Abstract

We conducted a systematic review of safer conception strategies (SCS) for HIV-affected couples in sub-Saharan Africa to inform evidence-based safer conception interventions. Following PRISMA guidelines, we searched fifteen electronic data-bases using the following inclusion criteria: SCS research in HIV-affected couples; published after 2007; in sub-Saharan Africa; primary research; peer-reviewed; and addressed a primary topic of interest (SCS availability, feasibility, and acceptability, and/or education and promotion). Researchers independently reviewed each study for eligibility using a standardized tool. We categorize studies by their topic area. We identified 41 studies (26 qualitative and 15 quantitative) that met inclusion criteria. Reviewed SCSs included: antiretroviral therapy (ART), pre-exposure prophylaxis, timed unprotected intercourse, manual/self-insemination, sperm washing, and voluntary male medical circumcision (VMMC). SCS were largely unavailable outside of research settings, except for general availability (i.e., not specifically for safer conception) of ART and VMMC. SCS acceptability was impacted by low client and provider knowledge about safer conception services, stigma around HIV-affected couples wanting children, and difficulty with HIV disclosure in HIV-affected couples. Couples expressed desire to learn more about SCS; however, provider training, patient education, SCS promotions, and integration of reproductive health and HIV services remain limited. Studies of provider training and couple-based education showed improvements in communication around fertility intentions and SCS knowledge. SCS are not yet widely available to HIV-affected African couples. Successful implementation of SCS requires that providers receive training on effective SCS and provide couple-based safer conception counseling to improve disclosure and communication around fertility intentions and reproductive health.

Keywords: HIV, Safer conception, Africa, Fertility, Pregnant, Serodiscordant, Couples

Introduction

Since the introduction of antiretroviral therapy (ART), pregnancy rates and the desire to conceive have increased among men and women living with HIV due to longer life expectancy, improved quality of life, and dramatic reductions in mother to child HIV transmission [1–4]. However, attempts to conceive among HIV affected couples may increase sexual transmission of HIV [2–4], and HIV acquisition during perinatal periods increases the risk of mother-to-child transmission [5, 6]. Further, pregnancy itself is a time of increased HIV risk. Mechanisms of increased susceptibility of HIV acquisition during pregnancy and breastfeeding may be due to hormonal changes that alter genital mucosal surfaces or distribution of target cells at these surfaces, and behavioral factors such as condomless sex and multiple partners also increase HIV risk in pregnancy [6]. Addressing the various needs of couples living with HIV or at risk of acquiring HIV who desire children is a complicated task that requires improved quality, utilization, and access to safer conception counseling and methods. Given the increased risk of HIV acquisition and transmission in pregnancy, certain safer conception methods could be used through pregnancy and postpartum to prevent transmission during those periods.

Safer conception interventions that minimize the risk of horizontal and vertical HIV transmission include timed condomless intercourse (during ovulation) [7], intravaginal or intrauterine insemination for women which may include sperm washing if the male partner is HIV-infected [8, 9], ART for HIV-infected partners [10–12], pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV-uninfected partners [13], and voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV-uninfected men (VMMC) [14]. While some of these strategies are generally available (including ART and VMMC), most interventions and counseling focused on safer conception may be unavailable in sub-Saharan Africa, where the majority of HIV affected couples reside [15]. Women living in sub-Saharan Africa comprise 58% of the total number of people living with HIV (PLWH) globally [1], and it is estimated that 75% of HIV-affected partnerships are serodiscordant in countries with low HIV prevalence and 37% are serodiscordant in countries with high HIV prevalence [16]. Sub-Saharan Africa is also the region with the highest rates of conception-associated HIV incidence and mother-to-child HIV transmission in the world [5, 17]. One study examining seven sub-Saharan countries found high ‘early’ pregnancy-associated HIV incidence (and thus a combination of pregnancy- and conception-associated risk) of 10.59/100 PY (person-years) among women and 4.41/100 PY among men [6].

Given high conception-associated HIV risk, understanding the current status of safer conception methods is critical. This is one of the first systematic reviews of safer conception strategy (SCS) availability, feasibility, acceptability and education/promotion for HIV-affected heterosexual couples (either concordant HIV positive or HIV discordant) in sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of recent literature on SCS in sub-Saharan Africa following PRISMA guidelines [18]. We searched fifteen electronic scientific literature databases to identify relevant research reports using the following eligibility criteria: (1) SCS research in heterosexual HIV affected couples, (2) in sub-Saharan Africa, (3) reporting primary research, (4) peer-reviewed, (5) published after 2007, and (6) addressed a main research topic of interest. The research topics of interest included: (1) availability of safer conception strategies in sub-Saharan African countries; (2) feasibility and/or acceptability of safer conception strategies for HIV-affected heterosexual couples; and (3) promotional and/or educational strategies used to increase uptake and/or provision of safer conception strategies.

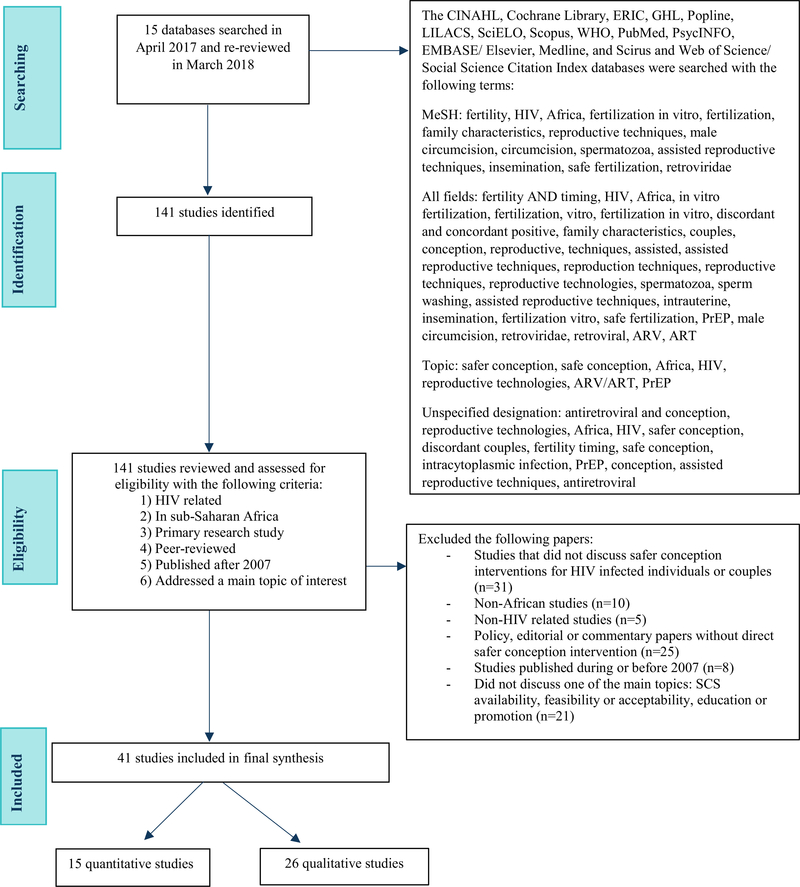

Search terms included: safe(r) conception, fertility, fertility timing, HIV, Africa, fertilization in vitro, fertilization, reproductive techniques, reproductive technologies, male circumcision, circumcision, spermatozoa, assisted reproductive techniques, insemination, safe fertilization, retroviridae, ART, PrEP, discordant or concordant HIV-infected couples, intrauterine, sperm washing, and family characteristics (Fig. 1). Two independent research assistants performed standardized data extraction on each study and evaluated if the study addressed one of the research topics of interest. If the study did not address one of the research topics, it was excluded. This eligibility evaluation was conducted by two independent researchers, and a third independent reviewer decided on the final inclusion or exclusion in the event that two independent reviewers disagreed on eligibility (as occurred in 38% of reviews).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of databases searched. ARV antiretroviral, ART antiretroviral treatment, PrEP pre-exposure prophylaxis, SCS safe conception strategy

Next, data from the eligible studies were abstracted using a standardized data abstraction tool. Data abstracted included author/year of publication; study design (randomized control trial [RCT], cross-sectional, cohort, case–control, or qualitative); study population; definition of the SCSs considered and whether they were widely available or under investigation; definition of key exposures or interventions tested as applicable; definition of the outcome of interest; analytic methods used; key results including SCS availability, feasibility and acceptability, and educational and promotional efforts.

Finally, we conducted an analysis using consensus among themes identified by three research assistants within the topics of interest (availability, feasibility and acceptability, and education/promotion of SCS). Any noted barriers or facilitators to safer conception implementation were also documented. These themes are classified by whether they were related to the client- or provider-side.

Results

Our initial search identified 141 articles for review. One hundred articles were excluded for the following reasons: studies did not address SCS in HIV affected couples; were not primary research (e.g. reviews or commentary papers); did not take place in sub-Saharan Africa; were not related to HIV; and/or did not address one of the topics of interest. We identified 41 studies that met inclusion criteria including: 26 qualitative studies, 3 randomized control trials, 8 cohorts, and 4 cross-sectional studies (Fig. 1).

Studies were from six African countries (Kenya, Uganda, Malawi, Nigeria, South Africa and Tanzania) (Table 1). Of the 15 quantitative studies included, we identified twenty-one different quantitative outcomes. Because of the range of SCS outcomes evaluated across studies, a meta-analysis of the quantitative studies was not possible.

Table 1.

List of publications by author, year, population and topic included in the systematic review of safer conception strategies in sub-Saharan Africa (n = 41)

| Author, year | Country | Study Design and data collection method | Population | Primary research question | Study findings and outcomes | Research Topics Addressed (SCS availability, feasibility or acceptability, education/ promotion) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beyeza-Kashesya, 2018 [46] | Uganda | Quantitative survey | Ugandan HIV clients who intend to conceive (n = 400) | What is the process of initiation of the discussion and correlates of client- provider communication about childbearing and safer conception among HIV clients who desire to have children? | Almost all wanted patients wanted to discuss childbearing with their providers (98%) but only 44% reported such discussions of which 28% were initiated by the provider. Most discussed HIV transmission risk to the partner, transmission risk to the child and how to prevent MTCT. Only 8% of providers discussed safer conception methods. Those who discussed fertility intentions were more likely to have been diagnosed for longer period, and internalized childbearing stigma was associated with lower odds of communication with a health care provider. | Acceptability, feasibility, education/promotion |

| Breitnauer 2015 [57] | Kenya | Qualitative (FG and IDI) | Citizens of Kisumu (n = 59) | What is the characterization of community perception of safe conception strategies for HIV-discordant couples in Kenya? | The Kisumu community reported mixed attitudes regarding serodiscordant couples having children. | Feasibility, acceptability |

| Crankshaw 2014 [61] | South Africa | Qualitative (FG and IDI) | Doctors, nurses, lay counsellors in Durban (n = 25) | To evaluate healthcare provider viewpoints and experiences on safer conception care in an urban

setting in Durban, South Africa to inform scs. |

Challenges faced by providers when clients seek SCS included issues of status disclosure when one partner was unaware of other partner’s HIVpositive status and male partners generally being uninvolved in SCS consultations with their partners. | Feasibility, acceptability, promotion |

| Ddumba-Nyanzi 2016 [51] | Uganda | Qualitative (IDI) | HIV infected women receiving ART (n = 48) | This study aimed to explore barriers to communication between providers and women living with HIV regarding childbearing. | From the HIV-positive women’s point of view 4 themes emerged in IDIs describing barriers to communication: (1) provider indifference or opposition to childbearing post HIV diagnosis, (2) anticipation of negative response from provider, (3) provider’s emphasis on ‘scientific’ facts, (4) ‘accidental pregnancy. | Availability, feasibility |

| Ezeanochie 2009 [34] | Nigeria | Cross sectional (survey) | HIV- positive women married to a seronegative man (n = 55) | This study aimed to determine reproductive preferences, condom use, and concerns about infecting a partner or child. | Younger women were significantly more likely to choose natural conception than assisted

reproductive technologies (p = 0.02). Women who preferred natural conception reported more condom use than those who preferred assisted reproductive technologies (57% vs. 20%, p = 0.049). |

Feasibility, acceptability |

| Finocchario-Kessler 2014 [49] | Uganda | Qualitative (Semi-structured interviews) | Healthcare providers and HIV-positive clients (n = 81) | What is the knowledge, acceptability and feasibility of SCS among health care providers and HIV-positive clients? | Clients and providers had heard of safer conception especially TUI but few understood how to use methods. All providers expressed desire to include SCS in their practice. All desired more training and counselling protocols to address barriers and to engage with men in SC counselling. | Availability, feasibility and |

| Fourie 2015 [37] | South Africa | Cohort (surveys) | HIV-positive men (n = 95) | Is seminal decontamination using Proinsert effective for removing the HIV-1 virus from semen samples? | Semen decontamination (sperm washing) was effective in removing HIV-q RNA and DNA from 98% of samples from HIV- positive men. | Feasibility |

| Goggin 2015 [35] | Uganda | Cohort (surveys) | Healthcare providers (n = 57) | What are providers’ attitudes about childbearing among PLWH and providers’

engagement in discussions about childbearing, as well as their knowledge, interest, self-efficacy, and intentions to

provide scs? |

Providers with greater self-efficacy to provide safer conception counselling reported had discussed childbearing with more patients in the last 30 days (p < 0.001), had greater SCS awareness (p<0.001), had perceived fewer barriers to providing SCS (p<0.001), had greater intentions to counsel on TUI (p< 0.001), but had lower intentions to counsel on manual insemination (p = 0.02). | Availability, feasibility, and education/promotion |

| Hancuch 2018 [32] | Uganda and Kenya | Cohort (surveys) | High-risk heterosexual discordant couples in PrEP and ART study | What proportion of women in serodiscordant couples reported use of safer conception? What type of methods were used? | In the cohort of serodiscordant couples, 66% of women in the study were HIV-infected and 73% reported desiring a child in the future. At the first annual visit of the cohort, 59%< of women mentioned the use of PrEP, 58% ART, 50% timed condomless sex, 23%’ self-insemination, and< 10%’ mentioned male circumcision, STI treatment, artificial insemination, and sperm washing as safer conception strategies. Of those who wanted to get pregnant, 37%’ reported using PrEP, 14% ART, and 30%’ timed condomless sex. Use of safer conception methods was higher in women who discussed their fertility desires with their partners. | Feasibility and education/ promotion |

| Kawale 2014 [39] | Malawi | Cross sectional (surveys and IDI) | HIV-positive persons 18–40 years of age (n = 202; 75 men and 127 women) | What are the factors associated with desire for children among HIV-infected women and men? | Being in a relationship (p<0.05) and duration of HIV > 2-years increased fertility

intentions (p<0.05). However, being between the ages of 36–40 (p = 0.009) and having a living child

decreased the odds of wanting a child (p = 0.03). In IDIs, 70% of women said that men make the decision about having children, while the remaining 30% reported that it was a collaborative decision. No women reported that they make the decision independently. 86% of women reported no discussion or having a discouraging discussion with providers about having children. |

Availability, acceptability |

| Kawale 2015 [24] | Malawi | Qualitative (FG) | Health care providers (n = 25) | What are health care provider attitudes about childbearing and knowledge of safer conception at two HIV clinics in Malawi? | Providers in this setting lack knowledge to appropriately counsel clients and there is a need for provider training. | Availability, feasibility, and education |

| Khidir 2017 [43] | South Africa | Qualitative (FG) | HIV-positive men in South Africa (n= 12) | What is the process of creating and evaluating acceptability of a safer conception intervention for men living with HIV who want to have children with partners at risk for acquiring HIV in South Africa? | Men were willing to access SCS at a healthcare facility. Engaging female partners was acceptable

if they were aware of the male’s HIVstatus. Safer conception counselling is rarely provided by public sector healthcare workers due to low knowledge about serodiscordance. |

Availability, acceptability, feasibility, education/ promotion |

| Manteli 2017 [55] | South Africa | Phase II futility RCT (survey) | Newly diagnosed HIV-positive persons (n = 214, of whom 104 were randomized to intervention) | Can a new enhanced multi-level educational counselling intervention increase? Adherence to safer conception and contraceptive use among those seeking conception in newly diagnosed HIVpositive persons in 4 public health clinics? |

In a futility analysis, 83% of participants in the enhanced intervention arm followed safer

conception guidelines vs. 72% in the standard ofcare arm (p = 0.573) indicating that the intervention may be superior to

standard of care, but calling for future, larger studies to confirm possible superiority. In newly diagnosed patients, HIV providers who delivered the intervention improved the capacity of HIV-affected couples make informed decisions about risks, benefits, andoptions associated with safer sex, fertility, and parenting options. |

Education/promotion, availability Author’s personal copy AIDS and Behavior 1 |

| Matthews 2012 [40] | South Africa | Qualitative (IDI) | HIV-positive individuals with HIV-negative partner (n = 50, 30 women and 20 men) | This study investigated patient reported experiences with SC counselling from health care workers. | HIV infected men and women in serodiscord- ant relationships were receptive to SCS but did not

ask providers, nor receive information on specific SC methods. HIV nondisclosure and unplanned pregnancy were important

intervening factors. Men and women expressed desire to learn more about SCS. |

Acceptability, education |

| Matthews 2013 [59] | South Africa | Qualitative (IDI) | HIV-positive individuals attending HIV services (n = 50, 30 women, 20 men) | The research focus was to explore periconcep- tion risk, understanding and practices in order to design effective risk- reduction interventions. | Individuals expressed desire for children, but most pregnancies were unplanned. Male desire to procreate and misunderstanding of serodiscordance led to high levels of risky sexual behavior. |

Feasibility, education |

| Matthews 2014a [30] | Kenya and Uganda | Phase III RCT participants(survey) | HIV-uninfected women with HIV-infected partners (n = 1785) | This study sought to evaluate predictors of pregnancy and adherence to study medication among HIV uninfected women with HIV infected partners. | Pregnancy incidence was 10.2 per 100 person- years. Women experiencing pregnancy took 97% of prescribed medication with at least 80%< pill adherence in 98%< of recorded months (p = 0.98). Tenofovir detected in 71% of visits where pregnancy was discovered, similar to non-pregnant women, p>0.1) indicating that PrEP may be acceptable and feasible as a SCS in HIV- women with HIV-positive partners. |

Acceptability, feasibility |

| Matthews 2014b [52] | South Africa | Qualitative (IDI and FG) | Healthcare providers (counsellors, nurses and doctors) (n = 42) | This study explored provider practices of assessing fertility intentions among HIV-infected men and women, attitudes toward PLWH having children, and knowledge and provision of safer conception advice. | Only 5 providers mentioned ART, none mentioned PrEP, and 27 did not mention any

SCS. Providers sometimes assessed fertility intentions but did not offer specific advice and gave the impression that they do not think HIV-posi- tive individuals should have children. |

Acceptability, feasibility, education |

| Matthews 2015a [41] | South Africa | Qualitative (IDI) | HIV-positive men and women (n = 35, 20 females and 15 males) | To explore barriers and promoters to patient- provider communication around fertility-desires and intentions. | Few participants discussed fertility goals with providers. Discussions around pregnancy focused

on maternal and child health and not on sexual HIV transmission. No participants received safer conception

counselling. Barriers included condom-use promotion, implying that SC is not an option and clients’ fear of judgement from providers. An intervention should be implemented to encourage providers to ask about fertility intentions and offer appropriate advice. |

Availability, acceptability, education/promotion |

| Matthews 2015b [36] | South Africa | Cross sectional (survey) | HIV infected men and women (n = 209 women and 82 men) with HIV negative partners | This study assessed risk behavior in recently pregnant HIV-positive men and women with HIV- partners order to inform safer conception program. | Knowledge of SCSs was low in recently pregnant HIV- positive couples. Seven women (3%) and two men (2%) reported limiting sex without condoms during ovulation. No reports of sperm washing or manual insemination were recorded. However, other SCS including status disclosure, ART use and condom use were not associated with desired pregnancy. 41% of women and 88%< of men were aware of ART as a SCS. | Availability, feasibility, education |

| Matthews 2016a [42] | Uganda | Qualitative (IDI) | Healthcare providers (n = 38) | This study explored healthcare provider perspectives and practices regarding safer conception counseling for HIV- affected clients. | Providers rarely initiate conversations about fertility intentions with men, as they viewed men as playing passive roles in clinic-based family planning programs. | Availability, education/ promotion |

| Matthews 2016b [58] | Uganda | Cohort | HIV-infected Ugandan women (n= 111) | This study compares HIV suppression, medication adherence across peri- conception, pregnancy, and postpartum periods among women on ART. | This study found that 89% of nonpregnant participants were virally suppressed compared to 97% of

periconcep- tion, 93% of pregnancy, and of postpartum participants. Periconcep- tion participants had greater odds of

achieving viral suppression (aOR = 2.15) compared to nonpregnant women. ART adherence was high at: 90, 93, 92 and 88%

during nonpregnant periconception, pregnant, and postpartum periods, respectively. However, adherence was lower during periconception (aOR = 0.68) compared to pregnancy and post-pregnancy. |

Feasibility |

| Matthews 2017 [64] | Uganda | Qualitative (IDI) | 40 individuals from 20 couples who were serodiscordant or had a partner of unknown serostatus and wanted a child within two years | This study explored the acceptability and feasibility of safer conception methods among HIV-affected couples in Uganda using a narrative approach with tailored images to assess acceptability of five safer conception strategies: ART for the infected partner, PrEP for the uninfected partner, condomless sex timed to peak fertility, manual insemination, and male circumcision. | Safer conception method knowledge was largely limited to use of condoms which limited the ability to explore other methods. Key partnership communication challenges emerged including: (1) serostatus disclosure, (2) divergent childbearing intentions, (3) disparate understanding of HIV risk, (4) discord in perceptions of partnership commitment. Miscommunica- tion was common with only 2 of 20 partnerships in agreement with all 4 themes. | Feasibility |

| Mindry 2015 [53] | South Africa | Qualitative (IDI and FG) | PLWH (n = 43) and healthcare providers (n = 20) | This study investigated the childbearing intentions and needs of PLWH, the attitudes and experiences of health-care providers serving the reproductive needs of PLWH, and client and provider views and knowledge of safer conception. | Factors within the relationship (partner desire for children, person’s own desire for

children) were stronger motivations for desiring a child relative to having or not having an existing

child. Providers were concerned about client health, viral suppression, and wellbeing of the future child. |

Availability, feasibility, education |

| Mindry 2016 [50] | South Africa | Qualitative (FG and IDI) | In-depth interview with 43 PLHIV, 2 focus group discussions and 12 indepths interviews with providers | This study examined client and provider perspectives on safer conception methods. | Providers and clients had limited knowledge about scs. There was a lack of adequate counselling for male clients and concern about biological parentage and HIV transmission of SCS. Providers may feel uncomfortable discussing sexual matters and desired more training. |

Availability, feasibility, education/promotion |

| Mmeje 2014 [15] | Sub-Saharan Africa | Review | HIV-affected couples | How can the reproductive options for HIV-affected couples in sub-Saharan Africa be improved? | Women expressed a desire to access provider assistance in family planning. | Acceptability |

| Mmeje 2015 [27] | Kenya | Qualitative (FG) | Health care providers and serodiscordant couples (n = 33) | What are the perspectives on TVI among HIV- serodiscordant couples and their healthcare providers in Kenya and how would they approach TVI? | Fertility intention and SCS interest was high in clients, but less than half had discussed with

their partners. Woman were more likely to discuss with a healthcare provider. Providers were optimistic about TVI but were divided on who should administer the procedure. |

Acceptability, feasibility |

| Mmeje 2016 [54] | Kenya | Qualitative (FG and IDI) | Health care providers and HIV-affected individu- als/couples (n= 106) | This study assessed HIV- related stigma, fears, and recommendation for delivery of safer

conception counselling in developing a Safer Conception. Counselling Toolkit that can be used to train health care providers and provide counselling to HIV-affected individuals and couples. |

HIV-positive individuals experienced stigma from their communities, and HIV-positive clients feared vertical transmission. Providers reported that the toolkit may help remove stigma around HIV-affected couples bearing children, and help them support those couples in realizing their fertility desires. | Acceptability |

| Moodley 2014 [47] | South Africa | Qualitative (IDI) | Health care providers (n = 28) | What are health care workers’ perspectives on pregnancy and parenting in HIV-positive individuals in South Africa? | Providers felt conflicted between supporting reproductive rights of PLWH and concern about

transmission. Provider’s limited SCS knowledge was a barrier to providing counselling. |

Availability, education |

| Ngure 2014 [21] | Kenya | Qualitative (FG and IDI) | Individuals in serodiscord- ant couples (n = 56) | Study sought to understand fertility intentions and HIV risk considerations among Kenyan serodiscordant couples who were pregnant during prospective study. | Almost all couples had intended their current pregnancy despite the risks. | Feasibility |

| Ngure 2017 [48] | Kenya | Qualitative (FG and IDI) | HC providers and serodis- cordant couples (n = 87) | What are the perspectives and experiences of Kenyan health providers and HIV serodiscordant couples with respect to safer conception? | Providers lacked specific knowledge about SCS. Timed condomless sex with ART and/or PrEP were preferred methods of safer conception. |

Feasibility, acceptability and education |

| Pintye 2015 [63] | Kenya | Qualitative (IDI) | Serodiscordant couples (n = 36) | What is fertility decisionmaking like among Kenya HIV-serodiscord- ant couples who recently conceived? | The timing preference for having children became more urgent after becoming HIV-positive. | Feasibility |

| Saleem 2016 [45] | Tanzania | Qualitative (IDI) | Healthcare providers and HIV-affected men and women (n = 90) | What are the ecological barriers to the adoption of safer conception strategies by HIV-affected couples? | Lack of provider training in SCS and preconception counselling for PLWH, and health workforce shortages that limit the quality of counselling, poor linkages to HIV care, and lack of integration of HIV and reproductive health services. | Feasibility, acceptability |

| Schwartz 2014 [11] | South Africa | Qualitative (n = 51) and 128 clinical cohort participants | HIV positive men and women (82 women and 46 men, representing 82 partnerships) | How does one best develop and implement a safer conception service in a resource-limited setting? | The majority of HIVpositive men and women were on ART (71% and 86%, respectively) but only 47% of those on ART were virally suppressed. TUI,selfinsemination and ART were common SCS choices for participants; and 44% elected to take PrEP. | Acceptability and feasibility |

| Schwartz 2016 [12] | South Africa | Qualitative (IDI) | Individuals in serodiscord- ant relationships (n = 42) | What are the acceptability and preferences for safer conception/HIV prevention strategies for patients at the Witkop- pen Centre? | Clients had more knowledge about preventing vertical transmission than horizontal

transmission. HIV-negative men and HIV-positive women had favourable attitudes towards self-insemination, though they were concerned about paternity and safety. Self-insemination was preferred over PrEP by HIV-negative men. ART was preferred by couples with HIV-negative female partners. |

Feasibility, acceptability |

| Schwartz 2017 [19] | South Africa | Cross sectional (survey) | HIV affected individuals in serodiscordant and concordant and unknown status relationships (n = 440) | Are clinic clients utilizing and continuing safer conception methods? | 90% of ART-naïve individuals initiated ART, and uptake of ART was similar in HIV-positive

men and women. Overall uptake of selfinsemination was 39% and was highest in discordant couples where the woman is positive. Overall uptake of TUI was 48% and was highest in concordant couples. PrEP uptake among HIVnegative clients was 23%, but higher among women than men in discordant couples (44% vs 7%, p<0.001). 53% of uncircumcised men expressed interest in getting circumcised, but only 19% of men underwent circumcision. |

Feasibility, acceptability |

| Steiner 2016 [20] | South Africa | Cohort (survey) | Women living with HIV (n = 831) | This study examined differences in the number of condomless sex acts by fertility intentions in women living with HIV and compared receipt of safer conception messages in HIV-infected women between those with positive fertility intentions (regardless of outcome) and those with negative fertility intentions. | WLWH trying to conceive were over 3 times more likely to have condomless sex compared with those not trying to conceive (adjusted incidence rate ratio: 3.17, 95% confidence interval: 1.95 to 5.16). Receipt of specific safer conception messages was low, although women with positive fertility intentions were more likely to have received any fertility-related advice compared with those with unplanned pregnancies (76.3% vs. 49.1%, P, 0.001). Among WLWH trying to conceive (n= 111), use of timed unprotected intercourse was infrequent (17.1%) and lower in serodis- cordant vs. concordant partnerships (8.5% vs. 26.9%, P = 0.010). | Availability, acceptability |

| Taylor 2013 [31] | South Africa | Qualitative (IDI) | HIV-positive men (n = 27) | What are the notions of fatherhood and their linkages to fertility desires/intentions among Xhosa-speaking 20–53-year-old men living with HIV in Cape Town? | Gender-specific beliefs about having children and fatherhood were linked to

masculinity. Favourable attitudes towards provider insemination, self-insemination and sperm washing were found; men’s main concerns were about HIV transmission and compromising biological paternity. HIV-positive men expressed a biological imperative to become a father. SCS knowledge was low. |

Acceptability |

| van Zyl 2015 [22] | South Africa | Qualitative (FG and IDI) | HIV counsellors (n= 12), HIV-positive men (n= 10), HIV-positive pregnant (n = 10) and

non-pregnant women (n=11) |

What are the reproductive desires of men and women living with HIV? What is the implication of those desires on HIV prevention? | Providers need training and lacked information on SCS. Providers in the HIV clinic vs. antenatal clinic had different attitudes toward SCS. Counselors in antenatal care who worked with pregnant HIV-infected women, strongly advised them not to have children and to use condoms at all times. For patients, parenthood was an important factor for all participants in establishing their gender roles, and building a family, despite the risk of HIV transmission and possible stigma from the community. The study found the following key themes were factors associated with desiring (or not) children: continuation of family, fulfilment of gender identity within the family and community, gender inequality in procreation, community level stigma of HIV, and procreation rules for PLHIV. |

Availability, feasibility |

| Wagner 2015 [60] | Uganda | Cohort (survey and IDI) | HIV-positive clients (n = 400) | This study examined the utilization of SCS and the correlates of such use from among demographic, relationship, and health management characteristics, multidimensional childbearing stigma and knowledge and attitudes toward SCS in Ugandan HIV clients in heterosexual relationships with fertility intentions. | Education and promotion of SCS among HIV-positive patients evaluated sex behaviours,

self-efficacy and willingness to use SCS after intervention. Few reported using TUI, none used self-insemination or sperm washing. Generally high confidence in SCS uptake reported. |

Feasibility, education/pro- motion |

| Wagner 2016 [25] | Uganda | Cohort (survey) | HIV-positive clients (n = 400) | This study examined awareness of and attitudes towards SCS and the correlates of these constructs among demographic, relationship, and health management characteristics, as well as multidimensional aspects of stigma towards childbearing by HIV-affected couples. | Education and promotion of SCS among HIVpositive clients increased confidence on use of

SCS. The relationship, partner related variables, and provider communication regarding fertility intentions were associated with SCS awareness and attitude. |

Acceptability, education/ promotion |

| Wagner 2017 [33] | Uganda | Cohort (survey) | HIV-positive clients (n = 400) | What are the prevalence and correlates of safer conception methods use in HIV-affected couples in Uganda? | 35% of patients reported any use of TUI in the study. Use of other SCM was rare. Predictors of any TUI use included: greater awareness of safer conception methods, belief that trying to have a child impedes condom use, lower social support, greater perceived provider stigma of childbearing, greater control over sexual decision making in the relationship and inconsistent condom | Acceptability, feasibility, education/promotion |

| Were 2014 [28] | Kenya & Uganda | RCT study participants (survey) | Serodiscordant couples (n = 2962) | This study assessed the impact of TDF and FTC/ TDF use on male fertility as determined by pregnancy rates among partners of men receiving PrEP compared with partners of men receiving placebo enrolled in an RCT. | Overall incidence of pregnancy was 12.9 per 100 person years and did not differ by PrEP vs

placebo. Live births, pregnancy loss, gestational age at birth or loss was statistically similar in all groups. |

Feasibility |

| West 2016 [51] | South Africa | Qualitative (FG and IDI) | Healthcare providers, HIV-positive men and women wanting children (n = 51) | This study evaluated gaps in implementation of the South African safer conception and fertility guidelines through assessing health care providers knowledge, experiences, competencies, facilitators, and barriers to provision of safer conception services. Patient experiences were are incorporated to further illuminate health care providers implementation of these guidelines. | Providers supported PLWH fertility intentions and had some SCS knowledge but did not initiate

conversations, possibly due to beliefs that the couple “is not ready”. Clients anticipated negative response from providers if they discussed wanting to get pregnant. |

Availability, feasibility, education/promotion |

RCT Randomized control trial, IDI In-depth interview, FG Focus group, PrEP pre-exposure prophylaxis, SCS safer conception strategy, PLWH people living with HIV, TUI timed unprotected intercourse, ARV antiretrovirals, ART antiretroviral treatment, VMMC voluntary medical male circumcision

Topic 1: Safer Conception Strategies in Sub-Saharan African Countries that were Available and/or Under Investigation (Tables 1, 2)

Table 2.

Key themes related to safer conception strategy topics of interest (n= 41 studies)

| Patients | Providers | |

|---|---|---|

| Topic 1—availability of SCS | Unaware about availability of safer conception services [20, 31, 33, 36, 39, 55], Integration of services for sexual and reproductive health to increase SCS availability and uptake [43, 45], Few discussed fertility goals with providers. Discussions around pregnancy focused on maternal and child health and not on sexual HIV transmission. Few received safer conception counselling [30, 39, 41, 46]. |

Providers training and self-efficacy increases SCS availability [35] and providers desired additional training on SCS [22, 45, 50], Lack of provider training and guidelines in safer conception strategies and preconception counselling for PLHIV [51] and health workforce shortages that limit the quality of counselling, poor linkages to HIV care, and lack of integration of HIV and reproductive health services [24, 45, 48–51], Tailored guidelines and training are required for providers to implement SCS [42, 51, 55], Providers were concerned about future children’s health [47, 53]. |

| Topic 2—feasibility or acceptability of SCS delivery | Acceptability impacted by knowledge on SCS services [20,

27, 28, 33, 34, 36, 55], Difficulty with disclosure of HIV status [54, 61, 64], Serodiscordant clients fear negative reaction from providers [27, 41,46,51], Fears about mother to child transmission [63], Male partners generally uninvolved in safer conception conversations [27, 39, 61], but men desired knowledge about SCS [41, 43], Power imbalances within couples [27, 31, 39, 59], Different preferences for certain SCSs depending on if the female or male partner was HIV-infected (e.g. ART preferred when male was positive, self-insemination when female was positive) [12, 19, 63], Mixed attitudes by community regarding SCS for serodiscordant couples; [57] Stigma from the community is a barrier to discussion of having children and SCS uptake among HIV affected couples [22, 54], Women, men, and couples expressed willingness to access safer conception intervention and desire counseling [11, 12, 15, 19, 21, 22, 28, 30, 31, 40, 41, 50, 55, 58–60], Assisted reproduction strategies generated negative reactions from couples. Education and explanation of these services may improve uptake [57]. |

Providers face challenges when discussing SCS with couples due to confidentiality issues and one

partner being more involved than the other [61] and acceptability of SCS may be

higher if women know their partner’s serostatus [43, 64] Health care providers indifferent or opposed to PLWH having children [22, 39, 47, 51–53], Providers do not recommend child-bearing for PLWH or serodiscordant couples due to secondary transmission concerns [22, 51, 53], Providers self-efficacy and communication with patients assists feasibility and acceptability [35], Providers uncomfortable discussing sex and SCS limiting SCS discussion [20, 50], Provider education about SCS was needed and feasible [24, 45, 52, 54], Effective sperm washing technologies are available and effective at preventing male to female HIV transmission [37]. |

| Topic 3—education and promotion of SCS | Clients’ fear of judgment is a barrier to SCS counseling and education [41, 51, 54]/ Individuals may not be aware of their partner’s HIV status which is a barrier to reaching discordant couples with counseling messages on SCS [43, 61, 64] Education and promotion awareness has impact on SCS uptake and acceptance [25, 33, 36, 40, 55, 59, 60]. |

Providers rarely initiated discussion of fertility intentions and reproductive goals with

clients during visits [24, 41

42, 46, 50, 58, 61], When assessed,

usually only the woman’s reproductive goals were discussed not the man’s or couples [42, 61], Sharing success stories of safer conception is effective at increasing SCS uptake and acceptance [22, 57], Provider’s confidence to provide counseling and education increased by promotion [35], Providers lack understanding of SCS [47, 48, 50, 52, 53]. |

The studies in the review identified SCSs available or under investigation in sub-Saharan Africa. ART uptake in HIV-infected partners to achieve viral suppression [11–13, 19–22] and counseling around timed unprotected intercourse (TUI) [23–28] were generally available. Voluntary male medical circumcision for HIV-uninfected men (VMMC) was also discussed as a generally available method of safer conception [11, 14].

Advanced, or more expensive strategies such as PrEP [11, 12, 19, 22, 28–33] and assisted reproductive techniques such as manual/self-insemination [11–13, 19, 29, 34–37] and sperm washing [8, 9] were under investigation as effective SCS methods, but were unavailable at government public healthcare facilities and generally only available in small pilot studies.

Factors affecting SCS availability from the individual or couple’s perspective included lack of awareness about safer conception services [20, 22, 33, 36–42] and limited integration of services for sexual and reproductive health into HIV care [43–45]. Few patients discussed fertility goals with providers, and discussions around pregnancy focused on maternal and child health and not on sexual HIV transmission [39–41, 46].

For providers, availability was limited by: lack of training in SCSs, SCS service delivery, and preconception counselling for people living with HIV; health workforce shortages that limited the quality of counselling; poor linkages to HIV care; and lack of integration of HIV and reproductive health services (leading providers to think that SCS is someone else’s responsibility) [22, 24, 27, 35, 47–51]. Studies showed that provider training and self-efficacy in talking about SCS increased SCS availability [35]. Many providers working with patients living with HIV desired additional training on SCS as they were concerned with HIV transmission and future children’s health [22, 50, 52, 53]; however, tailored guidelines and training may be required for providers to implement SCS [51, 54, 55].

Topic 2: Feasibility and/or Acceptability of Safer Conception Strategies for HIV-Affected Heterosexual Couples (Tables 1, 2)

Most of the studies reviewed included analysis of feasibility and acceptability of SCS for HIV-affected couples (32 of 41 studies, 78%). Overall, five studies found that HIV-affected couples who wanted to have children desired to learn more about SCS [27, 50, 55–57]. Studies found that interventions that are currently offered to all HIV patients may be more feasible to be adapted for safer conception. For example, ART is already widely available for HIV-infected partners in discordant couples in Africa and was the most adaptable intervention in the studies we identified [11, 12, 19, 36, 58]. Women, men, and couples expressed willingness to access safer conception interventions and desired counseling [11, 12, 15, 19, 22, 30, 31, 40, 42, 50, 55, 59, 60]. However, patients expressed difficulty disclosing their serostatus to their partners [46, 54, 61], and male partners were often uninvolved in safer conception conversations [39, 61] though two studies found that HIV-infected men desired knowledge about SCS [41, 43]. Patients also were concerned about negative reactions from health care providers if they expressed desire to have children [41, 46, 51]. In addition, gender power dynamics in heterosexual HIV affected couples may affect the implementation of SCS. This manifested in several ways including: a lack of male involvement in safer conception conversations [57, 61, 62], unequal decision-making power within couples with respect to having children [43, 63], men and women having differing reasons for wanting children [22, 29, 52, 64], and differing SCS preferences depending on which partner was HIV-infected (e.g. ART preferred when male was positive, self-insemination when female was positive) [20, 22]. Finally, financial limitations [30, 51, 57], limited safer conception resources [11, 48, 51] and social stigma [22, 27, 57] were cited as barriers to safer conception feasibility.

Studies found that providers faced challenges when discussing SCS when one partner was HIV-infected but had not yet disclosed his or her serostatus to their partner due to confidentiality issues, lack of couple’s HIV counseling and testing, one partner being more involved than the other [40, 54, 61], and differences in acceptability of SCS given prior HIV disclosure [43]. Many studies identified provider level barriers to SCS acceptability including providers being indifferent or opposed to people living with HIV having children [22, 39, 47, 51–53] or providers expressing discomfort discussing sex, especially condomless sex in patients living with HIV, thus limiting SCS discussions [20, 50, 51]. As a result, some providers did not recommend child-bearing for people living with HIV or serodiscordant couples due to secondary transmission concerns [22, 65].

SCS adherence was evaluated in three studies which found that couples seeking to conceive may have better adherence to ART or PrEP when compared with couples not trying to conceive [12, 35, 48]. Another study found that PrEP adherence was greater than 80% among Kenyan and Ugandan HIV-uninfected women in serodiscordant relationships who were attempting to conceive over a 36-month period (Tenofovir detected in 71% of visits where the pregnancy was discovered, similar to non-pregnant women, p > 0.1) [30]. The same study found that pregnancy incidence was 10.2 per 100 person-years (n = 1785) in women on PrEP indicating that PrEP may be acceptable and feasible as a SCS in HIV-uninfected women with HIV-infected partners. Matthews et al. found that Ugandan HIV-infected women trying to conceive had highest levels of ART adherence during peri-conception periods (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.15, 95% CI 1.33, 3.49) when compared to non-pregnant women during a six-year study [58].

Studies in South Africa and Uganda identified that serodiscordant couples were confident that they could implement ART, self-insemination, and TUI [12, 19, 25], as well as PrEP [13, 28, 30] and VMMC [19]. However, male participants from several studies expressed disapproval regarding the use of sperm washing; some believed it could negatively impact the child’s birth [49], while others questioned whether the child would really be theirs if it was not conceived via traditional sex [12, 31, 50].

Topic 3: Promotional and/or Educational Strategies Used to Increase Uptake and/or Provision of Safer Conception Strategies (Table 1, 2)

Overall, 18 of the 41 studies (44%) evaluated promotional or educational strategies to increase uptake or provision of SCS. Thirteen studies were qualitative assessments of healthcare providers and people living with HIV or serodiscordant couples. Several studies found that providers rarely initiated discussion of fertility intentions and reproductive goals with HIV-affected clients during visits [24, 39, 41, 42, 46, 50, 58, 65]. When fertility intentions were assessed, usually only the woman’s reproductive goals were discussed and not the man’s or couples [58, 61]. Providers’ limited understanding of SCS impacted their ability and self-efficacy to provide SCS counseling and methods [35, 47, 48, 50, 52, 53].

Stigma around having children and living with HIV was also a common barrier to providing SCS information or education. Mmeje et al. found that HIV-infected individuals experienced stigma from their communities and fear of vertical transmission, so do not discuss fertility intentions with their providers [54]. Other studies found that education and building awareness around SCS impacts uptake and acceptability of safer conception services in HIV-affected couples [25, 36, 46, 55, 56, 59, 60], but patients fear of judgment for wanting children remained a barrier to receiving SCS counseling and education [27, 46, 51, 54].

Our review found that provider attitudes and provision of safer conception counseling were largely explored in qualitative studies with limited evidence from quantitative studies. One study by Goggin et al. in Uganda evaluated correlates of self-efficacy for the provision of safer conception counseling and found that despite a general awareness about SCS, especially timed unprotected intercourse, about half of providers felt they knew enough to counsel clients and most wanted more training [35]. Self-efficacy was greatest in providers who had more SCS awareness, perceived fewer barriers to SCS provision, and demonstrated greater intentions to counsel patients on the importance of timed unprotected intercourse [35]. One randomized futility trial evaluated the integration of sexual and reproductive health into public sector HIV care in South Africa. This study found that in patients who were newly diagnosed as HIV-infected, a provider-delivered intervention in an HIV clinic helped HIV affected couples make decisions about their various options, including the risks, benefits, and options associated with safer sex, parenting options and fertility [55].

A cohort study in South Africa provided periconception HIV prevention methods depending on the couples’ HIV serostatus, including ART for HIV-infected partners, PrEP for HIV-uninfected partners, self-insemination using a syringe, VMMC and TUI [11]. Clients were given counseling and recommended strategies based on their individual and relationship dynamics and serostatus, and all services were provided in the clinic except VMMC. ART initiation was highest (90%), followed by vaginal self-insemination in partnerships with HIV-uninfected men (75%) and timed unprotected intercourse (48%). PrEP uptake was lower at 7% of men and 44% of women and VMMC was used by 28% of HIV-uninfected men [11]. The study found SCS strategy continuation during attempted conception in over 60% of participants [11].

Discussion

Our systematic review of safer conception strategies is the first to compile evidence around SCS availability, feasibility and/or acceptability, and promotion/education strategies in sub-Saharan Africa. Our review identified 41 studies that met our criteria, of which 26 were qualitative. The review found that SCS were largely unavailable in sub-Saharan Africa outside of research settings, except for general availability (i.e., not for safer conception specifically) of ART and VMMC. Availability of SCS methods was greatest in public health facilities providing general services for people living with HIV [20–26, 31, 36, 39–44, 47–50, 56, 58, 59, 62, 63, 66–68]. More advanced or expensive strategies such as sperm washing, or PrEP remain unavailable in most public health facilities due to cost and lack of provider training [14–17, 23]. However, PrEP access is increasing in East and Southern Africa, and sperm washing may become available in other high HIV incidence settings with ongoing efforts to develop lower-cost technologies [30, 37, 46, 69]. Several studies demonstrated the need for increased provider training on SCS to increase availability to services [24, 45, 48–51, 70] and additional studies demonstrating the efficacy of SCS provider training curricula in different settings, such as the Safer Conception Counseling Tooklit [54], are warranted.

Our review found that many safer conception strategies were acceptable when provided to people living with HIV and desiring children, and that once educated about SCS, couples expressed confidence that they could effectively implement one of the safer conception strategies, despite some hesitations regarding the use of sperm washing among HIV-infected men [27, 29, 47, 57, 65, 71]. While HIV affected couples were generally eager to learn more about safer conception [27, 36, 39, 44, 46, 48, 51, 54, 72–74], there are numerous barriers to SCS access including stigma around HIV-affected couples wanting and bearing children [46]. Like our review, a recent consensus statement supporting safer conception and pregnancy for couples living with HIV found that access to SCS is limited by stigma toward HIV affected couples having children and that this stigma limits provision of safer conception services [75]. Increasing community education about SCSs via community health worker networks may help increase acceptability for previously unfamiliar conception strategies and reduce community-, provider-, or family-level stigma around pregnancy in HIV affected couples, as was accomplished with increasing community knowledge and acceptance of HIV testing [76, 77] and couples’ HIV counseling and testing [78–80].

Another barrier to SCS access among HIV affected couples is challenges with HIV serostatus disclosure [22, 24, 45, 49, 50, 64]. Prior studies have shown that serostatus disclosure can be facilitated by couples’ HIV counseling and testing which provides a counselor-mediated venue for serostatus disclosure and is also an opportunity to reach HIV-affected couples to discuss their fertility goals [81, 82] and potentially improve their ability to communicate about safer conception. The recent consensus statement supporting safer conception and pregnancy for couples living with HIV also highlighted couples-based HIV testing as an important strategy, and prior studies have demonstrated the impact of couples’ HIV testing on sustained reduction in risk behaviors over time [81].

Finally, our review highlights the need for integration of safer conception services for HIV affected couples into both HIV and sexual and reproductive health services, as lack of integration was discussed as a barrier to SCS service provision [24, 45, 48–50]. We advocate for the integration of SCS service provision within HIV testing, couples’ HIV counseling and testing, and in conjunction with partner notification [82, 83] services.

This systematic review has limitations. First, we did not find common quantitative outcomes across the studies and as such, we were unable to conduct a meta-analysis. Another limitation is the limited geographic coverage of the research conducted to date. The included studies were from six African countries (Kenya, Uganda, Malawi, Nigeria, South Africa and Tanzania), limiting generalizability to other countries and settings. We did not identify studies on cost-effectiveness of SCS in prevention of HIV transmission or pregnancy outcomes. Given the relatively high costs of some of the SCS options such as PrEP and sperm washing, such analyses will be important to cost-effective SCS scale-up.

Conclusion

Currently, the most available SCSs in sub-Saharan Africa are those not requiring advanced technology (e.g., timed unprotected intercourse) or strategies that are already in place (ART for HIV-infected individuals, VMMC for HIV-uninfected men). More advanced methods such as PrEP or sperm washing were largely unavailable. Provider training and patient education about SCS remain low, especially for couples. However, HIV affected couples have expressed a general desire to learn more about safer conception though they face issues with stigma and serostatus disclosure. Providers have also expressed desire to learn more about providing SCS, though stigma around discussing reproductive health with HIV affected couples is a barrier. Integration of SCS into HIV, reproductive health, and couples’ HIV counseling and testing will be essential to guaranteeing access to safer methods implementation of SCS in sub-Saharan Africa. Future research on SCS would benefit from common outcomes to increase comparability between studies, cost-effectiveness of SCS, and a deeper examination of the facilitators of SCS implementation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the students, interns and fellows who worked on this review. We would also like to acknowledge all of the researchers and study participants who were included in our review.

Funding We received funding from NIH-NIAID-T32DA023356 and NIH/FIC R25TW009340.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent N/A (this is a systematic review of existing literature).

References

- 1.UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic, 2013. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en.pdf Accessed 28 July 2017.

- 2.Schwartz SR, Rees H, Mehta S, Venter WD, Taha TE, Black V. High incidence of unplanned pregnancy after antiretroviral therapy initiation: findings from a prospective cohort study in South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myer L, Carter RJ, Katyal M, et al. Impact of antiretroviral therapy on incidence of pregnancy among HIV-infected women in Sub-Saharan Africa: a cohort study. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000229 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taulo F, Berry M, Tsui A, et al. Fertility intentions of HIV-1 infected and uninfected women in Malawi: a longitudinal study. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(Suppl 1):20–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beyeza-Kashesya J, Kaharuza F, Mirembe F, Neema S, Ekstrom AM, Kulane A. The dilemma of safe sex and having children: challenges facing HIV sero-discordant couples in Uganda. Afr Health Sci 2009;9:2–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mugo NR, Heffron R, Donnell D, et al. Increased risk of HIV-1 transmission in pregnancy: a prospective study among african HIV-1 serodiscordant couples. AIDS. 2011;25:1887–95. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834a9338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vitorino RL, Grinsztejn BG, de Andrade CAF, et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness and safety of assisted reproduction techniques in couples serodiscordant for human immunodeficiency virus where the man is positive. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1684–90. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.01.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiore JR, Lorusso F, Vacca M, et al. The efficiency of sperm washing in removing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 varies according to the seminal viral load. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:232–4. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bujan L, Hollander L, Coudert M, et al. Safety and efficacy of sperm washing in HIV-1-serodiscordant couples where the male is infected: results from the European CREAThE network. AIDS. 2007;21:1909–14. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282703879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savasi V, Mandia L, Laoreti A, et al. Reproductive assistance in HIV serodiscordant couples. Hum Reprod Update 2013;19:136–50. 10.1093/humupd/dms046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz SR, Bassett J, Sanne I, et al. Implementation of a safer conception service for HIV-affected couples in South Africa. AIDS. 2014;28:S277–85. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartz SR, West N, Phofa R, et al. Acceptability and preferences for safer conception HIV prevention strategies: a qualitative study. Int J STD AIDS 2016;27:984–92. 10.1177/0956462415604091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matthews LT, Baeten JM, Celum C, et al. Periconception pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV transmission: benefits, risks, and challenges to implementation. AIDS. 2010;24:1975–82. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833bedeb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:643–56. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mmeje O, Cohen C, Murage A, et al. Promoting reproductive options for HIV-affected couples in sub-Saharan Africa. BJOG. 2014;121:79–86. 10.1111/1471-0528.12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chemaitelly H, Cremin I, Shelton J, et al. Distinct HIV discordancy patterns by epidemic size in stable sexual partnerships in sub-Saharan Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88:51–7. 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brubaker SG, Bukusi EA, Odoyo J, Achando J, Okumu A, Cohen CR. Pregnancy and HIV transmission among HIV-discordant couples in a clinical trial in Kisumu. Kenya. HIV Med 2011;12(5):316–21. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The prisma statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLOS Med. 2009;6:e1000100 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartz SR, Bassett J, Holmes CB, et al. Client uptake of safer conception strategies: implementation outcomes from the Sakh’umndeni safer conception clinic in South Africa. J Int AIDS Society. 2017. 10.7448/ias.20.2.2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steiner RJ, Black V, Rees H, et al. Low receipt and uptake of safer conception messages in routine HIV care: findings from a prospective cohort of women living with HIV in South Africa. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72:105–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ngure K, Baeten JM, Mugo N, et al. My intention was a child but I was very afraid: fertility intentions and HIV risk perceptions among HIV-serodiscordant couples experiencing pregnancy in Kenya. AIDS Care. 2014;26:1283–7. 10.1080/09540121.2014.911808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Zyl C, Visser MJ. Reproductive desires of men and women living with HIV: implications for family planning counselling. Reprod BioMed Online. 2015;31:434–42. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teasdale CA, Marais BJ, Abrams EJ. HIV: prevention of mother-to-child transmission. BMJ Clin Evid 2011;2011.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3217724/. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Kawale P, Mindry D, Phoya A, et al. Provider attitudes about childbearing and knowledge of safer conception at two HIV clinics in Malawi. Reprod Health. 2015. 10.1186/s12978-015-0004-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagner GJ, Woldetsadik MA, Beyeza-Kashesya J, et al. Multilevel correlates of safer conception methods awareness and attitudes among Ugandan HIV clients with fertility intentions. Afr J Reprod Health. 2016;20:40–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zash R, Souda S, Chen JY, et al. Reassuring birth outcomes with tenofovir/emtricitabine/efavirenz used for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Botswana. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71:428–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mmeje O, van der Poel S, Workneh M, et al. Achieving pregnancy safely: perspectives on timed vaginal insemination among HIV-serodiscordant couples and health-care providers in Kisumu, Kenya. AIDS Care. 2015;27:10–6. 10.1080/09540121.2014.946385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Were EO, Heffron R, Mugo NR, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis does not affect the fertility of HIV-1-uninfected men. AIDS. 2014;28:1977–82. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delany-Moretlwe S, Mullick S, Eakle R, et al. Planning for HIV preexposure prophylaxis introduction: lessons learned from contraception. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11:87–93. 10.1097/COH.0000000000000221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matthews LT, Heffron R, Mugo NR, et al. High medication adherence during periconception periods among HIV-1–uninfected women participating in a clinical trial of antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67:91–7. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor TN, Mantell JE, Nywagi N, et al. ‘He lacks his fatherhood’: safer conception technologies and the biological imperative for fatherhood among recently-diagnosed Xhosa-speaking men living with HIV in South Africa. Cult Health Sex. 2013;15:1101–14. 10.1080/13691058.2013.809147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hancuch K, Baeten J, Ngure K, Celum C, Mugo N, Tindimwebwa E. Heffron R; Partners Demonstration Project Team. Safer conception among HIV-1 serodiscordant couples in East Africa: understanding knowledge, attitudes, and experiences. AIDS Care. 2018;17:1–9. 10.1080/09540121.2018.1437251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner GJ, Linnemayr S, Goggin K, Mindry D, Beyeza-Kashesya J, Finocchario-Kessler S, Robinson E, Birungi J, Wanyenze RK. Prevalence and correlates of use of safer conception methods in a prospective cohort of Ugandan HIV-affected couples with fertility intentions. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(8):2479–87. 10.1007/s10461-017-1732-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ezeanochie M, Olagbuji B, Ande A, et al. Fertility preferences, condom use, and concerns among HIV-infected women in serodiscordant relationships in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Int J Gynecol Obst. 2009;107:97–8. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goggin K, Finocchario-Kessler S, Staggs V, et al. Attitudes, knowledge, and correlates of self-efficacy for the provision of safer conception counseling among ugandan HIV providers. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29:651–60. 10.1089/apc.2015.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matthews LT, Smit JA, Moore L, et al. Periconception HIV risk behavior among men and women reporting HIV-serodiscordant partners in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:2291–303. 10.1007/s10461-015-1050-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fourie JM, Loskutoff N, Huyser C. Semen decontamination for the elimination of seminal HIV-1. Reprod BioMed Online. 2015;30:296–302. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mmeje O, Cohen CR, Cohan D. Evaluating safer conception options for HIV-serodiscordant couples (HIV-infected female/HIV-uninfected male): a closer look at vaginal insemination. Infec Dis Obst Gynecol. 2012;2012:1–7. 10.1155/2012/587651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawale P, Mindry D, Stramotas S, et al. Factors associated with desire for children among HIV-infected women and men: a quantitative and qualitative analysis from Malawi and implications for the delivery of safer conception counseling. AIDS Care. 2014;26:769–76. 10.1080/09540121.2013.855294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matthews LT, Crankshaw T, Giddy J, et al. Reproductive counseling by clinic healthcare workers in Durban, South Africa: perspectives from HIV-infected men and women reporting serodiscordant partners. Infec Dis in Obst Gynecol. 2012;2012:1–9. 10.1155/2012/146348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matthews LT, Moore L, Milford C, et al. “If I don’t use a condom… I would be stressed in my heart that I’ve done something wrong”: routine prevention messages preclude safer conception counseling for HIV-infected men and women in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:1666–75. 10.1007/s10461-015-1026-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matthews LT, Bajunirwe F, Kastner J, et al. I Always worry about what might happen ahead: implementing safer conception services in the current environment of reproductive Counseling for HIV-affected men and women in Uganda. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:1–9. 10.1155/2016/4195762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khidir H, Psaros C, Greener L, et al. Developing a safer conception intervention for men living with HIV in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2017. 10.1007/s10461-017-1719-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sturt AS, Dokubo EK, Sint TT. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) for treating HIV infection in ART-eligible pregnant women In: The Cochrane Collaboration, ed. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Wiley, Chichester: 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saleem HT, Surkan PJ, Kerrigan D, et al. Application of an ecological framework to examine barriers to the adoption of safer conception strategies by HIV-affected couples. AIDS Care. 2016;28:197–204. 10.1080/09540121.2015.1074652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beyeza-Kashesya J, Wanyenze RK, Goggin K, Finocchario-Kessler S, Woldetsadik MA, Mindry D, et al. Stigma gets in my way: factors affecting client-provider communication regarding childbearing among people living with HIV in Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(2):e0192902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moodley J, Cooper D, Mantell JE, et al. Health care provider perspectives on pregnancy and parenting in HIV-infected individuals in South Africa. BMC Health Services Research. 2014;14:384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ngure K, Kimemia G, Dew K, et al. Delivering safer conception services to HIV serodiscordant couples in Kenya: perspectives from healthcare providers and HIV serodiscordant couples. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017. 10.7448/ias.20.2.21309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Finocchario-Kessler S, Wanyenze R, Mindry D, et al. “I may not say we really have a method, it is gambling work”: knowledge and acceptability of safer conception methods among providers and HIV clients in Uganda. Health Care Women Int. 2014;35:896–917. 10.1080/07399332.2014.924520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mindry DL, Milford C, Greener L, et al. Client and provider knowledge and views on safer conception for people living with HIV (PLHIV). Sex Reprod Healthcare. 2016;10:35–40. 10.1016/j.srhc.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.West N, Schwartz S, Phofa R, et al. “I don’t know if this is right… but this is what I’m offering”: healthcare provider knowledge, practice, and attitudes towards safer conception for HIV-affected couples in the context of Southern African guidelines. AIDS Care. 2016;28:390–6. 10.1080/09540121.2015.1093596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matthews LT, Milford C, Kaida A, et al. Lost opportunities to reduce periconception HIV transmission: safer conception counseling by south african providers addresses perinatal but not sexual HIV transmission. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67:S210–7. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000374(B). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mindry DL, Crankshaw TL, Maharaj P, et al. “We have to try and have this child before it is too late”: missed opportunities in client-provider communication on reproductive intentions of people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2015;27:25–30. 10.1080/09540121.2014.951311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mmeje O, Njoroge B, Akama E, et al. Perspectives of healthcare providers and HIV-affected individuals and couples during the development of a safer conception counseling Toolkit in Kenya: stigma, fears, and recommendations for the delivery of services. AIDS Care. 2016;28:750–7. 10.1080/09540121.2016.1153592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mantell JE, Cooper D, Exner TM, et al. Emtonjeni-A Structural Intervention to Integrate Sexual and Reproductive Health into Public Sector HIV Care in Cape Town, South Africa: results of a Phase II Study. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:905–22. 10.1007/s10461-016-1562-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matthews LT, Smit JA, Cu-Uvin S, et al. Antiretrovirals and safer conception for HIV-serodiscordant couples. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7:569–78. 10.1097/COH.0b013e328358bac9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Breitnauer BT, Mmeje O, Njoroge B, et al. Community perceptions of childbearing and use of safer conception strategies among HIV-discordant couples in Kisumu, Kenya. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015. 10.7448/ias.18.1.19972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matthews LT, Ribaudo HB, Kaida A, et al. HIV-infected Ugandan women on antiretroviral therapy maintain HIV-1 RNA suppression across periconception, pregnancy, and postpartum periods. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71:399–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matthews LT, Crankshaw T, Giddy J, et al. Reproductive decision-making and periconception practices among HIV-infected men and women attending HIV services in Durban, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:461–70. 10.1007/s10461-011-0068-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wagner GJ, Goggin K, Mindry D, et al. Correlates of Use of timed unprotected intercourse to reduce horizontal transmission among Ugandan HIV clients with fertility intentions. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:1078–88. 10.1007/s10461-014-0906-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Crankshaw TL, Mindry D, Munthree C, et al. Challenges with couples, serodiscordance and HIV disclosure: healthcare provider perspectives on delivering safer conception services for HIV-affected couples, South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014. 10.7448/ias.17.1.18832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaida A, Matthews LT, Kanters S, et al. Incidence and predictors of pregnancy among a cohort of HIV-infected women initiating antiretroviral therapy in Mbarara, Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e63411 10.1371/journal.pone.0063411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pintye J, Ngure K, Curran K, et al. Fertility decision-making among Kenyan HIV-serodiscordant couples who recently conceived: implications for safer conception planning. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29:510–6. 10.1089/apc.2015.0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matthews LT, Burns BF, Bajunirwe F, Kabakyenga J, Bwana M, Ng C, et al. Beyond HIV-serodiscordance: partnership communication dynamics that affect engagement in safer conception care. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(9):e0183131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nosarka S, Hoogendijk CF, Siebert TI, et al. Assisted reproduction in the HIV-serodiscordant couple. S Afr Med J. 2007;97:24–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kuete M, Yuan H, Tchoua Kemayou AL, et al. Scale up use of family planning services to prevent maternal transmission of HIV among discordant couples: a cross-sectional study within a resource-limited setting. Patient Prefer Adher. 2016;10:1967–77. 10.2147/PPA.S105624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rao A, Baral S, Phaswana-Mafuya N, et al. Pregnancy intentions and safer pregnancy knowledge among female sex workers in Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Obst Gynecol. 2016;128:15–21. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saleem HT, Surkan PJ, Kerrigan D, et al. Application of an ecological framework to examine barriers to the adoption of safer conception strategies by HIV-affected couples. AIDS Care. 2016;28:197–204. 10.1080/09540121.2015.1074652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zafer M, Horvath H, Mmeje O, et al. Effectiveness of semen washing to prevent HIV transmission and assist pregnancy in HIV-discordant couples: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil steril. 2016;105(3):645–645.e2. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ddumba-Nyanzi I, Kaawa-Mafigiri D, Johannessen H. Barriers to communication between HIV care providers (HCPs) and women living with HIV about child bearing: a qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:754–9. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Noreh LJ, Tucs O, Sekadde-Kigondu CB, et al. Outcomes of assisted reproductive technologies at the Nairobi In Vitro Fertilisation Centre. East Afr Med J 2009; https://www.ajol.info/index.php/eamj/article/view/46944 Accessed 30 Jun 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Dyer SJ, Kruger TF. Assisted reproductive technology in South Africa: first results generated from the South African Register of Assisted Reproductive Techniques. S Afr Med J. 2012;102:167–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guthrie BL, Choi RY, Bosire R, et al. Predicting pregnancy in HIV-1-discordant couples. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:1066–71. 10.1007/s10461-010-9716-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hayford SR, Agadjanian V, Luz L. Now or never: perceived HIV status and fertility intentions in rural Mozambique. Stud Fam Plann. 2012;43:191–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Matthews LT, Beyeza-Kashesya J, Cooke I, Davies N, Heffron R, Kaida A, Kinuthia J, Mmeje O, Semprini AE, Weber S. Consensus statement: supporting safer conception and pregnancy for men and women living with and affected by hiv. AIDS Behav. 2017. 10.1007/s10461-017-1777-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Asiimwe S, Ross JM, Arinaitwe A, et al. Expanding HIV testing and linkage to care in southwestern Uganda with community health extension workers. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(Suppl 4):21633 10.7448/IAS.20.5.21633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Suthar AB, Ford N, Bachanas PJ, Towards Universal Voluntary HIV, et al. Testing and counselling: a systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based approaches. Sansom SL, ed. PLoS Med. 2013;10(8):e1001496 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]