Abstract

Caregiving burden has been shown to predict use of home care services among Anglo Americans. In a previous study, only one of two dimensions of caregiving burden predicted such use among Mexican American caregivers. Because acculturation and familism may affect burden, we conducted analyses to test three hypotheses: increased acculturation decreases familism; decreased familism increases burden; and increased burden increases use of home care services. Among 140 Mexican American family caregivers, acculturation was positively correlated with familism; familism was not significantly correlated with burden; objective burden was positively correlated with use of home care services, and objective and subjective burden significantly interacted in their effect on the use of home care services. Targeted interventions may be needed to increase use of home care services and preserve the well-being of Mexican American elders and caregivers.

Keywords: caregiving burden, Mexican American, home care services, acculturation, familism

The “parent support ratio” (people aged 80 and over per 100 persons aged 50–64) is forecast to increase rapidly—from 11 in 1990 to 36 in 2050 (Covinsky et al., 2001). This fact, together with the high cost of institutionalization, has raised priority for home care and support for family caregivers in national policy. Minority groups, such as the rapidly growing Latino population, are another high priority in national policy. Latino elders (age 65 and older) comprise 12.5% of the general population but comprise only 5.5% to 6.2% of home care clients (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2007; Madigan, 2007; Valle, Yamada, & Barrio, 2004). Latino elders’ limited use of home care services is made more concerning considering that they are more functionally impaired at younger ages than other elders (Laditka, Laditka, & Drake, 2006). Thirty-six percent of Latino households provide care to an elder, compared to 21% of all other households in the United States (National Alliance for Caregiving, 2008). Latino elders, of whom Mexican American elders comprise the largest percentage, may therefore be in greatest need of home care services. Trends in underutilization of home care services by this population are symptomatic of a significant health care disparity.

Several reasons exist to consider home care services as an option in the care of elders (Covinsky et al., 2001). First, institutionalization is costly and home care can delay or forestall institutionalization. Second, elders who use home care services have better health outcomes such as prevention or delay of onset of acute illness, control of acute illness episodes, and management of chronic conditions (Anderson & Horvath, 2002; Madigan, Tullai-McGuinness, & Neff, 2002). Third, home care services provide needed assistance and education to distressed family caregivers and reduce caregiving burden (National Family Caregivers Association & Family Caregiving Alliance, 2006). Empirical studies with primarily Anglo American samples have shown that higher caregiving burden leads to more admissions to long-term care facilities (Bass & Noelker, 1987; Houde, 1998) or to greater use of home care services (Crist, Kim, Pasvogel, & Velázquez, 2009). The purpose of this study was to examine factors that predict use of home care services by Mexican American elders.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Euro-American individualism has served as the basis of previous U.S. studies on caregiving burden (Bella, Madsen, Sullivan, Swidler, & Tipton, 1996; Phillips & Crist, 2008). We examined caregiving burden along the individualism–collectivism continuum (Triandis, 1995) in a Mexican American community, generally described as collectivistic (Marin & Marin, 1991). The individualistic worldview exists when members of a culture primarily exhibit independence from groups or organizations (Hofstede, 1980), emphasizes personal freedom and expression in an individualistic context (Dutta-Bergman & Wells, 2002; Lam, Chen, & Schaubroeck, 2002), and is characterized as independent and self-reliant (Bordia & Blau, 2003; Triandis, 1994). In contrast, members in a collectivistic culture prefer tightly knit social networks, are largely influenced by group-defined norms and roles (McCarthy & Stadler, 2000; Sato, 2007), and subordinate personal goals for the benefit of the group to maintain interpersonal harmony (McEwen, Baird, Pasvogel, & Gallegos, 2007; Triandis, Bontempo, Villareal, Asai, & Lucca, 1988).

Individualism or collectivism may coexist in individuals in varying degrees in given cultures (Walumbwa, Lawler, & Avolio, 2007). Common societal influences tend to strengthen either individualism or collectivism in any particular culture. Acculturation, which can vary substantially within Mexican American communities, can move individuals along this continuum from collectivism toward individualism, and, we hypothesize, can alter perceptions of caregiving burden.

Acculturation

Acculturation is a blending of behaviors and attitudes between a minority and majority culture (Cuéllar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995). Researchers have predicted that as North American society becomes more complex, shifts toward individualism would be seen (Triandis et al., 1988). These shifts may become apparent in changing traditional values such as familism.

Familism

Within the collectivist worldview, traditional cultural values important to Mexican American elders include familism (the obligation of relatives, particularly children, to provide material and emotional support to family members), simpatia (establishing warm interpersonal relationships), respeto (respect), and personalismo (pleasant social exchanges, cooperation, conformity, and reduction of conflict; Bassford, 1995). These values help group members to work together harmoniously toward common goals. Familistic values also include respecting the dignidad (dignity) of others (Marin & Marin, 1991), especially toward an elder family member who holds a position of prominence and authority. These traditional cultural values specify modes of behavior that are socially acceptable and serve as normative regulatory guides (Walumbwa et al., 2007), especially toward elder family members with care needs in the home.

For example, in Mexican American families, a group-defined norm is that members of the group (family) assume the caregiver role for their elder members. Even in situations in which the elder’s needs require extreme caregiving demands, Mexican American family members may feel bound by the cultural value of familism, to cumplir (comply) or fulfill their obligation to their elder. A family member who tends to cumplir is seen as honorable, dependable, and demonstrating respect and dignity for the family. Thus family caregivers are often the only source of care for Mexican American elders (Scharlach et al., 2006).

The Acculturation-Familism Link

Familism may be changing as Mexican American individuals become more acculturated–individualistic and more driven by personal circumstances such as work obligations and possibly less familistic (Losado et al., 2006; Ruiz, 2007; Strolin-Goltzman, Matto, & Mogro-Wilson, 2007). If acculturation increases, indications are that one of the key values of collectivism—familism—would also shift toward individualism. We recognize that familism was not found to shift due to increased acculturation in an important past study (Sábogal, Marin, Otero-Sábogal, Marin, & Perez-Stable, 1987); yet believe that it may have shifted since then. For example, in a sample of mostly immigrant and first generation Mexican American individuals, Herrera, Lee, Palos, and Torres-Vigil (2008) corroborated earlier findings that higher acculturation was significantly associated with lower levels of familism (e.g., Steidel & Contreras, 2003). As many Mexican American caregivers as well as elders become more acculturated, convergence with collectivism and traditional Mexican American cultural values should be reexamined.

Caregiving Burden

Caregiving burden has been conceptualized as family caregivers’ perceptions of the degree of difficulty they experience due to elders’ impairments (Poulshock & Deimling, 1984). Without skilled or supportive services, elder care at home places an enormous responsibility on caregivers. Elders’ dependence and impairment may be overwhelming for caregivers. Burden can have negative physical and psychological outcomes for the family caregiver, such as cellular immune responses, weight change, problems with health and medical conditions, depression, negative affect (Gitlin et al., 2003; Nelson, Smith, Martinson, Kind, & Luepker, 2008), and stress in relationships with the elder or with other family members (Poulshock & Deimling, 1984). Negative effects on family caregivers can occur when they feel compelled to continue providing family care in spite of experiencing caregiving burden (Crist, 2002). Additionally, Pinquart, and Sörensen’s (2005) meta-analysis reported worse physical health for Mexican American caregivers compared with non-Hispanic White (Anglo-American) caregivers. Burden can be accompanied by decreased family income when family caregivers give up their paid employment to care for their elders. Consequences of caregiving burden can also be profound for elders. It can negatively affect elders through elder abuse, neglect, and abandonment (Phillips, Brewer, & Torres de Ardon, 2001).

Caregiving burden has been operationalized as a two-dimensional construct: objective and subjective. Objective burden has been considered as both the caregivers’ assessment of their elders’ impairment, tasks required by the caregiver, and as the expenditure of a variety of caregivers’ personal resources for their elders (Arévalo, 2008). Family care in the home may be complex and physically exhausting. In-home clients (N = 2,857 Medicaid funded home care assessments) needed more care than nursing home residents (N = 59,623 assessments) because their care involved more complex patterns of clinical problems (e.g., more often having dehydration, internal bleeding, transfusions, dialysis, aphasia, or pneumonia), although the two groups were similar in other ways (e.g., need for special services and reduced physical function; Shugarman, Fries, & James, 1999). Thus care at home can actually be more resource intensive than nursing home care. Elders’ measurable impairments and needs are a good indicator of objective caregiving burden.

Although caregivers’ reports of burden are affected by the actual, objective amount of elders’ limitations and specific needs, reports of burden, strain, or degree of difficulty are also affected by caregivers’ subjective perceptions about providing care (Lim et al., 1996). Subjective burden is a caregiver’s views or feelings about caregiving tasks. Family caregivers’ subjective views of their elders’ needs may have as much negative impact as do actual objective physical tasks. Subjective perspectives of burden can be measured by caregivers’ reports of how tiring, difficult, or upsetting their caregiving tasks are. Studies assessing the relationship between these two types of burden among Mexican American caregivers are lacking and further investigation is warranted.

The Familism-Caregiving Burden Link

As they become more acculturated and less familistic, Mexican American caregivers may report increased burden. Recent research findings suggest that some Mexican American caregivers felt ambivalent about their role rather than embracing completely unexamined, strong familistic expectations to provide elder care (Lee, Jones, Zhang, Chandler, & Stover, 2007). The cumulative effects of caring for elders may outweigh the familistic obligation to care for one’s elders, resulting in a greater sense of burden (Cagle, Wells, Hollen, & Bradley, 2007).

Use of Home Care Services

Home care services consist of skilled care that includes assessment, teaching, and procedures by licensed providers (e.g., registered nurses or physical therapists) for healing, secondary prevention, and rehabilitation for homebound clients. Use of home care services decreases elder functional impairment and use of other health care services, and reduces the indirect costs of caregiver illness, burden, depression, and mortality (Felix, Dockter, Sanderson, Holladay, & Stewart, 2006; Valadez, Lumadue, Gutierrez, & de Vries-Kell, 2005).

The Caregiving Burden—Use of Home Care Services Link

If less familistic Mexican American caregivers report increased burden as being part of the caregiving experience, there is increased likelihood that their elders will decide to use home care services (Crist et al., 2009). Caregivers have reported perceptions of feeling trapped, for example, amarrada or encadenada (chained to their homes) in caring for their elders, and when equipped with the knowledge about resources were inclined to use them (Herrera et al., 2008).

Study Hypotheses and Research Questions

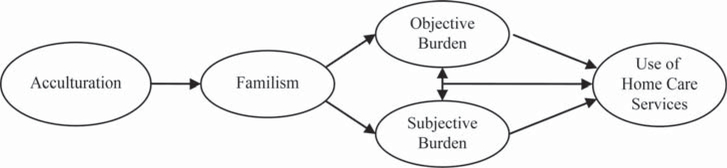

Based on the above studies, viewed in the context of an individualism–collectivism continuum, we proposed that acculturation decreases familism, decreased familism increases burden, and burden increases use of home care services (Crist et al., 2009; Crist, Woo, & Choi, 2007; Herrera et al., 2008). These relationships are illustrated in the conceptual framework shown in Figure 1. In the current study, research questions reflect relationships depicted therein, as follows for Mexican American family caregivers:

Does increased acculturation decrease familism?

Does decreased familism increase caregiving burden?

What is the relationship between objective and subjective burden?

Is objective burden significantly related to the use of home care services if subjective burden is controlled for?

Is subjective burden significantly related to the use of home care services if objective burden is controlled for?

What are the interactive effects of objective and subjective burden on use of home care services?

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

METHOD

Design

The data used in this study were taken from a larger cross-sectional study (Crist et al., 2009). Surveys in English or Spanish were completed by caregivers who were recruited at community settings such as health fairs and neighborhood associations. The University of Arizona Human Subjects Committee approved the study (2004).

Sample

Inclusion criteria were: female, 21 years of age or older, primary caregivers of elders 55 years of age or older, of Mexican descent, able to read or speak Spanish or English, and living with the elder or within a 30-minute drive of the elder’s home. The average age of the 140 Mexican American caregivers was 49.75 years (SD = 13.84); according to the U.S. Census categories, all were of Latino ethnicity (100%; n = 140); most were of the Hispanic White race (90%, n = 126), elders’ daughters (60%; n = 84), married (59%; n = 83), Catholic (76%; n = 107); and had more than a high school education (42%; n = 59). Sixteen percent (n = 22) of the caregivers indicated their elders had used home care.

Measures

Well-known and widely tested instruments used in this study have been tested over time in both Spanish and English in the Mexican American culture. (See, for example, Crist et al., 2009; Crist et al., 2007; Lim et al., 1996). Bicultural–bilingual research assistants assisted participants in completing self-administered questionnaires.

Acculturation was measured with the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans (ARSMA II; Cuéllar et al., 1995). The scale had two dimensions to be measured (Mexican American and Anglo American), which could be combined for a total acculturation score by subtraction. We used the total acculturation measure. Cuéllar and colleagues reported Cronbach’s alphas of .81 and .88 and test–retest reliabilities of .72 and .80 for the Mexican American and Anglo American dimensions respectively. In the current study, alpha for the Mexican American dimension was .84 and for the Anglo American dimension was .92. There were 30 items; the range on the Likert-type scale was 0–5. Higher scores indicated the respondent was more acculturated toward the Anglo American culture.

Familism was measured with the Familism Scale, with Sábogal et al. (1987) reporting alphas that ranged from .64 to .72. There were 14 items; the range on the Likert-type scale was 0–56. Higher scores indicated more influence by the familistic norm. Alpha in the current study was .80.

To measure caregiving burden, we used the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale (Fillenbaum, 1988) for objective burden and the Caregiving Burden Scale (Poulshock & Deimling, 1984) for subjective burden. We chose these adapted measures because of the extensive cross-cultural development and testing of the cultural and language equivalence of the scales by Lim et al. (1996).

Specifically, objective caregiving burden was measured by the ADL scale, (Fillenbaum, 1988), with Fillenbaum reporting test–retest reliability as .88–1.0. There were 15 items; the range on the 0–4 Likert-type scale was 0–60. Higher scores indicated greater functional ability, or lower objective burden. Alpha in the current study was .90. The objective burden mean was 22.2 (SD = 5.23) in this sample.

Subjective burden was measured by Poulshock and Deimling’s (1984) Perceived Burden subscale of the Caregiving Burden Scale, adapted by Crist et al. (2009) and Lim et al. (1996), with Poulshock and Deimling reporting alphas ranging from .67 to .70. To complete the questionnaire, each item on the ADL scale (Fillenbaum, 1988) was scored according to how “tiring, difficult, or upsetting” each item was, with a range of 0–3; the range on the Likert-type scale was 0–45. Alpha in the current study was .95.

As 76 caregivers reported no subjective burden, the measure had marked positive skewness and therefore was categorized. The three categories were: 0 = no caregiving burden (n = 76); 1 = low caregiving burden (n = 35) reflecting scores of 1–3 on Perceived Burden subscale; and 2 = high caregiving burden (n = 29), reflecting scores of 4 or more on the subscale.

Use of home care services was measured using the Utilization of Services Scale (Fillenbaum, 1988). Nine items were tabulated; sums were scored dichotomously for analysis as no use (0 or 1 visit) and use (2 or more visits). One visit was included in the no use category because initial visits are often agreed to, perhaps as a trial, without subsequent visits allowed. A use score would indicate sustained use for more than one initial, often requisite, visit. Higher total scores indicated greater use of home care services. Current Cronbach’s alpha was .90.

Data Analysis

Correlations were used to test the relationships between acculturation and familism and between familism and objective burden. ANOVAs were used to assess differences in familism and objective burden at three levels of subjective burden. Logistic regression was used to assess the relationships between use of home care services and objective and subjective burden, and the interaction of objective and subjective burden. A logistic regression model predicting the dichotomous use of home care services variable from the continuous objective burden and the categorical subjective burden variables was run.

RESULTS

Acculturation and Familism

There was a positive correlation between acculturation and familism (r = .275, p = .001). Individuals with higher scores on acculturation tended to have higher scores on familism.

Familism and Caregiving Burden

There was no difference in familism at three levels of subjective caregiving burden. (F(2,137) = .300, p = .742). Objective caregiving burden was not related to familism (r = .012, p = .891).

Objective and Subjective Caregiving Burden

Objective burden was significantly different, F(2,137) = 3.86, p = .023, at each level of subjective burden, with means in the expected direction. With no subjective caregiving burden there was the highest level of functional ability (or lowest level of objective burden, M = 23.04); with moderate subjective caregiving burden there was a moderate level of functional ability (M = 22.26); and with high levels of subjective caregiving burden there was the lowest level of functional ability (or the highest level of objective burden, M = 19.93).

Caregiving Burden and Use of Home Care Services

The logistic regression for the overall model was significant, χ2 (3, N = 140) = 26.55, p < .001, Cox & Snell R 2 = .173, Nagelkerke R 2 = .297. Subjective burden was not a significant predictor, Wald = 3.49, df = 2, p = .175. Objective burden was significant, Wald = 16.45, df = 1, p < .001. Exp(B) for objective burden (functional ability) was .819 with a 95% CI of .739–.900, indicating that a one point decrease in functional ability resulted in individuals being 22% more likely to use home care services. Thus, objective burden was significantly related to the use of home care services when controlling for subjective burden; but subjective burden was not significantly related to the use of home care services when controlling for objective burden.

A logistic regression was also conducted to evaluate a model predicting use of home care services from objective burden, subjective burden, and their interaction. The overall model was significant (χ2(5, N = 140) = 33.84, p < .001, Cox & Snell R 2 = .215, Nagelkerke R 2 = .370). A significant interaction was found, (χ2(2, N = 140) = 7.29, p = .026). The relationship between use of home care services and objective caregiving burden differed depending upon the level of subjective caregiving burden.

To probe this interaction, we assessed the relationship between use of home care services and objective caregiving burden at each level of subjective caregiving burden. In the model using only caregivers with no subjective caregiving burden, Exp(B) for objective caregiving burden (functional ability) was .713. A one-point increase in caregivers’ objective burden (i.e., a one-point decrease in functional ability) resulted in their elders’ being 40% more likely to use home care services. In the model using only caregivers with low subjective caregiving burden, Exp(B) for objective caregiving burden (functional ability) was 1.135. A one-point decrease in caregivers’ objective burden (i.e., a one-point increase in functional ability) resulted in their elders’ being 14% more likely to use home care services. In the model using only caregivers with high subjective caregiving burden, Exp(B) for objective caregiving burden (functional ability) was .882. A one-point increase in caregivers’ objective burden (i.e., a one-point decrease in functional ability) resulted in their elders’ being 13% more likely to use home care services. When subjective caregiving burden was either none or high, an increase in objective burden was associated with an increased likelihood in using home care services; whereas when it was low, a decrease in objective burden was associated with an increased likelihood in using home care services.

DISCUSSION

In the following sections we discuss our findings vis-à-vis what has been reported in the literature. Specifically, we suggest possible explanations of how acculturation, familism, caregiving burden, and use of home care services were related, discuss practice and research implications, and identify study limitations.

Acculturation and Familism

We found that acculturation and familism were associated but not in the predicted direction. That is, acculturation was higher, rather than lower, for the caregivers who scored more highly on familism. The proposed theory was that as caregivers became more acculturated, their familism would decrease. One possible explanation might be that Mexican American caregivers do not lose their sense of dedication to the family (familism) as they become more acculturated. Perhaps even as they become more acculturated, but also find themselves still in the role of caregiver, they are more cognizant of, and thus report higher, familism. Also, as individuals become more skilled at navigating the individualistically dominant culture (i.e., become more acculturated), they may also value the family even more strongly to maintain a sense of continuity with their original culture, familiar comfort, and safety. This relationship should be examined with other Mexican American caregivers and noncaregiving individuals.

Familism and Caregiving Burden

Familism was not significantly associated with higher burden, as had been anticipated. Lack of associations between familism and caregiving burden may indicate ineffective measures of familism or burden. Steidel and Contreras (2003) have developed a new familism scale for Latino populations, for use especially with less acculturated Latino individuals. Escandón is testing the Intergenerational Caregiver Familism Scale, designed with and for Mexican American caregivers (S. Escandón, personal communication, December 5, 2008). This may be a better instrument to use because it will measure the structure, attitudes, and behavior of Latino family caregivers in a possibly shifting collectivist orientation.

Even though our chosen instruments had been shown to be culturally and language equivalent, it may not be appropriate to try to measure caregiving burden per se with Mexican American caregivers. This might be true particularly since culturally prescribed notions of caring for aging relatives are an expected and normal part of family functioning. This sense of sacrifice is so much the norm that burden in its traditional measurement may not be a relevant construct.

In other studies, Mexican American caregivers have reported being expected to and willing to “suffer apart,” or feel burden without reporting negative experiences of caregiving to others (Bradley, Wells, Cagle, & Barnes, 2007). For instance, there is no exact translation into Spanish of “caregiving burden,” although the phenomenon exists according to Lim et al. (1996). As would be expected based on the collectivistic worldview, Mexican American caregivers have been found to be less likely than more individualistic caregivers to report burden (Coon et al., 2004) even when they have more challenging situations (Depp et al., 2005). Because of the collectivist, familistic worldview, it may be culturally dystonic (Gallagher-Thompson, Solano, Coon, & Arcan, 2003) for Mexican American caregivers to report burden (Herrera et al., 2008; Mendelson, 2003). Within this context, the concept of caregiving burden may be unpalatable to report (Depp et al., 2005). Going a step further, Arévalo (2008) claims caregiving burden is not in the language because it does not exist in the culture. This contradicts Lim et al.’s (1996) finding that “functional equivalence” of burden does exist for Mexican American caregivers (Phillips et al., 1996).

Caregiving Burden and Use of Home Care Services

Results of the ANOVA showed that level of subjective burden accounted for only about 5% of the variance of objective burden. Substantial unaccounted for variance suggests that, as measured in this study, two distinct constructs were assessed in this sample. This interpretation is consistent with the discussion of caregiving burden presented above.

In a previous study only objective burden was associated with use of home care services (Crist et al. 2009). However, in this study, when we categorized subjective burden, we found that objective and subjective burden interacted in their effect on the use of home care services. Bass and Noelker’s (1987) work with Black and Anglo American participants tested and found associations between subjective burden and use of home care services. Houde’s (1998) work with Anglo American participants tested and found associations between objective burden and use of home care services. Our study allowed for not only an assessment of the main effect of subjective and objective burden on use of home care services but also their interaction.

Results of this study suggested that for Mexican American caregivers, the real, objective needs, or the actual work of caregiving, predicted use of home care services more than the subjective impression of the difficulty of the actual work. However, a significant interaction was found indicating a more complex relationship. Based on previous findings, we expected that an increase in objective burden would result in a greater likelihood of using home care services. That was the case with no or high subjective burden. However, with low subjective burden, the pattern was reversed: decreased objective burden was associated with a greater likelihood of using home care services; and increased objective burden was associated with a lesser likelihood of using home care services.

By categorizing subjective burden into three groups, we identified that the low subjective burden group was different from the no and high subjective burden group and may need special attention. When caregivers have low subjective burden, they may feel guilty that they are not doing enough. Thus when the level of subjective burden is low, caregivers might attempt, out of guilt, to be more willing to care for elders (which might increase their objective burden), rather than agreeing to use home care services. In contrast, when there is no subjective burden, there may be nothing to feel guilty about; and when there is high subjective burden, they may be feeling very burdened, thus not feeling guilty, because their subjective feeling of burden is congruent with what they expected. However, for the subgroup of caregivers with low subjective burden, higher objective burden was associated with less use of home care services. In other words, the low subjective burden subgroup might be less willing to use home care services when they are actually needed even more.

Implications and Future Research

The relationship between objective caregiving burden and use of home care services when subjective caregiving burden is low should be tested further. The small percentage (15%) that reported use of home care services warrants using caution when drawing conclusions from these results. If the relationship continues to be supported, important practical implications for this subgroup could be projected. For example, interventions for individuals with low subjective burden could be designed to prevent them from setting themselves up to attempt to deal with more objective burden than they are able, inadvertently resulting in unhealthy consequences. We may design interventions for subgroups, such as caregivers reporting low burden, who may need but not recognize the need for home care services.

As follow-up to the present study in which over half (76) of the caregivers reported no subjective burden, we plan to explore whether burden is not experienced, experienced in other ways (for example, somatically), or whether it is merely socially unacceptable to report it. This complexity needs to continue to be explored, using cross-cultural methods as Phillips (2008) has recommended, such as exploring Anglo and Mexican American familism and experiences of caregiving. A qualitative approach might yield more accurate conceptualizations at this stage (Crist & Tanner, 2003; Vandermause, 2008). The concepts shown to have some impact on use of home care services can then be clarified, refined, and revised and help refine, revise, and develop more effective measures of the caregiving experience in this culture. There is also a need for further research in the conceptualization and measurement of familism and burden or other quality-of-life issues for caregivers. Then culturally competent approaches can be designed to facilitate Mexican American families’ increased use of resources to support the elder and caregiver to decrease caregiving burden, while preserving the culturally important image of the family. Awareness of cultural values and characteristics can help researchers develop useful strategies that increase Mexican American caregivers’ use of home care services.

Limitations

As stated previously, the small percentage (15%) mentioned above who reported use of home care services warrants using caution when drawing conclusions from these results. An additional consideration is trying to measure caregiving burden with Mexican American caregivers. As discussed previously, these caregivers may refuse to report burden or they may not even recognize or acknowledge it as an experience. However, the overall moderate association of subjective burden with use of home care services reported in the current study could be related to a relatively ineffective measure of burden. As discussed previously, we used the Poulshock and Deimling (1984) scale. We may need to explore ways to improve the use of the current burden instrument. Further exploration would include examining how each subcategory (i.e., how tiring, difficult, upsetting) behaves in relation to variables such as use of home care services, acculturation, and familism, as well as contextual realities such as fluctuating caregiver health. To explore and compare the use of other existing burden instruments in collectivistic cultures might also be fruitful. New instruments should be tested.

SUMMARY

Families’ decisions to access home care services are often driven by underlying cultural and social norms that can be manifested by acculturation, familism, and caregiving burden (subjective and objective). These phenomena can alert clinicians to family caregivers who may be approaching their personal threshold and flag them for appropriate intervention, including exploring the use of home care services. Home care services can delay costly institutionalization, provide respite to stressed caregivers, and is congruent with Mexican American elders’ cultural preferences to be cared for at home. Moreover, the effective use of home care services can offset posthospital care costs in the billions of federal dollars each year (Murtaugh, McCall, Moore, & Meadow, 2003).

As the current study demonstrated, relationships among the phenomena studied continue to show inconsistency in their predictive behavior. For instance, acculturation was positively correlated with familism; familism was not significantly correlated with burden; objective burden was positively correlated with use of home care services; and objective and subjective burden significantly interacted in their effect on use of home care services. These phenomena and their relationships and measures require further exploration. Targeted interventions may be needed, depending upon caregivers’ level of burden, to increase use of home care services and preserve the well-being of Mexican American elders and caregivers.

Acknowledgments.

National Institute of Nursing Research, R-15, 1 R15 NR009031-01. Linda R. Phillips, PhD, RN, FAAN, for conceptual and technical assistance, The ENCASA Community Advisory Council, John Haradon, MEd, MSHP, Yu Liu, PhC, RN, and RN, and The University of Arizona College of Nursing Writers’ Group for feedback and editing.

Contributor Information

Janice D. Crist, College of Nursing, The University of Arizona, PO Box 210203, Tucson, AZ 85711.

Marylyn M. McEwen, College of Nursing, The University of Arizona.

Angelica P. Herrera, Data Management & Evaluation, Center for Healthy Aging at National Council on Aging.

Suk-Sun Kim, College of Nursing, The University of Arizona.

Alice Pasvogel, College of Nursing, The University of Arizona.

Joseph T. Hepworth, College of Nursing, The University of Arizona.

REFERENCES

- Anderson G, & Horvath J (2002). Chronic conditions: Making the case for ongoing care. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University. [Google Scholar]

- Arévalo LC (2008, April 17). Is caregiving burden a carga for Hispanic Alzheimer’s caregivers? Paper presented at Western Institute of Nursing, Garden Grove, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Bass DM, & Noelker LS (1987). The influence of family caregivers on elder’s use of in-home services: An expanded conceptual framework. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 28, 184–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassford TL (1995). Health status of Hispanic elders. Clinical Geriatric Medicine, 11(1), 25–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bella R, Madsen R, Sullivan WM, Swidler A, & Tipton SM (1996). Habits of the heart: Individualism and commitment in American life. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bordia P, & Blau G (2003). Moderating effect of allocentrism on the pay referent comparisonpay level satisfaction relationship. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 52(4), 499–514. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley P, Wells JN, Cagle CS, & Barnes D (2007, November 3–7). Suffering apart and the invisibility of the Mexican American caregiver. Paper presented at American Public Health Association, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Cagle CS, Wells JN, Hollen ML, & Bradley P (2007). Weaving theory and literature for understanding Mexican American cancer caregiving. Hispanic Health Care International, 5(4), 149–161. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2007). Current home health care patients, February 2004 Retrieved May 22, 2007, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhhcsd/curhomecare00.pdf

- Coon DW, Rubert M, Solano N, Mausbach B, Kraemer H, Arguelles T, et al. (2004). Well-being, appraisal, and coping in Latina and Caucasian female dementia caregivers: Findings from the REACH study. Aging and Mental Health, 8(4), 330–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covinsky KE, Eng C, Lui L, Sands LP, Sehgal AR, Walter LC, et al. (2001). Reduced employment in caregivers of frail elders. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences, 56, M707–M713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crist JD (2002). Support for families at home: Mexican American elders’ use of skilled home care nursing services. Public Health Nursing, 19, 366–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crist JD, Kim SS, Pasvogel A, Velázquez JH (2009). Mexican American elders’ use of home care services. Applied Nursing Research, 22(1), 26–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crist JD, & Tanner CA (2003). Analyzing data: The process of interpreting hermeneutic phenomenological narratives, observation and other data. Nursing Research, 52, 202–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crist JD, Woo C, & Choi M (2007). Mexican American and Anglo elders’ use of home care services. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 18(4), 339–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar I, Arnold B, & Maldonado R (1995). Acculturation rating scale for Mexican Americans-II: A revision of the original ARSMA Scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 17(3), 275–304. [Google Scholar]

- Depp C, Sorocco K, Kasl-Godley J, Thompson L, Rabinowitz Y, & Gallagher-Thompson D (2005). Caregiver self-efficacy, ethnicity, and kinship differences in dementia caregivers. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 13(9), 787–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta-Bergman MJ, & Wells WD (2002). The values and lifestyles of idiocentrics and allocentrics in an individualist culture: A descriptive approach. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 12(3), 231–242. [Google Scholar]

- Felix H, Dockter N, Sanderson H, Holladay S, & Stewart M (2006). Physicians play important role in families’ long-term care decisions: Choice of home care vs. nursing home. Journal of the Arkansas Medical Society, 103(3), 67–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillenbaum GG (1988). Multidimensional functional assessment of older adults: The Duke older Americans resources and services procedures. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Solano N, Coon D, & Arcan P (2003). Recruitment and retention of Latino dementia family caregivers in intervention research: Issues to face, lessons to learn. The Gerontologist, 43(1), 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Burgio LD, Mahoney D, Burns R, Zhang S, Schulz R, et al. (2003). Effect of multicomponent interventions on caregiver burden and depression: The REACH multisite initiative at 6-month follow-up. Psychology and Aging, 18(3), 361–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera AP, Lee JW, Palos G, & Torres-Vigil I (2008). Cultural influences in the patterns of long-term care use among Mexican American family caregivers. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 27, 141–165. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Houde SC (1998). Predictors of elders’ and family caregivers’ use of formal home services. Research in Nursing & Health, 21, 533–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laditka SB, Laditka JN, & Drake BF (2006). Home- and community-based service use by older African American, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white women and men. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 25(3/4), 129–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam SK, Chen XP, & Schaubroeck J (2002). Participative decision making and employee performance in different cultures: The moderating effects of allocentrism/idiocentrism and efficacy. Academy of Management Journal, 45(5), 905–914. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Jones PS, Zhang XE, Chandler L, & Stover D (2007, November 18). Differences in filial values across five ethnic groups. Paper presented at Gerontological Nursing Association, San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Lim YM, Luna I, Cromwell SL, Phillips LR, Russell CK, & Torres de Ardon E (1996). Toward a cross-cultural understanding of family caregiving burden. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 18(3), 252–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losado A, Shurgot GR, Knight BG, Márquez M, Montorio I, Izal M, et al. (2006). Cross-cultural study comparing the association of familism with burden and depressive symptoms in two samples of Hispanic dementia caregivers. Aging & Mental Health, 10(1), 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan EA (2007). A description of adverse events in home healthcare. Home Healthcare Nurse, 25(3), 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan EA, Tullai-McGuinness S, & Neff DF (2002). Home health services research. Annual Review of Nursing Research, 20, 267–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, & Marin BV (1991). Research with Hispanic populations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy J, & Stadler H (2000). Allocentrism and perceptions of helping. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 14(4), 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen MM, Baird M, Pasvogel A, & Gallegos G (2007). Health-illness transition experiences among Mexican immigrant women with diabetes. Family and Community Health, 30(3), 201–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson C (2003). The roles of contemporary Mexican American women in domestic health work. Public Health Nursing, 20(2), 95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtaugh CM, McCall N, Moore S, & Meadow A (2003). Trends in Medicare home health care use: 1997–2001. Health Affairs, 22, 146–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving. (2008). Retrieved December 16, 2008, from http://www.caregiving.org/

- National Family Caregivers Association & Family Caregiver Alliance. (2006). Prevalence, hours and economic value of family caregiving, Updated state-by-state analysis of 2004 national estimates (by Arno Peter S., PhD). Kensington, MD: NFCA & San Francisco, CA: FCA. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MM, Smith MA, Martinson BC, Kind A, & Luepker RV (2008). Declining patient functioning and caregiver burden/health: The Minnesota Stroke Survey—Quality of Life after Stroke Study. Washington DC: Gerontological Society of America. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LR (2008, April 17). Thoughts about the state of the science related to culturally competent care for persons with chronic illness and its relationship to practice. State of the Science presented at Western Institute of Nursing, Garden Grove, CA. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LR, Brewer BB, & Torres de Ardon E (2001). The elder image scale: A method for indexing history and emotion in family caregiving. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 9(1), 23–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LR, & Crist JD (2008). Social relationships among Mexican American caregivers: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 18(4), 326–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LR, Luna I, Russell CK, Baca G, Lim YM, Cromwell SL, et al. (1996). Toward a cross-cultural perspective of family caregiving. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 18, 236–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulshock SW, & Deimling GT (1984). Families caring for elders in residence: Issues in the measurement of burden. Journal of Gerontology, 39(2), 230–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, & Sörensen S (2007). Correlates of Physical health of informal caregivers: A meta-analysis. Journal of Gerontology, 62B(2), 126–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz ME (2007). Familismo and filial piety among Latino and Asian elders: Reevaluating family and social support. Hispanic Health Care International, 5(2), 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Sábogal F, Marin G, Otero-Sábogal R, Marin B, & Perez-Stable E (1987). Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Health, 9, 397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Sato T (2007). The family allocentrism-idiocentrism scale: Convergent validity and construct exploration. Individual Differences Research, 5(3), 194–200. [Google Scholar]

- Scharlach AE, Kellam R, Ong N, Baskin A, Goldstein C, & Fox PJ (2006). Cultural attitudes and caregiver service use: Lessons from focus groups with racially and ethnically diverse family caregivers. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 47(12), 133–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shugarman LR, Fries BE, & James M (1999). A comparison of home care clients and nursing home residents: Can community based care keep the elderly and disabled at home? Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 18, 25–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steidel AGL, & Contreras JM (2003). A new familism scale for use with Latino populations. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25(3), 312–330. [Google Scholar]

- Strolin-Goltzman J, Matto HC, & Mogro-Wilson C (2007). A comparative analysis of a dual processing substance abuse treatment intervention: Implications for the development of Latino-specific interventions. Hispanic Health Care International, 5(4), 162–168. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC (1994). Culture and social behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC (1995). Individualism and collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC, Bontempo R, Villareal MJ, Asai M, & Lucca N (1988). Individualism and collectivism: Cross-cultural perspectives on self-ingroup relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 323–338. [Google Scholar]

- Valadez AA, Lumadue C, Gutierrez B, & de Vries-Kell S (2005). Family caregivers of impoverished Mexican American elderly women: The perceived impact of adult day care centers. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 384–392. Retrieved April 1, 2007, from www.familiesinsociety.org [Google Scholar]

- Valle R, Yamada AM, & Barrio C (2004). Ethnic differences in social network help-seeking strategies among Latino and Euro-American dementia caregivers. Aging & Mental Health, 8(6), 535–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandermause RK (2008). The poiesis of the question in philosophical hermeneutics: Questioning assessment practices for alcohol use disorders. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 3, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Walumbwa FO, Lawler JJ, & Avolio BJ (2007). Leadership, individual differences, and work-related attitudes: A cross-cultural investigation. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 56(2), 212–230. [Google Scholar]