Abstract

Disenrollment rates are one way that policy makers assess the performance of Medicare Advantage (MA) health plans. We use 3 years of data published by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to examine the characteristics of MA contracts with high disenrollment rates from 2015 to 2017 and the relationship between disenrollment rates in MA contracts and 6 patient experiences of care performance measures. We find that MA contracts with high disenrollment rates were significantly more likely to be for-profit, small, and enroll a greater proportion of low-income and disabled individuals. After adjusting for plan characteristics, contracts with the highest levels of disenrollment were statistically significantly more likely to perform poorly on all 6 patient experience measures. CMS should consider additional oversight of MA contracts with high levels of disenrollment and consider publishing disenrollment rates at the plan level instead of at the contract level.

Keywords: Medicare Advantage, patient-reported outcomes, quality of care, Medicare, disenrollment

What do we already know about this topic?

Medicare Advantage (MA) beneficiaries who are in poorer health and have higher health care spending are more likely to disenroll from their MA plan than their counterparts.

How does your research contribute to the field?

We explore the characteristics of MA contracts with high disenrollment rates from 2015 through 2017 and assess whether there is an association between high disenrollment rates and patient-reported experiences with care.

What are your research’s implications toward theory, practice, or policy?

Our findings suggest that individuals enrolled in contracts with high levels of disenrollment are more likely to report poor member experiences than individuals enrolled in contracts with lower levels of disenrollment. Policy makers should consider additional oversight of MA contracts with high levels of disenrollment.

Background

Since 2004, the number of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage (MA) program tripled from 5.3 million to 19.0 million.1 In 2017, one-third of people in Medicare were enrolled in MA.1 Each year during the open enrollment period, MA enrollees have the option to switch to traditional Medicare, switch to another MA plan, or continue with their current MA plan. On average, 9% of enrollees choose to voluntarily leave their MA plan every year.2 The relatively stable annual voluntary disenrollment rates, however, mask the wide range of disenrollment rates between MA contracts.2-4

High disenrollment rates are considered an undesirable outcome for patients and plans. From the patient perspective, it may be indicative of inadequate care during the plan year. Switching plans or transitioning to traditional Medicare may also result in changes in one’s care team affecting continuity of care, which may be particularly important to high-need patient populations such as those with multiple chronic conditions.5 From the plan perspective, high disenrollment rates reduce the incentive to invest in primary or secondary prevention, such as vaccinations or disease management. These programs may result in less costly care in later years, but these cost savings may not accrue to the plan if the individual changes plans.

Recent studies have largely focused on identifying the patient characteristics associated with disenrollment from MA. Beneficiaries who are in poorer health and have higher health care spending are more likely to leave their MA plan than their counterparts.6-8 Other research has found that disenrollment rates can reflect issues in access to care and cost.2,3,9 A recent US Government Accountability Office (GAO) study of 126 MA contracts with high disenrollment rates found that sicker individuals were more likely to leave their MA health plan than healthy individuals in 35 contracts.3 Early studies of the predecessor to the MA program, the Medicare Managed Care program, found patient experiences and contract characteristics were correlated with disenrollment. A study by Lied and colleagues using Medicare Managed Care program data from 1998 found that patient experiences were associated with higher disenrollment rates.10 Another study from 1989 found disenrollment rates to be largely explained by individuals misunderstanding the program rules.11 A more recent study using data from 1998 and 2000 found that the inclusion of prescription drug benefit was associated with lower disenrollment rates.9 Given the maturation of the MA program and its growing popularity, it is important to revisit what types of MA contracts have high disenrollment rates and what the relationship between disenrollment rate and quality of care is.

The objective of this study was to examine the characteristics of MA contracts with high disenrollment rates and to assess whether there is an association between high disenrollment rates and patient-reported experiences with care in MA. We focused on patient-reported experiences with the health plan because these measures are likely to be more salient to the patient than other clinical and administrative quality-of-care measures and can provide key insights on the patients’ experience of care.

Methods

In this retrospective, pooled cross-sectional study of MA star ratings, we assessed the plan performance of MA contracts offering coverage from 2015 to 2017 and used logistic regression analysis to evaluate the relationship between level of disenrollment and the patient experiences of care. Specifically, we focused on patient-reported experiences of care (Domain 3—Member Experiences with Health Plan) collected from MA contracts from 2015 to 2017 for the 5-star rating and published in 2017-2019.

Since 2008, the Medicare program has publicly reported performance measures in the MA program, and since 2012 Medicare has used these performance measures in its pay-for-performance program.12 Given that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) reports performance at the MA contract level, our study examined MA at the contract level rather than at the plan level. MA contracts are defined during the bidding process and can consist of one or more plans managed by the same organization.

Data Sources and Study Sample

We combined publicly available contract and enrollment data on MA plans offering coverage from 2015 to 2017. Specifically, we combined publicly available data files from the CMS website that included star rating, plan directory, and enrollment files using the contract identifier. These data included information on MA contract characteristics, performance, and disenrollment rates. There were a total of 1898 MA contracts in the star ratings data sets. We excluded contracts that offered private fee-for-service plans, 1876 cost contract plans, contracts with less than 11 members enrolled, and contracts with a missing Categorical Adjustment Index and did not offer Part D. Finally, we excluded contracts due to missing disenrollment information for a final sample size of 1045.

Disenrollment Rates

We defined disenrollment rates using the performance measure “Members Choosing to Leave the Plan” which is calculated using the Medicare Beneficiary Database Suite of Systems from January 1 to December 31 for each calendar year. Involuntary disenrollment such as those due to members moving out of their plan’s service area and plan terminations are excluded. To facilitate comparisons, we classified contract disenrollment rates by tertile rather than as a continuous variable. Contracts in the highest tertile had disenrollment rates greater than 12% and contracts in the lowest tertile had disenrollment rates less than 7%.

To better understand the reasons driving disenrollment, we also examined the measures collected by the Disenrollment Reasons Survey from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2017. These include 5 publicly reported composite measures, where a lower score indicates better care: Problems Getting Needed Care, Coverage, and Cost Information; Problems with Coverage of Doctors and Hospitals; Financial Reasons for Disenrollment; Problems with Prescription Drug Benefits and Coverage; and Problems Getting Information about Prescription Drugs.

Contract Performance

The 5-star rating includes 5 Part C domains: staying healthy, managing chronic (long-term) conditions, member experiences with health plan, member complaints and changes in the health plan’s performance, and health plan customer service. We examined 6 measures from Domain 3: Member Experiences with Health Plan. The measures were as follows: Getting Needed Care, Getting Appointments and Care Quickly, Customer Service, Rating of Health Care Quality, Rating of Health Care Plan, and Care Coordination. These measures are case-mix adjusted composite measures on a scale of 0 to 100, where a higher score is better. These quality measures are collected by the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) survey. We created binary indicators for each of the measures and defined poor quality as the lowest quartile of performance based on each measure’s distribution.

Contract Characteristics

Contract characteristics include plan type, tax status, contract enrollment, years from contract date, inclusion of a Special Needs Plan (SNP), and Categorical Adjustment Index level. The plan types included health maintenance organization (HMO), HMO with a point of service, and local and regional preferred provider organization (PPO) plans. The tax status was for-profit or not-for-profit. Enrollment and years in the program were treated as categorical variables. We used the Categorical Adjustment Index, which was created by CMS to differentiate MA contracts by the level of low-income or Medicaid and disabled enrollees, to account for differences in the risk of social risk factors.13 The Categorical Adjustment Index is used to adjust star rating. We grouped the Categorical Adjustment Index final adjustment categories into 2 groups: low (2015: A, B, C, D, E; 2016 & 2017: A, B; lower proportions of low-income and disabled individuals) and high (2015: F, G, H, I, J, K, L; 2016: C, D, E, F, G; 2017: C, D, E, F; higher proportions of low-income and disabled individuals).

Data Analysis

We first examined MA contract characteristics, performance, and reason for disenrollment by level of contract disenrollment using descriptive statistics, and we report the differences in disenrollment rates using linear regression.

We used multivariate logistic regression analysis to estimate the odds of poor patient experiences of care by level of disenrollment (low [reference], medium, and high), controlling for plan characteristics (HMO vs PPO, for-profit vs not-for-profit, low vs high Categorical Adjustment Index level, enrollment, years in MA, and inclusion of an SNP in the contract). Because individual performance measures are included in the Overall Star Rating, we did not include the Overall Star Rating in these models to avoid introducing multicollinearity. Contracts that include an SNP can be expected to draw more complex patients, and so as a sensitivity test, we examine the relationship between level of disenrollment and patient experiences of care stratified by SNP status.

P values less than .05 were considered to be statistically significant in all analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.4.2.

Study Findings

The sample included 1045 MA HMO and PPO contracts offering prescription drug coverage in 2015 through 2017. These contracts enrolled a total of 13 536 676 individuals in 2015, 14 414 744 in 2016, and 16 033 593 in 2017, accounting for more than 80% of the total MA beneficiaries in each year.

Table 1 presents the sample characteristics by level of disenrollment (mean disenrollment rates by contract characteristics are presented in Supplemental Appendix Table 1). Of the 1045 MA contracts, 350 (33.5%) contracts had a low disenrollment rate (<7.0% disenrollment), 347 (33.1%) contracts had a medium disenrollment rate (7.0%-12.0% disenrollment), and 348 (33.3%) contracts had a high disenrollment rate (>12.0% disenrollment). Contracts with high disenrollment rates were significantly more likely to also have a high Categorical Adjustment Index, indicating larger proportion of low-income or disabled enrollees. Contracts with high disenrollment rates were also more likely to be for-profit and have fewer than 5000 enrollees.

Table 1.

Medicare Advantage Contract Characteristics by Overall Level of Disenrollment Rate, 2015-2017.

| Overall | Level of disenrollment |

P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Middle | High | |||

| N | 1045 | 350 | 347 | 348 | |

| Star year | .190 | ||||

| 2015 | 354 (33.9) | 103 (29.4) | 121 (34.9) | 130 (37.4) | |

| 2016 | 350 (33.5) | 120 (34.3) | 114 (32.9) | 116 (33.3) | |

| 2017 | 341 (32.6) | 127 (36.3) | 112 (32.3) | 102 (29.3) | |

| Overall Star Rating, % | <.001 | ||||

| 2-2.5 | 39 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.2) | 35 (10.1) | |

| 3-3.5 | 506 (48.4) | 94 (26.9) | 179 (51.6) | 233 (67.0) | |

| 4-5 | 491 (47.0) | 254 (72.6) | 162 (46.7) | 75 (21.6) | |

| Missing | 9 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) | 5 (1.4) | |

| Preferred provider organization, % | 237 (22.7) | 102 (29.1) | 84 (24.2) | 51 (14.7) | <.001 |

| Not-for-profit, % | 353 (33.8) | 185 (52.9) | 102 (29.4) | 66 (19.0) | <.001 |

| High Categorical Adjustment Index, % | 541 (51.8) | 106 (30.3) | 177 (51.0) | 258 (74.1) | <.001 |

| Years, % | <.001 | ||||

| <5 | 225 (21.5) | 31 (8.9) | 65 (18.7) | 129 (37.1) | |

| 5-9 | 242 (23.2) | 54 (15.4) | 90 (25.9) | 98 (28.2) | |

| 10-19 | 400 (38.3) | 171 (48.9) | 131 (37.8) | 98 (28.2) | |

| 20+ | 178 (17.0) | 94 (26.9) | 61 (17.6) | 23 (6.6) | |

| Enrollment, % | <.001 | ||||

| <5000 | 289 (27.7) | 73 (20.9) | 83 (23.9) | 133 (38.2) | |

| 5000-9999 | 167 (16.0) | 39 (11.1) | 62 (17.9) | 66 (19.0) | |

| 10 000-19 999 | 153 (14.6) | 63 (18.0) | 49 (14.1) | 41 (11.8) | |

| 20 000+ | 436 (41.7) | 175 (50.0) | 153 (44.1) | 108 (31.0) | |

Note. We used χ2 test with continuity correction to obtain the P values. N represents the number of contracts.

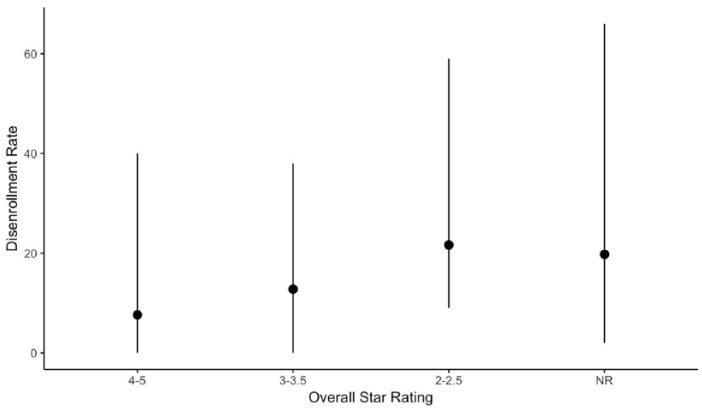

During the study period, disenrollment rates ranged from 0.0% to 66.0% with a median rate of 9.0% (interquartile range: 5.0%-15.0%). Among low disenrollment contracts, there were no contracts scoring less than 3 stars overall and over 70% scoring 4 or more stars. Among high disenrollment contracts, 10.1% had less than 3 stars and nearly one-quarter had 4 or more stars. Figure 1 shows that mean disenrollment rates declined with higher star ratings; however, the bars indicating the minimum and maximum values indicate substantial variation within each star rating level.

Figure 1.

Voluntary disenrollment rate mean and range by Overall Star Rating, 2015-2017.

Note. The error bars show the minimum and maximum values, and the point is the mean disenrollment rate. The Overall Star Rating category “NR” represents contracts classified by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services as not having enough data to rate performance.

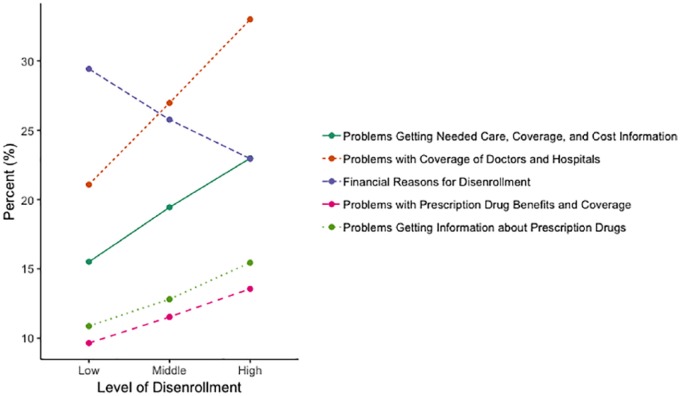

Figure 2 presents the average reported reasons for disenrollment by level of disenrollment. Among contracts with the lowest disenrollment rates, financial reasons was the most frequently selected reason at 29%, followed by problems with coverage (21%). Financial reasons include “monthly premium went up,” “prescription copayment went up,” “found a plan that costs less,” and “could no longer afford plan.” Among contracts with the highest disenrollment rates, the problems with coverage was the mostly frequently selected item at 33%, followed by financial reasons and problems getting needed care at 23%. In this sample, reported problems with prescription drug benefits were the least frequently selected reason for disenrollment.

Figure 2.

Average reported reason for disenrollment by level of disenrollment.

Table 2 presents adjusted coefficients from a linear regression model examining the association of contract characteristics and disenrollment. Controlling for other contract characteristics, we found significant differences by all contract characteristics except inclusion of an SNP. After adjustment, disenrollment rates were an average of 9.8 percentage points higher in MA contracts with 2.0 to 2.5 stars (P < .001) and 3.2 percentage points higher in MA contracts with 3.0 to 3.5 stars compared with MA contracts with 4.0 to 5.0 stars.

Table 2.

Adjusted Association Between Contract-Level Disenrollment Rates and Contract Characteristics, N = 1036.

| Beta (95% confidence interval) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Star rating | ||

| 4-5 Stars | Ref. | |

| 3-3.5 Stars | 3.20 (2.42 to 3.99) | <.001 |

| 2-2.5 Stars | 9.76 (7.75 to 11.76) | <.001 |

| Plan type | ||

| Health maintenance organization | Ref. | |

| Preferred provider organization | −1.86 (−2.84 to −0.88) | <.001 |

| Tax status | ||

| For-profit | Ref. | <.001 |

| Not-for-profit | −2.60 (−2.84 to −0.88) | |

| Categorical Adjustment Index | ||

| Low | Ref. | |

| High | 3.54 (2.57 to 4.51) | .021 |

| Enrollment | ||

| <5000 | Ref. | |

| 5000-9999 | −0.0 (−1.13 to 1.13) | .995 |

| 10 000-19 999 | −0.03 (−1.51 to 0.91) | .629 |

| 20 000+ | 1.15 (−0.11 to 2.20) | .031 |

| Years | ||

| <5 years | Ref. | |

| 5-9 years | −2.67 (−3.80 to −1.54) | <.001 |

| 10-19 years | −4.49 (−5.58 to −3.41) | <.001 |

| 20+ | −5.428 (−6.81 to −4.03) | <.001 |

| Special Needs Plan | ||

| No | Ref. | |

| Yes | −1.31 (−2.22 to −0.41) | .005 |

Note. SE = standard error.

In models examining the association of contract characteristics and reasons for disenrollment, we found different patterns (Supplemental Appendix Table 2). Contracts with a high Categorical Adjustment Index were more likely to report lower odds of members disenrolling for financial reasons relative to contacts with a low Categorical Adjustment Index. Contracts with more years of experience were associated with higher odds of members disenrolling for problems with coverage of doctors and hospitals. Similar trends occur for PPO vs HMO plans. However, contracts with 2.0 to 2.5 and 3.0 to 3.5 stars on the Overall Star Ratings are associated with higher scores for each of the disenrollment reasons compared with contracts with 4.0 to 5.0 stars.

The MA contracts with higher disenrollment rates were statistically significantly more likely to perform poorly on all 6 patient experience measures compared with contracts with the lowest disenrollment rates (Table 3). The odds of reporting poor patient experiences increased as level of disenrollment increased. The MA contracts with highest disenrollment rates were more likely to score the lowest quartile: Getting Needed Care (odds ratio [OR], 4.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.9-7.6), Getting Appointments and Care Quickly (OR, 6.7; 95% CI, 4.0-11.3), Customer Service (OR, 4.4; 95% CI, 2.9-6.7), Rating of Health Care Quality (OR, 7.2; 95% CI, 4.3-12.0), Rating of Health Plan (OR, 11.9; 95% CI, 7.3-19.5), and Care Coordination (OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.9-4.4).

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals of Patient Experience by Level of Disenrollment.

| Getting needed care | Getting appointments and care quickly | Customer service | Rating of health care quality | Rating of health care plan | Care coordination | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disenrollment (ref.: low) |

OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| Medium | 2.47** (1.58-3.8) | 3.31** (2.00-5.48) | 2.03** (1.35-3.06) | 3.48** (2.12-5.71) | 4.11** (2.55-6.64) | 1.54* (1.03-2.30) |

| High | 4.72** (2.94-7.58) | 6.70** (3.97-11.30) | 4.39** (2.87-6.72) | 7.19** (4.30-12.03) | 11.90** (7.25-19.54) | 2.86** (1.87-4.35) |

| N | 997 | 1022 | 982 | 994 | 1022 | 1006 |

Note. Logistic regression model accounted for plan type (HMO, PPO), tax status (for-profit, not-for-profit), Categorical Adjustment Index (high, low), contract enrollment, years from first contract date, and inclusion of a Special Needs Plan. N = the number of contracts; OR = odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; HMO = health maintenance organization; PPO = preferred provider organization.

p≤ .05. **p ≤ .001.

To test the robustness of our results, we also examined whether the relationship between disenrollment rates and patient experience varied by SNP status. These models yielded similar results to the main models. Models using the percentage of low-income subsidy recipients instead of Categorical Adjustment Index also returned similar results. We used the Categorical Adjustment Index in the main analysis due to a substantial amount of missing observations in the low-income subsidy variable.

Discussion

This study updates the literature on the relationship between patient experiences of care and disenrollment rates in MA. Consistent with previous studies, we found that contracts with high disenrollment rates were more likely to be for-profit, small plans, and more likely to care for low-income and/or disabled populations compared with contracts with low disenrollment rates.2,10 After adjusting for contract characteristics, we found that MA contracts with high disenrollment rates were more likely to receive low ratings on all 6 patient experience of care performance measures.

The 2 most frequently chosen reasons for voluntarily disenrolling were reported problems with coverage of doctors and hospitals and financial reasons. This is consistent with the GAO study where the top reasons for disenrollment among contracts with relatively high disenrollment in 2014 were preferred providers not in the network among contracts with health-biased disenrollment and problems with cost among contracts without health-biased disenrollment.3 We find that high disenrollment rates were negatively correlated with patient experience of care, and this relationship persists after adjusting for contract characteristics.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies examining health plans in the Medicare program. In a study of the Medicare Managed Care program in 1998, Lied and colleagues found that disenrollment rates were related to patient experiences of care—particularly patient-reported rating of their health care plan.10 Using data from 2015 at a time when MA contracts enroll a larger subset of the Medicare population, we continue to find that patient experiences are closely linked to disenrollment. Furthermore, a 2018 study by Li et al found that MA contracts with low star ratings had statistically significant higher disenrollment rates than plans with high star ratings among the end-stage renal population.8 In the broader MA population, we also find higher disenrollment rates in MA contracts with low star ratings.

Our finding that contracts with high disenrollment rates have poorer patient experiences of care than contracts with low disenrollment rates suggests that policy makers should consider increasing oversight over plans with high levels of disenrollment to ensure these contracts are providing members with access to providers, quality care, and good customer service. This is in agreement with GAO’s 2017 report recommendation that CMS review data on disenrollment by health status and the reasons for disenrollment to strengthen oversight of MA contracts.3 While our results cannot assess the direction of the relationship between patient experiences and disenrollment rates, health plans may want to consider focusing quality improvement efforts on patient experiences of care, as these measures are highly correlated with member decisions to disenroll. Furthermore, because financial reasons, which largely capture issues of affordability, was one of the most frequently selected reasons for leaving a plan, it may be important to revisit how changes to plan benefit designs affect disenrollment rates as well as consider whether issues of affordability may lead to health-biased disenrollment. However, to assess the impact of changes in plan benefit design, CMS would need to disaggregate disenrollment rates from the contract level to the plan level. Contracts often consist of more than one plan and sometimes plan service areas that are geographically dispersed.

Several limitations should be considered. First, this is a pooled cross-sectional analysis examining correlations, and as such, we cannot infer causality. Second, there are potentially unobserved differences among the MA contract populations that could have affected the findings. For example, we cannot observe county-level differences due to data limitations. We also cannot observe differences within contracts by plan. Third, we could not examine how changes in premiums or benefit design were associated with disenrollment rates because the data were reported at the contract level. A previous study found that MA enrollees who experienced an increase of $20 or more in premiums were more likely to switch plans.2 Fourth, our study is not generalizable to other types of health insurance.

High disenrollment rates are associated with poor performance on multiple patient experience measures tracked by Medicare. Contracts with high levels of disenrollment are more likely to score lower on patient experience measures, such as limited access to care and low ratings of health care and health plan, than contracts with low disenrollment rates. Policy makers should consider increasing oversight over contracts with high levels of disenrollment and consider publishing disenrollment rates at the plan level instead of at the contract level.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplemental_Material for What’s Driving High Disenrollment in Medicare Advantage? by Eva DuGoff and Sandra Chao in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr DuGoff reports speaking fees from ZimmerBiomet and consulting income from Optimal Solutions Group, LLC, Carmody Torrance Sandak & Hennessey LLP, and RAND Corporation, all unrelated to the topic of this paper.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr DuGoff reports receiving salary support from The Commonwealth Fund (Grant No. 20170785) and National Institute on Aging (R01AG050504, PI Shah). Ms Chao received salary support from The Commonwealth Fund (Grant No. 20170785) and Mathematica Policy Research.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD: Eva DuGoff  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6673-8428

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6673-8428

References

- 1. Medicare Advantage. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jacobson G, Neuman T, Damico A. Medicare Advantage Plan Switching: Exception or Norm? Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Government Accountability Office. Medicare Advantage: CMS Should Use Data on Disenrollment and Beneficiary Health Status to Strengthen Oversight. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Trends in Part C & D Star Rating Measure Cut Points. Baltimore, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, McKendry R. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ. 2003;327(7425):1219-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McWilliams JM, Hsu J, Newhouse JP. New risk-adjustment system was associated with reduced favorable selection in Medicare advantage. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(12):2630-2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rahman M, Keohane L, Trivedi AN, Mor V. High-cost patients had substantial rates of leaving Medicare advantage and joining traditional Medicare. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(10):1675-1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li Q, Trivedi AN, Galarraga O, Chernew ME, Weiner DE, Mor V. Medicare advantage ratings and voluntary disenrollment among patients with end-stage renal disease. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(1):70-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ng JH, Kasper JD, Forrest CB, Bierman AS. Predictors of voluntary disenrollment from Medicare managed care. Med Care. 2007;45(6):513-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lied TR, Sheingold SH, Landon BE, Shaul JA, Cleary PD. Beneficiary reported experience and voluntary disenrollment in Medicare managed care. Health Care Financ Rev. 2003;25(1):55-66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rossiter LF, Langwell K, Wan TT, Rivnyak M. Patient satisfaction among elderly enrollees and disenrollees in Medicare health maintenance organizations. JAMA. 1989;262(1):57-63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xu P, Burgess JF, Jr, Cabral H, Soria-Saucedo R, Kazis LE. Relationships between Medicare advantage contract characteristics and quality-of-care ratings: an observational analysis of Medicare advantage star ratings. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(5):353-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare 2017 Part C & D Star Rating Technical Notes. Baltimore, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Supplemental_Material for What’s Driving High Disenrollment in Medicare Advantage? by Eva DuGoff and Sandra Chao in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing