Abstract

Background:

Medical establishments in the neighborhood, such as pharmacies and primary care clinics, may play a role in improving access to preventive care and treatment and could explain previously reported neighborhood variations in sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) incidence and survival.

Methods:

The Cardiac Arrest Blood Study Repository is a population-based repository of data from adult cardiac arrest patients and population-based controls residing in King County, Washington. We examined the association between the availability of medical facilities near home with SCA risk, using adult (age 18–80) Seattle residents experiencing cardiac arrest (n=446) and matched controls (n=208) without a history of heart disease. We also analyzed the association of major medical centers near the event location with emergency medical service (EMS) response time and survival among adult cases (age 18+) presenting with ventricular fibrillation from throughout King County (n=1537). The number of medical facilities per census tract was determined by geocoding business locations from the National Establishment Time-Series longitudinal database 1990 to 2010.

Results:

More pharmacies in the home census tract was unexpectedly associated with higher odds of SCA (OR:1.28, 95% CI: 1.03, 1.59), and similar associations were observed for other medical facility types. The presence of a major medical center in the event census tract was associated with a faster EMS response time (−53 seconds, 95% CI: −84, −22), but not with short-term survival.

Conclusions:

We did not observe a protective association between medical facilities in the home census tract and SCA risk, or between major medical centers in the event census tract and survival.

Background

Out-of-hospital sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) is a major cause of death in the United States. Of the 326,200 Americans suffering SCA in 2015, only 10.6% survived [1]. Disparities in SCA incidence and survival by race [2, 3] and individual socioeconomic status (SES) have been described [4]. Neighborhood SES and racial/ethnic composition are also linked to SCA incidence and survival [5–9]. Bystander-initiated cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), a key determinant of SCA survival, has been shown to vary substantially between neighborhoods [5, 10], but does not appear to fully explain geographic patterns and socioeconomic gradients in SCA survival. Identifying modifiable aspects of the local environment can support efforts to improve population-level SCA outcomes. In particular, the availability of medical facilities such as pharmacies, clinical offices, and hospitals may be relevant to both accessing timely care immediately following SCA and preventing SCA.

Among individuals at risk for SCA, the presence of medical facilities near home may over the long-term improve one’s access to preventive care by reducing transportation and time-related barriers that can impede timely acquisition of prescription medications and related management of chronic conditions. Availability of local medical facilities may encourage more frequent healthcare provider visits [11, 12], better compliance with prescribed medication[13], and ultimately, decreased vulnerability to SCA. Among individuals experiencing SCA, proximity to certain medical facilities may be associated with receiving timely emergency care. Only a few studies have examined the presence of type of medical facilities in the residential neighborhood with risk of cardiovascular disease [14–16], and even fewer have examined this association in a US population.

Survival after out-of-hospital SCA is higher among cases who present with ventricular fibrillation (VF)[17]. Medical facilities in the vicinity of a VF-SCA event may also explain between-neighborhood differences in SCA survival. Emergency medical services (EMS) response times, which can differ between neighborhoods, are a key determinant of SCA survival [18–20].

We examined the associations of local availability of types of medical facilities with SCA incidence, response times, and survival. Specifically, we examined a) the association between medical facilities hypothesized to support risk factor management and SCA prevention (i.e. cardiac health-promoting) in the home census tract and SCA incidence, and b) the association between major medical centers near the SCA event location and emergency response time, and survival after arrest among cases presenting with a VF rhythm.

Methods

Study design and population

We used data from the Cardiac Arrest Blood Study-Repository (CABS-R). CABS-R is a population-based registry, beginning in 1988 and ongoing, containing data on EMS incident reports of adult (age 18+) SCA cases attended by paramedics in Seattle and suburban King County (Washington State). Detailed information on CABS-R has been previously published [21, 22]. For this analysis, we used observations from years 1990–2010.

Cases of SCA were defined by the occurrence of a sudden pulseless condition observed without evidence of a non-cardiac cause (e.g. trauma or drug overdose), identified from a review of EMS incident reports or death certificates, medical examiner reports, and autopsy reports [21]. Subjects were classified as having had definite, probable, or possible SCA, and initial rhythm (VF, asystole, pulseless electrical activity, or ventricular tachycardia) and comorbidity status were recorded. Only cases with definite or probable SCA were included in our analyses. Other event information collected included whether the SCA was witnessed (Y/N), whether bystander CPR was provided (Y/N or N/A as arrest occurred after EMS arrival), and response time to first EMS aid from a medic unit [22]. Survival (Y/N) was defined as being alive when discharged from the hospital.

Population-based controls were recruited by random-digit dialing within King County and matched to the subset of CABS-R cases without diagnosed heart disease before their SCA and under age 80. Matching was based on sex, age (±7 years), and calendar year (i.e. year of SCA for cases and year of recruitment for controls) up to 2006, as controls were only recruited through 2006. We note that the ratio of controls to cases is lower than in a traditional case-control study; case-only analyses have been important within CABS-R, allowing investigation of gene-environment interactions and determinants of survival among cases [22–24]. The control response rate was 64% [21].

Informed consent was provided by participants, with a waiver of consent obtained for some of the cases due to the high fatality of SCA. The Human Subjects Review Committee at the University of Washington approved all data collection protocols, and the Human Subjects Review Committees at the University of Washington and Columbia University Medical Center approved the geographic linkage and analyses for this study.

Medical facilities in the neighborhood environment

The home addresses of both cases and controls, and the event addresses of SCA cases were geocoded. Seattle and King County address point data were used as the geocoding reference; addresses not meeting the minimum match score criteria of 100 were interactively matched using ancillary data sources such as Google Maps. Geospatial coordinates were mapped to census tracts, which generally have between 1,200 and 8,000 residents. Geocoding and GIS analysis were performed using ArcGIS v. 10.3.1. Per capita household income from year 2000 US Census was used to represent the social and economic context, or neighborhood SES, of each census tract.

The National Establishment Time-Series (NETS) longitudinal database contains yearly registration data for businesses, including company name, street address, and Standard Industry Classification (SIC) code [25]. SIC codes and business names were used to identify medical facilities and classify them into categories (e.g. pharmacies, health practitioners and major medical centers). Business addresses were geocoded and assigned a Year 2000 census tract using the point-in-polygon method. Total counts for each type of medical establishment were obtained for each King County census tract for each year from 1990 to 2010. Details on the processing and cleaning methods used for this spatial-temporal dataset have been previously published [26].

We considered offices of health practitioners (e.g. family medicine, general practitioners) and pharmacies to be potentially cardiac health-promoting, and used these two measures as our exposure for the relationship of medical facilities near the home with SCA incidence. For the outcomes of EMS response time, and survival after VF-SCA, we considered only major medical centers (e.g. freestanding emergency medical centers and hospitals) which could provide urgent SCA care. Detailed SIC descriptions of the facilities included in each of these categories have been previously published and are included in Appendix A [26].

Statistical Analysis

Our analytic approach and adjustment strategy was tailored to each of the three outcomes: SCA risk, response time, and survival. We adjusted for hypothesized confounders based on previous work from this study and common prior causes thought to bias our associations.

First, we examined the relationship between cardiac-promoting facilities in the residential census tract and risk of SCA using only the matched case-controls discussed above. Because case ascertainment was less complete outside Seattle during the early years of CABS-R, we additionally limited our main analysis to the 446 cases and 208 controls who lived within Seattle city limits. We used multivariable logistic regression with cluster robust standard errors (clustering on census tract) to predict SCA risk. Counts of pharmacies and offices of health practitioners were standardized (such that the standard deviation was 1) to facilitate comparisons, and modeled separately, adjusting for potential confounding variables age, sex, calendar year, and census tract-level per capita household income.

To test the hypothesis that presence of a major medical center (any versus none) in the SCA event tract was associated with faster EMS response times and, in turn, VF-SCA survival, we used the 1537 CABS-R cases who presented with VF (for which the probability of survival was higher), had recorded response time to EMS medic unit arrival, and had geocoded event locations. (Appendix B presents supplemental analyses including all SCA cases showing similar results). We used multivariable linear regressions using cluster robust standard errors to assess the association between having any major medical center facility in the census tract in which the SCA event occurred and EMS response time, adjusting for potential confounders age, sex, calendar year, census tract-level per capita household income, and circumstances of the SCA event – witnessed event and bystander CPR (Y/N). Logistic regression models were used to examine the association between any major medical centers and VF-SCA survival, and to confirm the association of lower EMS response times with greater likelihood of VF-SCA survival. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 14 (STATA Corp., Texas, USA), and model residual plots used to assess the linearity assumption of the continuous variables.

Sensitivity analyses

Because confounding by unmeasured aspects of the residential neighborhood environment might bias our findings, we considered local financial institutions as a negative control [27] in order to distinguish the availability of medical facilities from total commercial density [28]. Similarly, because associations between home census tract and response time independent of SCA location are unexpected unless there was unmeasured confounding by neighborhood selection, we repeated our analysis of survival after SCA using a subsample of participants whose VF-SCA events occurred outside of their home census tract (n=572, 36% of VF-SCA cases). Because of prior indications that SCA risk may be modified by neighborhood SES [23], we explored effect modification by neighborhood SES for the primary analyses by including an interaction term for cardiac-promoting medical facilities exposure and SES.

Results

Association between cardiac health-promoting medical facilities in the residential neighborhood and risk of SCA in Seattle

The demographic characteristics of the Seattle-based cases and controls for the analysis of SCA risk are shown in Table 1. Exposure to more cardiac health-promoting medical facilities such as pharmacies and offices of health practitioners was associated with increased SCA risk (Table 3). The odds of being a case was 1.32 (95% CI: 1.06, 1.64) times for every standard deviation increase (Mean ± SD: 4.8 ± 4.9) in counts of health practitioners in the home census tract. Presence of more financial institutions was also positively associated with SCA risk. While the association between cardiac health-promoting medical facilities and SCA risk appeared larger in the highest quartile of neighborhood SES, the interaction terms in the models assessing effect modification by neighborhood SES were not statistically significant (not shown).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of 654 Seattle sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) cases and controls from 1990–2006.

| Characteristic | SCA Case (n=446) |

Control (n=208) |

|---|---|---|

| Individual | ||

| Age, Mean (SD) | 63 (12) | 57 (11) |

| Female, % (n) | 28 (127) | 19 (39) |

| Race/Ethnicity, % (n) | ||

| White | 77 (342) | 91 (189) |

| Black | 13 (60) | 4 (8) |

| Other | 10 (44) | 5 (11) |

| Census tracts characteristics | ||

| Health practitioners (median, range) | 4 (0, 36) | 3 (0,34) |

| Pharmacies (median, range) | 1 (0, 8) | 0 (0, 9) |

| Per-capita income, $ (median, IQR range) | 28,534 (20230, 35455) | 34,119 (28490, 44948) |

Table 3.

Residential neighborhood potential cardiac health-promoting health facilities and risk of out-of-hospital sudden cardiac arrest (SCA), stratified by neighborhood SES for 208 controls and 446 cases in the city of Seattle 1990–2006. (n=654)

| Odds ratio for SCA risk per standard deviation increase in exposure (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|

| Health practitioners | 1.32 (1.06, 1.64) |

| Lowest income quartile (n=164) | 0.92 (0.48, 1.80) |

| Highest income quartile (n=161) | 1.40 (1.21, 1.63) |

| Pharmacies | 1.28 (1.03, 1.59) |

| Lowest income quartile | 1.04 (0.60, 1.80) |

| Highest income quartile | 1.28 (1.11, 1.48) |

| Major medical centers | 1.29 (1.02, 1.62) |

| Lowest income quartile | 1.03 (0.71, 1.51) |

| Highest income quartile | 1.27 (0.78, 2.05) |

| Financial institutions | 1.22 (1.08, 1.37) |

| Lowest income quartile | 1.18 (0.31, 4.55) |

| Highest income quartile | 1.22 (1.13, 1.32) |

Main analyses control for age, sex, calendar year, per capita household income of the home census tract (neighborhood SES), and use cluster robust standard errors.

Each type of medical facility has been rescaled to a z-score. An OR > 1 represents greater odds of SCA risk for participants living in a neighborhood with more of the specified type of health facility or other establishment.

Bold face is used to indicate statistical significance (p<0.05).

Association between major medical centers at the SCA event census tract and EMS response time and VF-SCA survival

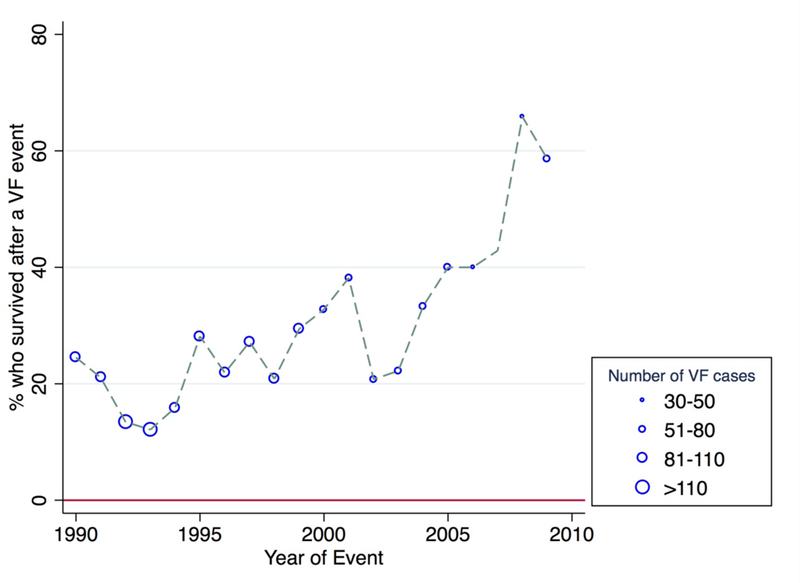

Survival after VF-SCA in King County was high and increased over the course of the study period (Figure 1). Table 2 shows demographic characteristics of the VF-SCA cases. A 31% survival was observed for those whose VF-SCA occurred in a census tract with a major medical center, compared to 26% survival in census tracts without. Appendix C shows the location of census tracts with any major medical center throughout King County in 2000.

Figure 1. Survival after Ventricular Fibrillation (VF) Sudden Cardiac Arrest (SCA) in King County, WA (1990–2010) in the Cardiac Arrest Blood Study-Repository dataset.

Note: The marker size is relative to the number of VF-SCA cases in that year. In 2010, there were only 10 cases of VF (and no deaths) in our study sample and were thus excluded from the figure.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the 1537 out-of-hospital sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) cases presenting with ventricular fibrillation (VF), stratified by survival status and event census tracts with any major medical center versus none, recruited in King County, WA 1990–2010.

| SCA event census tract of VF cases |

Survival after VF-SCA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Any (≥1 facility) (n=325) |

None (n=1212) |

Survived (n=417) |

Died (n=1120) |

| Individual | ||||

| Age, Mean (SD) | 65 (13) | 66 (14) | 62 (14) | 67 (13) |

| Female, % (n) | 19 (61) | 21 (251) | 24 (99) | 19 (213) |

| Race/Ethnicity, % (n) | ||||

| White | 81 (263) | 86 (1037) | 83 (348) | 85 (952) |

| Black | 11 (37) | 9 (105) | 10 (40) | 9 (102) |

| Other | 8 (25) | 6 (70) | 7 (29) | 6 (66) |

| Cardiac arrest witnessed, % (n) | 72 (235) | 74 (892) | 89 (372) | 67 (755) |

| Bystander CPR received, % (n) | 60 (194) | 58 (701) | 66 (274) | 55 (621) |

| Median EMS time for a medic unit, mins (median, IQR range) |

7.8 (5.2, 10.2) | 8.4 (6.3, 11.2) | 8.0 (6.2, 10.2) | 8.7 (6.2, 11.2) |

| Survival, % | 31 (100) | 26 (317) | - | - |

| Census tracts characteristics | ||||

| Per-capita income, $ (median, IQR range) |

27,903 (20661, 33702) |

29,026 (22783, 36859) |

27,986 (21554, 34139) |

29,163 (22706, 36859) |

| Major medical centers (median, range) | 1 (1, 5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0, 4) | 0 (0, 5) |

SCA event census tracts with any major medical center facility present had a shorter EMS response time than census tracts with none, with a difference of −53 seconds (95% CI: −84, −22) (Table 4). When using presence of any financial institution as a negative control, a difference of −29 seconds (95% CI: −62, 2) was observed. Using the subsample of VF-SCA cases whose event occurred outside the home census tract, similar patterns were observed in the census tract where SCA occurred, but no association was observed for the home census tract.

Table 4.

Associations between presence of any major medical centers in the home and out-of-hospital sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) event environment with EMS response time (seconds) for SCA cases presenting with ventricular fibrillation (VF) cases.

| % of participants in a census tract with Any (≥1 facility) major medical centers |

Change in mean response time, seconds (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Overall VF-SCA cases (n=1537) | ||

| Any major medical centers in event census tract | 21% | − 53 (− 84, − 22) |

|

Subsample of VF-SCA cases (n=572)

(event census tract ≠ home census tract) |

||

| Any major medical centers in home census tract | 15% | − 4 (− 68, 59) |

| Any major medical centers in event census tract | 34% | − 70 (− 118, − 22) |

All analyses control for age, sex, calendar year, per capita household income of the home census tract, witnessed event and bystander CPR, and use cluster robust standard errors.

Subsample of VF cases who had had the SCA outside their home census tract, and with non-missing, non-zero distance between home and SCA event location.

Bold face is used to indicate statistical significance (p<0.05).

Presence of any major medical centers in the event tract was not significantly associated with VF-SCA survival, controlling for sociodemographic and event characteristics (Table 5).

Table 5.

Associations between the presence of any major medical centers in the home and out-of-hospital sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) event environment and survival after cardiac arrest, for SCA cases presenting with ventricular fibrillation (VF).

| % of participants in a census tract with Any (≥1 facility) major medical centers |

Odds ratios for survival (Ref=None) (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Overall VF-SCA cases (n=1537) | ||

| Any major medical centers in event census tract | 21% | 1.18 (0.91, 1.53) |

|

Subsample of VF-SCA cases (n=572)

(event census tract ≠ home census tract) |

||

| Any major medical centers in home census tract | 15% | 0.68 (0.41,1.11) |

| Any major medical centers in event census tract | 34% | 1.10 (0.77, 1.58) |

All analyses control for age, sex, calendar year, per capita household income of the home census tract, witnessed event and bystander CPR, and use cluster robust standard errors.

Subsample of VF cases who had had the SCA outside their home census tract, and with non-missing, non-zero distance between home and SCA event location.

Association between EMS response times and VF-SCA survival

Higher EMS response times were significantly associated with lower VF-SCA survival; every minute increase in EMS response time was associated with 7% lower odds (95 % CI: 0.90, 0.97) of surviving a VF-SCA event, controlling for age, gender, calendar year, tract-level per capita income, witnessed event and bystander CPR.

Discussion

In this study based in King County, Washington, we found associations between presence of major medical centers in the SCA event neighborhood and decreased EMS response time. As expected, decreased EMS response time was associated with higher odds of survival after a VF-SCA. We found no evidence that medical facilities such as pharmacies and offices of health practitioners in the home neighborhood were associated with a lower risk of SCA.

Nationwide Swedish longitudinal studies have observed similar small positive associations of increased neighborhood availability of healthcare facilities with increased risk of first hospitalization for coronary health disease (including cases of cardiac arrest) while controlling for neighborhood deprivation [14–16]. Upon further control for individual-level income, mainly null effect estimates were observed and the authors concluded that it is unlikely that neighborhood healthcare facilities have a large independent influence on cardiovascular risk [14]. A recent study looking at the distance to pharmacies and medication adherence in the greater Chicago area did not find an association between shorter distances and improved adherence [29]. Taken together, these previous studies and our findings are consistent with the possibility that, at least for our populations, neighborhood availability of medical facilities may not promote health as hypothesized. Other factors beyond geographical proximity to medical facilities, such as costs, insurance coverage, and transportation influence access to healthcare, and support risk factor management and SCA prevention.

Another explanation for our findings could be the collinearity between types of commercial businesses (e.g. medical businesses, fast food restaurants, financial institutions), reflects a harmful effect of commercial density on SCA incidence, rather than the specific effect of presence of medical facilities. Previous studies have reported that city-areas with increased population movement have higher incidence of SCA [30], and similar mechanisms could be driving our results. Reverse causation could also be at play, wherein medical businesses choose to locate in neighborhoods with high-need populations, or older adults at higher SCA risk move to homes located nearer to medical businesses. Nevertheless, our exploration of the association between specific types of potentially cardiac health-promoting medical facilities in the home neighborhood with SCA incidence is a novel contribution to the literature.

A recent study found that overall residential neighborhood density of family physicians was not associated with SCA survival [31]. We found similar overall null associations between residential cardiac health-promoting medical facilities and VF-SCA survival in our study (Appendix D). The previous study authors suggested exploring the association of more specialized care with SCA outcomes, but our findings do not support the hypothesis that being in a census tract with any major medical center is associated with better survival, especially in a non-rural area like King County. Nevertheless, this could have been the result of studying a more distal relationship requiring a larger sample size, as examinations of the more proximal relationship using EMS response time detected a positive relationship between major medical centers and improved response times.

Our finding that the presence of any major medical center was associated with decreased EMS response times is consistent with the literature examining the importance of event location on EMS response times [32]. As EMS response time is a significant predictor of survival to hospital discharge [33], our results provide some support for the effect of location of major medical center facilities on survival. This could have important implications for residential planning. For example, such knowledge may influence the placement of retirement communities or other amenities for older adults at highest risk of SCA. However, financial institutions were also associated with decreased EMS response time, and we cannot distinguish the effect of more medical facilities from greater commercial density.

Our study has several strengths. The study population was well-characterized and controls were population-based, and our use of both event and home tract data allows more precise tests of our hypotheses. Importantly, the detailed NETS database allowed great specificity to categorize medical establishments by type, and the medical facility measure was specific to the calendar year of SCA occurrence, rather than observed at a singular time point as in previous studies.

There are a few limitations. We use a mix of neighborhood-level (per capita income, medical facilities) and individual-level data (case control or survival status, EMS response time and age) for this study. The spatial exposure variables of medical facilities were census tract aggregates and may be less sensitive than point-buffer-based measures, and misclassification of exposure may occur due to a facility being on the edge of the census tract [34–36]. We only had Year 2000 US Census measures of census tract per capita household income and could not control for individual SES. Thus, unmeasured or residual confounding is of concern in this study.

We lacked more proximal measures (e.g. utilization of health care within the neighborhood or chronic medication prescription adherence) on the hypothesized pathway from neighborhood cardiac health-promoting medical facilities to SCA incidence, and our study was limited by the lack of residential history data, and the duration of the exposure was uncertain. More precise geolocation accounting for road distances or travel time between the major medical centers and location of SCA events could also improve our understanding of the effect of the location of major medical centers on EMS response times. The criteria used to identify offices of health practitioners were broad and included some facilities (e.g. chiropractor office) that may not be directly cardiac health-promoting, and multicollinearity complicates our efforts to investigate particular types of medical facilities in the census tract. As in other neighborhood effect studies, we are unable to account for health-relevant factors influencing residential neighborhood selection [37]. Also, importantly for our case-control analyses the response rate for our controls was 64%, and a non-random refusal pattern (e.g., systematically higher response rate among Seattle residents living close to medical facilities) could bias results. Lastly, King County has the best EMS response system in the country [38], and it is unclear how generalizable our results are to other settings, though King County’s high SCA survival rate increased our power to detect factors influencing survival after SCA.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we did not observe an association between potentially cardiac health-promoting medical facilities such as pharmacies and offices of health practitioners in the home neighborhood and lower risk of SCA or survival after SCA. Although the presence of major medical centers in the SCA event neighborhood was associated with decreased EMS response time, it was not associated with survival.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Erin Wallace who conducted the data collection necessary for geocoding of the CABS data.

The Sudden Cardiac Arrest Blood Repository Study was financed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grants RO1- HL091244, HL092111, HL088456, HL128709, HL116747, HL111089, HL088576). Funding for this work was also provided by the Medic One and Locke Foundations and the Laughlin Family, and funded in part by grants K01HD067390 and T32HD057822 from the Eunice Kennedy Shiver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development, a grant from the UW Nutrition and Obesity Research Center (P30 DK035816), and by a Calderone Research Award from the Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University.

The funding sources had no involvement in the writing and interpretation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- [1].Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics−-2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Becker LB, Han BH, Meyer PM, Wright FA, Rhodes KV, Smith DW, et al. Racial differences in the incidence of cardiac arrest and subsequent survival. The CPR Chicago Project. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:600–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Galea S, Blaney S, Nandi A, Silverman R, Vlahov D, Foltin G, et al. Explaining racial disparities in incidence of and survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. American journal of epidemiology. 2007;166:534–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kong MH, Peterson ED, Fonarow GC, Sanders GD, Yancy CW, Russo AM, et al. Addressing disparities in sudden cardiac arrest care and the underutilization of effective therapies. Am Heart J. 2010;160:605–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fosbøl EL, Dupre ME, Strauss B, Swanson DR, Myers B, McNally BF, et al. Association of neighborhood characteristics with incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and rates of bystander-initiated CPR: implications for community-based education intervention. Resuscitation. 2014;85:1512–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Feero S, Hedges JR, Stevens P. Demographics of cardiac arrest: association with residence in a low-income area. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:11–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Reinier K, Stecker EC, Vickers C, Gunson K, Jui J, Chugh SS. Incidence of sudden cardiac arrest is higher in areas of low socioeconomic status: a prospective two year study in a large United States community. Resuscitation. 2006;70:186–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ahn KO, Do Shin S, Hwang SS, Oh J, Kawachi I, Kim YT, et al. Association between deprivation status at community level and outcomes from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a nationwide observational study. Resuscitation. 2011;82:270–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sasson C, Keirns CC, Smith DM, Sayre MR, Macy ML, Meurer WJ, et al. Examining the contextual effects of neighborhood on out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and the provision of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2011;82:674–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sasson C, Magid DJ, Chan P, Root ED, McNally BF, Kellermann AL, et al. Association of neighborhood characteristics with bystander-initiated CPR. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367:1607–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hiscock R, Pearce J, Blakely T, Witten K. Is neighborhood access to health care provision associated with individual-level utilization and satisfaction? Health services research. 2008;43:2183–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Harrington DW, Wilson K, Bell S, Muhajarine N, Ruthart J. Realizing neighbourhood potential? The role of the availability of health care services on contact with a primary care physician. Health & place. 2012;18:814–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Syed ST, Gerber BS, Sharp LK. Traveling towards disease: transportation barriers to health care access. J Community Health. 2013;38:976–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Calling S, Li X, Kawakami N, Hamano T, Sundquist K. Impact of neighborhood resources on cardiovascular disease: a nationwide six-year follow-up. BMC public health. 2016;16:634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kawakami N, Li X, Sundquist K. Health-promoting and health-damaging neighbourhood resources and coronary heart disease: a follow-up study of 2 165 000 people. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2011;65:866–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hamano T, Kawakami N, Li X, Sundquist K. Neighbourhood environment and stroke: a follow-up study in Sweden. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Daya MR, Schmicker RH, Zive DM, Rea TD, Nichol G, Buick JE, et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival improving over time: Results from the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium (ROC). Resuscitation. 2015;91:108–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Abrams HC, McNally B, Ong M, Moyer PH, Dyer KS. A composite model of survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest using the Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES). Resuscitation. 2013;84:1093–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sladjana A, Gordana P, Ana S. Emergency response time after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. European journal of internal medicine. 2011;22:386–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Govindarajan A, Schull M. Effect of socioeconomic status on out-of-hospital transport delays of patients with chest pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:481–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Siscovick DS, Raghunathan TE, King I, Weinmann S, Wicklund KG, Albright J, et al. Dietary intake and cell membrane levels of long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and the risk of primary cardiac arrest. JAMA. 1995;274:1363–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Johnson CO, Lemaitre RN, Fahrenbruch CE, Hesselson S, Sotoodehnia N, McKnight B, et al. Common variation in fatty acid genes and resuscitation from sudden cardiac arrest. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2012;5:422–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mooney SJ, Grady ST, Sotoodehnia N, Lemaitre RN, Wallace ER, Mohanty AF, et al. In the Wrong Place with the Wrong SNP: The Association Between Stressful Neighborhoods and Cardiac Arrest Within Beta-2-adrenergic Receptor Variants. Epidemiology. 2016;27:656–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ghobrial J, Heckbert SR, Bartz TM, Lovasi G, Wallace E, Lemaitre RN, et al. Ethnic differences in sudden cardiac arrest resuscitation. Heart. 2016;102:1363–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Walls D National establishment time-series (NETS) database: 2008 database description. Oakland, CA 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kaufman TK, Sheehan DM, Rundle A, Neckerman KM, Bader MD, Jack D, et al. Measuring health-relevant businesses over 21 years: refining the National Establishment Time-Series (NETS), a dynamic longitudinal data set. BMC research notes. 2015;8:507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lipsitch M, Tchetgen Tchetgen E, Cohen T. Negative controls: a tool for detecting confounding and bias in observational studies. Epidemiology. 2010;21:383–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bader MD, Schwartz-Soicher O, Jack D, Weiss CC, Richards CA, Quinn JW, et al. More neighborhood retail associated with lower obesity among New York City public high school students. Health & place. 2013;23:104–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Syed ST, Sharp LK, Kim Y, Jentleson A, Lora CM, Touchette DR, et al. Relationship Between Medication Adherence and Distance to Dispensing Pharmacies and Prescribers Among an Urban Medicaid Population with Diabetes Mellitus. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36:590–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Marijon E, Bougouin W, Tafflet M, Karam N, Jost D, Lamhaut L, et al. Population movement and sudden cardiac arrest location. Circulation. 2015;131:1546–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Buick JE, Ray JG, Kiss A, Morrison LJ. The association between neighborhood effects and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes. Resuscitation. 2016;103:14–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lam SS, Nguyen FN, Ng YY, Lee VP, Wong TH, Fook-Chong SM, et al. Factors affecting the ambulance response times of trauma incidents in Singapore. Accid Anal Prev. 2015;82:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Pell JP, Sirel JM, Marsden AK, Ford I, Cobbe SM. Effect of reducing ambulance response times on deaths from out of hospital cardiac arrest: cohort study. Bmj. 2001;322:1385–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lovasi GS, Grady S, Rundle A. Steps Forward: Review and Recommendations for Research on Walkability, Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Health. Public Health Rev. 2012;33:484–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Duncan DT, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Aldstadt J, Melly SJ, Williams DR. Examination of how neighborhood definition influences measurements of youths’ access to tobacco retailers: a methodological note on spatial misclassification. American journal of epidemiology. 2014;179:373–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wong D The modifiable areal unit problem (MAUP) In: Fotheringham A, Rogerson PA, editors. The SAGE Handbook of Spatial Analysis. London, United Kingdom: SAGE Publications; 2009. p. 104–24. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Oakes JM. The (mis)estimation of neighborhood effects: causal inference for a practicable social epidemiology. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:1929–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Public Health- Seattle and King County. Emergency Medical Services Division 2014 Annual Report 2014. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.