ABSTRACT

Shared decision making and support for self-management are among a range of approaches that have been developed over the last 20 years to fundamentally change the relationship between health professionals and patients. They have strong synergies and address the inequalities of the current relationship. They replace this with a partnership approach in which health professionals and patients work together to identify and enact decisions and plans that are jointly agreed on the basis of both medical evidence and what matters most to individuals. To do this effectively requires the development of new ways of working based on a culture of collaborative working, skills that support patients to think through and articulate preferences, and the development of systems and tools that make it easier to do this. There is already a body of practice that helps to identify what needs to be done and this practice now needs to be extended across the healthcare system

KEYWORDS: Shared decision making, support for self-management, person-centred care, clinical interactions

Introduction

In its 2012 position statement, the Royal College of Physicians set out that ‘shared decision making (SDM) and support for self-management (SSM) refer to a set of attitudes, roles, and skills, supported by tools and organisational systems, which put patients and carers into a full partnership relationship with clinicians in all clinical interactions’.1 While SDM principally relates to specific, time- and context-dependent health decisions and SSM to living with a long-term condition (LTC), they share common themes as part of person-centred care (PCC) or partnership working. This article explores what these themes are, the reasons why they have become increasingly important for clinicians and some of the key drivers and barriers to their adoption.

Current attitudes and practice in relation to SDM and SSM

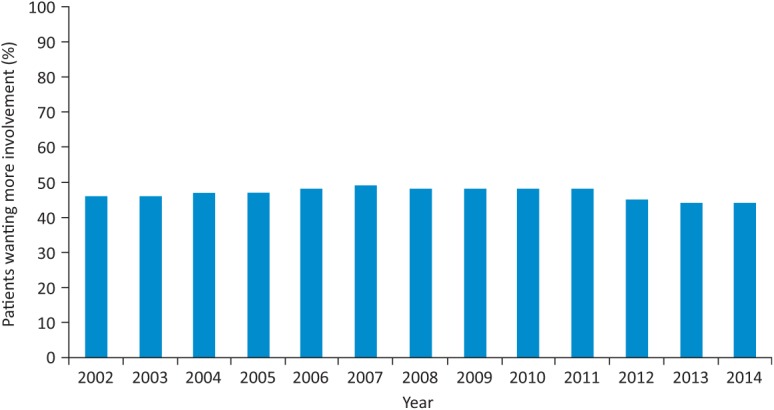

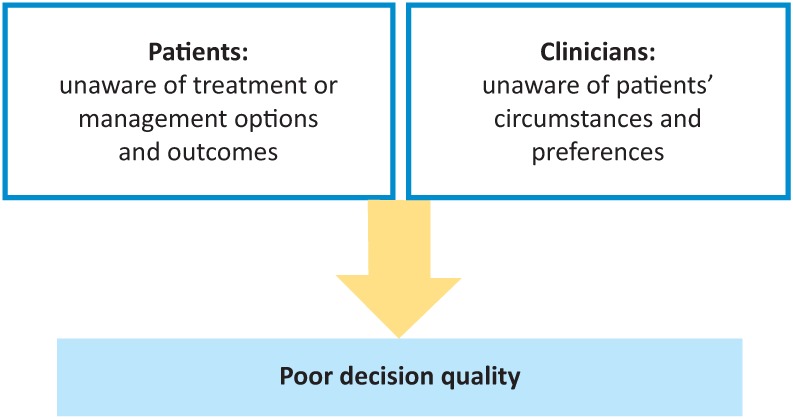

Only about half of patients report feeling as involved in decisions and plans about their care as they want, both in primary care and hospital settings.2–4 This has changed little for the last decade or more (Fig 1). In contrast, over 80% of clinicians feel they involve people in their own care;5 this mismatch gives rise to frustrations. Conscientious and committed clinicians feel they are working hard for their patients and are unsure why their recommendations often aren’t followed, their patients’ outcomes aren't as good as they should be and patients seem dissatisfied. At the same time, patients don’t feel involved and listened to,3,4 services are burdensome, disempowering and difficult for them to navigate, and they often feel that things are being done ‘to’ them rather than ‘with’ them. Fig 2 illustrates the dilemma that many clinicians and patients face. Clinicians are unaware of the values, preferences, personal factors and priorities of patients, whereas patients are unaware of the options and evidence that might influence their health outcomes. The outcome is decisions and plans that are less successful than they could be when compared with evidence, and levels of satisfaction that are patchy at best, resulting in wasted time, resources and opportunity.

Fig 1.

Trends in inpatient involvement in decisions about care 2002–2014.4

Fig 2.

The clinical decision problem. Adapted from the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation with thanks to Angela Coulter and Alf Collins.

Key themes involved in SDM and SSM

At the heart of SDM and SSM is the belief that people have an interest in living well when they have a health problem and that where they are involved as partners:

-

bull

better decisions and plans are made that have higher acceptability to the patient and the clinician6

-

bull

decisions and plans are more appropriate for the patient as an individual and more likely to be enacted7

-

bull

any support that is needed is more likely to be be identified and provided

-

bull

the patient is more likely to achieve outcomes that both the patient and clinician want7

-

bull

there may be better use of resources, less waste and greater safety.8,9

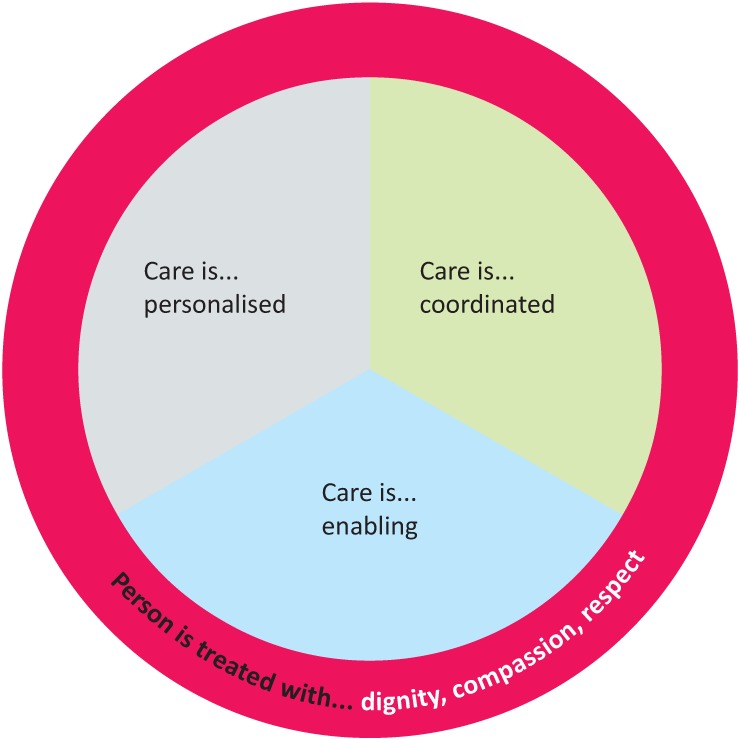

For this approach to be implemented, a number of key components are required.10,11 From a patient perspective, care needs to be personalised, coordinated and enabling, at the same time as treating the person with dignity, compassion and respect (Fig 3).10 From the perspective of clinicians and service delivery, three key areas need to be addressed for this to become a reality.

Fig 3.

Principles of person-centred care.10

Attitudes and roles

The delivery of healthcare has become more complex. This has contributed to an unequal power relationship between patients and clinicians, based on the clinicians’ knowledge of disease and access to treatments. For patients to become truly involved in their care, there needs not only to be recognition that current clinical interactions, which maintain the status quo, are sub-optimal but also a desire for change.

One way of thinking about this is to recognise that, outside of health settings, we all make significant decisions and plans, such as going on holiday or buying a car. This is generally done using a combination of sources of information and experience, seeking advice and taking into account personal preferences. Technical expertise is a part, and not always the most critical part, of this process. As a result, different people make different decisions in apparently similar situations.

In the same way, patients have individual views about health decisions. These may be influenced by knowledge, experience, personal situation, preferences, capabilities, values or beliefs; clinicians cannot predict what these influences are. So to understand them, they must be actively solicited. Failure to do this leads to poorer acceptance of decisions as well as difficulty, disinclination or discontent in adopting them.

For clinicians, this requires active invitation to patients to become equal partners based on recognising what they themselves bring to clinical interactions. Valuing the outcomes that matter most to the individual is then needed for good decisions and plans, even where those outcomes may not be the ones that matter most to the clinician.

Patients also need to adapt to the changing purpose, content and dynamic of consultations. They should expect involvement as a normal part of care. Societal changes, including the digital revolution, mean that these expectations are already growing13,14 and health professionals need to catch up.

Skills

Changes in attitudes and roles require clinicians to use and develop clinical skills differently so that consultations become truly collaborative. Some of these have to do with the consultation itself (core communication skills, motivational interviewing and coaching skills), while others have to do with teamwork, leadership and coordination of services to meet the needs of individuals and address fragmentation of care. Many of these skills are taught in undergraduate and postgraduate curricula but, critically, need to be used in tune with a culture of partnership working.

Tools and organisational systems

There is a good deal that can be done to support the attitudes, culture and skills of partnership working. It is helpful in thinking about these to recognise that there are some aspects that have to do with the wider health system, some that relate to the process that people need to navigate during health interactions, and some that have to do with the consultation itself.

The wider health system

The Wagner Chronic Care Model15 identifies that there are key population and community dimensions to successful healthcare delivery: policy and health planning, national standards (such as professional standards and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance), workforce and delivery, funding arrangements, and local and regional healthcare delivery planning all need to be aligned to make it easier to ‘do the right thing.’

Local processes

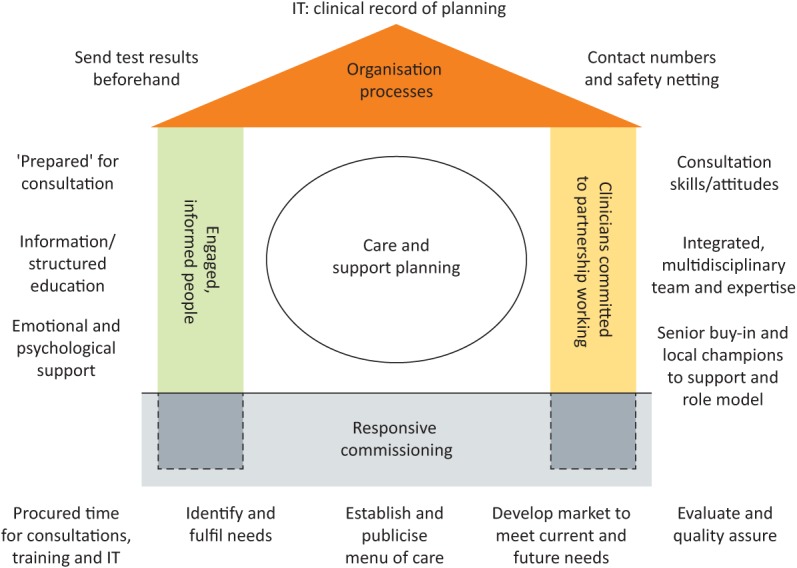

Within local health communities, a considerable amount can be done to enhance partnership working with patients. The House of Care (Fig 4), developed as a part of the Year of Care Programme,11,12 is being widely used in England and Scotland to do just this. It acts both as a metaphor and a checklist for the planning and delivery of care and support planning. As a metaphor, it identifies the key areas that contribute to partnership working; as a checklist, it helps to identify, quite specifically, what is already in place locally and what still needs to be developed for partnership working to become a reality. While it was developed principally for use in the context of LTC and SSM, the same key questions can be asked in relation to SDM (ie ‘what is needed for people to become fully involved in decisions about their health?’, ‘what is needed for clinicians to be fully committed to partnership working?’, and ‘what else in relation to systems, assets or resources is needed to support this?’). This can be applied, for example, to the redesign of patient pathways so that patients are better able to make decisions at key points, while also identifying what professionals and teams can do to support this.

Fig 4.

The House of Care. Each health community generates its own understanding of what is needed for engaged and informed patients and clinicians committed to partnership working, with supporting organisational processes and commissioning. This acts as the basis of a local action plan to enable care and support planning to take place.

The consultation

People benefit from a clear ‘road map’ for their care so that they can navigate the process of planning and decision making in a health setting. Patient decision support tools and patient decision aids (PDAs) for a number of specific decisions,16 and care and support planning prompts for long-term conditions, multimorbidity and frailty11 have been developed to enable people to be more involved in decisions and plans about their care. A key aspect of these is recognising that people benefit, wherever possible, from information in advance of clinical interactions to help them think through the purpose, content and potential outcomes. This can save time within consultations and enables a consistency of approach between clinicians dealing with the same issues. It also, critically, gives people time to think through what both the condition and the options mean for them, as well as acting as a starting place for discussion. Once plans have been made people may need other support within the health system, community or third sector, to address personal needs alongside health needs. Teams need to be aware of these and how they can be accessed.

Drivers and barriers to adoption

As mentioned, cultural and societal changes are driving a need to re-think the way we deliver healthcare so that it becomes more collaborative. For most people there is easier access to information, including health information. At the same time, fragmentation of care, increasing health complexity in an ageing population, and the difficulties in expressing risk and benefit in relation to myriad health choices all put patients at a disadvantage. The recognition of this has led to successive health policy intent, from the NHS Plan in 2000,17 through the NHS mandate’s guidance on commissioning to the Five Year Forward View in 2014.18 These have all emphasised the need to involve patients and carers much more, and to develop plans for their care ‘with’ them rather than ‘for’ them in a way that gives weight to their preferences and priorities. Meanwhile, evidence of the benefits of this approach is growing, including a series of Cochrane reviews of SDM, SSM and care planning.19–21

For some time, collaborative consultations with patients have been a professional requirement for doctors in terms of General Medical Council standards.22 Since April 2015, a legal precedent23 also obliges health professionals, at least in the context of consent, not simply to advise on the professional view of what may be the best option for an individual, but to provide information and support to the person to weigh all reasonable options in light of their own preferences and circumstances when arriving at a health decision.

Despite this there are barriers at every level. In terms of attitudes and roles, some clinicians find the idea of partnership working disconcerting. Others feel that ‘we do that already’ despite evidence to the contrary. We are still at the stage of learning what skills we need as clinicians and how to apply them to be competent at partnership working. There is a dearth of consistent high quality tools for patients to access, and those that we already have become dated quickly. Many of the clinical systems and processes that we employ seem to be designed more to make the systems and processes work better than to support real collaboration with patients in their decisions and plans. It is therefore encouraging that increasing numbers of clinicians, professional representative bodies, including royal colleges, health charities and voluntary organisations, and patient representative bodies, stimulated and supported by the work of organisations such as the Health Foundation, the King’s Fund and Nesta, are making this a priority.

The Royal College of Physicians has worked hard to understand what this means for physicians in particular1 and has put this at the heart of the Future Hospital Programme. Specialist physician groups, and individual members and fellows have been stimulated to work through what this means for their practice, workshops have been developed to support this, and a community of interest has emerged. Work has been carried out to consider how skills and attitudes can be tested through clinical examinations, and the next step is to clarify these in undergraduate and postgraduate medical curricula.

Summary and next steps

Working in partnership with patients makes sense at every level. After more than a decade of policy aspiration, a start is being made and evidence is growing that it makes a real difference. It requires a change in attitudes, skills and systems to become part of normal practice and there is still a long way to go.

We now have a clearer understanding of what isn’t working, why it isn’t working, and what we want to achieve. There is also an accumulating body of practice that helps us to understand how we can go about changing what we do in a coherent way and the benefits of this. There is now a need for a determined and consistent will to put what we know into practice more widely across the system.

References

- 1.Royal College of Physicians Personalising healthcare: the role of shared decision making and support for self-management. RCP position statement London: RCP, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Commission Healthcare. Managing Diabetes: improving services for people with diabetes. London: Healthcare Commission, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ipsos MORI. The GP Patient Survey 2015. London: Ipsos MORI, 2015. Available at https://gp-patient.co.uk/surveys-and-reports [Accessed 29 April 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Care Quality Commission Adult inpatient survey 2014. Newcastle: CQC, 2014. Available at www.cqc.org.uk/content/inpatient-survey-2014 [Accessed 29 April 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coulter A. Engaging patients in healthcare. Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hacking B, Wallace L, Scott S, et al. Testing the feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of a ‘decision navigation’ intervention for early end stage prostate cancer patients in Scotland – a randomised controlled trial. Psycho-Oncology 2013;22:1017–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff 2013;32:207–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nesta The business case for people powered health. London: Nesta, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.York Health Economics Consortium. Evaluation of the Scale, Causes and Costs of Waste Medicines. York: York Health Economics Consortium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Health Foundation Person-centred care made simple. London: The Health Foundation, 2014. Available at www.health.org.uk/publications/person-centred-care-made-simple [Accessed 29 April 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Year of Care Available at http://www.yearofcare.co.uk [Accessed 29 April 2016].

- 12.Eaton S, Roberts S, Turner B. Delivering person centered care in long term conditions. BMJ 2015;350:h181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voices National. Care and support planning. London: National Voices, 2013. Available at www.nationalvoices.org.uk/pages/care-and-support-planning [Accessed 29 April 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards T, Coulter A, Wicks P. Time to deliver patient centred care. BMJ 2015;350:h530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q 1996;74:511–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.BMJ Group NHS right care decision aids. London: BMJ Group, 2012. Available at http://sdm.rightcare.nhs.uk/pda/ [Accessed 29 April 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 17.NHS The NHS plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: Stationary Office, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.England NHS. Five year forward view. NHS England, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Légaré F, Stacey D, Turcotte S, et al. Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(9):CD006732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galdas P, Fell J, Bower P, et al. The effectiveness of self-management support interventions for men with long-term conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coulter A, Entwistle VA, Eccles A, et al. Personalised care planning for adults with chronic or long-term health conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;(3):CD010523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.General Medical Council Consent: patients and doctors making decisions together. London: GMC, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montgomery (Apellant) v Lanarkshire Health Board (Respondent) (Scotland) [2015]UKSC 11. [Google Scholar]