Abstract

Sterol 14α-demethylases (CYP51) are the cytochrome P450 enzymes essential for sterol biosynthesis in eukaryotes and therapeutic targets for antifungal azoles. Multiple attempts to repurpose antifungals for treatment of human infections with protozoa (Trypanosomatidae) have been undertaken, yet so far none of them revealed sufficient efficacy. VNI and its derivative VFV are two potent experimental inhibitors of Trypanosomatidae CYP51, effective in vivo against Chagas disease, visceral leishmaniasis, and sleeping sickness and currently under consideration as antiprotozoal drug candidates. However, VNI is less potent against Leishmania and drug-resistant strains of Trypanosoma cruzi and VFV, while displaying a broader spectrum of antiprotozoal activity, is metabolically less stable. In this work we designed, synthesized and characterized a set of close analogs and identified two new compounds (7 and 9) that exceed VNI/VFV in their spectra of antiprotozoal activity, microsomal stability, and pharmacokinetics (tissue distribution in particular) and, like VNI/VFV, reveal no acute toxicity.

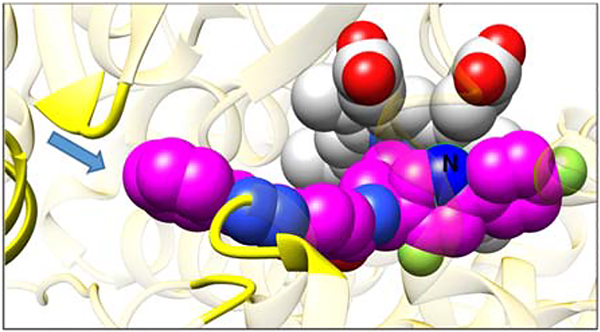

Table of Contents graphic

Introduction

Chagas disease, sleeping sickness, and leishmaniasis are three major neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) caused by protozoan parasites from the family Trypanosomatidae and transmitted to human by infected insect vectors (kissing bugs, tsetse flies, and female phlebotomine sandflies, respectively). Trypanosoma cruzi is the population of pathogens responsible for Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis), with >70 genetically highly variable strains being organized in six Distinct Typing Units (DTUs) termed TcI-TcVI. Depending on the strain, the disease varies in its progression, severity, most damaged organs (predominantly the heart, gastrointestinal tract, and nervous system), and susceptibility to treatment.1 To date the World Health Organization (WHO) has reported that 6 to 7 million people are estimated to be infected and more than 10, 000 deaths occur annually [http://www.who.int/chagas/epidemiology/en/]. Sleeping sickness, also called human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), is endemic in 36 sub-Saharan African countries and occurs in two forms, depending on the parasite species involved: Trypanosoma brucei gambiense or Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense. Approximately 70, 000 people are at high risk for infection in Africa, where, although the diagnosis should be fast to prevent the neurological progression of the disease, the healthcare funding resources are very limited [http://www.who.int/trypanosomiasis_african/country/en/]. Leishmaniasis can be caused by more than 20 Leishmania species and is manifested as a cutaneous, mucocutaneous, or visceral form. 700,000–1,000,000 new cases with 20,000–30,000 deaths per year are estimated [http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis]. Trypanosomatidae infections usually involve acute and chronic phases, and the currently available therapies display low efficacy (particularly for the chronic phase) and extremely poor tolerability. Although several efforts have been made by public research institutions as well as by some private companies for developing new, more potent, and safer drugs to treat these diseases, alternative and less toxic treatments options are still not approved.

In the past 20 years, repurposing antifungal azoles as potential anti-trypanosomatidae agents has been demonstrated to be one of the most successful strategies.2–8 Azoles kill fungal cells by inhibiting sterol 14α- demethylase (CYP51, EC 1.14.13.70), the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme required for biosynthesis of sterols.9 Similar to fungi, Trypanosomatidae synthesize endogenous sterols that are important structural components of their membranes and also serve as hormonal molecules that, acting at picomolar concentrations, modulate cell development, multiplication, and morphological transformation6,10–11. The Trypanosomatidae genomes encode all the enzymes of the sterol biosynthesis pathway.12 Nevertheless, being evolutionarily much older than fungi (estimated 1.5 billion years), Trypanosomatidae possess metabolic differences (and variability) that impose a set of additional requirements for azole-based drugs to be efficient, particularly pharmacokinetics (PK) and tissue distribution.

Thus, the recent outcomes and especially the interpretation (e.g., refs. 13–14) of clinical trials of the antifungal drug posaconazole15 and the antifungal drug candidate ravuconazole16 for chronic Chagas disease have discounted CYP51 inhibitors as antiprotozoal agents, diminished enthusiasm for new developments, and made it much more complicated, even for highly promising compounds to proceed to clinical trials. This situation is somewhat similar to that with the autoimmune hypothesis for Chagas disease, which significantly delayed progress in drug development.17

On the other hand, posaconazole and especially ravuconazole are known to have inherent PK issues (reviewed in Ref. 5), e.g. the maximal reported plasma concentration of posaconazole in mice (at a 40 mg/kg oral dose) was 6 μM,18 and the maximal concentration detected in humans was 5 to 10-fold lower19). Mostly due to the PK issues, even the efficiency of treatment of systemic fungal infections is generally <50% (i.e., >50% mortality rates20–21). Moreover, the chagasic patients in the clinical trials (20% success rate) were clearly underdosed, and the treatment period was too short,17, 22–24 in part due to cost of posaconazole. In our opinion, the shortcomings of posaconazole should not serve as a reason for the “highlighted by the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative′s (DNDi) decision not to pursue this class of inhibitors and try to ban them from the market”.25 In an attempt to support this decision, even a procedure designed to screen out (“de-prioritize”) CYP51 inhibitors from the high-throughput screening hits was developed.13 The procedure, however, so far is demonstrating that the most potent hits identified in the phenotypic screenings are still CYP51 inhibitors.26 Finally, it is important to note that antifungal azoles were first developed as drugs for topical treatment, long before the target enzyme was discovered and systemic fungal infections became a severe health issue.27

Using direct testing of inhibition of protozoan CYP51 orthologs, we identified a highly potent compound, VNI [(R)-N-(1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl)-4-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzamide)], whose inhibitory effect was functionally irreversible, completely blocking the T. cruzi and T. brucei CYP51 activity over extended period of time in vitro when added at an equimolar ratio to the enzyme.10 We later showed that, easy to synthesize and safe in vivo, VNI cured, with a 100% efficiency and a 100% survival, both the acute and chronic models of Chagas disease in mice infected with Tulahuen T. cruzi and displayed excellent PK properties when administered with 5% Arabic gum and 3% Tween 80.28–29 We also observed that VNI retarded, in a dose-dependent manner, parasitemia in mice infected with T. brucei, the extracellular pathogen that can utilize host cholesterol for the membranes and only requires endogenous (ergosterol-like) sterols for regulatory purposes.30 Unfortunately, however, VNI was less potent as an inhibitor of Leishmania infantum CYP5131 and Y strain T. cruzi CYP51A.32 The crystal structure of the CYP51-VNI complex revealed the molecular basis for its high potency,30 while the complex with the close analog VNF [4′-chloro-N-[(1R)-2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-1-phenylethyl]biphenyl-4-carboxamide]33 provided a direction for the compound redesign to broaden the spectrum of antiprotozoal activity, leading to the synthesis of VFV [(R)-N-(1-(3,4′-difluoro-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)-2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl)-4-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzamide].31 The additional phenyl ring, as anticipated, filled the deepest (formed by the B′C-loop, helix C, and the N-terminal portion of helix I34) cavity of the CYP51 active site, further increasing the strength of the interaction.32 Having a broader spectrum of activity as a protozoan CYP51 inhibitor, VFV (like VNI) cured Tulahuen T. cruzi infection in mice and showed increased efficacy when compared to VNI in murine models of visceral leishmaniasis35 and Chagas disease caused by the Y strain T. cruzi.36 VFV displayed better bioavailability and tissue distribution but was less metabolically stable than VNI.35

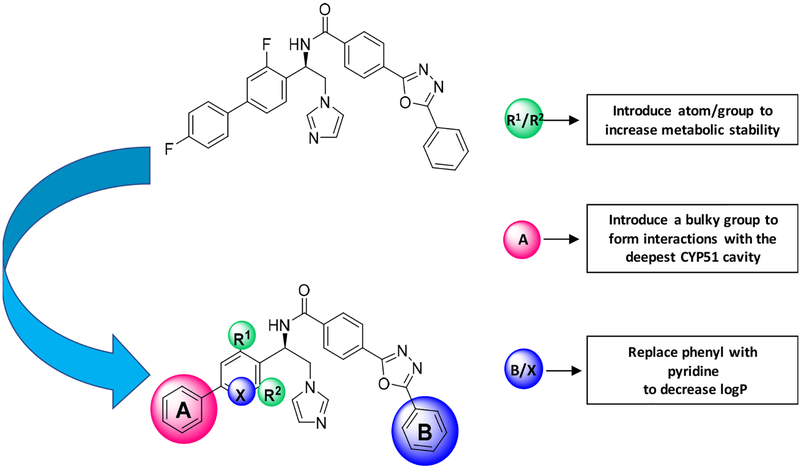

The purpose of the present investigation was to determine if and how small structural modifications (Figure 1) can overcome the minor disadvantages of VNI and VFV to produce a new compound that would have higher potential to rise above “the CYP51 deprioritization barrier” and move towards clinical trials as an antiprotozoal drug candidate.

Figure 1. VFV structure modification.

(see Figure 2 for details)

Results and Discussion

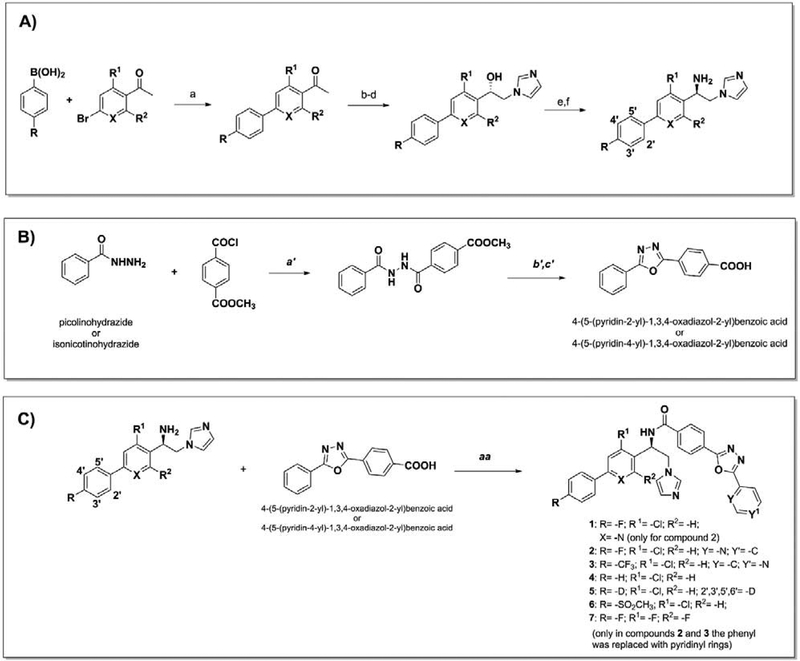

Synthesis.

After the initial Suzuki coupling performed using tetrakis (Pd(Ph3)4) as catalyst and various phenylboronic acid or acetophenones to modify the VFV biphenyl ring (Scheme 1A), VFV derivatives 1–7, VFV-Cl, and VNI derivatives 8 and 9 were synthesized as described previously.37 The phenyl ring replacement with pyridinyl- (to decrease LogP) was carried out by coupling of commercial picolinohydrazide (compound 2) or isonicotinohydrazide (compound 3) with methyl-4-(chlorocarbonyl)benzoate to synthesize the corresponding benzoic acid (Scheme 1B). The final coupling between the (R)-1-([1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)-2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethan-1-amine, variously substituted, and the corresponding acid led to compounds 1–7 (Scheme 1C). Structural formulas of the compounds are shown in Figure 2.

Scheme 1. A. Synthesis of 1–7.

Reagent and conditions: a) Pd(PPh3)4, Na2CO3, toluene/EtOH/H2O, reflux, 3 h, under argon. Yield 80% to quantitative. b) CuBr2, CHCl3/EtOAc, reflux 2 h. Yield 80%. c) Imidazole, DMF, 0 °C, 2 h. Yield 50–80%. d) RuCl(p-cymene)[(R,R)-Ts-DPEN], CH2Cl2 TEA, HCO2H, 40 °C, 26 h. Yield 80–90%. e) DMF, DPPA, DBU, 0 °C rising to room temperature, overnight, under argon. Yield 50–70%. f) THF, LiAlH4, room temperature overnight. Yield >99%. B. a′) THF, 6 h, at room temperature. b′) POCl3, reflux overnight, 85 °C. c′) LiOH·H2O, THF, CH3OH, H2O (3:1:1, v/v/v,), 3 h at room temperature. Yield 70–90%. C. aa) CH2Cl2, EDC/DMAP, room temperature, overnight, under argon. Yield 30–80%. Enantiomeric excess 97–99%.

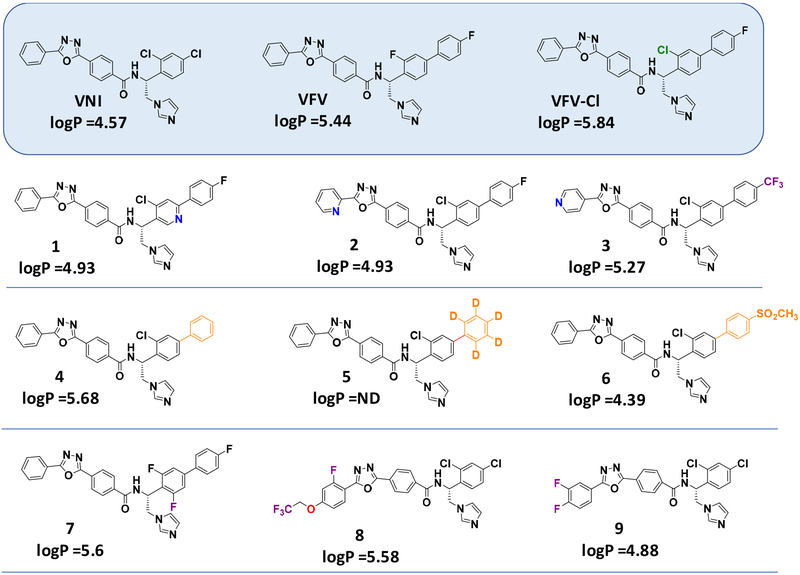

Figure 2.

Structural formulas of VNI, VFV and their analogs that have been synthesized and studied in this work

Initial Structural Modification Strategy.

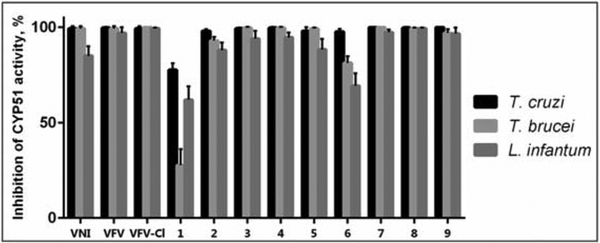

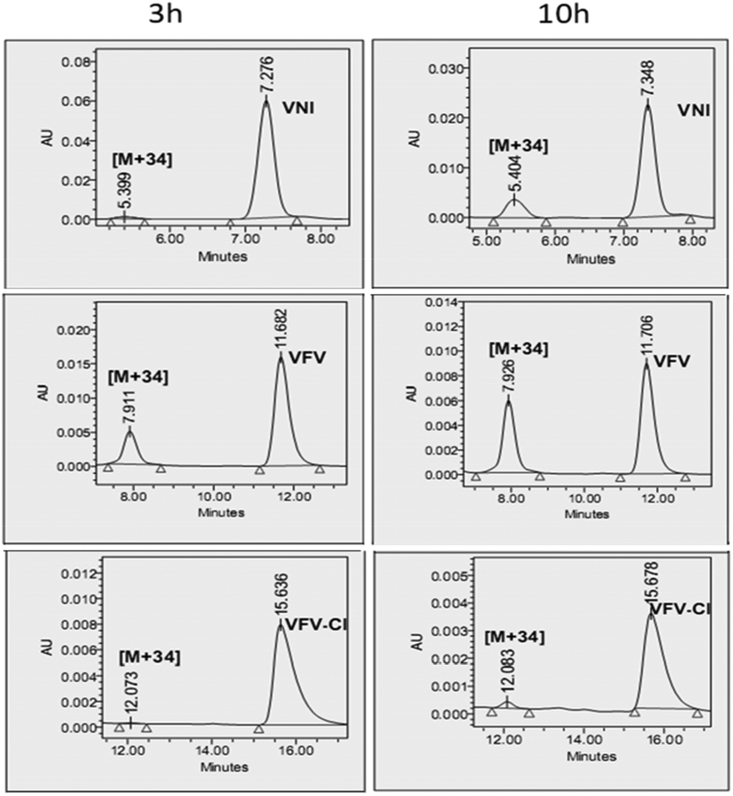

As we reported previously, both VNI and VFV, when extracted from the mouse plasma, displayed dihydroxylation of the imidazole rings (mass spectra [M+34])35. Because VNI was metabolically more stable than VFV and differed from VFV in that it contained a chlorine (instead of a fluorine) atom in close proximity to the site of metabolism, we hypothesized that the steric effect of the chlorine atom could play a favorable role. Thus, the first VFV structural modification was the replacement of 3-fluorine with 3-chlorine in the biphenyl arm. The results were very encouraging as the new compound (VFV-Cl) 1) preserved the “VFV-like” broad spectrum of activity, showing a complete inhibition of all three protozoan CYP51 enzymes tested at an equimolar ratio (inhibitor/enzyme) in a 1-hour reaction (Figure 3), and 2) displayed almost no metabolism (mass spectrum [M+34]) when extracted from mice plasma (Figure 4). Moreover, VFV-Cl was more stable than VFV in mouse and human liver microsomes (Table 1). A problem is that being quite hydrophobic (logP=5.84 (Figure 2)), it revealed lower oral bioavailability (i.e., the maximal plasma concentration (Cp, max) dropped to 13 μM (vs. 24 μM for VFV)) (Table 2). When given at 50 mg/kg VFV-Cl produced a plasma concentration profile comparable with that of VFV (at a dose of 25 mg/kg) (Figure S2) and its concentrations in tissues increased about 1.5-fold (data not shown), but the requirement for a higher dosage could not be considered as particularly positive. Therefore, we decided to further modify the structure to decrease the target compound hydrophobicity. Replacement of one phenyl ring with a pyridine ring appeared to be the most straightforward approach (compounds 1, 2, and 3, in Figure 2).

Figure 3. Inhibition of enzymatic activity of CYP51 from three protozoan pathogens at an equimolar ratio inhibitor/enzyme.

A 1-h reaction. The P450 concentration was 1 μM, the NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase was 2 μM, the concentration of the substrate (eburicol for the T. cruzi or obtusifoliol for T. brucei and L. infantum orthologs was 50 μM.

Figure 4. HPLC profiles of VNI, VFV, and VFV-Cl and their [M+34] metabolites extracted from mouse plasma 3 and 10-h after a single oral administration dose of 25 mg/kg.

The HPLC system was equipped with a Symmetry octadecylsilane C18 (3.5 μM) 4.6 mm × 75 mm column and a dual-wavelength UV 2489 detector was set at 291 and 250 nm. The mobile phase as 55% 0.01 M ammonium acetate (pH 7.4) and 45% acetonitrile (v/v) with an isocratic flow rate of 1.0 mL/min.

Table 1. Microsomal stability: half-lives and estimated clearance of the compounds in human, rat, and mouse liver microsomes.

(R2 values were all >0.7)

| Compound | Human | Rat | Mouse | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinta | Clhep | t½ (min)b | Clint | Clhep | t½ (min) | Clint | Clhep | t½ (min) | |

| VFV | 29.9 | 12.3 | 42 | 17.7 | 14.2 | 158 | 145 | 55.6 | 38 |

| VFV-Cl | 13.9 | 8.35 | 90 | 35.5 | 23.6 | 79 | 59.8 | 35.9 | 91 |

| 2 | 22.3 | 10.8 | 56 | 29.7 | 20.8 | 95 | 105 | 48.4 | 52 |

| 3 | 23.5 | 11.1 | 53 | 52.3 | 29.9 | 54 | 99.0 | 47.1 | 55 |

| 4 | 20.9 | 10.5 | 60 | 142 | 46.9 | 20 | 34.2 | 24.8 | 160 |

| 5 | 21.2 | 10.6 | 58 | 131 | 45.6 | 22 | 220 | 63.9 | 25 |

| 6 | 11.6 | 7.46 | 108 | 58.1 | 31.7 | 48 | 127 | 52.6 | 43 |

| 7 | 19.4 | 10.1 | 64 | 55.8 | 31.1 | 50 | 237 | 65.2 | 23 |

| 8 | 16.5 | 9.24 | 76 | 64.3 | 33.5 | 48 | 87.7 | 44.4 | 62 |

| 9 | 7.53 | 5.54 | 166 | 30.9 | 21.4 | 91 | 55.8 | 34.5 | 98 |

Estimated intrinsic (Clint) and hepatic clearance (Clhep) expressed in mL/min/kg body weight,

in vitro half-life values in minutes.

Table 2. Comparative pharmacokinetic parameters.

Balb/c mice, single oral dose 25 mg/kg

| Cmpds | Plasma | Tissue distribution, 4 hours after administration, μM (±SEM), n=2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cp, max, μM | Life time, hours* | Brain | ||||||

| VFV | 24 | >24 | 1 ± 0.2 | |||||

| VFV-Cl | 13 | 16 | 0.2 | |||||

| 2 | 5 | 10 | 0.1 | |||||

| 3 | nd** | nd | nd | |||||

| 4 | 28 | <10 | 0.1 | |||||

| 5 | 15 | <16 | 0.2 | |||||

| 6 | nd | nd | nd | |||||

| 7 | 25 | >24 | 3 ± 1 | |||||

| 8 | 7 | 6 | 0.15 | |||||

| 9 | 38 | 16 | 8 ± 4 | |||||

the time until the compound becomes undetectable;

below 0.1 μM, which is the detection limit;

high concentration of 7 in the liver might compensate for its relatively weaker stability in mouse liver microsomes (Table 1).

Effects of Modifications on Compound Potency as CYP51 Inhibitors, Microsomal Stability, and Pharmacokinetic Properties.

Of the three pyridine-containing analogs, only compound 1 displayed a dramatic decrease in its potency to inhibit all three protozoan CYP51 (Figure 3), thus indicating that the electron-rich nucleophilic nitrogen atom in the proximal ring of the biphenyl arm of the inhibitor molecule (1-(pyridin-3-yl), which in the CYP51 structure lies in close proximity to the aliphatic portion of the heme ring D propionate (Figure 5), is clearly unfavorable, while both the ortho- (5-(pyridin-2-yl) and para- (5-(pyridin-4-yl) substitutions in the distal ring of the three-ringed side chain of the molecule (compounds 2 and 3) might be acceptable. Unfortunately 2 and 3 displayed very poor PK properties (Table 2), presumably due to lower oral bioavailability (for both compounds) and in addition due to the rapid (possibly intestinal) metabolic degradation of compound 3 (identified by LC-MS as glucuronidation of the N-pyridinyl site (5-(pyridin-4-yl) [M803], data not shown).

Figure 5. Expected (VFV-based) position of the 1-(pyridin-3-yl) nitrogen atom (marked as N) of compound 1 in the CYP51 structure.

The carbon atoms of the heme and the inhibitor are light gray and magenta, respectively. Oxygens are red, nitrogens are blue, chlorines and fluorines are green. The arrow shows entrance into the enzyme access channel. The protein ribbon around the entrance is yellow, the rest of the ribbon is semitransparent gold.

Compound 4 was designed for decreased hydrophobicity (as a result of the absence of one fluorine atom in the biphenyl arm) to improve bioavailability without enhancing biotransformation. A higher Cp,max was achieved (28 μM 2 hours after administration (plasma concentration profile shown in Figure S2)), but the compound was rapidly metabolized and its concentration in tissues four hours after administration was lower than that of VFV-Cl, except for the liver (Table 2). The decision to synthesize compound 5, where the hydrogens in the distal biphenyl ring were replaced with deuteriums (the [1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl- with [1,1’-biphenyl]-4-yl-2’,3’,4’,5’,6’-d5) was made based on the information in the literature suggesting that deuterated compounds could be metabolically more stable presumably because cleavage of the C-D covalent bond requires higher energy than C-H bond, making a drug last longer and improving its toxicity profile.38–40 Thus, in 2016 the first deuterated drug deutetrabenazine (Teva Pharmaceutical) was approved by FDA.36 In our case, however, the deuteration did not improve but rather worsened the situation (Table 2, plasma concentration profile is shown in Figure S2). Although the decrease in the detectable amount of 5 appeared to be slightly slower, we assume this could be due to its 2-fold lower Cp,max because a lower rate of metabolism at lower drug concentration is typical for first-order PK.

We next synthesized compound 6 because the methylsulfonyl group is generally considered metabolically stable (e.g. Ref. 41) and it also has a significantly decreased logP (4.39). The compound, however, was a weaker T. brucei and L. infantum CYP51 inhibitor, and no trace of it was observed in the plasma or tissues (except for the intestine, where its concentration two hours after administration was ~130 μM (data not shown)). Thus, 6 is not orally bioavailable, and we did not test i.v. administration at this point because, in order to kill intracellular parasites, a drug molecule should be able to effectively penetrate both the host tissues and the pathogen membranes, which azole drugs are believed to do by diffusion.42

Finally, because the fluorine atom in the distal ring of the biphenyl arm of the VFV molecule was important, observably slowing down biotransformation, we prepared compound 7, where the second fluorine atom was added to the proximal ring of the biphenyl arm (3,4′,5-trifluoro-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl). This compound completely inhibited all tested protozoan CYP51 enzymes (Figure 3), including the Y strain T. cruzi CYP51A (Figure S1) and revealed very promising PK properties, particularly tissue accumulation, where its average concentration was >2.5-fold greater that of VFV (Table 2).

Oddly enough, in some cases there was an apparent discrepancy between the PK properties in vivo and microsomal stability in vitro, e.g. compounds 2–4 and 6 showed poor PK properties in mice but in mouse liver microsomes displayed stability higher than VFV (Table 1). We assume this might be connected with their increased polarity (total polar surface area (tPSA)): 91 Å2 for 2 and 3, and 112 Å2 for 6, while for VFV and other compounds it is 78 Å2 (ChemDraw Professional version 16.0). High tPSA may negatively affect not only intestinal absorption but also (though perhaps to a lesser degree) microsomal membrane permeability so that only some portions of the compound molecules would be subject to microsomal metabolism, though the lack of in vitro-in vivo correlation could also be due to additional mechanisms of metabolism that are not captured in liver microsomes (i.e., cytosolic).

Compounds 8 and 9, two VNI derivatives (one phenyl ring instead of the biphenyl arm (Figure 2)) initially designed as inhibitors of fungal CYP51,37 were included in this study because upon testing against the protozoan CYP51 orthologs they both were also found to be highly potent (Figure 3). Again, while the PK properties of compound 8 (tPSA =88 Å2) were rather moderate, compound 9 (tPSA =78 Å2) had excellent bioavailability and tissue distribution. Quite remarkably, its concentration in the brain four hours after a single administration reached 8 μM, the highest amongst all tested analogs.

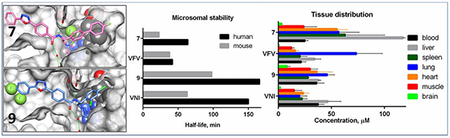

Compounds 7 and 9, whose PK properties as well as stabilities in human liver microsomes were superior to their parent compounds VFV and VNI (Tables 1, 2), were selected for further studies.

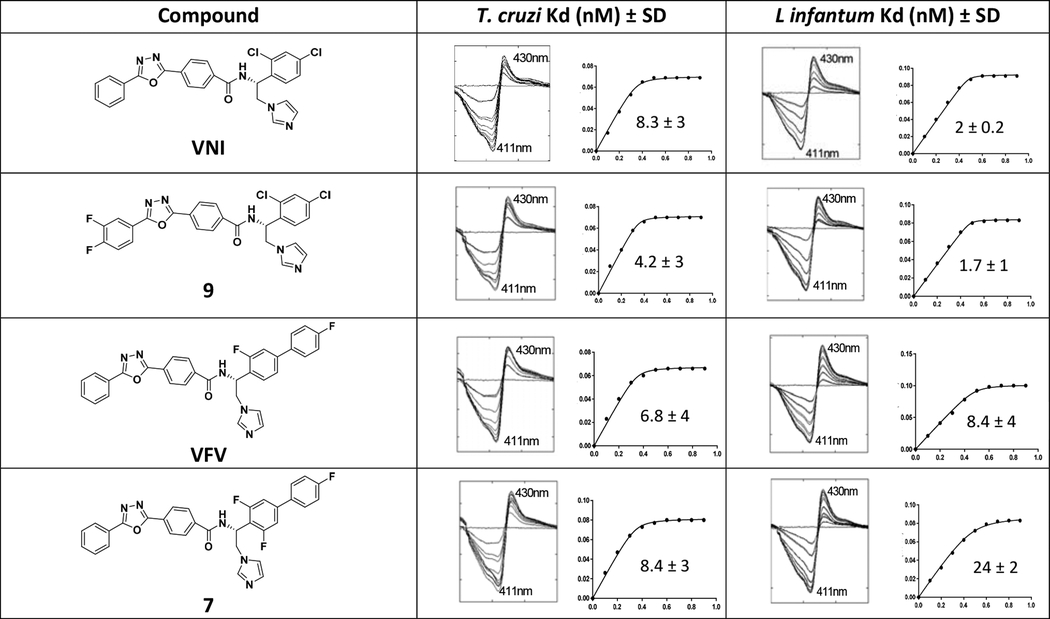

Validation of Compounds 7 and 9 as CYP51 Tight Binding Ligands.

Binding of heterocyclic molecules, such as azole or pyridine derivatives, causes a red shift in the Soret band maximum of the CYP51 absorbance spectra. The shift reflects the replacement of a water molecule from the coordination sphere of the catalytic heme iron by a more basic heterocyclic nitrogen atom, and therefore is often used to confirm the binding event and can also be used to estimate the apparent affinity of a ligand to the enzyme.43 Spectral titrations of Y strain T. cruzi CYP51A and L. infantum CYP51 with 7 and 9 characterized both compounds as being tight binding ligands with affinities in the low nanomolar concentration range and saturation being achieved at an approximately equimolar ratio to the enzymes (Table 3).

Table 3. Titration of Y-T. cruzi CYP51A and L. infantum CYP51 with Compounds 7 and 9.

VNI and VFV were used as positive controls. CYP51 concentration was 0.5 μM, concentration range of the inhibitors was 0.1–1 μM. Titration curves axes: X, concentration range of the inhibitors (0.1 −1 μM); Y, absorbance changes in the difference spectra Δ(A430-A411).

|

Antiparasitic Effects in Amastigotes of Tulahuen and Y Strains of T. cruzi.

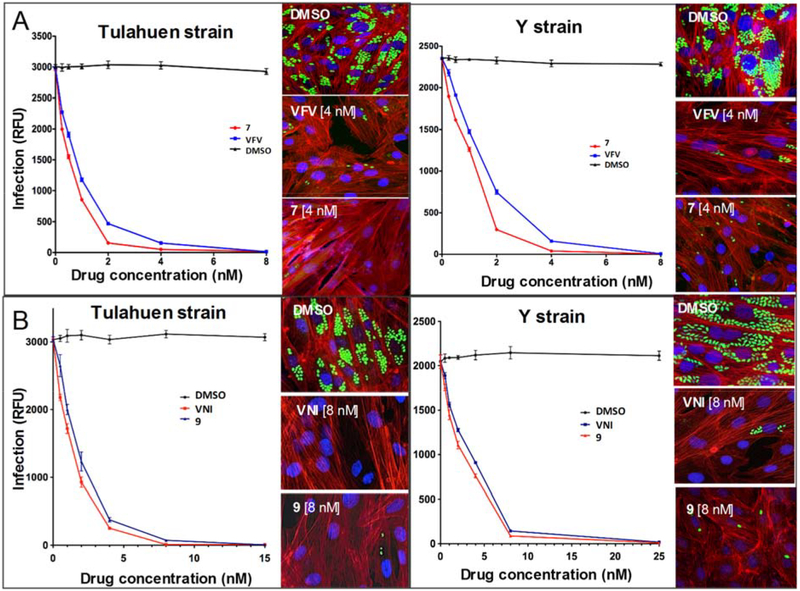

The antiparasitic activity of compounds 7 and 9 against T. cruzi cells was analyzed in amastigotes, the most clinically relevant, intracellular form of the parasite, by quantifying rate of multiplication within infected cardiomyocytes (Figure 6). The dose-response curves indicated that both compounds had remarkable antiparasitic activity, clearing both Tulahuen and Y T. cruzi infections at low nanomolar concentrations. The EC50 values in Tulahuen T. cruzi infection were: compound 7 - 0.5 nM (VFV - 1 nM), compound 9 - 1.6 nM (VNI - 1.3 nM). The EC50 values in Y T. cruzi infection were: compound 7 - 1 nM (VFV - 1.5 nM), compound 9 - 3 nM (VNI - 4 nM). Although the differences between the parent compounds and the derivatives were not big, they were statistically significant (p values between EC50 values determined using two-way-ANOVA analysis of variance were <0.05), and a correlation between the stronger potency of 9 to inhibit Y strain CYP51A enzyme activity (Figure S1), its higher binding affinity to Y CYP51A (Table 3), and its relatively stronger antiparasitic effect towards the Y strain infection of cardiomyocytes was observed. Thus, compounds 7 and 9 are clearly not inferior to VNI and VFV in their abilities to kill T. cruzi parasites within mammalian cells.

Figure. 6. Efficiencies of compounds 7 (A) and 9 (B) in clearing cardiomyocite infection by the Tulahuen and Y strains of T. cruzi.

Cardiomyocyte monolayers were infected with green fluorescent protein-expressing trypomastigotes of the Tulahuen or Y strain for 24 hours and then treated with different concentrations of 7, 9, or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). VFV and VNI were used as controls. Parasite multiplication within monolayers was monitored as green fluorescent protein fluorescence (expressed in relative fluorescence units [RFU]) 72 hours after infection. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and the experimental points represent the mean ± SEs from triplicate experiments. Insets. Fluorescence microscopic observations of T. cruzi parasites inside cardiomyocytes 72 hours after infection. T. cruzi amastigotes are green, cardiomyocyte nuclei are blue, and cardiomyocyte actin filaments are red.

Acute Toxicity in vivo.

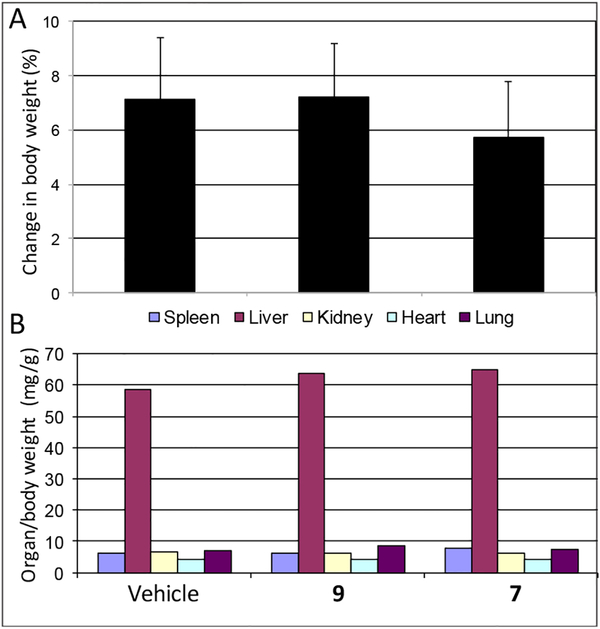

As we found previously, both VNI and VFV, when tested in mice at oral doses up to 200 mg/kg, displayed no acute toxicity31, 36 and did not show any observable adverse effects upon treatment in mouse models of Chagas disease and visceral leishmaniasis at 25 mg/kg,28, 35–36 a feature that is of great importance for a potential therapeutic agent. Although the introduced structural changes in compounds 7 and 9 are very minor (only the addition of one (7) or two (9) fluorine atoms, which in the CYP51-inhibitor complexes are positioned above the heme iron and at the entrance into the substrate access channel, respectively (Figure 2 and Table of Content Graphic)), before considering them for testing in mouse models of Trypanosomatidae infections, we compared these compounds with VNI and VFV in the rapid acute toxicity assay (a 200 mg/kg oral dose). No detectable side effects were noticed by clinical observation (including animal behavior, motility, neurological conditions, skin and fur profile), and no statistically significant alterations were registered by body/organ weight analysis (Figure 7) or biochemical plasma measurements (Table S1). Altogether the data indicate that, similar to VNI and VFV, compounds 7 and 9 are well tolerated, displaying a low toxicity profile (NOAEL (no-observable-adverse-effect-level) > 200 mg/kg) and therefore can serve as promising drug candidates for antiprotozoan chemotherapy. Large scale synthesis of these compounds is currently in progress and will be followed by preclinical testing in T. brucei and Leishmania cells and in animal models of Chagas disease, sleeping sickness,30 and vis ceral leishmaniaisis.35

Figure 7. Acute toxicity assay of compounds 9 and 7 after a single oral dose of 200 mg/kg.

A. Mean± SD values (n=3) showing the change in animal body weight (0–48 h posttreatment). B. Mean ± SD values showing organ weight (normalized according to each individial body weight) 48 h after compounds administration.

Conclusions

The results obtained in this study show that most of the CYP51 structure-directed modifications did not affect the ability of the VFV and VNI analogs to inhibit the target enzymes and even enhanced their stability in liver microsomes, yet some of them drastically influenced the compounds PK. Thus, we have demonstrated that knowledge on the structure/function of the therapeutic target can be highly helpful in resolving the issue of inhibitory potency, making the process of drug discovery much more rational (vs. time and efforts-consuming random SAR investigations), because only the most potent compounds can be selected for further optimization of their drug-like properties at early stages of drug development. In two examples, fluconazole has excellent PK properties but is a rather weak reversible CYP51 inhibitor, which raises the probability of resistance, and it took Pfizer 14 years and > 12,000 derivatives to develop voriconazole.21 Posaconazole, on the contrary, happened to be a highly potent inhibitor of CYP51 orthologs across phylogeny, but its use is limited by PK issues.5 Although it is still our belief that both VNI and VFV, regardless of their minor flaws, deserve testing in clinical trials, the two new compounds that this study produced, 7 and 9, are more promising. Of course, extensive in vivo experiments44 will be required to evaluate their true potential. Their higher affinities to tissues should be particularly favorable for eradication of intracellular pathogens (Chagas disease and leishmaniasis). Moreover, the ability of compound 9 to penetrate the blood/brain barrier indicates that it might be of special interest for the chronic stage of sleeping sickness, for relapses in immunosuppressed chagasic patients (in whom severe neurological damage is frequent, especially when associated with HIV infection), and quite likely can provide treatment for human diseases caused by other protozoan pathogens, such as amoebiasis, particularly for infections with Naegleria fowleri (the deadly “brain-eating amoeba”). One minor but very important advantage for all of our four compounds is that, due to their specific absorbance at 291 nm, their disposition can be easily monitored in vivo. It is also worth mentioning that the differences between the stability of some compounds in human, mouse and rat liver microsomes may serve as a clue for different outcomes of preclinical animal studies and clinical trials, including those for Chagas disease.

Experimental Section.

Chemical Synthesis.

All reagents and solvents were commercial grade and were purchased from Fisher Scientific, Sigma-Aldrich, Santa Cruz, or Alpha Aesar.1 H NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker AVANCE-400 MHz spectrometer in CDCl3 and DMSO-d6 at 25 °C. Chemical shift values are given in δ (ppm) relative to TMS as an internal standard. Coupling constants are given in Hz. The following abbreviations are used to set multiplicities: s = singlet, d = doublet, dd= double of doublets, m = multiplet. Compounds were purified by flash chromatography using silica gel high purity grade, pore size 60 Å 230–400 mesh particle size, 40–63 μm (Sigma-Aldrich). The final compounds were filtered through HF Bond Elut-SCX cartridges (500 mg, 6 mL, Agilent Technologies), using an ammonia solution (2.0 M in methanol, Sigma-Aldrich). LC-MS (UV and ESI-MS) and reversed-phase HPLC were used for analyzing the purity of the compounds (> 95%). Analytical LC-MS was performed on an Agilent 1200 series instrument with UV detection at 214 and 254 nm, along with ELSD detection. General LC-MS parameters were as follow: Phenomenex-C18 Kinetex octadecylsilane column, 50 mm × 2.1 mm, 2 min gradient, 5% (0.1% TFA/CH3CN)/95% (0.1% TFA/H2O) to 100% (0.1% TFA/CH3CN) (all v/v). High resolution mass spectrometry was performed by direct liquid infusion using an Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo-Finnigan, San Jose, CA) equipped an Ion-Max source housing and a standard electrospray (ESI) ionization probe in positive ionization mode at a resolving power of 30,000 (at m/z 400). ESI source parameters were as follows: spray voltage, 5 kV; N2 sheath gas, 8; auxiliary gas, 0; capillary voltage, 35 V; tube lens voltage, 108 V at 675 m/z. The reversed-phase HPLC system (Waters) was equipped with a dual-wavelength UV 2489 detector set at 250 and 291 nm (VNI-specific absorption maximum, ϵ291 36 mM −1 cm−1) and a Symmetry C18 (3.5 μm) 4.6 mm × 75 mm octdecylsilane column.28 The mobile phase consisted of 55% 15mM ammonium acetate solution (pH 7.4) and 45% CH3CN (v/v) with an isocratic flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The enantiomeric excess (e.e.) of the final compounds was evaluated by analytical chiral chromatography on a Chiralpak IB-3 column, 250 mm × 4.6 mm i.d. (Daicel Corporation, Japan) using a Waters HPLC system with the detector set at 250 and 291 nm. As eluent, a solution of hexane, ethanol, diethylamine, and ethylenediamine, (ratio 70:30:0.1:0.1, v/v/v/v) was used, and the flow rate was 0.7 mL/min.

General method for preparing 1–9.

Synthesis of different substituted 1-([1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)ethan-1-ones.

(Step 1). Differently substituted bromoacetophenones (1 equiv.) were dissolved in toluene (10 mL), then aqueous Na2CO3 (2M, 5 mL), and selected boronic acid (1 equiv) previously dissolved in EtOH (9 mL), were added dropwise. The reaction mixture was frozen using liquid N2 and degassed under reduced pressure three times before adding Pd(Ph3)4 (0.5 mol %). Subsequently the resulting suspension was heated under reflux for 3 hours. After cooling, the solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 20 mL), washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and filtered. The organic solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the crude product was purified by flash chromatography (hexane/EtOAc, 9:1, v/v) affording the various 1-([1,1´-biphenyl]-4-yl)ethan-1-ones as white solids, isolated in 80–90% yield.

Synthesis of the final compounds.

(Step 2–7). Reaction steps 2–7, as well the synthesis of the appropriate 4-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzoic acid (step 8) were carried out according to the procedure described previously.37

(R)-N-(1-(3-Chloro-4´-fluoro-[1,1´-biphenyl]-4-yl)-2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl)-4-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzamide.

(VFV-Cl). Yield 50 %. 1·H NMR (CDCl3): δ ppm 8.22 (d, J= 7.7 Hz, 2H), 8.15 (dd, J= 8.0, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.94 (d, J= 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.64 (d, J= 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.59–7.50 (m, 5H), 7.43 (dd, J= 8.0, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.25 (s, 1H) (overlapped with CDCl3), 7.15 (t, J=8.6 Hz, 3H),7.09 (s,1H), 6.92 (s, 1H), 5.90–5.86 (m, 1H), 4.60 (d, J= 6.0 Hz, 2H). LCMS, found [M+H]+ m/z 563.8. ESI MS, mass calcd for C32H23ClFN5O2 [M]+ 564.1597, found Mobs 564.1596.

(R)-N-(1-(4-Chloro-6-(4-fluorophenyl)pyridin-3-yl)-2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl)-4-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzamide (Compound 1).

Yield 20%. 1·H NMR (CDCl3): δ ppm 10.4 (brs, 1H), 9.89 (s, 1H), 9.70 (s, 1H), 8.21 (d, J= 6.5 Hz, 2H), 8.09 (s, 3H), 8.00 (d, J= 6.6 Hz, 4H), 7.68 (s, 1H), 7.52–7.45 (m, 3H), 7.20 (s, 3H), 6.23 (brs, 1H), 5.73 (brs, 1H), 5.00 (brs, 1H). LCMS, found [M+H]+ m/z 565.9. ESI MS, mass calcd for C31H22ClFN6O2 [M]+ 565.1550, found Mobs 565.1545.

(R)-N-(1-(3-Chloro-4´-fluoro-[1,1´-biphenyl]-4-yl)-2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl)-4-(5-(pyridin-2-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzamide (Compound 2).

Yield 30%. 1·H NMR (CDCl3): δ ppm 8.83 (d, J= 5.0 Hz, 1H), 8.34–8.29 (m, 3H), 7.94–7.91 (m, 3H), 7.64 (d, J= 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.53–7.49 (m, 3H), 7.41 (dd, J= 8.0, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.34 (s, 1H), 7.21 (d, J= 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.16–7.12 (m, 3H), 7.04 (s, 1H), 6.90 (s, 1H), 5.85 (dd, J= 14.3, 7.0 Hz, 1H), 4.59 (d, J= 6.4 Hz, 2H). LCMS, found [M+H]+ m/z 565.5. ESI MS, mass calcd for C31H22ClFN6O2 [M]+ 565.1550, found Mobs 565.1544. HPLC, tR 5.8 min, purity 99%. Enantiomeric excess 99%.

(R)-N-(1-(3-Chloro-4´-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1´-biphenyl]-4-yl)-2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl)-4-(5-(pyridin-4-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzamide (Compound 3).

Yield 30%. 1·H NMR (CDCl3): δ ppm 10.1 (s, 1H),9.68 (d, J= 8.6 Hz, 1H), 8.92 (d, J= 6.0 Hz, 2H), 8.10–8.08 (m, 4H), 7.95 (d, J= 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J= 8.4 Hz, 2H),7.71 (d, J= 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.67 (d, J= 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (d, J= 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.59–7.57 (m, 2H), 7.47 (s, 1H), 7.06 (s, 1H), 6.17–6.12 (m, 1H), 5.36 (dd, J= 14.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (dd, J= 14.0, 3.0 Hz, 1H). LCMS, found [M+H]+ m/z 615.18. ESI MS, mass calcd for C32H22ClF3N6O2 [M]+ 615.1518, found Mobs 615.1519. HPLC, tR 14.0 min, purity 99%. Enantiomeric excess > 99%.

(R)-N-(1-(3-Chloro-[1,1´-biphenyl]-4-yl)-2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl)-4-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzamide (Compound 4).

Yield 60%. 1·H NMR (CDCl3): δ ppm 8.37 (d, J= 5.8 Hz, 1H), 8.20 (s, 1H), 8.108.03 (m, 6H), 7.65 (d, J= 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.55–7.51 (m, 5H), 7.47–7.37 (m, 5H), 7.12 (s, 2H), 6.01–5.97 (m, 1H), 4.88 (dd, J= 13.7, 9.0 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (dd, J= 14.0, 5.0 Hz, 1H). LCMS, found [M+H]+ m/z 546.9. ESI MS, mass calcd for C32H24ClN5O2 [M]+ 546.1691, found Mobs 546.1685. HPLC, tR 14.6 min, purity > 99%. Enantiomeric excess 97%.

(R)-N-(1-(3-Chloro-[1,1´-biphenyl]-4-yl-2´,3´,4´,5´,6´-d5)-2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl)-4-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzamide (Compound 5).

Yield 80%. 1·H NMR (CDCl3): δ ppm 8.32 (d, J= 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (s, 1H), 8.09–8.06 (m, 4H), 8.02 (d, J= 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.64 (d, J= 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.56–7.50 (m, 4H), 7.44 (dd, J= 8.0, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.09 (s, 2H), 6.01– 5.96 (m, 1H), 4.85 (dd, J= 14.0, 8.7 Hz, 1H), 4.51 (dd, J= 14.0, 5.1 Hz, 1H). LCMS, found [M+H]+ m/z 552.0. ESI MS, mass calcd for C32H19D5ClN5O2 [M]+ 551.2005, found Mobs 551.2011. HPLC, tR 15.2 min, purity > 99%. Enantiomeric excess > 98%.

(R)-N-(1-(3-Chloro-4´-(methylsulfonyl)-[1,1´-biphenyl]-4-yl)-2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl)-4-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzamide (Compound 6).

Yield 55%. 1·H NMR (CDCl3): δ ppm 9.80 (s, 1H),9.62 (d, J= 8.6 Hz, 1H), 8.14–8.09 (m, 4H), 8.03–7.98 (m, 3H), 7.90 (d, J= 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.72 (d, J= 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.68 (d, J= 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.56–7.51 (m, 4H), 7.46 (s, 1H), 7.37 (s, 1H), 6.18– 6.12 (m, 1H), 5.32 (dd, J= 14.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H), 4.42 (dd, J= 14.0, 32 Hz, 1H), 3.1 (s, 3H). LCMS, found [M+H]+ m/z 623.8. ESI MS, mass calcd for C33H26ClN5O4S [M]+ 624.1467, found Mobs 624.1476. HPLC, tR 4.0 min, purity >99%. Enantiomeric excess >99%.

(R)-N-(2-(1H-Imidazol-1-yl)-1-(3,4´,5-trifluoro-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)ethyl)-4-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzamide (Compound 7).

Yield 60%. 1·H NMR (CDCl3): δ ppm 8.76 (s, 1H), 8.16–8.10 (m, 5H), 8.05 (d, J= 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.58–7.47 (m, 5H), 7.16–7.12 (m, 6H), 6.13–6.07 (m, 1H), 5.06 (dd, J= 14.0, 8.8 Hz, 1H), 4.44 (dd, J= 14.0, 5.6 Hz, 1H). LCMS, found [M+H]+ m/z552.0. ESI MS, mass calcd for C32H22F3N5O2 [M]+ 566.1798, found Mobs 566.1799. HPLC, tR 18.0 min, purity > 99%. Enantiomeric excess 97%.

(R)-N-(1-(2,4-Dichlorophenyl)-2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl)-4-(5-(2-fluoro-4-(2,2,2-trifluoroethoxy)phenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzamide (Compound 8).

Yield 40%. 1·H NMR (CDCl3): δ ppm 9.79 (s, 1H), 9.47 (d, J=8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (t, J= 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.02 (d, J= 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.80 (dd, J= 8.3, 3.4 Hz, 3H), 7.45 (d, J= 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (s, 1H), 7.38 (s, 1H), 7.34 (dd, J= 8.4, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.94–6.86 (m, 2H), 6.07–6.02 (m, 1H), 5.23 (dd, J= 13.6, 12.4 Hz, 1H), 4.49–4.39 (m, 3H). LC-MS, found [M+H]+ m/z 618.10. ESI MS, mass calcd for C28H19Cl2F4N5O3 [M+H]+ 620.0874, found Mobs 620.0875. HPLC, tR 17.6 min, purity 99%. Enantiomeric excess >97%.

(R)-N-(1-(2,4-Dichlorophenyl)-2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl)-4-(5-(3,4-difluorophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzamide (Compound 9).

Yield 50 %. 1·H NMR (CDCl3): δ ppm 9.97 (s, 1H), 9.55 (d, J= 8.8 Hz, 1H), 8.04 (d, J= 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.98–7.89 (m, 2H), 7.79 (dd, J= 8.3, 5.2 Hz, 3H), 7.47–7.45 (m, 2H), 7.40–7.35 (m, 3H), 6.08–6.04 (m, 1H), 5.27 (dd, J= 13.8, 12.0 Hz, 1H), 4.41 (dd, J= 14.0, 3.2 Hz, 1H). LC-MS, found [M+H]+ m/z 539.8. ESI MS, mass calcd for C26H17Cl2F2N5O2 [M+H]+ 540.0800, found Mobs 540.0807. HPLC, tR 11.6 min, purity 98%. Enantiomeric excess > 97%.

CYP51 activity and ligand binding assays.

CYP51 enzymes from T. brucei, Tulahuen T. cruzi, L. infantum and CYP51A from Y T. cruzi were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified as described previously32, 34, 45–46). The enzymatic reaction mixture contained 1 μM P450, 2 μM T. brucei NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase, 100 μM L-α−1,2-dilauroyl-sn-glycerophosphocholine, 0.4 mg/mL isocitrate dehydrogenase, and 25 mM sodium isocitrate in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 10% glycerol (v/v). After addition of the radiolabeled ([3-3H]) sterol substrate (eburicol for T. cruzi and obtusifoliol for T. brucei and L. infantum CYP51), final concentration 50 μM, and an inhibitor, final concentration 1.1 μM, the mixture was preincubated for 60 seconds at 37 °C in a shaking water bath, the reaction was initiated by the addition of 100 μM NADPH and stopped by extraction of the sterols with EtOAc. The extracted sterols were dried, dissolved in CH3OH, and analyzed using a reversed-phase HPLC system (Waters) equipped with a β-RAM detector (INUS Systems, Inc.) using a NovaPak octadecylsilane (C18) column and a linear gradient of H2O:CH3CN:CH3OH (1.0:4.5:4.5, v/v/v) (Solvent A) to CH3OH (Solvent B), increasing from 0 to 100% B for 30 min at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The inhibitory potencies of VFV and derivatives were compared as percentage of inhibition of sterol 14α-demethylation in 60-min reactions;37 the molar ratio inhibitor/enzyme/substrate in the reaction mixture was 1.1:1:50. The experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results are presented as means ± SD. Spectral titrations of L. infantum CYP51 and Y strain T. cruzi CYP51A with VFV, VNI, and compounds 7 and 9 were carried out in 5 cm optical path length cuvettes at 0.5 μM P450 concentration as previously described.32 The apparent dissociation constants of the enzyme-inhibitor complex were calculated using GraphPad Prism 6 software by fitting the hyperbolic data for the ligand-induced absorbance changes in the difference spectra Δ(Amax-Amin) versus ligand concentration to the Morrison (quadratic) equation (tight-binding ligands, nonlinear regression).

Microsomal stability assay.

Microsomal stabilities of VFV and derivatives were evaluated as reported earlier using human (mixed gender), rat (male Sprague-Dawley), or mouse (male CD-1) pooled liver microsomes (0.5 mg/mL, BD Biosciences) and 1 μM test compound.37 The experiments were performed in triplicate. The in vitro half-life (t1/2, min, Eq. 1), estimated intrinsic clearance (CLINT, mL/min/kg, Eq. 2) and subsequent predicted hepatic clearance (CLHep, mL/min/kg, Eq. 3) were determined employing the following equations:

| (1) |

where k represents the slope from linear regression analysis of the natural log percent remaining of test compound as a function of incubation time

| (2) |

ascaling factor

| (3) |

where Qh (hepatic blood flow) is 21 mL/min/kg for human, 70 mL/min/kg for rat, and 90 mL/min/kg for mouse.

PK and tissue distribution assay.

The pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution were studied using the previously developed protocol that is based on the VNI-specific absorption maximum at 291 nm (ϵ291 36 mM− 1 cm−1), which makes this inhibitory scaffold easy to monitor in vivo, with a detection limit of 0.1 μM.28 The compounds were given to BALB/c mice (Jackson Laboratory) by oral gavage as a single dose of 25 mg/kg. Fresh solutions were prepared from 10% (w/v) stocks of the compounds in DMSO by dissolving them in sterile 5% Arabic gum in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 3% Tween 8035 because the bioavailability of VNI and VFV given from this formulation has been found ~3-fold higher than from the solutions in 20% hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (Guedes da Silva et al., ACS Inf.Dis, revision submitted, Manuscript ID id-2018–002537.R1). To obtain the drug plasma concentration profiles, the blood samples were collected over time (1, 2, 4, 6, 10, 16, and 24 hours after administration). Blood samples of untreated animals (with and without added compounds) were used as controls. The tissues were collected four hours after administration as described.35 For the blood analysis, 30 μL samples of plasma were diluted to 100 μL with PBS, mixed with 100 μl of CH3CN containing 10 μM ketoconazole (used as an internal standard), the mixture was vortexed, and the drugs were extracted with 300 μl of extraction solution containing 80% CH3CN and 20% water (v/v). After centrifugation at 16,000 g for 10 min, the supernatant was transferred to a new tube and dried. For the analysis the samples were redissolved in the 500 μL of solvent composed of 50% CH3CN and 50% water (v/v) and analyzed by HPLC. The HPLC system was equipped with the dual-wavelength UV 2489 detector (Waters) set at 291 and 250 nm and a Symmetry C18 (3.5 μm) 4.6 × 75 mm octdecylsilane column. The mobile phase was 55% 0.01 M ammonium acetate (pH 7.4) and 45% CH3CN (v/v) with an isocratic flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. For the tissue distribution analysis, prior to drug extraction approximately 100 mg of each tissue was diluted 5-fold with PBS and homogenized using an IKA Ultra Turrax T8 tissue homogenizer (The Lab World Group, USA), and 100 μL of the homogenate samples was used for the extraction and analysis, as described for plasma (see above). The identities of the compounds extracted from plasma were confirmed by LC-MS as described for VNI and VFV.35

Cellular assays in Tulahuen and Y strains of T. cruzi.

The cellular T. cruzi infection assay was performed using Tulahuen and Y strains of T. cruzi expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP). Trypomastigotes were generated as described33 and used to infect cardiomyocyte monolayers in 96-well tissue culture plates and in 8-well LabTech tissue culture chambers in triplicate at a ratio of 10 parasites per cell as described previously.28, 47 Cultures were incubated with Dulbecco′s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) as described.28 Unbound trypomastigotes were removed by washing the cellular monolayers with DMEM, and infected monolayers were exposed to several concentrations of the inhibitors (from 0.5 nM to 25 nM), dissolved in DMSO/DMEM (free of phenol red) in triplicate at 24 h of infection and co-cultured in DMEM plus 10% FBS for 48 h to observe parasite multiplication. VFV and VNI were used as controls. At 72 h after infection the cardiomyocyte monolayers were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and the infection was fluorometrically quantified as relative fluorescence units (RFU) using a Synergy HT fluorometer (Biotek Instruments).47 For fluorescence microscopy observation, the infection assays were performed in 8-well LabTech tissue culture chambers in triplicate. At 72 h after infection the cardiomyocyte monolayers were fixed with 2.5% paraformaldehyde (w/v) and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole to visualize DNA, and with Alexa fluor 546 phalloidin (Invitrogen) to visualize cardiomyocyte actin myofibrils as described previously.28

Mouse acute toxicity assay.

Swiss Webster mice (21–23 g) were obtained from the Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (ICTB-FIOCRUZ) animal facilities (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). Mice were housed at a maximum of 6 animals per cage and kept in a conventional room at 20–24 °C under a 12/12 h light/dark cycle. The animals were provided with sterilized water and chow ad libitum and all procedures were carried out in accordance with the guidelines established by the FIOCRUZ Committee of Ethics for the Use of Animals (CEUA 0028/0909 and CEUA LW16/14) as described.48 To evaluate the acute toxicity, 200 mg/kg of body weight of the compound were given orally as described above for the PK assay, and the treated animals (n=3) were inspected for toxic and sub-toxic symptoms according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) guidelines. Forty-eight hours after compound administration, mice were euthanized and their blood and organs collected for weight and body size analysis and hematological and biochemical measurements as reported at ICTB/Fiocruz platform (Fiocruz/RJ).31

Ethics.

The procedures dealing with mice used for the PK analysis were approved by the IACUC of Meharry Medical College and the procedures involving mice used for the acute toxicity assay were approved by the FIOCRUZ Committee of Ethics for the Use of Animals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment:

The work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (GM067871, G.I.L.), the toxicity studies were supported by grants from Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. MNCS is research fellow of CNPq and CNE research.

Abbreviations Used:

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- CYP51

sterol 14α-demethylase

- EC50

inhibitor concentration that decreases the parasite growth by 50%

- tetrakis

palladium-tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)

- Log P

n-octanol/water partition coefficient

- tPSA

total polar surface area

- Cp,max

maximal plasma concentration

- DBU

1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene

- ESI

Electrospray ionization

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- LiOH·H2O

lithium hydroxide monohydrate

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- equiv.

equivalent

- h

hours

- Hz

Hertz

- J

coupling constant (in NMR spectrometry)

- tR

retention time (in chromatography)

- TMS

tetramethylsilane

- DMAP

4-(N,N-dimethylamino)pyridine

- EDC/HCl

N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride

Footnotes

Supporting Information:

The Supporting Information includes two supplementary tables: Table S1 (Biochemical analysis of blood samples of compounds 9 and 7-treated mice) and Table S2 (HRMS [M+H]+ calculated, observed and difference in ppm) and four supplementary figures: Figure S1. HPLC profiles of radiolabeled sterols extracted after CYP51 reaction, Figure S2. Plasma concentration curves, Figure S3. 1·H NMR spectra, Figure S4. HRMS spectra (PDF), and Molecular Formula Strings (CSV).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Filardi LS; Brener Z Susceptibility and Natural Resistance of Trypanosoma cruzi Strains to Drugs Used Clinically in Chagas Disease. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg 1987, 81, 755–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Urbina JA; Payares G; Contreras LM; Liendo A; Sanoja C; Molina J; Piras M; Piras R; Perez N; Wincker P; Loebenberg D Antiproliferative Effects and Mechanism of Action of SCH 56592 Against Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi: In Vitro And In Vivo Studies. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother 1998, 42, 1771–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Urbina JA; Payares G; Molina J; Sanoja C; Liendo A; Lazardi K; Piras MM; Piras R; Perez N; Wincker P; Ryley JF Cure of Short- And Long-Term Experimental Chagas′ Disease Using D0870. Science 1996, 273, 969–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Pinazo MJ; Espinosa G; Gállego M; López-Chejade PL; Urbina JA; Gascón J Successful Treatment with Posaconazole of a Patient with Chronic Chagas Disease and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hig 2010, 82, 583–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Lepesheva GI; Friggeri L; Waterman MR CYP51 as Drug Targets for Fungi and Protozoan Parasites: Past, Present and Future. Parasitology 2018, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Lepesheva GI; Waterman MR Sterol 14α-Demethylase (CYP51) as a Therapeutic Target for Human Trypanosomiasis and Leishmaniasis. Curr. Top. Med. Chem 2011, 11, 2060–2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Paniz Mondolfi AE; Stavropoulos C; Gelanew T; Loucas E; Perez Alvarez AM; Benaim G; Polsky B; Schoenian G; Sordillo EM Successful Treatment of Old World Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Caused by Leishmania infantum With Posaconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011, 55, 1774–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Leslie M Drug Developers Finally Take Aim at a Neglected Disease. Science 2011, 333, 933–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lepesheva GI; Waterman MR Sterol 14α-Demethylase Cytochrome P450 (CYP51), a P450 in All Biological Kingdoms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1770, 467–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Lepesheva GI; Ott RD; Hargrove TY; Kleshchenko YY; Schuster I; Nes WD; Hill GC; Villalta F; Waterman MR Sterol 14α-Demethylase as a Potential Target for Antitrypanosomal Therapy: Enzyme Inhibition and Parasite Cell Growth. Chem Biol. 2007, 14, 1283–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Roberts CW; McLeod R; Rice DW; Ginger M; Chance ML; Goad LJ Fatty Acid and Sterol Metabolism: Potential Antimicrobial Targets in Apicomplexan and Trypanosomatid Parasitic Protozoa. Mol. Boichem. Parasitol 2003, 126, 129–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Berriman M; Ghedin E; Hertz-Fowler C; Blandin G; Renauld H; Bartholomeu DC; Lennard NJ; Caler E; Hamlin NE; Haas B; Böhme U; Hannick L; Aslett MA; Shallom J; Marcello L; Hou L; Wickstead B; Alsmark UCM; Arrowsmith C; Atkin RJ; Barron AJ; Bringaud F; Brooks K; Carrington M; Cherevach I; Chillingworth T-J; Churcher C; Clark LN; Corton CH; Cronin A; Davies RM; Doggett J; Djikeng A; Feldblyum T; Field MC; Fraser A; Goodhead I; Hance Z; Harper D; Harris BR; Hauser H; Hostetler J; Ivens A; Jagels K; Johnson D; Johnson J; Jones K; Kerhornou AX; Koo H; Larke N; Landfear S; Larkin C; Leech V; Line A; Lord A; MacLeod A; Mooney PJ; Moule S; Martin DMA; Morgan GW; Mungall K; Norbertczak H; Ormond D; Pai G; Peacock CS; Peterson J; Quail MA; Rabbinowitsch E; Rajandream M-A; Reitter C; Salzberg SL; Sanders M; Schobel S; Sharp S; Simmonds M; Simpson AJ; Tallon L; Turner CMR; Tait A; Tivey AR; Van Aken S; Walker D; Wanless D; Wang S; White B; White O; Whitehead S; Woodward J; Wortman J; Adams MD; Embley TM; Gull K; Ullu E; Barry JD; Fairlamb AH; Opperdoes F; Barrell BG; Donelson JE; Hall N; Fraser CM; Melville SE; El-Sayed NM The Genome of the African Trypanosome Trypanosoma brucei. Science 2005, 309, 416–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Riley J; Brand S; Voice M; Caballero I; Calvo D; Read KD Development of a Fluorescence-Based Trypanosoma cruzi CYP51 Inhibition Assay for Effective Compound Triaging in Drug Discovery Programmes for Chagas Disease. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 2015, 9, e0004014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Chatelain E; loset J-R Phenotypic Screening Approaches for Chagas Disease Drug Discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov 2018, 13 (2), 141–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Molina I; Gómez i Prat J; Salvador F; Treviño B; Sulleiro E; Serre N; Pou D; Roure S; Cabezos J; Valerio L; Blanco-Grau A; Sánchez-Montalvá A; Vidal X; Pahissa A Randomized Trial of Posaconazole and Benznidazole for Chronic Chagas′ Disease. N. Eng. J. Med 2014, 370 (20), 1899–1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Torrico F, Gascon J, Ortiz L, Alonso-Vega C, Pinazo MJ, Schijman A, Almeida IC, Alves F, Strub-Wourgaft N, Ribeiro I, E1224 Study Group. Treatment of Adult Chronic Indeterminate Chagas Disease with Benznidazole and Three E1224 Dosing Regimens: A Proof-of-concept, Randomised, Placebo-controlled Trial. Lancet. Infect. Dis 2018, 18(4), 419–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Urbina JA Recent Clinical Trials for the Etiological Treatment of Chronic Chagas Disease: Advances, Challenges and Perspectives. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol 2015, 62, 149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Rodriguez MM; Pastor FJ; Calvo E; Salas V; Sutton DA; Guarro J Correlation of In Vitro Activity, Serum Levels, and In Vivo Efficacy of Posaconazole Against Rhizopus microsporus in a Murine Disseminated Infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2009, 53, 5022–5025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Li Y; Theuretzbacher U; Clancy CJ; Nguyen MH; Derendorf H Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Profile of Posaconazole. Clin. Pharmacokinet 2010, 49 (6), 379–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Brown GD; Denning DW; Gow NAR; Levitz SM; Netea MG; White TC Hidden Killers: Human Fungal Infections. Sci. Trans. Med 2012, 4, 165rv13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Denning DW; Bromley MJ How to Bolster the Antifungal Pipeline. Science 2015, 347, 1414–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Molina I; Salvador F; Sánchez-Montalvá A, The Use of Posaconazole Against Chagas Disease. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis 2015, 28, 397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Urbina JA, The Long Road Towards a Safe and Effective Treatment of Chronic Chagas Disease. Lancet. Infect. Dis 2018, 18 (4), 363–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Urbina JA, Pharmacodynamics and Follow-Up Period in the Treatment of Human Trypanosoma Cruzi Infections With Posaconazole. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 2017, 70 (2), 299–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Chatelain E Chagas Disease Drug Discovery: Toward a New Era. J Biomol Screen. 2015, 20 (1), 22–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Sykes ML; Avery VM 3-Pyridyl Inhibitors With Novel Activity Against Trypanosoma cruzi Reveal In Vitro Profiles Can Aid Prediction of Putative Cytochrome P450 Inhibition. Sci. Rep 2018, 8 (1), 4901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Heeres J; Meerpoel L; Lewi P Conazoles. Molecules 2010, 15, 4129–4188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Villalta F; Dobish MC; Nde PN; Kleshchenko YY; Hargrove TY; Johnson CA; Waterman MR; Johnston JN; Lepesheva GI VNI Cures Acute and Chronic Experimental Chagas Disease. J. Infect. Dis 2013, 208, 504–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Dobish MC; Villalta F; Waterman MR; Lepesheva GI; Johnston JN Organocatalytic, Enantioselective Synthesis of VNI: A Robust Therapeutic Development Platform for Chagas, a Neglected Tropical Disease. Org. Lett 2012, 14, 6322–6325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Lepesheva GI; Park HW; Hargrove TY; Vanhollebeke B; Wawrzak Z; Harp JM; Sundaramoorthy M; Nes WD; Pays E; Chaudhuri M; Villalta F; Waterman MR Crystal Structures of Trypanosoma brucei Sterol 14α-Demethylase and Implications for Selective Treatment of Human Infections. J. Biol. Chem 2010, 285, 1773–1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Hargrove TY; Kim K; de Nazare Correia Soeiro M; da Silva CF; Batista DD; Batista MM; Yazlovitskaya EM; Waterman MR; Sulikowski GA; Lepesheva GI CYP51 Structures and Structure-Based Development of Novel, Pathogen-Specific Inhibitory Scaffolds. Internat. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist 2012, 2, 178–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Cherkesova TS; Hargrove TY; Vanrell MC; Ges I; Usanov SA; Romano PS; Lepesheva GI Sequence Variation in CYP51A from the Y Strain of Trypanosoma cruzi Alters its Sensitivity to Inhibition. FEBS Lett. 2014, 588, 3878–3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Lepesheva GI; Hargrove TY; Anderson S; Kleshchenko Y; Furtak V; Wawrzak Z; Villalta F; Waterman MR Structural Insights into Inhibition of Sterol 14α-Demethylase in the Human Pathogen Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Biol. Chem 2010, 285, 25582–25590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Hargrove TY; Wawrzak Z; Liu J; Nes WD; Waterman MR; Lepesheva GI Substrate Preferences and Catalytic Parameters Determined by Structural Characteristics of Sterol 14α-Demethylase (CYP51) from Leishmania Infantum. J. Biol. Chem 2011, 286, 26838–26848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Lepesheva GI; Hargrove TY; Rachakonda G; Wawrzak Z; Pomel S; Cojean S; Nde PN; Nes WD; Locuson CW; Calcutt MW; Waterman MR; Daniels JS; Loiseau PM; Villalta F VFV as a New Effective CYP51 Structure-Derived Drug Candidate for Chagas Disease and Visceral Leishmaniasis. J. Inf. Dis 2015, 212, 1439–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Guedes-da-Silva FH; Batista DG; Da Silva CF; De Araujo JS; Pavao BP; Simoes-Silva MR; Batista MM; Demarque KC; Moreira OC; Britto C; Lepesheva GI; Soeiro MN Antitrypanosomal Activity of Sterol 14α-Demethylase (CYP51) Inhibitors VNI and VFV in the Swiss Mouse Models of Chagas Disease Induced by the Trypanosoma cruzi Y Strain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2017, March 24;61(4). pii: e02098–16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02098-16. Print 2017 Apr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Friggeri L; Hargrove TY; Wawrzak Z; Blobaum AL; Rachakonda G; Lindsley CW; Villalta F; Nes WD; Botta M; Guengerich FP; Lepesheva GI Sterol 14α-Demethylase Structure-Based Design Of VNI (( R)-N-(1-(2,4-Dichlorophenyl)-2-(1 H-Imidazol-1-Yl)Ethyl)-4-(5-Phenyl-1,3,4-Oxadiazol-2-Yl)Benzamide)) Derivatives to Target Fungal Infections: Synthesis, Biological Evaluation, and Crystallographic Analysis. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61, 5679–5691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Mullard A Deuterated Drugs Draw Heavier Backing. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2016, 15, 219–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Tung RD Deuterium Medicinal Chemistry Comes of Age. Future Mmed. Chem 2016, 8, 491–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Schmidt C First Deuterated Drug Approved. Nat. Biotechnol 2017, 35, 493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Lucking U Sulfoximines: A Neglected Opportunity in Medicinal Chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2013, 52, 9399–9408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Esquivel BD; Smith AR; Zavrel M; White TC Azole Drug Import into the Pathogenic Fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2015, 59, 3390–3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Lepesheva GI; Villalta F; Waterman MR Targeting Trypanosoma cruzi Sterol 14α-Demethylase (CYP51). Adv. Parasitol 2011, 75, 65–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Croft SL, Leishmania and Other Intracellular Pathogens: Selectivity, Drug Distribution and PK-PD. Parasitology 2018, 145 (2), 237–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Lepesheva GI; Nes WD; Zhou W; Hill GC; Waterman MR CYP51 from Trypanosoma brucei Is Obtusifoliol-Specific. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 10789–10799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Lepesheva GI; Zaitseva NG; Nes WD; Zhou W; Arase M; Liu J; Hill GC; Waterman MR CYP51 from Trypanosoma cruzi: a Phyla-Specific Residue in the B′ Helix Defines Substrate Preferences of Sterol 14α-Demethylase. J. Biol. Chem 2006, 281, 3577–3585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Johnson CA; Rachakonda G; Kleshchenko YY; Nde PN; Madison MN; Pratap S; Cardenas TC; Taylor C; Lima MF; Villalta F Cellular Response to Trypanosoma cruzi Infection Induces Secretion of Defensin A–1, which Damages the Flagellum, Neutralizes Trypanosome Motility, and Inhibits Infection. Infect. Immun 2013, 81, 4139–4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Soeiro M. d. N. C.; de Souza EM; da Silva CF; Batista D. d. G. J.; Batista MM; Pavão BP; Araújo JS; Lionel J; Britto C; Kim K; Sulikowski G; Hargrove TY; Waterman MR; Lepesheva GI In Vitro And In Vivo Studies of the Antiparasitic Activity of Sterol 14α-Demethylase (CYP51) Inhibitor VNI Against Drug-Resistant Strains of Trypanosoma cruzi. Anatimicrob. Agents Chemother 2013, 57, 4151–4163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.