Abstract

Adenosine deaminase acting on transfer RNA (ADAT) is an essential eukaryotic enzyme that catalyzes the deamination of adenosine to inosine at the first position of tRNA anticodons. Mammalian ADATs modify eight different tRNAs, having increased their substrate range from a bacterial ancestor that likely deaminated exclusively tRNAArg. Here we investigate the recognition mechanisms of tRNAArg and tRNAAla by human ADAT to shed light on the process of substrate expansion that took place during the evolution of the enzyme. We show that tRNA recognition by human ADAT does not depend on conserved identity elements, but on the overall structural features of tRNA. We find that ancestral-like interactions are conserved for tRNAArg, while eukaryote-specific substrates use alternative mechanisms. These recognition studies show that human ADAT can be inhibited by tRNA fragments in vitro, including naturally occurring fragments involved in important regulatory pathways.

Keywords: ADAT, deaminase, tRNA, adenosine, inosine, tRF

INTRODUCTION

Transfer RNAs (tRNAs) act as adaptors to decode messenger RNAs (mRNAs) into proteins. tRNAs are the most abundant small noncoding RNA molecules, constituting 4%–10% of all cellular RNA (Kirchner and Ignatova 2015). They are generally 70–90 nucleotides (nt) in length and fold into a cloverleaf secondary structure, and L-shaped three-dimensional structure (Holley et al. 1965). All tRNAs share common structural features, but contain distinctive identity elements to selectively interact with their biological partners, such as aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and tRNA modification enzymes (Giegé et al. 1993, 2012).

tRNAs need to be highly post-transcriptionally modified to be fully active. There are almost 10 times more modified nucleotides in tRNA (with around 17% of modified residues) than in other abundant RNAs in the cell (the average of modified residues is 1%–2%). Over a hundred chemically distinct nucleotides have been identified in tRNAs (Jackman and Alfonzo 2013). The type and number of modifications can vary between different tRNAs, and even among similar isoacceptors. tRNA modifications generally can play two distinct roles: contributing to structural integrity, or improving interactions with molecular partners (e.g., codon–anticodon interactions at the decoding center of the ribosome) (Giegé and Lapointe 2009; El Yacoubi et al. 2012; Piñeyro et al. 2014; Torres et al. 2014).

Inosine at the first position of the tRNA anticodon (position 34, wobble position) (I34) is one of the few essential post-transcriptional modifications on tRNAs, and results from the deamination of adenosine (A34) (Gerber and Keller 1999; Wolf et al. 2002; Tsutsumi et al. 2007; Zhou et al. 2014; Torres et al. 2015). I34 allows the recognition of three different nucleotides: cytidine (C), uridine (U), and adenosine (A) at the third position of codons, thus increasing the decoding capacity of tRNAs (Crick 1966; Piñeyro et al. 2014). As a result, I34 modifies the tRNA pool available for each codon, and accounting for this effect reveals an otherwise hidden correlation of codon usage with tRNA gene copy number in mammals (Novoa et al. 2012). It has been proposed that I34 improves translation fidelity and efficiency (Schaub and Keller 2002; Novoa et al. 2012), especially for mRNAs enriched in codons translated by I34-tRNAs (Rafels-Ybern et al. 2015, 2018a).

A-to-I conversion at position 34 of tRNAs is found in Bacteria and Eukarya, but not in Archaea (Gerber and Keller 1999; Rubio et al. 2007; Tsutsumi et al. 2007; Piñeyro et al. 2014; Zhou et al. 2014). This reaction is catalyzed by the homodimeric tRNA adenosine deaminase A (TadA) in bacteria (Wolf et al. 2002), and by the heterodimeric adenosine deaminase acting on transfer RNA (ADAT) in eukaryotes (Gerber and Keller 1999; Piñeyro et al. 2014; Torres et al. 2015). In silico analysis indicate that ADAT evolved from TadA through a duplication of the bacterial gene that eventually gave rise to the two distinct subunits of the eukaryotic enzyme (ADAT2 and ADAT3) (Gerber and Keller 1999). Both TadA and the two ADAT subunits contain a cytidine deaminase (CDA)-like domain that forms the catalytic center (Gerber and Keller 1999; Spears et al. 2011). However, the absence of a catalytic glutamate in ADAT3 indicates that ADAT2 is the catalytic subunit of the enzyme, while ADAT3 has a role in tRNA substrate recognition. Nevertheless, both subunits have been shown to be essential for catalysis (Gerber and Keller 1999). Welin and coworkers reported the crystal structure of a human ADAT2-ADAT2 homodimer (Structural Genomics Consortium; PDB ID: 3DH1), but no structure for the heterodimeric form of ADAT has been resolved to date.

The bacterial ancestor of ADAT, TadA, deaminates A34 exclusively in tRNAArgACG (Wolf et al. 2002). During the process of gene duplication and divergence that gave rise to ADAT in eukaryotes an expansion in tRNA substrates for I34 modification ensued to include all (Rafels-Ybern et al. 2018b) tRNAs acting in three-, four-, and six-box codon sets (with the exception of tRNAGly) (Grosjean et al. 2010; Saint-Léger et al. 2016). Human ADAT is able to modify eight tRNAs, namely: tRNAThrAGU, tRNAAlaAGC, tRNAProAGG, tRNASerAGA, tRNALeuAAG, tRNAIleAAU, tRNAValAAC, and tRNAArgACG (Torres et al. 2015; Chan and Lowe 2016).

The emergence of ADAT and the expansion of I34 in the eukaryotic tRNAome correlates with an increase in A34-tRNA genes. In contrast, bacterial genomes predominantly use G34-tRNAs, except for tRNAArgACG (the only substrate of TadA). On this basis, ADAT activity might have promoted the transition of eukaryotic genomes toward an enrichment in A34-tRNA genes (Novoa et al. 2012). Interestingly, this process of expansion did not extend to tRNAGly genes, and tRNAGlyACC is absent in eukaryotes. We have shown that the stability of the tRNAGly anticodon loop is impaired by the presence of an adenosine at position 34, a fact that prevents the deamination of tRNAGlyACC by ADAT and thus can explain why genes coding for A34-tRNAGly were not selected in eukaryotic genomes (Saint-Léger et al. 2016).

The process of I34-tRNA expansion in eukaryotes must have been accompanied by the development of new recognition mechanisms between the emerging A34-tRNAs and ADAT. In bacteria, the recognition of tRNAArgACG by TadA is strongly dependent on interactions of the enzyme with the anticodon arm. TadA is able to deaminate a small RNA recapitulating the anticodon stem–loop of tRNAArgACG as efficiently as the full-length tRNA (Wolf et al. 2002). In contrast, structural and biochemical studies have concluded that the activity of yeast ADAT depends on overall tRNA architecture, and its alteration results in loss of deamination (Auxilien et al. 1996; Elias and Huang 2005). In agreement with these observations it has been reported that human ADAT activity is abolished by a single base deletion that changes the conformation of tRNAVal (Achsel and Gross 1993).

ADAT has been shown to modify both mature and immature forms of tRNAs, indicating that unprocessed tRNAs can be recognized by ADAT (Auxilien et al. 1996; Torres et al. 2015), and that 5′-leader and 3′-trailer sequences (absent in mature tRNAs) are not required for this activity (Torres et al. 2015). Computational docking models suggest that the carboxy-terminal region of ADAT2 and the amino-terminal domain of ADAT3 (both missing in TadA) generate a tRNA binding surface in regions other than the anticodon stem–loop (Elias and Huang 2005). It has been shown that a positively charged motif in the carboxy-terminal region of T. brucei ADAT2 is essential for tRNA recognition. This motif is strongly conserved across eukaryotic ADAT2 sequences but is absent in TadA, suggesting that its role in tRNA recognition is a functional addition to the eukaryotic enzyme (Ragone et al. 2011).

The mechanisms involved in the evolution of new tRNA identities remain a matter of debate (Koonin 2017; Ribas de Pouplana et al. 2017). In this regard, the case of the expansion of A34-tRNAs in eukaryotes is paradigmatic, and can provide information on the requirements for the evolution of new tRNA identities. Did eukaryotic ADATs conserve the recognition mechanisms used by TadA? Which new mechanisms did they evolve to recognize the new set of A34-containing eukaryotic tRNAs? Did they retain the mechanism for tRNAArg recognition and adopted new strategies to recognize the rest of their new substrates? Our results indicate that the emergence of new ADAT substrates required the development of new recognition modes. Here we characterize the structural requirements for substrate recognition by human ADAT. We reveal differences in the interaction modes of the enzyme with tRNAArg and tRNAAla that are possibly caused by the emergence of new interactions that allowed ADAT to recognize a wider range of substrates than its bacterial ancestor TadA.

The increased range of tRNAs bound by ADAT also raises the possibility for interactions with other tRNA-related species. tRNA-derived fragments (tRFs) are short noncoding RNAs generated by specific and regulated cleavage of tRNAs. In humans, angiogenin (ANG) cleaves mature cytoplasmic tRNAAla and tRNACys to generate tRNA-derived stress-induced RNAs (Thompson et al. 2008; Thompson and Parker 2009). This activity has been associated to stress granule formation (Emara et al. 2010), inhibition of translation (Ivanov et al. 2011; Sobala and Hutvagner 2013), and expression regulation (Haussecker et al. 2010; Burroughs et al. 2011; Li et al. 2012; Maute et al. 2013; Shigematsu and Kirino 2015). However, the specific functions for most tRFs remain poorly understood. Here we report that tRFs derived from ADAT substrates can inhibit its activity in vitro.

RESULTS

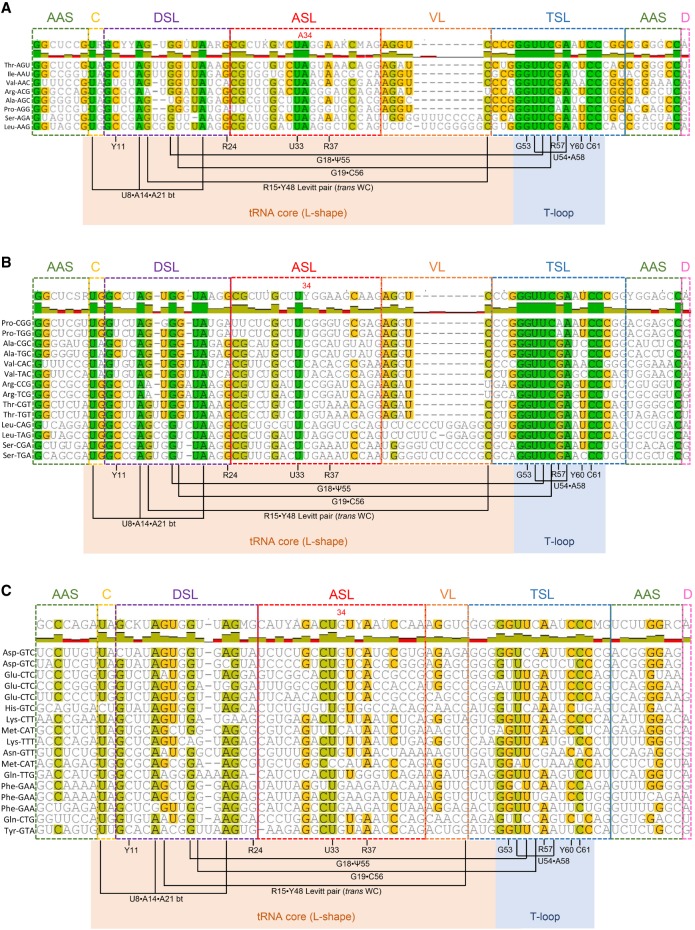

Human ADAT substrates do not share a sequence identity determinant

Although previous analyses have indicated that deamination of tRNA substrates in bacteria and yeast predominatly rely on the recognition of structural elements, we explored the possibility that tRNA recogntion by human ADAT might rely on primary sequence motifs shared by all human ADAT substrate tRNAs. Multiple sequence alignments of the eight ADAT substrates were compared to those of non-ADAT substrates (Fig. 1; Supplemental Figs. S1–S3). No differences in conserved and semiconserved residues were observed in T, A, P, S, L, I, V, and R tRNA isoacceptors between ADAT substrates (with A34) (Fig. 1A) and non-ADAT substrates (with C34 or U34) (Fig. 1B), as well as for non-T, A, P, S, L, I, V, R non-ADAT substrate tRNAs (Fig. 1C). Moreover, most conserved residues corresponded to positions known to be essential for tRNA secondary and tertiary structure. The absence of a nucleotide signature exclusive to ADAT substrates indicates that recognition might depend on the presence of A34, on tRNA-specific identity elements, or, as previously proposed, on three-dimensional features of the substrates (Auxilien et al. 1996; Elias and Huang 2005).

FIGURE 1.

Sequence alignment of a representative set of human tRNAs including ADAT substrates (A) and non-ADAT substrates (B,C). The cognate amino acid and anticodon for each tRNA are specified. Secondary structural motifs are indicated. AAS stands for amino acid acceptor stem (green); (C) connector between AAS and DSL (yellow); (DSL) D-stem–loop (or D-arm) (purple); (ASL) anticodon stem–loop (or anticodon arm) (red); (VL) variable loop (orange); (TSL) T-stem–loop (or T-arm) (blue); and (D) discriminator nucleotide (pink). Conserved and semiconserved residues are color-coded: green for 100% similar; light green for 80% to 100% similar; yellow for 60% to 80% similar; and white for <60% similar. Structure-based relationships between conserved and semiconserved nucleotides that control the 3D-structure formation are indicated. R stands for purine; Y for pyrimidine; and bt for base triple. Interactions in the 3D core of the tRNA for L-shape formation have an orange background, and interactions for T-loop formation have a blue background. (A) The most abundant isodecoder sequence of each of the eight human tRNAs substrates of ADAT is represented. (B,C) Representative sets of non-ADAT substrate tRNAs encoding for T, A, P, S, L, I, V, R (B) and the rest of amino acids (C).

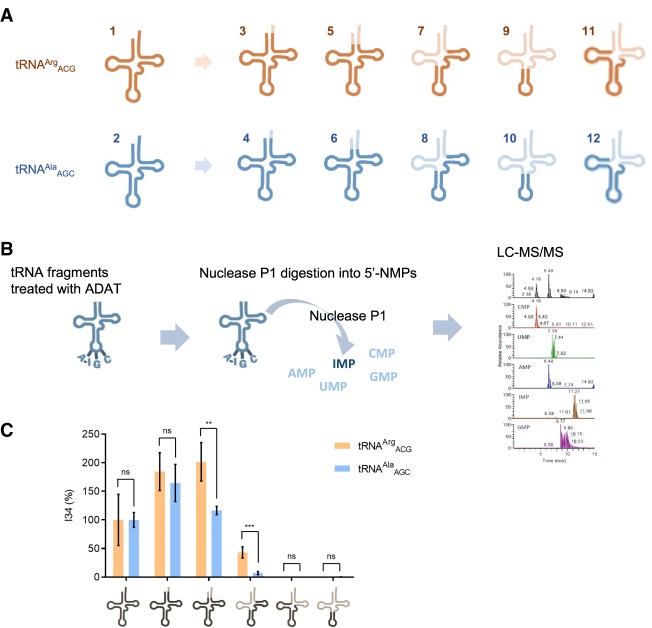

Shortened variants of tRNAArg and tRNAAla are not equally deaminated

Because ADAT evolved from TadA, and tRNAArgACG is a common substrate of both enzymes, we asked whether tRNA recognition mechanisms may be shared by both enzymes and used by ADAT in all its substrates. Thus, we examined ADAT-mediated deamination of several tRNA mini-substrates derived from human tRNAArgACG and tRNAAlaAGC, respectively. All tested tRNA fragments preserved the anticodon stem–loop of the original tRNA (Fig. 2A; Supplemental Fig. S4).

FIGURE 2.

ADAT-mediated deamination of RNA fragments derived from tRNAArgACG and tRNAAlaAGC. (A) Schematic representation of the human tRNAArgACG and tRNAAlaAGC fragments analyzed: a tRNA lacking the 3′ CCA (which is added during the maturation of tRNAs at the 3′-end), a tRNA lacking the acceptor stem, a fragment with the T-arm and the anticodon arm, and the anticodon stem–loop. (B) Workflow of the assay used to detect I34 modification in the tRNA fragments by liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LC-MS). C Levels of I34-modification of tRNAAlaAGC fragments after 1 h incubation (light blue) and overnight incubation (blue) with human ADAT. All deamination reactions were done in triplicate and averaged; the error bars reflect the standard deviation. Asterisks indicate statistical significance between samples: (ns) not significant with P-value >0.05; (*) significant with P-value ≤0.05; (**) very significant with P-value ≤0.01; (***) extremely significant with P-value ≤0.001; (****) extremely significant with P-value ≤0.0001. (C) Levels of I34-modification of tRNAArgACG (orange) and tRNAAlaAGC (blue) fragments after overnight incubation with human ADAT. All deamination reactions were done in triplicate and averaged; the error bars reflect the standard deviation. Asterisks indicate statistical significance between samples.

Since it was not possible to detect tRNA fragments by the RFLP method (Wolf et al. 2002) (the shortest fragments cannot be PCR-amplified), I34 levels were analyzed by LC-MS (McCoy et al. 2014; Su et al. 2014). For this, reaction products were purified, digested into 5′-nucleotides monophosphate (NMPs), and analyzed by LC-MS (Fig. 2B). We determined the conditions required for deamination of tRNAAlaAGC and tRNAArgACG (transcripts 1 and 2, Supplemental Table S2). Under the same conditions, variants of both tRNAs lacking the 3′ CCA end (transcripts 3 and 4, Supplemental Table S2) were fully and equally deaminated, while the rest of the substrates were partially modified. Complete deletion of the acceptor stem affected deamination of tRNAAlaAGC more than tRNAArgACG (transcripts 5 and 6, Supplemental Table S2), and this difference was increased by the deletion of the acceptor stem and D-loop (transcripts 7 and 8, Supplemental Table S2). Fragments of the tRNA bearing the D-loop and the anticodon, or only the anticodon stem–loop of both tRNAArgACG and tRNAAlaAGC (transcripts 9 and 10, Supplemental Table S2) were not active substrates. Thus, while the recognition by human ADAT of both tRNAArgACG and tRNAAlaAGC extends beyond the anticodon stem–loop into the T-loop, interactions with the acceptor stem and D-loop are more important for the deamination of tRNAAlaAGC (Fig. 2C; Supplemental Fig. S5).

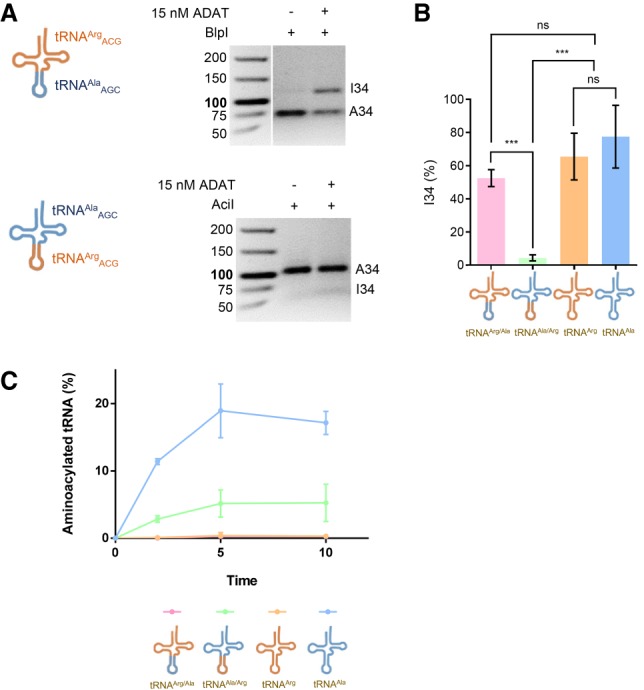

To explore the possibility that individual identity elements located in the aminoacylation half of the tRNA molecule contribute to the recognition of tRNAAlaAGC, while tRNAArgACG recognition may be more focused on interactions with the anticodon stem–loop, we designed two chimeric tRNAs: a tRNAArgACG bearing tRNAAlaAGC anticodon arm and a tRNAAlaAGC with tRNAArgACG anticodon arm (Supplemental Fig. S6). Using the RFLP method we analyzed the deamination activities of the two chimeric tRNAs and compared them to the deamination of the native ADAT substrates (Fig. 3A). Unexpectedly, the deamination results revealed that only the first chimera (tRNAArgACG with tRNAAlaAGC anticodon arm) had deamination levels comparable to those for the native substrates (Fig. 3B). On the contrary, a tRNAAlaAGC with tRNAArgACG anticodon arm showed extremely low levels of deamination (4.4 ± 1.8%). We tested the ability of this second chimera to be aminoacylated by human alanyl-tRNA synthetase (AlaRS), which relies solely on acceptor stem interactions with the G3:U70 base pair to fully aminoacylate tRNAs (Hou and Schimmel 1988). We found that a tRNAAlaAGC with tRNAArgACG anticodon arm is a poor substrate for AlaRS aminoacylation, suggesting that this chimeric tRNA presents a distorted three-dimensional structure that interferes with the recognition of the acceptor stem by AlaRS (Fig. 3C). These results indicate that deamination of tRNA by ADAT does not require specific sequence motifs, but rather an adequate three-dimensional structure of the substrate.

FIGURE 3.

ADAT-mediated deamination of chimeric tRNAs. (A, left panel) Schematic representation of the two chimeric tRNAs: tRNAArgACG with tRNAAlaAGC anticodon arm (upper panel) and tRNAAlaAGC with tRNAArgACG anticodon arm (lower panel). (Right panel) Representative RFLP experiment to assess ADAT-mediated deamination of the two chimeric tRNAs. (B) Levels of I34-modification from three independent experiments as in A compared to I34-levels in two native ADAT substrates: tRNAArgACG and tRNAAlaAGC, in the same reaction conditions. All deamination reactions were done in triplicate and averaged; the error bars reflect the standard deviation. (C) Aminoacylation assays of the chimeric tRNAs used in this work by human AlaRS, with wild-type tRNAArgACG, and tRNAAlaAGC used as controls. Substrates are depicted accordingly. Full incorporation of radioactive alanine was monitored as described. All deamination reactions were done in triplicate and averaged; the error bars reflect the standard deviation.

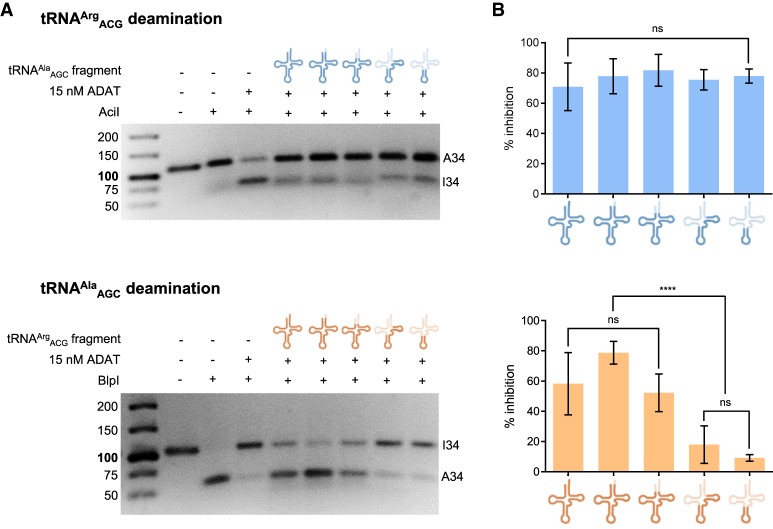

The substrate recognition mode of ADAT varies between different tRNAs

We then performed inhibition assays of ADAT-dependent deamination using tRNA fragments, to determine if the mode of tRNA recognition by ADAT is equivalent between human tRNAArgACG and tRNAAlaAGC. Using the RFLP method (Wulff et al. 2017) we examined I34 formation in tRNAArgACG (3 µM) in the presence of 50 µM tRNAAlaAGC fragments, and vice versa (Fig. 4). All tRNAAlaAGC fragments strongly inhibited tRNAArgACG deamination. In contrast, only the longest tRNAArgACG fragments could inhibit tRNAAlaAGC deamination. This indicates that the recognition mechanisms of ADAT vary from substrate to substrate. The recognition of tRNAArgACG by ADAT appears to be dependent on interactions with the anticodon stem–loop, which can be inhibited by any tRNA fragment harboring a similar structure. On the other hand, tRNAAlaAGC is recognized through additional regions in the tRNA molecule, and its deamination of tRNAAlaAGC can only be prevented by targeting these interactions with longer tRNA fragments.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of human tRNA fragments on ADAT-mediated deamination of human tRNAArgACG and tRNAAlaAGC. (A) Representative RFLP experiments to assess ADAT-mediated deamination of tRNAArgACG in the presence of 50 µM tRNAAlaAGC fragments (upper panel) and tRNAAlaAGC in the presence of 50 µM tRNAArgACG fragments (lower panel). (B) Percentage of inhibition caused by the tRNA fragments calculated from three independent experiments. All deamination reactions were done in triplicate and averaged. Error bars reflect the standard deviation. No statistical differences were observed between different tRNA fragments (P-value = 0.6814).

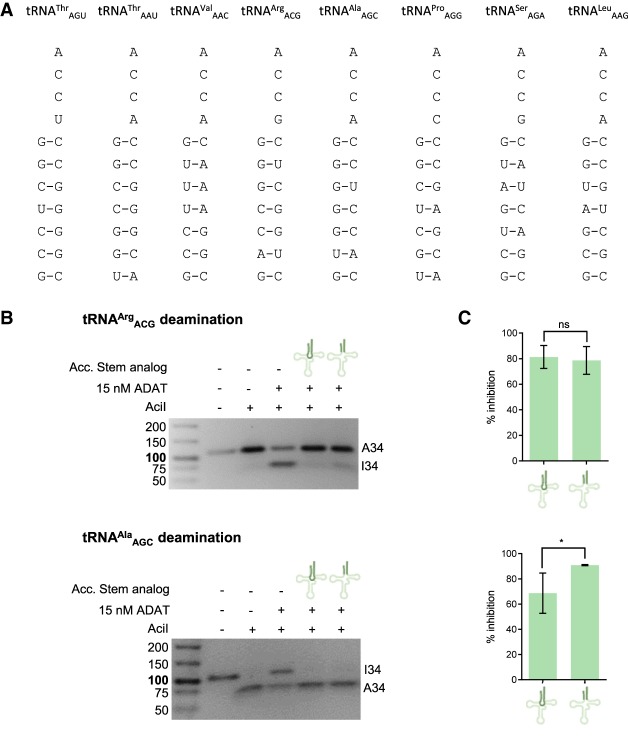

Once we had established that tRNA recognition by ADAT varies from substrate to substrate we explored whether the deamination of tRNAArgACG could be prevented by disturbances in the binding of the acceptor stem. For this, we constructed two different analogs of tRNAProAGG acceptor stem (Fig. 5A) and we examined their ability to inhibit I34 formation in tRNAArgACG and tRNAAlaAGC (Fig. 5; Supplemental Fig. S7). The length of these analogs, and the presence of an unpaired CCA sequence, gave us confidence that these molecules would preferentially bind to the site of acceptor-stem recognition in ADAT. The deamination of both tRNAs was equally inhibited by the acceptor stem analogs (80% of inhibition). The fact that productive deamination of both tRNAArgACG and tRNAAlaAGC is prevented by an acceptor stem-like structure suggests that ADAT requires a strict positioning of its tRNA substrates, independently of the recognition mode (Figs. 4, 5).

FIGURE 5.

Effect of human tRNAProAGG acceptor stem analogs on ADAT-mediated deamination. (A) Schematic representation of representative acceptor stem sequences of all human ADAT tRNA substrates. (B) Representative RFLP experiments to assess ADAT-mediated deamination of tRNAArgACG (upper panel) and tRNAAlaAGC (lower panel) upon addition of 50 µM of tRNAProAGG acceptor stem analogs (with and without loop). (C) Percentage of inhibition caused by acceptor stem analogs on tRNAArgACG (upper panel) and tRNAAlaAGC (lower panel) deamination calculated from three independent experiments. All deamination reactions were done in triplicate and averaged; the error bars reflect the standard deviation.

Human tRFs derived from ADAT substrates can inhibit ADAT

The observation that tRNA fragments can inhibit ADAT prompted us to investigate the possibility that naturally occurring tRNA-derived fragments (tRFs) may be able to inhibit the activity of the enzyme. tRFs are classified according to the cleavage site in the tRNA molecule: tRNA halves (including 5′-halves and 3′-halves), 5′-tRFs, 3′-tRFs, and internal-tRFs (i-tRFs). tRNA halves are produced after cleavage in the anticodon loop, 5′-tRFs and 3′-tRFs after cleavage in the D-loop and T-loop, respectively, and i-tRFs are generated through a combination of cleavages in the anticodon loop and either D-loop or T-loop (Pliatsika et al. 2016).

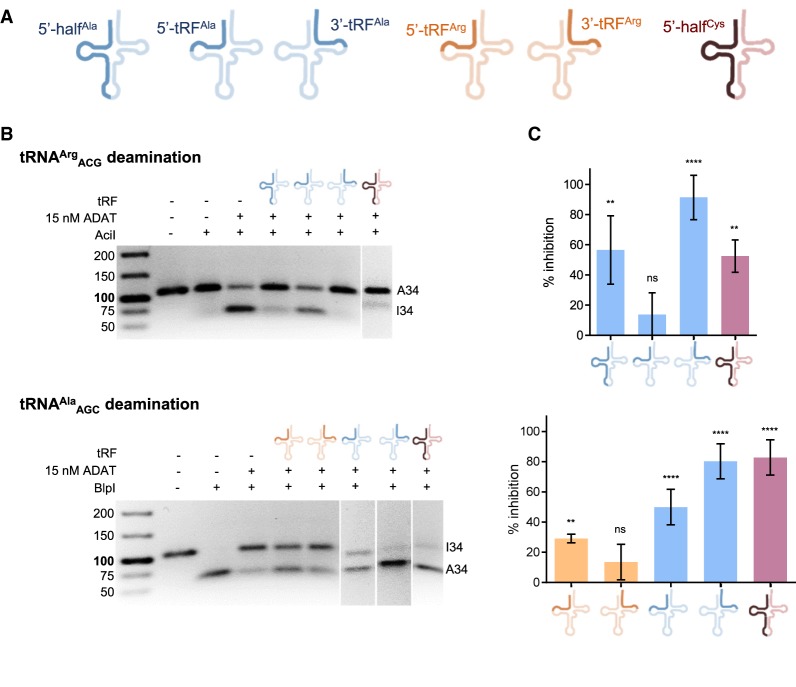

We searched for the most abundant tRFs in human cells reported at MINTbase (Pliatsika et al. 2016, 2018), and selected six species: two derived from tRNAArgACG, three from tRNAAlaAGC, and one from tRNACysGCA (Fig. 6A). We analyzed the inhibitory effect of 50 μM of each tRF upon ADAT-mediated deamination of tRNAArgACG and tRNAAlaAGC. The 5′-half and 3′-tRF derived from tRNAAlaAGC, and the 5′-half derived from tRNACysGCA significantly inhibited the deamination of tRNAArgACG. On the other hand, deamination of tRNAAlaAGC was inhibited by the 5′-tRF and 3′-tRF derived from tRNAAlaAGC and the 5′-half derived from tRNACysGCA (Fig. 6B,C).

FIGURE 6.

Effect of human tRFs on ADAT-mediated deamination of human tRNAArgACG and tRNAAlaAGC. (A) Schematic representation of the human tRFs analyzed: a 5′-tRF and a 3′-tRF derived from tRNAArgACG; a 5′-half, a 5′-tRF, and a 3′-tRF derived from tRNAAlaAGC; and a 5′-half derived from tRNACysGCA. (B) Representative RFLP experiment to assess ADAT-mediated deamination of tRNAArgACG (upper panel) and tRNAAlaAGC (lower panel) upon addition of 50 µM human tRFs. (C) Percentage of inhibition of ADAT-mediated deamination of tRNAArgACG (upper panel) and tRNAAlaAGC (lower panel) caused by tRFs calculated from three independent experiments as in B and averaged. Error bars reflect the standard deviation.

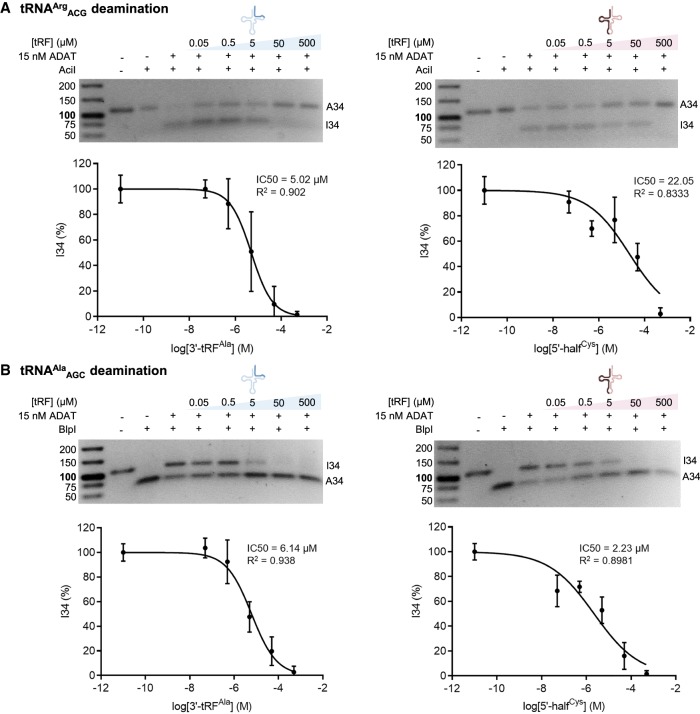

To further characterize ADAT inhibition by the tRFs, we built dose-response curves of the tRFs that exhibited the highest inhibitory activity and estimated the corresponding half maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50 values) (Fig. 7; Supplemental Fig. S8). The highest inhibition of tRNAArgACG (and lowest IC50 value) was observed with the 3′-tRF derived from tRNAAlaAGC, while tRNAAlaAGC deamination was best inhibited by the 5′-half derived from tRNACysGCA. It should be noted that the lack of sequence complementarity excludes the formal possibility that the inhibitory effect measured in these last experiments may be due to annealing of the two RNA molecules involved in the assays.

FIGURE 7.

Inhibition constants of human tRFs upon ADAT deamination of human tRNAArgACG (A) and tRNAAlaAGC (B). (Upper panels) Representative RFLP experiments. (Lower panels) Percentage of I34 modification upon varying concentrations of tRFs from three independent experiments and averaged. Error bars reflect the standard deviation. IC50 values are indicated.

DISCUSSION

The process of substrate expansion that accompanied the evolution of bacterial TadA into eukaryotic ADAT represents an unusual case of emergence of new tRNA identities that resulted in a complete overhaul of the tRNA gene content of eukaryotic genomes (Novoa et al. 2012). The mechanisms involved in the growth of the ADAT substrate set are relevant to our understanding of the evolution of tRNA identities. For example, it is unclear whether the ability to deaminate A34-tRNAs cognate for eight different amino acids was already present in the bacterial enzyme, or whether such expansion necessitated the incorporation of new recognition mechanisms. On the other hand, it is unclear whether this evolution eventually overrode ancestral identity elements of bacterial tRNAArg, or if the bacterial recognition mode was kept in the eukaryotic system.

Previous reports have demonstrated that tRNA deamination by TadA and yeast ADAT do not rely on the primary sequence but on a proper distribution of structural elements in the tRNA architecture (Auxilien et al. 1996; Elias and Huang 2005). Despite the large evolutionary distance, and the fact that the total number of substrates varies from yeast to human ADAT, sequence alignments of human tRNAs also failed to identify the presence of signature sequences shared between human ADAT substrates (Fig. 1; Supplemental Figs. S1–S3).

To investigate the distribution of interactions between ADAT and its substrates we designed a series of short tRNA variants derived from human tRNAArg and tRNAAla and checked for ADAT-mediated deamination (Fig. 2). tRNAs lacking the 3′ CCA were fully deaminated upon incubation with ADAT, consistent with the observation that precursor tRNAs have all the requirements for efficient deamination (Torres et al. 2015). Interestingly, we observed a significant decrease in the levels of deamination of tRNAAla with respect to tRNAArg when the acceptor stem was removed, an effect exacerbated by the absence of the D-arm (Fig. 2C). RNA molecules recapitulating the anticodon stem–loop alone, or in combination with the D-loop were not substrates for deamination. This suggests that the deamination of tRNAArg by ADAT is less dependent on acceptor stem and D-loop interactions than the same reaction performed on tRNAAla. However, an anticodon stem–loop mini-substrate is never sufficient for deamination, consistent with the importance of the whole tRNA structure for the recognition by ADAT (Auxilien et al. 1996; Elias and Huang 2005).

The importance of tRNA architecture over sequence-specific contacts for ADAT activity was further supported by our experiments with chimeric tRNAs (Fig. 3), which showed complete loss of deamination activity in a substrate designed to contain two regions that, individually, seemed to contribute the most to the deamination of tRNAArg and tRNAAla. Aminoacylation assays supported the possibility that a chimeric tRNA bearing a tRNAAlaAGC acceptor stem with a tRNAArgACG anticodon loop results in a distorted three-dimensional structure. Moreover, the fact that a tRNA chimera constructed using the reverse combination of fragments generated an efficient ADAT substrate again points at the general structure of the tRNA as the most important feature for ADAT activity.

We further explored this possibility through inhibition assays with different tRNA fragments (Fig. 4). Deamination of tRNAArg was inhibited by all tested tRNA fragments to a similar extent, but only the largest tRNA structures could effectively inhibit tRNAAla deamination. These results again support that the interaction of ADAT with the anticodon arm of tRNAArg is essential, while the recognition of tRNAAla by ADAT does not depend preferentially on the recognition of the anticodon domain. Thus, the recognition of tRNAArg by ADAT is reminiscent of the recognition of tRNAArg by TadA, while the recognition of tRNAAla by ADAT is less localized and takes advantage of other regions of the tRNA.

We then investigated whether blocking the binding of the tRNA acceptor stem would affect the deamination of tRNAArg and tRNAAla by ADAT (Fig. 5). Acceptor stem analogs derived from tRNAPro inhibited the deamination of both tRNAArg and tRNAAla to similar extents, suggesting that correct orientation of all substrates is required for ADAT activity. Taken together, our results indicate that deamination of tRNAArg and tRNAAla by ADAT involves the recognition of the overall tRNA structure and requires correct binding to the different domains of both tRNAs. However, differences exist in the relative importance of the different domains of the tRNA for ADAT activity. While the deamination of tRNAAla can be strongly inhibited by an acceptor stem analog but not by an anticodon stem–loop analog, the deamination of tRNAArg is strongly dependent on anticodon loop interactions (Figs. 2, 3). We propose that these different recognition mechanisms reflect the process of substrate expansion from TadA to ADAT, which involved the evolution of new interactions with new substrates, while preserving the preferential recognition of the anticodon stem–loop of tRNAArg.

The ability of tRNA fragments to inhibit ADAT activity prompted us to investigate whether human tRNA-derived fragments (tRFs) might be able to modulate ADAT activity (Fig. 6). 5′-halves derived from human tRNAAla are generated in response to stress, have been associated to induction of stress granule formation (Emara et al. 2010), and, together with 5′-halves derived from tRNACys, have been linked to translational inhibition in human cells (Ivanov et al. 2011). Additionally, 3′ CCA tRFs derived from tRNASerUGA and tRNAGlyGCC generated by Dicer cleavage have been associated to translational inhibition in human cells via Argonaute (AGO) proteins (Haussecker et al. 2010; Maute et al. 2013). The regulation of tRNA modification levels is rapidly emerging as a new layer of regulation that acts upon the translation efficiency of specific genetic programs (Blanco and Frye 2014; Gu et al. 2014; Popis et al. 2016). For example, NSun2 is a cytosine-5 tRNA methylase whose depletion increases angiogenin-mediated cleavage of tRNAs. The ensuing accumulation of tRFs silences translation rates and activates stress pathways (Schaefer et al. 2010; Blanco et al. 2014). TRM9 catalyzes the addition of the final methyl group on the modifications mcm5U and mcm5s2U, which are found at the uridine wobble base of certain tRNAs. The decrease in such tRNA modifications leads to reduced expression of key damage response proteins and ultimately enhances the susceptibility to DNA alkylation agents (Begley et al. 2007). The tRNA methylation catalyzed by Trm4 seems to be necessary for the translation of detoxification proteins and its absence causes increased sensitivity to ROS-inducing agents such as H2O2 (Chan et al. 2012).

tRFs may influence tRNA modification levels through the inhibition of modification enzymes. Studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae have shown that environmental insults are met with variations in the levels of several tRNA modifications (Chan et al. 2010; Dedon and Begley 2014). We report here that two fragments derived from tRNAAlaAGC, and a 5′-half derived from tRNACysGCA inhibit the deamination of both tRNAArgACG and tRNAAlaAGC by ADAT with IC50 values in the range of 1 to 10 µM (Fig. 7; Supplemental Fig. S7). While these inhibitory constants are modest, this interaction may become relevant under conditions of locally high tRF concentrations (Rojiani et al. 1989; Lee et al. 2004), or in pathological conditions where ADAT activity is compromised by genetic mutations. The apparent specificity in the inhibitory activity of ADAT by tRFs is currently unexplained. Possibly, tRF-specific structural motifs are responsible for the differences in inhibitory capacity.

The evolution of eukaryotic ADAT from bacterial TadA entailed the selection of a new set of interactions for tRNA recognition that were incorporated while conserving some aspects of the ancestral interaction mode of TadA and tRNAArgACG. This new set of interactions allows ADAT to interact with tRNA fragments, and these fragments have the capacity to modestly inhibit the modification of A34 to inosine. Whether this inhibitory activity plays a regulatory role in human cells deserves further investigation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Multiple tRNA sequence alignments

We obtained the hg19 human tRNA sequences from Chan and Lowe (2009). We selected a representative set of human tRNA sequences in each case, using the T-coffee software with the option +trim_n (Will et al. 2012). This option selects the best informative sequences maximizing their variability (Fig. 1). tRNA sequences were aligned using mlocarna software with default conditions (Fig. 1; Supplemental Figs. S1–S3; Notredame et al. 2000).

Expression and purification of human ADAT

The cDNA sequences of ADAT2 and ADAT3 (NM_182503.2 and NM_138422.3, respectively) were codon optimized for expression in Escherichia coli (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (Supplemental Fig. S9). Note that two different transcript isoforms of ADAT3 are currently annotated in NCBI (NM_138422.3 and NM_001329533.1). We used the short ADAT3 isoform given that the resulting protein was previously validated for in vitro activity assays (Saint-Léger et al. 2016).

ADAT2 and ADAT3 were cloned into the bicistronic vector pOPINFS (Oxford Protein Production Facility) using the In-Fusion cloning system (Clontech) with specific primers (Supplemental Table S1). The final construct encodes an amino-terminal His6-tagged ADAT2 and a carboxy-terminal StrepII-tagged ADAT3 separated by an IRES. The sequence of the construct was confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

BL21(DE3)pLysS chemically competent cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific) transformed with pOPINFS-His6-ADAT2-ADAT3-Strep were grown overnight in LB medium with 100 µg/mL ampicillin and 50 µg/mL chloramphenicol. The starting culture was diluted 1:20 in LB medium containing 100 µg/mL ampicillin, and grown at 37°C with shaking to an OD600 between 0.6 and 0.8. Protein expression was then induced with 0.5 mM of isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 37°C for 3 h with shaking. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4000g at 4°C for 20 min; the cell pellet was washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution (40 mL of PBS per 1 L of culture; centrifuged at 4000g at 4°C for 20 min) and stored at −80°C.

ADAT heterodimers were purified by Strep-tag affinity chromatography (ADAT3 is fused to Strep-tag). All procedures were done at 4°C in buffers containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Cell pellets (stored at −80°C) were resuspended in StrepTrap binding buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8), and 5 MU of bovine pancreas DNase I was added (Calbiochem). Cells were lysed with a cell disruptor (Constant Systems) at 25,000 psi twice. The cell lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 70,000g for 1 h, and the supernatant was filtered with a 0.45 µm syringe filter (Frisenette). The clarified lysate was then loaded onto a 5 mL StrepTrap HP column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The column was washed with 7 column volumes of binding buffer, and the bound protein was eluted with StrepTrap elution buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM d-Desthiobiotin, pH 8). Protein elution was monitored by measuring absorbance at 215, 260, and 280 nm. SDS-PAGE and western blot (WB) analyses were used to confirm that ADAT2 and ADAT3 copurified at an equimolar ratio. For the WB analyses purified proteins were resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Immobilion-P, Millipore) at 250 mA for 90 min at 4°C and immunoblotted with antibodies specific to Strep-tag (dil. 1:1000; ab76949, Abcam), and His-tag (dil. 1:1000; ab18184, Abcam). HRP-conjugated anti-mouse (GE Healthcare) was used as secondary antibody. Visualization was performed using ECL (GE Healthcare) in an Odyssey Fc Imager (Li-Cor). The purified heterodimeric ADAT was stored at −80°C in elution buffer with 10% glycerol. Protein concentration was determined by measuring optical absorbance at 280 nm with a NanoDrop ND-1000.

In vitro transcription of tRNAs and tRFs

All tRNAs and tRFs used in the study correspond to human sequences. The full-length variants of tRNAAlaAGC and tRNAArgACG were synthesized as previously described, using as a template for the in vitro transcription pUC19 plasmid cloned with the sequence to be transcribed (Supplemental Table S2; Torres et al. 2015). For both tRNAs, six oligonucleotides (Supplemental Table S1) annealed and cloned into pUC19 vector and digested with BstNI (for tRNAAlaAGC) or NspI (for tRNAArgACG) restriction enzymes (NEB) were used as a template. The shorter tRNA variants and the chimeric tRNAs used in the study were in vitro transcribed using synthetic DNA templates with the T7 promoter. These DNA templates are partially single stranded and only the promoter region +1 is double stranded. Fifteen nucleotides were added upstream of the promoter to increase the yield of the transcription. Whereas the top strand contains the promoter region (plus 15 upstream nucleotides) but not the template (same sequence was used for all transcripts), bottom strands contain the promoter and template sequences (they are transcript-specific) (Supplemental Tables S1, S2; Milligan et al. 1987). All tRNAs were in vitro transcribed using T7 RNA polymerase and purified according to standard protocols.

The shortest tRNA fragments (acceptor stem and the T-arm plus the anticodon arm derived from tRNAAlaAGC, the anticodon stem–loop of both tRNAArgACG and tRNAAlaAGC) and all the human tRFs, whose in vitro transcription had very low yields, were chemically synthesized (Sigma-Aldrich). The RNA sequences of all tRNAs and fragments are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

In vitro deamination assays and evaluation of inosine formation

Liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LC-MS) method

Prior to all deamination reactions, all tRNAs (including tRNA fragments) were folded by heating to 95°C for 3 min and cooling down to room temperature over 30 min. All deamination reactions were done using 50 µM of in vitro transcribed tRNA substrate in deamination buffer (50 mM Hepes-KOH, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 8) and 800 nM of purified human ADAT enzyme in a final volume of 30 µL, and incubated at 37°C during the indicated time (1 h or overnight). The RNA products were purified using the miTotal RNA Extraction Miniprep System (Viogene) kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. The tRNA was eluted from the purification column with 50 µL of nuclease-free water, and quantified by measuring absorbance at 260 nm with a NanoDrop ND-1000. tRNAs were then digested into 5′-NMPs with 100 units of Nuclease P1 from Penicillium citrinum (Sigma-Aldrich) in 30 mM ammonium acetate and 0.1 mM zinc chloride buffer, in a final volume of 60 µL at 50°C for 2 h. The 5′-NMPs were extracted using centrifugal filters with 10 kDa MWCO (Merck Millipore) following the manufacturer's protocol. IMP levels were then evaluated by LC-MS. Sample was loaded to a 2.1 × 150 mm, 5 µm, XTerra MS C18 2.1 × 150 mm; 3.5 µm (Waters Corporation) column at a flow rate of 100 µL/min using a Quaternary pump, Finnigan, Mod. Surveyor MS (Thermo Electron Corporation) and Finnigan, Mod. Micro AS (Thermo Electron Corporation) as autosampler. Compounds were separated with a 10-min run by isocratic elution at 0% B, followed by linear gradients from 0% to 75% B in 1 min and isocratic elution at 75% B in 3 min, other linear gradients from 75% to 0% B in 1 min and stabilization to initial conditions (A = H2O + 0.1% FA, B = ACN + 0.1% FA). The column outlet was directly connected to ESI source fitted on an LTQ-FT Ultra mass spectrometer (Thermo). The mass spectrometer was operated in FT wide selected ion monitoring (SIM) acquisition mode (m/z 310–370). MS scans were acquired in the FT with resolution (defined at 400 m/z) set to 100,000. Spray voltage in the ESI source voltage was set to 3.7 kV. Capillary voltage and tube lens on the LTQ-FT were tuned to −48 V and −94 V, respectively. The spectrometer was used in negative polarity mode. At least one blank run before of analysis was performed to ensure the absence of cross contamination from previous samples.

Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) method

All deamination reactions were done using 3 µM of in vitro transcribed tRNA substrate in deamination buffer and the indicated concentration of affinity-purified human ADAT enzyme (15 nM ADAT was used in all assays with tRNA fragments) in a final volume of 30 µL, and incubated at 37°C for the indicated time. The RNA products were purified using the miTotal RNA Extraction Miniprep System (Viogene) kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. The tRNA was eluted from the purification column with 30 µL of nuclease-free water, and quantified by measuring absorbance at 260 nm with a NanoDrop ND-1000. RNA was reverse transcribed with the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, catalog no. 4368814). RT of tRNA species was performed using 100 ng of in vitro transcribed tRNA as a RT template in a final reaction volume of 20 µL. Ten picomoles of specific RT primers (Supplemental Table S1) were used for each tRNA species. The RT cycle was as follows: 10 min at 25°C, 120 min at 37°C, and 5 min at 85°C. Two microliters of in vitro transcribed tRNA-derived cDNA were used for a standard 20 µL PCR. Forward and reverse primers used for PCR amplification of each target are detailed in Supplemental Table S1. The PCR cycle was as follows: 3 min at 94°C (1 cycle); 45 sec at 94°C, 30 sec at the target-specific annealing temperature (60°C, for both tRNAAlaAGC and tRNAArgACG), and 30 sec at 72°C (35 cycles); and 10 min at 72°C (one cycle). When required, PCR amplicons were purified using the NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up kit (Macherey-Nagel, catalog no. 740609.250) and sequenced using their respective forward and reverse PCR primers as sequencing primers (GATC Biotech). PCR amplicons were digested with 10 units of the appropriate restriction enzyme in 1× recommended reaction buffer, following the manufacturer's protocol. tRNAAlaAGC-derived PCR amplicons were digested with Bpu1102I (Thermo Scientific, catalog no. ER0091) in Tango buffer (Thermo Scientific) for 12 h at 37°C, and tRNAAlaAGC-derived PCR amplicons with AciI (NEB) in CutSmart buffer (NEB) for 3 h at 37°C. Digested samples were then resolved in 2% agarose gels with DNA Stain G (Serva) (run for 1.5 h at 120 V) and visualized under UV shadowing. Gel bands were quantified using ImageJ.

In vitro aminoacylation assays

Aminoacylation by Homo sapiens AlaRS of human tRNAs and the chimeras generated in this study was monitored as described above. The aminoacylation reaction conditions, quantification, and analysis were performed as previously described (Saint-Léger et al. 2016).

Statistical analyses

Curve fittings and statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism v6. Data is shown as the mean ± SD. Two-tailed unpaired nonparametric Student's t-tests and ANOVA tests were used to determine statistical significance.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Marta Vilaseca and Dr. Mireia Díaz-Lobo from the Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Core Facility (IRB Barcelona) for the MS analyses (the Facility is a member of Proteored, PRB3-ISCIII, supported by grant PRB3 [IPT17/0019 - ISCIII-SGEFI/ERDF, and of the BMBS EU COST Action BM 1403]). We also thank all members of the Gene Translation Laboratory for all helpful comments and discussions. This work was supported by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness to L.R.d.P. (BIO2015-64572-R and BIO2014-61411-EXP), M.C. (BFU2014-53550-P, BFU2017-83720-P, MDM-2014-0435), and H.R.F. (FPU14/01315).

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.068189.118.

REFERENCES

- Achsel T, Gross HJ. 1993. Identity determinants of human tRNASer: sequence elements necessary for serylation and maturation of a tRNA with a long extra arm. EMBO J 12: 3333–3338. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06003.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auxilien S, Crain PF, Trewyn RW, Grosjean H. 1996. Mechanism, specificity and general properties of the yeast enzyme catalysing the formation of inosine 34 in the anticodon of transfer RNA. J Mol Biol 262: 437–458. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begley U, Dyavaiah M, Patil A, Rooney JP, DiRenzo D, Young CM, Conklin DS, Zitomer RS, Begley TJ. 2007. Trm9-catalyzed tRNA modifications link translation to the DNA damage response. Mol Cell 28: 860–870. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco S, Frye M. 2014. Role of RNA methyltransferases in tissue renewal and pathology. Curr Opin Cell Biol 31: 1–7. 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco S, Dietmann S, Flores JV, Hussain S, Kutter C, Humphreys P, Lukk M, Lombard P, Treps L, Popis M, et al. 2014. Aberrant methylation of tRNAs links cellular stress to neuro-developmental disorders. EMBO J 33: 2020–2039. 10.15252/embj.201489282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burroughs AM, Ando Y, de Hoon MJ, Tomaru Y, Suzuki H, Hayashizaki Y, Daub CO. 2011. Deep-sequencing of human Argonaute-associated small RNAs provides insight into miRNA sorting and reveals Argonaute association with RNA fragments of diverse origin. RNA Biol 8: 158–177. 10.4161/rna.8.1.14300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan PP, Lowe TM. 2009. GtRNAdb: a database of transfer RNA genes detected in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 37: D93–D97. 10.1093/nar/gkn787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan PP, Lowe TM. 2016. GtRNAdb 2.0: an expanded database of transfer RNA genes identified in complete and draft genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 44: D184–D189. 10.1093/nar/gkv1309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CT, Dyavaiah M, DeMott MS, Taghizadeh K, Dedon PC, Begley TJ. 2010. A quantitative systems approach reveals dynamic control of tRNA modifications during cellular stress. PLoS Genet 6: e1001247 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CT, Pang YL, Deng W, Babu IR, Dyavaiah M, Begley TJ, Dedon PC. 2012. Reprogramming of tRNA modifications controls the oxidative stress response by codon-biased translation of proteins. Nat Commun 3: 937 10.1038/ncomms1938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick FH. 1966. Codon–anticodon pairing: the wobble hypothesis. J Mol Biol 19: 548–555. 10.1016/S0022-2836(66)80022-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedon PC, Begley TJ. 2014. A system of RNA modifications and biased codon use controls cellular stress response at the level of translation. Chem Res Toxicol 27: 330–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias Y, Huang RH. 2005. Biochemical and structural studies of A-to-I editing by tRNA:A34 deaminases at the wobble position of transfer RNA. Biochemistry 44: 12057–12065. 10.1021/bi050499f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Yacoubi B, Bailly M, de Crécy-Lagard V. 2012. Biosynthesis and function of posttranscriptional modifications of transfer RNAs. Annu Rev Genet 46: 69–95. 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emara MM, Ivanov P, Hickman T, Dawra N, Tisdale S, Kedersha N, Hu GF, Anderson P. 2010. Angiogenin-induced tRNA-derived stress-induced RNAs promote stress-induced stress granule assembly. J Biol Chem 285: 10959–10968. 10.1074/jbc.M109.077560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber AP, Keller W. 1999. An adenosine deaminase that generates inosine at the wobble position of tRNAs. Science 286: 1146–1149. 10.1126/science.286.5442.1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giegé R, Lapointe, J. 2009. Transfer RNA aminoacylation and modified nucleosides. In DNA and RNA modification enzymes: structure, mechanism, function and evolution (ed. Grosjean H), pp. 475–485. Landes Bioscience, Austin, Texas. [Google Scholar]

- Giegé R, Puglisi JD, Florentz C. 1993. tRNA structure and aminoacylation efficiency. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 45: 129–206. 10.1016/S0079-6603(08)60869-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giegé R, Jühling F, Pütz J, Stadler P, Sauter C, Florentz C. 2012. Structure of transfer RNAs: similarity and variability. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 3: 37–61. 10.1002/wrna.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean H, de Crécy-Lagard V, Marck C. 2010. Deciphering synonymous codons in the three domains of life: co-evolution with specific tRNA modification enzymes. FEBS Lett 584: 252–264. 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu C, Begley TJ, Dedon PC. 2014. tRNA modifications regulate translation during cellular stress. FEBS Lett 588: 4287–4296. 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.09.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haussecker D, Huang Y, Lau A, Parameswaran P, Fire AZ, Kay MA. 2010. Human tRNA-derived small RNAs in the global regulation of RNA silencing. RNA 16: 673–695. 10.1261/rna.2000810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holley RW, Apgar J, Everett GA, Madison JT, Marquisee M, Merrill SH, Penswick JR, Zamir A. 1965. Structure of a ribonucleic acid. Science 147: 1462–1465. 10.1126/science.147.3664.1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou YM, Schimmel P. 1988. A simple structural feature is a major determinant of the identity of a transfer RNA. Nature 333: 140–145. 10.1038/333140a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov P, Emara MM, Villen J, Gygi SP, Anderson P. 2011. Angiogenin-induced tRNA fragments inhibit translation initiation. Mol Cell 43: 613–623. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackman JE, Alfonzo JD. 2013. Transfer RNA modifications: nature's combinatorial chemistry playground. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 4: 35–48. 10.1002/wrna.1144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner S, Ignatova Z. 2015. Emerging roles of tRNA in adaptive translation, signalling dynamics and disease. Nat Rev Genet 16: 98–112. 10.1038/nrg3861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin EV. 2017. Frozen accident pushing 50: stereochemistry, expansion, and chance in the evolution of the genetic code. Life (Basel) 7: E22 10.3390/life7020022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SW, Cho BH, Park SG, Kim S. 2004. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase complexes: beyond translation. J Cell Sci 117: 3725–3734. 10.1242/jcs.01342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Ender C, Meister G, Moore PS, Chang Y, John B. 2012. Extensive terminal and asymmetric processing of small RNAs from rRNAs, snoRNAs, snRNAs, and tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 40: 6787–6799. 10.1093/nar/gks307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maute RL, Schneider C, Sumazin P, Holmes A, Califano A, Basso K, Dalla-Favera R. 2013. tRNA-derived microRNA modulates proliferation and the DNA damage response and is down-regulated in B cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: 1404–1409. 10.1073/pnas.1206761110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy LS, Shin D, Tor Y. 2014. Isomorphic emissive GTP surrogate facilitates initiation and elongation of in vitro transcription reactions. J Am Chem Soc 136: 15176–15184. 10.1021/ja5039227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan JF, Groebe DR, Witherell GW, Uhlenbeck OC. 1987. Oligoribonucleotide synthesis using T7 RNA polymerase and synthetic DNA templates. Nucleic Acids Res 15: 8783–8798. 10.1093/nar/15.21.8783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notredame C, Higgins DG, Heringa J. 2000. T-Coffee: a novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J Mol Biol 302: 205–217. 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoa EM, Pavon-Eternod M, Pan T, Ribas de Pouplana L. 2012. A role for tRNA modifications in genome structure and codon usage. Cell 149: 202–213. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñeyro D, Torres AG, Ribas de Pouplana L. 2014. Biogenesis and evolution of functional tRNAs. In Fungal RNA biology (ed. Sesma A, Von der Haar T), pp. 233–267. Springer International Publishing, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Pliatsika V, Loher P, Telonis AG, Rigoutsos I. 2016. MINTbase: a framework for the interactive exploration of mitochondrial and nuclear tRNA fragments. Bioinformatics 32: 2481–2489. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliatsika V, Loher P, Magee R, Telonis AG, Londin E, Shigematsu M, Kirino Y, Rigoutsos I. 2018. MINTbase v2.0: a comprehensive database for tRNA-derived fragments that includes nuclear and mitochondrial fragments from all The Cancer Genome Atlas projects. Nucleic Acids Res 46: D152–D159. 10.1093/nar/gkx1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popis MC, Blanco S, Frye M. 2016. Post-transcriptional methylation of transfer and ribosomal RNA in stress response pathways, cell differentiation and cancer. Curr Opin Oncol 28: 65–71. 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafels-Ybern À, Attolini CS, Ribas de Pouplana L. 2015. Distribution of ADAT-dependent codons in the human transcriptome. Int J Mol Sci 16: 17303–17314. 10.3390/ijms160817303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafels-Ybern À, Torres AG, Grau-Bove X, Ruiz-Trillo I, de Pouplana LR. 2018a. Codon adaptation to tRNAs with Inosine modification at position 34 is widespread among Eukaryotes and present in two Bacterial phyla. RNA Biol 15: 500–507. 10.1080/15476286.2017.1358348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafels-Ybern À, Torres AG, Camacho N, Herencia-Ropero A, Roura Frigolé H, Wulff TF, Raboteg M, Bordons A, Grau-Bove X, Ruiz-Trillo I, et al. 2018b. The expansion of Inosine at the wobble position of tRNAs, and its role in the evolution of proteomes. Mol Biol Evol 10.1093/molbev/msy245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragone FL, Spears JL, Wohlgamuth-Benedum JM, Kreel N, Papavasiliou FN, Alfonzo JD. 2011. The C-terminal end of the Trypanosoma brucei editing deaminase plays a critical role in tRNA binding. RNA 17: 1296–1306. 10.1261/rna.2748211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribas de Pouplana L, Torres AG, Rafels-Ybern À. 2017. What froze the genetic code? Life (Basel) 7: E14 10.3390/life7020014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojiani MV, Jakubowski H, Goldman E. 1989. Effect of variation of charged and uncharged tRNATrp levels on ppGpp synthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 171: 6493–6502. 10.1128/jb.171.12.6493-6502.1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio MA, Pastar I, Gaston KW, Ragone FL, Janzen CJ, Cross GA, Papavasiliou FN, Alfonzo JD. 2007. An adenosine-to-inosine tRNA-editing enzyme that can perform C-to-U deamination of DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 7821–7826. 10.1073/pnas.0702394104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Léger A, Bello C, Dans PD, Torres AG, Novoa EM, Camacho N, Orozco M, Kondrashov FA, Ribas de Pouplana L. 2016. Saturation of recognition elements blocks evolution of new tRNA identities. Sci Adv 2: e1501860 10.1126/sciadv.1501860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer M, Pollex T, Hanna K, Tuorto F, Meusburger M, Helm M, Lyko F. 2010. RNA methylation by Dnmt2 protects transfer RNAs against stress-induced cleavage. Genes Dev 24: 1590–1595. 10.1101/gad.586710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaub M, Keller W. 2002. RNA editing by adenosine deaminases generates RNA and protein diversity. Biochimie 84: 791–803. 10.1016/S0300-9084(02)01446-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigematsu M, Kirino Y. 2015. tRNA-derived short non-coding RNA as interacting partners of argonaute proteins. Gene Regul Syst Biol 9: 27–33. 10.4137/GRSB.S29411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobala A, Hutvagner G. 2013. Small RNAs derived from the 5′ end of tRNA can inhibit protein translation in human cells. RNA Biol 10: 553–563. 10.4161/rna.24285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spears JL, Rubio MA, Gaston KW, Wywial E, Strikoudis A, Bujnicki JM, Papavasiliou FN, Alfonzo JD. 2011. A single zinc ion is sufficient for an active Trypanosoma brucei tRNA editing deaminase. J Biol Chem 286: 20366–20374. 10.1074/jbc.M111.243568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su D, Chan CT, Gu C, Lim KS, Chionh YH, McBee ME, Russell BS, Babu IR, Begley TJ, Dedon PC. 2014. Quantitative analysis of ribonucleoside modifications in tRNA by HPLC-coupled mass spectrometry. Nat Protoc 9: 828–841. 10.1038/nprot.2014.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson DM, Parker R. 2009. Stressing out over tRNA cleavage. Cell 138: 215–219. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson DM, Lu C, Green PJ, Parker R. 2008. tRNA cleavage is a conserved response to oxidative stress in eukaryotes. RNA 14: 2095–2103. 10.1261/rna.1232808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres AG, Batlle E, Ribas de Pouplana L. 2014. Role of tRNA modifications in human diseases. Trends Mol Med 20: 306–314. 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres AG, Piñeyro D, Rodríguez-Escribà M, Camacho N, Reina O, Saint-Léger A, Filonava L, Batlle E, Ribas de Pouplana L. 2015. Inosine modifications in human tRNAs are incorporated at the precursor tRNA level. Nucleic Acids Res 43: 5145–5157. 10.1093/nar/gkv277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi S, Sugiura R, Ma Y, Tokuoka H, Ohta K, Ohte R, Noma A, Suzuki T, Kuno T. 2007. Wobble inosine tRNA modification is essential to cell cycle progression in G1/S and G2/M transitions in fission yeast. J Biol Chem 282: 33459–33465. 10.1074/jbc.M706869200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will S, Joshi T, Hofacker IL, Stadler PF, Backofen R. 2012. LocARNA-P: accurate boundary prediction and improved detection of structural RNAs. RNA 18: 900–914. 10.1261/rna.029041.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf J, Gerber AP, Keller W. 2002. tadA, an essential tRNA-specific adenosine deaminase from Escherichia coli. EMBO J 21: 3841–3851. 10.1093/emboj/cdf362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulff TF, Argüello RJ, Molina Jordàn M, Roura Frigolé H, Hauquier G, Filonava L, Camacho N, Gatti E, Pierre P, Ribas de Pouplana L, et al. 2017. Detection of a subset of posttranscriptional transfer RNA modifications in vivo with a restriction fragment length polymorphism-based method. Biochemistry 56: 4029–4038. 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Karcher D, Bock R. 2014. Identification of enzymes for adenosine-to-inosine editing and discovery of cytidine-to-uridine editing in nucleus-encoded transfer RNAs of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 166: 1985–1997. 10.1104/pp.114.250498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.