Abstract

The oncogenic MUC1-C protein is overexpressed in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells and contributes to their epigenetic reprogramming and chemoresistance. Here we show that targeting MUC1-C genetically or pharmacologically with the GO-203 inhibitor, which blocks MUC1-C nuclear localization, induced DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) and potentiated cisplatin (CDDP)-induced DNA damage and death. MUC1-C regulated nuclear localization of the polycomb group proteins BMI1 and EZH2, which formed complexes with PARP1 during the DNA damage response (DDR). Targeting MUC1-C downregulated BMI1-induced H2A ubiquitylation, EZH2-driven H3K27 trimethylation, and activation of PARP1. As a result, treatment with GO-203 synergistically sensitized both mutant and wild-type BRCA1 TNBC cells to the PARP inhibitor olaparib. These findings uncover a role for MUC1-C in the regulation of PARP1 and identify a therapeutic strategy for enhancing the effectiveness of PARP inhibitors against TNBC.

Keywords: TNBC, MUC1-C, BMI1, EZH2, PARP1, olaparib

Introduction

MUC1-C is a transmembrane oncoprotein that is aberrantly overexpressed by diverse types of human carcinomas (1,2). MUC1-C interacts with receptor tyrosine kinases, such as HER2 and EGFR, at the cell membrane and promotes their activation and downstream signaling pathways (2–4). MUC1-C is also imported into the nucleus of cancer cells, where it induces changes in gene expression patterns by direct interactions with transcription factors and effectors of epigenetic regulation (3,4). MUC1-C-induced gene signatures in tumors have been associated with poor clinical outcomes and multiple hallmarks of the cancer cell, including the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), cancer stem cell (CSC) state, repression of tumor suppressor genes (TSGs), reprogramming of the epigenome and immune evasion (3,4). EMT and the CSC state contribute to the development of anti-cancer drug resistance (5,6). In this respect, MUC1-C promotes resistance to genotoxic anti-cancer agents (7–11). Studies have shown that MUC1-C blocks the apoptotic response of cancer cells to cisplatin (CDDP) and etoposide treatment (7–9). In addition, resistance to gemcitabine has been associated with MUC1-C-induced increases in anabolic glucose metabolism (11). These findings supported the notion that MUC1-C activates pleotropic cellular mechanisms that confer resistance to genotoxic anti-cancer agents.

An early event in the response to genotoxic stress is the recruitment and activation of PARP1 at sites of DNA lesions (12). PARP1 catalyzes the poly-ADP-ribosylation (PARylation) of itself and multiple target proteins in initiating the repair of single-strand and double-strand breaks (DSBs) (12). In the repair of DSBs by homologous recombination (HR), PARP1 functions in the recruitment of DNA damage response (DDR) proteins, such as phosphorylated histone H2AX (γH2AX) (12). PARP1 also recruits the breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein (BRCA1), which induces DSB resection and loading of RAD51 for strand exchange in HR (13,14). PARP1 ADP-ribosylates BRCA1, resulting in decreased affinity of BRCA1 for DNA binding and fine-tuning of its function in HR repair (15). The importance of PARP1 in the DDR led to the development of selective inhibitors, such as olaparib, rucaparib and niraparib, for the treatment of tumors with BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations or deletions (16). Trapping of PARP function by inhibitors with the resulting generation of replication-dependent DSBs contributes to the synthetic lethal relationship between PARP and BRCA (17). In addition, the synergy between PARP inhibition and treatment with genotoxic anti-cancer agents has provided the basis for evaluating such combinations in clinical trials (18,19). Notably, PARP1 also plays roles in (i) transcriptional regulation of activated genes, (ii) maintaining the stability of replication forks, and (iii) remodeling of chromatin structure (12,20). In this way, PARP1 inhibition in cancer cells can affect multiple pathways, including those associated with the acquisition of drug resistance.

The present studies uncover a previously unrecognized role for MUC1-C in the DDR. We show that targeting MUC1-C genetically or pharmacologically with the cell-penetrating GO-203 inhibitor (21) suppresses nuclear BMI1 and EZH2 levels, and thereby their chromatin remodeling activities, which are necessary for DSB-mediated transcriptional silencing and DNA repair. Additionally, targeting MUC1-C suppresses activation of PARP1 in the DDR and is synergistic with the PARP inhibitor olaparib in the treatment of TNBC cells with mutant and wild-type BRCA1.

Methods

Cell culture

Human BT-549 (wt BRCA1) TNBC cells were grown in RPMI1640 medium (Corning, Manassas, VA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin and 10 μg/ml insulin. SUM149 (mut BRCA1) and SUM159 (wt BRCA1) TNBC cells were cultured in Ham’s F-12 medium (Corning) supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, 5% FBS, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin and 5 μg/ml insulin and 1 μg/ml hydrocortisone. MDA-MB-468 (wt BRCA1) were grown in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 100 U/ml penicillin. BT-549 and SUM149 cells transduced to stably express a tet-CshRNA or a tet-MUC1shRNA were treated with doxycycline (DOX; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Cells were also treated with cisplatin (CDDP; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), etoposide (Sigma), olaparib (Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX, USA) and GO-203, which is a cell-penetrating peptide that blocks MUC1-C homodimerization, nuclear localization and oncogenic function (21).

Subcellular fractionation

Cells were washed with PBS and incubated in cell lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% NP40 and 10 mM KCl) for 10 minutes at 4oC. The total cell lysates were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 minutes at 4oC and the pellets were incubated in nuclear lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 1.6 mM MgCl2, 0.5% NP40, 420 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA and 25% glycerol) for 20 minutes at 4oC, and then sheared by passage through 20–26 gauge needles. After centrifugation at 130,000 rpm for 10 minutes, the supernatants were collected as nuclear lysates.

Immunoblot analysis

Lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-MUC1-C (HM-1630-P1ABX; Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-β-actin (A5441; Sigma), anti-lamin A/C (4777), anti-γH2AX (9718), anti-ATR (2790), anti-pCHK1 (2348), anti-CHK1 (2360), anti-pBRCA1 (9009), anti-BRCA1 (14823), anti-BMI1 (6964), anti-H2AUb1 (8240), anti-H2A (12349), anti-EZH2 (5246), anti-H3K27me3 (9733), anti-H3 (9715), anti-H3K56ac (4243), anti-PARP1 (9532) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-pATR (GTX128145; GeneTex, Irvine, CA, USA) and anti-FANCD2 (ac108928; Abcam, Cambridge, CB4, 0Fl, UK). Signal intensity was determined using ImageJ 1.51k software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Confocal microscopy

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 minutes. The samples were washed three times with PBS and then incubated with 0.3% Triton X-100 (Sigma) at room temperature for 15 minutes. Samples were next blocked with 3% BSA and incubated with primary antibodies at 4oC. The samples were then incubated with goat anti-Armenian hamster IgG H&L labeled with Alexa Fluor® 488 (Abcam) and goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L labeled with Alexa Fluor® 568 (Abcam) at room temperature for 60 minutes. DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for staining of nuclei. The cells were analyzed by confocal microscopy using an inverted Leica TCS SP5 scope (Leica, Mannheim, Germany). Images were captured at increments and converted to composites localized on the nucleus by Leica LAS AF software (22).

Colony formation assay

Cells were seeded at 3000 cells/well in 6-well plates and treated with 500 ng/ml DOX and/or 10 μM CDDP for 10 days. The cells were then stained with 0.5% crystal violet in 25% methanol. Colonies >25 cells were counted in triplicate wells.

Cell viability and combination index

Cells were seeded at a density of 1000–2000 cells per well in 96-well plates. After 24 hours, the cells were treated with different concentrations of GO-203, CDDP and olaparib alone and in combination. Cell viability was assessed by Alamar blue staining of triplicate wells. The IC50 value was determined by non-linear regression of the dose-response data using Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software). Drug interaction and dose-effect relationships were analyzed according to reported methods (23). The combination index (CI) was calculated to assess synergism (CI<1) or antagonism (CI>1).

Coimmunoprecipitation of nuclear proteins

Nuclear lysates isolated as described above. DNA was digested by incubation in 20 U/ml DNase for 30 minutes at 37oC. Nuclear proteins were incubated with primary antibodies at 4oC overnight and then precipitated with Dynabeads Protein G (10003D; Thermo Fisher) for 2 hours at 4oC. Beads were washed twice with washing buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% NP40 and 150 mM NaCl) and once with 10% TE buffer (BM-304A; Boston BioProducts, Ashland, MA, USA), and then resuspended in sample loading buffer.

Measurement of PARP1 activity

The PARP activity kit (4685–096-K; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was used to measure PARP activity according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Tumor model studies

Six-8 week old female nude mice (Taconic Farm, Hudson, NY, USA) were injected subcutaneously in the flank with 3×106 SUM149 cells in 50% matrigel solution. Mice were grouped when tumor size reached approximately 100 mm3 and were treated intraperitoneally (IP) with vehicle, 15 mpk GO-203 encapsulated in nanoparticles (GO-203/NPs) for sustained delivery (21) (once a week for three weeks), 15 mpk olaparib (5 days on, 2 days off for three weeks), and GO-203/NPs plus olaparib. Tumor measurements and body weights were recorded twice a week. Tumor volumes were calculated by the formula: (width)2 x length/2.

Animals

Animal studies were performed under animal protocols #03–029 approved by the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Animal Use and Care Committee.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times. Data are expressed as the mean±SD. The unpaired Student’s t-test was used to examine differences between means of two groups. A p-value of <0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference denoted by an asterisk.

Results

MUC1-C localizes to the nucleus in the response to DNA damage

MUC1-C consists of a 58 aa extracellular domain, a 22 aa transmembrane domain and a 72 aa cytoplasmic domain (Fig. 1A). The MUC1-C cytoplasmic domain is an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) that includes a CQC motif necessary for MUC1-C homodimerization and nuclear import (24–26). MUC1-C is constitutively expressed in the nucleus of diverse cancer cells (2,4,24,27); however, its nuclear localization has not been associated with DNA damage. We found that treatment of BT-549 TNBC cells with CDDP has little effect on total MUC1-C levels (Fig. 1B, left), but is associated with increases in nuclear MUC1-C protein (Fig. 1B, right). Similar results were obtained in the response of MDA-MB-468 (Supplemental Fig. S1A), SUM159 (Supplemental Fig. S1B) and BRCA1 mutant SUM149 (Fig. 1C) TNBC cells to CDDP treatment. As confirmation of these observations, confocal microscopy further showed CDDP-induced localization of MUC1-C to the nucleus in BT-549 and SUM149 cells (Figs. 1D and 1E). Similar effects were observed with the genotoxic agent, etoposide (Supplemental Figs. S1C and S1D), indicating that MUC1-C is imported to the nucleus in the response to DNA damage.

Figure 1. Nuclear localization of MUC1-C in the DDR.

A. Structure of the MUC1-C protein with the 58 aa extracellular domain (ED), 28 aa transmembrane domain (TM) and 72 aa cytoplasmic domain (CD). Highlighted is the aa sequence of the CD, which is an intrinsically protein (IDP). The CQC motif is necessary for MUC1-C homodimerization and nuclear localization, and is the target of the cell-penetrating peptide GO-203 (R9-CQCRRKN). B and C. BT-549 (B) and SUM149 (C) cells were left untreated or treated with 10 μM CDDP for 24 h. Total cell (left) and nuclear (right) lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against the indicated proteins. D and E. BT-549 (D) and SUM149 (E) cells were left untreated (Control) or treated with 10 FM CDDP for 24 h. The cells were stained with DAPI and analyzed for nuclear MUC1-C localization by confocal microscopy.

Targeting MUC1-C induces γH2AX and sensitizes to CDDP treatment

To determine if MUC1-C is functionally involved in the DDR, we generated BT-549 cells expressing a tetracycline-inducible control shRNA (tet-CshRNA) or a MUC1-C shRNA (tet-MUC1shRNA). Doxycycline (DOX) treatment of BT-549/tet-MUC1shRNA, but not BT-549/tet-CshRNA, cells was associated with downregulation of MUC1-C and, interestingly, increases in γH2AX (Fig. 2A; Supplemental Fig. S2A). Silencing MUC1-C in SUM149 cells also resulted in induction of γH2AX (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Fig. S2B), indicating that downregulation of MUC1-C induces DSBs. In concert with these observations, we found that silencing MUC1-C increases CDDP-induced γH2AX levels (Figs. 2C and 2D). Silencing MUC1-C also potentiated CDDP-induced loss of colony formation (Figs. 2E and 2F), consistent with a role for MUC1-C in DNA damage-induced cell death.

Figure 2. Silencing MUC1-C induces γH2AX.

A and B. BT-549 (A) and SUM149 (B) cells stably expressing a tet-MUC1shRNA were treated with 500 ng/ml DOX for 72 h. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies against the indicated proteins. C and D. BT-549/tet-MUC1shRNA (C) and SUM149/tet-MUC1shRNA (D) cells were treated with 500 ng/ml DOX for 72 h and then 10 μM CDDP for 24 h. Lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis. E and F. BT-549/tet-MUC1shRNA (E) and SUM149/tet-MUC1shRNA (F) cells were treated with 500 ng/ml DOX and/or 10 μM CDDP for 10 days. Colony formation was determined by crystal violet staining. The results are expressed as the mean±SD of three determinations. An asterisk denotes a p-value of <0.05.

To extend these studies, cells were treated with the GO-203 inhibitor, which targets the MUC1-C cytoplasmic domain at a CQC motif required for MUC1-C homodimerization and nuclear import (Fig. 1A) (2,24). Treatment of BT-549 and SUM149 cells with GO-203 had little effect on MUC1-C levels (Supplemental Figs. S3A and S3B), but attenuated CDDP-induced localization of MUC1-C to the nucleus (Figs. 3A and 3B). Notably and consistent with the effects of silencing MUC1-C, treatment with GO-203 alone and in combination with CDDP was associated with increases in γH2AX levels (Figs. 3C and 3D). These effects of GO-203 on MUC1-C localization and induction of γH2AX were confirmed by confocal microscopy (Figs. 3E and 3F). In concert with these observations, we found that GO-203 is synergistic with CDDP in inducing cell death (Figs. 3G and 3H; Supplemental Figs. S4A and S4B). These findings demonstrated that targeting MUC1-C genetically or pharmacologically increases γH2AX and potentiates CDDP-induced loss of TNBC cell survival.

Figure 3. Targeting MUC1-C with the GO-203 inhibitor attenuates nuclear localization of MUC1-C and induces γH2AX.

A-D. BT-549 (A,C) and SUM149 (B,D) cells were left untreated or treated with 1 μM GO-203 for 48 h and then without or with 10 μM CDDP for 24 h. Nuclear (A,B) and total (C,D) lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies against the indicated proteins. E and F. BT-549 (E) and SUM149 (F) cells were treated with 10 μM CDDP for 24 h, 1 μM GO-203 for 48 h, or GO-203 for 48 h and then CDDP for 24 h. The cells were stained with DAPI and analyzed for nuclear MUC1-C and γH2AX by confocal microscopy. G and H. BT-549 (G) and SUM149 (H) cells were left untreated or treated with 0.1, 0.3 or 1 μM GO-203 in the absence and presence of the indicated concentrations of CDDP. Cell viability was determined by Alamar blue staining. The results represent the CI values, which at <1.0 denote synergism.

To assess whether targeting MUC1-C alters DNA damage checkpoints, we investigated effects on activation of ATR and CHK1. Silencing MUC1-C in BT-549 (Supplemental Fig. S5A) and SUM149 (Supplemental Fig. S5B) cells was associated with increases in pATR and pCHK1 in the absence of changes in ATR and CHK1 levels. Similar responses were observed when BT-549 (Supplemental Fig. S5C) and SUM149 (Supplemental Fig. S5D) cells were treated with GO-203, indicating that MUC1-C downregulation or inhibition activates the ATR and CHK1 checkpoints. We also found that targeting MUC1-C increases BRCA1 phosphorylation and has little if any effect on FANCD2 levels (Supplemental Figs. S5A-S5D). These results provided support for a model in which MUC1-C induces DSBs by mechanisms other than affecting these DNA damage checkpoints or repair proteins.

MUC1-C regulates nuclear BMI1 in the DDR

Nuclear functions of MUC1-C have been linked to the repression of TSGs and reprogramming of the epigenome by regulating polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) function (3,4). Here, we found that MUC1-C forms a nuclear complex with BMI1 (Figs. 4A and 4B) and that silencing MUC1-C is associated with decreases in nuclear BMI1 (Figs. 4C and 4D). BMI1 regulates the DDR by ubiquitylation of H2A and thereby facilitating the repair of DSBs by HR and NHEJ (28). In this capacity, we found that downregulation of MUC1-C decreases nuclear H2AUb1 levels (Figs. 4C and 4D). Consistent with these results, we also found that targeting MUC1-C with the GO-203 inhibitor disrupts the interaction between MUC1-C and BMI1 (Figs. 4E and 4F). Moreover, inhibiting MUC1-C decreased nuclear BMI1 expression and in turn markedly reduced nuclear H2AUb1 levels (Figs. 4G and 4H), indicating that MUC1-C contributes to BMI1 function in the DDR.

Figure 4. Targeting MUC1-C downregulates nuclear BMI1 and H2AUb1 in the DDR.

A and B. Nuclear proteins from BT-549 (A) and SUM149 (B) cells were precipitated with anti-MUC1-C or a control IgG. Input and the precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against the indicated proteins. C and D. BT-549/tet-MUC1shRNA (C) and SUM149/tet-MUC1shRNA (D) cells were treated with 500 ng/ml DOX for 72 h and then 10 μM CDDP for 24 h. Nuclear lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies against the indicated proteins. E and F. BT-549 (E) and SUM149 (F) cells were left untreated or treated with 3 μM GO-203 for 48 h. Nuclear proteins were precipitated with anti-MUC1-C or a control IgG. Input and the precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against the indicated proteins. G and H. BT-549 (G) and SUM149 (H) cells were left untreated or treated with 3 μM GO-203 for 48 h. Nuclear lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against the indicated proteins.

MUC1-C interacts with EZH2 in the DDR

MUC1-C also plays a role in regulating EZH2 (29), which induces H3K27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) and has been linked to the DDR (30). In this respect, we found that MUC1-C forms nuclear complexes with EZH2 (Figs. 5A and 5B) and that silencing MUC1-C decreases nuclear EZH2 in association with suppression of H3K27me3 levels (Figs. 5C and 5D). Inhibiting MUC1-C with GO-203 also decreased (i) the interaction between nuclear MUC1-C and EZH2 (Figs. 5E and 5F), and (ii) nuclear EZH2 and H3K27me3 levels (Figs. 5G and 5H). In contrast, targeting MUC1-C had no apparent effect on H3K56ac levels (Supplemental Figs. S6A-S6D), which have been implicated in DNA repair (31). These findings demonstrate that, in addition to BMI1, MUC1-C regulates nuclear localization of EZH2 and its function in catalyzing the formation of H3K27me3, which is necessary for the repair of DSBs.

Figure 5. MUC1-C forms a nuclear complex with EZH2 and regulates H3K27 trimethylation.

A and B. Nuclear proteins from BT-549 (A) and SUM149 (B) cells were precipitated with anti-MUC1-C or a control IgG. Input and the precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against the indicated proteins. C and D. BT-549/tet-MUC1shRNA (C) and SUM149/tet-MUC1shRNA (D) cells were treated with 500 ng/ml DOX for 72 h and then 10 μM CDDP for 24 h. Nuclear lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies against the indicated proteins. E and F. BT-549 (E) and SUM149 (F) cells were left untreated or treated with 3 μM GO-203 for 48 h. Nuclear proteins were precipitated with anti-MUC1-C or a control IgG. Input and the precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against the indicated proteins. G and H. BT-549 (G) and SUM149 (H) cells were left untreated or treated with 3 μM GO-203 for 48 h. Nuclear lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against the indicated proteins.

MUC1-C forms a complex with PARP1 and regulates PARP activity

PARP1 plays multiple roles in DNA repair, including the modulation of chromatin structure and repair of DSBs by recruitment of BMI1 and EZH2 to sites of DNA damage (12,28,30,32,33). As reported for BMI1 and EZH2, MUC1-C was also detectable in nuclear complexes with PARP1 (Figs. 6A and Supplemental Fig. S7A). The formation of nuclear MUC1-C/PARP1 complexes was increased by CDDP treatment (Figs. 6B and 6C), but was unaffected by olaparib exposure (Fig. 6D and Supplemental Fig. S5B), indicating that the association is independent of PARP-mediated PARylation. Targeting MUC1-C had no apparent effect on PARP1 expression (Supplemental Figs. S7C and S7D). However, targeting MUC1-C with silencing or GO-203 treatment significantly decreased PARP1 activity when used alone and in combination with olaparib (Figs. 6E and 6F), demonstrating that MUC1-C is of importance for PARP1 activation.

Figure 6. MUC1-C forms a complex with PARP1 and regulates PARP activity.

A-D. BT-549 cells were left untreated and treated with (i) 10 μM CDDP for 24 h (A), (ii) 10 μM CDDP for the indicated times (B,C), or (iii) 3 μM olaparib (D) for 48 h. Nuclear proteins were precipitated with anti-MUC1-C, anti-PARP1 or a control IgG. Input and the precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against the indicated proteins. Intensity of the signals in B and C (upper panels) were determined using ImageJ 1.51k software and are expressed as relative values compared to that obtained for untreated cells (assigned a value of 1). The results are representative of two separate experiments. E and F. BT-549/tet-MUC1shRNA (E) and SUM149/tet-MUC1shRNA (F) cells were treated with 500 ng/ml DOX, 1 μM GO-203 or 3 μM olaparib alone and in combination for 7 days. Lysates were analyzed for PARP activity. The results are expressed as relative PARP activity (mean±SD of three determinations) as compared to that obtained from control cells (assigned a value of 1). The asterisk denotes a p value of <0.05.

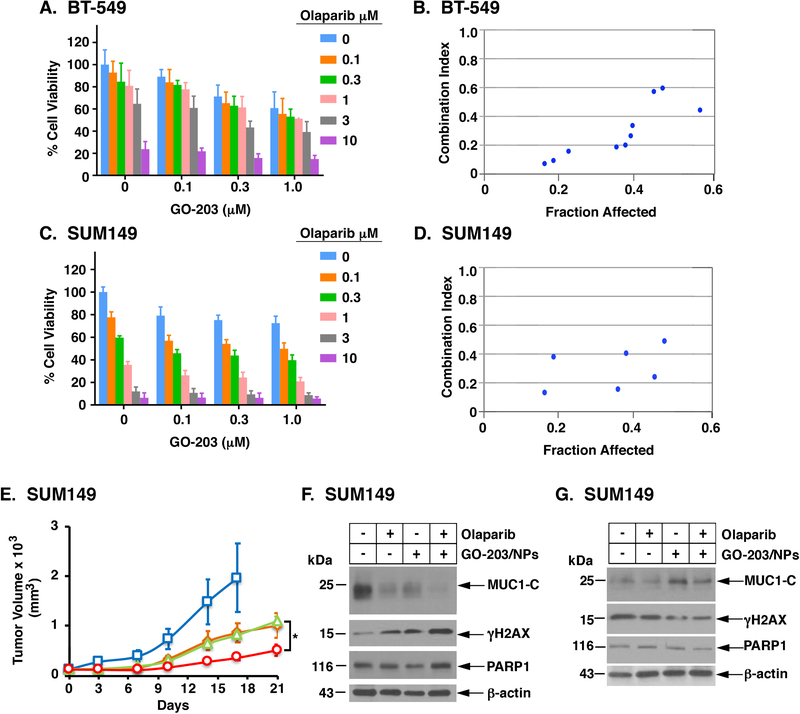

Olaparib and GO-203 are synergistic in the treatment of TNBC cells

The demonstration that MUC1-C contributes to PARP1 activity invoked the possibility that targeting MUC1-C could have an effect on olaparib sensitivity. To address this notion, we first defined the half-maximal inhibitory concentrations of olaparib and GO-203 when used alone (Supplemental Figs. S8A and S8B). In studies of BT-549 cells, low μM concentrations of GO-203 were combined with olaparib (0.1 to 10 μM) (Fig. 7A), demonstrating synergistic activity with the combinations as evidenced by CI values of less than 1.0 (Fig. 7B). Similar results were obtained with SUM149 cells (Figs. 7C and 7D), indicating that the synergy occurs in TNBC cells with mutant and wild-type BRCA1. To extend these results, we also defined sensitivity of the wild-type BRCA1 MDA-MB-468 and SUM159 cells to olaparib and GO-203 alone (Supplemental Figs. S9A and S9B) and in combination, here again observing marked synergy for treatment with these agents (Supplemental Figs. S10A-S10D). The reproducibility of these results in four different types of TNBC cells provided strong support for the observed mechanistic interaction between these agents. Consistent with these findings, treatment of established SUM149 tumor xenografts with the combination of olaparib and GO-203 encapsulated in nanoparticles (GO-203/NPs) for sustained delivery was more effective in inhibiting growth than either agent alone (Fig. 7E) without an increase in toxicity (Supplemental Fig. S11). In concert with the results obtained in in vitro studies, analysis of tumors harvested on day 7 of treatment demonstrated decreases in MUC1-C and increases in γH2AX as compared to the control untreated cells (Fig. 7F). In contrast, analysis of tumors surviving GO-203/NP treatment alone and in combination with olaparib exhibited increases in MUC1-C levels and decreases in γH2AX (Fig. 7G), consistent in part with a role for MUC1-C in attenuating the formation of DSBs and blocking death of cancer cells in the DDR (7–9). These findings thus confirmed proof-of-mechanism observed in vitro and demonstrated that GO-203 can be combined with olaparib to enhance anti-tumor activity.

Figure 7. Synergistic activity of GO-203 and olaparib in the treatment of TNBC cells.

A-D. BT-549 (A,B) and SUM149 (C,D) cells were left untreated or treated with 0.1, 0.3 or 1.0 μM GO-203 in the absence or presence of the indicated concentrations of olaparib. Cell viability (mean±SD of at least three determinations) was determined by Alamar blue staining (left panels) and was used to calculate the CI values (right panels), which at <1.0 denote synergism. E. Nude mice bearing established SUM149 tumors were randomized into four groups and treated IP with vehicle control (blue squares), GO-203/NPs (green triangles), olaparib (orange diamonds) and GO-203/NPs plus olaparib (red circles). The results are expressed as tumor volume (mean±SEM; 6 mice per group). F-G. Lysates from tumors harvested on day 7 (F) and at the end of treatment (G) were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against the indicated proteins.

Discussion

Treatment of TNBC is limited by a lack of actionable targets and an aggressive phenotype that is often refractory to cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents (34). MUC1-C is an oncoprotein that is expressed in over 90% of TNBCs (2,35) and is of importance to multiple hallmarks of the TNBC cell, including EMT (36), the CSC state (37–39) and epigenetic reprogramming with downregulation of TSGs (29,40,41). In TNBCs, 6–8% harbor BRCA1 mutations and about 2.5% have BRCA2 mutations (42,43). The present studies were undertaken to determine whether MUC1-C plays a role in DNA repair of TNBC cells. Unexpectedly, silencing of MUC1-C in settings of wild-type and mutant BRCA1 was associated with the induction of DSBs as detected by increases in γH2AX. Treatment with the MUC1-C inhibitor GO-203, which blocks MUC1-C function, also induced γH2AX, suggesting that MUC1-C may be involved in the repair of DSBs. In support of this notion, we found that treatment with CDDP, a DNA strand crosslinking agent widely used for TNBC therapy (34), is associated with increases in nuclear MUC1-C levels. Along these lines, similar results were obtained from treatment with etoposide, an inhibitor of topoisomerase II and inducer of DNA strand breaks, suggesting that MUC1-C is targeted to the nucleus in the response to DNA damage. In support of a potential role in the DDR, targeting MUC1-C in combination with CDDP resulted in more pronounced induction of DSBs than obtained with CDDP alone and synergistically enhanced CDDP-induced cytotoxicity. Notably, few insights are available regarding potential involvement of MUC1-C in the DDR. MUC1-C interacts directly with the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase and the ATM substrate H2AX in breast cancer cells (44). MUC1-C also promotes the repair of ionizing radiation (IR)-induced γH2AX foci (44). However, the mechanistic basis for these observations has remained unclear and is of potential importance for exploiting MUC1-C as a target for enhancing treatment of TNBCs with PARP inhibitors.

The repair of DNA lesions is dependent on the relaxation of chromatin structure and repression of transcription (45). In this respect, the repressive PcG proteins play important functional roles in the repair of DSBs. The PRC1 component BMI1 in association with the catalytic member RING2 ubiquitylate H2A on K119 in the response to DSBs (46,47), a modification necessary for repressing the transcriptional machinery in the repair of DNA damage (48,49). In this way, silencing BMI1 inhibits DSB repair and enhances sensitivity to DNA damage (46). We found that targeting MUC1-C decreases nuclear BMI1 levels and, significantly, suppresses H2AUb1 levels. In the hierarchical model, PRC1 is recruited to sites of PRC2-mediated H3K27 trimethylation (50,51). Our results further show that targeting MUC1-C is associated with suppression of nuclear EZH2 and H3K27me3 levels, indicating that MUC1-C could contribute to DNA repair by activating PRC2 and thereby the recruitment of PRC1. In support of the importance of both complexes in DNA repair, PRC1 and PRC2 are recruited to sites of DNA damage and loss of either one decreases survival in the response to IR-induced DNA damage (32,33,52). The findings that MUC1-C is necessary for PRC1 and PRC2 function in the DDR thus provide a mechanistic explanation for the effects of targeting MUC1-C on the induction of DSBs and the synergy observed with CDDP treatment.

Of interest for the present work were the previous observations that PRC1 and PRC2 are recruited by PARP1 to sites of DNA lesions (32). PARP1 plays multiple roles in the DDR, including chromatin remodeling and transcriptional regulation (12,20). PARP1 thus facilitates chromatin relaxation and inhibition of transcription required for the faithful repair of DSBs (12,20). Our findings that MUC1-C contributes to histone modifications in the DDR invoked the possibility that MUC1-C might also play a role in the regulation of PARP1 activity. MUC1-C interactions with BMI1 and EZH2 and the PARP1-mediated recruitment of these PRC proteins to sites of DNA damage (32) led to the demonstration that MUC1-C also forms a complex with PARP1. Moreover, we found that this association is increased by DNA damage and is not dependent on PARP1 activity. The formation of MUC1-C/PARP1 complexes could be mediated by EZH2, the activity of which is inhibited by PARP1-directed PARylation (30,53). By contrast, MUC1-C activates EZH2 (29), indicating that MUC1-C and PARP1 may play counteracting roles in the regulation of H3K27me3 levels. In addition to this line of thinking, we found that MUC1-C is of importance for the regulation of PARP1 activation. Targeting MUC1-C genetically and pharmacologically decreased PARP1 activity. One potential explanation for these findings is that MUC1-C promotes the recruitment of BMI1 and EZH2, which are necessary for chromatin relaxation, and their absence decreases PARP1 activity. An alternative, but not mutually exclusive role, is that MUC1-C can directly function in regulating PARP1 activation. As reported for BMI1 and EZH2, PARP1 also recruits the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylation (NuRD) complex to sites of DNA damage (32), invoking the possibility that MUC1-C may similarly contribute to regulation of NuRD components in the DDR. Further studies will thus be needed to define these potentially indirect and/or direct effects of MUC1-C on PARP1 activity; however, the finding that targeting MUC1-C suppresses PARP1 could have additional implications for the clinical development of PARP inhibitors.

A role for MUC1-C in the DDR extends its involvement in driving EMT, the CSC state, anti-cancer drug resistance and other hallmarks of the cancer cell (3,4). Our findings that targeting MUC1-C induces DSBs and is synergistic with CDDP uncover a potential clinical opportunity for designing combinations with genotoxic anti-cancer agents (4). Previously, we showed that localization of MUC1-C to the mitochondrial outer membrane confers resistance to CDDP and etoposide by blocking the apoptotic response to DNA damage (7). The present results extend those observations by demonstrating that MUC1-C also plays a role in promoting DNA repair and, accordingly, could function in integrating the DDR with induction of apoptosis. Our findings further underscore the potential for targeting MUC1-C in combination with PARP1 inhibitors, which have been approved for the treatment of BRCA-mutated breast and ovarian cancer (16). Functional BRCA1/2 proteins are critical for repair of DSBs (54). However, PARP1 inhibition can be associated with the survival of BRCA reversion mutations (18), emphasizing the need for additional strategies to enhance the effectiveness of olaparib and other PARP inhibitors. Given these clinical challenges, our results indicate that targeting MUC1-C is synergistic with olaparib in settings of both mutant and wild-type BRCA. In this potential therapeutic capacity, the MUC1-C inhibitor GO-203 has been evaluated in a Phase I trial as monotherapy for patients with cancer and has demonstrated an acceptable safety profile and evidence of clinical activity. The finding that GO-203 has a short circulating half-life in patients necessitated the reformulation of GO-203 in nanoparticles (GO-203/NPs) for less frequent delivery and more prolonged drug exposure (21). The present findings that GO-203 is effective in combination with olaparib support the premise that targeting MUC1-C could enhance the activity of PARP inhibitors against TNBCs with mutant and wild-type BRCA, consistent in part with a role for MUC1-C in attenuating the formation of DSBs and blocking death of cancer cells in the DDR (7–9). Our findings also provide the experimental basis for further preclinical evaluation of this combination in terms of dosing, number of cycles and effects on survival in additional TNBC, ovarian and other tumor models.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Findings demonstrate that targeting MUC1-C disrupts epigenetics of the PARP1 complex, inhibits PARP1 activity, and is synergistic with olaparib in TNBC cells.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grants from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers CA97098, CA166480, CA216553 and CA233084.

Abbreviations

- MUC1

mucin 1

- MUC1-C

MUC1 C-terminal subunit

- MUC1-C/ED

MUC1-C extracellular domain

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- CDDP

cisplatin

- DSB

DNA double-strand break

- DDR

DNA damage response

- HR

homologous recombination

- BRCA1

breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein

- TNBC

triple-negative breast cancer

- DOX

doxycycline

- IDP

intrinsically disordered protein

- IF

immunofluorescence

- CI

combination index

- NuRD

nucleosome remodeling and deacetylation

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: DK has equity interests in, serves as a member of the board of directors of and is a paid consultant to Genus Oncology. The other authors disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kufe D Mucins in cancer: function, prognosis and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2009;9:874–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kufe D MUC1-C oncoprotein as a target in breast cancer: activation of signaling pathways and therapeutic approaches. Oncogene 2013;32:1073–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajabi H, Kufe D. MUC1-C oncoprotein integrates a program of EMT, epigenetic reprogramming and immune evasion in human carcinomas. BBA Reviews on Cancer 2017;1868:117–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajabi H, Hiraki M, Kufe D. MUC1-C activates polycomb complexes and downregulates tumor suppressor genes in human cancer cells. Oncogene 2018;37:2079–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh A, Settleman J. EMT, cancer stem cells and drug resistance: an emerging axis of evil in the war on cancer. Oncogene 2010;29:4741–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shibue T, Weinberg RA. EMT, CSCs, and drug resistance: the mechanistic link and clinical implications. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017;14:611–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ren J, Agata N, Chen D, Li Y, Yu W-H, Huang L, et al. Human MUC1 carcinoma-associated protein confers resistance to genotoxic anti-cancer agents. Cancer Cell 2004;5:163–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei X, Xu H, Kufe D. Human MUC1 oncoprotein regulates p53-responsive gene transcription in the genotoxic stress response. Cancer Cell 2005;7:167–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raina D, Ahmad R, Kumar S, Ren J, Yoshida K, Kharbanda S, et al. MUC1 oncoprotein blocks nuclear targeting of c-Abl in the apoptotic response to DNA damage. EMBO J 2006;25:3774–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uchida Y, Raina D, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. Inhibition of the MUC1-C oncoprotein is synergistic with cytotoxic agents in treatment of breast cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther 2013;14:127–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shukla SK, Purohit V, Mehla K, Gunda V, Chaika NV, Vernucci E, et al. MUC1 and HIF-1alpha signaling crosstalk induces anabolic glucose metabolism to impart gemcitabine resistance to pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell 2017;32:71–87 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ray Chaudhuri A, Nussenzweig A. The multifaceted roles of PARP1 in DNA repair and chromatin remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2017;18:610–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li M, Yu X. Function of BRCA1 in the DNA damage response is mediated by ADP-ribosylation. Cancer Cell 2013;23:693–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cruz-Garcia A, Lopez-Saavedra A, Huertas P. BRCA1 accelerates CtIP-mediated DNA-end resection. Cell Rep 2014;9:451–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu Y, Petit SA, Ficarro SB, Toomire KJ, Xie A, Lim E, et al. PARP1-driven poly-ADP-ribosylation regulates BRCA1 function in homologous recombination-mediated DNA repair. Cancer Discov 2014;4:1430–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ashworth A, Lord CJ. Synthetic lethal therapies for cancer: what’s next after PARP inhibitors? Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018;15:564–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lord CJ, Ashworth A. BRCAness revisited. Nat Rev Cancer 2016;16:110–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drean A, Williamson CT, Brough R, Brandsma I, Menon M, Konde A, et al. Modeling therapy resistance in BRCA1/2-nutant cancers. Mol Cancer Ther 2017;16:2022–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohmoto A, Yachida S. Current status of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors and future directions. OncoTargets Ther 2017;10:5195–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ciccarone F, Zampieri M, Caiafa P. PARP1 orchestrates epigenetic events setting up chromatin domains. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2016;63:123–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasegawa M, Sinha RK, Kumar M, Alam M, Yin L, Raina D, et al. Intracellular targeting of the oncogenic MUC1-C protein with a novel GO-203 nanoparticle formulation. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:2338–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Yu W-H, Ren J, Huang L, Kharbanda S, Loda M, et al. Heregulin targets γ-catenin to the nucleolus by a mechanism dependent on the DF3/MUC1 protein. Mol Cancer Res 2003;1:765–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Regul 1984;22:27–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leng Y, Cao C, Ren J, Huang L, Chen D, Ito M, et al. Nuclear import of the MUC1-C oncoprotein is mediated by nucleoporin Nup62. J Biol Chem 2007;282:19321–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raina D, Ahmad R, Rajabi H, Panchamoorthy G, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. Targeting cysteine-mediated dimerization of the MUC1-C oncoprotein in human cancer cells. Int J Oncol 2012;40:1643–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raina D, Agarwal P, Lee J, Bharti A, McKnight C, Sharma P, et al. Characterization of the MUC1-C cytoplasmic domain as a cancer target. PLoS One 2015;10:e0135156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Liu D, Chen D, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. Human DF3/MUC1 carcinoma-associated protein functions as an oncogene. Oncogene 2003;22:6107–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin X, Ojo D, Wei F, Wong N, Gu Y, Tang D. A novel aspect of tumorigenesis-BMI1 functions in regulating DNA damage response. Biomolecules 2015;5:3396–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajabi H, Hiraki M, Tagde A, Alam M, Bouillez A, Christensen CL, et al. MUC1-C activates EZH2 expression and function in human cancer cells. Sci Rep 2017;7:7481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caruso LB, Martin KA, Lauretti E, Hulse M, Siciliano M, Lupey-Green LN, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase 1, PARP1, modifies EZH2 and inhibits EZH2 histone methyltransferase activity after DNA damage. Oncotarget 2018;9:10585–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Das C, Lucia MS, Hansen KC, Tyler JK. CBP/p300-mediated acetylation of histone H3 on lysine 56. Nature 2009;459:113–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chou DM, Adamson B, Dephoure NE, Tan X, Nottke AC, Hurov KE, et al. A chromatin localization screen reveals poly (ADP ribose)-regulated recruitment of the repressive polycomb and NuRD complexes to sites of DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:18475–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campbell S, Ismail IH, Young LC, Poirier GG, Hendzel MJ. Polycomb repressive complex 2 contributes to DNA double-strand break repair. Cell Cycle 2013;12:2675–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bianchini G, Balko JM, Mayer IA, Sanders ME, Gianni L. Triple-negative breast cancer: challenges and opportunities of a heterogeneous disease. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016;13:674–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siroy A, Abdul-Karim FW, Miedler J, Fong N, Fu P, Gilmore H, et al. MUC1 is expressed at high frequency in early-stage basal-like triple-negative breast cancer. Hum Pathol 2013;44:2159–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajabi H, Alam M, Takahashi H, Kharbanda A, Guha M, Ahmad R, et al. MUC1-C oncoprotein activates the ZEB1/miR-200c regulatory loop and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncogene 2014;33:1680–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alam M, Ahmad R, Rajabi H, Kharbanda A, Kufe D. MUC1-C oncoprotein activates ERK→C/EBPβ-mediated induction of aldehyde dehydrogenase activity in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem 2013;288:30829–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hasegawa M, Takahashi H, Rajabi H, Alam M, Suzuki Y, Yin L, et al. Functional interactions of the cystine/glutamate antiporter, CD44v and MUC1-C oncoprotein in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Oncotarget 2016;7:11756–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alam M, Rajabi H, Ahmad R, Jin C, Kufe D. Targeting the MUC1-C oncoprotein inhibits self-renewal capacity of breast cancer cells. Oncotarget 2014;5:2622–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rajabi H, Tagde A, Alam M, Bouillez A, Pitroda S, Suzuki Y, et al. DNA methylation by DNMT1 and DNMT3b methyltransferases is driven by the MUC1-C oncoprotein in human carcinoma cells. Oncogene 2016;35:6439–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hiraki M, Maeda T, Bouillez A, Alam M, Tagde A, Hinohara K, et al. MUC1-C activates BMI1 in human cancer cells. Oncogene 2016;36:2791–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Couch FJ, Hart SN, Sharma P, Toland AE, Wang X, Miron P, et al. Inherited mutations in 17 breast cancer susceptibility genes among a large triple-negative breast cancer cohort unselected for family history of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:304–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimelis H, LaDuca H, Hu C, Hart SN, Na J, Thomas A, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer risk genes identified by multigene hereditary cancer panel testing. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang L, Liao X, Beckett M, Li Y, Khanna KK, Wang Z, et al. MUC1-C oncoprotein interacts directly with ATM and promotes the DNA damage response to ionizing radiation. Genes & Cancer 2010;1:239–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stadler J, Richly H. Regulation of DNA repair mechanisms: How the chromatin environment regulates the DNA damage response. Int J Mol Sci 2017;18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ismail IH, Andrin C, McDonald D, Hendzel MJ. BMI1-mediated histone ubiquitylation promotes DNA double-strand break repair. J Cell Biol 2010;191:45–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ginjala V, Nacerddine K, Kulkarni A, Oza J, Hill SJ, Yao M, et al. BMI1 is recruited to DNA breaks and contributes to DNA damage-induced H2A ubiquitination and repair. Mol Cell Biol 2011;31:1972–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kakarougkas A, Ismail A, Chambers AL, Riballo E, Herbert AD, Kunzel J, et al. Requirement for PBAF in transcriptional repression and repair at DNA breaks in actively transcribed regions of chromatin. Mol Cell 2014;55:723–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ui A, Nagaura Y, Yasui A. Transcriptional elongation factor ENL phosphorylated by ATM recruits polycomb and switches off transcription for DSB repair. Mol Cell 2015;58:468–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koppens M, van Lohuizen M. Context-dependent actions of Polycomb repressors in cancer. Oncogene 2016;35:1341–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Comet I, Riising EM, Leblanc B, Helin K. Maintaining cell identity: PRC2-mediated regulation of transcription and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2016;16:803–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vissers JH, van Lohuizen M, Citterio E. The emerging role of Polycomb repressors in the response to DNA damage. J Cell Sci 2012;125:3939–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamaguchi H, Du Y, Nakai K, Ding M, Chang SS, Hsu JL, et al. EZH2 contributes to the response to PARP inhibitors through its PARP-mediated poly-ADP ribosylation in breast cancer. Oncogene 2018;37:208–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lord CJ, Ashworth A. PARP inhibitors: Synthetic lethality in the clinic. Science 2017;355:1152–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.