ABSTRACT

Neurological conditions present a challenge when obtaining consent for lumbar punctures (LPs), as patients often have visual, hearing or cognitive impairments. The aim of this project was to improve the quality of the consent process for LPs. Surveys of doctors and patients suggested there was scope to standardise and improve information provided during the consent process. A patient information video was developed using online software and shown to patients using tablet computers. Patient surveys were distributed to re-assess the quality of the process for obtaining consent. There was a significant improvement (p=0.031) in the median response score after the video was presented to the same group of patients. The use of patient information videos significantly improves understanding and recall of the procedure, and satisfaction with the consent process. In conclusion, audio-visual tools are a valuable tool for standardising and improving the process of gaining consent for LPs.

KEYWORDS: Audio-visual, consent, lumbar puncture, patient information, video

Introduction

Problem description

Our hospital is a tertiary referral centre treating 6,000 inpatients, 8,000 day cases and 120,000 outpatients per year. As part of their diagnosis or treatment, patients with neurological conditions often require investigation and analysis of cerebrospinal fluid through a lumbar puncture (LP). While the risks of a LP are low, they can be potentially serious and, therefore, it is important that patients understand the implications, benefits and potential side effects of the procedure. Despite LP being one of the commonest investigations performed at our hospital, there was no standardised information provided to patients prior to the procedure.

Available knowledge

Anecdotally, we suspected there was variable practice for obtaining consent and therefore information provided to patients was also variable. Although little literature exists in this subject for adult inpatients, suboptimal practice in documentation of explanation and lack of supporting information given to patients has been found with LP consent in emergency departments.3

Rationale

Valid consent is vital in order to comply with the General Medical Council's guidance Good medical practice1 and they have produced additional guidance on obtaining consent, which specifies that it is important to ‘share the information in a way that the patient can understand’.2 The use of supplementary information (leaflets or audio-visual information) is encouraged. At our unit, there were no audio-visual resources for patients explaining this procedure.

Aim

The aim of this project was to assess the effect of a patient information video on patient feedback scores (via a visual analogue scale) on pre-lumbar puncture consent experience.

Methods

Context

To assess the scale of the problem, an anonymous survey of the current practice for obtaining consent was distributed among 17 neurology doctors (seven core medical trainees, one neurosurgical trainee, six registrars and three consultants) at a single centre that performs LPs routinely. Of the 17 doctors surveyed, 47% consented verbally and wrote in the notes and 30% used a trust consent form. 18% provided supplementary materials (eg information leaflets). There was wide variation in the content of information (including percentage of risks) being provided by doctors.

A prospective single-centre survey of understanding of a LP was then performed. All patients involved in this study were deemed to have capacity to consent to both LP and inclusion in the survey. Patients who were unable to provide valid consent because of such severe cognitive deficits were excluded.

Ten patients rated their understanding of LP and experience of the consent process using a visual analogue scale where zero was ‘totally disagree’ and 10 was ‘completely agree’. The six statements they rated were:

I understand the reason for this procedure.

I understand what the procedure will involve.

I understand the risks of this procedure.

I am able to recall the information given to me regarding this procedure.

I would be able to explain this procedure, and the risks and benefits to someone else.

My questions regarding the procedure were sufficiently explained.

From this initial patient survey, the median score for understanding what an LP involved (Q1), reasons for performing it (Q2), the associated risks (Q3) and recall (Q4) was 8.5. The median score for being able to explain to another person (Q5) was 6.7. The median score for satisfaction with questions being sufficiently answered (Q6) was 8.2.

The results from the doctor and patient survey suggested that there was scope to standardise and improve the quality of the information being provided during the process of obtaining consent for LPs.

Intervention

As patients with neurological conditions may often have a coexisting visual disturbance, hearing impairment or cognitive impairment, the use of video to explain the procedure was suggested because of its multisensory nature. Generic videos on LP can be found online but these are generally directed towards educating clinicians rather than the lay person and are often of poor quality,4 so we decided to design our own.

A patient information video was developed through online software (GoAnimate © 2015). The patient information video covers the journey of a patient who undergoes an LP and addresses the risks and benefits of the procedure using non-jargon language. A storyboard is shown in Fig 1. A grant from the Small Acorns Fund enabled the purchase of three tablet computers (iPad mini 4 © 2015 Apple Inc) for the development and distribution of the patient information video. This video was built by the authors, who are all practising clinicians. The video can be viewed at www.youtube.com/watch?v=zwlW09BXtEM

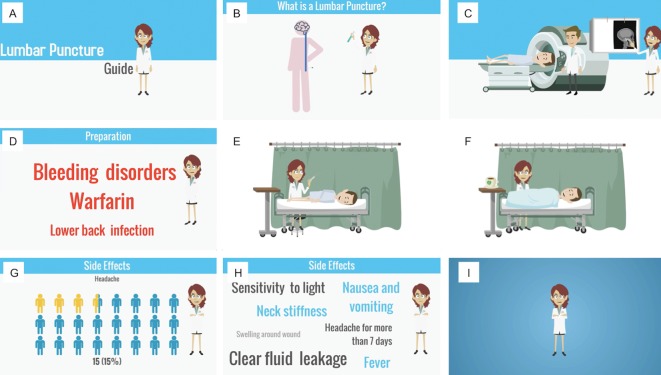

Fig 1.

Storyboard of patient information video. A – introduction to the Lumbar Puncture Guide. B – basic overview of the procedure and why the neurologists are considering this test. C – what is done to prepare for the procedure (CT scan, blood tests and where to attend). D – what can be done before the procedure and what would prevent you having the lumbar puncture (LP). E – what happens during the LP. F – what to do immediately after the LP. G – risk of side effects (%). H – potentially serious side effects requiring further medical treatment. I – confirmation that this is a routine procedure and where, when and how the test results are provided. Patients are then directed to discuss any concerns or questions with the doctor during the consent process.

Measures

The video went through three plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles.

PDSA Cycle 1

The video underwent two rounds of feedback from two focused governance meetings (two secretaries, one head of governance, two specialist nursing staff, two consultants and two junior doctors), in addition to general feedback collected at a governance meeting (over 50 multidisciplinary personnel working at the trust).

PDSA Cycle 2

A verbal pilot survey was performed at a patient focus group (n=4) of those who had previously had an LP. Verbal responses included ‘the background screen was very bright’, ‘the music is too loud to hear the voice’, ‘the experience portrayed in the video is correct’ and ‘more emphasis on headache as a side effect’. These four statements were repeated from the patients independently. The content of the video was subsequently adjusted as was screen brightness and sound volume.

PDSA Cycle 3

A post-intervention prospective analysis was performed to assess subjective patient understanding. A new group of 11 patients were interviewed before and after exposure to a patient information video using the same six survey statements as in the baseline analysis. Five patients were randomly allocated to group A (verbal explanation and video observation) and six were allocated to group B (video only). Patients were given an hour to consider the video and its content prior to completing the feedback form. The video was not supplemented with written material but subtitles were provided on screen.

Analysis

Survey responses were processed using Microsoft Excel. A Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test was used to determine the statistical significance between the before and after video median scores for each statement. A Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test was also used to determine if there was any significant difference between the median score for each statement for those shown the video with a verbal explanation from a physician (group A) and those only shown the video (group B). All statistical tests were performed on GraphPad Prism 6.0c.

Results

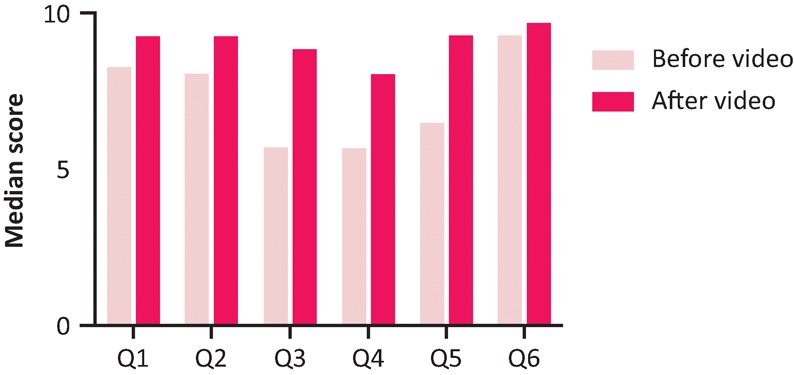

Eleven patients were surveyed for the post-intervention analysis (6 Males; 5 Females) with a mean age of 53.1 years (range 29–79 years). The results of PDSA cycle 3 showed that all six statements (covering understanding, rationale, risks, recall, and satisfaction with explanation) demonstrated an improvement in median score. There was a significant improvement (p=0.031) in the median response score per statement after the patient information video was presented (to the same group) (Fig 2). However, there was no significant difference (p=0.313) in the response to the statements in group A (exposed to the video and a verbal explanation) compared with group B (exposed to the video only).

Fig 2.

Median scores on the visual analogue scale before and after viewing the patient information video. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test p=0.0313. Q1 – I understand the reason for this procedure. Q2 – I understand what the procedure will involve. Q3 – I understand the risks of this procedure. Q4 – I am able to recall the information given to me regarding this procedure. Q5 – I would be able to explain this procedure, and the risks and benefits to someone else. Q6 – My questions regarding the procedure were sufficiently explained.

Discussion

Summary

The process of gaining consent was found to be highly variable among doctors, despite LP being common in this institution. The use of patient information videos significantly improved the subjective understanding of the procedure and improved the subject's recall and satisfaction with the consent process. Furthermore, use of a video enables a degree of standardisation in information being provided to patients.

Interpretation

Patient understanding of the procedure may have improved for several reasons. Firstly, the video provides multisensory information – thus addressing issues secondary to visual or hearing impairment, which are common in a neurological hospital – and is presented in a format that makes the information easily comprehensible. Secondly, it improves patient autonomy by allowing the information to be provided at a time and location convenient to the patient. Finally, it can be repeated and paused, thus enabling the patient to consider the information fully, even in the presence of cognitive impairments or memory disturbances.

Interestingly, the verbal explanation in addition to the video did not significantly improve patients understanding. Despite this finding, we do not advaocate replacing the consent discussion with videos and the authors strongly recommend a doctor is present (in addition to the use of video) to ensure any questions the patients have can be properly addressed before they give consent.

Limitations

The authors recognise the limitations that targeted subjective questionnaires present – while a patient reports having a good understanding of a procedure, this might not actually be the case. This concept is not limited to this study but the practice of obtaining consent in general. Testing patients’ understanding through mini exams may become an objective measure to ensure proper consent is obtained. With hindsight, it would have been valuable to consult the patient focus group prior to the video development, rather than during the mid-development phase.

Further research

We plan to develop a range of patient information videos for various procedures. While all patients in this study spoke and read English fluently, this video will be translated into several common languages (both verbally and with translated subtitles). As part of a future study, we will be conducting more detailed feedback on the long-term effect of using videos to supplement the consent process and the impact it has on both patient and doctor experience. In this future study, we will include those with more severe cognitive deficits. Finally, it would also be of value to determine the impact of information videos on overall patient satisfaction with their treatment.

Conclusions

Development of further distributable patient information via tablets and online resources is likely to become a normal part of patient consent. Such videos could be uploaded to the internet and shared to patients via smart phone devices. It is possible that the use of a short mini-quiz or test integrated into videos to objectively confirm understanding, may become a normal part of the consent process.

Learning points

Obtaining consent for ward-based procedures, such as lumbar puncture, is often variable and needs to be better standardised.

Use of portable, repeatable, audio-visual information on a procedure can significantly improve a patient's subjective understanding and recall and is therefore is a valuable tool in gaining informed consent.

Conflicts of interest

The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organisation or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this article. The Small Acorn's charity grant enabled the purchase of the tablets for use at author's institution.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Catherine Wilson, Dr Michael Lunn and Prudence Harding for their feedback and support with governance. The authors would also like to acknowledge the team of junior doctors (Stephen Mounsey, Viorica Chelban, Andrew Fox-Lewis, Sandra Elfons-Tawafig, Sion Williams, Sam Shribman, David Foldes and Zeinab Abdi) who assisted in the patient and doctor feedback collection.

Ethical approval

This project was exempt from ethical approval as it was an improvement study posing no risks to participants.

References

- 1.General Medical Council Good medical practice. London: General Medical Council, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.General Medical Council Consent guidance: patients and doctors making decisions together. London: General Medical Council, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel PB, Anderson HE, Keenly LD, Vinson DR. Informed consent documentation for lumbar puncture in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med 2014;15:318–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossler B, Lahner B, Schebester K, Chiari A, Plochl W. Medical information on the Internet: Quality assessment of lumbar puncture and neuroaxial block techniques on YouTube. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2012;114:655–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]