Abstract

BACKGROUND

Open abdomen (OA) has been generally accepted for its magnificent superiority and effectiveness in patients with severe trauma, severe intra-abdominal infection, and abdominal compartment syndrome. In the meantime, OA calls for a mass of nursing and the subsequent enteroatomospheric fistula (EAF), which is one of the most common complications of OA therapy, remains a thorny challenge.

CASE SUMMARY

Our team applied thermoplastic polyurethane as a befitting material for producing a 3D-printed “fistula stent” in the management of an EAF patient, who was initially admitted to local hospital because of abdominal pain and distension and diagnosed with bowel obstruction. After a series of operations and OA therapy, the patient developed an EAF.

CONCLUSION

Application of this novel “fistula stent” resulted in a drastic reduction in the amount of lost enteric effluent and greatly accelerated rehabilitation processes.

Keywords: 3D printing, Enteroatmospheric fistula, Open abdomen, Isolation technique, Case report

Core tip: Few methods can be utilized to control enteroatomospheric fistulas (EAFs) which are unlikely to achieve spontaneous closure. The 3D-printed “fistula stent” presented here can be implanted to close EAF in the early stage of open abdomen. We think that this report could start the train of thought for plugging EAF to reduce the lost enteric effluent as well as avoid water electrolyte imbalance, corrosion on the wound surface, and intra-abdominal infection.

INTRODUCTION

The open abdomen (OA) therapy has been commonly recognized as a crucial treatment in settling severe trauma, severe intra-abdominal infection (sIAI) and abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS). The World Society of ACS has formulated a classification for OA in which frozen OA with fistula is classified as grade 4 (Table 1)[1]. Meanwhile, fistula, which is one of the most common complications of OA, remains a nightmare for all surgeons and intensive care unit doctors, and urgently needs to be solved[2].

Table 1.

Open abdomen classification from the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

| OA classification from the WSACS | |

| Grade 1A | Clean without fixation |

| Grade 1B | Contaminated without fixation |

| Grade 1C | Enteric leak without fixation |

| Grade 2A | Clean with developing fixation |

| Grade 2B | Contaminated with developing fixation |

| Grade 2C | Enteric leak with developing fixation |

| Grade 3A | Clean with frozen abdomen |

| Grade 3B | Contaminated with frozen abdomen |

| Grade 4 | Formed EAF with frozen abdomen |

OA: Open abdomen; WSACS: World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome; EAF: Enteroatmospheric fistula.

Enteroatmospheric fistula (EAF) is a type of fistula different from enterocutaneous fistula (ECF). The occurrence rate of EAFs is reported to be 25% in patients receiving OA with an associated mortality rate of 42%[3]. Various reasons result in these openings between the atmosphere and the lumen within the gastrointestinal tract. Unlike ECF, EAF has neither connective fistulous tract or overlying soft tissue such as the skin, subcutaneous tissue, omentum majus and other gastrointestinal tract which leads to high flow of enteric fistula effluent and makes it unlikely to reach spontaneous closure. In addition to fluid and electrolyte imbalance, acid-base imbalance and gastrointestinal dysfunction, enteric fistula effluent from EAF can cause more disastrous effects[4]: enteric fistula effluent contaminates the exposed wound and exacerbates the infection condition which can lead to sepsis in severe cases. Besides, high and continuous output of digestive juices raises the difficulty in fistula closure, prolongs the length of hospital stay along with medical expense[3], and increases mortality tremendously.

To date, multiple techniques have been come up with to solve EAF such as silicone fistula plug[5], collapsible EAF isolation device[6], polyethylene glycol tube[7], and covered self-expending metal stent[8]. However, these techniques can only be used after the formation of frozen abdomen or the adhesion between the bowel and the abdominal wall. On the other hand, they can hardly reach accurate match with the trend of bowel or the shape of the orifice of the fistulous tract. Furthermore, after the labiate fistula is formed, the outcomes usually get worse[9]. In order to carry out enteral nutrition (EN) as early as possible and shorten the waiting time before definitive gastrointestinal reconstruction, our team applied a 3D-printed “fistula stent”, which is a combination of 3D printing with traditional isolation technique, to control enteric fistula effluent at the early stage of OA.

CASE PRESENTATION

Patient information

A 33-year-old male patient complaining of abdominal pain and distension was initially diagnosed as bowel obstruction and went through enterolysis and omentum majus biopsy (Table 2). Several days after the first surgery, the patient appeared a relapse of abdominal pain and received exploratory laparotomy and bypass operation. Then, the patient’s physical condition turned to go downhill with intermittent fever and cachexia. Afterwards, the patient was referred to our clinic with sIAI, hypoalbuminemia, hydrothorax, poor incisions healing, and suspected fistula with intestinal juice flowing from the incision.

Table 2.

Patient’s previous surgeries

| Timing | Diagnosis | Surgeries |

| Initial | Bowel obstruction | Enterolysis and omentum majus biopsy |

| 4 wk later | Abdominal pain | Exploratory laparotomy and bypass operation for bowel obstruction |

| 7 wk later | Hydrothorax | Bilateral thoracentesis |

| 2 mo later | Fistula and sIAI | OA |

OA: Open abdomen; sIAI: Severe intra-abdominal infection.

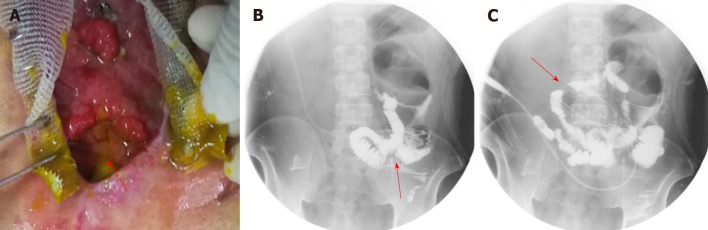

After the patient was admitted to our hospital, he presented with intermittent high fever (39 °C) and cachexia. Anti-infection therapy, acid suppression therapy, digestive juices secretion suppression therapy, total parenteral nutrition (PN), and double-pipe drainage were utilized to maintain the patient’s homeostasis. To relieve the symptoms, we decided to carry out OA to locate the source of enteric fistula effluent and control the IAI. During the procedure of exploration, the fistula was found situated at the place where the side-to-side anastomosis was carried out during the bypass operation (Figure 1A). The volume of enteric fistula effluent reached a peak of approximately 2500 mL/d, corroding surrounding tissue and incision continuously, thus making the orifice of the fistulous tract and incision unlikely to heal spontaneously. Afterwards, high-resolution computed tomography and contrast-mediated fistula angiography confirmed the existence of the EAF (Figure 1B), the area of which reached 8.5 cm2, thus making most other isolation techniques inapplicable and invalid[9].

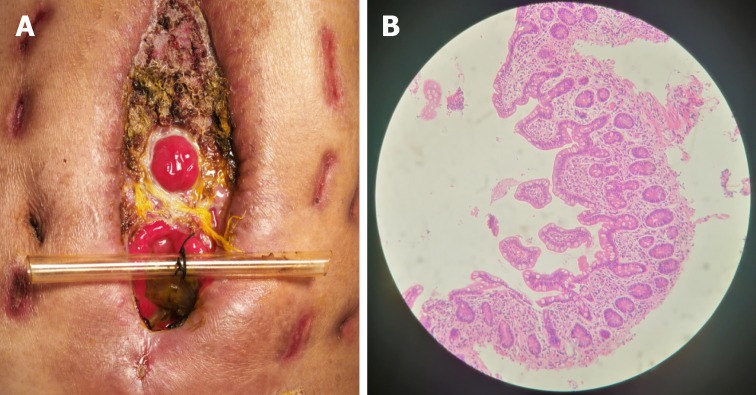

Figure 1.

Clinical picture and imaging materials of the patient. A: The enteroatmospheric fistula (EAF) happened at side-to-side anastomosis was exposed and visible after open abdomen (red arrow); B: Contrast-mediated fistula angiography through the orifice of the fistulous tract (red arrow); C: The location of initial obstruction was shown (red arrow).

Interventions

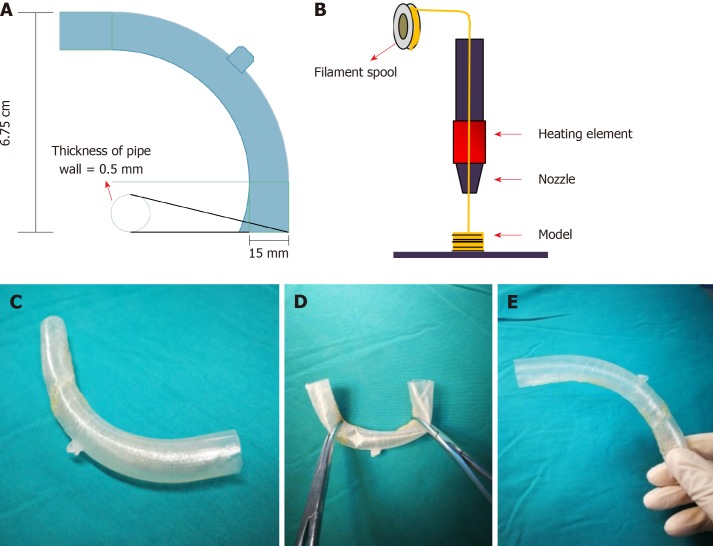

With the intention of blocking the enteric effluent to improve fistula healing, restoring EN, and carrying out definitive surgeries earlier, we attempted to implant a “fistula stent” to plug the EAF. After investigating the anatomy of EAF from fistulography and measuring the actual inner diameter and tortuosity of the bowel with fingers, we utilized Solidwork software to build the model of a hollow and curving pipe stent with a small protuberance and integrated wall. The following data were collected: inner diameter of 14 mm, thickness of pipe wall of 0.5 mm, length of 14 cm, and bend pipe instead of combined two straight ones. The whole model was saved in Standard Template Library (STL) form to be recognized by 3D printer (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Manufacturing process of the “fistula stent”. A: The blueprint of “fistula stent” was built with Solidwork software and saved in Standard Template Library (STL) form; B: Fused Deposition Modeling is a process where thermoplastic filaments are driven with a motorized heated nozzle; C: Build model of a hollow and curving pipe stent with a small protuberance and integrated wall; D: Flexibility of the “fistula stent”; E: Shape memory of the “fistula stent” after application of an external force.

Thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) is a synthetic and biocompatible material with strong tenacity and good flexibility, which has been applied widely in medical devices such as catheter and vascular graft. Our team has been investigating the properties and biocompatibility of TPU for years and the safety of TPU-made stent is assured[10]. We collaborated with Nanjing Normal University and utilized Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM), which is one of the most classic and mature techniques of 3D printing, to build the “fistula stent” from STL file (Figure 2B).

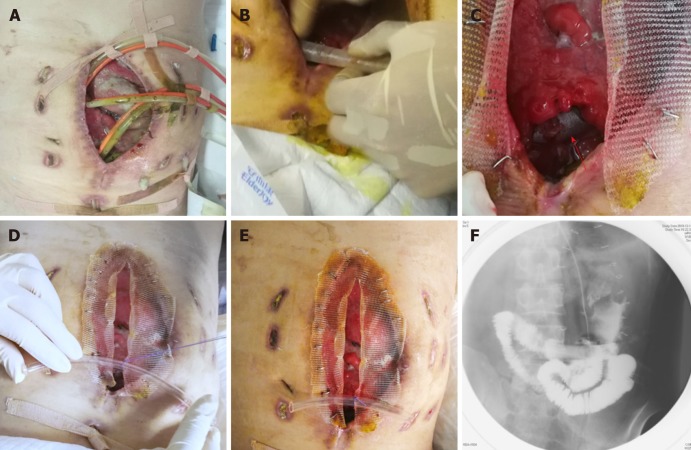

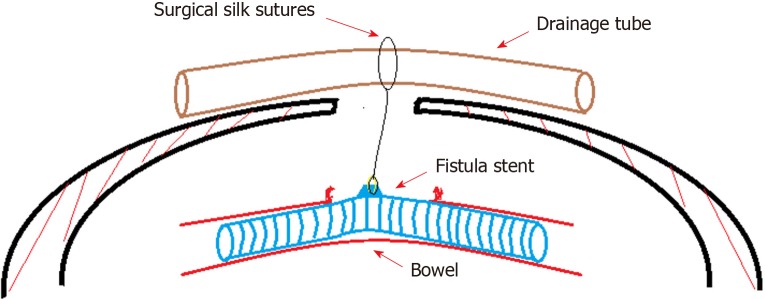

Nine days after carrying out OA, the stent was implanted into the bowel through the orifice of the fistulous tract and proved to suit the trend of bowel ideally (Figure 3A-E). No obstruction was observed around the orifice of the fistulous tract. Then, contrast-mediated fistula angiography was conducted to verify the effectiveness of the stent with the contrast agent flowing past the stent without obstruction (Figure 3F). The protuberance was fixed with threads to avoid displacement due to peristalsis or postural changes (Figure 4). After the implantation, there was an obvious decrease in the amount of enteric fistula effluent and increase in stool frequency and capacity. Four days after implantation, we restored the patient’s EN by nasal feeding, which was started from 500 mL and increased to 1500 mL during the following 3 d. No abnormal or subjective discomfort was observed during the whole process.

Figure 3.

Process of the implantation and fixation of the “fistula stent”. A: Four double pipes were used to drainage enteric fistula effluent before implantation ; B: The process of implantation; C: After the implantation the stent can still be seen (red arrow); D: The process of fixation by suturing the small protuberance with a latex tube overhanging the abdominal wall; E: After the accomplishment of implantation, only one double pipe was needed for drainage; F: Contrast-mediated fistula angiography was conducted to verify the effectiveness of the stent and the contrast agent flowed past the stent without obstruction.

Figure 4.

Concept graph of how is the “fistula stent” fixed in the bowel. The protuberance is connected with a latex drainage tube hanging over the abdominal wall in order to prevent the sliding due to peristalsis.

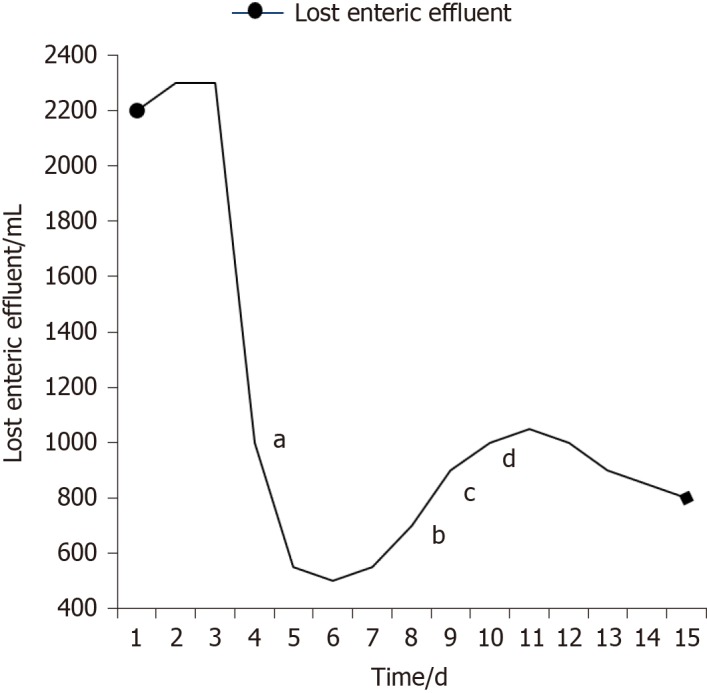

Several indexes of the patient were recorded in which we regarded the amount of lost enteric effluent (Vloss) as the most significant one. In the duration of therapy, Vloss was equal to the amount of drainage fluid from the fistula orifice minus the amount of fistula irrigation fluid. EAF in this patient belonged to high flow fistula (> 500 mL/d) because the scope of the orifice of the fistulous tract occupied nearly half of the intestinal wall (Figure 5A). Though it was still higher than 400 mL/d, leakage of enteric effluent was notably reduced after the implantation. With the increase in the amount of EN per day from 500 mL to 1500 mL, Vloss floated upwards within a short time and gradually turn to decrease by degrees.

Figure 5.

Recorded amount of lost enteric effluent. aThe day of implantation; bStarting enteral nutrition (EN) of 500 mL; cEN of 1000 mL; dEN of 1500 mL.

Outcomes

Seven days after implantation, no sign of pyrexia or obvious infection existed and the general condition of the patient was improved with frozen abdomen formed steadily and drainage unobstructed. Considering the good physical condition of the patient and the blocked EAF, skin grafting on the abdominal wall was conducted successfully. Timely blocking of EAF laid the foundation of the skin graft healing. Ten days after skin grafting, the abdomen had granulated around the EAF and the orifice of the fistulous tract had also decreased to a very small size (Figure 6). During the follow-up, we observed that the orifice of the fistulous tract was enlarged due to the change in abdominal incision and body position, so we used butterfly-shaped adhesive to strain the bilateral abdominal walls to control the Vloss further. The patient is receiving EN in good condition and waiting for definitive intestinal anastomosis and abdominal closure, in which the “fistula stent” will be drawn from the orifice of the fistulous tract.

Figure 6.

Follow-up after the implantation. A: After skin grafting, the abdomen had granulated around the enteroatmospheric fistula (EAF) and the orifice of the fistulous tract had also decreased to a very small size; B: Atrophic intestinal mucosa in the distal end of the EAF before restoring enteral nutrition.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

EAF, sIAI, and hypoalbuminemia.

TREATMENT

Fistula stent; anti-infection therapy; total PN and double-pipe drainage.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient has passed the crisis and received skin grafting. The patient is receiving EN in good condition and waiting for definitive intestinal anastomosis and abdominal closure.

DISCUSSION

What we introduce in this case report is a hollow and curving pipe stent with integrated wall, which is a combination of isolation technique with 3D printing[11], and can be applied to plug EAF at the very early stage of OA. Unlike silicone fistula plug reported by Ozer et al[5] or PEG tube reported by Miranda et al[7], 3D-printed “fistula stent” can be used to block EAF as soon as the EAF is discovered or formed. In other words, successfully plugging EAF from inside can transform some grade 4 OA to grade 1C or 2C in a sense, rather than simply blocking fistulous tract or ECF after the formation of frozen abdomen or skin grafting. We think that our report could start the train of thought for plugging EAF at the early stage to reduce the amount of lost enteric effluent as well as avoid water electrolyte imbalance, corrosion on wound surface, and IAI. Furthermore, “fistula stent” functions as a temporary tract to restore EN and improve bowel function, which can accelerate the process of rehabilitation. In addition, a stent which can block nearly all the orifice of the fistulous tract saves a lot of work of drainage and succus entericus reinfusion.

We regard our 3D-printed “fistula stent” as a strong and ideal supplement to negative pressure wound therapy, total PN, and somatostatin therapy, which are the key techniques to close an EAF[12]. And it has the potential to be combined with advanced technique of bio-printed 3D human intestinal tissues[13]. However, several deficiencies exist with FDM based 3D-printed “fistula stent”. When adhesion between the bowel and the abdominal wall or the frozen abdomen formed, the size and shape of the orifice of the fistulous tract may change, thus causing the stent unfit with the bowel tract. On the other hand, the “fistula stent” has the risk of enlarging the EAF size, reducing the rate of spontaneous closure. Further, the sample size is still very limited and more well-designed trials are required to verify the effectiveness of 3D-printed plugs.

CONCLUSION

EAFs in OA patients continue to be a challenge. Our 3D-printed “fistula stent” is presented to offer an effective and applicable method to block EAF at the early stage to simplify the management of OA with EAF, thus providing conditions for definitive surgeries.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Conflict-of-interest statement: We declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: February 18, 2019

First decision: February 26, 2019

Article in press: March 16, 2019

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the guidelines of the CARE Checklist (2016) have been adopted.

P-Reviewer: Gupta R, Lara FJ, Misiakos EP, Okumura K, Skierucha M S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Song H

Contributor Information

Zi-Yan Xu, Research Institute of General Surgery, Jinling Hospital, Nanjing 210002, Jiangsu Province, China; School of Medicine, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210008, Jiangsu Province, China.

Hua-Jian Ren, Research Institute of General Surgery, Jinling Hospital, Nanjing 210002, Jiangsu Province, China.

Jin-Jian Huang, Research Institute of General Surgery, Jinling Hospital, Nanjing 210002, Jiangsu Province, China.

Zong-An Li, NARI School of Electrical and Automation Engineering, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing 210042, Jiangsu Province, China.

Jian-An Ren, Research Institute of General Surgery, Jinling Hospital, Nanjing 210002, Jiangsu Province, China. jiananr@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Kirkpatrick AW, Roberts DJ, De Waele J, Jaeschke R, Malbrain ML, De Keulenaer B, Duchesne J, Bjorck M, Leppaniemi A, Ejike JC, Sugrue M, Cheatham M, Ivatury R, Ball CG, Reintam Blaser A, Regli A, Balogh ZJ, D'Amours S, Debergh D, Kaplan M, Kimball E, Olvera C Pediatric Guidelines Sub-Committee for the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Intra-abdominal hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome: Updated consensus definitions and clinical practice guidelines from the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1190–1206. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-2906-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schecter WP, Hirshberg A, Chang DS, Harris HW, Napolitano LM, Wexner SD, Dudrick SJ. Enteric fistulas: Principles of management. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boele van Hensbroek P, Wind J, Dijkgraaf MG, Busch OR, Goslings JC. Temporary closure of the open abdomen: A systematic review on delayed primary fascial closure in patients with an open abdomen. World J Surg. 2009;33:199–207. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9867-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cristaudo AT, Jennings SB, Hitos K, Gunnarsson R, DeCosta A. Treatments and other prognostic factors in the management of the open abdomen: A systematic review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82:407–418. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozer MT, Sinan H, Zeybek N, Peker Y. A simple novel technique for enteroatmospheric fistulae: Silicone fistula plug. Int Wound J. 2014;11 Suppl 1:22–24. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heineman JT, Garcia LJ, Obst MA, Chong HS, Langin JG, Humpal R, Pezzella PA, Dries DJ. Collapsible Enteroatmospheric Fistula Isolation Device: A Novel, Simple Solution to a Complex Problem. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:e7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miranda LE, Miranda AC. Enteroatmospheric fistula management by endoscopic gastrostomy PEG tube. Int Wound J. 2017;14:915–917. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rebibo L, Wacrenier A, Thiebault H, Delcenserie R, Regimbeau JM. Combined endoscopic and surgical covered stent placement: A new tailored treatment for enteroatmospheric fistula in patients with terminal ileostomy. Endoscopy. 2017;49:E35–E36. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-121489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blair SG, Fayard NJ, Ahmed N, Rogers EA, Simmons JD. Early use of split-thickness skin graft allows separation of the wound into different compartments facilitating the collection of enteroatmospheric fistulae output. Am Surg. 2015;81:E96–E98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang JJ, Ren JA, Wang GF, Li ZA, Wu XW, Ren HJ, Liu S. 3D-printed "fistula stent" designed for management of enterocutaneous fistula: An advanced strategy. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:7489–7494. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i41.7489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang J, Li Z, Hu Q, Chen G, Ren Y, Wu X, Ren J. Bioinspired Anti-digestive Hydrogels Selected by a Simulated Gut Microfluidic Chip for Closing Gastrointestinal Fistula. iScience. 2018;8:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2018.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terzi C, Egeli T, Canda AE, Arslan NC. Management of enteroatmospheric fistulae. Int Wound J. 2014;11 Suppl 1:17–21. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madden LR, Nguyen TV, Garcia-Mojica S, Shah V, Le AV, Peier A, Visconti R, Parker EM, Presnell SC, Nguyen DG, Retting KN. Bioprinted 3D Primary Human Intestinal Tissues Model Aspects of Native Physiology and ADME/Tox Functions. iScience. 2018;2:156–167. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2018.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]