Abstract

One potential source of new antibacterials is through probing existing chemical libraries for copper-dependent inhibitors (CDIs), i.e., molecules with antibiotic activity only in the presence of copper. Recently, our group demonstrated that previously unknown staphylococcal CDIs were frequently present in a small pilot screen. Here, we report the outcome of a larger industrial anti-staphylococcal screen consisting of 40,771 compounds assayed in parallel, both in standard and in copper-supplemented media. Ultimately, 483 had confirmed copper-dependent IC50 values under 50 μM. Sphere-exclusion clustering revealed that these hits were largely dominated by sulfur-containing motifs, including benzimidazole-2-thiones, thiadiazines, thiazoline formamides, triazino-benzimidazoles, and pyridinyl thieno-pyrimidines. Structure-activity relationship analysis of the pyridinyl thieno-pyrimidines generated multiple improved CDIs, with activity likely dependent on ligand/ion coordination. Molecular fingerprint-based Bayesian classification models were built using Discovery Studio and Assay Central, a new platform for sharing and distributing cheminformatic models in a portable format, based on open-source tools. Finally, we used the latter model to evaluate a library of FDA-approved drugs for copper-dependent activity in silico. Two anti-helminths, albendazole and thiabendazole, scored highly and are known to coordinate copper ions, further validating the model’s applicability.

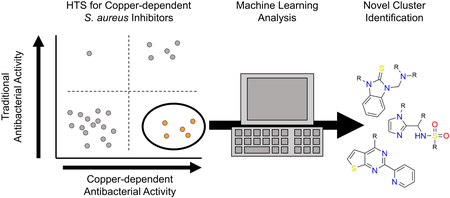

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

Shortly after the discovery of penicillin antibiotic discovery entered a golden age, slowing in the 1960’s after the reservoir of easily accessible natural antibiotics was seemingly exhausted 1. Upon completion of the Haemophilus influenzae genome sequence in 1995, a new age of target-based rational drug design was ushered in, aiming to develop inhibitors for specific cellular targets instead of through whole cell screens. Over the last twenty years, though, this approach has generally failed to meet expectations 2. Increasingly, pharmaceutical companies are divesting themselves of antibiotic discovery efforts due to the very high costs and low rates of success 3, 4. Thus, while new drugs are needed to combat the bacterial threat, so too are drug discovery methodologies themselves, as the paradigmatic target-based approaches of the last twenty years have largely failed us.

Pharmacological exploitation of copper ions is one promising avenue of research, drawing inspiration from the innate immune system’s targeted application of transition metals during infection. In parallel with other phagosomal insults (e.g., acidification, peptidases, iron sequestration, etc.), phagolysosomes are overloaded with copper and zinc ions, relying on the metals’ intrinsic bactericidal properties to aid in phagocytic killing 5, 6. High levels of copper can overwhelm pathogens, and there is increasing evidence that copper resistance is crucial for virulence, both in vitro and in vivo 7–12. Though there is little clinical potential in directly modulating transition metal levels, there has recently been increased interest in the phenomenon of copper-dependent inhibitors (CDIs) and exploiting certain chemical properties of copper ions for therapeutic purposes 13–17.

The phenomenon of CDIs is not without precedent, as many established therapeutics have known copper-dependent activities (e.g. isoniazid, metronidazole, disulfiram) 18–20. Multiple groups have reported copper-dependent antibiotics active against a variety of pathogens, including the Gram-negative Neisseria gonorrhoeae 21, the Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus 22, mycobacteria 23–25, and the eukaryotic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans 26, indicating that this type of antibiotic is broadly applicable in many systems. Relatively little is known regarding copper-dependent mechanisms of action of these molecules, with traditional “one drug one target” action limited to Cu(glyoxal-bis-N 4-methylthiosemicarbazone) inhibition of succinate and NADH dehydrogenases in N. gonorrhoeae 21. More broadly, most known examples appear to act through a general “Trojan Horse” mechanism: CDIs bypass copper defense mechanisms and overload cells with bioactive copper 23–27, resulting in a diverse set of disastrous effects from copper toxicity 16. However, there have been few efforts to specifically identify new CDIs; all noted examples were discovered serendipitously, or through a directed repositioning of chemical probes. Consequently, there has been little added diversity for years, making pharmaceutical advancement unattractive.

Previously, we reported a pilot screen for CDIs against S. aureus, as well as a lead series resulting from that screen 28. Here, we describe the continuation of that study, with two primary goals: adaptation to and deployment on an industrial high-throughput screening platform, and the identification of new and unrecognized chemical motifs associated with copper-dependent antibacterial activity. A total of 40,771 compounds were assayed for copper-dependent anti-staphylococcal activity, ultimately generating 483 confirmed hits and ten novel molecular substructures. Of these substructures, the pyridinyl thieno-pyrimidines were found amenable to structure-activity relationship analysis. In addition, we have leveraged Bayesian classification modeling as both a tool to better describe the characteristics of CDIs, as well as a way to predict CDI activity in existing chemical libraries.

METHODS

Bacterial Strain, Media, and Growth Conditions:

S. aureus strain Newman was grown overnight in Mueller Hinton broth, used to reinoculate fresh broth, and grown to an optical density at 600nm (OD600) of ~1. Cells were washed twice in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI; Corning CellGrow #17105CV) and then resuspended in a mixture of RPMI plus trace elements (TE) as previously described 28. Cells were adjusted to an OD600 of 0.004 and alamarBlue (AB; Life Technologies DAL1001) was added as a viability readout.

High-throughput Screening and Dose Response:

40,771 compounds from an Enamine Ltd. library were ultimately screened. Aliquots of appropriate stock solutions of compounds in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (20 nL of 5 mg/mL stock for single dose or 40 nL of appropriate dilutions for concentration response assays (see below)) were dispensed into duplicate copies of 1536-well assay plates (Corning #3893 or equivalent) using a Labcyte Echo 550 acoustic dispenser. Using a Matrix Combi, 2.5 μL of either RPMI+TE or RPMI+TE+50 μM (final concentration) CuSO4 (Acros Organics #197720010) was added to each set of assay plates. After incubation at room temperature for two hours to allow for coordination complex formation, 2.5 μL of RPMI+TE with a 1:5 dilution of AB (for a final concentration of 1:10, as per manufacturer’s instructions) containing 0.004 OD600 S. aureus was added to wells in columns 1–46 of each assay plate; media without cells was added to columns 47–48 as blanks. Wells in columns 1–4 were cell-only controls. Wells in columns 45–48 received glyoxal-bis-N 4-methylthiosemicarbazone (GTSM) at a final concentration of 1 μM as a positive control instead of a library compound.

For the concentration response confirmation assay, dilution stocks of hit compounds were dispensed into 384-well plates using a BioMek FX, each compound both at 5 mg/mL and 156.25 μg/mL. Each dilution plate was used to create five dilutions, for a total of ten two-fold dilutions ranging from 40 – 0.078 μg/mL with a final concentration of 0.8% dimethyl sulfoxide in each well.

Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) for the pyridinyl thieno-pyrimidines were determined in 96-well microtiter plates following previously published protocols 28. Briefly, compounds were reconstituted from powder in dimethyl sulfoxide. Compounds were added at two-fold final concentration to culture media with or without added copper sulfate and serially diluted down the plate. An equal volume of media with S. aureus was then added. Inhibition was measured by OD600 using a plate reader (Cytation3, Biotek).

ChEMBL Queries and Hit Clustering:

The myChEMBL21 virtual machine 29 was used for all ChEMBL database queries 30. Data is stored in a relational database, allowing conditional searches to automatically harvest activities matching any given search criteria. The following rules were combined to generate a set of compounds with activity against S. aureus: Compounds with annotated activity against S. aureus in culture were filtered for by restricting target type to ‘ORGANISM’ and organism names including ‘Staphylococcus aureus’ (to capture strain designations), yet rejecting genetically modified strains as defined by exclusionary words in the assay description (i.e., ‘carrying’, ‘expressing’, ‘harboring’, ‘bearing’, ‘deficient’). A 50 μM activity cutoff was defined as the ‘nM’ standard units less than or equal to 50,000; compounds with values only reported as ‘ug ml-1’ (ChEMBL uses “u” and not “μ” in its activity records) were first converted to molarity. Compounds with annotated activity against all bacteria were defined simply as those with assays with target type ‘ORGANISM’, organism class ‘Bacteria’, and activity values of not NULL nor ‘0’.

20,605 compounds from ChEMBL were combined with the 483 confirmed hits for a total of 21,088 compounds clustered. Molecular fingerprints were generated with Pybel’s implementation of FP2 31. Compounds were grouped using sphere-exclusion clustering with a Tanimoto coefficient of 0.5.

UV/Vis Spectroscopy:

Compounds were diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide to 100μM, then mixed with 2-fold stocks of metals for final concentrations of 50μM compound and the indicated metal concentrations. Solutions were incubated for 17 hours at room temperature. Spectra were obtained on a Cytation3 using 2nm wavelength steps.

Bayesian Modeling – Assay Central:

As more data sources are added from diverse sources the structure processing becomes increasingly important, as standard representation and de-duplication is essential for high quality machine learning model building. The driving engine of Assay Central 32–34 is a “build system” that can routinely recreate a single model-ready combined dataset for each target-activity group. We applied best-of-breed methodology for checking and correcting structure-activity data 35 which errs on the side of caution for problems with non-obvious solutions, so that we could manually identify problems and either apply patches, or data source-specific automated corrections. These tools were combined to generate a collection of models that can be used to predict the efficacy and/or toxicity of future compounds of interest in a self-contained executable.

Chemical structures were flagged for valence errors, anionic charges were neutralized, salts were removed, and duplicate molecules were merged prior to building a respective model totaling 40,768 compounds. Flagged compounds were cross-referenced across multiple databases and, combined with human knowledge, edited appropriately. Several models were generated from extended connectivity fingerprints (ECFP6) at multiple manually-specified half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value thresholds, but 50 μM was chosen as the most pertinent cut-off for active compounds and is discussed herein; this resulted in 483 “hits” representing positive data, and 40,285 inactives representing negative data. Despite being unbalanced, Bayesian approaches are frequently used for unbalanced datasets, being less affected than that of other machine learning methods 36, 37. Assay Central utilized 5-fold cross-validation of the training data, as well as generating several traditional measurements of model performance: Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) curve, Recall, Precision, F1-Score, Accuracy, Cohen’s Kappa 38, 39, and the Matthews Correlation Constant (MCC) 40. The Assay Central Bayesian model was used to score and predict a set of 1358 approved drugs to propose future molecules for testing.

Bayesian Modeling – Discovery Studio:

We have generated and validated Laplacian-corrected Bayesian classifier models developed with our data using Discovery Studio 4.1 (Biovia, San Diego, CA). The models were all generated using the following molecular descriptors: molecular function class fingerprints of maximum diameter 6 (FCFP6) 41, AlogP, molecular weight, number of rotatable bonds, number of rings, number of aromatic rings, number of hydrogen bond acceptors, number of hydrogen bond donors, and molecular fractional polar surface area which were all calculated from input sdf files. The resulting models were validated using leave-one-out cross-validation and 5-fold validation to generate the ROC area under the curve (ROC AUC), concordance, specificity and selectivity as described previously 42–44.

Bayesian Modeling – RDKit:

To analyze elemental composition of fragments, circular fingerprints were instead generated using RDKit 45. Each fragment was defined according to its unique molecular environment, then converted into an explicit SMILES string (simplified molecular-input line-entry system) using RDKit’s built-in functionality, allowing for interpretability. A separate Laplacian-corrected Bayesian classification model was generated in Python using these interpretable fragments, and a dictionary built containing all non-redundant fragments and scores. Carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur, boron, phosphorous, fluorine, chlorine, bromine, and iodine atoms were enumerated, and percentages calculated as fractions of all heavy atoms in a fragment. Bayesian scores for each fragment were then correlated with elemental proportions.

RESULTS

Assay Validation:

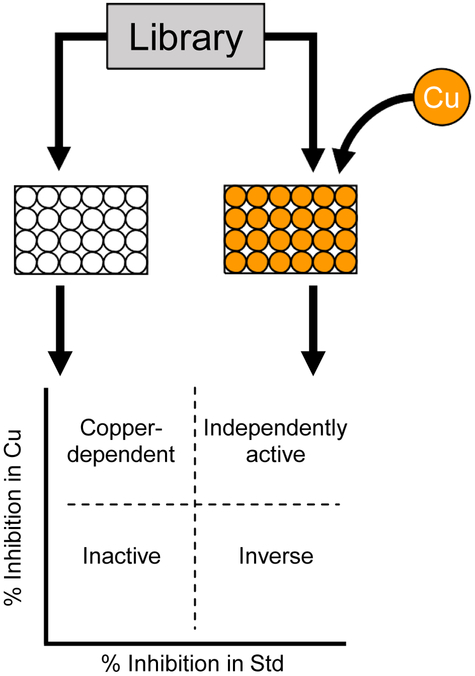

We have previously described a small medium-throughput screen against S. aureus, using a 96-well format. The assay rationale and workflow has been previously published 28, 46, but briefly, compounds were screened in two conditions: standard, unchanged media (consisting of RPMI and supplements; Cu-), and media supplemented with copper to expose copper-dependent inhibitions (Cu+) (Figure 1). Our objective was to adapt the screen to an industrial, high-throughput screening platform, using a 1536-well format.

Figure 1.

The HTS assay is conducted in duplicate, with each compound screened in parallel. One set is assayed with standard RPMI+TE media (white circles), while the second set is assayed in media with 50 μM copper. In contrast to a single run, in which activity cutoffs are binary “yes” or “no,” the two inhibition values combine for four total possible results. The large majority of compounds screened would be inactive in both conditions (lower left quadrant). Many may be active independent of copper content, and would be found by traditional screens (upper right quadrant). Additionally, compounds may rarely display inverse activity, and be inhibitory only in the absence of copper (lower right quadrant). This screen was designed to reveal compounds with inhibition in copper-supplemented media while not inhibiting in standard media (upper left quadrant).

After optimizing workflow conditions, an 8,858 compound subset was screened in parallel to judge reproducibility of the assay in the high-throughput screening format. Both standard media and copper-supplemented conditions were assayed in duplicate. Z’ factors of the controls averaged 0.83 and 0.77 for the Cu+ and Cu- plates, respectively, indicating a robust screen even when miniaturized. Further, the duplicate screens resulted in Pearson correlation coefficients of 0.8236 and 0.7207 for the Cu+ and Cu- conditions, respectively, verifying acceptable reproducibility between screens.

Screen Outcome:

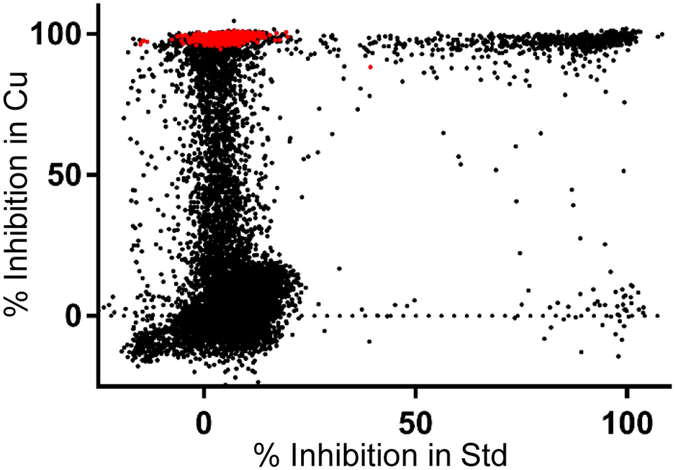

Following the initial run, an additional 31,913 compounds were screened, for a total of 40,771 assayed in both Cu+ and Cu- media (Figure 2). Our original pilot screen revealed primarily thioureas as hit molecules 28. To capture activities in a greater chemical space, we utilized an Enamine library largely devoid of thioureas (0.07% of library), and otherwise more diverse than the library in the pilot screen (as measured by average Tanimoto similarities). From the screened set, 1,478 of the most inhibitory compounds were picked and assayed in a ten-step dose response challenge, resulting in 717 compounds with identifiable copper-dependent IC50 values (Table S1). Of these, 483 had copper-dependent IC50 values below 50 μM resulting in an overall hit rate of 1.2%. This set comprised the final collection of hit molecules for future cheminformatic analyses.

Figure 2.

The results of the HTS for copper-dependent inhibitors of S. aureus. Each dot represents an individual compound, and positions on the X and Y axes represent inhibition in standard RPMI+TE media and inhibition in media containing 50 μM copper, respectively. Red dots represent the final 483 confirmed hits with IC50s less than 50 μM.

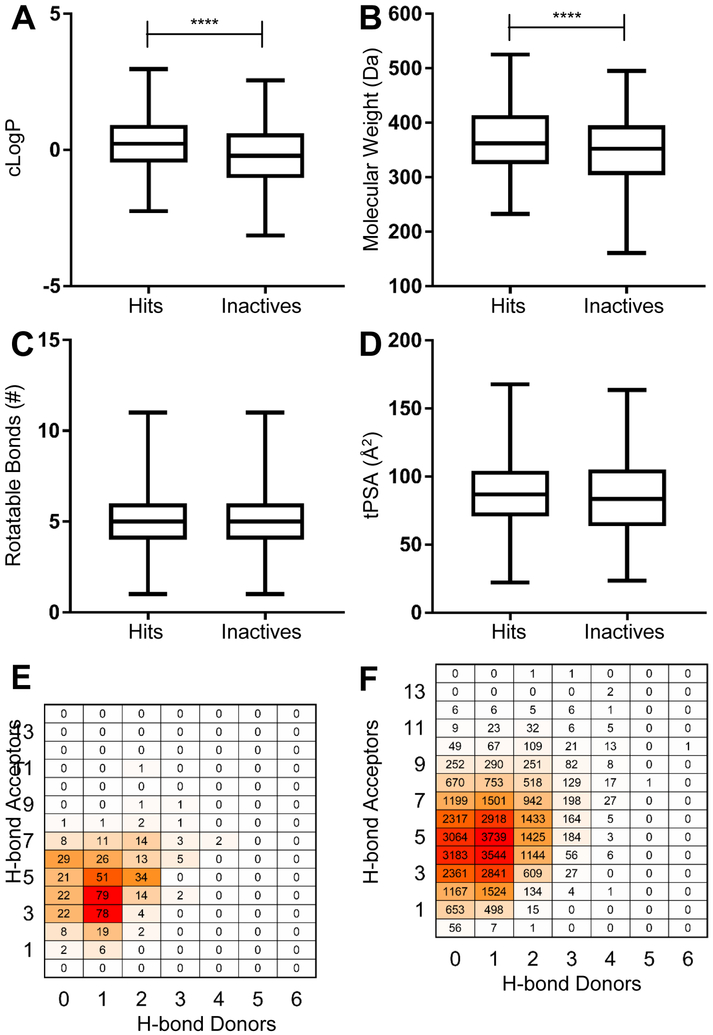

Prior to structural analysis, we compared standard Lipinski Rule of Five (Ro5) properties of the hits versus non-hits 47. As the original screening library was designed to comply with Ro5 definitions, all hits were within guidelines. Octanol/water partition coefficient (cLogP) and molecular weight (MW) were both statistically significantly higher in the hits (Figure 3A, 3B), though no difference was observed in rotatable bonds between hits and inactives (Figure 3C). Our previous pilot screen 28 found significant differences in topological polar surface area (tPSA) and hydrogen bond donors (Hdon) and acceptors (Hacc), which were absent in the larger screen here (Figure 3D–3F). The Hdon/Hacc skew in the original screen was likely a consequence of the high proportion of thioureas (85% and 5.7% of hits and the library, respectively) compared to this screen’s library (0.62% and 0.07% of hits and library, respectively).

Figure 3.

Lipinski Rule of Five properties of hit molecules compared to inactives. cLogP, molecular weight, rotatable bonds, and tPSA were tested for significance using a T test; **** indicates P < 0.0001. E, Hydrogen bond (H-bond) donors and acceptors of hit molecules. F, hydrogen bond donors and acceptors of non-hit molecules.

Clusters of Hits:

Next, we sought to cluster our hits as an aid in future prioritization and identification of chemical motifs associated with copper-dependent anti-staphylococcal activity. However, although this assay screens for novel modes of inhibition (i.e., copper-dependency), these are still commercial libraries; it is possible some hit families have had their antibacterial properties characterized. To avoid such molecules and instead bias our eventual clusters toward unknown antimicrobial scaffolds, we seeded our hit list with 20,605 compounds from the ChEMBL chemical database 30, 48, all annotated as active against whole cell S. aureus at 50 μM or below. Hits with known antimicrobial motifs would cluster with these, filtering them from further analysis.

We focused on clusters composed entirely of our hits, considering clusters containing ChEMBL compounds contaminated. Of 516 clusters with five or more members, comprising 94% of all compounds and 49% of hits, 91 total hits were contained within ten pure clusters (Table 1). Common elements from the clusters were then extracted, translated to SMARTS queries 49, and used to reprobe the screened library.

Table 1.

Ten pure scaffolds from sphere-exclusion clustering of hit molecules

| # | Name | IC50 Median |

# in Cluster |

# in Hits |

# in Screen |

ChEMBL S. aureus |

ChEMBL Prokaryotic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3-Aminomethyl-Benzimidazole-2-Thiones | 23.495 | 16 | 19 | 43 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 6H-1,3,4-Thiadiazines | 20.706 | 16 | 16 | 118 | 0 | 4 |

| 3 | Thiazoline acetamides | 21.561 | 12 | 19 | 94 | 0 | 7 |

| 4 | Triazino-benzimidazoles | 19.979 | 9 | 9 | 38 | 0 | 4 |

| 5 | Pyridinyl thieno-pyrimidines | 6.439 | 6 | 6 | 73 | 0 | 5 |

| 6 | Imidazole sulfonamides | 11.397 | 4 | 5 | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | Aminomethyl-1,3,5-triazine-2,4-diamines | 22.441 | 5 | 6 | 69 | 0 | 10 |

| 8 | 5-Thioxo-1,2,4-triazoles | 36.344 | 4 | 14 | 948 | 92 | 171 |

| 9 | 2-Aminomethyl-4-Pyrimidones | 19.397 | 5 | 25 | 247 | 0 | 3 |

| 10 | 2-Thio-4-quinazolinones | 18.266 | 5 | 7 | 108 | 9 | 37 |

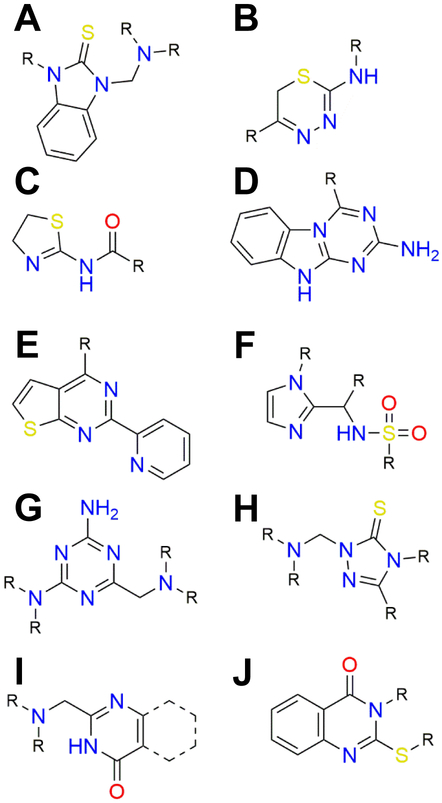

The resulting clusters were largely dominated by sulfur-containing molecules. These include benzimidazole-2-thiones (Figure 4A), thiadiazines (Figure 4B), thiazoline acetamides (Figure 4C), triazino-benzimidazoles (Figure 4D), and pyridinyl thieno-pyrimidines (Figure 4E). Median IC50 values of these clusters ranged from 6.4 μM to 36 μM. All clusters but one were over-represented as hits compared to the library as a whole, as judged by Chi-squared analysis. In fact, the largest cluster (1) was the most over-represented, with 44% of all benzimidazole-2-thiones in the library being confirmed as hits. We then used the extracted substructures to re-query ChEMBL for all compounds annotated as active against prokaryotes. Interestingly, when used to probe this set of 74,689 molecules, two clusters (1, 6) were completely absent, suggesting them likely as novel antimicrobial scaffolds.

Figure 4.

Structural motifs of the ten clusters given in Table 1. R denotes any substituent. I, dotted lines signify a benzene or thiophene ring.

Pyridinyl Thieno-Pyrimidine Structure-Activity-Relationship Analysis

As a validation of the screen, we obtained fresh powder for 9 hits representing three clusters: benzimidazole-2-thiones (Figure 4A), as they were the largest cluster; pyridinyl thieno-pyrimidines (PTPs) (Figure 4E), as they had the lowest median IC50 values; and imidazole sulfonamides (Figure 4F), as they had the second lowest median IC50 values. All compounds had some measure of confirmed activity, though the sulfonamides were comparatively weak (Table S2). Intriguingly, two isomers of the PTP pyridine component were clustered together in the screen results (Table 1, Cluster 5), and representative molecules of both were active after confirmation with fresh powder. The 2,2-bipyridyl motif in hits such as ENM482 (Figure S1A) is well known as a metal chelator 16. However, the 2,3-bipyridyl motif, as present in ENM509 (Figure S1B), has no obvious ability to complex metal ions.

We subsequently selected both isomers of the PTPs for a preliminary structure-activity-relationship analysis by catalog, given their comparable micromolar MICs. We considered the core motif as the thieno-pyrimidine and tested analogs with substitutions at three positions: the hydrophobic group, the pyridinyl ring, and the large substituent off the pyrimidine. Of the eight additional compounds tested, a clear pattern emerged in which the pyridinyl ring was essential for activity: all three analogs with an intact ring offered some level of activity, while none of the five without an intact ring displayed any antibacterial activity (Table S3). We hypothesized that activity was likely due to these compounds’ abilities to coordinate copper ions. To test this, we acquired UV/Vis spectra for each compound alone and in the presence of copper, as coordination complexes often result in spectral shifts. The resulting spectral data aligned with our observed activities (Figure S2), indicating that ion coordination is critical for activity, and that the site of coordination is likely at the bipyridyl motif. Interestingly, bipyridyl itself was completely non-inhibitory in the presence of copper (data not shown), despite also displaying an expected spectral shift.

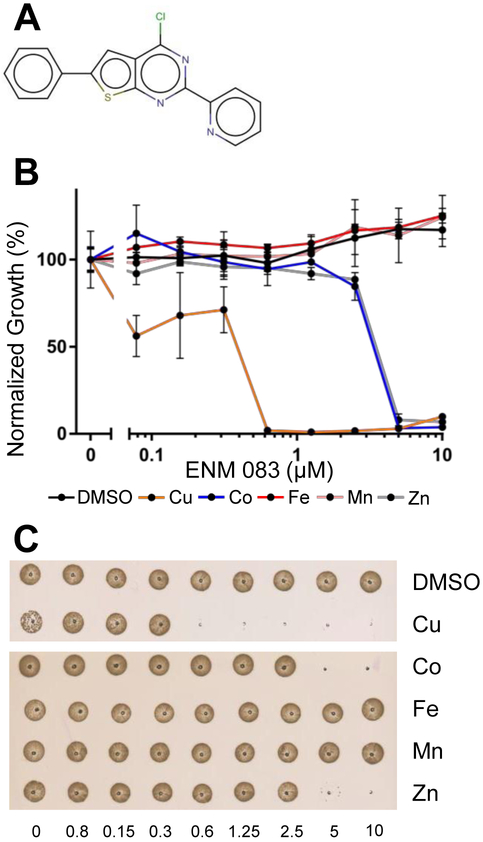

Finally, we probed whether this metal-dependence was specific to copper, selecting ENM083, the most inhibitory CDI in the structure-activity-relationship analysis (Figure 5A). Strikingly, though only copper endowed ENM083 with a sub-micromolar MIC, ENM083 inhibited S. aureus at 5 μM in the presence of both zinc and cobalt (Figure 5B). All metal-related activities were ultimately bactericidal, as judged by spotting the culture on an agar plate (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

ENM 083 has copper-dependent inhibitory activity against S. aureus. A, ENM 083 is a 2,2 pyridinyl thieno-pyrimidine. B, ENM 083 was assayed against S. aureus in a microtiter plate; metals were present at 50μM when indicated. Growth amounts were normalized to individual metal-only control wells. C, drops from the assay plate were spotted on agar to visualize bacteriostatic activity.

Bayesian Classification of Hits:

To date, all canonical CDIs (e.g., 8-hydroxyquinolines, disulfiram, thiosemicarbazones, etc.) derive activity from formation of a coordination complex with copper ions, dependent on localized molecular environments 16. In an attempt to identify additional substructures potentially involved in copper coordination, we used Bayesian classification of molecular fingerprints 50. After decomposing a chemical population into constituent fragments, this model scores each fragment based upon its relative proportions in the hit and non-hit groups. Fragments that are overrepresented in the hit population can be assumed specifically beneficial for copper-dependent activity; conversely, fragments underrepresented or outright absent in the hits may be actively deleterious.

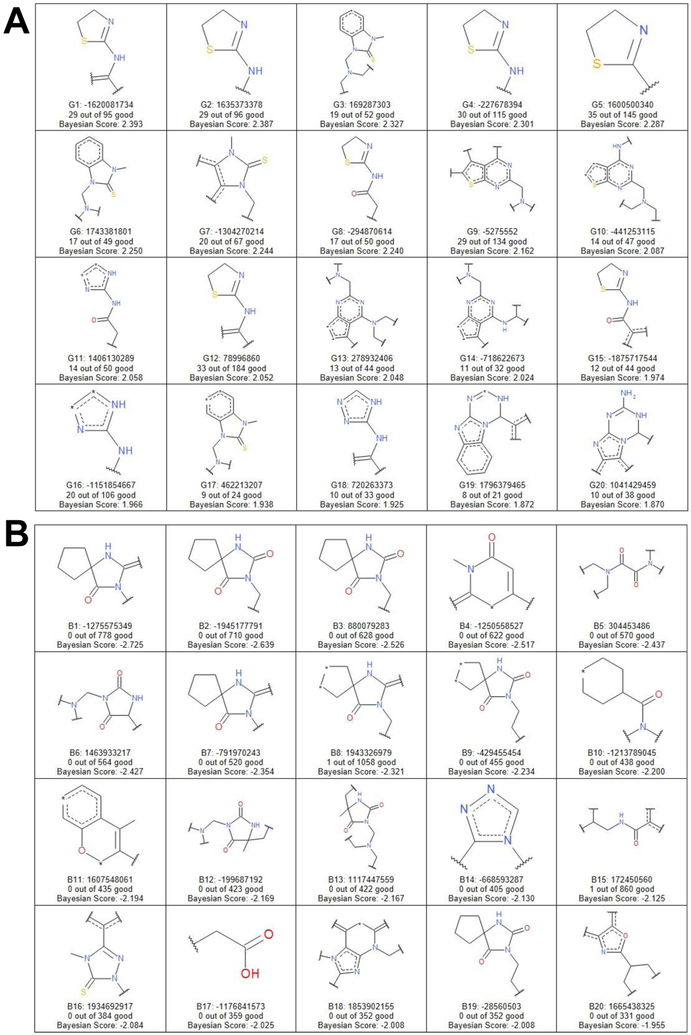

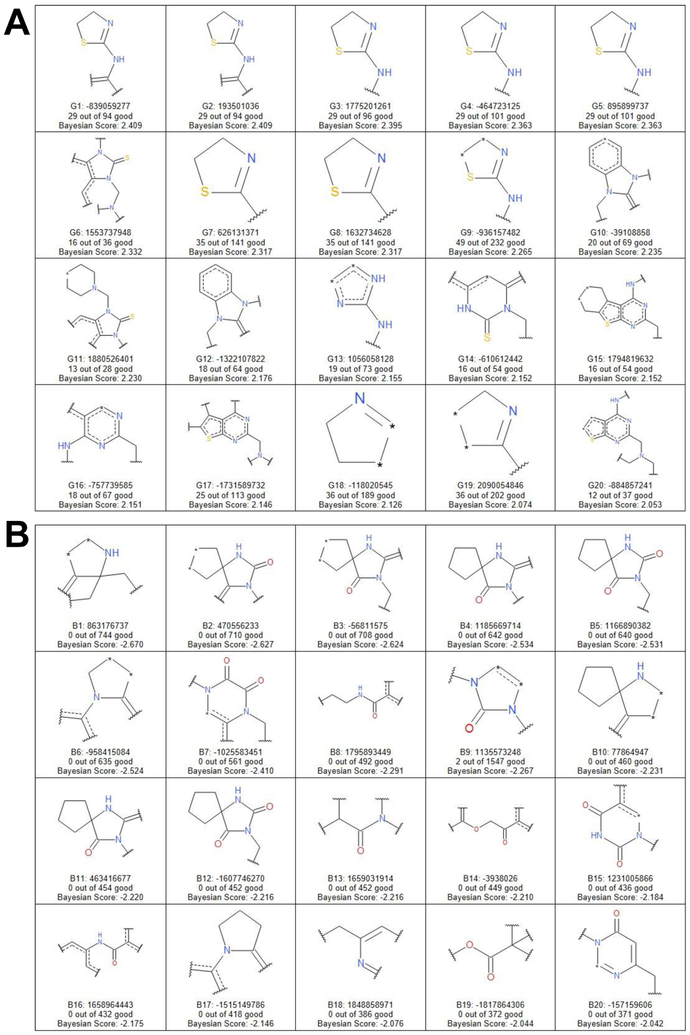

We used either functional connectivity fingerprints with a diameter of 6 (FCFP6) or the extended connectivity fingerprint (ECFP6) to generate fragments for Bayesian modeling 51, 52, and the 20 highest- and lowest-scoring fragments are shown (Figures 6, 7). The predictive nature of the FCFP6 model at cutoff 50 μM was assessed using the 5-fold ROC of 0.83, sensitivity of 0.94, specificity of 0.76, and concordance of 0.77. The ECFP6 model offered slight improvements in assessment statistics, with a 5-fold ROC of 0.84, sensitivity of 0.95, specificity of 0.80, and concordance of 0.80. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the clusters above, the top-scoring fragments were dominated by sulfur-containing motifs such as benzimidazole-2-thiones, thiazolines, and thienopyrimidines. Conversely, the bottom-scoring fragments disproportionately included oxygens, such as 2,4-imidazolidinediones. In fact, when expressed as a proportion of a fragment’s total size, sulfur positively correlated with score while oxygen negatively correlated (Figure S3). Copper is well-known to have the highest affinity for oxygen and sulfur of all the biologically relevant transition metals 53, though this is the first generalizable evidence of the importance of sulfur for CDI activity.

Figure 6.

Selected fragments after Bayesian modeling using FCFP6 features. A, the 20 highest scoring fragments, i.e., the most overrepresented in the hit population. B, the 20 lowest scoring fragments, i.e., the most underrepresented in the hits compared to the screen population as a whole.

Figure 7.

Selected fragments after Bayesian modeling using ECFP6 features. A, the 20 highest scoring fragments, i.e., the most overrepresented in the hit population. B, the 20 lowest scoring fragments, i.e., the most underrepresented in the hits compared to the screen population as a whole.

To make our models more widely available we used the new Assay Central technology, delivering the model in a standard, stable, and portable format 32, 33, 52, 54; the complete model is available on GitHub (see Supporting Information section). We built Bayesian models with the ECFP6 descriptor alone and generated a 5-fold cross validation ROC of 0.86; additional statistics include a precision of 0.04, recall of 0.81, specificity of 0.79, F1 score of 0.085, Kappa score of 0.064, and MCC of 0.16 (Figure S4). This software can be utilized for scoring new molecules, and visualizing the ECFP6 feature contributions to the prediction score across entire compounds (Figure S5A). As an early partial external validation and proof of principle, we scored a small library of FDA approved compounds and identified several, including albendazole and thiabendazole, that have features indicating CDI activity (Figure S5B). Strikingly, both of these drugs have long-known copper coordination complexes that enhance activity 55–58, though no copper-dependent antibacterial activities have been reported.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report the continuation of a previous small scale anti-Staphylococcal screen, miniaturized and adapted to a 1536-well format on an industrial discovery platform. 40,771 compounds were screened in parallel against S. aureus, both in standard and copper-supplemented conditions. Of 1,478 cherry picked active compounds, 483 ultimately had copper-dependent anti-Staphylococcal activity with IC50 values below 50 μM. Unbiased clustering of the confirmed hits resulted in 10 potential hit series. These data were used to generate Bayesian models to identify molecular substructures that are key for activity (Figure 4), using FCFP6 fingerprints and several simple interpretable descriptors. We have also made readily available a model built on ECFP6 descriptors alone so that others can predict compounds of interest to identify new CDIs, using the Assay Central technology.

The substructures presented within comprise the first collection of potential CDI motifs found through library screening, rather than later elucidation of antibiotic effects (e.g., disulfiram, 8-hydroxyquinolines, thiosemicarbazones, phenanthrolines, pyrithiones). Interestingly, despite specifically selecting a library low in thioureas (30 of 40,771), they were still overrepresented in our hits (3 of 483, or 10% of all thioureas screened). This further suggests thioureas as a motif with an intrinsic likelihood of copper-dependent antibacterial activity.

Traditional antibiotics often rely on a one-drug-one-target approach, in which a molecule will bind to a pocket on a ribozyme (e.g., aminoglycosides, macrolides) or enzyme (e.g., rifamycins, β-lactams), or bind specific cellular components to prevent enzymatic reactions (e.g., glycopeptides). In contrast, all known CDIs rely on ligand coordination with copper ions, resulting in a variety of cellular effects including generalized copper overload and poisoning 16. Despite ostensibly comprising a single class of bacterial inhibitors, given the apparent similar modes of action, active core structures of known CDIs vary significantly. Some CDIs use a single element, such as disulfiram coordinating copper ions with four sulfurs 23, or phenanthrolines using four nitrogens across two ligands 59. Others use a mixture, including a single thiosemicarbazone ligand complexing with two nitrogens and two sulfurs 27, pyrithione coordinating copper with two sulfurs and two oxygens across two ligands 17, or 8-hydroxyquinolines using one or two ligands depending on concentration, with one oxygen and one nitrogen per ligand 24.

Of the high-scoring fragments describe here, it is not always immediately apparent whether the structure is directly involved in binding to copper ions. Some, such as the pyridinyl-thieno-pyrimidines, mimic already known copper-coordinating compounds (i.e., bipyridyl). Most, though, are less obvious. This is hardly unprecedented, though, as the NNSN lead series from our previous study challenged conventional wisdom of a thiourea’s coordination scheme. Rather than a 2:1 ligand:ion complex, as is generally seen with thiourea/copper complexes, the NNSN scaffold employed a carbon within a nearby pyrazole ring to coordinate the ion 28. Such a scheme was unknown, suggesting that antibacterial screens such as these could be used as a pseudo-reporter system for novel coordination chemistry.

Supplementary Material

Significance:

This work details the first industrial-scale screening effort harnessing the phenomenon of copper-dependent inhibitors (CDIs) of drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a devastating human pathogen. CDIs are remarkable small molecules that gain significant antibacterial abilities upon coordinating copper ions, readily present at sites of infection. Here, we employ a modified screening approach to uncover these compounds within existing chemical libraries. After the screen, we utilize an unbiased cheminformatics approach for automated large-scale data extraction and interpretation, including clustering, modeling, and in silico prediction of new CDIs. These models are released using the new Assay Central distribution system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Biovia are kindly acknowledged for making Discovery Studio accessible to SE. We thank Stefan Bossmann for proofreading the manuscript. ChemDraw (PerkinElmer Informatics) was used for generating chemical structures.

Grant information

A significant portion of this study was supported by NIH grant R01AI121364 awarded to FW. AD was supported by the Carmichael Fellowship. SE kindly acknowledges NIH funding R43GM122196 and R44 GM122196–02A1 from NIGMS.

Footnotes

Competing interests:

SE works for and owns Collaborations Pharmaceuticals, Inc. KMZ works for Collaborations Pharmaceuticals, Inc. AMC consults for Collaborations Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Supporting information is available on the journal’s website. Screening data is available on PubChem Bioassay. The Assay Central model is available at https://github.com/adalecki/sr_40k/raw/master/SR_40k_Metallomics_Assay_Central.jar

References

- 1.Lewis K, Platforms for antibiotic discovery, Nature reviews. Drug discovery, 2013, 12, 371–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sams-Dodd F, Target-based drug discovery: is something wrong?, Drug discovery today, 2005, 10, 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Payne DJ, Gwynn MN, Holmes DJ and Pompliano DL, Drugs for bad bugs: confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery, Nature reviews. Drug discovery, 2007, 6, 29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tommasi R, Brown DG, Walkup GK, Manchester JI and Miller AA, ESKAPEing the labyrinth of antibacterial discovery, Nature reviews. Drug discovery, 2015, 14, 529–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hood MI and Skaar EP, Nutritional immunity: transition metals at the pathogen-host interface, Nature reviews. Microbiology, 2012, 10, 525–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu Y, Chang FM and Giedroc DP, Copper Transport and Trafficking at the Host-Bacterial Pathogen Interface, Accounts of chemical research, 2014, DOI: 10.1021/ar500300n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson MDL, Kehl-Fie TE, Klein R, Kelly J, Burnham C, Mann B and Rosch JW, Role of Copper Efflux in Pneumococcal Pathogenesis and Resistance to Macrophage-mediated Immune Clearance, Infection and immunity, 2015, DOI: 10.1128/iai.03015-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi X, Festa RA, Ioerger TR, Butler-Wu S, Sacchettini JC, Darwin KH and Samanovic MI, The copper-responsive RicR regulon contributes to Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence, mBio, 2014, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rowland JL and Niederweis M, A multicopper oxidase is required for copper resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Journal of bacteriology, 2013, 195, 3724–3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolschendorf F, Ackart D, Shrestha TB, Hascall-Dove L, Nolan S, Lamichhane G, Wang Y, Bossmann SH, Basaraba RJ and Niederweis M, Copper resistance is essential for virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2011, 108, 1621–1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker J, Sengupta M, Jayaswal RK and Morrissey JA, The Staphylococcus aureus CsoR regulates both chromosomal and plasmid-encoded copper resistance mechanisms, Environmental microbiology, 2011, 13, 2495–2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding C, Festa RA, Chen YL, Espart A, Palacios O, Espin J, Capdevila M, Atrian S, Heitman J and Thiele DJ, Cryptococcus neoformans copper detoxification machinery is critical for fungal virulence, Cell host & microbe, 2013, 13, 265–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ananthan S, Faaleolea ER, Goldman RC, Hobrath JV, Kwong CD, Laughon BE, Maddry JA, Mehta A, Rasmussen L, Reynolds RC, Secrist JA 3rd, Shindo N, Showe DN, Sosa MI, Suling WJ and White EL, High-throughput screening for inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv, Tuberculosis, 2009, 89, 334–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waldron KJ and Robinson NJ, How do bacterial cells ensure that metalloproteins get the correct metal?, Nat Rev Micro, 2009, 7, 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Festa RA and Thiele DJ, Copper at the front line of the host-pathogen battle, PLoS pathogens, 2012, 8, e1002887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalecki AG, Crawford CL and Wolschendorf F, in Advances in microbial physiology, ed. Poole RK, Academic Press, 2017, vol. 70, pp. 193–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Djoko KY, Achard MES, Phan M-D, Lo AW, Miraula M, Prombhul S, Hancock SJ, Peters KM, Sidjabat HE, Harris PN, Mitić N, Walsh TR, Anderson GJ, Shafer WM, Paterson DL, Schenk G, McEwan AG and Schembri MA, Copper Ions and Coordination Complexes as Novel Carbapenem Adjuvants, Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2018, 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rieber M and Bemski G, Studies on isoniazid-copper interaction, The Biochemical journal, 1968, 109, 39P–40P. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Athar F, Husain K, Abid M, Agarwal SM, Coles SJ, Hursthouse MB, Maurya MR and Azam A, Synthesis and Anti-Amoebic Activity of Gold(I), Ruthenium(II), and Copper(II) Complexes of Metronidazole, Chemistry & Biodiversity, 2005, 2, 1320–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen D, Cui QC, Yang H and Dou QP, Disulfiram, a clinically used anti-alcoholism drug and copper-binding agent, induces apoptotic cell death in breast cancer cultures and xenografts via inhibition of the proteasome activity, Cancer research, 2006, 66, 10425–10433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Djoko KY, Paterson BM, Donnelly PS and McEwan AG, Antimicrobial effects of copper(ii) bis(thiosemicarbazonato) complexes provide new insight into their biochemical mode of action, Metallomics : integrated biometal science, 2014, DOI: 10.1039/c3mt00348e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haeili M, Moore C, Davis CJC, Cochran JB, Shah S, Shrestha TB, Zhang Y, Bossmann SH, Benjamin WH, Kutsch O and Wolschendorf F, Copper complexation screen reveals compounds with potent antibiotic properties against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2014, 58, 3727–3736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dalecki AG, Haeili M, Shah S, Speer A, Niederweis M, Kutsch O and Wolschendorf F, Disulfiram and copper ions kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a synergistic manner, Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2015, DOI: 10.1128/aac.00692-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah S, Dalecki AG, Malalasekera AP, Crawford CL, Michalek SM, Kutsch O, Sun J, Bossmann SH and Wolschendorf F, 8-Hydroxyquinolines Are Boosting Agents of Copper-Related Toxicity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2016, 60, 5765–5776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salina EG, Huszár S, Zemanová J, Keruchenko J, Riabova O, Kazakova E, Grigorov A, Azhikina T, Kaprelyants A, Mikušová K and Makarov V, Copper-related toxicity in replicating and dormant Mycobacterium tuberculosis caused by 1-hydroxy-5-R-pyridine-2(1H)-thiones, Metallomics : integrated biometal science, 2018, 10, 992–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Festa RA, Helsel ME, Franz KJ and Thiele DJ, Exploiting innate immune cell activation of a copper-dependent antimicrobial agent during infection, Chemistry & biology, 2014, 21, 977–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Djoko KY, Goytia MM, Donnelly PS, Schembri MA, Shafer WM and McEwan AG, Copper(II)-bis(thiosemicarbazonato) complexes as antibacterial agents: insights into their mode of action and potential as therapeutics, Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2015, DOI: 10.1128/aac.01289-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalecki AG, Malalasekera AP, Schaaf K, Kutsch O, Bossmann SH and Wolschendorf F, Combinatorial phenotypic screen uncovers unrecognized family of extended thiourea inhibitors with copper-dependent anti-staphylococcal activity, Metallomics : integrated biometal science, 2016, DOI: 10.1039/C6MT00003G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ochoa R, Davies M, Papadatos G, Atkinson F and Overington JP, myChEMBL: a virtual machine implementation of open data and cheminformatics tools, Bioinformatics, 2014, 30, 298–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaulton A, Hersey A, Nowotka M, Bento AP, Chambers J, Mendez D, Mutowo P, Atkinson F, Bellis LJ, Cibrián-Uhalte E, Davies M, Dedman N, Karlsson A, Magariños MP, Overington JP, Papadatos G, Smit I and Leach AR, The ChEMBL database in 2017, Nucleic acids research, 2017, 45, D945–D954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Boyle NM, Morley C and Hutchison GR, Pybel: a Python wrapper for the OpenBabel cheminformatics toolkit, Chemistry Central journal, 2008, 2, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russo DP, Zorn KM, Clark AM, Zhu H and Ekins S, Comparing Multiple Machine Learning Algorithms and Metrics for Estrogen Receptor Binding Prediction, Molecular pharmaceutics, 2018, 15, 4361–4370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lane T, Russo DP, Zorn KM, Clark AM, Korotcov A, Tkachenko V, Reynolds RC, Perryman AL, Freundlich JS and Ekins S, Comparing and Validating Machine Learning Models for Mycobacterium tuberculosis Drug Discovery, Molecular pharmaceutics, 2018, 15, 4346–4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandoval PJ, Zorn KM, Clark AM, Ekins S and Wright SH, Assessment of Substrate-Dependent Ligand Interactions at the Organic Cation Transporter OCT2 Using Six Model Substrates, 2018, 94, 1057–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karapetyan K, Batchelor C, Sharpe D, Tkachenko V and Williams AJ, The Chemical Validation and Standardization Platform (CVSP): large-scale automated validation of chemical structure datasets, Journal of Cheminformatics, 2015, 7, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carbon-Mangels M and Hutter MC, Selecting Relevant Descriptors for Classification by Bayesian Estimates: A Comparison with Decision Trees and Support Vector Machines Approaches for Disparate Data Sets, 2011, 30, 885–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hassan M, Brown RD, Varma-O’Brien S and Rogers DJMD, Cheminformatics analysis and learning in a data pipelining environment, 2006, 10, 283–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carletta J, Assessing Agreement on Classification Tasks: The Kappa Statistic, Computational Linguistics, 1996, 22, 249–254. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen J, A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales, Educational and Psychological Measurement, 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matthews BW, Comparison of the predicted and observed secondary structure of T4 phage lysozyme, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Protein Structure, 1975, 405, 442–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones DR, Ekins S, Li L and Hall SD, Computational Approaches That Predict Metabolic Intermediate Complex Formation with CYP3A4 (+b5), Drug Metabolism and Disposition, 2007, 35, 1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ekins S, Reynolds Robert C., Kim H, Koo M-S, Ekonomidis M, Talaue M, Paget Steve D., Woolhiser Lisa K., Lenaerts Anne J., Bunin Barry A., Connell N and Freundlich Joel S., Bayesian Models Leveraging Bioactivity and Cytotoxicity Information for Drug Discovery, Chemistry & biology, 2013, 20, 370–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ekins S, Reynolds RC, Franzblau SG, Wan B, Freundlich JS and Bunin BA, Enhancing Hit Identification in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Drug Discovery Using Validated Dual-Event Bayesian Models, PloS one, 2013, 8, e63240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ekins S, Casey AC, Roberts D, Parish T and Bunin BA, Bayesian models for screening and TB Mobile for target inference with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Tuberculosis, 2014, 94, 162–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Journal.

- 46.Dalecki AG and Wolschendorf F, Development of a web-based tool for automated processing and cataloging of a unique combinatorial drug screen, Journal of microbiological methods, 2016, 126, 30–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW and Feeney PJ, Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings, Adv Drug Del Rev, 1997, 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gaulton A, Bellis LJ, Bento AP, Chambers J, Davies M, Hersey A, Light Y, McGlinchey S, Michalovich D, Al-Lazikani B and Overington JP, ChEMBL: a large-scale bioactivity database for drug discovery, Nucleic acids research, 2012, 40, D1100–D1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Journal.

- 50.Xia X, Maliski EG, Gallant P and Rogers D, Classification of Kinase Inhibitors Using a Bayesian Model, Journal of medicinal chemistry, 2004, 47, 4463–4470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Astorga B, Ekins S, Morales M and Wright SH, Molecular Determinants of Ligand Selectivity for the Human Multidrug and Toxin Extruder Proteins MATE1 and MATE2-K, Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 2012, 341, 743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clark AM and Ekins S, Open Source Bayesian Models. 2. Mining a “Big Dataset” To Create and Validate Models with ChEMBL, Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 2015, 55, 1246–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nies D, in Molecular Microbiology of Heavy Metals, eds. Nies D and Silver S, Springer Berlin; Heidelberg, 2007, vol. 6, ch. 75, pp. 117–142. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clark AM, Dole K, Coulon-Spektor A, McNutt A, Grass G, Freundlich JS, Reynolds RC and Ekins S, Open Source Bayesian Models. 1. Application to ADME/Tox and Drug Discovery Datasets, Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 2015, 55, 1231–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miller VL, Gould CJ, Csonka E and Jensen RL, Metal coordination compounds of thiabendazole, Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 1973, 21, 931–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fu X-B, Zhang J-J, Liu D-D, Gan Q, Gao H-W, Mao Z-W and Le X-Y, Cu(II)–dipeptide complexes of 2-(4′-thiazolyl)benzimidazole: Synthesis, DNA oxidative damage, antioxidant and in vitro antitumor activity, Journal of inorganic biochemistry, 2015, 143, 77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gao Y, Li H, Li X and Sun Z, Combined subacute toxicity of copper and antiparasitic albendazole to the earthworm (Eisenia fetida), Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2016, 23, 4387–4396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zafar A, Ahmad I, Ahmad A and Ahmad M, Copper(II) oxide nanoparticles augment antifilarial activity of Albendazole: In vitro synergistic apoptotic impact against filarial parasite Setaria cervi, International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 2016, 501, 49–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pallenberg AJ, Koenig KS and Barnhart DM, Synthesis and Characterization of Some Copper(I) Phenanthroline Complexes, Inorganic chemistry, 1995, 34, 2833–2840. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.