ABSTRACT

The proportion of people with dementia in general hospitals continues to increase. Little attention has been paid to the impact of the physical environment of the hospital on their care. The King's Fund's Enhancing the Healing Environment programme worked with 26 NHS trusts in England to develop more supportive design for people with dementia. Projects ranged from improvements to ward environments and social spaces to the development of gardens. The evaluation found that relatively simple, cost-effective changes to the physical environment of care have positive effects on people with dementia and those using and working in the services. These include reducing agitation and distress and raising staff morale. From this work a set of design principles for dementia friendly design has been developed together with evidence based environmental assessment tools for hospital and ward environments. The tools are free to download and are being used extensively nationally and internationally.

KEYWORDS: Dementia-friendly, environment, design, assessment, evaluation

Introduction

Carers tell us time and time again that when it comes to hospitals, care homes or other settings, it's often the small things – whether clear signage, light and airy rooms or good handrails – that make a big difference

Secretary of state for health, October 2012

The environments in which we live and work have a profound influence on our physical and psychological well-being. In healthcare settings the environment has an important role to play in supporting clinical interventions. However, until relatively recently, little attention had been given to the specific challenges that general hospital environments can present to people with cognitive problems or dementia.

The report of the Royal College of Physicians’ Future Hospital Commission acknowledges the challenges presented to general hospitals in providing care for people with dementia.1 In describing the needs of patients in the 21st century, specific reference is made to the changing demographics of hospital inpatients and importance of high quality, holistic care for an increasing number of vulnerable patients. In building a culture of compassion and respect, recognised as essential in the report, the need for individualised care and shared decision making with carers is particularly important for people with dementia.

There has been a growing recognition of the part that a supportive environment can play alongside pharmacological and behavioural approaches in the care and treatment of people with dementia in care homes.2 In 2009, The King's Fund began work with 26 NHS hospital trusts to develop more dementia-friendly design. The projects were undertaken in a mix of locations, the majority of which were relatively new builds, and the results have shown that relatively straightforward, value-for-money changes can have a dramatic impact on hospital stays for people with cognitive problems and dementia. This article distils the learning from the programme and describes the development of the overarching principles for dementia-friendly design, together with the environmental assessment tools that are now in use internationally.

The need for dementia-friendly hospitals

In 2009, the Alzheimer's Society report Counting the Cost3 highlighted the detrimental effect of hospital stays on the independence of people with dementia, finding that dementia was associated with increased length of stay and poorer outcomes. The report estimated that over 25% of people accessing general hospital services are likely to have cognitive problems or dementia. This figure is now believed to be an underestimate, with hospitals reporting that nearer 40% of hospital patients aged over 75 years are affected, though many will not have received a formal dementia diagnosis.

Although significant progress has been made in the diagnosis and care of people with dementia in hospital settings since the publication of the national dementia strategy4 for England, the prime minister's Challenge on dementia,5 and the introduction of a specific Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) framework,6 there is still a significant knowledge gap about the critical role that relatively straightforward and inexpensive improvements to the built environment can play in improving care and supporting the well-being of people with dementia. Too many patients still lose their independence in undertaking activities of daily living while they are in hospital with the result that they are unable to return home when the acute episode of care is completed – an outcome that is both devastating for them and their families and has cost consequences for the care system.

However, the need for more supportive design for people with dementia in hospital is becoming more widely recognised. The Royal College of Psychiatrists’ report from the National Audit of Dementia in General Hospitals7 and the Royal College of Nursing's 2011 Commitment to the care of people with dementia in general hospitals8 both recognised the critical role of the physical care environment. The Call to Action,9 launched in 2012 by the Dementia Action Alliance (DAA) and the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, included improvements to the care environment as one of the strands of work to enhance the care of people with dementia in acute hospitals.

Hospital environments and people with dementia

Going into hospital is a potentially frightening and bewildering experience, with unfamiliar surroundings, noise and very busy spaces. For people with dementia who are generally, though not always, older people, and who may already have poorer sight and hearing, this experience can be exacerbated by the perceptual and visuospatial problems associated with dementias including Alzheimer's disease. These difficulties can lead to increased agitation, disorientation and distress; and people with dementia are likely to:

be confused and agitated in unfamiliar environments, particularly if they are visually over-stimulated, for example, by a plethora of signs and notices

be unable to see things, for example, handrails and toilet seats, if these are the same colour as the wall or sanitary ware

experience shadows or dark strips in flooring as a change of level and therefore try to step over them

resist walking on shiny floors because they think they are wet

want to explore and walk around.

However, if hospital environments are appropriately designed it is possible to reduce confusion and agitation, encourage independence and social interaction, and enable people with dementia to retain their ability to undertake activities of daily living.

Environments of care for people with dementia

Patients are at the centre of The King's Fund's Enhancing the Healing Environment (EHE) programme, which has supported over 250 multidisciplinary teams to improve care quality and support service change through high quality, innovative, value-for-money environmental improvements. Clinical leadership, patient involvement and estates support have been critical to the success of the individual projects in acute and community hospitals, mental health units, hospices and prisons in England.

In 2009, the Department of Health commissioned a specific EHE programme that focused on developing more supportive design for people with dementia in hospitals. All team members received training in design principles and the use of colour, light and art prior to starting their scheme. 26 projects were completed in acute, community and mental health settings.10 The schemes were chosen to provide exemplars capable of wide replication, with local adaptation, across the service. The projects ranged from the redesign of memory clinics, outpatient waiting areas, dining rooms and social spaces to ward improvements and the provision of palliative care facilities.

Initial visits to project sites showed that even in relatively new hospital buildings it was common to find poor signage; lack of intuitive cues and little purposeful use of colour and contrast to aid way-finding; poor lighting, leading to glare and light pooling; shiny floor surfaces that could look wet or slippery; clutter and distractions; stark, unwelcoming spaces including featureless corridors; a lack of ward social spaces; little personalisation of single rooms or bed bays; and under-use of gardens.

Each project was developed by a small local multidisciplinary team including carers with input from local colleagues working in health and safety and control of infection. Common to all schemes, particularly in ward areas, has been the need to de-clutter to improve sight lines; improvements to lighting and flooring; the introduction of intuitive wayfinding cues together with improved signage; and the creation of social spaces. Natural light has been maximised and many ward schemes have installed LED lighting, including dynamic lighting systems, which can be adjusted throughout the day depending on care needs. Wood-effect vinyl flooring has proved popular and has made ward areas look less clinical. Colour and contrast together with artworks have been used to differentiate bed bays which can look almost identical, and bed spaces have been signposted using images or memory boxes (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Signposting bed spaces. Large images of flowers assist patients to find their beds. © The King's Fund.

Wherever possible the redesigns have sought to bring a sense of familiarity to the hospital environment, for example making sure chairs in social spaces are grouped in small clusters, as people would experience at home, creating domestic-scale dining areas, and using traditional and recognisable sanitary ware in bathrooms and toilets. Large nurses’ stations have been replaced with smaller welcoming reception desks, and nurses and clinical colleagues are now working from specially designed areas or touch-down stations in bed bays rather than from a central area. This has made the staff more visible, with a consequent reduction in the use of call bells. Creating resting points along ward corridors and small communal spaces have improved socialisation. Increased access to outside spaces has improved patients’ orientation and general well-being. Wards that have provided snack trolleys, reintroduced dining areas or provided coloured crockery are reporting improvements in patient nutrition and socialisation and less food wastage.

Evaluation and outcomes

Many of the environmental changes appear to have occurred as a consequence of the training that teams received before they started planning their projects. For example changes in staff attitudes such as investing in table cloths, laying tables, and purchasing coloured crockery, as well as increases in activities for patients such as the provision of newspapers or implementation of therapy hours, were reported; in the words of one team member, it is ‘not just about the colour of the paint’.

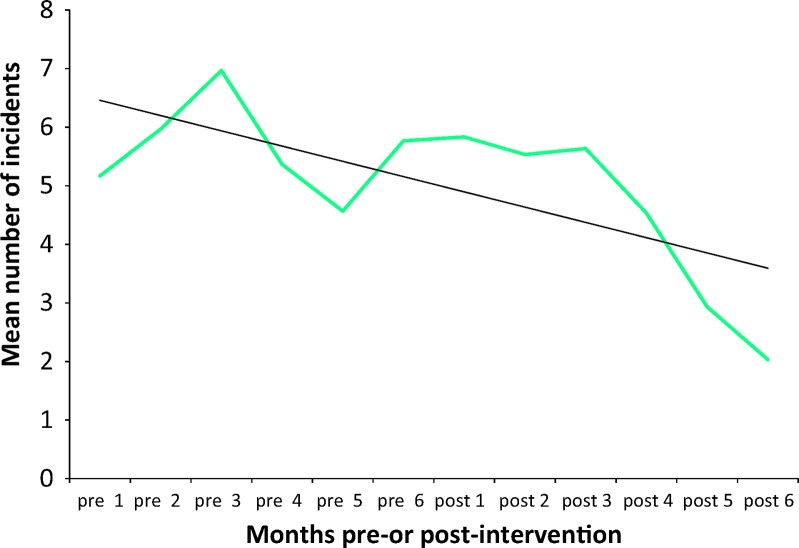

Each team undertook a local evaluation and ten projects were selected for specific evaluation support.10 Although only a small sample, they were chosen to maximise diversity of sites, settings and projects, but there was no attempt to match sites or control case mix. The only standard part of the intervention was the training programme provided by The King's Fund. Nevertheless, data from the local evaluations indicate that simple and inexpensive changes to the physical environment, such as changing the colour of the toilet doors and using matt flooring, appear to deliver positive outcomes in relation to the prescribing and administration of anti-psychotic medication, incidence of violence and aggression (Fig 2), falls, behaviour and use of space, and patient engagement in meaningful activity. Making spaces seem smaller and more familiar, and reducing the numbers of decisions that have to be made by patients in finding their way to places such as the toilet, the dining room or their own bed space, seems to significantly reduce agitation. Staff metrics also improved with reductions in sickness and absence rates and better recruitment and retention. Estates colleagues report that incorporating these design principles has cost no more than similar-sized schemes, provided better value for money and improved sustainability.

Fig 2.

Mean numbers of incidents of violence and aggression pre- and post-introduction of dementia-friendly environmental changes. Data taken from 10 sites participating in the King's Fund Enhancing the Healing Environment programme.

One of the more surprising findings of the programme was that even among dementia specialists there was a significant knowledge gap about the critical role that relatively straightforward and inexpensive improvements to the built environment can play in improving care and supporting the well-being of people with dementia. In addition, although significant numbers of people with dementia are to be found in most services, not all people working in or volunteering in hospitals have been able to access general training in dementia.

As a result of The King's Fund's programme, the secretary of state for health announced a £50 million capital fund for dementia-friendly improvements to health and social care organisations in England,11 and a report on the outcomes of the scheme is expected later this year.

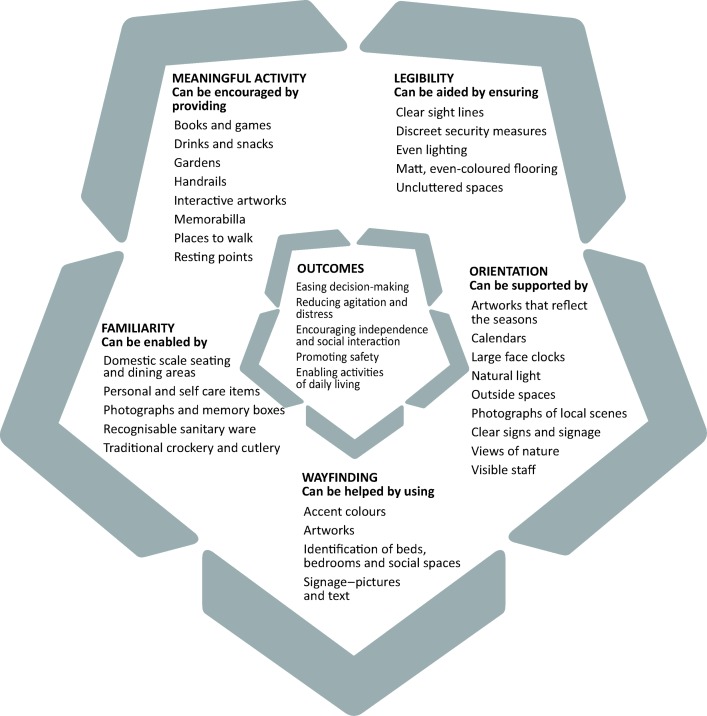

Design principles

As part of the programme, The King's Fund developed a set of overarching design principles which bring together best practice in creating more supportive care environments for people with cognitive problems and dementia (Fig 3). The principles draw on the learning from the EHE programme, a comprehensive review of the literature and the findings of the programme evaluation.

Fig 3.

Overarching design principles for dementia-friendly design. Reproduced with -permission from the King's Fund.

These principles, presented as a design wheel, describe supportive design for people with dementia. They have been designed to help prompt clinical and estates staff in discussion with patients and their carers to review all aspects of the environment before drawing up plans for any new build or refurbishment. The wheel has five sections grouped round the key desired outcomes for people with dementia: easing decision making; reducing agitation and distress; encouraging independence and social interaction; promoting safety; and enabling activities of daily living.

Dementia-friendly environmental assessment tools

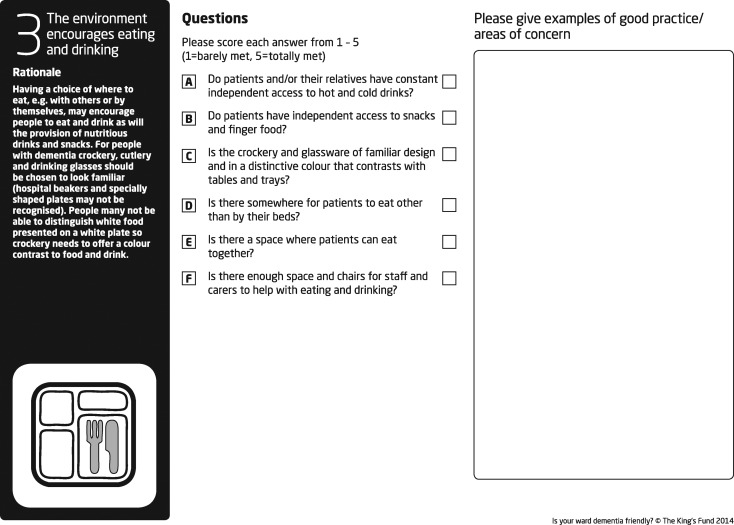

As an outcome from the programme, staff and carers were instrumental in the development of an environmental assessment tool Is your ward dementia friendly? Informed by research evidence and best practice and designed for use by carers together with staff to assess the ward environment the tool, was designed to be practical and easy to use.

The tool focuses on those aspects of the physical environment known to impact on people with dementia. It assesses not only the physical environment (such as floor coverings and use of paint colours) but also the way that the environment encourages people to behave and interact. The tool is divided into seven criteria, according to which the environment should promote:

-

text 1

meaningful interaction between patients, their families and staff

-

text 2

well-being

-

text 3

eating and drinking

-

text 4

mobility

-

text 5

continence and personal hygiene

-

text 6

orientation

-

text 7

calm, safety and security.

During the development of the tool, extensive testing indicated that it provided a useful benchmark to measure progress, a valuable framework to inform action plans and a catalyst for prompting discussions about both care delivery and the physical environment.

The tool was launched in 2011 and revised in 2013 to include an evidence-based rationale for each criterion (see Fig 4 for an example) to help people understand why each set of questions is important to creating a more dementia-friendly environment.

Fig 4.

Criterion 3 from the King's Fund's environmental assessment tool Is your ward dementia -friendly? – ‘The environment encourages eating and drinking’. Reproduced with permission from the King's Fund.

At the request of users, further tools were developed for general hospital departments, including outpatient clinics, therapy areas, and care homes. The tools have informed the development of the current NHS England patient-led assessments of the care environment (PLACE), and their completion was required as part of the baseline data for applications to the Department of Health's dementia-friendly capital fund. The tools are available for free via the King's Fund's web site. By September 2014, over 5,500 copies had been downloaded and they are in wide use in hospitals, care homes and hospices across the UK well as in Australia, Scandinavia, Holland, Brazil, Canada and the USA.

The results of the most recent user survey have been encouraging, with responses received from the UK, Australia, Norway and Canada. The three most common reasons given for undertaking an assessment of the physical environment of care were to improve the care environment (64%), as part of a broader organisational change (40%), or to demonstrate the impact of changes being made to the environment (36%). The evidence-informed rationale for each of the sections was highly valued by respondents, with 99% saying they found it helpful and increased staff understanding of the needs of people with dementia as the following quotes illustrate:

Better understanding of why changes to the environment are so important for the care of these patients.

I liked the way that it was easily accessible and written in plain language so that all grades of staff could understand each point. I also liked the way the tool can be (and has been) used at relatives meetings to outline what we are planning.

In addition to using tools to assess the environment as part of an improvement project, they were reported to have been used in the education of student nurses and care home staff; as part of dementia champions training; and to inform standards required by local authorities for future extra care housing developments.

The most commonly cited change made as a result of using the tools was securing finance from the Board to make changes. Other examples given included: changing staff and carers’ attitudes; getting managers to support change; helping people realise what the needs are; convincing estates to make changes to signage, flooring and colour schemes as part of the rolling refurbishment programme; and improving dining areas and crockery.

Environmental assessment tools for health centres and GP premises and for extra care housing were launched in October 2014. Work is also currently being taken forward with the Alzheimer's Society to provide guidance for people in their own homes.

Good design for dementia is good design for all

Sceptics might assume that making general hospitals more dementia friendly must be an expensive, time-consuming activity and a luxury that the NHS cannot afford, particularly given the current financial constraints. However, providers of health care services will continue to need to maintain and improve the buildings in which they deliver care and the EHE experience has shown that doing this in a dementia-friendly way is no more costly.

The schemes have shown how relatively straightforward and inexpensive changes to the design and fabric of the hospital environment can have a considerable impact on the wellbeing of people with dementia. Appropriately designed environments also have the potential to reduce the incidence of agitation and challenging behaviour, promote independence, improve nutrition and hydration, increase engagement in meaningful activities, encourage greater carer involvement as well as improving staff morale, recruitment and retention, all of which contribute to a reduction in overall service costs.

The overarching design principles and environmental assessment tools developed by The King's Fund give hospitals the opportunity to review the dementia friendliness of their current environments and provide a platform for prioritising future refurbishments or new builds.

The scale of the challenge of caring for people with dementia in hospital is enormous. The EHE programme has demonstrated that it is possible to create a more supportive environment for people with dementia in hospital settings, and many of the principles can be applied to other care settings. The challenge is for clinical staff working in partnership with patients, managers and estates staff to develop hospital environments that meet the needs of all patients – because, if you get it right for people with dementia, you will get it right for everybody.

References

- 1.Royal College of Physicians Future hospital: caring for medical patients London: Royal College of Physicians, 2013Available online at www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/future-hospital-commission [Accessed 30 September 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeisel J, Silverstein N, Hyder J, et al. Environmental correlates to behavioral health outcomes in Alzheimer's special care units The Gerontologist 2003;43:697–711. 10.1093/geront/43.5.697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alzheimer's Society Counting the cost London: Alzheimer's Society, 2009Available online at www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?downloadID = 356 [Accessed 10 November 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health Living well with dementia: A national dementia strategy London: Department of Health, 2009Available online at www.gov.uk/government/publications/living-well-with-dementia-a-national-dementia-strategy [Accessed 10 November 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health Prime minister's challenge on dementia – delivering major improvements in dementia care and research by 2015 London: Department of Health, 2012Available online at www.gov.uk/government/publications/prime-ministers-challenge-on-dementia[Accessed 10 November 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health Using the Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) payment framework. Guidance on new national goals for 2012–13 London: Department of Health, 2012Available online at www.gov.uk/government/publications/using-the-commissioning-for-quality-and-innovation-cquin-payment-framework-guidance-on-new-national-goals-for-2012-13 [Accessed 10 November 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Royal College of Psychiatrists National audit of dementia care in general hospitals 2012-13. Second round audit report and update. London: RCPsych, 2013Available online at www.hqip.org.uk/assets/NCAPOP-Library/NCAPOP-2013-14/NAD-NATIONAL-REPORT-12-June-2013.pdf [Accessed 10 November 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Royal College of Nursing Commitment to the care of people with dementia in general hospitals. London: Royal College of Nursing, 2011Available online at www.rcn.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/480269/004235.pdf [Accessed 10 November 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dementia Action Alliance Call to action. www.dementiaaction.org.uk/ [Accessed 30 September 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waller S, Masterson A, Finn H.Improving the patient experience: developing supportive design for people with dementia: the King's Fund's Enhancing the Healing Environment Programme 2009–2012 London: The King's Fund, 2013Available online at www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/developing-supportive-design-people-dementia [Accessed 10 November 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health Expressions of interest for funding to improve care environments for people with dementia www.gov.uk/government/news/expressions-of-interest-for-funding-to-improve-care-environments-for-people-with-dementia [Accessed 30 September 2014]. [Google Scholar]