Abstract

Background

To minimise the rate of recurrent prolapse after traditional native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy), clinicians have utilised a variety of surgical techniques.

Objectives

To determine the safety and effectiveness of surgery for anterior compartment prolapse.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Register, including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, MEDLINE In Process (23 August 2016), handsearched journals and conference proceedings (15 February 2016) and searched trial registers (1 August 2016).

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that examined surgical operations for anterior compartment prolapse.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected trials, assessed risk of bias and extracted data. Primary outcomes were awareness of prolapse, repeat surgery and recurrent prolapse on examination.

Main results

We included 33 trials (3332 women). The quality of evidence ranged from very low to moderate. Limitations were risk of bias and imprecision. We have summarised results for the main comparisons.

Native tissue versus biological graft

Awareness of prolapse: Evidence suggested few or no differences between groups (risk ratio (RR) 0.98, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.52 to 1.82; five RCTs; 552 women; I2 = 39%; low‐quality evidence), indicating that if 12% of women were aware of prolapse after biological graft, 7% to 23% would be aware after native tissue repair.

Repeat surgery for prolapse: Results showed no probable differences between groups (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.97; seven RCTs; 650 women; I2 = 0%; moderate‐quality evidence), indicating that if 4% of women required repeat surgery after biological graft, 2% to 9% would do so after native tissue repair.

Recurrent anterior compartment prolapse: Native tissue repair probably increased the risk of recurrence (RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.65; eight RCTs; 701 women; I2 = 26%; moderate‐quality evidence), indicating that if 26% of women had recurrent prolapse after biological graft, 27% to 42% would have recurrence after native tissue repair.

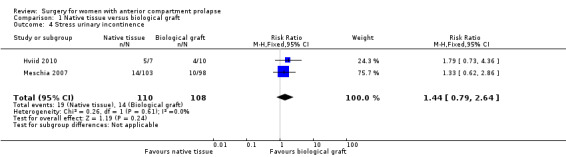

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI): Results showed no probable differences between groups (RR 1.44, 95% CI 0.79 to 2.64; two RCTs; 218 women; I2 = 0%; moderate‐quality evidence).

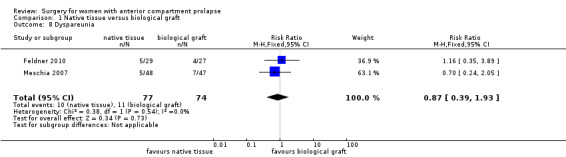

Dyspareunia: Evidence suggested few or no differences between groups (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.93; two RCTs; 151 women; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence).

Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh

Awareness of prolapse: This was probably more likely after native tissue repair (RR 1.77, 95% CI 1.37 to 2.28; nine RCTs; 1133 women; I2 = 0%; moderate‐quality evidence), suggesting that if 13% of women were aware of prolapse after mesh repair, 18% to 30% would be aware of prolapse after native tissue repair.

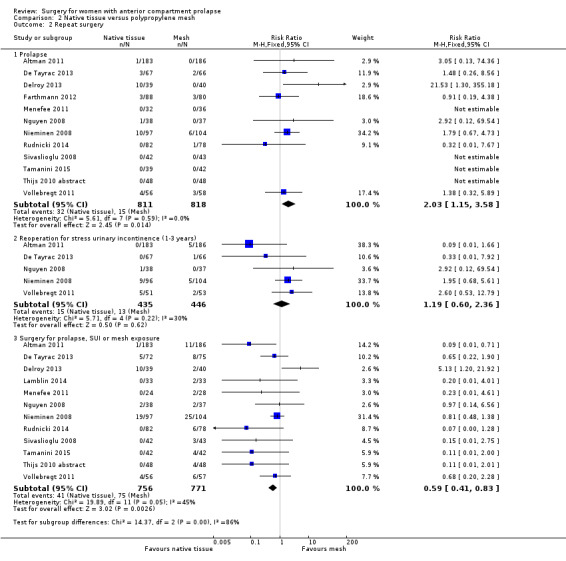

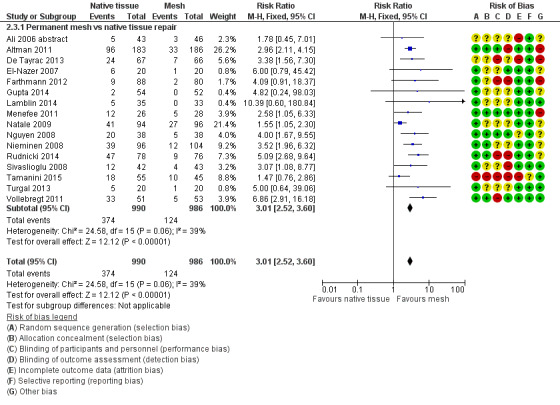

Repeat surgery for prolapse: This was probably more likely after native tissue repair (RR 2.03, 95% CI 1.15 to 3.58; 12 RCTs; 1629 women; I2 = 39%; moderate‐quality evidence), suggesting that if 2% of women needed repeat surgery after mesh repair, 2% to 7% would do so after native tissue repair.

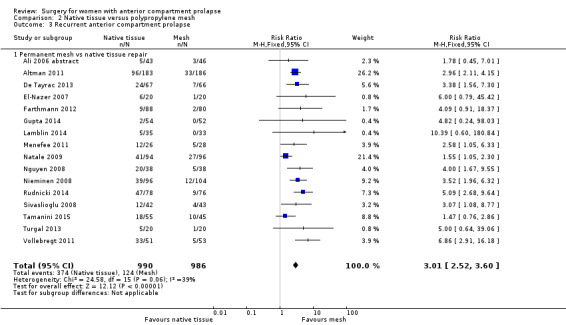

Recurrent anterior compartment prolapse: This was probably more likely after native tissue repair (RR 3.01, 95% CI 2.52 to 3.60; 16 RCTs; 1976 women; I2 = 39%; moderate‐quality evidence), suggesting that if recurrent prolapse occurred in 13% of women after mesh repair, 32% to 45% would have recurrence after native tissue repair.

Repeat surgery for prolapse, stress urinary incontinence or mesh exposure (composite outcome): This was probably less likely after native tissue repair (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.83; 12 RCTs; 1527 women; I2 = 45%; moderate‐quality evidence), suggesting that if 10% of women require repeat surgery after polypropylene mesh repair, 4% to 8% would do so after native tissue repair.

De novo SUI: Evidence suggested few or no differences between groups (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.01; six RCTs; 957 women; I2 = 26%; low‐quality evidence). No evidence suggested a difference in rates of repeat surgery for SUI.

Dyspareunia (de novo): Evidence suggested few or no differences between groups (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.06; eight RCTs; n = 583; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence).

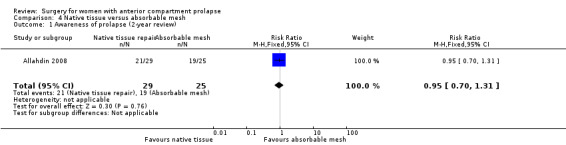

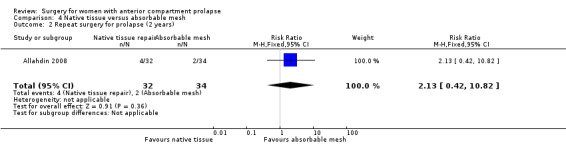

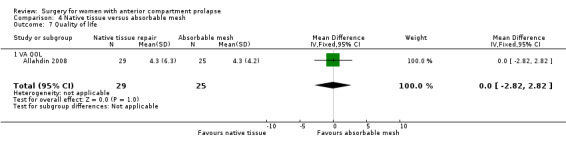

Native tissue versus absorbable mesh

Awareness of prolapse: It is unclear whether results showed any differences between groups (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.31; one RCT; n = 54; very low‐quality evidence),

Repeat surgery for prolapse: It is unclear whether results showed any differences between groups (RR 2.13, 95% CI 0.42 to 10.82; one RCT; n = 66; very low‐quality evidence).

Recurrent anterior compartment prolapse: This is probably more likely after native tissue repair (RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.09 to 2.06; three RCTs; n = 268; I2 = 0%; moderate‐quality evidence), suggesting that if 27% have recurrent prolapse after mesh repair, 29% to 55% would have recurrent prolapse after native tissue repair.

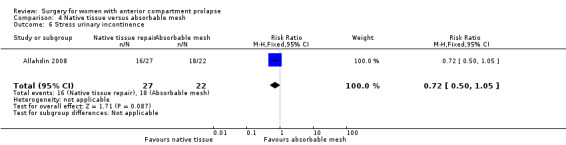

SUI: It is unclear whether results showed any differences between groups (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.05; one RCT; n = 49; very low‐quality evidence).

Dyspareunia: No data were reported.

Authors' conclusions

Biological graft repair or absorbable mesh provides minimal advantage compared with native tissue repair.

Native tissue repair was associated with increased awareness of prolapse and increased risk of repeat surgery for prolapse and recurrence of anterior compartment prolapse compared with polypropylene mesh repair. However, native tissue repair was associated with reduced risk of de novo SUI, reduced bladder injury, and reduced rates of repeat surgery for prolapse, stress urinary incontinence and mesh exposure (composite outcome).

Current evidence does not support the use of mesh repair compared with native tissue repair for anterior compartment prolapse owing to increased morbidity.

Many transvaginal polypropylene meshes have been voluntarily removed from the market, and newer light‐weight transvaginal meshes that are available have not been assessed by RCTs. Clinicans and women should be cautious when utilising these products, as their safety and efficacy have not been established.

Keywords: Female, Humans, Cystocele, Cystocele/surgery, Gynecologic Surgical Procedures, Gynecologic Surgical Procedures/methods, Pelvic Organ Prolapse, Pelvic Organ Prolapse/prevention & control, Pelvic Organ Prolapse/surgery, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Rectal Prolapse, Rectal Prolapse/surgery, Secondary Prevention, Surgical Mesh, Suture Techniques, Urinary Incontinence, Urinary Incontinence/surgery, Uterine Prolapse, Uterine Prolapse/surgery

Plain language summary

Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women

Review question

To determine the safety and effectiveness of surgery for anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Background

Pelvic organ prolapse occurs in up to 50% of women who have given birth. This can happen at different sites within the vagina; prolapse of the anterior compartment is most difficult to repair, and rates of recurrence are higher than at other vaginal sites. This challenge has resulted in the use of a variety of surgical techniques and grafts to improve outcomes of anterior compartment prolapse surgery. We aimed to evaluate surgical interventions for anterior compartment prolapse.

Study characteristics

Cochrane authors included in this review 33 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating 3332 surgeries to compare traditional native tissue anterior repair versus biological grafts (eight trials), absorbable mesh (three trials), permanent (polypropylene) mesh (16 trials) and abdominal paravaginal repair (two trials). Four trials compared a transvaginal graft versus another transvaginal graft, and four trials evaluated native tissue repair of anterior and/or posterior compartments of the vagina versus graft repair. Evidence is current to 23 August 2016.

Key results

Biological graft repair or absorbable mesh provides minimal advantage compared with native tissue repair. Results showed no evidence of differences between biological graft and native tissue repair in rates of awareness of prolapse or repeat surgery for prolapse. However, the recurrent anterior prolapse rate was higher after native tissue repair than after any biological graft. This suggests that if awareness of prolapse after biological graft occurs in 12% of women, 7% to 23% would be aware of prolapse after native tissue repair.

Permanent mesh resulted in lower rates of awareness of prolapse, recurrent anterior wall prolapse and repeat surgery for prolapse compared with native tissue repair. However, native tissue repair was associated with reduced risk of new stress urinary incontinence. Other benefits of native tissue repair included reduced bladder injury and reduced rates of repeat surgery for prolapse, stress urinary incontinence and mesh exposure (as a combined outcome).

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the data related to traditional native tissue anterior repair compared with both biological grafts and permanent mesh is generally low to moderate. The main limitations were incomplete reporting of study methods including allocation concealment and bias and imprecision in data outcomes. Data related to the efficacy of absorbable mesh are probably incomplete.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Anterior prolapse repair: native tissue versus biological graft in women with anterior compartment pelvic organ prolapse.

| Anterior prolapse repair: native tissue versus biological graft in women with anterior compartment pelvic organ prolapse | ||||||

|

Patient or population: women with anterior compartment pelvic organ prolapse

Setting: hospital departments of obstetrics and gynaecology

Intervention: native tissue (anterior repair, colporrhaphy) Comparison: biological graft | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Biological graft | Native tissue | |||||

| Awareness of prolapse (1‐2 years) | 124 per 1000 | 122 per 1000 (65 to 226) | RR 0.98 (0.52 to 1.82) | 552 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Lowa,b | |

| Repeat surgery for prolapse (1‐2 years) | 44 per 1000 | 45 per 1000 (23 to 86) | RR 1.02 (0.53 to 1.97) | 650 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb | |

| Recurrent anterior compartment prolapse (1‐2 years) | 257 per 1000 | 340 per 1000 (273 to 424) | RR 1.32 (1.06 to 1.65) | 701 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Moderatec | |

| Stress urinary incontinence (1‐2 years) | 130 per 1000 | 187 per 1000 (102 to 342) | RR 1.44 (0.79 to 2.64) | 218 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Moderateb | Repeat surgery for SUI was not reported by any studies |

| Dyspareunia (1‐2 years) | 149 per 1000 | 129 per 1000 (58 to 287) | RR 0.87 (0.39 to 1.93) | 151 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Lowb,d | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the mean control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI = confidence interval; RR = risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aRisk of bias: allocation concealment not reported in 2/5, downgraded one level.

bSerious imprecision: wide confidence interval, greater than 25% increase in RR, downgraded one level. cDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias: five of eight trials did not report blinded outcome assessment, downgraded one level. dRisk of bias: blinded outcome assessment unreported in one of two trials, downgraded one level.

Summary of findings 2. Anterior prolapse repair: native tissue versus polypropylene mesh for women with anterior compartment pelvic organ prolapse.

| Anterior prolapse repair: native tissue versus polypropylene mesh for women with anterior compartment pelvic organ prolapse | ||||||

|

Patient or population: women with anterior compartment pelvic organ prolapse Setting: hospital departments of obstetrics and gynaecology Intervention: native tissue (anterior repair, colporrhaphy) Comparison: polypropylene mesh | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Polypropylene mesh repair | Native tissue repair | |||||

| Awareness of prolapse (1‐3 years) | 130 per 1000 | 230 per 1000 (178 to 297) | RR 1.77 (1.37 to 2.28) | 1133 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | |

| Repeat surgery for prolapse (1‐3 years) | 18 per 1000 | 37 per 1000 (21 to 66) | RR 2.03 (1.15 to 3.58) | 1629 (12 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate2 | |

| Repeat surgery for stress urinary incontinence (1‐2 years) | 29 per 1000 |

35 per 1000 (17 to 69) |

RR 1.19 (0.60 to 2.36) |

881 (5 studies) |

Low3,4 | |

| Recurrent anterior compartment prolapse (1‐3 years) | 126 per 1000 | 379 per 1000 (317 to 453) | RR 3.01 (2.52 to 3.60) | 1976 (16 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low5,6 | |

| Stress urinary incontinence (de novo) (1‐3 years) | 102 per 1000 | 69 per 1000 (45 to 103) | RR 0.67 (0.44 to 1.01) | 957 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low4,7 | |

| Dyspareunia (de novo) (1‐2 years) | 72 per 1000 |

39 per 1000 (19 to 76) |

RR 0.54 (0.27 to 1.06) |

583 (8 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ Low4,7 | |

| Repeat surgery for prolapse, SUI or mesh exposure (1‐3 years) | 97 per 1000 | 54 per 1000 |

RR 0.59 (0.41 to 0.83) |

1527 (12 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate2 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the mean control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI = confidence interval; RR = risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Risk of bias: allocation concealment not reported in 4/9, downgraded one level. 2Risk of bias: allocation concealment not reported in 6/12, downgraded one level.

3Risk of bias: allocation concealment not reported in 2/5: downgraded one level.

4Serious imprecision: wide CI with lower RR (0.25), downgraded one level.

5Risk of bias: 11/15 trials did not report blinded outcome assessment, downgraded one level.

6Risk of bias: allocation concealment not reported in 7/15, downgraded one level.

7Risk of bias: poor methodological reporting of allocation concealment and/or blinding, downgraded one level.

Summary of findings 3. Anterior prolapse repair: native tissue versus absorbable mesh for women with anterior and/or posterior compartment pelvic organ prolapse.

| Anterior prolapse repair: native tissue repair versus absorbable mesh for women with anterior and/or posterior compartment pelvic organ prolapse | ||||||

|

Patient or population: women with anterior compartment pelvic organ prolapse Setting: hospital departments of obstetrics and gynaecology Intervention: native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy) Comparison: absorbable mesh |

||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Absorbable mesh | Native tissue repair | |||||

| Awareness of prolapse (2 years) | 760 per 1000 | 722 per 1000 (532 to 996) | RR 0.95 (0.70 to 1.31) | 54 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | |

|

Repeat surgery for prolapse (stage 2 or greater) at 2 years |

59 per 1000 | 125 per 1000 (25 to 636) | RR 2.13 (0.42 to 10.82) | 66 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | |

| Recurrent anterior compartment prolapse (3 months to 2 years) | 267 per 1000 | 401 per 1000 (291 to 550) | RR 1.50 (1.09 to 2.06) | 268 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Moderated | |

| De novo dyspareunia | Not reported in the included studies | |||||

| Stress urinary incontinence (2 years) | 818 per 1000 | 589 per 1000 (409 to 859) | RR 0.72 (0.50 to 1.05) | 49 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | Repeat surgery for SUI was not reported by any studies |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the mean control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI = confidence interval; RR = risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aRisk of bias: at 2 years, 18% lost to review, downgraded one level. bSerious imprecision: single small trial with confidence interval compatible with benefit in either arm or no effect. Low event rate, downgraded one level. cPublication bias: evidence based on a single small trial, downgraded one level.

dRisk of bias: blinded outcome assessment not reported in 2/3 trials, and high attrition in one, downgraded one level.

Background

Description of the condition

Pelvic organ prolapse is common and is seen on examination in 40% to 60% of parous women (Handa 2004; Hendrix 2002). The annual aggregated rate of associated surgery in the United States is in the range of 10 to 30 per 10,000 women (Brubaker 2002). The anterior compartment of the vagina is the vaginal site most commonly affected by prolapse and is the most difficult to repair.

Pelvic organ prolapse is the descent of one or more of the pelvic organs (uterus, vagina, bladder or bowel). Different types of prolapse include:

upper vaginal prolapse (i.e. uterus, vaginal vault (after hysterectomy when the top of the vagina drops down));

anterior vaginal wall prolapse (i.e. cystocele (bladder descends), urethrocele (urethra descends), paravaginal defect (pelvic fascia defect)); and

posterior vaginal wall prolapse (i.e. enterocele (small bowel descends), rectocele (rectum descends), perineal deficiency).

A woman can present with prolapse of one or more of these sites.

The aetiology of pelvic organ prolapse is complex and multi‐factorial. Possible risk factors include pregnancy, childbirth, congenital or acquired connective tissue abnormalities, denervation or weakness of the pelvic floor, ageing, hysterectomy, menopause and factors associated with chronically raised intra‐abdominal pressure (Bump 1998; Gill 1998; MacLennan 2000).

Women with anterior compartment prolapse commonly have a variety of pelvic floor symptoms, only some of which are directly related to the prolapse. Generalised symptoms of prolapse include pelvic heaviness; a bulge, lump or protrusion coming down from the vagina; a dragging sensation in the vagina; and backache. Symptoms of bladder, bowel or sexual dysfunction are frequently present. For example, women may need to reduce the prolapse by using their fingers to push the prolapse up to aid urinary voiding or defecation. These symptoms may be directly related to the prolapsed organ, for example, poor urinary stream when a cystocele is present or obstructed defecation when a rectocele is present. Symptoms may also be independent of the prolapse, for example, symptoms of overactive bladder (urinary urgency) or urinary stress incontinence when a cystocele is present.

Description of the intervention

Treatment of a woman with prolapse depends on the severity of the prolapse, its symptoms, the woman's general health and surgeon preference and capabilities. Options for treatment include conservative, mechanical and surgical interventions.

Generally, conservative or mechanical treatments are considered for women with a mild degree of prolapse, those who wish to have more children, frail women and those unwilling to undergo surgery. Conservative and mechanical interventions have been considered in separate Cochrane reviews (Adams 2004; Hagen 2011). No good evidence was available to guide management in either of these reviews.

A wide variety of abdominal and vaginal surgical techniques are available for the treatment of patients with prolapse (Appendix 1). The most common and traditional procedure is the anterior repair (colporrhaphy) for anterior vaginal wall prolapse, which is frequently performed in conjunction with other interventions for prolapse and/or urinary stress incontinence. Together, anterior and posterior compartment surgeries account for more than 90% of all prolapse operations (Olsen 1997). Two main approaches can be used.

Vaginal approaches include vaginal hysterectomy, anterior or posterior vaginal wall repair (colporrhaphy), McCall culdoplasty, Manchester repair (amputation of the cervix with uterus suspension to the cardinal ligaments), prespinous and sacrospinous colpopexy, enterocele ligation, paravaginal repair, Le Fortes procedure and perineal reconstruction.

Abdominal approaches include hysterectomy, sacral colpopexy, paravaginal repair, vault suspending and uterosacral ligament plication, enterocele ligation and posterior vaginal wall repair. Abdominal surgery can be performed through an open incision or keyhole incisions via the laparoscope or robot.

The current review considers all surgical procedures for women with anterior compartment pelvic organ prolapse.

A combination of some of the above‐mentioned procedures may be employed concomitantly at the time of anterior compartment prolapse surgery. In addition to the variety of prolapse operations that can be performed, the surgeon must choose whether to use absorbable sutures such as polyglycolic acid‐based materials (e.g. polyglactin), delayed‐absorption sutures such as polydioxanone or non‐absorbable sutures such as polypropylene. Furthermore, to improve the anatomical outcomes of anterior compartment prolapse, some techniques employ grafts. Graft material can be synthetic (e.g. permanent polypropylene, absorbable polyglactin mesh) or biological. Biological grafts can be further divided into autologous (from a person's own tissue, such as fascial sheath), alloplastic (from animals, such as porcine dermis) and homologous (such as cadaveric fascia lata).

The choice of operation depends on several factors, which include the nature, site and severity of the prolapse; whether additional symptoms are affecting urinary, bowel or sexual function; the general health of the woman; and surgeon preference and capability. Concomitant procedures are often performed to treat or prevent urinary incontinence at the same time. Mid‐urethral slings and tapes that are utilised in continence surgery are not the topic of this review, and the reader is referred to Ford 2015 for a full review of continence surgery.

To aid in assessment of the surgery, clear preoperative and postoperative site‐specific vaginal grading, details of the operative intervention and impact of the surgery on functional aspects of bladder, bowel and sexual function should be recorded.

Over the past five years and following significant litigation regarding outcomes of prolapse surgery after transvaginal polypropylene mesh, many of the products evaluated in this review have been voluntarily removed from the market (Prolift ‐ Gynecare/Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA; Perigee American Medical Systems, Minnetonka, MN, USA; Avaulta® ‐ Bard, Covington, LA, USA), or companies have excluded transvaginal utilisation of the mesh product (Gynemesh PS, Gynecare/Ethicon). The reviewer needs to be mindful when reading this review that the data presented include some products that are no longer available for use.

How the intervention might work

The aim of surgery ‐ to improve quality of life ‐ is achieved by:

restoration of normal vaginal anatomy;

restoration or maintenance of normal bladder function;

restoration or maintenance of normal bowel function; or

restoration or maintenance of normal sexual function.

Why it is important to do this review

The wide variety of surgical treatments available for prolapse indicates lack of consensus as to the optimal treatment. No consensus guidelines have been published in the available literature, and treatment is based on evidence from studies of mixed type and quality (Carey 2001). Provided that a sufficient number of trials of adequate quality have been conducted, the most reliable evidence is likely to come from the findings of randomised controlled trials. We conducted this review to gather evidence that would help review authors identify optimal practice while highlighting areas in which further research is needed.

This review should be read as part of a series of six Cochrane reviews related to the surgical management of prolapse, including:

surgery for women with anterior compartment prolapse;

surgery for women with posterior compartment prolapse;

surgery for women with apical compartment prolapse;

continence outcomes in pelvic organ prolapse;

native tissue, biological grafts or mesh for transvaginal prolapse surgery (Maher 2016); and

perioperative interventions at prolapse surgery.

Objectives

To determine the safety and effectiveness of surgery for anterior compartment prolapse.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with 20 or more patients in each arm, in which at least one arm provided a surgical intervention for pelvic organ prolapse.

Types of participants

Adult women seeking treatment for symptomatic anterior compartment pelvic organ prolapse. Both primary prolapse and recurrent prolapse were considered.

Types of interventions

Anterior compartment pelvic organ prolapse includes cystocele, urethrocele and a paravaginal defect for which both vaginal and abdominal surgeries were the primary inclusion criteria. Included trials performed interventions solely for anterior compartment prolapse or for concomitant prolapse or incontinence. Comparison interventions included no treatment, conservative management and use of a mechanical device or an alternative approach to surgery.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

1. Awareness of prolapse: any affirmative response to questions related to awareness of prolapse or vaginal bulge, or any affirmative response to question three of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI‐20): “Do you usually have a bulge or something falling out that you can see or feel in the vaginal area?”

2. Repeat surgery

2.1 Repeat surgery for prolapse 2.2 Repeat surgery for stress urinary incontinence

2.3 Repeat surgery for prolapse, stress urinary incontinence or mesh exposure (composite outcome), if relevant

3. Recurrent anterior prolapse ‐ defined as any stage 2 or greater anterior vaginal prolapse (Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ): prolapse 1 cm above or below the hymen)

Secondary outcomes

4. Adverse events

Outcomes to be reported include but are not limited to:

4.1 death (related to surgery);

4.2 mesh exposure;

4.3 injury to bladder (cystotomy);

4.4 injury to bowel (enterotomy); or

4.5 repeat surgery for mesh exposure.

5. Prolapse outcomes

5.1 Objective failure

5.1.1 Stage 2 or greater apical compartment prolapse (point C at or beyond 1 cm inside the introitus)

5.1.2 Stage 2 or greater posterior vaginal compartment prolapse (point Bp at or beyond 1 cm inside the introitus)

5.1.3 POPQ system scores: POPQ scores include nine measurements of the vagina performed to quantify and describe vaginal prolapse. For simplicity, we report four of these basic measurements

5.1.3.a Point Ba on POPQ (range ‐3 to +10 cm): Point Ba is approximately mid‐point on the anterior vaginal wall

5.1.3.b Point Bp on POPQ (range ‐3 to +10 cm): Point Bp is approximately mid‐point on the posterior vaginal wall

5.1.3.c Point C on POPQ (range ‐10 cm to non‐determined limit): Point C describes the vaginal apex (upper vagina)

5.1.3.d Total vaginal length (TVL) in cm (range 0 to 14 cm): TVL is the length from the vaginal entrance to the apex (cervix or vaginal cuff)

6. Bladder function

6.1 Stress urinary incontinence

6.2 De novo stress urinary incontinence

6.3 Surgery for stress urinary incontinence

6.4 De novo bladder overactivity or urge incontinence

6.5 Urinary voiding dysfunction

7. Bowel function

7.1 De novo faecal incontinence

7.2 De novo obstructed defecation

7.3 Constipation

8. Sexual function

8.1 Dyspareunia

8.2 De novo dyspareunia

8.3 Prolapse and Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ‐12; range 0 to 48): Higher score indicates better sexual function

9. Quality of life and satisfaction

Outcomes to be reported include but are not limited to:

9.1 Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI‐I) questionnaire (data presented on 7‐point Likert scale): Responses of "much" or "very much" better were considered affirmative and are presented as dichotomous outcomes;

9.2 Prolapse Quality of Life (PQOL) questionnaire (range 0 to 100): Higher score indicates greater dysfunction;

9.3 Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI‐20; range 0 to 300): Higher score indicates greater dysfunction;

9.4 Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ‐7; range 0 to 300): Higher score indicates greater dysfunction; and

9.5 International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaires (ICIQ; variable range): Higher score indicates greater dysfunction.

10. Measures associated with surgery

10.1 Operating time (minutes)

10.2 Length of hospital stay (days)

10.3 Blood transfusion (%)

Search methods for identification of studies

We imposed no language limits and no other limits on any of the searches detailed below.

Electronic searches

This review has drawn on the search strategy developed in consultation with the Cochrane Incontinence Review Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator. We identified relevant trials from the Incontinence Group Specialised Register of controlled trials, which is described, along with the Review Group search strategy, under the Group module in the Cochrane Library. This Register contains trials identified by a search of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and by a handsearch of journals and conference proceedings. We searched the Incontinence Group Specialised Register using the keyword system of the Group (all searches were based on the keyword field of Reference Manager 12, Thomson Reuters). Search terms used were as follows: ({design.cct*} OR {design.rct*}) AND ({topic.prolapse*}) AND ({intvent.surg*}), and the search date was 23 August 2016.

Trials in the Incontinence Group Specialised Register are also included in CENTRAL.

Review authors also undertook searches of health care‐related bibliographic databases such as clinicaltrials.gov (most recent, 1 August 2016), as per Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

We handsearched conference proceedings for the International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) and the International Continence Society (ICS) for podium presentations from 2012 to 15 February 2016. We searched the reference lists of relevant articles and contacted researchers in the field (Moher 2009).

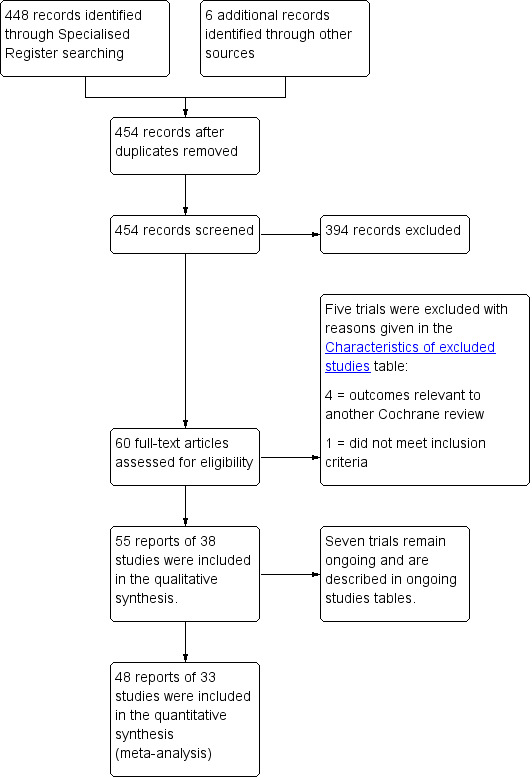

We constructed a PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses) chart (Moher 2009) to present search flow.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors assessed titles and, if available, abstracts of all possibly eligible studies for compliance with the inclusion criteria for this review. Two or more review authors independently assessed full reports of each study likely to be eligible for inclusion. We have listed excluded studies along with reasons for their exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

Two or more review authors independently extracted and compared data to ensure accuracy. We resolved discrepancies by discussion or by consultation with a third party. When trial data were not reported adequately, we attempted to acquire the necessary information from the trialist.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors used the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) to independently examine studies for risk of bias by assessing selection (random sequence generation and allocation concealment); performance (blinding of participants and personnel); detection (blinding of outcome assessors); attrition (incomplete outcome data); reporting (selective reporting); and other bias. We planned to resolve disagreements by discussion or by consultation with a third review author. We described all judgements fully and presented our conclusions in the Risk of bias table, which we incorporated into our interpretation of review findings via sensitivity analyses (see below).

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data, we used numbers of events in the control and intervention groups of each study to calculate Mantel‐Haenszel risk ratios (RRs). For continuous data, if all studies reported exactly the same outcomes, we calculated mean differences (MDs) between treatment groups. If similar outcomes were reported on different scales, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD). We presented 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all outcomes, and we compared the magnitude and direction of effect reported by studies with how they are presented in the review, while taking account of legitimate differences.

Unit of analysis issues

All analyses were performed per woman randomised.

Dealing with missing data

We analysed the data on an intention‐to‐treat basis as far as possible (once randomised to an intervention, participants were analysed because intervention and analysis include all randomised participants) and attempted to obtain missing data from the original trialist. When these could not be obtained, we analysed only available data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered whether clinical and methodological characteristics of the included studies were sufficiently similar for meta‐analysis to provide a clinically meaningful summary. We assessed statistical heterogeneity by measuring I2. We regarded an I2 measurement greater than 50% as indicating substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2003).

Assessment of reporting biases

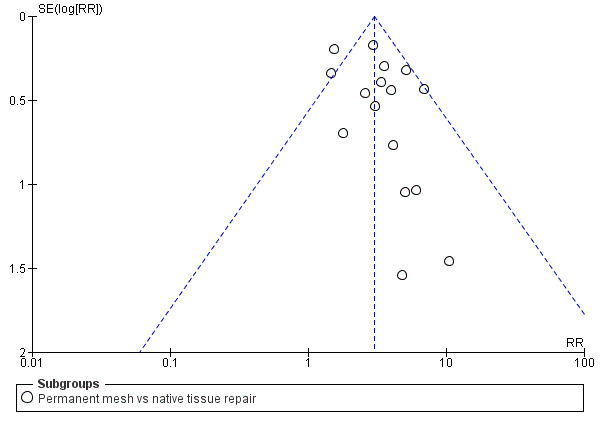

In view of the difficulty of detecting and correcting for publication bias and other reporting biases, review authors aimed to minimise their potential impact by ensuring a comprehensive search for eligible studies and by being alert for duplication of data. If we included 10 or more studies in an analysis, we used a funnel plot to explore the possibility of small‐study effects (i.e. a tendency for estimates of the intervention effect to be more beneficial in smaller studies).

Data synthesis

If studies were sufficiently similar, we combined the data using RevMan software (RevMan 2014) and a fixed‐effect model for the following comparisons.

Native tissue versus biological graft.

Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh.

Native tissue versus absorbable mesh.

One graft versus another graft for anterior compartment prolapse.

Vaginal repair versus abdominal repair.

Native tissue repair versus graft repair for anterior and/or posterior prolapse.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

When data were available, we conducted subgroup analyses to identify separate evidence for primary outcomes within the following subgroups.

Native tissue versus biological graft in studies using porcine dermis graft (compared with studies using other types of biological graft).

Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh in studies of mesh currently available on the market.

If we detected substantial heterogeneity, we explored possible explanations in sensitivity analyses. We took statistical heterogeneity into account when interpreting the results, especially if we noted variation in the direction of effect. When concern regarding heterogeneity persisted, we used a random‐effects model.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses for the primary outcomes, provided data were sufficient (five or more studies), to determine whether the conclusions were robust to arbitrary decisions made regarding eligibility and analysis. These analyses included consideration of whether review conclusions would have differed if:

a random effects model had been adopted; or

the summary effect measure had been odds ratio rather than risk ratio.

Overall quality of the body of evidence: 'Summary of findings' table

We prepared a 'Summary of findings' table using GRADEPRO software (GRADEpro GDT 2014), in accordance with Cochrane methods (Higgins 2011). In this table, we evaluated the overall quality of the body of evidence for main review outcomes (awareness of prolapse, repeat surgery for prolapse or stress urinary incontinence, recurrent anterior compartment prolapse, dyspareunia) with regard to the main review comparisons (native tissue vs biological graft, native tissue vs polypropylene mesh, native tissue vs absorbable mesh) by using GRADE criteria (study limitations (i.e. risk of bias), consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) (Atkins 2004). We justified, documented and incorporated judgements about evidence quality (high, moderate, low) into reporting of results for each outcome. Two review authors working independently assessed GRADE ratings and resolved disagreements by discussion.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We included in this report full reports on 33 studies (Ali 2006 abstract;Allahdin 2008;Altman 2011; Carey 2009;Colombo 2000;Dahlgren 2011; Delroy 2013; De Ridder 2004 abstract;De Tayrac 2013;El‐Nazer 2007;Farthmann 2012;Feldner 2010; Gandhi 2005; Guerette 2009;Gupta 2014;Hviid 2010; Lamblin 2014;Menefee 2011; Meschia 2007; Minassian 2010 abstract; Natale 2009;Nguyen 2008;Nieminen 2008; Robert 2014;Rudnicki 2014;Sand 2001; Sivaslioglu 2008; Tamanini 2015;Thijs 2010 abstract; Turgal 2013;Vollebregt 2011; Weber 2001;Withagen 2011). Two studies (Ek 2010; Ek 2011) are ancillary reports to Altman 2011, and three trials (Allahdin 2008; Dahlgren 2011; Menefee 2011) contributed to multiple comparisons.

The flow of literature through the assessment process is shown in the PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1).

1.

PRISMA study flow diagram for 2016 review.

No study authors reported median follow‐up of less than one year, and the following study authors reported extended reviews: 2 years ‐ Delroy 2013; De Ridder 2004 abstract;Guerette 2009; Meschia 2007;Minassian 2010 abstract;Tamanini 2015; 3 years ‐ Farthmann 2012; Natale 2009; Nieminen 2008; and 5 years ‐ Colombo 2000.

Included studies

Study design and setting

In total, 33 randomised controlled trials were conducted in 15 countries (Italy, USA, Argentina, Australia, Belgium, the Netherlands, Finland, India, Germany, Chile, France, Norway, Denmark, Sweden and Turkey). Fourteen trials were multi‐centre randomised trials (Altman 2011; Dahlgren 2011: De Tayrac 2013; Farthmann 2012; Guerette 2009; Lamblin 2014; Menefee 2011; Meschia 2007; Natale 2009; Nieminen 2008; Rudnicki 2014; Thijs 2010 abstract; Vollebregt 2011; Withagen 2011). All studies used a parallel design.

Participants

We evaluated in this review 33 randomised controlled trials evaluating 3332 women in the surgical management of anterior compartment prolapse.

Interventions

Eight articles (Dahlgren 2011; Feldner 2010; Gandhi 2005; Guerette 2009; Hviid 2010; Menefee 2011; Meschia 2007; Robert 2014) compared native tissue repair anterior colporrhaphy (n = 413) versus various biological grafts (n = 450) and assessed the following interventions. Porcine dermis (Pelvicol) was utilised in four trials (Dahlgren 2011; Hviid 2010; Menefee 2011; Meschia 2007), small intestine submucosa in two (Feldner 2010; Robert 2014), cadaveric fascia lata patch in one (Gandhi 2005) and bovine pericardium collagen in one (Guerette 2009). Meschia 2007 evaluated only primary anterior compartment prolapse, and Dahlgren 2011 included only those who had undergone at least one failed prior surgical intervention in the treated compartment. Hviid 2010 included only those with anterior compartment prolapse and excluded those undergoing concomitant surgery.

-

Sixteen trials (Ali 2006 abstract; Altman 2011; Delroy 2013; De Tayrac 2013; El‐Nazer 2007; Gupta 2014; Lamblin 2014; Menefee 2011; Nieminen 2008; Nguyen 2008; Rudnicki 2014; Sivaslioglu 2008; Tamanini 2015; Thijs 2010 abstract; Turgal 2013; Vollebregt 2011) assessed anterior colporrhaphy (n = 926) versus permanent polypropylene mesh (n = 959). Each study evaluated a relatively similar cohort of women; however, the following exclusions were introduced in individual trials: prior graft surgery (Lamblin 2014; Nguyen 2008; Tamanini 2015), concomitant surgery (Altman 2011; Nieminen 2008; Rudnicki 2014), prior prolapse surgery (Rudnicki 2014; Turgal 2013; Vollebregt 2011), urinary incontinence (Turgal 2013) and bladder injury at surgery (De Tayrac 2013).

Many of the mesh products that we evaluated have been voluntarily removed from the market, including Prolift (Gynecare/Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA) (Altman 2011), Perigee (American Medical Systems, Minnetonka, MN, USA) (Lamblin 2014; Nguyen 2008; Thijs 2010 abstract) and Avaulta (Bard, Covington, LA, USA) (Rudnicki 2014; Vollebregt 2011). In addition, some companies have excluded transvaginal utilisation of mesh products, including Gynemesh PS and Gynecare/Ethicon (Ali 2006 abstract; Carey 2009; El‐Nazer 2007; Gupta 2014).

Three trials (Allahdin 2008; Sand 2001; Weber 2001) evaluated effects of absorbable polyglactin (Vicryl) mesh inlay used to augment prolapse repair. Data from two trials were aggregated in a meta‐analysis, as they included follow‐up of at least 12 months (Sand 2001; Weber 2001), and the non‐mesh arms from one trial (traditional anterior vaginal wall repair and ultra‐lateral anterior vaginal wall repair) were aggregated for comparison with the mesh arm in one trial (Weber 2001).

Four trials compared one type of graft versus another for management of anterior compartment prolapse. Biological graft (Pelvicol) was compared with polypropylene mesh by Menefee 2011 and Natale 2009, and with absorbable mesh (polyglactin) by De Ridder 2004 abstract. Natale included only those with recurrent prolapse and reported three‐year outcomes. Farthmann 2012 compared a conventional polypropylene mesh with lighter‐weight polypropylene mesh with an absorbable coating.

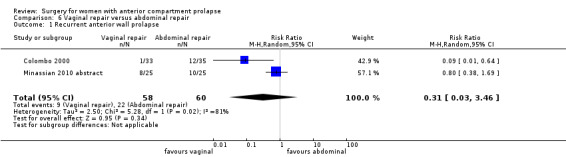

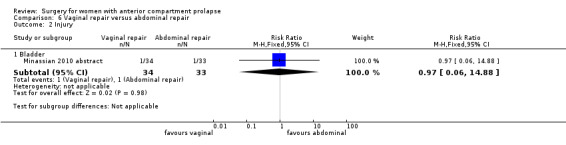

Two studies (Colombo 2000; Minassian 2010 abstract) are included in this subgroup. Both compared anterior colporrhaphy and abdominal paravaginal repair/Burch as the interventions. In Colombo 2000, vaginal interventions included vaginal hysterectomy and uterosacral colpopexy as compared with abdominal group abdominal hysterectomy and uterosacral suspension. In Minassian 2010 abstract, the non‐randomised surgery in both groups was a sacral colpopexy.

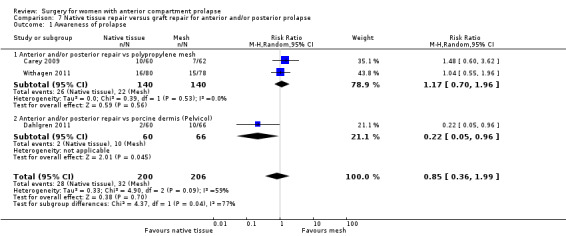

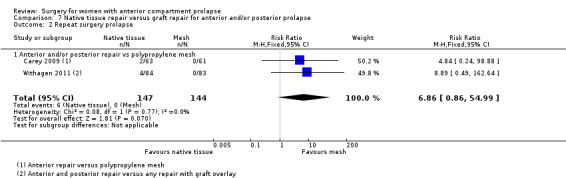

Four trials (Allahdin 2008; Carey 2009; Dahlgren 2011; Withagen 2011) were included in another subgroup. Prior prolapse surgery was an inclusion criterion for Withagen 2011, and prior prolapse surgery in the treated compartment was an inclusion criterion for Dahlgren 2011. Native tissue repair in the anterior or posterior compartment was compared with absorbable mesh in Allahdin 2008, permanent polypropylene mesh in Carey 2009 and Withagen 2011 and porcine dermis in Dahlgren 2011.

Outcomes

Trialists reported a wide variety of prolapse outcomes that broadly followed the outcomes listed under Methods. No studies reported all outcomes, and no studies reported no outcomes.

Fourteen trials (Altman 2011; Dahlgren 2011; Delroy 2013; De Tayrac 2013; El‐Nazer 2007; Gandhi 2005; Gupta 2014; Hviid 2010; Lamblin 2014; Meschia 2007; Nieminen 2008; Robert 2014; Turgal 2013; Vollebregt 2011) reported on awareness of prolapse.

Twelve trials (Altman 2011; Delroy 2013; De Tayrac 2013; Lamblin 2014, Menefee 2011; Nguyen 2008; Nieminen 2008; Rudnicki 2014; Sivaslioglu 2008; Tamanini 2015; Thijs 2010 abstract; Vollebregt 2011) reported on repeat surgery for prolapse, stress urinary incontinence or mesh exposure (composite outcome).

Seven trials (Delroy 2013; De Tayrac 2013; El‐Nazer 2007; Feldner 2010; Lamblin 2014; Rudnicki 2014; Tamanini 2015) reported on repeat anterior compartment prolapse on objective examination.

Full details of the included trials are given in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Excluded studies

Overall, we excluded five studies from the review (Heinonen 2011; Kringel 2010; Tincello 2009; Van Der Steen 2011; Weemhoff 2011); details are given in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

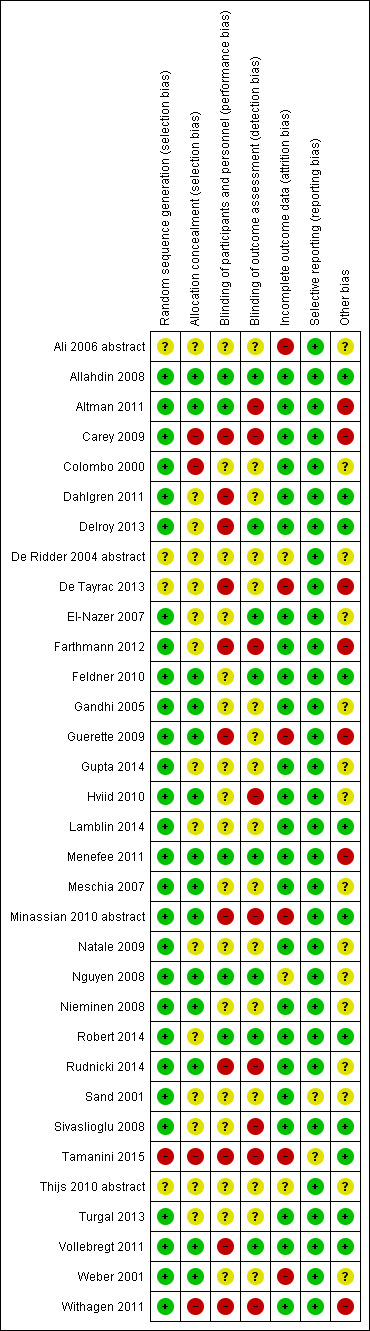

Fifteen of the RCTs (Allahdin 2008; Altman 2011; Dahlgren 2011; Delroy 2013; El‐Nazer 2007; Feldner 2010; Gandhi 2005; Guerette 2009; Hviid 2010; Meschia 2007; Minassian 2010 abstract; Nguyen 2008; Nieminen 2008; Rudnicki 2014; Weber 2001) provided sufficient detail by adequately describing the randomisation process and by confirming that secure concealment of the randomisation process was used, for example, allocation by a remote person or by sealed envelopes.

Of the remainder, 11 trials (Carey 2009; De Ridder 2004 abstract; Farthmann 2012; Gupta 2014; Lamblin 2014; Menefee 2011; Sand 2001; Sivaslioglu 2008; Tamanini 2015; Vollebregt 2011; Withagen 2011) utilised computer‐generated number lists, but it was unclear whether allocation was concealed before assignment. Randomisation was performed by drawing lots in De Tayrac 2013, and Tamanini 2015 described a raffle used in the randomisation process. In Colombo 2000, randomisation was appropriate; however, the open randomisation list ensured high risk of allocation bias. Neither randomisation nor allocation concealment was reported in the final two reports presented as abstracts El‐Nazer 2007; Minassian 2010 abstract.

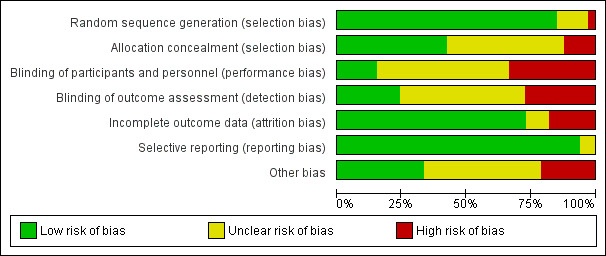

Review authors rated 28 RCTs as having low risk of bias related to sequence generation, four as unclear risk and one as high risk. We rated 14 trials as having low risk of bias related to allocation concealment, 15 as unclear risk and four as high risk.

Blinding

Women and surgeons could not be blinded to the procedure when different surgical routes were compared (Colombo 2000; Delroy 2013; Minassian 2010 abstract; Nguyen 2008; Nieminen 2008; Rudnicki 2014; Tamanini 2015). Three trials (Allahdin 2008; Menefee 2011; Nguyen 2008) blinded participants and the postoperative reviewer. Non‐surgeons conducted outcome assessments in five trials (Allahdin 2008; El‐Nazer 2007; Feldner 2010; Natale 2009; Weber 2001). These findings, which are summarised in Figure 2 show that five trials were at low risk of performance bias, 17 at unclear risk and 11 at high risk. We rated eight trials as having low risk of detection bias, 16 unclear risk and nine high risk.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Incomplete outcome data

Loss to follow‐up was a variable problem, ranging from zero (Allahdin 2008) to 53% in Guerette 2009 (49/93) at two years. Weber 2001 reported a statistically significantly greater loss to follow‐up in one arm of the trial (ultra‐lateral anterior vaginal wall repair). Twenty‐four trials were at low risk of attrition bias, three at uncertain risk and six at high risk.

Selective reporting

Generally, the level of reporting was adequate for one trial (Altman 2011), which did not report the rate of mesh exposure. However, data were supplied as personal communication. We rated all trials as having low risk of bias in this domain.

Other potential sources of bias

Thirteen trials (Allahdin 2008; Altman 2011; Dahlgren 2011; Delroy 2013; Feldner 2010; Gandhi 2005; Guerette 2009; Hviid 2010; Lamblin 2014; Meschia 2007; Nguyen 2008; Nieminen 2008; Rudnicki 2014) provided a CONSORT flow diagram, randomisation techniques, allocation statements and sample size calculations. These findings are summarised in Figure 3.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

All trials except three reported baseline descriptive characteristics that were equally distributed. Sand 2001 reported that previous hysterectomy was more common in the mesh overlay group. Withagen 2011 reported that those in the native tissue group had a greater degree of prolapse than those in the mesh group at point A posterior (Ap), point B posterior (Bp) and genital hiatus (GH), and that prior sacral colpopexy was three times more frequent in the mesh group than in the native tissue group. Lamblin 2014 reported that the rate of hysterectomy performed as concomitant surgery was 77% in the native tissue group versus 33% in the transvaginal polypropylene mesh group (P < 0.001).

All trials but one (De Ridder 2004 abstract) reported preoperative prolapse status, and two trials (Ali 2006 abstract; Sand 2001) did not specifically report equal distribution and severity of prolapse between groups. In one trial (Weber 2001), 7% of women had stage 1 anterior vaginal wall prolapse preoperatively (at the time of inclusion), which would have been classified as a postoperative success.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

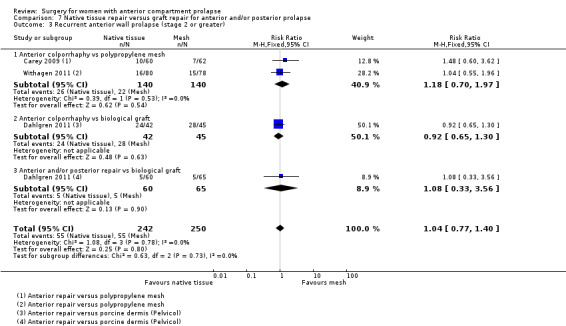

1 Native tissue versus biological graft

Eight trials (Dahlgren 2011; Feldner 2010; Gandhi 2005; Guerette 2009; Hviid 2010; Menefee 2011; Meschia 2007; Robert 2014) compared native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy) (n = 384) versus biological grafts (n = 422).

Primary outcomes

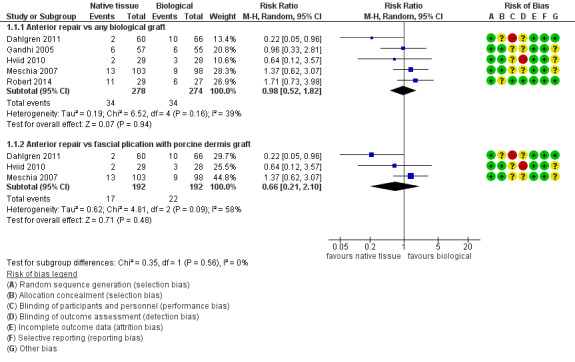

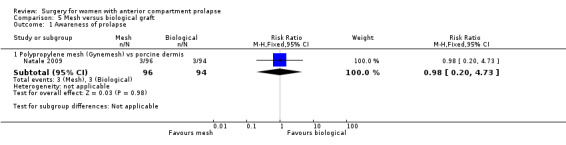

1.1 Awareness of prolapse (1 to 2 years)

1.1.1 Native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy) versus any biological graft

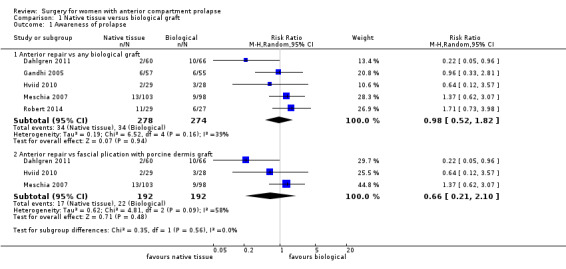

Women showed no difference in awareness of prolapse between native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy) and any biological graft (average RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.82; five RCTs; n = 552; I2 = 39%; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.1; Figure 4). These data suggest that if awareness of prolapse after biological graft occurs in 12% of women, then 7% to 23% would be aware of prolapse after native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Native tissue versus biological graft, Outcome 1 Awareness of prolapse.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Native tissue versus biological graft, outcome: 1.1 Awareness of prolapse.

1.1.2 Subgroup analysis by type of graft

Results showed no difference in awareness of prolapse between native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy) and biological graft with porcine dermis (average RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.21 to 2.10; three RCTs; n = 384; I2 = 58%; Analysis 1.1). The test for subgroup differences showed no evidence of differences between studies that used porcine dermis and those using other types of biological graft (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 1.16; df = 1 (P = 0.28); I² = 13.6%).

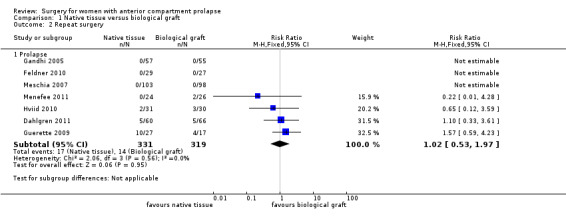

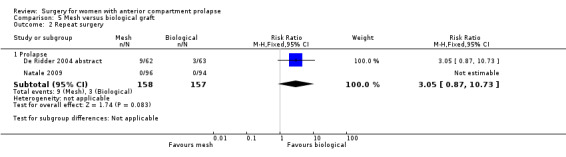

1.2 Repeat surgery (1 to 2 years)

1.2.1 Repeat surgery for prolapse

We found no evidence of a difference between native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy) and biological graft (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.97; seven RCTs; n = 650; I2 = 0%; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.2). Data suggest that if repeat prolapse surgery after biological graft was required in 4% of women, then 2% to 9% would undergo repeat prolapse surgery after native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Native tissue versus biological graft, Outcome 2 Repeat surgery.

1.2.2 Repeat surgery for stress urinary incontinence

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

1.2.3 Repeat surgery for prolapse, stress urinary incontinence or mesh exposure (composite outcome)

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

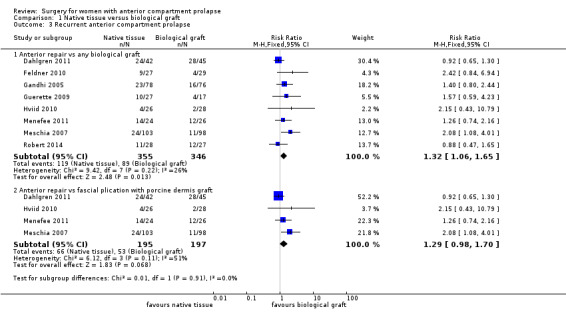

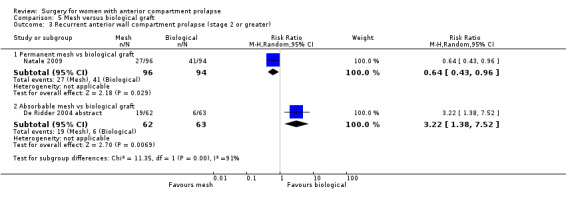

1.3 Recurrent anterior wall prolapse (1 to 2 years)

1.3.1 Anterior compartment

Native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy) was associated with increased risk of recurrent anterior wall prolapse compared with biological graft (RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.65; eight RCTs; n = 701; I2 = 26%; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.3). These data suggest that if recurrent anterior wall prolapse after biological graft occurs in 26% of women, then 27% to 42% would have recurrence after native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Native tissue versus biological graft, Outcome 3 Recurrent anterior compartment prolapse.

1.3.2 Subgroup analysis by type of graft

Studies provided no evidence of a difference in recurrent anterior wall prolapse between native tissue repair and porcine dermis repair (RR 1.29, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.70; four RCTs; n = 392; I2 = 51%; Analysis 1.3). The test for subgroup differences showed no evidence of a difference between studies that used porcine dermis and those using other types of biological graft (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 0.05, df = 1 (P = 0.83); I² = 0%).

Secondary outcomes

1.4 Adverse events

1.4.1 Death (related to surgery)

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

1.4.2 Mesh exposure

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

1.4.3 Injury to bladder (cystotomy)

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

1.4.4 Injury to bowel (enterotomy)

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

1.4.5 Repeat surgery for mesh exposure

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

1.5 Objective failure

1.5.1 Stage 2 or greater apical compartment prolapse (point C at or beyond 1 cm inside the introitus)

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

1.5.2 Stage 2 or greater posterior vaginal compartment prolapse (point Bp at or beyond 1 cm inside the introitus)

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

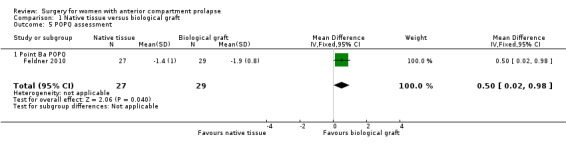

1.5.3 Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ) system scores

1.5.3.1 Point Ba ‐ Native tissue repair was associated with less pronounced Ba score compared with biological graft as reported in a single trial (MD 0.50, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.98; one RCT; n = 56; Analysis 1.5)

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Native tissue versus biological graft, Outcome 5 POPQ assessment.

1.5.3.2 Point Bp ‐ Studies provided no data for this outcome

1.5.3.3 Point C ‐ Studies reported no data for this outcome

1.5.3.4 Total vaginal length ‐ Studies provided no data for this outcome

1.6 Bladder function

1.6.1 Stress urinary incontinence (one to two years)

Studies provided no evidence of a postoperative difference in stress urinary incontinence between native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy) and biological graft (RR 1.44, 95% CI 0.79 to 2.64; two RCTs; n = 218; I2 = 0%; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.4). These data suggest that if the rate of stress urinary incontinence is 13% in patients receiving a biological graft, then 10% to 34% have stress urinary incontinence after a native tissue repair.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Native tissue versus biological graft, Outcome 4 Stress urinary incontinence.

1.6.2 De novo stress urinary incontinence

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

1.6.3 De novo urge incontinence (one year)

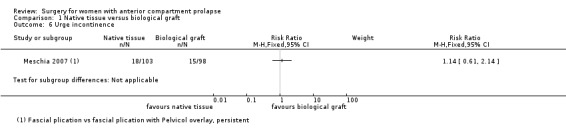

Studies provided no evidence of a postoperative difference in urge incontinence between native tissue repair and biological graft (RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.61 to 2.14; one RCT; n = 201; Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Native tissue versus biological graft, Outcome 6 Urge incontinence.

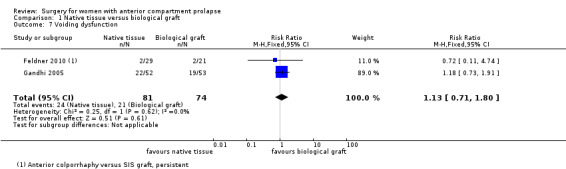

1.6.4 Urinary voiding dysfunction (one year)

Studies provided no evidence of a postoperative difference between native tissue repair and biological graft in voiding dysfunction (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.80; two RCTs; n = 155; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Native tissue versus biological graft, Outcome 7 Voiding dysfunction.

1.7 Bowel function

1.7.1 De novo faecal incontinence

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

1.7.2 De novo obstructed defecation

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

1.7.3 Constipation

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

1.8 Sexual function

1.8.1 Dyspareunia (one to two years)

Studies provided no evidence of a difference between native tissue repair and biological graft (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.93; two RCTs; n= 151; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.8). Data suggest that if the rate of dyspareunia is 15% after biological graft, then 6% to 29% would have dyspareunia after native tissue repair.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Native tissue versus biological graft, Outcome 8 Dyspareunia.

1.8.2 De novo dyspareunia

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

1.8.3 Prolapse and Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ)

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

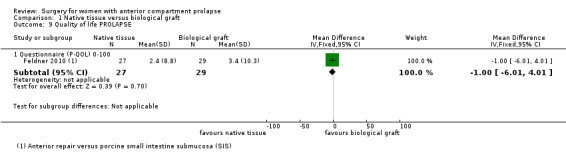

1.9 Quality of life and satisfaction

1.9.1 Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PG1‐1) ‐ Studies provided no data for this outcome

1.9.2 Prolapse Quality of Life Questionnaire (PQOL): Studies provided no evidence of a difference in quality of life outcomes between native tissue repair and biological graft when the PQOL was used in a single study (MD ‐1.00, 95% CI ‐6.01 to 4.01; one RCT; n = 56; Analysis 1.9)

1.9.3 Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI‐20) ‐ Studies provided no data for this outcome

1.9.4 Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ‐7) ‐ Studies provided no data for this outcome

1.10. Measures associated with surgery

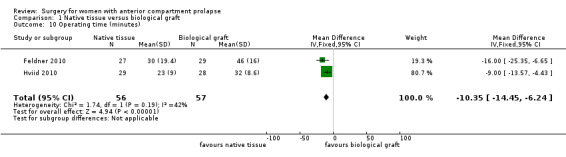

1.10.1 Operating time (minutes)

Native tissue repair was associated with reduced operating time compared with use of a biological graft (MD ‐10.35, 95% CI ‐14.45 to 6.24; two RCTs; n = 113; I2 = 42%; Analysis 1.10).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Native tissue versus biological graft, Outcome 10 Operating time (minutes).

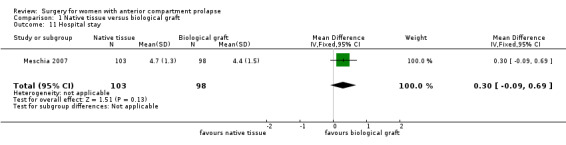

1.10.2 Length of hospital stay

Studies provided no evidence of a difference in length of hospital stay between native tissue repair and biological graft (MD 0.30 days, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.69; one RCT; n = 201; Analysis 1.11).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Native tissue versus biological graft, Outcome 11 Hospital stay.

1.10.3 Blood transfusion

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

We have summarised data outcomes in Table 1.

2 Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh

Fifteen trials (Ali 2006 abstract; Altman 2011; Delroy 2013; De Tayrac 2013; El‐Nazer 2007; Gupta 2014;Lamblin 2014;Menefee 2011; Nguyen 2008; Nieminen 2008; Rudnicki 2014; Sivaslioglu 2008; Tamanini 2015; Thijs 2010 abstract; Vollebregt 2011) assessed native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy) (n = 906) versus use of permanent polypropylene mesh (n = 949). Three studies (Allahdin 2008;Carey 2009;Withagen 2011) included both anterior and posterior prolapse.

Primary outcomes

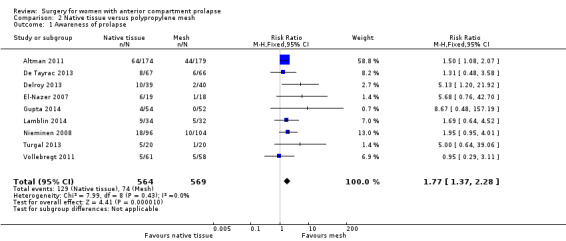

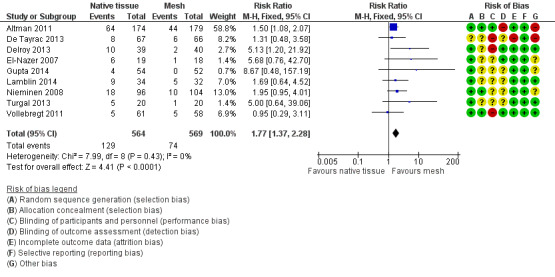

2.1 Awareness of prolapse (one to three years)

Awareness of prolapse was more likely after native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy) than after mesh repair (RR 1.77, 95% CI 1.37 to 2.28; nine RCTs; n = 1133; I2 = 0%; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 2.1). This suggests that if awareness of prolapse after polypropylene mesh repair occurs in 13% of women, then 18% to 30% would develop awareness of prolapse after native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy) (Figure 5).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh, Outcome 1 Awareness of prolapse.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh, outcome: 2.1 Awareness of prolapse.

2.2 Repeat surgery (one to three years)

2.2.1 Repeat surgery for prolapse

Repeat surgery for prolapse was more likely after native tissue repair than after mesh repair (RR 2.03, 95% CI 1.15 to 3.58; 11 RCTs; n = 1461; I2 = 39%; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 2.2). This suggests that if 2% underwent repeat surgery for prolapse after polypropylene mesh repair, then 2% to 7% would require surgery after native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh, Outcome 2 Repeat surgery.

2.2.2 Repeat surgery for stress urinary incontinence (one to three years)

Studies provided no evidence of a difference in the rate of repeat surgery for urinary stress urinary incontinence between native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy) and polypropylene mesh repair (RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.60 to 2.36; five RCTs; n = 881; I2 = 30%; Analysis 2.2).

2.2.3 Reoperation rate for prolapse, stress urinary incontinence or mesh exposure (composite outcome)

Repeat surgery for prolapse, stress urinary incontinence or mesh exposure (composite outcome) was less likely after native tissue repair than after polypropylene mesh repair (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.83; 12 RCTs; n = 1527; I2 = 45%; Analysis 2.2). This suggests that if 10% underwent subsequent surgery after polypropylene mesh repair, then 4% to 8% would require subsequent surgery after native tissue repair.

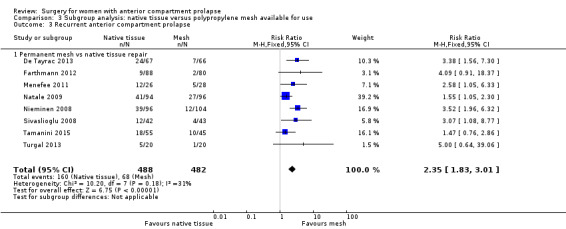

2.3 Recurrent anterior wall prolapse (one to three years)

Recurrence of anterior wall prolapse was more likely after native tissue repair than after polypropylene mesh repair (RR 3.01, 95% CI 2.52 to 3.60; 16 RCTs; n = 1976; I2 = 39%; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 2.3;Figure 6). This suggests that if recurrent anterior wall prolapse occurred in 13% of women after polypropylene mesh repair, then 32% to 45% would have recurrence after native tissue repair.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh, Outcome 3 Recurrent anterior compartment prolapse.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh, outcome: 2.3 Recurrent anterior compartment prolapse.

Secondary outcomes

2.4 Adverse events

2.4.1 Death (related to surgery)

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

2.4.2 Mesh exposure

The mesh exposure rate after transvaginal polypropylene mesh was 11.3% (101/896) at one to three years (Table 4).

1. Anterior transvaginal mesh exposure rate.

| Study ID | Mesh exposure | Mesh repairs |

| Al‐Nazer 2007 | 1 | 21 |

| Ali 2006 abstract | 3 | 46 |

| Altman 2011 | 21 | 183 |

| De Tayrac 2013 | 7 | 76 |

| Delroy 2013 | 2 | 40 |

| Gupta 2014 | 4 | 44 |

| Lamblin 2014 | 2 | 33 |

| Menefee 2011 | 5 | 28 |

| Nguyen 2008 | 2 | 37 |

| Nieminen 2008 | 18 | 104 |

| Rudnick 2014 | 12 | 78 |

| Sivaslioglu 2008 | 3 | 43 |

| Tamanini 2014 | 7 | 42 |

| Turgal 2014 | 3 | 20 |

| Thijs 2010 abstract | 9 | 48 |

| Vollebregt 2011 | 2 | 53 |

| Total | 101 | 896 |

| Anterior repair vs absorbable mesh | ||

| Sand 2001 | 0 | 73 |

| Weber 2001 | 1 | 26 |

2.4.3 Injury to bladder (cystotomy)

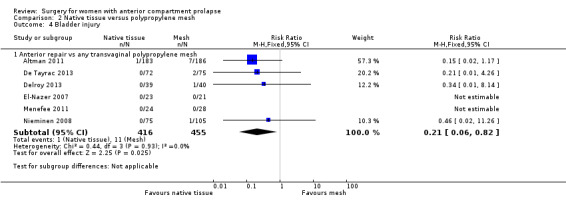

Intraoperative cystotomy was less likely after native tissue repair (1/416) than after polypropylene mesh repair (11/455) (RR 0.21, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.82; six RCTs; n = 871; I2 = 0%; Analysis 2.4). Wide confidence intervals reflect the low event rates for this outcome.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh, Outcome 4 Bladder injury.

2.4.4 Injury to bowel (enterotomy)

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

2.4.5 Repeat surgery for mesh exposure

The repeat surgery rate for mesh exposure was 7.3% (56/768) at one to three years (Table 5).

2. Reoperation for mesh exposure.

| Study ID | Surgery mesh exposure | Mesh repairs |

| Altman 2011 (1) | 6 | 183 |

| De Tayrac 2013 (2) | 4 | 76 |

| Delroy 2013 (3) | 2 | 40 |

| Gupta 2014 (4) | 2 | 44 |

| Nguyen 2008 (5) | 2 | 37 |

| Nieminen 2008 (6) | 14 | 104 |

| Rudnick 2014 (7) | 5 | 78 |

| Sivaslioglu 2008 (8) | 3 | 43 |

| Tamanini 2014 (9) | 7 | 42 |

| Turgal 2014 | 5 | 20 |

| Thijs 2010 abstract (10) | 4 | 48 |

| Vollebregt 2011 (11) | 2 | 53 |

| Total | 56 | 768 |

2.5 Objective failure

2.5.1 Stage 2 or greater apical compartment prolapse

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

2.5.2 Stage 2 or greater posterior vaginal compartment prolapse

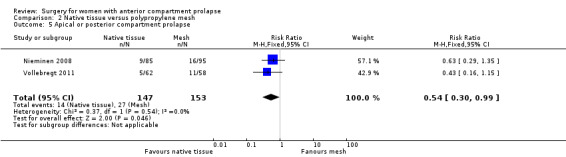

Studies provided no data for this outcome. Subsequent prolapse in the posterior or apical compartment was less likely after native tissue repair than after polypropylene mesh repair (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.99; two RCTs; n = 300; I2 = 0%; Analysis 2.5). This suggests that if 18% of women developed prolapse in the apical or posterior compartment on examination after polypropylene mesh repair, then 5% to 18% would develop apical or posterior compartment prolapse after native tissue repair.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh, Outcome 5 Apical or posterior compartment prolapse.

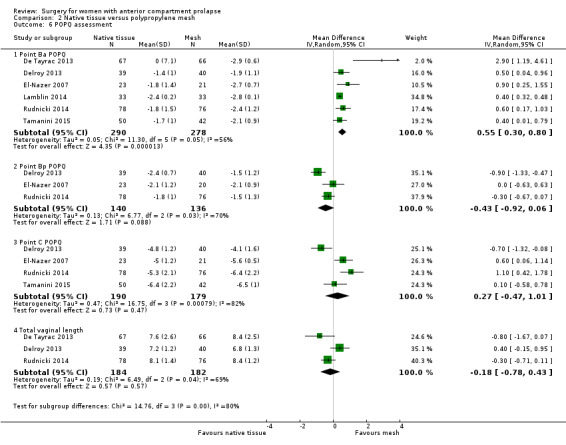

2.5.3 Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ) system scores

2.5.3.1 Point Ba (one to two years) ‐ Anatomical assessment based on POPQ revealed less support at point Ba (mid‐anterior vaginal wall) after native tissue repair than after polypropylene mesh (average MD 0.55 cm, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.80; six RCTs; n = 568; I2 = 56%; Analysis 2.6).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh, Outcome 6 POPQ assessment.

2.5.3.2 Point Bp (one to two years) ‐ Studies provided no evidence of a difference between native tissue repair and mesh repair for anatomical assessment based on POPQ at point Bp (average MD ‐0.43 cm, 95% CI ‐0.92 to 0.06; four RCTs; n = 355; I2 = 70%; Analysis 2.6).

2.5.3.3 Point C (one to two years) ‐ Studies provided no evidence of a difference between native tissue repair and mesh repair for anatomical assessment based on POPQ at point C (vaginal apex) (MD 0.27 cm, 95% CI ‐0.47 to 1.01; four RCTs; n = 369; I2 = 82%; Analysis 2.6).

2.5.3.4 Total vaginal length (one to two years) ‐ Studies reported no difference between native tissue repair and mesh repair for anatomical assessment based on total vaginal length (MD ‐0.18, 95% CI ‐0.78 to 0.43; three RCTs; n = 366; I2 = 69%; Analysis 2.6).

2.6 Bladder function

2.6.1 Stress urinary incontinence (one to three years)

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

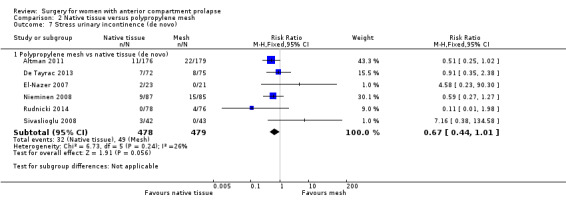

2.6.2 De novo stress urinary incontinence

Native tissue repair was associated with a reduction in de novo urinary stress incontinence compared with mesh repair (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.01; six RCTs; n = 957; I2 = 26%; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 2.7). This suggests that if after mesh repair 10% developed de novo stress urinary incontinence, then 5% to 10% would develop de novo stress urinary incontinence after native tissue repair.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh, Outcome 7 Stress urinary incontinence (de novo).

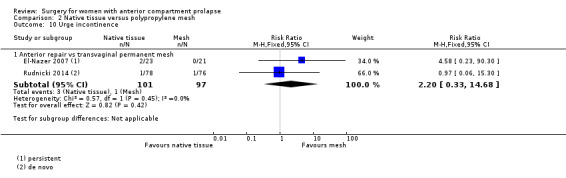

2.6.3 Urge incontinence (one year)

Studies provided no evidence of postoperative differences between groups in rate of urge incontinence (RR 2.20, 95% CI 0.33 to 14.68; two RCTs; n = 198; I2 = 0%; Analysis 2.10). Caution is advised in interpreting these results owing to low event rates and wide confidence intervals crossing the line of no effect, suggesting imprecision.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh, Outcome 10 Urge incontinence.

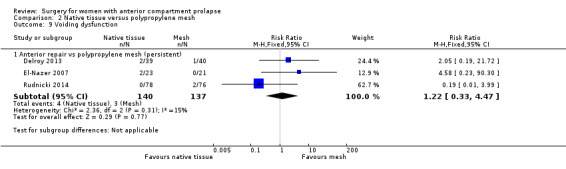

2.6.4 Urinary voiding dysfunction (one to two years)

Studies provided no evidence of postoperative differences between groups in rate of voiding dysfunction (RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.33 to 4.47; three RCTs; n = 277; I2 = 15%; Analysis 2.9). Caution is advised in interpreting these results owing to low event rates and wide confidence intervals crossing the line of no effect, suggesting imprecision.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh, Outcome 9 Voiding dysfunction.

2.7 Bowel function

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

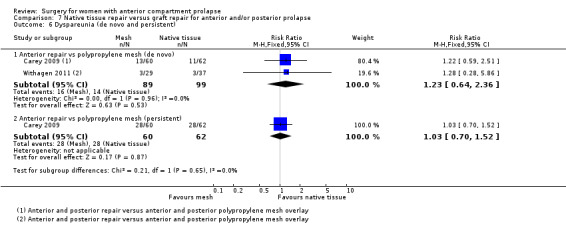

2.8 Sexual function

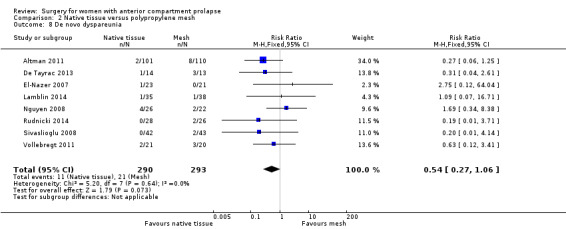

2.8.1 De novo dyspareunia (one to three years)

Studies provided no evidence of differences between groups in rate of de novo dyspareunia between native tissue repair and mesh repair (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.06; eight RCTs; n = 583; I2 = 0%; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 2.8). This suggests that if 7% developed de novo dyspareunia after mesh repair, then 2% to 8% would experience de novo dyspareunia after native tissue repair.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh, Outcome 8 De novo dyspareunia.

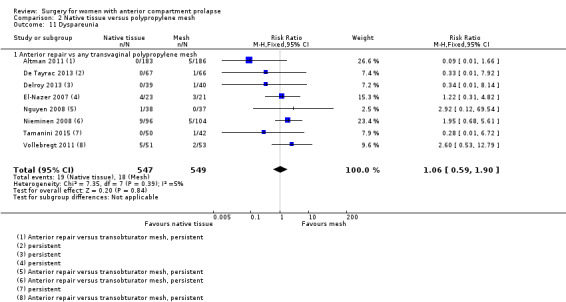

2.8.2 Dyspareunia (one to two years)

Studies provided no evidence of a postoperative difference in rate of dyspareunia between native tissue repair and mesh repair (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.90; eight RCTs; n = 1096; I2 = 5%; Analysis 2.11).

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh, Outcome 11 Dyspareunia.

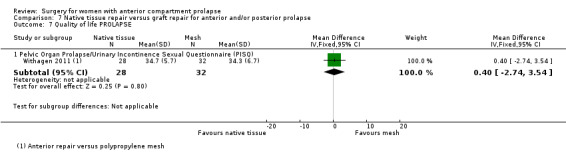

2.8.3 Prolapse and Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ) (one year)

Studies provided no evidence of differences between groups on the PISQ (MD ‐0.06, 95% CI ‐0.76 to 0.64; four RCTs; n = 741; I2 = 25%; Analysis 2.12.4).

2.12. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh, Outcome 12 Quality of life PROLAPSE.

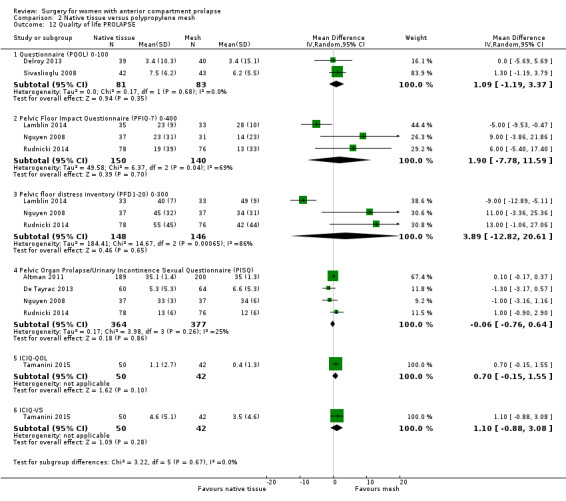

2.9 Quality of life and satisfaction

Quality of life questionnaires: Only four of the 15 studies (Ali 2006 abstract; El‐Nazer 2007; Gupta 2014; Vollebregt 2011) did not report a validated quality of life outcome.

2.9.1 Prolapse Quality of Life questionnaire (PQOL) (one to two years)

Studies provided no evidence of differences in PQOL scores between groups (MD 1.09, 95% CI ‐1.19 to 3.37; two RCTs; n = 164; I2 = 0%; Analysis 2.12).

2.9.2 Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ‐7) (one to two years)

Studies provided no evidence of differences between groups on the PFIQ‐7 (average MD 1.90, 95% CI ‐7.78 to 11.59; three RCTs; n = 290; I2 = 69%; Analysis 2.12).

2.9.3 Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI‐20) (one to two years)

Studies provided no evidence of differences between groups on the PFDI‐20 (average MD 3.89, 95% CI ‐12.82 to 20.61; three RCTs; n = 294; I2 = 86%; Analysis 2.12.3).

2.9.4 International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire (ICIQ) (one to two years)

Studies provided no evidence of differences between groups on the ICIQ (MD 0.70, 95% CI ‐0.15 to 1.55; one RCT; n = 92; Analysis 2.12) or in ICIQ vaginal symptoms (MD 1.10, 95% CI ‐0.88 to 3.08; one RCT; n = 92; Analysis 2.12).

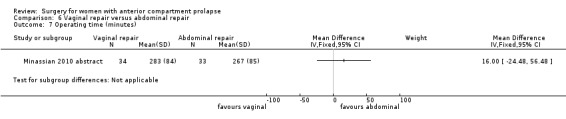

2.10 Perioperative outcomes

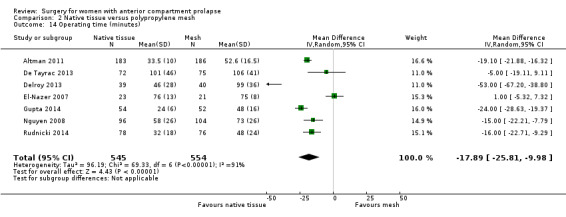

2.10.1 Operating time

Operating time was shorter after native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy) than after polypropylene mesh repair (MD ‐17.89 minutes, 95% CI ‐25.81 to ‐9.98; seven RCTs; n = 1099; I2 = 91%). Because of heterogeneity, we have not reported the data in a meta‐analysis (Analysis 2.14).

2.14. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh, Outcome 14 Operating time (minutes).

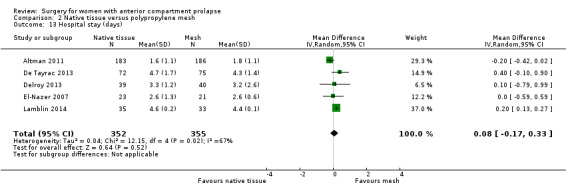

2.10.2 Hospital stay

Studies provided no evidence of differences between groups in hospital stay (MD 0.08 days, 95% CI ‐0.17 to 0.33; five RCTs; n = 707; I2 = 67%; Analysis 2.13).

2.13. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh, Outcome 13 Hospital stay (days).

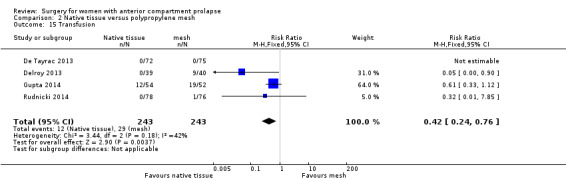

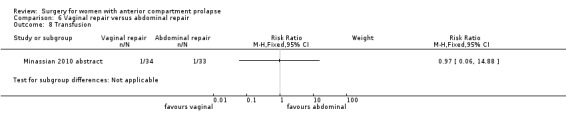

2.10.3 Transfusion

Blood transfusion was less likely after native tissue repair than after mesh repair (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.76; four RCTs; n = 486; I2 = 42%; Analysis 2.15).

2.15. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Native tissue versus polypropylene mesh, Outcome 15 Transfusion.

We have summarised study findings in Table 2.

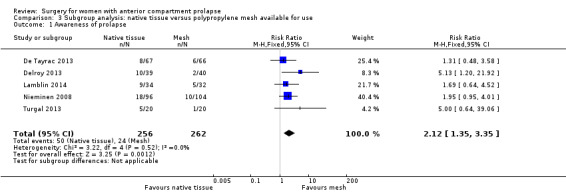

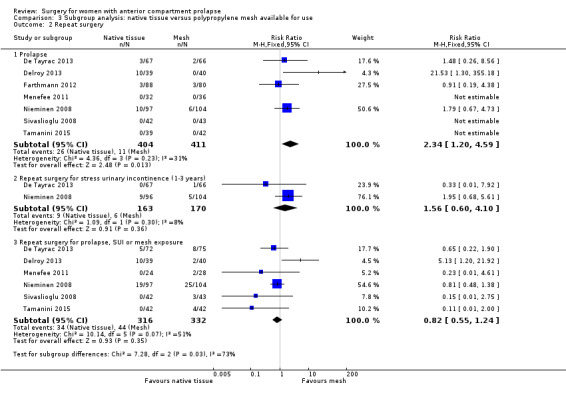

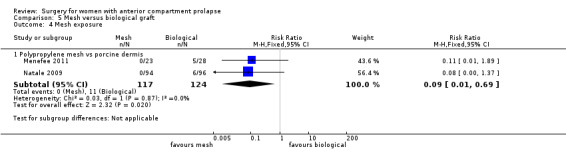

Subgroup analysis by market availability

We conducted a post hoc subgroup analysis for our primary outcomes that was restricted to studies of meshes currently on the market. This did not change our main findings with respect to awareness of prolapse (RR 2.12, 95% CI 1.35 to 3.35; nine RCTs; n = 518; I2 = 0%; Analysis 3.1), repeat surgery for prolapse (RR 2.34, 95% CI 1.20 to 4.59; 12 RCTs; n = 815; I2 = 31%; Analysis 3.2.1) or prolapse on examination (RR 2.35, 95% CI 1.83 to 3.01; 16 RCTs; n = 970; I2 = 31%; Analysis 3.3). However, rates of repeat surgery for prolapse, stress urinary incontinence or mesh exposure were no longer significantly different between groups (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.24; 12 RCTs; n = 648; I2 = 51%; Analysis 3.2.3).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis: native tissue versus polypropylene mesh available for use, Outcome 1 Awareness of prolapse.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis: native tissue versus polypropylene mesh available for use, Outcome 2 Repeat surgery.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis: native tissue versus polypropylene mesh available for use, Outcome 3 Recurrent anterior compartment prolapse.

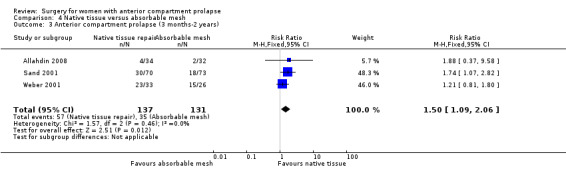

3 Native tissue compared with absorbable mesh

Three trials (Allahdin 2008; Sand 2001; Weber 2001) evaluated the effects of using absorbable polyglactin (Vicryl) mesh inlay to augment prolapse repairs.

Primary outcomes

3.1 Awareness of prolapse (two years)

Studies provided no evidence of a difference in awareness of prolapse at the two‐year review between native tissue repair and absorbable mesh (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.31; one RCT; n = 54; very low‐quality evidence). We downgraded evidence for attrition bias, imprecision and publication bias. Evidence suggests that if awareness of prolapse after absorbable mesh repair occurred in 76% of women, then 53.2% to 99.6% would develop awareness of prolapse after native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy). See Table 3.

3.2 Repeat surgery (two years)

3.2.1 Repeat surgery for prolapse

Studies provided no evidence of a difference in the need for repeat surgery for prolapse at the two‐year review between native tissue repair and absorbable mesh (RR 2.13, 95% CI 0.42 to 10.82; one RCT; n = 66; very low‐quality evidence). We downgraded evidence for attrition bias, imprecision and publication bias. The evidence suggests that if repeat surgery for prolapse were required after absorbable mesh repair in 5.9% of women, then 2.5% to 63.6% would require repeat surgery after native tissue repair (anterior colporrhaphy). See Table 3.

3.2.2 Repeat surgery for stress urinary incontinence

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

3.2.3 Repeat surgery for prolapse, stress urinary incontinence or mesh exposure (composite outcome)

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

3.3 Recurrent anterior prolapse (one to three years)

Recurrent anterior wall prolapse was more likely after native tissue repair than after absorbable mesh repair (RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.09 to 2.06; three RCTs; n = 268; I2 = 0%; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 4.3). We downgraded evidence for attrition bias. The evidence suggests that if the rate of anterior wall prolapse after absorbable mesh repair were 26.7%, then 29.1% to 55% would have recurrent anterior wall prolapse after native tissue repair. See Table 3.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Native tissue versus absorbable mesh, Outcome 3 Anterior compartment prolapse (3 months‐2 years).

Secondary outcomes

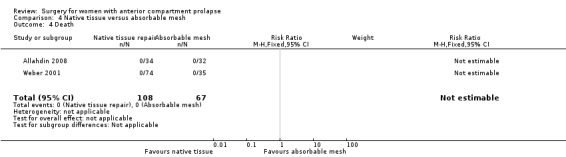

3.4. Adverse events

3.4.1 Death (related to surgery)

Two trials (Allahdin 2008; Weber 2001) reported no events of death in native tissue or absorbable mesh groups (Analysis 4.4).

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Native tissue versus absorbable mesh, Outcome 4 Death.

3.4.2 Mesh exposure

Two trials (Sand 2001; Weber 2001) reported one vaginal polyglactin mesh erosion (1/99; 1%; Table 4), and in Allahdin 2008, two women needed partial removal of mesh (2/32; 6.1%) for undisclosed reasons.

3.4.3 Injury to bladder (cystotomy)

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

3.4.4 Injury to bowel (enterotomy)

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

3.4.5 Repeat surgery for mesh exposure

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

3.5 Objective failure

3.5.1 Stage 2 or greater apical compartment prolapse

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

3.5.2 Stage 2 or greater posterior vaginal compartment prolapse

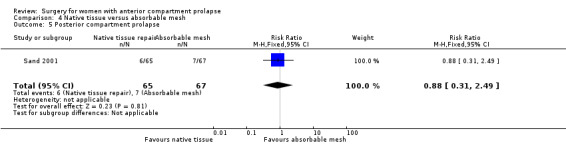

Studies provided no evidence of a difference between native tissue repair and absorbable mesh repair for posterior compartment prolapse (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.31 to 2.49; one RCT; n = 132).

3.5.3 Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ) system scores

Studies provided no data for this outcome.

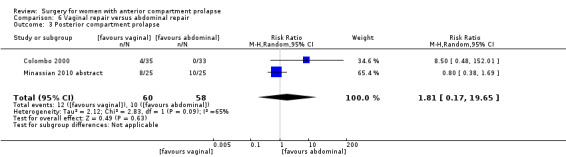

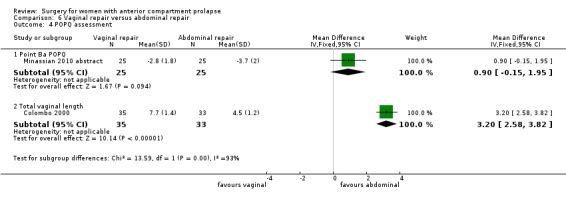

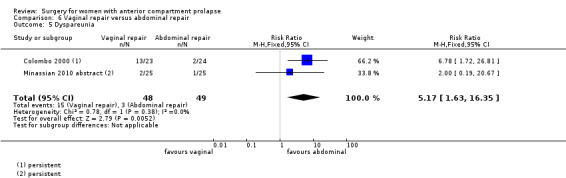

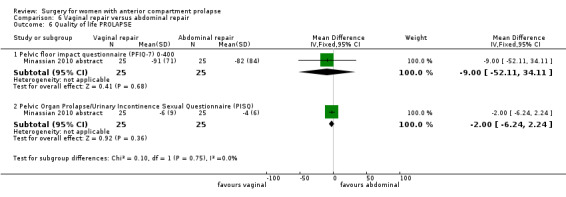

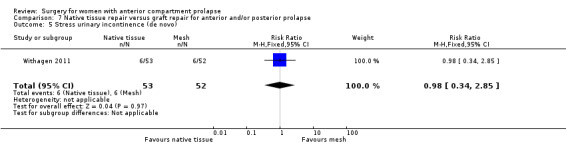

3.6 Bladder function

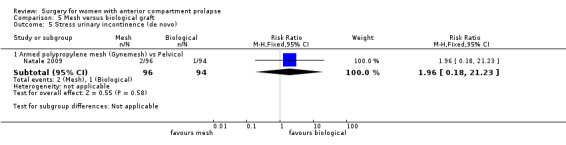

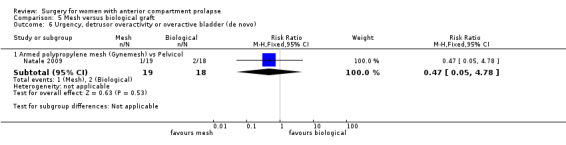

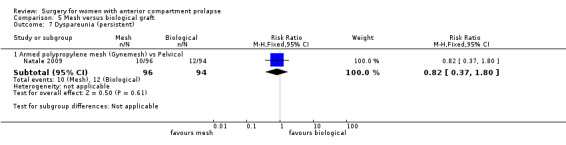

3.6.1 Stress urinary incontinence