Abstract

Background

Zinc plays a vital antioxidant role in human metabolism. Recent studies have demonstrated a correlation between noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) and oxidative injury; however, no investigation has focused specifically on the subgroup of NIHL associated tinnitus patients. We aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of zinc supplementation in treating NIHL associated tinnitus.

Methods

Twenty patients with tinnitus and a typical NIHL audiogram (38 ears) were included in this study. Another 20 healthy subjects were used as the control group. A full medical history assessment was performed, and each subject underwent an otoscopic examination, basic audiologic evaluation, distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs), tinnitus-match testing, Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) and serum zinc level analyses. After 2 months of treatment with zinc, all tests were repeated.

Results

There was a significant difference between pretreatment and post-treatment within the tinnitus group (73.6 vs. 84.6 μg/dl). The pre- and post-treatment difference in serum zinc was significantly higher in the young group (≦50 years) compared to the old group (19.4 ± 11.4 vs. 2.6 ± 9.2 μg/dl, respectively; p = 0.002). There were no statistically significant differences in hearing thresholds, speech reception thresholds, or tinnitus frequency and loudness results before and after treatment. In addition, 17 patients (85%) showed statistically significant improvement of THI-total scores post-treatment, from 38.3 to 30 (p = 0.024).

Conclusions

Zinc oral supplementation elevated serum zinc levels, especially in younger patients. THI scores improved significantly following zinc treatment in patients with NIHL associated tinnitus. However, no improvements in objective hearing parameters were observed.

Keywords: Noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL), Tinnitus, Zinc

At a glance of commentary

Scientific background on the subject

Noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) causes permanent hearing loss and tinnitus. The pathogenesis of NIHL is closely related to reduce blood flow and increase free radical production. High concentrations of zinc protect the cochlea from acute injury due to reactive oxygen species.

What this study adds to the field

This is the first study to evaluate the effectiveness of zinc supplementation on tinnitus-associated NIHL. Our findings demonstrated that Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) scores improved significantly following zinc supplementation in patients with tinnitus-associated NIHL. However, no improvements in objective hearing parameters were observed.

Prolonged intense noise exposure leads to the degeneration of hair cells in Corti's organ located in the cochlea; this kind of sensorineural hearing impairment is called noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) [1]. NIHL causes permanent hearing loss, although it is completely preventable through the proper use of hearing protection. Typical audiograms of NIHL patients reveal early high pitch level deficit (3–6 kHz), especially 4 kHz, which is also referred to as 4k notch or C5-dip. Such audiogram findings help to differentiate NIHL from presbycusis [2].

Tinnitus is a manifestation of the spontaneous depolarization of auditory fibers, which creates noise without an external acoustic stimulus [3]. The pathophysiology of subjective tinnitus remains poorly understood, but it involves cochlear hair cells, neural and central auditory pathways. Disturbances in the central auditory pathways may develop after cochlear injury or hearing loss resulting in an auditory equivalent of phantom limb pain [4]. A previous study showed that tinnitus is one the most common hearing disturbances, affecting 17% of the general population, and 33% of the elderly [5]. Among NIHL patients, subjective tinnitus accounts for 35–77% [6], [7].

Zinc is abundant in the cochlea, especially the stria vascularis, in the form of copper/zinc superoxide dismutase (Cu/Zn SOD; SOD1). Decreased plasma zinc and copper levels lead to impaired Cu/Zn SOD activity and stability [8], [9]. High concentrations of zinc increase Cu/Zn SOD activity and protect the cochlea from acute injury due to reactive oxygen species (ROS) [10]. Recent studies have demonstrated that the pathogenesis of NIHL is closely related to ischemia-reperfusion injury of the cochlea, which is caused by reduced blood flow and increased free radical production due to excessive noise. This suggests that protecting the cochlea from oxidative stress is an effective therapeutic approach for NIHL [11].

The effect of zinc in patients with tinnitus is controversial among several reports [12], [13], [14], [15]. In recent studies, zinc was not effective in treating adults with tinnitus [16]; however, other authors identified patients with different etiology who may benefit from zinc supplementation [17]. Different access to tinnitus patients could be required according to audiometric shape [18]. Thus, the aim of the current study was to investigate the effectiveness of zinc supplementation in a subset of patients with NIHL associated tinnitus.

Materials and methods

Subjects and study design

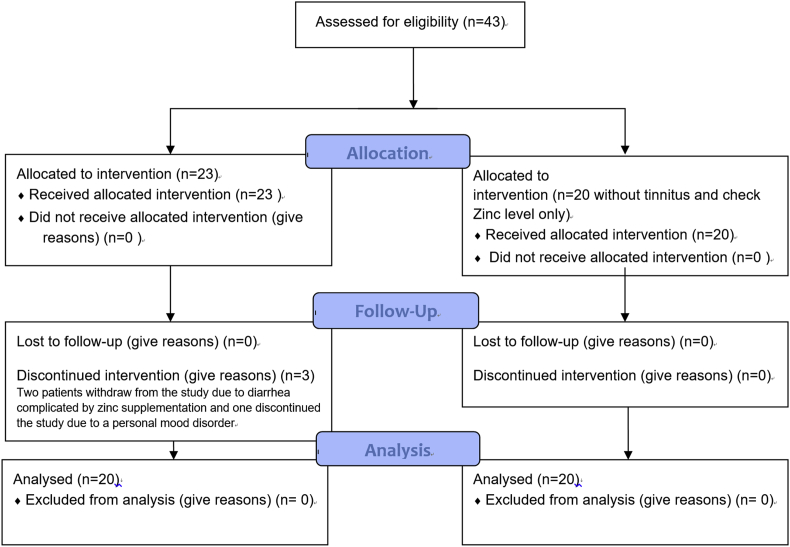

This study enrolled patients who visited our ENT out-patient department with the primary complaint of tinnitus more than 6 months. A full medical history assessment was performed, and each patient underwent an otoscopic examination, a basic audiologic evaluation. Health subjects without tinnitus, hearing impairment and other otologic diseases served as the internal control group. The trial protocol (single blind design) are listed in Fig. 1. We selected the patients whose audiogram data met the inclusion criteria for NIHL: 1) bilateral typical NIHL audiogram and type A tympanogram; 2) hearing threshold above 4k Hz was greater than 25 dB HL; 3) audiogram showed the characteristic 4 kHz or 6 kHz notch (average hearing threshold was 10 dB HL higher than the baseline); 4) up-turn phenomenon appeared above 6 kHz or 8 kHz, and 5) symmetrical hearing loss threshold over bilateral ears and the disparity was less than 10 dB HL. Patients with other otologic diseases were excluded.

Fig. 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram of the trial protocol.

A full medical history assessment was performed, and each patient completed the NIHL questionnaire (Supplementary S1), audiogram, tympanogram, speech discrimination test, distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAE) testing, pitch and loudness match of the tinnitus, Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) and serum zinc level analyses. All tests were repeated after 2 months of treatment with zinc gluconate (Zinga 78 mg, 10 mg elemental zinc), two tablets twice per day (40 mg per day). Zinc levels were measured in undiluted serum by flame atomic absorption spectro-photometry (PerkinElmer 5100 PC, Shelton, CT). The authors assert that all methods were carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Medical Foundation (No: 1023893A3). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Objective measurements

Pure tone audiometry (PTA) or speech discrimination tests were conducted in a sound-treated booth (background noise level less than 30 dB A) equipped with a two-channel clinical audiometer (GSI 61; Grason-Stadler Inc., Eden Prairie, MN). Hearing thresholds of 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 kHz were measured.

The measurement of DPOAE used two pure-tone stimuli at frequencies of 65 dB SPL (f1) and 55 dB SPL (f2) with an f2/f1 (frequency) ratio of 1.22. The geometric mean frequencies (GM Hz) ranged from 5 to 10 kHz. The most robust DPOAE occurs at the frequency determined by the equation 2f1-f2 (recorded as DP Hz), whereas the actual cochlear frequency region assessed with DPOAE is between these two frequencies, probably close to the f2 stimulus. The stimulus intensity was defined as positive when all frequencies of 2f1-f2 tested 6 dB SPL greater than the noise floors (NF) [19].

Using a GSI 61 clinical audiometer, patients were asked to compare the pitch and loudness of their tinnitus with a pure tone or sinusoidal tone noise. In unilateral tinnitus patients, we chose the contralateral ear as the testing ear. If the patient had bilateral tinnitus, the right ear was chosen as the testing ear. Uneven subjective with bilateral tinnitus was tested on both ears. In the sound-proof booth, we gave intermittent stimuli noise through TDH 50p earphones at 15 dB above the highest measured audiometric threshold (0.25k, 0.5k, 1k, 2k, 3k, 4k, 6k, and 8 kHz), and the subject reported the audiometric frequency that represented the closest match to the pitch of their tinnitus [20].

Subjective measurements

When the matching procedure was first used, the level was initially set at 5 dB above the highest measured audiometric threshold (at any frequency), and the patient reported the audiometric frequency that gave the closest match to the pitch of their tinnitus, repeated three times. Then the level was adjusted in 2-dB steps until the patient indicated that the tone matched the loudness of their tinnitus, repeated three times.

We used the Mandarin-Chinese version of THI questionnaire to evaluate subjective tinnitus [21]. The severity of subjective tinnitus was divided into five subgroups including very mild (0–16 points), mild (18–36 points), moderate (38–56 points), severe (58–76 points), and very severe (78–100 points).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis included the paired t-test, Pearson's correlation coefficient, and simple linear regression analysis using SPSS 20.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Sex, age, hearing threshold and tinnitus matching were analyzed by applying descriptive statistics.

Results

The study enrolled 23 patients with long-standing tinnitus and a typical NIHL audiogram. Another 20 patients without tinnitus made up the control group. Two patients withdrew from the study due to diarrhea complicated by zinc supplementation and one discontinued the study due to a personal mood disorder, so the final study group consisted of 20 patients with a mean age 48.5 ± 11.3 years (range, 31–67 years). The patients’ demographic data and trial protocol are listed in Fig. 1 and Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients' demographic data.

| Study group | Healthy group | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients (numbers) | 20 | 20 |

| Age (years ± SD) | ||

| Mean ± SD (years) | 48.5 ± 11.3 | 46.9 ± 15.3 |

| Range (years) | 31–66 | 31–59 |

| Male: Female | 17:3 | 16:4 |

| Duration of the tinnitus | ||

| Mean ± SD (years) | 5.1 ± 6.3 | |

| Range (years) | 0.5–23 | |

| Tinnitus location | ||

| Bilateral | 18 (90) | |

| Unilateral | 2 (10) | |

| Tinnitus character | ||

| Persistent | 19 (95) | |

| Intermittent | 1 (5) | |

| Tinnitus subjective quality | ||

| High pitch/hissing | 7 (35) | |

| High pitch/Gee–Gee sound | 7 (35) | |

| High-pitch/hissing + Gee–Gee sound | 1 (5) | |

| High-pitch/hissing + Chi–Chi sound | 1 (5) | |

| High pitch/ringing | 1 (5) | |

| Low pitch/roaring | 3 (15) | |

The subjective description terms of tinnitus included six types of sounds and are listed in Table 1. The most common tinnitus-related NIHL were high pitch (17/20, 85%) and persistent (19/20, 95%). Eighteen patients were exposed to high noise work environments; however, only three (16.7%) of them wore hearing protection to reduce the amount of noise. The subjects were continuously exposed to loud noise during the study period. The other 2 patients were exposure to intermittent recreational noise (e.g., personal listening devices).

Twenty health subjects without tinnitus, hearing impairment and other otologic diseases served as the internal control group. They did not take zinc supplement. There were 16 males and 4 females, and the mean age was 46.5 ± 9.0 years (range, 31–59 years). There was no significant difference in age or sex between study and control groups. The pre-treatment serum zinc level did not differ significantly between the two groups (73.6 ± 11.6 μg/dl vs. 76.5 ± 15.3 μg/dl), but the post-treatment serum zinc level of the study group (84.6 ± 12.5 μg/dl) was significantly different compared to the pre-treatment study group (73.6 vs. 84.6 μg/dl, p = 0.001; Table 2). Zinc supplementation for 2 months elevated serum zinc levels.

Table 2.

Correlation between pre- and post-treatment clinical parameters in tinnitus patients related to noise-induced hearing loss.

| Pre-treatment (mean ± SD) | Post-treatment (mean ± SD) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum zinc level (μg/dl) | 73.6 ± 11.6 | 84.6 ± 12.5 | 0.001 |

| Hearing threshold (dB HL) | |||

| 0.5k + 1k + 2k + 4k/4 | 21.8 ± 8.9 | 22.1 ± 8.8 | 0.675 |

| 6k + 8k/2 | 41.5 ± 18.9 | 42.9 ± 18.1 | 0.091 |

| Speech test | |||

| SRT (dB HL) | 15.9 ± 5.7 | 16.3 ± 8.5 | 0.727 |

| WDS (%) | 99.4 ± 1.9 | 98.9 ± 2.5 | 0.086 |

| Tinnitus frequency (Hz) | 5973.7 ± 1965.8 | 6052.6 ± 2026. | 0.822 |

| Tinnitus loudness (dB HL) | 47.0 ± 18.3 | 46.7 ± 17.8 | 0.886 |

| THI-total scores | 38.3 ± 18.9 | 30.0 ± 18.6 | 0.024 |

| THI-emotional scores | 13.4 ± 9.1 | 9.7 ± 7.9 | 0.032 |

| THI-functional scores | 12.8 ± 9.3 | 10.2 ± 8.6 | 0.124 |

| THI-catastrophic scores | 12.1 ± 3.0 | 10.1 ± 3.9 | 0.010 |

| DPOAEa (Hz) | |||

| 562 (positive rate, %) | 33/38 = 86.8% | 28/38 = 73.7% | 0.150 |

| 796 | 34/38 = 89.5% | 33/38 = 86.8% | 1.000 |

| 1125 | 34/38 = 89.53% | 34/38 = 89.5% | 1.000 |

| 1595 | 30/38 = 78.9% | 25/38 = 65.8% | 0.200 |

| 2249 | 13/38 = 34.2% | 13/38 = 34.2% | 1.000 |

| 3187 | 9/38 = 23.7% | 7/38 = 18.4% | 1.000 |

| 4501 | 12/38 = 31.6% | 13/38 = 34.2% | 1.000 |

| 6375 | 15/38 = 39.5% | 10/38 = 26.3% | 0.768 |

frequency of 2f1-f2.

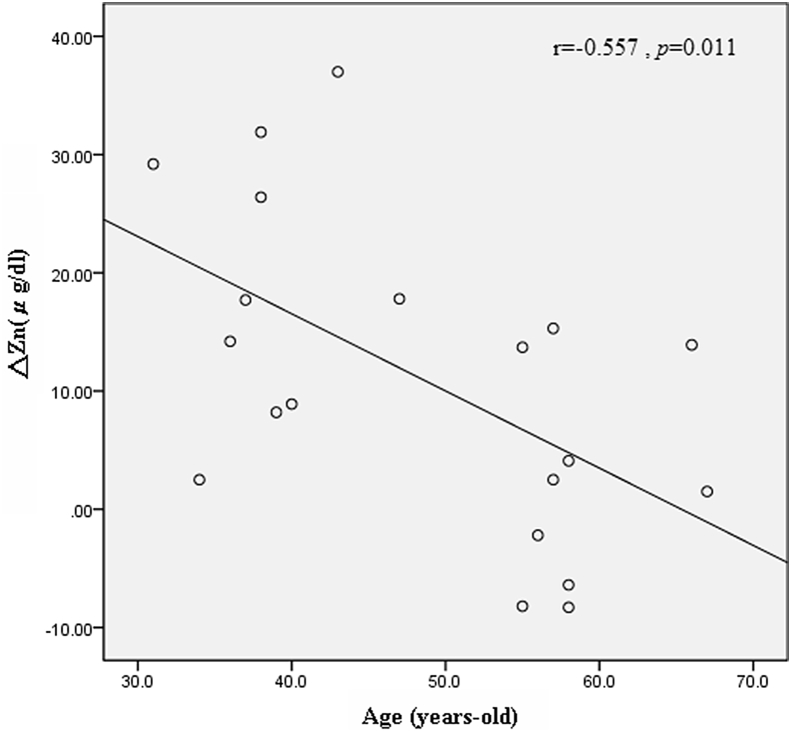

When we analyzed age versus the pre- and post-treatment difference in serum zinc (△Zn), the △Zn decreased with increased age (r = −0.557; p = 0.011; Fig. 2). When the subjects were sub-grouped into young (≦50 years) and old (>50 years), the △Zn was significantly higher in the young group compared to the old group (19.4 ± 11.4 vs. 2.6 ± 9.2 μg/dl, respectively; p = 0.002).

Fig. 2.

Linear regression analysis of age and △Zn (pre- and post-treatment difference in serum zinc levels). △Zn is decreased with age (r = −0.557; p = 0.011).

The pre- and post-treatment average hearing thresholds using 0.5k + 1k + 2k + 4k/4 and 6k + 8k/2 are listed in Table 2. No significant difference was observed. The pre- and post-treatment speech reception threshold (SRT) and word discrimination scoring (WDS) results are listed in Table 2. Neither parameter showed significant difference.

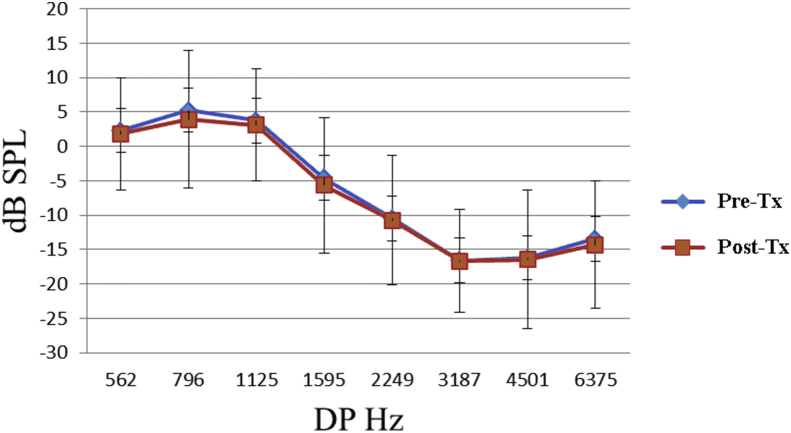

The OAE stimulus intensities were defined as positive when the frequencies of 2f1-f2 tested 6 dB SPL greater than the noise floors (NF) [19]. The findings presented in Table 2 and Fig. 3 suggested that there was no significant difference between the pre- and post-treatment positive rate of DPOAE or the average intensities (dB SPL) over each 2f1-f2 measurement. In the tinnitus pitch and loudness-matching tests, the pre-treatment average frequency and loudness showed no statistical difference compared to post-treatment [Table 2].

Fig. 3.

Pre- and post-treatment average intensities (dB SPL) of distortion produced otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs).

Nineteen cases (95%) showed good correlation between the subjective tinnitus frequency and the pitch-matching test. When a patient's subjective tinnitus was high frequency, the pitch-matching test revealed a similar result, except for one patient; patient T4 complained of high pitch/hissing tinnitus but the objective tinnitus measurement was low pitch (2 and 3 kHz). In addition, patient T13's subjective tinnitus in the tinnitus pitch-matching test was low pitch (3k Hz) before treatment but changed to high pitch (8k Hz) after treatment. In the tinnitus pitch and loudness-matching tests, the pre-treatment average frequency and loudness (5973.7 ± 1965.8 Hz and 46.5 ± 18.1 dB HL) showed no statistical difference compared to post-treatment (6052.6 ± 2026.2 Hz and 46.7 ± 17.8 dB HL).

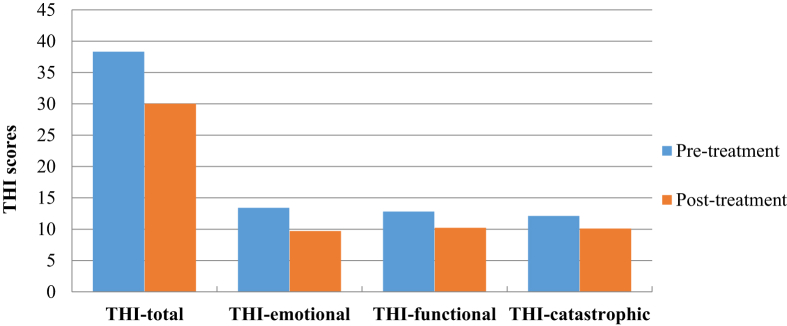

Table 3 shows the pre- and post-treatment THI score distribution of 20 patients in the study. We noted that 17 patients (85%) showed a decrease in THI-total scores following zinc treatment. We analyzed the pre- and post-treatment THI scores and those of each subgroup (emotional, functional and catastrophic; Table 2). A significant decrease was observed following treatment for THI-total (p = 0.024), THI-emotional (p = 0.032) and THI-catastrophic (p = 0.01), but not for THI-functional scores (p = 0.124) [Fig. 4].

Table 3.

Pre- and post-treatment Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) score distribution.

| Severity | THI-scores | Pre-treatment |

Post-treatment |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient numbers | % | Patient numbers | % | ||

| Very mild | 0–16 | 3 | 15% | 5 | 15% |

| Mild | 18–36 | 9 | 45% | 10 | 50% |

| Moderate | 38–56 | 4 | 20% | 3 | 15% |

| Severe | 58–76 | 3 | 15% | 2 | 10% |

| Very severe | 78–100 | 1 | 5% | 0 | 0% |

Fig. 4.

Pre- and post-treatment THI score distribution of 20 patients in the study. THI-total (p = 0.024), THI-emotional (p = 0.032) and THI-catastrophic (p = 0.01) improved significantly except for THI-functional scores (p = 0.124).

Discussion

Tinnitus is one of the most common and annoying otologic complaints, leading to various somatic and psychological disorders, and interfering with the quality of life. Several studies have reported various rates (2–68.7%) of hypozincemia among tinnitus patients [5], [14], [22], [23], [24]. The effectiveness of zinc supplementation ranged from 52 to 82% [5], [22], [23], [24], except for one study in which no significant difference was observed [14]. In a recent study, zinc was not effective in treating subjects over the age of 60 years with tinnitus [17]. The authors identified a subject with a PTA average threshold higher than 40 dB who may benefit from zinc supplement. Zinc supplementation in another study had favorable effects in patients with severe head injury [25]. Thus, it is worth investigating whether a subset of tinnitus-associated NIHL subjects are more likely to respond to zinc treatment. To our knowledge, the current study is the first to evaluate the effectiveness of zinc supplementation on NIHL associated tinnitus.

Zinc is especially abundant in the stria vascularis and present in the synapses of the auditory nerve system. The zinc concentration in the inner ear might affect the function of the auditory nerve system [26]. Hypozincemia could lead to some functional abnormality and is responsible for sensorineural hearing loss, imbalance, and tinnitus [12], [13]. Our study revealed that the pre-treatment serum zinc concentration (73.6 μg/dl) was elevated significantly to 84.6 μg/dl after treatment (p = 0.001). The result is consistent with previous studies that zinc supplementation for 2 months elevated serum zinc levels [5], [25], [27].

Our results also showed that when older patients receive zinc supplementation, due to decreased bioavailability and absorption ratio, their serum zinc levels did not reach the same level as younger patients. This is consistent with previous reports [17], [28], [29]. However, Yetiser et al. found that older patients showed better tinnitus improvement after zinc supplementation when compared to younger patients (82% vs. 48%, respectively) [22]. Age is considered to be a confounding factor when it comes to measuring the effect of zinc supplementation. We might change the daily zinc dosage for older patients in order to achieve the same treatment effectiveness as that observed in younger patients.

Some studies have reported various rates of tinnitus among NIHL patients, from 35 to 77% [6], [7]. Our study group consisted of mainly male patients (17/20, 85%), and we found that males may experience greater noise exposure in their work environments. These results are similar to those reported by Martines et al., in 2010 [30]. Chronic noise exposure is one of the main causes of tinnitus and sensorineural hearing loss [31]. In our study, the most common tinnitus-related NIHL was high-pitched (85%) and persistent (95%). These results are similar to a previous report that most patients (72.1%) with SNHL had a high-pitched tinnitus, and high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss (88.37%) also had high-pitched tinnitus [30]. Prolonged noise exposure in the work environment can induce irreversible NIHL. However, in our study, three patients were not exposed to prolonged high noise on the job. They exposed to other types of noise outside of the workplace including recreational exposures (e.g., personal listening devices) and high ambient noise environmental exposures (e.g., airports). Thus, NIHL can occur as a result of various types of noise exposures outside of the workplace.

The outer hair cells of the cochlea play an important role in tinnitus [32]. Otoacoustic emissions correspond closely to the physiological state of outer hair cells of the cochlea and allow for a noninvasive, rapid, and cost-effective measure of presynaptic auditory function; it is also a useful audiological method for evaluating patients complaining of tinnitus. In our evaluation of DPOAEs, the intensities (dB SPL) over each 2f1-f2 measurement share a similar curved line compared to pure tone audiometry data, which represented better performance over lower frequencies, gradually declining over mid and high frequencies but displaying an up-turn phenomenon over 6 kHz [Fig. 3], and can be differentiated from presbycusis. We found that 21.1–65.8% patients showed mid-frequency (1595–2249 Hz) OAE abnormalities despite a hearing threshold within the normal limit [Table 2]. Similar results have been described previously [33]. OAE abnormalities that suggest outer hair cell damage will present prior to PTA threshold changes in NIHL associated tinnitus. However, pre-treatment and post-treatment DPOAE data showed no significant difference in our study.

A small but significant improvement was observed in THI-total scores following zinc treatment (from 38.3 to 30.0; p = 0.024). These results are compatible with the findings of Arda et al., which also showed improvement of tinnitus severity scale (TSS) from 5.3 to 2.8 after zinc supplementation [5]. The THI probes the functional, emotional, and catastrophic response reactions to tinnitus and does not appear to be affected by age, gender, or hearing loss. A significant decrease was observed following treatment for THI-catastrophic (p = 0.01) and, THI-emotional (p = 0.032) but not for THI-functional scores (p = 0.124).That is, positive responses to the items on the catastrophic subscale characterize the most severe reactions to the tinnitus sensation (eg, intrusiveness, desperation, loss of control, fear of serious disease). In addition, the items establishing the catastrophic subscale may represent those areas most responsive to treatment and may produce the most dramatic improvements if changes are observed [21].

Our study has some limitations. First, we evaluated a relatively small study population without a zinc control placebo group. The internal control group used in the study was to compare zine level in tinnitus patients and healthy control [34]. It should be better to choose those with tinnitus due to NIHL but not given zinc supplement. However, the study was still valid as comparison was done between pre and post treatment [22]. We suggest that further studies increase the number of patients, lengthen the study period, and design a double-blind randomized clinical trial to verify the placebo effect of zinc supplementation on NIHL associated tinnitus. The second limitation is that the degree of zinc absorption appears to decrease with age. Thus, it would be useful to subgroup patients according to age in order to verify the effect of administering the same zinc dosage to patients of various ages.

Conclusion

This is the first study to evaluate the effectiveness of zinc supplementation on NIHL associated tinnitus. OAE abnormalities that suggest outer hair cell damage will present prior to changes in the PTA threshold. Our findings demonstrated that THI scores improved significantly following zinc supplementation in patients with NIHL associated tinnitus. However, no improvements in objective hearing parameters were observed.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare there are no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital Research Program CMRPG8G0241 and CMRPG8G0242. The statistical data were checked by Professor Hsueh-Wen Chang of the Department of Biological Science, National Sun Yat-sen University, Taiwan.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bj.2018.10.009.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Lim D.J. Effects of noise and ototoxic drugs at the cellular level in the cochlea: a review. Am J Otolaryngol. 1986;7:73–99. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(86)80037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McReynolds M.C. Noise-induced hearing loss. Air Med J. 2005;24:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.amj.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sogebi O.A. Characterization of tinnitus in Nigeria. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2013;40:356–360. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fife T.D., Michael J., Aminoff, Robert B. 2003. Daroff encyclopedia of the neurological sciences; pp. 541–544. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arda H.N., Tuncel U., Akdogan O., Ozluoglu L.N. The role of zinc in the treatment of tinnitus. Otol Neurotol. 2003;24:86–89. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200301000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penner M.J. Variability in matches to subjective tinnitus. J Speech Hear Res. 1983;26:263–267. doi: 10.1044/jshr.2602.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nageris B.I., Raveh E., Zilberberg M., Attias J. Asymmetry in noise-induced hearing loss: relevance of acoustic reflex and left or right handedness. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28:434–437. doi: 10.1097/mao.0b013e3180430191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sayeg Porto M.A., Oliveira H.P., Cunha A.J., Miranda G., Guimaraes M.M., Oliveira W.A. Linear growth and zinc supplementation in children with short stature. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2000;13:1121–1128. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2000.13.8.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akcil E., Tug T., Doseyen Z. Antioxidant enzyme activities and trace element concentrations in ischemia-reperfusion. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2000;76:13–17. doi: 10.1385/BTER:76:1:13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rarey K.E., Yao X. Localization of Cu/Zn-SOD and Mn-SOD in the rat cochlea. Acta Otolaryngol. 1996;116:833–835. doi: 10.3109/00016489609137935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honkura Y., Matsuo H., Murakami S., Sakiyama M., Mizutari K., Shiotani A. NRF2 is a key target for prevention of noise-induced hearing loss by reducing oxidative damage of cochlea. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19329. doi: 10.1038/srep19329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shambaugh G.E., Jr. Zinc and presbycusis. Am J Otol. 1985;6:116–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shambaugh G.E., Jr. Zinc for tinnitus, imbalance, and hearing loss in the elderly. Am J Otol. 1986;7:476–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paaske P.B., Pedersen C.B., Kjems G., Sam I.L. Zinc in the management of tinnitus. Placebo-controlled trial. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100:647–649. doi: 10.1177/000348949110000809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coelho C.B., Tyler R., Hansen M. Zinc as a possible treatment for tinnitus. Prog Brain Res. 2007;166:279–285. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)66026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Person O.C., Puga M.E., da Silva E.M., Torloni M.R. Zinc supplementation for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:CD009832. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009832.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coelho C., Witt S.A., Ji H., Hansen M.R., Gantz B., Tyler R. Zinc to treat tinnitus in the elderly: a randomized placebo controlled crossover trial. Otol Neurotol. 2013;34:1146–1154. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31827e609e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim S.I., Kim M.G., Kim S.S., Byun J.Y., Park M.S., Yeo S.G. Evaluation of tinnitus patients by audiometric configuration. Am J Otolaryngol. 2016;37:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H., Song N., Li X., Lv H. Application of distortion product otoacoustic emissions to inflation of the eustachian tube in low frequency tinnitus with normal hearing. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2013;40:273–276. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore B.C., Vinay, Sandhya The relationship between tinnitus pitch and the edge frequency of the audiogram in individuals with hearing impairment and tonal tinnitus. Hear Res. 2010;261:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newman C.W., Jacobson G.P., Spitzer J.B. Development of the tinnitus Handicap inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:143–148. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1996.01890140029007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yetiser S., Tosun F., Satar B., Arslanhan M., Akcam T., Ozkaptan Y. The role of zinc in management of tinnitus. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2002;29:329–333. doi: 10.1016/s0385-8146(02)00023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gersdorff M., Robillard T., Stein F., Declaye X., Vanderbemden S. A clinical correlation between hypozincemia and tinnitus. Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 1987;244:190–193. doi: 10.1007/BF00464266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ochi K., Ohashi T., Kinoshita H., Akagi M., Kikuchi H., Mitsui M. The serum zinc level in patients with tinnitus and the effect of zinc treatment. Nihon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho. 1997;100:915–919. doi: 10.3950/jibiinkoka.100.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khazdouz M., Mazidi M., Ehsaei M.R., Ferns G., Kengne A.P., Norouzy A.R. Impact of zinc supplementation on the clinical outcomes of patients with severe head trauma: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. J Diet Suppl. 2017;15:1–10. doi: 10.1080/19390211.2017.1304486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nageris B.I., Attias J., Raveh E. Test-retest tinnitus characteristics in patients with noise-induced hearing loss. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31:181–184. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang C.H., Ko M.T., Peng J.P., Hwang C.F. Zinc in the treatment of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:617–621. doi: 10.1002/lary.21291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeBartolo H.M., Jr. Zinc and diet for tinnitus. Am J Otol. 1989;10:256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prasad A.S., Fitzgerald J.T., Hess J.W., Kaplan J., Pelen F., Dardenne M. Zinc deficiency in elderly patients. Nutrition. 1993;9:218–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martines F., Bentivegna D., Martines E., Sciacca V., Martinciglio G. Characteristics of tinnitus with or without hearing loss: clinical observations in Sicilian tinnitus patients. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2010;37:685–693. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicolas-Puel C., Faulconbridge R.L., Guitton M., Puel J.L., Mondain M., Uziel A. Characteristics of tinnitus and etiology of associated hearing loss: a study of 123 patients. Int Tinnitus J. 2002;8:37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niwa K., Mizutari K., Matsui T., Kurioka T., Matsunobu T., Kawauchi S. Pathophysiology of the inner ear after blast injury caused by laser-induced shock wave. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31754. doi: 10.1038/srep31754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Job A., Cian C., Esquivie D., Leifflen D., Trousselard M., Charles C. Moderate variations of mood/emotional states related to alterations in cochlear otoacoustic emissions and tinnitus onset in young normal hearing subjects exposed to gun impulse noise. Hear Res. 2004;193:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ochi K., Kinoshita H., Kenmochi M., Nishino H., Ohashi T. Zinc deficiency and tinnitus. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2003;30:S25–S28. doi: 10.1016/s0385-8146(02)00145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.