Abstract

Rationale: Telemedicine is an increasingly common care delivery strategy in the ICU. However, ICU telemedicine programs vary widely in their clinical effectiveness, with some studies showing a large mortality benefit and others showing no benefit or even harm.

Objectives: To identify the organizational factors associated with ICU telemedicine effectiveness.

Methods: We performed a focused ethnographic evaluation of 10 ICU telemedicine programs using site visits, interviews, and focus groups in both facilities providing remote care and the target ICUs. Programs were selected based on their change in risk-adjusted mortality after adoption (decreased mortality, no change in mortality, and increased mortality). We used a constant comparative approach to guide data collection and analysis.

Measurements and Main Results: We conducted 460 hours of direct observation, 222 interviews, and 18 focus groups across six telemedicine facilities and 10 target ICUs. Data analysis revealed three domains that influence ICU telemedicine effectiveness: 1) leadership (i.e., the decisions related to the role of the telemedicine, conflict resolution, and relationship building), 2) perceived value (i.e., expectations of availability and impact, staff satisfaction, and understanding of operations), and 3) organizational characteristics (i.e., staffing models, allowed involvement of the telemedicine unit, and new hire orientation). In the most effective telemedicine programs these factors led to services that are viewed as appropriate, integrated, responsive, and consistent.

Conclusions: The effectiveness of ICU telemedicine programs may be influenced by several potentially modifiable factors within the domains of leadership, perceived value, and organizational structure.

Keywords: critical care, telemedicine, mechanical ventilation

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

ICU telemedicine uses audiovisual technology to remotely monitor and care for critically ill patients from a central location. ICU telemedicine programs vary widely in their impact on patient mortality with little empirical data to guide clinicians in how to use telemedicine most effectively.

What This Study Adds to the Field

In an ethnographic evaluation of U.S. ICU telemedicine programs, we found that the effectiveness of telemedicine is influenced by the interaction of factors within three key domains: leadership of both the target ICU and the facility providing the remote care, the perceived value of telemedicine by front-line care providers, and the organizational characteristics of the telemedicine program. Optimizing these domains may increase the likelihood that telemedicine will lead to improvements in ICU outcomes.

Treatment in an ICU staffed by trained intensivist physicians improves survival in critically ill patients (1). However, many critically ill patients lack access to this level of critical care (2). ICU telemedicine is a technology-driven approach to critical care delivery specifically designed to address this problem (3). Using ICU telemedicine, intensivist physicians and nurses at regional centers of excellence can monitor and treat patients from a centralized, geographically distant location, potentially improving the overall quality of care (4). However, published studies of ICU telemedicine show mixed results, with some studies showing a large mortality benefit after the introduction of ICU telemedicine and others showing no benefit or even harm (5, 6).

At present, there is little understanding about why some ICU telemedicine programs lower mortality and others do not (7). As a consequence, clinicians have little guidance about how to best use this technology (8). We sought to fill this knowledge gap by identifying the organizational factors associated with ICU telemedicine effectiveness using qualitative analysis of in-depth site visits at ICU telemedicine programs and in-person interviews with a broad range of critical care providers. Qualitative methods are ideally suited to generate a comprehensive description of a phenomenon within a sociocultural context, particularly for complex phenomena, such as ICU telemedicine (9). Our goal was to develop a framework for effective ICU telemedicine delivery that could be used to improve existing ICU telemedicine programs and ensure that future programs are adopted in ways that are most likely to lead to lower mortality for critically ill patients.

Methods

Study Design

We performed a focused ethnographic study of ICU telemedicine programs in U.S. hospitals. The complete study methods are available elsewhere (10). Briefly, we used a positive/negative deviance design in which we first categorized hospitals based on their change in risk-adjusted mortality after adoption of ICU telemedicine as calculated in a previous study (6). We then visited programs with a statistically significant decrease in mortality after adoption, programs with a statistically significant increase in mortality after adoption, and programs with no change in mortality after adoption, allowing us to compare and contrast practices across programs (11). We defined telemedicine programs as the dyad of the facility providing remote care (which we henceforth refer to as the “telemedicine facility”) and the target ICU. In addition to changes in mortality, we selected programs to maximize diversity in geographic location, size, and academic status. We restricted the study to programs that provided continuous ICU telemedicine services from a centralized location, because this is the predominant model (12).

Data collection and analyses were theoretically guided by an extension of the technology acceptance model proposed by Venkatesh and Davis (13), which holds that technology adoption is influenced by the technology’s perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use; and that perceived usefulness is in turn influenced by broader sociologic constructs including subjective norms about the contextual value of the related behaviors, the voluntariness of use, and the user’s individualized image of themselves in relation to the technology. We complemented this theory with insights from the theory of organizational readiness to change, which emphasizes the role of management in readying organizations to implement new processes (14).

Data Collection

At each enrolled program, we performed a 4-day in-person site visit during which either three or four investigators visited both the telemedicine facility and their target ICUs. Brief, intense site visits are in keeping with a “focused ethnography” approach and reflect the applied goal of our project (15). During each observation period, we placed at least two researchers in the ICU and at least one researcher in the telemedicine facility, enabling us to observe both sides of a given interaction. When possible, visits occurred during weekdays and weekends, and daytime and nighttime hours.

During the visits, we collected four types of ethnographic data: 1) direct observations of clinical care; 2) semistructured interviews with program leadership and care providers (e.g., intensivist physicians, nonintensivist physicians, and nurses); 3) focus groups of care providers; and 4) collection of artifacts, such as written care protocols and standard operating procedures. Multiple data collection methods were used as a triangulation strategy to increase the rigor of our results (16). Interview and focus group guides were developed from expert consensus and piloted before use. All interviews and focus groups were digitally audio recorded; participants provided written consent and were offered financial compensation for their participation.

Data Analysis

Thematic content analysis was performed concurrent with data collection using a constant comparative approach (17). After each site visit, the audio recordings were transcribed and uploaded into analytic software (NVivo, QSR International), along with field notes from the site visits, and collected artifacts. To inform preliminary analysis and refine data collection, the site visit team discussed new and recurring themes via telephone with the other investigators midway through each site visit. Member checking was done by reviewing preliminary program-specific findings with representatives from each program, ensuring that our interpretations were consistent with their understanding.

A thematic codebook was then developed through iterative coding and discussion. The codebook was focused around identified beneficial care practices, which we defined as practices that were either common across sites with decreased mortality after adoption or consistently identified by care providers as having the potential to improve clinical outcomes. In developing the codebook, we attempted to exploit our deliberative sampling frame, which included programs with varying changes in mortality after adoption. Given the time lag of 4–12 years between adoption of telemedicine and our site visits, we also considered the possibility that some programs had changed their practices over time, such that all programs had the potential for beneficial and nonbeneficial care practices. When identifying beneficial care practices at programs without decreased mortality after adoption, we were careful to ensure that such practices had been adopted after the selection evaluation period and that they were also present at programs that did observe decreased mortality after adoption.

The codebook was refined until no further changes were made and intercoder percent agreement reached 90% (17). Following codebook development, the data were coded by three independent coders. Approximately 2% of each site’s data were double coded with interrater reliability assessed after completion of coding for each site.

The underlying codes were grouped into themes and subthemes and then organized into a comprehensive conceptual model of telemedicine effectiveness. Our results are presented as a summary of key themes and subthemes from the conceptual model along with supportive quotes and examples from the interviews and observations. This research was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Human Research Protection Office. Our methods and results are reported in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (see Table E1 in the online supplement) (18).

Results

Thematic saturation was reached after we visited six telemedicine facilities providing services to 10 ICUs, with the tenth site visit adding no additional themes to the codebook. These included five ICUs that experienced decreased mortality after ICU telemedicine adoption, three ICUs that experienced increased mortality after adoption, and one ICU that experienced no change in mortality after adoption. We also added one ICU that had recently adopted telemedicine for which no effectiveness data were available to determine whether or not preliminary domains identified from more established sites were salient.

Study ICUs were diverse in size (8–22 beds), location (eight urban, two rural), and academic status (four teaching, six nonteaching). In total, we conducted 460 hours of direct observation, 222 interviews, and 18 focus groups, with 30 individuals declining participation in interviews and no other overt refusals to participate. See Tables E2–E4 for additional information about data collection.

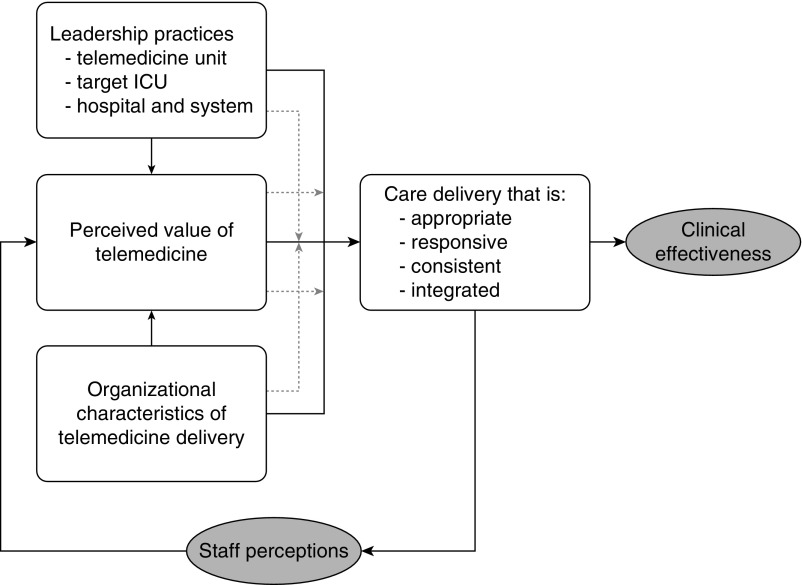

The conceptual model developed for ICU telemedicine effectiveness is shown in Figure 1. This model holds that effective telemedicine use is determined by a set of beneficial care delivery practices that are influenced by three interrelated domains: 1) leadership, 2) perceived value, and 3) organizational characteristics. These domains not only directly support the use of beneficial care practices, but also interact in ways that can increase or decrease the relative importance of the other two. These domains, and the individual beneficial care delivery practices, are first defined in Table 1 and then explained in detail. Supporting quotes and examples from direct observations for each domain are given in Table 2. Additional expanded quotes and examples are provided in Table E5.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for ICU telemedicine effectiveness. Leadership practices refer to the degree to which the ICU, telemedicine, and health system leadership affect program goals and service delivery. Perceived value refers to the acceptance and support of telemedicine on behalf of both the telemedicine providers and the ICU clinicians. Organizational characteristics of telemedicine delivery refers to the structures within which patient care takes place, including resources, staffing, workflows, and environment. The solid lines indicate direct effects between domains. The dashed lines indicate moderating effects between domains and direct effects.

Table 1.

Definitions of Key Constructs, Themes, and Subthemes

| Construct, Theme, or Subtheme | Definition |

|---|---|

| Beneficial care delivery practices | The practices either within the telemedicine facility or between the telemedicine facility and the target ICU that have the potential to positively effect clinical outcomes or alter perceptions of telemedicine by meeting expectations. |

| Appropriateness | The extent and ways in which the actions of the telemedicine facility are viewed by the ICU as clinically reasonable, within the perceived scope of practice of the ICU telemedicine, in accordance with what the primary care team would want, and aligned with the special needs of the target ICU patient population. |

| Responsiveness | The degree to which the interaction with the ICU telemedicine facility is in accordance with the perceived need (i.e., the telemedicine facility is proactive when needed, independently assessing patients and reaching out the bedside clinicians to affect care; and reactive when needed, responding to the requests of bedside clinicians). |

| Consistency | The degree to which the telemedicine facility provides the same suite of services with the same level of hospitality over time and independent of the individual clinicians working in the facility. |

| Integration | The extent to which the telemedicine facility and ICU have patterned ways of working together. Integration can refer to overlapping responsibilities, shared decision-making, or services that are the responsibility of the telemedicine facility that are relied on by the ICU. |

| Leadership | The ways in which the leadership team of the telemedicine facility, ICU, and hospital system set program goals and impact the development and implementation goals, particularly around policies, protocols, budget, and conflict management. |

| Perceived value | The level of acceptance, support, and use of telemedicine on behalf of both the telemedicine providers and the ICU clinicians, compared with the next best alternative. |

| Expectation of availability | The belief among ICU clinicians that the telemedicine facility clinicians will be otherwise unoccupied and able to interact when called on. |

| Expectation of impact | The belief among ICU clinicians that the telemedicine facility clinicians will possess the necessary experience and expertise to provide input of value, and that that input will in turn lead to improved patient-centered outcomes. |

| Understanding of operations | The degree of understanding of the role and services provided by telemedicine on behalf of both the telemedicine clinicians and the ICU clinicians. This subdomain relates to whether ICU telemedicine is a “black box” versus an “open book” with regards to what it does and how it does it. |

| Interpersonal relationships | The presence or absence of stable, existing, interprofessional and interpersonal relationships between the telemedicine providers and the ICU providers. This domain includes issues related to prior history of working together, trust, and conflict. |

| Staff satisfaction | The degree to which telemedicine is perceived to positively impact job satisfaction and the mechanisms for affecting said satisfaction, including reducing workload and improving work–life balance. |

| Organizational characteristics | The structures within which patient care takes place. This includes resources, staffing, workflows, and environment. |

| Staffing models | Staffing levels, roles, coverage, shift changes, and assignments, within both the telemedicine facility and the ICU. |

| Protocols for engagement | Formally, the practice of designating levels of care by which the telemedicine physicians are allowed to intervene and make care decisions about the patients, as determined either by ICU policy or by individual ICU physicians. |

| Shared staff | The degree to which staff in the telemedicine facility also work or have worked in the target ICU. |

| Orientation | The processes by which new hires are oriented to the telemedicine facility. Within the telemedicine facility, this subdomain relates to how hires are trained with respect to potentially beneficial processes. Within the ICU, this subdomain relates to how hires are trained to interact with the telemedicine facility. |

Table 2.

Sample Quotes and Observations That Provide Support for the Role of the Key Themes and Subthemes within Our Conceptual Model for Telemedicine Effectiveness

| Theme or Subtheme | Examples Related to Beneficial Use of Telemedicine | Examples Related to Nonbeneficial Use of Telemedicine |

|---|---|---|

| Beneficial care delivery practices | ||

| Appropriateness | “You have to modify the support that you provide to these people, based on their location and what they have available to them.” —Multiprofessional focus group, telemedicine facility |

“I’ve seen the [telemedicine facility] get involved looking at stuff through a vacuum, not really understanding the patient’s situation or clinically what the patient looks like.” —Multiprofessional focus group, ICU |

| Responsiveness | “You don’t have to wait for a physician to call back, they’re immediate, those kind of resources are more available.” —Interview, ICU administrator |

“You get this kind of like animosity towards them because they’re really taking you away from the bedside.” —Interview, ICU nurse |

| Consistency | “[ICU clinicians] have to be able to rely on you even if it’s a really insignificant duty to you.” —Interview, ICU director |

“They provide advice to residents and nurses for patients who have changes in their vital signs. But their services are not consistent.” —Interview, ICU physician |

| Integration | “It’s so integrated that I’m not sure we would be able to separate. It’s been embedded. So I think it works because over time the bedside folks have accepted this as another tool to the care of the patient and not as an intrusion which, yes, it was seen that way in the beginning...” —Interview, telemedicine facility director |

“[The telemedicine staff] are present for multidisciplinary rounds, but they’re just present for it. I mean they’re collecting the data they need to continue to follow the measures that we follow. But they don’t participate…. They’re really just observing.” —Focus group, ICU nurse |

| Leadership | “Let the [telemedicine facility] leadership come and meet with the ICU leadership and let’s talk about what we can do to support the initiatives you’re talking about that are important to you.” —Interview, telemedicine facility director |

“If you don’t have complete and absolute buy-in from the administration, and willing to back those who are going to be implementing the [telemedicine facility] you can’t be as effective.” —Focus group, ICU and telemedicine facility physicians |

| Perceived value | ||

| Expectation of availability | “[At a prior institution] it wasn’t that we didn’t have access to critical care specialists at my other organizations, but we had to call them, and they had to try and come in. They didn’t have access to the level of monitoring or the level of information that the [telemedicine unit] does.” —Interview, ICU nurse |

“It really depended on who was the intensivist at that time if they would go back to the [telemedicine facility] and look at a patient. But if it was a critical thing you could actually ask them and they definitely would come, but it was just a lot more difficult to actually get a doctor to see you.” —Focus group, ICU nurses |

| Expectation of impact | “I think there were occasional cases where we would intervene and … help them substantially to recognize things that they had missed, or offer assistance that they might otherwise not know about….” —Interview, telemedicine facility director |

“There are issues when physicians are tired, or hurried, or don’t have time, and suddenly there’s this new burden of communication or coordination that gets imposed. They don’t understand why it’s even needed.” —Interview, telemedicine facility director |

| Understanding of operations | “Having people come here and see it makes a big difference, and I always say, ‘Bring the negatives.’ Those people that are resistant, bring them!” —Focus group, telemedicine facility |

“The charge nurses seem to be on board but then you’ll get the bedside nurses that are a little bit more—you know they have that image of us that we’re just kind of sitting there and just sitting there.” —Interview, telemedicine facility nurse |

| Interpersonal relationships | “We’ve tried to go over to the sites and actually visit with the sites so that they can see us…. It’s easier to be nasty to somebody if they don’t know who you are and they can’t see versus when it’s more face-to-face.” —Interview, telemedicine facility nurse |

“There’s a lot of people that rotate through that nobody knows. Now, when you talk to somebody you don’t know at the other end there’s always a question in your mind, like, who am I talking to?”—Interview, ICU administrator |

| Staff satisfaction | “I called over the [telemedicine facility] and I told them, you know, straight up, ‘You’re going to have to watch this patient because nobody can watch the other patient.” —Interview, ICU nurse |

“If they used us the physicians would come in the next morning, and chastise them to the point that the nurses were scared to use us.” —Interview, telemedicine facility director |

| Organizational characteristics | ||

| Staffing models | “It’s the med-surgical ICUs where our team isn’t in-house at night [that] it’s a very primary role actually at night.” —Interview, ICU and telemedicine physician |

“In our [urban] units where [intensivists are] in-house, I think it’s very secondary and very underutilized…” —Same interview as at left |

| Protocols for engagement | “The roll out was, ‘We’re going to consider that you all want to be the lowest level unless you come and tell us you want to be a higher level.’” —Interview, telemedicine facility manager |

“In [another hospital] the roll out was, ‘Here, Doctor. Here’s your sheet of your paper. Fill out your level, and return it to us.’” —Same interview as at left |

| Shared staff | “If it’s nurses that you know and trust, then I feel like our staff feels more comfortable… and it’s like there’s a sense of relief on the unit...” —Interview, ICU nurse |

“There’s some … random physicians, so it’s a little harder then to trust what they’re saying just because I’ve never worked with them.” —Interview, ICU nurse |

| Orientation | “I work pretty closely with the nurse educator up there, and I say, ‘If you have a new staff member, give me fifteen minutes with them.’” —Interview, telemedicine facility physician |

“They just kind of showed me where the button was that if you need help in the room immediately you push the button or here’s the number you call and that’s what you do.” —Interview, ICU nurse practitioner |

Beneficial Care Delivery Practices

ICU telemedicine care delivery takes place through four major activities: 1) monitoring for physiologic deterioration, 2) prompting bedside providers for specific evidence-based practices, 3) serving as a resource for expert advice and guidance, and 4) collecting performance data for later auditing and feedback. Sample quotes and observations describing these delivery forms are given in Table 3. Telemedicine programs were most effective when they tended to perform these activities in ways that were appropriate, responsive, consistent, and integrated with bedside workflows.

Table 3.

Categorization of the Forms of ICU Telemedicine Care Delivery

| Care Delivery Practices | Examples in the Form of Respondent Quotes and Observations |

|---|---|

| Monitoring for physiological deterioration | “[The patient] started to deteriorate. [The telemedicine physician] gave us orders. He made changes. We had right there in that immediate, we had an improvement, and when the physicians came in the next morning, they were like, ‘Great! That’s great that there’s improvement.’” —Interview, ICU nurse |

| Prompting bedside providers for specific evidence-based practices | The ICU telemedicine nurse checked on the status of a patient who had a spontaneous breathing trial but not a sedation vacation. “I make circles on the chart, and then I call them at the end,” she explains how she fills in her charting. “I keep looking at the head of the beds. It’s an evidence-based practice … and it works.” She continues, “See, there’s a note for the SBT. I can put a check in—like checking off.” —Observations, telemedicine facility nurse |

| Serving as a resource for expert advice and guidance | “There’s someone there full-time so you don’t feel like you’re waking someone up at home, so whereas you may be a little hesitant to call if somebody was at home taking call, I have no hesitation for calling up the [telemedicine facility] just to kind of—to pick their brain.” —Interview, ICU physician |

| Collecting performance data for later auditing and feedback | “There’s a medication algorithm for alcoholics, and for regulatory reasons we had to do some auditing…. So there was about a good three months where the [telemedicine facility] audited every [alcohol withdrawal] patient we had on the protocol.” —Interview, ICU manager |

Definition of abbreviation: SBT = spontaneous breathing trial.

These practices can be delivered in either effective or ineffective ways.

Care was considered appropriate when the clinicians in the telemedicine facility delivered needed expertise in accordance with what the bedside clinicians would have performed; and when expertise was specific to the needs of the particular ICU. In contrast, care was considered inappropriate when clinicians in the telemedicine facility did not possess necessary expertise, as when medical intensivists were asked to advise on the care of postoperative cardiac surgery patients; or provided recommendations thought to be outside the scope of practice of telemedicine.

Care was considered responsive when the telemedicine facility was proactive, seeking out care deficiencies that had been missed at the bedside, yet also appropriately reactive, being available when needed and not disrupting effective care in the target ICU. For example, a common nonbeneficial practice was when the telemedicine facility would call the ICU requesting routine documentation that was only slightly delayed, or to tell the ICU clinicians that the patient was experiencing a physiologic deterioration while the clinicians were already attending to it at the bedside.

Care was considered consistent when the telemedicine facility used the same approach every time, creating a set of shared expectations about what they would do and when. For example, at a program in which the telemedicine facility participated in daily rounds, it was most beneficial when they did so every day, with the same intensity of participation every day. In contrast, when service was inconsistent because of poorly specified workflows or stylistic differences between telemedicine providers, ICU clinicians were unclear about the role of telemedicine and disinclined to seek help.

Care was considered integrated when telemedicine workflows were embedded with ICU workflows creating customary points of interaction. The two groups tended to form one care team, with each understanding their roles and responsibilities. Examples include the telemedicine unit cosigning medications, notifying organ donation services, and monitoring quality improvement data. In contrast, when beneficial care practices were absent, the groups remained separate. Telemedicine staff were unsure of their roles and often relegated to “observer” status, performing duplicative duties and duties that are largely independent of bedside providers, such as collecting quality data without actively engaging the ICUs.

Leadership

Leadership is defined as how the various organizational managers at the telemedicine facility, ICU, and hospital system-level make decisions about the role and reach of telemedicine. Effective leadership supports beneficial care practices by determining the role for telemedicine and ensuring front-line care providers understand and realize this role in daily practice through policies, protocols, and budgetary support. For example, a common beneficial practice was when telemedicine leadership frequently meet with ICU directors to troubleshoot care practices, determine what services were working best, and mediate conflicts. In contrast, a common nonbeneficial practice was for leadership to adopt ICU telemedicine without the input and explicit assent from front-line ICU clinicians.

Perceived Value

Perceived value is defined as perceptions among front-line care providers about the ability of telemedicine to meaningfully improve the clinical outcome of critical care. When providers greatly valued telemedicine services, this directly influenced beneficial care practices by engendering frequent and proactive interactions. Perceived value is relevant on two distinct levels. The first is the level of the individual interaction: ICU providers have an expectation that each interaction will lead to immediate beneficial results. The second is the level of the program as a whole: the sum of individual interactions will lead to increased beneficial care practices and improved effectiveness. In this regard, the ICU clinician’s perceptions of telemedicine serve as a feedback loop: consistently positive interactions led to positive perceptions, which in turn increased perceived value leading to even more, and more helpful, interactions:

I have to admit, initially when they started, I didn’t think I’d use them much, and it’s amazing how many times, you know, at the beginning, you call. Because if you ever had to call a physician at the clinic, and you wait, and you wait, and you wait. Because they’re with a patient, or maybe they’re doing something else, so [ICU telemedicine] to me was like, wow, I can talk to a physician in 15 seconds, get an order, and each, it seemed like, you know, week by week, you used them a little bit more.

—Interview, ICU nurse

In contrast, in several programs, perceived value was generally absent. Typically, this was because providers believed telemedicine created extra work for them, or because telemedicine was not viewed as superior to alternative approaches to ICU organization. As a result of low perceived value, ICU clinicians would not seek out assistance, reducing consistency and integration.

Sometimes they don’t want to call [telemedicine facility] because it starts a whole, you know, sometimes they order all kinds of crap that they, you know, that you don’t want to do. Like, they give you more than what you want, or um, so I get mixed reviews on it. Not everybody likes to use it.

—Interview, ICU nurse

Perceived value has multiple subdomains, including the expectations of availability and impact, an understanding of operations, interpersonal relationships, and staff satisfaction. ICU clinicians perceive value when they have immediate access to physicians and nurses in the telemedicine facility who are able to address their needs. ICU clinicians also perceive value when they have personal relationships with the providers in the telemedicine, as might occur if they have previously worked together at the bedside or through dedicated outreach by the telemedicine facility staff.

Organizational Characteristics

Organizational characteristics are defined as the features of the telemedicine facility/target ICU dyad that govern how remote clinical care is provided and received. Subdomains include the staffing models, protocols for engagement, whether or not there are shared staff that work in both the telemedicine facility and target ICU, and the orientation of new hires.

Regarding staffing models, key factors include the hours of operation (i.e., 24 hours vs. solely at night), whether or not the telemedicine staff participate in daily multidisciplinary rounds, and the type of physician staffing in the target ICU (i.e., the presence or absence of intensivist physicians during the day and at night, and the presence or absence of residents and physicians-in-training). When staffing levels in the target ICU are low, the telemedicine providers can take a primary role, engendering effective use. When staffing levels in the target ICU are high, or the ICU telemedicine providers lack necessary expertise, then telemedicine is not used consistently.

Protocols for engagement refers to the practice of affording the telemedicine facilities varying levels of autonomy depending on the preferences of the target ICU clinicians. For example, telemedicine clinicians would be allowed to completely manage some patients, whereas for other patients, they were only allowed to help during emergencies. This practice prevents the use of beneficial care practices in two ways. First, when the telemedicine clinicians do not routinely manage patients, the telemedicine care is less frequent and less integrated. Second, when the degree of autonomy varies across ICUs (or across patients within ICUs), telemedicine clinicians become confused about the degree of autonomy they can exercise. In these scenarios, telemedicine clinicians may experience excess cognitive load leading them to “default” to low engagement levels, further reducing frequency of interactions and integration.

Regarding shared staff, respondents noted that beneficial care practices are supported when nurses and physicians work in both the telemedicine facility and the target ICU. This strategy helps to make care more appropriate and integrated. Additionally, some bedside nurses believe that, without ongoing bedside experience, their telemedicine counterparts lose touch with bedside care and cease to be helpful.

Regarding orientation, efforts to orient new hires to telemedicine consistently engendered beneficial care practices. For example, some target ICUs had new hires come to the telemedicine facility to gain an understanding of the unit’s role and processes from the outset, whereas others leveraged their communications technology and oriented new hires to telemedicine orientation remotely.

Organizational characteristics such as shared staff and orientation were particularly influential on frequency of telemedicine use. Beneficial care practices would occur when frequent interactions between the telemedicine facility and the ICU increased comfort with the technology, fostered integration, and facilitated smoother interactions.

Interaction between Domains

In addition to their direct relationship to beneficial care practices, the three domains interacted in ways that modified their overall effects. For example, in one program that did not consistently display beneficial care practices, the lack of supporting organizational practices played out in a greater need for leadership to influence more integrated care.

At academic tertiary hospitals like this..., where you have residents and you have capable intensivists and consultants and all of these resources…. Right now it is not integrated well. We have the way to communicate and connect with them, but they are not expected to be part of the essential team of management.

—Interview, ICU physician

Perceived value moderates the impact of leadership and organizational characteristics, such that in the setting of low perceived value, the leadership and organizational characteristics become more important.

The [ICU] physicians were aware that [telemedicine physicians] might be monitoring the patients. They didn’t want them providing any orders on their patients at all. Through a variety of factors that has changed…. Specifically, in large part due to an expressed desire on the part of leadership … to say we need to change that kind of a culture.

—Interview, ICU administrator

Interactions between domains were particularly salient in situations where a single telemedicine facility operated under different organizational configurations to provide care to study ICUs. These differing configurations could result in effectiveness discordance, where telemedicine from a single facility is effective in one ICU but ineffective in another. For example, one telemedicine facility provided services to a closed ICU with daytime intensivists and nighttime residents; and to a second ICU that had an open admission policy and no in-house intensivist overnight. Intensivists in neither ICU had a high perceived value of telemedicine. However, the night nurses in the ICU with lower intensity nighttime physician staffing greatly valued the access and impact of telemedicine, in part because of the efforts of leadership to promote more flexible protocols of engagement, leading to more integrated and effective use.

Discussion

More than 10% of U.S. ICUs currently employ telemedicine (19), yet, there are few data on how to use telemedicine most effectively. As noted in a consensus workshop statement developed by the four major U.S. critical care professional societies, “the true value of ICU telemedicine lies not in whether the technology exists but in how it is applied” (7). Our work provides insight into this issue by developing an empirical model for ICU telemedicine effectiveness that can aid efforts to improve existing programs and guide future adoption.

Our study adds to existing guidelines for ICU telemedicine operations put forth by the American Telemedicine Association (20). These guidelines emphasize the need for a shared vision among leadership, explicit program goals, role clarity among providers, and strong integration between the telemedicine facility and the ICU. Our study supports these guidelines both by providing a new evidentiary foundation for these recommendations, and a concrete, actionable framework for achieving them. For example, we show how consistency of use can support role clarity among providers, and how consistent expectations of availability and impact can support integrated services.

Our study also provides additional nuance not present in prior guidelines. For instance, although past work stresses the importance of interpersonal trust between providers, we describe not only the role of trust, but also ways to support trust through use that is appropriate, responsive, consistent, and integrated. Although trust can be supported by organizational practices, such as shared staffing models, effective programs engender trust, rather than the other way around.

Our study has several important implications for clinical practice. First, it provides a novel roadmap for effective adoption and evidence-based improvement, in that hospitals and clinicians can use our conceptual model to help design new programs and refine existing programs. Specific strategies derived from our results are delineated in Table 4. Second, our study can help clinical stakeholders decide whether or not to adopt ICU telemedicine in the first place. For example, if it is difficult or impossible to create the conditions for effective use that we describe, stakeholders can opt for other quality improvement initiatives, such as community outreach or regionalization (3, 21). Third, our study can help professional societies develop toolkits for telemedicine adoption (22).

Table 4.

Programmatic Strategies to Modify Care Practices to Optimize Telemedicine Effectiveness (i.e., Support Telemedicine Facility and ICU Interactions That Are Appropriate, Responsive, Consistent, and Integrated)

| Primary Domain | Strategy | Subdomains |

|---|---|---|

| Leadership | Regular in-person meetings between telemedicine and ICU leadership | Understanding of operations |

| Quality reporting both quantitatively and in the form of narrative | Expectation of impact, integration | |

| Perceived value | Telemedicine staff education related to local ICU protocols, policies, and procedures | Understanding of operations, appropriateness |

| Communication training for telemedicine staff | Expectation of impact, interpersonal relationship, consistency | |

| Standardized communication practices that support proactive interventions in times of emergencies and reactive interventions at scheduled times so as to not disrupt workflow | Expectation of availability, interpersonal relationships, staff satisfaction, understanding of operations, consistency | |

| ICU has a telemedicine “champion” to maintain engagement | Expectation of availability, expectation of impact, understanding of operations, interpersonal relationships | |

| ICU staff oriented to telemedicine facility through in-person visits | Expectation of availability, expectation of impact, understanding of operations, interpersonal relationships, orientation | |

| ICU receives regular visits from telemedicine staff through an “ambassador” program | Expectation of availability, expectation of impact, understanding of operations, interpersonal relationships | |

| Nonclinical remote interactions (i.e., education and team-building) to promote familiarity with the system | Expectation of availability, expectation of impact, understanding of operations, interpersonal relationships | |

| Messaging attending physicians with updates to prevent surprises on arrival in the morning | Interpersonal relationships, staff satisfaction, appropriate | |

| Organizational characteristics | Staffing the telemedicine facility with clinicians with expertise specific to the target ICU | Expectation of impact, staffing models, appropriateness |

| Use of two-way cameras | Interpersonal relationships | |

| Telemedicine staff attending local ICU training and in-services | Understanding of operations, interpersonal relationships, appropriateness | |

| Charting and administrative tasks performed by telemedicine staff (i.e., routine documentation, medication cosigning, and bundle audits) | Staff satisfaction, integration | |

| Telemedicine staff also work in target ICUs | Shared staff, understanding of operations | |

| ICU staff education related to telemedicine protocols, policies, and procedures | Expectation of availability, expectation of impact, understanding of operations, interpersonal relationships, orientation | |

| Flexibly staffing the telemedicine facility so that personnel can meet demand during peak times | Expectation of availability, staffing, responsiveness | |

| Telemedicine facility offers a core suite of services to each ICU with a limited and modest capacity to customization | Expectation of availability, expectation of impact, understanding of operations, interpersonal relationships, consistency | |

| Group communication when feasible (i.e., the telemedicine facility nurse and physician both communicate with the bedside nurse) | Relationships, responsiveness |

The strategies are organized by primary domain, with key subdomains listed if appropriate.

Our study also expands on the theoretical basis for technology adoption in a critical care setting. Telemedicine is more than the remote provision of critical care services. As with other disrupting technologies in health care, it is a large-scale reorganization of critical care delivery that requires careful preparation and continuous reflection (23–26). The new routines necessitated by new technology require not only changes to cognition but also changes in interpersonal behavior facilitated by widespread organizational change (26).

Our study has several limitations. We focused on the continuous care model with a centralized telemedicine facility, rather than ICU telemedicine models based on periodic consultation or models with decentralized telemedicine facilities (12). Although some of the principles we uncovered may apply to periodic, decentralized ICU applications, our results may not transfer to other settings. Similarly, given the substantial variability in critical care organization and management, our results are unlikely to apply to every ICU. Second, our study is purely qualitative. Although the nature of qualitative research makes this approach uniquely suited to the type of theory development we performed, our results may require further empirical evaluation to be actionable. Specifically, future work should attempt to quantitatively assess these domains and link them to other measures of program quality.

Despite these limitations, this study provides novel insight into the determinants of ICU telemedicine effectiveness that can guide clinicians in the use of telemedicine as a strategy to improve the quality of critical care. Our study also provides broader insight into the essential roles of context and organizational climate for technology adoption in the ICU.

Footnotes

Supported by the NIH (R01HL120980).

Author Contributions: J.M.K., K.J.R., C.C.K., L.E.A., A.E.B., J.C.F., T.B.H., M.H., and D.C.A. contributed to the study design, acquisition, and analysis of data; critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content; and gave final approval to the submitted version. J.M.K. and K.J.R. drafted the initial manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201802-0259OC on October 23, 2018

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Wilcox ME, Chong CAKY, Niven DJ, Rubenfeld GD, Rowan KM, Wunsch H, et al. Do intensivist staffing patterns influence hospital mortality following ICU admission? A systematic review and meta-analyses. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:2253–2274. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318292313a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angus DC, Shorr AF, White A, Dremsizov TT, Schmitz RJ, Kelley MA Committee on Manpower for Pulmonary and Critical Care Societies (COMPACCS) Critical care delivery in the United States: distribution of services and compliance with Leapfrog recommendations. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1016–1024. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000206105.05626.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen Y-L, Kahn JM, Angus DC. Reorganizing adult critical care delivery: the role of regionalization, telemedicine, and community outreach. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:1164–1169. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200909-1441CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lilly CM, Zubrow MT, Kempner KM, Reynolds HN, Subramanian S, Eriksson EA, et al. Society of Critical Care Medicine Tele-ICU Committee. Critical care telemedicine: evolution and state of the art. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:2429–2436. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilcox ME, Adhikari NK. The effect of telemedicine in critically ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2012;16:R127. doi: 10.1186/cc11429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kahn JM, Le TQ, Barnato AE, Hravnak M, Kuza CC, Pike F, et al. ICU telemedicine and critical care mortality: a national effectiveness study. Med Care. 2016;54:319–325. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahn JM, Hill NS, Lilly CM, Angus DC, Jacobi J, Rubenfeld GD, et al. The research agenda in ICU telemedicine: a statement from the Critical Care Societies Collaborative. Chest. 2011;140:230–238. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berenson RA, Grossman JM, November EA. Does telemonitoring of patients—the eICU—improve intensive care? Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:w937–w947. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edmondson AC, McManus SE. Methodological fit in management field research. Acad Manage Rev. 2007;32:1155–1179. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rak KJ, Kuza CC, Ashcraft LE, Morrison PK, Angus DC, Barnato AE, et al. Identifying strategies for effective telemedicine use in intensive care units: the ConnECCT study protocol. Int J Qual Methods. 2017 doi: 10.1177/1609406917733387. DOI: 10.1177/1609406917733387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Ramanadhan S, Rowe L, Nembhard IM, Krumholz HM. Research in action: using positive deviance to improve quality of health care. Implement Sci. 2009;4:25. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lilly CM, Fisher KA, Ries M, Pastores SM, Vender J, Pitts JA, et al. A national ICU telemedicine survey: validation and results. Chest. 2012;142:40–47. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venkatesh V, Davis FD. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manage Sci. 2000;46:186–204. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiner BJ. A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implement Sci. 2009;4:67. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higginbottom GMA, Pillay JJ, Boadu NY. Guidance on performing focused ethnographies with an emphais on healthcare reserach. Qual Rep. 2013;18:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shenton AK. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ Inf. 2004;22:63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernard HR. Social research methods: qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kahn JM, Cicero BD, Wallace DJ, Iwashyna TJ. Adoption of ICU telemedicine in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:362–368. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a6419f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Telemedicine Association TeleICU Practice Guidelines Work Group. Guidelines for TeleICU operation. Washington, DC: American Telemedicine Association; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahn JM, Linde-Zwirble WT, Wunsch H, Barnato AE, Iwashyna TJ, Roberts MS, et al. Potential value of regionalized intensive care for mechanically ventilated medical patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:285–291. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200708-1214OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coombs MA, Davidson JE, Nunnally ME, Wickline MA, Curtis JR. Using qualitative research to inform development of professional guidelines: a case study of the society of critical care medicine family-centered care guidelines. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:1352–1358. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellermann AL, Jones SS. What it will take to achieve the as-yet-unfulfilled promises of health information technology. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:63–68. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ray KN, Felmet KA, Hamilton MF, Kuza CC, Saladino RA, Schultz BR, et al. Clinician attitudes toward adoption of pediatric emergency telemedicine in rural hospitals. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2016;1 doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sittig DF, Singh H. A new sociotechnical model for studying health information technology in complex adaptive healthcare systems. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:i68–i74. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2010.042085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edmondson AC, Bohmer RM, Pisano GP. Disrupted routines: team learning and new technology implementation in hospitals. Adm Sci Q. 2001;46:685–716. [Google Scholar]