Abstract

The emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance highlights the urgent need for new antibiotics. Organoarsenicals have been used as antimicrobials since Paul Ehrlich’s salvarsan. Recently a soil bacterium was shown to produce the organoarsenical arsinothricin. We demonstrate that arsinothricin, a non-proteinogenic analog of glutamate that inhibits glutamine synthetase, is an effective broad-spectrum antibiotic against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, suggesting that bacteria have evolved the ability to utilize the pervasive environmental toxic metalloid arsenic to produce a potent antimicrobial. With every new antibiotic, resistance inevitably arises. The arsN1 gene, widely distributed in bacterial arsenic resistance (ars) operons, selectively confers resistance to arsinothricin by acetylation of the α-amino group. Crystal structures of ArsN1 N-acetyltransferase, with or without arsinothricin, shed light on the mechanism of its substrate selectivity. These findings have the potential for development of a new class of organoarsenical antimicrobials and ArsN1 inhibitors.

Nadar, Chen, Dheeman et al. show that arsinothricin, an arsenic-containing non- proteinogenic amino acid analog of glutamate, is an effective broad-spectrum antibiotic through inhibition of glutamine synthetase. This study suggests a possibility of developing a new class of antimicrobials that thwart microbial resistance to arsinothricin.

Introduction

Arsenic is the most pervasive environmental toxic element1. Here we describe how bacteria harness arsenic to create a potent broad-spectrum antibiotic. New antibiotics are urgently needed because the emergence of resistance has rendered nearly every clinically used antibiotic ineffectual. Human tuberculosis, the top global infectious disease killer, which is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, has become even more difficult to treat due to the drug resistance2. The World Health Organization declares multidrug-resistant tuberculosis a global public health crisis, calling for a pressing need for development of new and innovative antibiotics3. In addition to M. tuberculosis, the World Health Organization recently issued a global priority pathogen list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria that pose the greatest threat to human health to guide and promote research and development of new antibiotics4.

The use of arsenicals as antimicrobial and anticancer agents is well-established5,6. The first synthetic antimicrobial agents were the organoarsenicals atoxyl (p-aminophenylarsenate, also known as p-arsanilic acid) and salvarsan (arsphenamine). While salvarsan is no longer in clinical use, the organoarsenical melarsoprol, developed in 1949, is still recommended by the World Health Organization for treatment of second-stage Trypanosoma brucei sleeping sickness7. Atoxyl and the related synthetic aromatic arsenicals roxarsone (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylarsenate) and nitarsone (4-nitrophenylarsenate) are antimicrobials used for the prevention of Coccidia and Histomonas infections in poultry8. Although no longer in wide use in the United States, roxarsone is still produced and utilized worldwide. Finally, arsenic trioxide is currently the treatment of choice in humans for all-trans retinoic acid unresponsive acute promyelocytic anemia9.

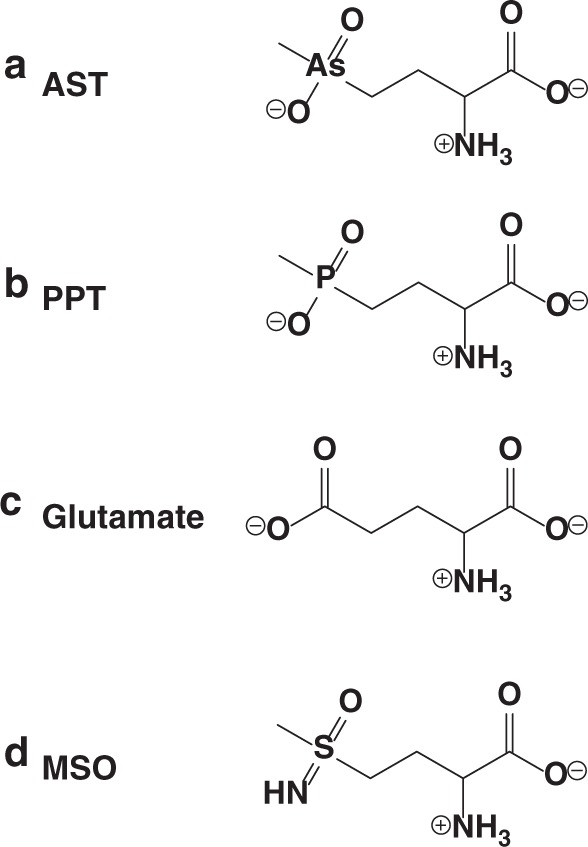

Here we demonstrate that a recently discovered arsenic-containing natural product, arsinothricin (2-amino-4-(hydroxymethylarsinoyl)butanoate, AST) (Fig. 1a), produced by the rice rhizosphere microbe Burkholderia gladioli GSRB0510, has broad-spectrum antibiotic activity. Biosynthetic AST is a mimetic of the Streptomyces antibiotic L-phosphinothricin (2-amino-4-(hydroxymethylphosphinyl)butanoate or L-PPT) with an arsenic in place of the phosphorus of L-PPT (Fig. 1b). L-AST and L-PPT are non-proteinogenic amino acid analogs of l-glutamate (Fig. 1c) and act through inhibition of glutamine synthetase. Most toxic arsenicals contain trivalent As(III). AST is unusual in being a highly toxic pentavalent organoarsenical. It is chemically unrelated to other organoarsenicals and has the potential to be the progenitor of a new class of organoarsenical antibiotics. With every new antibiotic, resistance inevitably arises. The enzyme PPT N-acetyltransferase (PAT) confers resistance to PPT by acetylating its α-amino group. A curious observation has been that many arsenic resistance (ars) operons have an arsN1 gene that encodes a pat ortholog. Why an enzyme for PPT resistance should be in an ars operon was a mystery. The identification of AST as a natural product suggested that the biological function of ArsN could be to act as an AST resistance. Here we show that ArsN1 acetylates both AST and PPT but with higher affinity for AST, indicating that ArsN1 is an AST-selective N-acetyltransferase. We crystallized ArsN1 and solved the apo and substrate-bound structures. This knowledge can be utilized to design new and novel drugs that evade or inhibit resistance mechanisms.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of glutamate and analogs. a Arsinothricin (AST); b phosphinothricin (PPT); c glutamate; d methionine sulfoximine (MSO)

Results

AST is a broad-spectrum antibiotic

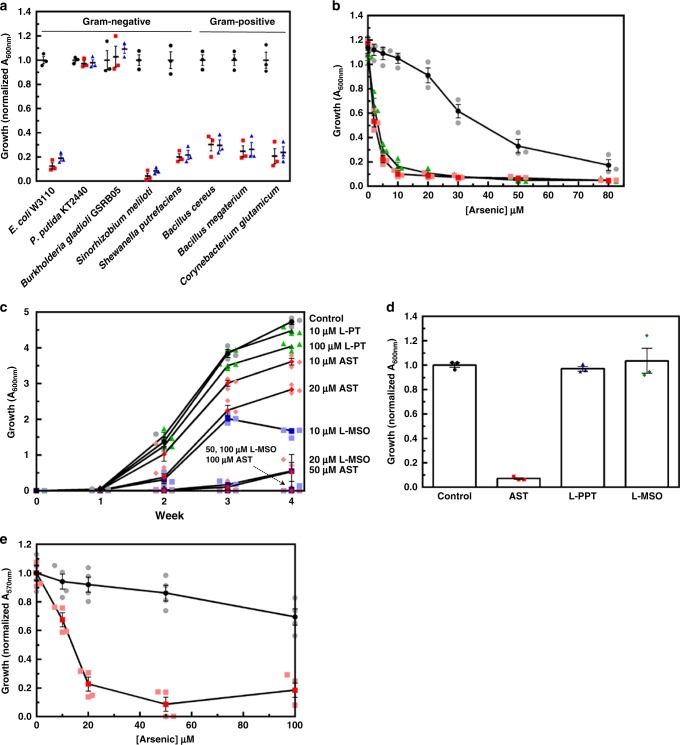

To determine whether AST has antibiotic activity, we examined its ability to inhibit growth of bacteria using environmental isolates. AST was equally effective against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (Fig. 2a). Each species was inhibited to the same degree by 25 μM AST and 400 μM L-PPT, except for B. gladioli GSRB05 and Pseudomonas putida KT2440. B. gladioli GSRB05 is the producer of AST10, so it is not unexpected that this strain might be resistant to the antibiotic it produces. As discussed below, the arsN1 gene confers resistance in P. putida KT2440. Our results demonstrate that AST is a broad-spectrum antibiotic effective against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. In Escherichia coli, AST is considerably more inhibitory than inorganic As(III) and is similar to that of highly toxic trivalent methylarsenite (MAs(III)) (Fig. 2b). Given that, in general, pentavalent arsenicals are relatively benign and much less toxic compared to trivalent species11, this is a striking result. To our best knowledge, except thiolated species6, AST is the only known pentavalent arsenic species that exhibits high toxicity.

Fig. 2.

AST is a broad-spectrum antibiotic. a AST inhibits growth of both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Strains were cultured in M9 medium in the absence (black circles) or presence of 25 µM AST (red squares) or 400 µM L-PPT (blue triangles) as described in Methods, and growth was estimated from the A600nm after 24 h. Data are the mean ± SE (n = 3). b Pentavalent AST is more toxic than trivalent As(III). The toxicity of AST (triangles) was compared with MAs(III) (squares) and As(III) (circles) in E. coli AW3110 grown in M9 medium. Growth was estimated from A600nm after 24 h. Data are the mean ± SE (n = 3). Dark- and light-colored symbols represent means and individual data points, respectively. c Effect of AST on mycobacterial growth. Cultures of M. bovis BCG were inoculated at an initial density of 105 cells/ml and then incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for up to 4 weeks in the absence (Control, circles) or presence of the indicated concentrations of GS inhibitors L-MSO (squares), L-PPT (triangles) or AST (diamonds). Growth was estimated from A600nm. Data are the mean ± SE (n = 3). Dark- and light-colored symbols represent means and individual data points, respectively. d Effect of AST on carbapenem-resistant E. cloacae. Cells were cultured in M9 medium in the absence (Control) or presence of 25 µM AST, L-PPT or L-MSO, with growth estimated from the A600nm after 24 h. Data are the mean ± SE (n = 3). e Cytotoxicity of AST in human monocytes. Human THP-1 cells were incubated in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of As(III) (circles) or AST (squares) for 24 h, and viability was determined using a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl) 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay, as described in Methods. Data are the mean ± SE (n = 4). Dark- and light-colored symbols represent means and individual data points, respectively

AST inhibits glutamine synthetase

The mechanism of action of L-PPT is irreversible inhibition of bacterial glutamine synthetase12. L-PPT also inhibits plant glutamine synthetase, which is the basis for its use as the broad-spectrum systemic herbicide Glufosinate13. Because of the structural similarity with PPT (Fig. 1b), it was reasonable to propose that the target of AST is also bacterial glutamine synthetase. We compared the effect of AST and L-PPT on purified E. coli glutamine synthetase activity. The Km of glutamine synthetase was found to be 2.7 ± 0.6 mM for l-glutamate, consistent with the previous determination12. The observed Ki values for AST and L-PPT are 0.3 ± 0.05 μM and 0.4 ± 0.15 μM, respectively, indicating that AST is as effective an inhibitor of glutamine synthetase as is L-PPT.

AST is an effective antibiotic with pathogenic bacteria

Inhibition of glutamine synthetase has been proposed to be a potential therapeutic strategy against tuberculosis14. Pathogenic mycobacteria, including M. tuberculosis, secrete large amounts of an extracellular glutamine synthetase that is involved in synthesis of the poly-α-l-glutamine layer, a cell wall component that is found exclusively in pathogenic strains and considered essential to their virulence15. In fact, L-methionine S-sulfoximine (L-MSO) (Fig. 1d), the first glutamine synthetase inhibitor described16, effectively inhibits M. tuberculosis growth both in vitro and in vivo15,17. To examine the potential of AST as a drug for tuberculosis, we analyzed the effect of AST on a related pathogenic strain, M. bovis BCG, and compared it with L-PPT and L-MSO (Fig. 2c). AST inhibits mycobacterial growth at concentrations comparable to L-MSO and is a much better inhibitor than L-PPT. AST also effectively inhibits growth of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacter cloacae (ATCC BAA-2341), which belongs to the highest priority category in the World Health Organization global priority pathogens list3, whereas other glutamine synthetase inhibitors have no effect on growth of E. cloacae (Fig. 2d). Among the glutamine synthetase inhibitors examined, only AST effectively inhibits growth of both Mycobacterium and Enterobacter pathogens, which strongly suggests that AST is a useful lead compound for potential development of new antimicrobial drugs against antibiotic-resistant pathogens. Importantly, AST is much less cytotoxic to human monocytes compared with inorganic arsenite (Fig. 2e). This low cytotoxicity further supports the potential of AST as a lead compound for drug development.

PpArsN1 confers resistance to arsinothricin

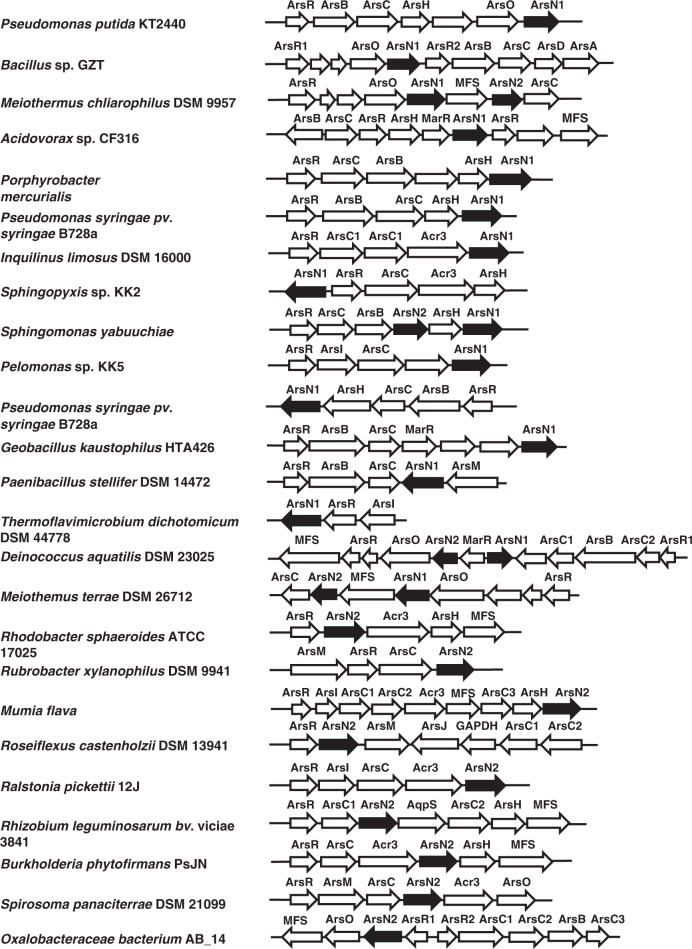

Bacterial resistance to L-PPT is conferred by phosphinothricin N-acetyltransferases (PATs)18. These inactivate L-PPT by acetylation of the α-amino group, which prevents binding to glutamine synthetase12. These genes have been used to construct transgenic PPT-resistant plants, allowing D,L-PPT to be used for weed control13. Many bacterial ars operons have genes that encode putative GCN5-related N-acetyltransferases19 (Fig. 3). These genes can be sorted into two clades (Fig. 4). The genes in Clade 1 encode proteins more closely related to phosphinothricin N-acetyltransferases, whereas products of the genes from Clade 2 are more closely related to glutamate N-acetyltransferases (N-acetylglutamate synthases)20. We term the former arsN1 and the latter arsN2. In this report we focus on arsN1. The arsN1 gene of P. putida KT2440 (PparsN1, accession number AAN67541) was originally termed phoN1 because it was shown to confer L-PPT resistance21. The genome of P. putida KT2440 has two ars operons (ars1 and ars2), and the ars1 operon contains the PparsN1 gene. Wild type cells are L-PPT resistance, while cells with a deletion of both ars operons (Δars1,2) are sensitive to L-PPT (Fig. 5a). Introduction of PparsN1 into E. coli AW3110 confers L-PPT resistance, which was consistent with previous studies21.

Fig. 3.

Compilation of bacterial ars operons with arsN genes. Shown are representative ars operons containing arsN genes (black fill). GenBank accession numbers are given in “Methods” section

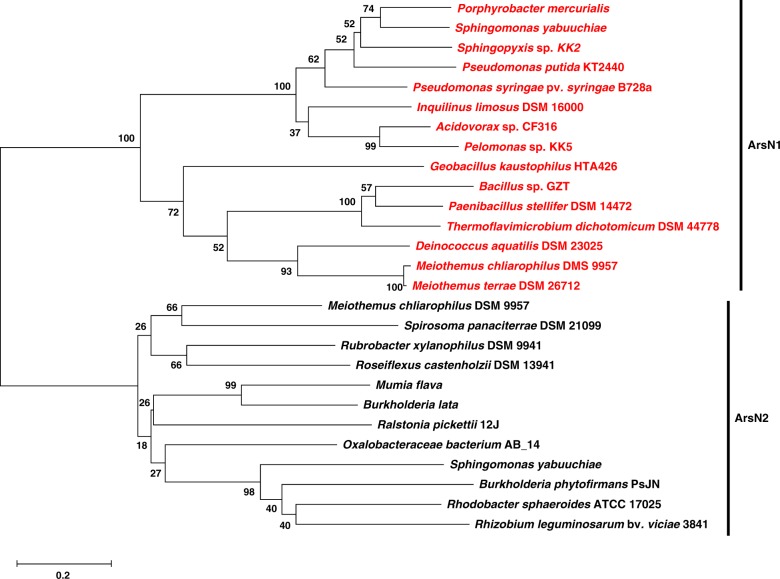

Fig. 4.

Phylogeny of arsN genes. The neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree shows evolutionary relationships. All arsN genes are located in ars operons. The genes are sorted into two clades, arsN1 (highlighted in red) and arsN2. Bootstrap values calculated for 1,000 subsets (%) are indicated on each branch. GenBank accession numbers of bacterial genomes are given in Methods. The scale bar represents 20% sequence dissimilarity

Fig. 5.

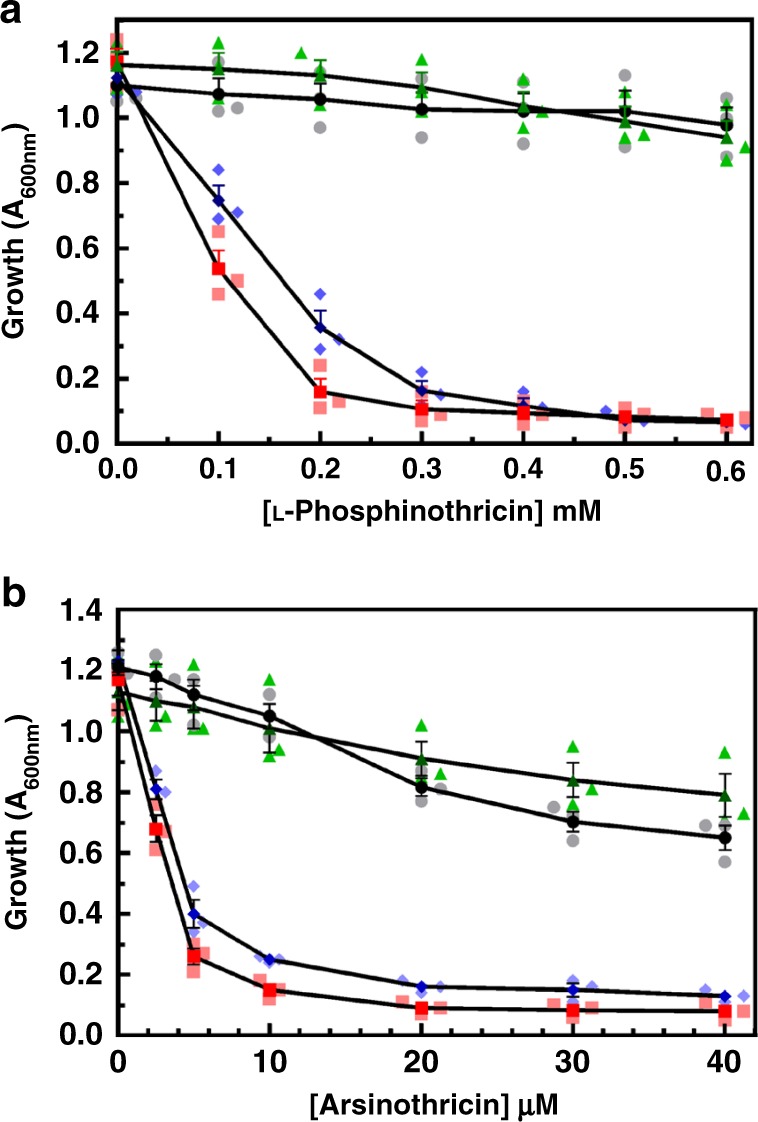

a PpArsN1 confers resistance to L-PPT (a) and AST (b). a Strains: wild type P. putida (circles); Δars1,2 (squares); E. coli AW3110 bearing vector plasmid (diamonds) or plasmid carrying PparsN1 (triangles). Cells were cultured in M9 medium with the indicated concentrations of L-PPT. Growth was estimated from A600nm after 24 h. Data are the mean ± SE (n = 3). Dark- and light-colored symbols represent means and individual data points, respectively. b Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of AST as in a. Data are the mean ± SE (n = 3). Dark- and light-colored symbols represent means and individual data points, respectively

To date every characterized ars gene has been shown to have an arsenic-related function, so it is unlikely that the primary function of PpArsN1 is PPT resistance because PPT does not contain arsenic. The prevalence of arsN genes in multiple ars operons implies involvement in arsenic metabolism. It was logical to propose that AST is the primary substrate of ArsN1. Parental P. putida is resistant to AST, while P. putida Δars1,2 is sensitive (Fig. 5b). E. coli AW3110 is similarly sensitive to AST, and heterologous expression of PparsN1 confers resistance. These results support our hypothesis that ArsN1 has the arsenic-related function of AST resistance. Comparing the effect of L-PPT with AST, both P. putida Δars1,2 and E. coli AW3110 show nearly complete inhibition of growth by 20 μM AST, with 50% inhibition at ~3 μM AST. In contrast, 100 μM L-PPT was required to give 50% inhibition. The result indicates that AST is at least 30-fold more effective as an antibiotic compared with L-PPT.

PpArsN1 is an arsinothricin-selective N-acetyltransferase

Crude extracts of cells of P. putida expressing PparsN1 have been shown to acetylate PPT21. Here we demonstrate that purified PpArsN1 exhibits phosphinothricin acetyltransferase activity (Table 1). The glutamine synthetase inhibitor L-MSO is a poorer substrate compared with AST (Fig. 1d). Purified PpArsN1 has 100-fold higher affinity for AST compared with L-PPT, and 15-fold higher catalytic efficiency (Kcat/Km), indicating that AST is the physiological substrate of PpArsN1. The affinity and catalytic efficiency of Streptomyces viridochromogenes phosphinothricin N-acetyltransferase (SvPAT) with AST are similar with those of PpArsN1. In contrast, SvPAT shows two orders of magnitude higher affinity for PPT than PpArsN1. Thus, while ArsN1 is selective for AST, SvPAT has similar affinity for both PPT and AST.

Table 1.

PpArsN1 is selective for L-AST over other glutamine synthetase inhibitors

| Substrate (50 μM) | Specific activity (nmol s−1 mg−1 PpArsN1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AST | 49.6 ± 0.8 | |||

| L-PPT | 13.9 ± 1.9 | |||

| L-MSO | 2.1 ± 0.1 | |||

| Enzyme | Substrate | Km (μM) | Kcat (s−1) | Kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PpArsN1 | AST | 11 ± 3 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1.55 × 105 |

| L-PPT | 1000 ± 200 | 9.6 ± 0.9 | 0.10 × 105 | |

| SvPAT | AST | 12 ± 2 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 1.92 × 105 |

| L-PPT | 47 ± 2 | 3.1 ± 0.0 | 0.66 × 105 |

Crystal structure of PpArsN1

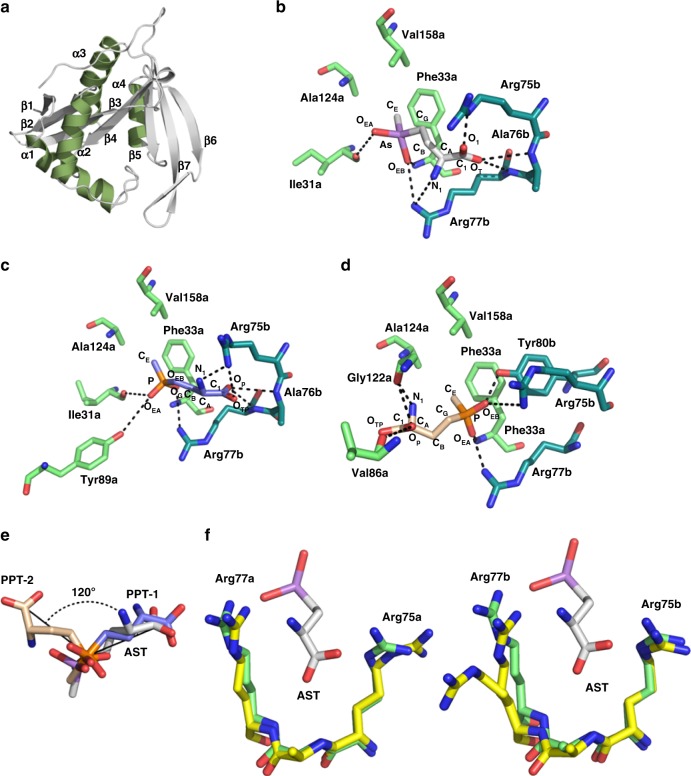

To elucidate the mechanism of PpArsN1 resistance and its selectivity for AST, we solved the structure of apo- and substrate-bound PpArsN1. The overall conformation is a three-layer α/β sandwich fold (Fig. 6a), a typical GCN5-related N-acetyltransferase fold22. PpArsN1 forms an asymmetric homodimer in solution, as shown by the extensive interactions of the subunits (Supplementary Figure 1) and size-exclusion chromatography (Supplementary Figure 2), similar to related N-acetyltransferases. The AST-bound PpArsN structure shows that the L-enantiomer is the substrate of the N-acetyltransferase, which supports our assumption that L-AST is the active form of the antibiotic (Supplementary Figure 3). PpArsN1 has two L-AST-binding sites, which are asymmetrically formed by amino acid residues from both Chains A and B. Both binding sites are composed of seven residues: four residues from Chain A (Ile31a, Phe33a, Ala124a and Val158a) (Fig. 6b, green) and three residues from Chain B (Arg75b, Ala76b and Arg77b) (Fig. 6b, teal). L-PPT is bound in two conformations. In one conformation (PPT-1) (Fig. 6c), the orientation of L-PPT is similar to that of L-AST (Fig. 6b), although the sets of amino acid residues used by PpArsN1 to interact with each chemical moiety in L-PPT are slightly different from those that interact with the corresponding chemical moiety in L-AST. In these structures, the predicted distance between the α-amino group of AST/PPT and the sulfur atom of acetyl coenzyme A (AcCoA) is too long to initiate acetylation (Supplementary Figure 4). Another conformation of L-PPT (PPT-2) (Fig. 6d) is similar to that of L-PPT observed in the previously reported coenzyme A- and L-PPT-bound ShPAT (PAT from Streptomyces hygroscopicus, also known as BAR)23. Superimposition of these two conformations of L-PPT-bound PpArsN1 demonstrates the two different binding modes of substrates in PpArsN1 (Fig. 6e). The arsenic atom of L-AST closely overlaps the phosphorus atom in PPT-1 and PPT-2. The orientation of PPT-1 is almost superimposable with that of L-AST. In contrast, the orientation of PPT-2 is inclined at 120° towards the AcCoA binding site with respect to those of PPT-1 and L-AST. This brings the α-amino group of L-PPT closer to the sulfur atom of AcCoA (Supplementary Figure 4), which is more favorable for catalysis. Arg75a in Chain A of the apo-structure also shows two conformations. One superimposes with the L-AST-bound PpArsN1 structure, covering the substrate-binding channel, whereas the other moves out of channel (Fig. 6f). The side chain of Arg77b in Chain B also appears to cover and move away from the substrate-binding site, allowing substrate access to the active site. The two conformations of this residue in L-PPT-bound PpArsN1, for both PPT-1 and PPT-2, are quite similar to those in L-AST-bound PpArsN1 (Supplementary Figure 5). Arg75 and Arg77 from each subunit appear to form gates that controls substrate access to both catalytic sites.

Fig. 6.

Structure of PpArsN1. a Overall fold of apo-PpArsN1. α helices are shown in green. Helices α1, α2 and α3, α4 are in the outer layers, and the seven β strands are in the inner layer of the sandwich. There is a structurally-conserved β bulge in the middle of the strands. b Interaction of L-AST with PpArsN1. The AST binding site is formed by residues from both chains. Arg75b, Ala76b and Arg77b (teal) of Chain B project into the AST binding site of Chain A, Ile31a, Phe33a, Ala124a and Val158a (green). Distances between polar atoms are less than 4.0 Å (dotted lines). CE of L-AST is surrounded by Phe33a, Ala124a and Val158a. OEA and OEB of L-AST interact with Ile31a and with Arg77b and Phe33a, respectively. O1 and OT of L-AST interact with Arg75b and with Arg77b and Ala76b, respectively. N1 of AST coordinates with Arg77b. c Interaction of PPT-1 (conformation 1) with PpArsN1. PPT-1 interacts with PpArsN1 in a way similar to AST with additional interactions: 1) the OEA atom with Ile31a and Tyr89a; and 2) the amino group with Arg75b. d Interaction of PPT-2 (conformation 2) with PpArsN1. CE of PPT is surrounded by Phe33a, Ala124a and Val158a. The atom OEA interacts with Arg77b. The OEB atom interacts with Arg75b, Tyr80b and Phe33a. The atom OP interacts with Val86a and Gly122a. The amino group interacts with Gly122a. e Orientation of L-AST and L-PPT. When the As atom of L-AST and the P atoms of PPT-1 and PPT-2 are superimposed, the carboxylates of PPT-2 and L-AST are oriented 120° relative to each other, and the carboxylates of PPT-1 and AST are oriented in the same direction. f A conformational change of PpArsN1 resulting from ligand binding. A portion of the AST binding site in PpArsN1-AST (green) is superimposed with that of the apo structure (yellow). Left and right cartoons depict Chain A and Chain B, respectively. Arg75a in Chain A and Arg77b in Chain B are closer to L-AST when substrate is bound

Discussion

Arsenic is the most ubiquitous environmental poison, and its toxicity presented a challenge to the first organisms1. Arsenic is and always has been the most prevalent toxic substance in surface and subsurface waters and soil. To adapt to high arsenic concentrations in primordial waters, microbes evolved arsenic detoxification mechanisms more than 2.5 billion years ago24. In addition, microbes developed mechanisms to use arsenic for energy production25. So it is not unexpected that bacteria would evolve pathways to use arsenic as an antibiotic to give them a selective growth advantage over competitors26. Here we identify the organoarsenical AST as a novel natural product with broad-spectrum antibiotic properties synthesized by an environmental isolate of Burkhoderia. Although the pathway of AST synthesis is not known, the biosynthetic pathway of phosphinothricin consists of more than twenty genes27, which suggests that the pathway for AST synthesis will prove to be correspondingly complicated.

As Paul Ehrlich, who synthesized the antimicrobial organoarsenical salvarsan, predicted, drug resistance follows the drug like a faithful shadow28. The arsN1 gene encodes an N-acetyltransferase that confers resistance to arsinothricin with high selectivity over the related antibiotic phosphinothricin. The arsN1 gene is present in many species of soil bacteria, which implies that AST is synthesized by other members of microbial communities, and that AST will be found to be present in soil and water with even moderate concentrations of arsenic. Indeed, we predict that the extensive distribution of arsN1 genes reflects an equally wide occurrence of AST producers, an eminently testable hypothesis.

We propose that the small difference in the As–O and P–O bond lengths allows L-AST to bind more tightly to PpArsN1 than L-PPT. Known differences between arsenic and phosphorus coordination are instructive. In arsenate the As–O bond length is 1.69 Å compared with a P–O bond length of 1.52 Å in phosphate29. In the periplasmic phosphate binding protein of Halomonas sp. GFAJ-1 this minute difference in bond length distorts a low-barrier H-bond and allows a 4500-fold selectivity for phosphate over arsenate30. L-AST and L-PPT differ from inorganic arsenate and phosphate in having C-As and C-P bonds replacing O–As and O–P bonds. In L-AST-bound PpArsN1, the bond lengths of As–CG, As–CE, As–OEA, As–OEB are 2.0, 1.9, 1.9 and 2.0 Å, respectively. In L-PPT, the bond lengths of P–CG, P–CE, P–OEA and P–OEB are 1.8, 1.8, 1.6 and 1.5 Å, respectively. Although small, these differences are critical for binding affinity. Both the arsenic atom in L-AST and the phosphorus atom in L-PPT are in a tetrahedral geometry with four coordinations. The volume of the L-AST tetrahedron is 3.00 Å3, compared with 1.86 Å3 for L-PPT. We predict that this substantial difference in substrate volume affects hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic and van der Waal contacts between the tetrahedral substrates and enzyme that accounts in part for the 100-fold higher affinity of ArsN1 for L-AST compared with L-PPT.

The high selectivity of PpArsN1 for AST suggests that arsN1 genes evolved in response to the environmental challenge presented by AST producers. The results of phylogenetic analysis suggest that ArsN1 genes can be further sorted into two subclades, with PAT and MAT branching off from both ArsN1 subclades (Supplementary Figure 6). This implies that ArsN1 is the common ancestor of those N-acetyltransferase members and that the arsenical antibiotic AST is the most ancient of this class of antimicrobials. Given that SvPAT has similar affinity for both PPT and AST (Table 1), we speculate that PAT homologs evolved from ArsN1 to increase affinity for PPT in response to PPT emergence without losing affinity for AST. The ten residues involved in L-PPT binding in ShPAT are conserved in SvPAT, while three are conservatively replaced in PpArsN1 (Supplementary Figure 7). These minor differences in amino acid residues involved in substrate-binding between ArsN1 and PAT may lead in part to the differences in their substrate selectivity. AST was only recently identified, so we might predict that other organoarsenical antibiotics exist. There are genes in ars operons for which functions have not been found; these might be resistance mechanisms against unknown natural products containing arsenic.

One concern is that ArsN1 resistance to AST could be a limiting factor for future clinical use. However, the effectiveness of AST could be extended if it could be used in combination with ArsN1 inhibitors31,32. To this end, analysis of the structure of ArsN1 is enlightening. Given the shorter distance between the amino group of PPT and the acetyl group of AcCoA in the PPT-2 conformation compared with the longer distance in the PPT-1 conformation (Supplementary Figure 4), it is reasonable to propose that PPT-2, and not PPT-1, is a conformation that the enzyme assumes during catalysis. The logical next question is why L-PPT binds to PpArsN1 in both the PPT-1 and the PPT-2 conformations. The α-amino group of L-PPT must be deprotonated for acetylation to occur. In ShPAT, like the other GCN5-related N-acetyltransferases, a conserved catalytic Glu88 acts as a general base, interacting with the α-amino group of L-PPT via a water molecule. The enzyme then uses the water molecule as the proton shuttle to catalyze the deprotonation step23. In PpArsN1, however, the residue corresponding to Glu88 of ShPAT is Asp85 (Supplementary Figure 7). The side chain of Asp85 is not long enough to catalyze deprotonation of the α-amino group of L-PPT in the PPT-2 conformation. In that conformation, no water molecule interactions were found between the α-amino group of L-PPT and Asp85 of PpArsN1 (Supplementary Figure 8a, 9.7 Å). In contrast, in the PPT-1 conformation, the distance between the α-amino group of L-PPT and Asp85 is shorter (Supplementary Figure 8a, 4.9 Å), allowing Asp85 to form a coordination with the amino group of L-PPT via a water molecule. This suggests that substrate deprotonation is catalyzed by Asp85 in the PPT-1 conformation. A similar water molecule bridge was also observed between AST and Asp85 in AST-bound PpArsN1 (Supplementary Figure 8b). Based on these results, we propose that PpArsN1 has two separate sites for substrate deprotonation and acetylation. In this hypothesis, PpArsN1 first captures the substrate in the deprotonation site, as seen in the PPT-1 conformation (Fig. 6c), where the α-amino group of the substrate is deprotonated by Asp85 (Supplementary Figure 8a). The deprotonated substrate then relocates to the acetylation site, as seen in the PPT-2 conformation (Fig. 6d), where the distance between the deprotonated substrate to AcCoA is shorter (Supplementary Figure 4). This allows nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl bond of the acetyl group, promoting catalysis. Based on structural analysis, a similar mechanism that uses separate sites for deprotonation and acetylation of substrate has been proposed for l-glutamate N-acetyltransferase from M. tuberculosis33. A unique feature that differentiates PpArsN1 from ShPAT is that the latter utilizes a common site for both deprotonation and acetylation of the substrate23.

With such knowledge obtained through our study, it may be possible to develop ArsN1 inhibitors that can be used in combination with AST to prevent resistance. In addition, from the structure of the binding site, we can rationally propose syntheses of more potent AST derivatives that bind to glutamine synthetase with higher affinity or bind to ArsN1 with lower affinity. In summary, we predict that AST may be the progenitor of a new class of antibiotics.

Methods

Reagents

All reagents and enzymes were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC (St. Louis, MO, USA), unless otherwise stated. Arsinothricin (AST) was purified from cultures of B. gladioli GSRB05, as described previously10. The concentration and purity of purified AST were determined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ELAN DRC-e; Perkin–Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) and high pressure liquid chromatography (series 2000, Perkin–Elmer) coupled to inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. AST is assumed to be the L-enantiomeric form based on the ArsN1 crystal structure with bound L-AST (vide infra). Commercial phosphinothricin (PPT) and methionine S-sulfoximine (MSO) are the D,L- and L-enantiomers, respectively. In the studies described below the concentration of D,L-PPT was divided by a factor of 2 to give the concentration of the L-enantiomer, the active form of the antibiotic13. Methylarsonous acid (MAs(III)) was prepared as described previously34.

Bacterial strains

Escherichia coli strains DH5α (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and TOP10 (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) were used for gene cloning and protein expression, respectively. E. coli strain W311035 and the ars operon deleted derivative AW3110 (Δars)36, Pseudomonas putida KT2440 and the double ars operon deleted derivative strain (Δars1,2)21, Burkholderia gladioli GSRB059, Shinorhizobium meliloti Rm102137, Shewanella putrefaciens 200, Bacillus cereus UW8538, Bacillus megaterium (ATCC 14581), Corynebacterium glutamicum (ATCC 13032), Enterobacter cloacae (ATCC BAA-2341) and Mycobacterium bovis BCG (ATCC 19274) were used for in vivo resistance assay.

Cloning, expression and protein purification

For gene cloning and protein expression, E. coli cells were grown at 37 °C in lysogeny broth (LB) medium39 supplemented with 0.1 mg/ml ampicillin. For construction of a plasmid for expression of arsN1 from P. putida KT2440 (PparsN1) (accession number: AAN67541.1) in fusion with a six histidine tag at C-terminus, a 558-bp fragment excluding the stop codon was PCR-amplified from total genomic DNA of P. putida KT2440 by high fidelity PfuTurbo DNA polymerase (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) using the forward primer 5′-CCAGCCATGGATAGCGGAATCGATATTCG-3′ (NcoI site underlined) and reverse primer 5′-CCAGAAGCTTACGAGGCACTGGGATTTGG-3′ (HindIII site underlined) and then ligated into pBAD-Myc/His-A as an NcoI/HindIII digest, generating the plasmid pBAD-PparsN1. The DNA sequence for pat, the gene encoding phosphinothricin N-acetyltransferase from Streptomyces viridochromogenes (Svpat) (accession number: AAU00088.1) with six histidine codons inserted at the 3’ end before the stop codon, was chemically synthesized by GenScript (NJ, USA) with 5′ NcoI and 3’ HindIII sites and cloned into the EcoRV site of pUC57-Kan (pUC57-Kan-Svpat). The synthetic Svpat gene was cloned as an NcoI/HindIII digest from pUC57-Kan-Svpat into pBAD-Myc/His-A, generating plasmid pBAD-Svpat. Cells of E. coli TOP10 bearing pBAD-PparsN1 or pBAD-Svpat were grown in LB medium with shaking at 37 °C. At an A600nm of 0.5–0.6, L-arabinose was added as an inducer at a final concentration of 0.2% (w/v). After 5 h, the cells were harvested and stored at −80 °C until use. The frozen cells were thawed and washed once with and resuspended in buffer A (50 mM morpholinopropane-1-sulfonic acid, pH 7.5, containing 20 mM imidazole, 0.5 M NaCl and 20% (v/v) glycerol) (5 ml per gram of wet cells). The cells were lysed by a one-time passage through a French pressure cell at 20,000 psi and immediately mixed with 2.5 µl per g of wet cell of diisopropylfluorophosphate. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 40,000 rpm using a T865 rotor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 60 min at 4 °C. The supernatant solution was applied onto a Ni-NTA column (QIAGEN Sciences, Hilden, Germany) at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min and washed with 20 column volumes (100 ml) of buffer A. Bound protein was eluted with buffer A containing 0.2 M imidazole, and the purity was assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis40. Protein concentrations were estimated by the Bradford assay by using bovine serum albumin as a standard. Fractions containing the protein were pooled and concentrated using a 10 kDa Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The concentrated protein was rapidly frozen and stored at −80 °C until use.

Glutamine synthetase assays

The activity of glutamine synthetase from E. coli was measured using a coupled assay that determines formation of the product ADP to oxidization of NADH41. The 1 ml reaction mixture contained 34 mM imidazole, 9 mM ATP, 1 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, 60 mM magnesium chloride, 19 mM potassium chloride, 45 mM ammonium chloride, 0.25 mM NADH, 13 to 20 units of l-lactic dehydrogenase and 8–14 units of pyruvate kinase. The reaction was initiated by addition of glutamine synthetase at 0.2 nM, final concentration. The decrease in A340nm was measured at 37 °C, and oxidation of NADH to NAD+ was quantified using an extinction coefficient 6230 M−1cm−1. The assays were performed with concentrations of l-glutamate from 2 to 100 mM. Inhibition constants (Ki) for AST and L-PPT were determined from the apparent Km of glutamine synthetase calculated with three different concentrations of inhibitor. Activities were corrected with the values from control assays without enzyme. Kinetic constants were calculated using Sigma Plot (Systat Software, Inc., Sun Jose, CA).

N-acetyltransferase assays

The enzymatic activity of purified PpArsN1 was measured from the rate of 5,5’-dithio-bis-2-nitrobenzoic acid reduction as described previously with minor modifications42. The reactions were carried out in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.33 mM 5,5′-dithio-bis-2-nitrobenzoic acid, 0.2 mM acetyl coenzyme A (AcCoA) with 50 µM AST, PPT or MSO at 37 °C. The reactions were initiated by addition of AcCoA, and the linear increase in A412nm was measured over the first 2 min. The specific activity was determined using the molar extinction coefficient of 2-nitro-5-benzoatic acid (14,150 M−1 cm−1)42. Activities were corrected with the values from control assays without enzyme. The kinetics of PpArsN1 and SvPAT for PPT and AST were determined over a concentration range between 1 µM and 2 mM using 0.2 µM enzyme. Kinetic constants were calculated from a fit of the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation43 using SigmaPlot.

Bacterial-resistance assays

Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco Laboratories Inc., Detroit, MI, USA) supplemented with 5 g bovine serum albumin, 2 g dextrose, 0.85 g NaCl and 0.05% tween 80 (Fisher Scientific International Inc., Pittsburg, PA, USA) was used to culture M. bovis BCG. Mycobacterial cells were inoculated at a density of 1.0 × 105 CFU/ml and horizontally cultured in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of AST, L-PPT or L-MSO in an incubator humidified at 37 °C under 5% CO2 for up to 4 weeks. Viable cells in each culture were determined by A600nm. All other bacterial strains were grown in LB medium overnight, following which the cells were centrifuged, washed with and resuspended in M9 medium39 to an A600nm of 0.04−0.06, with or without the indicated concentrations of As(III), MAs(III), AST, L-PPT or L-MSO. M9 medium was supplemented with 0.2% (w/v) citrate and 20 µg/ml uracil for P. putida strains, while M9 medium supplemented with 0.2% (w/v) glucose was used for the other bacterial strains. 0.1 mg/ml ampicillin and 0.2% (w/v) arabinose as inducer were added to cultures of E. coli, as required. Resistance was determined from the A600nm after 24 h. E. coli and B. megaterium were grown at 37 °C. Other bacterial strains were cultured at 30 °C.

Cytotoxicity assays

Human acute monocytic leukemia THP-1 cells (ATCC TIB-202TM) were seeded in a 24-well plate (Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, NY, USA) with 300 µl of RPMI-1640 medium (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethaol at a density of 1.0 × 105 cells/well and cultured in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator at 37 °C. After 24 h, THP-1 cells were further cultured in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of AST or As(III) for another 24 h, following which viability of cells was determined by a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl) 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay44. 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl) 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide was added to each well at a final concentration of 0.5 mM and the cultures were incubated for 3 h. The plate was then centrifuged at 400 × g, the cell pellets were lysed with 300 µl of dimethyl sulfoxide to dissolve 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl) 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide formazan. Cell viability was estimated from A570nm.

ArsN distribution and phylogenetic analysis

The prevalence of arsN (arsN1 and arsN2, see Results) genes in ars operons was analyzed in representative organisms. GenBank accession numbers of the following bacterial genomes are given in parentheses. P. putida KT2440 (AE015451), Bacillus sp. GZT (LVVJ00000000), Meiothermus chliarophilus DSM 9957 (AUQW00000000), Acidovorax sp. CF316 (AKJX00000000), Porphyrobacter mercurialis (JTDN00000000), Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae B728a (CP000075), Inquilinus limosus DSM 16000 (AUHM00000000), Sphingopyxis sp. KK2 (LYVN00000000), Sphingomonas yabuuchiae (LDTF00000000), Pelomonas sp. KK5 (LYVQ00000000), Burkholderia lata (CP000150), Rhodobacter sphaeroides ATCC17025 (CP000661), Rubrobacter xylaniophilus DSM 9941 (CP000386), Mumia flava (JTDJ00000000), Roseiflexus castenholzii DSM 13941 (CP000804), Ralstonia pickettii 12 J (AAWK00000000), Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae 3841 (AM236080), Burkholderia phytofirmans PsJN (AAUH00000000), Spirosoma panaciterrae DSM 21099 (ARFA00000000), Oxalobacteraceae bacterium AB_14 (ARMC00000000), Geobacillus kaustophilus HTA426 (BA000043), Paenibacillus stellifer DSM 14472 (NZ_CP009286), Thermoflavimicrobium dichotomicum DSM 44778 (NZ_FORR01000002), Deinococcus aquatilis DSM 23025 (NZ_KB899704), Meiothermus terrae DSM 26712 (NZ_QXDL01000023). Multiple alignment of the sequences of putative N-acetyltransferase orthologs was performed using T-Coffee45 and BoxShade46. N-acetyltransferase sequences distributed in ars operons20,21 were defined as ArsN [P. putida KT2440 (WP_010952945), Bacillus sp. GZT (WP_062922891), M. chliarophilus DSM 9957 (WP_027893731, WP_027893733), Acidovorax sp. CF316 (WP_007857208), P. mercurialis (WP_039093634), P. syringae pv. syringae B728a (YP_234588), I. limosus DSM 16000 (WP_026871525), Sphingopyxis sp. KK2 (WP_077145629), S. yabuuchiae (WP_058746515, WP_058746517), Pelomonas sp. KK5 (WP_077035561), B. lata (WP_011349260), R. sphaeroides ATCC 17025 (WP_011908437), R. xylanophilus DSM 9941 (WP_011565797), M. flava (KHL15495), R. castenholzii DSM 13941 (WP_012120818), R. pickettii 12 J (WP_012429982), R. leguminosarum bv. viciae 3841 (WP_011652407), B. phytofirmans PsJN (WP_012431288), S. panaciterrae DSM 21099 (WP_020601039) and O. bacterium AB_14 (WP_020703167), G. kaustophilus HTA426 (BAD74878), M. terrae DSM 26712 (WP_119314079), P. stellifer DSM 14472 (WP_038700913), T. dichotomicum DSM 44778 (WP_093227883) and D. aquatilis DSM 23025 (WP_019009361)]. N-acetyltransferase sequences distributed in phosphinothricin tripeptide biosynthesis gene clusters27 were defined as phosphinothricin N-acetyltransferase (PAT) [Streptomyces hygroscopicus (P16426), Streptomyces viridochromogenes (WP_003988626), Kitasatospora phosalacinea NRRL B-16230 (KP185121) and Actinobacteria bacterium OK074 (WP_082414639)]. N-acetyltransferases with higher selectivity for PPT compared to MSO47-49 are also defined as PAT [Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) (CAB90987), Rhodococcus sp. YM12 (JQ398613) and Nocardia sp. AB2253 (BAG06876)]. N-acetyltransferases with higher selectivity on MSO compared to PPT21,47,50,51 are defined as methionine sulfoximine N-acetyltransferase (MAT) [E. coli K-12 (AAC74530), Salmonella enterica Typhimurium str. LT2 (NP_460549), P. putida KT2440 (WP_010955452) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (AAG08251), Acinetobacter sp. ADP1 (Q6FBS8)]. N-acetyltransferases that have similar activity on both PPT and MSO47 are also included [Geobacillus kaustophilus HTA426 (BAD77205), Bacillus subtilis RO-NN-1 (AEP92705), Paraburkholderia xenovorans LB400 (ABE30708, ABE34181), Staphylococcus aureus USA300_FPR3757 (ABD22256) and Deinococcus radiodurans R1 (AAF10750)]. GenBank accession numbers of N-acetyltransferase orthologs are given in parentheses. Phylogenetic analysis was performed to infer the evolutionary relationship among the sequences of ArsN1, PAT and/or MAT from various organisms. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Neighbor-Joining method using MEGA X52. The statistical significance of the branch pattern was estimated from a 1000 bootstrap53.

Crystallization and structure determination

Initial crystallization screening was performed as described previously54 by the sitting-drop vapor-diffusion method55 using a variety of crystal screens from Hampton Research (Aliso Viejo, CA, USA), Emerald BioSystems, Inc. (Bainbridge Island, WA, USA) and Jena Bioscience GmbH (Jena, Germany) in 96-well plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) at 293 K. Crystalline precipitates were obtained at 0.2 M sodium acetate, 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, and 30% (w/v) PEG 4000. Diffraction quality crystals were grown using the vapor diffusion hanging drop method in 24-well Linbro plates. The reservoir solution (0.3 ml) consisted of 0.2 M sodium acetate, 0.1 M Tris-HCl and 20% (w/v) PEG 6000, and the hanging drop contained 2 µl of 20 mg/ml of purified PpArsN1, 2 µl reservoir solution and 1 µl of 0.1 M ATP. Rod-shaped crystals, with approximate dimensions of 0.1 × 0.05 × 0.05 mm, were obtained within a few weeks. The PpArsN1-AST complex was prepared by adding 0.5 ml of 4.0 mM AST to 0.5 ml of 1 mM protein. PpArsN1-AST crystals were grown using vapor diffusion hanging drop method. The hanging drop contained 2 µl of PpArsN1-AST complex and 2 µl of reservoir solution. The reservoir contained 1.5 M sodium formate and 0.1 M sodium acetate with pH 4.5. Thin plate-like crystals were obtained within a week. The PpArsN1-PPT complex was prepared by adding 0.5 ml of 25 mM L-PPT to 0.5 ml of 1 mM protein. The PpArsN1-PPT crystals were also grown using the same method and crystallization condition as used for the PpArsN1-AST crystals. The crystals were harvested from the hanging drop using a cryoLoop, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen at 100 K and stored in liquid nitrogen. Ethylene glycol (20%, v/v) was used as cryoprotectant. X-ray data were collected on beamline 22ID at the Advanced Photon Source), Argonne National Laboratory, using a MAR300HS detector. The crystal-to-detector distance was 180 mm, and 180 images for PpArsN1 crystal, 240 and 360 images for PpArsN1-AST and PpArsN1-PPT crystals, respectively, were collected with 1° oscillations. The PpArsN1 diffraction data were indexed and scaled using KYLIN56 and PpArsN1-AST and PpArsN1-PPT data were indexed and scaled using HKL200057. The data processing statistics are shown in Table 2. The PpArsN1 crystal diffracted to 2.16 Å resolution. The crystal belongs to space group P43212 with cell dimensions a = b = 67.02 Å, c = 206.74 Å. The Matthews coefficient of 2.48 indicates that there are two molecules in the asymmetric unit with 50.5% solvent. An initial homology model was constructed by molecular replacement with an acetyltransferase from P. aeruginosa PA01 (PDB ID: 1YVO as a template with 32.3 % identity) using SWISS-MODEL58. Molecular replacement was done using PHASER59 in the CCP4 suite60. The initial R and Rfree were 35.0 and 40.0%, respectively. The structure was refined using PHENIX61. The C-terminal extended residues were fitted in electron density using COOT62. Water molecules were added at appropriate positions and refined. The final R and Rfree are 23.7% and 26.6%, respectively. The PpArsN1-AST crystal diffracted to 2.19 Å resolution and indexed with C121 space group with cell dimensions a = 185.27, b = 141.74, c = 54.55 Å and β = 90.6°. The Matthews coefficient of 2.54 indicates that there are six molecules in the asymmetric unit with 51.6% solvent. The PpArsN1-apo structure was used as a model for molecular replacement. There are positive electron densities at the 9.0 and 16.0 σ level near Arg77 in molecule A and B, respectively (Supplementary Figure 9). The density was fitted with the L-enantiomer of AST, and the anomalous difference map confirmed the presence of arsenic. The PpArsN1-PPT crystal diffracted to 2.66 Å resolution and indexed with P1211 space group with cell dimensions a = 53.84, b = 142.69, c = 178.31 Å and β = 89.9°. The Matthews coefficient of 2.45 indicates that there are twelve molecules in the asymmetric unit with 49.8% solvent. The PpArsN1-apo structure was used as model for molecular replacement. There are positive electron densities between 6.5 and 9.0 σ level near Arg77 in molecule A–D, G–J (Supplementary Figure 10). The density was fitted with two L-PPT molecules. The structure were refined using REFMAC563 in the CCP4 suite60. The simulated annealing refinement was done using PHENIX. The structure factor and coordinates were deposited to the Worldwide Protein Data Bank (wwPDB, accession IDs: 5JTF (PpArsN1), 5WPH (PpArsN1-AST) and 6M7G (PpArsN1-PPT)). The molecules were drawn with PyMol (Version 1.8 Schrödinger, LLC). Docking was performed using AutoDockTools and AutoDock464.

Table 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| PpArsN1a | PpArsN1-ASTa | PpArsN1-PPTa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||

| Space group | P43212 | C121 | P1211 |

| Cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c (Å) | 67.02, 67.02, 206.74 | 185.27, 141.74, 54.55 | 53.84, 142.69, 178.31 |

| α, β, ϒ (°) | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 | 90.0, 90.6, 90.0 | 90, 89.9, 90.0 |

| Resolution (Å) | 30.64–2.16 (2.20–2.16)b | 50.00–2.19 (2.23–2.19)b | 39.91–2.66 (2.75–2.66)b |

| R merge | 0.078 (0.342)b | 0.150 (0.654)b | 0.157 (1.144)b |

| I/ σ I | 6.9 (2.9)b | 12.4 (1.9)b | 11.0 (1.9)b |

| Completeness (%) | 97.6 (90.8)b | 99.4 (95.7)b | 97.0 (97.2)b |

| Redundancy | 5.16 (4.31)b | 7.3 (4.4)b | 4.2 (3.9)b |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution (Å) | 30.64–2.16 (2.24–2.16)b | 49.02–2.19 (2.24–2.19)b | 39.91–2.66 (2.69–2.66)b |

| No. of reflections | 25,795 | 67,549 | 70,774 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.237/0.266 | 0.180/0.232 | 0.224/0.272 |

| No. of atoms | |||

| Protein | 2681 | 8443 | 15,829 |

| Ligand/ion | - | 26 | 89 |

| Water | 104 | 874 | 222 |

| B-factors | |||

| Protein | 34.95 | 29.97 | 39.49 |

| Ligand/ion | - | 41.66 | 55.00 |

| Water | 38.10 | 35.12 | 37.89 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.004 | 0.013 | 0.004 |

| Bond angles (˚) | 0.905 | 1.477 | 0.880 |

aEach structure was refined from a single data set from an independent protein crystal

bValues in parentheses are for highest resolution shell

Statistics

Assays of glutamine synthetase, N-acetyltransferase, bacterial resistance and cytotoxicity were repeated at least three times. The data are presented as the mean ± standard error (SE). No other statistical tests were performed.

Reporting summary

Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH R01 grants GM055425 and ES023779 to BPR, NSF BIO/MCB Grant 1817962 and a pilot project grant from the Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine (Project #800008403) to MY, and a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI grant (no. 23380044) to SI. This project utilized the Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT) 22-ID beamline of the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under contract No. W-31–109-Eng-38. The Berkeley Center for Structural Biology is supported in part by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The Advanced Light Source is a Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. The ALS-ENABLE beamlines are supported in part by the NIH, NIGMS, grant P30 GM124169.

Author contributions

B.P.R. and M.Y. conceived of and designed the experiments and supervised the overall project. V.S.N., J.C., D.S.D., B.P.R. and M.Y. wrote the paper. V.S.N., D.S.D. and M.Y. purified PpArsN1 and SvPAT and characterized their biochemical properties. V.S.N. crystallized PpArsN1 and solved its structure. P.K. and B.S. collected X-ray crystallographic data. M.K. and S.I. initially supplied arsinothricin and advice. J.C. and A.D.G. subsequently purified arsinothricin and conducted assays of bacterial AST sensitivity. K.Y.S. conducted the toxicity assays with human cells.

Data availability

Protein structural data have been deposited in the wwPDB under accession IDs 5JTF (PpArsN1), 5WPH (PpArsN1-AST) and 6M7G (PpArsN1-PPT). The source data used to generate the Figs. 2 and 5 are presented as Supplementary Data 1. Other data that support the findings of the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors have the following competing interest: Florida International University has applied for a US Non-Provisional patent application for “Arsinothricin and Methods of Treating Infections Using Arsinothricin” (US 16/163,055) with M.Y. and B.P.R. as inventors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Venkadesh Sarkarai Nadar, Jian Chen, Dharmendra S. Dheeman.

Contributor Information

Barry P. Rosen, Email: brosen@fiu.edu

Masafumi Yoshinaga, Email: myoshina@fiu.edu.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s42003-019-0365-y.

References

- 1.Zhu YG, Yoshinaga M, Zhao FJ, Rosen BP. Earth abides arsenic biotransformations. Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 2014;42:443–467. doi: 10.1146/annurev-earth-060313-054942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2017https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/gtbr2017_main_text.pdf. (2017).

- 3.World Health Organization. Prioritization of Pathogens to Guide Discovery, Research and Development of New Antibiotics for Drug Resistant Bacterial Infections, Including Tuberculosishttps://www.who.int/medicines/areas/rational_use/PPLreport_2017_09_19.pdf. (2017).

- 4.World Health Organization. WHO Publishes List of Bacteria for Which New Antibiotics are Urgently Neededhttp://www.who.int/en/news-room/detail/27-02-2017-who-publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed. (2017).

- 5.Jolliffe DM. A history of the use of arsenicals in man. J. R. Soc. Med. 1993;86:287–289. doi: 10.1177/014107689308600515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan C, Liu G, Long Y, Rosen B, Cai Y. Thiolation in arsenic metabolism: a chemical perspective. Metallomics. 2018;17:1368–1382. doi: 10.1039/C8MT00231B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brun R, Blum J, Chappuis F, Burri C. Human African trypanosomiasis. Lancet. 2010;375:148–159. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60829-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mangalgiri KP, Adak A, Blaney L. Organoarsenicals in poultry litter: detection, fate, and toxicity. Environ. Int. 2015;75:68–80. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Z, Chen SJ. Poisoning the devil. Cell. 2017;168:556–560. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuramata M, et al. Arsinothricin, a novel organoarsenic species produced by a rice rhizosphere bacterium. Environ. Chem. 2016;13:723–731. doi: 10.1071/EN14247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Styblo M, et al. Comparative toxicity of trivalent and pentavalent inorganic and methylated arsenicals in rat and human cells. Arch. Toxicol. 2000;74:289–299. doi: 10.1007/s002040000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berlicki Ł, Obojska A, Forlani G, Kafarski P. Design, synthesis, and activity of analogues of phosphinothricin as inhibitors of glutamine synthetase. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:6340–6349. doi: 10.1021/jm050474e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drsge W, Broer I, Piihler A. Transgenic plants containing the phosphinothricin-N-acetyltransferase gene metabolize the herbicide L-phosphinothricin (glufosinate) differently from untransformed plants. Planta. 1992;187:142–151. doi: 10.1007/BF00201636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mowbray S, Kathiravan M, Pandey A, Odell L. Inhibition of glutamine synthetase: a potential drug target in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Molecules. 2014;19:13161–13176. doi: 10.3390/molecules190913161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harth G, Horwitz MA. An inhibitor of exported Mycobacterium tuberculosis glutamine synthetase selectively blocks the growth of pathogenic mycobacteria in axenic culture and in human monocytes: extracellular proteins as potential novel drug targets. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:1425–1436. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.9.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bentley HR, McDermott EE, Pace J, Whitehead JK, Moran T. Action of nitrogen trichloride (‘agene’) on proteins: Isolation of crystalline toxic factor. Nature. 1949;164:438–439. doi: 10.1038/164438a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harth G, Horwitz MA. Inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis glutamine synthetase as a novel antibiotic strategy against tuberculosis: Demonstration of efficacy in vivo. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:456–464. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.1.456-464.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Metcalf WW, van der Donk WA. Biosynthesis of phosphonic and phosphinic acid natural products. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:65–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.091707.100215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie L, Zeng J, Luo H, Pan W, Xie J. The roles of bacterial GCN5-related N-acetyltransferases. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2014;24:77–87. doi: 10.1615/CritRevEukaryotGeneExpr.2014007988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chauhan NS, Ranjan R, Purohit HJ, Kalia VC, Sharma R. Identification of genes conferring arsenic resistance to Escherichia coli from an effluent treatment plant sludge metagenomic library. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2009;67:130–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Páez-Espino AD, Chavarría M, de Lorenzo V. The two paralogue phoN (phosphinothricin acetyl transferase) genes of Pseudomonas putida encode functionally different proteins. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;17:3330–3340. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vetting MW, et al. Structure and functions of the GNAT superfamily of acetyltransferases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005;433:212–226. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christ B, et al. Non-specific activities of the major herbicide-resistance gene BAR. Nat. Plants. 2017;3:937–945. doi: 10.1038/s41477-017-0061-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen SC, et al. Recurrent horizontal transfer of arsenite methyltransferase genes facilitated adaptation of life to arsenic. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:7741. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08313-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Lis R, Nitschke W, Duval S, Schoepp-Cothenet B. Arsenics as bioenergetic substrates. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 2013;1827:176–188. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen J, Yoshinaga M, Rosen BP. The antibiotic action of methylarsenite is an emergent property of microbial communities. Mol. Microbiol. 2019;111:487–494. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blodgett JA, Zhang JK, Yu X, Metcalf WW. Conserved biosynthetic pathways for phosalacine, bialaphos and newly discovered phosphonic acid natural products. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 2015;69:15–25. doi: 10.1038/ja.2015.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheps JA, Ling V. Preface: the concept and consequences of multidrug resistance. Pflüg. Arch. - Eur. J. Physiol. 2007;453:545–553. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kish MM, Viola RE. Oxyanion specificity of aspartate-β-semialdehyde dehydrogenase. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:818–820. doi: 10.1021/ic981082j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elias M, et al. The molecular basis of phosphate discrimination in arsenate-rich environments. Nature. 2012;491:134–137. doi: 10.1038/nature11517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blondiaux N, et al. Reversion of antibiotic resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by spiroisoxazoline SMARt-420. Science. 2017;355:1206–1211. doi: 10.1126/science.aag1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee SH, et al. TarO-specific inhibitors of wall teichoic acid biosynthesis restore β-lactam efficacy against methicillin-resistant staphylococci. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016;8:329ra32–329ra32. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad7364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang, X. etal. Crystal structure of L-glutamate N-acetyltransferase ArgA from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteomics1865, 1800–1807 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Yoshinaga M, Rosen BP. A C-As lyase for degradation of environmental organoarsenical herbicides and animal husbandry growth promoters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:7701–7706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403057111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neidhardt FC. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: Cellular and Molecular Biology. Washington, D. C: American Society forMicrobiology; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carlin A, Shi W, Dey S, Rosen BP. The ars operon of Escherichia coli confers arsenical and antimonial resistance. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:981–986. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.4.981-986.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang HC, Cheng J, Finan TM, Rosen BP, Bhattacharjee H. Novel pathway for arsenic detoxification in the legume symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:6991–6997. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.20.6991-6997.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Handelsman J, Raffel S, Mester EH, Wunderlich L, Grau CR. Biological control of damping-off of alfalfa seedlings with Bacillus cereus UW85. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1990;56:713–718. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.3.713-718.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E. F. & Maniatis, T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York, 1989).

- 40.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wakisaka S, et al. A rapid assay method for ammonia using glutamine synthetase from glutamate-producing bacteria. Anal. Biochem. 1987;163:117–122. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thompson CJ, et al. Characterization of the herbicide-resistance gene bar from Streptomyces hygroscopicus. EMBO J. 1987;6:2519–2523. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson KA, Goody RS. The original Michaelis constant: Translation of the 1913 Michaelis–Menten Paper. Biochemistry. 2011;50:8264–8269. doi: 10.1021/bi201284u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Twentyman P, Luscombe M. A study of some variables in a tetrazolium dye (MTT) based assay for cell growth and chemosensitivity. Br. J. Cancer. 1987;56:279–285. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1987.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Notredame C, Higgins DG, Heringa J. T-Coffee: A novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J. Nol. Biol. 2000;302:205–217. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. BoxShade (version 3.21) from ExPASy Bioinformatics Resource Portalhttps://embnet.vital-it.ch/software/BOX_form.html. (2006).

- 47.VanDrisse CM, Hentchel KL, Escalante-Semerena JC. Phosphinothricin acetyltransferases identified using in vivo, in vitro, and bioinformatic analyses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016;82:7041–7051. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02604-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu G, et al. Characterization of a novel cold-adapted phosphinothricin N-acetyltransferase from the marine bacterium Rhodococcus sp. strain YM12. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2014;104:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2014.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yun CS, Hasegawa H, Nanamiya H, Terakawa T, Tozawa Y. Novel bacterial N-acetyltransferase gene for herbicide detoxification in land plants and selection maker in plant transformation. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2009;73:1000–1006. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davies AM, Tata R, Beavil RL, Sutton BJ, Brown PR. L-methionine sulfoximine, but not phosphinothricin, is a substrate for an acetyltransferase (gene PA4866) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Structural and functional studies. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1829–1839. doi: 10.1021/bi0615238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davies AM, Tata R, Snape A, Sutton BJ, Brown PR. Structure and substrate specificity of acetyltransferase ACIAD1637 from Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1. Biochimie. 2009;91:484–489. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35:1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nadar SV, Yoshinaga M, Kandavelu P, Sankaran B, Rosen BP. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic studies of the ArsI C–As lyase from Thermomonospora curvata. Acta Crystallogr. F. Struct. Biol. Commun. 2014;70 Part 6:761–764. doi: 10.1107/S2053230X14008814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McPherson A. Current approaches to macromolecular crystallization. Eur. J. Biochem. 1990;189:1–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fu ZQ. Three-dimensional model-free experimental error correction of protein crystal diffraction data with free-R test. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2005;61:1643–1648. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905033494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Otwinowski Z, Minor M. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276 part A:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McCoy AJ. Solving structures of protein complexes by molecular replacement with Phaser. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2007;63:32–41. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906045975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP 4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Afonine PV, et al. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2012;68:352–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912001308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vagin AA, et al. REFMAC 5 dictionary: Organization of prior chemical knowledge and guidelines for its use. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2184–2195. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904023510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morris GM, et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

Protein structural data have been deposited in the wwPDB under accession IDs 5JTF (PpArsN1), 5WPH (PpArsN1-AST) and 6M7G (PpArsN1-PPT). The source data used to generate the Figs. 2 and 5 are presented as Supplementary Data 1. Other data that support the findings of the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.