Abstract

Background.

Racial disparities in use of surgical therapy for lung cancer exist in the United States. Videos of standardized patients (SPs) can help identify factors that influence physicians’ surgical risk estimation. We hypothesized that physician race and SP race in videos influence surgeon decision making.

Methods.

Four race-neutral clinical vignettes representing lung resection candidates were paired with risk-level concordant short silent videos of SPs. Vignette/video combinations were classified as low or high risk. Trainees and practicing thoracic surgeons read a race-neutral vignette, provided an initial estimate of the percentage risk of major surgical complications, viewed a video randomized to a black or white SP, provided a final estimate of risk, and scored the likelihood that they would recommend operative therapy. Changes in risk estimates were assessed.

Results.

Participants included 113 surgeons (38 practicing surgeons, 75 trainees); of these, 76 were white non-Hispanic (67%), and 37 were other self-identified racial categories. Percentage changes between initial and final risk estimates were not significantly related to patient race (p = 0.11) or surgeon race (white versus other; p = 0.52). Videos of black SPs were associated with a similar likelihood of recommending an operation compared with that of videos of white SPs (p = 0.90). Physician race (white versus other) was not related to the likelihood of recommending surgical intervention (p = 0.79).

Conclusions.

Neither patient nor physician race was significantly associated with risk estimation or surgical recommendations. These findings do not provide an explanation for documented racial disparities in lung cancer therapy. Further investigation is needed to identify the mechanism underlying these disparities.

Lung cancer occurs more commonly among blacks than among whites in the United States and is the most common cause of cancer-related death for both whites and blacks [1, 2]. The incidence differences have been partly attributed to differences in exposure and genetic susceptibility to environmental carcinogens, including tobacco. In contrast, the survival differences have been attributed, to some extent, to disparities in health care, including access to screening, use of treatment for early-stage cancer, and access to and use of long-term care and posttreatment surveillance.

Blacks are less likely to undergo curative operations for early-stage lung cancer than their white counterparts [3–5], undergo resections more frequently at lower volume hospitals [6] that might have less-qualified surgeons, and have the lowest survival of any racial group in the United States [7, 8]. Socioeconomic differences may explain some of these discrepancies [9], but verbal communication styles, nonverbal interactions, and biases may also contribute to such differences. Blacks are advised to receive operative interventions less often and refuse surgical therapy more often than whites, suggesting that factors in the physician-patient interaction influence these outcomes [10].

We recently demonstrated that clinical vignettes and short silent videos of standardized patients (SPs) trained to represent lung resection candidates are useful in identifying factors that influence physician surgical risk estimation [11], which may have an effect on treatment recommendations. The present study was designed to use this research template to examine the hypothesis that patient and physician race influence surgical risk estimation and treatment recommendations for early-stage lung cancer.

Patients and Methods

This study was approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board, and the need for written consent was waived because consent was assumed when individuals agreed to participate in the study by registering on-line.

The design of the study was similar to one previously reported [12]. Participants were invited from a list of all practicing thoracic surgeons in academic medical centers and cardiothoracic trainees provided by the Thoracic Surgery Directors Association. Participants were offered $100 for completing the entire study.

Practicing thoracic surgeon participants were required to be involved in trainee education and have an active clinical practice consisting of more than 50% of noncardiac thoracic surgery. Trainee participants were required to be in a traditional program consisting of 2 to 3 years of exclusive cardiothoracic training or be in the final 3 years of a 6-year integrated (I-6) program. Participants specified their age, race/ethnicity, and sex, rated their comfort level with performing a lobectomy, and listed their current year of training or number of years of experience since completing training.

We used histories of actual patients treated for non-small cell lung cancer at our institution to developed clinical vignettes that were race neutral and represented male patients aged 60 to 69 years (samples available at https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/0Bx1a71ganr5JZ1JBcEU5U296VFk?usp=sharing). Assessment of risk status related to comorbidities was graded according to the Charlson Comorbidity Index scores (possible range, 0 to 37), and assessment of physiologic risk status specifically related to lung resection was graded according to the EVAD (Expiratory Volume in the first second, Age, Diffusing capacity) score [13, 14] (possible range of 0 to 12). Estimated total risk score for each vignette was assigned as the sum of the Charlson and EVAD scores. Two patient vignettes were created to be low risk (total score, 3 to 5) and two were created to be high risk (total score, 11 to 13). These scores were not revealed to the study participants.

Two levels of physical performance (“somewhat vigorous” and “somewhat frail”) were assigned performance characteristics with standard metrics based on the Fried phenotypic frailty criteria [15], as previously described [12]. Eight SPs, aged 60 to 69 years, were selected. For research purposes, 2 men of similar apparent age, different race, and similar body mass index were paired for a total of 4 pairs. Each SP was dressed similarly in accordance with their portrayed level of vigor (normally fitting clothing) or frailty (loosely fitting clothing to suggest weight loss), as previously described [12].

Two pairs of SPs each portrayed one of the two levels of physical performance in videos set in a mock outpatient clinic (samples available at https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/0Bx1a71ganr5Jfk1pUnpJUEJfWFoycjF4N1RLOXpvSXdwblktNkNHaTUzWkc2N0w3V3VRRVE?usp=sharing). A custom sound track audible to the SPs was used to indicate the timing of gait, sitting, standing, and climbing onto an examination table so that the overall performances of the paired SPs were as similar as possible. The final videos as viewed by the study participants were silent. Videos of SPs were paired with concordant vignettes: “somewhat vigorous” videos were paired with low-risk vignettes, and “somewhat frail” videos were paired with high-risk vignettes.

Participants were asked to read a clinical vignette and estimate the patient’s risk for major postoperative complications after lobectomy from 0% to 100% using a Likert-like scale with descriptive anchors relative to the frequency of such complications. Participants then viewed a video paired with that vignette randomly selected between white and black SPs. Participants provided a second estimate of surgical risk based on the combination of the vignette and the video. The participants separately rated the relative importance of the vignette and the video to their second risk estimate on a scale of 0% to 100%, with the total summing to 100%. The participants estimated the likeli-hood that they would recommend lobectomy for the patient in the vignette/video. This process was repeated for a total of four vignettes.

Videos were hosted on Vimeo. Study data were collected and managed using the REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) tool hosted at the University of Chicago. REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies [16].

To analyze the data, the Fisher exact test was used to examine the association between trainee status and comfort level with assessing surgical risk. For comparison of percentage changes ([final – initial]/initial × 100) or absolute changes in risk estimates (final – initial), importance of the SP video, and likelihood of recommending surgical therapy by surgeon characteristics (eg, trainee status, race, sex) or SP race, generalized estimating equation (GEE) linear regression models were fit also adjusting for vignette type. This type of model accounts for the correlation between observations from the same surgeon. For further exploration of whether the effect of any of these factors varied by levels of another factor, interaction terms were included in the models (eg, whether the effect of SP race varied by vignette with the inclusion of a SP race by vignette type interaction) but were dropped from the final model if not statistically significant. In addition, the effect of video importance on changes in risk estimates was assessed in a GEE model with percentage change in risk estimates as the dependent variable and vignette type, SP race, and video importance (high versus low based on a median split) as independent variables along with training status, surgeon gender, and surgeon race. Analyses were performed using Stata 14 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

The number of individuals contacted for participation in the study was 495 (191 practicing surgeons and 304 trainees), and 113 (22.8%) completed the study, including 38 practicing surgeons (19.9%) and 75 trainees (24.7%). Surgeons had been in practice a median of 12.5 years (range, 1 to 47 years). Other characteristics are listed in Table 1. Among practicing surgeons, 31 of 38 self-classified as proficient in estimating risk compared with trainees who predominately classified themselves as advanced beginner (n = 23) or competent (n = 42; p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participating Physicians

| Characteristic | No. (%) (n = 113) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 93 (82.3) |

| Female | 20 (17.7) |

| Status | |

| Practicing surgeon | 38 (33.6) |

| Trainee | 75 (66.4) |

| Race | |

| White non-Hispanic | 76 (67.3) |

| East Indian | 11 (9.7) |

| East Asian | 11 (9.7) |

| Black | 2 (1.8) |

| White Hispanic | 7 (6.2) |

| Middle Eastern | 3 (2.6) |

| Other | 3 (2.6) |

| Comfort level | |

| Beginner | 6 (5.3) |

| Advanced beginner | 23 (20.3) |

| Competent | 48 (42.5) |

| Proficient | 36 (31.9) |

Initial risk estimates for major postoperative complications were calibrated to the intended levels of risk in vignettes: 10.2% ± 9.5% for low risk and 27.1% ± 16.7% for high risk (p < 0.001 from GEE model). These values did not differ by the race of the SP video ultimately paired to the vignette. Final risk estimates for major post-operative complications more closely mirrored intended levels of risk in vignettes: 8.5% ± 8.3% for low risk and 35.7% ± 19.5% for high risk (p < 0.001 from GEE model).

Changes in Risk Estimates Based on Viewing SP Videos

In GEE linear regression models with change in risk estimates made after viewing the SP videos as the outcome, absolute changes in risk estimates were not related to surgeon race (white non-Hispanic versus all other, p = 0.97), surgeon gender (p = 0.41), or SP race (p = 0.20) after also controlling for vignette type. There was evidence, however, for a difference related to training status, in which changes in trainees’ scores were less than those among practicing surgeons (p = 0.04). Similarly, in models controlling for vignette, no significant associations were found between the percentage change in risk estimate and surgeon race (p = 0.52), surgeon gender (p = 0.67), or SP race (p = 0.11). However, a difference was identified related to training status, in which percentage changes for trainees were less than those of practicing surgeons (p = 0.03).

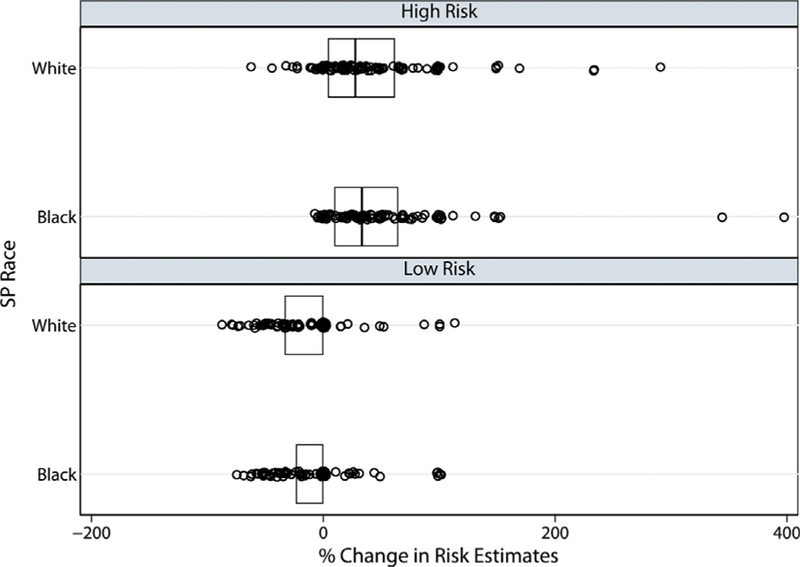

There was no evidence for a vignette-by-SP race interaction when the effect of SP race on absolute changes in risk estimates was assessed (p = 0.60). Similarly, there was no evidence for a vignette-by-SP race interaction when the association of SP race and percentage change in risk estimates was assessed (p = 0.79; Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Observed percentage changes in risk estimates by vignette/video type. The vertical line inside each box represents the median, and the outer edges of each box represent the 25th and 75th percentiles (interquartile range). For low-risk vignette/video combinations, the medians and 75% percentiles were 0. There was no evidence for a vignette-by-standardized patient race interaction when the effect of standardized patient race on risk estimate changes (p = 0.79) or evidence of an overall effect of standardized patient race (p = 0.11) was assessed. (SP standardized patient.)

Importance of SP Videos in Making Final Risk Estimates

GEE linear regression models with video importance as the outcome showed there was no significant SP race-by-vignette interaction (p = 0.15) or surgeon race-by-vignette interaction (p = 0.54). Overall, mean video importance was 36.5% ± 18.2% for black SPs and 39.3% ± 19.1% for white SPs.

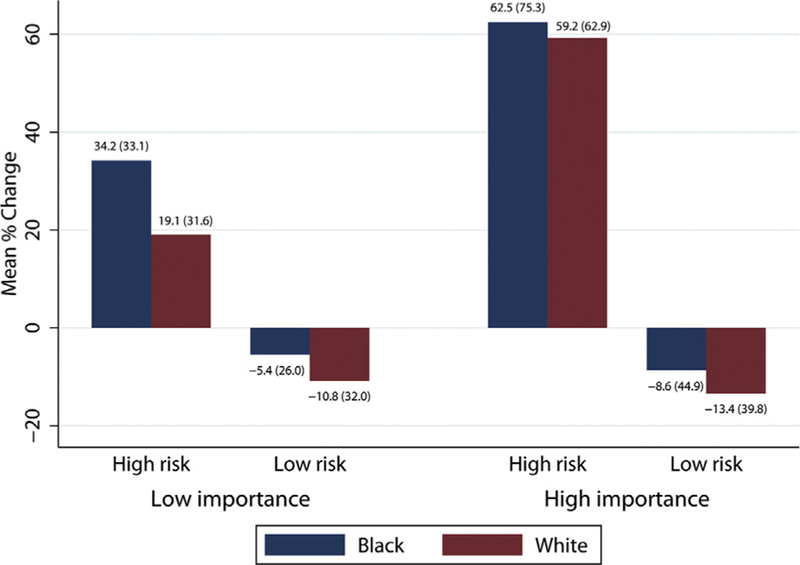

To assess whether rated video importance was significantly related to changes in risk estimation, a GEE linear model regressing change in risk estimation on video importance, categorized as high or low relative to the median importance rating plus the other covariates, was used. Greater video importance was significantly associated with larger changes in risk estimates (p < 0.001; Fig 2). With the inclusion of video importance in the model, there was modest evidence for a difference in risk estimate changes based on SP race (p = 0.07). Black SPs had an approximately 8 percentage point greater increase in risk estimates, on average, than white SPs. There was no evidence for a video importance-by-SP race interaction (p = 0.45), although SP race differences did appear somewhat larger for videos of low importance.

Fig 2.

Video importance category, vignette risk type (high risk versus low risk), and percentage changes in risk estimates comparing black and white standardized patients. The mean (SD) are listed above each bar.

Likelihood of Recommending Lobectomy

We found no overall effect of SP race (p = 0.90) or surgeon race (p = 0.79) on the likelihood of recommending lobectomy. The SP race-by-vignette interaction was not significant (p = 0.16) nor was the surgeon race-by-vignette interaction (p = 0.25).

Comment

Disparities in access to health care resources are well recognized in the United States. Explanations for this problem include urban versus rural location, socioeconomic background, and race. In addition to access to care, subsequent treatment recommendations for many serious medical problems also vary according to these characteristics. In particular, black patients with lung cancer undergo operations less frequently, are treated in lower-volume centers more often, and have poorer survival than white patients [3–5, 17].

The current study was designed to explore some of the factors that affect access to surgical care for early-stage lung cancer, including surgeons’ estimates of surgical risk and their likelihood of recommending surgical intervention related to the race of the patient. We found no strong evidence that the race of an SP video or physician race was associated with differences in risk estimates or the likelihood of recommending surgical intervention. There was a modest increase in risk estimates for black SPs compared with white SPs.

Implicit racial bias among health care workers, characterized by positive attitudes toward whites and negative attitudes toward blacks, is associated with racial variations in treatment recommendations across a wide variety of diseases processes [18]. This may partly account for the lower rate of recommendations for and receipt of surgical intervention for early-stage lung cancer among black patients [3, 10, 19, 20]. Receipt of an operation may also be related to attitudes toward surgeons and operative interventions. Blacks are more distrustful than whites of surgeons and their recommendations, have a lower expectation of benefit from surgical treatment, and are more likely to refuse a surgical intervention when recommended [19, 21, 22].

How current knowledge about the interaction of race and treatment for early-stage lung cancer may relate to the findings in this study is interesting. Positive impressions of white patients and negative impressions of black patients related to intelligence, feelings of affiliation, likelihood of risky behavior, and adherence to medical advice [23] may influence perception of risk, with perception of risk being higher for black patients because of an overall more negative impression of them. There was modest but statistically insignificant evidence in our study that black patients were perceived as having higher risk. However, we did not assess physicians’ impressions of the SPs and so cannot determine the source of this modest difference.

Our finding that surgeons were equally likely to recommend surgical intervention for black SPs as white SPs contrasts with published data that indicate that black patients undergo operations less often. Not much information is available about differences between blacks and whites in the likelihood of being recommended to undergo surgical intervention, in contrast to considerable information demonstrating that white patients have a much higher likelihood of undergoing an operation than do black patients for early-stage lung cancer. Our study was not designed to explore patient-level factors affecting willingness to undergo surgical treatment. Further research is needed to identify why our results differ from clinical practice patterns.

In contrast to a prior study from our group that demonstrated physician gender–related differences in risk estimates and recommendations for operations, we found no such differences in this study [12]. This may be related to the small number of women physicians who participated in the study. We did demonstrate that trainees had smaller changes in risk scores compared with practicing surgeons, confirming findings previously reported by our group [11]. This suggests that trainees use clinical and video information differently than do practicing surgeons.

This study has some potential shortcomings. Some readers may view the use of vignettes as not representing real-world problems, but vignettes have been shown to be very useful in assessing the quality of health care provided by physicians [24]. The number of vignette/video pairings was small because of the difficulty in identifying well-matched SPs of white and black races. The participant response rate was relatively small and may not have been representative of the target physician group. Participants did not include community-based surgeons from low-volume hospitals where more black lung cancer patients tend to be treated, possibly skewing the outcomes. Whether our findings regarding physicians in academic and primarily urban practice settings reflect behavior of physicians in different geographic and practice settings will require additional study.

Although we made every effort to create videos that were comparable between paired black and white SPs, there is the possibility that features we were unable to control for or were unaware of may have affected risk estimates. Only non-Hispanic white and black SPs were included in this study, so the potential influence of other racial and ethnic backgrounds was not assessed.

We conclude, based on clinical vignettes and videos of SP, that surgeons estimated risk for major lung resection similarly for black and white SPs and recommended surgical intervention for black and white SPs at similar rates. The findings are not concordant with our current understanding of disparities in treatment of early-stage lung cancer and require further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This study was partly supported by the Eugenia Dallas Fund for Thoracic Surgery Research. The REDCap project at The University of Chicago is managed by the Center for Research Informatics and funded by the Biological Sciences Division and by the Institute for Translational Medicine, Clinical and Translational Science Awards grant number UL1-RR-024999 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Abidoye O, Ferguson MK, Salgia R. Lung carcinoma in African Americans. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 2007;4:118–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:5–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samuel CA, Landrum MB, McNeil BJ, Bozeman SR, Williams CD, Keating NL. Racial disparities in cancer care in the Veterans Affairs health care system and the role of site of care. Am J Public Health 2014;104(Suppl 4):S562–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Revels SL, Banerjee M, Yin H, Sonnenday CJ, Birkmeyer JD. Racial disparities in surgical resection and survival among elderly patients with poor prognosis cancer. J Am Coll Surg 2013;216:312–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shugarman LR, Mack K, Sorbero ME, et al. Race and sex differences in the receipt of timely and appropriate lung cancer treatment. Med Care 2009;47:774–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun M, Karakiewicz PI, Sammon JD, et al. Disparities in selective referral for cancer surgeries: implications for the current healthcare delivery system. BMJ Open 2014;4: e003921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tannenbaum SL, Koru-Sengul T, Zhao W, Miao F, Byrne MM. Survival disparities in non-small cell lung cancer by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Cancer J 2014;20:237–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardy D, Xia R, Liu CC, Cormier JN, Nurgalieva Z, Du XL. Racial disparities and survival for nonsmall-cell lung cancer in a large cohort of black and white elderly patients. Cancer 2009;115:4807–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landrum MB, Keating NL, Lamont EB, Bozeman SR, McNeil BJ. Reasons for underuse of recommended therapies for colorectal and lung cancer in the Veterans Health Administration. Cancer 2012;118:3345–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lathan CS, Neville BA, Earle CC. The effect of race on invasive staging and surgery in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:413–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson MK, Farnan J, Hemmerich JA, Slawinski K, Acevedo J, Small S. The impact of perceived frailty on surgeons’ estimates of surgical risk. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;98:210–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferguson MK, Huisingh-Scheetz M, Thompson K, Wroblewski K, Farnan J, Acevedo J. The influence of physician and patient gender on preoperative risk assessment for lung cancer resection: a randomized trial. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;104:284–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charlson ME, Sax FL, MacKenzie CR, Braham RL, Fields SD, Douglas RG Jr. Morbidity during hospitalization: can we predict it? J Chronic Dis 1987;40:705–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferguson MK, Durkin AE. A comparison of three scoring systems for predicting complications after major lung resection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2003;23:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)— a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aizer AA, Wilhite TJ, Chen MH, et al. Lack of reduction in racial disparities in cancer-specific mortality over a 20-year period. Cancer 2014;120:1532–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105:e60–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams CD, Stechuchak KM, Zullig LL, Provenzale D, Kelley MJ. Influence of comorbidity on racial differences in receipt of surgery among US veterans with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:475–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sineshaw HM, Wu XC, Flanders WD, Osarogiagbon RU, Jemal A. Variations in receipt of curative-intent surgery for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) by state. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:880–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cykert S, Dilworth-Anderson P, Monroe MH, et al. Factors associated with decisions to undergo surgery among patients with newly diagnosed early-stage lung cancer. JAMA 2010;303:2368–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.George M, Margolis ML. Race and lung cancer surgery—a qualitative analysis of relevant beliefs and management preferences. Oncol Nurs Forum 2010;37:740–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perception of patients. Soc Sci Med 2000;50:813–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M. Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA 2000;283:1715–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]