Abstract

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) results in a significant public health burden due to the morbidity caused by the disease and many of the available remedies. As much as 70% of men over 70 will develop BPH. Few studies have been conducted to discover the genetic determinants of BPH risk. Understanding the biological basis for this condition may provide necessary insight for development of novel pharmaceutical therapies or risk prediction. We have evaluated SNP-based heritability of BPH in two cohorts and conducted a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of BPH risk using 2,656 cases and 7,763 controls identified from the Electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE) network. SNP-based heritability estimates suggest that roughly 60% of the phenotypic variation in BPH is accounted for by genetic factors. We used logistic regression to model BPH risk as a function of principal components of ancestry, age, and imputed genotype data, with meta-analysis performed using METAL. The top result was on chromosome 22 in SYN3 at rs2710383 (p-value = 4.6 × 10−7; Odds Ratio = 0.69, 95% confidence interval = 0.55–0.83). Other suggestive signals were near genes GLGC, UNCA13, SORCS1 and between BTBD3 and SPTLC3. We also evaluated genetically-predicted gene expression in prostate tissue. The most significant result was with increasing predicted expression of ETV4 (chr17; p-value = 0.0015). Overexpression of this gene has been associated with poor prognosis in prostate cancer. In conclusion, although there were no genome-wide significant variants identified for BPH susceptibility, we present evidence supporting the heritability of this phenotype, have identified suggestive signals, and evaluated the association between BPH and genetically-predicted gene expression in prostate.

Introduction

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is characterized by an enlarged prostate that affects a moderate proportion of middle-aged men and a large proportion of elderly men and can result in significant discomfort and reproductive and urinary tract dysfunction1–4. Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are commonly attributed to BPH in the absence of other causes5–7. Very severe cases can result in urinary tract infections and bleeding, bladder stones, and kidney damage from failing to void7–10. Pharmaceutical treatments for BPH include alpha blockers to relax muscles and treat some LUTS symptoms, and 5-alpha reductase inhibitors which can shrink the prostate in some patients but may increase risk for prostate cancer11–16. Additionally, the available surgical remedies can present additional risks and have considerable potential consequences for reproductive and urinary tract health17–21.

Heritability of LUTS scores in twins has been estimated at 20–40%22, with some estimates as high as 83%23, while heritability of benign prostate disease has been estimated at 49% from twin studies24. The presence of racial disparities also supports a genetic contribution to BPH risk25,26. Evaluation of the SNP-based additive genetic heritability has not yet been published.

The genetic factors underlying BPH risk remain unclear. To date there have been many BPH candidate gene studies, often evaluating the effect of prostate cancer susceptibility variants, with mixed success27–47. Three larger-scale studies have been performed, a MetaboChip analysis of prostate volume48 and two recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of BPH49,50. In the present study, we evaluated genetic heritability of clinically reported BPH and conducted a GWAS using cases and controls identified from the Electronic Medical Records and Genomic (eMERGE) network, and evaluated the contribution of the genetic associations to gene expression in prostate tissue.

Results

Heritability

SNP-based additive heritability among common variants was assessed in the 5 sites of the eMERGE-1 network and one of the Geisinger datasets (CoreExome) as they had the largest number of cases assessed on a common genotyping array (Table 1). After stringent filters to remove residual population stratification, there were 755 cases and 899 controls included from eMERGE-1 and 423 cases and 1278 controls included from Geisinger CoreExome. Heritability results were consistent between the two groups, with an estimated heritability of 0.65 (±0.30) in eMERGE-1 (p-value = 0.011) and 0.56 (±0.38) in Geisinger (p-value = 0.070) (Table 2). Results were largely consistent across inclusion of increasing PCs (Supplementary Table 1). Results across chromosomes varied substantially (Supplementary Fig. 1), however, chromosomes 6 and 7 were present among the top 5 results for both eMERGE-1 and Geisinger, suggesting the likelihood of one or more BPH-susceptibility loci being located on these chromosomes.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics.

| Study Population | % White | Cases | Controls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean Age (Years)(SD) | N | Mean Age (Years)(SD) | ||

| eMERGE-1 | 94.8 | 912 | 67 (10) | 1,077 | 69 (13) |

| Geisinger (eMERGE-2) | 99.5 | 242 | 66 (8) | 807 | 61 (13) |

| Mayo (eMERGE-2) | 94.2 | 157 | 65 (9) | 1,166 | 62 (11) |

| Mt Sinai (eMERGE-2) | 15.9a | 283 | 64 (9) | 1,037 | 56 (10) |

| BioVU (eMERGE-2) | 100 | 156 | 65 (10) | 106 | 62 (12) |

| Harvard | 88.9 | 94 | 64 (10) | 943 | 60 (11) |

| Columbia | 30.4b | 34 | 73 (9) | 242 | 60 (7)c |

| Geisinger CoreExome | 99.4 | 574 | 66. (7) | 1,685 | 61 (9) |

| Mayo Clinic | 95.6d | 204 | 65 (7) | 700 | 63 (10) |

| TOTAL | 2,656 | 69 | 7,763 | 61 | |

aMt Sinai analyzed as 4 separate groups by race/ethnicity. bColumbia was a mixed sample, with many samples lacking reported race information. Excluded from whites-only analysis. cOnly 27 controls for Columbia had age information. dMayo Clinic was composed of 4 separate chip-sets, each one was >93% white.

Table 2.

SNP-based heritability of BPH in two cohorts.

| Cohort | N Cases/N Controls | h2 | SE | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eMERGE-1 | 755/899 | 0.65 | 0.30 | 0.011 |

| Geisinger CoreExome | 423/1278 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.070 |

Adjusted for age and PCs 1–5.

Genome-wide association

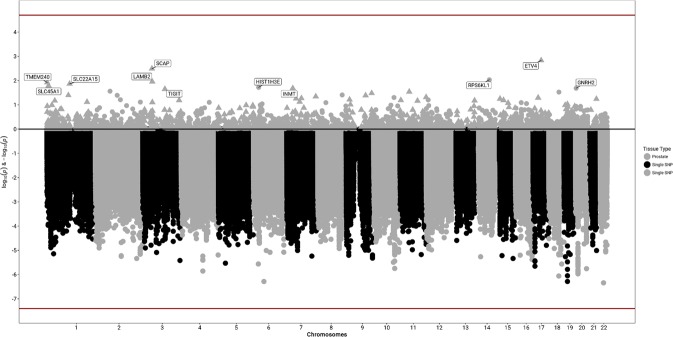

In total, 2,656 cases and 7,763 controls were included across eight eMERGE sites (including the data used in the heritability analysis; Table 1) for the analysis of common (minor allele frequency [MAF] > 0.05) genetic association at 10,973,920 SNPs. Overall, the samples were predominantly identified as white (85%) and cases were slightly older than controls (average age of 68.88 years in cases vs 61.45 years in controls). The most statistically significant results from single SNP GWAS analyses was on chromosome 22 in synpasin 3 (SYN3) at rs2710383 (allele frequency = 0.12, p-value = 4.56 × 10−7; Odds Ratio [OR] = 0.69, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.55–0.83; Table 3; Fig. 1). Other suggestive signals were within genes glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (GCLC; chromosome 6), unc-13 homolog A (UNC13A; chromosome 19), and ELOVL [elongation of very long chain fatty acids] fatty acid elongase 6 (ELOVL6; chromosome 4), near the long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 1919 (LINC01919; chromosome 18), and in an intergenic region on chromosome 20 between BTB domain containing 3 (BTBD3) and serine palmitoyltransferase long chain base subunit 3 (SPTLC3). Secondary analysis restricting to whites yielded consistent results for top SNPs (Table 3), but identified the top variants as rs10786938 in SORCS1 (p-value = 3.84 × 10−7, OR = 1.23; Supplementary Table 2).

Table 3.

Top GWAS Results.

| Lead rsID | CHR:BP (hg19) | Annotation | A1 | Freq. A1 | All Samples | Whites Only | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | HetPVal | P-value | OR | |||||

| rs2710383 | 22:32950969 | SYN3, intron | C | 0.12 | 0.69 (0.55–0.83) | 4.56 × 10−7 | 0.20 | 4.56 × 10−7 | 0.69 |

| rs534957 | 6:53406351 | GCLC, intron | C | 0.35 | 1.26 (1.17–1.36) | 5.17 × 10−7 | 0.29 | 4.78 × 10−6 | 1.24 |

| rs4239633 | 19:17742469 | UNC13A, intron | T | 0.31 | 0.80 (0.71–0.88) | 5.19 × 10−7 | 0.57 | 6.25 × 10−7 | 0.79 |

| rs141179786 | 18:51188544 | DCC, 126 kb downstream | A | 0.98 | 0.40 (0.04–0.77) | 8.72 × 10−7 | 0.72 | 8.72 × 10−7 | 0.40 |

| rs71162163 | 19:17744075 | UNC13A, intron | G | 0.69 | 1.25 (1.16–1.34) | 8.95 × 10−7 | 0.65 | 1.29 × 10−6 | 1.25 |

| rs6078585 | 20:12428260 | BTBD3 – SPTLC3 | T | 0.54 | 1.20 (1.12–1.27) | 1.07 × 10−6 | 0.35 | 1.84 × 10−6 | 1.20 |

| rs2423669 | 20:12431381 | BTBD3 – SPTLC3 | T | 0.45 | 0.84 (0.76–0.91) | 1.19 × 10−6 | 0.25 | 2.46 × 10−6 | 0.84 |

| rs34163230 | 20:12429780 | BTBD3 – SPTLC3 | T | 0.43 | 0.83 (0.75-0.90) | 1.20 × 10−6 | 0.88 | 1.41 × 10−6 | 0.83 |

| rs6131339 | 20:12427947 | BTBD3 – SPTLC3 | C | 0.45 | 0.84 (0.76–0.91) | 1.30 × 10−6 | 0.34 | 2.28 × 10−6 | 0.84 |

| rs2423668 | 20:12430673 | BTBD3 – SPTLC3 | T | 0.46 | 0.84 (0.76–0.91) | 1.38 × 10−6 | 0.32 | 2.32 × 10−6 | 0.84 |

| rs2423667 | 20:12430414 | BTBD3 – SPTLC3 | A | 0.46 | 0.84 (0.76–0.91) | 1.38 × 10−6 | 0.32 | 2.32 × 10−6 | 0.84 |

| rs36067435 | 4:111101546 | ELOVL6, intron | G | 0.65 | 0.83 (0.75–0.91) | 1.40 × 10−6 | 0.36 | 2.50 × 10−5 | 0.84 |

| rs2423658 | 20:12418229 | BTBD3 – SPTLC3 | A | 0.45 | 0.84 (0.77–0.91) | 1.41 × 10−6 | 0.41 | 2.24 × 10−6 | 0.84 |

| rs2423660 | 20:12418517 | BTBD3 – SPTLC3 | T | 0.55 | 1.19 (1.12–1.27) | 1.47 × 10−6 | 0.44 | 2.13 × 10−6 | 1.19 |

Figure 1.

Genome-wide genetically-predicted gene expression and SNP association meta-analysis results with BPH.

We also evaluated the previously identified variants from recent GWAS to determine whether variants replicated across studies (Table 4)49,50. None of the variants reported in those studies were significant or suggestively associated with BPH in this analysis, although effect estimates were largely consistent in both direction and magnitude. Restricting to whites only to more closely match the papers49,50 did not yield significant results.

Table 4.

Replication of suggestive index SNPs reported in recent GWAS of BPH.

| SNP | CHR:BP (hg19) | Gene | PMID | P-value | OR | EAab | OAac | eMERGE P-value | OR (95% CI) | eMERGE Effect Allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs6537704 | 1:112052105 | ADORA3 | 28656603 | 1.1 × 10−5 | 1.34 | G | A | 0.17 | 1.08 (0.97–1.19) | T |

| rs10915971 | 1:226508645 | PARP1 | 28656603 | 3.9 × 10−5 | 1.21 | A | G | 0.33 | 0.96 (0.88–1.04) | T |

| rs10202096 | 2:28596317 | FOSL2 | 28656603 | 1.1 × 10−5 | 0.81 | A | G | 0.2 | 1.05 (0.97–1.13) | A |

| rs2556378 | 2:60762502 | BCL11A | 30410027 | 3.4 × 10−12 | 1.12 | T | G | 0.020 | 1.13(1.03-1.22) | T |

| rs12490648 | 3:27782163 | EOMES | 28656603 | 7.8 × 10−6 | 1.48 | G | A | 0.53 | 1.05 (0.89–1.22) | A |

| rs7630221 | 3:37192199 | LRRFIP2 | 28656603 | 1.4 × 10−5 | 1.22 | A | G | 0.7 | 0.99 (0.92–1.06) | A |

| rs3922844 | 3:38624253 | SCN5A | 28656603 | 1.8 × 10−5 | 1.23 | A | G | 0.37 | 0.97 (0.89–1.04) | T |

| rs2853677 | 5:1287194 | TERT | 30410027 | 1.7 × 10−12 | 1.09 | G | A | 0.021 | 1.09 (1.02–1.17) | G |

| rs381949 | 5:1322468 | CLPTM1L | 30410027 | 4.9 × 10−19 | 0.9 | A | G | 0.033 | 0.92 (0.85–1.00) | A |

| rs2676245 | 5:13628062 | DNAH5 | 28656603 | 7.3 × 10−6 | 0.81 | A | G | 0.95 | 1.00 (0.93–1.08) | A |

| rs10054105 | 5:110909333 | STARD4 | 30410027 | 3.5 × 10−12 | 0.91 | G | T | 0.80 | 0.99 (0.90–1.08) | G |

| rs677394 | 5:134607559 | C5orf66, H2AFY | 30410027 | 2.9 × 10−11 | 0.88 | G | C | 0.50 | 0.96 (0.82–1.09) | G |

| rs200476 | 6:27768348 | HIST1H2BL | 30410027 | 3.9 × 10−17 | 0.88 | T | A | 0.076 | 0.92 (0.82–1.01) | T |

| rs17144046 | 10:8606014 | GATA3 | 28656603 | 8.9 × 10−7 | 1.41 | G | A | 0.068 | 1.08 (1.00–1.16) | A |

| rs7906649 | 10:22310298 | EBLN1 | 30410027 | 2.1 × 10−7 | 1.07 | G | A | 0.74 | 1.01 (0.93-1.10) | G |

| rs148678804 | 10:22427289 | DNAJC1 | 30410027 | 3.0 × 10−14 | 1.27 | A | G | 0.52 | 0.91 (0.63–1.19) | A |

| rs7911634 | 10:56441151 | PCDH15 | 28656603 | 1.5 × 10−5 | 0.67 | A | C | 0.87 | 1.01 (0.87–1.16) | T |

| rs4548546 | 10:122629579 | WDR11 | 30410027 | 2.0 × 10−16 | 1.11 | T | C | 0.099 | 1.07 (0.99–1.14) | T |

| rs11199879 | 10:123045212 | FGFR2 | 30410027 | 5.7 × 10−23 | 1.14 | C | T | 0.0065 | 1.13 (1.04–1.21) | C |

| rs72878024 | 11:199492 | ODF3 | 30410027 | 1.4 × 10−12 | 0.85 | A | G | 0.43 | 0.94 (0.79–1.09) | A |

| rs428215 | 11:37126189 | RAG2 | 28656603 | 4.2 × 10−5 | 0.76 | G | A | 0.8 | 0.98 (0.87–1.10) | T |

| rs10894022 | 11:129191124 | BARX2 | 28656603 | 2.6 × 10−5 | 0.79 | A | G | 0.48 | 0.97 (0.87–1.06) | T |

| rs11613206 | 12:40609581 | LRRK2 | 28656603 | 4.9 × 10−5 | 1.15 | A | G | 0.81 | 0.98 (0.81–1.15) | A |

| rs6538357 | 12:93150937 | PLEKHG7 | 28656603 | 4.9 × 10−5 | 0.84 | C | A | 0.61 | 0.98 (0.91–1.05) | A |

| rs2555019 | 12:114668618 | TBX5 | 30410027 | 2.4 × 10−11 | 0.93 | T | C | 0.66 | 0.98 (0.91–1.06) | T |

| rs8853 | 12:115108907 | TBX3 | 30410027 | 1.4 × 10−9 | 1.07 | C | T | 0.47 | 1.03 (0.95–1.10) | C |

| rs1638703 | 13:51088356 | DLEU1 | 30410027 | 1.1 × 10−13 | 1.1 | C | G | 0.19 | 1.06 (0.98–1.14) | C |

| rs6561599 | 13:51478918 | RNASEH2B | 30410027 | 1.8 × 10−7 | 0.94 | C | G | 0.26 | 0.96 (0.89–1.03) | C |

| rs9302078 | 13:96171939 | CLDN10 | 28656603 | 3.0 × 10−5 | 0.83 | A | G | 0.67 | 1.02 (0.94–1.09) | A |

| rs7152796 | 14:89924520 | FOXN3 | 28656603 | 4.0 × 10−5 | 1.46 | A | G | 0.94 | 0.99 (0.84–1.15) | T |

| rs943587 | 14:97636701 | VRK1 | 28656603 | 0.80 | 1.11 | G | A | 0.96 | 1.00 (0.91–1.10) | A |

| rs11651052 | 17:36102381 | HNF1B | 30410027 | 3.2 × 10−10 | 0.93 | A | G | 0.77 | 0.99 (0.92–1.06) | A |

| rs9958656 | 18:19904144 | GATA6 | 30410027 | 4.3 × 10−19 | 1.11 | T | C | 0.031 | 1.08 (1.01–1.16) | T |

| rs17670370 | 18:20034017 | CTAGE1 | 30410027 | 1.6 × 10−7 | 1.07 | G | T | 0.31 | 0.96 (0.87–1.04) | G |

| rs11084596 | 19:32104979 | THEG5 | 30410027 | 2.1 × 10−24 | 0.88 | C | T | 0.33 | 1.04 (0.96–1.12) | C |

| rs6061244 | 20:61041653 | GATA5 | 30410027 | 5.7 × 10−8 | 0.94 | C | G | 0.27 | 0.96 (0.88–1.03) | C |

| rs200383755 | 20:61050522 | GATA5 | 30410027 | 3.2 × 10−9 | 0.67 | C | G | NA | NA | NA |

aNa et al. (PMID 28656603) contained no indication for which was the modeled effect allele. For the purpose of this table, their A1 is listed as EA, and A2 is under OA. bEffect Allele. cOther Allele.

Gene expression

We also evaluated genetically predicted gene expression (GPGE) in prostate tissue using S-PrediXcan51 and models constructed in GTEx samples52 (Table 5; Fig. 1). The top result did not reach statistical significance (Bonferroni threshold for number of genes, p-value < 1.93 × 10−5) was with increased predicted expression of ETS variant 4 (ETV4; chromosome 17; p-value = 0.0015). Other nominally significant genes were identified on chromosomes 6, 20, 3, 14, 1, and 7. It is noteworthy that neither of the genes on chromosome 6 (histone cluster 1 H3 family member e [HIST1H3E]) and 20 (gonadotropin-releasing hormone 2 [GNRH2], were near the top signals implicated in the GWAS results (GLGC and the intergenic region between BTBD3 and SPTLC3), instead these suggestive GPGE results arose from secondary signals in other regions.

Table 5.

Suggestive results from predicted gene expression in prostate.

| Gene | Chromosome | Effect Size | P-value | Variance | Prediction-Performance R2 | N SNPs used | N SNPs in model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETV4 | 17 | 1.83 | 0.0015 | 0.002 | 0.061 | 3 | 3 |

| SCAP | 3 | −0.42 | 0.0032 | 0.034 | 0.070 | 5 | 5 |

| RPS6KL1 | 14 | −0.16 | 0.0093 | 0.179 | 0.112 | 46 | 47 |

| LAMB2 | 3 | 0.13 | 0.011 | 0.251 | 0.074 | 32 | 47 |

| TMEM240 | 1 | 0.35 | 0.012 | 0.048 | 0.062 | 16 | 18 |

| SLC22A15 | 1 | −0.22 | 0.014 | 0.086 | 0.164 | 12 | 12 |

| SLC45A1 | 1 | −0.81 | 0.016 | 0.006 | 0.069 | 2 | 3 |

| HIST1H3E | 6 | −0.13 | 0.019 | 0.244 | 0.116 | 57 | 61 |

| GNRH2 | 20 | −0.36 | 0.021 | 0.031 | 0.118 | 2 | 2 |

| INMT | 7 | −0.13 | 0.021 | 0.214 | 0.059 | 46 | 48 |

| TIGIT | 3 | −5.21 | 0.022 | 0.000 | 0.066 | 2 | 2 |

Discussion

We have performed the first SNP-based heritability assessments of BPH followed by a trans-ethnic GWAS and evaluation of genetically predicted gene expression in prostate tissue. Our results indicate that BPH is likely to be substantially heritable, with consistent point estimates near 60% across two comparable EMR-based cohorts, which is somewhat higher than the 49% reported previously from twin studies24. The LUTS symptom score heritability however has been reported to be variable, with estimates ranging from 20 to 83%. The cases in this study likely have overt symptoms of BPH that lead to their clinical diagnoses and treatments, and may represent a more severe phenotype than from some cohort studies.

In this first GWAS of EHR-assessed BPH, we identified previously unreported suggestive SNPs. The gene containing the top SNP from the GWAS, SYN3 is a neuronal protein53,54 which has been implicated in GWAS of many diverse phenotypes including age-related macular degeneration55–57, height58–60, and uric acid levels61. Expression of SYN3 in GTEx is highest in testis, followed by several brain regions, but is low in prostate and no predictive model was constructed for SYN3 expression in that tissue52,62. Another neuronal protein UNC13A (unc-13 homolog A) was also implicated from these GWAS results. Variants near this gene have been consistently associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in several genome-wide studies63–65.

The second suggestive signal from GWAS, in the gene GCLC is also interesting, due in part to the localization of the SNP-based heritability on chromosome 6. Also relevant is the finding of modest association with the lead variant (rs534957) from our study which also demonstrated a weak association with prostatitis in the UK Biobank data (p-value = 6 × 10−3; as viewed in the Global Biobank Engine66 [https://biobankengine.stanford.edu/]). This suggests a consistent finding with another EHR-defined data set despite differences in case/control classification. Additionally, the identification of suggestive GPGE on chromosome 6 apart from the GCLC locus provides modest support for the heritability analysis, suggesting that the relevant SNPs have yet to be detected, perhaps due to a lack of power in the present studies.

One of the more biologically interesting candidates identified in this study is GNRH2 (gonadotropin-releasing hormone 2). GPGE analysis indicated that reduced expression of this gene in the prostate was associated with increased risk of BPH (p-value = 0.021). GNRH2 is expressed in the prostate67–70 and its expression is regulated by several reproductive hormones71. Both gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists and agonists have been investigated as treatments for BPH and prostate cancer12,16,72–77, however, the side effects have made many of these impractical as therapeutic options. There is currently a Phase 3 trial underway to evaluate whether a GnRH antagonist in combination with radiation can improve progression of prostate cancer. This therapeutic was previously part of a phase 2 trial for efficacy in BPH, however the trial was stopped early due to not meeting primary efficacy endpoints. This is potentially consistent with the results observed here in which reduced expression levels of GNRH2 are associated with increased risk of BPH. A genetic variant in GNRH2 (rs6051545) was observed to impact testosterone levels during androgen deprivation therapy to treat metastatic prostate cancer78. It has been suggested that this may lead to a negative effect of the therapy on prognosis78.

Of the 11 genes included in Table 5, more than half of them have been previously reported such that expression changes have been associated in prostate tissue, often with various stages of prostate cancer. The top result from the GPGE analysis, ETV4 (ETS variant 4) has been previously found in studies of prostate cancer to have significantly higher relative expression in the tumor tissues than in benign samples79, as well as an association with poor prognosis80,81. We found that increased predicted expression of ETV4 is associated with increased risk of BPH in this study (p-value = 0.0015). Laminin subunit beta 2 (LAMB2) has been identified as being downregulated in the transition from prostate intraepithelial neoplasia to invasive prostate cancer from differential expression analysis82. Our results suggest that increasing LAMB2 expression is associated with increased risk of BPH. SCAP, which encodes SREBP cleavage-activating protein, has also been identified to show expression changes in prostate cancer83,84, and has been specifically noted to be regulated by androgens83,85. Recently, TIGIT expression has been implicated in failures of prostate cancer checkpoint inhibition86,87. Together, these results suggest that though these results did not achieve statistical significance, germline genetic associations with BPH may alter gene expression in prostate tissue, and that those genes without a presently documented role may yet be identified as important in studies of prostate gene expression implicated in disease.

There have been two recent GWAS of BPH in whites which have identified many significant and suggestive associations, though none were identified by both studies. Evaluation of these reported signals in the eMERGE data revealed modest associations at only five loci, including BCL11A, TERT, CLPTM1L, GATA6, and FGFR2 (Table 4). It is notable, that although none of the variants reported were significant in this study, effect estimates were largely consistent in both direction and magnitude. The lack of replication may be due in part to differences across studies in disease definition (varied use of IPSS scores, prostate volume, history of transurethral resection of the prostate, etc), participant recruitment from clinical trials, community cohorts, and hospital-based populations, or differences in age. Evaluation of associated variation reported in candidate gene analyses of BPH28,30–32,34,37,38,88 and an evaluation of prostate volume48 did not yield any suggestive results in the present study (Supplementary Table 3).

Previous studies have shown adequate positive and negative predictive values based on electronic diagnoses (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD9) codes and problem list) for BPH89, however, the phenotyping of BPH in the medical record likely reflects the presence of symptoms. Studies of care-seeking behavior with respect to BPH and LUTS have consistently shown that those seeking medical care tend to have higher symptom scores/more severe symptoms, but that reasons for not seeking treatment include diverse social and treatment concerns, even among those experiencing symptoms90–94. This suggests the possibility that some portion of the controls in our study may have experienced (or will experience in the future) symptoms of BPH but have not (yet) sought treatment for the condition. This is a limitation of the present study.

Based on these results, wherein BPH was shown to be heritable but no significant susceptibility loci were detected, it seems that BPH is a complex disease made up of many physiological symptoms and the genetic underpinnings of this trait are likely to consist of a multitude of variants of small effect. This makes large sample sizes crucial for detecting genetic loci associated with BPH as has been demonstrated50. In conclusion, we have shown that BPH is heritable, identified suggestive association signals, and are the first to evaluate the association between BPH and genetically-predicted gene expression in prostate.

Methods

Study Populations

The eMERGE Network is a consortium of several EHR-linked biorepositories formed with the goal of developing approaches for the use of the EHR in genomic research95,96. Consortium membership has evolved over eMERGE’s 11 year history, with many sites contributing data including Group Health/University of Washington, Marshfield Clinic, Mayo Clinic, Northwestern University, Vanderbilt University (Phase 1 sites), Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), Boston Children’s Hospital (BCH), Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC), Geisinger Health System, Mount Sinai School of Medicine (sites added in Phase 2), Harvard University and Columbia University (sites added in Phase 3). The eMERGE study was approved by the Ethical Committee/Institutional Review Board at each site (Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Group Health/University of Washington, Marshfield Clinic, Mayo Clinic, Northwestern University, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Boston Children’s Hospital, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Geisinger Health System, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Harvard University and Columbia University) and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. In this study of BPH, data from the eMERGE pediatric study sites (CHOP, BCH, CCHMC) were not included. Participants at all study sites provided written, informed consent, and for participants under the age of 18 years (who were not included in the analyses presented herein), informed consent was obtained from a parent and/or legal guardian.

Phenotyping

Among men of at least age 40, without prostate or bladder cancers (defined via ICD9 codes [233.4, 233.7 or 233.9], tumor registries [Primary site = C619] and problem lists [containing keywords e.g. “prostate cancer”, “malignant tumor of the prostate”, “bladder cancer”, “bladder CA”), we included all cases of BPH with at least two ICD9 codes indicating a BPH diagnosis (600, 600.0, 600.0*, 600.2, 600.2*, 600.9, 600.9*), in addition to either receiving medications for the treatment of BPH or 1 or more procedure (Current Procedural Terminology [CPT]) codes for BPH-related surgeries (52450, 52601, 52630, 52648, 53850, 53852). Controls were males of at least age 40, with at least 3 outpatient visits within any 2-year period after the age of 40, without prostate or bladder cancer or instances of BPH ICD9 codes, medications or BPH-related surgical CPT codes. The algorithm is available on PheKB.org (https://phekb.org/phenotype/216).

Genotyping and Quality Control

Genotyping was performed for eMERGE-1 study sites using one of two Illumina arrays across two genotyping centers. Individuals of self-identified or administratively-assigned European-descent were genotyped on the Illumina 660W-Quad, while individuals of self-identified or administratively-assigned African-descent were genotyped on the Illumina 1 M. For the majority of patients, genotyping was performed at one of two centers: the Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR) at Johns Hopkins University and the Center for Genotyping and Analysis at the Broad Institute as previously described95,96. Existing genotype data available for eMERGE-2 and -3 study sites included data from the Illumina 550, Illumina 610, Illumina HumanOmni Express, Illumina MultiEthnic Genotyping Array, Illumina CoreExome, and Affymetrix 6.0 arrays.

Genotype quality control (QC) was performed within each study population, and a uniform protocol was implemented. QC for all studies was performed using PLINK97, including a 95% single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and individual call rate threshold, removal of first-degree related individuals, sex checks, alignment of alleles to the genomic ‘+’ strand. Visualization of ancestry by principal components analysis was performed by study using either Eigenstrat98 or flashPCA99.

Statistical Analysis

Restricted maximum likelihood estimation as implemented in GCTA100 was used to determine the proportion of phenotypic variance explained by common additive genetic variants in two cohorts, eMERGE-1 and Geisinger CoreExome. Data was filtered to include only common variants (MAF > 0.05), and samples with IBD probabilities <0.025, as well as restricted using principal components to retain only EA samples. Disease prevalence was based on average age within cohort and set at 0.67 for eMERGE-1 and 0.63 for Geisinger CoreExome.

Genotype data was imputed from the 1000 Genomes Project haplotypes using SHAPEIT2101 and IMPUTE2102 by site or study and analyzed for associations separately. We used logistic regression to model BPH risk as a function of genotype, age, and principal components of ancestry with the SNPTEST software package, with subsequent meta-analysis performed using METAL103. There was no substantial genomic inflation observed, with a meta-analysis lambda of 1.017 (Supplementary Fig. 2).

To further evaluate the genetic association results in the context of gene expression, we employed the novel method S-PrediXcan51, an extension of the PrediXcan method62. PrediXcan conducts a test of association between phenotypes and gene expression levels predicted by genetic variants in a library of tissues from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project52,104. S-PrediXcan is a meta-analysis approach that conducts the PrediXcan test using genotype association summary statistics, rather than performing the tests in individual-level data. We utilized covariance matrices built for prostate tissue from GTEx to annotate SNP association signals as well as to provide information about likely tissue expression patterns and relevant biological information.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

J.N.H. was supported by T32CA160056 (P.I. X-O Shu). The eMERGE Network was initiated and funded by the NHGRI through the following grants: U01HG8657 (Kaiser Washington/University of Washington); U01HG8685 (Brigham and Women’s Hospital); U01HG8672 (Vanderbilt University Medical Center); U01HG8666 (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center); U01HG6379 (Mayo Clinic); U01HG8679 (Geisinger Clinic); U01HG8680 (Columbia University Health Sciences); U01HG8684 (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia); U01HG8673 (Northwestern University); U01HG8701 (Vanderbilt University Medical Center serving as the Coordinating Center); U01HG8676 (Partners Healthcare/Broad Institute); and U01HG8664 (Baylor College of Medicine). Some of the dataset(s) used for the analyses described were obtained from Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s BioVU which is supported by institutional funding, the 1S10RR025141-01 instrumentation award, and by the CTSA grant UL1TR000445 from NCATS/NIH. The authors would also like to acknowledge NCATS grant UL1TR002373 (P.I. Marc Drezner).

Author Contributions

Study design/conception: D.M.R., J.C.D., T.L.E.; Data collection/Sample recruitment: K.M.B., D.M.R., J.C.D., M.B., J.G.L., G.J., N.S., G.H., D.C., A.G., P.D., P.L.P., P.A.M.S., H.H.; Data analysis: J.N.H., E.S.T., T.L.E.; Methods/Algorithm Development: J.C.D., R.C., S.S.; Manuscript writing: J.N.H., D.R.V.E., T.L.E.; Manuscript editing/comments: M.D.R., S.S.V., D.M.R., J.C.D., J.G.L.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the eMERGE dbGAP repository (accession phs000888.v1.p1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs000888.v1.p1).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Digna R. Velez Edwards, Email: digna.r.velez.edwards@vumc.org

Todd L. Edwards, Email: todd.l.edwards@vumc.org

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-42427-z.

References

- 1.Lee SWH, Chan EMC, Lai YK. The global burden of lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific reports. 2017;7:7984. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06628-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster SA, Shortridge EF, DiBonaventura M, Viktrup L. Predictors of self-reported benign prostatic hyperplasia in European men: analysis of the European National Health and Wellness Survey. World journal of urology. 2015;33:639–647. doi: 10.1007/s00345-014-1366-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chokkalingam AP, et al. Prevalence of BPH and lower urinary tract symptoms in West Africans. Prostate cancer and prostatic diseases. 2012;15:170–176. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2011.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foo KT. Pathophysiology of clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia. Asian journal of urology. 2017;4:152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ajur.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egan KB. The Epidemiology of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Associated with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: Prevalence and Incident Rates. The Urologic clinics of North America. 2016;43:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Speakman M, Kirby R, Doyle S, Ioannou C. Burden of male lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) - focus on the UK. BJU international. 2015;115:508–519. doi: 10.1111/bju.12745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez-Nieves JA, Macoska JA. Prostatic fibrosis, lower urinary tract symptoms, and BPH. Nature reviews. Urology. 2013;10:546–550. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2013.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung JH, et al. The association of benign prostatic hyperplasia with lower urinary tract stones in adult men: A retrospective multicenter study. Asian journal of urology. 2018;5:118–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ajur.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang W, et al. Risk factors for bladder calculi in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Medicine. 2017;96:e7728. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000007728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ko YH, et al. Clinical Implications of Residual Urine in Korean Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) Patients: A Prognostic Factor for BPH-Related Clinical Events. International neurourology journal. 2010;14:238–244. doi: 10.5213/inj.2010.14.4.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bishr M, et al. Medical management of benign prostatic hyperplasia: Results from a population-based study. Canadian Urological Association journal = Journal de l’Association des urologues du Canada. 2016;10:55–59. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar R, Malla P, Kumar M. Advances in the design and discovery of drugs for the treatment of prostatic hyperplasia. Expert opinion on drug discovery. 2013;8:1013–1027. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2013.797960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim EH, Brockman JA, Andriole GL. The use of 5-alpha reductase inhibitors in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Asian journal of urology. 2018;5:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ajur.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallner LP, et al. 5-Alpha Reductase Inhibitors and the Risk of Prostate Cancer Mortality in Men Treated for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2016;91:1717–1726. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirshburg JM, Kelsey PA, Therrien CA, Gavino AC, Reichenberg JS. Adverse Effects and Safety of 5-alpha Reductase Inhibitors (Finasteride, Dutasteride): A Systematic Review. The Journal of clinical and aesthetic dermatology. 2016;9:56–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russo A, et al. Latest pharmacotherapy options for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2014;15:2319–2328. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2014.955470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malaeb BS, Yu X, McBean AM, Elliott SP. National trends in surgical therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia in the United States (2000-2008) Urology. 2012;79:1111–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.11.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rieken M, Antunes-Lopes T, Geavlete B, Marcelissen T. What Is New with Sexual Side Effects After Transurethral Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptom Surgery? European urology focus. 2018;4:43–45. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gacci M, et al. Best practice in the management of storage symptoms in male lower urinary tract symptoms: a review of the evidence base. Therapeutic advances in urology. 2018;10:79–92. doi: 10.1177/1756287217742837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreira AM, et al. A Review of Adverse Events Related to Prostatic Artery Embolization for Treatment of Bladder Outlet Obstruction Due to BPH. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. 2017;40:1490–1500. doi: 10.1007/s00270-017-1765-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qian X, et al. Functional outcomes and complications following B-TURP versus HoLEP for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a review of the literature and Meta-analysis. The aging male: the official journal of the International Society for the Study of the Aging Male. 2017;20:184–191. doi: 10.1080/13685538.2017.1295436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Afari N, et al. Heritability of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Men: A Twin Study. The Journal of urology. 2016;196:1486–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meikle AW, Bansal A, Murray DK, Stephenson RA, Middleton RG. Heritability of the symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia and the roles of age and zonal prostate volumes in twins. Urology. 1999;53:701–706. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(98)00569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Partin AW, et al. Concordance rates for benign prostatic disease among twins suggest hereditary influence. Urology. 1994;44:646–650. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(94)80197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoke GP, McWilliams GW. Epidemiology of benign prostatic hyperplasia and comorbidities in racial and ethnic minority populations. The American journal of medicine. 2008;121:S3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colon I, Payne RE. Benign prostatic hyperplasia and lower urinary tract symptoms in African Americans and Latinos: treatment in the context of common comorbidities. The American journal of medicine. 2008;121:S18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee CL, Lee J, Na YG, Song KH. Combined effect of polymorphisms in type III 5-alpha reductase and androgen receptor gene with the risk of benign prostatic hyperplasia in Korea. Journal of exercise rehabilitation. 2016;12:504–508. doi: 10.12965/jer.1632802.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim SK, et al. Association between polymorphisms of estrogen receptor 2 and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Experimental and therapeutic medicine. 2015;10:1990–1994. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choubey VK, et al. SRD5A2 gene polymorphisms and the risk of benign prostatic hyperplasia but not prostate cancer. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP. 2015;16:1033–1036. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.3.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruan L, et al. Association between single nucleotide polymorphism of vitamin D receptor gene FokI polymorphism and clinical progress of benign prostatic hyperplasia. TheScientificWorldJournal. 2015;2015:235895. doi: 10.1155/2015/235895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winchester D, et al. SPINK1 Promoter Variants Are Associated with Prostate Cancer Predisposing Alterations in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Patients. Anticancer research. 2015;35:3811–3819. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ban JY, Yoo KH. Promoter Polymorphism (rs12770170, -184C/T) of Microseminoprotein, Beta as a Risk Factor for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia in Korean Population. International neurourology journal. 2014;18:63–67. doi: 10.5213/inj.2014.18.2.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar V, et al. Association of CYP1A1, CYP1B1 and CYP17 gene polymorphisms and organochlorine pesticides with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Chemosphere. 2014;108:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.02.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seok H, Yoo KH, Kim YO, Chung JH. Association of a Missense ALDH2 Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (Glu504Lys) With Benign Prostate Hyperplasia in a Korean Population. International neurourology journal. 2013;17:168–173. doi: 10.5213/inj.2013.17.4.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karatzas A, et al. Lack of association between the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1) gene polymorphism and the risk of benign prostatic hyperplasia in Caucasian men. Molecular biology reports. 2013;40:6665–6669. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2781-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zambra FM, Biolchi V, Brum IS, Chies JA. CCR2 and CCR5 genes polymorphisms in benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Human immunology. 2013;74:1003–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2013.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qi J, et al. Genetic variants in 2q31 and 5p15 are associated with aggressive benign prostatic hyperplasia in a Chinese population. Prostate. 2013;73:1182–1190. doi: 10.1002/pros.22666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiao Y, et al. LILRA3 is associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia risk in a Chinese Population. International journal of molecular sciences. 2013;14:8832–8840. doi: 10.3390/ijms14058832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biolchi V, et al. Androgen receptor GGC polymorphism and testosterone levels associated with high risk of prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Molecular biology reports. 2013;40:2749–2756. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2293-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choubey VK, et al. Null genotypes at the GSTM1 and GSTT1 genes and the risk of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a case-control study and a meta-analysis. Prostate. 2013;73:146–152. doi: 10.1002/pros.22549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biolchi V, Silva Neto B, Koff W, Brum IS. Androgen receptor CAG polymorphism and the risk of benign prostatic hyperplasia in a Brazilian population. International braz j urol: official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology. 2012;38:373–379. doi: 10.1590/S1677-55382012000300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Izmirli M, Arikan B, Bayazit Y, Alptekin D. Associations of polymorphisms in HPC2/ELAC2 and SRD5A2 genes with benign prostate hyperplasia in Turkish men. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP. 2011;12:731–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Konwar R, et al. Glutathione S-transferase (GST) gene variants and risk of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a report in a North Indian population. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP. 2010;11:1067–1072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mittal RD, Kesarwani P, Singh R, Ahirwar D, Mandhani A. GSTM1, GSTM3 and GSTT1 gene variants and risk of benign prostate hyperplasia in North India. Disease markers. 2009;26:85–91. doi: 10.3233/dma-2009-0611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma Z, et al. Polymorphisms of fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 have association with the development of prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia and the progression of prostate cancer in a Japanese population. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 2008;123:2574–2579. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Das K, et al. Shorter CAG repeats in androgen receptor and non-GG genotypes in prostate-specific antigen loci are associated with decreased risk of benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Cancer Lett. 2008;268:340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cartwright R, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of candidate gene association studies of lower urinary tract symptoms in men. European urology. 2014;66:752–768. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giri A, Edwards TL, Motley SS, Byerly SH, Fowke JH. Genetic Determinants of Metabolism and Benign Prostate Enlargement: Associations with Prostate Volume. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Na R, et al. A genetic variant near GATA3 implicated in inherited susceptibility and etiology of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) Prostate. 2017;77:1213–1220. doi: 10.1002/pros.23380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gudmundsson J, et al. Genome-wide associations for benign prostatic hyperplasia reveal a genetic correlation with serum levels of PSA. Nature communications. 2018;9:4568. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06920-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barbeira AN, et al. Exploring the phenotypic consequences of tissue specific gene expression variation inferred from GWAS summary statistics. Nature communications. 2018;9:1825. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03621-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: Multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science (New York, N.Y.)348, 648–660, 10.1126/science.1262110 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Kao HT, et al. A third member of the synapsin gene family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4667–4672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hosaka M, Sudhof TC. Synapsin III, a novel synapsin with an unusual regulation by Ca2+ J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13371–13374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fritsche LG, et al. Seven new loci associated with age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet. 2013;45(433–439):439e431–432. doi: 10.1038/ng.2578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Neale BM, et al. Genome-wide association study of advanced age-related macular degeneration identifies a role of the hepatic lipase gene (LIPC) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7395–7400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912019107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen W, et al. Genetic variants near TIMP3 and high-density lipoprotein-associated loci influence susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7401–7406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912702107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wood AR, et al. Defining the role of common variation in the genomic and biological architecture of adult human height. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1173–1186. doi: 10.1038/ng.3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.He M, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of adult height in East Asians identifies 17 novel loci. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:1791–1800. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lango Allen H, et al. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature. 2010;467:832–838. doi: 10.1038/nature09410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Charles BA, et al. A genome-wide association study of serum uric acid in African Americans. BMC medical genomics. 2011;4:17. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gamazon ER, et al. A gene-based association method for mapping traits using reference transcriptome data. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1091–1098. doi: 10.1038/ng.3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Es MA, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 19p13.3 (UNC13A) and 9p21.2 as susceptibility loci for sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1083–1087. doi: 10.1038/ng.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Benyamin B, et al. Cross-ethnic meta-analysis identifies association of the GPX3-TNIP1 locus with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature communications. 2017;8:611. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00471-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Rheenen W, et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify new risk variants and the genetic architecture of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1043–1048. doi: 10.1038/ng.3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McInnes, G. et al. Global Biobank Engine: enabling genotype-phenotype browsing for biobank summary statistics. bioRxiv, 10.1101/304188 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Desaulniers AT, Cederberg RA, Lents CA, White BR. Expression and Role of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone 2 and Its Receptor in Mammals. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2017;8:269. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Millar R, et al. A novel mammalian receptor for the evolutionarily conserved type II GnRH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9636–9641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141048498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Neill JD, Duck LW, Sellers JC, Musgrove LC. A gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor specific for GnRH II in primates. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2001;282:1012–1018. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.White RB, Eisen JA, Kasten TL, Fernald RD. Second gene for gonadotropin-releasing hormone in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:305–309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Darby S, et al. Expression of GnRH type II is regulated by the androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Endocrine-related cancer. 2007;14:613–624. doi: 10.1677/erc-07-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sakai M, Elhilali M, Papadopoulos V. The GnRH Antagonist Degarelix Directly Inhibits Benign Prostate Hyperplasia Cell Growth. Hormone and metabolic research = Hormon- und Stoffwechselforschung = Hormones et metabolisme. 2015;47:925–931. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1555899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Raja A, Hori S, Armitage JN. Hormonal manipulation of lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic obstruction. Indian journal of urology: IJU: journal of the Urological Society of India. 2014;30:189–193. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.126904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rick FG, et al. Hormonal manipulation of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Current opinion in urology. 2013;23:17–24. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32835abd18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Polisca A, et al. Clinical efficacy of the GnRH agonist (deslorelin) in dogs affected by benign prostatic hyperplasia and evaluation of prostatic blood flow by Doppler ultrasound. Reproduction in domestic animals = Zuchthygiene. 2013;48:673–680. doi: 10.1111/rda.12143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Soler R, et al. Future direction in pharmacotherapy for non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract symptoms. European urology. 2013;64:610–621. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lepor H. The role of gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Reviews in urology. 2006;8:183–189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shiota Masaki, Fujimoto Naohiro, Takeuchi Ario, Kashiwagi Eiji, Dejima Takashi, Inokuchi Junichi, Tatsugami Katsunori, Yokomizo Akira, Kajioka Shunichi, Uchiumi Takeshi, Eto Masatoshi. The Association of Polymorphisms in the Gene Encoding Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone with Serum Testosterone Level during Androgen Deprivation Therapy and Prognosis of Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Journal of Urology. 2018;199(3):734–740. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.09.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cavazzola LR, et al. Relative mRNA expression of prostate-derived E-twenty-six factor and E-twenty-six variant 4 transcription factors, and of uridine phosphorylase-1 and thymidine phosphorylase enzymes, in benign and malignant prostatic tissue. Oncology letters. 2015;9:2886–2894. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Qi M, et al. Overexpression of ETV4 is associated with poor prognosis in prostate cancer: involvement of uPA/uPAR and MMPs. Tumour biology: the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2015;36:3565–3572. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2993-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mesquita D, et al. Specific and redundant activities of ETV1 and ETV4 in prostate cancer aggressiveness revealed by co-overexpression cellular contexts. Oncotarget. 2015;6:5217–5236. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ashida S, et al. Molecular features of the transition from prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) to prostate cancer: genome-wide gene-expression profiles of prostate cancers and PINs. Cancer research. 2004;64:5963–5972. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-04-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Heemers H, et al. Androgens stimulate lipogenic gene expression in prostate cancer cells by activation of the sterol regulatory element-binding protein cleavage activating protein/sterol regulatory element-binding protein pathway. Molecular endocrinology (Baltimore, Md.) 2001;15:1817–1828. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.10.0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Prabhu AV, Krycer JR, Brown AJ. Overexpression of a key regulator of lipid homeostasis, Scap, promotes respiration in prostate cancer cells. FEBS letters. 2013;587:983–988. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Heemers H, et al. Identification of an androgen response element in intron 8 of the sterol regulatory element-binding protein cleavage-activating protein gene allowing direct regulation by the androgen receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30880–30887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Papanicolau-Sengos A, et al. Identification of targets for prostate cancer immunotherapy. Prostate. 2019;79:498–505. doi: 10.1002/pros.23756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nava Rodrigues D, et al. Immunogenomic analyses associate immunological alterations with mismatch repair defects in prostate cancer. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:4441–4453. doi: 10.1172/jci121924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gu X, et al. SRD5A1 and SRD5A2 are associated with treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia with the combination of 5alpha-reductase inhibitors and alpha-adrenergic receptor antagonists. The Journal of urology. 2013;190:615–619. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Szeto HC, Coleman RK, Gholami P, Hoffman BB, Goldstein MK. Accuracy of computerized outpatient diagnoses in a Veterans Affairs general medicine clinic. The American journal of managed care. 2002;8:37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kok ET, et al. Simple case definition of clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia, based on International Prostate Symptom Score, predicts general practitioner consultation rates. Urology. 2006;68:784–789. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Roberts RO, et al. Natural history of prostatism: worry and embarrassment from urinary symptoms and health care-seeking behavior. Urology. 1994;43:621–628. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(94)90174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jacobsen SJ, et al. Natural history of prostatism: factors associated with discordance between frequency and bother of urinary symptoms. Urology. 1993;42:663–671. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(93)90530-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sarma AV, Wallner L, Jacobsen SJ, Dunn RL, Wei JT. Health seeking behavior for lower urinary tract symptoms in black men. The Journal of urology. 2008;180:227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wolters R, Wensing M, van Weel C, van der Wilt GJ, Grol RP. Lower urinary tract symptoms: social influence is more important than symptoms in seeking medical care. BJU international. 2002;90:655–661. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410X.2002.02996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gottesman O, et al. The Electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE) Network: past, present, and. future. Genetics in medicine: official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2013;15:761–771. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.McCarty CA, et al. The eMERGE. Network: a consortium of biorepositories linked to electronic medical records data for conducting genomic studies. BMC medical genomics. 2011;4:13. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Price AL, et al. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Abraham G, Inouye M. Fast principal component analysis of large-scale genome-wide data. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Delaneau O, Marchini J, Zagury JF. A linear complexity phasing method for thousands of genomes. Nat Methods. 2012;9:179–181. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Howie BN, Donnelly P, Marchini J. A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2190–2191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mele M, et al. Human genomics. The human transcriptome across tissues and individuals. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2015;348:660–665. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa0355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the eMERGE dbGAP repository (accession phs000888.v1.p1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs000888.v1.p1).