Abstract

The role of transcriptional regulator ten-eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenease 1 (TET1) has not been well characterized in lung cancer. Here we show that TET1 is overexpressed in adeno- and squamous cell carcinomas. TET1 knockdown reduced cell growth in vitro and in vivo and induced transcriptome reprogramming independent of its demethylating activity to affect key cancer signaling pathways. Wild type p53 bound the TET1 promoter to suppress transcription, while p53 transversion mutations were most strongly associated with high TET1 expression. Knockdown of TET1 in p53 mutant cell lines induced senescence through a program involving generalized genomic instability manifested by DNA single- and double-strand breaks and induction of p21 that was synergistic with cisplatin and doxorubicin. These data identify TET1 as an oncogene in lung cancer whose gain of function via loss of p53 may be exploited through targeted therapy-induced senescence.

Keywords: TET1, p53, genomic instability, senescence

Introduction

Lung cancer, with 220,000 diagnosed cases and 160,000 deaths reported annually in United States, remains the leading cause of all cancer related mortalities (1). Transcriptional reprogramming of normal lung epithelium caused by a multitude of epigenetic changes has been defined as one of the main factors responsible for lung cancer development and progression (2). Extensive studies performed in the last two decades demonstrated that two major classes of epigenetic modifiers frequently overexpressed in lung cancer drive this process. First, enzymes classified as “writers” that include histone acetyltransferases (BMI1 within the Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 [PRC1]), histone methyltransferases (EZH2 and G9a within the PRC2 and EHMT-1/-2 complexes, respectively) and cytosine DNA methyltransferases (DNMT1, DNMT3a and DNMT3b) drive de novo synthesis and maintenance of transcription modulating marks within gene promoters (2, 3). Second, epigenetic “readers” that include methyl-CpG-binding (MBD) proteins (MECP2, MBD1-6, SET1-2, ZBTB4 and others) recognize and bind to histones and DNA sequences modified by “writers” to change the expression profile of target genes (2, 4). Specifically in the case of modifications of CpG islands present in gene promoters, their hypermethylation followed by MBD protein binding disrupts RNA polymerase and enhancer complexes resulting in transcriptional silencing of numerous oncosuppressors (e.g. p16, GATA5) leading to transformation and development of a malignant phenotype (5, 6).

While the role of “writers” and “readers” in lung carcinogenesis has been well established, a new component of epigenetic reprograming has emerged with the discovery of a novel class of enzymes represented by the ten-eleven translocation (TET) gene family. Classified initially as “erasers”, these three homologous enzymes (TET1, TET2 and TET3) can demethylate CpG islands within the genome (7, 8). Chemical characterization showed that TET1 is an Fe(II)- and α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase that can convert 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) iteratively to 5-hydroxylmethylcytosine (5-hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5-fC), and 5-carboxylcytosine (5-caC) (9). Ultimately, the chemical modifications initiated by TET1 may lead to replacement of 5-mC with non-methylated cytosine and potential subsequent activation of gene transcription (8, 9). Apart from this canonical mechanism that is most commonly found in embryonic and pluripotent stem cells, several alternative modes of TET1-dependent gene regulation have been identified. TET1-induced enrichment of 5-hmC within gene bodies and regulatory regions that is not followed by its further oxidation can lead to increased or decreased transcription in a tissue- and gene-specific manner (10, 11). Through a second mechanism independent of its oxygenase activity, TET1 can modulate gene expression by forming protein-to-protein complexes with transcription regulators like HIF-1α that target them to binding 5-mC genomic loci (12). Finally, TET1 can modulate gene expression through binding to and around the transcription start site of genes with a preference for polycomb group genes (13–15). Together, these studies demonstrate that TET1 can regulate expression of its target genes in a loci- and cell-specific manner via distinct mechanisms, either as an epigenetic or genetic factor.

A tissue-dependent function of TET1 has also been recognized in regards to its role in tumor biology (16). Its functional relevance to carcinogenesis was first discovered in MLL-rearranged leukemia where TET1 was overexpressed and conferred oncogenic properties by protecting cells from apoptosis (17, 18). However, in contrast to hematopoietic malignancies, the majority of reports suggest that TET1 may function as a tumor suppressor in solid tumors. Reduction of its expression and enzymatic activity has been found in breast, gastric, colorectal and liver cancers, and was associated with a more aggressive phenotype of cancer cells as manifested by higher transformation rate, increased proliferation, colony formation, and migratory and metastatic potential (19–22). With respect to lung cancer, a comprehensive investigation regarding TET1 expression and function in the major histological subtypes has not been conducted.

Considering the epigenetically driven characteristics of lung cancer and the importance of TET1 demonstrated in other solid tumors, we hypothesized that TET1 levels may be altered in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tumors and impact the cancer cell phenotype. This hypothesis was evaluated by first determining TET1 expression levels across NSCLC tumors and derived cell lines. In addition, the effect of modulating TET1 expression on cell phenotype in vitro and in vivo was characterized. Finally, factors regulating TET1 transcription, the mechanism underlying its effects on cancer cell phenotype, and its impact as a therapeutic target were elucidated.

Materials and Methods

The Institutes’ Ethical Committees approved these studies which were conducted in accordance with US Common Rule guidelines. All human samples were obtained with written informed consent from participating patients. Lung tumor–normal pairs from 50 NSCLC patients were obtained from frozen tumor banks at The University of New Mexico (UNM, Albuquerque, NM) and the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN). NSCLC cell lines (n = 21) were obtained from ATCC. H1299 cell line with temperature-regulated p53 expression was obtained from Dr. Yohannes Tesfaigzi, LRRI (Albuquerque, NM). Four immortalized HBEC lines (HBEC2, HBEC3, HBEC4 and HBEC14) were obtained from Drs. Shay and Minna, Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, TX). Cell line authentication was performed using FTA Sample Collection Kit for Human Cell Authentication (ATCC). Cells were tested negative for mycoplasma using MycoProbe Detection Kit (R&D Systems). NSCLC cells were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine and 1% pen/strep (Life Technologies), and HBEC cells were cultured in complete KSFM medium (Life Technologies) at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere and subcultured for up to 20 passages. Datasets for gene expression (Illumina HiSeq RNA sequencing Version 2 [RNAseq]) and somatic mutations (Illumina_Genome_Analyzer_ DNA_Sequencing_level2 [DNAseq]) were collected from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, phs000178.v9.p8). TET1 expression was extracted from TCGA RNA-seq data for 464 adenocarcinomas, 419 squamous cell carcinomas, and 109 normal lungs. TET1 expression was defined as elevated if the reads were above the 95 percentile of TET1 expression detected in normal lungs. A total of 437 AdCs and 178 SCCs had data for gene expression and somatic mutations in tumors and were used for assessing the prevalence of TP53 mutations and their association with TET1 expression. The top quartile + lowest quartile were used to define TET1high and TET1low expressing tumors, respectively in the RNA-seq TCGA dataset. Cells were transfected with siRNA using Lipofectamine 3000 (Life Technologies) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Two different control siRNAs (Silencer Select Negative Control #1 and #5, Life Technologies) and TET1 siRNAs (Silencer Select ID #37193 and #37194, Life Technologies) were used and gave identical results. To develop xenograft tumors, cells were inoculated bilaterally into the posterior flanks of 7-week old athymic nude mice and monitored for tumor size for 21 days. mRNA levels were analyzed using real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) and Illumina Whole-genome HumanHT12v4 expression BeadChip, and protein levels were analyzed using Western blot. CpG methylation was analyzed using Illumina Human 450K methylation array (HM450K), and 5-hmC was measured using Dot blot. Genome wide datasets were deposited (GEO 121649). The total number of cells was assessed using crystal violet assay. Cell mortality was analyzed using propidium iodide exclusion test. Potential to form colonies was measured using soft agar assay. Senescent cells were detected using β-galactosidase activity assay. Transcriptional activity of TET1 promoter was analyzed using luciferase reporter vectors. Binding of p53 protein to TET1 promoter was assessed using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). DNA damage was assessed using micoronuclei assay assessment, comet assay and histone γH2AX staining. Comparisons of results between and among groups were performed using Student’s t-test and one-way ANOVA test followed by Dunnett’s post-test, respectively (GraphPad Prism 5.04). Statistical significance was defined as a p value < 0.05 (*), < 0.01 (**) or <0.001 (***). For TCGA data analysis, logistic regression was used to calculate the odds ratio and 95% confidence interval with elevated TET1 expression as the outcome and TP53 mutation as the independent variable with and without adjustment for age, sex, smoking history, stage, and histology. For details of experimental procedures see Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Results

TET1 gene expression is elevated in human lung tumor samples and NSCLC derived cell lines, and contributes to cell growth.

RT-qPCR was used to quantitate TET1 transcript levels in 25 squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and 25 adenocarcinoma (AdC) tumor-normal pairs. Independent analysis was performed using two different pairs of primers and two different RT-qPCR techniques (TaqMan and SYBR Green) with normalization to β-actin. TET1 was overexpressed 2- to 20-fold in 13 (52%) and 10 (40%) SCC and AdC tumors, respectively, when compared to paired normal lung tissue (Fig. 1A). Even more profound TET1 overexpression was found in a panel of NSCLC cell lines (n = 21) compared with 4 human bronchial epithelial cells (HBEC) lines: 6 NSCLC cell lines demonstrated over 2-fold increase in TET1 expression in comparison with HBECs, while in 9 cell lines TET1 overexpression exceeded 10-fold, and in 4 lines exceeded 25-fold (Fig. 1B). Of note, no significant differences in TET1 expression were detected among the 4 analyzed HBEC cell lines. Western blot assessed the relationship between TET1 mRNA and protein levels. Seven of 12 analyzed NSCLC cell lines showed over 10-fold increase of TET1 protein compared to HBECs, and 5 cell lines exceeded 50-fold overexpression (Fig. 1C). Finally, elevated expression of the TET1 gene was validated using RNA-seq data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database, showing that TET1 was overexpressed ≥2 fold in 72.8% of SCCs (n = 419) and 52.2% of AdCs (n = 464) relative to normal lung tissue (Fig. 1D). In addition to tumor histology, advanced stage (p = 0.021) and current smoking status (p = 0.0041) were also significantly associated with higher levels of TET1 expression in lung tumor tissues.

Fig. 1. TET1 gene expression is elevated in human lung tumor samples and NSCLC derived cell lines and contributes to cell growth.

TET1 mRNA levels were assessed in AdC and SCC tumor samples (n = 25 each) compared to paired normal lung tissue (A). TET1 mRNA levels in thirteen AdC-, two large cell- (LC) and six SCC-derived cell lines were compared to mean value for HBEC cell lines (B). Horizontal line indicates 2-fold increase in TET1 levels. TET1 protein levels in NSCLC cell lines and quantification (C). Expression of TET1 in lung cancer tumors in TCGA from AdC and SCC tumors compared to normal lung tissues, (p < 0.0001, D). H1299, H1975, H226, H441, A549 and Calu6 cells were transfected with control vs. TET1 siRNA and analyzed for proliferation (E) and colony formation (F) 120 h after transfection. H1299 and H226 cells transfected with control vs. TET1 siRNA were used for xenograft tumor formation in nude mice with assessment of tumor volume (G) and mass (H). Results are presented as an average of three (in vitro) or two (in vivo) experiments ±SEM, p *<0.05, **<0.01, or ***<0.001.

The elevated expression of TET1 found in malignant lung cancer cells could impact cell phenotype. Functional experiments performed on NSCLC cell lines of 3 different histologies (AdC, n = 5; SCC, n = 2; large cell (LC), n = 1) tested this hypothesis. Transient transfection with two unique TET1 targeting siRNAs caused 70% to 90% reduction of TET1 mRNA levels in cell lines quantified 48 hours after transfection (Fig. S1). TET1 knockdown significantly reduced proliferation of H1299, H1975, H226 and H441 cells at 120 h post-transfection by 63%, 40%, 24% and 21%, respectively, as determined using crystal violet assay (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, TET1 knockdown reduced anchorage independent growth of H1299, H226, and Calu6 lines as evident by 64%, 62% and 61% reduction in colony formation in soft agar, respectively (Fig. 1F). H441 and H1975 cells do not form colonies, and thus were not tested in this assay. No effect of TET1 knock down on cell growth was found in A549, H2023 and H2228 cell lines (Fig. 1E & F; Fig. S2). Finally, H1299 and H226 cells, in which inhibition of colony formation in vitro caused by TET1 knockdown was most profound, were assessed for effect on growth in vivo using an immunocompromised nude mouse xenograft model. Single transfection with TET1 siRNA 48h prior to subcutaneous inoculation inhibited tumor growth as shown by a reduction of tumor volume (61% and 45% reduction for H1299 and H226, respectively, Fig. 1G) and tumor mass (57% and 59% reduction for H1299 and H226, respectively, Fig. 1H).

TET1 expression in NSCLC cell lines is regulated by p53 binding in its proximal promoter region.

Experiments described above support a functional role for elevated TET1 levels in affecting the phenotype of NSCLC cells. Therefore, the mechanism responsible for overexpression was investigated by generating variants of the TET1 promoter region cloned into the reporter vector carrying a TSS and ORF for luciferase to characterize its transcriptional activity in NSCLC and HBEC cell lines (Fig. 2A). The full length TET1 promoter was previously shown to comprise approximately 1500 bp 5’ of the transcription start site (23). Seven deletion constructs were generated to determine the minimal region for promoter activity. Transfection of constructed vectors into the cells showed that activity of a DNA sequence comprising the full TET1 promoter (−1541 bp to +29 bp) was 10 to 70 fold higher in lung cancer cell lines (n = 3) compared with non-transformed lung epithelial cells (n = 2) and correlated with mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 2B). Over 95% of variation observed in gene expression levels across the 5 cell lines was explained by transcriptional activity. Further analysis of deletion variants identified a minimal fragment of the TET1 promoter of −192 bp downstream from the transcription start site as critical for its elevated transcription in NSCLC cell lines. The lack of this promotor fragment resulted in >98% reduction of reporter activity in NSCLC cell lines (Fig. 2C). In silico analysis of the −192bp/+29bp promoter fragment identified 20 predicted transcription binding sites within its sequence. Several of these factors that include p53, AP-2, STAT4, FOXP3 and c-Jun play important roles in lung carcinogenesis (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2. TET1 expression in NSCLC cell lines is regulated by p53 binding in its proximal promoter region.

Seven deletion variants of TET1 promoter ranging from −1541bp to +29bp from transcription start site were cloned (A). Transcriptional activity of the construct carrying full TET1 promoter (−1541bp to +29bp) was analyzed in NSCLCs and HBECs with various TET1 mRNA levels (B). Deletion variants were tested in three NSCLCs lines to identify minimal active region of TET1 promoter (C). Predicted transcription factor (TF) binding sites located in −192bp/+29bp TET1 promoter fragment were identified in silico using PROMO software (D). Cells characterized by p53-null (H1299), p53-mut (H1975, Calu6, H1993 and SW900) and WT p53 (A549 and H2228) status were evaluated using ChIP for p53 enrichment on the TET1 endogenous promoter (E). H1299 cells with temperature induced WT p53 expression (cultured at 32°C) were analyzed for −192bp/+29bp TET1 promoter activity (F) and endogenous TET1 mRNA levels (G) and normalized to WT p53-negative control (cultured at 37°C). Cells lines characterized by p53-null (H1299) or p53-mut (Calu6, H1975 and SW900) status were transfected with WT p53-coding vs. GFP-coding adenoviral vectors and were analyzed for TET1 mRNA levels 48 h later with normalization to PCNA (H). Cells characterized by WT p53 status (A549, H2228 and H2023) were transfected with p53-targeting vs. control siRNA and analyzed 48 h later for TET1 mRNA (I). Experiments were performed in triplicate and presented as mean ±SEM, p *<0.05, **<0.01, or ***<0.001.

Given the important transcriptional regulatory role of the p53 protein and its common loss of function in lung cancer, we evaluated the relationship between p53 mutation or deletion and TET1 expression. Cell lines characterized by loss of expression or mutation of p53 show higher average TET1 mRNA levels (27.0 fold normalized to HBECs, n = 11) compared to cell lines expressing wild type (WT) p53 (5.5 fold normalized to HBECs, n = 5) (Tables S1, S2 & S3). Moreover, TET1 knockdown affected growth of cells with p53 mutation (H1299, H1975, H226, Calu6 and H441), but not cells with wild type p53 (A549, H2023 and H2228), suggesting a functional link between p53 status, TET1 expression, and its impact on cell phenotype (Fig. 1 and Fig. S2). Thus, the hypothesis that wild type p53 negatively regulates TET1 transcription via direct binding to its promoter was tested with ChIP using a p53-specific antibody. As expected, no enrichment of p53 at its predicted binding site within the TET1 promoter region was detected in H1299 cells characterized by a p53-null mutation. Conversely, 23,800- and 13,500-fold enrichments of p53 at the TET1 promoter were found in the WT p53 cell lines A549 and H2228, respectively (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, p53 binding to the TET1 promoter was reduced ≥90% in p53-mutated cell lines (enrichment of 1,600-, 1,200-, 223- and 16-fold in H1975, Calu6, H1993 and SW900, respectively) and negatively correlated with overall TET1 expression (Fig. 2E). The functional relationship between p53 and TET1 expression was tested using H1299 cells with a temperature regulated WT p53 open reading frame (cells express WT p53 when cultured at 32°C while no WT 53 is expressed when cells are cultured at 37°C). Induction of WT p53 protein caused a 20% and 65% reduction of −192bp/+29bp TET1 promoter activity and a 62% and 85% decrease in transcript levels after 48h and 96h, respectively (Fig. 2F & G; Fig. S3). The transduction of four cell lines (H1299, Calu6, H1975 and SW900) characterized by endogenous p53 mutation or deletion with WT p53-coding adenoviral vector reduced TET1 mRNA levels 95%, 67%, 62% and 61%, respectively, compared to GFP-coding vector transduced controls (Fig. 2H). Conversely, knockdown of endogenous WT p53 using siRNA increased TET1 mRNA levels by 2.4-, 1.8- and 1.5-fold in A549, H2228 and H2023 cell lines, respectively (Fig. 2I). Finally, the correlation between elevated TET1 levels and p53 mutation was tested in tumor samples using TCGA data. Among 615 cancer patients with data for TET1 expression and somatic mutation in tumors, the prevalence rate of p53 mutation was 53% in AdC (n = 437) and 82% in SCC (n = 178). Logistic regression showed that p53 mutations were significantly associated with elevated TET1 expression (OR = 2.0, 95%CI = 1.4 – 2.9, p < 0.0001). Inclusion of age, sex, smoking history, stage, and histology in the model for covariate adjustment did not change the observed association (Table S4). Among 380 NSCLCs with p53 mutation, the prevalence of transition, transversion, and frameshift mutations were 31.6%, 56.6%, and 10.3%, respectively. Moreover, when including all three p53 mutation subtypes in the logistic regression model, p53 transversion mutations, that were all localized to the p53 DNA binding domain, was the only mutation associated with elevated TET1 expression (OR=2.6, 95% CI=1.7–3.8, p < 0.001) compared to lung cancers with wild type p53 (Table S4).

TET1 knockdown in NSCLC cells induces cellular senescence and genomic instability.

Subsequent studies addressed the mechanism responsible for growth inhibition caused by TET1 knock down. H1299, H1975 and H226 cell lines, whose growth was most profoundly affected by TET1 depletion, were analyzed (Fig. 1). While the number of dead cells did not increase, dramatic changes in cell morphology appeared on day 3 after transfection with the TET1 siRNA, and were most profound 2 days later (representative images for H1299 shown in Fig. 3A). Cell morphology (enlarged size and flattened shape) suggested that these cells were undergoing cellular senescence and this was confirmed by analyzing the cells for β-galactosidase activity, a metabolic marker of senescence. Less than 1% of control cells showed detectable activity of this enzyme, while in the TET1 knockdown population, approximately 40% (H1299), 18% (H1975) and 6% (H226) of cells were β-galactosidase positive (Fig. 3B & C). RT-qPCR expression analysis of major senescence effector and marker genes showed that while no changes in p14 or p16 were found, 3.3- and 1.8-fold increase in p21 mRNA levels were detected in H1299 and H1975 cells, respectively, 96 h after transfection along with increased protein levels confirming cell cycle-dependent and senescence-related inhibition of their proliferation (Fig. 3D & E).

Fig. 3. TET1 overexpression prevents NSCLC cells from cellular senescence and genomic instability.

H1299, H1975 and H226 cells were transfected with control vs. TET1 siRNA and assessed for morphology (A) and activity of β-galactosidase (B) using microscopy and β-galactosidase activity assay (scale bar = 100μm, representative images for H1299 shown). Percentage of cells positive for β-galactosidase was calculated (C). Levels of p21 mRNA were quantified 72 h and 96 h after transfection of H1299 and H1975 cells with control vs. TET1 siRNA (D), and TET1 and p21 protein was detected 96 h after transfection (E). The level of DNA double-strand breaks was assessed in H1299 and H1975 cell lines 72 h after transfection with control vs. TET1 siRNA using the micronuclei assay (F), H1299 cells were also analyzed for DNA strand breaks using the comet assay (G), and for DNA damage response activation associated with γH2AX translocation using immunofluorescence (H). The percentage of cells positive for γH2AX foci was calculated (I). Ingenuity Pathway Analysis was used to identify pathways differentially expressed in AdC and SCC tumors from TCGA characterized by TET1high vs. TET1low gene expression (J, K). Results are presented as an average of three experiments ±SEM, p *<0.05, **<0.01, or ***<0.001.

Induction of senescence in replication-unlimited cancer cells is often caused by accumulation of DNA damage. Thus, cells with TET1 knockdown were analyzed for the level of double- and single-strand DNA breaks using micronuclei and comet assays, respectively. Seventy-two hours after transfection with TET1 targeting siRNA when cells acquired a senescent phenotype defined by changed morphology and p21/β-galactosidase upregulation, the percentage of micronucleated cells increased from less than 1% to 11% and 4% in H1299 and H1975, respectively (Fig. 3F). In H1299, DNA damage assessed by the comet assay increased from 2% to 15% of total DNA content (Fig. 3G). The magnitude of DNA damage at this time point after transfection was further analyzed by immunostaining for γH2AX protein that translocates to DNA break loci (Fig. 3H). The percentage of H1299 cells with γH2AX accumulation increased from less than 1% in controls up to 11% in TET1 knockdown cells, confirming the high level of genomic aberrations induced by TET1 depletion (Fig. 3H & I). Finally, pathway analysis based on RNA-seq data from TCGA lung tumors characterized by TET1high vs. TET1low levels demonstrated that cellular processes most affected by different TET1 expression levels in AdC and SCC tumors included DNA damage response, cell cycle checkpoint control, chromosomal replication and DNA double-stand break repair (Fig. 3J & K). The genes altered within these pathways are listed in Tables S5 and S6.

Depletion of WT p53 expression or function sensitizes cells to TET1 knockdown induced cellular senescence.

Results described above demonstrate that TET1 depletion induces excessive genomic instability that is followed by senescence-associated terminal growth inhibition. Interestingly, that effect was found exclusively in cells characterized by p53 mutation (H1299, H1975 and H226) with cells harboring WT p53 being unaffected (A549, H2023 and H2228). Thus, we hypothesized that elevated TET1 expression prevents lung cancer cells from cellular senescence when p53 function is affected. To test this hypothesis, double knockdown of p53 and TET1 was performed in A549 cells using corresponding siRNAs. Microscopic observation performed 120 h after transfection demonstrated that while depletion of neither TET1 nor p53 altered cell morphology, simultaneous knockdown of these genes confers a flattened and enlarged shape characteristic of an aged phenotype (Fig. 4A). The micronuclei assay demonstrated that while single depletion of TET1 or p53 genes caused minor increases in DNA double-strand break levels (1% and 1.5% increase, respectively), simultaneous knockdown of those genes was additive for micronuclei induction (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, while no significant changes were found in TET1 knockdown or p53 knockdown cells with regard to β-galactosidase activity, a synergistic increase was seen for this senescence marker (increasing from 1.4% in control cells to 14.4% in TET1+p53 depleted cells using either TET1 siRNA [Fig. 4C, Fig. S4]). Expression analysis and the crystal violet assay further demonstrated that the acquired senescent phenotype was accompanied by a 1.8-fold increase in p21 levels 96 h after transfection and affected cell proliferation as demonstrated by a 47% reduction of cell number 120 h after transfection (Fig. 4D & E). These experiments were validated using a chemical inhibitor, pifithrin-α, that blocks the p53-dependent transactivation of p53-regulated genes. Similar to p53 knockdown with siRNA, treatment of A549 cells with pifithrin-α for 48 h increased TET1 mRNA levels 1.7-fold compared to vehicle control (Fig. 4F). Moreover, siRNA-induced knockdown of TET1 expression in A549 cells cultured with pifithrin-α induced senescence in 11% of cells (Fig. 4G, Fig. S4) and inhibited cell proliferation by 34% (Fig. 4G & H).

Fig. 4. Depletion of WT p53 expression or function sensitizes cells to TET1 knock down-induced cellular senescence.

A549 cells were transfected with control, TET1, p53 or TET1+p53 siRNAs. Analysis of cell morphology using microscopy was performed 120 h after transfection (A). Assessment of DNA double-strand breaks was performed using micronuclei assay 72h after transfection (B). Detection of β-galactosidase activity (C) and analysis of p21 mRNA levels (D) were performed 120 h and 96 h after transfection, respectively. Number of cells was assessed 120 h after transfection (E). In chemical p53 inhibition experiments, A549 cells were incubated with 30 μM of pifithrine-α (PTF-α) for 48 h and analyzed for TET1 mRNA (F). Cells cultured with PTF-α and transfected with control vs. TET1 siRNAs were analyzed for β-galactosidase activity (G) and for cell number (H) 120 h after transfection. Experiments were performed in triplicate and presented as mean ±SEM, p *<0.05.

TET1 reprograms the lung cancer cell transcriptome via CpG oxidation-independent mechanisms.

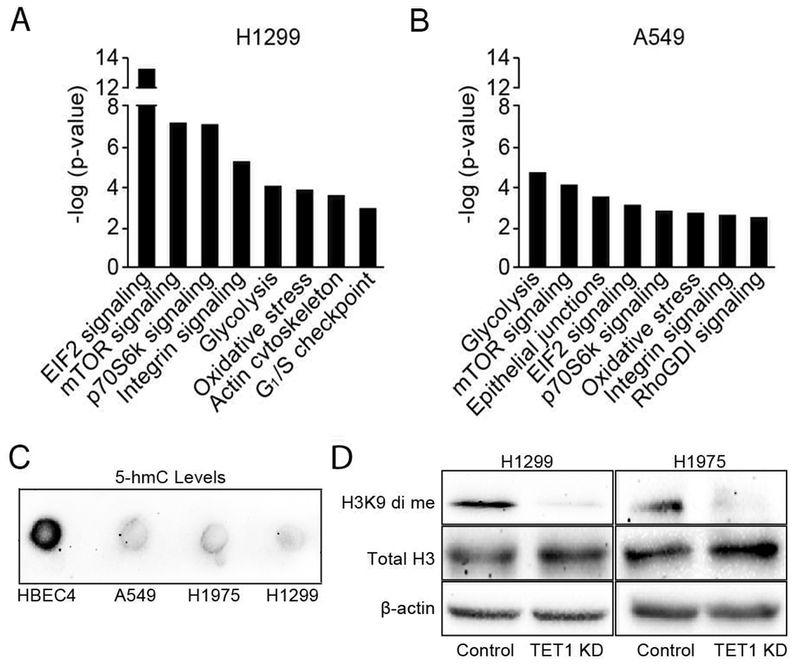

The magnitude of genomic abnormalities resulting in cell fate reprogramming induced by TET1 knockdown suggested that expression of genes and pathways important for cell phenotype may be affected. Expression array analysis identified 2690 and 1457 genes in which expression was changed by TET1 knockdown in H1299 and A549, respectively (Table S7). Ingenuity pathway analysis showed that the majority of affected genes were involved in pathways important for cell growth, metabolism, and cell cycle regulation (Fig. 5A & B). Illumina HM450K bead chip analysis of the methylome showed that for the 85,000 CpG probes residing in the promoter region (−200 -exon 1) only 8 and 4 in A549 and H1299 showed ≥25% change in methylation indicating that the canonical mechanism of TET1-dependent regulation involving oxidation and replacement of 5-mC to unmodified cytosine does not contribute to alterations of gene expression (Table S8). TET1 gene targets may also be regulated by accumulation of 5-hmC within their sequence; however, previously reported decreases in 5-hmC levels in cancer vs. normal lung tissue suggested that this mechanism is not relevant in lung cancer (24). Dot blot analysis confirmed that conclusion by demonstrating a lack of correlation between TET1 and 5-hmC levels in lung cell lines with TET1low HBEC4 cells having considerably higher total 5-hmC levels compared to TET1high A549, H1975 and H1299 cells (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5. TET1 reprograms the lung cancer cell transcriptome via CpG oxidation-independent mechanism that in part involves chromatin remodeling through H3K9 di-methylation.

The Illumina Whole-Genome Gene Expression BeadChip followed by Ingenuity pathway analysis were used to identify pathways changed in control vs. TET1 knockdown H1299 and A549 cells 96 h after transfection with siRNA (A, B). Genomic DNA isolated from HBEC4, A549, H1975 and H1299 cells was analyzed for 5-hmC levels using Dot blot (C). Levels of di-methylated H3K9 and total H3 with normalization to β-actin were measured using Western blot in control vs. TET1 knockdown H1299 and H1975 cells 72 h after transfection with siRNA (D).

TET1 could regulate some of its target genes via effects on chromatin remodeling-dependent mechanisms involving G9a and PRC2 complexes that act via methylation of histone 3 at lysine 9 and 27, respectively. Western blot analysis showed a 4-fold reduction of the di-methylation repressive mark at H3K9 in TET1 depleted H1299 and H1975 cells 72 h after transfection a time point that is 24-48 h prior to senescence induction (Fig. 5D). No changes were found for other repressive or active histone marks H3K27 tri-methylation or H3K4 di-methylation, respectively or for the histone methyltransferases EZH2 and G9a (Fig. S5). ChIP-seq has identified 349 gene promoters enriched for the histone methyltransferase G9a (25, 26). From this list of G9a regulated genes, 81 and 48 in H1299 and A549 cells showed expression changes in response to TET1 knockdown (Tables S9). In addition, 62 G9a regulated genes were differentially expressed in TET1 high versus TET1 low AdC and SCC tumors (Table S10).

TET1 targeting sensitizes lung cancer cells to therapy-induced senescence and growth reduction.

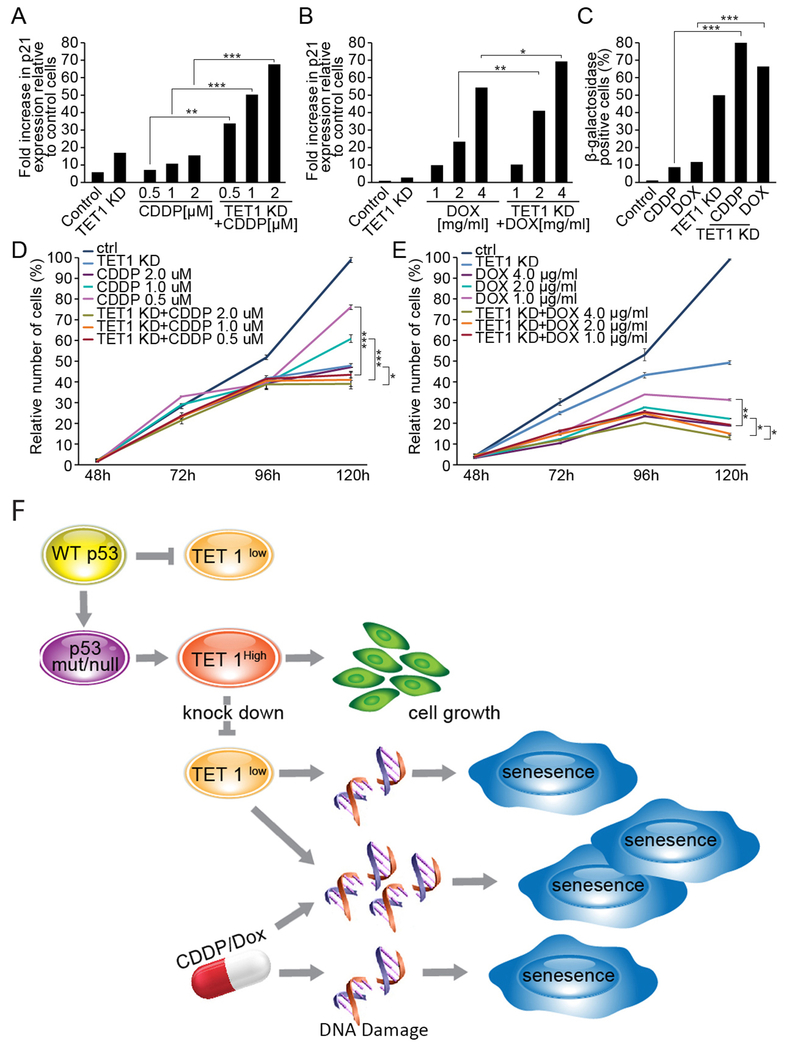

The therapeutic effect of DNA-damaging drugs used as a standard-of-treatment for lung cancer patients is in part a result of senescence induced by those agents (27, 28). Because TET1 expression was found to prevent lung cancer cells from cellular aging, we hypothesized that simultaneous TET1 depletion in conjunction with cisplatin (CDDP) or doxorubicin (DOX) treatment may have additive or synergistic effects on cell growth inhibition. RT-qPCR analysis demonstrated that expression of p21 is elevated 6- to 70-fold in H1299 cells in a highly synergistic and dose-dependent manner by combined TET1 knockdown and chemotherapy treatment (Fig. 6A, B). While treatment with 1 μM of CDDP and 2 μg/ml of DOX induced β-galactosidase positivity in 7% and 8% of cells, respectively, combining treatment with TET1 knockdown elevated β-galactosidase up to 61% and 50%, respectively (Fig. 6C and Fig. S6). Finally, TET1 depletion improved the efficacy of chemotherapy as shown by a reduction in cell number up to 92% (Fig. 6D and Fig. S6). These combinatorial effects of TET1 depletion combined with chemotherapy were also seen with H1975 and H226, AdC and SCC tumor lines, irrespective of the siRNA used to reduce TET1 levels (Fig. S6 & S7).

Fig. 6. TET1 targeting sensitizes lung cancer cells to therapy-induced senescence and growth reduction.

Control vs. TET1 knockdown H1299 cells were incubated with cisplatin (CDDP) or doxorubicin (DOX) 24 h after transfection for 48 h and analyzed for p21 mRNA (A, B). Cells incubated with CDDP or DOX for 96 h (120 h after transfection with control vs. TET1 siRNAs) were analyzed for senescence using the β-galactosidase assay (C) and for total number of cells (D, E). Results are presented as an average of three experiments ±SEM, p *<0.05, **<0.01, or ***<0.001. Statistical comparison was performed for CDDP- vs. TET1 KD+CDDP-treated cells and DOX- vs. TET1 KD+DOX-treated cells. The mechanism of TET1 gene overexpression and function in lung cancer is depicted (F).

Discussion

These studies have identified a new role for the TET1 gene in driving lung cancer malignancy via transcriptome reprograming and control of cell fate. Its elevated expression confers oncogenic properties to lung cancer cells by contributing to sustained growth. The mechanism of TET1 overexpression identifies a new oncosuppresive function for the p53 gene through its repression of TET1 transcription via direct binding to the proximal promoter that is disrupted by p53 mutation. TET1 effects on lung cancer cell fate are mediated in by regulation of genes that prevent genomic instability-associated cellular senescence in the context of mutant p53. In accordance with this regulatory mechanism, cellular depletion of TET1 is synergistic with classic drugs for therapy-induced senescence and further reduces cell growth, findings that could spur development of new combination targeted therapies to improve overall survival in patients with p53 mutant lung cancer (Fig. 6F).

Possible alterations in expression of the TET genes in lung cancer were first suggested by the observation of reduced levels of their enzymatic product 5hmC in tumor versus normal lung tissue (24). That finding was supported by three studies that showed negative correlation between TET1 expression and miR-767, MAPK/miR29b, and EGFR/CEBPα levels across lung tumors of different histology (29–32). However, none of those studies analyzed TET1 levels in primary lung tumors compared to normal tissue. Our extensive characterization of tumor-normal tissue pairs and tumor-normal lung-derived cell lines with validation using TCGA RNA sequence data for tumor and normal lung tissues demonstrated high (2- to 90-fold) and frequent (40% to 70%) overexpression of the TET1 gene at mRNA and protein levels in AdC and SCC tumors. Other studies on TET1 in solid tumors that included breast, gastric, colorectal and liver carcinomas show reduced expression in some tumor tissues (19–22). Those findings illustrate tissue-specific variation in gene regulation and such differences may stem from the high overall frequency for p53 mutation and preponderance for transversion mutations in lung cancer that showed the strongest relationship to elevated TET1 transcription (33). TET1 was previously suggested to increase p53 expression by preventing its promoter methylation in gastric carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (34); however, the opposite relation between these two genes has never been described in human cancers.

The core domain of p53 is only marginally stable at body temperature and mutations that reduce this thermodynamic stability, the majority of which are localized in the central DNA core binding domain, have a profound effect on the amount of folded protein and hence its ability to bind as a transcription factor (35, 36). Our results are consistent with the ensuing thermodynamic instability conferred by mutation through showing that cell lines with p53 mutation have a marked reduction in enrichment of this protein at the TET1 promoter and significantly higher transcription than cell lines with wild type p53. While p53 plays a profound role in TET1 regulation, it is evident from our studies that other mechanisms also contribute to elevated TET1 expression in lung cancer as some cell lines with WT p53 expression are characterized by higher TET1 levels than normal lung epithelial cells. The potential role of well-established oncogenes frequently overexpressed in lung cancers (e.g. AP-2, Foxp3, STAT4, and c-Jun) and found to have a predicted binding site within the TET1 minimal promoter warrant evaluation in future studies as regulators of transcription.

Mutation of p53 makes the cancer cell insensitive to cellular senescence and our findings implicate overexpression of TET1, a consequence of p53 mutation, as a major contributing factor to this paradigm (37). Multiple studies have demonstrated an important role of 5-hmC turn over, catalyzed by TET genes in regulating pluripotency and differentiation of embryonic stem cells and developing embryos (38, 39). In postnatal development, TET1 was shown to be important for differentiation and cell fate reprogramming of neurons and for mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition of mouse fibroblasts (40, 41). Our findings show for the first time that TET1 prevents cancer cells from entering a terminal differentiation stage manifested by aged morphology, β-galactosidase activity and elevated p21 expression.

The mechanism of TET1 depletion-induced senescence in the context of p53 mutation was investigated in detail. Surprisingly, no single pathway described in the literature to induce p53-independent cellular aging (e.g. SP1/Sp2, ZBTB2/4, FMN2, Rb, TGF-β, PI3K/AKT, c-Myc, CHK2 modulated through siRNA or pharmacological inhibition was found to regulate cell fate reprograming downstream from TET1 (Table S11 [42–46]). Instead, the expression of a large number of genes predominantly involved in DNA repair, cell cycle regulation, and survival/cell death pathways were altered when TET1 protein was reduced. These global changes in the cell transcriptome were accompanied by genomic instability resulting from DNA double-strand break accumulation. These results suggest that growth arrest caused by TET1 depletion is not mediated by any of the canonical mechanisms, but through a new mode of senescence triggered by simultaneous dysregulation of multiple pathways and DNA damage. Cells lacking WT p53, a critical guardian of genomic integrity, have initially elevated levels of DNA damage that makes them susceptible to TET1 depletion-induced senescence. Our results showing synergism of TET1 and p53 knockdown in elevating micronuclei, p21, and β-galactosidase positivity in A549 with WT p53 support this premise (47). Although the cause of dysregulation of genes after TET1 depletion is not fully characterized, this study suggests that it likely involves a previously undescribed epigenetic mechanism that is 5-mC oxidation-independent. While no substantial differences in 5-mC and 5-hmC were found, TET1 knockdown significantly and specifically reduced the chromatin di-methylation repressive mark at H3K9 that may regulate a subset of genes whose expression was increased. Future ChIP-seq studies will investigate in detail a potential mechanistic link between TET1 and H3K9me2.

Induction of a senescent phenotype resulting from TET1 depletion is potentially a very desirable effect from the perspective of anticancer treatment. Therapy-induced senescence is effective in p53/Rb mutant tumors, may offer the advantage of reduced toxicity-related side effects, increased tumor-specific immunity, and is more likely to cause stable tumor remission after treatment cessation because of the irreversible nature of growth arrest (48). Further, unlike cell death-inducing strategies, senescence-oriented treatment does not create post-necrotic niches within tumors that can allow for clonal expansion of resistant cells that survived the treatment, but rather make the tumor benign and potentially easier to resect (48). Substantially reduced proliferation, colony formation, and tumor growth in response to TET1 depletion demonstrated in this study support TET1 targeting as a novel strategy to induce or exaggerate the rate of senescence in the subset of lung cancer harboring p53-mutation. Those cancers are characterized by poor prognosis and lower survival rate as the result of worse therapeutic response compared to tumors with WT p53 (49). Cisplatin and doxorubicin, two commonly used genotoxic drugs for the treatment of lung cancer act in part via senescence induction (46). Combining these drugs with knockdown of TET1 showed strong synergism for senescence induction and increased growth inhibition, findings that could have broad translation for impacting lung cancer. In this new era of precision medicine, the development of a small molecule inhibitor to disrupt TET1 function in conjunction with genotoxic drugs may offer a more efficacious therapeutic strategy for improving overall survival of lung cancer patients with p53 mutation.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

These studies identify TET1 as an oncogene in lung cancer whose gain of function following loss of p53 may be exploited by targeted therapy-induced senescence.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health R01 CA183296 to SAB and in part by P30 CA11800 through a subcontract to SAB.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest disclosed.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belinsky SA. Unmasking the lung cancer epigenome. Annu Rev Physiol 2015;77:453–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones PA, Issa JP, Baylin S. Targeting the cancer epigenome for therapy. Nat Rev Genet 2016;17:630–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood KH, Zhou Z. Emerging molecular and biological functions of MBD2, a reader of DNA methylation. Front Genet 2016;7:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akiyama Y, Watkins N, Suzuki H, Jair KW, van Engeland M, Esteller M, et al. GATA-4 and GATA-5 transcription factor genes and potential downstream antitumor target genes are epigenetically silenced in colorectal and gastric cancer. Mol Cell Biol 2003;23:8429–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merlo A, Herman JG, Mao L, Lee DJ, Gabrielson E, Burger PC, et al. 5’ CpG island methylation is associated with transcriptional silencing of the tumour suppressor p16/CDKN2/MTS1 in human cancers. Nat Med 1995;1:686–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delatte B, Deplus R, Fuks F. Playing TETris with DNA modifications. EMBO J 2014;33: 1198–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kohli RM, Zhang Y. TET enzymes, TDG and the dynamics of DNA demethylation. Nature 2013;502:472–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carey BW, Finley LW, Cross JR, Allis CD, Thompson CB. Intracellular alpha-ketoglutarate maintains the pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature 2015;518:413–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chapman CG, Mariani CJ, Wu F, Meckel K, Butun F, Chuang A, et al. TET-catalyzed 5-hydroxymethylcytosine regulates gene expression in differentiating colonocytes and colon cancer. Sci Rep 2015;5:17568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wille CK, Nawandar DM, Henning AN, Ma S, Oetting KM, Lee D, et al. 5-hydroxymethylation of the EBV genome regulates the latent to lytic switch. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015;112:E7257–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai YP, Chen HF, Chen SY, Cheng WC, Wang HW, Shen ZJ, et al. TET1 regulates hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition by acting as a co-activator. Genome Biol 2014;15:513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin C, Lu Y, Jelinek J, Liang S, Estecio MR, Barton MC, et al. TET1 is a maintenance DNA demethylase that prevents methylation spreading in differentiated cells. Nucleic Acids Res 2014; 42:6956–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neri F, Incarnato D, Krepelova A, Rapelli S, Pagnani A, Zecchina R, et al. Genome-wide analysis identifies a functional association of Tet1 and Polycomb repressive complex 2 in mouse embryonic stem cells. Genome Biol 2013;14:R91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams K, Christensen J, Pedersen MT, Johansen JV, Cloos PA, Rappsilber J, et al. TET1 and hydroxymethylcytosine in transcription and DNA methylation fidelity. Nature 2011; 473:343–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ficz G, Gribben JG. Loss of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in cancer: cause or consequence? Genomics 2014;104:352–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang H, Jiang X, Li Z, Li Y, Song CX, He C, et al. TET1 plays an essential oncogenic role in MLL-rearranged leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:11994–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science 2009;324:930–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu HL, Ma Y, Lu LG, Hou P, Li BJ, Jin WL, et al. TET1 exerts its tumor suppressor function by interacting with p53-EZH2 pathway in gastric cancer. J Biomed Nanotechnol 2014;10:1217–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu C, Liu L, Chen X, Shen J, Shan J, Xu Y, et al. Decrease of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is associated with progression of hepatocellular carcinoma through downregulation of TET1. PLoS One 2013;8:e62828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neri F, Dettori D, Incarnato D, Krepelova A, Rapelli S, Maldotti M, et al. TET1 is a tumour suppressor that inhibits colon cancer growth by derepressing inhibitors of the WNT pathway. Oncogene 2015;34:4168–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun M, Song CX, Huang H, Frankenberger CA, Sankarasharma D, Gomes S, et al. HMGA2/TET1/HOXA9 signaling pathway regulates breast cancer growth and metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:9920–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sohni A, Bartoccetti M, Khoueiry R, Spans L, Vande Velde J, De Troyer L, et al. Dynamic switching of active promoter and enhancer domains regulates Tet1 and Tet2 expression during cell state transitions between pluripotency and differentiation. Mol Cell Biol 2015;35:1026–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang H, Liu Y, Bai F, Zhang JY, Ma SH, Liu J, et al. Tumor development is associated with decrease of TET gene expression and 5-methylcytosine hydroxylation. Oncogene 2013;32:663–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yokoyama M, Chiba T, Zen Y, Oshima M, Kusakabe Y, Noguchi Y, et al. Histone lysine methyltransferase G9a is a novel epigenetic target for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2017;8:21315–21326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yue F, Cheng Y, Breschi A, Vierstra J, Wu W, Ryba T, et al. A comparative encyclopedia of DNA elements in the mouse genome. Nature 2014;515:355–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ewald JA, Desotelle JA, Wilding G, Jarrard DF. Therapy-induced senescence in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:1536–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su D, Zhu S, Han X, Feng Y, Huang H, Ren G, et al. BMP4-Smad signaling pathway mediates adriamycin-induced premature senescence in lung cancer cells. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 12153–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forloni M, Gupta R, Nagarajan A, Sun LS, Dong Y, Pirazzoli V, et al. Oncogenic EGFR represses the TET1 DNA demethylase to induce silencing of tumor suppressors in cancer cells. Cell Rep 2016;16:457–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loriot A, Van Tongelen A, Blanco J, Klaessens S, Cannuyer J, van Baren N, et al. A novel cancer-germline transcript carrying pro-metastatic miR-105 and TET-targeting miR-767 induced by DNA hypomethylation in tumors. Epigenetics 2014;9:1163–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor MA, Wappett M, Delpuech O, Brown H, Chresta CM. Enhanced MAPK signaling drives ETS1-mediated induction of miR-29b leading to downregulation of TET1 and changes in epigenetic modifications in a subset of lung SCC. Oncogene 2016;35:4345–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu BK, Brenner C. Suppression of TET1-dependent DNA demethylation is essential for KRAS-mediated transformation. Cell Rep 2014;9:1827–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soussi T, Beroud C. Assessing TP53 status in human tumours to evaluate clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer 2001;1:233–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li H, Zhou ZQ, Yang ZR, Tong DN, Guan J, Shi BJ, et al. MicroRNA-191 acts as a tumor promoter by modulating the TET1-p53 pathway in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology 2017;66:136–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joerger AC, Fersht AR., Structure-function-rescue: the diverse nature of common p53 cancer mutants. Oncogene 2007;26:2226–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joerger AC, Fersht AR. The tumor suppressor p53: from structures to drug discovery. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2010;2:a000919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qian Y, Chen X. Senescence regulation by the p53 protein family. Methods Mol Biol 2013;965:37–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cimmino L, Abdel-Wahab O, Levine RL, Aifantis I. TET family proteins and their role in stem cell differentiation and transformation. Cell Stem Cell 2011;9:193–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu H, D’Alessio AC, Ito S, Xia K, Wang Z, Cui K, et al. Dual functions of Tet1 in transcriptional regulation in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature 2011;473:389–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu X, Zhang L, Mao SQ, Li Z, Chen J, Zhang RR, et al. Tet and TDG mediate DNA demethylation essential for mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition in somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 2014;14:512–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang RR, Cui QY, Murai K, Lim YC, Smith ZD, Jin S, et al. Tet1 regulates adult hippocampal neurogenesis and cognition. Cell Stem Cell 2013;13:237–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campaner S, Doni M, Hydbring P, Verrecchia A, Bianchi L, Sardella D, et al. Cdk2 suppresses cellular senescence induced by the c-myc oncogene. Nat Cell Biol 2010;12:54–9; suppl 1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Decesse JT, Medjkane S, Datto MB, Crémisi CE. RB regulates transcription of the p21/WAF1/CIP1 gene. Oncogene 2001;20:962–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gartel AL, Goufman E, Najmabadi F, Tyner AL. Sp1 and Sp3 activate p21 (WAF1/CIP1) gene transcription in the Caco-2 colon adenocarcinoma cell line. Oncogene 2000;19:5182–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lafaye C, Barbier E, Miscioscia A, Saint-Pierre C, Kraut A, Couté Y, et al. DNA binding of the p21 repressor ZBTB2 is inhibited by cytosine hydroxymethylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014;446:341–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Munoz-Espin D, Serrano M. Cellular senescence: from physiology to pathology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014;15:482–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kasiappan R, Shih HJ, Chu KL, Chen WT, Liu HP, Huang SF, et al. Loss of p53 and MCT-1 overexpression synergistically promote chromosome instability and tumorigenicity. Mol Cancer Res 2009;7:536–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nardella C, Clohessy JG, Alimonti A, Pandolfi PP. Pro-senescence therapy for cancer treatment. Nat Rev Cancer 2011;11:503–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gu J, Zhou Y, Huang L, Ou W, Wu J, Li S, et al. TP53 mutation is associated with a poor clinical outcome for non-small cell lung cancer: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Mol Clin Oncol 2016;5:705–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.