Abstract

Background

Electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training devices are used in rehabilitation, and may help to improve arm function after stroke.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training for improving activities of daily living, arm function, and arm muscle strength in people after stroke. We also assessed the acceptability and safety of the therapy.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group's Trials Register (last searched February 2015), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (the Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 3), MEDLINE (1950 to March 2015), EMBASE (1980 to March 2015), CINAHL (1982 to March 2015), AMED (1985 to March 2015), SPORTDiscus (1949 to March 2015), PEDro (searched April 2015), Compendex (1972 to March 2015), and Inspec (1969 to March 2015). We also handsearched relevant conference proceedings, searched trials and research registers, checked reference lists, and contacted trialists, experts, and researchers in our field, as well as manufacturers of commercial devices.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training for recovery of arm function with other rehabilitation or placebo interventions, or no treatment, for people after stroke.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected trials for inclusion, assessed trial quality and risk of bias, and extracted data. We contacted trialists for additional information. We analysed the results as standardised mean differences (SMDs) for continuous variables and risk differences (RDs) for dichotomous variables.

Main results

We included 34 trials (involving 1160 participants) in this update of our review. Electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training improved activities of daily living scores (SMD 0.37, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.11 to 0.64, P = 0.005, I² = 62%), arm function (SMD 0.35, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.51, P < 0.0001, I² = 36%), and arm muscle strength (SMD 0.36, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.70, P = 0.04, I² = 72%), but the quality of the evidence was low to very low. Electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training did not increase the risk of participant drop‐out (RD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.03, P = 0.84, I² = 0%) with moderate‐quality evidence, and adverse events were rare.

Authors' conclusions

People who receive electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm and hand training after stroke might improve their activities of daily living, arm and hand function, and arm and hand muscle strength. However, the results must be interpreted with caution because the quality of the evidence was low to very low, and there were variations between the trials in the intensity, duration, and amount of training; type of treatment; and participant characteristics.

Keywords: Adult; Aged; Aged, 80 and over; Humans; Middle Aged; Young Adult; Activities of Daily Living; Artificial Limbs; Recovery of Function; Robotics; Stroke Rehabilitation; Upper Extremity; Exercise Therapy; Exercise Therapy/instrumentation; Exercise Therapy/methods; Muscle Strength; Muscle Strength/physiology; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Stroke; Stroke/physiopathology

Electromechanical‐assisted training for improving arm function and disability after stroke

Review question

To assess the effects of electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm and hand training for improving arm function in people who have had a stroke.

Background

More than two‐thirds of people who have had a stroke have difficulties with reduced arm function, which can restrict a person's ability to perform everyday activities, reduce productivity, limit social activities, and lead to economic burden. Electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training uses specialised machines to assist rehabilitation in supporting shoulder, elbow, or hand movements. However, the role of electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training for improving arm function after stroke is unclear.

Study characteristics

We identified 34 trials (involving 1160 participants) up to March 2015 and included them in our review. Nineteen different electromechanical devices were described in the trials, which compared electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training with a variety of other interventions. Participants were between 21 to 80 years of age, the duration of the trials ranged from two to 12 weeks, the size of the trials was between eight and 127 participants, and the primary outcome differed between the included trials. Most of the trials were done in rehabilitation facilities in the USA.

Key results

Electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm and hand training improved activities of daily living in people after stroke and function and muscle strength of the affected arm. As adverse events such as injuries and pain were seldom described, these devices can be applied as a rehabilitation tool, but we still do not know when or how often they should be used.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence was low to very low.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Electromechanical and robotic‐assisted training versus all other interventions for improving activities of daily living, arm function, and arm muscle strength after stroke

| Electromechanical and robotic‐assisted training versus all other interventions for improving activities of daily living, arm function, and arm muscle strength after stroke | |||||

| Patient or population: people after stroke Settings: rehabilitation facilities Intervention: electromechanical and robotic‐assisted training versus all other interventions | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Control | Electromechanical and robotic‐assisted training versus all other interventions | ||||

| Activities of daily living at the end of intervention phase ‐ all studies Measures of activities. Scale from: 0 to inf | The mean activities of daily living at the end of intervention phase ‐ all studies in the control groups was NA | The mean activities of daily living at the end of intervention phase ‐ all studies in the intervention groups was 0.37 SDs higher (0.11 to 0.64 higher) | 717 (18 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | SMD 0.37 (0.11 to 0.64) |

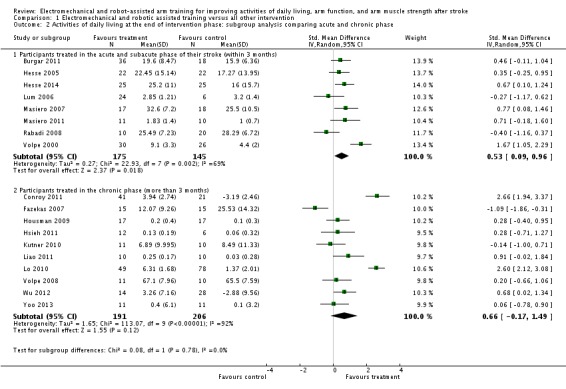

| Activities of daily living at the end of intervention phase: subgroup analysis comparing acute and chronic phase ‐ particpants treated in the acute and subacute phase of their stroke (within 3 months) Measures of activities. Scale from: 0 to inf | The mean activities of daily living at the end of intervention phase: subgroup analysis comparing acute and chronic phase ‐ participants treated in the acute and subacute phase of their stroke (within 3 months) in the control groups was NA | The mean activities of daily living at the end of intervention phase: subgroup analysis comparing acute and chronic phase ‐ participants treated in the acute and subacute phase of their stroke (within 3 month) in the intervention groups was 0.53 SDs higher (0.09 to 0.96 higher) | 320 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | SMD 0.53 (0.09 to 0.96) |

| Activities of daily living at the end of intervention phase: subgroup analysis comparing acute and chronic phase ‐ participants treated in the chronic phase (more than 3 months) Measures of activities. Scale from: 0 to inf | The mean activities of daily living at the end of intervention phase: subgroup analysis comparing acute and chronic phase ‐ participants treated in the chronic phase (more than 3 months) in the control groups was NA | The mean activities of daily living at the end of intervention phase: subgroup analysis comparing acute and chronic phase ‐ participants treated in the chronic phase (more than 3 months) in the intervention groups was 0.66 SDs higher (‐0.17 lower to 1.49 higher) | 397 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3 | SMD 0.66 (‐0.08 to 1.41) |

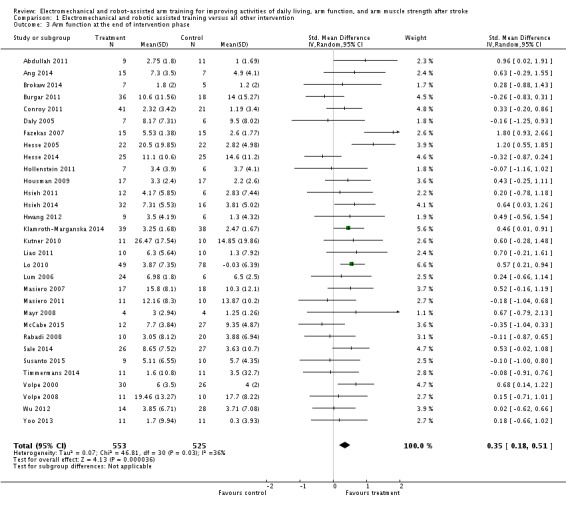

| Arm function at the end of intervention phase Measures of arm function. Scale from: 0 to inf | The mean arm function at the end of intervention phase in the control groups was NA | The mean arm function at the end of intervention phase in the intervention groups was 0.35 SDs higher (0.18 to 0.51 higher) | 1078 (31 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | SMD 0.35 (0.18 to 0.51) |

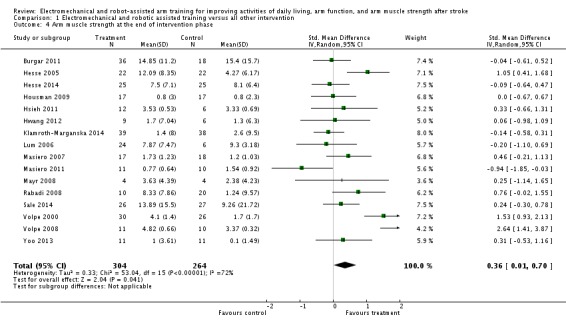

| Arm muscle strength at the end of intervention phase Measures of arm muscle strength. Scale from: 0 to inf | The mean arm muscle strength at the end of intervention phase in the control groups was NA | The mean arm muscle strength at the end of intervention phase in the intervention groups was 0.36 SDs higher (0.01 to 0.7 higher) | 568 (16 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | SMD 0.36 (0.01 to 0.7) |

| Acceptability: dropouts during intervention period Rate of dropouts and adverse events | Study population | 1160 (34 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | Risks were calculated from pooled risk differences | |

| 42 per 1000 | 45 per 1000 (22 to 72) | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; NA: Not applicable; RR: Risk ratio; SD: Standard deviation; SMD: Standardised mean difference | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1 Downgraded due to several ratings with 'high risk of bias'. 2 Downgraded due to considerable differences in effect sizes and unexplained heterogeneity. 3 Upper or lower confidence limit crosses an effect size of 0.5 in either direction.

Background

A stroke is a sudden, non‐convulsive loss of neurological function due to an ischaemic or haemorrhagic intracranial vascular event (WHO 2006). In general, strokes are classified by anatomic location in the brain, vascular distribution, aetiology, age of the affected individual, and haemorrhagic versus non‐haemorrhagic nature (Adams 1993). The prevalence of stroke depends on age and gender, and is estimated to be 1% of the population (Feigin 2009; Vos 2015). Stroke, taken together with ischaemic heart disease, is one of the largest sources of disease burden; in low‐ and middle‐income countries of Europe and Central Asia, these conditions account for more than a quarter of the total disease burden (Vos 2015).

Stroke is a major cause of chronic impaired arm function and may affect many activities of daily living. At hospital admission after stroke, more than two‐thirds of people have arm paresis, resulting in reduced upper extremity function (Jørgensen 1999; Nakayama 1994), and six months after stroke the affected arm of approximately half of all people remains without function (Kwakkel 2003). Therefore, to reduce this burden, many people receive multidisciplinary rehabilitation soon after stroke. However, despite intensive rehabilitation efforts, only approximately 5% to 20% of people reach complete functional recovery (Nakayama 1994); in other words, four out of five people leave rehabilitation with restricted arm function. Thus, there still exists an urgent need for new inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation and training strategies that match the specific needs of stroke survivors and their relatives (Barker 2005).

In recent years, new electromechanical‐assisted training strategies to improve arm function and activities of daily living have been developed for people after stroke. Examples of electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training devices found in this review are:

Mirror Image Motion Enabler, MIME (Burgar 2000);

InMotion robot (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, MIT‐Manus) (Krebs 1998);

Assisted Rehabilitation and Measurement (ARM) Guide (Reinkensmeyer 2000b);

Robotic Rehabilitation System for upper limb motion therapy for the disabled, REHAROB (Fazekas 2007);

Neuro‐Rehabilitation‐Robot, NeReBot (Fazekas 2007);

Bi‐Manu‐Track (Hesse 2003);

Robot‐mediated therapy system, GENTLE/s (Coote 2003);

Arm robot, ARMin (Riener 2005); and

Amadeo (Hwang 2012).

Most of these devices provide passive movement of the person's arm. Other devices assist arm movements or provide resistance during training. Some devices may assist active movements of an isolated joint, like in continuous passive motion (Hesse 2003), while other devices are able to move multiple segments to perform reaching‐like movements (Burgar 2000). The progression of therapy with electromechanical devices is possible by, for example, varying the force, decreasing assistance, increasing resistance, and expanding the movement amplitude. Moreover, some devices, such as the Bi‐Manu‐Track and the MIME, may be used to provide bimanual exercise: the device simultaneously moves (mirrors) the affected limb passively, steered by the non‐paretic limb. Broadly considered, most robotic systems incorporate more than one modality into a single device.

Early studies and previous reviews suggested that an advantage of electromechanical and robotic devices, when compared with conventional therapies, may be an increase in repetitions during arm training due to an increase of motivation to train and also the opportunity for independent exercise (Kwakkel 2008; Prange 2006). Therefore, electromechanical‐assistive training devices allow a therapy paradigm that is intensive, frequent and repetitive, and accords to principles of motor learning.

However, contrary to the remarkable number of publications about electromechanical technologies, scientific evidence for the benefits of these technologies, which could justify costs and effort, is still lacking. We summarised the evidence in our first Cochrane review about this topic in 2008 and in our last update in 2012 (Mehrholz 2008; Mehrholz 2012), but many new studies have emerged in recent years. Therefore there is a need for an updated and systematic evaluation of the available literature to assess the effectiveness and acceptability of these electromechanical‐assisted training devices.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training for improving activities of daily living, arm function, and arm muscle strength in people after stroke. We also assessed the acceptability and safety of the therapy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and randomised controlled cross‐over trials (we only analysed the first study period as a parallel‐group trial).

Types of participants

We included studies with participants of either gender over 18 years of age after stroke (using the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of stroke, or a clinical definition of stroke when the WHO definition was not specifically stated) (WHO 2006), regardless of the duration of illness or level of initial impairment. If we found RCTs with mixed populations (such as traumatic brain injury and stroke), we included only those RCTs with more than 50% of participants with stroke in our analysis.

Although we initially included all studies regardless of the duration of illness in our analysis, we later compared participants in the acute and subacute phase of their stroke (within three months) with participants in the chronic phase (more than three months) in a subgroup analysis.

Types of interventions

We compared electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training for recovery of arm function (such as robot‐aided technologies or any other newly developed electromechanical device) with any other intervention for:

improving activities of daily living (main analysis); and

improving impairments (secondary analysis).

An example of an eligible robot‐assisted intervention is the Mirror Image Motion Enabler, MIME (Burgar 2000). An example of an electromechanical‐assisted intervention is the Bi‐Manu‐Track (Hesse 2003). Other interventions could include other devices, other rehabilitation or placebo interventions, or no treatment.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was activities of daily living. We preferred the Barthel Index, Wade 1987, and the Functional Independence Measure, Hamilton 1994, (scales were regarded as continuous scaled, higher scores indicate a good outcome) as primary outcome measures, if they were available. However, we accepted other scales that measured activities of daily living.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were impairments, such as motor function and muscle strength. We measured arm and hand motor function with the Fugl‐Meyer score (regarded as continuous scaled, higher scores indicate a good outcome; Platz 2005) and measured arm and hand muscle strength with the Motricity Index Score (scales were regarded as continuous scaled, higher scores indicate a good outcome; Collin 1990; Demeurisse 1980). However, if these scales were not available we accepted other scales that measured arm and hand function and arm and hand muscle strength (in the following we will use the term 'arm function' instead of 'arm and hand function' and also 'arm muscle strength' instead of 'arm and hand muscle strength').

To measure the acceptance of electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training we used withdrawal or dropouts from the study due to any reason (including deaths) during the study period. We investigated the safety of electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training with the incidence of adverse outcomes, such as cardiovascular events, injuries and pain, and any other reported adverse events.

Depending on the aforementioned categories and the availability of variables used in the included trials, all review authors discussed and reached consensus on which outcome measures should be included in the analysis.

Search methods for identification of studies

See the 'Specialized register' section in the Cochrane Stroke Group module. We did not restrict our searches by language, publication status, or date, and we arranged for the translation of articles where necessary.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (last searched in February 2015) and the following bibliographic databases:

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (the Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 3) (Appendix 1);

MEDLINE (Ovid) (1950 to March 2015) (Appendix 2);

EMBASE (Ovid) (1980 to March 2015) (Appendix 3);

CINAHL (Ebsco) (1982 to March 2015) (Appendix 4);

AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine) (Ovid) (1985 to March 2015) (Appendix 5);

SPORTDiscus (Ebsco) (1949 to March 2015) (Appendix 6);

Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro, http://www.pedro.org.au/) (searched April 2015);

Compendex (1972 to March 2015) and Inspec (1969 to March 2015) (Engineering Village) (Appendix 7).

We developed the search strategy for MEDLINE with the help of the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator and modified it for the other databases.

Searching other resources

In an effort to identify further published, unpublished, and ongoing trials not available in the major databases, we:

-

handsearched the following relevant conference proceedings:

World Congress for NeuroRehabilitation (WCNR, 1998, 2002, 2006, 2010, and 2014);

International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine World Congress (ISPRM 2001, 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, and 2011);

World Confederation for Physical Therapy (2003, 2007, 2011, and 2015);

International Congress on Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair (2015);

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurotraumatologie und Klinische Neurorehabilitation (2001 to 2015);

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie (2000 to 2014);

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurorehabilitation (1999 to 2014);

screened reference lists of all relevant articles;

-

identified and searched the following ongoing trials and research registers:

ISRCTN Registry (http://www.isrctn.com/) (searched June 2015);

ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov/) (searched June 2015);

Stroke Trials Registry (www.strokecenter.org/trials) (searched June 2015);

contacted trialists, experts, and researchers in our field of study; and

-

contacted the following manufacturers of commercial devices:

Hocoma (last contact March 2015); and

Reha‐Stim (last contact May 2015).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (JM and BE) independently read the titles and abstracts (if available) of identified publications and eliminated obviously irrelevant studies. We obtained the full text for the remaining studies, and the same two review authors independently examined potentially relevant studies using our predetermined criteria for including studies. Based on types of studies, participants, aims of interventions, and outcome measures, the review authors independently ranked these studies as relevant, irrelevant, or possibly relevant. We excluded all trials ranked initially as irrelevant, but included all other trials at that stage for further assessment. We excluded all trials of specific treatment components (such as electrical stimulation) as standalone treatment, and continuous passive motion treatment and continuous passive stretching. All review authors resolved disagreements through discussion. If further information was needed to reach consensus, we contacted the study authors.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (JM and MP) independently extracted trial and outcome data from the selected trials. We used checklists to independently record details of the studies. If any review author was involved in any of the selected studies, another member of our review team not involved in the study was asked to handle the study information.

We established the characteristics of unpublished trials through correspondence with the trial co‐ordinator or principal investigator. We used checklists to independently record details of the:

methods of generating randomisation schedule;

method of concealment of allocation;

blinding of assessors;

use of an intention‐to‐treat analysis (all participants initially randomised were included in the analyses as allocated to groups);

adverse events and dropouts for all reasons;

important imbalance in prognostic factors;

participants (country, number of participants, age, gender, type of stroke, time from stroke onset to entry to the study, inclusion and exclusion criteria);

comparison (details of the intervention in treatment and control groups, details of co‐intervention(s) in both groups, duration of treatment); and

outcomes and time points of measures (number of participants in each group and outcome, regardless of compliance).

We checked all of the extracted data for agreement between review authors, with another review author (JK or BE) arbitrating any disagreements. We contacted study authors to request more information, clarification, or missing data if necessary.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

All review authors independently assessed the methodological quality of the included trials using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

We checked all methodological quality assessments for agreement between review authors, resolving any disagreements by discussion. Two review authors (MP and JM) were coauthors of one included trial (Hesse 2005); two other review authors (BE and JK) conducted the quality assessment for this trial.

Measures of treatment effect

The primary outcome variables of interest were treated as continuous data and entered as mean and standard deviations (SDs). We calculated a pooled estimate of the mean differences (MDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). If studies used different scales for an outcome variable, or if we obtained only full data of all included studies regarding changes from baseline to study end, we entered data as mean changes and SDs of changes and used the standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI instead of MDs. For all binary outcomes (such as the secondary outcome 'dropouts from all causes'), we calculated risk ratios (RRs) with 95% CIs. If studies reported no events, we calculated risk differences (RDs) with 95% CIs, instead of RRs.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the I² statistic to assess heterogeneity. We used a random‐effects model, regardless of the level of heterogeneity.

Data synthesis

We pooled the results of all eligible studies to present an overall estimate of the effect of electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training (meta‐analysis). For all statistical analyses we used the latest version of the Cochrane Review Manager software, RevMan 5.3 (RevMan 2014). We calculated the overall effects using a random‐effects model, regardless of the level of heterogeneity. To test the robustness of the results, we did a sensitivity analysis by leaving out studies that we assessed to be of lower or ambiguous methodological quality (with respect to randomisation procedure, allocation concealment, and blinding of assessors). Clinical diversity and heterogeneity did not contribute to the decision about when to pool trials, but we described clinical diversity, variability in participants, interventions, and outcomes studied in Table 5.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics in studies

| Study ID | Age, mean (SD) EXP | Age, mean (SD) CON | Time poststroke EXP | Time poststroke CON | Gender EXP | Gender CON | Side‐paresis EXP | Side‐paresis CON | Stroke severity | Aetiology (ischaemic/haemorrhagic) |

| Abdullah 2011 | 76 (6) years | 70 (16) years | 4 (2) weeks | 4 (2) weeks | 3 F, 5 M | 8 F, 3 M | 3 L, 5 R | 6 L, 4 R, 1 both | Stage 1‐3 CMSA | Not stated |

| Amirabdollahian 2007 | 67 (7) years | 68 (9) years | 17 (12) months | 31 (22) months | 9 F, 7 M | 5 F, 10 M | 9 L, 7 R | 7 L, 8 R | Not stated | Not stated |

| Ang 2014 | 52 (7) years | 58 (19) years | 350 (131) days | 455 (110) days | 4 F, 10 M | 3 F, 4 M | Not stated | Not stated | Mean 27 points FMA upper extremity | 11/10 |

| Brokaw 2014 | 57 (12) years | 3 (2) years | 3 F, 9 M | 7 L, 5 R | Mean 22 points FMA upper extremity | Not stated | ||||

| Burgar 2011 | 60 (2) years* | 68 (3) years* | 17 (3) days* | 11 (1) days* | Not stated | Not stated | 18 L, 18 R | 5 L, 13 R | Mean 27 points FIM upper limb | Not stated |

| Conroy 2011 | 59 (13) years | 56 (6) years | 4 (5) years | 4 (6) years | 23 F, 18 M | 11 F, 10 M | Not stated | Not stated | Mean 72 points score on SIS, ADL | 51/6 |

| Daly 2005 | Not stated | Not stated | > 12 months | > 12 months | 0 F, 6 M | 3 F, 3 M | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | 11/1 |

| Fazekas 2007 | 57 years | 56 years | 23 months | 10 months | 8 F, 7 M | 5 F, 10 M | 7 L, 8 R | 6 L, 9 R | Mean 30 points FIM self‐care | Not stated: also included people after head trauma |

| Hesse 2005 | 65 (12) years | 64 (12) years | 5 (1) weeks | 5 (1) weeks | 12 F, 10 M | 12 F, 10 M | 14 L, 8 R | 11 L, 11 R | Mean 42 of 100 Barthel points | 40/4 |

| Hesse 2014 | 71 (16) years | 70 (17) years | 5 (2) weeks | 5 (1) weeks | 12 F, 13 M | 10 F, 15 M | 14 L, 11 R | 13 L, 12 R | Mean 27 of 100 Barthel points | 41/9 |

| Hollenstein 2011 | 71 (8) years | 75 (11) years | 33 (14) days | 29 (10) days | 4 F, 3 M | 5 F, 1 M | 4 L, 3 R | 3 L, 3 R | Not stated | Not stated |

| Housman 2009 | 54 (12) years | 56 (11) years | > 12 months | > 12 months | 3 F, 11 M | 7 F, 7 M | 10 L, 4 R | 10 L, 4 R | Not stated | 17/9; 2 unknown |

| Hsieh 2011 | 54 (8) years | 54 (8) years | 17 (7) months | 28 (20) months | 2 F, 8 M | 1 F, 5 M | 6 L, 6 R | 4 L, 2 R | Not stated | 15/3 |

| Hsieh 2014 | 53 (10) years | 54 (10) years | 22 (14) months | 28 (19) months | 10 F, 22 M | 4 F, 12 M | 19 L, 13 R | 7 L, 9 R | Mean 34 points FMA upper extremity | 27/21 |

| Hwang 2012 | 50 (4) years | 51 (3) years | 7 (6) months | 5 (6) months | 4 F, 5 M | 2 F, 4 M | Not stated | Mean 43 (16) SIS activities | Not stated | |

| Kahn 2006 | 56 (12) years | 56 (12) years | 76 (46) months | 103 (48) months | 6 F, 4 M | 2 F, 7 M | 5 L, 5 R | 6 L, 3 R | Not stated | Not stated |

| Klamroth‐Marganska 2014 | 55 (13) years | 58 (14) years | 52 (44) months | 40 (45) months | 17 F, 21 M | 10 F, 25 M | Not stated | Mean SIS total score 63 (11) | Not stated | |

| Kutner 2010 | 62 (13) years | 51 (11) years | 270 (111) days | 184 (127) days | 5 F, 5 M | 2 F, 5 M | Not stated | Not stated | SIS ADL mean 59 and 68 for EXP and CTL groups, respectively | 12/5 |

| Liao 2011 | 55 (11) years | 54 (8) years | 23 (13) months | 22 (17) months | 4 F, 6 M | 3 F, 7 M | 4 L, 6 R | 3 L, 7 R | Mean 116 points FIM self‐care | Not stated |

| Lo 2010 | 66 (11) years | 64 (11) years | 4 (4) months | 5 (4) months | 2 F, 47 M | 3 F, 75 M | Not stated | Not stated | Mean 49 points score on SIS | 108/19 |

| Lum 2002 | 63 (4) years* | 66 (2) years* | 30 (6) months* | 29 (6) months* | 1 F, 12 M | 6 F, 8 M | 4 L, 9 R | 4 L, 10 R | Mean 87 of 100 Barthel points | Not stated |

| Lum 2006# | 67 years | 60 years | 11 weeks | 11 weeks | 8 F, 16 M | 2 F, 4 M | 11 L, 13 R | 2 L, 4 R | Not stated | Not stated |

| Masiero 2007 | 63 (13) years | 67 (12) years | Not stated | Not stated | 7 F, 10 M | 7 F, 11 M | 4 L, 11 R | 5 L, 10 R | Not stated | Not stated |

| Masiero 2011 | 72 (7) years | 76 (5) years | 10 (5) days | 13 (5) days | 2 F, 9 M | 3 F, 7 M | 9 L, 2 R | 8 L, 2 R | Mean total FIM 30 points | 18/3 |

| Mayr 2008 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | 4 L | 4 L | Not stated | 6/2 |

| McCabe 2015 | 21‐49 years: n = 2; 50‐81 years: n = 10 | 21‐49 years: n = 5; 50‐81 years: n = 18 | 1‐3 years: n = 9; ≥4 years: n = 3 | 1‐3 years: n = 18; ≥4 years: n = 5 | 2 F, 10 M | 10 F, 13 M | Not stated | Not stated | 23 (6) FMA upper extremity points | Not stated |

| Rabadi 2008 | 80 (6) years | 69 (11) years | 10 (4) days | 14 (13) days | 5 F, 5 M | 6 F, 14 M | Not stated | Not stated | Mean FIM score 39 (11) | 3/0 |

| Sale 2014 | 68 (14) years | 68 (14) years | Not stated | Not stated | 11 F, 15 M | 11 F, 16 M | 16 L, 10 R | 13 L, 14 R | Mean CMSA 3 (1) | 53/0 |

| Susanto 2015 | 51 (9) years | 55 (11) years | 16 (6) months | 16 (5) months | 2 F, 7 M | 3 F, 7 M | 6 L, 3 R | 6 L, 4 R | Mean FMA 33 (9) | 8/11 |

| Timmermans 2014 | 62 (7) years | 57 (6) years | 3 (3) years | 4 (3) years | 3 F, 8 M | 3 F, 8 M | 7 L, 4 R | 8 L, 3 R | Mean FMA 52 | Not stated |

| Volpe 2000 | 62 (2) years* | 67 (2) years* | 23 (1) days* | 26 (1) days* | 14 F, 16 M | 12 F, 14 M | 17 L, 13 R | 14 L, 12 R | Not stated | 49/7 |

| Volpe 2008 | 62 (3) years* | 60 (3) years* | 35 (7) months* | 40 (11) months* | 3 F, 8 M | 3 F, 7 M | 5 L, 6 R | 5 L, 5 R | Mean 17 points NIHSS | 20/1 |

| Wu 2012 | 56 (11) years | 51 (6) years | 18 (11) months | 18 (10) months | 6 F, 22 M | 4 F, 22 M | 16 L, 12 R | 10 L, 4 R | Mean FMA 44 (10) points | Not stated |

| Yoo 2013 | 51 (11) years | 50 (9) years | 46 (42) months | 42 (33) months | 4 F, 7 M | 5 F, 6 M | 6 L, 5 R | 4 L, 7 R | Mean Barthel Index 76 (5) | 15/7 |

*SE instead of SD #EXP: all robot groups ADL: activities of daily living CMSA: Chedoke‐McMaster Stroke Assessment CON: control group EXP: experimental group F: female FIM: Functional Independence Measure FMA: Fugl‐Meyer AssessmentL: left M: male NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke ScaleR: right SD: standard deviation SE: standard error SIS: Stroke Impact Scale

If studies had three or more intervention groups, for example two treatment groups and one control group, and the results of these intervention groups did not differ significantly, we combined the results of all intervention groups in one (collapsed) group and compared this with the results of the control group.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted a formal subgroup analysis by splitting all participants into two subgroups: a subgroup of participants in the acute and subacute phase of their stroke (within three months) and a subgroup of participants treated in the chronic phase (more than three months after stroke). In this subgroup analysis, we did a formal comparison between the results of the primary outcome measure of participants treated in the acute and subacute phase of their stroke compared with the results of participants treated in the chronic phase (Deeks 2011).

We conducted another subgroup analysis by splitting all participants into two subgroups: a subgroup of participants who received mainly training for the distal arm and the hand (finger, hand, and radio‐ulnar joints) and a subgroup of participants who received training mainly of the proximal arm (shoulder and elbow joints) and a subgroup of participants treated in the chronic phase (more than three months after stroke). In this subgroup analysis, we did a formal comparison between the results of the subgroups for the primary outcome measure (activities of daily living) and the secondary outcome measure (arm function). To quantify heterogeneity we used the I² statistic implemented in RevMan 5.3 for all comparisons (RevMan 2014).

Sensitivity analysis

In accordance with the description in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interentions, we used the methodological features randomisation procedure, concealed allocation, and blinding of assessors to test the robustness of the main results in a sensitivity analysis (Higgins 2011).

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, Characteristics of ongoing studies, Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 2.

Details of study interventions

| Study ID | Duration of study | Frequency and intensity of treatment | Follow‐up | Device used |

| Abdullah 2011 | 8 to 11 weeks | 3 times a week (groups received the same time and frequency) | ‐ | Adapted 5 DOF industrial robot |

| Amirabdollahian 2007 | 3 weeks | 5 times a week (groups received the same time and frequency) | ‐ | GENTLE/s |

| Ang 2014 | 6 weeks | 3 times a week for 90 minutes (groups received the same time and frequency) | 6 weeks and 18 weeks | Haptic Knob and Haptic Knob with Brain‐Computer Interface |

| Brokaw 2014 | 3 months | 12 hours within a month (groups received the same time and frequency) | ‐ | ARMin III, HandSOME |

| Burgar 2011 | 3 weeks | 1 experimental group and the control group had 15 x 1‐hour therapy sessions over a 3‐week period (1 robot group received 30 1‐hour therapy sessions over a 3‐week period) | 6 months | MIME |

| Conroy 2011 | 6 weeks | 3 sessions per week for 1 hour (groups received the same time and frequency) | 3 months | InMotion 2.0 Shoulder/Arm Robot |

| Daly 2005 | 12 weeks | 5 hours a day, 5 days a week (groups received the same time and frequency) | 3 months | InMotion |

| Fazekas 2007 | 5 weeks | Control group received 30‐minute sessions on 20 consecutive workdays (Bobath, Kabat) Experimental group received same therapy as the control group, but also additional 30 minutes of robot therapy | ‐ | REHAROB |

| Hesse 2005 | 6 weeks | 30 minutes, 5 times a week (groups received the same time and frequency) | 3 months | Bi‐Manu‐Track |

| Hesse 2014 | 4 weeks | 30 minutes, 5 times a week (groups received the same time and frequency) | 3 months | Bi‐Manu‐Track, Reha‐Digit, Reha‐Slide, Reha‐Slide Duo |

| Hollenstein 2011 | 2 weeks | 5 times a week for 30 minutes (groups received the same time and frequency) | ‐ | Armeo |

| Housman 2009 | 8 to 9 weeks | 3 times a week for 1 hour (groups received the same time and frequency) | 6 months | T‐WREX |

| Hsieh 2011 | 4 weeks | Higher‐intensity robotic training group: 20 sessions for 90 to 105 minutes, 5 days per week Lower‐intensity robotic training group: same amount, but had only half of the repetitions by the device as in first group Conventional treatment group: same amount as in the other groups (groups received the same time and frequency) |

‐ | Bi‐Manu‐Track |

| Hsieh 2014 | 4 weeks | Participants in each group received 20 training sessions of 90 to 105 minutes/day, 5 days/week for 4 weeks. In addition to the intervention provided in the clinics, all participants were encouraged to use their affected upper limb during activities in their daily life situations (e.g. at home) RT + CIT group (received 2 weeks robot‐assisted arm therapy (Bi‐Manu‐Track 40 to 55 minutes plus 15 to 20 minutes conventional therapy without robot), afterwards 2 weeks constraint‐induced therapy 90 to 105 minutes therapy a day and 6 hours constraint daily) RT group (received robot‐assisted arm therapy (Bi‐Manu‐Track) as above) CT group (received a therapist‐mediated intervention using conventional occupational therapy techniques, including neurodevelopmental techniques, functional task practice, fine‐motor training, arm exercises or gross‐motor training, and muscle strengthening) |

‐ | Bi‐Manu‐Track |

| Hwang 2012 | 4 weeks | 4 weeks (20 sessions) of active robot‐assisted intervention versus 2 weeks (10 sessions) of early passive therapy followed by 2 weeks (10 sessions) of active robot‐assisted intervention (groups received the same time and frequency) | 4 weeks | Amadeo |

| Kahn 2006 | 8 weeks | 24 sessions for 45 minutes (groups received the same time and frequency) | ‐ | ARM Guide |

| Klamroth‐Marganska 2014 | 8 weeks | Robotic training or conventional therapy 3 times a week for at least 45 minutes (groups received the same time and frequency) | 26 weeks | ARMin |

| Kutner 2010 | 3 weeks | 1) 60 hours of repetitive‐task training over the course of 3 weeks 2) 30 hours of repetitive‐task training plus 30 hours of robotic‐assisted training with the Hand Mentor device over the course of 3 weeks (groups received the same time and frequency) |

2 months | Hand Mentor |

| Liao 2011 | 4 weeks | 5 days a week for 90 to 105 minutes per session (groups received the same time and frequency) | ‐ | Bi‐Manu‐Track |

| Lo 2010 | 12 weeks | Group A: a maximum of 36 sessions over a period of 12 weeks Group B: same time and frequency Group C: usual care at different time and frequency |

3, 6, 9 months | MIT‐Manus |

| Lum 2002 | 8 weeks | Control group received 55 minutes of physiotherapy for the arm and 5 minutes of robot training at each of the 24 sessions Experimental group received robot therapy for the same time and frequency | 8 months | MIME |

| Lum 2006 | 4 weeks | All groups received 15 1‐hour treatment sessions (all groups had same time and frequency) | 6 months | MIME |

| Masiero 2007 | 5 weeks | Experimental group received additional robotic training twice a day, 5 days a week Control group received similar exposure to the robot but with the unimpaired arm (both groups had same time and frequency) |

3 and 8 months | NeReBot |

| Masiero 2011 | 5 weeks | Experimental group received robotic training twice a day for 20 minutes, and 40 minutes conventional training, 5 days a week Control group received conventional functional rehabilitation for 80 minutes a day (groups received the same time and frequency) |

3 months | NeReBot |

| Mayr 2008 | 6 weeks | 5 times per week (both groups received the same time and frequency) | ‐ | ARMOR |

| McCabe 2015 | 5 weeks | 5 hours per day for 12 weeks (all groups received the same time and frequency) | ‐ | InMotion2 Shoulder/Elbow Robot |

| Rabadi 2008 | Not stated | Standard occupational and physical therapy for 3 hours per day + 12 additional sessions of 40 minutes of either occupational therapy, arm ergometry, or robotic‐assisted training for 5 days per week | ‐ | MIT‐Manus |

| Sale 2014 | 6 weeks | 30 sessions of robot‐assisted therapy (5 days a week for 6 weeks) versus 30 sessions (5 days a week for 6 weeks) of conventional rehabilitative treatment Experimental and control therapies were applied in addition to usual rehabilitation (groups received the same time and frequency) |

‐ | MIT‐Manus/InMotion2 |

| Susanto 2015 | 5 weeks | Hand exoskeleton robot‐assisted training for 20 1‐hour sessions versus control group (non‐assisted group) for 20 1‐hour sessions (groups received the same time and frequency) | 6 months | Self designed hand exoskeleton robot |

| Timmermans 2014 | 8 weeks | Robotic‐assisted training with the end‐effector robot HapticMaster versus arm‐hand training program during 8 weeks, 4 times/week, twice a day for 30 minutes (groups received the same time and frequency) | 6 month | HapticMaster |

| Volpe 2000 | 5 weeks | 1 hour per day, 5 days a week (for at least 25 sessions) (both groups received the same time and frequency) | ‐ | MIT‐Manus |

| Volpe 2008 | 6 weeks | 1 hour per session, 3 times a week (both groups received the same time and frequency) | 3 months | InMotion2 |

| Wu 2012 | 4 weeks | Therapist‐mediated bilateral arm training (TBAT group) versus robot‐assisted (Bi‐Manu‐Track) arm trainer (RBAT group) versus conventional therapy (involved weight bearing, stretching, strengthening of the paretic arms, co‐ordination, unilateral and bilateral fine‐motor tasks, balance, and compensatory practice on functional tasks; CT group). Each group received treatment for 90 to 105 minutes per session, 5 sessions on weekdays, for 4 weeks (groups received the same time and frequency) | ‐ | Bi‐Manu‐Track |

| Yoo 2013 | 6 weeks | 3‐dimensional robot‐assisted therapy (RAT) and conventional rehabilitation therapy (CRT) for a total of 90 minutes (RAT: 30 minutes, CRT: 60 minutes) a day with 10 minutes rest halfway through the session, received training 3 days a week for 6 weeks. The control group received only CRT for 60 minutes a day on the same days as the first group | ‐ | ReoGo |

DOF: Degrees of Freedom MIME: mirror image motion enabler

Results of the search

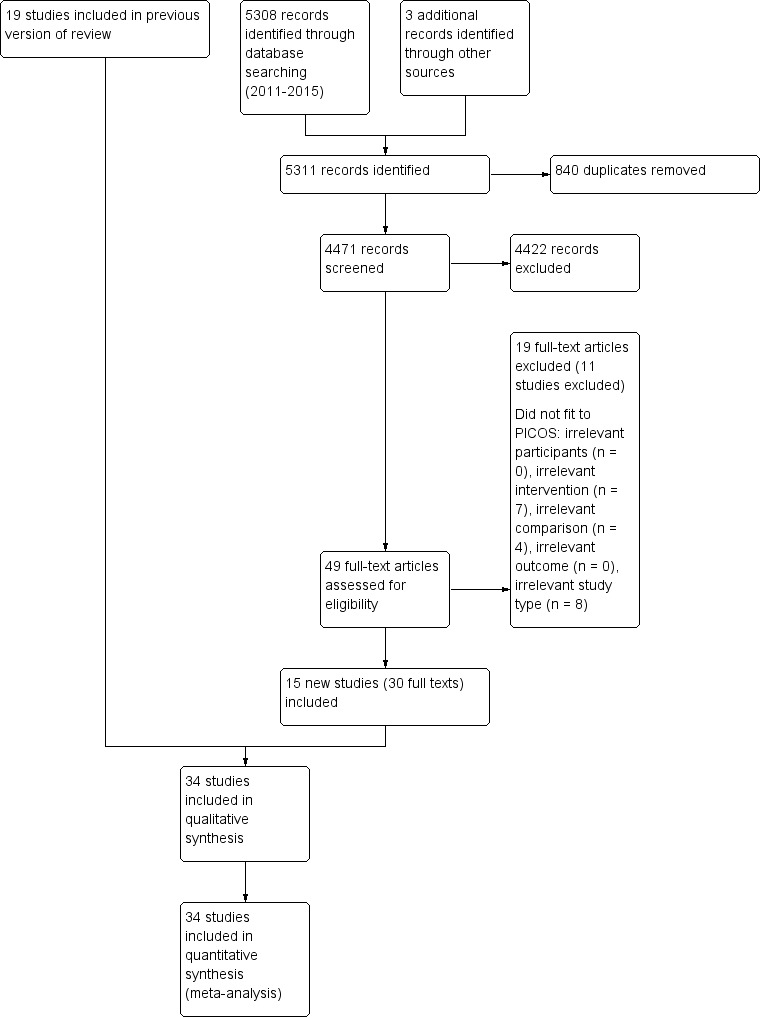

Our updated searches of the electronic bibliographic databases identified 5308 citations (Figure 1). One review author (BE) carried out additional searches of trials registers, commercial websites, conference proceedings, and reference lists, and from these and the search of the Cochrane Stroke Group's Trials Register, we identified three further studies for inclusion. Hence the number of records identified was 5311. After the elimination of duplicates, two review authors (BE and JM) assessed 4471 relevant abstracts and eliminated obviously irrelevant studies from the titles and abstracts alone. We obtained the full text of 49 possibly relevant papers. The same review authors (BE and JM) independently reviewed the full papers and selected 15 studies (30 full texts) that met our inclusion criteria. If necessary due to disagreements or uncertainties, we held consensus discussions involving additional review authors. We carefully considered and discussed a further 10 studies, but did not deem them eligible; we have detailed them in Characteristics of excluded studies.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. Please note that several studies have been published in multiple full‐text articles. Hence the number of assessed full‐text articles and the number of identified studies may differ.

We thus identified 15 new studies (30 full texts), and together with 19 studies included in the original review, we have included a total of 34 studies in this update. Five studies are still awaiting classification; we have described these studies in detail in Characteristics of studies awaiting classification. In addition, we identified 24 ongoing studies, which we have listed in Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Included studies

Thirty‐four trials, including a total of 1160 participants, met our inclusion criteria and have been included in the analysis (see Figure 1, Characteristics of included studies, Table 5, and Table 6).

Design

Two trials used a cross‐over design with random allocation to the order of treatment sequences (Amirabdollahian 2007; Hollenstein 2011). For Amirabdollahian 2007, we could not obtain outcome data from the trialists of this study, therefore we could not pool the data for this trial together with the data from other studies. In the study of Hollenstein 2011, we used the data of the first period before cross‐over. All other studies used a parallel‐group design with true randomisation‐to‐group allocation.

Sample sizes

The sample sizes in the trials ranged from eight participants, in Mayr 2008, to 127 participants, in Lo 2010 (sample size median = 30 interquartile range = 25). We have provided a more detailed description of trial characteristics in Characteristics of included studies and in Table 5 and Table 6.

Setting

Most of the trials were done in rehabilitation facilities in the USA. We have provided a more detailed description of trial characteristics in Characteristics of included studies.

Participants

The mean age of participants in the included studies ranged from 21 years, in McCabe 2015, to 80 years, in Rabadi 2008. We have provided a detailed description of participant characteristics in Table 5. There were significantly more males than females (66% males with 95% CI 63 to 69), and slightly more participants with left‐sided hemiparesis (53% left‐sided with 95% CI 49 to 57) included in the studies.

Twenty‐three studies provided information about baseline stroke severity (for example Functional Independence Measure, Barthel) or about the deficit of arm motor function (Fugl‐Meyer) (Table 5; Table 6).

For inclusion and exclusion criteria of every included study, see Characteristics of included studies.

Interventions

The duration of the studies (time frame where experimental interventions were applied) was heterogeneous, ranging from two weeks, in Hollenstein 2011, and three weeks, in Amirabdollahian 2007; Burgar 2011, to 12 weeks (Brokaw 2014; Daly 2005; Lo 2010). Most studies (eight out of 34) used a two‐, three‐, four‐, or six‐week study period (Table 6). The studies described and used 19 different electromechanical devices (see Table 6 for an overview); the devices used most often were the Bi‐Manu‐Track (Hesse 2005; Hesse 2014; Hsieh 2011; Hsieh 2014; Liao 2011; Wu 2012), the InMotion (Conroy 2011; Daly 2005; McCabe 2015; Volpe 2008), and the MIT‐Manus (Lo 2010; Rabadi 2008; Sale 2014; Volpe 2000).

Comparisons

The included trials compared electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training with a variety of other interventions. We only did a formal meta‐analysis of studies that measured the same treatment effect. Thus we combined electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training versus placebo (or no additional therapy) (two studies) with electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training combined with physiotherapy versus physiotherapy alone (32 studies), as both estimate the effect of electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training compared with a different treatment. However, we did not combine electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training versus physiotherapy (or no treatment) with electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training A versus electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training B (Lum 2002), as these all measure entirely different treatment effects.

One study had four groups: three treatment (robot) groups and one control group (Lum 2006). Since the results of these experimental groups did not differ significantly, we combined the results of all experimental groups into one (collapsed, robot) group and compared this with the results of the control group. Nine other studies used three arms: two treatment (robot) groups and one control group or two control and one treatment group (Ang 2014; Burgar 2011; Conroy 2011; Hsieh 2011; Hsieh 2014; Lo 2010; McCabe 2015; Rabadi 2008; Wu 2012). As we were interested in the effects of robot therapy versus any other control intervention, we either combined the results of both experimental groups in one (collapsed) group and compared this with the results of the control group, or we combined the results of both control groups in one (collapsed) group and compared this with the results of the one treatment group.

For most trials the frequency of treatment was five times a week (see Table 6 for a detailed description of time and frequency for each single study).

The intensity of treatment (in terms of duration of experimental therapy provided) ranged from 20 minutes, in Masiero 2011, or 30 minutes, in Fazekas 2007, Hesse 2005, and Masiero 2007, to 90 minutes each working day, in Daly 2005 and Hsieh 2011, or even 90 to 105 minutes each day (Hsieh 2014). For some studies, the intensity of the experimental treatment is still unclear (Amirabdollahian 2007; Kahn 2006; Lo 2010). We have provided a detailed description for each single study in Table 6 and a more detailed description of the individual therapy in studies in Characteristics of included studies.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes of the included studies varied. See Characteristics of included studies for a detailed description of the primary outcomes for each trial.

In our pooled analysis for the primary outcome, activities of daily living, we used the Barthel Index score or the modified Barthel Index (Hesse 2005; Hesse 2014; Yoo 2013), the Functional Independence Measure (Burgar 2011; Fazekas 2007; Lum 2006; Masiero 2007; Volpe 2000), the ABILHAND (Hsieh 2011; Liao 2011), the Stroke Impact Scale 3.0 (motor function and social participation section) (Kutner 2010; Lo 2010; Wu 2012), the Stroke Impact Scale 2.0 (higher scores indicate a good outcome) (Volpe 2008), and the Frenchay Arm Test (Masiero 2011).

For our secondary outcome arm function, we used the Fugl‐Meyer score or the Chedoke‐McMaster Stroke Assessment (Abdullah 2011; Mayr 2008), and in one study the Wolf Motor Function Test for our pooled analysis and conducted a separate analysis for impaired arm function (Yoo 2013). For our secondary outcome arm strength, we accepted measures such as the Motricity Index score or Medical Research Council score (higher scores indicate a good outcome) or grip force.

Eighteen included studies assessed outcomes at the end of the study, but the follow‐up assessment varied between three months and nine months after study end (see Table 6 for a detailed description of time points of assessment for each single study) (Lo 2010). As reporting data of follow‐up measures were heterogeneous and limited mostly to our primary outcome, we did not conduct separate analyses for immediate data after study end and sustained data from follow‐up after study end. We therefore undertook just one analysis (immediately after the end of the intervention).

Excluded studies

We excluded 22 trials (see Excluded studies). We have excluded 11 trials from the previous version of the review and another 11 trials (19 full texts) from the current update. See Characteristics of excluded studies for details of reasons for excluding these trials. If there was any doubt about whether or not a study should be excluded, we retrieved the full text of the article. Where the two review authors (BE and JM) disagreed, a third review author (JK) decided on inclusion or exclusion of a study.

Ongoing studies

We identified 24 ongoing studies (see Ongoing studies), which we have described in Characteristics of ongoing studies. Nine of these studies were listed as ongoing studies in the previous version of the review. After we retrieved further information, four of these ongoing studies became included studies; one became a study awaiting classification; and three remained ongoing studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

We have provided all details about the methodological quality of each included study in Characteristics of included studies.

We wrote to the trialists of all the included studies requesting clarification of some design features or missing information in order to complete the quality ratings. The correspondence was via email or letter, and we wrote reminders every month if we did not receive an answer. Most trialists provided some or all of the requested data, but for four trials we did not receive all requested data.

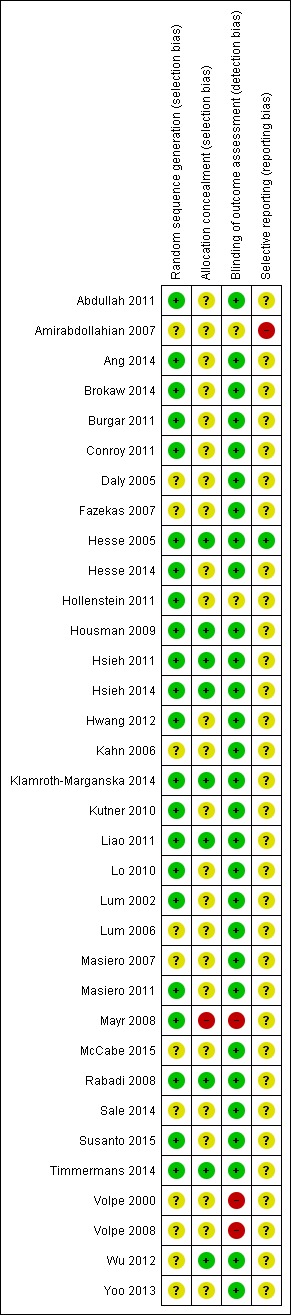

We used the 'Risk of bias' tool to assess the methodological quality of all the included trials for random allocation, concealment of allocation, and blinding of assessors. (See Characteristics of included studies and Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training versus any other intervention

See Table 1.

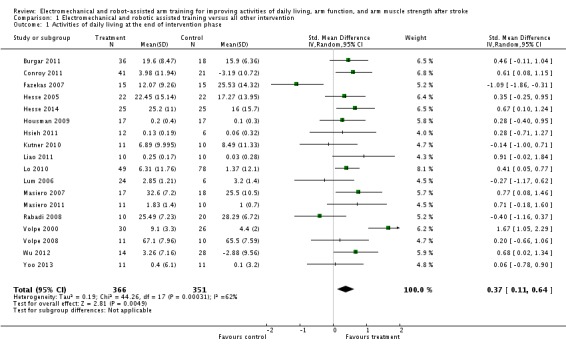

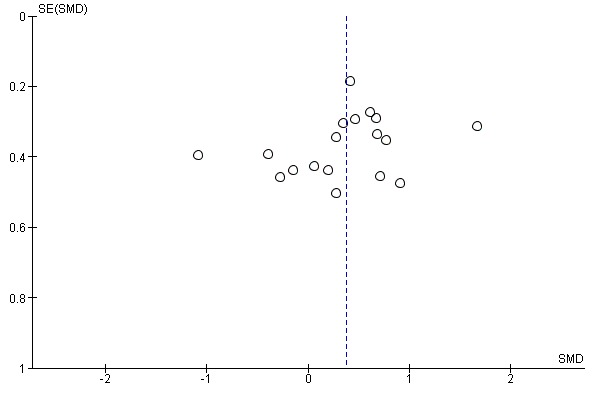

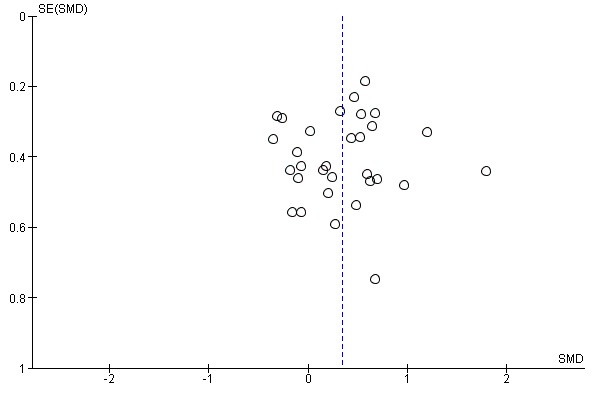

Activities of daily living at the end of the intervention phase

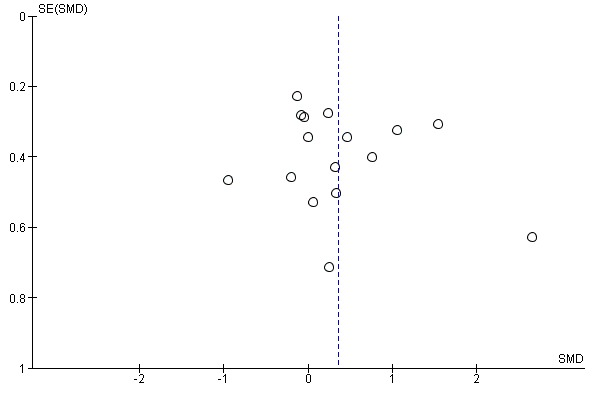

Eighteen studies with a total of 717 participants compared electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training versus any other intervention and measured activities of daily living. Electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training improved activities of daily living scores. The pooled SMD (random‐effects model) for activities of daily living was 0.37 (95% CI 0.11 to 0.64, P = 0.005, level of heterogeneity I² = 62%; Analysis 1.1). We did not find graphical evidence in a funnel plot for publication bias (Figure 3).

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Electromechanical and robotic assisted training versus all other intervention, Outcome 1 Activities of daily living at the end of intervention phase.

Figure 3.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Electromechanical and robotic assisted training versus all other intervention, outcome: 1.1 Activities of daily living at the end of intervention phase.

Activities of daily living at the end of the intervention phase: subgroup analysis comparing the acute and chronic phase

We included eight trials with a total of 320 participants in the acute and subacute phase after stroke. Electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training improved activities of daily living scores in the acute phase after stroke; the SMD (random‐effects model) was 0.53 (95% CI 0.09 to 0.96, P = 0.02, level of heterogeneity I² = 69%). We included 10 trials with a total of 397 participants in the chronic phase (more than three months after stroke). Electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training did not improve activities of daily living scores in the chronic phase after stroke; the SMD (random‐effects model) was 0.66 (95% CI ‐0.17 to 1.49, P = 0.12, level of heterogeneity I² = 92%; Analysis 1.2). The test for subgroup differences (between acute and subacute phase after stroke versus chronic phase after stroke) revealed no significant difference (P = 0.78, level of heterogeneity I² = 0%).

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Electromechanical and robotic assisted training versus all other intervention, Outcome 2 Activities of daily living at the end of intervention phase: subgroup analysis comparing acute and chronic phase.

Arm function at the end of the intervention phase

Thirty‐one studies with a total of 1078 participants compared electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training versus any other intervention and measured arm function. Electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training improved arm function of the impaired arm. As we received the change data from baseline to study end for all trials that measured arm function, we used SMDs for this comparison. The pooled SMD (random‐effects model) for arm function was 0.35 (95% CI 0.18 to 0.51, P < 0.0001, level of heterogeneity I² = 36%; Analysis 1.3). We did not find graphical evidence in a funnel plot for publication bias (Figure 4).

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 Electromechanical and robotic assisted training versus all other intervention, Outcome 3 Arm function at the end of intervention phase.

Figure 4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Electromechanical and robotic assisted training versus all other intervention, outcome: 1.3 Arm function at the end of intervention phase.

Arm muscle strength at the end of the intervention phase

Sixteen studies with a total of 568 participants compared electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training versus another intervention and measured strength of arm. Electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training improved arm muscle strength. The SMD (random‐effects model) for muscle strength was 0.36 (95% CI 0.01 to 0.70, P = 0.04, level of heterogeneity I² = 72%; Analysis 1.4). We did not find graphical evidence in a funnel plot for publication bias (Figure 5).

Analysis 1.4.

Comparison 1 Electromechanical and robotic assisted training versus all other intervention, Outcome 4 Arm muscle strength at the end of intervention phase.

Figure 5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Electromechanical and robotic assisted training versus all other intervention, outcome: 1.4 Arm muscle strength at the end of intervention phase.

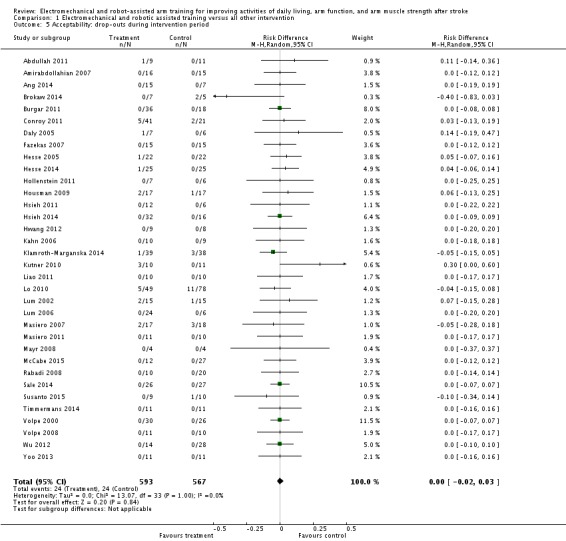

Acceptability: dropouts during the intervention period

We pooled all reported rates of participants who dropped out from all causes during the trial period. The use of electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training in people after stroke did not increase the risk of participants dropping out. The RD (random‐effects model) for dropouts was 0.00 (95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.03, P = 0.84, level of heterogeneity I² = 0%; Analysis 1.5).

Analysis 1.5.

Comparison 1 Electromechanical and robotic assisted training versus all other intervention, Outcome 5 Acceptability: drop‐outs during intervention period.

The drop‐out rate for all reasons at the end of the treatment phase was relatively low (all included studies achieved a drop‐out rate of less than 16%), but for one study this is still unclear (Amirabdollahian 2007). Twenty‐one out of 34 included studies (62%) reported no dropouts at scheduled study end (Amirabdollahian 2007; Ang 2014; Burgar 2011; Fazekas 2007; Hollenstein 2011; Hsieh 2011; Hsieh 2014; Hwang 2012; Kahn 2006; Liao 2011; Lum 2006; Masiero 2011; Mayr 2008; McCabe 2015; Rabadi 2008; Sale 2014; Timmermans 2014; Volpe 2000; Volpe 2008; Wu 2012; Yoo 2013). The highest drop‐out rate in the treatment group was 12% (five dropouts out of 41 participants; Conroy 2011). The highest drop‐out rate in the control group was 14% (11 dropouts out of 78 participants; Lo 2010) and 16.7% (three dropouts out of 18 participants; Masiero 2011). Only one study in the early acute phase after stroke reported deaths during the treatment period (Masiero 2007). However, as explained by the authors via email correspondence, both deaths occurred in the control group. Other reasons for dropouts were:

personal reasons (treatment group) (Daly 2005);

personal reasons (control group) (Housman 2009);

withdrew (treatment group) (Abdullah 2011; Klamroth‐Marganska 2014);

withdrew (control group) (Klamroth‐Marganska 2014);

injured arm in daily life (treatment group) (Housman 2009);

depression (control group) (Housman 2009);

refusing therapy (treatment group) (Hesse 2005,Klamroth‐Marganska 2014);

medical complications (treatment group) (Conroy 2011; Lum 2002);

medical reasons (control group) (Klamroth‐Marganska 2014);

exclusion (control group) (Lum 2002);

lost to follow‐up (control group) (Susanto 2015);

unable to travel (Lo 2010) or transportation difficulties (treatment group) (Kutner 2010);

limited data (Conroy 2011; Hsieh 2014);

moved (Conroy 2011; Housman 2009);

did not met inclusion criteria after study commencement (Brokaw 2014).

Safety: adverse events during the intervention period

We did not carry out a pooled analysis because the reported rates of adverse events during the intervention period were rare and not related to the therapy (as described by the study authors). The reported adverse events were as described above: death in the control group, which was not related to the therapy (information as published by the study authors; Masiero 2007); and two participants experienced medical complications in the treatment group (information as published by the study authors; Lum 2002).

Sensitivity analysis: by trial methodology

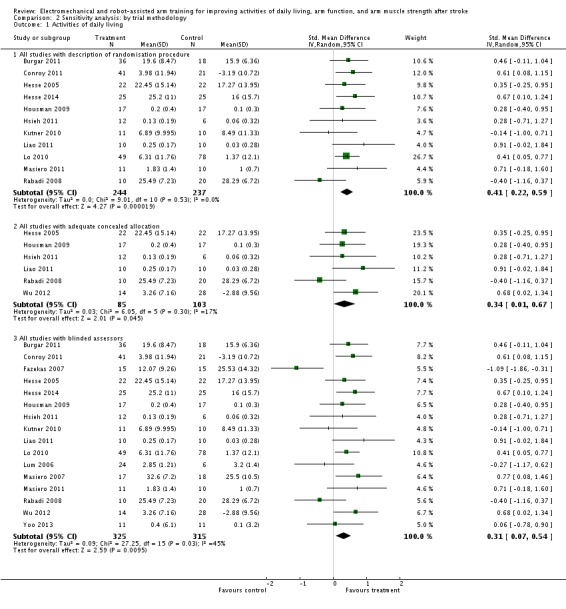

Activities of daily living

To examine the robustness of the results, we specified variables in a sensitivity analysis that we believed could influence the size of effect observed (randomisation procedure, concealed allocation, and blinding of assessors) (Analysis 2.1). We did not investigate in this sensitivity analysis if selective reporting has an influence on the size of effect observed, because we did not find sufficient information to permit such a judgement.

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 Sensitivity analysis: by trial methodology, Outcome 1 Activities of daily living.

All studies with description of randomisation procedure

We included 11 trials with a total of 481 participants with an adequate description of the randomisation procedure. Electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training improved activities of daily living. The SMD (random‐effects model) for activities of daily living was 0.41 (95% CI 0.22 to 0.59, P < 0.0001, level of heterogeneity I² = 0%).

All studies with adequately concealed allocation

We included six trials with a total of 188 participants with adequate concealment of allocation. Electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training improved activities of daily living. The SMD (random‐effects model) for activities of daily living was 0.34 (95% CI 0.01 to 0.67, P = 0.04, level of heterogeneity I² = 17%).

All studies with blinded assessors

Sixteen trials with a total of 640 participants had blinded assessors for the primary outcome. Electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training improved activities of daily living. The SMD (random‐effects model) for activities of daily living was 0.31 (95% CI 0.07 to 0.54, P = 0.009, level of heterogeneity I² = 45%).

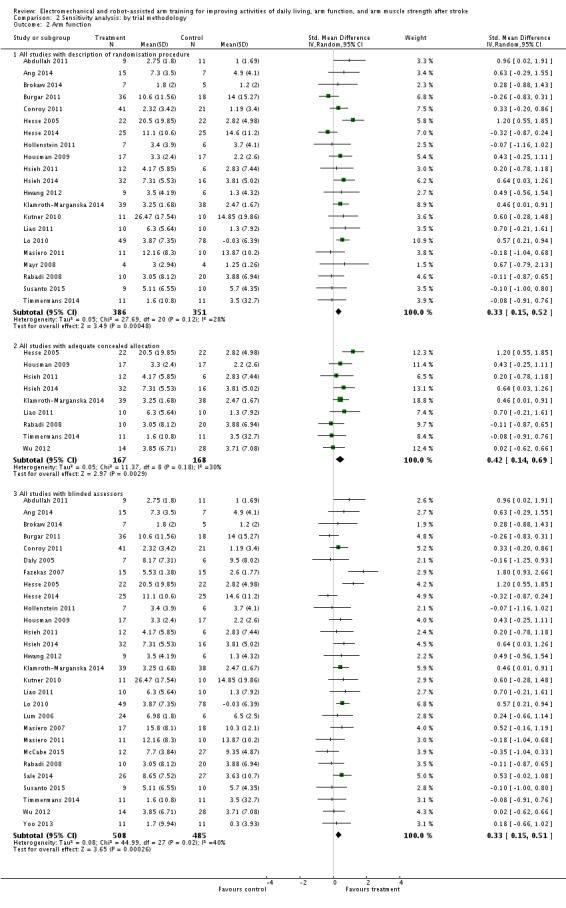

Arm function

To examine the robustness of the results, we specified variables in a sensitivity analysis that we believed could influence the size of effect observed (randomisation procedure, concealed allocation, and blinding of assessors) (Analysis 2.2).

Analysis 2.2.

Comparison 2 Sensitivity analysis: by trial methodology, Outcome 2 Arm function.

All studies with description of randomisation procedure

We included 21 trials with a total of 737 participants with an adequate description of the randomisation procedure. Electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training improved impaired arm function. The SMD (random‐effects model) for arm function was 0.33 (95% CI 0.15 to 0.52, P = 0.0005, level of heterogeneity I² = 28%).

All studies with adequately concealed allocation

We included nine trials with a total of 335 participants with adequate concealment of allocation. Electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training improved impaired arm function. The SMD (random‐effects model) for arm function was 0.42 (95% CI 0.14 to 0.69, P = 0.003, level of heterogeneity I² = 30%).

All studies with blinded assessors

We included 28 trials with a total of 993 participants with blinded assessors. Electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training improved impaired arm function. The SMD (random‐effects model) for arm function was 0.33 (95% CI 0.15 to 0.51, P = 0.0003, level of heterogeneity I² = 40%).

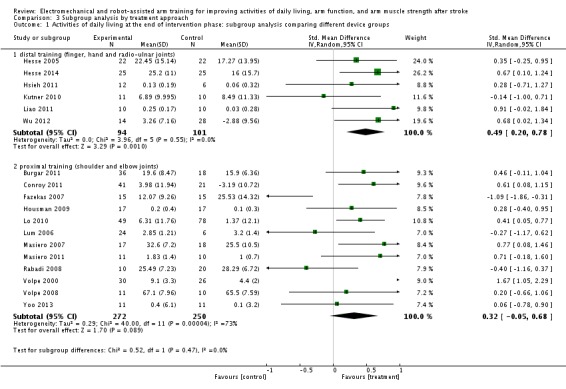

Subgroup analysis: by treatment approach

Activities of daily living at the end of intervention phase: subgroup analysis by treatment approach

The test for subgroup differences between a subgroup of participants who received mainly training for the distal arm and the hand (finger, hand, and radio‐ulnar joints) and a subgroup of participants who received training mainly of the proximal arm (shoulder and elbow joints) revealed no significant difference (P = 0.47, level of heterogeneity I² = 0%; Analysis 3.1).

Analysis 3.1.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis by treatment approach, Outcome 1 Activities of daily living at the end of intervention phase: subgroup analysis comparing different device groups.

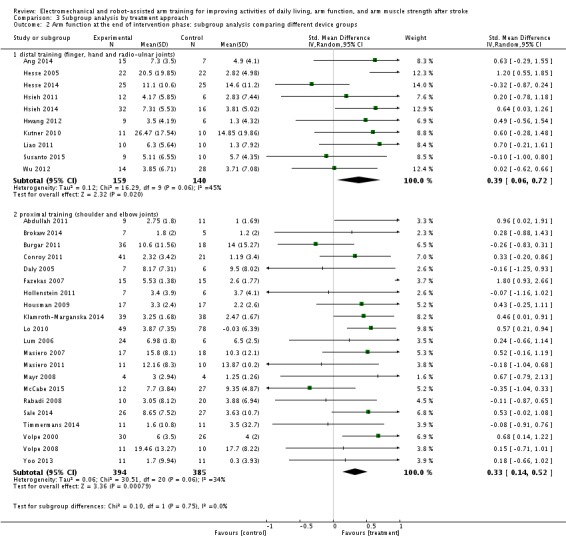

Arm function at the end of intervention phase: subgroup analysis by treatment approach

The test for subgroup differences between a subgroup of participants who received mainly training for the distal arm and the hand (finger, hand, and radio‐ulnar joints) and a subgroup of participants who received training mainly of the proximal arm (shoulder and elbow joints) revealed no significant difference (P = 0.75, level of heterogeneity I² = 0%; Analysis 3.2).

Analysis 3.2.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis by treatment approach, Outcome 2 Arm function at the end of intervention phase: subgroup analysis comparing different device groups.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We included 34 trials (involving 1160 participants) in this update of our systematic review of the effects of electromechanical and robot‐assisted therapy for improving activities of daily living, arm function, and arm muscle strength. We found that the use of electromechanical‐assistive devices in rehabilitation settings may improve activities of daily living, arm function, and arm strength, but the quality of evidence was rated as low to very low. Furthermore, adverse events and dropouts were uncommon and did not appear to be more frequent in those participants who received electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training, graded with moderate‐quality evidence. This indicates that the use of electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training devices could be safe and acceptable to most participants included in the trials that this review analysed.

Although the quality of evidence was very limited, there seems to be at least a potential benefit of electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training.

When looking at certain groups of participants, we found significant improvements of activities of daily living in the subgroup of participants treated in the acute and subacute phase. We did not find such improvements for participants treated in the chronic phase. However, our statistical subgroup comparison does not indicate that people in the acute or subacute phase after stroke may improve more than people in the chronic phase with respect to activities of daily living. Participants who received mainly training for the distal arm and the hand (finger, hand, and radio‐ulnar joints) and participants who received training mainly of the proximal arm (shoulder and elbow joints) did not differ significantly with regard to activities of daily living and arm function.

Electromechanical and robot‐assisted therapy uses devices simply as 'vehicles' to apply an increased intensity in terms of many repetitions of arm training (Kwakkel 2008; Kwakkel 2015). It seems unlikely that motor therapy provided by robots will lead to better results than motor therapy provided by humans under the premise that intensity, amount, and frequency of therapy are exactly comparable. The potential advantage of electromechanical devices, when compared with conventional therapies, may be an increase in repetitions during arm training and an increase of motivation to train. Additionally, because people using electromechanical and robot‐assistance therapy are able to practise without a therapist, this type of training has the potential to increase the number of repetitions of practise. However, in our analysis of the included studies in this review update, we were not able to compare different amounts of repetitions of arm training. The amount of repetitions and also the exact intensity, time, dose, amount, and frequency of applied therapies were not described in detail in most of the studies included here. However, almost all of the included studies (but not Yoo 2013) had an active control group, and most studies matched the time for therapy between in‐treatment and control groups. One could therefore argue that robot‐assisted arm therapy after stroke is more effective in improving activities of daily living, arm function, and arm strength than other interventions if the same time of practise is offered. Then again, as mentioned above, it could just be that more repetitions in the same time were applied by robotic‐assisted arm training (higher dose). This appears to be an important issue that should be taken into account when discussing the effectiveness of electromechanical and robot‐assisted therapy for improving activities of daily living, arm function, and arm muscle strength.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The results of this review seem to be quite generalisable for settings in industrialised countries and especially for rehabilitation centres with available electromechanical and robot‐assisted devices. However, the following factors produce uncertainty.

Most of the studies included participants with first‐ever stroke.

The majority of participants suffered from ischaemic stroke.

Nearly all of the participants were right‐handed.

The quality of evidence was rated as low to very low.

The exclusion of certain patient groups, such as people with unstable cardiovascular conditions, cognitive and communication deficits, or with a limited range of motion in the arm joints at the start of the intervention (it is well known that limited range of motion is common after stroke).

Hence, the results may be of limited applicability for people with recurrent stroke, haemorrhagic stroke, and people who are left‐handed. There is currently insufficient moderate‐ or high‐quality evidence to make conclusions about the benefits of robot therapy for improving activities of daily living, arm function, and arm muscle strength. However, as we found no evidence of side effects or harm, further research into this type of therapy appears to be justified.

The relatively tight selection criteria that have been applied to many studies should be considered. For example, the relatively younger age of people who were studied should be recognised, and also many of the people studied had no limitations of passive range of motion or were free of shoulder pain. It is well known in clinical practice that people are older and that the prevalence of comorbidities, such as pain, spasticity, or limitations to range of motion, is expected to be higher than described in the studies included here.

Additionally, electromechanical and robot‐assisted training could create additional costs of rehabilitation after stroke. The general applicability of robot therapy might therefore be limited simply due to lack of access of devices, for example in many low‐income countries, and there also appears to be fewer opportunities for therapists and patients to access robots in outpatient than in inpatient settings. All these points taken together might limit the applicability of this type of therapy in day‐to‐day clinical routine.

Quality of the evidence

We found heterogeneity regarding trial design (parallel‐group or cross‐over design, two or three or more intervention groups), therapy variables (type of device, bilateral or unilateral assistance, proximal or distal assistance, dosage of therapy), and participant characteristics (age, time poststroke, and severity of arm paresis).

There were enough studies to perform our planned sensitivity analysis examining the effects of methodological quality on the effectiveness of the intervention. We found that the effects of electromechanical‐assistive devices for improving activities of daily living and for improving arm function were quite stable and not affected by methodological quality (Analysis 2.1; Analysis 2.2).

Potential biases in the review process

The methodological rigour of Cochrane Reviews minimises bias in the process of conducting systematic reviews. A risk of publication bias, however, is present in all systematic reviews.

We searched extensively for relevant literature in databases and handsearched conference abstracts. Additionally, we contacted authors, trialists, and experts in the field for other unpublished and ongoing trials. We were unable to find graphical evidence for publication bias using funnel plots. There was heterogeneity between the trials in terms of trial design (two groups, four groups, parallel‐group or cross‐over trial, duration of study and follow‐up, and selection criteria for participants), characteristics of the therapy interventions (especially device used), and participant characteristics (length of time since stroke onset). There were also methodological differences in the mechanism of randomisation and allocation concealment methods used and blinding of primary outcomes.

After examination of the influence of methodological quality on the observed effect on activities of daily living and arm function, we did not find a change of benefit when we removed trials with unclear randomisation or allocation concealment procedures or unclear blinding.

While the methodological quality of the included trials was in general good to very good, although heterogeneous (Figure 2), trials investigating electromechanical and robot‐assisted arm training are subject to potential methodological limitations. These limitations include inability to blind the therapist and participants, so‐called contamination (provision of the intervention to the control group), and co‐intervention (when the same therapist unintentionally provides additional care to either treatment or comparison group). All these potential methodological limitations introduce the possibility of performance bias. However, as discussed above, our sensitivity analyses by methodological quality did not support this.

Some of the statistical analyses used in the review are based on parametric statistics. However, one could argue that it might not be appropriate to treat some scores for activities of daily living (for example Barthel Index score ranging from 0 to 100) and arm function (for example Fugl‐Meyer score ranging from 0 to 66) included in this review with this approach. Most of these scores were used in the included trials as continuous scales, and by others as ordinal scaled scores. However, it is unclear how this has led to an over‐ or underestimation of our described treatment effects.

As is always the case in systematic reviews, a so‐called publication bias could have potentially affected our results. The visual inspection of funnel plots for our main outcomes did not show evidence of publication bias (Figure 3; Figure 4; Figure 5), however this does not mean the complete absence of publication bias. Publication bias could therefore potentially be an issue, but it is unclear if this has led to an overestimation of our described treatment effects.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

As far as we know, no other systematic reviews of RCTs about electromechanical and robot‐assisted therapy for improving activities of daily living, arm function, and arm muscle strength have been conducted in the last three years. The most recent systematic review of this topic was done in 2008 (Kwakkel 2008). However, there are other systematic reviews within the context of our review.

A systematic review about the evidence of physiotherapy also searched for the effect of robotic training of different segments of the arm (Veerbeek 2014). The authors found 22 studies including a total of 648 participants investigating robotic arm training. Veerbeek and colleagues found small‐to‐moderate effect sizes for bilateral elbow‐wrist robotic training (four studies) compared with studies with robotic training for the shoulder, elbow, wrist, and hand. The study authors classified robotic devices on the basis of the joints they target: 1) shoulder‐elbow robots, 2) elbow‐wrist robots, and 3) shoulder‐elbow‐wrist‐hand robots, but they did not compare effect sizes (Veerbeek 2014). In our review, compared to Veerbeek 2014, the corresponding effect sizes and the differences in effect sizes between the different treatment approaches were lower. However, we were able to identify 34 trials including a total of 1160 participants. We therefore believe that our review has used a more sensitive search and hence shows a more comprehensive picture of the evidence.

Another up‐to‐date review also included trials using robotic training in combination with other interventions for people with stroke (Laver 2015). However, the authors specifically investigated the efficacy of virtual reality compared with an alternative intervention or no intervention on upper limb function and activity.

Authors' conclusions

We found that people after stroke who receive electromechanical or robot‐assisted arm training are more likely to show improvement in their activities of daily living, arm function, and muscle strength of the paretic arm, but we rated the quality of evidence as low to very low.

In practice, electromechanical or robot‐assisted arm training could increase the intensity of arm therapy. Perhaps more repetitions in the same time of therapy can be achieved if electromechanical and robot‐assisted therapy is given. Electromechanical devices could therefore be used as an adjunct to conventional therapies.

However, it is still not clear if the difference between electromechanical or robot‐assisted arm training and other interventions is clinically meaningful for most people. Perhaps one main difference between electromechanical or robot‐assisted arm training and other interventions could be an improvement in motivation due to the feedback of the device, or the novelty of a robotic device, or both. However, we can only speculate about this.