Abstract

The active sites of hundreds of human α-ketoglutarate (αKG) and Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenases are exceedingly well preserved, which challenges the design of selective inhibitors. We identified a noncatalytic cysteine (Cys481 in KDM5A) near the active sites of KDM5 histone H3 lysine 4 demethylases, which is absent in other histone demethylase families, that could be explored for interaction with the cysteine-reactive electrophile acrylamide. We synthesized analogs of a thienopyridine-based inhibitor chemotype, namely, 2-((3-aminophenyl)(2-(piperidin-1-yl)ethoxy)methyl)thieno[3,2-b]-pyridine-7-carboxylic acid (N70) and a derivative containing a (dimethylamino)but-2-enamido)phenyl moiety (N71) designed to form a covalent interaction with Cys481. We characterized the inhibitory and binding activities against KDM5A and determined the cocrystal structures of the catalytic domain of KDM5A in complex with N70 and N71. Whereas the noncovalent inhibitor N70 displayed αKG-competitive inhibition that could be reversed after dialysis, inhibition by N71 was dependent on enzyme concentration and persisted even after dialysis, consistent with covalent modification.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Protein (histone) lysine methylation has been implicated in regulating a broad array of biological processes including epigenetic memory, genome stability, cell cycle, gene expression and nuclear architecture, and is often compromised in diseases.1,2 Recent meta-analysis indicates a strong correlation between the degree of methylation at lysine 4 of histone H3 (H3K4) and the prognosis of patients with malignant tumors.3 To enable epigenetic reprogramming of gene expression and chromatin structure, histone modifications are reversible. Since the discovery of LSD1 (also known as KDM1A), the first protein lysine-specific demethylase,4 protein (histone) lysine demethylases have emerged as essential medicinal targets in human diseases such as cancers where these enzymes are often misregulated and/or mutated.5,6

Two dissimilar demethylase families act on methylated H3K4: KDM1/LSD1 removes methyl groups from mono- or dimethylated H3K4 using a flavin-dependent reaction,4,7 whereas KDM5/JARID1 eliminates methyl groups from tri-or dimethylated H3K4 via an α-ketoglutarate (αKG) and Fe(II)-dependent reaction.8,9 All KDM5 family members (A-to-D) demethylate the same histone methyl mark but are present in different protein complexes and have tissue-specific expression profiles, implying distinct cellular roles.9,10

Increasing evidence from animal models and human tumors support a role for the KDM5A and KDM5B as oncogenic drivers.11,12 Significant efforts are being devoted to develop KDM5 family specific inhibitors, which include cell-permeable small molecule compounds N54 (Patent WO2016057924),13,14 CPI-455,15 KDOAM-25,16 and KDM5-C70 (Patent WO2014053491).17,18 We observed that these compounds inhibit KDM5 activity by competing with the cofactor αKG and providing one-or-two metal−ligand bonds that coordinate Fe(II) in the highly conserved active site constructed by a 2-His-1-carboxylate motif (HxE/D⋯H). KDM5 belongs to a large family of αKG and Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenases with importance in a broad range of critical cellular activities and includes enzymes that act on DNA (e.g., AlkB DNA repair enzymes and Tet 5-methylcytosine dioxygenases), RNA (e.g., mRNA 6-methyladenine demethylases), and proteins (e.g., hypoxia-inducible factor HIF1 proline hydroxylase and protein lysine demethylases KDM2−8), as well as enzymes that act on lipids, cellular metabolites, and signaling molecules.19 Due to the highly conserved nature of active sites in this mega family, ongoing efforts for the development of therapeutics to find selective small molecule inhibitors targeting specific family members have been challenging.20

In recent years, new approaches toward the development of selective covalent-modifier inhibitors have emerged wherein targeted reactivity with the thiol group of noncatalytic cysteine residues is employed.21,22 These nonenzymatic cysteines are less likely to be conserved across a large protein family, which gives an opportunity to identify a particular enzyme target and minimizes the off-target reactions. The approach of using a reactive warhead-like acrylamide to target a noncatalytic cysteine to accomplish tunable and prolonged residence time was validated for several protein kinases23–25 and a protein lysine methyltransferase.26 The reaction may require the deprotonation of the thiol (SH) to form a thiolate (S:) which functions as a nucleophile, resulting in an enolate intermediate, followed by protonation of the enolate to generate a thio-ether product.22 Previously, we identified a cysteine located near the active site in a stretch of loop containing two metal coordinating residues (C481WH483IE485), which is invariant among the four members of the KDM5 subfamily (e.g., Cys481 of KDM5A) but absent in other dioxygenases including other histone demethylases such as the KDM4 and KDM6 families (Figure 1A).27 Here, we explore the interaction between this noncatalytic Cys481 of KDM5A and inhibitors with the cysteine-reactive electrophile acrylamide.

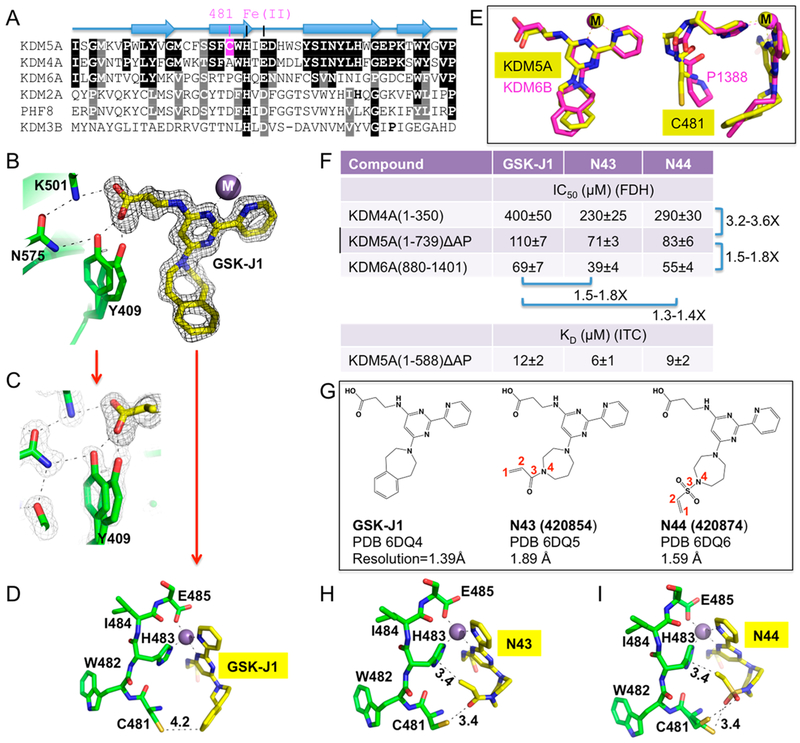

Figure 1.

Binding of KDM5A by GSK-J1 and its derivatives. (A) Sequence alignment of region of KDM5A containing Cys481 (in magenta) and corresponding regions in KDM4A (PDB code 6CG1), KDM6A (PDB code 3AVS), KDM2A (PDB code 4QXB), PHF8 (PDB code 3KV4), and KDM3B (PDB code 4C8D). KDM5A and KDM4A share the highest sequence conservation (white letters against black background), followed by KDM6A. (B) Structure of ternary complex of GSK-J1-KDM5A-Mn(II) at 1.39 Å resolution (PDB code 6DQ4). The omit electron density, contoured at 10σ above the mean, is shown for GSK-J1 (gray mesh). (C) Two alternative conformations are observed for Tyr409. The 2Fo−Fc electron density, contoured at 1.5σ above the mean, is shown for KDM5 protein residues (light gray mesh). (D) Cys481 is 4.2 Å away from the tip of GSK-J1. (E) Two orthogonal orientations of superimposed GSK-J1 bound in KDM5A (yellow) and KDM6B (magenta). Cys481 of KDM5A replaces Pro-1388 of KDM6B. (F) Summary of the IC50 values of inhibition of demethylation for catalytic domains of KDM4A, KDM5A, and KDM6A by FDH-coupled assay and isothermal titration calorimetry measurement of dissociation constants (KD) of compounds to KDM5A catalytic domain (see Figure S1 for original experimental data). (G) Chemical structures of GSK-J1 and two related derivatives. Included are summary of inhibitor-bound X-ray structures of KDM5A (see Table S1 for detailed statistics of X-ray diffraction and refinement). (H) Structural details showing interactions between KDM5A and N43 (PDB code 6DQ5). (I) Interactions displayed between KDM5A and N44 (PDB code 6DQ6).

RESULTS

In this study, we synthesized and characterized structurally and biochemically modified variants of a known KDM inhibitor, GSK-J1,28,29 as well as analogs of a new, more potent, thienopyridine-based chemotype with the goal of engaging Cys481. In total, we determined six complex structures of KDM5A bound with inhibitors to a resolution of 1.39−1.89 Å (Table S1). We define a derivative of 2-((3-aminophenyl)(2-(piperidin-1-yl)ethoxy)methyl)thieno[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylic acid containing a ((dimethylamino)but-2-enamido)phenyl moiety (N71) as a KDM5A inhibitor that covalently interacts with Cys481.

GSK-J1 Occupies the Space in Vicinity of Cys481 of KDM5A.

Previously, we modeled GSK-J1, a small molecule inhibitor initially developed for the KDM6 subfamily (which removes methyl groups from H3K27me3)28 that also cross-inhibits the KDM5 subfamily,29 in the active site of KDM5A.27 Using the purified minimal catalytic domain of KDM5A,14,17,27 we began by cocrystallizing GSK-J1 in complex with KDM5A to a resolution of 1.39 Å (Figure 1B). The near atomic resolution structure allowed us to position accurately every atom of GSK-J1 and many alternative conformations of protein side chains, particularly those of residues involved in binding of the inhibitor in the active site (Figure 1C). Most importantly, the tip of the tetrahydrobenzazepine moiety of GSK-J1 is only 4.2 Å away from the sulfur atom of Cys481 (Figure 1D).

The GSK-J1-bound KDM5A catalytic domain is similar in overall structure to the GSK-J1-bound KDM6B (PDB code 4ASK) [or KDM6A (PDB code 3ZPO)] with a root-mean-squared deviation of ~2 Å across more than 200 pairs of aligned Cα atoms. As with KDM6, the pyridyl-pyrimidine biaryl of GSKJ1 makes a bidentate contact with the metal ion and the carboxylate group of propanoic acid moiety of GSK-J1 bridging between Lys501 and Tyr409 (Figure 1B). One notable difference is that the seven-membered azepine ring is in a twist boat conformation bound in KDM5A, whereas it was modeled as a chair conformation bound in KDM6 (Figure 1E). Furthermore, the residues surrounding GSK-J1 are highly conserved between KDM5 and KDM6, supporting the cross-inhibition of GSK-J1 against the members of KDM5 family29 (Figure 1F), except that Cys481 of KDM5A replaces Pro1388 of KDM6B, which packs against the aromatic face of tetrahydrobenzazepine (Figure 1E).

Next, we modified GSK-J1 by substituting the tetrahydrobenzazepine moiety with acryloyl-1,4-diazepine (N43) or vinylsulfonyl-1,4-diazepine (N44) (Figure 1G). These substitutions replaced the rigid benzene ring in GSK-J1 with a more flexible moiety containing the reactive electrophile. The common constituents of the three compounds displayed nearly identical contacts with the metal ion and the protein residues in the active site of KDM5A (compare Figure 1D and Figure 1H,I). However, neither of these two new compounds appeared to form a covalent bond with Cys481 in our crystal structures. In N43, the carbonyl oxygen of acrylamide is 3.4 Å away from the sulfur atom of Cys481, forming a hydrogen-bond-like interaction (C=O⋯H−S), while the terminal CH2 group gains an additional van der Waals contact with the imidazole ring of His483 (Figure 1H). This new interaction might be responsible for the moderate improvement from the original GSK-J1 in binding affinity (2× reduced dissociation constant KD) and enzyme inhibitory activity (1.5× reduced IC50 value for KDM5A catalytic domain and 4.5× reduced for near full-length KDM5A) (Figures 1F and S1−S2).

Similarly, in N44, the side chain of Cys481 adopts two alternative conformations in interaction with one of the sulfonyl oxygen atoms (Figure 1I). These observations suggested that rotating the torsional angle along the C3−N4 bond in N43, or S3−N4 bond in N44, might place the terminal CH2 group of the double bond close to the sulfur atom of Cys481, within covalent bonding distance, but the geometry of bond angle along the three atoms S⋯C1=C2 is ~160°, which is not optimal for a covalent bond formation, which would require the sulfur nucleophile to approach the double bond in an angle close to 116°.30

Synthesis of Analogs of GSK-J1.

Analogs of GSK-J1 (compounds N43 and N44) were synthesized by the SNAr reaction of monoprotected homopiperazine with the corresponding chloropyrimidine (Scheme 1). The warheads were attached via acid chloride or HATU-mediated coupling. Hydrolysis of the ethyl ester was performed with trimethyltinhydroxide to afford the final compounds.31

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Compounds N43 and N44

Thienopyridine−Carboxylate Scaffold.

Recently, we characterized a collection of compounds containing a 1H-pyrrolo[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylate (pyridine-7-carboxylate) moiety and 2-chlorophenyl moiety connected to a variable length of alkoxyether bound to KDM5A (e.g., compound N46; Figure 2A).14 These compounds are racemic mixtures containing a chiral secondary carbon atom (highlighted by a red star in Figure 2A) connected by the three different substituents and a hydrogen atom. We replaced the pyrrolo ring NH group with a sulfur atom and generated compound N49 [2-((2-chlorophenyl)(2-(1-methylpyrrolidin-2-yl)ethoxy)-methyl)thieno[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylic acid] (Figure 2B). The dissociation constants (KD), measured by isothermal titration calorimetry, indicated that the difference in binding affinity to KDM5A between N46 and N49 is approximately 2-fold (Figure S1B). In comparison, two pure enantiomers of a related compound (e.g., N40) exhibited approximately a 4-fold difference in binding affinity;14 we thus concluded that the thienopyridine binds in a similar manner to pyrrolopyridine carboxylate scaffold.

Figure 2.

Comparison of N46 and N49. (A,B) Chemical structures of N46 and N49 are identical except containing a 1H-pyrrolo[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylate moiety (panel A) or thienopyridine-7-carboxylate (panel B). Included are a summary of ITC measurements of dissociation constants (KD) (see Figure S1B for original binding data) and a summary of inhibitor-bound X-ray structures of KDM5A (Table S1). (C) In the racemic mixture of compound N49 (PDB code 6DQ8), two possible conformations of 2-chlorophenyl moiety can be modeled into the electron density. (D) View rotated ~180° from panel C.

As expected from the racemic mixture of compound N49, we observed two conformations (S and R) in the electron density, each with approximately 50% occupancy (Figure 2C). In the S-enantiomer (cyan in Figures 2C,D), the chlorine atom of 2-chlorophenyl makes van der Waals interactions with Ala411 and Tyr409, whereas in the R-enantiomer (yellow in Figures 2C,D), the corresponding chlorine atom forms a van der Waals contact with His483, a mimic to what was observed between KDM5A and the terminal CH2 group of acrylamide moiety in N43 (Figure 1H). The distance between Cys481 and the phenyl ring carbon-3 position of (R)-N49 is 4.5 Å.

Engaging Cys481.

We next replaced the 2-chlorophenyl moiety in N49 with a 3-aminophenyl group, as well as a substitution of piperidine for pyrrolidine to generate N70 (Figure 3A). The latter replacement did not affect binding affinity to KDM5A.14 This resulted in an amino group in close contact (3.2 Å) with Cys481, forming a hydrogen-bond-like N− H⋯S interaction (Figure 3B). It appears that the sulfur atom of Cys481 is deprotonated and functioning as a proton acceptor. Although the racemic mixture of N70 was used for crystallization, the electron density mapped well with the R-enantiomer (Figure 3B), signifying the preferential binding of this enantiomer to the protein.

Figure 3.

Structural snapshots of covalent modifiers bound into KDM5A active site. (A) Chemical structure of N70. (B) The amino group of 3-aminophenyl moiety of N70 involves in a H-bond-like interaction with Cys481 (PDB code 6DQA). The omit electron density, contoured at 5σ above the mean, is shown for the inhibitor (gray mesh). (C) Chemical structure of N71. (D) A covalent bond is formed between Cys481 and the C1 carbon of N71 (PDB code 6DQB). (E) Two methyl groups of the capping dimethylamino-2-butenamide moiety formed weak H-bond contacts with main chain carbonyl oxygen atoms of Ser479 and Arg76, whereas the nitrogen was solvent exposed to water molecules (away from the viewer). (F) Superimposition of N70 and N71 bound with KDM5A. Note the rotation along the chiral carbon and pyrrolopyridine ring resulting in movement of 3-aminophenyl ring and alkoxyether piperidine moiety. (G) Chemical structure of Afatinib contains the same moiety of dimethylamino-2-butenamide. (H) Afatinib covalently inhibits EGFR kinase (PDB code 4G5J).

The first step of cysteine covalent modification involves deprotonation of the thiol (SH) to form a thiolate (S:), which functions as a nucleophile.22 Encouraged by the potentially reactive Cys481 thiolate noted in the N70 structure above, we replaced the amino group at the phenyl ring carbon-3 position in N70 with a dimethylamino-2-butenamide moiety, harboring a reactive acrylamide group to yield N71 (Figure 3C). A covalent bond is clearly formed between Cys481 and the Michael acceptor group of N71 (S−C distance = 1.8 Å and Cβ−S−C1 angle = 110°; Figure 3D). The dimethylamino group H-bonds with a water molecule and interacts with the main chain carbonyl oxygen atoms of Arg76 and Ser479, respectively, via two C−H⋯O=C type of hydrogen bonds32 (Figure 3E). In addition, the carbonyl oxygen of the acrylamide group of N71 makes a hydrogen bond with the main-chain amide nitrogen of Cys481 (Figure 3D), a conformation that is rotated from that of N70 (Figure 3F). The same moiety, dimethylamino-2-butenamide, has been used in Afatinib (Figure 3G), a protein kinase inhibitor that irreversibly inhibits human epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) family tyrosine kinases33 (S−C distance = 1.8 Å and Cβ−S−C1 angle = 111°; Figure 3H). The conformation of the covalent bond formation is highly similar between KDM5A-N71 and EGFR kinase bound to Afatinib34 (compare Figure 3D and H).

Covalent Bond Formation in Solution.

We explored several approaches to evaluate the compound behavior in solution. Because the pyrrolopyridine-7-carboxylate-based compounds (N49, N70, and N71) are intrinsically fluorescent and interfere with the fluorescence signal of the formaldehyde dehydrogenase (FDH)-coupled demethylase assay,14 we first utilized an AlphaLISA-based assay to measure potency and selectivity of these compounds against the activities of KDM5A, KDM5B, KDM4A, and KDM6A. This assay employs an antibody against histone H3 methylated at K4 (for KDM5), K9 (for KDM4A), or K27 (for KDM6A) to measure the demethylation of histone peptide substrates specific for each enzyme (Figure 4A and S2). Interestingly, the selectivity for KDM5B over KDM4A was 3 times greater (24-fold) for the covalent inhibitor N71 compared with two noncovalent inhibitors (N49 and N70), which is approximately 7−8-fold (Figure 4A; both enzymes are recombinant catalytic domains purified from Escherichia coli and tested under the same enzyme concentration). All three inhibitors have the same high selectivity against KDM6A (Figure S2). In addition to the enhanced selectivity, the strength of the covalent bond also conferred a 2-fold increase in enzyme inhibitory activity (i.e., IC50 value decreased ~2× for N71 as compared to the noncovalent N70). As expected, the inhibition constants of N70 and N71 are about the same against KDM4A, which shares the highest sequence conservation to KDM5A but lacks the cysteine at the corresponding position (Figure 1A).

Figure 4.

Irreversible inhibition of KDM5A in solution. (A) Summary of AlphaLISA derived IC50 values from inhibition of demethylation by KDM5B and KDM4A (see Figure S2 for original inhibition data). (B−G) IC50 values of compounds N70 and N71 against KDM5A(1−739)ΔAP using the Promega Succinate-Glo assay under three αKG concentrations. The order involves preincubation (20 min) with the inhibitors before the addition of αKG to initiate the reaction. (B) Inhibition of KDM5A by N70 is αKG dependent. (C) N71 has no significant change to IC50 values with variation in αKG concentration. (D) Inhibition of KDM5A by N71 is enzyme concentration dependent. (E,F) Inhibition of KDM5A with N71 (E) or N70 (F) with or without incubation for 20 min. (G) Preformation of enzyme−inhibitor complex ([E] = 5 μM and initial [I] = 100 μM) followed by four times of buffer exchange removes the noncovalent modifying N70 from solution but does not perturb N71 complex with KDM5A. (H) KDM5A ([E] = 0.8 μM) was preincubated with five concentrations of N71 ([I] = 0.01−5 μM). At each time point, the enzymatic reaction started by adding 5 μL of preincubated E+I complex to a solution containing H3 peptide ([S] = 60 μM) and αKG (100 μM), and the reaction was stopped after 7 min. (I) Inactivation plot, logarithm of the % remaining activity versus preincubation time. (J) Nonlinear regression analysis of the negative slopes against inhibitor concentration gives rise to kinact and KI values as indicated. (K) Summary of electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-tandem-MS) of KDM5A in the absence and presence of inhibitors (see Figure S3 for raw spectrum). KDM5A (50 μM) was incubated with excess inhibitor (0.5 mM) for 30 min at ambient temperature.

Next, we used an alternative approach to assess enzyme activity utilizing the Promega Succinate-Glo demethylase assay, a bioluminescence-based assay for detecting the activity of demethylases that use αKG as substrate and release succinate as a product.35 As expected, the inhibition of KDM5A by the noncovalent inhibitor N70 was dependent on αKG concentration (Figure 4B), whereas that by the covalent inhibitor N71 did not appear to be sensitive to the αKG concentration (Figure 4C). Instead, inhibition by N71 was dependent on enzyme concentration (Figure 4D), a feature expected for a covalent modifier exhibiting tight binding. As a result, we observed enhanced inhibition for the covalent modifier, i.e., the IC50 value for N71 was now ~50-fold lower than that of N70 at 100 μM αKG concentration. In addition, preincubation with KDM5A increased inhibition potency of N71, whereas N70 was insensitive (Figure 4E,F), suggesting that N71 undergoes a time-dependent inhibition. Furthermore, whereas enzyme activity could be restored after buffer exchange (or dilution) for the N70-bound KDM5A, it had no effect on the inhibition of N71-bound KDM5A (Figure 4G) consistent with very tight or irreversible binding between the compound and KDM5A. We also characterized parameters of kinact (maximal rate of inactivation) and KI (concentration at 50% kinact) of N71 by varying five different inhibitor concentrations (Figure 4H–J).36 The value of kinact/KI of N71 against KDM5A is approximately 8.0 × 103 M−1 s−1. Finally, we confirmed by mass spectrometry that N71, but not N70, covalently modified KDM5A enzyme completely (Figures 4K and S3). The addition of mass equals to one N71 molecule in the presence excess of N71, despite the enzyme containing multiple cysteine residues on its surface. Together with structural observation, these data support N71 as a KDM5A inhibitor that covalently interacts with Cys481.

Isopropyl Ester Derivative of Thienopyridine−Carboxylic Acid Is Cytotoxic.

As with the pyrrolopyridine-7-carboxylate-based compounds described here and in our earlier work,14 some known KDM inhibitors, such as KDM5-C49 (Patent WO2014053491) and GSK-J1,28,29 contain a carboxylate moiety that engages hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions with the active-site residues Tyr409 and Lys501 (Figure 1B,C), but precludes cell uptake. For this reason, the respective ethyl ester derivatives, KDM5-C70 and GSK-J4, were synthesized as cell-permeable prodrugs that are hydrolyzed by cellular esterase(s) to generate active KDM5-C49 and GSK-J1, respectively. We therefore synthesized SI-5 and N73, the isopropyl ester derivatives of N70 and N71, respectively, and tested their cellular activities (Figure 5A). We measured the effective permeability using the parallel artificial membrane permeability assay (PAMPA).37 In each case, the ester derivative is much more permeable than the corresponding free acid (N73 > N71 and SI-5 > N70) (Figure 5B). The permeability of compounds is in the order SI-5 (high) > N73 ≈ N70 (moderate) > N71 (low).

Figure 5.

Concentration dependence of cytotoxicity of N73. (A) Chemical structures of ethyl (GSK-J4 and KDM5-C70) or isopropyl ester (N73 and SI-5) derivatives of indicated compounds. (B) PAMPA permeability. (C,D) Western blot analyses of MCF7 cells treated with the indicated concentration of compounds or DMSO (0.1%) control for 30 or 48 h. Total cells lysates were used for assays using indicated antibodies. (E) N73 (isopropyl ester derivative of N71) does not increase H3K4me3 level in BT474 cells at 48 h as measured by immunocytochemistry. (F) Rapid cytotoxicity in BT474 cells treated with N73 at concentrations >5 μM. Cell viability was measured using a CellTiter-Glo assay 24 h after treatment. (G,H) Proliferation of BT474 cells treated with N73 or SI-5. Percent confluence was tracked over 300 h by imaging the cells every 4 h using an IncuCyte live cell imaging system. (I) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of the indicated mRNAs in MCF7 cells treated with the indicated concentration of compounds or DMSO for 48 h. Data from biological triplicate experiments are shown.

Exposure of MCF7 (ER+) or BT474 (HER2+) breast cancer cells to 1 μM KDM5-C70 resulted in an increase in cellular H3K4me3 levels, as previously described14,17 (Figure 5C,D), the isopropyl ester derivative N73 had no impact on cellular H3K4me3 methylation levels at doses up to 5 μM (Figure 5E). We note that GSK-J4 influences little of the overall levels of H3K4me3 or H3K27me3 in MCF7 under the same conditions tested (Figure 5C). Nevertheless, N73 did affect cellular proliferation and viability of BT474 cells rapidly within 24 h (Figure 5F). Interestingly, the steep loss of proliferation and viability only occurs at doses of N73 above 5 μM (Figure 5F), whereas the low doses do not affect cell growth over the period of >12 days (Figure 5G). In contrast, SI-5, which has greater permeability but lacks the reactive acrylamide group, only showed some growth inhibition at the highest concentration tested (28 μM) (Figure 5H).

Similarly, we observed a noteworthy difference in cell killing within 24 h between 5 and 10 μM of N73 concentrations in cells of MCF7, MDA-MB-231 (triple negative for HER2, PR, and ER), and HEK293T (human embryonic kidney cells) (Figure 6A–C). These observations suggested that N73 at concentrations above 5 μM has strong and rapid growth inhibitory/cell killing activity among the cell types tested, although whether this is tied to the inhibition of endogenous KDM5 enzymes will require further studies. Several target genes of KDM5-mediated repression have been identified, and we focused here on three genes whose expression was up-regulated upon KDM5-C70 treatment in MCF7 cells: STING38 and MT1F and MT1H17 (Figure 5D,I). Treatment of MCF7 with N73 at concentrations of 1 or 5 μM for 2 days led to small changes (<2×) in the expression of STING, MT1F, and MT1H (Figure 5D,I). In contrast, admission with KDM5-C70 under the same condition (1 μM for 2 days) increased the expression of the three targets up to 6-fold.

Figure 6.

Images of bright-field microscopy of live cells after 24 h post-treatment with indicated concentrations of KDM5-C70 (top), N71 (middle), and N73 (bottom) or 0.1% DMSO (upper left corner) in MCF7 (A), MDA-MB-231 (B), and HEK293T (C). Scale bar is 50 μM.

Synthesis of Covalent KDM5 Inhibitors N71 (Acid) and N73 (Isopropyl Ester).

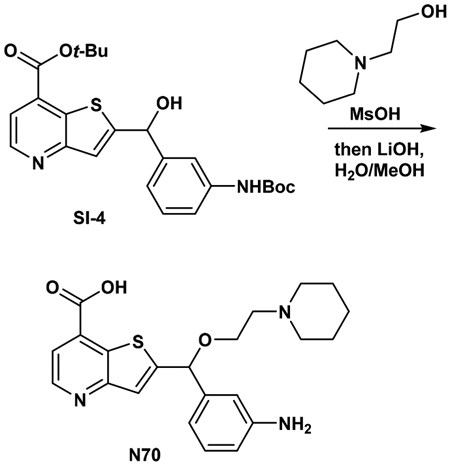

Synthesis of the covalent modifiers started with esterification of the commercially available 2-bromothieno[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylic acid with Boc-anhydride.39 The corresponding Grignard reagent was then prepared and reacted with ditert-butyl (3-formylphenyl) imidodicarbonate to provide the benzyl alcohol as a mixture of mono- and bis-tert-butyl carbamates.40 Solvolysis of the benzyl alcohol with excess 1-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperidine in methanesulfonic acid followed by alkaline hydrolysis and reverse phase purification (0.1% TFA modifier) afforded N70 as the TFA salt. The isopropyl ester SI-5 could be synthesized by treatment with TMS-Cl in anhydrous isopropanol. Formation of the final covalent modifiers N71 and N73 was accomplished by treatment with (E)-4-(dimethylamino)but-2-enoic acid in the presence of HATU (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Compounds N70, N71, N73, and SI-5

The stability of acid/ester pairs N71/N73 and N70/SI-5 in culture media was assessed after 24 h. Approximately 80% of N73 remained unchanged (no N71 was detected), while only 60% of N71 remained unchanged (Figure S4A). This suggests that the covalent group is reasonably stable over 24 h. Correspondingly, 75% of SI-5 and 93% of N70 remained unchanged after 24 h. Approximately 1% of SI-5 is converted into N70 under the same conditions and suggests that the isopropyl ester imparts good stability to these series of compounds in culture media.

To understand how much of the acid/ester pair N71/N73 was present in cells in our growth inhibition assays, we performed a cellular extract experiment. These compounds were individually incubated with BT474 cells for 24 h and lysed to determine cell extract concentrations. The ester N73 appeared to be highly permeable and was detected at levels 100-fold greater than the acid N71 (Figure S4B), in agreement with the PAMPA measurement (Figure 5B). Subsequent intracellular esterase-mediated conversion of the ester N73 to acid N71 appeared to be inefficient under the conditions tested.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Studies in cancer-related processes (of metastasis, drug resistance, and cell proliferation) and in genetically engineered mouse tumor models9–11,41–43 suggested that KDM5 inhibitors can be used for treatment of cancers, particularly in multidrug-resistant cells where expression of many histone demethylases are increased and KDM5 depletion reversed the resistant phenotype.44–46 Our efforts to depict the interactions of KDM5A with diverse chemotypes of inhibitors provide fundamental knowledge into structure−activity relationships of inhibitors against KDM5.14,17,27

Here, we present N71 [(E)-2-((3-(4-(dimethylamino)but-2-enamido)phenyl)(2-(piperidin-1-yl)ethoxy)methyl)thieno-[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylic acid] as the first covalent modifier of KDM5 family enzymes. In vitro, the reactive ((dimethylamino)but-2-enamido)phenyl moiety of N71 forms a covalent interaction with Cys481 of KDM5A. The covalently modified KDM5A exhibited an inhibition mode dependent on enzyme concentration, unlike most of the other KDM5 inhibitors to date, which act as αKG-competitive inhibitors, yielding an increased selectivity for the KDM5 family over KDM4A (24×) relative to other KDM5 inhibitors, including KDM5-C70 (10×),17 which has shown the most promise to date in cell-based studies.

Our study aids in the design and synthesis of potent and selective inhibitors of KDM5 demethylases. A lasting challenge is to make these compounds cell permissible. Low permeability of the potent KDM5A inhibitors is probably owing to the overall compound polarity and/or acidic nature of the carboxylate moiety. Chemical modifications are required to increase cell permeability of these compounds. Several cell-permeable compounds are available that lack a carboxylate moiety, including (R)-N54,13,14 CPI-455,15 and KDOAM-2516 (which replaces the carboxylate of KDM5-C49 with a carboxyamide), as well as a range of noncarboxylate (and nonselective) inhibitors for the families of KDM5 and KDM4.47 In addition to the thienopyridine-carboxylate (involved in interactions with metal ion and Lys501/Tyr409 cluster) and the Cys481-reactive acrylamide group of 3-aminophenyl moiety, the third component of N71 (alkoxyether piperidine moiety) is relatively flexible (Figure 3D). It may be beneficial to substitute/add chemical moieties48 along this third branch to make more cell penetrant compounds.

While the isopropyl ester derivative N73 showed some growth inhibitory and cytotoxic activity against various cell lines of breast cancer, the molecular basis of this activity is currently unknown, and whether it derives from engagement of its intended cellular target (KDM5) remains to be determined. Under similar conditions, treatment with N71 had no effect on cell growth (Figure 6A–C). Nevertheless, whether there are compensatory mechanisms at play to balance H3K4me levels (e.g., increased activity of cognate histone lysine methyltransferase(s)) remains to be determined. Our previous work has revealed that the impact on total H3K4me3 levels is not always a reliable predictor of growth inhibitory activity across different cell lines suggesting that other factors beyond enzyme inhibition contribute to the cytotoxic effects of KDM5 inhibitors.14,17 This result could stem from a combination of incomplete hydrolysis of the isopropyl ester derivative in the cell and/or potentially interaction with off-target proteins. Covalent inhibitors of other epigenetic modifiers have been successfully translated to clinical practice despite the high cytotoxicity such as the aforementioned Afatinib, which demonstrated complete cytotoxicity for the EGFR expressing K562 cells at a very low dose (10 nM),49 and nucleoside analogs.50 DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitors, including 5-azacytidine and decitabine, become incorporated into replicating DNA as an altered cytosine base and create a DNA−DNMT covalent complex that ultimately drives the destruction of DNMT1 and hypomethylation of DNA.51 Similarly, the primary anticancer effect of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors correlates with trapping of DNA−PARP complexes at sites of DNA damage.52 Combining DNMT and PARP inhibitors enhanced cell death and increased antitumor effects in vivo.53 At present, we do not know how and where, at a molecular level, the isopropyl ester derivative of N71 acts to inhibit growth and viability, but we note that the closely related methyl ester derivatives of pyrrolopyridine-7-carboxylate-based compounds showed no growth inhibitory activity when similarly tested14 (and the methyl ester is not appreciably hydrolyzed in cells; Figure S4C). Further study will not only be invaluable in deciphering the pathway(s) affected by these molecules but also may serve as a starting point for a new class of potent inhibitors of histone lysine demethylase as anticancer agents.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

The Supporting Information contains previously described experimental methods including protein crystallography, isothermal titration calorimetry, formaldehyde dehydrogenase (FDH)-coupled demethylase assay, AlphaLISA assay, Western blot analysis, H3K4me3 immunocytochemistry, and IncuCyte live cell analysis. Compound synthesis and assays new to this study are described here.

Compound Synthesis.

Compounds were synthesized at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Purity determination was performed using an Agilent Diode Array Detector for both Method 1 and Method 2 (below). Mass determination was performed using an Agilent 6130 mass spectrometer with electrospray ionization in the positive mode. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on Varian 400 MHz spectrometers. Chemical shifts for final compounds are reported in ppm with undeuterated solvent (DMSO-d6 at 2.50 ppm) as internal standard for DMSO-d6 solutions. Chemical shifts for intermediate compounds are reported in ppm with undeuterated solvent (CDCl3 at 7.26 ppm) as internal standard for CDCl3 solutions. All the analogs tested in the biological assays have purity greater than 95%, based on both analytical methods. High resolution mass spectrometry was recorded on Agilent 6210 Time-of-Flight LC/MS system. Confirmation of molecular formula was accomplished using electrospray ionization in the positive mode with the Agilent Masshunter software (version B.02).

Method 1.

A 7 min gradient of 4% to 100% acetonitrile (containing 0.025% trifluoroacetic acid) in water (containing 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid) was used with an 8 min run time at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. A Phenomenex Luna C18 column (3 μm, 3 × 75 mm) was used at a temperature of 50 °C.

Method 2.

A 3 min gradient of 4% to 100% acetonitrile (containing 0.025% trifluoroacetic acid) in water (containing 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid) was used with a 4.5 min run time at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. A Phenomenex Gemini Phenyl column (3 μm, 3 × 100 mm) was used at a temperature of 50 °C.

All air or moisture sensitive reactions were performed under positive pressure of nitrogen or argon with oven-dried glassware. Anhydrous solvents and bases such as dichloromethane, N,N-dimethylforamide (DMF), acetonitrile, ethanol, DMSO, dioxane, DIPEA (diisopropylethylamine), and triethylamine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Palladium catalysts were purchased from Strem Chemicals and used as such. Preparative purification was performed on a Waters semi-preparative HPLC system using a Phenomenex Luna C18 column (5 μm, 30 × 75 mm) at a flow rate of 45 mL/min (For all compounds tested, the HPLC traces were provided in Supplementary Figure S5). The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile and water (each containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid). A gradient of 10% to 50% acetonitrile over 8 min was used during the purification. Fraction collection was triggered by UV detection (220 nm). Analytical analysis was performed on an Agilent LC/MS (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA).

Synthesis of Ethyl 3-((6-(1,4-Diazepan-1-yl)-2-(pyridin-2-yl)-pyrimidin-4-yl)amino)propanoate (SI-0).

(Patent WO2012/52390A1; page 55.) To a solution of ethyl 3-((6-chloro-2-(pyridin-2-yl)pyrimidin-4-yl)amino)propanoate (1.2 g, 3.91 mmol) and 1-Bochomopiperazine (0.838 mL, 4.30 mmol) in dioxane was added DIPEA (2.050 mL, 11.74 mmol), then heated in microwave for 1.5 h at 150 °C. The mixture was the concentrated in vacuo, and the residue was extracted with ethyl acetate and washed with ammonium chloride and brine. The organic layer was dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was then purified on icso-normal phase eluting with 40−100% EA (contains 1% TEA) in hexanes using an 80 g column. The last fraction was pooled and dried to get a white solid, which was then treated with a 1:1 mixture of DCM/TFA to provide SI-0 as the TFA salt. LC−MS retention time: t1 = 2.75 min; LC−MS M + H = 373.

Synthesis of 3-((6-(4-Acryloyl-1,4-diazepan-1-yl)-2-(pyridin-2-yl)-pyrimidin-4-yl)amino)propanoic Acid (N43).31

To a solution of ethyl 3-((6-(1,4-diazepan-1-yl)-2-(pyridin-2-yl)pyrimidin-4-yl)amino)-propanoate (0.1 g, 0.255 mmol, 1 equiv) SI-0 in DCM (2 mL) at 0 °C, DIPEA (0.13 mL, 0.76 mmol, 3 equiv) and acryloyl chloride (0.021 mL, 0.255 mmol, 1 equiv) were added. The reaction was allowed to stir at room temperature for 1 h and was then concentrated in vacuo. The crude ethyl ester residue was taken up in DCE (2 mL), and hydroxytrimethylstannane (0.194 g, 1.072 mmol, 1 equiv) was added. The reaction was then capped and placed in a microwave and heated at 120 °C for 1 h. The reaction was then passed through a syringe filter and purified on HPLC to provide N43 as the TFA salt. LC−MS retention time: t1 = 2.43 min; t2 = 3.46 min LC−MS M + H = 397. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.67−8.65 (m, 1H), 8.23−8.20 (m, 1H), 7.89−7.85 (m, 1H), 7.43−7.40 (m, 1H), 6.79−6.70 (m, 2H), 6.16−5.96 (ddd, J =60.1, 16.6, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 5.68−5.51 (m, 2H), 3.82−3.59 (m, 6H), 3.53−3.43 (m, 4H), 2.55−2.51 (m, 2H), 1.87−1.80 (m, 2H).

Synthesis of 3-((2-(Pyridin-2-yl)-6-(4-(vinylsulfonyl)-1,4-diazepan-1-yl)pyrimidin-4-yl)amino)propanoic Acid (N44).

The compound was synthesized as above except using ethenesulfonyl chloride in place of acryloyl chloride. The mixture was purified on HPLC to provide N44 as the TFA salt. LC−MS retention time: t1 = 2.60 min; t2 =3.73 min; LC−MS M + H = 433. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.13 (br s, 1H), 8.65−8.59 (m, 1H), 8.18 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.83 (td, J = 7.7, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.40−7.37 (m, 1H), 6.78−6.63 (m, 2H), 5.99 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 5.89 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 5.57 (s, 1H), 3.82−3.77 (m, 2H), 3.71−3.65 (m, 2H), 3.50−3.44 (m, 2H), 3.36 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H),3.22−3.11 (m, 2H), 1.88−1.81 (m, 2H).

Synthesis of tert-Butyl 2-bromothieno[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylate (SI-1).

To a solution of 2-bromothieno[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylic acid (1 g, 3.87 mmol, 1 equiv) and DMAP (0.237 g, 1.937 mmol, 0.5 equiv) in 5 mL of THF was added Boc-anhydride (2.249 mL, 9.69 mmol, 2.5 equiv) in 5 mL. The reaction was heated to 65 °C and stirred for 4 h at the same temperature. The reaction was monitored by LC−MS for disappearance of starting material. The reaction was concentrated, and the residue was extracted with ethyl acetate (50 mL) and washed with aqueous sodium bicarbonate (1 × 10 mL). The organic layer was dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified on isco-normal phase using an 80 g silica column eluting with 0−40% ethyl acetate in hexanes over 18 CV (elutes around 20−25% ethyl acetate). The fractions were collected and concentrated in vacuo to provide 1.1 g of tert-butyl 2-bromothieno[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylate SI-1 (90% yield). LC−MS retention time: t1 =3.87 min; LC−MS M + H = 314/316. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.75 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H), 7.84−7.74 (m, 1H), 7.67 (s, 1H), 1.68 (s, 9H).

Synthesis of tert-Butyl 2-((2-Chlorophenyl)(hydroxy)methyl)-thieno[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylate (SI-2).40

A small vial capped with a rubber septa and nitrogen line was cooled with an external ice water bath. A solution of isopropylmagnesium chloride (2.0 M in THF, 0.38 mL, 0.76 mmol, 1.2 equiv) was added followed by an additional 2 mL of THF. Then, 2,2′-oxybis(N,N-dimethylethanamine) (0.15 mL, 0.76 mmol, 1.2 equiv) was added neat dropwise over 20 s. A white precipitate forms, and the reaction was warmed to room temperature by removing the cooling bath. (Note: if reaction completely solidifies, additional THF can be added.) After 5 min, the vial was again placed in the ice water cooling bath, and tert-butyl 2-bromothieno[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylate (200 mg, 0.637 mmol) was added as a solution in 1 mL of THF. The reaction turned orange and was kept at 0 °C for 5−10 min. Then, 2-chlorobenzaldehyde (0.09 mL, 0.82 mmol) was added as a solution in 1 mL of THF. The reaction was slowly warmed to room temperature and stirred for at least 1 h (as monitored by LC−MS). Depending on the amount of 2-chlorobenzaldehyde added, the ketone could form in addition to the alcohol (possibly via a magnesium-mediated Oppenauer-type oxidation). If this occurs, the reaction can be diluted with methanol and a small amount of sodium borohydride can be added (1 equiv). The reaction was then concentrated in vacuo, and the residue was taken up in ethyl acetate (20 mL). The organic layer was washed with water (1 × 10 mL) and brine (1 × 10 mL). The organic layer was separated, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was taken up in a small amount of DCM and purified on normal phase isco using a 24 g gold column eluting with 0 → 50% ethyl acetate in hexanes over 12 min (product elutes at around 50% ethyl acetate). The pure fractions were collected and concentrated in vacuo to provide 154 mg of tert-butyl 2-((2-chlorophenyl)(hydroxy)methyl)thieno[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxy-late SI-2 (64% yield). LC−MS retention time: t1 = 3.59 min; LC−MS M + H = 376. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.68 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H), 7.76−7.71 (m, 2H), 7.43 (d, J = 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.38−7.29 (m, 2H), 7.27−7.23 (m, 1H), 6.56 (s, 1H), 3.81 (br s, 1H), 1.65 (s, 9H).

Synthesis of 2-((2-Chlorophenyl)(2-(1-methylpyrrolidin-2-yl)-ethoxy)methyl)thieno[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylic Acid (N49).

tert-Butyl 2-((2-chlorophenyl)(2-(1-methylpyrrolidin-2-yl)ethoxy)-methyl)thieno[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylate (110 mg, 0.29 mmol, 1 equiv) was put into a 2−5 mL microwave vessel along with a small stir bar. 2-(1-Methylpyrrolidin-2-yl)ethanol (119 μL, 0.88 mmol) was added to the bottom of the microwave vessel, and then methanesulfonic acid (330 μL, 5.12 mmol) was added. The vessel was then purged with a nitrogen stream, and the vessel was sealed with a microwave cap. The reaction was then placed in a preheated reaction block set to 150 °C, and the reaction was stirred for 10−15 min. The reaction turns slightly orange over 10−15 min (if it turns brown or black, the product will have likely decomposed). It is important not to heat this reaction at 150 °C for too long because it will decompose. The reaction was monitored by LC−MS and usually contained a transesterification product in addition to the free acid product. After 10−15 min, the reaction was removed from the heating block and allowed to cool to room temperature. A small amount of water (~1 mL) was added slowly (heat produced) followed by lithium hydroxide (140 mg, 5.85 mmol, 20 equiv). A small amount of methanol was added (<1 mL) to decrease viscosity to allow for stirring and to solubilize organics. The mixture was then loaded directly onto a 100 g gold reverse phase isco column eluting with 10% acetonitrile (0.1% TFA modifier) for 3 min, then 10 → 100% acetonitrile (0.1% TFA modifier) in water (0.1% TFA modifier) from minutes 3−17. The product elutes around 40−50% acetonitrile. The pure fractions were collected and concentrated in vacuo to provide 2-((2-chlorophenyl)(2-(1-methylpyrrolidin-2-yl)ethoxy)methyl)thieno-[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylic acid as a TFA salt. LC−MS retention time: t1 = 2.30 min; t2 = 2.73 min. LC−MS M + H = 431/433. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12−11.5 (br s, 1H), 8.61 (dd, J = 4.7, 0.5 Hz, 1H), 7.72−7.68 (m, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 7.49−7.46 (m, 1H), 7.44−7.34 (m, 3H), 6.14−6.12 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 3.73−3.54 (m, 2H), 3.44 (br s, 1H), 3.17 (br s, 1H), 2.87 (br s, 1H), 2.71−2.70 (m, 3H), 2.27−2.21 (m, 2H), 1.91−1.79 (m, 3H), 1.74−1.64 (m, 1H).

Synthesis of Ditert-butyl (3-formylphenyl) Imidodicarbonate (SI-3).

To a solution of tert-butyl (3-formylphenyl)carbamate (3.19 g, 14.42 mmol, 1 equiv) in 25 mL of t-BuOH, DMAP (0.176 g, 1.442 mmol, 0.1 equiv) and Boc-anhydride (3.78 g, 17.3 mmol, 1.2 equiv) were added. The reaction was then heated to 60 °C for 18 h and then an additional 0.5 equiv of Boc-anhydride was added. The reaction was heated at 60 °C for an additional 4 h. As monitored by LC−MS, the starting material was consumed. The reaction was then concentrated in vacuo, and the residue was diluted in a small amount of DCM and then purified on normal phase isco with a 120 g column eluting with 0 → 20% ethyl acetate in hexanes. LC−MS retention time: t1 = 3.57 min; LC−MS 2M + Na = 665. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.02 (s, 1H), 7.84−7.81 (m, 1H), 7.68−7.67 (m, 1H), 7.54 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.44−7.41 (m, 1H), 1.43 (s, 18H).

Synthesis of tert-Butyl 2-((3-((di-tert-butoxycarbonyl)imido)-phenyl)(hydroxy)methyl)thieno[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylate (SI-4).

The Grignard reagent was prepared as before and was reacted with ditert-butyl (3-formylphenyl) imidodicarbonate. The reaction was slowly warmed to room temperature and stirred for at least 1 h (as monitored by LC−MS). The reaction was then concentrated in vacuo, and the residue was taken up in ethyl acetate (20 mL). The organic layer was washed with water (1 × 10 mL) and brine (1 × 10 mL). The organic layer was separated, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was taken up in a small amount of DCM and purified on normal phase isco using a 40 g gold column eluting with 0 → 50% ethyl acetate in hexanes over 12 min (product elutes at around 50% ethyl acetate). The product elutes as a mixture of monoprotected and bis-protected aniline. The mixture of products was taken forward to the next reaction without further purification. LC−MS retention time: t1 = 3.98 min; LC−MS M + H = 557. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.75 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.49−7.40 (m, 3H), 7.31 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (s, 1H), 6.56 (s, 1H), 1.65 (s, 9H), 1.49 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 18H).

Synthesis of 2-((3-aminophenyl)(2-(piperidin-1-yl)ethoxy)-methyl)thieno[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylic acid (N70).

tert-Butyl 2-((3-((di-tert-butoxycarbonyl)imido)phenyl)(hydroxy)methyl)thieno-[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylate (0.9 g, 1.617 mmol, 1 equiv) was put into a 20 mL microwave vessel along with a small stir bar. 2-(Piperidin-1-yl)ethan-1-ol (0.785 mL, 5.91 mmol, 3 equiv) was added to the bottom of the microwave vessel, and then methanesulfonic acid (2.24 mL, 34.5 mmol, 17.5 equiv) was added. The vessel was then purged with a nitrogen stream, and the vessel was sealed with a microwave cap. The reaction was then placed in a preheated reaction block set to 120 °C, and the reaction was stirred for 4 h. The reaction was monitored by LC−MS and usually contained a transesterification product in addition to the free acid product. After 4 h, the reaction iswas removed from the heating block and allowed to cool to room temperature. A small amount of water (~5 mL) was added slowly (heat produced) followed by lithium hydroxide (944 mg, 39.4 mmol, 20 equiv). A small amount of methanol was added (<3 mL) to decrease viscosity to allow for stirring and to solubilize organics. The mixture was then loaded directly onto a 100 g gold reverse phase isco column eluting with 10% acetonitrile (0.1% TFA modifier) for 3 min, then 10 → 100% acetonitrile (0.1% TFA modifier) in water (0.1% TFA modifier) to obtain the TFA salt. LC−MS retention time: t1 = 2.14 min; t2 = 2.81 min; LC−MS M + H = 412. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.18 (br s, 1H), 8.82 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (s, 1H), 7.10 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.80−6.55 (m, 3H), 5.86 (s, 1H), 3.84−3.79 (m, 2H), 3.49−3.46 (m, 2H), 3.38−3.37 (m, 2H), 3.00−2.97 (m, 2H), 1.84−1.80 (m, 2H), 1.68−1.62 (m, 3H), 1.44−1.37 (m, 1H).

Synthesis of (E)-2-((3-(4-(Dimethylamino)but-2-enamido)-phenyl)(2-(piperidin-1-yl)ethoxy)methyl)thieno[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylic Acid (N71).

To a solution of (E)-4-(dimethylamino)but-2-enoic acid hydrochloride (28.4 mg, 0.171 mmol, 1 equiv) in DMF (2 mL), DIPEA (0.090 mL, 0.514 mmol, 3 equiv) was added, followed by HATU (65.1 mg, 0.171 mmol, 1 equiv), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 min, then 2-((3-aminophenyl)(2-(piperidin-1-yl)ethoxy)methyl)thieno[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylic acid·TFA (90 mg, 0.171 mmol, 1 equiv) was added and the reaction was stirred for 1 h at room temperature. The mixture was concentrated, dissolved in a small amount of DMSO, and purified on HPLC to obtain N71 as the TFA salt. LC−MS retention time: t1 = 2.48 min; t2 = 2.77 min; LC−MS M + H = 523. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.40 (s, 1H), 9.82 (br s, 1H), 9.24 (br s, 1H), 8.83 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (s, 1H), 7.83−7.79 (d, J = 4.8 Hz 1H), 7.63 (s, 1H), 7.61−7.59 (m, 1H), 7.43−7.39 (t, J =7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.31−7.29 (m, 1H), 6.75−6.68 (m, 1H), 6.44−6.41 (m, 1H), 6.05 (s, 1H), 3.92−3.79 (m, 5H), 3.52−3.46 (m, 2H), 3.05−2.95 (m, 3H), 2.78 (s, 6H), 1.84−1.81 (m, 2H), 1.72−1.62 (m, 2H), 1.44−1.36 (m, 2H).

Synthesis of Isopropyl 2-((3-Aminophenyl)(2-(piperidin-1-yl)-ethoxy)methyl)thieno[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylate (SI-5).

To a solution of 2-((3-aminophenyl)(2-(piperidin-1-yl)ethoxy)methyl)-thieno[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylic acid (0.06g, 0.146 mmol, 1 equiv) in isopropanol (1 mL), TMS-Cl (0.186 mL, 1.458 mmol, 10 equiv) was added, and the reaction was heated to 100 °C in a microwave vial for 30 min. The reaction was then concentrated in vacuo, and the residue was purified on HPLC to provide the isopropyl 2-((3-aminophenyl)(2-(piperidin-1-yl)ethoxy)methyl)thieno[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylate SI-5 as the TFA salt. LC−MS retention time: t1 = 2.94 min; t2 = 3.65 min; LC−MS M + H = 454. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.18 (s, 1H), 8.83 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (s, 1H), 7.12 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 6.84−6.61 (m, 3H), 5.88 (s, 1H), 5.27−5.21 (m, 1H), 4.4−3.9 (br s, 2H), 3.87−3.76 (qt, J = 11.2, 4.9 Hz, 2H), 3.50−3.47 (m, 2H), 3.40−3.37 (m, 2H), 3.03−2.95 (m, 2H), 1.85−1.78 (m, 2H), 1.68 (m, 3H), 1.71−1.65 (m, 1H), 1.38 (dd, J = 6.3, 1.3 Hz, 6H).

Synthesis of Isopropyl (E)-2-((3-(4-(Dimethylamino)but-2-enamido)phenyl)(2-(piperidin-1-yl)ethoxy)methyl)thieno[3,2-b]-pyridine-7-carboxylate (N73).

To a solution of (E)-4-(dimethylamino)but-2-enoic acid hydrochloride (26.3 mg, 0.159 mmol, 1 equiv) in DMF (2 mL), DIPEA (0.055 mL, 0.317 mmol, 2 equiv) was added, followed by HATU (60.3 mg, 0.159 mmol, 1 equiv), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 min. Then isopropyl 2-((3-aminophenyl)(2-(piperidin-1-yl)ethoxy)methyl)-thieno[3,2-b]pyridine-7-carboxylate (90 mg, 0.159 mmol, 1 equiv) was added, and the reaction was stirred for 1 h at room temperature. The mixture was concentrated, dissolved in a small amount of DMSO, and purified on HPLC to obtain N73 as the TFA salt. LC−MS retention time: t1 = 2.91 min; t2 = 4.17 min; LC−MS M + H = 565; (M + 2H)/2 = 283. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.42 (s, 1H), 9.96 (br s, 1H), 9.35 (br s, 1H), 8.85 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (t, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.83 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (m, 2H), 7.41 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 6.73 (dq, J = 14.8, 7.7, 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.43 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 6.06 (s, 1H), 5.27−5.20 (m, 1H), 3.96−3.91 (m, 2H), 3.90−3.80 (m, 2H), 3.54−3.47 (m, 2H), 3.42−3.37 (m, 2H), 3.08− 2.95 (m, 2H), 2.79 (s, 6H), 1.87−1.78 (m, 2H), 1.74−1.62 (m, 3H), 1.46−1.31 (m, 7H).

Constructs.

The KDM5 family is unique among histone demethylases in that each member contains an atypical split catalytic domain with insertion of a DNA-binding ARID and histone-interacting PHD1 domain separating it into two segments. Deletion of internal ARID and PHD1 domains (ΔAP) generated KDM5A(1−739)ΔAP and KDM5B(1−755)ΔAP, used for enzyme activity studies, and KDM5A(1−588)ΔAP, used for compound binding assays and structural studies.27

Promega Succinate-Glo Demethylase Assay.

The inhibition of KDM5A(1−739)ΔAP by compounds N49, N70, and N71 was obtained using the Promega Succinate-Glo kit. The demethylase reaction was conducted for 10 min with 0.8 μM KDM5A preincubated for 20 min with a 2=fold serial dilution of compound. The reaction was initiated by the addition of αKG (10, 100, or 1000 μM) and substrate peptide H3(1−24)K4me3 (60 μM) in the presence of 10 μM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2, 100 μM ascorbic acid, 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, and 5% DMSO at ambient temperature (n = 3). The reaction was terminated by the addition of equal volume of Succinate Detection Reagent I (SDI), supplied by the manufacture, followed by 1 h incubation. After the incubation period with SDI the second reagent SDII was added to a final ratio of 1:2 (SDI/SDII). A 15 μL aliquot of the final solution was loaded into each well of a 384 low volume white plate. Data was collected using a BioTek Synergy 4, and IC50 values were fitted using a four-parameter model in GraphPad Prism 7.

PAMPA Permeability Assay.

The stirring double-sink PAMPA method patented by pION Inc. (Billerica, MA) was employed to determine the permeability of compounds via PAMPA passive diffusion. The PAMPA lipid membrane consisted of an artificial membrane of a proprietary lipid mixture and dodecane (Pion Inc.), optimized to predict gastrointestinal tract (GIT) passive diffusion permeability, and was immobilized on a plastic matrix of a 96-well “donor” filter plate placed above a 96-well “acceptor” plate. A pH 7.4 solution was used in both donor and acceptor wells. The test articles, stocked in 10 mM DMSO solutions, were diluted to 0.05 mM in aqueous buffer (pH 7.4), and the concentration of DMSO was 0.5% in the final solution. During the 30 min permeation period at room temperature, the test samples in the donor compartment were stirred using the Gutbox technology (Pion Inc.) to reduce the unstirred water layer. The test article concentrations in the donor and acceptor compartments were measured using an UV plate reader (Nano Quant, Infinite 200 PRO, Tecan Inc., Mannedorf, Switzerland). Permeability calculations were performed using Pion Inc. software and were expressed in units of 10−6 cm s−1. Compounds with values >100 are considered to have high permeability, compounds with values <100 but >10 are considered moderate permeability, and compounds with values <10 are considered to have low permeability.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Institutes of Health (NIH), under NCI Chemical Biology Consortium Contract No. HHSN261200800001E (to H.F.), NIH grant GM114306 and Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) grant RR160029 (to X.C.). The mass spectrometry experiments were performed by David Hawke of the Proteomics and Metabolomics Facility (at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center), supported in part by CPRIT (RP130397) and NIH (1S10OD012304–01 and P30CA016672). The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The Department of Biochemistry of Emory University School of Medicine and CPRIT supported the use of the Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team (SERCAT) synchrotron beamlines at the Advanced Photon Source of Argonne National Laboratory. We thank Qin Yan of Yale University, Anthony Welch and Dane Liston of NCI, and Andrew Flint of Leidos Biomedical Research, Inc. (which operates the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research) for discussion throughout this project.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- αKG

α-ketoglutarate

- KDM5A

histone lysine demethylase 5A

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01219.

Molecular formula strings (CSV)

Figures S1−S5 and Table S1 (PDF)

Accession Codes

The atomic coordinates and structure factors of KDM5A in complex with GSK-J1 (6DQ4), N43 (6DQ5), N44 (6DQ6), N49 (6DQ8), N70 (6DQA), and N71 (6DQB) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Gasser SM; Li E Epigenetics and disease: pharmaceutical opportunities. Appl. Clin. Genet 2011, 67, 67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Black JC; Van Rechem C; Whetstine JR Histone lysine methylation dynamics: establishment, regulation, and biological impact. Mol. Cell 2012, 48, 491–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Li S; Shen L; Chen KN Association between H3K4 methylation and cancer prognosis: A meta-analysis. Thorac. Cancer 2018, 9, 794–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Shi Y; Lan F; Matson C; Mulligan P; Whetstine JR; Cole PA; Casero RA; Shi Y Histone demethylation mediated by the nuclear amine oxidase homolog LSD1. Cell 2004, 119, 941–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Shi YG; Tsukada Y The discovery of histone demethylases. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol 2013, 5, a022335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Jambhekar A; Anastas JN; Shi Y Histone lysine demethylase inhibitors. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med 2017, 7, a026484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Zheng YC; Ma J; Wang Z; Li J; Jiang B; Zhou W; Shi X; Wang X; Zhao W; Liu HM A systematic review of histone lysine-specific demethylase 1 and Its inhibitors. Med. Res. Rev 2015, 35, 1032–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Christensen J; Agger K; Cloos PA; Pasini D; Rose S; Sennels L; Rappsilber J; Hansen KH; Salcini AE; Helin K RBP2 belongs to a family of demethylases, specific for tri-and dimethylated lysine 4 on histone 3. Cell 2007, 128, 1063–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Blair LP; Cao J; Zou MR; Sayegh J; Yan Q Epigenetic regulation by lysine demethylase 5 (KDM5) enzymes in cancer. Cancers 2011, 3, 1383–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Rasmussen PB; Staller P The KDM5 family of histone demethylases as targets in oncology drug discovery. Epigenomics 2014, 6, 277–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Harmeyer KM; Facompre ND; Herlyn M; Basu D JARID1 histone demethylases: emerging targets in cancer. Trends Cancer 2017, 3, 713–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Shokri G; Doudi S; Fathi-Roudsari M; Kouhkan F; Sanati MH Targeting histone demethylases KDM5A and KDM5B in AML cancer cells: A comparative view. Leuk. Res 2018, 68, 105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Liang J; Labadie S; Zhang B; Ortwine DF; Patel S; Vinogradova M; Kiefer JR; Mauer T; Gehling VS; Harmange JC; Cummings R; Lai T; Liao J; Zheng X; Liu Y; Gustafson A; Van der Porten E; Mao W; Liederer BM; Deshmukh G; An L; Ran Y; Classon M; Trojer P; Dragovich PS; Murray L From a novel HTS hit to potent, selective, and orally bioavailable KDM5 inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2017, 27, 2974–2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Horton JR; Liu X; Wu L; Zhang K; Shanks J; Zhang X; Rai G; Mott BT; Jansen DJ; Kales SC; Henderson MJ; Pohida K; Fang Y; Hu X; Jadhav A; Maloney DJ; Hall MD; Simeonov A; Fu H; Vertino PM; Yan Q; Cheng X Insights into the action of inhibitor enantiomers against histone lysine demethylase 5A. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61, 3193–3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Vinogradova M; Gehling VS; Gustafson A; Arora S; Tindell CA; Wilson C; Williamson KE; Guler GD; Gangurde P; Manieri W; Busby J; Flynn EM; Lan F; Kim HJ; Odate S; Cochran AG; Liu Y; Wongchenko M; Yang Y; Cheung TK; Maile TM; Lau T; Costa M; Hegde GV; Jackson E; Pitti R; Arnott D; Bailey C; Bellon S; Cummings RT; Albrecht BK; Harmange JC; Kiefer JR; Trojer P; Classon M An inhibitor of KDM5 demethylases reduces survival of drug-tolerant cancer cells. Nat. Chem. Biol 2016, 12, 531–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Tumber A; Nuzzi A; Hookway ES; Hatch SB; Velupillai S; Johansson C; Kawamura A; Savitsky P; Yapp C; Szykowska A; Wu N; Bountra C; Strain-Damerell C; Burgess-Brown NA; Ruda GF; Fedorov O; Munro S; England KS; Nowak RP; Schofield CJ; La Thangue NB; Pawlyn C; Davies F; Morgan G; Athanasou N; Muller S; Oppermann U; Brennan PE Potent and selective KDM5 inhibitor stops cellular demethylation of H3K4me3 at transcription start sites and proliferation of MM1S myeloma cells. Cell Chem. Biol 2017, 24, 371–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Horton JR; Liu X; Gale M; Wu L; Shanks JR; Zhang X; Webber PJ; Bell JS; Kales SC; Mott BT; Rai G; Jansen DJ; Henderson MJ; Urban DJ; Hall MD; Simeonov A; Maloney DJ; Johns MA; Fu H; Jadhav A; Vertino PM; Yan Q; Cheng X Structural basis for KDM5A histone lysine demethylase inhibition by diverse compounds. Cell Chem. Biol 2016, 23, 769–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Johansson C; Velupillai S; Tumber A; Szykowska A; Hookway ES; Nowak RP; Strain-Damerell C; Gileadi C; Philpott M; Burgess-Brown N; Wu N; Kopec J; Nuzzi A; Steuber H; Egner U; Badock V; Munro S; LaThangue NB; Westaway S; Brown J; Athanasou N; Prinjha R; Brennan PE; Oppermann U Structural analysis of human KDM5B guides histone demethylase inhibitor development. Nat. Chem. Biol 2016, 12, 539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Herr CQ; Hausinger RP Amazing diversity in biochemical roles of Fe(II)/2-oxoglutarate oxygenases. Trends Biochem. Sci 2018, 43, 517–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kaniskan HU; Martini ML; Jin J Inhibitors of protein methyltransferases and demethylases. Chem. Rev 2018, 118, 989–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Johansson MH Reversible Michael additions: covalent inhibitors and prodrugs. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem 2012, 12, 1330–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Awoonor-Williams E; Walsh AG; Rowley CN Modeling covalent-modifier drugs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2017, 1865, 1664–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Bradshaw JM; McFarland JM; Paavilainen VO; Bisconte A; Tam D; Phan VT; Romanov S; Finkle D; Shu J; Patel V; Ton T; Li X; Loughhead DG; Nunn PA; Karr DE; Gerritsen ME; Funk JO; Owens TD; Verner E; Brameld KA; Hill RJ; Goldstein DM; Taunton J Prolonged and tunable residence time using reversible covalent kinase inhibitors. Nat. Chem. Biol 2015, 11, 525–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Smith GA; Uchida K; Weiss A; Taunton J Essential biphasic role for JAK3 catalytic activity in IL-2 receptor signaling. Nat. Chem. Biol 2016, 12, 373–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Rodriguez-Molina JB; Tseng SC; Simonett SP; Taunton J; Ansari AZ Engineered covalent inactivation of TFIIH-kinase reveals an elongation checkpoint and results in widespread mRNA stabilization. Mol. Cell 2016, 63, 433–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Butler KV; Ma A; Yu W; Li F; Tempel W; Babault N; Pittella-Silva F; Shao J; Wang J; Luo M; Vedadi M; Brown PJ; Arrowsmith CH; Jin J Structure-based design of a covalent inhibitor of the SET domain-containing protein 8 (SETD8) lysine methyltransferase. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 9881–9889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Horton JR; Engstrom A; Zoeller EL; Liu X; Shanks JR; Zhang X; Johns MA; Vertino PM; Fu H; Cheng X Characterization of a linked jumonji domain of the KDM5/JARID1 family of histone H3 lysine 4 demethylases. J. Biol. Chem 2016, 291, 2631–2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kruidenier L; Chung CW; Cheng Z; Liddle J; Che K; Joberty G; Bantscheff M; Bountra C; Bridges A; Diallo H; Eberhard D; Hutchinson S; Jones E; Katso R; Leveridge M; Mander PK; Mosley J; Ramirez-Molina C; Rowland P; Schofield CJ; Sheppard RJ; Smith JE; Swales C; Tanner R; Thomas P; Tumber A; Drewes G; Oppermann U; Patel DJ; Lee K; Wilson DM A selective jumonji H3K27 demethylase inhibitor modulates the proinflammatory macrophage response. Nature 2012, 488, 404–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Heinemann B; Nielsen JM; Hudlebusch HR; Lees MJ; Larsen DV; Boesen T; Labelle M; Gerlach LO; Birk P; Helin K Inhibition of demethylases by GSK-J1/J4. Nature 2014, 514, E1–E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Cee VJ; Volak LP; Chen Y; Bartberger MD; Tegley C; Arvedson T; McCarter J; Tasker AS; Fotsch C Systematic study of the glutathione (GSH) reactivity of N-arylacrylamides: 1. Effects of aryl substitution. J. Med. Chem 2015, 58, 9171–9178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Nicolaou KC; Estrada AA; Zak M; Lee SH; Safina BS A mild and selective method for the hydrolysis of esters with trimethyltin hydroxide. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2005, 44, 1378–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Horowitz S; Trievel RC Carbon-oxygen hydrogen bonding in biological structure and function. J. Biol. Chem 2012, 287, 41576–41582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Deeks ED; Keating GM Afatinib in advanced NSCLC: a profile of its use. Drugs Ther Perspect 2018, 34, 89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Solca F; Dahl G; Zoephel A; Bader G; Sanderson M; Klein C; Kraemer O; Himmelsbach F; Haaksma E; Adolf GR Target binding properties and cellular activity of afatinib (BIBW 2992), an irreversible ErbB family blocker. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 2012, 343, 342–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Alves J; Vidugiris G; Goueli SA; Zegzouti H Bioluminescent high-throughput succinate detection method for monitoring the activity of JMJC histone demethylases and Fe(II)/2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. SLAS Discov 2018, 23, 242–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Silverman RB Mechanism-based enzyme inactivators. Methods Enzymol. 1995, 249, 240–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Sun H; Nguyen K; Kerns E; Yan Z; Yu KR; Shah P; Jadhav A; Xu X Highly predictive and interpretable models for PAMPA permeability. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2017, 25, 1266–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Wu L; Cao J; Cai WL; Lang SM; Horton JR; Jansen DJ; Liu ZZ; Chen JF; Zhang M; Mott BT; Pohida K; Rai G; Kales SC; Henderson MJ; Hu X; Jadhav A; Maloney DJ; Simeonov A; Zhu S; Iwasaki A; Hall MD; Cheng X; Shadel GS; Yan Q KDM5 histone demethylases repress immune response via suppression of STING. PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e2006134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Wright SW Preparation of 2-, 4-, 5-, and 6-aminonicotinic acid tert-butyl esters. J. Heterocyclic Chem. 2012, 49, 442–445. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Wang XJ; Sun X; Zhang L; Xu Y; Krishnamurthy D; Senanayake CH Noncryogenic I/Br-Mg exchange of aromatic halides bearing sensitive functional groups using i-PrMgCl-bis[2-(N,N-dimethylamino)ethyl] ether complexes. Org. Lett 2006, 8, 305–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Horton JR; Gale M; Yan Q; Cheng X The molecular basis of histone demethylation In DNA and Histone Methylation as Cancer Targets; Kaneda A, Tsukada Y.-i., Eds.; Cancer Drug Discovery and Development, 2017; pp 151–219. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Lin W; Cao J; Liu J; Beshiri ML; Fujiwara Y; Francis J; Cherniack AD; Geisen C; Blair LP; Zou MR; Shen X; Kawamori D; Liu Z; Grisanzio C; Watanabe H; Minamishima YA; Zhang Q; Kulkarni RN; Signoretti S; Rodig SJ; Bronson RT; Orkin SH; Tuck DP; Benevolenskaya EV; Meyerson M; Kaelin WG Jr.; Yan Q Loss of the retinoblastoma binding protein 2 (RBP2) histone demethylase suppresses tumorigenesis in mice lacking Rb1 or Men1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2011, 108, 13379–13386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Cao J; Liu Z; Cheung WK; Zhao M; Chen SY; Chan SW; Booth CJ; Nguyen DX; Yan Q Histone demethylase RBP2 is critical for breast cancer progression and metastasis. Cell Rep. 2014, 6, 868–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Dalvi MP; Wang L; Zhong R; Kollipara RK; Park H; Bayo J; Yenerall P; Zhou Y; Timmons BC; Rodriguez-Canales J; Behrens C; Mino B; Villalobos P; Parra ER; Suraokar M; Pataer A; Swisher SG; Kalhor N; Bhanu NV; Garcia BA; Heymach JV; Coombes K; Xie Y; Girard L; Gazdar AF; Kittler R; Wistuba II; Minna JD; Martinez ED Taxane-platin-resistant lung cancers co-develop hypersensitivity to JumonjiC demethylase inhibitors. Cell Rep. 2017, 19, 1669–1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Roesch A; Vultur A; Bogeski I; Wang H; Zimmermann KM; Speicher D; Korbel C; Laschke MW; Gimotty PA; Philipp SE; Krause E; Patzold S; Villanueva J; Krepler C; Fukunaga-Kalabis M; Hoth M; Bastian BC; Vogt T; Herlyn M Overcoming intrinsic multidrug resistance in melanoma by blocking the mitochondrial respiratory chain of slow-cycling JARID1B(high) cells. Cancer Cell 2013, 23, 811–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Sharma SV; Lee DY; Li B; Quinlan MP; Takahashi F; Maheswaran S; McDermott U; Azizian N; Zou L; Fischbach MA; Wong KK; Brandstetter K; Wittner B; Ramaswamy S; Classon M; Settleman J A chromatin-mediated reversible drug-tolerant state in cancer cell subpopulations. Cell 2010, 141, 69–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Westaway SM; Preston AG; Barker MD; Brown F; Brown JA; Campbell M; Chung CW; Drewes G; Eagle R; Garton N; Gordon L; Haslam C; Hayhow TG; Humphreys PG; Joberty G; Katso R; Kruidenier L; Leveridge M; Pemberton M; Rioja I; Seal GA; Shipley T; Singh O; Suckling CJ; Taylor J; Thomas P; Wilson DM; Lee K; Prinjha RK Cell penetrant inhibitors of the KDM4 and KDM5 families of histone lysine demethylases. 2. Pyrido[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4(3H)-one derivatives. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 1370–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Westaway SM; Preston AG; Barker MD; Brown F; Brown JA; Campbell M; Chung CW; Diallo H; Douault C; Drewes G; Eagle R; Gordon L; Haslam C; Hayhow TG; Humphreys PG; Joberty G; Katso R; Kruidenier L; Leveridge M; Liddle J; Mosley J; Muelbaier M; Randle R; Rioja I; Rueger A; Seal GA; Sheppard RJ; Singh O; Taylor J; Thomas P; Thomson D; Wilson DM; Lee K; Prinjha RK Cell penetrant inhibitors of the KDM4 and KDM5 families of histone lysine demethylases. 1. 3-Amino-4-pyridine carboxylate derivatives. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 1357–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Watanuki Z; Kosai H; Osanai N; Ogama N; Mochizuki M; Tamai K; Yamaguchi K; Satoh K; Fukuhara T; Maemondo M; Ichinose M; Nukiwa T; Tanaka N Synergistic cytotoxicity of afatinib and cetuximab against EGFR T790M involves Rab11-dependent EGFR recycling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2014, 455, 269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Castillo-Aguilera O; Depreux P; Halby L; Arimondo PB; Goossens L DNA methylation targeting: the DNMT/HMT crosstalk challenge. Biomolecules 2017, 7, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Patel K; Dickson J; Din S; Macleod K; Jodrell D; Ramsahoye B Targeting of 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine residues by chromatin-associated DNMT1 induces proteasomal degradation of the free enzyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 4313–4324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Murai J; Huang SY; Das BB; Renaud A; Zhang Y; Doroshow JH; Ji J; Takeda S; Pommier Y Trapping of PARP1 and PARP2 by clinical PARP inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 5588–5599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Muvarak NE; Chowdhury K; Xia L; Robert C; Choi EY; Cai Y; Bellani M; Zou Y; Singh ZN; Duong VH; Rutherford T; Nagaria P; Bentzen SM; Seidman MM; Baer MR; Lapidus RG; Baylin SB; Rassool FV Enhancing the cytotoxic effects of PARP inhibitors with DNA demethylating agents - A potential therapy for cancer. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 637–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.