Abstract

Background:

Biliary tract cancers (BTC) are rare but deadly cancers [gallbladder (GBC), intrahepatic (ICC) and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas (ECC), and ampulla of Vater (AVC)]. A recent U.S. study reported increasing GBC incidence among people <45 years and blacks, however it did not examine trends for other biliary tract sites.

Methods:

We characterized demographic differences in biliary tract cancer incidence rates and time trends by anatomic site. We used population-based North American Association of Central Cancer Registries data to calculate age-adjusted incidence rates, incidence rate ratios (IRRs), and estimated annual percent change per year (eAPC) for 1999–2013 by site and demographic group. For sites with significant differences in eAPC by age group, we compared IRRs by age group.

Results:

GBC incidence rates declined among women (eAPC=−0.5%/year, P=0.01) and all racial/ethnic groups, except non-Hispanic blacks, among whom rates increased (1.8%/year, P<0.0001). While GBC rates increased among 18–44-year-olds (eAPC=1.8%/year, P=0.01), they decreased among people ≥45 years (−0.4 %/year, P=0.009). Sex (P<0.0001) and racial/ethnic differences (P=0.003 to 0.02) in GBC incidence were larger for younger than older people. During this period, ICC (eAPC=3.2%/year, P<0.0001) and ECC (1.8%/year, P=0.001) rates steadily increased across sex and racial/ethnic groups. While AVC incidence rates increased among younger (eAPC=1.8%/year, P=0.03) but not older adults (−0.20 %/year, P=0.30), sex and racial/ethnic IRRs did not differ by age.

Conclusions:

We identified differential patterns of BTC rates and temporal trends by anatomic site and demographic groups. These findings highlight the need for large pooling projects to evaluate BTC risk factors by anatomic site.

Keywords: Biliary Tract, Cancer, Incidence, Trends, United States

Precis:

Significant and novel variations in biliary tract cancer incidence rates and trends were identified across the anatomic sites by demographic group among adults in the United States between 1999 and 2013. Differences in sex- and race/ethnicity-specific gallbladder cancer incidence rate ratios were larger among younger than older adults, which may reflect underlying differences in the prevalence of and trends in risk factors by demographic group.

INTRODUCTION

Biliary tract cancers, including gallbladder cancer (GBC), intrahepatic (ICC) and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas (ECC), and ampulla of Vater cancer (AVC), are rare with poor survival rates generally resulting from a late stage at diagnosis.1–3 Identification of groups at higher risk for these malignancies and estimation of temporal changes in rates are critical for clinical and public health management and for gaining potential insight into cancer etiology. While they are known to vary by anatomic site, trends in biliary tract cancers rates and associated demographic factors have not been well-explored, and their etiology is poorly understood.

Because of their rarity, most studies have either examined biliary tract cancers at all anatomic sites combined or have focused on GBC, the most common biliary tract cancer worldwide. Globally, GBC incidence rates are higher among women who are also at increased risk of developing gallstones and cholecystitis, the primary GBC risk factors, as well as among indigenous populations.4, 5 Of concern, a recent publication on GBC incidence rates in the United States reported increasing rates among blacks and people under the age of 45 during 1999–2011 while rates in other racial/ethnic groups and among those ≥45 years either declined or remained stable.6

Therefore, the objectives of this study were to examine variation in biliary tract cancer incidence rates and trends over time in the United States by anatomic site and demographic factors with a focus on disparate trends by age.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Data Source:

Data on cancer incidence were obtained from the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR) Cancer in North America (CiNA) deluxe dataset that combines cancer data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR), and Canadian cancer registries.7 Data from 38 state-based U.S. registries that 1) consented to participate in this study, 2) had complete data from 1999 to 2013, and 3) met gold or silver certification for completeness, accuracy, and timeliness of data, were used in the analysis of this study. These registries included: Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming. They represent approximately 85% of the United States population.

Cancer Classifications:

Anatomic site was classified using the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology third edition (ICD-O-3) topography definition codes: GBC (C23.9), ICC (C22.1), ECC (C24.0), and AVC (C24.1).8 As per previously published histological classification guidelines,9 both intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas were restricted to tumors with the following ICD-O-3 morphology codes: 8032, 8033, 8070 8071, 8140, 8160, 8260, 8480, 8481, 8490, and 8560. Accordingly, tumors with ICD-O-3 liver topography site code (C22.0) and cholangiocarcinoma histology codes were coded as ICC. Klatskin tumors at the hilum of the liver (histology code 8162/3) were classified as ECC. Analyses were limited to tumors exhibiting malignant behavior.

Statistical Analysis:

Age-adjusted incidence rates (AAIRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were reported by anatomic site per 1,000,000 person-years standardized by age to the 2000 United States standard population (Census P25–1130) using SEER*Stat.10 Rates were stratified by gender, race/ethnicity [non-Hispanic white (white), non-Hispanic black (black), Hispanic, and non-Hispanic other (other)], and age group (18 to 44, 45 to 54, 55 to 64, 65 to 74, 75 to 84, and ≥85 years). Rates based on ≤15 cases were suppressed in accordance with NAACCR policies. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and 95% CIs were calculated for female-to-male, black-to-white, Hispanic-to-white, and other-to-white comparisons of AAIRs, stratified by anatomic site. Similarly, age group comparisons were made referent to rates among 18 to 44-year-olds.

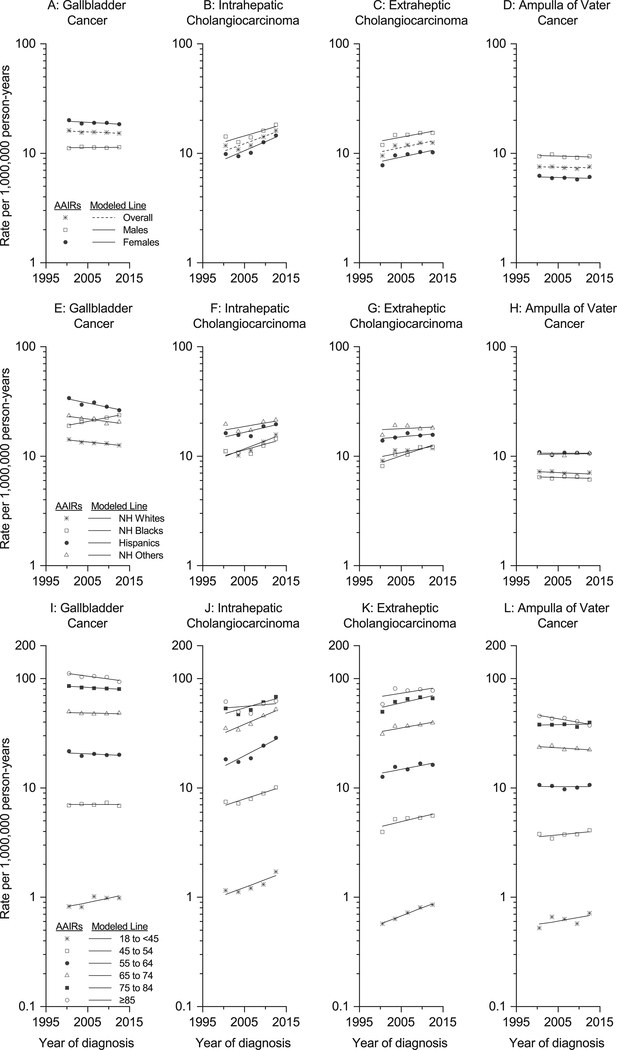

AAIRs for three-year periods were plotted for each anatomic site stratified by sex, race/ethnicity, and age group. Estimated annual percent changes (eAPCs) and 95% CIs for single years between 1999 and 2013 were calculated using Joinpoint using a linear model (zero joinpoints) by the weighted least squares method overall, and by sex, race/ethnicity, and age group.11, 12 Using a linear model allowed for comparison across anatomic sites within the biliary tract. To visually display the linear trends assumed in our models, we have graphed the fitted linear trends in Figure 1A-1L. Within each anatomic site, we used two-tailed tests implemented in Joinpoint to examine whether eAPCs were significantly different from 0% and to compare whether trends were parallel by sex (referent to males), race/ethnicity (referent to whites), and dichotomous age group (referent to ≥45-year-olds).

Figure 1:

Abbreviations: NH (non-Hispanic)

Age-adjusted rates of biliary tract cancers per 1,000,000 person-years in the United States in three-year periods between 1999 and 2013 plotted at the mid-point for each period by cancer site and sex (1A to 1D), race/ethnicity (1E to 1H), and age group (1I to 1L). The fitted linear trends were plotted through age-adjusted rates of biliary tract cancers per 1,000,000 person-years in the United States in three-year periods between 1999 and 2013 modeled in Joinpoint specifying zero joinpoints. Source: Thirty-eight National Program of Cancer Registries and Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registries that met data quality standards of the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR) for the period 1999–2013

For anatomic sites with eAPCs that were significantly different by age group, IRRs were compared by sex and race/ethnicity to determine whether demographic patterns differed among younger and older biliary tract cancer cases. We used a Wald test to determine if the squared difference between the log-transformed IRR estimates was different from zero. To compute the variance for the difference of the log-IRRs we used that the IRRs are independent for the dichotomous age groups for a given anatomic site, and the delta method.

Analyses were carried out using SEER*Stat (version 8.3.4)10 and Joinpoint (version 4.3.1.0, Information Management Services, Inc., Calverton, Maryland) software 11, 12.

RESULTS

Site-specific Incidence Rates Overall and by Demographic Factors:

Between 1999 and 2013 in 38 US states, 96,769 biliary tract cancers were diagnosed in over 2.7 billion person-years, including 44,470 GBCs, 37,685 ICCs, 33,380 ECCs, and 21,234 AVCs (Table 1). Age-adjusted incidence rates were highest for GBC (15.6 per 1,000,000 person-years) and lowest for AVC (7.4 per 1,000,000 person-years). While GBC incidence rates were higher for females [IRR (95% CI): 1.7 (1.6–1.7)], rates of ICC, ECC, and AVC were higher for males (Table 1; Figures 1A to 1D). GBC incidence rates were also highest among Hispanics (73.5 per 1,000,000 person-years), followed by blacks (53.8 per 1,000,000 person-years) and people of other race/ethnicity (53.4 per 1,000,000 person-years) (Table 1; Figure 1E). Hispanics and people of other race/ethnicity, but not blacks, had higher rates than whites for ICC, ECC, and AVC (Table 1; Figures 1F to 1H). With increasing age, rates steadily rose across all four sites with the highest rates observed among people ≥85 years-old and far lower rates among 18 to 44-year-olds than ≥45-year-olds (Table 1; Figure 1I to 1L).

Table 1:

Biliary tract cancer age-adjusted incidence rates per 1,000,000 person-years by site and sex, race/ethnicity, and age group in the United States, NAACCR, 1999–2013a,b,c

| DemographicVariable | Gallbladder Cancer | Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma | Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma | Ampulla of Vater Cancer | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases N | AAIR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | Cases N | AAIR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | Cases N | AAIR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | Cases N | AAIR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | 13,759 | 11.3 (11.1–11.5) | 1.0 | 19,438 | 15.2 (15.0–15.4) | 1.0 | 17,779 | 14.5 (14.3–14.7) | 1.0 | 11,588 | 9.4 (9.2–9.5) | 1.0 |

| Female | 30,711 | 19.0 (18.8–19.2) | 1.7 (1.6–1.7) | 18,247 | 11.4 (11.3–11.6) | 0.8 (0.7–0.8) | 15,601 | 9.6 (9.4–9.7) | 0.7 (0.6–0.7) | 9,646 | 6.0 (5.9–6.1) | 0.6 (0.6–0.7) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 29,191 | 33.8 (33.4–34.2) | 1.0 | 26,085 | 30.2 (29.9–30.6) | 1.0 | 24,198 | 28.0 (27.7–28.4) | 1.0 | 15,092 | 17.5 (17.2–17.8) | 1.0 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 4,700 | 53.8 (52.2–55.4) | 1.6 (1.5–1.6) | 2,661 | 28.8 (27.7–30.0) | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 2,351 | 26.7 (25.6–27.8) | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 1,367 | 15.4 (14.6–16.2) | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) |

| Hispanic | 5,659 | 73.5 (71.6–75.5) | 2.2 (2.1–2.2) | 3,447 | 43.4 (41.9–44.9) | 1.4 (1.4–1.5) | 2,939 | 39.0 (37.5–40.5) | 1.4 (1.3–1.4) | 2,067 | 26.2 (25.1–27.4) | 1.5 (1.4–1.6) |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 2,319 | 53.4 (51.2–55.7) | 1.6 (1.5–1.6) | 2,149 | 47.0 (44.9–49.1) | 1.6 (1.5–1.6) | 1,983 | 45.9 (43.8–48.0) | 1.6 (1.6–1.7) | 1,155 | 25.6 (24.1–27.1) | 1.5 (1.4–1.6) |

| Age Group (years) | ||||||||||||

| 18 to 44 | 1,205 | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) | 1.0 | 1,707 | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | 1.0 | 939 | 0.7 (0.7–0.8) | 1.0 | 811 | 0.6 (0.02–0.6) | 1.0 |

| 45 to 54 | 3,722 | 7.1 (6.8–7.3) | 7.7 (7.2–8.2) | 4,438 | 8.4 (8.2–8.7) | 6.5 (6.1–6.9) | 2,697 | 5.1 (4.9–5.3) | 7.1 (6.6–7.7) | 1,995 | 3.8 (3.6–3.9) | 6.1 (5.6–6.6) |

| 55 to 64 | 7,928 | 20.3 (19.9–20.8) | 22.1 (20.8–23.5) | 8,644 | 22.1 (21.7–22.6) | 17.1 (16.2–18.0) | 5,999 | 15.4 (15.0–15.8) | 21.6 (20.1–23.1) | 4,015 | 10.3 (10.0–10.6) | 16.6 (15.4–17.9) |

| 65 to 74 | 11,936 | 48.3 (47.4–49.1) | 52.4 (49.4–55.7) | 10,318 | 41.6 (40.8–42.4) | 32.1 (60.5–33.8) | 9,020 | 36.5 (35.7–37.2) | 51.1 (47.7–54.7) | 5,696 | 23.0 (22.4–23.6) | 37.1 (34.5–40.0) |

| 75 to 84 | 13,346 | 82.4 (81.0–83.8) | 89.5 (84.4–95.0) | 9,104 | 56.4 (55.2–57.6) | 43.5 (41.3–45.8) | 10,072 | 62.1 (30.9–63.3) | 87.0 (81.4–93.1) | 6,147 | 38.0 (37.0–38.9) | 61.3 (56.9–66.0) |

| ≥85 | 6,333 | 102.8 (100.2–105.3) | 111.3 (105.0–118.8) | 3,474 | 56.4 (54.5–58.3) | 43.5 (41.0–46.1) | 4,653 | 75.5 (73.3–77.7) | 105.8 (98.5–113.6) | 2,570 | 41.7 (40.1–43.3) | 67.3 (62.1–72.9) |

| Overall | 44,470 | 15.6 (15.4–15.7) | N/A | 37,685 | 13.1 (13.0–13.2) | N/A | 33,380 | 11.7 (11.6–11.8) | N/A | 21,234 | 7.4 (7.3–7.5) | N/A |

Abbreviations: AAIR (age adjusted incidence rate), CI (confidence interval), IRR (incidence rate ratio), N/A (not applicable), NAACCR (North American Association of Center Cancer Registries)

Source: Thirty-eight National Program of Cancer Registries and Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registries that met data quality standards of the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR) for the period 1999–2013.

AAIRs are presented as per 1,000,000 person-years and age-adjusted with the 2000 U.S. population.

Rates not shown when based on case counts <15.

Site-Specific Incidence Trends Overall and by Demographic Factors:

During the 1999–2013 period, GBC age-adjusted incidence rates significantly decreased by 0.4%/year (P=0.02) (Supplementary Table S1). Rates for both ICC and ECC increased by 3.2 and 1.8%/year, respectively (P<0.0001 for ICC and 0.001 for ECC). AVC rates did not change (eAPC=0%/year, P=0.60). Rates in GBC incidence rates did not change for males (eAPC=0.1%/year, P=0.66) but decreased for females (eAPC=−0.5%/year, P=0.01), though the difference in trends was not statistically significant (P for parallelism=0.17) (Table 2). GBC incidence rates rose for blacks (1.8%/year, P<0.0001) but declined for whites (−0.9%/year, P=0.0001), Hispanics (−1.8%/year, P<0.0001), and other racial/ethnic groups (−1.2%/year, P=0.04) (Table 3).

Table 2:

Site-specific biliary tract cancer age-adjusted incidence trends by gender, United States, 1999–2013a,b,c

| Cancer Site | Male | Female | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eAPC | AAIR | P-value | eAPC | AAIR | P-value | |||

| 1999–2001 | 2011–2013 | 1999–2001 | 2011–2013 | |||||

| GBC | 0.1 | 11.2 | 11.5 | 0.66 | −0.5 | 20.0 | 18.5 | 0.01 |

| ICC | 2.6 | 14.2 | 18.2 | 0.0003 | 3.7 | 9.8 | 14.5 | <0.0001 |

| ECC | 1.7 | 11.9 | 15.4 | 0.003 | 1.9 | 7.8 | 10.2 | 0.002 |

| AVC | −0.2 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 0.48 | −0.2 | 6.2 | 6.1 | 0.44 |

Abbreviations: age-adjusted incidence rate (AAIR), ampulla of Vater cancer (AVC), estimated annual percent change (eAPC), extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ECC), gallbladder cancer (GBC), intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC).

Source: Thirty-eight National Program of Cancer Registries and Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registries that met data quality standards of the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR) for the period 1999–2013.

AAIRs are presented as per 1,000,000 person-years and age-adjusted with the 2000 U.S. population.

Tests for parallelism comparing trends among females with those for males had P<0.05 for ICC. All other tests for parallelism had P≥0.05.

Table 3:

Site-specific biliary tract cancer age-adjusted incidence trends by race/ethnicity, United States, 1999–2013a,b,c

| Cancer Site | Non-Hispanic White | Non-Hispanic Black | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic Other | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eAPC | AAIR | P-value | eAPC | AAIR | P-value | eAPC | AAIR | P-value | eAPC | AAIR | P-value | |||||

| 1999–2001 | 2011–2013 | 1999–2001 | 2011–2013 | 1999–2001 | 2011–2013 | 1999–2001 | 2011–2013 | |||||||||

| GBC | −0.9 | 14.3 | 12.6 | 0.0001 | 1.8 | 19.0 | 23.7 | <0.0001 | −1.8 | 33.9 | 26.3 | <0.0001 | −1.2 | 23.3 | 20.5 | 0.04 |

| ICC | 3.4 | 11.1 | 15.7 | <0.0001 | 2.6 | 11.1 | 14.4 | 0.001 | 2.0 | 16.2 | 19.6 | 0.002 | 1.4 | 19.6 | 21.4 | 0.04 |

| ECC | 1.7 | 9.1 | 11.8 | 0.003 | 3.1 | 8.1 | 12.2 | 0.0002 | 0.8 | 13.9 | 15.6 | 0.23 | 0.6 | 15.5 | 18.1 | 0.39 |

| AVC | −0.3 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 0.17 | −0.2 | 6.4 | 6.1 | 0.71 | 0 | 10.9 | 10.6 | 0.99 | 0.2 | 10.6 | 10.6 | 0.73 |

Abbreviations: age-adjusted incidence rate (AAIR), ampulla of Vater cancer (AVC), estimated annual percent change (eAPC), extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ECC), gallbladder cancer (GBC), intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC).

Source: Thirty-eight National Program of Cancer Registries and Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registries that met data quality standards of the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR) for the period 1999–2013.

AAIRs are presented as per 1,000,000 person-years and age-adjusted with the 2000 U.S. population.

Tests for parallelism comparing GBC trends for non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics with non-Hispanic whites had P<0.05. All other tests for parallelism had P≥0.05.

When temporal trends in site-specific incidence rates were analyzed by age group, trends in GBC and AVC rates differed between 18–44 and ≥45-year-olds (P for parallelism=0.04); whereas, ICC and ECC rates increased for both age groups (P for parallelism=0.90 for ICC and 0.34 for ECC) (Table 4 and Supplementary Table S2). Among 18–44-year-olds, GBC incidence rates rose by 1.8%/year (P=0.01), while they decreased slightly among people ≥45 years (eAPC=−0.4%/year; P=0.009; P-parallelism=0.04) (Table 4). Similarly, while AVC rates rose among 18 to 44-year-olds (eAPC=1.8%/year, P=0.03), trends remained flat among people ≥45 years (eAPC=−0.2%/year; P-parallelism=0.03) (Table 4).

Table 4:

Site-specific biliary tract cancer age-adjusted incidence rate trends by dichotomous age group (18 to 44 vs. ≥45), United States, 1999–2013a,b,c

| Cancer Site | 18 to 44 years-old | ≥45 years-old | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eAPC | AAIR | P-value | eAPC | AAIR | P-value | |||

| 1999–2001 | 2011–2013 | 1999–2001 | 2011–2013 | |||||

| GBC | 1.8 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.01 | −0.4 | 33.5 | 31.4 | 0.009 |

| ICC | 3.3 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 0.0001 | 3.2 | 23.7 | 32.5 | <0.0001 |

| ECC | 3.4 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.02 | 1.8 | 19.6 | 25.6 | 0.002 |

| AVC | 1.8 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.03 | −0.2 | 15.5 | 15.3 | 0.30 |

Abbreviations: age-adjusted incidence rate (AAIR), estimated annual percent change (eAPC).

Source: Thirty-eight National Program of Cancer Registries and Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registries that met data quality standards of the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR) for the period 1999–2013.

AAIRs are presented as per 1,000,000 person-years and age-adjusted with the 2000 U.S. population.

Tests for parallelism comparing trends for 18 to 44-year-olds with those for people ≥45 years had P<0.05 for GBC and AVC and P≥0.05 for ICC and ECC.

Comparison of Sex and Race/Ethnicity Incidence Rate Ratios by Age Group:

GBC and AVC were the two sites with different incidence trends by age group between 1999 and 2013. Comparisons of rate ratios by sex and race/ethnicity between 18–44 vs. ≥45-year-olds showed that sex and racial/ethnic difference in GBC incidence rates were significantly larger among 18–44-year-olds than ≥45-year-olds (Figure 2A). For AVC, rate ratios for sex and race/ethnicity did not differ by age group (Figure 2B).

Figure 2:

Abbreviations: AVC, ampulla of Vater cancer; CI, confidence interval; GBC, gallbladder cancer; IRR, incidence rate ratio; NHB, non-Hispanic black race/ethnicity; NHO, non-Hispanic other race/ethnicity; NHW, non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity.

Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and 95% CIs for female-to-male, black-to-white, Hispanic-to-white, and other-to-white comparisons of age-adjusted incidence rates stratified by age group (black solid boxes for 18 to 44-year-olds, and open boxes for ≥45-year-olds) by cancer site [2A-gallbadder cancer (GBC) and 2B-ampulla of Vater (AVC)] in the United States, 1999–2013, P-values correspond to the Wald test for the difference between incidence rate ratios for younger vs. older people. Source: Thirty-eight National Program of Cancer Registries and Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registries that met data quality standards of the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR) for the period 1999–2013.

DISCUSSION

Previous descriptive epidemiology studies on BTCs have either focused on a single BTC, such as GBC, or have analyzed BTCs collectively. Etiologic research on BTCs suggests that risk factors vary by anatomic site within the biliary tract, making examination of incidence rates and trends by demographic group and anatomic site particularly important. From 1999 to 2013, we observed incidence rates and trends in rates that varied by site within the biliary tract and by sex, race/ethnicity, and age. Divergent biliary tract cancer trends and incidence rate patterns among different demographic groups by anatomic site may be driven by different etiologies or variations in risk factor patterns between these groups. Knowing this information aids public health management, especially for groups at highest risk of developing a BTC or groups showing increasing trends in BTC incidence. Because of the rarity of BTCs, especially when examined by anatomic site, large meta-analyses and pooling projects provide a unique opportunity to gain insight into variation in risk associations by BTC site.

Consistent with prior studies, we found that GBC incidence rates were highest among women, Hispanics, and older age groups.1, 5, 6, 13–21 These differences between demographic groups in GBC incidence rates may be explained by variation in risk factor prevalence by sex and race/ethnicity. Gallstones and subsequent cholecystitis, which are the primary risk factors for GBC, are more common among women, Native Americans/Alaskan Natives, and Hispanics in the U.S.21 Approximately a third of gallbladder cancers have been estimated to be attributable to obesity,22 which differentially affects blacks and Hispanics in comparison with whites.23

Overall, GBC incidence rates declined,6, 20 but trends differed by demographics. While incidence declined among females,6, 13, 20 rates remained stable among males.6, 16, 20 Rates increased among blacks but decreased among all other racial/ethnic groups.6, 13, 15, 16, 20 We also confirmed reports of increasing rates in younger adults and decreasing rates among older adults.6, 17 Our analysis is unique in that we evaluated sex and racial/ethnic differences by age group. We found that differences in rates between men and women and between whites and blacks, Hispanics, and people of other racial/ethnic groups were significantly larger among 18–44 than ≥45-year-olds. Such widening gaps in GBC incidence rates by sex and race/ethnicity among younger adults suggest that there may be different etiologic factors or changing exposure to these factors among younger adults among whom rates are increasing.

These findings also raise the question whether these trends can be explained by changing prevalence in risk factors and cholecystectomy practices impacting some demographic groups more than others. Having had one’s gallbladder removed eliminates a person’s risk for developing GBC. For example, the decreasing GBC rates among females, but not males, may be due to increasing cholecystectomy rates among females.20 Gallstones and obesity are GBC risk factors with increasing prevalence among all children of all ages.24–27 In the U.S., Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks have the highest childhood obesity rates and increasing trends among preschool-aged children through adolescents.25, 26 Childhood obesity is also associated with increasing rates of hospitalization for symptomatic gallstones,27 with the largest increases in laparoscopic cholecystectomy occurring in obese 15–24-year-olds.28 The fact that GBC rates are increasing among younger adults despite increasing cholecystectomy practices indicates that the GBC rates might be even higher among younger demographic groups as they age if it were not for increasing rates of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Collectively, these findings suggest higher gallbladder disease burden among younger Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks, predisposing them to higher GBC risk than older age groups and/or other racial/ethnic groups.

As in previous studies,29–34 we found higher ICC incidence rates for males, Hispanics and other non-Hispanic racial/ethnic groups, and older ages. ICC risk factors include: chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis, biliary stones, infections (hepatitis B and C viruses, liver flukes), bile duct anomalies, some autoimmune diseases, obesity, diabetes, and smoking.35–39 While the prevalence of these risk factors differs by demographic group, the commonality is that they involve inflammatory processes. In recent years, the gap in rates between males and females has narrowed.32 Supporting this reduction in differences in rates by sex, ours and prior studies report steeper increases in rates for females than males33 and for whites than other racial/ethnic groups.36 It is unclear whether these trends and incidence patterns reflect increasing prevalence of medical conditions and behavioral risk factors among females and whites or increasing prevalence of novel risk factors specific to these demographic groups.38, 39

As previously shown,15, 18, 29, 31, 33 we saw differences in ECC incidence rates and trends by demographic group. ECC rates in the U.S. have been higher for males than females. Rates are also highest among people of non-Hispanic other race/ethnicity (e.g., American Indians/Alaskan Natives and Asian/Pacific Islanders) followed by Hispanics.1, 15, 18, 29, 33 While ECC shares many risk factors with ICC, having a history of a cholecystectomy increases a person’s risk of ECC, but not ICC.37 Despite increasing ECC incidence rates among women who more commonly have gallstones and a subsequent cholecystectomy,15 the female-to-male IRR has remained relatively stable from the 1990s to 2012.31 Our observation of increasing rates among blacks and whites, but not Hispanics or people of non-Hispanic other race/ethnicity, confirmed previous findings.15 Moreover, while ECC incidence rates increase with age,29, 33 and only approximately one-fifth of ECC cases were diagnosed under the age of 60,31 the fastest rising rates in our study were among 18–44-year-olds. These trends may be related to increasing rates of chronic liver diseases, including non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, diabetes, and hepatitis C viral infection in the U.S., especially among younger intravenous drug abusers.37, 40–42 Finally, the reclassification of Klatskin tumors as ECC does not account for increasing ECC incidence, suggesting a true increase in ECC incidence.33, 34

In our study and prior reports, AVC incidence rates were higher among males, people of other race/ethnicity (including Asian/Pacific Islanders and American Indians/Alaskan Natives), and Hispanics.1, 15, 43 Due to the rarity of AVC, few risk factors are known. Overall trends in AVC incidence rates remained flat.20, 43 Importantly, we observed increasing rates among 18 to 44-year-olds but flat or decreasing rates among people ≥45 years, again raising questions about why incidence rates are increasing among younger adults. However, no differences between the two age groups in female-to-male or race/ethnicity IRRs were found that could explain these divergent trends. One possibility is that having had a cholecystectomy increases AVC risk.4 Gallbladder removal can impact bile composition and flow, potentially damaging the downstream biliary tree and small intestine. Furthermore, these procedures are increasingly being performed on younger patients with the advent of laparoscopic cholecystectomy and the increasing prevalence of gallstones in younger patients.28, 44 Analysis of trends in the future will hopefully elucidate whether AVC incidence rates will increase as birth cohorts with increased exposure to gallstones and cholecystectomy get older.

Our findings of variation in BTC incidence rates and trends by anatomic site within the biliary tract support the need to assess BTCs by anatomic site. Moreover, cancer at different sites in the biliary tract are associated with different risk factors. Evaluation of rates and trends by demographic group may help identify groups at increased risk of cancer incidence, as our findings that the rate of GBC incidence is increasing among 18–44-year-olds demonstrates. To understand the underlying risk factors that drive these rates, future research using large pooling projects that combine data across multiple sources and populations is warranted. One such resource is the Biliary Tract Cancers Pooling Project (BiTCaPP) that includes data on over 2.8 million people and over four-thousand BTC cases.45

Our work has several important strengths. We examined data from 38 registries, representing approximately 85% of the US population. This extensive dataset provided sufficient numbers to study biliary tract cancers by anatomic site in a population where these cancers, especially AVC, are rare. Because of the large population studied, we could analyze and identify divergent trends by sex, race/ethnicity, and age group. The identification of differences in incidence rates among specific demographic groups for GBC provides insight into potential etiologic factors.

One major limitation of our analysis and of the reported literature on GBC rates is that population-level estimates are not adjusted for cholecystectomy rates. Not subtracting people who no longer have a gallbladder from the denominator of the population being studied underestimates actual GBC rates. Subsequently, it would be useful to have nationally representative cholecystectomy rates to be able to correct the population denominator. Changes in cholecystectomy practices over time, e.g., due to the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, could distort any trend estimates. Furthermore, any disparities in cholecystectomy practices by demographic group may potentially impact future trends in GBC mortality rates, as has been observed for other cancer sites.46 Another limitation is that we did not have the data to analyze Native Americans and Asians/Pacific Islanders, who traditionally demonstrate higher rates of some biliary tract cancers like GBC, as distinct racial/ethnic groups. Also, as our analysis does not include the 2014 and 2015 data, any changes that occurred in more recent years would not be reflected in our results. On graphical assessment, our assumption of a linear model by specifying zero joinpoints when assessing trends appeared to be violated for ICC and ECC where there were shifts in APCs. These shifts were likely driven by coding changes. Finally, as our analyses are restricted to incidence rates and trends and do not investigate mortality rates and trends by BTC site and demographic group, future research is needed to evaluate these outcome patterns.

In conclusion, the different patterns of rates by anatomic site and demographic groups suggest that variation in prevalence of risk factors may underlie our observations. The temporal trends by sex, race/ethnicity, age, and anatomic site indicate that the changes in prevalence of risk factors over time may vary by demographic group. They also may reflect changing the mix of risk factors over time that potentially influence differential fluctuations in rates over time by demographic group. These findings may provide important public health guidance for demographic groups with higher or increasing rates for potential intervention strategies of modifiable risk factors. They also highlight that large pooling projects are needed to investigate etiologic heterogeneity of these rare biliary tract cancers by anatomic site.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors acknowledge David Check with the Biostatistics Branch in the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics at the National Cancer Institute for assistance with the figures and the state and regional cancer registries affiliated with NAACCR for collecting data used in this study.

Funding Sources: This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program in the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics at the National Cancer Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure Statement: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Goodman MT, Yamamoto J. Descriptive study of gallbladder, extrahepatic bile duct, and ampullary cancers in the United States, 1997–2002. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18: 415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67: 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Factsand Figures, 2016–2017. Atlanta, Georgia: American Cancer Society, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nogueira L, Freedman ND, Engels EA, Warren JL, Castro F, Koshiol J. Gallstones, cholecystectomy, and risk of digestive system cancers. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179: 731–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Randi G, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Gallbladder cancer worldwide: geographical distribution and risk factors. Int J Cancer. 2006;118: 1591–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henley SJ, Weir HK, Jim MA, Watson M, Richardson LC. Gallbladder Cancer Incidence and Mortality, United States 1999–2011. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24: 1319–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NAACCR Incidence Data - CiNA Analytic File, 1995–2013, for Expanded Races, Standard File, Van Dyke - Trends in Biliary Tract Cancer (Single Age) (which includes data from CDC’s National Program of Cancer Registries (NCPR), CCCR’s Provinical and Territorial Registries, and the NCI’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Registries). In: Registries NAAoCC e, editor.

- 8.International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. third ed. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altekruse SF, Devesa SS, Dickie LA, McGlynn KA, Kleiner DE. Histological classification of liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancers in SEER registries. J Registry Manag. 2011;38: 201–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.SSER*Stat software. In: NCI TSRPotDoCCaPS, editor. Calverton, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joinpoint Regression Program: Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19: 335–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alberts SR, Kelly JJ, Ashokkumar R, Lanier AP. Occurrence of pancreatic, biliary tract, and gallbladder cancers in Alaska Native people, 1973–2007. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2012;71: 17521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barakat J, Dunkelberg JC, Ma TY. Changing patterns of gallbladder carcinoma in New Mexico. Cancer. 2006;106: 434–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castro FA, Koshiol J, Hsing AW, Devesa SS. Biliary tract cancer incidence in the United States-Demographic and temporal variations by anatomic site. Int J Cancer. 2013;133: 1664–1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaruvongvanich V, Yang JD, Peeraphatdit T, Roberts LR. The incidence rates and survival of gallbladder cancer in the USA. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiran RP, Pokala N, Dudrick SJ. Incidence pattern and survival for gallbladder cancer over three decades--an analysis of 10301 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14: 827–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nir I, Wiggins CL, Morris K, Rajput A. Diversification and trends in biliary tree cancer among the three major ethnic groups in the state of New Mexico. Am J Surg. 2012;203: 361–365; discussion 365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahman R, Simoes EJ, Schmaltz C, Jackson CS, Ibdah JA. Trend analysis and survival of primary gallbladder cancer in the United States: a 1973–2009 population-based study. Cancer Med. 2017;6: 874–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang JD, Kim B, Sanderson SO, et al. Biliary tract cancers in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976–2008. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107: 1256–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hundal R, Shaffer EA. Gallbladder cancer: epidemiology and outcome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6: 99–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnold M, Pandeya N, Byrnes G, et al. Global burden of cancer attributable to high body-mass index in 2012: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16: 36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Trends in Obesity Among Adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315: 2284–2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016 In: Statistics NCfH, editor. NCHS data brief; Hyattsville, MD, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson SE, Whitaker RC. Prevalence of obesity among US preschool children in different racial and ethnic groups. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163: 344–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Claire Wang Y, Gortmaker SL, Taveras EM. Trends and racial/ethnic disparities in severe obesity among US children and adolescents, 1976–2006. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6: 12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fradin K, Racine AD, Belamarich PF. Obesity and symptomatic cholelithiasis in childhood: epidemiologic and case-control evidence for a strong relation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58: 102–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tucker JJ, Grim R, Bell T, Martin J, Ahuja V. Changing demographics in laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed in the United States: hospitalizations from 1998 to 2010. Am Surg. 2014;80: 652–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altekruse SF, Petrick JL, Rolin AI, et al. Geographic variation of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. PLoS One. 2015;10: e0120574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan SA, Emadossadaty S, Ladep NG, et al. Rising trends in cholangiocarcinoma: is the ICD classification system misleading us? J Hepatol. 2012;56: 848–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saha SK, Zhu AX, Fuchs CS, Brooks GA. Forty-Year Trends in Cholangiocarcinoma Incidence in the U.S.: Intrahepatic Disease on the Rise. Oncologist. 2016;21: 594–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaib Y, El-Serag HB. The epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24: 115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tyson GL, Ilyas JA, Duan Z, et al. Secular trends in the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma in the USA and the impact of misclassification. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59: 3103–3110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Welzel TM, McGlynn KA, Hsing AW, O’Brien TR, Pfeiffer RM. Impact of classification of hilar cholangiocarcinomas (Klatskin tumors) on the incidence of intra- and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98: 873–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ben-Menachem T Risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19: 615–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel T Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2001;33: 1353–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petrick JL, Yang B, Altekruse SF, et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: A population-based study in SEER-Medicare. PLoS One. 2017;12: e0186643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Welzel TM, Graubard BI, El-Serag HB, et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a population-based case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5: 1221–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Welzel TM, Mellemkjaer L, Gloria G, et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in a low-risk population: a nationwide case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2007;120: 638–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grant WC, Jhaveri RR, McHutchison JG, Schulman KA, Kauf TL. Trends in health care resource use for hepatitis C virus infection in the United States. Hepatology. 2005;42: 1406–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Duan Z, Yu X, White D, El-Serag HB. Trends in the Burden of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in a United States Cohort of Veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14: 301–308 e301–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim Y, Ejaz A, Tayal A, et al. Temporal trends in population-based death rates associated with chronic liver disease and liver cancer in the United States over the last 30 years. Cancer. 2014;120: 3058–3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Albores-Saavedra J, Schwartz AM, Batich K, Henson DE. Cancers of the ampulla of vater: demographics, morphology, and survival based on 5,625 cases from the SEER program. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100: 598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dua A, Aziz A, Desai SS, McMaster J, Kuy S. National Trends in the Adoption of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy over 7 Years in the United States and Impact of Laparoscopic Approaches Stratified by Age. Minim Invasive Surg. 2014;2014: 635461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Dyke AL, Langhamer MS, Zhu B, et al. Family History of Cancer and Risk of Biliary Tract Cancers: Results from the Biliary Tract Cancers Pooling Project. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27: 348–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beavis AL, Gravitt PE, Rositch AF. Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates reveal a larger racial disparity in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123: 1044–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.