Abstract

Objective:

Leukocyte flux contributes to thrombus formation in deep veins under pathologic conditions, but mechanisms which inhibit venous thrombosis are incompletely understood. Ectonucleotide di(tri)phosphohydrolase 1 (ENTPD1 or Cd39), an ectoenzyme which catabolizes extracellular adenine nucleotides, is embedded on the surface of endothelial cells and leukocytes. We hypothesized that under venous stasis conditions CD39 regulates inflammation at the vein:blood interface in a murine model of deep vein thrombosis.

Approach and results:

CD39-null mice developed significantly larger venous thrombi under venous stasis, with more leukocyte recruitment compared with wild type mice. Gene expression profiling of WT and Cd39-null mice revealed 76 differentially-expressed inflammatory genes that were significantly upregulated in Cd39-deleted mice after venous thrombosis; and validation experiments confirmed high expression of several key inflammatory mediators. P-selectin, known to have proximal involvement in venous inflammatory and thrombotic events was upregulated in Cd39-null mice. Inferior vena caval ligation resulted in thrombosis and a corresponding increase in both P-selectin and VWF levels which were strikingly higher in mice lacking the Cd39 gene. These mice also manifest an increase in circulating platelet-leukocyte heteroaggregates suggesting heterotypic crosstalk between coagulation and inflammatory systems, which is amplified in the absence of CD39.

Conclusion:

These data suggest that CD39 mitigates the venous thrombo-inflammatory response to flow interruption.

Keywords: ectonucleoside tri(di)phosphohydrolase, CD39, ENTPD1, purinergic signaling, ATP, ADP, venous thrombosis, vein wall, DVT, VTE, inflammation, P-selectin, VWF

Subject codes: TOC category: basic, TOC subcategory: vascular biology, thrombosis

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and its major complication, pulmonary embolism (PE), are the third leading causes of cardiovascular death in the United States.1–3 DVT and PE, collectively referred to as venous thromboembolism, affect over 900,000 individuals and cause up to 180,000 deaths each year in the United States.1–4 In spite of the high disease burden of DVT, much of the underlying inciting and propagating causes remain unclear. A growing body of evidence supports the paradigm of intertwined roles of inflammation and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of DVT. This work examines the role of a vascular ectonucleotidase, CD39 which sits precisely at this intersection point.

Systemic inflammatory conditions such as sepsis, inflammatory bowel disease, cancer and rheumatoid arthritis are associated with an increased risk of venous thrombosis.5 Similarly, inflammation in animal models of DVT drives thrombosis by a multiplicity of mechanisms including by increasing vascular tissue factor, platelet reactivity, fibrinogen synthesis, and decreased expression of the anticoagulant thrombomodulin.6–13 Early stages of venous thrombosis in animal models are characterized by increased leukocyte and platelet recruitment, adhesion, and infiltration into the vessel wall.14–17 Activation of the vein wall, tissue factor, disturbed flow, stasis, hypoxia and activated circulating leukocytes and platelets play significant roles as triggers for thrombus formation,17–24 although the molecular mechanisms by which thrombosis occurs in DVT have not been fully elucidated.

Selectins, adhesive proteins expressed on the surface of endothelial cells (E-selectin and P-selectin), and platelets (P-selectin), are important mediators of inflammation and venous thrombosis.17, 25 Recent work has shown the role of endothelial, neutrophil, monocyte and platelet cell-cell interactions as facilitators and potentiators of venous thrombus formation and propagation.17 Although the role of platelets in venous thrombosis triggered by flow interruption is still being elucidated, platelet positioning at the thrombo-inflammatory interface suggests their active role in DVT. Von Willebrand factor (VWF), a multimeric plasma glycoprotein, is an important endothelial mediator of venous thrombosis by forming a molecular bridge between platelet glycoprotein Ib and sub-endothelial collagen under shear, thus recruiting and activating platelets on the vascular luminal surface. VWF has a critical role in venous thromboembolic disease (VTE) as evidenced by the strong relationship between elevated plasma VWF concentrations and VTE.26 More recent studies have demonstrated an overlap between common genetic variants associated with increased von Willebrand factor and those associated with VTE risk.27, 28 Additionally, multiple mouse models of DVT have demonstrated protection from thrombus formation in the absence of VWF.17, 29, 30

Though found in abundance within cells, purine nucleotides (ATP, ADP and AMP) are released into the extracellular environment upon cell activation, injury, or death.31–37 They are signaling molecules in an extensive, intercellular communication network, with central roles in modulating endothelial cell activation, thrombosis, inflammatory cell trafficking and activation, apoptosis and vasoconstriction. Vascular extracellular ATP and ADP metabolism is predominantly regulated by an ecto-apyrase (ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1, CD39), a transmembrane enzyme which catalyzes the terminal phosphohydrolysis of ATP and ADP. CD39 plays a critical role in regulation of atherosclerosis, arterial thrombosis, and inflammation.38, 39 Vascular CD39 is located on the surface of endothelial cells and leukocytes, where it tonically suppresses platelet aggregation by dissipating ADP, the chief agonist for the P2Y class of purinergic receptors on the platelet surface.40, 41 CD39 deficiency causes deleterious outcomes in various models of arterial flow disruption, such as stroke and atherosclerosis,38, 39 ischemia reperfusion injury,42, 43 and graft survival in xenograft heart transplantation.44 Previous studies have demonstrated the protective thromboregulatory function of CD39 in mice and in rats with stroke.45, 46 Through its potent ability to dissipate ATP released as an injury or danger signal, our group has shown that surface CD39 enables leukocytes to autoregulate their own flux into ischemic tissue.39 This ectoenzyme therefore has a critical role at the nexus between inflammation and coagulation at the arterial blood:vessel interface. Whether CD39 has any role under low flow conditions which characterize the venous vasculature has not been elucidated.

In this study, we hypothesized that CD39 diminishes venous thrombosis in a murine model of venous stasis. Mice globally deficient in Cd39 (Cd39−/−) were generated as previously described47 and subjected to IVC ligation to induce venous thrombosis. CD39 attenuated thrombus size and inflammatory cell recruitment into the thrombosed vein. Gene expression profiling revealed differential inferior vena cava (IVC) gene expression following thrombus induction, and compared to sham-operated controls with enhanced thrombo-inflammatory pathway signaling in the absence of CD39. Comprehensive bioinformatics analyses were used to provide a deeper insight into candidate genes identified by expression profiling and to elucidate potential inflammatory mechanisms involved during venous thrombosis. Using this approach, we demonstrate that CD39 attenuates venous stasis thrombosis, down-regulating VWF and soluble (sol) P-selectin expression amidst a broader anti-thrombotic, anti-inflammatory program.

Materials and Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Please see the Major Resource Table in the online-only Supplement.

Animals

For these experiments, Cd39−/− mice and littermate controls (WT) mice were generated as previously described and gene expression validated (Supplemental Fig. I).47, 48 All mice, WT and Cd39−/− were back bred at least 8 generations into the C57BL/6J background. For all experiments, WT and Cd39−/− mice were aged-matched, males or females (8 to 10 weeks). Cd39−/− mice have normal prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, circulating leukocyte counts, and low platelet counts as previously described,40 with normal partial thromboplastin and prothrombin time (data not shown). Cd39LysM mice were generated as previously described and males were used for experiments (8 to 10 weeks).48 Animal experiments were approved by and carried out in accordance with the University of Michigan Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Murine model of stasis-induced deep venous thrombosis

Venous stasis thrombosis was induced by complete or partial ligation of the infra-renal IVC as previously described,20, 24, 25, 49, 50 by an operator blinded to animal genotype. Briefly, mice were anesthetized and underwent midline laparotomy, the intestines were exteriorized and the IVC completely or partially ligated immediately below the renal veins. Side branches were ligated and back branches were cauterized to ensure complete stasis. The abdominal cavity was closed in a bilayer manner using 5–0 Vicryl sutures (Ethicon) for abdominal muscles, and surgical glue (Vetbond, 3M) for the skin. Sham-operated experiments consisted of median laparotomy and vena cava dissection without ligation of the IVC. At specified time-points, the thrombus-containing IVC was carefully removed, and weighed en toto. Following thrombus induction, the thrombosed IVC was either 1) weighed; 2) fixed in 10% formalin; or 3) thrombus and IVC were carefully separated, weighed, snap frozen, and stored at −80°C until used for biochemical analysis.

Histology, immunohistochemistry, and immunoblots.

For histological analysis, 5 μm serial cross sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, visualized with light microscopy and images captured using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-E or Microphot-SA microscope using MetaMorph image analysis software. Immunohistochemistry was performed on 5 μm sections of formalin fixed, paraffin-embedded IVC and thrombus using antibodies targeting Ly6G (1A8 clone 1:250, BD Pharma 55129), P-selectin (1:200. Abcam), and VWF (1:250, A0082 Dako). Prior to antibody incubation, thrombus-containing IVC tissues were subjected to 15 minutes of antigen retrieval (10 mmol/L citrate buffer, pH 6.0, 98° C) and 1 hour of serum-free protein block (Cat X0909 Dako). A secondary antibody conjugated to a horseradish peroxidase-labeled polymer was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and developed using diaminobenzidine or 3-amino-9-ethycarbazole (Vector). For Immunoblots, thrombi were homogenized in RIPA buffer with Roche protease inhibitor cocktail pellet and 1% SDS. Protein quantified using BCA protein assay kit (Pierce), and equal quantities were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to a PVDF membrane. Non-specific binding was blocked with 4% non-fat milk, followed by incubation with primary antibody directed Ly6G (1A8 clone). Appropriate HRP-labeled secondary antibodies (Sigma) and standard enhanced chemiluminescence were used for detection. Band densities were quantified using ImageJ software.

Ectonucleoside Triphosphate Diphosphohydrolase-1 (ENTDP-1/CD39), P-selectin and VWF plasma protein quantification

To determine soluble CD39, P-selectin and VWF levels in plasma, blood was collected from thrombus-induced WT and Cd39−/− mice and respective sham-operated mice via direct cardiac puncture, into EDTA-containing tubes (Becton Dickinson). Platelet-poor plasma was isolated from whole blood by centrifugation (2000 x g, 30 minutes and 10,000 x g, 10 minutes) at 4° C for the soluble P-selectin (sP-selectin) and CD39 ELISA and at 25° C for VWF AlphaLISA. Soluble P-selectin was measured using an ELISA kit (R&D) according to manufacturer instructions. Soluble CD39 levels were measured using ELISA as previously described.51 Plasma VWF antigen levels were determined by AlphaLISA as previously described.52 VWF AlphaLISA signals were determined on an EnSpire 2300 Multimode Plate reader (Perkin Elmer), and VWF levels calculated by comparing signals to a dilution series of plasma from unperturbed C57BL/6J mice. Samples were assayed at least 3 times, and the average coefficient of variance of samples was 7.75%.

Assessment of platelet-leukocyte aggregates in whole blood

Whole blood was collected from the retro-orbital plexus from WT and Cd39−/− mice and placed in cold phosphate buffer saline without magnesium or calcium (PBS) at 4° C. FACSlyse buffer (BD Bioscience) was used to lyse erythrocytes. Total cell counts were assessed by Hemavet (Drew Scientific) and confirmed by flow cytometry using anti-mouse CD45 antibody and absolute count standard beads (BD Bioscience). Viable cells were identified by the absence of DAPI (Molecular Probes) staining. Nonspecific antibody staining was inhibited using rat-anti mouse CD16b/CD32 antibody to block the FcγIII/II receptor (BD Bioscience). In order to evaluate platelet-leukocyte aggregates, we developed a flow cytometric assay to analyze heterotypic cell associations between platelets and myeloid cells in whole blood. Cells and cell aggregates were purified and then identified in four stages. Leukocyte populations were gated by size and granularity. Cells were identified by antibody staining for leukocytes (CD45hi), and myeloid lineage (CD45hi/Gr-1+and CD45hi/CD11b+), and leukocyte-activated platelet (CD41/CD62P+) heteroaggregates were further identified as CD45hi/CD11b+/CD41+/CD62P+ and CD45hi/Gr-1+/CD41+/CD62P+. Within the CD45+/CD11b+ and CD45+/Gr-1+ events, platelets were identified by CD41+ staining; activated platelets were identified by counting CD62P (P-selectin)-positive events. Activated platelet–leukocyte aggregates were calculated from CD41-PE/CD62P double positive gates. All antibodies were purchased from BD Bioscience and specificity was verified using appropriate labeled-isotype control antibodies (anti–rat IgG2a or anti–rat IgG2b). Platelet-leukocyte aggregates were identified using at least 1 × 105 cells from each sample on a multi-spectral BD FACS Canto™ flow cytometer and analyzed with FlowJo v.9.4.11 analysis software (Tree Star). Please see the Major Resource Table in the Supplemental Material.

Microarray-based transcriptional profiling and bioinformatics analysis of microarray data

RNA samples from WT and Cd39−/− mice and their respective sham-operated mice (n=4 per group for biological replicates; technical replication was achieved by pooling four samples for each of the four groups for analysis) were used to detect gene expression changes at 48 hours following venous stasis-induced thrombosis. Following homogenization, total IVC RNA was extracted using TRIzol and RNeasy spin (Qiagen) columns following homogenization. Prior to microarray-based gene expression-profiling RNA was further purified using RNeasy reaction cleanup kit (Qiagen). All procedures were based on the manufacturer’s RNA amplification protocol. 50 nanograms of total RNA were used to synthesize double-stranded cDNA, according to the NuGen WT-Pico V2 kit protocol (Ovation PicoSL WTA System V2 P/N 3312). Biotinylated single-stranded cDNA was prepared from 3 μg of cDNA (Encore Biotin Module P/N 4200–12, 4200–60, 4200-A01). Following fragmentation, 3.7 μg of cDNA was hybridized for 20 hr at 48° C on Mouse Gene ST 1.1 strip arrays, using the Affymetrix Gene Atlas system (software version 1.0.4.267; Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA). Raw intensity data was processed and exported using Affymetrix Command Console, after scanning with the Affymetrix Gene Atlas system. Subsequent analyses were performed using the R programming environment 2.15.0 (R development core team 2011): a language and environment for statistical computing with the Oligo bioconductor software packages (Bioconductor, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center).53 After ensuring quality control as recommended by the manufacturer, data was normalized using robust multi-array average expression measure. Comparisons were made between WT and Cd39−/− mice, and their respective sham-operated mice. Data were filtered using probesets, and a fold change greater than 2 (with the added constraint that one of the two samples had an expression value of 25 or greater) to remove non-informative genes. Variable genes were plotted as heatmaps with hierarchical clustering using euclidean distance as a distance measure, and complete linkage as the clustering method using the “stats” package of R. Fold-changes were visualized with color ranging from red (high expression relative to sham) over white (intermediate expression relative to sham) to blue (low expression relative to sham). All data and material have been made publicly available at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository and can be accessed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE125965

Molecular interaction networks and functional analysis

Using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) tool 9.0 software (Ingenuity Systems), gene ontology identified potential cellular functions affected by induction of thrombosis or the deletion of Cd39. The “Core Analysis” was used to interpret the large datasets in the context of biological functions, disease processes, and molecular networks. The gene lists containing Affymetrix IDs, fold change, and P values, were mapped in the Ingenuity Pathways Knowledge Base (IPKB). The identified focus genes were then used in the network algorithm to generate scored networks, based on the curated list of molecular interactions in IPKB. Pathway and global functional analyses were performed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis 6.0 (Ingenuity® Systems). A data set containing gene identifiers and corresponding expression values was uploaded into the application, and each gene identifier was mapped using the IPKB. The IPKB analyses identify the biological functions as well as the pathways from the IPA library that are most significant to the data set. Genes from the data sets associated with biological functions or with a canonical pathway in the IPKB that met the p-value cutoff of 0.005 were used to build the interactome, as described above. Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate a p-value, determining the probability that each biological function and/or canonical pathway assigned to this data set was not due to chance alone.

Validation by quantitative RT-PCR

Differential gene expression identified through microarray analysis was validated with quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) using TaqMan probes and ABI Prism 7500fast sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) according to manufacturer instructions and normalized to beta actin expression. Briefly, the vein wall was separated from its associated thrombus, placed in a 15 mL conical tube filled with 1.5 mL of TRIzol (Invitrogen), and homogenized using the standard homogenization protocol. The RNA was cleaned using the RNAeasy reaction cleanup kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For this procedure, RNA concentrations were verified using the Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher).

Statistical analysis

All data are represented as mean ± SD, with the numbers of experiments performed provided in the figure legends. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 software. All continuous variables were first analyzed for normality and equal variance. If data passed both tests, differences between statistical groups were evaluated for statistical significance using the Student’s t-test, and comparison of results between different groups with more than 2 conditions were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey post-hoc test. If data did not pass either test, non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc test was used for multiple group comparisons. P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

CD39-deficiency exaggerates venous thrombosis and vein wall leukosequestration.

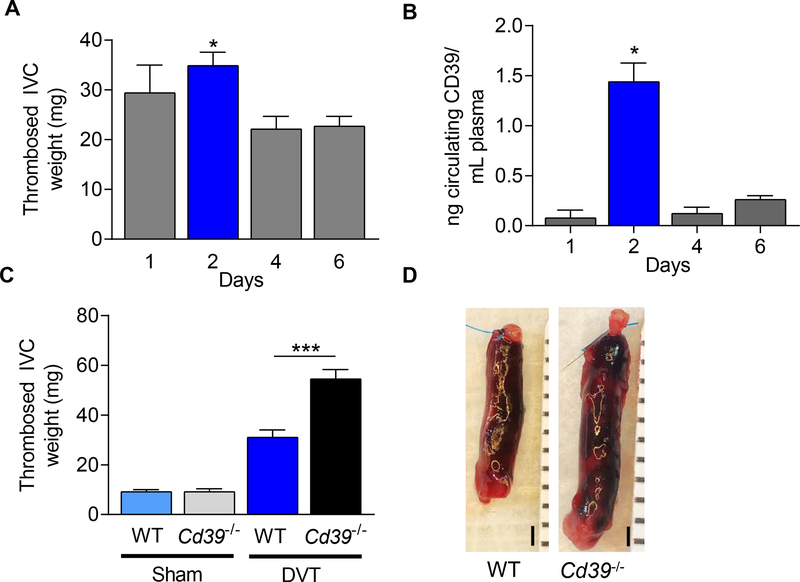

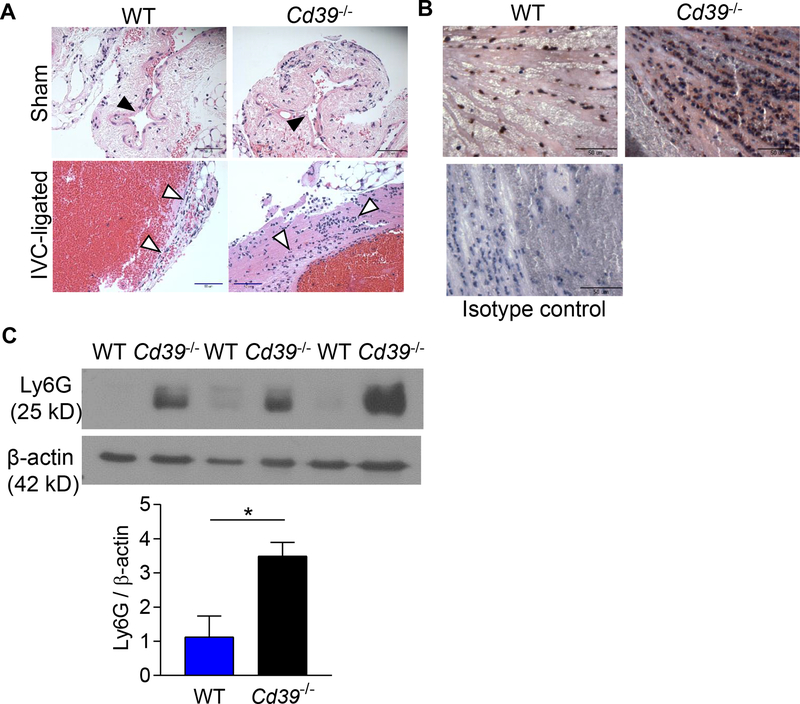

Deep venous thrombosis was induced in Cd39+/+ (WT) and mice completely deficient in CD39 (Cd39−/−) by ligating the infrarenal vena cava to create venous stasis in the IVC.25, 49 All mice developed a thrombus following IVC ligation. Thrombus size was largest forty-eight hours following thrombus induction, consistent with previous reports,20, 54 with a decrease in thrombus mass in the subsequent several days (Fig 1A). To understand the role of endogenous CD39 in venous thrombosis, we measured the circulating levels of CD39 shed from plasma membranes in these WT mice and determined that circulating CD39 expression peaks concurrently 48 hours following IVC thrombus induction (Fig 1B). These observations led us to focus on the effect of CD39-deletion on venous thrombosis 48 hours following IVC ligation. Compared to the WT age-matched controls, Cd39−/− mice developed 75% larger venous thrombi (Fig. 1C,D), suggesting an important role for CD39 in mitigating stasis-induced venous thrombosis. A similar pattern was observed in female Cd39−/− mice (Supplemental Fig. II). The presence of CD39 also exerted a distinct inhibitory effect on thrombus inflammation. There was increased leukosequestration in the thrombosed IVC of male Cd39−/− mice compared to WT mice (Fig 2A). This was driven by enhanced neutrophil accumulation in the thrombosed IVC in Cd39−/− compared to WT mice (Fig 2B,C). These data demonstrate that CD39 reduces leukocyte sequestration, by limiting recruitment of neutrophils to the thrombosed vein wall. We examined whether the increased thrombosis after IVC ligation observed in Cd39−/− mice was consistent across venous thrombosis models. Cd39−/− mice did not develop venous thrombi under flow-restricted conditions (Supplemental Fig. III), consistent with prior studies showing Cd39−/− mice have desensitized P2Y1 receptors from excess local ATP, rendering the platelets hypofunctional to initial stimulus by extracellular nucleotides.38, 40

Figure 1. Characterization of thrombus weight in WT and Cd39−/− mice 48 hr after stasis-induced thrombosis.

(A) Thrombosed IVC weight in WT mice 1–6 days following IVC ligation-induced venous thrombosis (1d, n=7; 2d, n=13; 4d, n=9; 6d, n=11, *P < 0.05 vs. 4d and 6d). (B) Circulating plasma soluble CD39 levels in WT mice following IVC-ligation (1d, n=3; 2d, n=3; 4d, n=3; 6d, n=6). (C) Thrombus-containing IVC weight in sham-operated mice and stasis-induced venous thrombosis in WT and Cd39−/− mice at 48 hours. Sham: WT, n=8; Cd39−/− n=8. IVC-ligated: WT, n=12; Cd39−/− n=7. (D) Representative photomicrographs of stasis-induced venous thrombosis of WT and Cd39−/− mice at 48 hours following IVC ligation. Scale bar, 1 mm. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.005.

Figure 2. Increased leukocyte recruitment to the thrombosed IVC in WT and Cd39−/− mice.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin stained inferior vena cava section of 48 hour sham operated- and thrombosed-IVC of WT and Cd39−/− mice. Black arrowheads=IVC; white arrowheads=recruited leukocytes. Scale bar, 50 μm; representative sections, n=5 each. (B) Neutrophil staining (Ly6G, brown) in thrombosed veins of WT and Cd39−/− mice counterstained with hematoxylin. Scale bar, 50 μm; representative sections, n=3 each. (C) Immunoblot for Ly6G in venous thrombi from WT and Cd39−/− mice. N=3, each; *P<0.05

Functional pathway and gene network analyses identified highly upregulated genes in CD39-deficient venous stasis thrombosis.

To examine gene expression profiles that are associated with leukosequestration following IVC ligation, mRNA expression from IVCs of all animal groups (IVC-ligated, and sham-operated in WT and Cd39−/−) was profiled using the Affymetrix gene chip ST1.1 microarray platform. Using biological replicates (n=4), we identified 854 probe sets with significant differential expression (minimal fold change −2 to 2; P≤0.001) between the four experimental groups in each pairwise comparison (Fig. 3A, B; Supplemental Fig. VI).

Figure 3. Gene expression patterns demonstrate distinct vessel wall thrombo-inflammatory signaling pathways in WT and Cd39−/− mice in venous thrombosis.

Inferior vena cava gene expression patterns due to CD39 deficiency or stasis-induced thrombosis. Venn diagrams illustrating the number of differentially expressed genes (probe sets; fold change ≥2; P≤0.001) in each pairwise comparison of IVCs between (A) WT sham vs. WT IVC-ligated; and (B) WT IVC-ligated vs. Cd39−/− IVC-ligated mice (n=4 pooled IVCs, each). Hierarchical clustering of a subset of dynamically expressed genes involved in inflammation and immunity following venous thrombosis in (C) WT mice; and (D) following Cd39−/− deficiency. (E) Network analysis of co-expressed key inflammatory genes under venous stasis thrombosis conditions in Cd39−/− compared with WT mice. Red: upregulation; green: downregulation.

We hypothesized that induction of thrombosis and the deletion of Cd39 would influence inflammatory mediator gene expression, and we examined immune response genes that were differentially expressed due to CD39 deficiency or stasis-induced thrombosis (). We focused our analysis on 76 unique probe sets that showed a concordant increase in expression in sham-operated vs. DVT-induced mice, and WT IVC-ligated vs. Cd39−/− IVC-ligated mice, and we identified ten differentially expressed genes that play cardinal roles in inflammation to validate our microarray data; Il-6, Nos2, Il-1b, Tnf, Ccl2, Cxcl2, Chi313, Arg1, Selp, and Vwf. Our data show that Selp, Vwf and Il-6 were slightly up-regulated in stasis-induced thrombosis in WT mice (Fig. 3C), consistent with prior studies.29, 49, 54, 55 We noted a further increase in Selp, Vwf and Il-6 in Cd39−/− mice (Fig. 3D) compared with WT controls. We also noted a corresponding increase in expression of Selplg (P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1, PSGL-1) in the microarray, which encodes an adhesion molecule involved in immune cell trafficking. Macrophage phenotypes fall into a from “classically-activated” to “alternatively-activated” which influence their function in the inflamed tissue.48 We noted that expression of Chi313 and Arg1, seen in “alternatively-activated” macrophages, were upregulated (fold change > 4) by stasis-induced thrombosis, and were further increased in Cd39−/− mice following DVT induction (fold change > 5) (Fig. 3C,D). These experiments and leukocyte extravasation subnetwork analyses (Fig. 3E; Supplemental Fig. V) show that CD39 likely influences expression of key inflammatory mediators during stasis-induced thrombosis.

To independently confirm the microarray results, we performed quantitative real-time PCR on vein walls of WT and Cd39−/− sham-operated or IVC-ligated mice following IVC ligation. The relative expression levels of ten differentially expressed genes identified through the microarray analysis were quantified (Fig. 4). IL-1β and Cxcl2 gene expression significantly increased during stasis-induced thrombosis and with CD39-deficiency. Genes associated with classically- (TNF-α and CCL-2) and alternatively-activated macrophages were also expressed at higher levels in Cd39−/− mice, concordant with our prior observations.48 In addition, stasis-induced thrombosis in the absence of CD39 enhanced Selp (P-selectin) ~2 fold, respectively. The pattern of dysregulation of several genes with prominent proinflammatory functions, as well as several chemokines, presents the first molecular evidence that CD39-deficiency can modulate leukosequestration in stasis-induced thrombosis.

Figure 4. Validation of microarray results reveals quantitative RT-PCR analysis of WT and Cd39−/− mice 48 hr following IVC ligation.

Gene expression of pro-inflammatory mediators and chemokines in vena cava of WT and Cd39−/− mice 48 hours after IVC ligation using qRT-PCR normalized to β-actin expression. Data shown as mean ± SEM, n≥4, each. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

CD39 reduces circulating and vein wall P-selectin and VWF expression following thrombus induction

P-selectin and VWF, which are co-packaged on and in endothelial sub-plasmalemmal Weibel Palade bodies, facilitate initial rolling and recruitment of leukocytes during thrombosis.29, 49, 56 P-selectin has been studied as a mediator of venous thrombosis in mouse models, and validated in patients as a biomarker for venous thrombosis.49, 57 VWF-null mice are protected from DVT.29 While recent studies link inflammation and venous thrombosis,15, 58, 59 the precise role that CD39, P-selectin, and VWF together play in leukosequestration during venous thrombosis has not been defined. We thus examined whether the gene expression profiles found by microarray (and validated by standard qRT-PCR) translated to differential protein expression. Circulating levels of P-selectin and VWF in WT and Cd39−/− sham-operated or IVC-ligated mice were measured by ELISA, and both were determined to be significantly higher in Cd39−/− mice compared to WT mice following IVC ligation (Fig. 5A, B).

Figure 5. CD39-deficiency increases local and circulating P-selectin and von Willebrand Factor expression.

Plasma soluble (A) P-selectin and (B) circulating VWF levels in WT and Cd39−/− mice. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001; n=3–6 (A) and n=11–31 (B). Localization of vein wall and thrombus (C) P-selectin and (D) VWF by immunohistochemistry in sham and IVC-ligated WT and Cd39−/− mice. Black arrowheads, P-selectin; white arrowheads, VWF; scale bar, 50 μm.

To determine whether the induction of P-selectin and VWF is restricted to the circulating fraction of the vascular compartment, we examined the localization of P-selectin (Fig. 5C), and VWF (Fig. 5D) in Cd39−/− and WT mice following IVC ligation (IgG control stains, Supplemental Fig. VI). While P-selectin expression at the blood:vessel wall interface was similar between WT and Cd39−/− mice with venous thrombosis, there was a mild increase in P-selectin expression within the thrombus milieu of Cd39−/− mice compared with WT mice. Examination of VWF expression showed analogous expression at the vein luminal surface in both strains that diverged following IVC ligation, with enhanced VWF expression in the endothelium of CD39-deficient mice as well as within the thrombus compared to their wild type counterparts. This suggests that CD39 suppresses vascular expression of the pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic molecular effectors, VWF and P-selectin in the thrombotic milieu following IVC ligation.

CD39 regulates circulating platelet-leukocyte trafficking and aggregation in venous thrombosis

P-selectin on activated platelets is a potent initiator of leukocyte adhesion.60 Using multi-color flow cytometry to quantify heterotypic cell interactions between platelets and leukocytes, we analyzed peripheral blood from mice Cd39−/− forty eight hours following IVC ligation. We determined that a larger fraction of CD45hi/CD11b+ myeloid cells interacted with activated platelets (CD41+/CD62P+) in CD39-deficient mice (76% of CD11b+ cells) following venous thrombosis, compared to WT mice (53% of CD11b+ cells) (Fig. 6A). Similarly, activated platelet-Gr-1+ leukocyte aggregates accounted for a larger fraction of Gr-1+ cells in the thrombosed Cd39−/− mice (42% of Gr-1+ cells) compared to the fraction of aggregates in WT mice (14% of Gr-1+ cells) (Fig. 6B). We also observed a marked increase in the absolute number of circulating platelet-leukocyte aggregates in CD39-deficient mice following IVC ligation (Fig. 6C, D), suggesting a central role for CD39 in tempering leukocyte recruitment and platelet-leukocyte crosstalk in venous thrombosis. This led us to examine whether myeloid-specific CD39 reduced venous thrombosis. Indeed, myeloid CD39-deleted (Cd39LysM) mice developed larger venous thrombi following IVC ligation, suggesting that the increase in venous thrombus size is at least in part dependent on myeloid CD39 (Supplemental Fig. VII).

Figure 6. Increased circulating activated platelet-leukocyte aggregates in Cd39−/− mice following venous thrombosis.

Representative flow cytometric analysis of myeloid-derived leukocytes in whole blood from WT and Cd39−/− sham-operated or IVC-ligated mice. (A) activated CD62+ platelet-CD11b+ leukocyte aggregates in Cd39−/− mice (76.3% ± 12.3; n=3) and WT mice (52.6% ± 10.2; n=4. P<0.001), and (B) activated CD62P+ platelet-Gr-1+ leukocyte aggregates. Quantitative cell count analysis of (C) CD11b+/CD41+/CD62P+ cells, and (D) GR-1+/CD41+/CD62P+ cells in WT and Cd39−/− sham operated or IVC-ligated mice 48 hours post IVC-ligation. Data are shown are n=3–5, mean ± SD. *P<0.05, ***P<0.0001.

Discussion

Thrombosis and inflammation at the blood:vein wall interface are closely intertwined in the development and propagation of DVT. These studies demonstrate for the first time that CD39 plays role as a protective molecular damper in venous thrombosis. CD39, a vascular ecto-apyrase rapidly phosphohydrolyzes extracellular nucleotides released by platelets, leukocytes, and other activated cells, to degrade ATP and ADP, inhibiting a reverberating cycle of platelet activation and leukocyte recruitment.38, 39 In this study, our data reveal that CD39 plays a critical role in mitigating thrombosis in venous stasis, by squelching inflammatory and coagulant processes in the thrombotic milieu. Mice lacking CD39 developed larger venous thrombi with exaggerated leukocyte recruitment to the thrombus. High levels of local extracellular ATP, which is primarily catabolized by CD39, can exaggerate neutrophil chemotaxis and monocyte activation.32, 61 Activated myeloid cells contribute to thrombo-inflammation through multiple mechanisms.61–63 In addition, heterotypic cell interactions between platelets and leukocytes facilitates degranulation, and potentiates a positive feedback loop of further leukocyte recruitment.17, 64 We observed an increase in circulating platelet-leukocyte interactions following DVT induction which was further exaggerated by the absence of CD39, implying a role for myeloid-lineage cells in venous stasis-driven thrombosis. Indeed, hematopoietic cells are a significant source of tissue factor which plays a central role in venous thrombosis.65 The present investigation suggests that CD39 is an important mechanistic link between myeloid-driven venous inflammation and venous stasis-driven thrombosis.

To comprehensively understand how CD39 plays a role in stasis thrombosis, especially related to leukocyte influx, we chose an unbiased approach using a microarray analysis that demonstrated 132 genes affected by IVC-ligation, and 722 genes affected by CD39-deficiency and IVC-ligation, using at least a 2-fold change in expression as a signal indicator. This revealed several inflammatory- and immune response-relevant signaling pathways that were overrepresented in WT DVT mice, and in both Cd39−/− sham and Cd39−/− DVT mice, including: leukocyte extravasation signaling; hypoxic signaling; inflammation signaling; and coagulation pathways. The pronounced increase in leukocyte influx in CD39-deficient mice led us to hone in on leukocyte activation, chemokinesis, and adhesion. Through this analysis, we identified a group of genes that show a concordant increase in expression in sham vs. DVT, and between WT and Cd39−/− mice with venous thrombosis. We confirmed the presence of several previously reported genes implicated in stasis thrombosis,66,54,29,55 and now extend this list to genes with known roles in coagulation and leukosequestration that were differentially expressed during IVC-ligation. In addition, Il-1β, NOS2, and Chi313 (a “reparative-polarized” macrophage marker), were upregulated during stasis-induced thrombosis, with a concordant increase in the absence of CD39. Prior studies using endothelial cells in vitro have demonstrated important roles for CD39 in modulation of inflammatory and pro-adhesive proteins.67 However, these data using an unbiased approach is the first description of CD39’s role in modulation of inflammatory and pro-adhesive gene expression programs in vivo. Further studies are needed to gain a better understanding of their biological relevance to CD39 in acute and chronic venous thrombosis.

Our data implicate CD39 as an important mitigator of DVT as a thrombo-inflammatory process. Using an RNA transcriptomic approach, the pathways enriched from up-regulated genes under venous thrombosis and CD39-deficient conditions point to activation of leukocyte extravasation signaling, NF-κB signaling, chemokine- and cytokine-mediated immune responses, and coordination of coagulation and inflammation programs. Indeed, CD39 seems to “tune” down the inflammatory response to venous stasis. P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) is an important mediator of platelet-endothelial interaction, leukocyte rolling, adhesion and thrombus generation.56, 68 In our network analysis of leukocyte extravasation signaling we determined that PSGL-1 was highly induced in CD39-deficiency. PSGL-1 plays important roles in leukocyte rolling, adhesion and transmigration at the site of inflammation and venous thrombosis.24, 68,56 A previous study demonstrated that CD39 can reduce leukocyte recruitment to ischemic brain tissue by suppression of leukocyte integrin αMβ2 expression.39, 48 The data presented expand this observation. IVC-ligation and CD39 deletion induced expression of genes involved in both leukocyte adhesion and transmigration implies a central and mechanistic role for CD39 in the regulation of leukocyte migration to the vein wall during the propagation of thrombosis.

Circulating blood leukocytes in DVT, particularly neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages, display an activated phenotype that predisposes to endothelial adhesion, amplification of vascular inflammation, and thrombosis. Exaggerated platelet activation and the formation of platelet-leukocyte aggregates have been implicated in venous thrombosis.17 CD39 is an important mechanism that restricts platelet-mediated platelet recruitment by hydrolyzing platelet granule-released ADP.40, 45 In the current study, our examination of platelet- leukocyte aggregates revealed more platelets bound to myeloid-derived leukocytes in the absence of CD39 compared with controls. Although platelets are not believed to play a role in the size of venous stasis thrombosis, the increased circulating leukocyte-platelet crosstalk in Cd39−/− mice suggest possible mechanistic avenues to further investigate our findings of leukocyte activation, increased thrombus burden and neutrophil recruitment to the vein wall in these mice.

Taken together, these studies are the first to demonstrate a critical role for the vascular ecto-apyrase, CD39 in mitigating the thrombo-inflammatory milieu of stasis DVT. We provide evidence that CD39 deficient mice have exaggerated vascular inflammation resulting in increased extravasation of key inflammatory cells, activation of vascular coagulant reactions at the blood:vessel interface, and heterotypic immune and platelet cell:cell interactions following venous stasis. These data also demonstrate through gene expression profiling with bioinformatics analysis that complex inflammatory networks are activated following thrombus accretion. Absence of CD39 allows for a shift toward a pro-inflammatory vascular wall phenotype. Understanding the complex interplay of vascular injury, stasis and coagulation and the protective role of vascular ectoenzymes could lead to new therapies for DVT, or other disorders at the intersection of inflammation and coagulation.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

CD39, a vascular ecto-apyrase is a critical suppressor of venous stasis thrombosis

CD39 suppresses activation of a program of upregulated gene expression of leukocyte trafficking and cytokine signaling pathways in venous thrombosis

CD39 tempers circulating leukocyte-activated platelet interactions in venous stasis thrombosis

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge Shirley Wrobleski and Cathy Luke for technical assistance with venous thrombosis modeling. The authors also wish to acknowledge the Histology Core at the University of Michigan School of Dentistry, Flow Cytometry and Sequencing Cores at the University of Michigan Medical School.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by the following funding sources: NIH grants T32GM008322, T32HL007853 (ACA,YK); HL127151, NS087147, HL007853 (DJP), K08HL131993 (YK); McKay grant, Bo Schembechler Heart of a Champion Foundation, Jobst-American Venous Forum (YK), HL141399 (KCD), the J. Griswold Ruth MD & Margery Hopkins Ruth Professorship, Haller Family Foundation, the A. Alfred Taubman Medical Research Institute (DJP) and the Frankel Cardiovascular Center.

Abbreviations:

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- ADP

adenosine diphosphate

- AMP

adenosine monophosphate

- IVC

inferior vena cava

- sP-selectin

soluble P-selectin

- VWF

von Willebrand factor

- DVT

deep vein thrombosis

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no relevant disclosures.

References

- 1.Silverstein MD, Heit JA, Mohr DN, Petterson TM, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ 3rd. Trends in the incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: A 25-year population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:585–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bureau. USC. Monthly populations estimates for the united states: April 1, 2010 to december 1, 2012. Population Estimates. 2012;2012 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yusuf HR, Tsai J, Atrash HK, Boulet S, Gross SD. Venous thromboembolism in adult hospitalizations-united states, 2007–2009. Atlanta, Ga: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Center for Diseases Control. Venous thromboembolism.2018

- 5.Ocak G, Vossen CY, Verduijn M, Dekker FW, Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, Lijfering WM. Risk of venous thrombosis in patients with major illnesses: Results from the mega study. J Thromb Haemost. 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andoh A, Yoshida T, Yagi Y, Bamba S, Hata K, Tsujikawa T, Kitoh K, Sasaki M, Fujiyama Y. Increased aggregation response of platelets in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:47–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esmon CT. The impact of the inflammatory response on coagulation. Thromb Res. 2004;114:321–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weidner N, Ittyerah TR, Wochner RD, Sherman LA. Investigation of an inflammatory humoral factor as a stimulator of fibrinogen synthesis. Thromb Res. 1979;15:651–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alberio L, Safa O, Clemetson KJ, Esmon CT, Dale GL. Surface expression and functional characterization of alpha-granule factor v in human platelets: Effects of ionophore a23187, thrombin, collagen, and convulxin. Blood. 2000;95:1694–1702 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baxi S, Crandall DL, Meier TR, Wrobleski S, Hawley A, Farris D, Elokdah H, Sigler R, Schaub RG, Wakefield T, Myers D. Dose-dependent thrombus resolution due to oral plaminogen activator inhibitor (pai)-i inhibition with tiplaxtinin in a rat stenosis model of venous thrombosis. Thromb Haemostasis. 2008;99:749–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Day SM, Reeve JL, Pedersen B, Farris DM, Myers DD, Im M, Wakefield TW, Mackman N, Fay WP. Macrovascular thrombosis is driven by tissue factor derived primarily from the blood vessel wall. Blood. 2005;105:192–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esmon CT. Inflammation and thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:1343–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor FB, Chang A, Esmon CT, Dangelo A, Viganodangelo S, Blick KE. Protein-c prevents the coaggulopathic and lethal effects of escherichia-coli infusion in the baboon. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:918–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaub RG, Simmons CA, Koets MH, Romano PJ, 2nd, Stewart GJ. Early events in the formation of a venous thrombus following local trauma and stasis. Lab Invest. 1984;51:218–224 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stewart GJ, Ritchie WGM, Lynch PR. Venous endothelial damage produced by massive sticking and emigration of leukocytes. Am J Pathol. 1974;74:507–532 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wakefield TW, Strieter RM, Prince MR, Downing LJ, Greenfield LJ. Pathogenesis of venous thrombosis: A new insight. Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;5:6–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Bruhl ML, Stark K, Steinhart A, et al. Monocytes, neutrophils, and platelets cooperate to initiate and propagate venous thrombosis in mice in vivo. J Exp Med. 2012;209:819–835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Acker T, Fandrey J, Acker H. The good, the bad and the ugly in oxygen-sensing: Ros, cytochromes and prolyl-hydroxylases. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:195–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bovill EG, van der Vliet A. Venous valvular stasis-associated hypoxia and thrombosis: What is the link? Annu Rev Physiol. 2011;73:527–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diaz JA, Obi AT, Myers DD Jr., Wrobleski SK, Henke PK, Mackman N, Wakefield TW. Critical review of mouse models of venous thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:556–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lopez JA, Kearon C, Lee AY. Deep venous thrombosis. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2004:439–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackman N Mouse models, risk factors, and treatments of venous thrombosis. Arterioscl Throm Vas. 2012;32:554–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manly DA, Boles J, Mackman N. Role of tissue factor in venous thrombosis. Annual Review of Physiology, Vol 73. 2011;73:515–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knight JS, Meng H, Coit P, et al. Activated signature of antiphospholipid syndrome neutrophils reveals potential therapeutic target. JCI Insight. 2017;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myers D, Farris D, Hawley A, Wrobleski S, Chapman A, Stoolman L, Knibbs R, Strieter R, Wakefield T. Selectins influence thrombosis in a mouse model of experimental deep venous thrombosis. J Surg Res. 2002;108:212–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinelli I Von willebrand factor and factor viii as risk factors for arterial and venous thrombosis. Semin Hematol. 2005;42:49–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Germain M, Chasman DI, de Haan H, et al. Meta-analysis of 65,734 individuals identifies tspan15 and slc44a2 as two susceptibility loci for venous thromboembolism. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96:532–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith NL, Rice KM, Bovill EG, et al. Genetic variation associated with plasma von willebrand factor levels and the risk of incident venous thrombosis. Blood. 2011;117:6007–6011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brill A, Fuchs TA, Chauhan AK, Yang JJ, De Meyer SF, Kollnberger M, Wakefield TW, Lammle B, Massberg S, Wagner DD. Von willebrand factor-mediated platelet adhesion is critical for deep vein thrombosis in mouse models. Blood. 2011;117:1400–1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pendu R, Terraube V, Christophe OD, Gahmberg CG, de Groot PG, Lenting PJ, Denis CV. P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 and beta2-integrins cooperate in the adhesion of leukocytes to von willebrand factor. Blood. 2006;108:3746–3752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burnstock G Dual control of local blood-flow by purines. Ann Ny Acad Sci. 1990;603:31–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Y, Corriden R, Inoue Y, Yip L, Hashiguchi N, Zinkernagel A, Nizet V, Insel PA, Junger WG. Atp release guides neutrophil chemotaxis via p2y2 and a3 receptors. Science. 2006;314:1792–1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freyer DR, Boxer LA, Axtell RA, Todd RF. Stimulation of human neutrophil adhesive properties by adenine-nucleotides. J Immunol. 1988;141:580–586 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Linden J Cell biology. Purinergic chemotaxis. Science. 2006;314:1689–1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vischer UM, Wollheim CB. Purine nucleotides induce regulated secretion of von willebrand factor: Involvement of cytosolic ca2+ and cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent signaling in endothelial exocytosis. Blood. 1998;91:118–127 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.von Albertini M, Palmetshofer A, Kaczmarek E, Koziak K, Stroka D, Grey ST, Stuhlmeier KM, Robson SC. Extracellular atp and adp activate transcription factor nf-kappa b and induce endothelial cell apoptosis. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 1998;248:822–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zimmermann H. Nucleotides and cd39: Principal modulatory players in hemostasis and thrombosis. Nature Medicine. 1999;5:987–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanthi Y, Hyman MC, Liao H, Baek AE, Visovatti SH, Sutton NR, Goonewardena SN, Neral MK, Jo H, Pinsky DJ. Flow-dependent expression of ectonucleotide tri(di)phosphohydrolase-1 and suppression of atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3027–3036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hyman MC, Petrovic-Djergovic D, Visovatti SH, Liao H, Yanamadala S, Bouis D, Su EMJ, Lawrence DA, Broekman MJ, Marcus AJ, Pinsky DJ. Self-regulation of inflammatory cell trafficking in mice by the leukocyte surface apyrase cd39. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1136–1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Enjyoji K, Sevigny J, Lin Y, et al. Targeted disruption of cd39/atp diphosphohydrolase results in disordered hemostasis and thromboregulation. Nature Medicine. 1999;5:1010–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marcus AJ, Broekman MJ, Drosopoulos JHF, Islam N, Alyonycheva TN, Safier LB, Hajjar KA, Posnett DN, Schoenborn MA, Schooley KA, Gayle RB, Maliszewski CR. The endothelial cell ecto-adpase responsible for inhibition of platelet function is cd39. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1351–1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lau CL, Zhao Y, Kim J, Kron IL, Sharma A, Yang Z, Laubach VE, Linden J, Ailawadi G, Pinsky DJ. Enhanced fibrinolysis protects against lung ischemia–reperfusion injury. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2009;137:1241–1248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshida O, Kimura S, Jackson EK, Robson SC, Geller DA, Murase N, Thomson AW. Cd39 expression by hepatic myeloid dendritic cells attenuates inflammation in liver transplant ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Hepatology. 2013;58:2163–2175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Imai M, Takigami K, Guckelberger O, Lin Y, Sevigny J, Kaczmarek E, Goepfert C, Enjyoji K, Bach FH, Rosenberg RD, Robson SC. Cd39/vascular atp diphosphohydrolase modulates xenograft survival. Transplantation Proceedings. 2000;32:969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pinsky DJ, Broekman MJ, Peschon JJ, et al. Elucidation of the thromboregulatory role of cd39/ectoapyrase in the ischemic brain. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;109:1031–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belayev L, Khoutorova L, Deisher TA, Belayev A, Busto R, Zhang Y, Zhao W, Ginsberg MD. Neuroprotective effect of solcd39, a novel platelet aggregation inhibitor, on transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Stroke. 2003;34:758–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Visovatti SH, Hyman MC, Goonewardena SN, Anyanwu AC, Kanthi Y, Robichaud P, Wang J, Petrovic-Djergovic D, Rattan R, Burant CF, Pinsky DJ. Purinergic dysregulation in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;311:H286–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sutton NR, Hayasaki T, Hyman MC, et al. Ectonucleotidase cd39-driven control of postinfarction myocardial repair and rupture. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e89504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Myers DD Jr, Henke PK, Wrobleski SK, Hawley AE, Farris DM, Chapman AM, Knipp BS, Thanaporn P, Schaub RG, Greenfield LJ, Wakefield TW. P-selectin inhibition enhances thrombus resolution and decreases vein wall fibrosis in a rat model. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2002;36:928–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meng H, Yalavarthi S, Kanthi Y, Mazza LF, Elfline MA, Luke CE, Pinsky DJ, Henke PK, Knight JS. In vivo role of neutrophil extracellular traps in antiphospholipid antibody-mediated venous thrombosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:655–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baek AE, Kanthi Y, Sutton NR, Liao H, Pinsky DJ. Regulation of ecto-apyrase cd39 (entpd1) expression by phosphodiesterase iii (pde3). FASEB J. 2013;27:4419–4428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Desch KC, Ozel AB, Siemieniak D, et al. Linkage analysis identifies a locus for plasma von willebrand factor undetected by genome-wide association. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110:588–593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gentleman R, Carey V, Bates D, et al. Bioconductor: Open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biology. 2004;5:R80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Culmer DL, Diaz JA, Hawley AE, Jackson TO, Shuster KA, Sigler RE, Wakefield TW, Myers DD Jr. Circulating and vein wall p-selectin promote venous thrombogenesis during aging in a rodent model. Thrombosis Research. 2013;131:42–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henke PK, Pearce CG, Moaveni DM, Moore AJ, Lynch EM, Longo C, Varma M, Dewyer NA, Deatrick KB, Upchurch GR, Wakefield TW, Hogaboam C, Kunkel SL. Targeted deletion of ccr2 impairs deep vein thombosis resolution in a mouse model. The Journal of Immunology. 2006;177:3388–3397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Myers DD, Hawley AE, Farris DM, Wrobleski SK, Thanaporn P, Schaub RG, Wagner DD, Kumar A, Wakefield TW. P-selectin and leukocyte microparticles are associated with venous thrombogenesis. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2003;38:1075–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ramacciotti E, Blackburn S, Hawley AE, Vandy F, Ballard-Lipka N, Stabler C, Baker N, Guire KE, Rectenwald JE, Henke PK, Myers DD, Wakefield TW. Evaluation of soluble p-selectin as a marker for the diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis. Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis. 2011;17:425–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roumen-Klappe EM, Janssen MCH, Van Rossum J, Holewijn S, Van Bokhoven MMJA, Kaasjager K, Wollersheim H, Den Heijer M. Inflammation in deep vein thrombosis and the development of post-thrombotic syndrome: A prospective study. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2009;7:582–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gupta N, Sahu A, Prabhakar A, Chatterjee T, Tyagi T, Kumari B, Khan N, Nair V, Bajaj N, Sharma M, Ashraf MZ. Activation of nlrp3 inflammasome complex potentiates venous thrombosis in response to hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:4763–4768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Bruijne-Admiraal L, Modderman P, Von dem Borne A, Sonnenberg A. P-selectin mediates ca(2+)-dependent adhesion of activated platelets to many different types of leukocytes: Detection by flow cytometry. Blood. 1992;80:134–142 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Piccini A, Carta S, Tassi S, Lasiglie D, Fossati G, Rubartelli A. Atp is released by monocytes stimulated with pathogen-sensing receptor ligands and induces il-1beta and il-18 secretion in an autocrine way. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8067–8072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fuchs TA, Brill A, Duerschmied D, Schatzberg D, Monestier M, Myers DD Jr., Wrobleski SK, Wakefield TW, Hartwig JH, Wagner DD. Extracellular DNA traps promote thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15880–15885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Henke PK, Varga A, De S, Deatrick CB, Eliason J, Arenberg DA, Sukheepod P, Thanaporn P, Kunkel SL, Upchurch GR Jr., Wakefield TW. Deep vein thrombosis resolution is modulated by monocyte cxcr2-mediated activity in a mouse model. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1130–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zarbock A, Polanowska-Grabowska RK, Ley K. Platelet-neutrophil-interactions: Linking hemostasis and inflammation. Blood Reviews. 2007;21:99–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grover SP, Mackman N. Tissue factor: An essential mediator of hemostasis and trigger of thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38:709–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wojcik BM, Wrobleski SK, Hawley AE, Wakefield TW, Myers DD Jr, Diaz JA. Interleukin-6: A potential target for post-thrombotic syndrome. Annals of Vascular Surgery. 2011;25:229–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goepfert C, Imai M, Brouard S, Csizmadia E, Kaczmarek E, Robson SC. Cd39 modulates endothelial cell activation and apoptosis. Mol Med. 2000;6:591–603 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ramacciotti E, Myers DD Jr, Wrobleski SK, Deatrick KB, Londy FJ, Rectenwald JE, Henke PK, Schaub RG, Wakefield TW. P-selectin/ psgl-1 inhibitors versus enoxaparin in the resolution of venous thrombosis: A meta-analysis. Thrombosis Research. 2010;125:e138–e142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.