Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Accurate identification of the earliest cognitive changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is critically needed. Item-level information within tests of category fluency, such as lexical frequency, harbors valuable information about the integrity of semantic networks affected early in AD. To determine the potential of lexical frequency as a cognitive marker of AD risk, we investigated whether lexical frequency of animal fluency output differentiated APOE ε4 carriers from non-carriers in a cross-sectional design among older African American adults without dementia.

METHOD:

We analyzed animal fluency performance using mean number of items and mean lexical frequency among 230 cognitively normal African Americans with and without the APOE ε4 allele.

RESULTS: Lexical frequency was higher in APOE ε4 carriers than non-carriers when analyzed as a mean score and within time bins. In contrast, we found no group difference in the number of items produced. Lexical frequency was particularly sensitive to ε4-status after the first 10 seconds of the 60-second animal fluency task.

CONCLUSION:

Our results suggest that psycholinguistic features may hold value as a cognitive biomarker for identifying people at high risk of AD.

Keywords: verbal fluency, category fluency, Alzheimer’s disease, lexical frequency, psycholinguistic

1. Introduction

Deficits in semantic memory—general knowledge of facts, concepts, and the meaning of words—are well-known to be among the first clinical signs of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Butters, Granholm, Salmon, Grant, & Wolfe, 1987; Dudas, Clague, Thompson, Graham, & Hodges, 2005; Joubert et al., 2010; Petersen, Smith, Ivnik, Kokmen, & Tangalos, 1994). AD affects access to the underlying concept of a word (i.e., its meaning) (Joubert et al., 2010), and thus an often-reported symptom is subjective experience of word-finding difficulties (Clarnette, Almeida, Forstl, Paton, & Martins, 2001). Accurate identification of such early cognitive changes associated with AD is critically needed to support early detection. A convincing body of evidence from longitudinal studies has shown that cognitive change within an individual occurs years, even decades before clinical threshold for dementia occurs (Amieva et al., 2008; Bäckman, Jones, Berger, Laukka, & Small, 2005; Chen et al., 2001; Elias et al., 2000; Rajan, Wilson, Weuve, Barnes, & Evans, 2015). However, these changes are subtle and only detectable within-person over time (Papp et al., 2016). For example, the tests commonly used to assess verbal fluency, widely accepted as measures of semantic memory, usually focus on total correct score and the relative score of category fluency to letter fluency. These scores are sensitive markers for MCI (Murphy, Rich, & Troyer, 2006), AD (Monsch et al., 1992), and longitudinal decline in the preclinical stage of AD (Papp, Rentz, Orlovsky, Sperling, & Mormino, 2017), but are unable to detect preclinical AD on a cross-sectional basis (Papp et al., 2016).

Embedded in verbal fluency tasks, however, is qualitative, psycholinguistic information such as lexical frequency (i.e., how often a word occurs in daily language). Lexical frequency affects both word comprehension and production in healthy individuals, such that words with a higher frequency are recognized and produced more accurately and quicker than words with a lower frequency (Balota, Cortese, Sergent-Marshall, Spieler, & Yap, 2004; Kucera & Francis, 1982). Moreover, lexical frequency influences language decline in neurological conditions, including AD (Balota, Burgess, Cortese, & Adams, 2002; Bird, Lambon Ralph, Patterson, & Hodges, 2000; Kremin et al., 2001). Semantic decline in AD first affects words with low frequency (Bird et al., 2000). For example, patients with progressive semantic impairment are likely to lose lower frequency words first (e.g., lynx, platypus, puma) before more frequent words become affected (e.g., dog, horse, bird). Thus, analyses of the item-level lexical frequency of fluency output may reveal reduced depth and extent of the integrity of the semantic network and may be able to detect AD-related cognitive decline at an earlier stage than the traditional “total correct” score.

The current study is part of a larger project investigating the genetic and environmental pathways of AD pathogenesis in African Americans (Hamilton et al., 2014; Meier et al., 2012). The epsilon 4 allele of the apolipoprotein E gene (APOE ε4) is a well-established risk factor for AD (Corder et al., 1993; Evans et al., 1997; Honig, Schupf, Lee, Tang, & Mayeux, 2006; Tang et al., 1998). While the relative risk for AD associated with APOE ε4 is lower among African Amerians than among non-Hispanic Whites (Tang et al., 1996), several studies have shown that African Americans who are homo- or heterozygous for the e4 allele are at increased odds of developing AD and cognitive impairment (Farrer et al., 1997; Graff-Radford et al., 2002; Hendrie et al., 1995; Logue et al., 2011; Reitz et al., 2013; Sinha et al., 2018). Multiple studies show that among cognitively healthy older adults, and independent of demographic variables such as age, sex, and education, African Americans obtain lower neuropsychological scores compared with non-Hispanic Whites, including measures of category fluency (Gladsjo et al., 1999; Johnson-Selfridge, Zalewski, & Aboudarham, 1998; Manly et al., 1998; Manly, Jacobs, Touradji, Small, & Stern, 2002). The current study sought to identify whether a novel measure of cognitive functioning could detect differences between individuals at higher genetic risk for AD compared with those at lower risk in this less well-studied population.

To determine the potential of lexical frequency as a cognitive marker of AD risk, we investigated whether lexical frequency of animal fluency output differentiated APOE ε4 carriers from non-carriers in a cross-sectional design among older African American adults without dementia. Given that AD is thought to first affect low-frequency words, we hypothesized that mean lexical frequency would predict AD genetic risk (having the APOE ε4 allele). In contrast, we hypothesized that the number of items generated during the animal fluency trial would not differ across APOE ε4 status. The total number of items per participant is variable, which intrinsically influences the mean lexical frequency value; therefore, we also performed time-bin analyses. We expected that when the items generated during the 60-second task were separated into 10-second bins, mean lexical frequency would lower across time, since most people start with familiar animals and produce less familiar exemplars as the task develops. Additionally, we expected between-group comparisons at each of the six time bins to show higher lexical frequency in the APOE ε4 carriers than non-carriers, but no difference in number of items.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were recruited from the African American Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics Study, a multi-site effort including research teams from Columbia University, North Carolina A&T State University, University of Miami, and Vanderbilt University (recruitment and selection procedures described in detail in Hamilton et al. (Hamilton et al., 2014)). This study focused on the participants recruited at the Columbia University site, because their verbal fluency task performance was recorded and entered at the item-level across 10-second time bins.

A total of 230 cognitively healthy individuals (Clinical Dementia Rating, i.e., CDR = 0) were included, whose demographic characteristics are represented in Table 1. Inclusion criteria were for participants to have English as their first language, to be born in the United States, to self-identify as Black or African American and non-Hispanic based on U.S. Census criteria (Census Bureau, 2001), to be genetically tested for the APOE ε4 allele, and to have no history of reported clinical stroke, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, or other non-AD dementia. The diagnosis of being cognitively healthy was made in a consensus case conference based on neurological, neuropsychological, medical, psychiatric, and functional evaluations following standard research criteria for MCI, all-cause dementia, AD, and other non-AD dementias (Albert et al., 2011; McKhann et al., 2011). The fluency measures were among multiple measures in the neuropsychological battery. Participants gave written consent and were compensated for their participation in accordance with the Institutional Review Board at Columbia University Medical Center.

Table 1.

Demographic information and animal fluency performance

| APOE ε4- (n = 145) | APOE ε4+ (n = 85) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age (years) | 68.1 ±7.2 [55–86] | 68.1 ±7.2 [55–86] |

| Sex | 20% m, 80% f | 19% m, 81% f |

| Years of education | 14.6 ±2.8 [6–20] | 14.6 ±2.4 [8–20] |

| MMSE | 28.4 ±1.7 [21–30] | 28.4 ±1.8 [20–30] |

| WRAT-3 | 45.5 ±6.0 [24–55] | 45.6 ±4.9 [29–57] |

| Measures | ||

| Mean lexical frequency | 2.744 ±.194 [2.034–3.093] | 2.796 ±.165 [2.431–3.221]* |

| Total number of items | 17.2 ±4.1 [7–29] | 16.6 ±3.6 [9–25] |

NOTE. Values presented as mean ±standard deviation [range]; n, number of participants; m, male; f, female; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; The Reading Recognition subtest from The Wide Range Achievement Test–Version 3 (WRAT-3) (Wilkinson, 1993) was used as a proxy for participants’ quality of education (data missing for n = 8);

P < .05

2.2. Materials and procedure

Participants were evaluated with a neuropsychological battery including tests of memory, orientation, language, abstract reasoning, and visuospatial ability, described in detail elsewhere (Hamilton et al., 2014; Meier et al., 2012). As part of their neuropsychological assessment, participants performed the animal fluency task. They were asked to verbally generate as many different animals as possible within 60 seconds. Their answers were written down within six 10-second blocks.

The analyses included correct items only. Each correctly produced word was paired with its log- transformed lexical frequency value from the SUBTLEXus database, which reflects the natural logarithmic value of how often a word form occurs per one million words in this corpus (https://www.ugent.be/pp/experimentele-psychologie/en/research/documents/subtlexus). The SUBTLEXus database is based on American subtitles of films and television series, a corpus of 51 million words that is validated to estimate American English daily language use closely (Brysbaert & New, 2009). A very small subset of words (0.69%) generated by participants included open form compound words (two words that together form one meaning, e.g., post office), for which alterations had to be made to derive a single-word frequency value.1

Participants were genotyped for APOE as described by Hixson and Vernier (1990) with slight modification and categorized as APOE ε4 positive (APOE ε4+; n = 85; 81 heterozygote) or negative (APOE ε4−; n = 145) based on the presence of the ε4 allele.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Distributional characteristics of demographic and performance variables were derived with descriptive statistics. Subsequently, we tested their relation to each other with Pearson correlation coefficients and a point-biserial correlation, and across diagnostic groups with independent-samples t- tests and a chi-square test. Chi-square tests were also used to examine if there was a different proportion of compound words that required alteration between the two groups.

Mean lexical frequency was calculated for each individual based on the lexical frequency values of their produced words across 60 seconds, as well as per 10-second time bin. The predictive relation between the two measures of fluency performance and APOE ε4 status was examined with logistic regression models; no covariates were entered into the models given that there were no demographic differences between the groups.

Responses to the animal fluency task were recorded within one of six 10-second bins in which they were generated by the participant, which allowed us to investigate performance throughout the task. Because of the self-paced and continuous nature of the task, analyses of different time points throughout the task require a cumulative outcome of the performance up to each time bin. To characterize within- and between-group task performance over time, we performed growth curve models. Model-fit comparisons guided us to use a model with a random intercept and random slope fitting a quadratic polynomial growth curve.

In addition to trajectory across time bins, we performed comparisons of task performance between groups at each time bin. These time-binned analyses of mean lexical frequency per bin and mean number of items per bin used general linear models, in which separate models were performed for cumulative values up until the next time bin for each 10-second interval.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristics

Individuals with and without APOE ε4 did not differ in age (t(228) = .045, P = .965), years of education (t(228) = .153, P = .879), sex (χ 2 = 0.047, P = .865), MMSE score (t(227) = .178, P = .859) or WRAT-3 performance (t(220) = −.236, P = .814) (Table 1). There were also no differences in compound words that required alterations between the groups (χ2 = 0.500, P = .479). Animal fluency performance correlated with years of education (number of items: r = .110, P = .097; lexical frequency: r = −.143, P = .030) and WRAT-3 (number of items: r = .227, P = .001; lexical frequency: r = −.274, P < .001). Older participants generated fewer items (r = −.329, P < .001), while overall mean lexical frequency did not correlate with age (r = .026, P = .695).

3.2. Lexical frequency vs. number of items

Individuals with higher overall mean lexical frequency values had a higher probability to be APOE ε4+ than those with lower values (P = .043, odds ratio, OR = 4.853; 95% confidence interval, CI = 1.049–22.263). In contrast, the mean number of items was not predictive of APOE ε4 status (P = .272, OR = .962; 95% CI = .898–1.031).

Growth curve models to characterize within-group task performance over time (i.e., across the 10-second response bins within the same testing session) indicated that cumulative mean lexical frequency declined across time bins and cumulative number of items increased for both APOE ε4- and APOE ε4+ individuals (Table 2). Notably, pairwise comparisons between successive time bins showed that within each group, while significant as an overall trajectory, lexical frequency declined from the first to the second time bin but remained stable within the subsequent time bins (Table 3). In contrast, the number of words generated increased between every time bin.

Table 2.

Growth curve parameters for standardized values of lexical frequency and number of items

| Lexical frequency | Number of items | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | P | 95% CI | B | SE B | P | 95% CI | |

| Total sample | ||||||||

| Time bin (linear) | −0.242 | 0.033 | < .001 | −0.307; −0.178 | 0.806 | 0.02 | < .001 | 0.766; 0.846 |

| Time bin2 (quadratic) | 0.02 | 0.004 | < .001 | 0.012; 0.029 | −0.052 | 0.002 | < .001 | −0.057; −0.047 |

| APOE ε4 group | −0.292 | 0.147 | 0.049 | −0.582; −0.001 | −0.042 | 0.054 | 0.438 | −0.148; 0.064 |

| Time bin2*group | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.531 | −0.004; 0.009 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.511 | −0.003; 0.007 |

| APOE ε4− | ||||||||

| Time bin (linear) | −0.261 | 0.043 | < .001 | −.345; −.178 | 0.842 | 0.026 | < .001 | 0.791; .892 |

| Time bin2 (quadratic) | 0.023 | 0.006 | < .001 | .012; .034 | −0.055 | 0.003 | < .001 | −0.061; −.049 |

| APOE ε4+ | ||||||||

| Time bin (linear) | −0.21 | 0.051 | < .001 | −0.310; −.109 | 0.745 | 0.033 | < .001 | 0.681; .809 |

| Time bin2 (quadratic) | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.03 | 0.001; .028 | −0.046 | 0.004 | < .001 | −.054; −.038 |

NOTE. B = estimate; SE = standard error; P = significance value; CI = confidence interval

Table 3.

Comparisons between successive time bins within APOE ε4 groups and between APOE ε4 group comparisons per bin of lexical frequency and number of items

| Lexical frequency | Number of items | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

APOE ε4- Mean ±SD |

APOE ε4+ Mean ±SD |

Between group P |

APOE ε4- Mean ±SD |

APOE ε4+ Mean ±SD |

Between group P |

|

| Bin 1 | 2.863 ±.308 | 2.917 ±0.259 | 0.176 | 6.4 ±1.6 | 6.7 ±1.9 | 0.236 |

| ↕ P = < .001 | ↕ P = < .001 | ↕ P = < .001 | ↕ P = < .001 | |||

| Bin 2 | 2.801 ±.211 | 2.872 ±0.200 | 0.014 | 10.0 ±2.1 | 9.8 ±2.1 | 0.201 |

| ↕ P = 0.163 | ↕ P = 0.102 | ↕ P = < .001 | ↕ P = < .001 | |||

| Bin 3 | 2.783 +.208 | 2.845 +0.171 | 0.021 | 12.3 +2.8 | 12.0 +2.6 | 0.296 |

| ↕ P = 0.218 | ↕ P = 0.388 | ↕ P = < .001 | ↕ P = < .001 | |||

| Bin 4 | 2.766 ±.205 | 2.831 ±0.163 | 0.014 | 14.3 ±3.1 | 13.9 ±2.8 | 0.288 |

| ↕ P = 0.378 | ↕ P = 0.172 | ↕ P = < .001 | ↕ P = < .001 | |||

| Bin 5 | 2.754 ±.203 | 2.808 ±0.166 | 0.038 | 16.0 ±3.7 | 15.3 ±3.4 | 0.195 |

| ↕ P = 0.462 | ↕ P = 0.440 | ↕ P = < .001 | ↕ P = < .001 | |||

| Bin 6† | 2.744 ±.194 | 2.796 ±0.165 | 0.041 | 17.2 ±4.1 | 16.6 ±3.6 | 0.272 |

NOTE. Equal to overall group comparison; SD = standard deviation; P = significance value;

= pairwise comparison between time bins

In a growth curve model that included a group-by-time bin interaction, we observed a main effect between groups with a higher lexical frequency in APOE ε4+ than APOE ε4- individuals (F(1, 212.769) = 3.912, P = .049), while there was no main effect of group for number of items (F(1, 227.942) = .604, P = .438). There was no difference in change over time of lexical frequency or number of words between the two groups (Table 2).

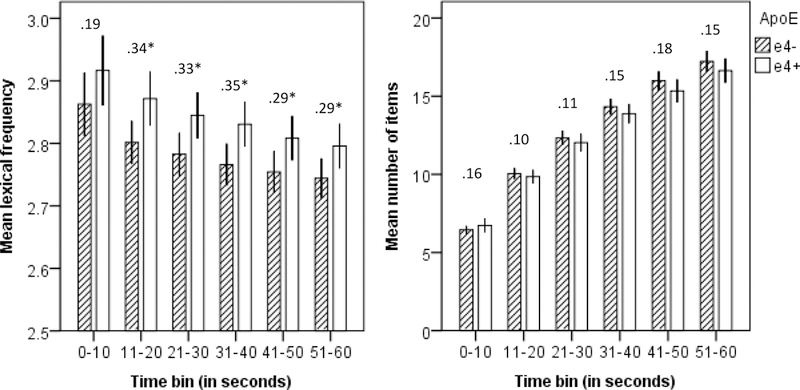

We also characterized task performance between groups at each time bin by analyzing the difference in cumulative mean lexical frequency and cumulative number of words between the two groups for each of the six 10-second time bins (Figure 1). Except for within the first 10 seconds of the animal fluency task, the cumulative mean lexical frequency was lower in the APOE ε4- group than in the APOE ε4+ group in all remaining five time bins (Table 3). In contrast, none of the group comparisons of number of animals generated per bin were significant.

Figure 1.

Animal fluency performance across task-time (number above bars represent effect size in Cohen’s d; *significant at the .05 level; 95% confidence interval error bars)

Qualitative inspection of participants’ earliest responses reveals a clear pattern of what are considered stereotypical animals in the western world (i.e., pets, zoo animals, characters in children’s books). For example, cat, dog, and lion were the top three most popular words to start with, as 70% of the people in the APOE ε4- group and 74% in the APOE ε4+ group used at least one of these within their first three produced words. As the task progressed, variety in answers increased. The observation that the majority of participants start animal fluency with the most familiar animals independent of APOE ε4 status is compatible with our finding that differences in lexical frequency between groups were observed only after the first 10 seconds of this 60-second task.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that differences in semantic processing can be detected between older African American adults with and without the APOE ε4 allele. We found that mean lexical frequency—a psycholinguistic characteristic of words—is uniquely sensitive to higher genetic risk for AD. The main effect of group on lexical frequency was not driven by a deviation from the ‘normal’ trajectory by the APOE ε4+ group, but the APOE ε4+ group consistently used higher frequency words than the APOE ε4- group. Secondly, while number of items steadily decreased within the 60-second task window, lexical frequency was relatively stable after the first 10 seconds. While several previous studies were able to detect cognitive change within-person over time in APOE ε4 carriers, biomarker-defined preclinical AD, or retrospectively in those who progressed to AD (M. W. Bondi et al., 1995; Elias et al., 2000; Papp et al., 2016), our ability to detect a difference in cognitive function between APOE ε4 carriers and non-carriers using a cross-sectional design is novel.

Verbal fluency taps multiple cognitive skills, and total number of produced items does not fully capture the information available from task performance (Troyer, Moscovitch, Winocur, Leach, & Freedman, 1998). Valuable information about semantic function is hidden at the item level. Our results showed that nearly all participants start animal fluency with the most familiar animals (e.g., cat, dog), as exemplified by no significant differences in mean lexical frequency between APOE ε4 groups in the first 10 seconds of the task. The rate of change for lexical frequency and number of items decreased across time bins, and did not differ between groups. However, between- APOE ε4-group comparisons at each time bin showed the strongest differences within the second, third, and fourth 10-second bins. These findings suggest that the APOE ε4+ participants had reduced ability to access less frequent words in their lexicon, especially after the first 10 seconds of the fluency task.

Previous research showed the validity of using item-level data to detect qualitative differences in fluency performance, including semantic decline in MCI and AD, through analyses of clustering in subcategories and switching between those beyond the power of the total number of items (Eng, Vonk, Salzberger, & Yoo, in press; Price et al., 2012; Troyer et al., 1998). A down-side of using clustering and switching measures is that they have to be manually coded and thus are time consuming and prone to rater bias. The lexical frequency measure used in this research study was easier to derive, and can be used by anyone with access to item-entered fluency data.

The earliest stages of AD are characterized by biological changes in the brain such as an accumulation of abnormal amyloid-beta and tau proteins and cerebral atrophy (Sperling et al., 2011). Several researchers claim that measures of cognitive ability are insensitive to these earliest biological changes that occur well before dementia and MCI criteria are met (Snyder et al., 2014), and claim that neuropsychological measures are the “last biomarker” to become abnormal in the trajectory of AD (Jack et al., 2013). Our results, however, suggest when the descriptive richness of participant responses is quantified (Ashendorf, Swenson, & Libon, 2013; Milberg, Hebben, Kaplan, Grant, & Adams, 2009), neuropsychological measures can be sensitive to AD risk when overall cognition and function are within normal limits, among people without subjective cognitive complaints (Mark W Bondi et al., 2014). These findings show the additive value of a qualitative approach in evaluating individuals at risk of AD. Future studies should explore the predictive strength of other psycholinguistic characteristics, such as age of acquisition and orthographic/phonological neighborhood density. Our sample consisted of exclusively African American individuals; therefore, a next step would be to examine lexical frequency in a multiethnic, multilinguistic cohort. While APOE ε4 is a risk factor of AD, not all carriers develop the disease, and the relation between APOE ε4 and AD is weaker among African Americans than among Whites (Farrer et al., 1997); therefore, we might expect that race/ethnicity will moderate the relationship between APOE ε4 status and measures of semantic processing. Thus, future studies should compare lexical frequency among those with and without positive biomarkers such as PET amyloid neuroimaging and retrospectively analyze lexical frequency among those who do and do not develop incident AD.

In sum, fluency tasks are well-established as valuable neuropsychological measures for AD diagnosis and for tracking severity of cognitive dysfunction along the preclinical MCI-AD continuum, however, the “total correct” score on fluency measures at a single time point has not been sensitive to AD risk during the preclinical stage (Papp et al., 2016). The premise for the current study is that decline in semantic memory and conceptual formation occurs years before the clinical diagnosis of AD can be established (Amieva et al., 2008). We found that psycholinguistic analyses of fluency data has the potential to increase utility of neuropsychological instruments in detection of AD risk within the preclinical stage, and thus may refine the definition of high-risk populations for clinical trials.

Public Significance Statement:

Decline in cognition occurs years before the symptoms are distinct enough to establish a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease based on traditional neuropsychological test scores. We showed that an alternative, psycholinguistic score of the category fluency task could predict AD genetic risk (having the APOE ε4 allele) in older adults whose overall cognition and function are within normal limits. These results suggest that psycholinguistic features may hold value as a cognitive biomarker for identifying people at high risk of AD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/National Institute on Aging grant R01 AG028786.

Footnotes

Alterations were made with ad hoc rules in the following order. If an open form compound word could be replaced with only the modifier of the compound and maintain the same meaning, we adjusted it accordingly (e.g., koala bear). If lexical frequency was available for a near-synonym, we imputed the value of the open form compound with that of the near-synonym (e.g., mountain lion to cougar). We imputed open form compounds with the lexical frequency of its modifier (i.e., the first word of the compound), postulating that that modifier in the majority of its occurrences is paired with that compound’s head (i.e., the second word of the compound; e.g., polar for polar bear). If this assumption could not be made, we imputed the open form compound with the lexical frequency of its head (e.g., buffalo for water buffalo). No lexical frequency value was available in the database for the small mammal “pika” (n = 1), which was therefore imputed with a log value equal to an occurrence of one in a million.

References

- Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Petersen RC (2011). The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 7(3), 270–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amieva H, Le Goff M, Millet X, Orgogozo JM, Pérès K, Barberger-Gateau P, Dartigues JF (2008). Prodromal Alzheimer’s disease: successive emergence of the clinical symptoms. Annals of Neurology, 64(5), 492–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashendorf L, Swenson R, & Libon DJ (2013). The Boston Process Approach to neuropsychological assessment: A practitioner’s guide: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bäckman L, Jones S, Berger A-K, Laukka EJ, & Small BJ (2005). Cognitive impairment in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychology, 19(4), 520–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balota DA, Burgess GC, Cortese MJ, & Adams DR (2002). The word-frequency mirror effect in young, old, and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence for two processes in episodic recognition performance. Journal of Memory and Language, 46(1), 199–226. [Google Scholar]

- Balota DA, Cortese MJ, Sergent-Marshall SD, Spieler DH, & Yap M (2004). Visual word recognition of single-syllable words. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 133(2), 283–316.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird H, Lambon Ralph M. A., Patterson K, & Hodges JR (2000). The rise and fall of frequency and imageability: Noun and verb production in semantic dementia. Brain and language, 73(1), 17–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondi MW, Edmonds EC, Jak AJ, Clark LR, Delano-Wood L, McDonald CR, Galasko D (2014). Neuropsychological criteria for mild cognitive impairment improves diagnostic precision, biomarker associations, and progression rates. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 42(1), 275–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondi MW, Salmon DP, Monsch AU, Galasko D, Butters N, Klauber MR, & Thal LJ (1995). Episodic memory changes are associated with the APOE-epsilon 4 allele in nondemented older adults. Neurology, 45, 2203–2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brysbaert M, & New B (2009). Moving beyond Kucera and Francis: A critical evaluation of current word frequency norms and the introduction of a new and improved word frequency measure for American English. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 977–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butters N, Granholm E, Salmon DP, Grant I, & Wolfe J (1987). Episodic and semantic memory: A comparison of amnesic and demented patients. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 9(5), 479–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Census Bureau US (2001). Census 2000 Summary File 1. United States Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Ratcliff G, Belle S, Cauley JA, DeKosky S, & Ganguli M (2001). Patterns of cognitive decline in presymptomatic Alzheimer disease. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58, 853–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarnette RM, Almeida OP, Forstl H, Paton A, & Martins RN (2001). Clinical characteristics of individuals with subjective memory loss in Western Australia: results from a cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(2), 168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, Pericak-Vance MA (1993). Gene dose of Apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science, 261, 921–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudas R, Clague F, Thompson S, Graham KS, & Hodges J (2005). Episodic and semantic memory in mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychologia, 43(9), 1266–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias MF, Beiser A, Wolf PA, Au R, White RF, & D’agostino RB (2000). The preclinical phase of Alzheimer disease: a 22-year prospective study of the Framingham Cohort. Archives of Neurology, 57(6), 808–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng N, Vonk JMJ, Salzberger M, & Yoo N (in press). A cross-linguistic comparison of category and letter fluency: Mandarin and English. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DA, Beckett LA, Field TS, Feng L, Albert MS, Bennett DA, Mayeux R (1997).Apolipoprotein E ϵ4 and incidence of Alzheimer disease in a community population of older persons. Jama, 277(10), 822–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, Hyman B, Kukull WA, Mayeux R, van Duijn CM (1997). Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer Disease Meta Analysis Consortium. Jama, 278(16), 1349–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladsjo JA, Evans JD, Schuman CC, Peavy GM, Miller SW, & Heaton RK (1999). Norms for letter and category fluency: demographic corrections for age, education, and ethnicity. Assessment, 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff-Radford NR, Green RC, Go RCP, Hutton ML, Edeki T, Bachman D, Farrer LA (2002). Association Between Apolipoprotein E Genotype and Alzheimer Disease in African American Subjects. Archives of Neurology, 59, 594–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JL, Brickman AM, Lang R, Byrd GS, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA, & Manly JJ (2014). Relationship between depressive symptoms and cognition in older, non-demented African Americans. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 20(7), 756–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrie HC, Hall KS, Hui S, Unverzagt FW, Yu CE, Lahiri DK, Class CA (1995).Apolipoprotein E genotypes and Alzheimer’s disease in a community study of elderly African Americans. Annals of Neurology, 37, 118–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hixson JE, & Vernier DT (1990). Restriction isotyping of human apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and cleavage with HhaI. Journal of lipid research, 31(3), 545–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honig LS, Schupf N, Lee JH, Tang MX, & Mayeux R (2006). Shorter telomeres are associated with mortality in those with APOE epsilon4 and dementia. Annals of Neurology.60(2):181–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Aisen PS, Weigand SD. Update on hypothetical model of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Lancet Neurology, 12(2), 207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Selfridge MT, Zalewski C, & Aboudarham J-F (1998). The relationship between ethnicity and word fluency. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 13(3), 319–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joubert S, Brambati SM, Ansado J, Barbeau EJ, Felician O, Didic M, Kergoat M-J (2010). The cognitive and neural expression of semantic memory impairment in mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia, 48(4), 978–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremin H, Perrier D, De Wilde M, Dordain M, Le Bayon A, Gatignol P, Arabia C (2001).Factors predicting success in picture naming in Alzheimer’s disease and primary progressive aphasia. Brain and cognition, 46(1), 180–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucera H, & Francis WN (1982). Frequency analysis of English usage: Lexicon and grammar. [Google Scholar]

- Logue MW, Schu M, Vardarajan BN, Buros J, Green RC, Go RC, Borenstein A (2011). A comprehensive genetic association study of Alzheimer disease in African Americans. Archives of Neurology, 68(12), 1569–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Jacobs DM, Sano M, Bell K, Merchant CA, Small SA, & Stern Y (1998). Cognitive test performance among nondemented elderly African Americans and Whites. Neurology, 50, 1238–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Jacobs DM, Touradji P, Small SA, & Stern Y (2002). Reading level attenuates differences in neuropsychological test performance between African American and White elders. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 8(3), 341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Kawas CH, Phelps CH (2011). The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 7(3), 263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier IB, Manly JJ, Provenzano FA, Louie KS, Wasserman BT, Griffith EY, Brickman AM (2012). White matter predictors of cognitive functioning in older adults. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 18(3), 414–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milberg WP, Hebben N, Kaplan E, Grant I, & Adams K (2009). The Boston process approach to neuropsychological assessment. Neuropsychological assessment of neuropsychiatric and neuromedical disorders, 42–65. [Google Scholar]

- Monsch AU, Bondi MW, Butters N, Salmon DP, Katzman R, & Thal LJ (1992). Comparisons of verbal fluency tasks in the detection of dementia of the Alzheimer type. Archives of Neurology, 49(12), 1253–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy KJ, Rich JB, & Troyer AK (2006). Verbal fluency patterns in amnestic mild cognitive impairment are characteristic of Alzheimer’s type dementia. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 12(4), 570–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp KV, Mormino EC, Amariglio RE, Munro C, Dagley A, Schultz AP, Rentz DM (2016). Biomarker validation of a decline in semantic processing in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology, 30(5), 624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp KV, Rentz DM, Orlovsky I, Sperling RA, & Mormino EC (2017). Optimizing the preclinical Alzheimer’s cognitive composite with semantic processing: The PACC5. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, 3(4), 668–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Kokmen E, & Tangalos EG (1994). Memory function in very early Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology, 44(5), 867–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price SE, Kinsella GJ, Ong B, Storey E, Mullaly E, Phillips M, Perre D (2012). Semantic verbal fluency strategies in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychology, 26(4), 490–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan KB, Wilson RS, Weuve J, Barnes LL, & Evans DA (2015). Cognitive impairment 18 years before clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease dementia. Neurology, 85(10), 898–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitz C, Jun G, Naj A, Rajbhandary R, Vardarajan BN, Wang L-S, Graff-Radford NR (2013). Variants in the ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABCA7), apolipoprotein E ϵ4, and the risk of late-onset Alzheimer disease in African Americans. Jama, 309(14), 1483–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha N, Berg CN, Tustison NJ, Shaw A, Hill D, Yassa MA, & Gluck MA (2018). APOE ε4 Status in Healthy Older African Americans is Associated with Deficits in Pattern Separation and Hippocampal Hyperactivation. Neurobiology of aging. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder PJ, Kahle-Wrobleski K, Brannan S, Miller DS, Schindler RJ, DeSanti S, Chandler J Assessing cognition and function in Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials: do we have the right tools? Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 10(6), 853–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Montine TJ (2011). Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 7(3), 280–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang MX, Maestre G, Tsai WY, Liu XH, Feng L, Chung WY, Mayeux R (1996). Relative risk of Alzheimer’s disease and age-at-onset distributions, based on APOE genotypes among elderly African-Americans, Caucasians, and Hispanics in New York City. Am J Hum Genet, 58, 574–584. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang MX, Stern Y, Marder K, Bell K, Gurland B, Lantigua R, Mayeux R (1998). The APOE- epsilon4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer disease among African Americans, whites, and Hispanics. Jama, 279(10), 751–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troyer AK, Moscovitch M, Winocur G, Leach L, & Freedman M (1998). Clustering and switching on verbal fluency tests in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 4(2), 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS (1993). Wide Range Achievement Test 3-Administration Manual. Wilmington, DE: Jastak Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]