Abstract

The F9/Yde/Fml pilus, tipped with the FmlH adhesin, has been shown to provide uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) a fitness advantage in urinary tract infections (UTIs). Here, we used X-ray structure guided design to optimize our previously described ortho-biphenyl Gal and GalNAc FmlH antagonists such as compound 1 by replacing the carboxylate with a sulfonamide as in 50. Other groups which can accept H-bonds were also tolerated. We pursued further modifications to the biphenyl aglycone resulting in significantly improved activity. Two of the most potent compounds, 86 (IC50 = 0.051 μM) and 90 (IC50 = 0.034 μM), exhibited excellent metabolic stability in mouse plasma and liver microsomes but showed only limited oral bioavailability (<1%) in rats. Compound 84 also showed a good pharmacokinetic (PK) profile in mice after IP dosing with compound exposure above the IC50 for 6 h. These new FmlH antagonists represent new antivirulence drugs for UTIs.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The global rise in infections attributable to multidrug resistant bacteria represents a serious and immediate public health crisis. Globally, 700000 people die each year from infections caused by antibiotic resistant organisms, and by 2050, these infections are predicted to kill up to 10 million people annually with an economic burden of approximately $100 trillion U.S. dollars.1 To curb the spread of antibiotic resistance while effectively treating a wide range of bacterial infections, the need for alternative antimicrobial therapeutics has never been greater. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are one of the most common and costly bacterial infections in the world, affecting approximately 50% of women during their lifetimes and leading to $2.5 billion in healthcare costs annually in the United States alone.2,3 Over 10% of all antibiotic treatment regimens administered to patients in the United States are prescribed for the treatment of UTI.4,5 The overwhelming majority of community-and hospital-associated UTIs are caused by Gramnegative uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) strains.6

UPEC encode a variety of virulence factors that facilitate their colonization and persistence of numerous habitats including the gastrointestinal and urinary tracts. One of the most important and well-studied determinants of UPEC urovirulence are chaperone-usher pathway (CUP) pili.7 CUP pili are proteinaceous extracellular fibers expressed by E. coli and other Gram-negative pathogens that are tipped with adhesins, which bind to receptors with stereochemical specificity to mediate colonization, invasion, and biofilm formation.8 The E. coli pan genome encodes 38 distinct CUP pilus types, and individual E. coli strains can encode between 6 and 16 CUP pili.9 The pilus known to be critical in UTI pathogenesis is the type 1 pilus.10−12 Type 1 pili are tipped with the FimH adhesin that recognizes mannosylated glycoproteins in the gut and in the bladder, an event that is critical for colonization, invasion, and biofilm formation in these various habitats.10 Thus, fimH mutants are severely attenuated in virulence and tight-binding FimH inhibitors called biaryl mannosides have been shown to be orally bioavailable and highly efficacious in the treatment and prevention of UTI.13−18 Fml pili are composed of thousands of repeating FmlA subunits assembled into a rod that is tipped with a two-domain adhesin, FmlH. FmlH recognizes terminal galactose (Gal) and N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) residues found in core-1 and −2 O-glycans decorating glycoproteins in the bladder exposed during chronic inflammation.11 Fml pili can also recognize Thomsen—Friedenreich (TF) antigen (Galβ1—3GalNAc) on the kidney epithelium to facilitate kidney infection (pyelonephritis).12 Cocrystal structures of the FmlH lectin domain (FmlHLD) bound to natural and synthetic ligands reveal a solvent-exposed receptor binding pocket composed of three loops at the distal tip of FmlH that confers specificity for the GalNAc receptor.11 Loop 1 comprises residues S9-A13, loop 2 comprises residues N44-D53, and loop 3 comprises residues K132-N143 (Figure 1). Deletion of the fml operon from clinical UPEC isolates results in a competitive defect in the bladder and kidney in mouse models of chronic UTI.11

Figure 1.

FmlH bound to initial lead compound 1 (PDB 6AS8). The COOH group on ring B engages in charge—charge interactions with guanidinium side chain of R142, while a series of direct and water- mediated H-bonds between the acetamide moiety and residue K132. Additionally, phenyl ring A forms edge-to-face π-stacking interactions with Y46.

Our previous studies have utilized X-ray crystallography structure-based ligand design and directed organic synthesis to develop high-affinity compounds that can competitively inhibit FmlH binding to inflamed bladder tissue ex vivo.12 Using Onitrophenyl β-galactoside (ONPG) as a basis for further functionalization, compound 1 was developed. Compound 1 contains a GalNAc sugar ring attached to an ortho-biphenyl ring substituted with a carboxylic acid moiety in the meta position of the B-ring. The A-ring of the biphenyl aglycone exploits edge-to-face π-stacking interactions with Y46, while the acetamide and the B-ring makes polar contacts with R142 in loop 3 to increase potency (Figure 1). Compound 1 achieves 50% inhibition of FmlH binding to serine-TF moieties in an ELISA-based assay at a concentration of 0.64 μM. When tested further in a kinetic binding assay, compound 1 displayed a dissociation constant (Kd) of 0.089 μM.12 Further, compound 1 was shown to be able to significantly reduce bladder and kidney CFUs in a treatment model of chronic cystitis. Co-administration of FmlH inhibitor 1 with 4Z269, a potent mannoside inhibitor of FimH, further reduced bacterial titers in both the bladder and kidney. This suggests the possibility for synergistic combination treatment as an antibiotic-sparing therapeutic approach against UTI which has been reviewed recently.19,20 The structural basis of the affinity of other CUP pili for their cognate ligands has also been determined. For example, the PapG adhesin on the P pilus is known to bind Gal-containing globosides in the kidney. However, the structure and orientation of the PapG binding pocket relative to that of FmlH show little structural or genetic homology.

Herein, we have rationally modified compound 1 to optimize ligand binding geometry and increase its inhibitory effect on FmlH binding based on the cocrystal structure of compound 1 bound to FmlH. We then conducted functional and structural studies on these compounds to expand our understanding of the structure–activity relationships (SAR) of these new high-affinity FmlH ligands. Studies evaluating the physical and pharmacokinetic (PK) properties of new lead compounds were also pursued. These compounds represent new and promising antibiotic-sparing drugs for the treatment of chronic UTI.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Design and Synthesis of Biphenyl Galactosides and Galactosaminosides.

To improve the binding affinity and potency of previous lead biphenyl GalNAc 1, we utilized the FmlH-1 cocrystal structure (Figure 1) as a guide. Initially, we replaced the meta carboxylic acid with a variety of other functional groups to further exploit the charge—charge and hydrogen bonding (H-bonding) interactions with the guanidinium side chain of R142 and K132. The general synthetic routes for these biphenyl GalNAc and Gal analogues are shown in Scheme 1. The key 2-bromophenyl GalNAc and Gal intermediates, 4 and 5, respectively, were synthesized by Koenig—Knorr type glycosylation reaction.21−25 Compound 4 (Scheme 1A) was synthesized from protected galactosamine chloride 226 using dichloromethane (DCM), 1N aq. sodium hydroxide (NaOH), tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBAB). and 2-bromophenol at room temperature, whereas compound 5 (Scheme 1B) was synthesized from readily available peracetylated galactose bromide 3 using chloroform (CHCl3), 1N aq NaOH, benzyltriethylammonium chloride (tEBAC), and 2-bromophenol at 60 °C in good yield. Next, compounds 4 and 5 were subjected to a Suzuki cross-coupling reaction14,27 with various phenylboronic acids using Pd- (PPh3)4, Cs2CO3, and 1,4-dioxane/water (5:1) at 80 °C to generate protected biphenyl intermediates 6−28. The target meta-nitro (29), para-methoxy (31) GalNAc, and meta-nitro (30) Gal biphenyl carboxylic acid analogues were then obtained from the dual deprotection and saponification of the esters 8−10. All other compounds 32−51 were synthesized via treatment with 33% methylamine in absolute ethanol solution from precursors 11−28. All final target molecules 29−51 were purified to by reverse phase preparatory HPLC using a C18 column, resulting in compounds with >95% purity in excellent overall yields.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Biphenyl Glycoside Compounds (29–51)a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) DCM, 1N NaOH, TBAB, 2-bromophenol, rt, 1 h; (b) Pd(PPh3)4, Cs2CO3, 1,4-dioxane/water (5:1), 80 °C, 1 h; (c) NaOH, methanol/water (1:1), rt, overnight for 29–31 or 33% methylamine in absolute ethanol, rt, 1 h for 32–51; (d) CHCl3, 1N NaOH, TEBAC, 2-bromophenol, rt, 1 h. See Table 1 for identity of R1, R2, and R3.

Biochemical Analysis of ortho-Biphenyl Gal and GalNAc Compounds 29−51.

The ability of the newly synthesized Gal and GalNAc analogues 29—51 to inhibit FmlH activity was assessed using our previously described enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).12 This competitive binding assay measures the concentration of compound required to inhibit 50% of binding (IC50) to desialylated bovine submaxillary mucin, which contains high levels of Gal and GalNAc epitopes. The resultant IC50 values for each compound are shown in Table 1. The majority of compounds (32−42, 45−48) had equal or slightly reduced potency relative parent compound 1. It is noteworthy that the ortho-methoxy biphenyl GalNAc carboxylic analogue 31 showed the weakest activity with a 6-fold drop in activity (IC50, 3.9 μM) relative to 1. It would be tempting to speculate that this could be the result of forced ring twisting of the B-ring due to steric interference from the large ortho substituent. However, changing the carboxylic acid to a smaller phenol in compound 34 increases the potency (IC50, 0.51 μM) back to the level of compound 1 and is equivalent to the desmethoxy analogue 32. The potency was slightly enhanced when the acid is replaced with a reverse amide as in 43 (IC50, 0.31 μM) but decreases in the normal amide 47 (IC50, 3.4 μM). However, the addition of a reverse methyl sulfonamide 50 resulted in a 3-fold greater potency than 1 (IC50 0.23 μM), but as in amide 47, the methyl sulfonamide derivative 51 showed a loss in activity relative to 1. This SAR suggests that distal placement of an H-bond acceptor (i.e., a carbonyl of the reverse amide or S=O bond of the sulfonamide) provides a greater binding benefit than a H-bond donor, presumably due to improved interactions with the Arg142 and/or Lys132 of FmlH. In general, we discovered that groups which can accept an H- bond in the meta position of the B-ring show the best activity.

Table 1.

Biological Data for Biphenyl Galactosides and Galactosaminosides 1, 29−51

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | R1 | R2 | R3 | IC50(μM)a,b |

| 1 | COOH | H | H | 0.64 |

| 29 | COOH | NO2 | H | 2.2 |

| 30 | COOH | NO2 | H | 0.28 |

| 31 | COOH | H | OMe | 3.9 |

| 32 | OH | H | H | 0.70 |

| 33 | OSO2Me | H | H | 0.89 |

| 34 | OH | H | OMe | 0.51 |

| 35 | OSO2Me | H | OMe | 3.7 |

| 36 | F | H | H | 1.5 |

| 37 | OMe | H | H | 2.0 |

| 38 | NO2 | H | H | 2.7 |

| 39 | CN | H | H | 0.97 |

| 40 | CF3 | H | H | 1.5 |

| 41 | SO2Me | H | H | 0.70 |

| 42 | CH2OH | H | H | 0.63 |

| 43 | NHCOMe | H | H | 0.31 |

| 44 | NHCOCF3 | H | H | 0.37 |

| 45 | NHCO2Me | H | H | 0.63 |

| 46 | CON(Me)2 | H | H | 3.1 |

| 47 | CONHMe | H | H | 3.4 |

| 48 | CONH2 | H | H | 1.6 |

| 49 | NHSO2CF3 | H | H | 1.1 |

| 50 | NHSO2Me | H | H | 0.23 |

| 51 | NHSO2Me | H | H | 1.6 |

All the IC50 values are an average of four or more replicates

Standard deviations are provided in the Supporting Information

As with our previously reported FmlH ligands12 our lead biphenyl GalNAc sulfonamide 50 is more potent than its matched pair Gal derivative 51 by about 5-fold. We have demonstrated this trend in all paired analogues hitherto synthesized. However, we observed a reversal of this trend when the potency of compounds 29 and 30 were assessed, as the B-ring disubstituted 3-nitro 5-carboxy analogue 30 (IC50, 0.28 μM) was 6-fold more active than the corresponding GalNAc version 29 (IC50, 2.2 μM).

X-ray Structure Determination of Disubstituted Biphenyl Gal 30 and GalNAc 29 Matched Pairs Bound to the FmlH Lectin Domain.

To determine the structural basis for the divergent SAR of Gal (30) versus GalNAc (29) and attempt to explain the unfavorable effect on binding from the N-acetyl group on GalNAc 29 potency relative to Gal 30, we obtained cocrystals and solved the X-ray structures of both 30 and 29 in complex with FimHLD to 1.39 and 1.31 Å resolution, respectively (Figure 2A,B). Surprisingly, we found that the nitro group on the biphenyl B-ring, and not the carboxylic acid as previously observed, was bound in the pocket with R142. This contrasts with the FmlH cocrystal structure of 1, in which the carboxylic acid occupies that pocket (Figure 1). In both the 29 and 30 structures, the nitro oxygens on the second phenyl ring (B) form two interactions with R142, while the carboxyl oxygens of the carboxylic acid group interact with S2 on the N terminus and the backbone of I11 and G12 in loop 1. In compound 29, one nitro oxygen resides within 3.2 Å of the acetamide carbonyl, causing the second phenyl ring to tilt 45° relative to the plane of the first phenyl ring. In contrast, the angular offset between the plane of the two rings is 32.5° in 30, altering the position of the carboxylic acid oxygens and attenuating their interaction with loop 1 residues I11 and G12.

Figure 2.

X-ray crystal structure of FmlHLD in complex with (A) Gal 30 (PDB 6MAP) and (B) GalNAc 29 (PDB 6MAQ) matched pairs. Direct and water-mediated interactions between the N-acetyl group on the galactose ring and the nitro group on the second phenyl ring result in decreased relative potency.

Substitution of the Reverse Methyl Sulfonamide Scaffold (50) Further Increases Galactoside Potency.

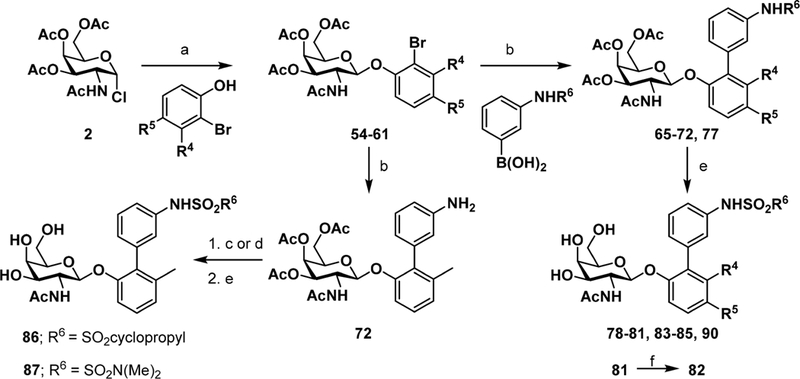

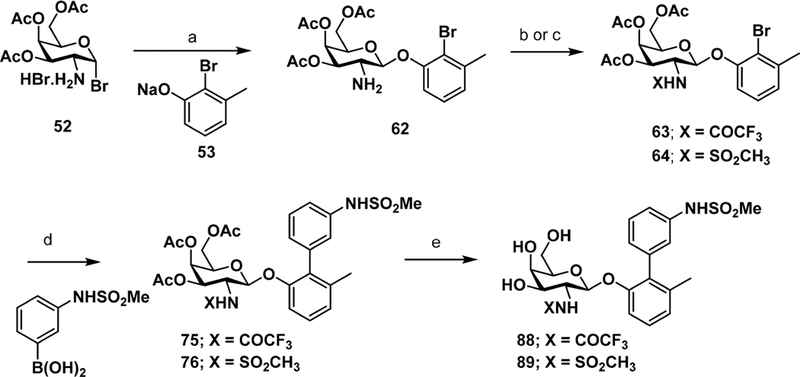

To further improve the potency of lead compound 50, we explored a series of additional rationally directed modifications. These include substitutions at the meta (R4) and para (R5)-positions of the biphenyl ring A while keeping the meta substituted methyl sulfonamide B ring constant (78−85, 90; Table 2). We also evaluated different sulfonamides as in 86−87 and N-substitutions on the GalNAc ring including 88 and 89. This focused library of substituted biphenyl sulfonamide analogues were synthesized as outlined in Scheme 2 and the N-substituted galactosamine derivatives 88−89 in Scheme 3. Compounds 78−85 and 90 were synthesized following a similar reaction sequence as described in Scheme 1. However, sulfonamide analogues 86 and 87 were prepared via sulfonylation of intermediate aniline 72. As shown in Scheme 3, GalNAc derivatives 88 and 89 were generated first by Koenig−Knorr type glycosylation reaction28 between 3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-2-amino-2-deoxy-α-D-galactopynosyl bromide-HBr29 (52) and sodium 2-bromo-3-methylphenolate30 (53) to give bromide intermediate 62. Derivatization with trifluoroacetic acid anhydride or methanesulfonyl chloride yielded N-substituted galactosamine intermediates 75 and 76. Subsequent Suzuki cross-coupling reaction with (3-(methylsulfonamido)phenyl)boronic acid followed by treatment with 33% methylamine in absolute ethanol provided the target compounds 88 and 89.

Table 2.

Compounds (78—90) Comparison of Biological Activity

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | X | R4 | R6 | IC50(nM)a,b |

| 78 | Ac | NO2 | Me | 58 |

| 79 | Ac | CN | Me | 44 |

| 80 | Ac | F | Me | 88 |

| 81 | Ac | CO2Bn | Me | 89 |

| 82 | Ac | CO2H | Me | 66 |

| 83 | Ac | OMe | Me | 92 |

| 84 | Ac | Me | Me | 62 |

| 85 | NA | NA | NA | 81 |

| 86 | Ac | Me | cyclopropyl | 51 |

| 87 | Ac | Me | N(Me)2 | 77 |

| 88 | COCF3 | Me | Me | 48 |

| 89 | SO2Me | Me | Me | 3500 |

| 90 | Ac | CF3 | Me | 34 |

All the IC50 values are an average of four or more replicates

Standard deviations are provided in the Supporting Information

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Biphenyl Glycosides to Explore A-Ring Substitution and B-Ring Sulfonamidesa.

aReagents and conditions: (a) DCM, 1N NaOH, TBAB, rt, 1 h; (b) Pd(PPh3)4, Cs2CO3, 1,4-dioxane/water (5:1), 80 °C, 1 h; (c) DCM, cyclopropanesulfonyl chloride/TEA, rt, 2 h, (d) DMF, N,N-dimethylsulfonyl chloride/Cs2CO3, MW, 80 °C, 2 h; (e) 33% methylamine in absolute ethanol, rt, 1 h; (f) NaOH, methanol/water (1:1), rt, overnight.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Biphenyl Glycosides Evaluating Effect of N-Substitution of GalNAc Ringa.

aReagents and conditions: (a) ACN, 80 °C, 2 h; (b) DCM, (CF3CO)2O/TEA, rt, 1 h; (c) DCM, MsCl/TEA, rt, 3 h; (d) Pd(PPh3)4, Cs2CO3, 1,4- dioxane/water (5:1), 80 °C, 1 h; (e) 33% methylamine in absolute ethanol, rt, 1 h.

The potency of all compounds 78−90 were assessed using the ELISA assay described above to measure the IC50. These values are shown in Table 2. All N-acetyl compounds had excellent activity with an IC50 of 100 nM or better. We found that all analogues substituted with any of the various functional groups installed at the ortho position (R4) of the biphenyl A-ring (relative to the B-ring) further improved IC50s relative to lead compound 50 (R4 = H). It is noteworthy that the cyclopropyl sulfonamide 86 and the dimethyl sulfonyl urea derivative 87 retain the same activity as the methyl sulfonamides. Compound 90, containing the methyl sulfonamide in the meta position of the biphenyl B-ring and a trifluoromethyl group in the ortho R4 position on the B-ring, exhibited the highest potency of the compounds tested, with an IC50 of 34 nM. Even the fused naphthyl A-ring 85 has excellent potency with an IC50 of 81 nM. When the sugar acetyl group of compound 84 is replaced, the trifluoroaceta- mide retains potent activity (IC50 62 nM) while the methyl sulfonamide loses significant activity with an IC50 of only 3.5 μM.

X-ray Structure Determination of Biphenyl Sulfonamide GalNAc 90 Bound to the FmlH Lectin Domain.

To determine the molecular basis for the high potency exhibited by the biphenyl sulfonamides and the corresponding SAR, we solved an X-ray crystal structure of compound 90 bound to FmlHLD. The cocrystal structure was solved to 1.75 Å resolution (Figure 3, PDB 6MAW). As previously observed in the 1-FmlHLD cocrystal structure (Figure 1), the terminal N-acetyl galactosamine ring forms key H-bonds with the amide backbone of F1, as well as the side chains of D45, Y46, and D53 in loop 2 and the side chains of K132 and N140 in loop 3.12 The nitrogen of the N-acetylgalactosamine group forms multiple H-bonds with K132 and a water molecule present in the binding pocket. We also observed an additional water- mediated H-bond between the N-acetylglucosamine carbonyl and R142 that had not been previously appreciated. In contrast to the structure of compound 1 bound to FmlH, in which has the carboxylate group of the biphenyl B-ring faces the N-acetyl group of the sugar and interacts with the pocket formed by R142 and K132, the sulfonamide is interacting in a pocket just opposite from this. This happens to be the same pocket the carboxylate of GalNAc 29 occupies (Figure 2A). The sulfonamide nitrogen atom of 90 forms a H-bond with the backbone carbonyl of F1. Additionally, one of the sulfonamide oxygens interacts with the side chain of S2, the side chain of S10 side chain and backbone of I11 in loop 1. The addition of the ortho-trifluoromethyl group to the biphenyl A-ring likely locks the position of the second phenyl ring at a preferred angle relative to the first ring, potentially providing a favorable entropic contribution to binding. Additionally, it is speculated that one of the fluorine atoms interacts directly with D45 and indirectly with S2 through a water molecule.

Figure 3.

X-ray crystal structure of FmlHLD in complex with 90 (PDB 6MAW). The sulfonyl oxygens form novel contacts with the backbone of S10 and I11 in loop 1 and the backbone of S2 in the N-terminus of the mature protein. Additionally, one fluorine in the trifluoromethyl group interacts with D45.

In Vitro Metabolic Stability Studies of Lead FmlH Antagonists.

Because of the labile nature of the O-glycosidic linkage of the biphenyl Gal and GalNAc FmlH antagonists, we pursued studies to evaluate their stability. To evaluate their therapeutic potential for advancing into planned animal studies, we assessed the aqueous solubility and in vitro stability of six leading compounds 79, 80, 84, 86, 88, and 90 based on their potency and structural diversity (Table 2). All compounds tested showed excellent aqueous solubility at pH 7.4 just below 200 μM. These compounds were assessed for their stability in simulated gastric fluid (SGF), simulated intestinal fluid (SIF), mouse liver microsomes, and blood plasma (Table 3). All compounds tested exhibited a high degree of stability, with some variation seen in the plasma stability. These findings are consistent with our earlier characterization of FimH antagonists (mannosides). In these studies, we demonstrated the lability of the O-glycosidic linkage27 that resulted in the appearance and detection of the phenol product of metabolism in mouse plasma and urine. With these promising results in vitro, we further tested the two most stable analogues, 86 and 90, for their pharmacokinetics (PK) in rats.

Table 3.

In Vitro Solubility and Metabolic Stability of Select FmlH Antagonists

| compd | SGF (% remaining @ 6 h) |

SIF (% remaining @ 2 h) |

mouse liver microsomes (t1/2min) |

mouse plasma (% remaining @ 2 h) |

kinetic solubility (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 79 | 87 | 100 | >145 | 89 | 196 |

| 80 | 92 | 94 | >145 | 89 | 197 |

| 84 | 100 | 100 | >145 | 100 | 195 |

| 86 | 100 | 100 | >145 | 84 | 196 |

| 88 | 91 | 89 | >145 | 89 | 164 |

| 90 | 89 | 92 | >145 | 92 | 197 |

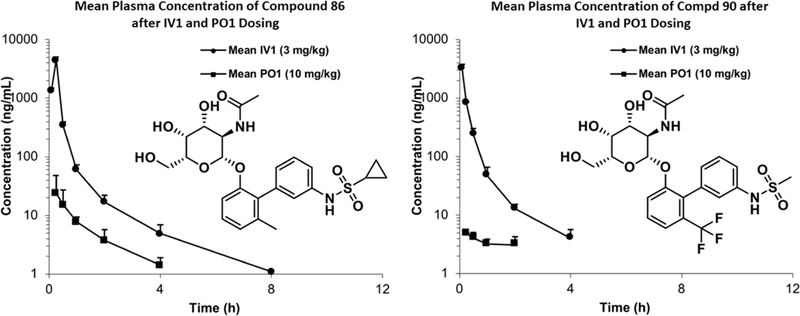

In Vivo Pharmacokinetic Studies.

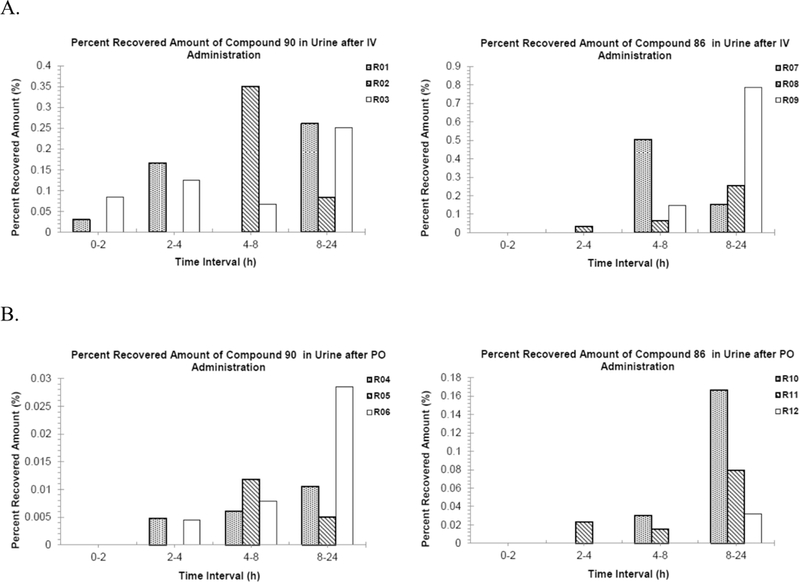

We determined the concentration of compounds 86 and 90 in rat plasma and urine following either a 10 mg/kg oral dose (PO; circular dots) or a 3 mg/kg intravenous dose (IV; square dots) (Figure 4). Analysis of the rat PK data (Supporting Information, Table S1) revealed that compound 86 has a longer long life (t1/2 = 1.46 h) and lower plasma clearance rate (Cl = 43.8 mL/min/kg) in plasma than compound 90 (t1/2 = 1.16 h and Cl = 57.0 mL/ min/kg). However, both compounds displayed low renal clearance to the urine (Figure 5) and an oral bioavailability (F) of less than 1%. Thus, the metabolic stability of these compounds and clearance of these compounds has no relation to the permeability (oral or otherwise) of compounds. The highly polar nature of these molecules containing the sugar GalNAc and multiple polar functionalities precludes their permeability in the gut.

Figure 4.

In vivo pharmacokinetics (PK) of 86 and 90 in rats.

Figure 5.

Urinary excretion of compounds 86 and 90 in rats after (A) IV administration and (B) PO administration. R01−R12 rats used for the renal excretion studies.

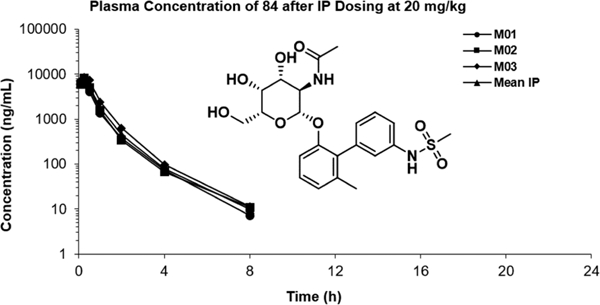

To determine if the improved PK properties of 86 relative to 90 are a consequence of the CH3 versus CF3 group on the biphenyl A-ring or the cyclopropyl sulfonamide versus methyl sulfonamide of the B-ring, we performed an additional study in mice with compound 84, the methyl sulfonamide derivative of 86, or the CH3 derivative of 90. This allowed us to determine the isolated effects of a single substitution. These studies were conducted via 20 mg/kg intraperitoneal (IP) injection to inform planned future IP studies in murine studies of chronic UTI, which require a single IP dose of galactoside to persist in the plasma for 6 h prior to measurement of bladder bacterial burdens (Figure 6)22

Figure 6.

In vivo pharmacokinetic properties of 84 in mice.

While not a perfect comparison to 86 and 90, the half-life, t1/2 in the mouse is calculated to be 1.13 h and the clearance rate appears to be slower than either that of 86 or 90. The compound 84 shows moderate compound exposure at 8 h with a Cmax of 7897 ng/mL and a calculated AUC of 6300 ng h/mL. This compound has an IC50 of 120 nM, which equates to a concentration of 57.7 ng/mL. At the 4 h time point, the average concentration of 84 was 79.5 ng/mL. By extrapolating these kinetics, we can infer that the plasma concentration of this compound would likely remain well above the IC50 for the 6 h, the exact time frame required for our murine model of chronic UTI.

CONCLUSION

High-affinity galactose and galactosamine-based ligands of FmlH have been rationally designed and optimized. These low- molecular-weight glycomimetics show great promise in the treatment and prevention of chronic UTI through inhibition of bacterial binding on both inflamed bladder and kidney tissue.11 A detailed structural understanding of the FmlH sugar binding pocket and surrounding residues is crucial to the development of high-affinity ligands that utilize multiple intermolecular contacts with the protein to significantly augment binding and potency. In this study, we designed and synthesized optimized FmlH antagonists with significantly increased potency relative to initial lead GalNAc 1.

We used iterative rounds of X-ray crystallography to design analogues with improved structure—activity relationships. The most potent of these compounds, 90, is an ortho-biphenyl which contains a sulfonamide moiety in the meta position on the distal B-ring of the biphenyl aglycone that engages in novel polar contacts with loop 1 with two serines and a phenylalanine of FmlH. Together, these additional interactions confer almost a 20-fold improvement in activity relative to the former lead compound 1, resulting in an IC50 of 34 nM. Interestingly, this structure is very different than that of 1, as the meta- carboxylate group of the B-ring, instead of making interactions with loop 1, is making interactions with the R142 and K132 with the acetamide group of the sugar ring. From our SAR analysis, we discovered that reverse sulfonamides like 50 are ideally suited for interactions in the pocket formed by D45, S2, and S10, while the nitro group as in 29 and 30 is prefers to reside in the pocket formed by R142 and K132. This key information will be critical in the further optimization of this series of compounds where both pockets can be exploited to improved galactoside potency. Another aspect of future work will be to assess the selectivity of these compounds toward other Gal and GalNAc recognizing lectins including PapG and mammalian lectins as well. However, because of the extreme structural differences and receptor specificities among these proteins, we do not anticipate significant binding of our compounds to these other lectins.

An evaluation of the metabolic stability and pharmacokinetic properties of several lead compounds has shown relatively good solubility and stability in blood plasma and liver microsomes as well as simulated gut and intestinal fluids. Cyclopropyl sulfonamide GalNAc 86, while not the most potent compound, appears to have the best PK profile in rats with a good half-life and moderate clearance. Further, compound 84 shows an excellent PK profile in mice with compound exposure well above the ELISA IC50 for 6 h. However, this and other compounds tested still show only <1% oral bioavailability in the rat. Our efforts are now are directed at further lead optimization in identifying new compounds with longer half-life, higher renal clearance to the urine, and oral permeability in the gut prior to conducting additional animal studies of UTI.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials and Methods.

Starting materials, reagents, and solvents were purchased from commercial vendors unless otherwise noted. In general, anhydrous solvents are used for carrying out all reactions. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were measured on a Varian 400 and 100 MHz NMR spectrometers. The chemical shifts were reported as δ ppm relative to TMS using residual solvent peak as the reference unless otherwise noted. The following abbreviations were used to express the peak multiplicities: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet, br = broad. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was carried out on GILSON GX-281 using Waters C18 5 μM, 4.6 mm × 50 mm and Waters Prep C18 5 μM, 19 mm × 150 mm reverse phase columns, eluted with a gradient system of 5:95 to 95:5 acetonitrile:water with a buffer consisting of 0.05–0.1% TFA. Mass spectrometry (MS) was performed on HPLC/ MSD using a gradient system of 5:95 to 95:5 acetonitrile:water with a buffer consisting of 0.05–0.1% TFA on a C18 or C8 reversed phased column and electrospray ionization (ESI) for detection. All reactions were monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC) carried out on either Merck silica gel plates (0.25 mm thick, 60F254) and visualized by using UV (254 nm) or dyes such as 5% H2SO4 in ethanol. Silica gel chromatography was carried out on a Teledyne ISCO CombiFlash purification system using prepacked silica gel columns (4–80 g sizes). All compounds used for biological assays are greater than 95% purity based on NMR and HPLC by absorbance at 220 and 254 nm wavelengths.

General Procedures.

Glycosylation Reactions.

Method A.

Synthesis of (2R,3R,4R,5R,6S)-5-acetamido-2-(acetoxymethyl)-6-(2- bromophenoxy)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3,4-diyl diacetate (4). 1N aqueous NaOH solution (1 mL) was added into a solution of 2-acetamido-3,4,6,-tri-O-acetyl-1-chloro-1,2-dideoxy-α-D galactopyranose 226 (100 mg, 0.273 mmol), tetrabutylammonium bromide (88 mg, 0.273 mmol), and 2-bromophenol (79 mg, 0.546 mmol) in dichloro- methane (2 mL) at room temperature. The reaction solution was stirred at the same temperature until the TLC indicates complete disappearance of chloride. Dilute the reaction mass with dichloro- methane (10 mL) and washed with water followed by brine. The organic layer was collected, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated undervacuo.The resulting residue was purified by silica gel chromatography with hexane/ethyl acetate (2:3) combinations as eluent, giving rise to the compound 4 and followed the same procedure for compounds 54–61 (analytical data in the Supporting Information).

Method B.

(2R,3S,4S,5R,6S)-2-(Acetoxymethyl)-6-(2- bromophenoxy) tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3,4,5-triyl triacetate (5). 1N aqueous NaOH solution (1 mL) was added into a solution of (2R,3S,4S,5R,6S)-2-(acetoxymethyl)-6-bromotetrahydro-2H-pyran- 3,4,5-triyl triacetate 3 (200 mg, 0.487 mmol), benzyltriethylammo- nium chloride (111 mg, 0.0.487 mmol), and 2-bromophenol (79 mg, 0.975 mmol) in chloroform (2 mL) at room temperature. The reaction solution was stirred at 60 °C temperature until the TLC indicates complete disappearance of starting material. The reaction solution was cooled and diluted with the dichloromethane (10 mL) and washed with water followed by brine. The organic layer was collected, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under vacuo. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel chromatography with hexane/ethyl acetate combinations as eluent, giving rise to the desired compound 5 (analytical data in the Supporting Information).

Method C.

Procedure 1:

Synthesis of (2R,3R,4R,5R,6S)-2(acetoxymethyl)-5-amino-6-(2-bromo-3-methylphenoxy)tetrahydro- 2H-pyran-3,4-diyl diacetate (62). The solution of 3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-2- amino-2-deoxy-α-D-galactopyranosyl bromide-HBr, 5229 (550 mg, 1.363 mmol), and sodium 2-bromo-3-methyl phenol 5330 (570 mg, 2.726 mmol) in acetonitrile (40 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the esidue was diluted with DCM (50 mL) and washed with satd NaHCO3 and brine. The organic layer was collected, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under vacuo, and the resulting residue was purified by silica gel chromatography with hexane/ethyl acetate (2:3) provides the compound 62 (analytical data in the Supporting Information).

Procedure 2:

Synthesis of (2R,3R,4R,5R,6S)-2-(acetoxymethyl)-6- (2-bromo-3-methylphenoxy)-5-(methylsulfonamido)tetrahydro-2H- pyran-3,4-diyl diacetate (63). Trifluoroacetic anhydride (0.22 mL, 1.581 mmol) was added into a solution of (2R,3R,4R,5R,6S)-2(acetoxymethyl)-5-amino-6-(2-bromo-3-methylphenoxy)tetrahydro- 2H-pyran-3,4-diyl diacetate 62 (250 mg, 0.527 mmol) and triethyl- amine (0.22 mL, 1.581 mmol) in dichloromethane (1 mL), and the solution was stirred at room temperature for 15 h. The reaction mass was diluted with dichloromethane (10 mL) and washed with satd NaHCO3 (5 mL) followed by brine (5 mL). The organic layer was collected, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under vacuo. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel chromatography with hexane/ethyl acetate (2:3) combinations as eluent, giving rise to the compound 63 (analytical data in the Supporting Information).

Procedure 3:

Synthesis of (2R,3R,4R,5R,6S)-2-(acetoxymethyl)-6-(2-bromo-3-methylphenoxy)-5 (methylsulfonamido)tetrahydro-2H- pyran-3,4-diyl diacetate (64). Methane sulfonyl chloride (119 mg, 1.038 mmol) was added into a solution of (2R,3R,4R,5R,6S)-2(acetoxymethyl)-5-amino-6-(2-bromo-3-methylphenoxy)tetrahydro- 2H-pyran-3,4-diyl diacetate 62 (246 mg, 0.519 mmol) and triethyl- amine (0.22 mL, 1.556 mmol) in dichloromethane (1 mL), and the solution was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The reaction mass was diluted with dichloromethane (10 mL) and washed with satd NaHCO3 (5 mL) followed by brine (5 mL). The organic layer was collected, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under vacuo. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel chromatography with hexane/ethyl acetate (2:3) combinations as eluent, giving rise to the compound 64 (analytical data in the Supporting Information).

Method D:

Suzuki Reactions.

Procedure 1:

Under nitrogen atmosphere charge, (2R,3R,4R,5R,6S)-5-acetamido-2-(acetoxymethyl)-6-(2-bromophenoxy) tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3,4-diyl diacetate (100 mg, 0.199 mmol), 3-(N-methyl amino carbonyl) phenyl boronic acid (78 mg, 0.298 mmo l), Pd(PPh3)4 (23 mg, 0.0199 mmol), and cesium carbonate (211 mg, 0.597 mmol) in reaction vial and added nitrogen gas bubbled in a 1,4-dioxane/water mixture (5:1, 3.6 mL) was added, and the reaction solution was heated to 80 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at 80 °C until TLC indicated complete disappearance of staring material (1 h). The reaction solution was cooled to RT and diluted with the dichloromethane (10 mL) and washed with water followed by brine. The organic layer was collected, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under vacuo.The resulting residue was purified by column chromatography with hexane/ethyl acetate (1:3) combinations as eluent, giving rise to the desired products 6–28, 65−72, and 75–77 (analytical data in the Supporting Information).Synthesis of compounds 73–74.

Procedure 2:

Synthesis of (2R,3R,4R,5R,6S)-5-acetamido-2-(ace- toxymethyl)-6-((3’-(cyclopropanesulfonamido)-6-methyl-[1,1 ‘-bi- phenyl]-2-yl)oxy)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3,4-diyl diacetate (73). Cyclo- propanesulfonyl chloride (54 mg, 0.189 mmol) was added into a solution of amine 72 (100 mg, 0.378 mmol) and triethyl amine (0.08 mL, 0.567 mmol) in DCM (2.5 mL) at room temperature, and the solution was stirred for 2 h. The solution was diluted with the dichloromethane (10 mL) and washed with water followed by brine. The organic layer was collected, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under vacuo. The resulting residue was purified by column chromatography with hexane/ethyl acetate (3:2), giving rise to the desired products 73 (analytical data in the Supporting Information).

Procedure 3:

Synthesis of (2R,3R,4R,5R,6S)-5-acetamido-2-(ace- toxymethyl)-6-((3’-((N,N-dimethylsulfamoyl)amino)-6-methyl-[1,1’- biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3,4-diyl diacetate (74). N,N- Dimethylsulfonyl chloride (54 mg, 0.189 mmol) was added into a solution of amine 72 (100 mg, 0.378 mmol) and triethylamine (0.08 mL, 0.567 mmol) in DMF (2.5 mL) mixed I and stirred under microwaves at 80 °C for 2 h. The reaction solution was cooled to RT and diluted with the dichloromethane (10 mL) and washed with water followed by brine. The organic layer was collected, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under vacuo. The resulting residue was purified by column chromatography with hexane/ethyl acetate (4:1) combinations as eluent, giving rise to the desired products 74 (analytical data in the Supporting Information).

Method E.

General Procedure for Compounds for 29–51 and 78–90

Procedure 1:

Synthesis of compounds (29). NaOH (27 mg, 0.66 mmol) was added into a solution of compound 6 (110 mg, 0.066 mmol) in methanol-water (1:1, 5 mL) at room temperature, stirred (15 h) until the TLC indicated complete disappearance of the staring material. The reaction solution was acidified pH~2 with 3N aqueous HCl and the product was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 10 mL). The organic layers were combined and washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The resulting residue was subjected for HPLC purification provided compound 29 and followed the same procedure for compounds30,31, and82.

Procedure 2:

An excess amount of 33% wt methylamine in absolute ethanol solution (5 mL) was added into (2R,3R,4R,5R,6S)-5- acetamido-2-(acetoxymethyl)-6-(quinolin-8-yloxy)tetrahydro-2H- pyran-3,4-diyl diacetate (50 mg, 0.105 mmol). The reaction solution was stirred at the same temperature (0.5–1 h) until TLC indicated complete disappearance of staring material. Complete evaporation of the solvent provides the desired product compound 32, which was subjected for HPLC purification and followed the same procedure for compounds 33–51, 78–81, and 83–90.

Experimental Protocols and Analytical Data of Final Compounds.

2’-(((2S,3S/4R/5R)-3-Acetamido-4,5-dihydroxy-6- (hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-5-nitro-[1, 1’-bi- phenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (29). Followed method E (procedure 1). White solid, 30 mg in 98% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 8.75 (s, 1H), 8.54 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.41 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.47–7.35 (m, 4H), 7.22–7.14 (m, 1H),5.08 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.03 (t, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 3.91–3.74 (m, 3H), 3.73–3.60 (m, 2H), 1.58 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 173.67, 167.67, 156.07, 149.69, 141.81, 137.16, 133.74, 131.65, 131.54, 129.77, 124.17, 123.83, 117.13, 111.59, 101.67, 77.45, 73.24, 69.78, 62.63, 54.21, 22.69. LCMS (ESI): C21H22N2O10, found [M + Na]+ 485.2.

5-Nitro-2’-(((2S,3R,4S,5R,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)- tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (30). Followed method E (procedure 1). White solid, 62 mg in 88% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 8.73 (s, 2 H), 8.58 (s, 1 H), 7.46–7.37 (m, 4 H), 7.21–7.15 (m, 1 H), 5.01 (d,J = 7.4 Hz, 1 h), 3.89 (d,J = 3.5 Hz, 1 H), 3.83–3.74 (m, 2 H), 3.72–3.66 (m, 2 h), 3.56 (dd,J = 9.6, 3.3 Hz, 1 H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 167.88, 156.03, 149.75, 142.10, 137.57, 133.60, 131.57, 129.73, 124.13, 123.66, 117.52, 103.33, 77.27, 75.31, 72.33, 70.3562.51. LCMS (ESI): C19H19NO10, found [M + Na]+ 444.3.

2’-(((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-3-Acetamido-4,5-dihydroxy-6 (hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-6-methoxy-[1,1’- biphenyl]-3-carboxylic Acid (31). Followed method E (procedure 1). White solid, 49 mg in 65% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 8.03 (dd, J = 2.0, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.36–7.29 (m, 2H), 7.15 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.10–7.03 (m, 2H), 4.95 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 3.96 (dd, J = 8.8, 10.4 Hz, 1H), 3.88–3.83 (m, 1H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 3.80–3.73 (m, 1H), 3.67–3.62 (m, 1H), 3.58 (dd, J = 3.1,10.6 Hz, 1H), 1.62 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 173.77, 170.06, 162.78, 156.91, 134.12, 132.47, 132.33, 130.16, 129.56, 129.31, 123.58, 123.31, 116.78, 112.06, 111.59, 101.61, 77.29, 73.49, 69.80, 62.62, 56.50, 54.20, 22.87. LCMS (ESI): C22H25NO9, found [M + Na]+ 470.3.

N-((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-4,5-Dihydroxy-2-((3’-hydroxy-[1,1’ biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)-6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl)- acetamide (32). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 30 mg in 70% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.36–7.25 (m, 3 H), 7.23–7.10 (m, 2H), 7.09–6.83 (m, 4H), 5.06 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 4.11 (dd, J = 10.4, 8.8 Hz, 1H), 3.88 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 1H), 3.86–3.74 (m, 2H), 3.72–3.60 (m, 2H), 1.73 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 174.31, 158.05, 156.13, 140.97, 132.87, 131.78,129.79, 123.74, 122.35, 117.86, 117.09, 115.08, 101.44, 77.35, 73.63, 69.81, 62.63, 54.36, 22.96. LCMS (ESI): C20H23NO7, found [M + Na]+ 412.3.

2’-(((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-3-Acetamido-4,5-dihydroxy-6- (hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-yl methanesulfonate (33). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 30 mg in 94% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.51–7.46 (m, 2H), 7.38–7.32 (m, 2H), 7.32–7.27 (m, 1H), 7.16–7.10, (m, 1H), 5.15 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.05 (dd, J = 8.4, 10.8 Hz, 1H), 3.89 (d, J = 3.3 Hz, 1H), 3.84–3.75 (m, 2H), 3.73–3.66 (m, 2H), 3.29 (s, 3H), 1.71 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 173.98, 156.04, 150.72, 141.82, 131.81, 131.30, 130.72, 129.89, 124.60, 124.02, 121.79, 117.10, 101.35, 77.43, 73.27, 69.79, 62.61, 54.47, 37.77, 22.96. LCMS (ESI): C21H25NO9S, found [M + Na]+ 490.3.

N-((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-4,5-Dihydroxy-2-((5’-hydroxy-2’ methoxy- [1,1’-biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)-6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl)acetamide (34). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 21 mg in 91% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.14 (dd, J = 7.4, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 6.86 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H),6.73, (dd, J = 8.8, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 6.60 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 1H), 4.95 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.00 (dd, J = 10.6, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 3.86 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H),3.84−3.80 (m, 1H), 3.79–3.74 (m, 1H), 3.66 (s, 3H), 3.64–3.61 (m, 1H), 3.61–3.56 (m, 2H), 1.73 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 174.15, 156.75, 152.19, 151.93, 132.55, 130.44, 129.68, 123.21, 119.49, 117.10, 115.98, 114.77, 101.70, 77.25, 73.62,69.80, 62.61, 57.44, 54.32, 23.02. LCMS (ESI): C21H25NO8, found [M + Na]+ 442.3.

2’-(((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-3-Acetamido-4,5-dihydroxy-6 (hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-6-methoxy-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-yl Methanesulfonate (35). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 13 mg in 82% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.34–7.25 (m, 3H), 7.20 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 7.10–7.02 (m, 2H), 5.01 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.01–3.93 (m, 1h), 3.89–3.83 (m, 1h), 3.83–3.79 (m, 1H), 3.74, (s, 1H), 3.64 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 3.23 (s, 3H), 1.72 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 173.87, 156.47, 143.93, 132.69, 128.77 126.45, 123.27, 116.95, 113.58, 101.39, 77.30, 73.34, 69.75, 69.59, 56.79, 54.31, 37.38, 23.05. LCMS (ESI): C22H27NO10S, found [M + Na]+ 520.2.

N-((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-2-((3 ‘-Fluoro-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)-4,5- dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl)acetamide (36). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 32 mg in 85% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.41–7.24 (m, 5H), 7.20 (dd, J = 10.4, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.14–7.07 (m, 1H), 7.07–7.00 (m, 1H), 5.6, (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.19–4.10 (m, 1H), 3.89 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 1H), 3.87–3.75 (m, 2H), 3.72–3.67 (m, 1H), 3.61 (dd, J = 11.0, 3.1 Hz, 1H), 1.72 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 173.95, 165.19, 162.76, 156.03, 141.98, 131.78, 131.54, 130.82, 130.74, 130.47, 126.70, 126.67, 123.85, 117.70, 117.48, 116.99, 114.82, 114.61, 101.42, 77.41, 73.74, 69.81, 62.62, 54.12, 22.83. LCMS (ESI): C20H22FNO6, found [M + Na]+ 414.3.

N-((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-4,5-Dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-2-((3’-me-thoxy-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl)- acetamide (37). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 20 mg in 87% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.39–7.34 (m, 1H), 7.33–7.22 (m, 4H), 7.12–7.00 (m, 3H), 6.86 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 5.03 (d, J =8.2 Hz, 1H),4.12 (t, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H), 3.91–3.85 (m, 1H), 3.83 (s, 3H), 3.81–3.74 (m, 1H), 3.71–3.64 (m, 1H), 3.60 (dd, J = 10.6, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 2.55 (s, 1H), 1.65 (s, 3h). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 174.07, 160.81, 156.24, 141.06, 132.95, 131.84, 129.96, 123.85, 123.23, 117.29, 116.47, 113.80, 101.85, 77.40, 73.79, 69.82, 62.64, 55.83, 54.25, 22.80. LCMS (ESI): C21H25NO7, found [M + Na]+ 426.3.

N-((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-4,5-Dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-2-((3’-nitro-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl)acetamide (38). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 35 mg in 91% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 8.33 (s, 1H), 8.19 (d, J = 8.2, Hz, 1H), 7.87 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.41–7.35 (m, 3H), 7.18–7.13 (m, 1H), 5.07 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1h), 4.14–4.8, (m, 1H), 3.89 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 3.87–3.75 (m, 3h), 3.73–3.67 (m, 1H), 3.61 (dd, J = 10.6, 3.1 Hz, 1H), 2.55 (s, 1H), 1.63 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 173.74, 156.05, 149.62, 141.30, 137.07, 131.66, 131.20, 130.38, 125.60, 124.06, 122.87, 117.1, 101.51, 77.43, 73.50, 69.77, 62.62, 54.04, 22.77. LCMS (ESI): C20H22N2O8, found [M + Na]+ 441.3.

N-((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-2-((3’-Cyano-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)-4,5-dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl)acetamide. (39).Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 16 mg in 84% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.82–7.77 (m, 2H), 7.67 (d, J = 9.00 Hz, 1H), 7.59–7.53 (m, 1H), 7.40–7.31 (m, 3H), 7.17–7.10 (m, 1H), 5.07 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.18–4.10 (m, 1H), 3.90 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 1H), 3.87–3.74 (m, 2H), 3.73–3.67 (m, 1H), 3.61 (dd, J =2.5, 10.8 Hz, 1H), 1.70 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 173.77, 155.97, 141.05, 135.62, 134.28, 131.72, 131.03, 130.36, 123.99, 120.08, 116.88, 113.37, 101.38, 77.42, 73.58, 69.77, 62.61, 54.1, 22.87. LCMS (ESI): C21H22N2O6, found [M + Na]+ 421.3.

N-((2S,3R,4R/5R/6R)-4/5-Dihydro xy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-2-((3’-(tri-fluoromethyl)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl) acetamide (40). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 14 mg in 86% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) S ppm 7.78 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (s, 1H), 7.63–7.53 (m, 2H), 7.39–7.36 (m, 2H),7.36–7.30 (m, 1H), 7.17–7.11 (m, 1H), 5.07 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1h), 4.11, (dd, J = 10.4, 8.8 Hz, 1H), 3.89 (br s, 1H), 3.86–3.75 (m, 2h), 3.73–3.66 (m, 1H), 3.61 (dd, J = 10.8, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 1.63 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 173.39, 156.11, 140.70, 135.02, 131.74, 131.33, 130.81, 129.92, 126.95, 124.75, 117.02, 101.53, 77.44, 73.72, 69.78, 62.62, 54.13, 22.73. LCMS (ESi): C21H22F3NO6, found [M + Na]+ 464.3.

N-((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-4,5-Dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-2-((3’- (methylsulfonyl)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3- yl)acetamide (41). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 14 mg in 60% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 8.10 (s, 1H), 7.90 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.69–7.62 (m, 1H), 7.42–7.34 (m, 3H), 7.18–7.12 (m, 1H), 5.14 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.06 (dd, J = 10.6, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 3.89 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 1H), 3.87–3.74, (m, 3H), 3.71–3.63 (m, 2H), 3.24 (s, 2H), 1.68 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 173.81, 156.05, 141.91, 141.01, 136.5, 131.77, 131.06, 130.44, 129.69, 126.80, 124.10, 116.95, 101.46, 77.44, 73.41, 69.77, 62.61, 54.27, 44.65, 22.93. LCMS (ESI): C21H25NO8S, found [M + Na]+ 474.3.

N-((2S,3R,4R/5R/6R)-4/5-Dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-2-((3’-(hy- droxymethyl)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl)- acetamide (42). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 33 mg in 87% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.53 (s, 1H), 7.40–7.27 (m, 6H), 7.12–7.06 (m, 1H), 4.97 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1h), 4.63, (s, 2H), 4.18 (dd, J =8.6, 10.6 Hz, 1H), 3.88 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1h), 3.86–3.82 (m, 1H), 3.81–3.76 (m, 1H), 3.71–3.66 (m, 1H), 3.59 (dd, J = 3.1, 10.6 Hz, 1H), 1.54 (s, 3h). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 174.24, 156.32, 142.22, 132.65, 131.80, 130.32,129.99, 129.65, 129.33, 127.18, 123.90, 117.10, 101.91, 77.42, 73.47, 69.82, 65.84, 62.68, 54.09, 22.70. LCMS (ESI): C21H25NO7, found [M + Na]+ 426.3.

N-(2’-(((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-3-Acetamido-4,5-dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3- yl)acetamide (43). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 38 mg in 96% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) S ppm 7.63 (t, J =1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.36–7.28 (m, 5H), 7.23 (s, 1H), 7.09 (td, J = 7.2, 1.6 Hz, 1h), 5.11 (d, J =8.6 Hz, 1H),4.13 (dd, J = 10.6, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 3.89 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 1H), 3.85–3.74 (m, 2H), 3.70–3.65 (m, 2H), 2.16 (s, 3H),1.70 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 174.17, 171.86, 155.99, 140.15, 139.38, 132.16, 131.8, 130.08, 129.58, 126.81, 132.83, 123.23, 120.35, 116.84, 1.1.5, 77.32, 73.37, 69.80, 62.63, 54.32, 24.01, 23.02. LCMS (ESI): C22H26N2O7, found [M + Na]+ 453.3.

N-(2’-(((2S,3S,4R,5R)-3-Acetamido-4,5-dihydroxy-6 (hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-yl)-2,2,2-trifluoroacetamide (44). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 20 mg in 63% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.70–7.65 (m, 2H), 7.44–7.38 (m, 1H), 7.38–7.31 (m, 4H), 7.13–7.08 (m, 1H), 5.10 (d, J = 8.2 Hz,1H), 4.18 (dd, J = 8.6, 10.6 Hz, 1H), 3.89 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 1H), 3.85–3.73 (m, 2H), 3.72–3.61 (m, 2H), 1.72 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 174.09, 155.88, 140.47, 137.15, 131.80, 130.33, 129.85, 128.45, 124.18, 123.80, 121.26, 116.52, 100.88, 77.31, 73.38, 69.76, 62.59, 54.06, 22.94. LCMS (ESI): C22H23F3N2O7, found [M + Na]+ 507.4.

Methyl(2’-(((2S,3R/4R/5R,6R)-3-Acetamido-4/5-dihydroxy-6- (hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3 yl)carbamate (45). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 34 mg in 87% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.53 (br s, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.35–7.27 (m, 4H), 7.16 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.11–7.06 (m, 1H), 5.11 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 4.09 (dd, J =8.6, 10.6 Hz, 1H), 3.88 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 1H), 3.85–3.77 (m, 2H), 3.74 (s, 3H), 3.68 (dd, J =3.1, 10.6 Hz, 2H), 1.70 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 174.17, 156.01, 140.27, 132.46, 131.85, 130.00, 129.57, 125.88, 123.39, 116.89, 101.08, 77.32, 73.34, 69.83, 62.61, 54.42, 52.67, 22.96. LCMS (ESI): C22H26N2O8, found [M + Na]+, 469.2

2’-(((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-3-Acetamido-4,5-dihydroxy-6- (hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-N,N-dimethyl-[1,1’- biphenyl]-3-carboxamide (46). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 29 mg in 86% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.60–7.55 (m, 2H), 7.47 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.39–7.29 (m, 4H), 7.14–7.08 (m, 1H), 5.17 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.06–3.98 (m, 1H), 3.89 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 3.84–3.73 (m, 2H), 3.73–3.65 (m, 2H), 3.12 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 6H), 1.74 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 173.94, 156.03, 140.15, 136.96, 132.31, 131.84, 130.44, 129.66, 129.41, 126.62, 123.90, 116.88, 101.05, 77.35, 73.42, 69.77, 62.63, 54.49, 40.58, 35.88, 23.01. LCMS (ESI): C23H28O7, found [M + Na]+ 445.3.

2’-(((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-3-Acetamido-4,5-dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-N-methyl-[1,1’-bi- phenyl]-3-carboxamide (47). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 62 mg in 73% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.93 (d, J = 3.91 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (t, J = 5.09 Hz, 1h), 7.65 (t, J =5.87 Hz, 1H), 7.50–7.44 (m, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 4.70 Hz, 3H), 7.16–7.09 (m, 1H), 5.13–5.07 (m, 1H),4.17– 4.10 (m, 1H), 3.93–3.74 (m, 3H), 3.73–3.64 (m, 2H), 2.96 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 3H),1.64 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 174.03, 156.12, 140.03, 135.80, 133.90, 131.92, 130.44, 129.54, 126.83, 123.96, 116.96, 101.53, 77.41, 73.27, 69.79, 62.64, 54.23, 27.12, 22.82. LCMS (ESI): C22H26O7, found [M + Na]+ 453.3.

2’-(((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-3-Acetamido-4,5-dihydroxy-6 (hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3- carboxamide (48). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 13 mg in 85% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.99 (s, 1H), 7.79 (d, J = 7.83 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 7.83 Hz, 1H), 7.50–7.45 (m, 1H), 7.39–7.31 (m, 4H), 7.12 (t, J =6.9 Hz, 1H), 5.11 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.10 (dd, J = 8.8, 10.4 Hz, 1H), 3.89 (d, J = 3.13 Hz, 1H), 3.86–3.75 (m, 3H), 3.72–3.64 (m, 3H), 1.64 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 174.01, 172.99, 156.13, 140.02, 135.11, 134.37, 131.91, 130.44, 129.96, 129.41, 127.24, 123.97, 117.00,101.50, 77.41, 73.26, 62.63, 54.32, 22.82. LCMS (ESI): C21H24O7, found [M + Na]+ 439.3.

N-((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-4,5-Dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-2-((3’- (methylsulfonamido)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl)acetamide (49). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 34 g in 96% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.40 (s, 1H), 7.36 (s, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 3H), 7.29–7.22 (m, 2H), 7.12–7.07 (m, 1H), 5.12 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 4.11 (dd, J = 8.6, 10.6 Hz, 1H), 3.89 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 1H), 3.85–3.73 (m, 2H), 3.7–13.63 (m, 2H), 3.03 (s, 3H), 1.73 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm174.06, 155.99, 140.93, 139.06, 131.97, 130.27,127.25, 123.82, 120.68, 116.69, 101.09, 77.35, 73.46, 62.60, 54.24, 39.58, 23.04. LCMS (ESI): C21H26O8S, found [M + Na]+ 489.2.

N-((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-4,5-Dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-2-((3’-((trifl uoromethyl)sulfonamido)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl)acetamide (50). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 25 mg in 63% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.70–7.65 (m, 2H), 7.44–7.38 ( m, 1H),7.38–7.31 (m, 4H), 7.13–7.08 (m, 1H), 5.10 (d, J = 8.2 Hz,1H), 4.18 (dd, J = 8.6, 10.6 Hz, 1H), 3.89 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 1H), 3.85–3.73 (m, 2H), 3.72–3.61 (m, 2H), 1.72 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 174.09, 155.88, 140.47, 137.15, 131.80, 130.33, 129.85, 128.45, 124.18, 123.80, 121.26, 116.52, 100.88, 77.31, 73.38, 69.76, 62.59, 54.06, 22.94. LCMS (ESI): C21H23F3O8S, found [M + Na]+ 543.2.

N-(2’-(((2S,3R,4S,5R,6R)-3,4,5-Trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-yl)-methanesulfonamide (51). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 33 mg in 93% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.54 (s, 1 H), 7.39–7.27 (m, 5 H), 7.26–7.19 (m, 1 H), 7.12–7.06 (m, 1 H), 5.06 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H),3.89 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 1 H), 3.77–3.72 (m, 2 H), 3.72–3.66 (m, 2 H), 3.57 (dd, J = 9.6, 3.3 Hz, 1 H), 3.01 (s, 3 H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 153.37, 141.9, 138.77, 131.72, 129.98, 127.19, 123.71, 123.36, 120.63, 116.29, 101.96, 76.91, 75.02, 72.17, 70.15, 62.2739.16. LCMS (ESI): C19H23NO8S, C19H23NO8S, found [M + Na]+ 448.2.

N-((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-4,5-Dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-2-((3’- (methylsulfonamido)-6-nitro-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl)acetamide (78). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 30 mg in 94% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.63–7.58 (m, 1H), 7.57–7.49 (m, 3H), 7.39–7.33 (m, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (s, 1H), 6.98(d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1h), 5.11 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 3.97 (t, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 3.87 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.85–3.73 (m, 2H), 3.73–3.67 (m, 1H), 3.63(dd, J = 2.4, 10.6 Hz, 1H), 3.00 (s, 3H), 1.78 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 173.81, 156.82, 152.49, 139.54, 135.32, 130.82, 130.48, 126.29, 121.27, 120.33, 118.20, 101.19, 77.60, 73.35, 69.74, 62.63, 53.92, 39.34, 23.16. LCMS (ESI): C21H25N3O10S, found [M + H]+ 512.3.

N-((2S,3S,4R,5R)-2-((6-Cyano-3’-(methylsulfonamido)-[1,1’-bi- phenyl]-2-yl)oxy)-4,5-dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)tetra’hydro-2H- pyran-3-yl)acetamide (79). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 25 mg in 88% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.64 (dd, J = 2.9, 6.46 Hz, 1H), 7.53–7.47 (m, 2H), 7.4–5-7.39 (m, 1H), 7.34–7.26 (m, 2H), 7.14 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 5.09 (d, J =8.6 Hz, 1H), 4.03–3.96 (m, 1H), 3.87 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 3.83–3.73 (m, 2H), 3.72–3.66 (m, 1H), 3.65–3.60 (m,1H), 3.05 (s, 3H), 1.78 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 173.83, 156.43, 139.53, 136.87, 135.97, 131.11, 130.50, 128.08, 127.49, 121.62, 119.11, 114.82, 101.08, 77.57, 73.29, 69.74, 62.63, 53.95, 39.60, 23.11. LCMS (ESI): C22H25N3O8S, found [M + Na]+ 514.2.

N-((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-2-((6-Fluoro-3’-(methylsulfonamido)-[1,1’- biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)-4,5-dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl)acetamide (80). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 7 mg in 59% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.40–7.28 (m, 2H), 7.25 (br s, 2H), 7.14 (dd, J = 8.0, 12.3 Hz, 2H), 6.88 (t, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 5.10 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.00 (t, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 3.87 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.84–3.73 (m, 2H), 3.71–3.60 (m, 2h), 3.03 (s, 3H), 1.77 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 173.91, 139.12, 133.95, 130.61, 130.01, 128.28, 124.36, 121.10, 112.25, 110.79, 110.56, 101.05, 77.42, 73.40, 69.74, 62.59, 54.09, 39.50, 23.11. LCMS (ESI): C21H25FN2O8S, found [M + H]+ 485.3.

Benzyl6-(((2S,3S,4R,5R)-3-Acetamido-4,5-dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-3’-(methylsulfona- mido)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-carboxylate (81). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 37 mg in 90% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.52–7.45 (m, 1H), 7.45–7.40 (m, 2H), 7.30–7.23 (m, 3H), 7.18–7.10 (m, 2H), 7.06–7.00 (m, 2H), 6.94 (d, J =8.2 Hz, 1H), 5.06 (d, J =8.2 Hz, 1H), 5.00 (s, 2H), 4.01–3.93 (m, 1H), 3.85 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 3.84–3.71 (m, 2H), 3.70–3.64 (m,1H), 3.60 (dd, J = 3.1, 10.6 Hz, 1H), 2.90 (s, 3H), 1.76 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 170.06, 156.30, 139.07, 138.98, 134.93, 131.98, 130.13, 129.62, 129.30, 124.27, 123.41, 120.80, 119.40, 101.05, 77.43, 73.54, 69.75, 68.27, 62.62, 54.02, 39.46, 23.15, LCMS (ESI): C29H32N2O10S, found [M + H]+ 601.3.

6-(((2S,3S,4R,5R)-3-Acetamido-4,5-dihydroxy-6 (hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-3 ‘-(methylsulfona- mido)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-carboxylic Acid (82). Followed method E (procedure 1). White solid, 22 mg in 92% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm7.49–7.37 (m, 3H), 7.33–7.27 (m, 1H), 7.19–7.13 (m, 2H), 7.00 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 5.06 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 4.00–3.91 (m, 1H), 3.86 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 3.83–3.72 (m, 2h), 3.71–3.65 (m, 1H), 3.61 (dd, J = 3.1, 10.6 Hz, 1H), 2.99 (s, 3H),1.78 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 173.87, 171.76, 156.34, 139.18, 138.89, 135.62, 132.08, 129.79, 124.11, 120.69, 119.15, 101.9, 77.41, 73.55, 69.77, 62.63, 54.07, 39.29, 23.18. LCMS (ESI): C22H26N2O10S, found [M + H]+ 511.2.

N-((2S,3S,4R,5R)-4,5-Dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-2-((6-me- thoxy-3 ‘-(methylsulfonamido)-[1,1 ‘-biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl)acetamide (83). Followed method E (procedure 2)., White solid, 13 mg in 93% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.28 (q, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.18–7.14 (m, 2H), 7.04 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.77(d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 5.06 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 3.93 (dd, J = 8.6, 10.6 Hz, 1H), 3.86 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 1H), 3.82–3.73 (m, 2H), 3.71 (s, 3H), 3.68–3.59 (m, 2H), 3.02 (s, 3H), 1.78 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 173.90, 159.07, 156.88, 138.65, 136.71, 130.33, 129.54, 128.81, 124.94, 120.47,109.18, 106.85, 100.95, 77.27, 73.56, 69.75, 62.58, 56.49, 54.21, 39.35, 23.15, LCMS (ESI): C22H28N2O9S, found [M + Na] + 519.3.

N-((2S,3R/4R/5R,6R)-4/5-Dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-2-((6-methyl-3’-(methylsulfonamido)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl)acetamide (84). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 31 mg in 97% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.35 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.23–7.16 (m, 2H), 7.15–7.10 (m, 1H), 7.07 (s, 1h), 6.95 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H),5.01 (d, J =8.6 Hz, 1H), 3.94–3.71 (m, 4H), 3.68–3.56 (m, 2H), 3.01 (s, 3H), 2.5 (s, 3H), 1.81 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 171.92, 140.15, 138.68, 132.35, 130.18, 129.51, 125.15, 100.98, 77.21, 69.75, 62.58, 54.15, 39.46, 23.24, 20.79. LCMS (ESI): C22H28N2O8S, found [M + H] + 481.4.

N-((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-4,5-Dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-2-((1-(3 (methylsulfonamido)phenyl)naphthalen-2-yl)oxy)tetrahydro-2H- pyran-3-yl)acetamide (85). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 54 mg in 97% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.92–7.82 (m, 2H), 7.65–7.59 (m, 1H), 7.47–7.41 (m, 2H), 7.38–7.26 (m, 3H), 7.21 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 5.15 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 4.02–3.94 (m, 1H), 3.87 (br s, 1H), 3.84–3.76 (m, 2H), 3.73–3.58 (m, 2H), 3.07 (s, 3H), 1.80 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 173.36, 139.64, 138.87, 130.63, 130.41, 129.10, 128.02, 127.62, 126.97, 126.39, 125.34,124.61, 124.44, 120.75, 120.40, 118.19, 117.73, 101.57, 101.40, 39.59.23.52, LCMS (ESI): C25H28N2O8S, found [M + Na]+ 517.3.

N-((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-2-((3’-(Cyclopropanesulfonamido)-6-meth-yl-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)-4,5-dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl)acetamide (86). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 22 mg in 93% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.31–7.38 (m, 1H), 7.26–7.16 (m, 2H), 7.11 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 2H), 6.95 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 5.03 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 3.91–3.81 (m, 2H), 3.80–3.71 (m, 2H), 3.67–3.56 (m, 2H), 2.65–2.53 (m, 1H), 2.05 (s, 3H, 1.83 (s, 3H), 1.07–0.95 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 156.23, 139.99, 138.70, 132.40,128.98, 125.10, 124.87, 100.85, 77.18, 69.73, 62.60, 54.22, 30.52, 23.24, 20.81, 6.06. LCMS (ESI): C24H30N2O8S, found [M + Na] +529.3.

N-((2S,3S,4R,5R)-2-((3’-((N,N-Dimethylsulfamoyl)amino)-6-methyl-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)-4,5-dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl)acetamide (87). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 21 mg in 89% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 9.77 (br s, 1H), 7.56(d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.28–7.17 (m, 2H), 7.14 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.82 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 4.93 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 3.79–3.69 (m, 1H), 3.66 (br s, 1H), 3.57–3.47 (m, 3H), 3.47–3.40 (m, 1H), 2.70 (s, 6H), 1.99 (s, 3H), 1.74 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 171.99, 155.37, 135.52, 128.92, 128.12, 126.42,125.47, 118.37, 99.26, 99.08, 75.89, 72.05, 71.74, 68.16, 61.03, 52.29, 37.60, 21.68. LCMS (ESI): C23H31N3O8S, found [M + Na]+ 532.3.

N-((2S,3S,4R,5R)-4/5-Dihydro xy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-2-((6-methyl-3’-(methylsulfonamido)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl)-2,2,2-trifluoroacetimidic Acid (88). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 6 mg in 23% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 8.93 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (br s, 2H), 7.08–6.98 (m, 2H), 6.95 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.83 (br s, 1H), 5.11 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 4.05–3.95 (m, 1H), 3.87 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.83–3.72 (m, 2H), 3.66 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 2H),3.02 (br s, 3H), 2.04 (s, 3H) (Note: 13C NMR not provide due to due to insufficient quantity). LCMS (ESI): C22H25F3N2O8S, found [M + Na] + 557.3.

N-((2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-4,5-Dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-2-((6- methyl-3’-(methylsulfonamido)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl)methanesulfonamide (89). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 39 mg in 97% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.40–7.35 (m, 1H), 7.28–7.19 (m, 2H), 7.14 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H), 7.09–6.94 (m, 3H), 5.08 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 3.89 (br s, 1H), 3.73 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H), 3.64–3.60 (m, 1H), 3.55–3.50 (m, 1H), 3.48–3.37 (m, 1H), 2.59–2.39 (m, 3H), 2.08 (br s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 149.33, 130.37, 129.45, 125.22, 77.05, 69.81, 62.34, 57.85, 41.92, 39.63, 20.94. LCMS (ESI): C21H28N2O9S2, found [M + Na] + 539.3.

N-((2S,3S,4R,5R)-4,5-Dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-2-((3’-(meth-ylsulfonamido)-6-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-yl)oxy)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl)acetamide (90). Followed method E (procedure 2). White solid, 20 mg in 84% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm 7.57–7.48 (m, 2H), 7.46–7.41 (m, 1H), 7.37–7.30 (m, 1H), 7.27–7.21 (m, 1H), 7.21–7.14 (m, 1H), 7.10 (s, 3H), 6.98–6.89 (m, 1H), 5.06 (d, J = 8.0, 1H), 3.91–3.83 (m, 2H), 3.82–3.72 (m, 2H), 3.68 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 3.65–3.55 ( m, 1H), 2.99 (s, 3H), 1.83 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ ppm, 173.60, 157.18, 139.04, 137.11, 130.51, 129.72, 120.90, 120.39,120.30, 119.97, 100.84, 77.48, 73.64, 73.34, 69.76, 62.63, 53.89, 39.20, 39.13, 23.28. LCMS (ESI): C22H25F3N2O8S, found [M + H]+ 535.3.

FmlH Protein Expression and Purification.

FmlH protein used in crystallographic studies was expressed and purified as previously described. Briefly, protein was expressed in the periplasm of E. coli C600 cells containing pTRC99a encoding the first 182 amino acids of the CFT073 FmlH protein (corresponding to the signal sequence and lectin domain) and a C-terminal 6x-his tag. Periplasmic isolates were prepared as previously described and were washed over a cobalt affinity column (GoldBio) and eluted in 20 mM Tris 8.0 + 250 mM imidazole. Fractions containing protein of the expected molecular weight were then diluted 5-fold in 20 mM Tris 8.0 to a final concentration of 50 mM Imidazole, washed over an anion exchange column (GE Healthcare Mono Q) with 20 mM Tris 8.0, and eluted in 20 mM Tris 8.0 + 250 mM NaCl. Resulting fractions were pooled and dialyzed in 1 mM HEPES pH 7.5 + 50 mM NaCl and concentrated as needed for further study. Protein used in ELISA assays was biotinylated using anNHS-PEG4-Biotin and Biotinylation Kits (ThermoFisher).

ELISA Assay and Determination of IC50 Values.

Enzyme- linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were used to quantify the IC50 of different Gal and GalNAc compounds as previously described.12 Briefly, 1μg of bovine submaxillary mucin (Sigma) in 100μL of PBS were incubated with Immulon 4HBX 96-well plates overnight prior to treatment with 1 mU Arthrobacter ureafaciens sialidase for 1 h at 37 °C to remove terminal sialic acid sugars. Wells were then blocked with 200μL PBS + 1% BSA for 2 h at room temperature. Biotinylated FmlHLD was diluted to 20μg/mL in blocking buffer and incubated in the presence or absence of compounds serially diluted 2× down eight rows for 1 h at room temperature. Wells were washed three times with PBS 0.05% TWEEN-20 then incubated with 100μL of streptavidin-HRP conjugate (BD Biosciences; 1:2000 dilution in blocking buffer) for one hour. After three additional PBS + 0.05% TWEEN washes, plates were developed with 100μL of tetramethylbenzidine (BD Biosciences) substrate and quenched with 50μL of 1 M H2SO4. Total bound portion concentration was measured by the absorbance at 450 nm. IC50s were determined using the Graphpad Prism software.

X-ray Crystallography Studies.

All protein solutions were generated by adding 10μL of 50 mM compound dissolved in 100% DMSO to FmlH in 10 mM HEPES pH 7.5 + 50 mM NaCl immediately before setting up drops for a final concentration of 9 mg/ mL FmlDLD, 5 mM compound, and 10% DMSO. Cocrystals of FmlH-90 were grown by mixing 1μL of protein solution with 1μL of mother liquor containing 0.7 M LiSO4 + 20% PEG 8000 on a glass coverslip over 1 mL of mother liquor. Thin, needle-like crystals appeared after approximately 72 h. Crystals were cryoprotected in 1 M LiSO4 + 20% PEG 8000 + 25% glycerol for 10 s before and flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen. Crystals of FmlH-29 were grown by mixing 1μL of protein solution (9 mM FmlHLD, 5 mM compound 29, 9 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 45 mM NaCl) with 1μL of 0.1 M Tris 8.0 + 0.8 M AmSO4 using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method. Square pyramidal crystals began appearing after approximately 24 h and continued to grow for up to 7 days. Crystals were harvested after 10 days, cryoprotected in a solution containing 0.1 M Tris 8.0, 0.8 M AmSO4, and 30% glycerol for 10 s, and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

To generate crystals of FmlH-30, drops containing 9 mg/mL FmlH, 2.5 mM 30, 10% DSMO, 0.1 M Tris 8.0, and 0.8 M AmSO4 were allowed to equilibrate over a 1 M well solution of 0.1 M Tris 8.0 + 0.8 M AmSO4 for 2 days. FmlH-29 cocrystals were then transferred the pre-equilibrated drops and allowed to soak for 48 h before cryoprotection in 0.1 M Tris 8.0, 0.8 M AmSO4, and 30% and flash- freezing in liquid nitrogen.

All data were collected on ALS Beamline 4.2.2 at an X-ray wavelength of 1.00 Å. Raw data were processed using XDS, Aimless, and Pointles.31,32 The phase problem was solved using Phaser-MR in the Phenix suite using the apo FmlHLD structure (PDBID: 6AOW) as a search model.33 Iterative rounds of Phenix. Refine, and Coot34 were used to refine the final model. Guided ligand replacement was performed using Phenix. Space group, collection, and refinement statistics for each cocrystal are listed in Supporting Information, Table S3.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for funding awarded by the NIDDK, R01DK10884.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- NaOH

sodium hydroxide

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- aq

aqueous

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- ACN

acetonitrile

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- TEA

triethyl amine

- nM

nanomolar

- MsCl

methanesulfonyl chloride

- °C

degrees Celsius

- NA

not applicable

- Å

Angstrom(s)

- SGF

simulated gastric fluid

- SIF

simulated intestinal fluid

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmed- chem.8b01561.

HPLC, MS, 1H, and 13C NMR spectra of all final tested compounds and intermediates as well as the detailed protocol and data for the rat and mouse pharmacokinetic studies performed by WuXi AppTec (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. (PDF)

Molecular formula strings (CSV)

Accession Codes

PDB IDs of X-ray structures/homology models: novel protein structures have been deposited into the PDB; FmlH-30, 6MAP; FmlH-29, 6MAQ; FmlH-90, 6MAW. Authors will release the atomic coordinates upon article publication. Homology modeling was performed using the apo FimHLD structure (PDB 6AOW) as a search model.

Notes

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): JWJ and SJH are co-founders and owners of Fimbrion Therapeutics company stock who are commercializing mannoside FimH antagonists as new drugs for UTIs.

REFERENCES

- (1).Adeyi OO; Baris E; Jonas OB; Irwin A; Berthe FCJ; Le Gall FG; Marquez PV; Nikolic IA; Plante CA; Schneidman M; Shriber DE; Thiebaud A Drug-resistant infections: a threat to our economic future. The World Bank, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Griebling TL Urologic diseases in America project: trends in resource use for urinary tract infections in women. J. Urol. 2005, 173, 1281–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Schappert SM; Rechtsteiner EA Ambulatory medical care utilization estimates for 2007. Vital Health Stat. 2011, 13, 1–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Shapiro DJ; Hicks LA; Pavia AT; Hersh AL Antibiotic prescribing for adults in ambulatory care in the USA, 2007–09. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 234–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Fridkin S; Baggs J; Fagan R; Magill S; Pollack LA; Malpiedi P; Slayton R; Khader K; Rubin MA; Jones M; Samore MH; Dumyati G; Dodds-Ashley E; Meek J; Yousey- Hindes K; Jernigan J; Shehab N; Herrera R; McDonald CL; Schneider A; Srinivasan A Vital signs: improving antibiotic use among hospitalized patients. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2014, 63, 194–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Flores-Mireles AL; Walker JN; Caparon M; Hultgren SJ Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 269–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Spaulding CN; Hultgren SJ Adhesive pili in UTI pathogenesis and drug development. Pathogens 2016, 5, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Waksman G; Hultgren SJ Structural biology of the chaperone-usher pathway of pilus biogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.2009, 7, 765–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Wurpel DJ; Beatson SA; Totsika M; Petty NK; Schembri MA Chaperone-usher fimbriae of Escherichia coli. PLoS One 2013, 8, No. e52835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Hung CS; Bouckaert J; Hung D; Pinkner J; Widberg C; DeFusco A; Auguste CG; Strouse R; Langermann S; Waksman G, Hultgren SJ Structural basis of tropism of Escherichia coli to the bladder during urinary tract infection. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 44, 903– 915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Conover MS; Ruer S; Taganna J; Kalas V; De Greve H; Pinkner JS; Dodson KW; Remaut H; Hultgren SJ Inflammation-induced adhesin-receptor interaction provides a fitness advantage to uropathogenic E. coli during chronic infection. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 20, 482–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Kalas V; Hibbing ME; Maddirala AR; Chugani R; Pinkner JS; Mydock-McGrane LK; Conover MS; Janetka JW; Hultgren SJ Structure-based discovery of glycomimetic FmlH ligands as inhibitors of bacterial adhesion during urinary tract infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U. S. A. 2018, 115, E2819–E2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Cusumano CK; Pinkner JS; Han Z; Greene SE; Ford BA; Crowley JR; Henderson JP; Janetka JW; Hultgren SJ Treatment and prevention of urinary tract infection with orally active FimH inhibitors. Sci. Transl Med. 2011, 3, 109ra–115.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Mydock-McGrane L; Cusumano Z; Han Z; Binkley J; Kostakioti M; Hannan T; Pinkner JS; Klein R; Kalas V; Crowley J; Rath NP; Hultgren SJ; Janetka JW Antivirulence C-mannosides as antibiotic-sparing, oral therapeutics for urinary tract infections. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 9390–9408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Jarvis C; Han Z; Kalas V; Klein R; Pinkner JS; Ford B; Binkley J; Cusumano CK; Cusumano Z; Mydock-McGrane L; Hultgren SJ; Janetka JW Antivirulence isoquinolone mannosides: Optimization of the biaryl aglycone for FimH lectin binding affinity and efficacy in the treatment of chronic UTI. ChemMedChem 2016,11,367–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Kleeb S; Pang L; Mayer K; Eris D; Sigl A; Preston RC; Zihlmann P; Sharpe T; Jakob RP; Abgottspon D; Hutter AS; Scharenberg M; Jiang X; Navarra G; Rabbani S; Smiesko M; Ludin N; Bezencon J; Schwardt O; Maier T; Ernst B FimH antagonists: Bioisosteres to improve the in vitro and in vivo PK/PD profile. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 2221–2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Jiang X; Abgottspon D; Kleeb S; Rabbani S; Scharenberg M; Wittwer M; Haug M; Schwardt O; Ernst B Antiadhesion therapy for urinary tract infections-a balanced PK/PD profile proved to be key for success. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 4700–4713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Abgottspon D; Ernst B In vivo evaluation of FimH antagonists - a novel class of antimicrobials for the treatment of urinary tract infection. Chimia 2012, 66, 166–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Mydock-McGrane LK; Cusumano ZT; Janetka JW Mannose-derived FimH antagonists: a promising anti-virulence therapeutic strategy for urinary tract infections and Crohn’s disease. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2016, 26, 175–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Mydock-McGrane LK; Hannan TJ; Janetka JW Rational design strategies for FimH antagonists: new drugs on the horizon for urinary tract infection and Crohn’s disease. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2017, 12, 711–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Cao Z; Qu Y; Zhou J; Liu W; Yao G Stereoselective synthesis of quercetin 3-O-glycosides of 2-amino-2-deoxy-d-glucose under phase transfer catalytic conditions. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 2015, 34, 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Roy R; Tropper F Stereospecific synthesis of arylβ-d-N- acetylglucopyranosides by phase transfer catalysis. Synth. Commun. 1990, 20, 2097–2102. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Kleine HP; Weinberg DV; Kaufman RJ; Sidhu RS Phase-transfer-catalyzed synthesis of 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-galac- topyranosides. Carbohydr. Res. 1985, 142, 333–337. [Google Scholar]

- (24).De Bruyne CK; Wouters-Leysen J Synthesis of substituted phenylβ-d-galactopyranosides. Carbohydr. Res. 1971, 18, 124–126. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Greig IR; Macauley MS; Williams IH; Vocadlo DJ Probing synergy between two catalytic strategies in the glycoside hydrolase O-glcNAcase using multiple linear free energy relationships. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 13415–13422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Boutureira O; Bernardes GJL; Fernández-González M; Anthony DC; Davis BG Selenenylsulfide-linked homogeneous glycopeptides and glycoproteins: Synthesis of human “Hepatic Se Metabolite A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 1432–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Han Z; Pinkner JS; Ford B; Chorell E; Crowley JM; Cusumano CK; Campbell S; Henderson JP; Hultgren SJ; Janetka JW Lead optimization studies on FimH antagonists: Discovery of potent and orally bioavailable ortho-substituted biphenyl mannosides. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 3945–3959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Alteen MG; Oehler V; Nemčovičová I; Wilson IBH; Vocadlo DJ; Gloster TM Mechanism of human nucleocytoplas- mic hexosaminidase D. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 2735–2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Wolfrom ML; Cramp WA; Horton D 3,4,6-Tri-O-acetyl- 2-amino-2-deoxy-α-d-galactopyranosyl bromide hydrobromide1. J. Org. Chem. 1963, 28, 3231–3232. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Zhang M; Chen S; Weng Z Copper-mediated one-pot synthesis of 2,2-difluoro-1,3-benzoxathioles from o-bromophenols and trifluoromethanethiolate. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 481–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Kabsch W XDS. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Evans PR; Murshudov GN How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2013, 69, 1204–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Adams PD; Afonine PV; Bunkóczi G; Chen VB; Davis IW; Echols N; Headd JJ; Hung L-W; Kapral GJ; Grosse- Kunstleve RW; McCoy AJ; Moriarty NW; Oeffaer R; Read RJ; Richardson DC; Richardson JS; Terwilliger TC; Zwart PH PHENIX: A comprehensive python-based system for macro-molecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Emsley P; Lohkamp B; Scott WG; Cowtan K Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr.2010,66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.