Abstract

Antagonists of the purinergic P2X3 receptors represent promising drugs for the treatment of inflammation and pain. The ATP derivative 2′,3′-O-(2,4,6-trinitrophenyl)-ATP (TNP-ATP) has been described as a potent competitive inhibitor of this receptor. In this work, the design and synthesis of novel TNP-ATP analogues bearing alkyl groups in the 2′,3′-position are reported. These compounds were biologically evaluated as P2X3 antagonists using the patch clamp recording technique on mouse trigeminal ganglionic sensory neurons. Some of the compounds showed nanomolar inhibitory potency for the P2X3 receptor. Further modification of these derivatives was made by substitution of the triphosphate chain with different acidic groups. All compounds were additionally tested at five human P2X receptor subtypes stably expressed in 1321N1 astrocytoma cells to evaluate their potency and P2X3 selectivity. Results confirmed the P2X3 antagonist potency for some derivatives.

Keywords: Purinergic receptors, P2X receptor antagonists, ATP derivatives, patch clamp assay, calcium influx assay

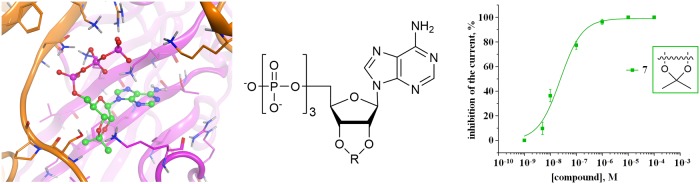

Purinergic P2X receptors (P2XRs) are ligand-gated ion channels, activated by the nucleotide adenosine-5′-triphosphate (ATP, I, Figure 1A) and permeable to Na+, K+, Ca2+, and small molecules.1,2 Seven human P2XR subunits (P2XR1–7) exist and assemble as homo- or heterotrimers. The interaction between the receptor and the agonist leads to a rearrangement of the protein, with the formation of a transmembrane pore and subsequent desensitization and inactivation of the receptor.3 P2XRs represent promising therapeutic targets for a number of diseases related to inflammation, pain, and cancer, including neurological and endocrinological diseases.1,3,4 P2X3R antagonists have potential as analgesics or anti-inflammatory agents since these receptors are expressed mainly in sensory ganglionic neurons and mediate ATP nociceptive signals.5,6 Reference P2X3R antagonists include the negatively charged compound A-317491 and the allosteric inhibitors RO-4 (AF-353), RO-85, and AF-219.7−14 2′,3′-O-(2,4,6-Trinitrophenyl)-ATP (TNP-ATP, II, Figure 1A)15,16 is able to inhibit currents evoked by P2X3R agonists at human, rat, and mouse P2X3Rs. Its competitive mechanism of action was confirmed by X-ray studies (Figure 1B).17 In the past few years, we reported ATP analogues acting at the P2X3R as agonists or antagonists.18,19 In particular, modeling studies led to the development of TNP-ATP derivatives (III–V, Figure 1A), presenting cycloalkyl or aromatic rings bound to the 2′,3′-position to replace the trinitrophenyl moiety of TNP-ATP. These compounds showed nanomolar ATP-competitive and reversible (after wash out) inhibitory activity at P2X3Rs expressed on mouse trigeminal ganglion (TG) sensory neurons.19,20 Here, we designed and developed ATP derivatives bearing a smaller 2′,3′-O-substituent (an isopropylidene or methylidene group) compared to derivatives III–V, (6 and 7, Figure 1E, “design 1”). We also developed an analogue of compound III by modifying its triphosphate chain to obtain the metabolically stable α,β-meATP analogue (9, Figure 1E, “design 2”). The novel compounds were evaluated on native P2X3Rs expressed on mouse TG sensory neurons, using the patch clamp technique to record membrane currents. We also tested the compounds’ P2X3R selectivity by studying their ability to modify membrane currents induced by GABAA or 5-HT3 receptors natively expressed by TG neurons. The results of this biological evaluation step suggested compound 7 (Figure 1) as the most potent P2X3R antagonist of the whole series (III–V, 6, 7, 9; see below in Results and Discussion). We hence modified this molecule by replacing the triphosphate chain at the 4′-position with a tetrabenzoic acid moiety (to mimic the P2X3R antagonist A-317491) or with a glutamate residue to maintain the negative charges needed for the interaction with the binding cavity (10 and 13, Figure 1E, “design 3”). All the new compounds and the previously reported analogues III–V were tested on 1321N1 astrocytoma cells stably transfected with the human P2X1R, P2X2R, P2X3R, P2X4R, or P2X7R, respectively, to evaluate their ability to inhibit agonist-induced calcium influx.

Figure 1.

(A) Endogenous P2XR agonist ATP (I), the reference P2X3R antagonist TNP-ATP (II), and the previously reported compounds III–V.19 (B) Superimposition of the binding modes of TNP-ATP (yellow) and A-317491 (green) at the hP2X3R X-ray structure.17 The negatively charged groups of the two compounds occupy analogue position. (C,D) Docking studies of compounds 7 (C) and 10 (D). (E) Compounds designed and developed in this study by modification of the 2′,3′-O-group and/or the triphosphate chain.

Results and Discussion

Molecular Modeling

The X-ray structure of the hP2X3R in complex with TNP-ATP (PDB code: 5SVQ; 3.25 Å resolution17) presents the adenine moiety and the triphosphate chain occupying an analogous position of the same groups of ATP in the agonist-bound P2X3R structure.17 The 2′,3′-trinitrophenyl moiety fills a subpocket located at the interface of two P2X3R monomers (“trinitrophenyl subcavity”). The latter feature appears to be the key point to explain the compound ability to block the receptor rearrangement and activation. We retrieved and refined the hP2X3R-TNP-ATP X-ray structure to use it as target for docking analyses (with the MOE21 software and CCDC Gold22 docking tool) of the first series of designed ATP derivatives, bearing a 2′,3′-O-substituent smaller than the trinitrophenyl moiety of TNP-ATP itself and the 2′,3′-O-substituent of the already reported compounds III–V. The docking conformation of 7 (Figure 1C) is fairly similar to the one of the cocrystallized TNP-ATP, with the phosphate groups giving polar interactions with residues of the binding cavity (i.e., Lys65 and Lys299) and the adenine moiety providing H-bonding with Thr172. The isopropylidene group in the 2′,3′-position only partially fills the “trinitrophenyl subcavity”. Nevertheless, the volume of this group appears sufficient to link the compound to such a conformation within the cavity, thus suggesting analogue antagonist activity of TNP-ATP. Compound 6 presents two possible arrangements within the cavity. One of these conformations is similar to the one of 7 (see above), but the smaller 2′,3′-O-substituent (a methylidene group) provides limited filling of the “trinitrophenyl subcavity”, suggesting a lower activity as P2X3R antagonist. The second conformation represents the 2′,3′-O-substituent being externally oriented, in a compound arrangement similar to the one previously hypothesized for TNP-ATP and compounds III-V.19 In this arrangement, the compound does not fill the “trinitrophenyl subcavity”, suggesting no antagonist activity. Based on the results of patch clamping (see below), reporting nanomolar potency of 7 as P2X3R antagonist, we designed and synthesized its analogues by modifying its triphosphate chain. In detail, the superimposition of the X-ray arrangements of TNP-ATP and A-317491 shows that the triphosphate chain of TNP-ATP and the tetrabenzoic acid moiety of A-317491 occupy the same position (Figure 1B), similarly interacting with polar receptor residues.17 We hence modified 7 by replacing its triphosphate chain with the tetrabenzoic acid moiety of A-317491 (10) and by a glutamate residue, presenting two negatively charged carboxylic functions (13). For both compounds, docking conformations presented a similar arrangement observed for 7, with the negatively charged chains interacting with the positively charged residues of the cavity (Figure 1D, docking conformation of 10).

Chemistry

The new compounds 6, 7, and 9 were synthesized by phosphorylation at the 5′-position of the corresponding nucleosides 4, 5, and 8 (Scheme 1). Commercially available adenosine (Ado; 1) was treated with 4-methoxy-4-trityl chloride in anhydrous pyridine at 60 °C for 1 h, to get the 5′,N6-diprotected derivative 2 with 35% yield, using a modification of the previously reported procedure.23 To compound 2, solubilized in dichloromethane, cetyltrimetylammonium bromide and a solution of sodium hydroxide were added.23 Purification of the mixture by silica gel column chromatography furnished 3 with 82% yield. Treatment of 3 with a solution of hydrochloric acid (0.2 N) furnished the desired 2′,3′-methylene-adenosine (4) with 70% yield.

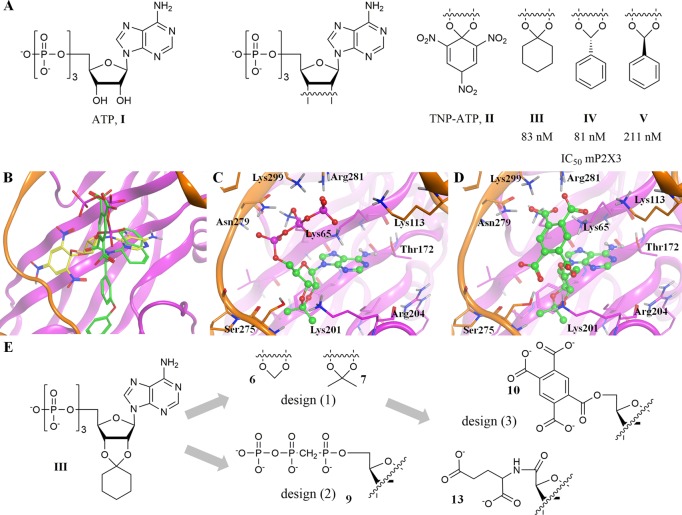

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 4-methoxytritylcloride, 60° C,1 h; (b) CH2Br2, C16H33N(CH3)3Br, NaOH, r.t., 24 h; (c) HCl 0.2 M/CH3CN, r.t., 24 h; (d) i. POCl3, (CH3)3PO dry, 0 °C, 24 h; ii. bis(tri-n-butylammonium) pyrophosphate/DMF dry, 0 °C, 10 min; iii. TEAB 1 M, 0 °C–r.t., 15 min; (e) i. Cl2POCH2POCl2, (CH3)3PO dry, 0 °C–r.t. 4.5 h; ii. tri-n-butylammonium phosphate/DMF dry, Bu3N, r.t., 30 min; iii. TEAB 1 M, 0 °C–r.t., 15 min; (f) i. PMDA/THF, THF, 0 °C, 30 min, r.t., 4 h; ii. HCl 1 N; 32%, yield; (g) TEMPO, BAIB, CH3CN/H2O 1:1, r.t, 4 h, 90%; (h) glutamic acid diethyl ester hydrochloride form, HOBt, EDC, Et3N, r.t., 24 h, 78%; (i) i. K2CO3, CH3OH/H2O 1:1, r.t. 16 h; ii. HCl 1 N to pH = 3, 34%.

The two nucleosides 4 and 5 (commercially available) were in turn reacted with phosphorus oxychloride, in anhydrous trimethyl phosphate. Each reaction was then left for 4 h in anhydrous conditions under a nitrogen gas atmosphere at r.t., and then a solution of bis(tri-n-butylammonium) pyrophosphate in dimethylformamide was added slowly. After cooling down the reaction mixtures in an ice bath, they were blocked by the addition of tetraethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB). Purification in ion exchange Sephadex DEAE A-25 chromatography column eluting with a linear gradient from 0 to 0.4 M of NH4HCO3 furnished the desired ammonium salts of nucleotides 6 and 7, respectively, which were coevaporated with distilled water until complete removal of inorganic salts and then lyophilized.

The stable phosphate nucleotide 9 was prepared from the nucleoside 8.19 Compound 8 was reacted with the methylenebis(phosphonic dichloride) in trimethylphosphate at r.t. for 4.5 h, then to the cooled reaction a solution of n-tributylammonium phosphate in dry DMF and tributylamine were added. The mixture was left under stirring in anhydrous conditions for 30 min, then a cold solution TEAB 1 M was added to quench the reaction. The pure nucleoside triphosphate 9 was obtained after ion exchange column chromatography as reported for 6 and 7. All the new nucleotides were characterized by 1H NMR, 31P NMR, and mass detection.

Finally, 10 and 13 were obtained by coupling the 2′,3′-isopropylidene adenosine (5) directly with the appropriate amino acid derivative or after modification and reaction with a suitable carboxylic congener (Scheme 1). After solubilization in tetrahydrofuran and triethylamine, 5 was treated with a solution of pyromellitic dianhydride in tetrahydrofuran at 0 °C for 30 min and then at r.t. for 4 h. The reaction was then brought to pH 5 by addition of hydrochloric acid (1 N), and the solid residue was purified by reverse phase chromatography to obtain 10 in 32% yield. Compound 5 was then oxidized, using TEMPO/BAIB reaction conditions, to furnish the acid derivative 11 with 90% yield. Compound 11 was reacted with the glutamic acid diethyl ester, in the hydrochloride form, using hydroxy-1-benzotriazole and EDC as condensing agent. The obtained amide derivative 12 was treated with potassium carbonate, furnishing the dicarboxylic acid 13, which was precipitated from the reaction mixture at acidic pH and purified on silica gel chromatography with 34% yield. The two carboxylic derivatives were characterized by 1H NMR and mass spectrometry.

Biological Activity

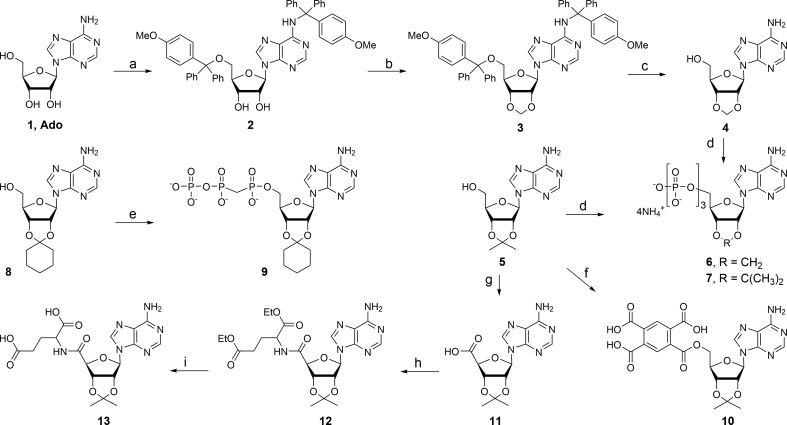

The new nucleotides 6, 7, and 9 were tested for their biological activity on native mP2X3Rs expressed by TG sensory neurons in culture and with the patch clamp recording technique, as previously reported.18,19,24,25 First, the compounds were applied in high concentrations as a brief pulse (2 s) to test their potential agonist activity. The responses were compared to the response of the same cell to the P2X3R reference agonist α,β-meATP at its EC80 concentration26 (10 μM, 2 s) taken as control (100% effect). The current produced by 1 μM 7 was small (23% compared to the control). At 10 μM, 6, 7, and 9 had no agonist activity (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

(A) Test of 6, 7, and 9 as P2X3R agonists. At 10 μM, the three compounds are inactive. N = 5 cells. (B) Concentration–inhibition curves of P2X3R-mediated currents for 7 and 9 built by applying different concentrations of antagonists using 10 μM concentration of α,β-meATP agonist. N = 5–6 cells. The obtained IC50 values were 24 and 127 nM, respectively (Table 1). (C) Reversibility of the antagonist activity. After 5 min application of 7 and 9 at about their IC50 concentrations (0.025 and 0.1 μM), subsequent application of 10 μM α,β-meATP induced smaller peak currents. After 5 min washout, the current amplitude was almost completely restored. (D) Effect of 7 and 9 on GABAA and 5-HT3 receptors. Histograms show GABA and 5-HT current amplitudes in % (normalized to the control current evoked by 10 μM GABA or 10 μM 5-HT). N = 5 cells.

Compounds were then tested as antagonists. As expected, the application of 7 and 9 (applied at a concentration of 0.001, 0.005, 0.1, 1, 10 μM) inhibited subsequent current responses induced by 10 μM α,β-meATP. Compound 6 showed only 25% inhibition at 1 μM (Table 1); hence, it was not tested further. Figure 2B plots the dose response curves for compounds 7 and 9, indicating a complete inhibition by these two compounds of the agonist current and confirming their antagonist profile. The obtained IC50 data are 24 and 127 nM, respectively (Table 1). The 7 and 6 data confirm that the removal of the H-bond donor capability of the 2′,3′-hydroxy functions of ATP by the insertion of an alkyl group generates a loss of the agonist activity at P2X3R; however, the size of the 2′,3′-substituent is critical to achieve potent antagonistic activity at the same receptor. The 9 data also demonstrate that the substitution of the triphosphate chain with the more metabolically stable α,β-methylene-triphosphate group does not affect the P2X3R antagonist potency (compare III and 9, Table 1). The inhibition looked reversible (Figure 2C), with total or partial recovery of the peak current amplitude after 5 min wash out.

Table 1. Antagonistic Activity of Compounds 6, 7, 9, 10, and 13, and the Previously Reported Compounds III–V at P2XRs Determined in Native mP2X3Rs Expressed by TG Sensory Neurons and in 1321N1 Astrocytoma Cells Stably Transfected with the Respective hP2XR Subtype (IC50 ± SEM Expressed in μM, or % Inhibition at Indicated Concentration).

| compound | mP2X3Ra | hP2X1Rb | hP2X2Rc | hP2X3Rd | hP2X4Re | hP2X7Rf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| III | 0.083i | 8.06 ± 1.20 | >100 | 0.883 ± 0.033 | 29.6 ± 5.4 | >100 |

| (20 ± 2%) | (30 ± 15%) | |||||

| IV | 0.081i | ≥10 | >100 | 0.611 ± 0.048 | 11.0 ± 1.77 | 8.53 ± 1.66 |

| (44 ± 1%) | (18 ± 4%) | |||||

| V | 0.211i | >100 | >100 | 5.83 ± 0.79g | 12.4 ± 1.5 | >100 |

| (27 ± 7%) | (16 ± 3%) | (21 ± 10%) | ||||

| 6 | >1.00 | ≫100 | >100 | ≫100 | ≫100 | >100 |

| (25%) | (1 ± 5%) | (36 ± 15%) | (8 ± 3%) | (12 ± 7%) | (21 ± 9%) | |

| 7 | 0.024 ± 0.007 | 41.1 ± 4.7 | >100 | 4.11 ± 2.20g | 48.0 ± 6.9 | ≫100 |

| (6 ± 3%) | (5 ± 8%) | |||||

| 9 | 0.127 ± 0.008 | ≫100 | >100 | 17.5h | ≫100 | ≫100 |

| (−1 ± 5%) | (9 ± 5%) | (−11 ± 3%) | (−1 ± 1%) | |||

| 10 | ND | >10 | >10 | ≥100 | >30 | >30 |

| (13 ± 3%) | (30 ± 3%) | (56 ± 1%) | (35 ± 6%) | (−13 ± 4%) | ||

| 13 | ND | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >30 |

| (21 ± 4%) | (6 ± 2%) | (15 ± 6%) | (−6 ± 3%) | (−9 ± 3%) |

Inhibition of α,β-meATP (10 μM) induced currents (ND = not determined).

Inhibition of calcium influx induced by ATP (3 μM).

Inhibition of calcium influx induced by ATP (3 μM).

Inhibition of calcium influx induced by ATP (0.06 μM).

Inhibition of calcium influx induced by ATP (0.2 μM).

Inhibition of calcium influx induced by Bz-ATP (8 μM); m = mouse; h = human.

n = 2.

n = 1.

ref (19).

Compounds 7 and 9 were also tested at ionotropic GABAA and 5-HT3 receptors of sensory neurons. The currents evoked by the agonists (10 μM GABA or 5-HT) were not significantly modified by 7 or 9 (preapplied at 1 μM), indicating no activity at the GABAA and 5-HT3 receptors (Figure 2D), similarly to their previously reported analogues III–V.19

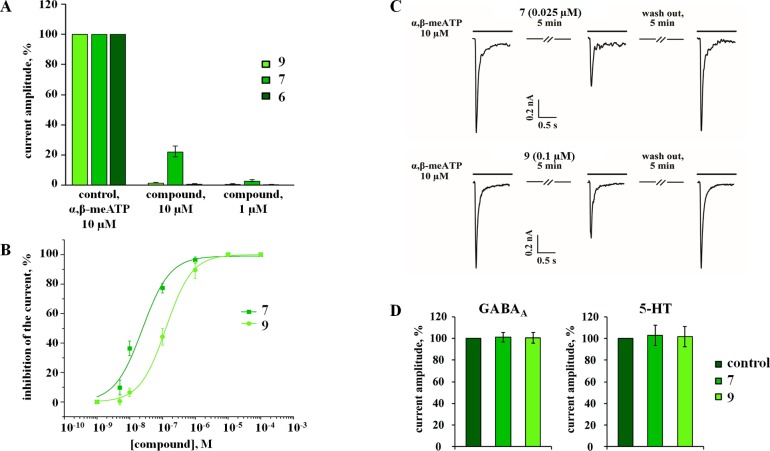

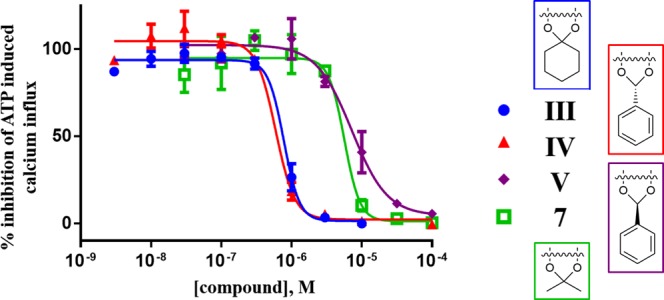

All new compounds as well as the previously reported compounds III–V were tested at human P2X1R, P2X2R, P2X3R, P2X4R, and P2X7R stably expressed in 1321N1 astrocytoma cells for their inhibition of receptor activation induced by agonist (at the respective EC80 concentration), with a protocol as previously reported.27,28 Results are reported in Table 1 as IC50 values (μM) or % inhibition. Results show that compounds III–V, 7, and 9 are endowed with antagonistic activity for the hP2X3R (Figure 3), although they showed different potencies as compared to the IC50 values obtained at the mP2X3R with patch clamping.

Figure 3.

Concentration–response curves of selected compounds at hP2X3R expressed in 1321N1 astrocytoma cells.

For compounds III–V there is an 8- to 30-fold lower potency at the P2X3R, while for compounds 7 and 9 a 170- and 140-fold lower potency was observed, respectively. However, the rank order of potency is similar for both test systems. The different potencies are likely due to very different cell and assay systems and might also be due to species differences.25 Comparing the data at the various subtypes, the results show that the analyzed compounds display a moderate selectivity for the hP2X3R. In particular, III is 10-fold selective vs P2X1R, and IV is 14- and 18-fold selective vs P2X4R and P2X7R, respectively. Compound 7 is 10- and 12-fold selective vs P2X1R and P2X4R, respectively, while 9 appears highly P2X3R selective even if with moderate potency. The results show also the inactivity of 6 at all P2XR subtypes tested. Interestingly, compound V is a similarly potent inhibitor of human P2X3R and P2X4R and highly selective versus all other P2XR subtypes. Such dual-active compounds may be very potent agents for the treatment of chronic pain since both receptor subtypes are involved,29 and blocking both could be additive or even synergistic. Similarly, compound IV may also be very efficient as a multitarget drug due to its blockade of all three P2XR subtypes, P2X3R, P2X4R, and P2X7R. Finally, this assay shows that 10 and 13 are inactive at the P2XRs, contrary to what had been suggested by docking experiments at the level of compound design.

Conclusions

This work shows that the insertion of a substituent in the 2′,3′-position of ATP leads to compounds presenting P2XR antagonist activity, but the size of the 2′,3′-substituent is critical to achieve a significant antagonism. The obtained compounds are generally endowed with high activity and very low selectivity for P2X3R; the dual or multitarget activity of some compounds appears very interesting for the development of pharmacological tools.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- ATP

adenosine-5′-triphosphate

- TG

trigeminal ganglion

- P2XR

P2X receptor

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00524.

Molecular modeling (design), chemistry (synthesis and characterization), biological evaluation (patch clamp and functional studies at P2XRs) (PDF)

Author Contributions

All authors contributed and gave approval to the final version of the manuscript.

C.E.M. is grateful for support by the EU COST Action MuTaLig (multitarget ligands). This work was also supported by Fondo di Ricerca di Ateneo (FPI000033–University of Camerino).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Burnstock G.; Kennedy C. P2X receptors in health and disease. Adv. Pharmacol. 2011, 61, 333–372. 10.1016/B978-0-12-385526-8.00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Physiopathological roles of P2X receptors in the central nervous system. Curr. Med. Chem. 2015, 22, 819–844. 10.2174/0929867321666140706130415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North R. A. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol. Rev. 2002, 82, 1013–1067. 10.1152/physrev.00015.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Ben D.; Adinolfi E. Special Issue: Purinergic P2X receptors: physiological and pathological roles and potential as therapeutic targets. Curr. Med. Chem. 2015, 22, 782–941. 10.2174/092986732207150202151642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bele T.; Fabbretti E. P2X receptors, sensory neurons and pain. Curr. Med. Chem. 2015, 22, 845–850. 10.2174/0929867321666141011195351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda M.; Masuda T.; Tozaki-Saitoh H.; Inoue K. P2X4 receptors and neuropathic pain. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 191. 10.3389/fncel.2013.00191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coddou C.; Yan Z.; Obsil T.; Huidobro-Toro J. P.; Stojilkovic S. S. Activation and regulation of purinergic P2X receptor channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 2011, 63, 641–683. 10.1124/pr.110.003129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambertucci C.; Dal Ben D.; Buccioni M.; Marucci G.; Thomas A.; Volpini R. Medicinal chemistry of P2X receptors: agonists and orthosteric antagonists. Curr. Med. Chem. 2015, 22, 915–928. 10.2174/0929867321666141215093513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller C. E. Emerging structures and ligands for P2X(3) and P2X(4) receptors-towards novel treatments of neuropathic pain. Purinergic Signal. 2010, 6, 145–148. 10.1007/s11302-010-9182-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller C. E. Medicinal chemistry of P2X receptors: allosteric modulators. Curr. Med. Chem. 2015, 22, 929–941. 10.2174/0929867322666141210155610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis M. F.; Burgard E. C.; McGaraughty S.; Honore P.; Lynch K.; Brennan T. J.; Subieta A.; Van Biesen T.; Cartmell J.; Bianchi B.; Niforatos W.; Kage K.; Yu H.; Mikusa J.; Wismer C. T.; Zhu C. Z.; Chu K.; Lee C. H.; Stewart A. O.; Polakowski J.; Cox B. F.; Kowaluk E.; Williams M.; Sullivan J.; Faltynek C. A-317491, a novel potent and selective non-nucleotide antagonist of P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptors, reduces chronic inflammatory and neuropathic pain in the rat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002, 99, 17179–17184. 10.1073/pnas.252537299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gever J. R.; Soto R.; Henningsen R. A.; Martin R. S.; Hackos D. H.; Panicker S.; Rubas W.; Oglesby I. B.; Dillon M. P.; Milla M. E.; Burnstock G.; Ford A. P. AF-353, a novel, potent and orally bioavailable P2X3/P2X2/3 receptor antagonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 160, 1387–1398. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00796.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotherton-Pleiss C. E.; Dillon M. P.; Ford A. P.; Gever J. R.; Carter D. S.; Gleason S. K.; Lin C. J.; Moore A. G.; Thompson A. W.; Villa M.; Zhai Y. Discovery and optimization of RO-85, a novel drug-like, potent, and selective P2X3 receptor antagonist. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 1031–1036. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdulqawi R.; Dockry R.; Holt K.; Layton G.; McCarthy B. G.; Ford A. P.; Smith J. A. P2X3 receptor antagonist (AF-219) in refractory chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet 2015, 385, 1198–1205. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virginio C.; Robertson G.; Surprenant A.; North R. A. Trinitrophenyl-substituted nucleotides are potent antagonists selective for P2X1, P2X3, and heteromeric P2X2/3 receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998, 53, 969–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgard E. C.; Niforatos W.; van Biesen T.; Lynch K. J.; Kage K. L.; Touma E.; Kowaluk E. A.; Jarvis M. F. Competitive antagonism of recombinant P2X(2/3) receptors by 2’, 3′-O-(2,4,6-trinitrophenyl) adenosine 5′-triphosphate (TNP-ATP). Mol. Pharmacol. 2000, 58, 1502–1510. 10.1124/mol.58.6.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansoor S. E.; Lu W.; Oosterheert W.; Shekhar M.; Tajkhorshid E.; Gouaux E. X-ray structures define human P2X3 receptor gating cycle and antagonist action. Nature 2016, 538, 66–71. 10.1038/nature19367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpini R.; Mishra R. C.; Kachare D. D.; Dal Ben D.; Lambertucci C.; Antonini I.; Vittori S.; Marucci G.; Sokolova E.; Nistri A.; Cristalli G. Adenine-Based Acyclic Nucleotides as Novel P2X3 Receptor Ligands. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 4596–4603. 10.1021/jm900131v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Ben D.; Marchenkova A.; Thomas A.; Lambertucci C.; Spinaci A.; Marucci G.; Nistri A.; Volpini R. 2’,3′-O-Substituted ATP derivatives as potent antagonists of purinergic P2X3 receptors and potential analgesic agents. Purinergic Signal. 2017, 13, 61–74. 10.1007/s11302-016-9539-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Ben D.; Buccioni M.; Lambertucci C.; Marucci G.; Thomas A.; Volpini R. Purinergic P2X receptors: structural models and analysis of ligand-target interaction. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 89, 561–580. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular Operating Environment; Chemical Computing Group: Montreal, Quebec, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Jones G.; Willett P.; Glen R. C.; Leach A. R.; Taylor R. Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. J. Mol. Biol. 1997, 267, 727–748. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman D. G.; Reese C. B.; Serafinowska H. T. 2′,3′-O-Methylene Derivatives of Ribonucleosides. Synthesis 1985, 1985, 751–754. 10.1055/s-1985-31332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simonetti M.; Fabbro A.; D’Arco M.; Zweyer M.; Nistri A.; Giniatullin R.; Fabbretti E. Comparison of P2X and TRPV1 receptors in ganglia or primary culture of trigeminal neurons and their modulation by NGF or serotonin. Mol. Pain 2006, 2, 11. 10.1186/1744-8069-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundukova M.; Vilotti S.; Abbate R.; Fabbretti E.; Nistri A. Functional differences between ATP-gated human and rat P2X3 receptors are caused by critical residues of the intracellular C-terminal domain. J. Neurochem. 2012, 122, 557–567. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova E.; Skorinkin A.; Fabbretti E.; Masten L.; Nistri A.; Giniatullin R. Agonist-dependence of recovery from desensitization of P2X(3) receptors provides a novel and sensitive approach for their rapid up or downregulation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 141, 1048–1058. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Olmos V.; Abdelrahman A.; El-Tayeb A.; Freudendahl D.; Weinhausen S.; Muller C. E. N-substituted phenoxazine and acridone derivatives: structure-activity relationships of potent P2X4 receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 9576–9588. 10.1021/jm300845v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelrahman A.; Namasivayam V.; Hinz S.; Schiedel A. C.; Kose M.; Burton M.; El-Tayeb A.; Gillard M.; Bajorath J.; de Ryck M.; Muller C. E. Characterization of P2X4 receptor agonists and antagonists by calcium influx and radioligand binding studies. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 125, 41–54. 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier L. P.; Ase A. R.; Seguela P. P2X receptor channels in chronic pain pathways. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 2219–2230. 10.1111/bph.13957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.