Abstract

The reactions between S-nitrosothiols and phosphite esters, including P(OPh)3, P(OBn)3, and P(OEt)3, were studied. Two different conjugated adducts, thiophosphoramidates and phosphorothioates, were formed, depending on the structures of the S-nitrosothiol substrate (e.g., primary vs tertiary). These reactions proceeded under mild conditions, and the reaction mechanisms were studied using experiments and calculations.

Graphical Abstract

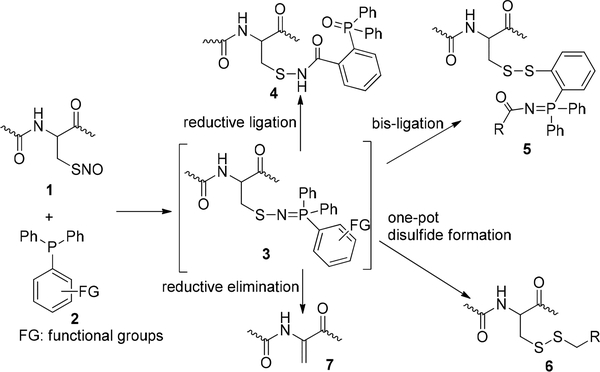

S-Nitrosylation is a nitric oxide mediated post-translational modification, which plays important regulatory roles in many biological systems.1 Although many proteins (>3000) have been suggested to be the targets of S-nitrosylation, the detection of S-nitrosylation is still a challenge. This is primarily due to the instability of the products of S-nitrosylation, i.e., S-nitrosothiols (SNOs). Previously, chemistry studies on SNOs were focused on their preparation and degradation, while the reactivity of SNOs received less attention.2 In the past several years, our group has been studying bioorthogonal reactions of SNOs, with the aim of developing new methods for the detection of protein S-nitrosylation. To this end, we have discovered several triarylphosphine-mediated reactions of SNOs, including (Scheme 1): (1) reductive ligation, which converts SNOs to sulfonamides; (2) bis-ligation, which converts SNOs to disulfide-iminophosphorane products; (3) one-step disulfide formation; and (4) reductive elimination, which leads to dehydroalanine products.3 Aza-ylides, which are formed from triarylphosphines and SNOs, are the key intermediates in these reactions. By manipulating the functional groups on the phosphines, different conjugates could be obtained.

Scheme 1.

Reactions of SNOs with Triarylphosphines

It is known that aza-ylides could also be generated from phosphite substrates.4 Therefore, we wondered if phosphites could be used to trap SNOs. To the best of our knowledge, the reaction between SNOs and phosphites has not been reported. We predicted that the products would be different from those of the reactions with phosphine substrates. The reaction may proceed through two possible pathways (Scheme 2). In pathway a, the phosphite attacks the nitroso group (N=O) to generate the aza-phosphite ylide I, which should undergo hydrolysis to yield the thiophosphoramidate product II. Alternatively (pathway b), the phosphite attacks the sulfur atom of the S−N bond directly, similar to the reaction reported by King et al.5 This should afford the thiophosphonium salt III. Hydrolysis of III should produce phosphorothioate IV. With this hypothesis in mind, we studied the reactions between SNOs and phosphites. Herein, we report our results.

Scheme 2.

Two Possible Reaction Pathways between SNO and Phosphites

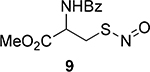

First, we screened the reactions with three phosphite substrates: P(OPh)3, P(OBn)3, and P(OEt)3. A tertiary SNO (TrSNO 8) and a primary SNO 9 were employed as the models. The reactions were carried out in a mixed MeCN/PBS buffer system. Since the formation of aza-ylides from SNOs requires at least 2 equiv of phosphites, excess phosphites (3.4 equiv) were used in our studies. Interestingly, P(OPh)3 did not show any reactivity toward both SNOs, probably due to its low nucleophilicity. P(OBn)3 and P(OEt)3 showed good reactivity. Clean reactions were noticed, and isolable products 10 and 11 were obtained in good yields (Table 1). The products obtained from the TrSNO were found to be the thiophosphoramidates 10a and 10b, while the primary SNO 9 produced the phosphorothioates 11a and 11b.

Table 1.

Screening of Phosphites

| entry | RSNO | P(OR1)3 | product | yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P(OPh)3 | N.R. | N.R. | |

| 2 |  |

P(OBn)3 |  |

75 |

| 3 | P(OEt)3 | 82 | ||

| 4 | P(OPh)3 | N.R. | N.R. | |

| 5 |  |

P(OBn)3 |  |

61 |

| 6 | P(OEt)3 |  |

83 | |

Encouraged by these results, we had to decide whether P(OBn)3 or P(OEt)3 should be used to further understand the reactions of SNOs. Since our ultimate goal was to develop orthogonal reactions for SNOs, control reactions with the disulfide substrate 12 were then tested for P(OBn)3 and P(OEt)3. As shown in Scheme 3, P(OEt)3 effectively broke the disulfide bond to produce phosphorothioate 11b in excellent yield. In contrast, P(OBn)3 did not react with the disulfide under the same conditions. These results suggested that P(OBn)3 was a mild reagent and might be selective toward SNOs. Therefore, it was selected for further studies.

Scheme 3.

Reactions of Disulfide 12 with P(OBn)3 and P(OEt)3

We then optimized the reaction conditions using P(OBn)3. As primary SNOs are more biologically relevant, a cysteine SNO 9 was used in this experiment (see Supporting Information for Table S1). MeCN/PBS (1/1) was the optimum solvent system for this reaction (Table S1, entries 1−4). The effects of pH were studied (Table S1, entries 4−7). The neutral to weak acidic pH levels gave similar results, while a basic pH (10) led to a slightly decreased yield. This was probably due to the increase in instability of the SNO under basic conditions. We also found that an increase in the loading of P(OBn)3 resulted in higher yields (Table S1, entries 8−11). Since the difference between the yields for 5 and 10 equiv was not significant, we decided to use 5 equiv of P(OBn)3 in our studies.

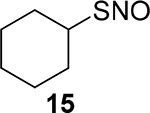

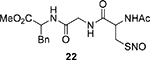

We next tested the generality of this reaction using a series of SNO derivatives. As shown in Table 2, all the tertiary SNO substrates 8, 13, and 14 yielded the corresponding thiophosphoramidates 10a, 13a, and 14a as the major products in good yields. When the secondary and primary SNO derivatives 9, 15−23 were used, only phosphorothioate products were obtained, all in good yields. In the case of the S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) 23, an endogenous SNO, the partially hydrolyzed phosphorothioate 23a was the isolated product. Clearly P(OBn)3 is an effective reagent which can convert SNOs to stable products under mild conditions.

Table 2.

Reactions between SNOs and P(OBn)3

| entry | RSNO | product (yield%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | TrSNO 8 |

|

| 2 |  |

|

| 3 |  |

|

| 4 |  |

|

| 5 |  |

|

| 6 |  |

|

| 7 |  |

|

| 8 |  |

|

| 9 |  |

|

| 10 |  |

|

| 11 |  |

|

| 12 |  |

|

| 13 |  |

|

Based on the obtained products, the mechanisms of the reactions were proposed (Scheme 4). For tertiary SNOs, since thiophosphoramidates were the major products, the phosphite preferably reacts with the nitroso group via pathway A, due to steric hindrance. In this process, 2 equiv of P(OBn)3 were consumed and aza-ylide 26 was formed. Hydrolysis of 26 provided thiophosphoramidate 27. For secondary and primary SNOs, while both pathways seem possible, we feel pathway A is more feasible as the nitroso group is more accessible than the S atom. We attempted to obtain thiophosphoramidates from secondary and primary SNOs. However, all the attempts failed, even with less than 2 equiv of P(OBn)3. Only reduced yields of phosphorothioate products were obtained (Table S1). These results suggest that the formation of thiophosphoramide is the rate-determining step of the process. Moreover, secondary- and primary-SNO derived thiophosphoramidates are unstable in the presence of phosphites. They are likely to react with P(OBn)3 to form phosphorothioate 30 and dibenzyl phosphoramidate 29. However, we cannot completely rule out pathway B, since the direct cleavage of the S−N bond would form the same products with the release of the nitroxyl (HNO). It is known that HNO could react with phosphines to form phosphine oxide and aza-ylides.6 Similarly, the reaction of HNO with P(OBn)3 should produce 25 and 31. Hydrolysis of 31 should yield 29.

Scheme 4.

Mechanisms of the Reactions between SNO and P(Obn)3

To better understand the mechanisms, we carried out the quantum calculations using density functional theory (DFT). All the calculations were conducted using Gaussian 097 at the B3LYP/6–311+G(d,p) level,8 applying the PCM water solvation model9 (see Supporting Information for the calculated geometries). In order to save the calculation time, we selected MeSNO and t-BuSNO to represent primary- and tertiary-SNO and P(OMe)3 as the model of P(OBn)3 in calculations. We first explored the energy differences between attacking the nitroso group vs S atom by P(OMe)3. As we expected and discussed above, attacking the nitroso group is energetically more favorable than the S center by 3 kcal/mol (Supporting Information Figure S1). We then focused our attention toward whether thiophosphoramidate 27 could react further with P(OMe)3 to form 28 in both MeSNO and tBuSNO. The two located transition states indicate that the activation energy barrier for t-BuSNO is about 24 kcal/mol, 7 kcal/mol higher than that for MeSNO (Supporting Information Figure S2). The calculated results support that (1) pathway A is more favorable than pathway B and (2) for tBuSNO the reaction would not easily go further after 27 is formed. This explains how all tertiary SNOs gave thiophosphoramidates 27 as the main products. It should be noted that although a simplified model P(OMe)3 was used to carry out the calculations, we do not think the results of P(OMe)3 would give misleading information to interpret the proposed mechanisms. Even with this stronger reagent (compared to P(OBn)3) the calculated energy difference between two pathways is as high as 7 kcal/mol. We would expect a higher energy difference between the two pathways if P(OBn)3 was used since the steric clashes will be bigger in the TS_T structure than in the TS_P structure due to the bigger size of Bn group. In this regard, the conclusion derived from the calculations is still valid.

In conclusion, new reactions between SNO and phosphite esters were studied. Phosphorothioates were obtained as the main products from primary SNO substrates, while thiophosphoramidates were obtained as the main products from tertiary SNOs. Mechanistic studies reveal that the reaction between SNOs and phosphite esters could proceed via two reaction pathways and yields two different conjugated products depending on the structure of SNO compounds. Owing to the excellent stability of the reaction products and the very mild reaction conditions, this reaction is potentially useful for understanding SNO biology.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (R01GM125968 to M.X.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 201502064 to C.L), and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2016R1D1A3B03931686 to C.M.P).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b03393.

Experimental and characterization of each compound, as well as theoretical calculation data (PDF)

REFERENCES

- (1) (a).Majmudar JD; Martin BR Biopolymers 2014, 101, 173–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Stomberski CT; Hess DT; Stamler JS Antioxid. Redox Signaling 2012, DOI: 10.1089/ars.2017.7403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Stamler JS; Lamas S; Fang FC Cell 2001, 106, 675–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Gaston B; Singel D; Doctor A; Stamler JS Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 2006, 173, 1186–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hess DT; Matsumoto A; Nudelman R; Stamler JS Nat. Cell Biol 2001, 3, E46–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Marshall HE; Hess DT; Stamler JS Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2004, 101, 8841–8842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Foster MW; McMahon TJ; Stamler JS Trends Mol. Med 2003, 9, 160–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Lancaster JR Jr. Nitric Oxide 2008, 19, 68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Bosworth CA; Toledo JC Jr.; Zmijewski JW; Li Q; Lancaster JR Jr. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2009, 106, 4671–4676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Broniowska KA; Hogg N Antioxid. Redox Signaling 2012, 17, 969–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Hogg N Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 2002, 42, 585–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Zhang Y; Hogg N Free Radical Biol. Med 2005, 38, 831–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Whalen EJ; Foster MW; Matsumoto A; Ozawa K; Violin JD; Que LG; Nelson CD; Benhar M; Keys JR; Rockman HA; Koch WJ; Daaka Y; Lefkowitz RJ; Stamler JS Cell 2007, 129, 511–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Benhar M; Forrester MT; Hess DT; Stamler JS Science 2008, 320, 1050–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (o) Paulsen CE; Carroll KS Chem. Rev 2013, 113, 4633–4679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2) (a).Zhang C; Biggs TD; Devarie-Baez NO; Shuang S; Dong C; Xian M Chem. Commun 2017, 53, 11266–11277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang PG; Xian M; Tang X; Wu X; Wen Z; Cai T; Janczuk A Chem. Rev 2002, 102, 1091–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Oae S; Shinhama K Org. Prep. Proced. Int 1983, 15, 165–198. [Google Scholar]

- (3) (a).Wang H; Xian M Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2008, 47, 6598− 6601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang H; Zhang J; Xian MJ Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 13238–13239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhang J; Wang H; Xian M Org. Lett 2009, 11, 477–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhang J; Wang H; Xian MJ Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 3854–3855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhang J; Li S; Zhang D; Wang H; Whorton AR; Xian M Org. Lett 2010, 12, 4208–4211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Wang H; Xian M Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2011, 15, 32–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Park C-M; Niu W; Liu C; Biggs TD; Guo J; Xian M Org. Lett 2012, 14, 4694− 4697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Park C-M; Biggs TD; Xian MJ Antibiot 2016, 69, 313–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4) (a).Chapyshev SV; Chernyak AV; Yakushchenko IK J. Heterocycl. Chem 2016, 53, 970–974. [Google Scholar]; (b) Vallee MRJ; Majkut P;´ Wilkening I; Weise C; Müller G; Hackenberger CPR Org. Lett 2011, 13, 5440–5443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Bechtold E; Reisz JA; Klomsiri C; Tsang AW; Wright MW; Poole LB; Furdui CM; King SB ACS Chem. Biol 2010, 5, 405–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Reisz JA; Klorig EB; Wright MW; King SB Org. Lett 2009, 11, 2719–2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Frisch MJ; Trucks GW; Schlegel HB; Scuseria GE; Robb MA; Cheeseman JR; Scalmani G; Barone V; Petersson GA; Nakatsuji H; Li X; Caricato M; Marenich AV; Bloino J; Janesko BG; Gomperts R; Mennucci B; Hratchian HP; Ortiz JV; Izmaylov AF; Sonnenberg JL; Williams; Ding F; Lipparini F; Egidi F; Goings J; Peng B; Petrone A; Henderson T; Ranasinghe D; Zakrzewski VG; Gao J; Rega N; Zheng G; Liang W; Hada M; Ehara M; Toyota K; Fukuda R; Hasegawa J; Ishida M; Nakajima T; Honda Y; Kitao O; Nakai H; Vreven T; Throssell K; Montgomery JA Jr.; Peralta JE; Ogliaro F; Bearpark MJ; Heyd JJ; Brothers EN; Kudin KN; Staroverov VN; Keith TA; Kobayashi R; Normand J; Raghavachari K; Rendell AP; Burant JC; Iyengar SS; Tomasi J; Cossi M; Millam JM; Klene M; Adamo C; Cammi R; Ochterski JW; Martin RL; Morokuma K; Farkas O; Foresman JB; Fox DJ Gaussian 09, revision B.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Becke AD Phys. Rev. A: At., Mol., Opt. Phys 1988, 38, 3098–3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9) (a).Cances E; Mennucci B; Tomasi JJ Chem. Phys 1997, 107, 3032–3041. [Google Scholar]; (b) Barone V; Cossi M; Tomasi JJ Comput. Chem 1998, 19, 404–417. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.