Abstract

Background

Nicotine receptor partial agonists may help people to stop smoking by a combination of maintaining moderate levels of dopamine to counteract withdrawal symptoms (acting as an agonist) and reducing smoking satisfaction (acting as an antagonist).

Objectives

To review the efficacy of nicotine receptor partial agonists, including varenicline and cytisine, for smoking cessation.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group's specialised register for trials, using the terms ('cytisine' or 'Tabex' or 'dianicline' or 'varenicline' or 'nicotine receptor partial agonist') in the title or abstract, or as keywords. The register is compiled from searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO using MeSH terms and free text to identify controlled trials of interventions for smoking cessation and prevention. We contacted authors of trial reports for additional information where necessary. The latest update of the specialised register was in May 2015, although we have included a few key trials published after this date. We also searched online clinical trials registers.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials which compared the treatment drug with placebo. We also included comparisons with bupropion and nicotine patches where available. We excluded trials which did not report a minimum follow‐up period of six months from start of treatment.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data on the type of participants, the dose and duration of treatment, the outcome measures, the randomisation procedure, concealment of allocation, and completeness of follow‐up.

The main outcome measured was abstinence from smoking at longest follow‐up. We used the most rigorous definition of abstinence, and preferred biochemically validated rates where they were reported. Where appropriate we pooled risk ratios (RRs), using the Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect model.

Main results

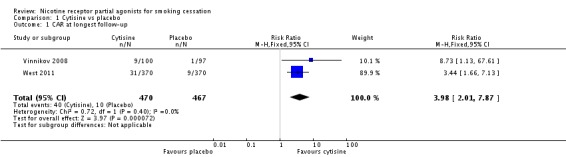

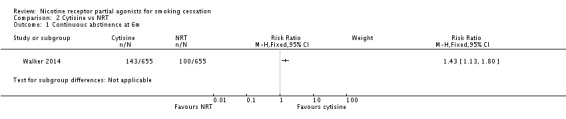

Two trials of cytisine (937 people) found that more participants taking cytisine stopped smoking compared with placebo at longest follow‐up, with a pooled risk ratio (RR) of 3.98 (95% confidence interval (CI) 2.01 to 7.87; low‐quality evidence). One recent trial comparing cytisine with NRT in 1310 people found a benefit for cytisine at six months (RR 1.43, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.80).

One trial of dianicline (602 people) failed to find evidence that it was effective (RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.75). This drug is no longer in development.

We identified 39 trials that tested varenicline, 27 of which contributed to the primary analysis (varenicline versus placebo). Five of these trials also included a bupropion treatment arm. Eight trials compared varenicline with nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). Nine studies tested variations in varenicline dosage, and 13 tested usage in disease‐specific subgroups of patients. The included studies covered 25,290 participants, 11,801 of whom used varenicline.

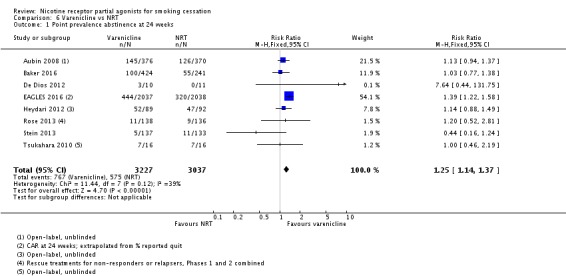

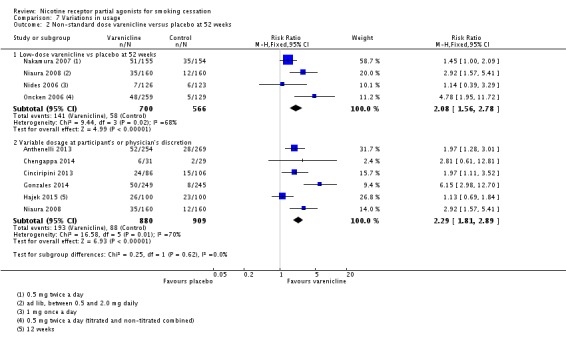

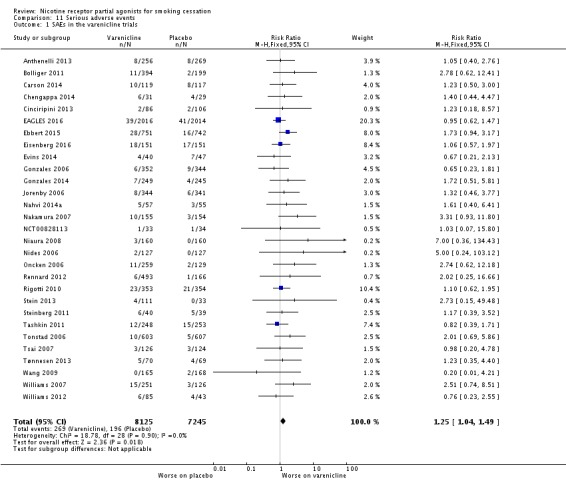

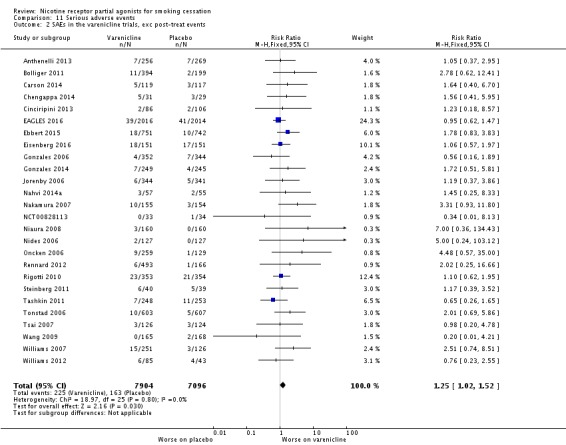

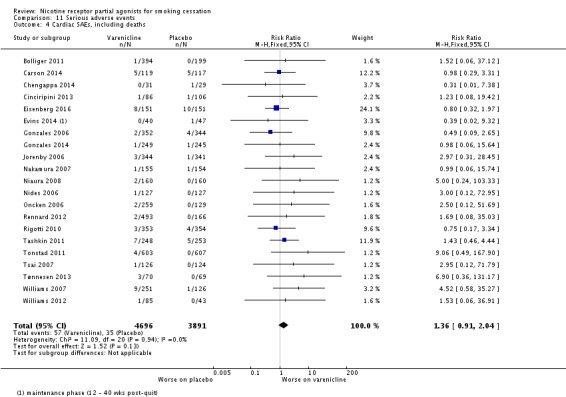

The pooled RR for continuous or sustained abstinence at six months or longer for varenicline at standard dosage versus placebo was 2.24 (95% CI 2.06 to 2.43; 27 trials, 12,625 people; high‐quality evidence). Varenicline at lower or variable doses was also shown to be effective, with an RR of 2.08 (95% CI 1.56 to 2.78; 4 trials, 1266 people). The pooled RR for varenicline versus bupropion at six months was 1.39 (95% CI 1.25 to 1.54; 5 trials, 5877 people; high‐quality evidence). The RR for varenicline versus NRT for abstinence at 24 weeks was 1.25 (95% CI 1.14 to 1.37; 8 trials, 6264 people; moderate‐quality evidence). Four trials which tested the use of varenicline beyond the 12‐week standard regimen found the drug to be well‐tolerated during long‐term use. The number needed to treat with varenicline for an additional beneficial outcome, based on the weighted mean control rate, is 11 (95% CI 9 to 13). The most commonly reported adverse effect of varenicline was nausea, which was mostly at mild to moderate levels and usually subsided over time. Our analysis of reported serious adverse events occurring during or after active treatment suggests there may be a 25% increase in the chance of SAEs among people using varenicline (RR 1.25; 95% CI 1.04 to 1.49; 29 trials, 15,370 people; high‐quality evidence). These events include comorbidities such as infections, cancers and injuries, and most were considered by the trialists to be unrelated to the treatments. There is also evidence of higher losses to follow‐up in the control groups compared with the intervention groups, leading to a likely underascertainment of the true rate of SAEs among the controls. Early concerns about a possible association between varenicline and depressed mood, agitation, and suicidal behaviour or ideation led to the addition of a boxed warning to the labelling in 2008. However, subsequent observational cohort studies and meta‐analyses have not confirmed these fears, and the findings of the EAGLES trial do not support a causal link between varenicline and neuropsychiatric disorders, including suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviour. The evidence is not conclusive, however, in people with past or current psychiatric disorders. Concerns have also been raised that varenicline may slightly increase cardiovascular events in people already at increased risk of those illnesses. Current evidence neither supports nor refutes such an association, but we await the findings of the CATS trial, which should establish whether or not this is a valid concern.

Authors' conclusions

Cytisine increases the chances of quitting, although absolute quit rates were modest in two recent trials. Varenicline at standard dose increased the chances of successful long‐term smoking cessation between two‐ and three‐fold compared with pharmacologically unassisted quit attempts. Lower dose regimens also conferred benefits for cessation, while reducing the incidence of adverse events. More participants quit successfully with varenicline than with bupropion or with NRT. Limited evidence suggests that varenicline may have a role to play in relapse prevention. The most frequently recorded adverse effect of varenicline is nausea, but mostly at mild to moderate levels and tending to subside over time. Early reports of possible links to suicidal ideation and behaviour have not been confirmed by current research.

Future trials of cytisine may test extended regimens and more intensive behavioural support.

Keywords: Humans; Alkaloids; Alkaloids/adverse effects; Alkaloids/therapeutic use; Azepines; Azepines/adverse effects; Azepines/therapeutic use; Azocines; Azocines/adverse effects; Azocines/therapeutic use; Benzazepines; Benzazepines/adverse effects; Benzazepines/therapeutic use; Bupropion; Bupropion/therapeutic use; Counseling; Counseling/methods; Heterocyclic Compounds, 4 or More Rings; Heterocyclic Compounds, 4 or More Rings/adverse effects; Heterocyclic Compounds, 4 or More Rings/therapeutic use; Nicotine; Nicotine/adverse effects; Nicotine/antagonists & inhibitors; Nicotinic Agonists; Nicotinic Agonists/adverse effects; Nicotinic Agonists/therapeutic use; Quinolizines; Quinolizines/adverse effects; Quinolizines/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Smoking; Smoking/drug therapy; Smoking Cessation; Smoking Cessation/methods; Substance Withdrawal Syndrome; Substance Withdrawal Syndrome/prevention & control; Varenicline; Varenicline/therapeutic use

Can nicotine receptor partial agonists, including cytisine and varenicline, help people to stop smoking?

Background

When people stop smoking they experience cravings to smoke and unpleasant mood changes. Nicotine receptor partial agonists aim to reduce these withdrawal symptoms and the pleasure people usually experience when they smoke. The most widely‐available treatment in this drug type is varenicline, which is available world‐wide as an aid for quitting smoking. Cytisine is a similar medication, but is only available in Central and Eastern European countries and through internet sales.

Study characteristics

We searched for randomised controlled trials testing varenicline, cytisine or dianicline. We found 39 studies of varenicline compared to placebo, bupropion or nicotine patches. We also found four trials of cytisine, one of which compared it to nicotine replacement therapy. We include one trial of dianicline, which is no longer in development, and so not available to use as a quitting aid. To be included, trials had to report quit rates at least six months from the start of treatment. We preferred the strictest available definition of quitting, and results which had been biochemically confirmed by testing blood or bodily fluids.We conducted full searches up to May 2015, although we have also included several key trials published after that date.

Key findings

From the information we found (27 trials, 12,625 people), varenicline at standard dose more than doubled the chances of quitting compared with placebo. Low‐dose varenicline (four trials, 1266 people) roughly doubled the chances of quitting, and reduced the number and severity of side effects. The number of people stopping smoking with varenicline was higher than with bupropion (five trials, 5877 people) or with NRT (eight trials, 6264 people). Based on the evidence so far, we can calculate that varenicline delivers one extra successful quitter for every 11 people treated, compared with smokers trying to quit without varenicline.

The most common side effect of varenicline is nausea, but this is mostly at mild or moderate levels and usually clears over time. People taking varenicline appear to have about a 25% increased chance of a serious adverse event, although these include many which are unrelated to the treatment. We also note that more people were lost from the control groups than from the varenicline groups by the end of the trials, which may mean that the count of events in the control groups is lower than it should be. After varenicline became available to use, there were concerns that it could be linked with an increase in depressed mood, agitation, or suicidal thinking and behaviour in some smokers. However, the latest evidence does not support a link between varenicline and these disorders, although people with past or current psychiatric illness may be at slightly higher risk. There have also been concerns that varenicline may slightly increase heart and circulatory problems in people already at increased risk of these illnesses. The evidence is currently unclear whether or not they are caused or made worse by varenicline, but we should have clearer answers to these questions when a further study is published later this year.

Quality of the evidence

The varenicline studies were generally of high quality, providing evidence that we consider to be reliable and robust. We rate the quality of the evidence comparing varenicline with NRT as moderate quality (we are reasonably confident of the stability of the evidence), since in some of them the participants knew which treatment they were receiving (i.e. non‐blinded open‐label trials). We judge the evidence from the cytsine trials to be of low quality (we have limited confidence in the evidence), as there are only two trials, with relatively low numbers included.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation

| Varenicline versus placebo or other first‐line treatments for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: Individuals who smoke tobacco Setting: Varied Intervention: Varenicline Comparison: Varied controls | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Corresponding risk with varenicline | |||||

| Varenicline vs placebo: continuous/sustained abstinence at longest follow‐up (24+ weeks) | Study population (where risk refers to quitters) | RR 2.24 (2.06 to 2.43) | 12,625 (27 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH 1, 2 | ||

| 111 per 1000 | 250 per 1000 (230 to 271) | |||||

| Varenicline vs bupropion: continuous/sustained abstinence (24 weeks) | Study population (where risk refers to quitters) | RR 1.39 (1.25 to 1.54) | 5877 (5 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ||

| 171 per 1000 | 238 per 1000 (214 to 264) | |||||

| Varenicline vs NRT: point prevalence abstinence (24 weeks) | Study population (where risk refers to quitters) | RR 1.25 (1.14 to 1.37) | 6264 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 3 | ||

| 189 per 1000 | 237 per 1000 (216 to 259) |

|||||

| Varenicline vs placebo: number of participants reporting SAEs in duration of trials (trials reporting no events in either group excluded) | Study population (where risk refers to SAEs) | RR 1.25 (1.04 to 1.49) | 15,370 (29 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ||

| 30 per 1000 | 39 per 1000 (32 to 48) | |||||

| Varenicline vs placebo: number of participants reporting cardiac SAEs, including deaths, in duration of trials | Study population (where risk refers to SAEs) | RR 1.36 (0.91 to 2.04) |

8587 (21 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 4 | ||

| 9 per 1,000 | 12 per 1,000 (8 to 17) |

|||||

| Varenicline vs placebo: number of participants reporting nausea in duration of trials | Study population (where risk refers to SAEs) | RR 3.27 (3.00 to 3.55) |

14963 (32 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ||

| 85 per 1,000 | 277 per 1,000 (254 to 301) |

|||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).The assumed risk in the comparison group is calculated as the median risk in control groups. CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; SAEs: Serious adverse events | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

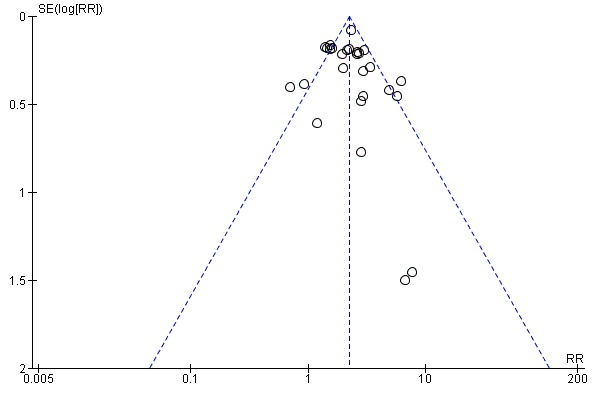

1Moderate heterogeneity detected, however all but two studies showed positive effect of varenicline, so did not downgrade on this basis.

2Lack of smaller trials with negative findings suggests possible publication bias. However, earliest studies reported 2006. We are reasonably confident that licensing and subsequent trials have been registered online in clinical trials registries. Thus absence of negative studies may be marker of sustained efficacy rather than suppression or selective management of data.

3Downgraded once as three of the eight studies were rated at high risk of bias due to using an open‐label design.

4Downgraded once due to imprecision; CIs do not rule out an increase in risk

Summary of findings 2.

Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation

| Cytisine versus placebo for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: Individuals who smoke tobacco Setting: Varied Intervention: Cytisine Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Corresponding risk with Cytisine | |||||

| Cytisine vs placebo: continuous abstinence at longest follow‐up (24+ weeks) | Study population (where risk refers to quitters) | RR 3.98 (2.01 to 7.87) | 937 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | ||

| 21 per 1000 | 85 per 1000 (43 to 169) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).The assumed risk in the comparison group is calculated as the median risk in control groups. CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1Imprecision rated 'very serious' (downgraded two levels on this basis) as only two studies, and fewer than 300 events in each arm.

Background

Smoking is the main preventable cause worldwide of morbidity and premature death. Based on data from 2004, 12% of all deaths globally among adults aged 30 years and over were attributable to tobacco, with 5 million adults dying due directly to tobacco use (WHO 2012). The list of illnesses known to be linked to smoking includes cancers of the cervix, pancreas, kidneys and stomach, aortic aneurysms, acute myeloid leukaemia, cataracts, pneumonia, and gum disease. These are in addition to the long‐established links between tobacco use and such illnesses as lung cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and emphysema, and with prematurity, sudden infant death syndrome and low birth weight in the babies of maternal smokers (Surgeon General 2004). There is a growing understanding of the neurochemical basis of nicotine addiction (Fagerström 2006). There is strong evidence that dependence upon nicotine reflects the effects of the drug at neuronal nicotinic receptors in the brain (Benowitz 1999; Hogg 2007; Picciotto 1999). More recent studies have explored the potential of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) as targets for a variety of therapeutic interventions (Hogg 2007). It is thought that the addictive properties of nicotine are mediated mainly through its action as an agonist at α4β2nAChRs, which stimulates the release of dopamine (Coe 2005). Pharmacotherapies to aid smoking cessation have been developed which exploit this mechanism, by acting as nicotine receptor partial agonists.

Cytisine

Cytisine was developed as a treatment for tobacco dependence in Bulgaria in the 1960s, and is available in some eastern and central European countries and through internet sales, under the trade name of Tabex (Foulds 2004; Tutka 2005; Tutka 2006). Its manufacturers, Sopharma Pharmaceuticals, developed their phytoproduct from the plant Cytisus Laburnum L. (Golden Rain). Although cytisine (Tabex) is not licensed for use as a smoking cessation aid across most countries outside Eastern Europe (Walker 2014), studies by Vinnikov 2008 and West 2011 have highlighted the potential of this drug, especially in countries with lower average incomes and where smoking cessation programmes are not supported by insurance plans or by a national health service. In many regions, it may be considerably cheaper to continue smoking than to embark upon a course of pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation. West 2011 reports that a pack of cigarettes in China costs between 15¢ and 73¢, compared with a course of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) (USD 230), bupropion (USD 123), or varenicline (USD 327). Similarly, a pack of 20 cigarettes in India costs around USD 1.10, or 5¢ for a pack of bidis, compared with USD 150 for a course of NRT, USD 100 for bupropion and USD 200 for varenicline. Tabex is currently available in Poland for the equivalent of USD 15 for a course of treatment, and in Russia for the equivalent of USD 6 as an over‐the‐counter medication. There is also heightened interest and activity in cytisine in New Zealand, where it is found in the seeds of the native Kowhai tree, widely used in traditional Māori healing (Thompson‐Evans 2011). The current update adds a large single‐blind randomised non‐inferiority trial comparing cytisine with NRT, conducted in New Zealand between 2011 and 2013 (Walker 2014).

Dianicline

In 2006, Sanofi‐Aventis registered two trials of dianicline, their version of a nicotine receptor partial agonist (Tonstad 2011; Ameridian 2007). However, unfavourable results have led to the withdrawal of this drug from further development (Kirchhoff 2009). We have been unable to locate results for the AMERIDIAN trial, and present only the EURODIAN trial report in this review.

Varenicline

Varenicline was developed by Pfizer Inc to counteract the effects of nicotine on the nAChRs. The drug was based on the naturally‐occurring alkaloid compound cytisine described above, which had been shown to be an effective partial agonist for α4β2 receptors (Papke 1994; Slater 2003).

Varenicline was developed in 1997 (Coe 2005), and is described as a selective nicotinic receptor partial agonist. It was designed to selectively activate the α4β2nAChR, mimicking the action of nicotine and causing a moderate and sustained release of mesolimbic dopamine (Sands 2005). This, it was suggested, should counteract withdrawal symptoms consequent upon low dopamine release during smoking cessation attempts. However, because it is a partial agonist at these receptors, it elicits some dopamine overflow, but not the substantial increases evoked by nicotine. Perhaps more importantly, it blocks the effects of a subsequent nicotine challenge on dopamine release from the mesolimbic neurones thought pivotal to the development of nicotine dependence (Coe 2005). Although varenicline has been shown to be a partial agonist at heteromeric neuronal nicotine receptors, there is now evidence that it may also be a full agonist at the homomeric α7 receptor (Mihalak 2006).

Multicentre trials of varenicline have been conducted or are currently underway in the USA, Canada, Latin America, Europe, Australia, the Middle East and the Far East. There have also been studies in specific patient groups, including the following conditions: cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, drug or alcohol dependence, head and neck cancers, HIV infection, bipolar disorders, depression, schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders.

Varenicline was approved as a prescription‐only aid to smoking cessation in 2006 by the American Food and Drug Administration under the trade name Chantix, and by the European Medicines Evaluation Agency under the trade name Champix. In July 2007 it was approved by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) for prescribing by the UK National Heath Service (ASH 2006; NICE 2007). Post‐marketing surveillance has raised subsequent concerns about possible links between varenicline and major health risks, including suicidal ideation and behaviour, depression, and serious adverse cardiovascular events (FDA 2008). We consider these findings in the Discussion section of this review, and in our meta‐analyses.

Objectives

To review the efficacy of nicotine receptor partial agonists, including varenicline and cytisine, for smoking cessation.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials.

Types of participants

Adult smokers. Trials which target users of smokeless tobacco are not included in this review, but are listed among the Excluded Studies. Interventions for smokeless tobacco use cessation are covered in a companion review (Ebbert 2011).

Types of interventions

Selective nicotine receptor partial agonists, including cytisine, dianicline and varenicline, or any other in this class of drug as they reach Phase 3 trial stage. The efficacy of lobeline is covered in an earlier Cochrane review (Stead 2003).

For this update, and in anticipation of current ongoing trials reaching publication, we have extended the range of analyses to cover the following intervention types and subgroups:

I. Varenicline versus other pharmacotherapies:

Varenicline versus placebo

Varenicline versus bupropion

Varenicline versus NRT

Varenicline versus mecamylamine

Combination treatments (e.g. varenicline + NRT) versus single‐therapy treatment, where the addition of varenicline is the intervention being tested

Varenicline tablets versus other formulations (e.g. patch, in solution)

II. Variations in usage:

Flexible quit dates

Variable dosages

Preloading (before TQD)

Reducing to quit

Maintenance therapy (relapse prevention)

Harm reduction

III. Specific patient groups:

Cardiovascular disease (CVD)

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Asthma

Schizophrenia/bipolar/psychiatric disorder

Depression

Substance use disorder/methadone‐maintained

Alcohol‐dependent smokers

HIV

Diabetes

Head and neck cancer

Varenicline in pregnancy

Long‐term use of NRT

IV. Settings/subgroups:

Hospital inpatients/perioperative patients

Smokers who have previously failed to quit on varenicline or NRT or bupropion

Light or heavy smokers

Varenicline by gender

Varenicline in ethnic groups

We have not considered for inclusion any trials of varenicline used for conditions other than smoking cessation, such as alcoholism, cocaine dependence, Parkinson's disease, spinocerebellar degeneration, etc.

Types of outcome measures

A minimum of six months abstinence is the primary outcome measure. We have used sustained cessation rates in preference to point prevalence, and we have preferred biochemically verified rates to rates based on self report of quitting. In analysis, we treat participants lost to follow‐up as continuing smokers. We have recorded any adverse effects of treatment.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the Tobacco Addiction Review Group specialised register for trials, using the terms ('cytisine' or 'Tabex' or 'dianicline' or 'varenicline' or 'nicotine receptor partial agonist') in the title or abstract, or as keywords. This register has been developed from electronic searching of MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO, together with handsearching of specialist journals, conference proceedings and reference lists of previous trials and overviews. The most recent search of the Register was in May 2015, and included reports of trials indexed in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL), issue 5, 2015; MEDLINE (via OVID) to update 20150501; EMBASE (via OVID) to week 201519; PsycINFO (via OVID) to update 20150506. See the Tobacco Addiction Group Module for details of the search strategies for these databases.

We also searched UK and US online clinical trials registers for ongoing and recently completed trials. Trials which may be candidates for inclusion (i.e. RCTs of smoking cessation interventions using a nicotine receptor partial agonist with a minimum follow‐up of six months), and for which results are not yet available, are listed in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table. We contacted the authors of ongoing studies of varenicline and cytisine where necessary.

We made a strategic decision to delay publication of this update until we could access the findings of the Pfizer EAGLES 2016 trial (NCT014569360) in April 2016. Although we did not conduct full‐scale top‐up searches during this waiting period, we checked the status of all ongoing studies known to us, and identified published results for six of them: two were journal articles (Baker 2016; Eisenberg 2016), now included studies, and four had posted their results on the ClinicalTrials.gov database; we have added two of the trials (NCT00828113; NCT01347112) to the included studies, and the other two (NCT01308736; NCT01806779) to the excluded studies.

Data collection and analysis

We checked the abstracts of studies generated by the search strategy for relevance, and acquired full reports of any trials that might be suitable for the review. One author (KC) extracted the data, and a second author (NLH) checked them. We resolved any discrepancies by mutual consent, or by recourse to a third author (TL). Studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table, with reasons for their exclusion.

Studies were evaluated on the basis of the quality of the randomisation procedure and allocation concealment, as described in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011). The following information about each trial, where it is available, is reported in the table Characteristics of included studies:

Country and setting (e.g. primary care, community, hospital outpatient/inpatient)

Method of selection of participants

Definition of smoker used

Methods of randomisation and allocation, and blinding of trialists, participants and assessors

Demographic characteristics of participants (e.g. average age, sex, average cigarettes/day)

Intervention and control description (dose, provider, duration, number of visits, etc.)

Outcomes including definition of abstinence used, and biochemical validation of cessation

Proportion of participants with follow‐up data

Any adverse events

Sources of funding

Studies in the Characteristics of included studies table are grouped by the type of treatment being tested (cytisine, dianicline, varenicline). Quit rates are calculated based on the numbers of people randomised to an intervention, and excluding any deaths or untraceable moves, in accordance with the Russell Standard (West 2005). We regard those who drop out or are lost to follow‐up as continuing smokers. We have noted any deaths and adverse events in the results section. Effects are expressed as risk ratios ((number of events in intervention condition/intervention denominator)/(number of events in control condition/control denominator)). For cessation a risk ratio greater than 1 indicates that more people are quitting in the intervention condition. For adverse events, a risk ratio greater than 1 indicates that more people experience adverse events in the intervention condition.

Where appropriate, we have conducted meta‐analyses of the included studies, using the Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect model, provided that there was no significant heterogeneity. We assessed statistical heterogeneity between trials using the I² statistic which describes the percentage of total variation between studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance (Higgins 2003). Values over 50% suggest moderate heterogeneity, and values over 75% substantial heterogeneity.

For studies of disease‐specific patients (section III) and for patients in different settings (section IV), we have conducted and reported sensitivity analyses, treating them as subgroups of the main analyses and testing for subgroup differences.

For this update, we have produced 'Summary of findings' tables covering the main outcomes of smoking abstinence for varenicline versus placebo, varenicline versus bupropion, varenicline versus NRT (all in Table 1), and cytisine versus placebo (Table 2); and incidence of serious adverse events for the comparison of varenicline versus placebo. Our grading decisions are based on the five GRADE considerations: study limitations in design or execution (risks of bias), inconsistency of results, indirectness of evidence, imprecision of results, and publication bias. Evidence from studies is rated as high quality (i.e. we are very confident of the findings), through moderate, low, and very low quality (i.e. the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect).

We include in this review the Tobacco Addiction Group glossary of tobacco‐specific terms (Appendix 1).

Results

Description of studies

Included studies

Full details of the included studies are given in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

For this update, we now have 44 trials (previously 24) which met our inclusion criteria. Four trials (Scharfenberg 1971; Vinnikov 2008; Walker 2014; West 2011) evaluated cytisine (Tabex) for smoking cessation, covering 3461 participants, 2102 of whom took cytisine. One trial of 602 smokers, 300 of whom took the active treatment, tested the Sanofi‐Aventis drug dianicline for smoking cessation (Tonstad 2011). The remaining 39 trials tested varenicline in a variety of populations and settings, and against various comparators. Two trials, formerly classified as 'Ongoing studies' have now posted their findings on the www.ClinicalTrials.gov website, and we now treat them as included studies (NCT00828113; NCT01347112), albeit with limited information on design and findings. The trials cover more than 25,200 participants, 11,801 of whom took varenicline (see Appendix 2).

Nine studies which we originally treated as excluded are now classified as included studies, so that they can contribute data to the meta‐analyses for neuropsychiatric adverse events. These studies are flagged with an asterisk in the study ID, indicating that they do not contribute to the efficacy findings (Brandon 2011*; Ebbert 2011*; Faessel 2009*; Fagerström 2010*; Garza 2011*; Hughes 2011*; McClure 2013* NCT00944554; Meszaros 2013*; Mitchell 2012*). We have not completed Characteristics of included studies tables or 'Risk of bias' assessments for these nine studies, but have recorded our judgements on why they are not eligible to be included in the efficacy findings.

Cytisine

Cytisine versus placebo was tested as a cessation aid in Germany (Scharfenberg 1971), in Kyrgyzstan (Vinnikov 2008), and in Poland (West 2011). Scharfenberg 1971 was set in a smoking cessation clinic in what was then East Germany, Vinnikov 2008 was set in a Kyrgyz mining company, and West 2011 in a Warsaw smoking cessation clinic. A recent New Zealand non‐inferiority trial (Walker 2014) compared cytisine to NRT in a population of smokers contacting a national smoking quitline. The trials used 1.5 mg Tabex tablets over a 20‐day (Scharfenberg 1971) or 25‐day (Vinnikov 2008; Walker 2014; West 2011) treatment period, with behavioural support kept to a minimum in order to reduce programme costs. Vinnikov 2008 and Walker 2014 assessed their participants to six months, West 2011 to 12 months, and Scharfenberg 1971 to two years. Both Vinnikov 2008 and West 2011 verified claims of abstinence by testing expired carbon monoxide (CO) levels, while the remaining two trials relied upon self report without biochemical validation.

Dianicline

The dianicline trial (Tonstad 2011) was set in 22 sites across six European countries. Dianicline was administered as a 40 mg tablet twice a day for seven weeks, with brief counselling at each contact. Final follow‐up of the participants was at 26 weeks, with claims of abstinence verified by expired CO and by plasma cotinine samples.

Varenicline

Study design

Thirty‐four studies were double‐blinded randomised trials; the remaining five were open‐label. Three of the open‐label trials compared varenicline with NRT (Aubin 2008; Baker 2016; Tsukahara 2010), one compared varenicline with NRT and with placebo (Heydari 2012), and one compared varenicline plus counselling with counselling alone (Carson 2014 (formerly Smith 2012)).

Setting

Seventeen studies were set in the USA, two in Japan, two in Denmark, one each in Australia, Canada, Iran and the UK, one in both Taiwan and Korea, one in both China and Singapore, two in North America (USA and Canada), and ten in multiple countries. The trials were conducted in smoking cessation clinics, hospitals, universities and other research centres.

Participants

Participants in the majority of the trials were adult smokers, willing to make a quit attempt (Aubin 2008; Baker 2016; Bolliger 2011; Cinciripini 2013; EAGLES 2016; Eisenberg 2016; Gonzales 2006; Gonzales 2014; Heydari 2012; Jorenby 2006; Nakamura 2007; NCT01347112; Niaura 2008; Niaura 2008; Nides 2006; Oncken 2006; Rennard 2012; Tsai 2007; Tsukahara 2010; Wang 2009; Williams 2007). Several trials were conducted in clinical subgroups, including hospital inpatients (Carson 2014; Steinberg 2011; Wong 2012), and disease‐specific patient groups (CVD: Rigotti 2010; acute coronary syndrome Eisenberg 2016; COPD: Tashkin 2011; asthma: Westergaard 2015; substance use disorder: Nahvi 2014a; Stein 2013; alcohol abuse: NCT01347112; depression: Anthenelli 2013; bipolar/schizophrenia; schizoaffective disorder: Chengappa 2014; Evins 2014; Williams 2012). EAGLES 2016 enrolled two cohorts of adult smokers with and without histories of psychiatric disorders, including primary affective disorders (70%), anxiety disorders (19%), psychotic disorders (9.5%) and personality disorders (0.6%). Two trials targeted subgroups of smokers who were failing to respond to smoking cessation pharmacotherapies, either by increasing the dosage (Hajek 2015) or by switching to different medications (Rose 2013). Three studies focused on relapse prevention in successful quitters (NCT00828113; Tonstad 2006), or in people with schizophrenia who had successfully quit (Evins 2014). De Dios 2012 tested varenicline in Latino light smokers, and Ebbert 2015 in adult smokers unwilling to quit abruptly but prepared to reduce their smoking as a run‐up to quitting completely. Tønnesen 2013 tested varenicline as an aid to weaning ex‐smokers off extended use of NRT.

Interventions

Thirty‐three of the 39 trials used the standard 12‐week regimen of varenicline, routinely titrating the first week up to the recommended daily dose of 1 mg twice a day. Three trials (Nakamura 2007; Nides 2006; Oncken 2006) compared different dosage arms of varenicline against a placebo arm. One trial in non‐responders regulated dosage up to the target quit date (day 21) to a maximum of 5 mg a day (Hajek 2015), and another allowed participants to regulate their own dosage throughout the treatment phase (Niaura 2008). NCT00828113 is a randomised trial comparing extended (52‐week) and standard (12‐week) courses of varenicline.

Of the eight trials that used NRT as a comparator condition, five (Aubin 2008; Baker 2016; De Dios 2012; EAGLES 2016; Rose 2013) provided a 12‐week course, reducing the dosage as a weaning process, while two trials (Heydari 2012; Tsukahara 2010) provided an eight‐week course, with only the Tsukahara 2010 trial progressively reducing the dosage to the end of treatment. Stein 2013 gave a 24‐week course of NRT, tailored to the level of nicotine dependency, and matched to the duration of the placebo and varenicline arms of the trial.

The five trials which used bupropion all supplied the standard regimen of 150 mg twice a day, four of them for 12 weeks (Cinciripini 2013; EAGLES 2016; Gonzales 2006; Jorenby 2006) and Nides 2006 for seven weeks.

Comparisons

Twenty‐six RCTs compared varenicline to an identical placebo regimen (Anthenelli 2013; Bolliger 2011; Chengappa 2014; EAGLES 2016; Ebbert 2015; Eisenberg 2016; Evins 2014; Gonzales 2014; Hajek 2015; Nahvi 2014a; Nakamura 2007; NCT01347112; Niaura 2008; Oncken 2006; Rennard 2012; Rigotti 2010; Steinberg 2011; Tashkin 2011; Tonstad 2006; Tonstad 2011; Tsai 2007; Wang 2009; Westergaard 2015; Williams 2007; Williams 2012; Wong 2012); all these trials used the standard 12‐week course of treatment, apart from Ebbert 2015 (24 weeks, 'reduce to quit'), Evins 2014 (40 weeks, relapse prevention) and Williams 2007 (52 weeks, a safety trial). Four trials (Aubin 2008; Baker 2016; Rose 2013; Tsukahara 2010) used NRT as the comparator rather than a placebo, while three more trials (De Dios 2012; Heydari 2012; Stein 2013) used both NRT and placebo as comparator conditions, in a three‐arm study design. EAGLES 2016 was a four‐arm triple‐dummy trial, comparing varenicline, bupropion and NRT with a placebo. Four trials (Cinciripini 2013; Gonzales 2006; Jorenby 2006; Nides 2006) compared varenicline with bupropion and with placebo. One trial (Carson 2014) compared varenicline plus quitline counselling to quitline counselling alone.

Outcomes

As a condition of inclusion, all the trials reported cessation at least six months from the start of the intervention. Seventeen of 39 studies reported longest follow‐up at six months (point prevalence or continuous abstinence) (Bolliger 2011; Chengappa 2014; Cinciripini 2013; De Dios 2012; EAGLES 2016; Eisenberg 2016; Nahvi 2014a; NCT01347112; Rennard 2012; Rose 2013; Stein 2013; Steinberg 2011; Tsai 2007; Tsukahara 2010; Wang 2009; Westergaard 2015; Williams 2012), and 20 studies to 12 months. Hajek 2015, relevant for the exploration of dose variability, reported abstinence only to 12 weeks, and is not included in the main efficacy findings. Evins 2014 followed its participants until week 64, as part of a relapse prevention initiative.

All the trials except one (NCT01347112) used biochemical verification of abstinence by expired CO, at cut‐offs ranging from 5 to 10 ppm, at one or more time points. Baker 2016 validated outcomes at both 9 ppm and 5 ppm cut‐off levels. Heydari 2012 and Wong 2012 did not report their cut‐offs. Carson 2014 tested "a random sub‐set of subjects" (51/103 quitters). Five trials (Cinciripini 2013; De Dios 2012; Stein 2013; Tønnesen 2013; Wong 2012) also used salivary or urinary cotinine testing to confirm abstinence claims.

Excluded studies

Eight of the excluded studies tested cytisine (Granatowicz 1976; Kempe 1967; Maliszewski 1972; Metelitsa 1987; Monova 2004; Ostrovskaia 1994; Paun 1968; Schmidt 1974), and the remaining 48 tested varenicline, but did not meet our eligibility criteria to be treated as an included study.

The excluded studies are briefly described, with reasons for exclusion, in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables. Seven of the excluded studies (Ebbert 2014; Hajek 2013; Hoogsteder 2014; Koegelenberg 2014; NCT01806779; Ramon 2014; Rose 2014) administered varenicline to all participants, and tested the addition of another pharmacotherapy (nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, or nicotine vaccine). Since varenicline was not primarily the intervention being tested, the findings of these trials are covered in the reviews which address the relevant adjunctive treatments. Swan 2010, which we had classified as an included study in the 2012 update, is now an excluded study, as all the participants received varenicline, and the intervention being tested was the addition and relative merits of internet‐ and telephone‐based counselling. Two trials (NCT01308736; NCT01806779), formerly treated as 'Ongoing studies', have now posted their findings on the www.ClinicalTrials.gov website, and we now report them as excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

Among the cytisine trials, we rated Vinnikov 2008, Walker 2014 and West 2011 as being at low risk of bias in their randomisation and allocation procedures; Scharfenberg 1971 gave no details about these, and was therefore rated as unclear. We rated Walker 2014 at high risk of bias for a lack of blinding of participants and personnel. This study may also have been at risk of bias for providing cytisine free of charge but NRT at a cost of NZD 3 per item. Although Vinnikov 2008 invokes the Russell Standard criteria (West 2005) in support of the conduct of their trial, they excluded 26 participants who took no medication from the denominator; we have reinstated them for our meta‐analyses, in order to present an intention‐to‐treat estimate, i.e. all people randomised, excluding only those who died or who moved away. Of the 39 varenicline trials, 23 reported randomisation and allocation procedures in sufficient detail to be assessed as being at minimal risk in their attempts to control selection bias. Fifteen trials (Chengappa 2014; Cinciripini 2013; De Dios 2012; Heydari 2012; NCT00828113; NCT01347112; Oncken 2006; Rose 2013; Stein 2013; Tashkin 2011; Tsukahara 2010; Wang 2009; Westergaard 2015; Williams 2007; Williams 2012) gave insufficient information for this to be confirmed. A sensitivity analysis removing these trials made no difference to the findings. None of the trials reported any assessment of the integrity of the double‐blinding procedure. For the relapse prevention trials (Evins 2014; NCT00828113; Tonstad 2006), the integrity of the double‐blind phase may be questionable, since all randomised participants had successfully used varenicline during the open‐label phase.

All except eight of the included studies reported prolonged, sustained or continuous abstinence as their most rigorous estimate of efficacy; De Dios 2012; Heydari 2012; Nahvi 2014a; NCT00828113; Westergaard 2015; Williams 2007; Williams 2012; and Wong 2012 all reported only point prevalence abstinence. Steinberg 2011 used repeated point prevalence at 4, 12 and 24 weeks, which we have treated as sustained abstinence for the purposes of our meta‐analyses. 'Continuous abstinence' as defined in the remaining trials excluded the first eight weeks of treatment, and could more accurately be termed 'prolonged abstinence' (Hughes 2003).

Aubin 2008 was an unblinded open‐label trial, which may have led to the differential drop‐out rates after randomisation, with nine participants assigned to nicotine patch declining to take part compared with two in the varenicline group. We rated four open‐label trials of NRT versus varenicline (Aubin 2008; Baker 2016; Heydari 2012; Tsukahara 2010) at high risk of bias for being unblinded. Nakamura 2007 was assessed as being at high risk of selective reporting bias, since they reported continuous abstinence rates for all participants, but demographic information, craving and withdrawal measures for the highly nicotine‐dependent smokers only. Cinciripini 2013 reported changing interventions (from nortriptyline to varenicline) three months into their study, but found no differences between the varenicline and nortriptyline cohorts and therefore combined them for analysis. Heydari 2012 used an eight‐week course of varenicline (presumably to match the standard NRT regimen), which might be expected to have compromised its efficacy.

Two trials which posted their results on the www.ClinicalTrials.gov website are rated at high risk of bias for attrition and losses to follow‐up. NCT00828113, comparing long‐term and standard doses of varenicline, lost 60% from each of the groups by twelve‐month follow‐up, while NCT01347112, a small study of alcohol‐dependent smokers using varenicline to quit, lost 25% from the varenicline group and 71% from the placebo group at 24 weeks. This study also relied upon self report, rather than biochemical validation of abstinence.

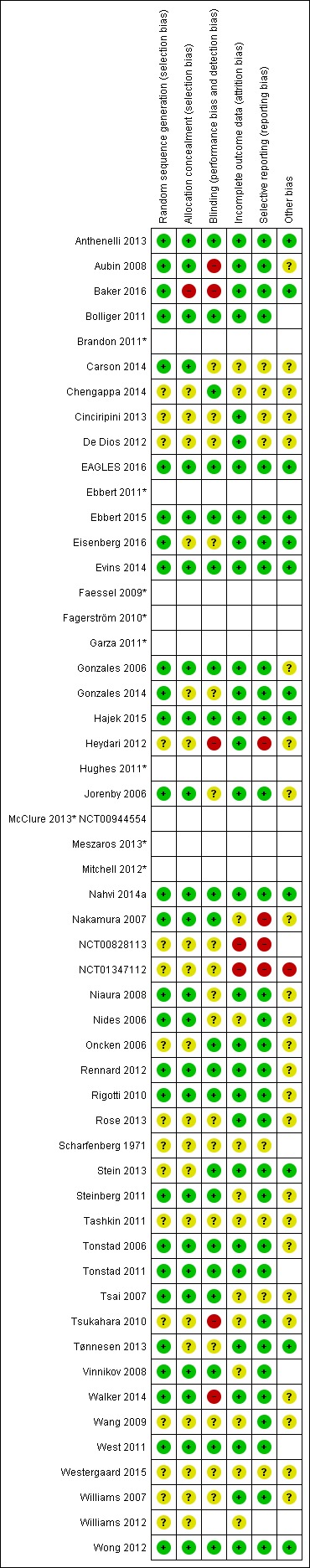

Our judgements on the risks of bias of all the included studies are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

1. Cessation

Cytisine

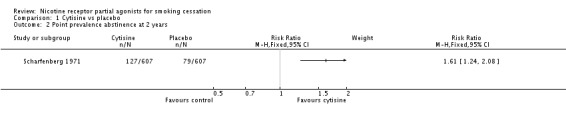

We pooled the findings of two cytisine trials, covering 937 participants, 470 of whom took the active drug. Both trials reported continuous abstinence rates at longest follow‐up (24 weeks in Vinnikov 2008 and 52 weeks in West 2011), delivering an RR of 3.98 (95% CI 2.01 to 7.87; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.1). We have not combined these recent trials with Scharfenberg 1971, as the design and conduct of the latter is of indeterminate quality, using self‐reported point prevalence abstinence and without biochemical verification of its results. A sensitivity analysis combining the three trials increased the I² statistic from 0% to 68%, indicating substantial heterogeneity between the older study and the recent ones. The RR for Scharfenberg 1971 at two‐year follow‐up was 1.61 (95% CI 1.24 to 2.08; Analysis 1.2), and at six months 1.91 (95% CI 1.53 to 2.37; analysis not shown).

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Cytisine vs placebo, Outcome 1 CAR at longest follow‐up.

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Cytisine vs placebo, Outcome 2 Point prevalence abstinence at 2 years.

The largest cytisine trial (Walker 2014) compared it with NRT, and reported non‐verified continuous abstinence at six months. Although this study (in 1360 participants) was designed as a test of non‐inferiority, it demonstrated a significant benefit for cytisine over NRT, with a RR of 1.43 (95% CI 1.13 to 1.80; Analysis 2.1). The primary endpoint finding (at one month) also favoured cytisine: RR 1.30 (95% CI 1.12 to 1.51; analysis not shown).

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 Cytisine vs NRT, Outcome 1 Continuous abstinence at 6m.

The cytisine trials did not for the most part identify more adverse events in the intervention than the control arm; Scharfenberg 1971 reported similar rates of mild adverse events (nausea, restlessness, insomnia, irritability) in the cytisine and placebo groups at four weeks (23.4% and 20% respectively in abstinent participants), but did not report long‐term rates for the full study population. Vinnikov 2008 reported 10 events in eight participants (four from each group), including dyspepsia, nausea and headache. West 2011 reported gastrointestinal disorders at higher rates in the cytisine than in the placebo group (13.8% vs 8.1%, P = 0.02). Walker 2014 reported significantly more adverse events (nausea, vomiting, sleep disorders) in the cytisine group compared with the NRT group (4.6% versus 0.03%; P = 0.0002), but similar rates of serious adverse events in the cytisine (6.9%) and the NRT (6.0%) groups.

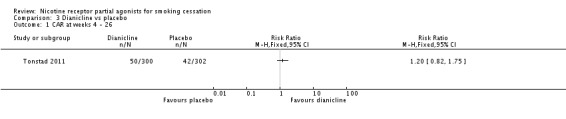

Dianicline

The one trial of dianicline that has published its findings (Tonstad 2011) reported continuous abstinence at 26 weeks. The quit rate among 300 dianicline users was 16.7%, compared with a placebo quit rate of 13.9% in 302 participants; this yields an RR of 1.20 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.75; Analysis 3.1). Results from the companion trial (Ameridian 2007) have not been made available to us by the manufacturers. Development of the drug has now been abandoned by Sanofi‐Aventis.

Analysis 3.1.

Comparison 3 Dianicline vs placebo, Outcome 1 CAR at weeks 4 ‐ 26.

Varenicline

The evidence base includes 39 methodologically sound clinical trials, involving more than 25,290 participants, 11,801 of whom received varenicline (see Appendix 2). Where point prevalence measures were the only ones reported, we have noted this in footnotes for each analysis.

The Nides 2006 and Nakamura 2007 comparisons chosen for our primary meta‐analysis were between the 1.0 mg twice a day group and the placebo group, since this matched the regimen now recommended for clinical practice. For the Oncken 2006 trial we combined the 1.0 mg twice a day titrated and non‐titrated groups for the meta‐analysis, since titration did not affect cessation rates.

I Varenicline versus other pharmacotherapies

1.1. Varenicline versus placebo

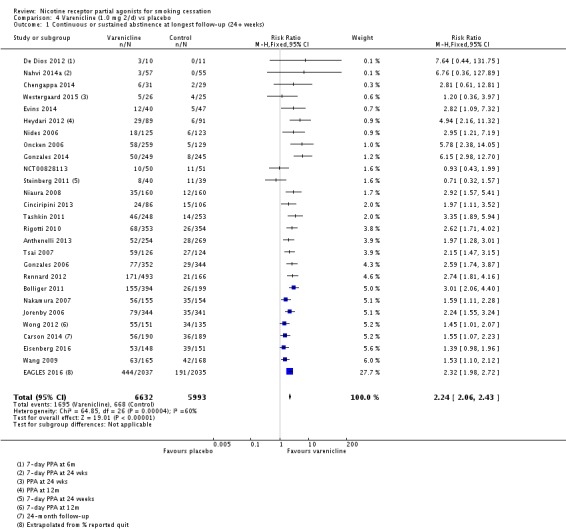

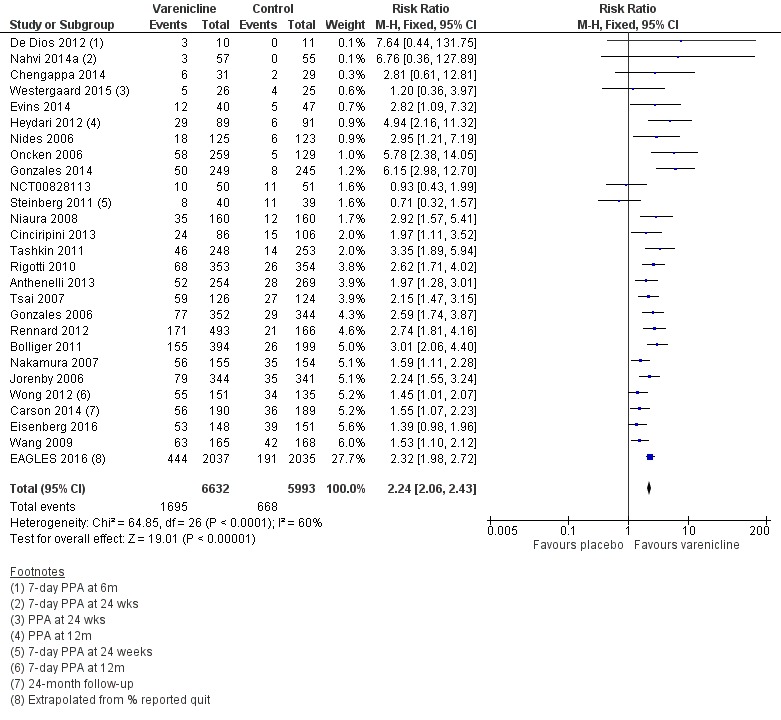

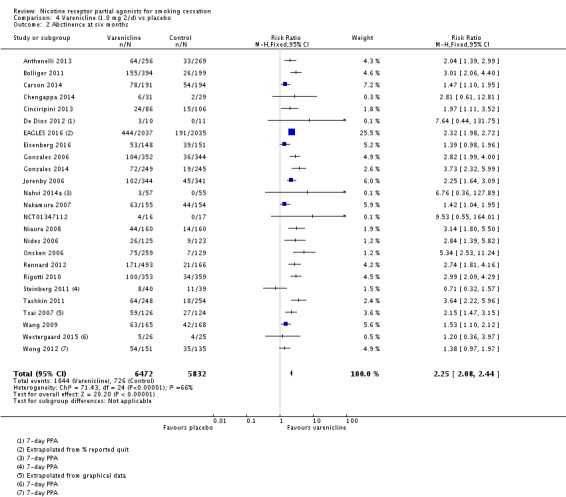

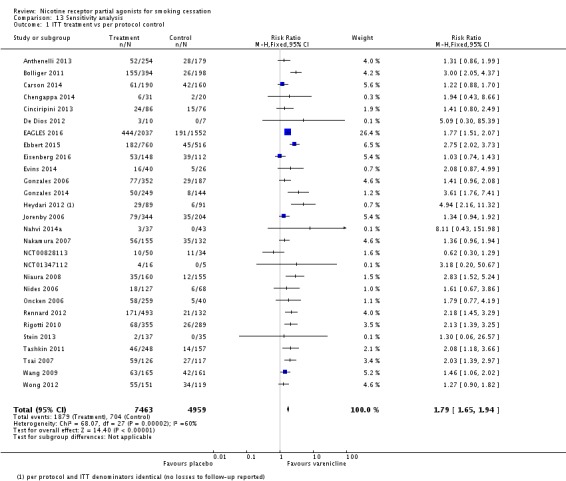

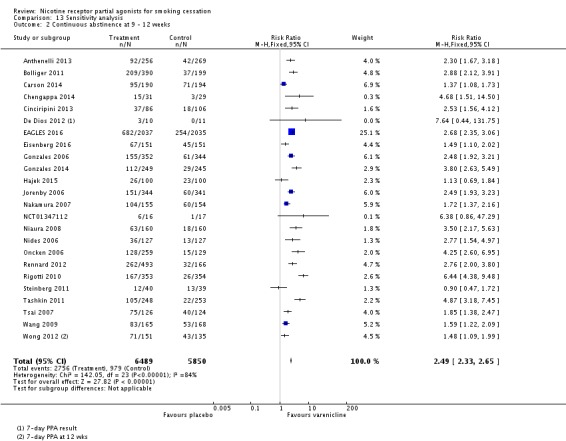

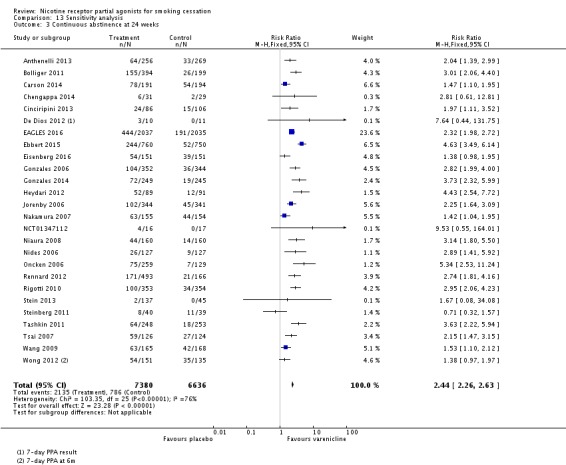

The pooled risk ratio (RR) for validated continuous abstinence six months or more from the start of the intervention (longest follow‐up) is 2.24 (95% CI 2.06 to 2.43; 27 trials, 12,625 participants, I² = 60%; high‐quality evidence; Analysis 4.1; Figure 2). This finding is consistent with that reported in the previous version of this review, which included 14 trials and 6166 participants. The current RR is based on 27 cessation trials of varenicline (26 versus placebo, and one (Carson 2014) versus counselling only). Although the control group did not receive placebo medication, we have included Carson 2014 in the main meta‐analysis; a sensitivity analysis excluding it made no appreciable difference to the estimate. All the trials in this analysis delivered varenicline at the standard dosage (1 mg twice a day) for 12 weeks, apart from Heydari 2012 and Nides 2006 (eight weeks). Limiting the analysis to the 15 studies with 12‐month follow‐up made little difference to the result (RR 2.29, 95% CI 2.02 to 2.60; 5904 participants). Six‐month abstinence rates for all 25 studies reporting this measure yielded a virtually identical RR of 2.25 (95% CI 2.08 to 2.44; 12,304 participants, I² = 66%; Analysis 4.2).

Analysis 4.1.

Comparison 4 Varenicline (1.0 mg 2/d) vs placebo, Outcome 1 Continuous or sustained abstinence at longest follow‐up (24+ weeks).

Figure 2.

Varenicline (1.0 mg 2/d) vs placebo, outcome: 3.1 Continuous abstinence at longest follow‐up (24+ weeks)

Analysis 4.2.

Comparison 4 Varenicline (1.0 mg 2/d) vs placebo, Outcome 2 Abstinence at six months.

The EAGLES 2016 trial presents results separately for the two constituent cohorts, with and without a history of psychiatric disorders. The groups without a psychiatric history in all cases and at both time points (12 and 24 weeks) achieved higher quit rates than the groups in the psychiatric cohort. The RR in the non‐psychiatric cohort for varenicline versus placebo was 2.42 (95% CI 1.97 to 2.99), with quit rates of 25.5% and 10.5% respectively; the corresponding measures in the psychiatric cohort were RR 2.20 (95% CI 1.73 to 2.80), and quit rates of 18.3% and 8.3% respectively. Treating the psychiatric cohort as a subgroup of the main analysis and testing for subgroup differences found no significant difference between the psychiatric cohort and the remaining trials (Chi² = 0.02, P = 0.88, I² = 0%; analysis not shown).

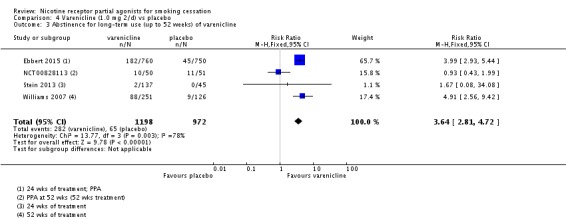

We have excluded from the main analysis four trials which tested extended varenicline treatment. Ebbert 2015 ('Reduce to quit') and Stein 2013 (substance‐abusing smokers on methadone maintenance) both tested 24 weeks of varenicline, and NCT00828113 and Williams 2007 (a safety trial) both prescribed 12 months of treatment. Pooling these data demonstrated a clear benefit for varenicline, with a RR of 3.64 (95% CI 2.81 to 4.72; 2170 participants, I² = 78%; Analysis 4.3). A sensitivity analysis removing NCT00828113, which is at high risk of attrition bias, increased the RR to 4.15 (95% CI 3.14 to 5.49) and dropped the I² to 0%.

Analysis 4.3.

Comparison 4 Varenicline (1.0 mg 2/d) vs placebo, Outcome 3 Abstinence for long‐term use (up to 52 weeks) of varenicline.

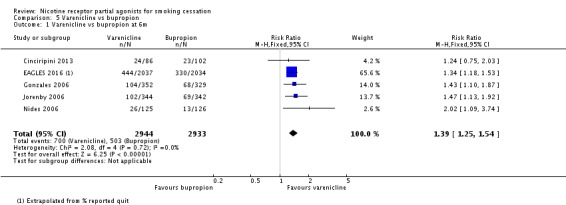

1.2. Varenicline versus bupropion

Five trials (Cinciripini 2013; EAGLES 2016; Gonzales 2006; Jorenby 2006; Nides 2006) compared varenicline to bupropion. Although the Nides 2006 trial tested three dosing variants of varenicline, we have used the '1 mg twice a day' arm for our analysis, since this matches the regimen now recommended for clinical practice. The pooled RR for the five trials at six months was RR 1.39 (95% CI 1.25 to 1.54; 5877 participants, I² = 0%; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 5.1), in favour of varenicline. We conducted a sensitivity analysis to test the effect of excluding Nides 2006, which had included previous users of bupropion, but the RR remained steady, at 1.37 (95% CI 1.23 to 1.52). The three‐month and 12‐month results were in line with the main finding (Analysis 5.2; Analysis 5.3).

Analysis 5.1.

Comparison 5 Varenicline vs bupropion, Outcome 1 Varenicline vs bupropion at 6m.

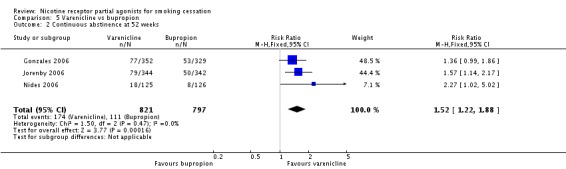

Analysis 5.2.

Comparison 5 Varenicline vs bupropion, Outcome 2 Continuous abstinence at 52 weeks.

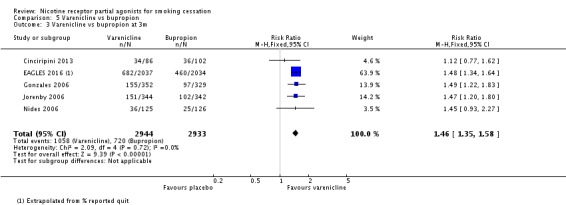

Analysis 5.3.

Comparison 5 Varenicline vs bupropion, Outcome 3 Varenicline vs bupropion at 3m.

The EAGLES 2016 trial demonstrated higher quit rates for this comparison in the non‐psychiatric than in the psychiatric cohort, with a RR of 1.36 (95% CI 1.15 to 1.60; non‐psychiatric), compared with RR 1.28 (95% CI 1.05 to 1.57; psychiatric). Quit rates were 25.5% for varenicline and 18.8% for bupropion in the non‐psychiatric cohort, and 18.3% for varenicline and 13.7% for bupropion in the psychiatric cohort.

1.3 Varenicline versus NRT

Eight trials tested varenicline against nicotine replacement therapy. Three trials were open‐label (Aubin 2008; Baker 2016; Tsukahara 2010), and one trial was an open‐label comparison of varenicline, NRT and no pharmacotherapy. Baker 2016 compared nicotine patch (the reference treatment) against varenicline and against combination NRT (patch plus lozenge). Three trials were placebo‐controlled three‐arm studies, with De Dios 2012 and Stein 2013 testing varenicline against a placebo tablet and against NRT, and Rose 2013 comparing varenicline, bupropion and NRT, with all participants receiving an active treatment plus two dummy treatments. EAGLES 2016 was a double‐blind four‐arm trial, comparing varenicline, bupropion and NRT against placebo. The pooled analysis indicates a benefit for varenicline over NRT. The RR at 24 weeks was 1.25 (95% CI 1.14 to 1.37; 6264 participants, I² = 39%; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 6.1). Removing the three open‐label trials (all at high risk of bias for blinding) from the analysis slightly strengthened the effect estimate (RR 1.34, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.50), and increased the I² value to 47%. Stein 2013 treated its participants for 24 weeks rather than the standard 12; removing it from the analysis made little difference to the result or to the I² value. For Baker 2016, Analysis 6.1 uses the varenicline/patch comparison; substituting the combination NRT arm for the nicotine patch arm made minimal difference to the study or meta‐analysis findings.

Analysis 6.1.

Comparison 6 Varenicline vs NRT, Outcome 1 Point prevalence abstinence at 24 weeks.

The EAGLES 2016 trial again demonstrated higher quit rates for this comparison in the non‐psychiatric than in the psychiatric cohort, with a RR of 1.38 (95% CI 1.17 to 1.63; non‐psychiatric), compared with RR 1.41 (95% CI 1.15 to 1.74; psychiatric). Quit rates were 25.5% for varenicline and 18.5% for NRT in the non‐psychiatric cohort, and 18.3% for varenicline and 13.0% for NRT in the psychiatric cohort.

1.4 Varenicline versus mecamylamine

No trials currently report on this comparison.

1.5 Combination varenicline treatment versus single‐therapy treatment

No trials currently report on this comparison.

1.6 Varenicline tablets versus other formulations

No trials currently report on this comparison.

II Variations in usage

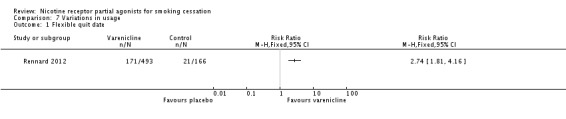

2.1 Flexible quit date

One large multicentre study (Rennard 2012) allowed participants to select their own quit date anywhere between 8 and 35 days after joining the study. The trial found a clear benefit for varenicline over placebo, with an RR of 2.74 (95% CI 1.81 to 4.16; 659 participants; Analysis 7.1). By the end of the four‐week 'quit window' (day 35), 80.5% of the varenicline group had made a quit attempt, compared with 73.3% of the placebo group. Varenicline participants were also found to have made an earlier quit attempt (median day 17) than the placebo participants (median day 24) (P = 0.0074).

Analysis 7.1.

Comparison 7 Variations in usage, Outcome 1 Flexible quit date.

2.2 Variable dosages

Low‐dose varenicline versus placebo

Four trials investigated this comparison (Nakamura 2007; Niaura 2008; Nides 2006; Oncken 2006). For this review, we have combined the titrated and non‐titrated arms of the Oncken 2006 trial, as there were no detectable differences between the arms for any outcomes. Three of the trials prescribed half the recommended daily dosage, either as a single 1 mg tablet or as two 0.5 mg doses, while Niaura 2008 allowed participants to regulate their own dosage at anywhere between 0.5 mg and 2.0 mg a day. The regimen favoured varenicline over placebo, with a RR at 52 weeks of 2.08 (95% CI 1.56 to 2.78; 1266 participants; Analysis 7.2). The Niaura 2008 trial found that those on varenicline settled on a mean modal dose of 1.35 mg a day, compared with 1.63 mg a day for the placebo group.

Analysis 7.2.

Comparison 7 Variations in usage, Outcome 2 Non‐standard dose varenicline versus placebo at 52 weeks.

Variable dosing at the participant's or physician's discretion

Six studies (Anthenelli 2013; Chengappa 2014; Cinciripini 2013; Gonzales 2014; Hajek 2015; Niaura 2008) explored the option of reducing the dosage to moderate side effects, either at the physician's behest or within the participant's own control. While this may have made the treatment more tolerable, it appeared not to have compromised efficacy, yielding a RR against placebo of 2.29 (95% CI 1.81 to 2.89; 1789 participants; I² = 70%; Analysis 7.2), which is very close to the point estimate for the main analysis, but with a wider confidence interval.

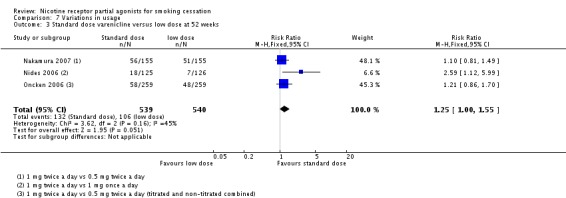

Standard‐dose versus low‐dose varenicline

Three trials (Nakamura 2007; Nides 2006; Oncken 2006) tested the standard regimen (1 mg twice a day) against half the recommended daily dose, either as a single 1 mg tablet or as two 0.5 mg doses, and found a modest advantage for the standard dosage: RR 1.25 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.55; 1079 participants; Analysis 7.3).

Analysis 7.3.

Comparison 7 Variations in usage, Outcome 3 Standard dose varenicline versus low dose at 52 weeks.

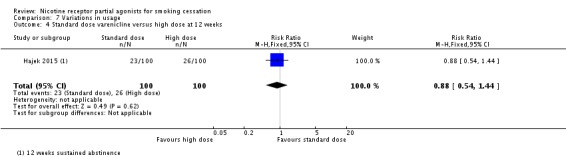

Standard dose versus high‐dose varenicline

In one recent trial (Hajek 2015; not included in the main analyses), 200 smokers who were judged not to be responding to the standard dose of varenicline (no strong nausea, no clear reduction in smoking enjoyment, and less than 50% smoking reduction after 10 days) were allocated to additional treatment (varenicline or placebo) up to the target quit date (day 21). Participants maintained that dosage for three weeks, but could reduce it if side effects became intolerable. Participants could take up to 3 mg a day in addition to the standard daily dose of 2 mg. The trial found a marginal but non‐significant benefit for quit rates with the higher dosing schedule, with an RR at 12 weeks of 0.88 (95% CI 0.54 to 1.44; Analysis 7.4), but noted a trend in the varenicline group for more fatigue and decreased appetite, and significantly higher levels of nausea and vomiting.

Analysis 7.4.

Comparison 7 Variations in usage, Outcome 4 Standard dose varenicline versus high dose at 12 weeks.

2.3 Preloading (before the TQD)

No trials currently report on this comparison.

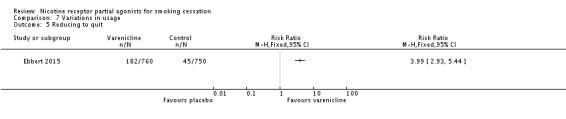

2.4 Reducing to quit

One recent trial (Ebbert 2015) tested varenicline against placebo in 1510 smokers disinclined to quit abruptly, but willing to reduce their smoking gradually as a gateway to quitting. Treatment was given in this trial for 24 weeks rather than the standard regimen of 12 weeks, with participants asked to reduce their smoking rate by 50% by week 4, by at least 75% by week 8, and by 100% by week 12. After 12 months, the RR for quitting was 3.99 (95% CI 2.93 to 5.44; Analysis 7.5) in favour of varenicline.

Analysis 7.5.

Comparison 7 Variations in usage, Outcome 5 Reducing to quit.

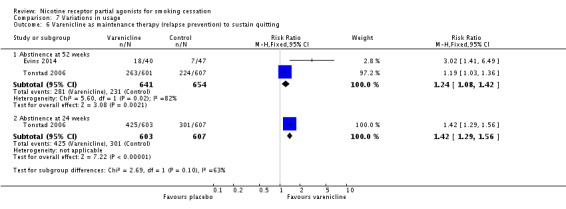

2.5 Maintenance therapy (relapse prevention)

Two trials have tested varenicline as an aid to relapse prevention in smokers who had successfully quit on varenicline. Tonstad 2006 randomised 1208 quitters to a further 12 weeks of either varenicline or placebo, while Evins 2014 randomised 87 quitters with schizophrenia, schizoaffective or bipolar disorder to a further 40 weeks of either varenicline or placebo treatment. We note that the integrity of the blinding in these trials may be questionable, as all the participants had already used open‐label varenicline to achieve abstinence. At 12 months, the RR in favour of varenicline was 1.24 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.42; Analysis 7.6). Heterogenity was high, at 82%, possibly reflecting the relatively extended treatment period in the smaller trial. A random‐effects analysis eliminated the significant difference (RR 1.75, 95% CI 0.71 to 4.33).

Analysis 7.6.

Comparison 7 Variations in usage, Outcome 6 Varenicline as maintenance therapy (relapse prevention) to sustain quitting.

2.6 Harm reduction

No trials currently report on this comparison.

III Specific patient groups

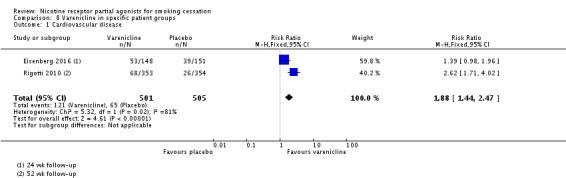

3.1 Cardiovascular disease (CVD)

Rigotti 2010 compared varenicline to placebo in a trial of 714 people with stable cardiovascular disease. Eisenberg 2016 randomised 302 smokers admitted for acute coronary syndrome to 12 weeks of treatment plus 12 weeks follow‐up. At longest follow‐up (52 weeks and 24 weeks respectively), the RR was 1.88 (95% CI 1.4 to 2.47; 1006 participants; I² = 81%; Analysis 8.1) in favour of varenicline. Treating the trials as a subgroup of the main analysis (Analysis 4.1) and testing for subgroup differences demonstrated no significant difference between them (Chi² = 1.70, P = 0.19, I² = 41.1%; analysis not shown).

Analysis 8.1.

Comparison 8 Varenicline in specific patient groups, Outcome 1 Cardiovascular disease.

3.2 COPD

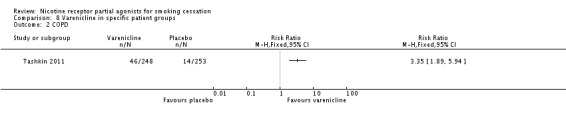

Tashkin 2011 compared varenicline to placebo in 504 adult smokers with mild to moderate COPD. At 52 weeks, the RR was 3.35 (95% CI 1.89 to 5.94; Analysis 8.2) in favour of varenicline.

Analysis 8.2.

Comparison 8 Varenicline in specific patient groups, Outcome 2 COPD.

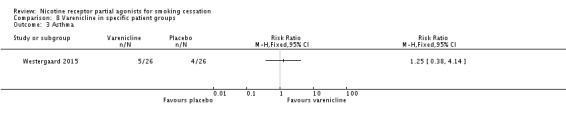

3.3 Asthma

Westergaard 2015 compared varenicline to placebo in 52 young adults (aged 19 to 40) with asthma. At six months, there was no difference in quit rates between the intervention and control arms (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.38 to 4.14; Analysis 8.3).

Analysis 8.3.

Comparison 8 Varenicline in specific patient groups, Outcome 3 Asthma.

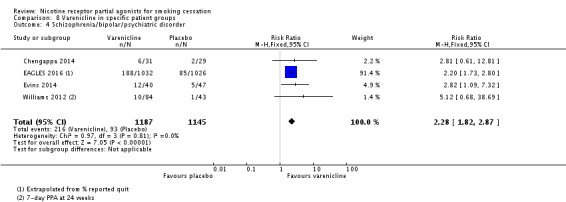

3.4 Schizophrenia/bipolar/psychiatric disorder

Four trials tested varenicline against placebo in smokers diagnosed with bipolar disorder (Chengappa 2014), with a history of various psychiatric disorders (and at least one‐third of the cohort stably taking psychotropic medications (EAGLES 2016), with schizophrenia, schizoaffective or bipolar disorders (Evins 2014), and with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (Williams 2012). The pooled analysis found a benefit for varenicline at six months, with a RR of 2.28 (95% CI 1.82 to 2.87; 2332 participants, I² = 0%; Analysis 8.4). Treating the trials as a subgroup of the main analysis (Analysis 4.1) and testing for subgroup differences demonstrated no significant difference between them (Chi² = 0.10, P = 0.76, I² = 0%; analysis not shown).

Analysis 8.4.

Comparison 8 Varenicline in specific patient groups, Outcome 4 Schizophrenia/bipolar/psychiatric disorder.

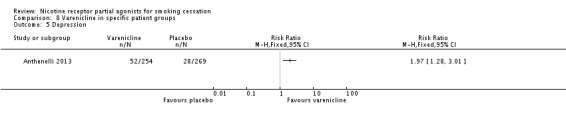

3.5 Depression

Anthenelli 2013 compared varenicline to placebo in 523 adult smokers with current or past depression. At 52 weeks, the RR was 1.97 (95% CI 1.28 to 3.01; Analysis 8.5) in favour of varenicline.

Analysis 8.5.

Comparison 8 Varenicline in specific patient groups, Outcome 5 Depression.

3.6 Substance use disorder/methadone‐maintained

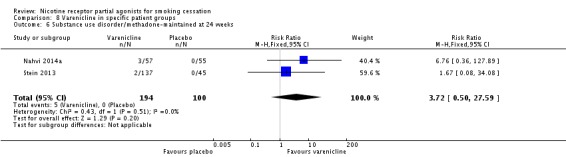

Two trials tested varenicline against placebo in smokers on methadone treatment for substance use disorder. Nahvi 2014a covered 112 outpatients in New York, and Stein 2013 315 outpatients in New England. The latter study included a combination NRT arm (patch + ad lib nicotine gum), which is included in Analysis 6.1. The pooled analysis did not find an effect of varenicline: RR 3.72 (95% CI 0.50 to 27.59; I² = 0%: Analysis 8.6). Treating the trials as a subgroup of the main analysis (Analysis 4.1) and testing for subgroup differences demonstrated no significant difference between them (Chi² = 0.25, P = 0.62, I² = 0%; analysis not shown).

Analysis 8.6.

Comparison 8 Varenicline in specific patient groups, Outcome 6 Substance use disorder/methadone‐maintained at 24 weeks.

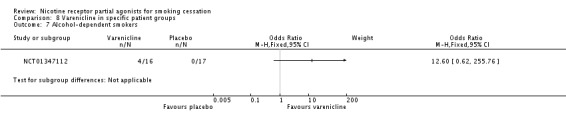

3.7 Alcohol‐dependent smokers

NCT01347112, which posted its results on the www.ClinicalTrials.gov website, reported cessation rates of 25% (4/16) for the varenicline group, and 0% (0/17) for the placebo group. These findings were not biochemically verified, and the study sustained high losses, putting it at high risk of bias.

3.8 HIV

No trials currently report on this comparison, although NCT00918307 includes a conference abstract giving preliminary findings. No results have been posted on the www.ClinicalTrials.gov trials registry database.

3.9 Diabetes

No trials currently report on this comparison.

3.10 Head and neck cancer

No trials currently report on this comparison.

3.11 Varenicline in pregnancy

No trials currently report on this comparison.

3.12 Varenicline for long‐term use of NRT

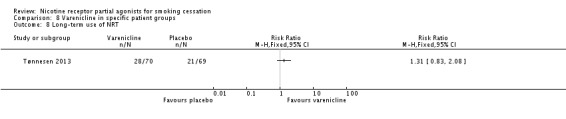

Tønnesen 2013 aimed to wean 139 ex‐smokers off long‐term use of NRT. All had been consuming an average of 16 NRT units a day for approximately six years. Participants were randomly allocated to varenicline or placebo for the standard 12‐week treatment phase, and were followed up to 52 weeks. The trial did not find a difference between the varenicline and placebo arms for participants, either for having smoked (10% in the varenicline group and 11.6% in the placebo group between weeks 36 and 52) or for not using NRT, with a RR of 1.31 (95% CI 0.83 to 2.08; Analysis 8.8).

Analysis 8.8.

Comparison 8 Varenicline in specific patient groups, Outcome 8 Long‐term use of NRT.

IV Different settings and subgroups

4.1 Hospital inpatients/perioperative patients

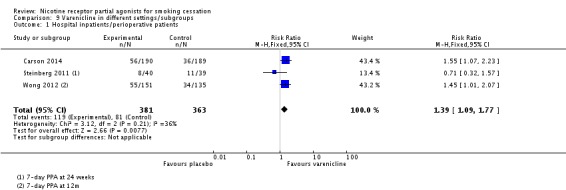

Three trials currently address this population of smokers. Carson 2014 targeted adult smokers admitted to hospital for smoking‐related acute illnesses, Steinberg 2011 adult smokers admitted with any diagnosis, and Wong 2012 adult smokers admitted for non‐cardiac elective surgery. The pooled analysis at longest follow‐up favoured varenicline treatment, with a RR of 1.39 (95% CI 1.09 to 1.77; 744 participants, I² = 36%; Analysis 9.1). Treating the trials as a subgroup of the main analysis (Analysis 4.1) and testing for subgroup differences demonstrated a significant difference between the hospital group and the remaining trials (Chi² = 15.87, P < 0.0001, I² = 93.7%; analysis not shown). This may be linked to the negative findings of the Steinberg 2011 trial.

Analysis 9.1.

Comparison 9 Varenicline in different settings/subgroups, Outcome 1 Hospital inpatients/perioperative patients.

4.2 Smokers who have previously failed to quit on varenicline or NRT or bupropion

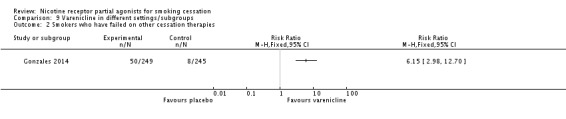

Gonzales 2014 tested varenicline versus placebo in a group of smokers who had previously used varenicline for two weeks or more, at least three months prior to admission to the study, and had failed to quit but were motivated to try again. The trial found a clear benefit for varenicline, with a RR at 52 weeks of 6.15 (95% CI 2.98 to 12.70; 494 participants; Analysis 9.2).

Analysis 9.2.

Comparison 9 Varenicline in different settings/subgroups, Outcome 2 Smokers who have failed on other cessation therapies.

4.3 Light or heavy smokers

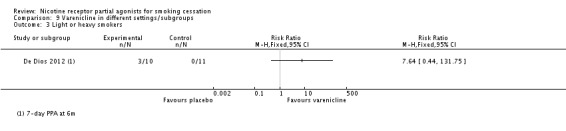

De Dios 2012 is a small pilot study conducted in 32 Latino light smokers (smoking 10 or fewer cigarettes a day), randomising to varenicline, NRT or placebo tablets. The six‐month result, although favouring the varenicline arm, did not achieve statistical significance: RR 7.64 (95% CI 0.44 to 131.75; Analysis 9.3)

Analysis 9.3.

Comparison 9 Varenicline in different settings/subgroups, Outcome 3 Light or heavy smokers.

4.4 Varenicline by gender

No trials currently address this comparison, although a recent meta‐analysis (McKee 2015) presents abstinence data stratified by gender from 16 RCTs (supplied by Pfizer). Their meta‐analysis demonstrates, compared with other smoking cessation treatments, greater efficacy for short‐ and immediate‐term outcomes in women smokers versus men, and equal efficacy for abstinence at one year.

4.5 Varenicline in ethnic groups

No trials currently report on this comparison.

2. Craving and withdrawal

The results of the trials included in our review lend support to the theoretical basis for the development of varenicline. Its properties as a partial agonist, causing moderate activation of the α4β2nAChR, may be expected to mitigate craving and withdrawal symptoms, while its antagonist properties in blocking nicotine binding may lead to reduced smoking satisfaction and reduced psychological reward in those who continue to smoke while taking the drug. The varenicline trials which tested withdrawal and craving all reported its superiority over placebo in reducing withdrawal symptoms, as measured on the Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale or the Wisconsin Smoking Withdrawal Scale; craving, as measured on the Brief Questionnaire of Smoking urges; and enjoyment of concurrent smoking, as measured on the modified Cigarette Evaluation Questionnaire.Those trials (Nides 2006; Oncken 2006; Nakamura 2007; Niaura 2008) which measured the effects of varying dosage detected greater reductions in craving and withdrawal symptoms in the standard dose groups (1.0 mg twice a day) than in the reduced dose groups. Hajek 2015 noted similar disparities in enjoyment of smoking when participants moderated their own dosage up to the TQD. Full details of the comparative incidence of craving and withdrawal symptoms are shown in Appendix 3.

3. Adverse events (AEs)

The predominant adverse event for varenicline was mild to moderate nausea, subsiding over time, at rates between 6% (Stein 2013) and 51% (Nahvi 2014a), but with almost half the studies reporting levels between 24% and 29%. The trials testing non‐standard regimens found a dose‐response relationship for the incidence of nausea: rates ranged from 17.5% (0.3 mg daily) to 52% (1.0 mg twice daily) in Nides 2006, and from 7.2% (0.25 mg twice daily) to 24.4% (1.0 mg twice daily) in Nakamura 2007. Self regulation of treatment in Niaura 2008 appeared to reduce rates of nausea, with 13.4% of varenicline users reporting it compared with 5.2% of the placebo group. Both titration and dosage levels affected the incidence and severity of nausea in Oncken 2006, with the lower dose resulting in rates of 16.3% (titrated) and 22.6% (non‐titrated), compared with 34.9% (titrated) and 41.9% (non‐titrated) in the standard dosage groups. Hajek 2015 allowed participants to increase their dosage up to 5 mg a day by the TQD, and reported nausea rates of 80% in the varenicline group compared with 18% among the placebo participants. In Gonzales 2006 and Jorenby 2006, an average of 9.5% in the varenicline groups discontinued treatment but remained in the trial for follow‐up, compared with an average of 14% in the bupropion groups and 8% in the placebo groups. Discontinuation rates for any adverse event were highest in Williams 2007, where participants took the trial medication for a year, at 28.3% in the varenicline group and 10.3% in the control group. In the 12‐week open‐label phase of Evins 2014, 31.8% of participants taking varenicline discontinued the study because of adverse events, or for non‐adherence to the protocol, or because they no longer wished to stop smoking. In Phase 1 of Rose 2013, 62 of 112 (55%) non‐responders to NRT assigned to varenicline withdrew or were lost to follow‐up, but this was a comparable attrition rate to those lost from the NRT group (60%) and from the bupropion group (58%), and appeared not to be associated with adverse events. The study also noted that 25% of participants across all three conditions reduced their dosage at some point during treatment.

Adverse events were monitored weekly during treatment from weeks one to seven (Gonzales 2006; Jorenby 2006; Nides 2006; Oncken 2006), weekly throughout 12 weeks of treatment (Anthenelli 2013; Aubin 2008; Bolliger 2011; Carson 2014; Cinciripini 2013; EAGLES 2016; Ebbert 2015; Evins 2014; Gonzales 2014; Nakamura 2007; Niaura 2008; Rennard 2012; Rigotti 2010; Tashkin 2011; Tsai 2007; Wang 2009), or fortnightly throughout 12 weeks of treatment (Rose 2013; Tønnesen 2013). Stein 2013 monitored participants at weeks two and four, for adherence and adverse events. Tonstad 2006 monitored at week 13 (end of open‐label phase) and at week 25 (end of double‐blind phase), and Williams 2007 monitored weekly from weeks one to eight and then monthly to week 52. Baker 2016 monitored adverse events and delivered counselling at weeks 1, 4, 8 and 12. Steinberg 2011 collected adverse event data through self report at weeks 2, 4, 12 and 24, and Nahvi 2014a in four visits over 12 weeks of treatment. Hajek 2015 followed the UK's NHS Stop Smoking Service protocol and monitored weekly for the first month post‐TQD, and again at 12‐week end of treatment. The trials reported only those adverse events occurring in at least 5% of the varenicline groups, and at higher rates than in the placebo groups, with the exception of Bolliger 2011, Nahvi 2014a, Nakamura 2007, Stein 2013, Steinberg 2011, and Tønnesen 2013 (any occurrence), Anthenelli 2013 (occurring in 1% of either group), Ebbert 2015 (occurring in at least 2% of either group), Chengappa 2014, Cinciripini 2013, Gonzales 2014, and Hajek 2015 (at least 5% in either group), Evins 2014 (occurring in 10% of either group), and Rennard 2012 (any event occurring in at least 5% of either group, and psychiatric events in at least 1% of either group).

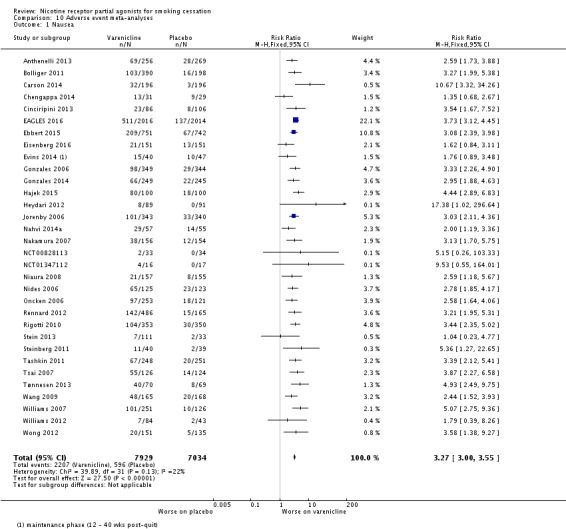

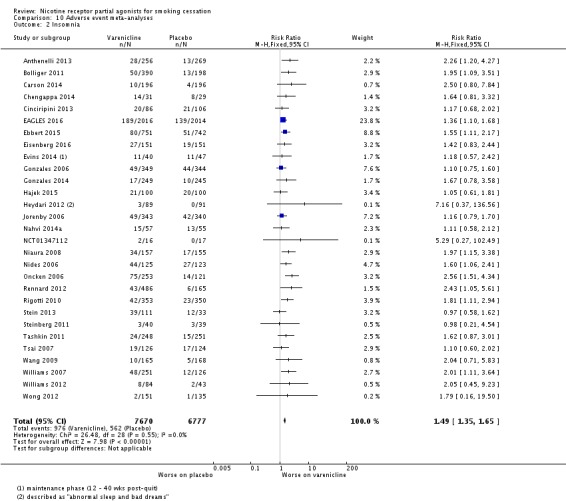

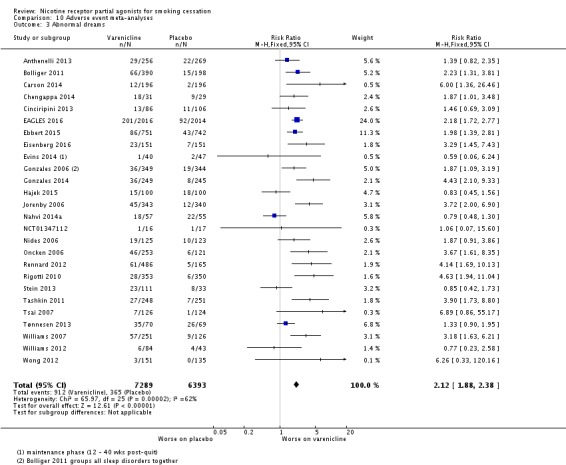

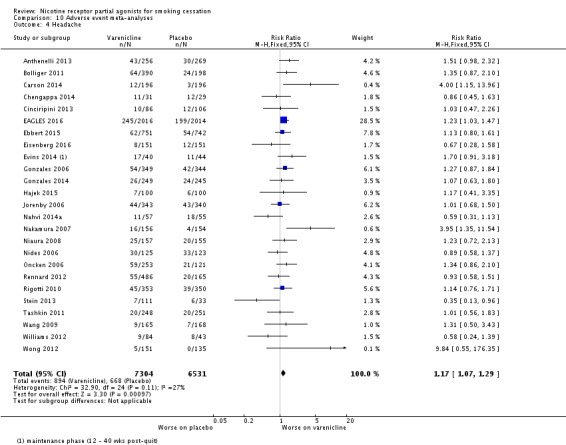

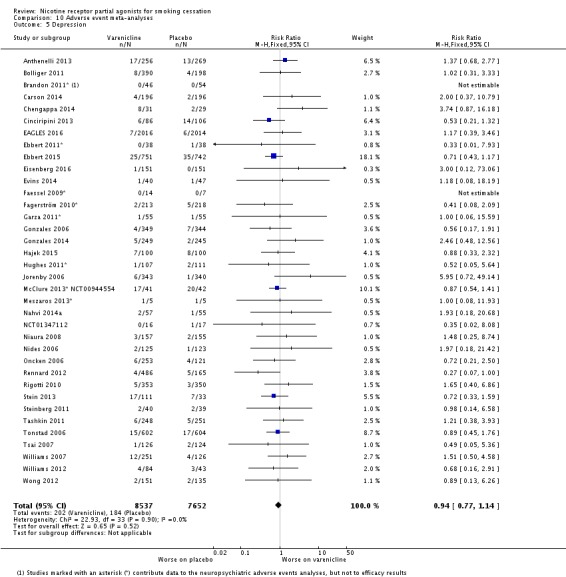

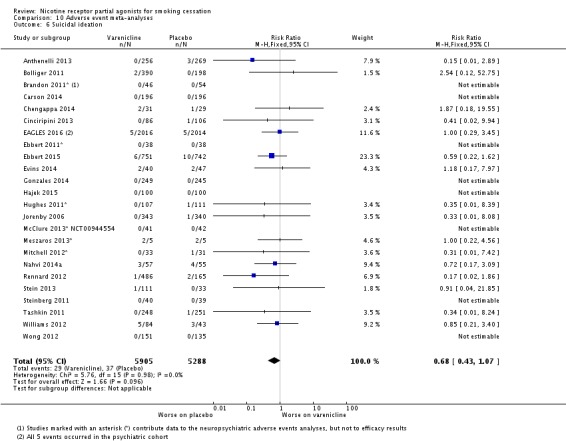

Meta‐analyses of the four main adverse events in the varenicline versus placebo groups yielded RRs of 3.27 (95% CI 3.00 to 3.55; 32 studies; 14,963 participants; I² = 22%) for nausea (Analysis 10.1); 1.49 (95% CI 1.35 to 1.65; 29 studies; 14,447 participants; I² = 0%) for insomnia (Analysis 10.2); 2.12 (95% CI 1.88 to 2.38; 26 studies; 13,682 participants; I² = 62%) for abnormal dreams (Analysis 10.3); and 1.17 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.29; 25 studies; 13,835 participants; I² = 27%) for headache (Analysis 10.4). All differences were statistically significant.

Analysis 10.1.

Comparison 10 Adverse event meta‐analyses, Outcome 1 Nausea.

Analysis 10.2.

Comparison 10 Adverse event meta‐analyses, Outcome 2 Insomnia.

Analysis 10.3.

Comparison 10 Adverse event meta‐analyses, Outcome 3 Abnormal dreams.

Analysis 10.4.

Comparison 10 Adverse event meta‐analyses, Outcome 4 Headache.

4. Serious Adverse Events (SAEs)

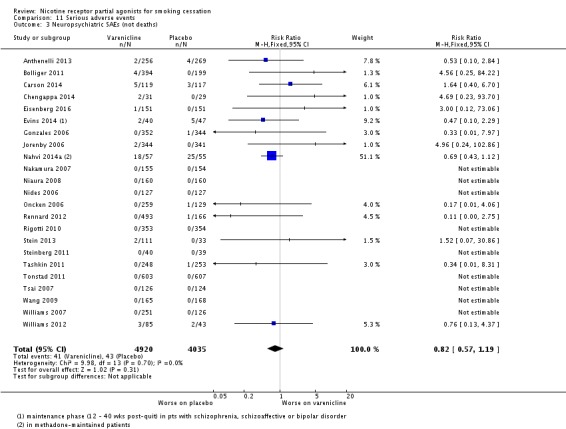

A serious adverse event (SAE) may be defined as any untoward medical occurrence that resulted in death; was life‐threatening; required inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation; resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity; or resulted in a congenital anomaly or birth defect (Nakamura 2007). Vinnikov 2008 reported no SAEs in their cytisine trial, while West 2011 reported seven, none of which was deemed to be related to the medication, and Scharfenberg 1971 gave no information about the incidence of SAEs in either group. Walker 2014, comparing cytisine with NRT (no placebo group), reported 56 SAEs in 45 participants taking cytisine (eight of the SAEs occurring in one person), and 45 SAEs in 39 participants taking NRT. One person died in each group, but neither death (one alcohol‐related asphyxiation and one heart attack) was deemed to be treatment‐related.