Abstract

The 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions (UTRs) regulate critical aspects of post-transcriptional gene regulation that are necessary for the maintenance of cellular homeostasis. When these processes go awry through mutation or misexpression of certain regulatory elements, the subsequent deregulation of oncogenic gene expression can drive or enhance cancer pathogenesis. Though the number of known cancer-related mutations in UTR regulatory elements has recently increased markedly due to advances in whole-genome sequencing, little is known about how the majority of these genetic aberrations contribute functionally to disease. In this review, we will explore the regulatory functions of UTRs, how they are co-opted in cancer, new technologies to interrogate cancerous UTRs, and potential therapeutic opportunities stemming from these regions.

Keywords: Untranslated region, 5’UTR, 3’UTR, somatic mutation, mRNA translation, RNA metabolism, therapy, cancer

mRNA untranslated regions in cancer

Post-transcriptional processes account for approximately 60% of variation in protein expression[1], and as such are vital for our complete understanding of proteome diversity. The 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions (UTRs) are mRNA domains that control critical post-transcriptional gene regulation processes. As regions that are transcribed, but seldom translated, the 5’ and 3’UTRs contain a myriad of regulatory elements involved in pre-mRNA processing, mRNA stability, and translation initiation. Moreover, emerging evidence suggests that the UTRs are either directly mutated or co-opted in diseases such as cancer[2,3] (Table 1). Nevertheless, most studies of cancer genomics have only focused on genetic aberrations of protein-coding regions of the genome[4,5]. This is largely because of the high cost of whole-genome sequencing in comparison to targeted exome sequencing, which historically under-captures UTRs. Though CDS-focused studies have undoubtedly increased our understanding of many cancers, these approaches have found actionable mutations in only 57% of tumors[4]. The 5’ and 3’UTRs represent genomic regions that may harbor yet undiscovered drivers of cancer pathogenesis at the post-transcriptional level.

Table 1:

Regulatory elements of the 5’ and 3’UTRs, their relevance to cancer, tools for their identification. * = known UTR mutation in gene in cancer.

| Technologies of Identification of Cis-elements | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Upstream ORFs | CDKN2A*, CDKN1B*, TMPRSS2- ERG, KRAS, NPM1, ERCC5* | eIF2α | Computational search for AUG/Kozak sequence |

| Mass Spectrometry (small peptides) | |||

| Ribosome Profiling | |||

|

Internal Ribosome Entry Sites |

p120, p53, p27 | hnRNP A1[153] | Bicistronic Assay |

| Circular RNA Reporter Assay | |||

| 5’ Hairpin Cap-Blocking Reporter Assay | |||

| microRNA Binding Site | E2F1* | miR-21, miR-17–92, miRNA-34a | miRNA & mRNA Expression Analysis[158] |

| Biotin Pulldown + RNA- Seq[159] | |||

| Alternative Poly(A) Signals | c-Jun, NRAS, MGMT | CSTF64, CFIm25 | 3’ READS[160] |

| WTTS-Seq[161] | |||

| Roar[162] | |||

| m6A | SOX2, NANOG | METTL3, METTL14, ALKBH5, FTO | m6A-Seq[107] |

| MeRIP-Seq[104] | |||

| Modified HITS-CLIP[126] |

Despite the critical role of the UTRs in controlling gene regulation, some studies argue that UTRs are not functionally important in cancer because regulatory region mutations rarely have effect sizes as large as protein-coding mutations[6,7]. However, many other studies have found evidence for the functional and clinical relevance of UTR mutations in cancer, both in genome-wide and gene-specific analyses. Whole-genome sequencing has identified areas of recurrent mutations across the UTRs of many cancer-related genes, arguing for extensive deregulation of UTR function in disease[2,3,8]. In addition to whole-genome studies, many targeted analyses have been performed of particular UTR regulatory elements, providing functional evidence for mutations in the 5’ and 3’UTRs[9–12]. In this review, we will explore the regulatory functions of UTRs, how they can be hijacked in cancer, recent advances in technology for studying UTR elements, and exciting potential therapeutic opportunities stemming from these regions.

Cis-regulatory control of cancerous gene expression in the 5’ and 3’UTRs

The 5’ and 3’UTRs primarily function through a dynamic interplay between sequence and structural motifs, collectively called cis-regulatory elements, and RNA-binding protein (RBPs) or small RNAs called trans-acting factors (Key Figure, Figure 1A). Together, they can shape the cellular proteome by tuning the metabolism and translation of specific mRNAs. Importantly, deregulation of cis-regulatory elements can drive cancer pathogenesis by inducing oncogenic gene expression. Here we will highlight a series of sequence-based and structural cis-elements implicated in cancer.

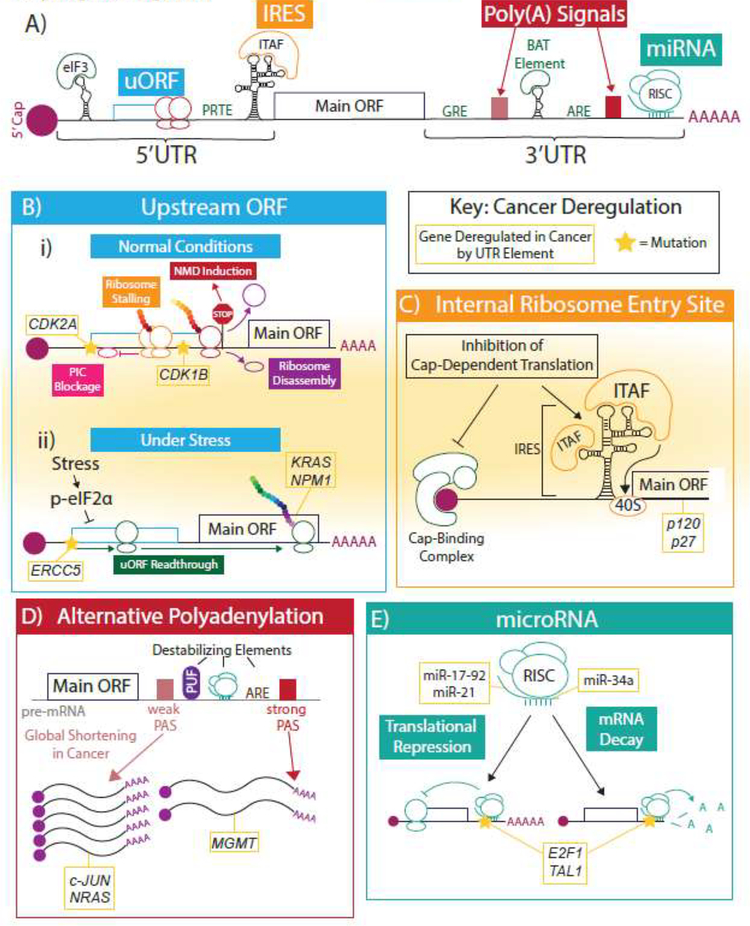

Key Figure, Figure 1: 5’ and 3’UTR elements and how they are co-opted in cancer.

(A) The 5’ and 3’UTRs contain many regulatory elements. Here we show a theroretical mRNA schematic highlighting a few salient examples that have implications in cancer: uORFs, IRESs, poly(A) signals, miRNA binding sites, and several sequence- and structure-based motifs (in green). Throughout the figure, known examples of genes deregulated by each regulatory element in cancer are shown in gold boxes. Known mutations of regulatory elements in cancer are indicated with stars. (B) In normal conditions (i), upstream ORFs (uORFs) in the 5’UTR repress translation of the main downstream ORF through PIC blockage or stalling, nonsense-mediated decay, or PIC disassembly after translation of the uORF. Under stress (ii), where the translation machinery is downregulated, the PIC more often reads through the uORF and translates the downstream ORF more efficiently. (C) Internal ribosome entry sites (IRESs) are large structural elements in the 5’UTR that can, through the binding of IRES trans-acting factors (ITAFs), recruit the 40S to the start codon independent of cap-dependent translation. (D) Many genes contain multiple polyadenylation signals (PAS) in their 3’UTR that can give rise to differentially cleaved and polyadenylated transcripts. This results in the inclusion or exclusion of other, often destabilizing, cis-elements, affecting downstream gene expression. Often, use of proximal PASs increases gene expression and distal PASs decrease gene expression. (E) MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small RNAs that integrate with the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to mediate translational repression and/or mRNA decay of specific transcripts by binding target sequences, mostly in the 3’UTR.

Examples of cis-elements in the 5’UTR associated with cancer include the 5’ terminal oligopyrimidine (5’TOP) motif[13], pyrimidine-rich translational element (PRTE)[14] or TOP-like sequence[15], the cytosine-enriched regulator of translation (CERT)[16], the G-quadruplex structure[17], and the eIF3 (eukaryotic initiation factor 3)-binding stem-loop structure[18]. All of these elements are present in subsets of mRNAs, enabling targeted control of select gene networks. The 5’TOP and PRTE/TOP-like motif are similar sequence-specific elements found in distinct parts of the 5’UTR that mediate translation initiation of mRNAs associated with protein synthesis, proliferation, metabolism, and metastasis downstream of oncogenic mTOR signaling[13,14,19]. Interestingly, a subset of genes that possess the PRTE can predict for prostate cancer aggressiveness[20]. The CERT is another sequence-based element, which was identified within the 5’UTR of mRNAs sensitive to haploinsufficiency of the translation initiation factor eIF4E. Importantly, a series of reactive oxygen species (ROS) regulators, such as FTH1, possess the CERT and are required to buffer ROS production during tumor initiation[16]. Together, these examples demonstrate that 5’ UTR motifs are important for deregulation of gene expression in cancer; however, the mechanisms by which these cis-regulatory elements drive mRNA specific translation has yet to be fully elucidated. In particular, with the exception of TOP mRNAs[21], it is unknown if these cis-elements differentially bind trans-acting factors to elicit selectivity.

In addition to sequence-specific motifs, structural elements present within the 5’UTR can regulate mRNA translation in cancer. For example, it has been shown in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia models that a series of G-quadruplex containing mRNAs are essential for the enhanced translation of oncogenes, transcription factors, and epigenetic regulators in an eIF4A dependent manner[17]. Additionally, a 5’UTR stem-loop that can bind eIF3 has been discovered that may explain previous findings that the eIF3 complex is associated with several types of cancers independent of its normal role in pre-initiation complex (PIC) assembly (Box 1). Through binding this structural motif, eIF3 can either promote or repress translation. Specifically, it was found to upregulate the proto-oncogene c-Jun and downregulate the tumor suppressive BTG1, which together could promote cancer pathogenesis[18]. The mechanism for this differential regulation remains to be determined.

Box 1: Mechanisms of Canonical mRNA Processing and Cap-Dependent Translation.

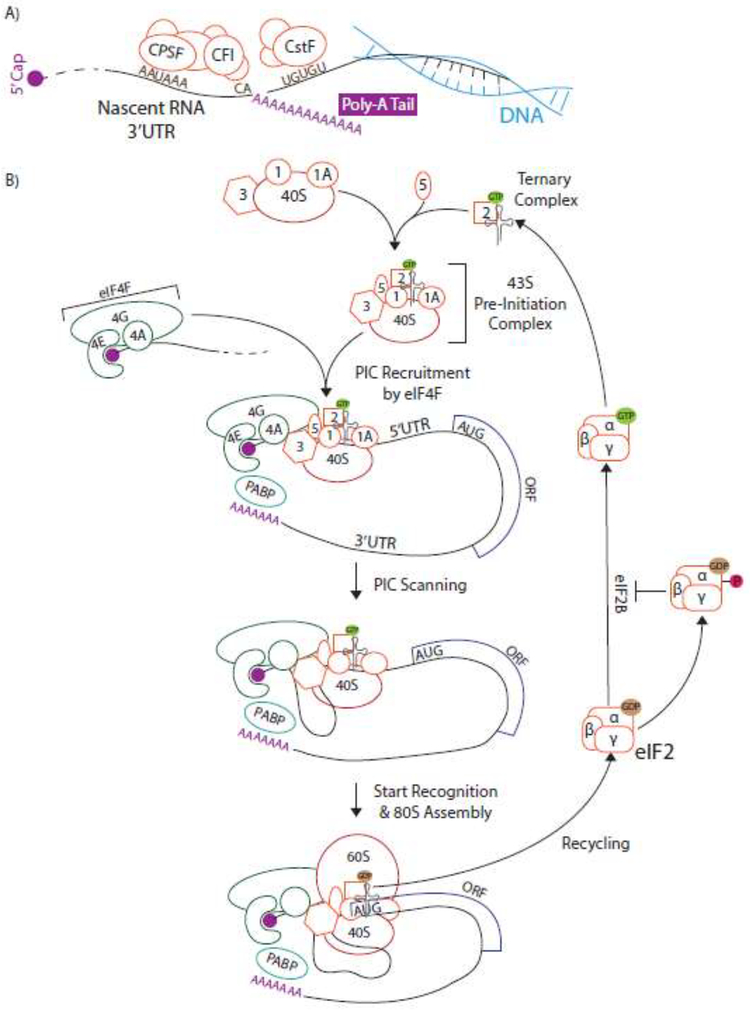

The 5’ and 3’UTRs control virtually every aspect of post-transcriptional gene regulation, from premRNA processing to translation initiation. The first regulatory processes to occur on the UTRs are capping and polyadenylation, which happen co-transcriptionally (Figure 2A). 5’ end capping with 7-methylated guanosine is required for later cap-dependent translation and stabilizes the mRNA. Polyadenylation is a two-step process of endonucleolytic cleavage of pre-mRNA then synthesis of the poly(A) tail directed by the poly(A) site (PAS). The PAS is composed of a combination of cis-elements including the core hexamer AAUAAA 10–30 nucleotides upstream of the cleavage site, a CA dinucleotide sequence, and several U/GU-rich elements[151]. Not all of these elements need to be present around the cleavage site for polyadenylation to occur, but the region’s similarity to these canonical sequences strengthens the PAS, which has consequences for alternative polyadenylation. The PAS cis-elements are recognized by multiple protein complexes, including CPSF (cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor), CstF (cleavage stimulation factor), and CFI (cleavage factor Im).

Once the mRNA is capped, polyadenylated, and exported to the cytoplasm, translation can occur. Many mRNAs in eukaryotic cells are translated in a cap-dependent manner (Figure 2B). This mode of translation starts with the assembly of the 43S pre-initiation complex (PIC), which consists of the 40S small ribosomal subunit, several initiation factors (eIF1, eIF1A, eIF3, and eIF5), and the preformed ternary complex (methionyl-initiator tRNA bound to eIF2:GTP). The eIF4F complex, composed of the cap-binding protein eIF4E, RNA helicase eIF4A, and scaffolding protein eIF4G, binds the 5’ cap of mRNA and recruits the PIC to this site. Once this complex is assembled, the PIC scans the 5’UTR for an AUG start codon. Unwinding of 5’UTR RNA secondary structure by eIF4A is required during this scanning, making some highly structured transcripts more heavily dependent on eIF4A.

When the PIC encounters a start codon in the optimal context of the Kozak sequence (A/G)CCAUGG, translation can initiate with the binding of the 60S large ribosomal subunit. Recycling of eIF2:GDP after initiation back into eIF2:GTP is an essential step for subsequent rounds of translation to occur. This process is catalyzed by eIF2B and can be inhibited by phosphorylation of the eIF2α subunit to repress global rates of translation during cellular stress. When cap-dependent translation is inhibited in this context, other methods of translation can play a critical role in maintaining cellular homeostasis. Alternate forms of translation include IRES and uORF-mediated translation, and others such as the cap- dependent but eIF4E-independent mechanism characterized by usage of a DAP5-eIF3D complex involved in translation of many known oncogenes[152].

In addition to these distinct cis-regulatory elements, the overall level of secondary structure in the 5’UTR can also affect translational regulation of distinct transcripts in cis. During cap-dependent translation initiation, secondary structure within the 5’UTR is unwound by eIF4A of the eIF4F cap-binding complex to allow the PIC to scan (Box 1). In this way, transcripts with highly structured 5’UTRs are more dependent on the eIF4F complex[22,23]. Interestingly, many oncogenes possess structured 5’UTRs including hairpins and G-quadruplexes, making expression of eIF4F components, particularly eIF4A or eIF4E, oncogenic [17,24,25]. Oncogenes may also circumvent this dependence and increase their translation efficiency by using alternative transcription start sites, thereby shortening their 5’UTRs and including fewer structural elements[26].

The 3’UTR also possesses sequence-based and structural motifs that can modulate mRNA metabolism, including AU-rich elements (ARE), G-rich elements (GRE), and the TGFβ-activated translational (BAT) element. It has been shown that ARE-containing mRNAs are overrepresented in cancer and may play a role in mitotic progression[27]. The GRE is enriched in the 3’UTRs of 10 epithelial-tomesenchymal transition (EMT)-related genes. This element promotes translation of these genes through interactions with the RNA binding protein CELF1, which is upregulated in breast cancer tissues and promotes lung metastasis in xenograft models[28]. In addition, the BAT element is a structural motif consisting of a stem-loop with an asymmetrical bulge. This structural element represses translation of two EMT-related genes, Dab2 and ILEI, via the binding of heterologous nuclear protein (hnRNP) E1. TGFβ signaling can phosphorylate hnRNP E1, releasing it from the stem-loop, increasing protein expression of these genes, and promoting EMT[29].

These sequence- and structure-specific motifs demonstrate the functional consequences of UTR-mediated deregulation in cancer. The following sections will highlight additional examples of well-studied and emerging UTR cis-elements that can promote cancer phenotypes. Importantly, many fundamental questions about cis-regulatory elements still remain. For example, it is unknown if any of these motifs are somatically mutated in cancer. Moreover, the mechanisms of many elements and what drives their selectivity in disease are open questions. Lastly, some of these elements can be found within the same mRNAs, raising the intriguing potential of cis- on cis- interactions that will require novel experimental designs to unlock their regulatory logic.

5’UTR upstream open reading frames modulate translation initiation in cancer

The upstream open reading frame (uORF) is a unique 5’UTR element that can regulate translation initiation of specific transcripts. It consists of a translatable open reading frame with a start codon upstream of the primary ORF start codon. Though there is debate as to whether uORFs are translated into functional peptides, the presence of uORFs on mRNA transcripts has been shown to modulate expression of the main downstream ORF (reviewed in[30,31]). Under normal conditions, uORFs decrease protein expression through induction of either translation repression or nonsense-mediate decay (NMD)[32]. A phenomenon called “leaky scanning” determines whether uORFs are recognized or disregarded based on the strength of the uORF AUG sequence context. If a uORF is recognized by the PIC (Box 1), it can repress translation initiation by preventing access to the downstream main ORF or by blocking the scanning of other PICs. If the uORF stop codon is recognized as a premature stop codon, it can trigger NMD degrading the transcript and likewise decreasing protein expression (Key Figure, Figure 1B)[32].

Germline or somatic mutations that create, delete, or alter uORFs can contribute to cancer phenotypes. For example, a single-point mutation that creates a novel uORF in the tumor suppressor CDKN2A decreases CDKN2A protein levels in hereditary melanoma[33]. Likewise, examination of the CDKN1B 5’UTR in a patient with inherited multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome uncovered a 4-nucleotide deletion, which induces a frameshift and lengthening of the uORF reading frame. This decreases re-initiation of translation at the CDKN1B primary ORF and lowers protein production of this tumor suppressor[34]. In addition, uORFs can influence the translation of fusion gene products. Fusion of the TMPRSS2 androgen-sensitive promoter and the ERG transcription factor coding sequence is a common oncogenic event in prostate cancer[35]. Interestingly, this fusion event can occur in a variety of ways, resulting in at least 17 unique transcripts that differ in the presence or absence of uORFs[36]. For example, the 5’UTR of the ERG-1b transcript contains 3 uORFs that repress ERG translation, while the common T1:E4 transcript does not possess repressive uORFs. It is possible that oncogenic fusion products that do not contain uORFs are selected for in cancer pathogenesis, adding another dimension of complexity to these known genetic alterations.

Though uORFs normally contribute to decreases in protein expression, in certain cases, such as under starvation or hypoxic condition, they can mediate relative increases in the expression of particular stress-related proteins (Key Figure, Figure 1B). During stress, eIF2α is phosphorylated, which reduces the rate at which eIF2 is recycled to form the ternary complex with charged initiator methionyl-tRNA and promote the initiation of translation (Box 1). In this context of global translation repression, PICs are more likely to scan past uORF start codons, resulting in increased translation initiation at previously repressed downstream canonical AUG codons[32]. This phenomenon has been observed during tumor initiation, where translation is globally reduced in skin epithelial cells except in a subset of uORF-buffered oncogenic mRNAs, such as KRAS and NPM1[37]. This buffering effect can also alter responses to chemotherapy. For example, a common variant in the DNA repair protein ERCC5 5’UTR creates a new uORF that lowers ERCC5 expression[38]. However, platinum-based agents like cisplatin induce DNA-damage and increase eIF2α phosphorylation, enabling the uORF to buffer the effect of global translation repression. The resulting increase in ERCC5 expression allows cancer cells to survive in the face of chemotherapy. Collectively, the maintenance of mRNA specific translation through uORFs during stress has implications in cancer development and therapeutic responses.

Large-scale analyses of the overall mutational landscape of uORFs in cancer have uncovered many mutations predicted to affect uORF initiation and termination[10,11]. The repeated observation of uORF-targeting mutations in disease implies their role in pathogenesis; however, the physiologic impact of the majority of these mutations have yet to be determined. Furthermore, the question of whether uORF peptides affect cancer pathogenesis is debated and yet unresolved[30,32,39]. Recent advances in mass spectrometry that can detect small and less abundant peptides[40,41] may help resolve this issue. From the current state of research into uORF-mediated gene regulation in cancer, it is evident that 5’UTR mutations or differential usage of uORFs can drive cancer phenotypes.

Alternative translation initiation in the 5’UTR by internal ribosome entry sites

Internal ribosome entry sites (IRESs) are 5’UTR structural elements consisting of stem-loops and pseudoknots that allow for an alternative method of cap- and 5’ end-independent translation initiation. They were first discovered in poliovirus and encephalomyocarditis virus[42,43], and later observed, though not immediately accepted, in cellular mRNA[44,45]. There are four major types of viral IRESs containing distinct structural domains that can bind to and recruit the translation machinery. The mechanisms of ribosome recruitment vary among these types, from requiring all canonical initiation factors aside from eIF4E to recruit the ribosome upstream of the CDS to residing in intergenic spaces and not requiring any translation initiation factors (reviewed in [46,47]). Less is known about the structure and function of mammalian IRESs, particularly because the factors involved and methods of recruiting the ribosome vary widely. Generally, the canonical cap-binding complex proteins eIF4E and eIF4G do not seem to be required[48]; however, other canonical machinery is sometimes involved. For example, eIF4A and eIF3 are involved in the c-Myc and N-Myc IRESs[49].

The IRES-mediated mechanism of non-canonical translation initiation is especially important when cells are undergoing stress that decreases the efficiency of cap-dependent translation initiation[50–54]. In these circumstances, IRESs are able to efficiently translate a subset of stress-related mRNAs using non-canonical combinations of translation initiation factors and IRES trans-acting factors (ITAFs) (Key Figure, Figure 1C). ITAFs mediate the affinity between the IRES and the translation machinery and include several RBPs, including heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs)[55]. The majority of known cellular IRESs are found immediately upstream of the initiation codon, though they can also be present in the coding sequence, resulting in truncated proteins with new cellular functions[56,57].

Stresses that can induce IRES-dependent translation include hypoxia, nutrient limitation, and inflammation. All of these stressors can be found in the tumor microenvironment, and as such, cancer growth can activate IRES-mediated translation of mRNAs associated with pathogenesis[50–53]. For example, in inflammatory breast cancer, it has been shown that p120 protein expression can be upregulated though an eIF4GI-dependent IRES-mediated translational program. This promotes E-cadherin stabilization and the development of lethal tumor emboli[58]. Thus, IRES-mediated translation can be used by cancer cells to promote tumorigenic phenotypes in the context of oncogenic stress. However, decreases in IRES-mediated translation of specific tumor suppressors can also increase cancer susceptibility, as seen in X-linked dyskeratosis congenita (X-DC). The gene responsible for this disease is the pseudouridine synthase DKC1, which is decreased in affected patients. This results in a global reduction in pseudouridylation of rRNA that decreases IRES-mediated translation of specific mRNAs, including the tumor suppressors p53 and p27[59–61]. At a functional level, it is postulated that decreased IRES-mediated translation of these critical checkpoints may contribute to cancer predisposition seen in XDC patients.

IRES-mediated translation regulates an alternative, context-specific gene expression network and could provide opportunities for the development of targeted, tumor-specific therapies. However, it is important to note some potential problems with general IRES-targeting therapeutic strategies. The bicistronic assay commonly used to study IRES translation has been criticized for its inability to distinguish between types of cap-independent translation, and as such there is not a fully accepted and standardized method to detect and validate proposed IRES elements. Several reviews have been written on this subject, detailing orthogonal assays and proper controls for careful validation of IRESs (reviewed in[62–64]). Additionally, though there are many instances in which IRES-mediated translation is responsible for protumorigenic phenotypes, it is also a necessary part of normal cellular function such as development and cell cycle progression; therefore, general suppression of IRES-associated machinery may lead to adverse side effects[61,65,66]. Furthermore, IRES-mediated translation is necessary for the expression of both tumor suppressors as well as oncogenes as discussed above[58,59]. Therefore, it is critical that we determine the regulatory distinctions that would enable the selective targeting of specific tumorigenic IRESs. This may be assisted by new high-throughput methods that are providing unprecedented insights into IRESs, including the discovery of hundreds of putative human IRESs through a high-throughput bicistronic assay for cap-independent translation[67]. These IRESs must be validated with orthogonal assays to prove they are true IRESs, versus acting through an alternate form of non-canonical translation. This work also performed IRES mutagenesis, resulting in intriguing classification of IRESs differential susceptibility to mutation. It remains to be seen how this mutational analysis might relate to actual patient mutations in IRESs and their role in cancer pathogenesis.

Deregulation of 3’UTR miRNA binding sites in cancer

MicroRNAs are one of the most extensively studied UTR-mediated post-transcriptional regulators. These non-protein-coding RNAs are 20–22 nucleotides long and generally cause decreases in protein expression through translation repression followed by mRNA decay (Key Figure, Figure 1E)[68,69]. miRNAs are produced from precursor RNAs that are processed by the Drosha-DGCR8 complex and cleaved by the protein Dicer. The mature miRNA is then incorporated into the miRNA-induced silencing complex (miRISC) to functionally target and regulate mRNAs[70]. miRNAs exert their control over the translation of specific genes through complementary base-pairing between the miRNA and target mRNAs. Though the vast majority of miRNAs target sequences in the 3’UTR of mRNAs, they can also bind to the 5’UTR[71] or within coding sequences[72]. Since miRNAs act through base-pairing of a relatively short sequence, each miRNA can have dozens to hundreds of targets throughout the genome, allowing a single miRNA to coordinately control functionally related pathways. miRNAs have been predicted to regulate the activity of >60% of all protein-coding genes in humans[73]. This abundance of target genes, along with their widespread conservation across eukaryotes, points to the ubiquitous importance of miRNAs in post-transcriptional gene regulation and hints at the numerous ways this tightly regulated control could go awry in cancer.

miRNAs have been extensively studied in the context of disease and cancer(reviewed in [70,74–77]). Expression of many miRNAs have been correlated with cancer development and prognosis in both oncogenic or tumor suppressive capacities. These include the classical “oncomiRs” miR-21[78] and the miR-17–92[79] family, which can induce or exacerbate tumor formation in mouse models, respectively. One example of a tumor suppressive miRNA is miRNA-34a, which has been shown to impair progenitor cell function and metastatic potential in prostate cancer models[80]. Intriguingly, a small molecule therapeutic has been discovered that can increase miRNA-34a expression and inhibit tumor growth in vivo[81], suggesting this form of UTR-mediated regulation can provide opportunities for therapeutic development. It is important to note that in some cases, the same miRNA can have both oncogenic and tumor suppressive functions depending on cellular context, which reveals the intricate complexities of miRNA-mediated control of gene expression networks[82,83].

While much is known about the oncogenic and tumor suppressive functions of particular miRNAs, exceedingly little is known about how somatic mutations in miRNA binding sites of target gene 3’UTRs can impact tumorigenic gene expression and cancer phenotypes. Here we will highlight one known example of how genetic alterations within the 3’UTR can drive aberrant gene expression in cancer and speculate on the future expansion of this field. Targeted 3’UTR sequencing of genes previously associated with colorectal cancer (CRC) in a cohort of CRC patients uncovered a somatic mutation in the miR-136–5p target region of the E2F1 3’UTR[84]. E2F1 is an oncogenic transcription factor that regulates the cell cycle and is associated with poor prognosis in patients[85]. This novel 3’UTR mutation was associated with 4-fold increase in expression of E2F1 in the patient. Moreover, it was shown that the mutated E2F1 3’UTR increased gene expression in reporter assays. It remains to be seen whether this mutation would produce oncogenic phenotypes in vivo; nonetheless, its discovery illustrates that non-coding mutations of specific 3’UTR miRNA binding sites may regulate expression of known oncogenes.

The recent increase in cancer whole-genome sequencing enhances the potential for discovering somatic 3’UTR mutations that impact miRNA binding. For example, one study analyzed 3’UTR somatic mutations across four cancer types to uncover alterations that disrupt miRNA targeting[12]. 3’UTR somatic mutations were discovered that altered miRNA target sites in cancer-associated genes such as TAL1, MITF, EPHA3, BMPR1B, and KDM5A. However, these have yet to be functionally tested. Additionally, large-scale computational analysis of 3’UTR sequencing data has been coupled with experimentally-validated miRNA binding sites to create a database containing somatic mutations predicted in silico to affect miRNA binding[86]. Novel large-scale functional assays will be necessary to determine the causal effects of these mutations on RNA metabolism, protein expression, and cancer phenotypes.

Alternative polyadenylation of the 3’UTR in cancer

Alternative polyadenylation (APA) is a mechanism of gene regulation conserved across many eukaryotes that occurs through the differential usage of multiple polyadenylation sites within an mRNA to change the length of the 3’UTR on the mature transcript. The polyadenylation site (PAS) is marked by several upstream and downstream consensus sequences, including the core AAUAAA hexamer, that indicate where the transcript will be cleaved and polyadenylated (Box 1 and Figure 2A). Importantly, the similarity of a sequence to the canonical motif determines the strength of each polyadenylation site[87]. Often, the PAS closer to the coding sequence (the proximal PAS) has weaker consensus sequences, and more 3’ PASs (distal PASs) have stronger consensus sequences[88]. This allows for global regulation of 3’UTR length based on conditions that favor the use of strong versus weak consensus sequences. By changing the site at which precursor mRNA is cleaved and polyadenylated, alternative polyadenylation changes the length of a transcript’s 3’UTR and consequently includes or excludes cis-regulatory elements that regulate gene expression. Since many regulatory elements within the 3’UTR destabilize mRNA or repress translation, longer 3’UTRs generally lower protein expression, whereas shorter 3’UTRs increase protein expression (Key Figure, Figure 1D), though this is not always the case. Illustratively, more than 50% of conserved microRNA binding sites are located downstream of proximal poly(A) sites and therefore are only active when the distal PAS is used over the proximal PAS[89,90].

Figure 2: Simplified schematic of mRNA processing and canonical cap-dependent translation.

A) Polyadenylation occurs co-transcriptionally in a two-step process of cleavage and adenylation. The polyadenylation signal consists of several upstream and downstream sequence motifs, which are recognized by the CPSF, CFI, and CstF complexes. B) Cap-dependent translation begins with the formation of the 43S pre-initiation complex (PIC) from the eukaryotic initiation factors eIF1, eIF1A, eIF3, eIF5, ternary complex (eIF2:GTP with meti-tRNA), and 40S small ribosomal subunit. The cap-binding eIF4F complex, consisting of eIF4E, eIF4G, and eIF4A, recruits the 43S PIC to the cap. The PIC then scans down the 5’UTR until recognition of a start codon. At the start codon, the 60S large ribosomal subunit joins and eIF2:GTP is hydrolyzed to eIF2:GDP. This must be recycled for subsequent rounds of initiation by the guanine exchange factor (GEF) eIF2B. Phosphorylation of the eIF2α subunit inhibits this GEF activity and therefore decreases availability of ternary complex and global translation levels.

Interestingly, cancer cells generally exhibit global 3’UTR shortening. One analysis across seven tumor types found 91% of genes that underwent differential APA between matched tumor and normal tissue expressed shorter transcripts in the context of cancer[91,92]. It is suggested that this systemic change helps proto-oncogenes escape regulation by suppressive elements in their 3’UTRs that normally maintain balanced expression and prevent malignancy. For example, APA in triple-negative breast cancer patients leads to 3’UTR shortening of the oncogenes c-JUN and NRAS[93]. This can result in the exclusion of inhibitory Pumilio complex recognition sites from the 3’UTR, which enables the persistent expression of these oncogenic transcripts. Interestingly, in this study, increased APA was associated with a higher incidence of lymph node invasion. In addition to increasing expression through transcript shortening, APA can repress expression by promoting longer isoforms of particular genes. An example of this in glioblastoma involves MGMT, which is a DNA repair enzyme associated with resistance to alkylating agents, such as temazolamide. Unlike normal brain tissue, gliomas utilize APA to express an isoform of MGMT with a longer 3’UTR that mediates lower mRNA levels of MGMT in part due to addition of miRNA binding sites[94]. This change in expression is associated with increased sensitivity to temazolamide in vitro. Though these examples highlight how of 3’UTR shortening increases gene expression, it is important to note that some 3’UTR elements are stabilizing[95] and therefore shortening of particular 3’UTRs may result in decreased expression.

Proximal versus distal poly(A) site usage and subsequent changes in 3’UTR length can be regulated by a variety of factors. In general, more abundant APA machinery enables the use of weaker poly(A) sites and shifts the balance towards usage of proximal, noncognate PAS and shorter 3’UTRs. In particular, upregulation of the polyadenylation factor CSTF64, an RNA-binding subunit of the cleavage stimulation factor (CSTF) complex, is associated with 3’UTR shortening in TCGA data across five tumor types[92]. Though upregulation of APA machinery like CSTF64 and CPSF3 promotes proximal PAS usage, other studies have discovered APA factors that promote distal PAS usage, including PABPN1, CFIm25, and CFIm68[96–99]. In glioblastoma, 3’UTR shortening is mediated by downregulation of the Cleavage Factor Im (CFIm) complex subunit CFIm25. Depletion of CFIm25 increases growth and invasive ability in vitro, as well as drastically increases the size of tumors in a subcutaneous glioblastoma xenograft model[100]. These studies raise the important questions of how competing APA signals are integrated to coordinate the regulation of mRNA targets and induce cancer phenotypes.

Dynamic UTR modifications in cancer

Post-transcriptional modifications of mRNA have been known to occur for decades, since the discovery of N6-methyladenosine (m6A), 5-methylcytidine (m5C) and 2’O methylation in the 1970s[101–103]. Recent advances in whole-transcriptome, high-resolution techniques to map these modifications in response to changing cellular states have revealed their dynamic nature and invigorated the field[104–107]. Furthermore, the functional identification of some of the major regulators of these processes has opened the field to deeper study of epitranscriptomic changes and their importance as modulators of gene expression.

The most abundant and well-studied mRNA modification is m6A[101–103], which is enriched in 3’UTRs[104], though also present in 5’UTRs[108]. This modification has been extensively reviewed in [109,110]. In short, the m6A machinery includes the “writer” methyltransferase complex composed of two core catalytic subunits METTL3[111] and METTL14[112–115] and several non-catalytic subunits[116], which are variably required to add methyl marks to the nitrogen-6 position of adenosine. These are countered by two AlkB family dioxygenases capable of erasing the m6A mark, FTO[117] and ALKBH5[118]. The m6A mark is read by at least five YTH-domain family proteins: YTHDF1–3, which are primarily cytoplasmic, and YTHDC1 and YTHDC2, which are nuclear[119–122], that mediate a variety of effects on gene expression. For example, YTHDF2 can either promote cap-independent translation[108] or mRNA degradation[121,123] by binding 5’UTR or 3’UTR m6A sites, respectively. The readers YTHDF1[120] and YTHDF3[124] promote mRNA translation initiation, and YTHDC1[125] can drive alternative splicing. m6A marks have also been shown to have roles in alternative polyadenylation[126] and changing mRNA structure and subsequent affinity for RNA-binding proteins[127,128].

As modifications that fine-tune mRNA metabolism and translation, particularly in response to cellular stresses that often exist in the tumor microenvironment[108], m6A marks can play major roles in deregulating cancerous gene expression. Overexpression of the methyltransferases METTL3 and METTL14 have been implicated in maintaining stemness in cancer cell populations. Knockdown of either of these genes in human leukemia cells decreases cell growth, induces apoptosis, and delays the onset of death when transplanted into mice[129,130]. Additionally, high METTL3 levels in glioblastoma enhance SOX2 m6A modification, mRNA stability, and stemness[131]. Interestingly, m6A demethylation machinery has similarly been linked to maintenance of cancer stem cells. High expression of ALKBH5 correlates with poor patient prognosis in glioblastoma[132] and increased FTO expression has been found in a subset of AMLs[133]. Knockdown of these demethylases in models of their respective tumor types decreases both cell proliferation and stem-cell features like colony formation in vitro and decreases tumorigenicity in vivo. In breast cancer, ALKBH5 has been found to have a role in the response to hypoxia in the tumor environment. In particular, exposure to hypoxia increases HIF1α/HIF2α-dependent expression of ALKBH5, leading to NANOG 3’UTR demethylation, increased NANOG transcript stabilization, and breast cancer stem cell enrichment[134]. These results illustrate the potential clinical importance of epitranscriptomic gene regulation, where these complexes may represent a new approach to target therapy-resistant cancer stem cells. However, the fact that opposing machinery can drive similar phenotypes warrants additional studies regarding the specificity of each “writer” and “eraser” in cancer.

There are other post-transcriptional mRNA modifications of the UTR that are likely deregulated in cancer, though they are considerably less well studied. These include N1-methyladenosine (m1A) and pseudouridine, both of which were first discovered on tRNA and rRNA, but more recently found and mapped on eukaryotic mRNA[105,135,136]. The functions of these RNA modifications on mRNA are not entirely clear, though m1A marks positively correlate with protein levels and it has been postulated that they can restructure 5’UTRs to influence translation [105, 137]. Pseudouridines stabilize tRNA and rRNA structure, and as such may also influence mRNA structure-related gene expression. Though the in vivo relevance is unclear, in vitro modification of mRNA uridine to pseudouridine has been shown to enhance translation by decreasing PKR activation and eIF2α phosphorylation[138]. Both m1A and pseudouridine modifications change in response to cellular stress such as heat shock and nutrient deprivation[105,136,139], indicating that these are dynamic marks on mRNA that could contribute to cancer pathogenesis. The advent of high-resolution mapping techniques coupled with genomic screening tools may provide a means to delineate their function in normal and disease states[104,105,107,135,136,139–141].

Concluding Remarks

The importance of UTRs as post-transcriptional regulatory regions in cancer has recently been expanding in earnest. Even so, research into these areas still lags far behind our knowledge and understanding of protein-coding regions, and there are still many unanswered questions for the field (see Outstanding Questions). Though attention in cancer genomics has been shifting to whole-genome sequencing, most studies of regulatory regions still primarily focus on promoter elements, neglecting the importance of UTRs and post-transcriptional regulation. This stems from the challenge posed by our incomplete understanding of UTR-mediated mechanisms of gene regulation as compared to the CDS or promoters. Whereas assigning function to CDS mutations is relatively straightforward with the knowledge of whether the mutation changes the biochemistry of the resultant protein, the path between a non-coding mutation and its potential effects is often murky. To determine the relationship between a UTR mutation and its function, we must answer: Does it affect a known cis-element or structural motif? Does it functionally alter post-transcriptional regulation? Does it work combinatorially with any other regulatory element or mutation? These questions could be addressed by adapting analyses currently performed for promoter and coding regions for UTR studies. Several analyses in recent years have used TCGA or ICGC whole-genome sequencing data to identify recurrently mutated non-coding regions in cancer and uncovered or confirmed promoter and enhancer elements with potential relevance to cancer[3,6,142,143]. These computational pipelines, some of which include searching for promoter transcription factor binding sites or comparison with RNA-seq to identify functional transcriptional differences, could be adapted to analyze mutations of known UTR cis-elements. Other new technologies, such as mRNA structural analysis through sequencing-based platforms [144–147], measurements of translation efficiency through ribosome profiling, and efficiency through ribosome profiling[148], or analysis of RBP binding to mRNA[149] could also be combined with this mutational analysis to correlate functional consequences with cancer-specific UTR mutations.

Outstanding Questions.

How do multiple cis-regulatory elements on an individual transcript influence post-transcriptional gene regulation combinatorially?

What are the functional roles of patient somatic mutations in UTR cis-regulatory elements in cancer pathogenesis and can they be targeted therapeutically?

Are patient mutations in UTRs prognostic?

What are the roles of uORF-generated peptides and may they represent cancer-specific targets for immunotherapy?

How are epitranscriptomic marks within mRNA UTRs other than m6A dysregulated in cancer?

Genome-wide mutational analysis of the UTRs combined with these types of functional correlates will be a great addition to our understanding of UTR biology in cancer; however, direct functional analysis and validation of UTR elements and such mutations is still lacking. Moreover, it is unknown how the majority of these mutations contribute to disease outcomes. Recently developed massively parallel reporter assays for 5’ and 3’UTRs, which can measure the effect of UTR elements on a variety of functional readouts from transcript stability to translational efficiency, may help bridge this gap between regulatory cancer genomics and functional consequence (examples in Table 2). Furthermore, in the era of CRISPR, functional studies or screens that target specific endogenous cis-elements to determine such cancer-related outcomes are becoming possible and informative[150]. In conjunction with clinical data, these assays may decode a new layer of driving genetic events of poorly understood or incurable cancers. As such, the UTRs represent a new frontier in post-transcriptional gene regulation in health and disease with great potential for the discovery of new biology and therapeutic opportunities (Box 2).

Table 2:

Massively parallel functional assays designed for investigation of the 5’ and 3’UTRs.

| Citation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5’UTR | 50mer | Randomized + human 5’UTR + ClinVar 5’UTR variants | Translation efficiency |

RNA-seq & polysome profiling of mRNA libraries in 293T cells | [163] |

| 5’UTR | 11mer | Randomized sequence from −6 to +5 positions around AUG | Translation efficiency |

FACS + DNA-seq of retroviral plasmid library infected into mouse lymphocytes | [164] |

| 3’UTR | 200mer | Random combinations of known 3’UTR cis- elements |

Transcript abundance, translation initiation & efficiency | RNA-seq & polysome profiling of plasmid library in HeLa cells | [165] |

| 3’UTR | 110mer | 3’UTRs of ~7,000 zebrafish transcripts |

mRNA degradation | RNA-seq over time course of mRNA libraries in zebrafish embryos | [166] |

| 3’UTR | 8mer | Random sequence inserted into endogenous 3’UTR |

Protein expression | FACS + DNA-seq of genomically- integrated dual fluorescent reporters in 293 cells | [167] |

| 3’UTR | 34mer | 3’UTR sequences conserved across vertebrates | Protein expression | FACS + DNA-seq of genomically- integrated dual fluorescent reporters in 293 cells | [168] |

| 3’UTR | 200mer + 160mer | Deep mutational scanning of active 3’UTR ARE + full coverage of CXCL2 + highly conserved sequences | mRNA stability, protein expression | RNA-seq over time course & FACS + DNA-seq of plasmid library transfected into human epithelial cells | [169] |

Box 2: Potential Therapeutic Strategies for Targeting UTRs in Cancer.

The regulatory mechanisms of the 5’ and 3’UTRs, in particular mRNA and protein interactions, provide unique opportunities for novel therapeutic strategies in cancer. Furthermore, the fact that UTRs can control gene expression in a highly specific manner raises the intriguing possibility of therapeutically targeting historically undruggable cancer drivers. For example, small molecules have recently been tested that can specifically target and inhibit IRES-mediated translation of genes such as the oncogene MYC by blocking interactions between ITAFs and IRES RNA structures[153,154]. These have shown in vitro and in vivo efficacy when used alone or in combination with other targeted therapeutics. Importantly, given the contextual manner in which IRES-mediated translation is operative in cancer, it will be imperative to carefully define cellular states which are addicted to this form of translation in future studies.

Another intriguing possibility is to directly target key mRNA structures within the UTRs. Somatic mutations to the UTRs may generate cancer specific conformations that could represent novel molecular handles, which can be therapeutically targeted. This phenomenon has been seen in some human diseases, but the extent of shape-based changes in cancer remains unknown[155]. Importantly, small molecule inhibitors have recently been developed that target specific mRNA conformations and inhibit bacterial growth[156]. This raises the exciting potential of creating therapeutics that target oncogenic mRNA structures.

Another avenue of treatment offered by UTR-mediated regulatory mechanisms is the targeting of novel, tumor-specific antigens created by IRES-mediated or uORF-specific translation. For instance, MELOE-1 and MELOE-2 are highly specific melanoma antigens produced by IRES-dependent translation of the meloe long non-coding RNA[157]. These could provide cancer specific targets through the development of antigen specific CAR-T cells. In addition to cancer-specific antigens, there is also evidence that uORF mediated translation can generate entirely new repertoire of potential neoantigens, which may have implications for immune-oncology[37].

Highlights.

The untranslated regions (UTRs) of mRNA represent important mediators of post-transcriptional gene regulation.

The UTR’s control of mRNA metabolism and translation can be usurped in cancer.

Somatic alterations to the UTRs are emerging as potential gene specific drivers of cancer etiology.

Protein-RNA and RNA-RNA interactions within regulatory elements of the UTRs may present novel therapeutic opportunities in cancer.

Acknowledgements

We apologize to the many scientists whose work we were unable to cite that have greatly contributed to the field due to space constraints. We thank Drs. Adam Geballe, Patrick Paddison, Cristian Bellodi, John T. Cunningham, and Craig Stumpf for critical reading of this review. We also thank Dr. Jennifer M. Shen for editing the manuscript. S.L.S. is supported by the University of Washington Cell and Molecular Biology Training Grant (T32 GM007270). A.C.H. is supported by NIH R01 CA230617, a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award for Medical Scientist, a Prostate Cancer Foundation Challenge Award, and a V Foundation Scholar Grant.

Glossary

- Post-transcriptional gene regulation

mechanisms occurring after transcription that contribute to protein expression, including splicing, transcript stability, translation efficiency, and protein degradation

- Driver mutation

somatic or germline mutations in critical cancer-related genes that are the causative reasons for disease phenotypes in patients

- Cis-regulatory element

defined region of sequence or structural motif that regulates the gene expression of the transcript on which it occurs

- Trans-acting factor

protein or nucleic acid that is encoded by one gene and acts to regulate expression of a separate gene

- Epitranscriptome

referring to endogenous marks (e.g. methylation) added to nucleotides of RNA transcripts

- Massively parallel reporter assay

high-throughput assay designed to functionally test the effects of thousands of sequence elements at once through the comparative measurement of a reporter construct, usually using sequencing

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Schwanhüusser B et al. (2011) Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature 473, 337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mularoni L et al. (2016) OncodriveFML: a general framework to identify coding and non-coding regions with cancer driver mutations. Genome Biol. 17, 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinhold N et al. (2014) Genome-wide analysis of noncoding regulatory mutations in cancer. Nat. Genet 46, 1160–1165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey MH et al. (2018) Comprehensive Characterization of Cancer Driver Genes and Mutations. Cell 173, 371–385.e18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Network TCGAR (2014) Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature 507, 315–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hornshøj H et al. (2018) Pan-cancer screen for mutations in non-coding elements with conservation and cancer specificity reveals correlations with expression and survival /631/67/69 /631/114 article. npj Genomic Med. 3, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fredriksson NJ et al. (2014) Systematic analysis of noncoding somatic mutations and gene expression alterations across 14 tumor types. Nat. Genet 46, 1258–1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puente XS et al. (2015) Non-coding recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature 526, 519–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeraati M et al. (2017) Cancer-associated noncoding mutations affect RNA G-quadruplex-mediated regulation of gene expression. Sci. Rep 7, 708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulz J et al. (2018) Loss-of-function uORF mutations in human malignancies. Sci. Rep 8, 2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wethmar K et al. (2016) Comprehensive translational control of tyrosine kinase expression by upstream open reading frames. Oncogene 35, 1736–1742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziebarth JD et al. (2012) Integrative Analysis of Somatic Mutations Altering MicroRNA Targeting in Cancer Genomes. PLoS One 7, e47137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyuhas O and Kahan T (2015) The race to decipher the top secrets of TOP mRNAs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gene Regul. Mech 1849, 801–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsieh AC et al. (2012) The translational landscape of mTOR signalling steers cancer initiation and metastasis. Nature 485, 55–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thoreen CC et al. (2012) A unifying model for mTORC1-mediated regulation of mRNA translation. Nature 485, 109–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Truitt ML et al. (2015) Differential Requirements for eIF4E Dose in Normal Development and Cancer. Cell 162, 59–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolfe AL et al. (2014) RNA G-quadruplexes cause eIF4A-dependent oncogene translation in cancer. Nature 513, 65–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee ASY et al. (2015) eIF3 targets cell-proliferation messenger RNAs for translational activation or repression. Nature 522, 111–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunningham JT et al. (2014) Protein and nucleotide biosynthesis are coupled by a single rate-limiting enzyme, PRPS2, to drive cancer. Cell 157, 1088–1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheridan CM et al. (2015) YB-1 and MTA1 protein levels and not DNA or mRNA alterations predict for prostate cancer recurrence. Oncotarget 6, 7470–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Philippe L et al. (2018) La-related protein 1 (LARP1) repression of TOP mRNA translation is mediated through its cap-binding domain and controlled by an adjacent regulatory region. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 1457–1469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Svitkin YV et al. (2001) The requirement for eukaryotic initiation factor 4A (elF4A) in translation is in direct proportion to the degree of mRNA 5′ secondary structure. RNA 7, 382–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grens A and Scheffler IE (1990) The 5’- and 3’-untranslated regions of ornithine decarboxylase mRNA affect the translational efficiency. J. Biol. Chem 265, 11810–11816 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubio CA et al. (2014) Transcriptome-wide characterization of the eIF4A signature highlights plasticity in translation regulation. Genome Biol. 15, 476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruggero D et al. (2004) The translation factor eIF-4E promotes tumor formation and cooperates with c-Myc in lymphomagenesis. Nat. Med 10, 484–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dieudonné FX et al. (2015) The effect of heterogeneous Transcription Start Sites (TSS) on the translatome: Implications for the mammalian cellular phenotype. BMC Genomics 16, 986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hitti E et al. (2016) Systematic Analysis of AU-Rich Element Expression in Cancer Reveals Common Functional Clusters Regulated by Key RNA-Binding Proteins. Cancer Res. 76, 4068–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaudhury A et al. (2016) CELF1 is a central node in post-transcriptional regulatory programmes underlying EMT. Nat. Commun 7, 13362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaudhury A et al. (2010) TGF-β-mediated phosphorylation of hnRNP E1 induces EMT via transcript-selective translational induction of Dab2 and ILEI. Nat. Cell Biol 12, 286–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hinnebusch AG et al. (2016) Translational control by 5’-untranslated regions of eukaryotic mRNAs. Science 352, 1413–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris DR and Geballe AP (2000) Upstream Open Reading Frames as Regulators of mRNA Translation. Mol. Cell. Biol 20, 8635–8642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barbosa C et al. (2013) Gene Expression Regulation by Upstream Open Reading Frames and Human Disease. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu L et al. (1999) Mutation of the CDKN2A 5’ UTR creates an aberrant initiation codon and predisposes to melanoma. Nat. Genet 21, 128–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Occhi G et al. (2013) A Novel Mutation in the Upstream Open Reading Frame of the CDKN1B Gene Causes a MEN4 Phenotype. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adamo P and Ladomery MR (2016) The oncogene ERG: a key factor in prostate cancer. Oncogene 35, 403–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zammarchi F et al. (2013) 5′ UTR Control of Native ERG and of Tmprss2:ERG Variants Activity in Prostate Cancer. PLoS One 8, e49721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sendoel A et al. (2017) Translation from unconventional 5′ start sites drives tumour initiation. Nature 541, 494–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Somers J et al. (2015) A common polymorphism in the 5’ UTR of ERCC5 creates an upstream ORF that confers resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy. Genes Dev. 29, 1891–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Somers J et al. (2013) A perspective on mammalian upstream open reading frame function. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 45, 1690–1700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yeom J et al. (2017) Comprehensive analysis of human protein N-termini enables assessment of various protein forms. Sci. Rep 7, 6599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slavoff SA et al. (2013) Peptidomic discovery of short open reading frame–encoded peptides in human cells. Nat. Chem. Biol 9, 59–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jang SK et al. (1988) A segment of the 5’ nontranslated region of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA directs internal entry of ribosomes during in vitro translation. J. Virol 62, 2636–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pelletier J et al. (1988) Cap-independent translation of poliovirus mRNA is conferred by sequence elements within the 5’ noncoding region. Mol. Cell. Biol 8, 1103–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Macejak DG and Sarnow P (1992) Association of heat shock protein 70 with enterovirus capsid precursor P1 in infected human cells. J. Virol 66, 1520–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johannes G and Sarnow P (1998) Cap-independent polysomal association of natural mRNAs encoding cmyc, BiP, and eIF4G conferred by internal ribosome entry sites. RNA 4, 1500–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mailliot J and Martin F (2018) Viral internal ribosomal entry sites: four classes for one goal. WIREs RNA 9, 1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee K-M et al. (2017) Regulation Mechanisms of Viral IRES-Driven Translation. Trends Microbiol. 25, 546–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prévôt D et al. Conducting the initiation of protein synthesis: the role of eIF4G. Biol. cell 95, 141–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spriggs KA et al. (2009) Canonical initiation factor requirements of the Myc family of internal ribosome entry segments. Mol. Cell. Biol 29, 1565–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shi Y et al. (2016) Therapeutic potential of targeting IRES-dependent c-myc translation in multiple myeloma cells during ER stress. Oncogene 35, 1015–1024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 51.Philippe C et al. (2016) PERK mediates the IRES-dependent translational activation of mRNAs encoding angiogenic growth factors after ischemic stress. Sci. Signal 9, ra44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li Q et al. (2016) ATF2 translation is induced under chemotherapeutic drug-mediated cellular stress via an IRES-dependent mechanism in human hepatic cancer Bel7402 cells. Oncol. Lett 12, 4795–4802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Halaby MJ et al. (2015) Translational control protein 80 stimulates IRES-mediated translation of p53 mRNA in response to DNA damage. Biomed Res. Int 2015, 708158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bonnet-Magnaval F et al. (2016) Hypoxia and ER stress promote Staufen1 expression through an alternative translation mechanism. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 479, 365–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Komar AA and Hatzoglou M Cellular IRES-mediated translation: The war of ITAFs in pathophysiological states, Cell Cycle, 10 15-January-(2011), Taylor & Francis, 229–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Komar AA et al. (2003) Internal initiation drives the synthesis of Ure2 protein lacking the prion domain and affects [URE3] propagation in yeast cells. EMBO J. 22, 1199–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cornelis S et al. (2000) Identification and characterization of a novel cell cycle-regulated internal ribosome entry site. Mol. Cell 5, 597–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Silvera D et al. (2009) Essential role for eIF4GI overexpression in the pathogenesis of inflammatory breast cancer. Nat. Cell Biol 11, 903–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bellodi C et al. (2010) Loss of function of the tumor suppressor DKC1 perturbs p27 translation control and contributes to pituitary tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 70, 6026–6035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bellodi C et al. (2010) Deregulation of oncogene-induced senescence and p53 translational control in X-linked dyskeratosis congenita. EMBO J. 29, 1865–1876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoon A et al. (2006) Impaired control of IRES-mediated translation in X-linked dyskeratosis congenita. Science 312, 902–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Terenin IM et al. (2017) A researcher’s guide to the galaxy of IRESs. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 74, 1431–1455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gilbert WV (2010) Alternative ways to think about cellular internal ribosome entry. J. Biol. Chem 285, 29033–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jackson RJ (2013) The current status of vertebrate cellular mRNA IRESs. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 5, a011569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin W et al. (2014) Loss of PINK1 attenuates HIF-1α induction by preventing 4E-BP1-dependent switch in protein translation under hypoxia. J. Neurosci 34, 3079–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xue S et al. (2015) RNA regulons in Hox 5’ UTRs confer ribosome specificity to gene regulation. Nature 517, 33–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weingarten-Gabbay S et al. (2016) Systematic discovery of cap-independent translation sequences in human and viral genomes. Science 351, aad4939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Djuranovic S et al. (2012) miRNA-mediated gene silencing by translational repression followed by mRNA deadenylation and decay. Science 336, 237–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Meijer HA et al. (2013) Translational repression and eIF4A2 activity are critical for microRNA-mediated gene regulation. Science 340, 82–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peng Y and Croce CM (2016) The role of MicroRNAs in human cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther 1, 15004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhou H and Rigoutsos I (2014) MiR-103a-3p targets the 5’ UTR of GPRC5A in pancreatic cells. RNA 20, 1431–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hausser J et al. (2013) Analysis of CDS-located miRNA target sites suggests that they can effectively inhibit translation. Genome Res. 23, 604–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Friedman RC et al. (2009) Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 19, 92–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rupaimoole R and Slack FJ (2017) MicroRNA therapeutics: towards a new era for the management of cancer and other diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 16, 203–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Di Leva G et al. (2014) MicroRNAs in Cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis 9, 287–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jansson MD and Lund AH (2012) MicroRNA and cancer. Mol. Oncol 6, 590–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hayes J et al. (2014) MicroRNAs in cancer: biomarkers, functions and therapy. Trends Mol. Med 20, 460–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Medina PP et al. (2010) OncomiR addiction in an in vivo model of microRNA-21-induced pre-B-cell lymphoma. Nature 467, 86–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.He L et al. (2005) A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature 435, 828–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu C et al. (2011) The microRNA miR-34a inhibits prostate cancer stem cells and metastasis by directly repressing CD44. Nat. Med 17, 211–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xiao Z et al. (2014) A small-molecule modulator of the tumor-suppressor mir34a inhibits the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 74, 6236–6247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Babar IA et al. (2012) Nanoparticle-based therapy in an in vivo microRNA-155 (miR-155)-dependent mouse model of lymphoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 109, E1695–E1704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Levati L et al. (2011) MicroRNA-155 targets the SKI gene in human melanoma cell lines. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 24, 538–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lopes-Ramos CM et al. (2017) E2F1 somatic mutation within miRNA target site impairs gene regulation in colorectal cancer. PLoS One 12, e0181153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Engelmann D and Pützer BM (2012) The dark side of E2F1: in transit beyond apoptosis. Cancer Res. 72, 571–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bhattacharya A et al. (2013) SomamiR: A database for somatic mutations impacting microRNA function in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D977–D982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cheng Y et al. (2006) Prediction of mRNA polyadenylation sites by support vector machine. Bioinformatics 22, 2320–2325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tian B et al. (2005) A large-scale analysis of mRNA polyadenylation of human and mouse genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 201–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sandberg R et al. (2008) Proliferating cells express mRNAs with shortened 3’ untranslated regions and fewer microRNA target sites. Science 320, 1643–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ji Z et al. (2009) Progressive lengthening of 3’ untranslated regions of mRNAs by alternative polyadenylation during mouse embryonic development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 106, 7028–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mayr C and Bartel DP (2009) Widespread shortening of 3’UTRs by alternative cleavage and polyadenylation activates oncogenes in cancer cells. Cell 138, 673–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Xia Z et al. (2014) Dynamic analyses of alternative polyadenylation from RNA-seq reveal a 3’-UTR landscape across seven tumour types. Nat. Commun 5, 5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Miles WO et al. (2016) Alternative Polyadenylation in Triple-Negative Breast Tumors Allows NRAS and c-JUN to Bypass PUMILIO Posttranscriptional Regulation. Cancer Res. 76, 7231–7241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kreth S et al. (2013) In human glioblastomas transcript elongation by alternative polyadenylation and miRNA targeting is a potent mechanism of MGMT silencing. Acta Neuropathol. 125, 671–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zybura-Broda K et al. (2018) HuR (Elavl1) and HuB (Elavl2) Stabilize Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 mRNA During Seizure-Induced Mmp-9 Expression in Neurons. Front. Neurosci 12, 224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Li W et al. (2015) Systematic Profiling of Poly(A)+ Transcripts Modulated by Core 3’ End Processing and Splicing Factors Reveals Regulatory Rules of Alternative Cleavage and Polyadenylation. PLOS Genet. 11, e1005166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gruber AR et al. (2012) Cleavage factor Im is a key regulator of 3’ UTR length. RNA Biol. 9, 1405–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jenal M et al. (2012) The Poly(A)-Binding Protein Nuclear 1 Suppresses Alternative Cleavage and Polyadenylation Sites. Cell 149, 538–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.de Klerk E et al. (2012) Poly(A) binding protein nuclear 1 levels affect alternative polyadenylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 9089–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Masamha CP et al. (2014) CFIm25 links alternative polyadenylation to glioblastoma tumour suppression. Nature 510, 412–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Desrosiers R et al. (1974) Identification of methylated nucleosides in messenger RNA from Novikoff hepatoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 71, 3971–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rottman F et al. (1974) Sequences containing methylated nucleotides at the 5’ termini of messenger RNAs: possible implications for processing. Cell 3, 197–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dubin DT and Taylor RH (1975) The methylation state of poly A-containing messenger RNA from cultured hamster cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2, 1653–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Meyer KD et al. (2012) Comprehensive Analysis of mRNA Methylation Reveals Enrichment in 3′ UTRs and near Stop Codons. Cell 149, 1635–1646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dominissini D et al. (2016) The dynamic N1-methyladenosine methylome in eukaryotic messenger RNA. Nature 530, 441–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dai Q et al. (2017) Nm-seq maps 2′-O-methylation sites in human mRNA with base precision. Nat. Methods 14, 695–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dominissini D et al. (2012) Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 485, 201–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Meyer KD et al. (2015) 5′ UTR m6A Promotes Cap-Independent Translation. Cell 163, 999–1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nachtergaele S and He C (2017) The emerging biology of RNA post-transcriptional modifications. RNA Biol. 14, 156–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Roundtree IA et al. (2017) Dynamic RNA Modifications in Gene Expression Regulation. Cell 169, 1187–1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bokar JA et al. (1997) Purification and cDNA cloning of the AdoMet-binding subunit of the human mRNA (N6-adenosine)-methyltransferase. RNA 3, 1233–47 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Liu J et al. (2014) A METTL3–METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat. Chem. Biol 10, 93–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ping X-L et al. (2014) Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res. 24, 177–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Schwartz S et al. (2014) Perturbation of m6A writers reveals two distinct classes of mRNA methylation at internal and 5’ sites. Cell Rep. 8, 284–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wang Y et al. (2014) N6-methyladenosine modification destabilizes developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol 16, 191–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Deng X et al. (2018) RNA N6-methyladenosine modification in cancers: current status and perspectives. Cell Res. 28, 507–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Jia G et al. (2011) N6-Methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat. Chem. Biol 7, 885–887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zheng G et al. (2013) ALKBH5 Is a Mammalian RNA Demethylase that Impacts RNA Metabolism and Mouse Fertility. Mol. Cell 49, 18–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zhou J et al. (2015) Dynamic m(6)A mRNA methylation directs translational control of heat shock response. Nature 526, 591–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wang X et al. (2015) N(6)-methyladenosine Modulates Messenger RNA Translation Efficiency. Cell 161, 1388–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wang X et al. (2014) N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature 505, 117–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Xu C et al. (2014) Structural basis for selective binding of m6A RNA by the YTHDC1 YTH domain. Nat. Chem. Biol 10, 927–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Du H et al. (2016) YTHDF2 destabilizes m(6)A-containing RNA through direct recruitment of the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex. Nat. Commun 7, 12626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Li A et al. (2017) Cytoplasmic m6A reader YTHDF3 promotes mRNA translation. Cell Res. 27, 444–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Xiao W et al. (2016) Nuclear m 6 A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates mRNA Splicing. Mol. Cell 61, 507–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ke S et al. (2015) A majority of m6A residues are in the last exons, allowing the potential for 3’ UTR regulation. Genes Dev. 29, 2037–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Liu N et al. (2015) N6-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA–protein interactions. Nature 518, 560–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Liu N et al. (2017) N 6-methyladenosine alters RNA structure to regulate binding of a low-complexity protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 6051–6063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Weng H et al. (2018) METTL14 Inhibits Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Differentiation and Promotes Leukemogenesis via mRNA m6A Modification. Cell Stem Cell 22, 191–205.e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Vu LP et al. (2017) The N6-methyladenosine (m6A)-forming enzyme METTL3 controls myeloid differentiation of normal hematopoietic and leukemia cells. Nat. Med 23, 1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Visvanathan A et al. (2018) Essential role of METTL3-mediated m 6 A modification in glioma stem-like cells maintenance and radioresistance. Oncogene 37, 522–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Zhang S et al. (2017) m 6 A Demethylase ALKBH5 Maintains Tumorigenicity of Glioblastoma Stem-like Cells by Sustaining FOXM1 Expression and Cell Proliferation Program. Cancer Cell 31, 591–606.e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Li Z et al. (2017) FTO Plays an Oncogenic Role in Acute Myeloid Leukemia as a N6-Methyladenosine RNA Demethylase. Cancer Cell 31, 127–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zhang C et al. (2016) Hypoxia induces the breast cancer stem cell phenotype by HIF-dependent and ALKBH5-mediated m 6 A-demethylation of NANOG mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 113, E2047–E2056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Li X et al. (2016) Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals reversible and dynamic N1-methyladenosine methylome. Nat. Chem. Biol 12, 311–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Carlile TM et al. (2014) Pseudouridine profiling reveals regulated mRNA pseudouridylation in yeast and human cells. Nature 515, 143–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Zhou H et al. (2016) m1A and m1G disrupt A-RNA structure through the intrinsic instability of Hoogsteen base pairs. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 23, 803–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Anderson BR et al. (2010) Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA enhances translation by diminishing PKR activation. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 5884–5892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Schwartz S et al. (2014) Transcriptome-wide Mapping Reveals Widespread Dynamic-Regulated Pseudouridylation of ncRNA and mRNA. Cell 159, 148–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kuppers D et al. (2018) N6-methyladenosine mRNA marking promotes selective translation of regulons required for human erythropoiesis. bioRxiv DOI: 10.1101/457648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Li X et al. (2015) Chemical pulldown reveals dynamic pseudouridylation of the mammalian transcriptome. Nat. Chem. Biol 11, 592–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Melton C et al. (2015) Recurrent somatic mutations in regulatory regions of human cancer genomes. Nat. Genet 47, 710–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Rheinbay E et al. (2017) Recurrent and functional regulatory mutations in breast cancer. Nature 547, 55–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Watters KE and Lucks JB (2016) Mapping RNA Structure In Vitro with SHAPE Chemistry and Next-Generation Sequencing (SHAPE-Seq). In Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) 1490 pp. 135–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Wan Y et al. (2016) Genome-Wide Probing of RNA Structures In Vitro Using Nucleases and Deep Sequencing. In Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) 1361 pp. 141–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Ritchey LE et al. (2017) Structure-seq2: sensitive and accurate genome-wide profiling of RNA structure in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, e135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]