Abstract

We herein report a 75-year-old woman with insulin-treated diabetes and metastatic anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer who received ceritinib, a second-generation ALK inhibitor, and achieved dramatic tumor reduction. However, her fasting blood glucose increased, particularly markedly in the first two weeks after ceritinib administration, and did not normalize even increasing the total insulin dose. After discontinuing ceritinib, her glucose levels rapidly reduced. Ceritinib can aggravate hyperglycemia in patients with diabetes who lack compensatory insulin secretion, due to its inhibitory effects on the insulin receptor. Careful monitoring for ceritinib-induced hyperglycemia should be performed, especially in the first two weeks after ceritinib administration.

Keywords: insulin resistance, ceritinib, hyperglycemia

Introduction

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearrangements that result from fusion with echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4 define a distinct molecular subtype of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (1). Approximately 2-6% of patients with NSCLC exhibit ALK-positive NSCLC, with higher rates observed in a clinically enriched (younger, never-smokers) population of patients with adenocarcinoma (2). ALK-positive NSCLC depends on ALK for its growth and survival and shows marked sensitivity to selective ALK inhibitors (3). Therefore, selective ALK inhibitors have transformed the therapeutic scenario of advanced ALK-positive NSCLC (4).

In this context, ceritinib, a second-generation ALK inhibitor, was found to induce increased glucose levels in 49% of patients in a first-in-human clinical trial (5) and hyperglycemia in 2.9% patients in a phase 2 clinical trial (6); however, the occurrence of hyperglycemia was not clarified in a phase 3 clinical trial (7). The hyperglycemic effect of ceritinib on patients with baseline blood glucose levels of >200 mg/dL is still unknown; this is because the hyperglycemic effect of ceritinib was an exclusion criterion in the protocol of a clinical trial (5). Therefore, details concerning the management of insulin-treated patients with diabetes who receive ceritinib would be useful for clinicians.

We herein report a 75-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes and metastatic ALK-rearranged NSCLC who developed marked hyperglycemia after receiving ceritinib.

Case Report

The patient was treated with an oral hypoglycemic agent after being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at 54 years of age and was diagnosed with NSCLC at 67 years of age. Insulin therapy was subsequently introduced for perioperative glycemic control. After the surgery, hyposecretion of endogenous insulin (urinary C-peptide: 17 μg/day) was observed, so insulin therapy was continued. Histopathology of NSCLC revealed adenocarcinoma with ALK rearrangements (Fig. 1, 2).

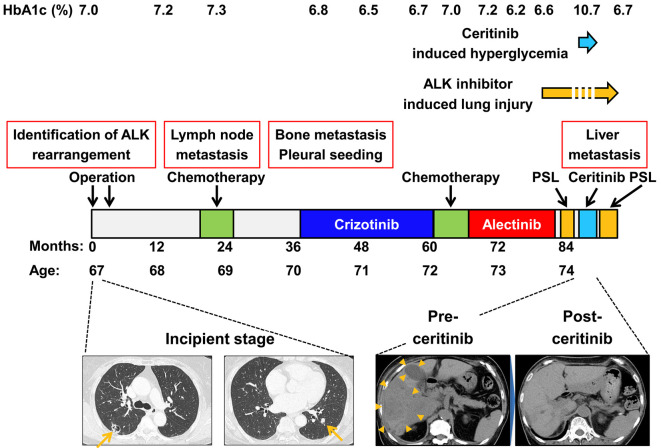

Figure 1.

Clinical management of a patient with metastatic anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The figure shows several lines of therapy received by the patient for metastatic ALK-rearranged NSCLC as well as the duration of each treatment. Computed tomography during the incipient stage revealed one nodular lesion each in both the left and right lobes (arrows). The metastatic liver lesions (arrowheads) were drastically reduced by ceritinib administration.

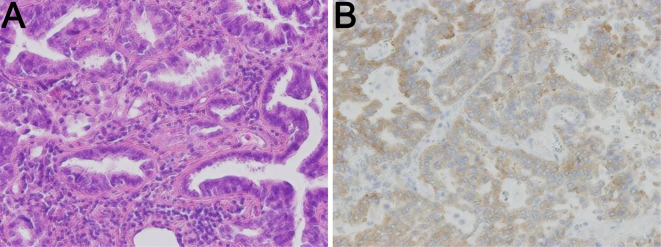

Figure 2.

(A) Hematoxylin and Eosin staining of the resected left lung tumor showed papillary adenocarcinoma. (B) Immunohistochemistry of ALK using the intercalated antibody-enhanced polymer (iAEP) method revealed the protein expression in the tumor cells.

The patient began to receive the first-generation ALK inhibitor crizotinib at 70 years of age and switched to the second-generation ALK inhibitor alectinib at 72 years of age. The glucose levels appeared to be well controlled by 18 U/day of insulin during crizotinib and alectinib treatments. At 74 years of age, however, alectinib caused drug-induced interstitial lung disease, after which the drug was stopped. Prednisolone administration improved the drug-induced interstitial lung disease. Increasing the total insulin dose from 18 to 29 U/day was sufficient to control the increasing glucose levels induced by prednisolone administration. During the secession of alectinib, numerous liver metastases developed. She then received ceritinib 750 mg/day for 2 weeks after the discontinuation of prednisolone. The metastatic liver lesions were dramatically reduced by ceritinib administration. However, pre-breakfast self-measured blood glucose increased from 100 (pretreatment) to >400 mg/dL (40 days after ceritinib administration) (Fig. 3). Anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 antibody was not detected (<5.0 U/mL). The C-peptide level in the presence of serum glucose (198 mg/dL) was 1.78 ng/mL, and the C-peptide index was 0.90. The C-peptide index before ceritinib administration had been 0.87 (C-peptide level, 1.10 ng/mL; glucose, 126 mg/dL). These data suggest that ceritinib induces impairment in insulin sensitivity rather than in insulin secretion. Furthermore, increasing the total insulin dose from 24 to 64 U/day was insufficient to control the increasing glucose levels. Unfortunately, drug-induced interstitial lung disease recurred, after which ceritinib was discontinued, and prednisolone treatment was restarted. Consequently, the glucose levels rapidly decreased, and the insulin dose was able to be reduced in parallel with ceritinib discontinuation. The glucose levels remained well controlled during prednisolone treatment. Based on these findings, ceritinib was deemed to have aggravated glycemic control in a diabetes patient undergoing insulin treatment, possibly causing insulin resistance.

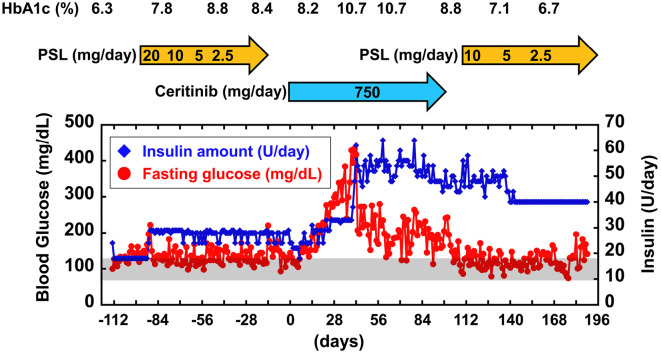

Figure 3.

The profile of insulin treatment and its management before and after ceritinib administration. The day that ceritinib administration was started is defined as day 0. The fasting glucose levels and insulin therapy during ceritinib treatment are indicated. The fasting glucose levels were evaluated based on pre-breakfast self-measured blood glucose levels. The fasting glucose levels drastically increased after two weeks of ceritinib administration. After ceritinib discontinuation, the patient’s glucose levels rapidly declined, and the insulin dose was able to be reduced, despite continued prednisolone (PSL) treatment.

Discussion

ALK is a member of the insulin receptor protein-tyrosine kinase superfamily (8). The ATP-binding sites of ALK are similar to those of the insulin receptor (INSR) (Fig. 4). The diversity in the gatekeeper and DFG motif-1 residue are key to determining the optimum selective kinase inhibitor (8). Interestingly, the gatekeepers of ALK and INSR are different (L1196 and M1103, respectively), whereas those of DFG motif-1 have high similarity.

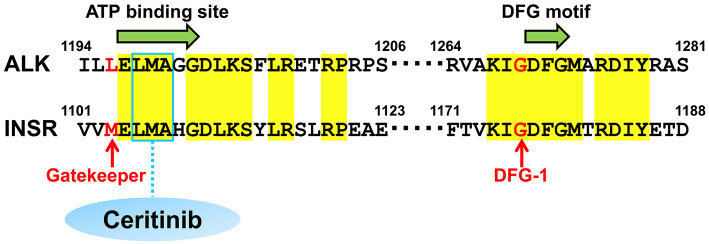

Figure 4.

The comparison of the amino acid residues in the ATP-binding and DFG motif-1 sites between anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and the insulin receptor (INSR). The similarities in the amino acid sequences around the ATP-binding site and DFG motif-1 between ALK and INSR are shown. Matched amino acid residues are highlighted in yellow. The gatekeeper and DFG motif-1 of ALK are L1196 and G1269 (indicated with red), respectively. Ceritinib binds to 1198LMA1200, known as the triad hinge of ALK as well as a key site for ATP binding (indicated by a blue box). The DFG motif-1 and LMA triad hinge are highly conserved between ALK and the INSR, aside from the difference in the gatekeeper (L1196 for ALK and M1103 for INSR).

In the present clinical course, crizotinib and alectinib had no effect on the patient's glucose tolerance. In contrast, ceritinib dramatically induced hyperglycemia. According to the prescribing information of ceritinib, ceritinib blocked INSR with greater potency than crizotinib (IC50: 7 vs. 290 nM) (Table). In addition, the prescribing information of alectinib indicated that the affinity of alectinib to INSR was low (IC50: 550 nM) (Table). Based on these observations, ceritinib was found to induce insulin resistance owing to its inhibitory effect on INSR. In general, prednisolone treatment also reduces the glucose tolerance. In the present case, the glucose levels were increased during ceritinib administration compared to prednisolone treatment. Taken together, these findings suggest that ceritinib, which has stronger inhibitory effects of INSR tyrosine kinase than crizotinib and alectinib, can induce strong impaired glucose tolerance, especially in patients with diabetes who lack compensatory insulin secretion.

Table.

Comparison of IC50 Values between ALK and INSR.

| IC50 (nM) | Ceritinib | Crizotinib | Alectinib |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALK | 0.2 | 3.0 | 1.9 |

| INSR | 7.0 | 290.0 | 550.0 |

| INSR IC50/ALK IC50 | 46.7 | 96.7 | 289.5 |

ALK: anaplastic lymphoma kinase, INSR: insulin receptor

Data of ceritinib and crizotinib was referred to the prescribing information of ceritinib. Data of alectinib was referred to the prescribing information of alectinib.

In addition, in the present case, the fasting glucose levels drastically increased after two weeks of ceritinib administration. The prescribing information indicates that a steady state is achieved after administration of ceritinib with 750 mg once-daily dosing for 15 days. Thus, monitoring for ceritinib-induced hyperglycemia should be performed, especially in the first two weeks after ceritinib administration.

In conclusion, ceritinib, a second-generation ALK inhibitor, can induce insulin resistance due to its inhibitory effects on the INSR compared with other ALK inhibitors, such as crizotinib and alectinib. Ceritinib can aggravate hyperglycemia, especially in patients with diabetes who lack compensatory insulin secretion. Therefore, monitoring for ceritinib-induced hyperglycemia should be performed, especially in the first two weeks after ceritinib administration.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

Financial Support

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grants 17K16160), MSD Life Science Foundation and Yamaguchi Endocrine Research Foundation.

References

- 1. Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature 448: 561-566, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mok TSK, Crino L, Felip E, et al. The accelerated path of ceritinib: translating pre-clinical development into clinical efficacy. Cancer Treat Rev 55: 181-189, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shaw AT, Kim DW, Mehra R, et al. Ceritinib in ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 370: 1189-1197, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gainor JF, Dardaei L, Yoda S, et al. Molecular mechanisms of resistance to first- and second-generation ALK inhibitors in ALK-rearranged lung cancer. Cancer Discov 6: 1118-1133, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khozin S, Blumenthal GM, Zhang L, et al. FDA approval: ceritinib for the treatment of metastatic anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 21: 2436-2439, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crino L, Ahn MJ, De Marinis F, et al. Multicenter phase II study of whole-body and intracranial activity with ceritinib in patients with ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy and crizotinib: results from ASCEND-2. J Clin Oncol 34: 2866-2873, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Soria J-C, Tan DSW, Chiari R, et al. First-line ceritinib versus platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer (ASCEND-4): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. The Lancet 389: 917-929, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Roskoski R., Jr Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitors in the treatment of ALK-driven lung cancers. Pharmacol Res 117: 343-356, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]