Abstract

22q deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS) is most often correlated prenatally with congenital heart disease and or cleft palate. The extracardiac fetal phenotype associated with 22q11.2DS is not well described. We sought to review both the fetal cardiac and extracardiac findings associated with a cohort of cases ascertained prenatally, confirmed or suspected to have 22q11.2DS, born and cared for in one center. A retrospective chart review was performed on a total of 42 cases with confirmed 22q11.2DS to obtain prenatal findings, perinatal outcomes and diagnostic confirmation. The diagnosis was confirmed prenatally in 67% (28/42) and postnatally in 33% (14/42). The majority (81%) were associated with the standard LCR22A-LCR22D deletion. 95% (40/42) of fetuses were prenatally diagnosed with congenital heart disease. Extracardiac findings were noted in 90% (38/42) of cases. Additional findings involved the central nervous system (38%), gastrointestinal (14%), genitourinary (16.6%), pulmonary (7%), skeletal (19%), facial dysmorphism (21%), small/hypoplastic thymus (26%), and polyhydramnios (30%). One patient was diagnosed prenatally with a bilateral cleft lip and cleft palate. No fetus was diagnosed with intrauterine growth restriction. The average gestational age at delivery was 38 weeks and average birth weight was 3,105 grams. Sixty-two percentage were delivered vaginally and there were no fetal demises. A diagnosis of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome should be considered in all cases of prenatally diagnosed congenital heart disease, particularly when it is not isolated. Microarray is warranted in all cases of structural abnormalities diagnosed prenatally. Prenatal diagnosis of 22q11.2 syndrome can be used to counsel expectant parents regarding pregnancy outcome and guide neonatal management.

Keywords: 22q11 deletion syndrome, DiGeorge syndrome, microdeletion syndrome, prenatal diagnosis

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS) remains one of the most common and well-described microdeletion syndromes, with a broad reported prevalence between 1 in 2,000 and 6,000 live births (Bassett et al., 2011). Currently, the most well documented prenatal phenotype associated with 22q11.2DS is congenital heart disease, specifically right-sided conotruncal anomalies. Additional associations include cleft lip/palate, as well as fetal growth restriction (Noel et al., 2014). Literature addressing the sonographic extracardiac markers is lacking. A recent study of fetuses with structural anomalies independent of cardiac defects found that 1 in 992 fetuses were affected with 22q11.2DS, further validating the need for a better understanding of the fetal phenotype.2 Furthermore, many studies addressing the fetal phenotype of 22q11.2DS rely on autopsy and pathology data to assist in analysis which is a powerful tool to understand the associated congenital anomalies but does not serve as a guideline for fetal markers that can be assessed via prenatal imaging. There is also very little data available regarding obstetric outcomes and perinatal management of pregnancies complicated by a fetus with 22q11.2DS. The aim of this study was to describe the sonographic findings, perinatal outcomes and pregnancy management in a cohort of cases with a confirmed 22q11.2DS born and cared for in one center.

2 ∣. PATIENTS AND METHODS

A retrospective medical record review was performed on cases that were evaluated prenatally and confirmed to have a 22q11.2 deletion either pre or postnatally with ongoing neonatal care in our institution from June 2008 through May 2017. Mothers were evaluated through the Center for Fetal Diagnosis and Treatment (CFDT) due to identified fetal structural abnormalities and received ongoing prenatal care and delivered in the Special Delivery Unit (SDU) at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). Families received genetic counseling pre and postnatally. Additionally all families met with a reproductive geneticist during their evaluations in the CFDT. For those with confirmed prenatal diagnoses, families also had the opportunity to meet with the clinical genetics specialists at the 22q and You Center at CHOP during the pregnancy to establish a multidisciplinary neonatal care plan. Neonates received ongoing care through the 22q and You Center.

Maternal and neonatal charts were reviewed to extract prenatal diagnostic findings by system, gestational age at delivery, mode of delivery, immediate neonatal outcomes, and demographic data. Cases were confirmed either prenatally or postnatally using FISH probes, Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification (MLPA), array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH), or single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays. Cases were detected by searching through the CFDT database and the 22q and You Center database for patients with known 22q11.2 DS. Individuals who were born in the SDU and had prenatal comprehensive evaluations in the CFDT were included in the study. Descriptive statistical analysis was performed.

3 ∣. RESULTS

Forty-two cases of confirmed 22q11.2DS were identified with prenatal imaging, obstetric, and neonatal outcomes data available. Of those, 43% (18/42) were female and 57% (24/42) were male. Ethnicity was reported as Caucasian in 69%, Hispanic in 14%, African American/ Caucasian in 4%, African American in 3%, Asian Indian in 7%, and other in 2%.

4 ∣. GENOTYPE

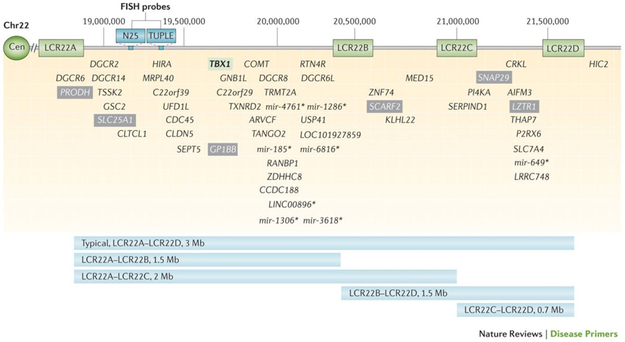

The diagnosis was confirmed prenatally in 67% (28/42) and postnatally in 33% (14/42). The potential differential diagnoses, including 22q11.2DS, were discussed during prenatal counseling in all cases. All families with a postnatal diagnosis were offered amniocentesis prenatally but declined. The majority (81%) were confirmed to have a standard LCR22A-LCR22D deletion, of which 65% were diagnosed prenatally and 35% were diagnosed postnatally. Coincidentally, two of the three cases with proximal atypical nested LCR22A-LCR22B deletions (7%), that include the N25 and TUPLE FISH probes and the important developmental gene TBX1, were detected postnatally and those with distal atypical nested LCR22C-LCR22D deletions (5%) were detected prenatally. Low copy regions and genes within the 3Mb are documented in Figure 1, which was used with permission from (Mcdonald-Mcginn et al., 2015). Three individuals were diagnosed via FISH, and thus the exact size of the deletion remains unknown. Deletion size, timing of diagnosis, and associated findings are presented in Table 1. Three individuals were identified via FISH, all of which were identified prenatally. All three had cardiac anomalies as well as extracardiac findings that included skeletal anomalies (67%), central nervous system (CNS) anomalies (33%), thymus hypoplasia (33%), and polyhydramnios (33%).

FIGURE 1.

Low copy repeats and genes within the 22q11.2 deletion region. Graphic representation of the typical 3Mb deletion including the most common LCR22A-LC22D deletion as well as atypical nested deletions and the critical gene elements within each region. Figure used with permission from McDonald-McGinn et al. (2015) [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

TABLE 1.

Deletion size and associated ultrasound detected clinical findings

| Cardiac | CNS | Skeletal | GI | GU | Pulmonary | Facial | Thymus | Polyhydramnios | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-D (2.5Mb) Prenatal 65% (22/34) | 19/22 (86%) | 11/22 (50%) | 5/22 (23%) | 3/22 (14%) | 4/22 (18%) | 0/22 (0%) | 6/22 (27%) | 8/22 (36%) | 8/22(36%) |

| A-D (2.5Mb) Postnatal 35% (12/34) | 12/12 (100%) | 3/12 (25%) | 1/12 (8%) | 0/12 (0%) | 3/12 (25%) | 2/12 (17%) | 0/12 (0%) | 1/12 (8%) | 2/12 (17%) |

| A-B (1.5Mb) Prenatal 33% (1/3) | 1/1 (100%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 1/1 (100%) | 0/1 (0%) |

| A-B (1.5Mb) Postnatal 67% (2/3) | 2/2 (100%) | 1/2 (50%) | 0/2 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 1/2 (50%) | 2/2 (100%) | 0/2(0%) | 1/2 (50%) |

| C-D (.7Mb) Prenatal 100% (2/2) | 2/2(100%) | 0/2(0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 1/2 (50%) | 0/2 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) |

CNS = central nervous system; GI = gastrointestinal; GU = genitourinary.

Screening tests, such as non-invasive prenatal screening (NIPS), have become a popular method to screen for 22q11.2 DS. In our cohort, 22 of 42 patients had pregnancies before NIPS was a routinely available screen. Of the mothers who had the option to pursue NIPS, 10 chose not to pursue screening, 9 of which had a prenatally confirmed diagnosis by amniocentesis. Of the remaining 10 mothers who did pursue NIPS, five were found to be “high risk.” All five of those fetus’ had A-D deletions. Two mothers had low risk NIPS results and both of those fetus’ had A-D deletions. Three had NIPS that did not include analysis of microdeletions, therefore 22q11.2DS was not evaluated for. Of those with high risk NIPS results, four (80%) went on to have prenatal diagnostic testing via amniocentesis to confirm the results. The individual who did not have prenatal testing received NIPS results 2 weeks prior to delivery and the diagnosis was confirmed in the neonatal period.

5 ∣. SONOGRAPHIC FINDINGS BY SYSTEM

Fetal Ultrasound evaluations were performed in the second and third trimester, between 21 and 36 weeks gestation. 95% of fetuses were diagnosed with congenital heart disease. The most common specific diagnoses were tetralogy of Fallot, followed by interrupted aortic arch and truncus arteriosus (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Cardiac diagnoses associated with the fetal phenotype of 22q11.2

| Tetralogy of Fallot | 21% (9/42) |

| Tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary atresia | 21% (9/42) |

| Interrupted aortic arch | 24% (10/42) |

| Truncus arteriosus | 17% (7/42) |

| VSD | 7% (3/42) |

| Vascular ring | 5% (2/42) |

| HLHS variant | 2% (1/42) |

VSD = ventricular septal defect; HLHS = hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

Extracardiac differences were found in 90% (38/42) of cases. These findings included CNS (38%), gastrointestinal (14%), genitourinary (17%), pulmonary (7%), facial (21%), skeletal (19%), thymus abnormalities (26%), and polyhydramnios (30%). Additional findings included a single umbilical artery. Findings by system are presented in Table 3. No fetuses were diagnosed with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR).

TABLE 3.

Prenatal extracardiac findings associated with the fetal phenotype of 22q11.2

| Central nervous system | 38% (16/42) |

| Asymmetric lateral ventricles | 31% (5/16) |

| Prominent cavum septum pellucidum | 37.5% (6/16) |

| Mega cisterna magna | 12.5% (2/16) |

| Neural tube defect | 25% (4/16) |

| Gastrointestinal | 9.5% (4/42) |

| Tracheoesophageal fistula (one with associated imperforate anus) | 50% (2/4) |

| Umbilical cord hernia | 25% (1/4) |

| Umbilical Vein Varix | 25% (1/4) |

| Genitourinary | 17% (7/42) |

| Dilated renal pelves/pyelectasis | 71% (5/7) |

| Bilateral ureteocele | 14% (1/7) |

| Unilateral multicystic dysplastic kidney | 14% (1/7) |

| Pulmonary | 7% (3/42) |

| Congenital diaphragmatic hernia | 67% (2/3) |

| Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation | 33% (1/3) |

| Craniofacial dysmorphology | 21% (9/42) |

| Bilateral cleft lip/palate | 10% (1/10) |

| Small ears | 60% (6/10) |

| Micrognathia | 10% (1/10) |

| Hypotelorism | 10% (1/10) |

| Bulbous nose | 10% (1/10) |

| Skeletal | 19% (8/42) |

| Bilateral talipes | 25% (2/8) |

| Anomalous vertebrae | 50% (4/8) |

| Pectus carinatum | 12.5% (1/8) |

| Short long bones | 12.5% (1/8) |

| Small/hypoplastic thymus | 26% (11/42) |

| Polyhydramnios | 31% (13/42) |

| Single umbilical artery | 2% (1/42) |

Cranial dysmorphology represents nine individual cases. One case had both hypertelorism and small ears.

6 ∣. OBSTETRIC AND PERINATAL OUTCOME

The majority of pregnancies were conceived naturally (93%) and the remaining 7% were conceived using in vitro fertilization. Mothers delivered vaginally in 64% (27/42) of cases. Thirty-six percentage of mothers delivered via cesarean. Of those, 73% were primary cesarean deliveries and 27% were repeat cesarean deliveries. The average gestational age at delivery was 38.8 weeks with a range of 30.6–40 weeks. The average birthweight was 3,105 g with a range of 1480–4650 g. There were no stillbirths in the cohort. There were three infant deaths (9%) at 7 weeks, 4 and 7 months of age. All three infants had multiple congenital anomalies including complex congenital heart disease and succumbed secondary to their structural malformations.

7 ∣. DISCUSSION

Cardiac disease remains the most striking sonographic feature to suggest an underlying prenatal diagnosis of 22q11.2DS. In our series, nearly all fetuses (95%) were affected with congenital heart disease. This is similar to other series of prenatally diagnosed 22q11.2DS reporting 76–100% associated cardiac abnormalities (Table 4). (Bassett et al., 2011; Besseau-Ayasse et al., 2014; Boudjemline et al., 2001; Bretelle et al., 2010; Grati et al., 2015; McDonald-McGinn et al., 2015; Noel et al., 2014; Volpe et al., 2003). The most frequent category of cardiac disease associated with 22q11.2 deletion is conotruncal defects. The current study demonstrated a consistent theme of identifying conotruncal defects prenatally (Bassett et al., 2011; Besseau-Ayasse et al., 2014; Boudjemline et al., 2001; Bretelle et al., 2010; Grati et al., 2015; McDonald-McGinn et al., 2015; Noel et al., 2014; Volpe et al., 2003). Interrupted aortic arch, type B tends to hold the strongest association (45–50%), followed by truncus arteriosus (35%) and tetrology of Fallot (10–20%) (Boudjemline et al., 2001; McDonald-McGinn et al, 2015; Noel et al., 2014). While our study was enriched for cases of tetralogy of Fallot (43%), we also observed a significant rate of interrupted aortic arch (24%), and truncus arteriosus (17%). If any of these cardiac defects are diagnosed prenatally, 22q11.2DS must be considered as a differential diagnosis and included in parental counseling. While the majority of congenital heart defects are initially detected on routine mid-trimester anatomy scan, follow-up with fetal echocardiogram and consultation with a maternal-fetal medicine specialist or pediatric cardiologist remains critical in best classifying and creating a postnatal treatment plan to maximize outcome.

TABLE 4.

Literature review of fetal 22q11 phenotype

| N | Avg deletion size | Cardiac | CNS | Skeletal | GI | Pulmonary | GU | Facial | Thymus | Amniotic fluid differences |

IUGR | Livebirth | Other clinical findings |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current study | 42 | 80% LC22A-LC22D | 40(95%%) | 16 (38%) | 8 (19%) | 4 (9.5%) | 3 (7%) | 7 (17%) | 9 (21%) | 11 (26%) | 13 (31%) | 0% | 42 (100%) | SUA 1 (3%) |

| Besseau-Ayasse et al. (2014) | 272 | 93% FISH | 228 (83%) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 25 (11%) | 16 (7%) | 10 (4%) | 25 (9.2%) | n/a | 67 (25%) | Increased NT 20 (8.7%) |

| Noel et al. (2014) | 74 | 77% FISH | 56 (76%) | 4 (5%) | 2 (2.7%) | 2 (2.7%) | n/a | 14 (19%) | 3 (4%) | 2 (2.7%) | 11 (15%) | 6 (8%) | 1 (1.35%) | Increased NT 11 (15%) |

| Bretelle et al. (2010) | 8 | 100% FISH | 8 (100%) | n/a | 2 (25%) | n/a | n/a | 1 (12.5%) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 0 | n/a |

| Volpe et al (2003) | 28 | 100% FISH | 28 (100%) | 2 (7%) | n/a | 3 (11%) | n/a | 4 (14%) | n/a | n/a | n/a | 7 (25%) | 17 (61%) | n/a |

| Boudjemline et al. (2001) | 54 | 100% FISH | 54 (100%) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 16 (29.8%) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 13 (24%) | n/a |

CNS = central nervous system; GI = gastrointestinal; GU = genitourinary; IUGR = intrauterine growth restriction.

Much is known regarding 22q11.2DS and congenital heart disease. However, the extracardiac fetal phenotype associated with 22q11.2DS is not well described and is limited by reporting method. Cleft lip and palate are frequently thought of as prenatal markers of 22q11.2DS, however, less than 10% of pediatric patients exhibit overt cleft palate and only 1–2% have cleft lip (Bassett et al., 2011; McDonald-McGinn et al., 2015; Noel et al., 2014). In our series, only one patient exhibited these findings demonstrating that while this is an important indication for prenatal microarray there are more suggestive extracardiac findings associated with 22q11.2DS.

Additionally, there was no growth restriction identified in our cohort. Detailed anatomic evaluation is warranted in any situation where a fetal abnormality is identified, particularly a cardiac anomaly, as evidenced by the varied extracardiac findings in our series.

Often evaluated postnatally as a main feature of 22q11.2DS in conjunction with cardiac disease is thymus aplasia or hypoplasia. Few prenatal series, including our own, comment on the sonographic assessment of the thymus. In this study 26% of cases had documented absence or hypoplasia of the thymus. However, thymus measurement was not routinely documented in all cases and this finding may be underrepresented. Absent and hypoplastic thymus has previously been reported to be present in prenatal series in a very wide range from 2.7% (Noel et al., 2014) of cases to 92% of cases (Chaoui et al., 2002; Chaoui, Heling, Sarut Lopez, Thiel, & Karl, 2011; Noel et al., 2014). However, there have not been well documented standards of measurement. Chauoi et al. described measuring the fetal thymus after 15 weeks gestation using the “three vessel view” for best visualization (Chaoui et al., 2002,2011). The fetal thymus is well developed by this gestational age and can be identified on ultrasound by looking at a cross sectional plane of the chest between the fetal lungs and great vessels (Chaoui et al., 2002). In using this method researchers identified aplasia or hypoplasia of the thymus as a sonographic marker of 22q11.2DS with a positive predictive valve of 81.8%, sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 98.5%. Prospective standardized measurement of the fetal thymus is an important next step in identifying if this can be a major fetal marker for the prenatal diagnosis of 22q11.2DS.

CNS anomalies can also be identified through second trimester ultrasound. Neural tube defects have been an associated prenatal finding in 22q11.2DS in many case studies, though typically are reported in conjunction with congenital heart disease (Davidson, Khandelwal, & Punnett, 1997; Nickel & Magenis, 1996; Nickel et al., 1994). Here we report four neural tube defects, three in the context of congenital heart disease and one as an isolated finding, demonstrating that testing for 22q11.2DS should be offered in this setting. We believe this study presents the first to discuss asymmetric ventriculomegaly as an ultrasound marker for 22q11 deletion, despite the fact that asymmetric ventriculomegaly is a fairly common prenatal finding. 22q11.2DS should be considered in the differential diagnoses when this is identified. Dilated cavum septum pellucidum has been recently reported as a potential fetal marker for 22q11.2DS. In a 2016 study, researchers identified dilated cavum septum pellucidum, above 95% for gestational age, in over 67% of their cohort of 37 fetal cases (Chaoui et al., 2016).

Skeletal anomalies have been reported infrequently as a rare association with 22q11.2DS. We report skeletal findings in 19% of our cohort that include anomalous vertebrae (4/8) and bilateral talipes (2/8). In a study of 108 patients with 22q11.2DS, 36% had a skeletal anomaly including these two findings (Ming et al., 1997). Bilateral talipes has also been noted in many multicenter prenatal case series, both with and without mention of congenital heart disease, proving that it is an important and often overlooked association with the condition.

In the present study, pyelectasis was the most common genitourinary finding. We additionally report an individual who did not have congenital heart disease, but had unilateral multicystic dysplastic kidney and enlarged cavum septum pellucidum. This further highlights the importance of considering 22q11.2DS in the differential diagnosis of cases with seemingly isolated findings. Prior studies have described uterine or vaginal agenesis, hypospadias, renal agenesis, and dysplastic kidneys as prenatal findings (Ming et al., 1997; Noel et al., 2014; Sundaram et al., 2007). Recently, the CRKL gene, located between the LCR22C-LCR22D regions, has been described as a critical gene for congenital kidney and urinary tract anomalies in those with 22q11.2DS. Haploinsufficiency of this gene may contribute to abnormal kidney development and thus lends further support for considering this condition in the context of congenital renal findings (Lopez-Rivera et al., 2017).

Gastrointestinal anomalies were identified in 9% of our cohort that included two cases of tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) (one associated with imperforate anus) and one umbilical cord hernia and one umbilical vein verix. Only one case of abdominal wall defect associated with 22q11.2DS, such as umbilical cord hernia, has been described (Strenge, Kujat, Zelante, & Froster, 2006). Rarely has TEF been detected prenatally (Boudjemline et al., 2001; Sundaram et al., 2007). These diagnoses cause significant impact to pediatric care, as suspected TEF can also present as laryngeal web or sublglottic stenosis which at times requires neonatal interventions as significant at trachesotomy. Understanding the prenatal findings to allow transition of care to pediatric specialists can significantly improve outcome in such complex cases. Prenatally diagnosed cases of TEF that are described in conjunction with heart disease may be underrepresented due to misdiagnosis of VACTERL or CHARGE syndrome. Other findings that are often thought to be associated with VACTERL association but were also noted in this study were hemivertebrae, imperforate anus and short long bones, lending further importance to the utility of microarray in this setting which should be included in the analysis of this condition.

Pulmonary malformations were present in 7% of our cohort and included two cases of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) and one case of congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM). CDH is gaining attention in its association, most notably in a recent 2016 publication identifying CDH in 0.8% of a 1,246 22q11.2DS patient population (Unolt et al., 2017). Of note, both cases of CDH described in the current cohort were associated with a vascular ring. As far as we are aware, the association between CPAM and 22q11.2DS reported here is a novel finding.

Facial dysmorphology can be difficult to ascertain prenatally, but may become easier with the improvement of 3D ultrasound. Facial dysmorphology was identified in 21% (9/42) of our cohort. One fetus displayed multiple facial differences including both hypertelorism and small ears, though with the advent of better technology this may become a more common finding. Ear length measuring <10 percentile for gestational age should be considered a marker to help increase suspicion. Ear size can be measured in the mid-trimester at the 18–20 week evaluation and has been well a described postnatal feature (Bassett et al., 2011; Mcdonald-McGinn et al., 2015). Small ears were seen in 14% (6/42) of cases.

Polyhydramnios is a very nonspecific prenatal finding. We would advocate that in the context of identifying polyhydramnios in association with any additional fetal findings, the differential should include the possibility of an underlying diagnosis of 22q11.2DS. The presence of polyhydramnios may be the fetal manifestation of the associated palatal, feeding, and swallowing differences. Furthermore, polyhydramnios may be associated with pregnancy complications including preterm labor and maternal discomfort, and requires further monitoring.

Perinatal management for pregnancies complicated by a fetal diagnosis of 22q11.2DS is not well described. Routine obstetric management was generally followed for our patients. In our series we did not identify cases of fetal growth restriction or in utero demise. We routinely perform interval growth scans for any pregnancy complicated by a structural abnormality, which would remain appropriate in this setting. In addition, when polyhydramnios is identified, patients are seen more frequently for follow-up ultrasound and amniotic fluid assessment depending upon maternal symptoms. Intrauterine fetal demise with a diagnosis of 22q11.2DS has been reported in other series (Besseau-Ayasse et al., 2014; Boudjemline et al., 2001; Noel et al., 2014; Volpe et al., 2003). Specifically, the two cases of IUFD in the Volpe series were associated with IUGR (Volpe et al., 2003). Currently, there are no recommendations regarding antenatal surveillance in cases of fetal 22q11.2DS. Further studies regarding antenatal surveillance in cases of fetal 22q11.2DS are warranted. At this point, it appears that antenatal surveillance should be reserved for cases with IUGR or other concerning findings.

Screening tests such as NIPS are being offered to high and low risk pregnancies and now many of them involve screening for 22q11.2DS. In our cohort in which NIPS would have been available and maternal option was to pursue screening, the result was reported high risk for 22q11.2DS 50% of the time. All of the individuals who had NIPS that included 22q11.2DS analysis had LCR22A-LCR22D mutations, which in theory should be able to be detected by this methodology. Interestingly, of the ten individuals who had NIPS all but three chose to have amniocentesis regardless of their results. While NIPS was able to make accurate diagnoses for some patients it is difficult to postulate how this information impacted the patient's decision regarding invasive testing in this population. Further studies to address how NIPS is used and perceived for low risk populations are needed to understand how these test results impact clinical care and psychological well-being for parents.

In regards to diagnostic testing, microarray analysis remains the most sensitive and appropriate testing for a fetus with any structural malformation. Additionally, microarray analysis is supported by both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics as a tier one test in evaluating a fetus with structural anomalies (Committee Opinion No. 682, Committee on Genetics and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, 2016). In our study, FISH testing alone would have missed at least two cases of 22q11.2DS. The use of microarray analysis in the context of a congenital anomaly is important as it may reveal atypical associations with 22q11.2DS and continue to expand the fetal phenotype. Better defining the extracardiac prenatal associations will aid in understanding the true prevalence of disease as well as raise awareness among those diagnosing and treating these patients.

Although this is a large cohort of 22q11.2DS fetuses evaluated and delivered in one center, the study has many weaknesses. The manner in which the cohort was obtained required that the diagnosis was confirmed and patients cared for not only through the CFDT/SDU, but also the 22q and You Center. As such, those fetuses identified with anomalies with parental decision for termination prior to confirmation of the diagnosis of 22q11.2DS would have been excluded. This group may have represented a subset of patients with more severe phenotypes. In addition, fetal demise could have also occurred prior to a confirmation of a 22q11.2 DS diagnosis, and those patients would have also been lost. Clearly, a large prospective study including standardized ultrasound evaluation is needed to analyze prenatal findings and fetal outcomes in cases of prenatally diagnosed or suspected 22q11.2 DS.

Perhaps the largest differentiating factor about this study is the continuity of care from prenatal diagnosis to pediatric management. Through diagnosis and delivery, CFDT patients were able to prenatally access multidisciplinary care in one center. A crucial aspect of this care is education; not only about the prenatal and neonatal outcomes but also the adolescent and adult manifestations of 22q11.2DS including psychiatric disease and neurobehavioral outcomes. With earlier awareness of both the physical and mental aspects of this condition families are able to establish appropriate pediatric care teams to maximize their child's success. Access to such care has been shown to improve clinical outcomes, as we could provide appropriate anticipatory care and early diagnosis for neonatal complications such as hypocalcemia and immune dysfunction which can present subtlety but cause irreversible consequences (Bassett et al., 2011). While seeking care at a multidisciplinary center with fetal-neonatal transition availability is an ideal scenario, when that cannot be achieved educating the obstetrical and NICU team on the neonatal findings associated with 22q11.2DS is crucial to optimize the outcome for these children.

REFERENCES

- Bassett AS, McDonald-McGinn DM, Devriendt K, Digilio MC, Goldenberg P, Habel A, … Vorstman J (2011). Practical guidelines for managing patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. The Journal of Pediatrics, 159(2), 332–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besseau-Ayasse J, Violle-Poirsier C, Bazin A, Gruchy N, Moncla A, Girard F, … Vialard F (2014). A French collaborative survey of 272 fetuses with 22q11.2 deletion: Ultrasound findings, fetal autopsies and pregnancy outcomes. Prenatal Diagnosis, 34(5), 424–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudjemline Y, Fermont L, Le Bidois J, Lyonnet S, Sidi D, & Bonnet D (2001). Prevalence of 22q11 deletion in fetuses with conotruncal cardiac defects: A 6-year prospective study. Journal of Pediatrics, 138(4), 520–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretelle F, Beyer L, Pellissier MC, Missirian C, Sigaudy S, Gamerre M, … Marpeau L (2010). Prenatal and postnatal diagnosis of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. European Journal of Medical Genetics, 53(6), 367–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaoui R, Heling KS, Sarut Lopez A, Thiel G, & Karl K (2011). The thymic-thoracic ratio in fetal heart defects: A simple way to identify fetuses at high risk for microdeletion 22q11. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 37(4), 397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaoui R, Heling K-S, Zhao Y, Sinkovskaya E, Abuhamad A, & Karl K (2016). Dilated cavum septi pellucidi in fetuses with microdeletion 22q11. Prenatal Diagnosis, 36(10), 911–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaoui R, Kalache KD, Heling KS, Tennstedt C, Bommer C, & Korner H (2002). Absent or hypoplastic thymus on ultrasound: A marker for dele- tion 22q11.2 in fetal cardiac defects. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 20(6), 546–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Genetics and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. (2016). Committee Opinion No. 682. Microarrays and next-generation sequencing technology: The use of advanced genetic diagnostic tools in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 128, e262–e268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson A, Khandelwal M, & Punnett HH (1997). Prenatal diagnosis of the 22q11 deletion syndrome. Prenatal Diagnosis, 17(4), 380–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grati FR, Molina Gomes D, Ferreira JC, Dupont C, Alesi V, Gouas L, … Vialard F (2015). Prevalence of recurrent pathogenic microdeletions and microduplications in over 9500 pregnancies. Prenatal Diagnosis, 35(8), 801–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Rivera E, Liu YP, Verbitsky M, Anderson BR, Capone VP, Otto EA, … Sanna-Cherchi S (2017). Genetic drivers of kidney defects in DiGeorge sydnrome. New England Journal of Medicine, 376(8), 742–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald-McGinn DM, Sullivan KE, Marino B, Philip N, Swillen A, Vorstman JAS, … Bassett AS (2015). 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 1, 15071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming JE, McDonald-Mcginn DM, Megerian T, Driscoll D, Roy Elias E, Russell B, … Zackai E (1997). Skeletal anomalies and deformities in patients with deletions of 22q11. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 72(2), 210–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel RE, & Magenis RE (1996). Neural tube defects and deletions of 22q11. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 66(1), 25–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel RE, Pillers DA, Merkens M, Magenis RE, Driscoll DA, Emanuel BS, & Zonana J (1994). Velo-cardio-facial syndrome and DiGeorge sequence with meningomyelocele and deletions of the 22q11 region. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 52(4), 445–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel AC, Pelluard F, Delezoide AL, Devisme L, Loeuillet L, Leroy B, … Gaillard D (2014). Fetal phenotype associated with the 22q11 deletion. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 164(11), 2724–2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strenge S, Kujat A, Zelante L, & Froster UG (2006). A microdeletion 22q11.2 can resemble Shprintzen-Goldberg omphalocele syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 140A(24), 2838–2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram UT, McDonald-McGinn DM, Huff D, Emanuel BS, Zackai EH, Driscoll DA, & Bodurtha J (2007). Primary amenorrhea and absent uterus in the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 143A(17), 2016–2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unolt M, DiCairano L, Schlechtweg K, Barry J, Howell L, Kasperski S, … McDonald-McGinn DM (2017). Congenital diaphragmatic hernia in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 173(1), 135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe P, Marasini M, Caruso G, Marzullo A, Buonadonna AL, Arciprete P, … Gentile M (2003). 22q11 deletions in fetuses with malformations of the outflow tracts or interruption of the aortic arch: Impact of additional ultrasound signs. Prenatal Diagnosis, 23, 752–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]