Abstract

Friends and family members’ reactions to intimate partner violence (IPV) disclosure play an important role in social support because disclosure often precedes requests for support. Perceptions of social reactions to IPV disclosure are likely to vary by context. Yet, research is limited on the role of ethnicity and severity of physical violence in perceptions of social reactions. We examined perceptions of social reactions to IPV disclosure using data from Wave 6 interviews for Project HOW: Health Outcomes of Women. Participants (N = 201) were asked proportionately how many friends and family reacted positively and negatively to IPV disclosure. MANOVAs revealed significant differences in perceptions of positive social reactions by ethnicity and severity.

Keywords: social reactions, intimate partner violence disclosure, community women, ethnic differences

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a major public health concern that affects many women. Women’s lifetime prevalence of physical violence is estimated to be 31.5%, and 22.3% of women experience at least one act of severe physical violence by an intimate partner (Breiding, 2015). IPV (i.e., psychological abuse, physical violence, sexual aggression, and stalking) can result in poor physical and psychological health (Coker et al., 2002). The World Health Organization estimated that approximately half of the women involved in a violent relationship are physically injured by their romantic partner (García-Moreno, 2013). Many women who are physically injured by IPV experience multiple injuries (Amar & Gennaro, 2005; Muelleman, Lenaghan, & Pakieser, 1996; Sheridan & Nash, 2007). Furthermore, women who experience IPV have increased risk for a number of mental health issues (Fredland et al., 2015).

Psychological trauma and stress related to IPV may be one mechanism that drives a number of mental health consequences (García-Moreno, 2013; Martinez-Torteya et al., 2009). These symptoms align with mental health disorders commonly discussed within the IPV literature, including depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety, all of which are positively associated with women’s experiences of IPV (Avanci, Assis, & Oliveira, 2013; Bennice, Resick, Mechanic, & Astin, 2003; Beydoun, Beydoun, Kaufman, Lo, & Zonderman, 2012; Dillon, Hussain, Loxton, & Rahman, 2013; V. J. Edwards, Black, Dhingra, McKnight-Eily, & Perry, 2009; Golding, 1999). In their review of IPV and health outcomes, Dillon and colleagues (2013) highlight that researchers have found that more severe IPV is associated with more severe symptoms of depression, PTSD, and anxiety. However, social support can act as a buffer against poor health outcomes commonly associated with IPV (Coker et al., 2002; Coker, Watkins, Smith, & Brandt, 2003).

Social Support

Many women who experience IPV seek support (Sylaska & Edwards, 2014). Social support has been defined in many ways; Finfgeld-Connett (2005) defines social support as an interpersonal process that is centered upon a context-specific exchange of information. Emotional support specifically consists of comforting gestures and communication aimed at alleviating or soothing negative affect (Finfgeld-Connett, 2005). Not only is social support generally protective against IPV (Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim, 2012), but some researchers have also found that social support is associated with reduced risk of mental and physical health concerns in women who report IPV (Coker et al., 2002; Coker et al., 2003). In terms of mental health, social support reduces risk for anxiety, depression, PTSD, suicide ideation, and suicide attempts (Bryant-Davis, Ullman, Tsong, & Gobin, 2011; Coker et al., 2002). Moreover, social support appears to have a dose–response relationship, indicating that greater social support is associated with better mental health (Escribà-Agüir et al., 2010; Mburia-Mwalili, Clements-Nolle, Lee, Shadley, & Yang, 2010). Although social support has many benefits, seeking support can be intimidating for many women (Sylaska & Edwards, 2014).

Only a small proportion of women who experience IPV seek help from formal sources (Fanslow & Robinson, 2010). However, women are likely to have discussed IPV with informal sources such as friends or family (K. M. Edwards, Dardis, & Gidycz, 2012; Fanslow & Robinson, 2010; Sylaska & Edwards, 2014). Studies have found that up to 95% of women disclose to at least one person (Levendosky et al., 2004), most often a friend (Amar & Gennaro, 2005; K. M. Edwards et al., 2012). The quality of an individual’s social support is likely to be affected by the social reactions that individual receives in response to IPV disclosure (Levendosky et al., 2004). Therefore, initial reactions by informal sources of support to IPV disclosure are of critical importance as disclosure is predictably an antecedent to receiving social support.

Social Reactions to IPV Disclosure

While disclosure is an important mechanism to initiate social support, there are many perceived barriers to IPV disclosure including shame, fear, denial, embarrassment, privacy concerns, and concerns about receiving negative social reactions (K. M. Edwards et al., 2012; Evans & Feder, 2016). IPV disclosure is often stigmatized, which may present a barrier to seeking support (Overstreet & Quinn, 2013). Furthermore, the literature suggests that individuals who experience IPV may feel stigmatized by others based on actual or expected negative social reactions, for example, blaming or dismissing the discloser (Murray, Crowe, & Overstreet, 2018). These barriers may result in minimization of violence, partial disclosure (Dunham & Senn, 2000), or indirect disclosure (Williams & Mickelson, 2008). In the context of IPV, partial disclosure may consist of an individual minimizing violence, for example, disclosing while purposely omitting information (Dunham & Senn, 2000). Indirect disclosure, in the context of IPV, typically involves trying to seek support while keeping the IPV hidden (Williams & Mickelson, 2008). However, indirect disclosure may sometimes include partial disclosure (Williams & Mickelson, 2008). In partial disclosure, the goal is to minimize the IPV, whereas in indirect disclosure the goal is to maintain ambiguity in an effort to reduce stigmatization. Regardless of the degree of disclosure, it is important for potential support providers to react positively to best provide social support and help the discloser. The discloser’s perception of those reactions is potentially more important than the provider’s intended social reaction because it is likely that the perception of those reactions can affect health outcomes (Sullivan, Schroeder, Dudley, & Dixon, 2010).

The act of disclosing typically elicits a social reaction in response; however, disclosure does not guarantee that support will be provided (Belknap, Melton, Denney, Fleury-Steiner, & Sullivan, 2009). A social reaction can be defined as the way in which informal support providers respond both verbally and nonverbally to the discloser (Ullman, 2000). Social reactions from informal support providers are often grouped into two categories: positive/helpful and negative/unhelpful (Ullman, 1999, 2010). Positive social reactions can include emotional support and allowing the discloser to talk; negative social reactions may include blaming the discloser or disbelief (Sylaska & Edwards, 2014). Women are likely to encounter both when disclosing IPV experiences (Coker et al., 2002; Goodkind, Gillum, Bybee, & Sullivan, 2003; Sylaska & Edwards, 2014; Trotter & Allen, 2009). Social reactions to IPV disclosure are related to well-being (Sylaska & Edwards, 2014); overall, negative social reactions are harmful and positive social reactions are helpful or show no relation to mental health (K. M. Edwards, Dardis, Sylaska, & Gidycz, 2015). This, at the very least, emphasizes the importance of providing nonnegative social reactions. Until recently, social reactions to IPV disclosure had been largely understudied (K. M. Edwards et al., 2015), but there are indications that differences in women’s perceptions of social reactions are likely to differ based on context.

Severity of Physical IPV and Disclosure

Women are more likely to disclose as physical IPV severity increases; similarly, as violence frequency and number of physical injuries increase, women’s rates of disclosure also increase (Ansara & Hindin, 2010; Bachman & Coker, 1995; Barrett & Pierre, 2011; Flicker et al., 2011; Johnson & Leone, 2005; Leone, Lape, & Xu, 2014; Levendosky et al., 2004; Sylaska & Edwards, 2014). It is possible that as IPV severity increases, the individuals involved appraise and acknowledge IPV as a problem, thus causing the individual to be more inclined to seek help (Liang, Goodman, Tummala-Narra, & Weintraub, 2005). As severity of physical violence increases, women may feel more stigma or embarrassment about disclosing and these feelings are likely to bias their perceptions of others’ social reactions. For instance, Sullivan and colleagues (2010) note that disclosure recipients may subconsciously endorse just-world beliefs–i.e., the belief that in general people get what they deserve–and thus overattribute the cause of violence to the victim. While this is possible for disclosure recipients, it is also possible for individuals who experience violence and hold just-world beliefs to subconsciously blame themselves. This may further affect perceptions of others’ reactions to IPV disclosure.

Given the positive correlation between IPV severity and disclosure, it appears that women seek help when they perceive the violence they are experiencing as more severe or physically dangerous. Positive social reactions are not only important for mental health, but also in how women perceive or label their relationship violence and whether or not they choose to disclose again (Liang et al., 2005). However, researchers have found a positive relationship between violence severity and perceptions of negative social reactions (Sullivan et al., 2010). Taken together, these findings highlight the mismatch between what is needed from disclosure recipients and what the discloser perceives.

Women’s Ethnicity and Disclosure

Unfortunately, little is known about the racial and ethnic factors that play into women’s IPV disclosures and perceptions of social reactions (Montalvo-Liendo, 2009). Compared with White women, African American (AA) women (Kaukinen, 2004) and Hispanic women (West, Kantor, & Jasinski, 1998) are less likely to seek support for IPV. Latinas tend to differ on identification and disclosure of IPV (Ahrens, Rios-Mandel, Isas, & del Carmen Lopez, 2010). For instance, cultural factors may stigmatize disclosure and make identifying instances of IPV difficult (Ahrens et al., 2010). Kaukinen (2004) suggests that racial differences in help seeking may be due to racial differences in how women stigmatize victimization and how they respond to violence trauma.

The well-established association between low-income status and IPV further complicates the issue of IPV, ethnicity, and disclosure. Researchers have identified the relationship between IPV and poverty as bidirectional, indicating that being poor can increase women’s risk for IPV and experiencing IPV can increase women’s risk for poverty (Goodman, Smyth, Borges, & Singer, 2009). The link between IPV and low-income status has been found across samples (Vest, Catlin, Chen, & Brownson, 2002). Among Euro-American (EA), AA, and Hispanic cohabitating couples, annual household income had the strongest relationship with IPV compared with all other predictors (employment, education, alcohol problems/use, approval of violence, childhood victimization, impulsivity, and other relationship variables; Cunradi, Caetano, & Schafer, 2002). Not only are low-income women at higher risk of IPV, but they are also at higher risk for mental health issues (Belle, 1990). While both IPV and low-income status can independently lead to poor mental health, it is likely that a cumulative effect of IPV and low income exists, increasing the need for social support while making it more difficult to obtain it (Golin et al., 2017). Low-income women experiencing IPV may struggle with disclosing due to a number of barriers such as stress, powerlessness, social isolation, and fear of losing resources (Goodman et al., 2009). In summary, the perception of social reactions from support providers may be of greater importance to low-income women experiencing IPV.

Current Study

IPV disclosure is likely to be informal, yet friends and family may not be equipped to appropriately respond to IPV disclosure. Therefore, social reactions to disclosure can vary quite a bit. This can result in either positive or negative mental health consequences for the discloser. Women who perceive negative social reactions may experience the cumulative negative effects of IPV, negative social reactions, and low social support. The current study was designed to examine differences in low-income community women’s perceptions of others’ reactions to IPV disclosure.

The primary aim of the study was to test for hypothesized differences between groups in women’s perceptions of social reactions to IPV disclosure by (a) the severity of IPV women experienced, and (b) women’s race/ethnicity. First, we expected that women who reported moderate or severe physical IPV would perceive a greater proportion of negative social reactions and a smaller proportion of positive reactions than women who experienced threats but not physical IPV. Second, while we anticipated differences between AA, EA, and Mexican American (MA) women, we were not certain in what direction differences would most likely occur and we expected there would be potential for an interaction between IPV severity and race/ethnicity.

While research suggests disclosure is less likely by AA and MA women, we know less about support seeking for IPV. Therefore, a secondary aim of this study was to explore differences by ethnicity in IPV disclosure. We examined quantitative differences by ethnicity in number of people disclosed to and frequency of disclosure. We also explored to whom women disclosed using qualitative data.

Method

To address both study aims, we analyzed data from a larger study, Project HOW: Health Outcomes of Women. Project HOW is a longitudinal study conducted from 1995-2003. In a series of six interviews, 835 low-income AA, EA, and MA women were asked scaled and open-ended questions about their male partners, friends, family, work, health, and childhood experiences. The overall focus of the study was IPV; we therefore asked women many related questions about social reactions to disclosure of violence and violence severity.

Participants

There were three main requirements for Wave 1 participation. At Wave 1, participants had to (a) be between the ages of 20 and 49, (b) be in a heterosexual relationship for at least 1 year, and (c) have a household income less than twice the poverty threshold or be a recipient of public aid. When the first wave of data was collected in 1995, the poverty threshold (i.e., 100% of poverty) was US$15,150 for a family of four. Thus, to be in the study, participants with a family of four had to make less than US$30,300 or be receiving any form of public aid. In addition, participants were required to self-identify as AA, EA, or MA. Hispanic women whose families were from other races (e.g., Puerto Rican, Cuban, or Central or South American) were excluded from the study due to likely differences in socialization and acculturation. During screening, MA women who were interested in the study were only included if they were born in or attended school in the United States because the use of the rating scales is likely to be familiar only to fairly acculturated women. Women were not screened for violence, but inclusion criteria increased the likelihood of exposure to IPV. The only requirement for subsequent waves was Wave 1 participation. Women in Project HOW were generally representative of low-income women of the same ethnicity. (See Honeycutt, Marshall, & Weston, 2001, for more information on the representativeness of the full sample.)

For the current study, Wave 6 data (collected in 2003) were analyzed. Although the original sample size was larger (N = 621 at Wave 6), data were available only for those who completed the social reactions measure (n = 360) at Wave 6 due to interviewer error. All data were collected using face-to-face interviews (see procedures). Prior to the social reactions section of the interview, interviewers were prompted to skip to a later section if participants’ responses fit the skip criteria. Unfortunately, some interviewers skipped too far ahead, resulting in a smaller sample size available for analysis. After excluding participants who reported no violence since the previous wave of data collection, our final sample size was 201. On average, these 201 women were 40.3 years old and living at an average of 193.4% of the poverty threshold, still within the originally required 200% of poverty. While being in a committed relationship of at least 1 year was a Wave 1 requirement, by Wave 6, 22% participants were no longer in a relationship and 78% were in a relationship. Wave 6 participants were AA (39.5%), EA (29.9%), and MA (30.6%).

Procedures

Participants were recruited from low-income areas of the Dallas metroplex through the distribution of flyers (at apartments, churches, schools, health clinics, laundromats, libraries, local businesses, and through mass mailings). Female students recruited volunteers at public locations (shopping centers, flea markets, and health and employment fairs). Participants also referred their friends and family to participate in the study. All participants were screened based on eligibility criteria before scheduling interviews.

Each wave of data collection occurred approximately 1 year apart (M = 11.26 months). Interview length and incentives varied for each wave, although participants in all waves received monetary compensation. Wave 6 consisted of an approximately 4-hr interview, and participants were reimbursed with US$75, a gift bag, and a keychain with the Project HOW logo.

Participants were introduced to interviewers using only their first name or a nickname. Office workers and interviewers did not discuss participant information with one another. Interviewers did not have access to any information that could be used to identify participants. In addition, interviewers and office workers were naive to the central purpose of the study, hypotheses, and research questions focusing on partner violence.

The study used structured interviews conducted by undergraduate and graduate student interviewers. Interviewers completed extensive training and were closely monitored by graduate research assistants (RAs) in counseling and clinical psychology programs. Training consisted of item-by-item explanations on how each question should be asked and when to ask conditional questions. Interviewers were trained to orient participants to the rating scales. After interviewers independently practiced the interview protocol, trainees were tested by at least one RA. Students practiced, were retrained, and retested until they were fluent, accurate, appropriate, and comfortable. Training also emphasized standardization, confidentiality, and other procedures to reduce bias. Based on participants’ responses to specific questions, interviewers were also taught rules for intervention for sexual assault, suicidality, and life-threatening partner violence.

Interviewers read all questions aloud and recorded participants’ responses verbatim. Most items used Likert-type rating scales, with some yes–no questions, and some open-ended items. Participants were referred to a notebook containing response scales or other information for answering scaled questions. In addition, participants were given a calendar to facilitate recall of dates for specific events. Calendars had icons for holidays and participants circled dates representing important events in their lives (e.g., births, deaths, anniversaries) to improve recall (Kessler & Wethington, 1991). Interviews were then checked for completeness and accuracy when they were turned in to the lab. More detail on the procedures is available; see Honeycutt et al. (2001), Kallstrom-Fuqua, Weston, and Marshall (2004), and Marshall (1999).

Measures

Marshall’s (1992) Severity of Violence Against Women Scale (SVAWS) consists of 46 items to assess the frequency and severity of threats of physical violence, physically violent acts, and sexual aggression perpetrated against each participant. Participants were asked how often they had experienced each behavior since the last interview, approximately 1 year prior. Subscales within the measure vary in severity and differentiate threats of violence (symbolic violence; threats of mild, moderate, and serious acts) and acts of violence (minor, mild, moderate, and serious). We did not use the six sexual aggression items for this study. Marshall (1992) asked community women to rate the severity of each of the 46 items in terms of severity if a man did the act to a woman. The resulting scale has items organized in order of increasing perceptions of severity from threats to acts of physical violence. For the current study, we separated participants into four groups. Women reporting no threats of physical violence or acts of physical violence were classified as no violence (n = 159). Some women reported at least one threat of physical violence (e.g., partner threatened to hurt you, shook their fist at you, destroyed something belonging to you) but no physical violence and were classified as threats only (n = 68). The remaining women had experienced at least one act of physical violence (e.g., partner slapped, pushed, twisted your arm) but no severe/ serious physical violence (n = 78) or at least one act of severe/serious physical violence (e.g., partner choked, punched, or used a weapon, n = 55). Those who experienced no threats of physical violence or acts of physical violence were excluded from analyses, for the final sample of 201 women described above.

Social reactions to women’s disclosure of IPV were assessed using a modified version of the Social Reactions Questionnaire (SRQ; Ullman, 2000). The SRQ is a 48-item measure, originally developed to measure social reactions to disclosure of sexual assault victimization. Like others who have adapted Ullman’s measure (e.g., K. M. Edwards et al., 2015), we modified items when necessary to reflect IPV as opposed to sexual assault; for instance, items referencing a “perpetrator” were changed to “partner” or “him.” While the majority of items were adapted from Ullman’s original measure, an additional 12 items were adapted from previous research on social support behaviors (Jung, 1989). All additional items were created by our research team and were based on open-ended descriptions of social reactions from previous waves of data collection. Our modifications resulted in participants being asked, “When you have talked about the threatening and physical fights, how many of the people you’ve talked to did these things?” Response options in the scale notebook were presented on a single page and ranged from 1 (none) to 7 (all), with the midpoint of 4 described as about half. At the top of the page, participants were provided with a reminder that they are being asked questions in reference to “people you talk to about fights.” It is important to note that during this portion of the interview, the list of 46 items from the SVAWS was placed on the table so that participants would be able to recall IPV experiences that they may have disclosed.

An exploratory factor analysis of the modified SRQ resulted in two subscales: positive social reactions (34 items) and negative social reactions (50 items). We removed items that either did not load greater than .40 on any factor or had similar loadings (i.e., cross-loaded) on both factors. Unlike Ullman’s original measure, which consisted of seven subscales (emotional support/belief, treat differently, distraction, take control, tangible aid/informational support, victim blame, and egocentric), our results yielded a two-factor structure (positive and negative reactions). However, our factor structure is consistent with much of the research on social reactions adapted for IPV (see K. M. Edwards et al., 2015; Sylaska & Edwards, 2014). Means reflect participants’ perceptions of the proportion of people who reacted positively and negatively. Women’s reports of positive and negative social reactions were correlated, r(201) = .34, p < .001. (See Table 1 for full measure and factor loadings.)

Table 1.

Factor Loadings for Adapted Social Reactions Questionnaire.

| Items | Positive | Negative |

|---|---|---|

| Showed understanding of what happened and of your feelings | .819 | −.085 |

| Listened to your feelings | .814 | −.046 |

| Really accepted your description of it | .809 | −.015 |

| Saw your side of things and didn’t judge you | .808 | −.002 |

| Listened to what you saida | .805 | −.056 |

| Let you know they were on your sidea | .799 | −.038 |

| Showed they understood | .787 | −.055 |

| Listened to you talk about your feelingsb | .775 | −.031 |

| [Thought or said] they cared about youb | .768 | .000 |

| Comforted you by saying it would be all right or by holding you | .765 | .058 |

| [Thought or said] that you’re a good person | .738 | .004 |

| Comforted you with a hug or a patb | .736 | .112 |

| Helped you figure out what to doa | .733 | .115 |

| Held you and said they loved or cared about you | .717 | .136 |

| Did something to help you get your mind off of thingsb | .709 | .141 |

| Gave advice that helpeda | .705 | .085 |

| Reassured you and was confident you could handle itb | .698 | .088 |

| Tried to protect youa | .697 | .187 |

| Helped you see things more clearly | .694 | .144 |

| [Thought or said] it wasn’t your fault | .686 | .005 |

| Joked and kidded to try to cheer you upb | .669 | .152 |

| [Thought or said] go on with your life | .621 | .138 |

| Thought or said you didn’t do anything wrong | .619 | .017 |

| Thought or said you weren’t to blame | .610 | −.030 |

| [Thought or said] something like you deserve better treatmenta | .576 | .198 |

| Gave you information and talked about different things you could do | .572 | .196 |

| Told you how they’d dealt with a similar situationa | .564 | .208 |

| Were disappointed in himb | .534 | .233 |

| Offered a place to staya | .524 | .143 |

| Shared a personal experience that was similar to yoursb | .523 | .259 |

| Helped you get information to handle it | .513 | .212 |

| [Thought or said] they knew how you felt but really didn’t | .511 | .230 |

| Saw it as his faulta | .505 | .152 |

| Helped you understand your partnera | .498 | .200 |

| Avoided talking to you or spending time with you | .071 | .765 |

| Pulled away from you | .018 | .755 |

| Treated you differently than they had before and it made you uncomfortable | .084 | .745 |

| Focused on their own needs and neglected or ignored yours | .006 | .744 |

| Made you feel like you didn’t know how to take care of yourself | .013 | .740 |

| Criticized youa | .059 | .738 |

| Didn’t want to hear about ita | .042 | .734 |

| Didn’t really carea | .043 | .729 |

| Were disappointed in youa | .079 | .726 |

| Misunderstood, missed the pointa | .071 | .708 |

| Treated you like a child | .042 | .704 |

| Didn’t listen very wella | .085 | .701 |

| Were too busy to listen to your problemsb | .042 | .700 |

| Acted like it was less important or serious than it was to you | .090 | .700 |

| Tried to take control of what you did about it | .129 | .697 |

| Did not believe youa | .064 | .696 |

| Acted like something was wrong with you or you were somehow different now | .063 | .691 |

| Told others about it without your permission | .056 | .690 |

| Wanted you to stop talking about it | .055 | .671 |

| Were disappointed in your behaviora | .127 | .671 |

| Saw it as your fault | .015 | .668 |

| Told you it was not all that seriousb | .133 | .665 |

| Talked to your partner without your permissiona | .124 | .661 |

| [Thought or said] something like I told you soa | .125 | .659 |

| Did not understanda | .081 | .659 |

| Thought you should keep it a secret | .061 | .642 |

| Made it seem like no big deala | .121 | .639 |

| Told someone else about it | .175 | .632 |

| [Thought or said] you were to blame or shameful because of this | .035 | .612 |

| [Thought or said] you were careless or not careful enough | .190 | .606 |

| Gave advice that didn’t helpa | .138 | .597 |

| [Thought or said] you could have done more to keep it from happening | .231 | .583 |

| Took your partner’s sidea | .069 | .582 |

| Told you he didn’t mean ita | .213 | .561 |

| Wanted you to stop thinking about it | .252 | .559 |

| [Thought or said] you needed to change your waysb | .121 | .555 |

| Didn’t want to get involveda | .187 | .552 |

| [Thought or said] something like you deserve ita | .015 | .549 |

| Were so upset that they needed your comfort | .280 | .535 |

| Were so angry at your partner that you had to calm them down | .299 | .529 |

| Brought up past problems you’ve had with another mana | .160 | .525 |

| Thought or said you were mostly to blameb | −.010 | .522 |

| Told you what you did wronga | .266 | .508 |

| Told you to try to forget it happeneda | .235 | .507 |

| Wanted revenge or to get even with your partner | .215 | .507 |

| Made decisions or did things for you | .271 | .501 |

| [Thought or said] you could have avoided it if you’d done somethinga | .184 | .487 |

| [Thought or said] you should just take ita | .092 | .472 |

| [Thought or said] something like it’s ok for your partner to do ita | .000 | .468 |

| [Thought or said] they lost respect for youa | .010 | .403 |

Added items based on women’s responses at previous waves of data collection.

Items from Jung (1989).

To gain a better understanding of participants’ experiences with disclosing IPV, we also asked participants several open-ended questions. We first asked about the number of people and frequency of disclosures: “About how many different people have you ever talked to about fights being threatening or physical?” and “About how many times have you ever talked to someone about fights being threatening or physical?” We also asked participants about the first and most recent person they disclosed to (“Who was the first person you ever told about your fights?” and “Who was the most recent person you talked to about it?”).

Results

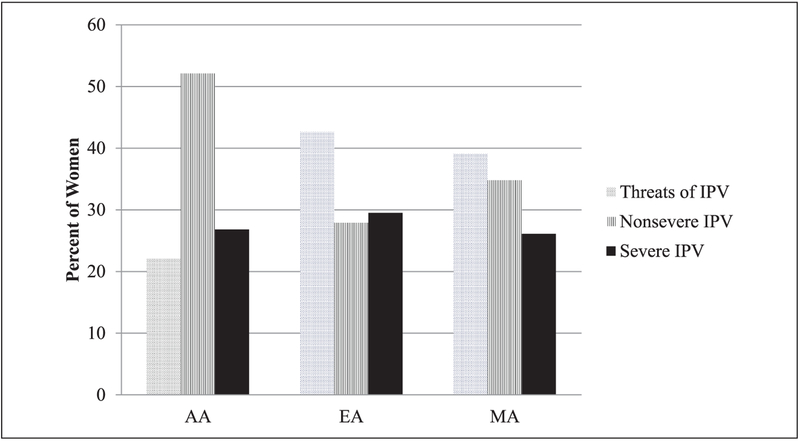

We first conducted a chi-square to determine if differences in IPV severity existed by women’s ethnicity. A significant difference occurred, χ2(4, N = 201) = 10.92, p = .028, with proportionately fewer AA women reporting only threats of IPV and more reporting nonsevere IPV; see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Percent of women in each IPV severity group by ethnicity.

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence; AA = African American; EA = Euro-American; MA = Mexican American.

Hypothesized differences in social reactions (positive, negative) were tested with a 3 (race/ethnicity) × 3 (IPV severity) mixed factorial MANOVA. A multivariate interaction emerged, Wilks’ λ(8, 382) = 2.037, p = .041, partial η2 = .04. Significant multivariate main effects occurred for ethnicity, Wilks’ λ(4, 382) 5.490, p < .001, partial η2 = .05, and for IPV severity, Wilks’ λ(4, 382) = 2.484, p = .043, partial η2 = .03.

Given the significance of the omnibus test, univariate-level analyses were examined. A significant main effect of IPV severity on positive social reactions, F(2, 192) = 3.40, p = .035, partial η2 = .03, was modified by a significant univariate interaction between race and severity for positive social reactions, F(4, 192) = 3.63, p = .007, partial η2 = .07. MA women perceived more than half of others’ social reactions were positive regardless of severity, while AA and EA women reported a smaller proportion of positive social reactions for threats and nonsevere physical violence than for severe physical violence; see Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of Means With Standard Deviations for Positive Social Reactions by Race/Ethnicity and IPV Severity.

| Threats only |

Nonsevere violence |

Severe violence |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) |

| AA | 15 | 3.17 (1.40) | 37 | 3.82 (1.69) | 19 | 5.03 (0.98) |

| EA | 26 | 3.73 (1.64) | 17 | 4.02 (1.71) | 18 | 4.30 (0.62) |

| MA | 27 | 4.95 (1.14) | 24 | 4.11 (1.35) | 18 | 4.39 (1.90) |

Note. Responses to the Social Reactions Questionnaire were on a scale from 1 (none) to 7 (all) with a midpoint of 4 (about half). IPV = intimate partner violence; AA = African American; EA = Euro-American; MA = Mexican American.

Although the univariate interaction for negative social reactions was not significant, a univariate main effect of race/ethnicity occurred for negative social reactions, F(2, 192) = 9.653, p < .001, partial η2 = .09. A post hoc Tukey’s analysis indicated that AA (M = 2.24, SD = 1.13) and MA women (M = 2.37, SD = 1.19) perceived a significantly greater proportion of reactions as negative compared with EA women (M = 1.60, SD = .617; p = .001, p < .001). Differences by IPV severity approached significance, F(2, 192) = 2.798, p = .064, partial η2 = .03; the proportion of negative social reactions were higher for women in the severe and nonsevere IPV groups than in the threats group. However, for all participants, negative social reactions were perceived less than half the time (M = 2.09 on a scale with 4 described as about half).

To address the secondary study aim, a 3 (race/ethnicity) ×3 (IPV severity) ANOVA tested for differences in the number of people women disclosed to. A significant interaction between race and severity occurred, F(4, 180) = 3.35, p = .011, partial η2 = .07; see Table 3. For MA women, little variability existed in the number of people disclosed to by IPV severity (range = 2.26-2.44). EA women disclosed to fewer people when experiencing nonsevere violence, followed by threats only, but to the most people when violence was severe. AA women disclosed to the fewest people when experiencing threats only, followed by severe violence and nonsevere violence.

Table 3.

Summary of Means With Standard Deviations for Number of People Women Disclosed to by Race/Ethnicity and IPV Severity.

| Threats only |

Nonsevere violence |

Severe violence |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) |

| AA | 12 | 1.41 (1.37) | 35 | 3.11 (3.24) | 18 | 3.00 (2.92) |

| EA | 24 | 2.45 (2.90) | 17 | 1.82 (2.42) | 18 | 5.39 (3.63) |

| MA | 26 | 2.44 (2.08) | 23 | 2.26 (2.39) | 18 | 2.44 (2.54) |

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence; AA = African American; EA = Euro-American; MA = Mexican American.

A 3 (race/ethnicity) × 3 (IPV severity) ANOVA tested for differences in the number of times women discussed fights with another person. A main effect of severity emerged, F(2, 182) = 4.179, p = .017, partial η2 = .04. Tukey’s post hoc comparisons indicated that women who experienced threats only (M = 2.92, SD = 3.94) disclosed significantly less often than those who experienced severe violence (M = 5.06, SD = 4.72; p = .024). However, women who reported nonsevere violence (M = 3.38, SD = 4.47) did not differ significantly from women who experienced threats only or severe violence. A main effect of ethnicity also emerged, F(2, 182) = 3.307, p = .039, partial η2 = .04. Tukey’s post hoc comparisons indicated that EA women (M = 4.76, SD = 5.25) differed from MA women (M = 2.94, SD = 3.49; p = .051). However, AA women (M = 4.39, SD = 4.16) did not significantly differ from EA or MA women.

To put our results into context, we asked women open-ended questions about who they disclosed to and coded their responses. The majority of women reported disclosing to family or friends. Specifically, when asked who women disclosed to the first time they ever discussed violence in their relationship, 52% of women reported disclosing to family members, 32% reported disclosing to friends, and 5% reported disclosing to formal sources of support (e.g., pastors, counselors, social workers). The remaining 11% of responses were not codable (e.g., myself). When asked who they disclosed to most recently, 60% of women reported disclosing to a friend, 15% reported disclosing to family members, 9% reported disclosing to formal sources of support. The remaining 16% of responses were not codable. Across all levels of severity and ethnicity, women were more likely to report disclosing to their mothers, sisters, or friends.

Discussion

We expected a main effect of severity of physical violence such that women who report greater violence severity would also report perceiving a greater proportion of social reactions as negative and a smaller proportion of social reactions as positive. We found that women who experience severe physical IPV perceive more positive reactions than women experiencing threats or nonsevere physical IPV. We also found that women who experience severe physical IPV perceive more negative reactions than women experiencing threats or nonsevere physical IPV, but this effect was only approaching significance. Overall, means were higher for positive social reactions as compared with negative social reactions, indicating that participants perceived a greater proportion of network members were providing positive social reactions than negative social reactions. Furthermore, for all participants, negative social reactions were perceived less than half the time. Our finding that women perceive fewer than half of the social reactions to disclosure as negative is encouraging based on previous research that has found that women are more likely to disclose and seek support as violence becomes more severe (Ansara & Hindin, 2010; Bachman & Coker, 1995; Barrett & Pierre, 2011; Flicker et al., 2011). Therefore, it is critically important that women disclosing about IPV are met with positive social reactions. We also found a main effect of severity of physical violence for the number of times women discussed fights; women reporting severe IPV discussed fights more often than women reporting threats or nonsevere IPV.

Our findings are consistent with research that indicates the majority of women do perceive a mix of both positive and negative social reactions (Trotter & Allen, 2009). Goodkind and colleagues (2003) also found that women report receiving fewer negative social reactions compared with positive reactions. We expected that more severe forms of violence may be associated with more anticipated and internalized stigma, thus one’s perception of negative social reactions is likely to increase as a function of physical violence severity. The trends in our data indicate that overall women perceive more positive reactions and therefore possibly less stigma associated with IPV disclosure. More social support and less stigmatization may create an approachable environment for those involved in violent relationships to seek help if desired. Future research should examine the role of stigma in social reactions to disclosure as it relates to further social support seeking.

We also wanted to know if there was a main effect for women’s ethnicity; specifically, we wanted to examine if perceptions of positive and negative social reactions differ based on women’s ethnicity. For negative social reactions, across all levels of severity, we found that MA and AA women perceived a greater proportion of social reactions as negative compared with EA women. We also found differences by ethnicity for the number of times women discussed fights with others. EA women discussed fights with others most often. If women are met with positive or even not negative (ambiguous) social reactions, they may be inclined to discuss violence more often. This would allow for more variance in their perceptions of social reactions compared with women who discuss their experiences with violence less frequently.

We wanted to know if physical violence severity and women’s ethnicity would interact to effect perceptions of social reactions to IPV disclosure. We expected that there would be an interaction, but again, did not hypothesize a direction. An interaction emerged for positive social reactions, but not for negative social reactions. However, the trends for both positive and negative social reactions are similar. Based on our cell sizes, we have limited power for this analysis, and therefore our interpretations of these findings are tentative. As a general trend, for AA and EA women, the proportion of positive social reactions (and negative social reactions) was greater for women who experienced severe physical IPV. In other words, AA and EA women reporting threats only reported a smaller proportion of support providers giving positive (and negative) reactions than women experiencing nonsevere IPV and women experiencing severe IPV. Furthermore, both AA and EA women did not perceive positive social reactions from even half of potential support providers for threats. For nonsevere violence, AA women perceived close to half of the people they disclosed to as reacting positively, while EA women perceived just over half of the people they disclosed to as reacting positively. However, EA and AA women perceived their greatest respective proportions of positive social reactions, at least half or more, for severe violence. Simply stated, when AA and EA women disclose IPV to others, they perceive a greater proportion of those people react (both positively and negatively) as severity increases.

Unlike the linear pattern found in both AA and EA women, MA women experiencing threats only reported the highest proportion of positive reactions (and negative reactions), followed by severe violence and nonsevere violence. It is possible that MA women’s social networks do not respond the same way to nonsevere physical violence as compared with the social networks of AA and EA women, or that MA women just do not perceive their family and friends’ reactions occurring as often for nonsevere violence. This is supported by our findings on MA women’s self-reported experiences with IPV disclosure. Across all levels of severity, MA women showed little variance in the number of people they disclosed to, and the smallest average range for how often they discussed fights. In addition, MA women perceived at least half of the people they disclosed to reacted positively across all levels of severity. Again, our interpretations of these interactions are tentative, given our sample size. Future research on racial/ethnic differences with larger samples should be examined to provide support and better understanding for potential ethnic/racial differences in IPV disclosure.

The sample for this study was small; however, results presented here are in line with those from other studies conducted with data from Project HOW. For example, in their examination of gender asymmetry of IPV using Wave 1 data, Weston, Temple, and Marshall (2005) found that AA women and partners perpetrated threats of mild and severe IPV as well as mild physical IPV more often than EA or MA women. Temple, Weston, Rodriguez, and Marshall (2007) also examined Wave 1 data when testing for differences in effects of partner and nonpartner sexual assault and found that partners of AA women were more likely to have sexually assaulted them than partners of EA or MA women. Both of these Wave 1 studies are in line with our Wave 6 results, indicating AA women were more likely to report their partners perpetrated threats and physical IPV than threats alone. On the contrary, Marshall, Weston, and Honeycutt (2000) did not find that ethnicity moderated associations between partners’ IPV and positive behaviors with women’s perceptions of relationship quality. With regard to social support, Kallstrom-Fuqua et al. (2004) tested for ethnic differences in network orientation at Wave 2 in a subsample of 183 women who had experienced sexual assault prior to age 18. They found that AA women were significantly less trusting than EA or MA women, which would suggest that AA women might be less likely to seek support, but that was not the case in this study.

Although research on race/ethnicity, IPV, and social support is often inconsistent and limited, in general the literature suggests differences in support seeking would exist. We found that patterns of perceptions of social reactions differed across race/ethnicity. Future research should examine whether differences exist based on cultural differences in perceptions of IPV or IPV-related stigma. Understanding the role of stigma in social reactions to IPV disclosure will help to better inform and develop intervention programming for friends and family of women in violent relationships. These interventions may need to be tailored to specific groups by race or ethnicity. However, if these differences are a by-product of differences in how ethnic groups stigmatize IPV, then instead, it may be more important to reduce IPV disclosure stigma, and teach friends and family ways to provide positive social reactions and reduce stigma without minimizing the negative consequences of relationship violence.

The current findings should be interpreted in the context of some important limitations. First, we asked participants to report about social reactions to informal disclosure. Many women reported disclosing to both family and friends. Therefore, we do not know whether their reports of positive and negative social reactions reflect those of friends, family, or both. Hispanic individuals may rely more on family as a source of support as opposed to friends (Ingram, 2007; Montalvo-Liendo, Wardell, Engebretson, & Reininger, 2009). Because of this, there may be differences in the content of disclosure and the social reactions one perceives. Also, differences in ethnicity may be attributed to cultural norms, beliefs, and values; for instance, some cultures may be more accepting of certain violent acts while also stigmatizing others. The culture and family dynamic of each person has the potential to shape how individuals experience, perceive, and label violence in their romantic relationships and in turn how they choose to disclose or seek help. Overall, little is known about disclosure among MA women (Montalvo-Liendo et al., 2009). Future research should examine to whom women disclose (friends vs. family) and cultural factors, such as acculturation and norms among MA women’s IPV disclosure, to learn more about social reactions and the perception of IPV at varying levels of severity.

Second, we found that women in our sample experience both positive and negative social reactions to IPV disclosure. We do not know, however, what leads to a reaction to be perceived as positive versus negative. To gain a richer picture of what women experience when they disclose, future research should ask women more detailed questions about the specific interactions that resulted in perceptions of reactions as positive or negative. Likewise, we do not know what prompted disclosure. For instance, a woman may disclose because she chooses to do so or because the informal support provider prompted disclosure or witnessed violence. This is likely to affect the social reactions of women’s informal support providers and how women perceived those social reactions. In addition, information on what was discussed during disclosure was not provided. IPV is often mutual (Straus, 2008); therefore, women’s IPV disclosure may have included information about both perpetration and victimization. The content of those disclosure conversations is likely to have an impact on the social reactions of others. Future research can address these limitations by asking participants specifically who reacted positively or negatively, what prompted their disclosure, and the content of the disclosure conversation. It is likely that these factors play an important role in how informal support providers react to disclosure and how those social reactions are perceived. This information could provide us with a deeper understanding of women’s experiences and perceptions of social reactions to IPV disclosure.

Third, the current study is limited in that we measured social reactions to IPV disclosure using an adapted measure. Ullman’s (2000) social reactions measure was originally developed to examine the social reactions women received from sexual assault disclosure. However, as there is currently no measure for social reactions to IPV disclosure, many researchers have adapted Ullman’s measure to examine social reactions to IPV disclosure and have found it to be both valid and reliable (K. M. Edwards et al., 2015; Sullivan et al., 2010; Sylaska & Edwards, 2014).

Finally, it is important to acknowledge the lag in time since data were collected. Data used in this study were collected in 2003. However, our findings address a gap in the current literature. Researchers should continue to study social reactions while acknowledging the new methods of disclosure that are available to women. When these data were collected, social media had not taken off yet. With new avenues for disclosure, such as social media and anonymous forums, women likely have more opportunities to disclose experiences of IPV without a face-to-face interaction. This could result in different social reactions or different perceptions of social reactions considering the lack of body language, tone, and possible anonymity.

The current study has implications for programs to inform potential informal support providers. It is possible that disclosure recipients do not know how to respond to disclosure. Informal support providers may be placed in an awkward situation where they do not want to condone violence and likewise do not want to alienate their friend or family member. By learning more about social reactions to IPV disclosure, programs can help support providers by providing information on what is a helpful or hurtful social reaction to the discloser. These programs can help informal support providers strike a balance between what they are comfortable with and the type of support the discloser needs from them.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by grant number R49/CCR610508 from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), and grant number 3691 from the Hogg Foundation for Mental Health, awarded to the third author. Additional funding was provided by grant number 2001WTBX0504 from NIJ awarded to both the second and third authors. The first author was partially funded by the University of Texas at San Antonio Research Initiative for Scientific Enhancement (UTSA RISE) R25 GM060655. The results do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Biography

Monica C. Yndo, MS, is a doctoral candidate in psychology at the University of Texas at San Antonio. Her research interests broadly include the social processes and contextual factors that differentiate experiences and outcomes of intimate partner violence. She is also interested in how these factors influence perceptions and behaviors that are related to violence labeling and decision making. Her recent work focuses on the role of maladaptive communication in teen and college students’ dating violence.

Rebecca Weston, PhD, is an associate professor of psychology at the University of Texas at San Antonio and director of the department’s new doctoral program. Her research interests include changes in intimate partner violence perpetration and victimization over time, effects of victimization on women’s physical and mental health, motives for IPV perpetration, and mediators of long-term effects of IPV. She has received funding from the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Department of Defense to examine intimate partner violence.

Linda L. Marshall, PhD, is a professor of psychology at the University of North Texas. Her degree in social psychology is from Boston University. She has studied psychological abuse and violence for more than 30 years and has been funded by the Hogg Foundation, National Institutes of Health (NIH), CDC, and NIJ.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ahrens CE, Rios-Mandel LC, Isas L, & del Carmen Lopez M (2010). Talking about interpersonal violence: Cultural influences on Latinas’ identification and disclosure of sexual assault and intimate partner violence. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 2, 284–295. [Google Scholar]

- Amar AF, & Gennaro S (2005). Dating violence in college women: Associated physical injury, healthcare usage, and mental health symptoms. Nursing Research, 54, 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansara DL, & Hindin MJ (2010). Formal and informal help-seeking associated with women’s and men’s experiences of intimate partner violence in Canada. Social Science & Medicine, 70, 1011–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avanci J, Assis S, & Oliveira R (2013). A cross-sectional analysis of women’s mental health problems: Examining the association with different types of violence among a sample of Brazilian mothers. BMC Women’s Health, 13(1), Article 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman R, & Coker AL (1995). Police involvement in domestic violence: The interactive effects of victim injury, offender’s history of violence, and race. Violence and Victims, 10(2), 91–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett BJ, & Pierre MS (2011). Variations in women’s help seeking in response to intimate partner violence: Findings from a Canadian population-based study. Violence Against Women, 17, 47–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belknap J, Melton HC, Denney JT, Fleury-Steiner RE, & Sullivan CM (2009). The levels and roles of social and institutional support reported by survivors of intimate partner abuse. Feminist Criminology, 4, 377–402. [Google Scholar]

- Belle D (1990). Poverty and women’s mental health. American Psychologist, 45, 385–389. [Google Scholar]

- Bennice JA, Resick PA, Mechanic M, & Astin M (2003). The relative effects of intimate partner physical and sexual violence on post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology. Violence and Victims, 18, 87–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun HA, Beydoun MA, Kaufman JS, Lo B, & Zonderman AB (2012). Intimate partner violence against adult women and its association with major depressive disorder, depressive symptoms and postpartum depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 75, 959–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiding MJ (2015). Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence victimization-National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, United States, 2011. American Journal of Public Health, 105(4), e11–e12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T, Ullman SE, Tsong Y, & Gobin R (2011). Surviving the storm: The role of social support and religious coping in sexual assault recovery of African American women. Violence Against Women, 17, 1601–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, & Kim HK (2012). A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse, 3, 231–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt HM, & Smith PH (2002). Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 23, 260–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Watkins KW, Smith PH, & Brandt HM (2003). Social support reduces the impact of partner violence on health: Application of structural equation models. Preventive Medicine, 37, 259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Caetano R, & Schafer J (2002). Socioeconomic predictors of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Journal of Family Violence, 17, 377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon G, Hussain R, Loxton D, & Rahman S (2013). Mental and physical health and intimate partner violence against women: A review of the literature. International Journal of Family Medicine, 2013, Article 313909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham K, & Senn CY (2000). Minimizing negative experiences women’s disclosure of partner abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15, 251–261. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KM, Dardis CM, & Gidycz CA (2012). Women’s disclosure of dating violence: A mixed methodological study. Feminism & Psychology, 22, 507–517. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KM, Dardis CM, Sylaska KM, & Gidycz CA (2015). Informal social reactions to college women’s disclosure of intimate partner violence associations with psychological and relational variables. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30, 25–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards VJ, Black MC, Dhingra S, McKnight-Eily L, & Perry GS (2009). Physical and sexual intimate partner violence and reported serious psychological distress in the 2007 BRFSS. International Journal of Public Health, 54, 37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escribà-Agüir V, Ruiz-Pérez I, Montero-Piñar MI, Vives-Cases C, Plazaola-Castaño J, Martín-Baena D, & G6 for the Study of Gender Violence in Spain. (2010). Partner violence and psychological well-being: Buffer or indirect effect of social support. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72, 383–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MA, & Feder GS (2016). Help-seeking amongst women survivors of domestic violence: A qualitative study of pathways towards formal and informal support. Health Expectations, 19, 62–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanslow JL, & Robinson EM (2010). Help-seeking behaviors and reasons for help seeking reported by a representative sample of women victims of intimate partner violence in New Zealand. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25, 929–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finfgeld-Connett D (2005). Clarification of social support. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 37, 4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicker SM, Cerulli C, Zhao X, Tang W, Watts A, Xia Y, & Talbot NL (2011). Concomitant forms of abuse and help-seeking behavior among White, African American, and Latina women who experience intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women, 17, 1067–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredland N, Symes L, Gilroy H, Paulson R, Nava A, McFarlane J, & Pennings J (2015). Connecting partner violence to poor functioning for mothers and children: Modeling inter-generational outcomes. Journal of Family Violence, 30, 555–566. [Google Scholar]

- García-Moreno C (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Golding JM (1999). Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Violence, 14, 99–132. [Google Scholar]

- Golin CE, Amola O, Dardick A, Montgomery B, Bishop L, Parker S, & Owens LE (2017). Poverty, personal experiences of violence, and mental health: Understanding their complex intersections among low-income women In O’Leary A & Frew PM (Eds.), Poverty in the United States (pp. 63–91). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind JR, Gillum TL, Bybee DI, & Sullivan CM (2003). The impact of family and friends’ reactions on the well-being of women with abusive partners. Violence Against Women, 9, 347–373. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA, Smyth KF, Borges AM, & Singer R (2009). When crises collide: How intimate partner violence and poverty intersect to shape women’s mental health and coping. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 10, 306–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honeycutt TC, Marshall LL, & Weston R (2001). Toward ethnically specific models of employment, public assistance, and victimization. Violence Against Women, 7, 126–140. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram EM (2007). A comparison of help seeking between Latino and non-Latino victims of intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women, 13, 159–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, & Leone JM (2005). The differential effects of intimate terrorism and situational couple violence: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Journal of Family Issues, 26, 322–349. [Google Scholar]

- Jung J (1989). Social support rejection and reappraisal by providers and recipients. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 19, 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Kallstrom-Fuqua AC, Weston R, & Marshall LL (2004). Childhood and adolescent sexual abuse of community women: Mediated effects on psychological distress and social relationships. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 980–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaukinen C (2004). The help-seeking strategies of female violent-crime victims: The direct and conditional effects of race and the victim–offender relationship. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19, 967–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, & Wethington E (1991). The reliability of life event reports in a community survey. Psychological Medicine, 21, 723–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone JM, Lape ME, & Xu Y (2014). Women’s decisions to not seek formal help for partner violence: A comparison of intimate terrorism and situational couple violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29, 1850–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levendosky AA, Bogat GA, Theran SA, Trotter JS, Von Eye A, & Davidson WS II. (2004). The social networks of women experiencing domestic violence. American Journal of Community Psychology, 34, 95–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang B, Goodman L, Tummala-Narra P, & Weintraub S (2005). A theoretical framework for understanding help-seeking processes among survivors of intimate partner violence. American Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 71–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall LL (1992). Development of the Severity of Violence Against Women Scales. Journal of Family Violence, 7, 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall LL (1999). Effects of men’s subtle and overt psychological abuse on low-income women. Violence and Victims, 14, 69–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall LL, Weston R, & Honeycutt TC (2000). Does men’s positivity moderate or mediate the effects of their abuse on women’s relationship quality? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 17, 660–675. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Torteya C, Bogat GA, von Eye A, Levendosky AA, Davidson II, & William S (2009). Women’s appraisals of intimate partner violence stressfulness and their relationship to depressive and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Violence and Victims, 24, 707–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mburia-Mwalili A, Clements-Nolle K, Lee W, Shadley M, & Yang W (2010). Intimate partner violence and depression in a population-based sample of women: Can social support help? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25, 2258–2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalvo-Liendo N (2009). Cross-cultural factors in disclosure of intimate partner violence: An integrated review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65, 20–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalvo-Liendo N, Wardell DW, Engebretson J, & Reininger BM (2009). Factors influencing disclosure of abuse by women of Mexican descent. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 41, 359–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muelleman RL, Lenaghan PA, & Pakieser RA (1996). Battered women: Injury locations and types. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 28, 486–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CE, Crowe A, & Overstreet NM (2018). Sources and components of stigma experienced by survivors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33, 515–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet NM, & Quinn DM (2013). The intimate partner violence stigmatization model and barriers to help seeking. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35, 109–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan DJ, & Nash KR (2007). Acute injury patterns of intimate partner violence victims. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 8, 281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA (2008). Dominance and symmetry in partner violence by male and female university students in 32 nations. Children and Youth Services Review, 30, 252–275. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TP, Schroeder JA, Dudley DN, & Dixon JM (2010). Do differing types of victimization and coping strategies influence the type of social reactions experienced by current victims of intimate partner violence? Violence Against Women, 16, 638–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylaska KM, & Edwards KM (2014). Disclosure of intimate partner violence to informal social support network members: A review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 15, 3–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple JR, Weston R, Rodriguez BF, & Marshall LL (2007). Differing effects of partner and nonpartner sexual assault on women’s mental health. Violence Against Women, 13, 285–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotter JL, & Allen NE (2009). The good, the bad, and the ugly: Domestic violence survivors’ experiences with their informal social networks. American Journal of Community Psychology, 43, 221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE (1999). Social support and recovery from sexual assault: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 4, 343–358. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE (2000). Psychometric characteristics of the social reactions questionnaire. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24, 257–271. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE (2010). Social reactions and their effects on survivors In Talking about sexual assault: Society’s response to survivors (pp. 59–82). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Vest JR, Catlin TK, Chen JJ, & Brownson RC (2002). Multistate analysis of factors associated with intimate partner violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 22, 156–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West CM, Kantor GK, & Jasinski JL (1998). Sociodemographic predictors and cultural barriers to help-seeking behavior by Latina and Anglo-American battered women. Violence and Victims, 13, 361–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston R, Temple JR, & Marshall LL (2005). Gender symmetry and asymmetry in violent relationships: Patterns of mutuality among racially diverse women. Sex Roles, 53, 553–571. [Google Scholar]

- Williams SL, & Mickelson KD (2008). A paradox of support seeking and rejection among the stigmatized. Personal Relationships, 15, 493–509. [Google Scholar]