Abstract

A general approach to site-specific insertion of amino acid analogues into proteins in vivo would be the import into cells of a suppressor tRNA aminoacylated with the analogue of choice. The analogue would be inserted at any site in the protein specified by a stop codon in the mRNA. The only requirement is that the suppressor tRNA must not be a substrate for any of the cellular aminoacyl–tRNA synthetases. Here, we describe conditions for the import of amber and ochre suppressor tRNAs derived from Escherichia coli initiator tRNA into mammalian COS1 cells, and we present evidence for their activity in the specific suppression of amber (UAG) and ochre (UAA) codons, respectively. We show that an aminoacylated amber suppressor tRNA (supF) derived from the E. coli tyrosine tRNA can be imported into COS1 cells and acts as a suppressor of amber codons, whereas the same suppressor tRNA imported without prior aminoacylation does not, suggesting that the supF tRNA is not a substrate for any mammalian aminoacyl–tRNA synthetase. These results open the possibility of using the supF tRNA aminoacylated with an amino acid analogue as a general approach for the site-specific insertion of amino acid analogues into proteins in mammalian cells. We discuss the possibility further of importing a mixture of amber and ochre suppressor tRNAs for the insertion of two different amino acid analogues into a protein and the potential use of suppressor tRNA import for treatment of some of the human genetic diseases caused by nonsense mutations.

The site-specific insertion of amino acid analogues into proteins in vitro has been used successfully for a number of applications (1–6). The most common approach involves the read-through of an amber stop codon by an amber suppressor tRNA, which is chemically aminoacylated with the analogue of choice. Another approach has been the use of an mRNA with four base codons, along with chemically aminoacylated mutant tRNAs with cognate four base anticodons (7, 8). This latter approach has allowed the site-specific insertion of two different amino acid analogues into a protein in vitro (8).

The development of methods for site-specific insertion of amino acid analogues into proteins in vivo would greatly expand the scope and utility of unnatural amino acid mutagenesis (9, 10). In particular, the availability of in vivo systems would open the possibility of in vivo structure–function studies, including studies of protein–protein interactions, protein localizations, etc., through the use of amino acid analogues that carry photoactivatable groups, fluorescent groups, and other chemically reactive groups.

One approach for in vivo work relies on a suppressor tRNA aminoacylated with an amino acid analogue by a mutant aminoacyl–tRNA synthetase (aaRS). The analogue is inserted at a site in the protein specified by a stop codon in the mRNA. Two key requirements of this approach are (i) a suppressor tRNA, which is not aminoacylated by any of the endogenous aaRSs in the cell, and (ii) an aaRS, which aminoacylates the suppressor tRNA but no other tRNA in the cell. A number of such 21st synthetase–suppressor tRNA pairs have been developed recently for possible use in eubacteria and in eukaryotes (9–12). The next step is isolation of mutants in the 21st aaRS, which aminoacylate the suppressor tRNA with the amino acid analogue of choice instead of the normal amino acid. A major advance in this approach has been the recent isolation of a mutant of Methanococcus jannaschii tyrosyl–tRNA synthetase (TyrRS), which aminoacylates an amber suppressor derived from tyrosine tRNA of the same organism with O-methyl tyrosine instead of tyrosine (13). By using this 21st synthetase–tRNA pair, Schultz and coworkers have achieved the site-specific insertion of O-methyl tyrosine into a reporter protein in Escherichia coli.

The above approach using 21st synthetase–tRNA pairs requires the isolation, one at a time, of mutants in the 21st aaRS, which activate the amino acid analogue and attach it to the suppressor tRNA instead of the normal amino acid. A further requirement is that the amino acid analogue should be readily imported into the organism of choice. Although the successful isolation of the desired mutant in the M. jannaschii gene for TyrRS opens the possibility of extension of this approach to other amino acid analogues (13), it is possible that this approach will be restricted to amino acid analogues that are closely related in size and structure to the normal amino acid. An alternative approach that does not require a mutant aaRS and that has the potential of being generally applicable for a number of purposes would be the import into cells of suppressor tRNAs chemically aminoacylated with the amino acid analogue of choice. This method also does not rely on uptake of the desired amino acid analogue from the medium into cells. The only requirement is that the suppressor tRNA must not be aminoacylated by any of the aaRSs in the cell. An important step along these lines has been taken by Dougherty, Lester, and coworkers, who have injected chemically aminoacylated suppressor tRNAs into individual Xenopus oocytes for site-specific insertion of amino acid analogues into membrane receptor and ion channel proteins for structure–function studies (14). The availability of a method for import of suppressor tRNAs into cells other than Xenopus oocytes and using procedures other than injection into individual cells, one at a time, would greatly expand the scope of these experiments (15). Here, we describe the import of amber and ochre suppressor tRNAs into mammalian cells and show that they suppress specifically the amber and ochre codons, respectively, in a reporter mRNA. We also demonstrate that aminoacylated amber suppressor tRNA derived from E. coli tyrosine tRNA can be imported into mammalian cells, where it acts as a suppressor of amber codons, whereas the same suppressor tRNA imported without prior aminoacylation does not. These findings form the basis of a general method for the site-specific insertion of a variety of amino acid analogues into proteins in mammalian cells.

Materials and Methods

General.

Standard genetic techniques were used for cloning (16). E. coli strains DH5α (17) and XL1-Blue (18) were used for plasmid propagation and isolation. For transfection of mammalian cells, plasmid DNAs were purified by using an EndoFree Plasmid Maxi kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). Oligonucleotides were from Genset Oligos (La Jolla, CA), and radiochemicals were from New England Nuclear.

Plasmids Carrying Reporter Genes.

pRSVCAT and pRSVCATam27 and pRSVCAToc27, carrying amber and ochre mutations, respectively, at codon 27 of the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene, have been described previously (19).

Plasmids Carrying Suppressor tRNA Genes.

The plasmid pRSVCAT/trnfM U2:A71/U35A36/G72 contains the gene for

the amber suppressor derived from the E. coli

tRNAfMet (20). An ochre suppressor was generated

from this plasmid by mutation of C34 to U34 in the tRNA gene by using

the QuikChange mutagenesis protocol (Stratagene). The plasmid pCDNA1

(Invitrogen) contains the gene for the supF amber suppressor

derived from E. coli tRNA (21).

(21).

Purification of Suppressor tRNAs.

For purification of the amber suppressor tRNA derived from E. coli tRNAfMet, total tRNA (597 A260 units) was isolated by phenol extraction of cell pellet from a 2-liter culture of E. coli B105 cells (22) carrying the plasmid pRSVCAT/trnfM U2:A71/U35A36/G72 (20). The suppressor tRNA was purified by electrophoresis of 80 A260 unit aliquots of the total tRNA on 12% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels (0.15 × 20 × 40 cm) (23). The purified tRNA was eluted from the gel with 10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4) and concentrated by adsorption to a column of DEAE–cellulose followed by elution of the tRNA with 1 M NaCl and precipitation with ethanol. The same procedure was used for purification of the ochre suppressor tRNA.

supF tRNA (21) was purified from E. coli strain MC1061p3 carrying the plasmid pCDNA1. Total tRNA (1,000 A260 units) isolated by phenol extraction of cell pellet from a 3-liter culture was dissolved in 10 ml of buffer A [50 mM NaOAc (pH 4.5)/10 mM MgCl2/1 M NaCl] and applied to a column (1.5 × 15 cm) of benzoylated and naphthoylated DEAE–cellulose (Sigma) equilibrated with the same buffer. The column was then washed with 500 ml of the same buffer. The supF tRNA and wild-type tRNATyr were eluted with a linear gradient (total volume 500 ml) from buffer A to buffer B [50 mM NaOAc (pH 4.5)/10 mM MgCl2/1 M NaCl/20% ethanol]. The separation of supF tRNA from tRNATyr was monitored by acid urea gel electrophoresis of column fractions followed by RNA blot hybridization. Fractions containing supF tRNA free of tRNATyr were pooled.

The purity of all three suppressor tRNAs was greater than 85%, as determined by assaying for amino acid acceptor activity and by PAGE.

In Vitro Aminoacylation and Isolation of Aminoacyl-tRNAs.

The U2:A71/U35A36/G72 mutant tRNAfMet (1 A260 unit) was aminoacylated with tyrosine in a buffer containing 30 mM Hepes⋅KOH (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 8 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 3 mM ATP, 0.4 mM tyrosine, 0.18 mg/ml of BSA, 1 unit of inorganic pyrophosphatase, and 20 μg of purified yeast TyrRS (10) in a total volume of 0.4 ml. Aminoacylation of supF tRNA (1 A260 unit) was performed in 50 mM Hepes⋅KOH (pH 7.5)/100 mM KCl/10 mM MgCl2/5 mM DTT/4 mM ATP/25 μM tyrosine/0.18 mg/ml of BSA/1 unit of inorganic pyrophosphatase/20 units of purified E. coli TyrRS in a total volume of 0.4 ml. Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, extracted with phenol equilibrated with 10 mM NaOAc (pH 4.5), and the concentration of NaOAc in the aqueous layer was raised to 0.3 M. The aminoacyl–tRNA was then precipitated with 2 volumes of ethanol. The tRNA was dialyzed against 5 mM NaOAc (pH 4.5), reprecipitated with ethanol, and dissolved in sterile water.

Transfection of COS-1 Cells.

Cells were cultured in DMEM (with 4,500 mg/liter of glucose and 4 mM l-glutamine; Sigma) supplemented with 10% calf serum (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD), 50 units/ml of penicillin, and 50 μg/ml of streptomycin (both Life Technologies) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Eighteen to twenty-four hours before transfection, cells were subcultured in 12-well dishes. Transfection reagent Effectene (Qiagen) was used according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, cells at ≈30% confluence were transfected with a mixture comprising 1.25 μg of plasmid DNA carrying the reporter gene and 0–5 μg of suppressor tRNA. The mixture of plasmid DNA and tRNA was diluted with EC buffer, supplied by the manufacturer, to a total volume of 50 μl, incubated for 5 min, then mixed with Enhancer (1 μl per microgram of total nucleic acids), and incubated for a further 5 min. Effectene (2 μl per micrograms of total nucleic acids) was added, and the mixture was incubated for 10 min to allow for Effectene–nucleic acid complex formation. All of the above steps were carried out at room temperature (25°C). The complexes were diluted with prewarmed (37°C) DMEM to a total volume of 0.5 ml and added immediately to the cells. One milliliter of medium supplemented with serum and antibiotics was added 6 h after transfection. Cells were harvested 24–30 h posttransfection.

Assay for CAT Activity.

Transfected cells were harvested by adding 0.5 ml of 140 mM NaCl/20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4)/10 mM EDTA. Cells were then pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in 30 μl of 0.25 M Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.0), and lysed by multiple freeze–thaw cycles. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation, and the protein concentration of the supernatants was determined (BCA protein assay; Pierce) by using BSA as standard. Total protein extract (0.5–30 μg) in a volume of 20 μl was incubated for 10 min at 65°C and quick-chilled on ice. The standard reaction (50 μl) contained 20 μl of extract, 0.64 mM acetyl CoA, and 1.75 nmol of [14C]-chloramphenicol in 0.5 M Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.0). After 1 h at 37°C, the reaction was terminated by addition of ethyl acetate and mixing. The ethyl acetate layer was evaporated to dryness, dissolved in ethyl acetate (5 μl), and the solution was applied onto silica gel plates for chromatography with chloroform/methanol (95:5) as the solvent. After autoradiography, radioactive spots were excised from the plate, and the radioactivity was quantitated by liquid scintillation counting.

Analysis of in Vivo State of tRNAs.

Total RNAs were isolated from COS1 cells under acidic conditions by using TRI-Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati). tRNAs were separated by acid urea PAGE (24) and detected by RNA blot hybridization by using 5′-32P-labeled oligonucleotides.

Results

Import of Amber Suppressor tRNA into Mammalian COS1 Cells.

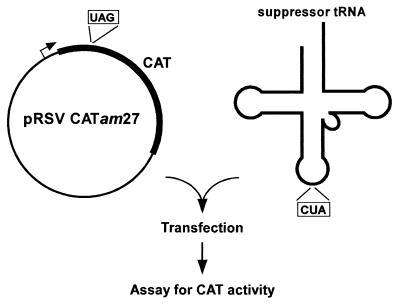

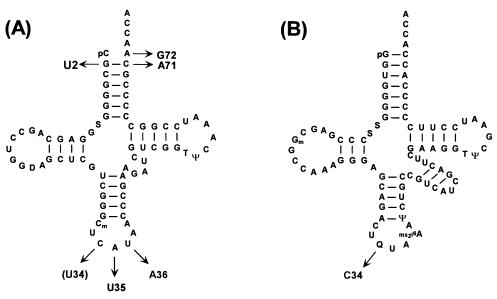

The assay for import and function of the amber suppressor tRNA (Fig. 1) consisted of cotransfection of COS1 cells with the suppressor tRNA along with the pRSVCATam27 DNA carrying an amber mutation at codon 27 of the CAT gene followed by measurement of CAT activity in cell extracts. The suppressor tRNA used (Fig. 2A) is derived from the E. coli initiator tRNAfMet and has mutations in the acceptor stem and the anticodon sequence. This tRNA is part of a 21st synthetase–tRNA pair that we developed previously for use in E. coli (10). The G72 mutation in the acceptor stem allows it to act as an elongator tRNA, and the U35A36 mutations in the anticodon sequence allow it to read the UAG codon (25). Because the suppressor tRNA contains the C1:G72 base pair, which is one of the critical determinants for eukaryotic TyrRSs, it is aminoacylated in vivo with tyrosine by yeast (20, 26) and in vitro by human (27) and COS1 cell TyrRS (data not shown) and is, therefore, expected to be aminoacylated, at least to some extent, with tyrosine in mammalian cells. The tRNA is active in suppression of amber codons in yeast (20) and is, therefore, likely to be active in suppression of amber codons in mammalian cells. The tRNA was purified by electrophoresis on 12% polyacrylamide gels and used as such. The methods or reagents used for transfection included electroporation, DEAE-dextran, calcium phosphate, Superfect, Polyfect, Effectene, Lipofectamine, Oligofectamine, or DMRIE-C, a 1:1 (M/M) mixture of 1,2-dimyristyloxypropyl-3-dimethyl-hydroxyethyl ammonium bromide with cholesterol. No CAT activity was detected in extracts of cells cotransfected by using electroporation, DEAE-dextran, calcium phosphate, Superfect, or Polyfect. Among the other reagents used, CAT activity was highest (by a factor of >25-fold compared with others) in extracts of cells cotransfected by using Effectene (data not shown). The experiments described below for import and function of the suppressor tRNAs were, therefore, all carried out in the presence of Effectene.

Figure 1.

Assay for import and function of amber suppressor tRNA.

Figure 2.

(A) Cloverleaf structures of amber and ochre suppressor tRNAs derived from E. coli initiator tRNAfMet. The ochre suppressor contains the U34 mutation (in parentheses), in addition to the other mutations present in the amber suppressor tRNA. The nucleotide modifications, including ms2i6A at position 37 not shown, are established for the amber suppressor tRNA (47) but not for the ochre suppressor tRNA. (B) The supF amber suppressor tRNA derived from E. coli tyrosine tRNA. Arrows indicate the sequence changes in the suppressor tRNAs.

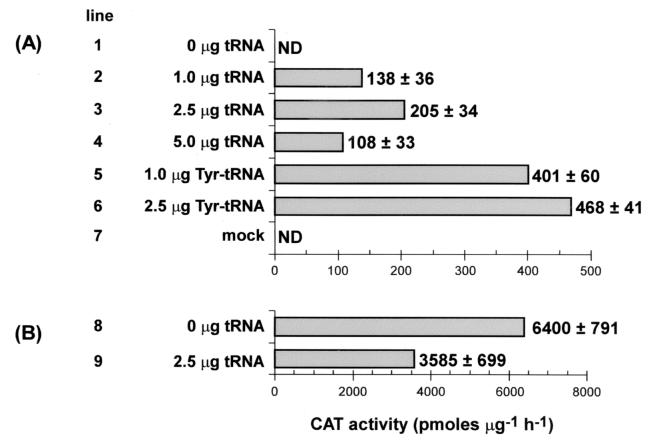

Fig. 3A shows the results of assay for CAT activity in extracts of cells cotransfected with a fixed amount of the pRSVCATam27 plasmid DNA and varying amounts of the suppressor tRNA. Synthesis of CAT requires the presence of the suppressor tRNA during transfection (compare line 1 with lines 2–4). CAT activity reaches a maximum with 2.5 μg of the suppressor tRNA; with 5 μg of the suppressor tRNA, there is a substantial drop in CAT activity (Fig. 3A, lines 3 and 4). This drop in CAT activity is most likely because of an effect of the increased amount of the tRNA on efficiency of cotransfection of the plasmid DNA, because a similar effect of the tRNA is seen on cotransfection of the wild-type plasmid DNA (Fig. 3B, lines 8 and 9). The CAT activity in extracts of cells transfected with 2.5 μg of the suppressor tRNA is about 6% of that in cells cotransfected with the wild-type pRSVCAT plasmid and the same amount of the suppressor tRNA (Fig. 3 A and B, lines 3 and 9). This result is most likely a reflection of the extent of aminoacylation of the suppressor tRNA, the efficiency of amber suppression at this site with the tRNA used and efficiencies of cotransfection of both the plasmid DNA and the suppressor tRNA into COS1 cells.

Figure 3.

CAT activity in extracts of cells cotransfected with the pRSVCATam27 DNA and varying amounts of amber suppressor tRNA, with or without aminoacylation (A), and the wild-type pRSVCAT DNA with or without the amber suppressor tRNA (B). The CAT activities are the average of three independent experiments. ND, not detectable.

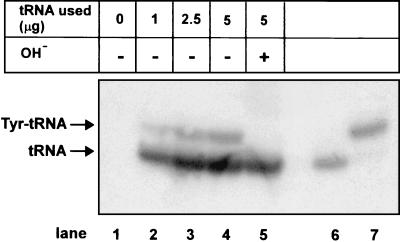

RNA blot hybridization followed by PhosphorImager analysis of the blot shows that only 8.6% of the suppressor tRNA is aminoacylated in COS1 cells (Fig. 4). Thus, aminoacylation of the tRNA is likely one of the factors limiting the extent of suppression of the amber mutation in the CAT gene. Further support for this conclusion comes from experiments described below by using the ochre suppressor derived from the same tRNA and aminoacylated amber suppressor tRNA.

Figure 4.

Acid urea gel analysis of tRNA isolated from cells cotransfected with pRSVCATam27 DNA and increasing amounts of the amber suppressor tRNA derived from the E. coli tRNAfMet (lanes 1–5). Lane 5 contains the same sample as lane 4 except that the aminoacyl linkage to the tRNA was hydrolyzed by base treatment (OH−). Lanes 6 and 7 provide markers of tRNA and Tyr-tRNA, respectively.

Import of Ochre Suppressor tRNA into COS1 Cells.

The amber suppressor tRNA described above was further mutated in the anticodon (C34 to U34) to generate an ochre suppressor tRNA (Fig. 2A). The import and function of the ochre suppressor tRNA were monitored by cotransfection of COS1 cells with the suppressor tRNA and the pRSVCAToc27 plasmid DNA. Results of experiments carried out in parallel with the ochre and amber suppressor tRNAs show that the ochre suppressor tRNA is about 2-fold more active in suppression of the ochre codon than is the amber suppressor tRNA in suppression of the amber codon (Table 1). This finding is most likely because the ochre suppressor tRNA is a better substrate for yeast and mammalian TyrRS than the amber suppressor tRNA (data not shown). Both the amber and ochre suppressor tRNAs are specific in suppression of the corresponding codons (Table 1). These results appear, at the outset, to be consistent with the known specificity of amber and ochre suppressors in eukaryotes for the corresponding codons (19, 28). However, in E. coli, although amber suppressor tRNAs are known to be specific for amber codons, ochre suppressor tRNAs can also read amber codons (29, 30). Therefore, the finding here that an ochre suppressor tRNA isolated from E. coli is specific for an ochre codon in a mammalian cell is surprising and needs further study. Measurements of CAT activity shown on Table 1 were carried out by using 2.5 μg of protein in the COS1 cell extracts. Use of 10-fold more protein in the assay still failed to detect CAT activity in extracts from cells transfected with the ochre suppressor tRNA along with the pRSVCATam27 plasmid DNA.

Table 1.

Activities and specifities of amber and ochre suppressor tRNAs in suppression of amber and ochre codons

| Plasmid | Suppressor tRNA | Micrograms of tRNA used | CAT activity* |

|---|---|---|---|

| pRSVCATam27 | Amber | 0 | ND |

| 2.5 | 90.4 ± 7.0 | ||

| 5 | 50.6 ± 5.7 | ||

| pRSVCAToc27 | Ochre | 0 | ND |

| 2.5 | 178.3 ± 10.0 | ||

| 5 | 81.3 ± 10.7 | ||

| pRSVCATam27 | Ochre | 0 | ND |

| 2.5 | ND | ||

| 5 | ND | ||

| pRSVCAToc27 | Amber | 0 | ND |

| 2.5 | ND | ||

| 5 | ND |

COS-1 cells were cotransfected with 1.25 μg of plasmid DNA and suppressor tRNA, as indicated. CAT activity is defined as picomoles of chloramphenicol acetylated by 1 μg of protein per hour at 37°C. The values in the table are the average of two independent experiments. Experiments with amber and ochre suppressors were carried out in parallel with a different batch of DMEM and calf serum from that used in Fig. 3. The lower CAT activities with the amber suppressor in these experiments compared to those in Fig. 3 are most likely because of this variation. ND, not detectable.

Import of Aminoacyl–Amber Suppressor tRNA into COS1 Cells.

The approach for site-specific insertion of amino acid analogues into proteins requires the import of suppressor tRNA aminoacylated with the amino acid analogue of choice into mammalian cells. In an attempt to determine whether the aminoacyl-linkage in aminoacyl-suppressor tRNA would survive the time and the conditions of transfection needed for import of the suppressor tRNA, the above experiments were repeated with the amber suppressor tRNA that had been previously aminoacylated with tyrosine by using yeast TyrRS. Comparison of CAT activity in extracts of cells transfected with the amber suppressor tRNA to that in cells transfected with the amber suppressor Tyr-tRNA shows that, at both concentrations of the tRNAs used, CAT activity was significantly higher (2- to 3-fold) in cells transfected with the Tyr-tRNA (Fig. 3A, compare lines 5 and 6 to lines 2 and 3, respectively). These results demonstrate that an aminoacylated amber suppressor tRNA can withstand the time and conditions of transfection needed for import into COS1 cells and insert the amino acid attached to the tRNA to a growing polypeptide chain on the ribosome in response to an amber codon.

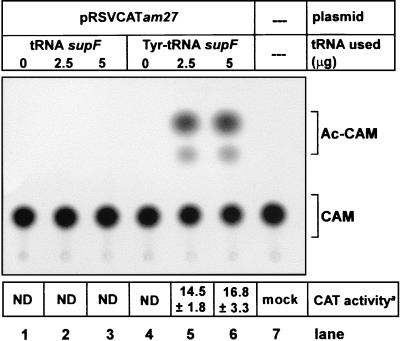

Import of E. coli supF tRNA into COS1 Cells.

The approach for site-specific insertion of amino acid analogues into proteins in mammalian cells by using the import of suppressor tRNA requires that the suppressor tRNA should not be a substrate for any of the mammalian aaRSs. Otherwise, once the suppressor tRNA has inserted the amino acid analogue at a specific site in the protein, it will be reaminoacylated with one of the 20 normal amino acids and will insert this normal amino acid at the same site. Although the amber suppressor tRNA described above proved quite useful for the initial work in determining the conditions necessary for import of both the suppressor tRNA and the reporter plasmid DNA into mammalian cells, the tRNA is a substrate for mammalian TyrRS and is, therefore, not suitable for site-specific insertion of amino acid analogues into proteins in mammalian cells.

The tRNA selected for this purpose was the E. coli supF

tRNA, the amber suppressor tRNA derived from the E. coli

tRNA (Fig. 2B). This tRNA is not

a substrate for yeast, rat liver, or hog pancreas TyrRS (31, 32) or any

of the yeast aaRSs (33). It is also not a substrate for the COS1 cell

TyrRS (data not shown). The supF tRNA was overproduced in

E. coli, purified by column chromatography on benzoylated

and naphthoylated DEAE–cellulose and was aminoacylated with tyrosine

by using E. coli TyrRS. The supF tRNA or

supF Tyr-tRNA was cotransfected into COS1 cells along with

the pRSVCATam27 plasmid DNA, and cell extracts were assayed

for CAT activity. Extracts of cells cotransfected with up to 5 μg of

the supF tRNA had no CAT activity (Fig.

5, lanes 2 and 3). In contrast, extracts

of cells cotransfected with the supF Tyr-tRNA had CAT

activity (Fig. 5, lanes 5 and 6). These results provide the first

indication that an approach involving the import of suppressor tRNA

aminoacylated with an amino acid analogue can form the basis of a

general method for the site-specific insertion of amino acid analogues

into proteins in mammalian cells. The absence of any CAT activity in

cells transfected with the supF tRNA shows that this tRNA is

not an efficient substrate for any of the mammalian aaRSs and fulfills

the requirement described above for the suppressor tRNA to be used for

import into mammalian cells.

(Fig. 2B). This tRNA is not

a substrate for yeast, rat liver, or hog pancreas TyrRS (31, 32) or any

of the yeast aaRSs (33). It is also not a substrate for the COS1 cell

TyrRS (data not shown). The supF tRNA was overproduced in

E. coli, purified by column chromatography on benzoylated

and naphthoylated DEAE–cellulose and was aminoacylated with tyrosine

by using E. coli TyrRS. The supF tRNA or

supF Tyr-tRNA was cotransfected into COS1 cells along with

the pRSVCATam27 plasmid DNA, and cell extracts were assayed

for CAT activity. Extracts of cells cotransfected with up to 5 μg of

the supF tRNA had no CAT activity (Fig.

5, lanes 2 and 3). In contrast, extracts

of cells cotransfected with the supF Tyr-tRNA had CAT

activity (Fig. 5, lanes 5 and 6). These results provide the first

indication that an approach involving the import of suppressor tRNA

aminoacylated with an amino acid analogue can form the basis of a

general method for the site-specific insertion of amino acid analogues

into proteins in mammalian cells. The absence of any CAT activity in

cells transfected with the supF tRNA shows that this tRNA is

not an efficient substrate for any of the mammalian aaRSs and fulfills

the requirement described above for the suppressor tRNA to be used for

import into mammalian cells.

Figure 5.

Thin-layer chromatographic assay for CAT activity in extracts of COS1 cells transfected with pRSVCATam27 DNA (lanes 1 and 4) and supF tRNA, uncharged (lanes 2 and 3) or charged (lanes 5 and 6). Lane 7, mock transfected; Chloramphenicol (CAM), unreacted substrate, and Ac-CAM, the products formed. The CAT activities are the average of two independent experiments. ND, not detectable.

Discussion

As a first step toward the development of a general method for the site-specific insertion of amino acid analogues into proteins in mammalian cells, this paper has focused on the question of whether suppressor tRNAs can be imported into mammalian cells and whether they will be active in suppression of termination codons. We have shown that amber and ochre suppressor tRNAs can be imported into COS1 cells and that they suppress amber and ochre mutations, respectively, at codon 27 of the CAT mRNA. We have further shown that the aminoacylated form of E. coli supF tRNA can be imported and used to suppress an amber codon, whereas the same tRNA imported without prior aminoacylation cannot. These results open up the possibility of using the supF tRNA aminoacylated with an amino acid analogue for the site specific insertion of the amino acid analogue into a protein. Dougherty, Lester, and coworkers (14) have used a similar approach to insert amino acid analogues into membrane proteins in Xenopus oocytes, except they used microinjection for introduction of the aminoacyl-suppressor tRNA into individual oocytes. Here, suppressor tRNAs, uncharged or in the aminoacylated form, are imported directly from the culture medium into mammalian cells. Our success in importing both amber and ochre suppressor tRNAs into mammalian cells allows us to work with different mammalian cell types and to use site-specific insertion of amino acid analogues into proteins for a variety of purposes including structure–function studies of proteins and studies of protein–protein interactions, protein localization, etc.

The approach involving import of aminoacyl-suppressor tRNA for site-specific insertion of amino acid analogues into a protein could be quite general, in that the same suppressor tRNA could be chemically aminoacylated with any amino acid analogue and used to insert the analogue into the protein. The only requirement is that the suppressor tRNA should not be a substrate for any of the mammalian aaRSs. The E. coli supF tRNA used here fulfills this requirement. Because the suppressor tRNA functions only once in insertion of the amino acid analogue, ideally the tRNA should be as efficient as possible in suppression. It would, therefore, be desirable to search for other possible suppressor tRNA candidates for this purpose and compare their activities in suppression to that of the E. coli supF tRNA.

Previous work on site-specific insertion of amino acid analogues into

proteins in vitro or in vivo has mostly relied on

the use of an amber suppressor tRNA aminoacylated with the amino acid

analogue of choice along with an amber codon in the mRNA (1–6, 10, 13,

14). Our finding that an ochre suppressor tRNA can be imported into

mammalian cells and that it functions as an ochre suppressor suggests

that an ochre codon could also be used for site-specific insertion of

amino acid analogues into proteins. Furthermore, the finding that an

ochre suppressor tRNA derived from the E. coli initiator

tRNA suppresses specifically the ochre codon and not the amber codon in

COS1 cells suggests that it might be possible to import two different

suppressor tRNAs and concomitantly suppress an amber codon and an ochre

codon on the same mRNA or on two different mRNAs in COS1 cells.

Assuming that like the supF amber suppressor tRNA, the

supC ochre suppressor tRNA derived from the E.

coli tRNA is also not aminoacylated by any of

the mammalian aaRSs, it might be possible eventually to use a mixture

of supF and supC tRNAs aminoacylated with

different amino acid analogues to insert two different amino acid

analogues into the same protein or different proteins in mammalian

cells. This would greatly expand the scope of experiments possible

in vivo by using site-specific insertion of amino acid

analogues into proteins. Work along these lines is in progress.

is also not aminoacylated by any of

the mammalian aaRSs, it might be possible eventually to use a mixture

of supF and supC tRNAs aminoacylated with

different amino acid analogues to insert two different amino acid

analogues into the same protein or different proteins in mammalian

cells. This would greatly expand the scope of experiments possible

in vivo by using site-specific insertion of amino acid

analogues into proteins. Work along these lines is in progress.

The reagent that we found optimal for the import of both the suppressor tRNA and the reporter plasmid was Effectene in conjunction with a nucleic acid condensing enhancer. Different reagents have been used by others for import of RNA molecules such as mRNAs (34), small nuclear RNAs (35), small interfering RNAs (36), and tRNAs (37) into mammalian cells. A previous study on the import of tRNA used Lipofectin and tRNA as a primer for reverse transcription of mutants of HIV RNA (37). Deutscher and coworkers (38, 39) used electroporation and saponin permeabalization of CHO cells to study the activity of exogenously added aminoacyl tRNAs in protein synthesis and found that the aminoacyl tRNAs worked very poorly, if at all. The current work provides the first report on the import of suppressor tRNAs and, more importantly, aminoacyl–suppressor tRNA for their use in protein synthesis in mammalian cells.

Finally, nonsense mutations are often responsible for a variety of human genetic diseases (40). Approaches that have been considered for treatment of these diseases include aminoglycoside antibiotic induced read-through of the nonsense codon (41) and gene therapy involving suppressor tRNA genes (42, 43) or complementation with a wild-type copy of the gene that was mutated, for example, the dystrophin gene for some patients with muscular dystrophy (44). In transgenic mouse model systems expressing a reporter CAToc27 gene (19) in the heart, under control of the α-myosin heavy chain gene promoter (45), Leinwand and coworkers have shown that injection of plasmid DNA carrying an ochre suppressor tRNA gene directly to the heart myocardium leads to partial suppression of the ochre mutation in the CAT gene (46). Our finding that amber and ochre suppressor tRNAs can be imported into cultured mammalian cells raises the question of whether they can also be imported into cells in animal model systems similar to that used by Leinwand and coworkers (46), and whether the inport of tRNAs leads to suppression of the nonsense mutations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Paul Schimmel, Phil Sharp, and Phil Reeves for comments and suggestions on the manuscript, and Anne Kowal (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) for yeast and E. coli TyrRSs. This work was supported by U.S. Army Research Office grant DAAD19–199-1–0300 and National Institutes of Health Grant R37GM17151.

Abbreviations

- aaRS

aminoacyl–tRNA synthetase

- TyrRS

tyrosyl–tRNA synthetase

- CAT

chloramphenicol acetyl transferase

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Noren C J, Anthony-Cahill S J, Griffith M C, Schultz P G. Science. 1989;244:182–188. doi: 10.1126/science.2649980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bain J D, Glabe C G, Dix T A, Chamberlin A R, Diala E S. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:8013–8014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldini G, Martoglio B, Schachenmann A, Zugliani C, Brunner J. Biochemistry. 1988;27:7951–7959. doi: 10.1021/bi00420a054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellman J, Mendel D, Anthony-Cahill S, Noren C J, Schultz P G. Methods Enzymol. 1991;202:301–336. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)02017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mamaev S V, Laikhter A L, Arslan T, Hecht S M. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:7243–7244. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim D M, Kigawa T, Choi C Y, Yokoyama S. Eur J Biochem. 1996;239:881–886. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0881u.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore B, Persson B C, Nelson C C, Gesteland R F, Atkins J F. J Mol Biol. 2000;298:195–209. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hohsaka T, Ashizuka Y, Sasaki H, Murakami H, Sisido M. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:12194–12195. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu D R, Schultz P G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4780–4785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kowal A K, Köhrer C, RajBhandary U L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2268–2273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031488298. . (First Published January 23, 2001; 10.1073/pnas.031488298) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Magliery T J, Liu D R, Schultz P G. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:5010–5011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drabkin H J, Estrella M, RajBhandary U L. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1459–1466. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L, Brock A, Herberich B, Schultz P G. Science. 2001;292:498–500. doi: 10.1126/science.1060077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nowak M W, Kearney P C, Sampson J R, Saks M E, Labarca C G, Silverman S K, Zhong W G, Thorson J, Abelson J N, Davidson N, et al. Science. 1995;268:439–442. doi: 10.1126/science.7716551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dougherty D A. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2000;4:645–652. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning, A Laboratory Manual. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanahan D. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bullock W O, Fernandez J M, Short J M. BioTechniques. 1987;5:376–379. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capone J P, Sedivy J M, Sharp P A, RajBhandary U L. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:3059–3067. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.9.3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee C P, RajBhandary U L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11378–11382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodman H M, Abelson J, Landy A, Brenner S, Smith J D. Nature (London) 1968;217:1019–1024. doi: 10.1038/2171019a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandal N, RajBhandary U L. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7827–7830. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.23.7827-7830.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seong B L, RajBhandary U L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:334–338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.2.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varshney U, Lee C P, RajBhandary U L. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:24712–24718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seong B L, Lee C P, RajBhandary U L. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:6504–6508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chow C M, RajBhandary U L. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12855–12863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wakasugi K, Quinn C L, Tao N J, Schimmel P. EMBO J. 1998;17:297–305. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sherman F. In: The Molecular Biology of the Yeast Saccharomyces–Metabolism and Gene Expression. Strathern J N, Jones E W, Broach J R, editors. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1982. pp. 463–486. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brenner S, Beckwith J R. J Mol Biol. 1965;13:629–637. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eggertsson G, Söll D. Microbiol Rev. 1988;52:354–374. doi: 10.1128/mr.52.3.354-374.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark J M J, Eyzaguirre J P. J Biol Chem. 1962;237:3698–3702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doctor B P, Mudd J A. J Biol Chem. 1963;238:3677–3681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edwards H, Schimmel P. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:1633–1641. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.4.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malone R W, Felgner P L, Verma I M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6077–6081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.16.6077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kleinschmidt A M, Pederson T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1283–1287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elbashir S M, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, Yalcin A, Weber K, Tuschl T. Nature (London) 2001;411:494–498. doi: 10.1038/35078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu Q, Morrow C D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:4783–4789. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.23.4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Negrutskii B S, Deutscher M P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4491–4995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Negrutskii B S, Stapulionis R, Deutscher M P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:964–968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Atkinson J, Martin R. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1327–1334. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.8.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barton-Davis E R, Cordier L, Shoturma D I, Leland S E, Sweeney H L. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:375–381. doi: 10.1172/JCI7866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Temple G F, Dozy A M, Roy K L, Kan Y W. Nature (London) 1982;296:537–540. doi: 10.1038/296537a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Panchal R G, Wang S, McDermott J, Link C J. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:2209–2219. doi: 10.1089/10430349950017194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phelps S F, Hauser M A, Cole N M, Rafael J A, Hinkle R T, Faulkner J A, Chamberlain J S. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1251–1258. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.8.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vikstrom K L, Factor S M, Leinwand L A. Mol Med. 1996;2:556–567. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buvoli M, Buvoli A, Leinwand L A. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3116–3124. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.3116-3124.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mangroo D, Limbach P A, McCloskey J A, RajBhandary U L. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2858–2862. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2858-2862.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]