Abstract

AR-C155858 and AZD3965, pyrrole pyrimidine derivatives, represent potent monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) inhibitors, with potential immunomodulatory and chemotherapeutic properties. Currently, there is limited information on the inhibitory properties of this new class of MCT1 inhibitors. The purpose of this study was to characterize the concentration- and time-dependent inhibition of L-lactate transport and the membrane permeability properties of AR-C155858 and AZD3965 in the murine 4T1 breast tumor cells that express MCT1. Our results demonstrated time-dependent inhibition of L-lactate uptake by AR-C155858 and AZD3965 with maximal inhibition occurring after a 5-min pre-incubation period and prolonged inhibition. Following removal of AR-C155858 or AZD3965 from the incubation buffer, inhibition of L-lactate uptake was only fully reversed after 3 and 12 h, respectively, indicating that these inhibitors are slowly reversible. The uptake of AR-C155858 was concentration-dependent in 4T1 cells, whereas the uptake of AZD3965 exhibited no concentration dependence over the range of concentrations examined. The uptake kinetics of AR-C155858 was best fitted to a Michaelis-Menten equation with a diffusional clearance component, P (Km = 0.399 ± 0.067 μM, Vmax = 4.79 ± 0.58 pmol/mg/min, and P = 0.330 ± 0.088 μL/mg/min). AR-C155858 uptake, but not AZD3965 uptake, was significantly inhibited by alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid, a known nonspecific inhibitor of MCTs 1, 2, and 4. AR-C155858 demonstrated a trend toward higher uptake at lower pH, a characteristic of proton-dependent MCT1. These findings provide evidence that AR-C155858 and AZD3965 exert slowly reversible inhibition of MCT1-mediated L-lactate uptake in 4T1 cells, with AR-C155858 representing a potential substrate of MCT1.

Keywords: AR-C155858, AZD3965, Monocarboxylate transporter 1, L-lactate, MCT1 inhibitor

INTRODUCTION

The rapid transport of L-lactic acid across the plasma membrane is mediated by 4 proton-linked monocarboxylate transporters, MCT1–4, which are part of the solute carrier SLC16A gene family (1–4). MCT1, by far the best characterized isoform, is expressed extensively throughout the body (5) and it is involved in bidirectional transport of a number of monocarboxylates including L-lactate (6). MCT2 is an uptake transporter with higher affinity, but its expression is restricted to certain tissues (7). MCT4 is a low-affinity lactate transporter and it is expressed mainly in glycolytic tissues, where it facilitates lactic acid efflux (8,9).

Aside from their physiological role in lactic acid transport and pH homeostasis, MCT1 and MCT4 are of interest as therapeutic targets in cancer (10–13). A key metabolic alteration in cancer is enhancement in the rate of glycolysis, which results in production of lactic acid and changes in intracellular pH. Overexpression of MCT1 and/or MCT4 have been reported in various human cancers, including breast cancer, where its expression is correlated with poor prognosis and survival (14–16). Furthermore, MCT4 has been demonstrated to be regulated by hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1 α), a key transcription factor known to be responsible for enabling tumor cells to adapt to hypoxic conditions and maintain tumor growth (17–19). In this context, MCT1 and/or MCT4 have been proposed as potential therapeutic targets in cancer. Studies with inhibitors of MCTs and silencing RNAs have provided proof of concept that inhibiting MCTs can reduce tumor growth in a number of human cancer xenograft models (20–25). However, many of these inhibitors such as alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHC) lack potency and specificity (2,26).

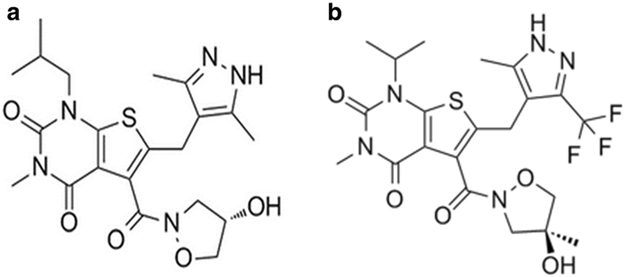

Recently, a new class of specific and potent inhibitors of MCT1 have been developed by AstraZeneca as immunosuppressant agents to potently inhibit T lymphocyte proliferation (27,28). It was later identified that these compounds inhibit MCT1-mediated lactic acid efflux during T lymphocyte proliferation (27–29). One of these compounds, AR-C155858 (Fig. 1a), demonstrated potent inhibition of MCT1 with a Ki value of 2.3 nM in rat erythrocytes that express endogenous MCT1. AR-C155858 was also reported to inhibit MCT2, but to a lesser extent (Ki > 10 nM), in studies of MCT2-transfected Xenopus laevis oocytes (30,31). AZD3965 (Fig. 1b), an analogue of AR-C155858, is an orally bioavailable inhibitor of MCT1 that is currently being investigated in a phase I clinical trial in the UK for advanced solid tumors and lymphomas (NCT01791595). AZD3965 shows similar potency and specificity as AR-C155858, with 6-fold higher potency for MCT1 compared with MCT2, and no inhibition of MCT3/MCT4 at 10 μM (23). AZD3965 has been demonstrated to significantly decrease cell and tumor growth in human small-cell lung cancer and various lymphoma xenograft models that overexpress MCT1 (21–23,32,33).

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of AR-C155858 (a) and AZD3965 (b)

Previous work from our laboratory has shown that inhibition by AR-C155858 was time-dependent and not rapidly reversible (34). The mode of action by AZD3965 is largely unknown and has not been studied. The objective of our current study was to further characterize the properties of AR-C155858 and AZD3965 in the murine 4T1 breast tumor cells, a relevant cell system to study MCT1 that is highly conserved across species (35), as it expresses MCT1, but not MCT2 or MCT4 (36). We evaluated the time-dependent inhibition of L-lactate uptake by AR-C155858 and AZD3965 as well as the reversibility of the inhibition. Our current study also sought to characterize the cellular uptake of AR-C155858 and AZD3965 and determine if these inhibitors are also MCT1 substrates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and Reagents

L-lactate (as calcium salt) and alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHC) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). AZD3965 and AR-C155858 were obtained from AstraZeneca, MedKoo Biosciences (Chapel Hill, NC), and Chemscene (Monmouth Junction, NJ), respectively. L-[3H] lactate was purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO).

Cell Culture

Mouse mammary tumor, 4T1 cells were kindly provided by Dr. Elizabeth A. Repasky (Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2/95% air. The 4T1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units penicillin, and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin. Culture medium was changed every 2–3 days, and cells were passaged with 0.25% trypsin/EDTA.

Cellular L-Lactate Uptake Studies

The 4T1 cells were plated in 35-mm (diameter) culture dishes at a cell density of 2.0 × 105 cells/mL 2 days before the uptake study. On the day of the experiment, the culture medium was removed and cells were washed three times followed by equilibration for 20 min at 37 °C with the uptake buffer containing 137 mM N-methyl-D-glucamine, 5.4 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM HEPES at pH 6.0 and 7.4. pH 6.0 was used to drive the transport by MCT1, as transport is dependent on the proton gradient. pH 7.4 represents the physiologically relevant blood pH and was used for comparison. Cells were pre-incubated with the inhibitors at 37 °C and subsequently cooled to room temperature (RT) for 5 min. Cells were then incubated in 1 mL of uptake buffer containing [3H]-L-lactate and 0.5 mM of cold L-lactate for 1 min at RT. A reaction time of 1 min was used because it was determined that 1 min is within the time range of linear uptake of L-lactate in 4T1 cells. The uptake was terminated by aspirating the uptake buffer, followed by washing the cells rapidly three times with ice-cold buffer. Cells were lysed in 0.5 mL of 1.0 N NaOH for 1 h at RT and the cell lysates were neutralized with 0.5 mL of 1.0 N HCl. Scintillation fluid (3 mL) was added to 400 μL of cell lysate, and the radioactivity was measured by liquid scintillation counting (1900 CA, Tri-carb liquid scintillation analyzer, Packard Instrument Co., Doners Grove, IL). Protein concentrations were determined using BCA protein assay kit (BCA, Pierce Chemicals, Rockford, IL). All the results were normalized to total protein content and were expressed as pmol/mg protein/min or pmol/mg protein.

To examine time-dependent inhibition, cells were pre-incubated with AR-C155858 or AZD3965 (200 nM) in uptake buffer for 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, 15, 30, 45, 60, 120, 180, and 300 min. Cells were treated with AR-C155858 and AZD3965 (200 nM) under various conditions: (1) uptake of L-lactate alone (control), (2) pretreatment with the inhibitor for 30 min at 37 °C followed by uptake of L-lactate, and (3) pretreatment with the inhibitor for 30 min at 37 °C followed by washing the cells three times with ice-cold buffer and uptake of L-lactate. To study time-dependent reversibility of inhibition, the inhibition of L-lactate by AR-C15585 and AZD3965 (200 nM) was assessed at various times (0, 15, 30 min, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h) after the removal of the inhibitors by washing the cells three times with ice-cold buffer. After the removal of the inhibitors, cells were maintained in serum-free medium at 37 °C. At the designated time point, culture medium was removed and uptake reaction of L-lactate was carried out as described earlier.

Cellular AR-C155858 and AZD3965 Uptake Studies

Since the proposed mechanism of inhibition by AR-C155858 involves slow membrane permeability before it inhibits MCT1 by binding at an intracellular site (30,37), we further studied the inhibitory properties of AR-C155858 and AZD3965 by determining whether these inhibitors represent substrates for MCT1, and not just inhibitors. Cellular AR-C155858 and AZD3965 uptake studies were conducted similarly as in the L-lactate uptake studies. Briefly, cells were plated in 35 mm (diameter) culture dishes at a cell density of 2.0 × 105 cells/mL, 2 days before the uptake study. On the day of the experiment, culture medium was removed and cells were washed three times, followed by equilibration for 20 min at 37 °C in the uptake buffer or serum-free medium. To determine time-dependent uptake, cells were incubated with uptake buffer (1 mL) containing 30 or 50 nM of AR-C155858 or AZD3965, respectively, for 1, 3, 5, 7, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min. From these studies, 2 and 5 min time points were chosen to represent the linear uptake of AR-C155858 and AZD3965, respectively, at RT. To determine concentration-dependent uptake of AR-C155858 and AZD3965, the concentration ranged from 0 to 10 μM. The uptake was terminated by aspirating the uptake buffer or serum-free medium and the cells were rapidly washed three times with ice-cold buffer. Cells then were lysed in 0.5 mL of methanol/water (5/95 ν/ν), frozen at − 80 °C for 30 min, followed by thawing on a shaker for 1 h at 4 °C. All the samples were stored at − 80 °C until analysis. Protein concentrations were determined using BCA assay kit. All the results were normalized to total protein content and were expressed as pmol/mg protein/min or pmol/mg protein.

To determine the driving force for AR-C155858 uptake, the effects of pH and sodium were examined. For pH-dependent uptake, cells were incubated with uptake buffer containing 30 nM of AR-C155858 at pH 5.0, 5.5, 6.0, 6.5, 7.0, and 7.4 for 2 min. For sodium-dependent uptake of AR-C155858, cells were incubated with uptake buffer containing 30 nM of AR-C155858 in the presence and absence of sodium at both pH 6.0 and 7.4. For sodium-dependent studies, the N-methyl-D-glucamine in the uptake buffer was replaced with 137 mM NaCl. To determine the effects of MCT inhibition on AR-C155858 and AZD3965 uptake, cells were pre-incubated with 20 mM of CHC for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by the determination of uptake of AR-C155858 and AZD3965, present at varying concentrations.

Cell Lysate Sample Preparation and LC/MS/MS Analysis

Cellular AR-C155858 and AZD3965 concentrations were measured using previously developed and validated liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) assay of AZD3965 in mouse plasma and tumor tissue (38). Briefly, AR-C155858 samples were prepared by adding 5 μL of the internal standard (I.S.), AZD3965 (2 ng/mL), to 55 μL of cell lysate samples. For AZD3965, samples were prepared by 5 μL of the I.S., AR-C155858 (8 ng/mL), to 35 μL of cell lysate samples. Standards and quality controls for AR-C155858 were prepared by adding 5 μL of I.S. and 5 μL of AR-C155858 stock solutions to 50 μL of blank cell lysate. Standards and quality controls for AZD3965 were prepared by adding 5 μL of I.S. and 5 μL of AZD3965 stock solutions to 30 μL of blank cell lysate. Cell lysate proteins were precipitated by adding 600 μL of 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. Samples were vortexed and then centrifuged at 10,000×g for 20 min at 4 °C. Supernatant (540 μL) was collected and evaporated under a stream of nitrogen gas, followed by reconstitution in 200 μL of acetonitrile/water (40/60, ν/ν).

The LC/MS/MS assay for AR-C155858 and AZD3965 was validated in the cell lysate using a Shimadzu Prominence HPLC with binary pump and autosampler (Shimadzu Scientific, Marlborough, MA), connected to a Sciex API 3000 triple quadruple tandem mass spectrometer with utilizing Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) source (Sciex, Foster City, CA). Chromatographic separation was obtained by injecting 15 μL of the sample on to an Xterra MS C18 column (250 × 2.1 mm i.d., 5-μm particle size; Waters, Milford, MA). Mobile phase A consisted of acetonitrile/water (5/95, ν/ν) with 0.1% acetic acid and mobile phase B contained acetonitrile/water (95/5, ν/ν) with 0.1% acetic acid. The flow rate was 250 μL/min with a gradient elution profile and a total run time of 15 min. The mass spectrometer was operated in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode utilizing APCI source. Q1/Q3 m/z ratio for the precursor/product ion of AR-C15585 and AZD3965 was 462.3/373.2 and 516.4/413.2, respectively. The retention time for AZD3965 and AR-C155858 were 5.77 and 4.91 min, respectively. The data were analyzed using Analyst version 1.4.2 (Sciex, Foster City, CA).

Regression analyses of peak area ratios of AR-C155858/AZD3965 to AR-C155858 concentrations and AZD3965/AR-C155858 to AZD3965 concentrations were used to assess linearity of the calibration curve for AR-C155858 and AZD3965, respectively. The intra-day and inter-day precision and accuracy were determined using quality control (QC) samples. Low-, medium-, and high-QC samples were prepared to yield concentrations of 0.75, 6, and 15 ng/mL for the AR-C155858 calibration curve and 2, 30, and 70 ng/mL for the AZD3965 calibration curve. For intra-day precision and accuracy, quality control samples were analyzed in triplicate on each day. For the inter-day precision and accuracy, quality control samples were analyzed over three different days. A calibration curve was run on each analysis day along with the quality controls and the curve was analyzed using 1/χ weighted least squares linear regression analysis (χ = concentration). The precision was determined by the coefficient of variation, and accuracy was measured by comparing the calculated concentration with the known concentration. The recoveries of the AZD3965 and AR-C155858 were determined by comparing the peak areas of extracted standard samples with the peak areas of post-extraction cell lysate spiked at the corresponding QC concentrations (low, middle, and high).

Data Analysis

All the data are presented as mean ± SD. Data analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Depending on the number of groups and variances, data were compared using a Student’s t test, oneway ANOVA followed with Dunnett’s post hoc test comparisons, or two-way ANOVA followed with Bonferroni’s post hoc comparisons. Significant differences were based on the criterion P < 0.05. The transport kinetic parameters, Michaelis-Menten constant Km, maximal velocity Vmax, and diffusional clearance P, were determined using the following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where ν is the rate of AR-C155858 uptake and CAR-C155858 is the concentration of AR-C155858.

All the parameters were determined using weighted nonlinear regression analysis (ADAPT 5 Biomedical Simulations Resource (BMSR), University of South California, Los Angeles, CA). Goodness of fit was determined by the sum of squared derivatives, residual plot, and Akaike information criterion (AIC). Equation 2 yields the smallest coefficient of variation percentage and AIC value, and was subsequently used to estimate kinetic uptake parameters.

RESULTS

Time-Dependent Inhibition by AR-C155858 and AZD3965

Figure 2a, b demonstrate the time-dependent inhibition of L-lactate uptake by AR-C155858 and AZD3965, respectively, in 4T1 cells. Maximal inhibition was observed following 5-min pre-incubation at 37 °C with either one of the inhibitors, and the inhibition was sustained up to 5 h.

Fig. 2.

The time-dependent inhibition of L-lactate (0.5 mM) uptake by AR-C155858 (a) and AZD3965 (b) at 37 °C, pH 6.0, at a concentration of 200 nM. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3

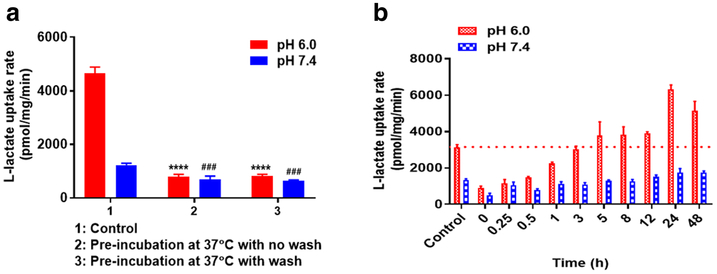

Reversibility of Inhibition by AR-C155858 and AZD3965

To study whether the inhibition by AR-C155858 and AZD3965 can be reversed by removing bound inhibitor on the cell surface (via washing the cells three times with ice-cold buffer), we chose to pre-incubate the cells with the inhibitors for 30 min at 37 °C followed by uptake of L-lactate (0.5 mM). This approach of washing the cells with ice-cold buffer was adopted from Harker et al. as they have shown previously that washing can readily remove a large quantity of loosely associated and nonspecifically bound doxorubicin from the cell surface (39). Incubation buffers at pH 6.0 or 7.4 were used in these studies. Uptake of L-lactate at pH 6.0 and 7.4 was significantly inhibited by AR-C155858 and AZD3965 in the presence or absence (after removal) of the inhibitors (Fig. 3a, b). For AR-C155858 at pH 6.0, there was 81.8% and 80.5% inhibition with and without washing the cells with ice-cold buffer to remove the inhibitor, respectively (Fig.3a). Similarly, at pH 6.0, AZD3965 demonstrated 83.5% and 86.6% inhibition with and without removal of the inhibitor, respectively (Fig. 3b). These results demonstrated that the removal of the inhibitor by washing the cells three times with ice-cold buffer did not reverse the inhibition of L-lactate uptake, suggesting tight binding of the inhibitors and that inhibition by AR-C155858 and AZD3965 is only slowly reversible. We further evaluated the time needed to completely reverse the inhibition. Here, we investigated the amount of L-lactate uptake at various times after the removal of the inhibitors via washing the cells with ice-cold buffer. We demonstrated that to completely reverse the inhibition of L-lactate uptake at pH 6.0 by AR-C155858 and AZD3965, it took 3 and 12 h, respectively (Fig. 3c, d).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of L-lactate uptake by AR-C15585 and AZD3965 at pH 6.0 and 7.4 in the 4T1 cells. The effect of L-lactate (0.5 mM) uptake under various AR-C155858 (a) and AZD3965 (b) (200 nM) treatment conditions: (1) uptake of L-lactate alone, (2) pretreatment with the inhibitor followed by uptake of L-lactate, (3) pretreatment with the inhibitor followed by washing the cells three times with ice-cold buffer and uptake of L-lactate. The inhibition of L-lactate uptake by AR-C155858 (c) and AZD3965 (d) (200 nM) at various times after the removal of the inhibitors, as in treatment condition (3). Dotted line represents time to return back to the baseline of L-lactate uptake at pH 6.0 baseline of L-lactate uptake alone at pH 6.0 (c) and (d). The reference line for AR-C155858 (c) was based on the baseline from the study with AZD3965 (d). ****P < 0.0001 compared to the control at pH 6.0; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 compared to the control at pH 7.4. Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3

Additionally, the reversibility of inhibition by AR-C155858 was confirmed in HCC1937 cells (a human breast cancer cell line that expresses both MCT1 and MCT4) (Fig. 4a, b). Interestingly, we observed an overshoot phenomenon of L-lactate uptake beyond the baseline level after the complete abolishment of the inhibition by AR-C155858 and AZD3965 (Figs. 3c, d and 4b). Together, these results showed that AR-C155858 and AZD3965 are slowly reversible and that the inhibition of L-lactate uptake by AZD3965 was sustained longer than AR-C155858.

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of L-lactate uptake by AR-C15585 at pH 6.0 and 7.4 in the HCC1937 cells that express both MCT1 and MCT4. The effect of L-lactate (0.5 mM) uptake under various AR-C155858 (a) (200 nM) treatment conditions: (1) uptake of L-lactate alone, (2) pretreatment with the inhibitor followed by uptake of L-lactate, (3) pretreatment with the inhibitor followed by washing the cells three times with ice-cold buffer and uptake of L-lactate. The inhibition of L-lactate uptake by AR-C155858 (200 nM) at various times after the removal of the inhibitor, as in treatment condition (3). Dotted line represents time return back to the baseline of L-lactate uptake alone at pH 6.0 (b). ****P < 0.0001 compared to the control at pH 6.0; ###P < 0.001 compared to the control at pH 7.4. Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3

Cell Lysate AR-C155858 and AZD3965 LC/MS/MS Assay

From the AR-C15585 and AZD3965 LC/MS/MS assays, the lower limits of quantification for AR-C155858 and AZD3965 in cell lysates were found to be 0.1 and 0.15 ng/mL, respectively, with good precision and accuracy. The calibration curve range for AR-C155858 was from 0.1 to 25 ng/mL based on regression analysis of peak areas to AR-C155858 concentrations with a correlation coefficient (r2) > 0.999. The calibration curve range for AZD3965 was from 0.15 to 100 ng/mL based on regression analysis of peak areas to AR-C155858 concentrations with r2 > 0.999. The recovery and intra-day and inter-day precision and accuracy of the quality control samples are summarized in Table I.

Table I.

AR-C155858 and AZD3965 Recovery, Intra- and Inter-day Accuracy, and Precision in 4T1 Cell Lysates

| Analyte | Nominal concentration (ng/mL) |

Intra-day |

Inter-day |

Recovery | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (ng/mL) |

SD | Precision (CV%) |

Accuracy (%) |

Mean (ng/mL) |

SD | Precision (CV%) |

Accuracy (%) |

(%) | ||

| AR-C155858 | 0.75 | 0.70 | 0.02 | 2.66 | 92.8 | 0.69 | 0.01 | 1.24 | 91.7 | 102 |

| 6 | 5.96 | 0.46 | 7.66 | 99.3 | 5.92 | 0.32 | 5.41 | 98.6 | 93.3 | |

| 15 | 14.8 | 0.82 | 5.53 | 98.7 | 15.4 | 0.46 | 3.10 | 99.5 | 89.9 | |

| AZD3965 | 2 | 2.03 | 0.08 | 3.72 | 102 | 2.06 | 0.02 | 1.28 | 103 | 100 |

| 30 | 31.9 | 1.04 | 3.27 | 106 | 32.1 | 0.18 | 0.57 | 107 | 101 | |

| 70 | 75 | 0.56 | 0.74 | 107 | 76.8 | 1.60 | 2.08 | 110 | 102 | |

The measured concentrations represent mean of triplicate measurements. The analyses were performed over 3 days

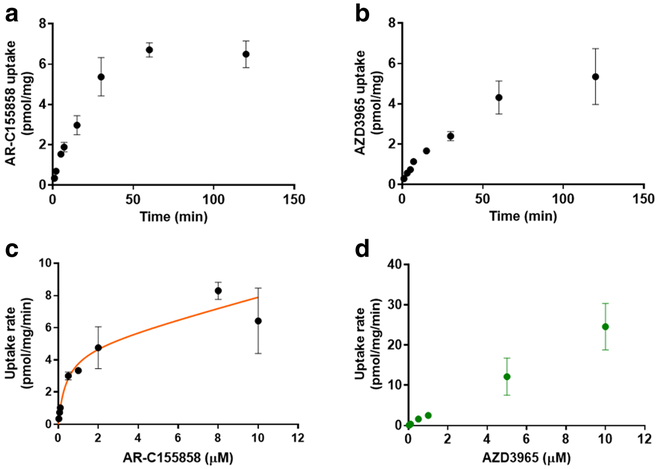

Uptake of AR-C155858 and AZD3965 in 4T1 Cells

Given that the proposed mechanism of inhibition by AR-C155858 involves slow membrane permeability and binding to MCT1 at an intracellular membrane site (30,37), our current study further evaluated whether AR-C155858 and AZD3965 are substrates of MCT1. Here, the uptake of AR-C155858 and AZD3965 in 4T1 cells was investigated at physiological pH (7.4) in serum-free medium. The uptake of 30 nM AR-C155858 and 50 nM AZD3965 by 4T1 cells were examined over time at RT, up to 2 h (Fig. 5a, b). The uptake rates of AR-C155858 and AZD3965 were linear up to 5 and 7 min, respectively. The uptake studies were carried out at RT because we demonstrated that the rates of uptake of AR-C155858 and AZD3965 were rapid at 37 °C (data not shown). From these studies, 2 and 5 min were chosen for the uptake time of AR-C155858 and AZD3965, respectively. Concentration-dependent studies were performed for AR-C155858 (0.03 to 10 μM) and AZD3965 (0.05 to 10 μM). Our results in 4T1 cells showed that the uptake of AR-C155858 exhibited saturable kinetics (Fig. 5c), whereas the uptake of AZD3965 demonstrated passive diffusion and no saturation was observed up to 10 μM (Fig. 5d). The concentration-dependent uptake of AR-C155858 was best fitted to a Michaelis-Menten equation with a passive diffusion component (Km = 0.399 ± 0.067 μM, Vmax = 4.79 ± 0.58 pmol/mg/min, and P = 0.330 ± 0.088 μL/mg/min) (Fig. 5c and Table II).

Fig. 5.

The AR-C155858 and AZD3965 uptake in the 4T1 cells at physiological pH (serum-free medium). The time-dependent uptake of AR-C155858, 30 nM (a) and AZD3965, 50 nM (b). The concentration-dependent uptake of AR-C155858 (c) and AZD3965 (d). The uptake of AR-C-155858 and AZD3965 was carried out for 2 and 5 min, respectively. The concentration-dependent uptake of AR-C155858 was best fitted to a Michaelis-Menten equation with a diffusional uptake clearance component (P). Observed mean data are shown by symbols and the line represents model fitted results. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3–6

Table II.

AR-C155858 Uptake Kinetic Parameter Estimates in 4T1 Cells

| Parameter | Mean ± SD | CV% |

|---|---|---|

| Vmax (pmol/mg/min) | 4.79 ± 0.58 | 12.2 |

| Km (μM) | 0.399 ± 0.067 | 16.7 |

| P (μL/mg/min) | 0.330 ± 0.088 | 26.8 |

n = 3

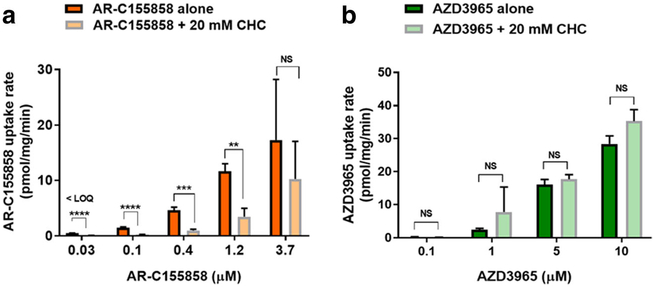

Effect of CHC on the Uptake of AR-C155858 and AZD3965

Since the uptake of AR-C155858 in 4T1 cells were demonstrated to be saturable, we further evaluated whether the uptake can be inhibited by CHC, a well-characterized nonspecific inhibitor of MCT1–4. Interestingly, CHC (20 mM) significantly inhibited AR-C155858 uptake at 0.03, 0.1, 0.4, and 1.2 μM but not at a higher concentration, 3.7 μM (Fig. 6a), suggesting that AR-C155858 may be a substrate for MCT1 in 4T1 cells. In contrast, CHC (20 mM) did not significantly inhibit AZD3965 uptake at 0.1, 1, 5, and 10 μM (Fig. 6b), indicating that AZD3965 is likely passively taken up into the 4T1 cells.

Fig. 6.

The effect of CHC on the cellular uptake of AR-C155858 and AZD3965 in 4T1 cells. The uptake of AR-C155858 (a) and AZD3965 (b) in the absence and presence of CHC (20 mM) at physiological pH (serum-free medium). Cells were pre-incubated with CHC for 30 min at 37 °C followed by uptake of AR-C155858 or AZD3965 at RT for 2 or 5 min, respectively. NS nonsignificant; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001 compared to the uptake AR-C155858 or AZD3965 in the absence of CHC. Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3

Effect of pH and Sodium on the Uptake of AR-C155858

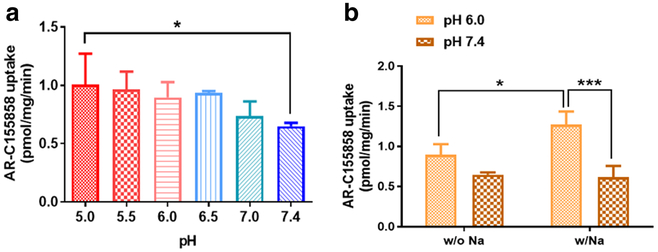

The uptake of AR-C155858 at pH 5.0, 5.5, 6.0, 6.5, and 7.0 were compared to that at pH 7.4. Of all the pH values examined, only pH 5.0 showed significantly higher uptake than at pH 7.4 (Fig. 7a). The effect of sodium on the uptake of AR-C155858 in 4T1 cells was evaluated at pH 6.0 and pH 7.4. At pH 6.0, the uptake of AR-C155858 was significantly higher with sodium than without sodium; however, there was no significant difference in the presence and absence of sodium at pH 7.4 (Fig. 7b). In the presence of sodium, the uptake of AR-C155858 was significantly higher at pH 6.0 than at pH 7.4 (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7.

The effect of pH and sodium on the uptake of AR-C155858 in 4T1 cells. The uptake of AR-C155858 (30 nM) at various pH (a) and in the presence or absence of sodium (b). *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3

DISCUSSION

AZD3965, a pyrrole pyrimidine derivative and an analogue of AR-C155858, is a first-in-class monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) inhibitor that is currently being investigated in a phase I clinical trial in the UK for advanced solid tumors and lymphomas (NCT01791595). AR-C155858 and AZD3965 are potent MCT1 inhibitors with Ki values of 2.3 and 1.6 nM, respectively (30,40). A proposed mechanism of inhibition by AR-C155858 has previously been reported, which involved binding of AR-C155858 to the transmembrane helices 7–10 of MCT1 from the intracellular side at key residue sites involved in the substrate binding and translocation cycle of MCT1 (30). Prior to gaining access to its inhibitory binding site, it was proposed that AR-C155858 undergoes slow membrane permeability to reach the cytosolic side (30,37). A previous publication from our laboratory showed that removing AR-C155858 from cells by washing did not reverse the inhibition of gamma hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) uptake, a known substrate of MCT1, 2, and 4, in rat kidney KNRK cells (34). The inhibitory properties of AZD3965 remain largely unknown. In the current study, we further characterized the inhibitory properties of AR-C155858 and AZD39654 and evaluated whether these inhibitors are substrates for MCT1 in the murine 4T1 breast tumor cell line that we previously have shown to express only MCT1, but not MCT2 or MCT4, on the plasma membrane (36).

We examined the time-dependent inhibition of L-lactate uptake by AR-C155858 and AZD3965. Our results indicated that AR-C155858 and AZD3965 exhibit prolonged inhibition. Different from previous studies, we observed a maximum inhibition following a 5-min pre-incubation time with both of the inhibitors as opposed to 30 and 45 min with AR-C155858 (100 nM) at RT in the rat kidney KNRK cells and Xenopus laevis oocytes transfected with MCT1, respectively (30,34). This discrepancy may be due to the higher pre-incubation temperature (37 °C) used in our current study. Nevertheless, our data demonstrated a rapid and prolonged inhibition by AR-C155858 and AZD3965.

To better understand the mechanism of inhibition by AR-C155858 and AZD3965, we evaluated the reversibility of inhibition. Consistent with our previous study (34), we showed that washing the cells three times with ice-cold buffer to remove the inhibitors did not abolish their effects. Interestingly, we found that it required 3 and 12 h to completely reverse the inhibition of L-lactate uptake by AR-C155858 and AZD3965, respectively, indicating that these inhibitors are slowly reversible. This slowly reversible inhibition was further confirmed utilizing a different cell system, the human HCC1937 breast cancer cell line where both MCT1 and MCT4 are present. Our results here are supported by clinical evidence that the side effects of AZD3965, such as retinal impairment measured by electro-retinogram, were found to be reversible and asymptomatic (41). Under our current experimental conditions, another interestingly aspect we observed here was an overshoot phenomenon of L-lactate uptake beyond the baseline level after the removal of the inhibitors, when examined at later times. While it is not known why we observed higher L-lactate concentrations, it may be a result of starvation of the cells in the serum-free medium for a long period of time (42), or due to inhibition of the efflux of L-lactate at later times, since MCT1 transport can be bidirectional depending on the driving force.

CHC represents a known and well-characterized nonspecific inhibitor of MCT1, 2, and 4 for which there are both in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrating activity against MCTs (2,26,43–45). Here, we demonstrated that AZD3965 (up to 10 μM) passively diffuses into 4T1 cells and the uptake cannot be inhibited by CHC, indicating that the uptake of AZD3965 is not carrier mediated and does not involve MCT1-mediated transport, under our experimental conditions. In contrast, AR-C155858 demonstrated saturable uptake in 4T1 cells. This is consistent with the greater lipophilicity of AZD3965 (log P of 1.78 versus 1.53 for AR-C155858). While these two compounds are similar in chemical structure and the difference in the log P is relatively small, AZD3965 is orally bioavailable (nearly complete oral bioavailability in mice from our unpublished data) as opposed to 4% oral bioavailability of AR-C155858 reported in rats (28). While the mechanism underlying the differences in oral bioavailability is unknown, these findings suggest potential differences in membrane permeability or transport and first-pass extraction.

A previous report suggested that the inhibition by AR-C155858 involved an initial transient binding to MCT1 before AR-C155858 can “shuttle” across the plasma membrane and gain access to its final binding site from the intracellular side (37). To investigate whether AR-C155858 is a substrate for the proton-dependent MCT1 present in 4T1 cells, we evaluated the effect of the MCT inhibitor CHC, and the effect of pH on the uptake of AR-C155858. Our results here demonstrated significant inhibition of AR-C155858 uptake by CHC, and a trend toward higher uptake of AR-C155858 at lower pH, with the uptake at pH 5.0 being significantly greater than at pH 7.4. As pH dependence is characteristic of MCT1-mediated transport, and MCT1 transport can be inhibited by CHC, our findings suggest that AR-C155858 may be a MCT1 substrate. Further studies utilizing MCT1 knockdown via siRNA will need to confirm whether AR-C155858 is a potential substrate of MCT1.

In addition, we also evaluated sodium-dependent uptake of AR-C155858 in 4T1 cells. Interestingly, we found that in the presence of sodium, the uptake of AR-C155858 was significantly higher at pH 6.0 compared with that in the absence of sodium; no significant differences were observed at pH 7.4. The effect of sodium requires further study and suggests that besides the proton-dependent MCT1, a form of sodium-dependent MCT (SLC5A8 or SLC5A12), or another sodium-dependent transporter, may be present in 4T1 cells and contribute to the uptake of AR-C155858.

In summary, the findings presented here demonstrate prolonged inhibition by AR-C155858 and AZD3965, with inhibition being slowly reversible. We also demonstrated that the uptake of AR-C155858 was saturable and can be inhibited by CHC, suggesting that AR-C155858 may be a substrate for MCT1 present in 4T1 cells. Different from AR-C155858, AZD3965 demonstrated passive diffusion and CHC had no significant effect on the cellular uptake of AZD3965, consistent with its good oral bioavailability and higher lipophilicity. Our findings suggest that AR-C155858 is a MCT1 substrate, but other sodium-dependent transporters may also contribute to its uptake in 4T1 cells.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was funded by the National Institute of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant DA023223). X.G. was funded in part by an Allen Barnett Fellowship.

Abbreviations

- MCTs

Monocarboxylate transporters

- CHC

Alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Morris ME, Felmlee MA. Overview of the proton-coupled MCT (SLC16A) family of transporters: characterization, function and role in the transport of the drug of abuse gamma-hydroxybutyric acid. AAPS J. 2008;10(2):311–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halestrap AP, Meredith D. The SLC16 gene family-from monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) to aromatic amino acid transporters and beyond. Pflugers Archiv. 2004;447(5):619–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halestrap AP. The monocarboxylate transporter family–structure and functional characterization. IUBMB Life. 2012;64(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halestrap AP, Wilson MC. The monocarboxylate transporter family–role and regulation. IUBMB Life. 2012;64(2):109–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fishbein WN, Merezhinskaya N, Foellmer JW. Relative distribution of three major lactate transporters in frozen human tissues and their localization in unfixed skeletal muscle. Muscle Nerve. 2002;26(1):101–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juel C, Halestrap AP. Lactate transport in skeletal muscle - role and regulation of the monocarboxylate transporter. J Physiol. 1999;517(Pt 3):633–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broer S, Broer A, Schneider HP, Stegen C, Halestrap AP, Deitmer JW. Characterization of the high-affinity monocarboxylate transporter MCT2 in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Biochem J. 1999;341(Pt 3):529–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dimmer KS, Friedrich B, Lang F, Deitmer JW, Broer S. The low-affinity monocarboxylate transporter MCT4 is adapted to the export of lactate in highly glycolytic cells. Biochem J. 2000;350(Pt 1):219–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manning Fox JE, Meredith D, Halestrap AP. Characterisation of human monocarboxylate transporter 4 substantiates its role in lactic acid efflux from skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2000;529(Pt 2):285–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baltazar F, Pinheiro C, Morais-Santos F, Azevedo-Silva J, Queiros O, Preto A, et al. Monocarboxylate transporters as targets and mediators in cancer therapy response. Histol Histopathol. 2014;29(12):1511–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinheiro C, Longatto-Filho A, Azevedo-Silva J, Casal M, Schmitt FC, Baltazar F. Role of monocarboxylate transporters in human cancers: state of the art. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2012;44(1):127–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Draoui N, Feron O. Lactate shuttles at a glance: from physiological paradigms to anti-cancer treatments. Dis Model Mech. 2011;4(6):727–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kennedy KM, Dewhirst MW. Tumor metabolism of lactate: the influence and therapeutic potential for MCT and CD147 regulation. Future Oncol. 2010;6(1):127–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinheiro C, Reis RM, Ricardo S, Longatto-Filho A, Schmitt F, Baltazar F. Expression of monocarboxylate transporters 1, 2, and 4 in human tumours and their association with CD147 and CD44. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:427694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinheiro C, Sousa B, Albergaria A, Paredes J, Dufloth R, Vieira D, et al. GLUT1 and CAIX expression profiles in breast cancer correlate with adverse prognostic factors and MCT1 overexpression. Histol Histopathol. 2011;26(10):1279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinheiro C, Albergaria A, Paredes J, Sousa B, Dufloth R, Vieira D, et al. Monocarboxylate transporter 1 is up-regulated in basal-like breast carcinoma. Histopathology. 2010;56(7):860–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ullah MS, Davies AJ, Halestrap AP. The plasma membrane lactate transporter MCT4, but not MCT1, is up-regulated by hypoxia through a HIF-1alpha-dependent mechanism. The J Biol Chem 2006;281(14):9030–9037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosafio K, Pellerin L. Oxygen tension controls the expression of the monocarboxylate transporter MCT4 in cultured mouse cortical astrocytes via a hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha-mediated transcriptional regulation. Glia. 2014;62(3):477–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim KS, Lim KJ, Price AC, Orr BA, Eberhart CG, Bar EE. Inhibition of monocarboxylate transporter-4 depletes stem-like glioblastoma cells and inhibits HIF transcriptional response in a lactate-independent manner. Oncogene. 2014;33(35):4433–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamdan L, Arrar Z, Al Muataz Y, Suleiman L, Negrier C, Mulengi JK, et al. Alpha cyano-4-hydroxy-3-methoxycinnamic acid inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e72953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noble RA, Bell N, Blair H, Sikka A, Thomas H, Phillips N, et al. Inhibition of monocarboxyate transporter 1 by AZD3965 as a novel therapeutic approach for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Burkitt lymphoma. Haematologica. 2017;102(7):1247–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polanski R, Hodgkinson CL, Fusi A, Nonaka D, Priest L, Kelly P, et al. Activity of the monocarboxylate transporter 1 inhibitor AZD3965 in small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(4):926–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bola BM, Chadwick AL, Michopoulos F, Blount KG, Telfer BA, Williams KJ, et al. Inhibition of monocarboxylate transporter-1 (MCT1) by AZD3965 enhances radiosensitivity by reducing lactate transport. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13(12):2805–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morais-Santos F, Granja S, Miranda-Goncalves V, Moreira AH, Queiros S, Vilaca JL, et al. Targeting lactate transport suppresses in vivo breast tumour growth. Oncotarget. 2015;6(22):19177–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kong SC, Nohr-Nielsen A, Zeeberg K, Reshkin SJ, Hoffmann EK, Novak I, et al. Monocarboxylate transporters MCT1 and MCT4 regulate migration and invasion of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells. Pancreas. 2016;45(7):1036–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meredith D, Christian HC. The SLC16 monocaboxylate transporter family. Xenobiotica; the fate of foreign compounds in biological systems 2008;38(7–8):1072–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guile SD, Bantick JR, Cheshire DR, Cooper ME, Davis AM, Donald DK, et al. Potent blockers of the monocarboxylate transporter MCT1: novel immunomodulatory compounds. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16(8):2260–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pahlman C, Qi Z, Murray CM, Ferguson D, Bundick RV, Donald DK, et al. Immunosuppressive properties of a series of novel inhibitors of the monocarboxylate transporter MCT-1. Transpl Intern. 2013;26(1):22–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bueno V, Binet I, Steger U, Bundick R, Ferguson D, Murray C, et al. The specific monocarboxylate transporter (MCT1) inhibitor, AR-C117977, a novel immunosuppressant, prolongs allograft survival in the mouse. Transplantation. 2007;84(9):1204–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ovens MJ, Davies AJ, Wilson MC, Murray CM, Halestrap AP. AR-C155858 is a potent inhibitor of monocarboxylate transporters MCT1 and MCT2 that binds to an intracellular site involving transmembrane helices 7-10. Biochem J. 2010;425(3):523–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ovens MJ, Manoharan C, Wilson MC, Murray CM, Halestrap AP. The inhibition of monocarboxylate transporter 2 (MCT2) by AR-C155858 is modulated by the associated ancillary protein. Biochem J. 2010;431(2):217–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Izumi H, Takahashi M, Uramoto H, Nakayama Y, Oyama T, Wang KY, et al. Monocarboxylate transporters 1 and 4 are involved in the invasion activity of human lung cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2011;102(5):1007–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang H, Yang C, Doherty JR, Roush WR, Cleveland JL, Bannister TD. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of pteridine dione and trione monocarboxylate transporter 1 inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2014;57(17):7317–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vijay N, Morse BL, Morris ME. A novel Monocarboxylate transporter inhibitor as a potential treatment strategy for gamma-Hydroxybutyric acid overdose. Pharm Res. 2015;32(6):1894–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halestrap AP, Price NT. The proton-linked monocarboxylate transporter (MCT) family: structure, function and regulation. Biochem J. 1999;343(Pt 2):281–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guan X, Bryniarski MA, Morris ME. In vitro and in vivo efficacy of the Monocarboxylate transporter 1 inhibitor AR-C155858 in the murine 4T1 breast Cancer tumor model. AAPS J. 2018;21(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nancolas B, Sessions RB, Halestrap AP. Identification of key binding site residues of MCT1 for AR-C155858 reveals the molecular basis of its isoform selectivity. Biochem J. 2015;466(1):177–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guan X, Ruszaj D, Morris ME. Development and validation of a liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry assay for AZD3965 in mouse plasma and tumor tissue: application to pharmacokinetic and breast tumor xenograft studies. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2018;155:270–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harker WG, Sikic BI. Multidrug (pleiotropic) resistance in doxorubicin-selected variants of the human sarcoma cell line MES-SA. Cancer Res. 1985;45(9):4091–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curtis NJ, Mooney L, Hopcroft L, Michopoulos F, Whalley N, Zhong H, et al. Pre-clinical pharmacology of AZD3965, a selective inhibitor of MCT1: DLBCL, NHL and Burkitt's lymphoma anti-tumor activity. Oncotarget. 2017;8(41):69219–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sarah ER, Halford PJ, Steve W, Hirschberg S, Katugampola S, Veal G, et al. A first-in-human first-in-class (FIC) trial of the monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) inhibitor AZD3965 in patients with advanced solid tumours. American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; Monday, June 5, 20172017. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dienel GA. Brain lactate metabolism: the discoveries and the controversies. J Cerebral Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32(7):1107–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colen CB, Seraji-Bozorgzad N, Marples B, Galloway MP, Sloan AE, Mathupala SP. Metabolic remodeling of malignant gliomas for enhanced sensitization during radiotherapy: an in vitro study. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(6):1313–23 discussion 23-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colen CB, Shen Y, Ghoddoussi F, Yu P, Francis TB, Koch BJ, et al. Metabolic targeting of lactate efflux by malignant glioma inhibits invasiveness and induces necrosis: an in vivo study. Neoplasia. 2011;13(7):620–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sonveaux P, Vegran F, Schroeder T, Wergin MC, Verrax J, Rabbani ZN, et al. Targeting lactate-fueled respiration selectively kills hypoxic tumor cells in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(12):3930–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]