review, we will extract data from the original papers and re‐analyse them according to the recommended methods for analysis of ITS designs for inclusion in systematic reviews (Ramsay 2003).

Unit of analysis issues

Although the included studies' interventions operated in very different ways, they all worked at the level of the individual, that is, aiming to achieve individual outcomes to reduce the level of victimisation, perpetration, or both. Hence the unit of analysis was the individual. One study was a cluster‐randomised trial but it reported insufficient data to assess the cluster effect. If future updates of this review find cluster‐randomised studies that report sufficient data to be included in the meta‐analysis, but the authors do not make an allowance for the design effect, we will calculate the design effect based on a fairly large assumed intra‐cluster correlation of 0.10. We base the assumption that 0.10 is a realistic estimate on studies about implementation research (Campbell 2001). We will follow the methods stated in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions for the calculations (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the authors of three of the studies included in this review. For the McGrath 2010 study, we clarified whether the participants were in paid work. We also contacted one of the authors of the Hoel 2006 study to seek clarification on the process of randomisation and to ask for data in a format that could be more easily included in the analysis. However, we did not receive a response. In addition, communication with Leiter 2011 provided clarification on data from their multivariate analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We could combine results data from different studies in a meta‐analysis for just one comparison. Hence we needed to assess heterogeneity between just two studies (Leiter 2011; Osatuke 2009). If more studies are included in future versions of the review, we will group them based on similar study designs, interventions, and outcome measures. We will test for statistical heterogeneity by means of the Chi² test as calculated in Review Manager 5.3 software (RevMan 2014). We will use a significance level of P < 0.01 to indicate whether or not there is a problem with heterogeneity. Moreover, we will quantify the degree of heterogeneity using the I² statistic, where an I² value of 0% to 40% may be not important, 30% to 60% may represent important heterogeneity, 50% to 90% may indicate substantial heterogeneity and over 75% to indicate considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2003).

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed reporting biases based on publication, time lag, location and language as recommended by Higgins 2011 and looked for signs of reporting biases within articles by checking that all stated outcomes had been reported. We prevented location bias by searching across multiple databases. We prevented language bias by including all eligible articles regardless of publication language.

Data synthesis

We pooled data from two studies judged to be clinically homogeneous (similar intervention, research design and outcome) in a meta‐analysis using Review Manager 5.3 software (RevMan 2014). Because these studies were statistically heterogeneous, we used a random‐effects model. Should we identify more statistically homogeneous studies to include in meta‐analyses in future updates of this review we will use a fixed‐effect model. We conducted a sensitivity check by using the fixed‐effect model to reveal differences in results. We included a 95% confidence interval (CI) for all effect estimates.

Should we find ITS studies in future updates, we will use the standardised change in level and change in slope as effect measures. We will perform meta‐analyses using the generic inverse variance method. We will enter the standardised outcomes into Review Manager 5.3 as effect sizes, along with their standard errors (SEs).

Quality of the evidence

We used the GRADE approach, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, and GRADEproGDT software to present the quality of evidence in ‘Summary of findings’ tables (Higgins 2011). The quality of a body of evidence for a specific outcome is based on five factors: 1) limitations of the study designs; 2) indirectness of evidence; 3) inconsistency of results; 4) imprecision of results; and 5) publication bias.

The GRADE approach specifies four levels of quality (high, moderate, low and very low), incorporating the factors noted above. Quality of evidence by GRADE should be interpreted as follows:

High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect;

Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different;

Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect;

Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Given the paucity of studies included in this review, we could not perform subgroup analyses. In future updates, if there are sufficient data, we will undertake subgroup analyses based on gender, occupation, type of intervention for prevention, type of organisation, location (country of origin), as well as type and duration of interventions.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not find a sufficient number of studies to permit us to conduct sensitivity analyses, that is, to test if our findings were affected by the choice of studies included in analyses. If we have sufficient studies in future updates, we will conduct sensitivity analyses in which we exclude studies we judge to have a high or unclear risk of bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

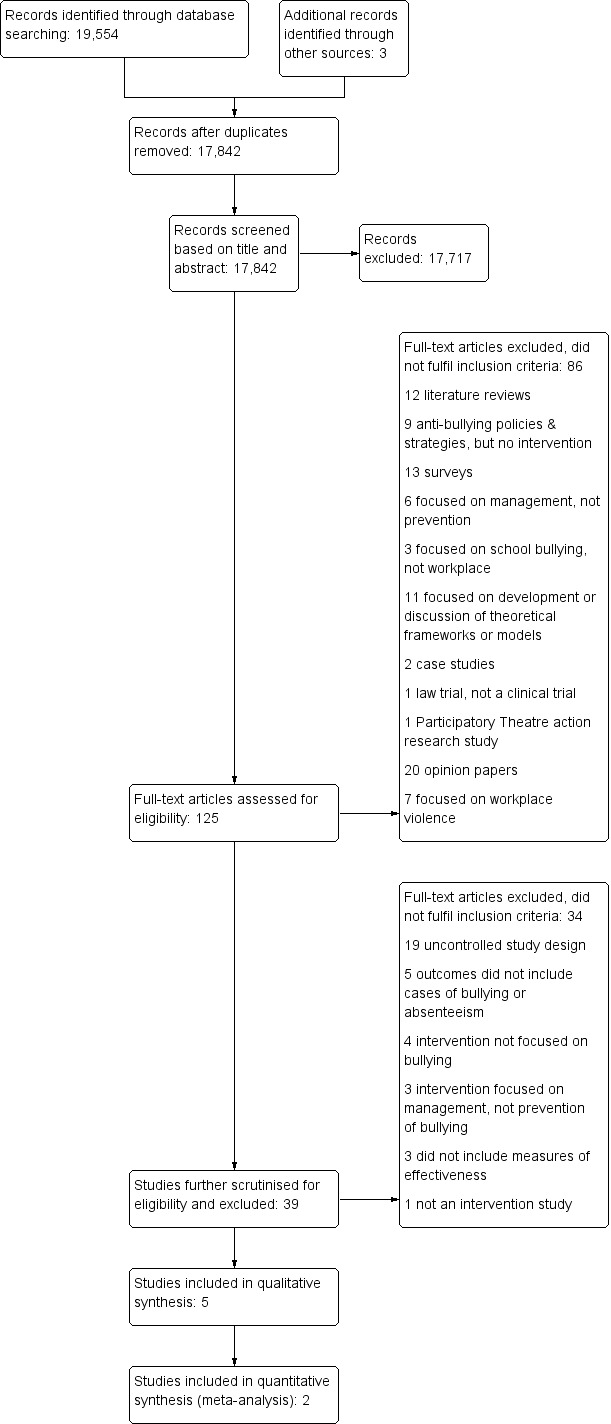

Our systematic search generated 19,544 references (Figure 1). We identified 125 references that we considered potentially eligible for inclusion and accessed the full text articles. Following further scrutiny, we excluded 86 of these. We read the remaining 39 in greater detail and we excluded 34 as they did not meet our inclusion criteria. Five studies (Hoel 2006; Kirk 2011; Leiter 2011; McGrath 2010; Osatuke 2009) met the inclusion criteria for this review.

1.

PRISMA Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Each of the included studies reported on at least one intervention that was clearly defined or had a clear theoretical underpinning. See Characteristics of included studies.

Study Design

Of the five included studies, one was a cluster‐RCT (cRCT) (Hoel 2006), and the other four were CBA studies (Kirk 2011; Leiter 2011; McGrath 2010; Osatuke 2009).

Two CBA studies used a group intervention with surveys before and after the delivery of the intervention (Leiter 2011; Osatuke 2009). One of these was followed‐up at 12 months and reported separately (Leiter 2011). One other CBA study compared reported levels of incivility, perpetration, and victimisation before and after the intervention (Kirk 2011). In another CBA study, victimisation and bullying behaviour were measured at three time points, one before and two after intervention (McGrath 2010).

In the cRCT, clusters were randomly allocated to four different bullying intervention programmes or a control condition.

Setting and participants

One study was carried out with a large healthcare organisation with employees dispersed across Canada (Leiter 2011; N = 907), and another with five organisations with employees across several US states (Osatuke 2009; N = 2062).

In Hoel 2006, the 1041 participants were employees from five public sector organisations in the UK: three NHS trusts (one focused specifically on mental health), one civil service department, and one police force).

The Kirk 2011 study was carried out in Australia. Of the 46 participants 48% were in managerial or professional positions, 15% were employed psychology students, and details of the remaining participants' employment were not given.

The McGrath 2010 study was carried out in Ireland. The 60 participants were adults with a borderline, mild, or moderate learning disability, based in a work centre. We contacted the authors of the paper to determine whether or not the participants in this study were paid for the work. The authors responded that the participants received 'therapeutic earnings' but not enough to affect their benefits. We decided that while these participants could not be considered to be representative of most paid workers, they did meet the inclusion criteria for this review.

The five included studies had altogether 4116 participants.

Interventions

All included studies took account of background literature about bullying and how to prevent it. Two studies were conducted within a framework for Civility, Respect, and Engagement in the Workforce (CREW; Leiter 2011; Osatuke 2009). One study was clearly informed by the intervention literature especially when it comes to the design of the intervention programme, the need to account for organisational context, and to include employee participation (Hoel 2006). The expressive writing intervention was based on the theory of self‐efficacy and the demonstrated potential for behaviour change that may result from 'poor emotional processing' (Kirk 2011). The final included intervention was based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which is suitable for effecting behaviour change (McGrath 2010). According to the authors their intervention was based on "...other‐bullying programs, anger management programs and relaxation training programs adapted to meet the needs of adults with a learning disability".

Society/policy level interventions

None of the included studies reported on interventions at the society/policy level.

Organisation/employer level interventions

Two studies reported on the effectiveness of a culture change intervention, which was intended to address Civility, Respect and Engagement at Work (CREW) at the organisational or employer level (Leiter 2011; Osatuke 2009). The core elements of the CREW intervention are included in the Characteristics of included studies. This was a substantial intervention, demanding organisational commitment to a process that lasted longer than six months.

Job/task level interventions

None of the included studies reported on interventions aimed solely at the job/task level.

Individual/job interface level interventions

One study described the effects of an educational programme that included a three‐hour negative behaviour awareness intervention on acceptable and unacceptable behaviours within the workplace (Hoel 2006). We judged the intervention to operate at the individual/job interface level.

One study used an educational intervention aimed at enhancing self‐efficacy to reduce workplace incivility victimisation and perpetration through a self‐administered writing intervention, which was completed by participants over a three‐day period (Kirk 2011). The control group completed a sham writing task.

One study described a cognitive‐behavioural educational intervention developed from other unstipulated bullying, anger management and relaxation programmes, which was adapted to meet the needs of adults with a learning disability (McGrath 2010). The intervention lasted 90 minutes and was delivered once a week, at the same time each week, for ten weeks. The intervention included information on bullying and its consequences, raised awareness of personal triggers, and taught participants ways to deal with bullying. The intervention was directed at bullies, victims, and bystanders (those who had witnessed bullying of others).

Multilevel interventions

One study described an educational intervention programme operating at three levels: organisation/employer level, job/task and individual/job interface levels (Hoel 2006). The programme was comprised of three intervention components: policy communication, stress management, and negative behaviour awareness training. These were implemented in various combinations that always included policy communication which we judged to operate at the organisation or employer level. We judged the stress awareness session to operate at the job/task level, whilst we judged the negative behaviour component of the programme to operate at the individual/job interface level.

Outcomes

Studies used several outcomes to establish the effectiveness of interventions that were aimed at preventing bullying in the workplace.

Primary outcomes

Bullying victimisation was measured in all of the included studies. Two studies measured bullying victimisation through self‐report questionnaire (Hoel 2006) or interview (McGrath 2010).

The studies by Kirk 2011 and Leiter 2011 recorded experiences of incivility. Kirk 2011 defined incivility as "discourteous interactions between employees that violate norms of mutual respect. Such behaviour can involve expression of hostility, privacy invasion, exclusionary behaviour, and gossiping". The study by Leiter 2011 reported extending previous work and used a similar pre‐existing definition of incivility. We regarded the behaviours covered by this definition as common bullying behaviours.

Two studies reported on experiences of civility (Osatuke 2009; Leiter 2011) using a five‐point Likert type scale that averaged the answers on eight questions concerning respect, cooperation, conflict resolution, co‐worker personal interest, co‐worker reliability, anti‐discrimination, value differences, and supervisor diversity acceptance. We regarded these behaviours as the inverse of incivility and therefore an indirect measure of bullying victimisation. The scale scores ranged from one to five.

In both Leiter 2011 and Osatuke 2009 there were differences in baseline scores between the intervention and the control group. Both studies used a multivariate linear regression analysis for taking these differences into account. We used the betas from the regression analyses as the mean differences of the change values and the associated standard errors (SE). For Leiter 2011, we received the Standard Errors (SE) belonging to the betas on request from the authors. For Osatuke 2009, we calculated SE using beta divided by the square root of the reported F‐value.

Bullying perpetration was measured in four of the included studies. Two studies measured bullying perpetration through self‐report questionnaire (Hoel 2006) or interview (McGrath 2010). We regarded the incivility measures reported as incivility perpetration (Kirk 2011) and instigated incivility (Leiter 2011) as bullying perpetration.

Secondary outcomes

In addition to reporting intervention effects on one or more of our primary outcomes, two studies reported intervention effects on absenteeism from work (Hoel 2006; Leiter 2011). Leiter 2011 reported absenteeism using self‐report and 'aggregate institutional data' and Hoel 2006 used self‐reports to measure time off work. We did not identify the secondary outcomes stress or depression in any of the included studies.

Follow‐up

Follow‐up ranged from two weeks (Kirk 2011) to 12 months or longer. Commonly, longer interventions were associated with longer follow‐up, from three to six months (Hoel 2006; McGrath 2010), to 11‐14 months for culture change interventions (Osatuke 2009; Leiter 2011). Longer follow‐up was associated with greater loss of participants.

Excluded studies

There is considerable literature on workplace bullying, most of it focused on the nature, manifestations, consequences, and management. This is reflected in the number of papers that we initially found (Figure 1) and subsequently excluded. We screened and excluded 86 full‐text papers.

Twelve papers were literature reviews (Bartlett, 2011; Beech 2006; Branch 2013; Carroll 2012; Dollard 2007; Hodgins 2014; Hutchinson 2013; Illing 2013; Johnson 2009; Stagg 2010; Vessey 2010; Wassell 2009).

Nine papers reported on the implementation or proposed application of anti‐bullying policies or strategies but did not include testing of their effectiveness (Bulutlar 2009; Duffy 2009; Hollins 2010; Leka 2011; Meglich‐Sespico 2007; Ng 2010; Rasmussen, 2011; Sheehan 1999; Srabstein 2008).

Thirteen papers were surveys and reported on the frequency and nature of bullying behaviour, its impact and outcomes (Baillien 2009; Duncan 2001; Hogh 2011; Mangione 2001; O'Driscoll 1999; Oluremi 2007; Salin 2008a; Salin 2008b; Spector 2007; van Heughten 2010; Vessey 2010; Walrafen 2012), or on the impact of leadership style on frequency of bullying (Nielsen 2013).

Six papers focused on the management of workplace bullying (Appelbaum 2012; Bentley 2012; Gardner 2001; Kahl 2007; Speery 2009; Steen 2011), and three on interventions with school children (Dawn 2006; Farrington 2009; Halleck 2008).

Eleven papers focused on theoretical frameworks or models but did not include an intervention (Baillien 2011a; Djurkovic 2006; Djurkovic 2008; Johnson 2011; Laschinger 2012; Law 2011; Nielsen 2008; Olender‐Russo 2009; Ramsay 2011; Saam 2010; Schat 2000).

Two papers reported on case studies (Lippel 2011; Namie 2009), one reported on a trial in a court of law (Weber 2009), and one reported on the use of a participatory theatre action research approach to deal with bullying (Quinlan 2009).

Twenty papers were opinion papers (Al‐Daraji 2009; Christmas 2007; Cleary 2010; Dal Pezzo 2009; DelBel 2003; Egues 2013; Farrell 2007; Gerardi 2007; Gilmore 2006; Hubert 2003; Kolanko 2006; Longo 2007; Lutgen‐Sandvik 2012; Mahlmeister 2009; Namie 2004; Rayner 1999; Resch 1996; Shreeavtar 2002; Tehrani 1995; Yamada 2009), seven focused on workplace violence directed at healthcare workers by patients (Arnetz 2000; Carter 1997; Farrell 2005; Molloy 2006; Viitasara 2004; Voelker 1996; Zampeiron 2010), and one study focused on assertiveness training for nurses but did not have a control group (Karakas 2015).

We subjected the remaining 37 potentially eligible papers to a more detailed review against the inclusion criteria, and subsequently excluded all of them because their study design did not meet our inclusion criteria, primarily due to lack of control (Barrett 2009; Beirne 2013; Bortoluzzi 2014; Bourbonnais 2006a; Brunges 2014; Ceravolo 2012; Chipps 2012; Collette 2004; Cooper‐Thomas 2013; Crawford 1999; Egues 2014; Feda 2010; Gedro 2013; Gilbert 2013; Grenyer 2004; Griffin 2004; Holme 2006; Karakas 2015; Lasater 2015; Latham 2008; Leiter 2011; Longo 2011; Léon‐Pérez 2012; Mallette 2011; Meloni 2011; Melwani 2011; Mikkelsen 2011; Nikstatis 2014; Oostrom 2008; Osatuke 2009; Pate 2010; Probst 2008; Stagg 2011; Stevens 2002; Strandmark 2014; Wagner 2012; Woodrow 2014).

Further details of these studies are presented in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

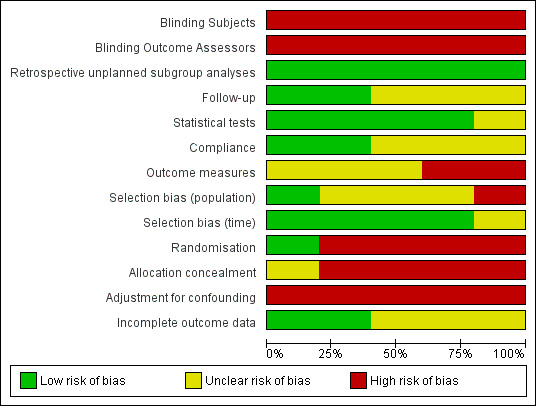

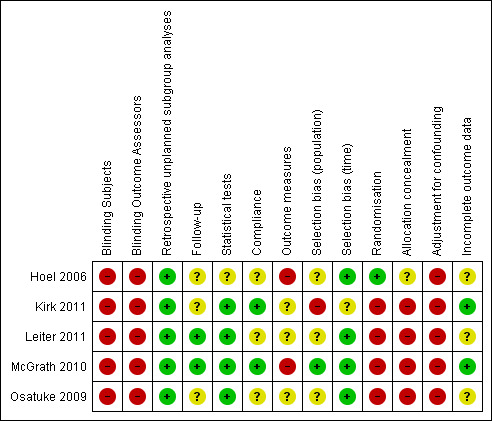

We provide an overview of our risk of bias judgements across studies in Figure 2 and per study in Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies using the Downs 1998 checklist.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for included studies.

Blinding

Blinding of subjects and outcome assessors was not evident in any of these studies. Therefore we judged all studies to have a high risk of bias in both domains.

Retrospective unplanned subgroup analyses

We did not find evidence of data dredging or additional retrospective unplanned subgroup analyses. Therefore we judged all studies to have a low risk of bias in this domain.

Follow‐up

There was wide variation in follow‐up with Kirk 2011 using only two weeks, McGrath 2010 using three months, Hoel 2006 using approximately six months, Leiter 2011 using 12 to 24 months. Pre‐ and post‐intervention matching was reported to be difficult. Furthermore, Osatuke 2009 reported a 'chronological mismatch' between the comparison and intervention groups. We calculated their follow‐up to be 11 to 14 months. We judged Leiter 2011 and McGrath 2010 to have a low risk of bias and the remaining three to have an unclear risk of bias in this domain.

Statistical tests

We judged statistical tests to be clearly described and appropriately applied in almost all cases. We found that Hoel 2006 failed to clarify in sufficient detail the main effects of the intervention. Other authors reported descriptive statistics and analysis of variance. Accordingly we judged Hoel 2006 to have an unclear risk of bias and all other studies to have a low risk of bias in this domain.

Compliance

We found a wide variation with compliance across the range of interventions. We judged the resulting risk of bias to be unclear for the educational intervention (Hoel 2006), and low for the expressive writing and cognitive behavioural intervention (Kirk 2011; McGrath 2010). Due to lack of data on compliance, we judged risk of bias for the CREW Intervention to be unclear (Osatuke 2009; Leiter 2011).

Outcome measures

The very nature of workplace bullying and its assessment pre‐ and post‐intervention is complex and we judged outcome measurement to be at high risk of bias in two studies (Hoel 2006; McGrath 2010) and unclear in three (Kirk 2011; Leiter 2011; Osatuke 2009). We judged the risk of bias for all of the outcome measures to be affected by the use of self‐report. This is because the sensitivity and stigma associated with perpetrating or experiencing bullying has an intrinsic risk of bias due to social desirability. Self‐reported measures are therefore likely to be biased against reporting true levels. On the other hand, investigators in raising the topic will increase awareness and create bias in the other direction (Hawthorne effect). We judged all of the studies to be susceptible to these latent risks of bias.

Selection bias (population)

One study was drawn from a well‐defined population (McGrath 2010) and we judged it to be at low risk of selection bias. Three studies were drawn from disparate healthcare workplaces and we judged them to have an unclear risk of bias (Hoel 2006; Leiter 2011; Osatuke 2009). The remaining study used a convenience sample of employees from a variety of unspecified workplaces and we judged it to be at high risk of bias (Kirk 2011).

Selection bias (time)

We judged four studies to have a low risk of selection bias with regard to the time frame for recruitment (Hoel 2006; Leiter 2011; McGrath 2010; Osatuke 2009). We judged the study by Kirk 2011 to have an unclear risk of bias because we were unable to determine the time frame.

Randomisation

We judged four studies to be at high risk of bias due to lack of randomisation (Kirk 2011; Leiter 2011; McGrath 2010; Osatuke 2009). We judged the single cluster‐randomised trial to be at low risk of bias (Hoel 2006).

Allocation concealment

We judged four controlled before‐after studies to be at high risk of bias due to lack of allocation concealment (Kirk 2011; Leiter 2011; McGrath 2010; Osatuke 2009). We judged the single cRCT to have an unclear risk of bias on this domain because the study did not report having concealed allocation (Hoel 2006).

Adjustment for confounding

One study described relevant confounders (Hoel 2006). However, we found no evidence of adjustment in the statistical analysis and this lead to our judgement of high risk of bias due to confounding. We were unable to identify confounders in the other four studies (Kirk 2011; Leiter 2011; McGrath 2010; Osatuke 2009) and therefore we judged them all to have a high risk of bias due to confounding.

Incomplete outcome data

Details on participant loss to follow‐up was provided in two studies and we deemed them to be at low risk of bias (Kirk 2011; McGrath 2010). Three studies by Hoel 2006; Leiter 2011; Osatuke 2009 reported numbers of participants lost to follow‐up but we were unable to determine whether this had been taken into account in analyses. Consequently, we judged them to be at unclear risk of bias.

Overall risk of bias

We judged all five included studies to have a high risk of bias overall based on: lack of blinding of subjects and outcomes assessors (Hoel 2006; Kirk 2011; Leiter 2011; McGrath 2010; Osatuke 2009), unreliable outcome measures (Hoel 2006; McGrath 2010), selection bias (Kirk 2011), lack of randomisation (Kirk 2011; Leiter 2011; McGrath 2010; Osatuke 2009), open allocation (Kirk 2011; Leiter 2011; McGrath 2010; Osatuke 2009) and lack of adjustment for confounding (Hoel 2006; Kirk 2011; Leiter 2011; McGrath 2010; Osatuke 2009). See Figure 3 for a summary of our judgements about each risk of bias for each included study.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4.

Society/policy level

None of the included studies reported on the effects of interventions at the society/policy level.

Organisational/employer level

Workplace culture intervention versus no intervention

Effects on bullying in general

Two controlled before‐after studies reported on the effects on civility of the same organisational Intervention titled Civility, Respect, and Engagement in the Workforce (Leiter 2011; Osatuke 2009). In the meta‐analysis of the two studies, the CREW intervention produced a small increase in civility at a follow‐up time between 6 and 14 months (Mean Difference (MD) 0.17 95% CI 0.07 to 0.28; scale range from 1 to 5; Analysis 1.1; 2 studies).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CREW intervention vs no intervention, Outcome 1 Self‐reported civility.

Effects on bullying perpetration

Leiter 2011 reported a small reduction in co‐worker incivility (MD ‐0.08; 95% CI ‐0.22, to 0.06; scale range from 1 to 6; Analysis 1.2; 1 study), and a small non‐significant reduction in supervisor incivility (MD ‐0.17; 95% CI ‐0.33 to ‐0.01; Analysis 1.3; 1 study) at the 6‐month follow‐up (Leiter 2011). The CREW intervention also produced a small non‐significant reduction in the frequency of incivility perpetration (MD ‐0.05; 95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.05; scale range from 1 to 6; Analysis 1.4; 1 study).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CREW intervention vs no intervention, Outcome 2 Self‐reported co‐worker incivility.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CREW intervention vs no intervention, Outcome 3 Self‐reported supervisor incivility.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CREW intervention vs no intervention, Outcome 4 Self‐reported frequency of incivility perpetration.

Effects on secondary outcomes

Leiter 2011 reported a reduction in absenteeism during the previous month (MD ‐0.63 days per month; 95% CI ‐0.92 to ‐0.34); Analysis 1.5; 1 study) at 6‐month follow‐up.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CREW intervention vs no intervention, Outcome 5 Self‐reported absenteeism in previous month.

We rated the overall quality of evidence about the effectiveness of the CREW intervention as very low (Table 1).

Job/task level

None of the included studies reported uniquely on the effects of interventions at the job/task level, although one multilevel study incorporated one intervention at this level (Hoel 2006). We were unable to determine the effect of this intervention specifically at the job/task level.

Individual/job interface level

Expressive writing intervention versus control writing

Effects on bullying victimisation

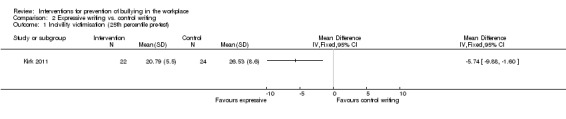

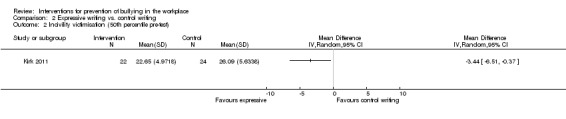

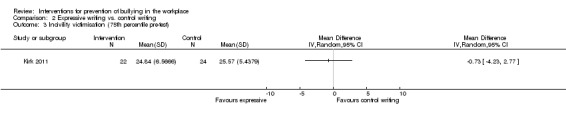

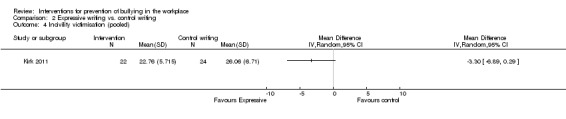

A controlled before‐after study reported results of an expressive writing intervention (Kirk 2011) taking account of baseline scores. The authors found that the expressive writing intervention reduced incivility victimisation for participants who initially scored low (MD ‐5.74; 95% CI ‐9.88 to ‐1.60; Analysis 2.1) and moderate (MD ‐3.44; 95% CI ‐6.51 to ‐0.37; Analysis 2.2) on the incivility victimisation pre‐test. The expressive writing intervention had no significant effect on incivility victimisation with participants with high scores on the pre‐test (MD ‐0.73; 95% CI ‐4.23 to 2.77; Analysis 2.3) nor when we pooled the data (MD ‐3.30; 95% CI ‐6.89 to 0.29) (Analysis 2.4).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Expressive writing vs. control writing, Outcome 1 Incivility victimisation (25th percentile pre‐test).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Expressive writing vs. control writing, Outcome 2 Incivility victimisation (50th percentile pre‐test).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Expressive writing vs. control writing, Outcome 3 Incivility victimisation (75th percentile pre‐test).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Expressive writing vs. control writing, Outcome 4 Incivility victimisation (pooled).

Effects on bullying perpetration

After controlling for pre‐test scores, participants in the expressive writing intervention arm scored significantly lower on workplace incivility perpetration than participants in the control writing arm in one study (Kirk 2011) (MD ‐3.52; 95% CI ‐6.24 to ‐0.80; Analysis 2.5).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Expressive writing vs. control writing, Outcome 5 Incivility perpetration.

Effects on secondary outcomes

This study did not report effects on absenteeism.

We rated the overall quality of evidence about the expressive writing intervention as very low (Table 3).

Cognitive‐behavioural intervention versus no intervention

Effects on bullying victimisation

A controlled before‐after study reported results of a cognitive‐behavioural intervention (McGrath 2010). The authors evaluated the intervention's effectiveness using the number of people who reported they had been victims of bullying. The authors took measurements at baseline, following completion of the intervention, and at three months post‐intervention. The likelihood of being bullied was similar at baseline across the intervention and control groups. Following the intervention, there was no significant difference in the risk of being bullied (Risk Ratio (RR) 0.55; 95% CI 0.24 to 1.25; Analysis 3.1), and there was no change at three‐month follow‐up (RR 0.49; 95% CI 0.21 to 1.15; Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Cognitive Behavioural intervention vs. no intervention, Outcome 1 Victimisation.

Effects on bullying perpetration

The risk of bullying others was not significantly lower following the intervention (RR 0.64; 95% CI 0.27 to 1.54; Analysis 3.2), or at the three‐month follow‐up (RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.26 to 1.81; Analysis 3.2). However, the wide confidence interval and the small sample size leaves a lot of uncertainty about the true effect.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Cognitive Behavioural intervention vs. no intervention, Outcome 2 Perpetration.

Effects on secondary outcomes

This study did not report effects on absenteeism.

We rated the overall quality of evidence about the cognitive‐behavioural intervention as very low (Table 4).

Multilevel Intervention

Effects on primary outcomes

A five‐arm cluster‐randomised controlled study of three interventions in different combinations, using a partial factorial design, conducted at five sites, reported outcomes as percentages with small non‐significant changes post‐intervention (Hoel 2006). Trends in the data were difficult to see as the authors report increases and decreases in outcomes separately for all five settings. Of the 1041 participants who completed the pre‐intervention survey, only 150 employees completed the training intervention. We wrote to the authors requesting access to their raw data so that we could have conducted our own analysis but received no response.

Effects on secondary outcomes

The authors found no effect on self‐reported absenteeism.

We rated the overall quality of evidence about the multilevel intervention as very low (Table 2).

Discussion

Summary of main results

None of the included studies explored the effectiveness of interventions at society/policy‐level.

We found two large CBA studies with 2969 participants that evaluated organisational/employer level interventions. These studies evaluated the effectiveness of a workplace culture intervention to achieve Civility, Respect, and Engagement in the Workforce (CREW) (Leiter 2011; Osatuke 2009). The meta‐analysis of the two studies showed a small increase in civility (MD 0.17; 95% CI 0.07 to 0.28). This is a 5% increase from the baseline score. One of the two studies reported that the CREW intervention produced a small decrease in supervisor incivility victimisation (MD ‐0.17; 95% CI ‐0.33 to ‐0.01) but not in co‐worker incivility victimisation (MD ‐0.08; 95% CI ‐0.22 to 0.08) or in self‐reported incivility perpetration (MD ‐0.05 95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.05). The study did find a decrease in the number of days absent during the previous month (MD ‐0.63; 95% CI ‐0.92 to ‐0.34) at 6‐month follow‐up.