ABSTRACT

There is growing evidence that outcomes in sepsis are improved by early recognition and treatment. In this study, we assessed junior doctors’ ability to recognise and manage sepsis. We also explored junior doctors’ perceptions regarding barriers to delivering timely sepsis care. From 46 respondents, only 4% were able to list the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria, 50% could define sepsis and 46% could list the Sepsis Six. Following further teaching on sepsis, 35% could list the SIRS criteria, 87% correctly defined sepsis, and 91% could state the Sepsis Six. Junior doctors perceived time pressure when on call to be the greatest barrier in treating sepsis, and their own knowledge to be the least important barrier. Our data suggest that knowledge of sepsis among junior doctors is poor and that there is a lack of insight into this competency gap.

KEYWORDS: Sepsis, Sepsis Six, foundation training, education

Introduction

There is growing recognition that sepsis causes significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. Mortality rates are quoted at 10% for patients with uncomplicated sepsis, 35% for severe sepsis and 50% for septic shock.1 In the UK, approximately 4.3% of all patients attending the emergency department fulfil the criteria for sepsis,2 and it causes approximately 37,000 deaths each year.3

In recent years, there has been a drive to protocolise the initial management of sepsis, aiming to reduce the number of preventable deaths.4 The Royal College of Physicians toolkit for sepsis management5 focuses on three components: early recognition, early intervention and timely escalation. In practice, this requires a high clinical suspicion of sepsis and early activation of the Sepsis Six; a set of interventions shown to reduce sepsis mortality by 40% if delivered within 1 hour (Box 1).6

Box 1.

Sepsis definitions and the Sepsis Six. Gold standard against which responses were scored (2001 International Sepsis Definitions Conference).9

SIRS

|

| Sepsis: |

| Suspicion of infection with two or more SIRS criteria. |

| Severe sepsis: Sepsis with organ dysfunction. |

| Septic shock: Sepsis with hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation. |

The Sepsis Six (to be completed within 1 hour):

|

For SIRS criteria, an answer of tachycardia was marked partially correct whereas heart rate >90 bpm was marked fully correct. SIRS = systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

Despite increased focus on sepsis management, national compliance with the Sepsis Six has been slow to improve.7 This is likely to be multifactorial but may partly reflect the ability of junior doctors to consider the possibility of sepsis and initiate management.

In this study, we assessed the ability of junior doctors to recognise sepsis through recall of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria, sepsis definitions and the Sepsis Six. A recent study has shown that 47% of all hospital inpatients fulfil two or more SIRS criteria at least once during their hospital stay; this very high incidence may limit the value of SIRS criteria in screening for sepsis among inpatients.8 However, SIRS criteria will have been taught to the current cohort of junior doctors as a means of identifying sepsis and are widely used in sepsis identification tools. We have therefore included SIRS as one element of sepsis knowledge in the current study. We also explored what factors junior doctors felt impaired their ability to care for patients with sepsis. Further, the impact of a single teaching session on recognition and management of sepsis was assessed.

Methods

A questionnaire designed by the authors (sepsis questionnaire, S1) was distributed to all foundation year 1 (FY1) doctors and senior house officers (SHOs; a mixture of foundation year 2 and CT1 core medical trainees) attending a weekly teaching session in a district general hospital. Doctors were from a variety of different specialties. Questions tested knowledge of the SIRS criteria; definitions of sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock; and the Sepsis Six. Responses were assessed against definitions set by the 2001 International Sepsis Definitions Conference (Box 1).9 Participants were also asked to rank a list of potential barriers to sepsis care from most to least important.

Table 1.

Knowledge and recognition of sepsis. The number of respondents answering at least partially correctly for each question (percentage of respondents).

| Existing junior doctors, n (%) | New FY1s, n (%) | Comparison of new FY1s before and after teaching | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY1 | SHOs | Before teaching | After teaching | p-value | |

| Total number of respondents | 12 | 11 | 23 | 23 | |

| SIRS criteria | |||||

| HR > 90 | 9 (75) | 10 (91) | 20 (87) | 22 (96) | 0.608 |

| RR > 20 | 9 (75) | 10 (91) | 16 (70) | 23 (100) | 0.009 |

| Temp > 38.3 | 11 (92) | 9 (82) | 22 (96) | 23 (100) | 1.000 |

| Temp < 36 | 9 (75) | 4 (36) | 12 (52) | 19 (83) | 0.057 |

| WCC < 4 | 4 (33) | 1 (9) | 6 (26) | 15 (65) | 0.017 |

| WCC > 12 | 8 (67) | 3 (27) | 12 (52) | 18 (78) | 0.234 |

| BM > 7.7 | 1 (8) | 1 (9) | 2 (9) | 19 (83) | <0.001 |

| Altered conscious state | 1 (8) | 5 (45) | 0 (0) | 19 (83) | <0.001 |

| All SIRS correct | 1 (8) | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 8 (35) | 0.004 |

| Sepsis definitions | |||||

| Sepsis | 7 (58) | 6 (55) | 10 (43) | 20 (87) | 0.005 |

| Severe sepsis | 1 (8) | 3 (27) | 9 (39) | 22 (96) | <0.001 |

| Septic shock | 3 (25) | 2 (18) | 2 (9) | 18 (78) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis Six | |||||

| Oxygen | 11 (92) | 7 (64) | 17 (74) | 23 (100) | 0.022 |

| IV antibiotics | 12 (100) | 11 (100) | 20 (87) | 23 (100) | 0.233 |

| IV fluids | 12 (100) | 11 (100) | 19 (83) | 22 (96) | 0.346 |

| Lactate | 10 (83) | 11 (100) | 12 (52) | 22 (96) | 0.002 |

| Blood cultures | 11 (92) | 11 (100) | 20 (87) | 23 (100) | 0.233 |

| Urine output | 9 (75) | 8 (73) | 13 (57) | 23 (100) | 0.001 |

| Time = 1 hour | 11 (92) | 9 (82) | 8 (35) | 21 (91) | <0.001 |

| All Sepsis Six correct | 8 (67) | 4 (36) | 9 (39) | 21 (91) | <0.001 |

BM = blood glucose; FY1 = foundation year 1; HR = heart rate; RR = respiratory rate; SHO = senior house officer; SIRS = systemic inflammatory response syndrome; WCC = white cell count.

Having identified lack of knowledge among junior doctors as one factor limiting sepsis care, a new intake of FY1 doctors were given teaching on sepsis during their induction. The 1-hour teaching session (delivered to groups of 12 by one of the authors) comprised a brief lecture on sepsis followed by an interactive case discussion focusing on opportunities for early intervention.

Knowledge of the new FY1 doctors was tested before and immediately after the teaching session using the questionnaire previously given to the junior doctors (although they were not asked to comment on barriers to sepsis management). The results before and after the teaching intervention (for the new FY1s only) were compared using Fisher’s Exact test. A statistically significant effect was accepted when p<0.05.

Results

Knowledge and recognition of sepsis

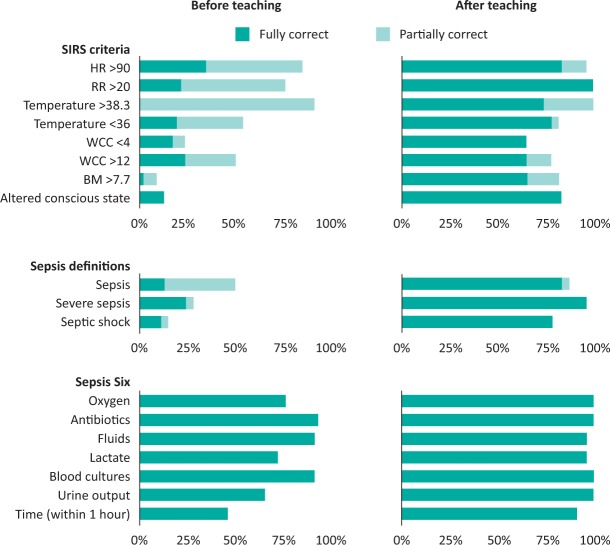

Responses were gathered from 23 existing junior doctors (12 FY1 and 11 SHOs) and subsequently from 23 new FY1 doctors. Only 4% of respondents correctly listed all of the SIRS criteria. Pyrexia, tachycardia and tachypnoea were each identified by over 75% of respondents as SIRS criteria, although knowledge of the precise thresholds was poor. The other SIRS criteria were less commonly identified (Fig 1). Many junior doctors incorrectly listed markers of organ dysfunction among the SIRS criteria, including hypotension (cited by 56%), oliguria (20%), elevated lactate (11%) and hypoxia (9%).

Fig 1.

Knowledge and recognition of sepsis by junior doctors. Data show foundation doctors’ responses to SIRS criteria, sepsis definitions and the Sepsis Six before and after a targeted sepsis teaching session. BM = blood glucose; HR = heart rate; RR = respiratory rate; SIRS = systemic inflammatory response syndrome; WCC = white cell count.

50% of junior doctors could at least partially define sepsis, with 28% and 15% able to define severe sepsis and septic shock, respectively.

Junior doctors appeared to be more familiar with the Sepsis Six care bundle and 46% of respondents were able to list all six interventions correctly. Intravenous antibiotics, intravenous fluids and blood cultures were each cited by over 90% of respondents. 61% recognised the need to complete these interventions within 1 hour.

Teaching session and repeat questionnaire

Following a teaching session on sepsis for new FY1 doctors, all measures were improved. 35% could list all six SIRS criteria, 87% correctly defined sepsis, and 91% could list the Sepsis Six (Fig 1). When compared to results from the same group before the teaching session, the number correctly listing all SIRS criteria; correctly defining sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock; and correctly listing all of the Sepsis Six were all significantly improved (Table 1, p<0.05).

Barriers to sepsis management

Qualitatively, junior doctors ranked ‘time pressure on call’ as the most significant barrier to sepsis care, followed by the time to deliver antibiotics and fluids. The factor most commonly cited as the least important barrier to sepsis management was the doctors’ own knowledge and recognition of sepsis (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Barriers to sepsis management as cited by junior doctors. Current foundation year 1 doctors and senior house officers were asked to rank pre-selected potential factors as perceived barriers to implementing the Sepsis Six.

Discussion

It is clear that timely management of sepsis saves lives and reduces morbidity.6 This relies on prompt recognition and definitive management by the healthcare team. Here we show that junior doctors are not able to recall the key SIRS criteria that enable recognition of sepsis. We found a poorer knowledge of sepsis than previous studies have suggested.10 One explanation is that we tested participants’ recall of sepsis criteria and definitions without prompting whereas the previous study asked participants to state the diagnosis for fictitious medical cases. Other differences include the seniority of doctors studied (more junior in the current study) and involvement of more intensivists in the earlier study (who were observed to perform better).

There was inadequate appreciation of the difference between sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock. Many junior doctors thought that hypotension, oliguria, elevated lactate and hypoxia were SIRS criteria, when actually these all indicate end-organ dysfunction and, therefore, severe sepsis. Junior doctors may see patients with sepsis so frequently that they normalise the signs of sepsis and only respond urgently to signs of severe sepsis or septic shock. This hypothesis is supported by a recent study, which found that almost half of ward patients fulfilled two SIRS criteria simultaneously at least once during their admission.8 This raises the possibility that patients with sepsis are only recognised after they develop organ dysfunction and opportunities for early intervention are missed.

Junior doctors identified time pressure on call and the timely delivery of fluids and antibiotics as the top barriers to sepsis care. Out-of-hours junior doctors often deal with multiple sick patients, limiting their ability to review deteriorating patients. A lack of senior support was also felt to be a major barrier to delivering care by junior doctors. There is currently a strong political focus on increasing consultant presence, particularly out of hours. In addition, the emergence of critical care outreach teams has been a welcome resource to support junior doctors in their clinical decision-making skills. In our hospital, as in others, the critical care outreach team have taken a leading role in managing patients with sepsis on the wards and reviewing deteriorating patients. They can also serve as a supporting link between junior doctors, their specialty seniors and the critical care environment.

Interestingly, while knowledge of sepsis among junior doctors was poor, there was also a lack of insight into this fact. Only 3 (out of 23) junior doctors identified their own knowledge as a major barrier to care while 9 cited it as the least important barrier. An interactive teaching session for new FY1 doctors significantly improved their recall of SIRS criteria, sepsis definitions and the Sepsis Six. Therefore this interventional study suggests that specific defects in knowledge can be addressed in the classroom environment with a good effect on recall. However, it is not possible to determine if this translates to improved clinical care or clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

Our results show that lack of knowledge among junior doctors is a significant barrier to improving patient care in sepsis. By delivering further teaching on sepsis to junior doctors in our hospital we have achieved a significant improvement in knowledge of sepsis.

Awards

This work has been recognised with a poster prize at the Royal College of Physicians Annual Conference, Harrogate, March 2015, and was awarded the East of England Deanery Quality in Education and Training Awards: Educational Intervention Project Poster of the Year 2014.

Supplementary material

Additional supplementary material may be found in the online version of this article at http://futurehospital.rcpjournal.org/ :

S1 - Sepsis questionnaire

References

- 1.Levy MM, Dellinger RP, Townsend SR, et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: Results of an international guideline-based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 2010;38:367–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cowan SL, Holland JAA, Kane AD, Frost I, Boyle AA. The burden of sepsis in the Emergency Department: an observational snapshot. Eur J Emerg Med 2015;22:363–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniels R. Surviving the first hours in sepsis: getting the basics right (an intensivist’s perspective). J Antimicrob Chemother 2011;66(Suppl 2):ii11–ii23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mouncey PR, Osborn TM, Power GS, et al. Trial of Early, Goal-Directed Resuscitation for septic shock. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1301–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Royal College of Physicians Acute Care Toolkit 9: Sepsis. London: RCP, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniels R, Nutbeam T, McNamara G, Galvin C. The sepsis six and the severe sepsis resuscitation bundle: a prospective observational cohort study. Emerg Med J 2011;28:507–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Royal College of Emergency Medicine Severe sepsis and septic shock: report of the clinical audit 2013–14. London: RCEM, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Churpek MM, Zadravecz FJ, Winslow C, Howell MD, Edelson DP. Incidence and prognostic value of the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome and organ dysfunctions in ward patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;192:958–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, et al. 2001. SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med 2003;31:1250–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Assunção M, Akamine N, Cardoso GS, et al. Survey on physicians’ knowledge of sepsis: Do they recognize it promptly? J Crit Care 2010;25:545–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]