Abstract

The role of host genetics in influenza infection is unclear despite decades of interest. Confounding factors such as age, sex, ethnicity and environmental factors have made it difficult to assess the role of genetics without influence. In recent years a single nucleotide polymorphism, interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 (IFITM3) rs12252, has been shown to alter the severity of influenza infection in Asian populations. In this review we investigate this polymorphism as well as several others suggested to alter the host's defence against influenza infection. In addition, we highlight the open questions surrounding the viral restriction protein IFITM3 with the hope that by answering some of these questions we can elucidate the mechanism of IFITM3 viral restriction and therefore how this restriction is altered due to the rs12252 polymorphism.

Keywords: IFITM3, Influenza, IAV, Viral infection, Viral control

On the hundredth anniversary of the worst influenza pandemic ever recorded, influenza infection remains one of the most common viral infections worldwide despite extensive research and vaccination strategies. Annually the worldwide burden of infection is predicted to be ∼1 billion individuals infected, with ∼3–5 million of these having severe disease leading to 290,000 to 650,000 deaths [1]. External factors such as age, gender and ethnicity have all been predicted to play a role in determining the severity of infection. In this review, we will focus on an example of significant genetic variation on the severity of influenza infection in an ethnicity-specific manner.

Demographics of influenza infection

Age

Age has been described as an important risk factor for influenza infection severity and morbidity [2]. People over 65 years of age are at particular risk [3], [4], most likely due to immunosenescence and the associated poor response to vaccination [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. Infants less than 5 years old are also considered to be at a high-risk of infection but the reasons behind this are still unknown [10]. However, a meta-analysis from 2013 showed that this group were actually at lower risk of death and hospitalisation, but higher risk of developing pneumonia [2].

Interestingly, there seems to be a difference in mortality rate depending on whether the infection is an epidemic (one or more communities) or pandemic (worldwide) with a shift towards younger age groups during pandemics while the elderly are at risk during epidemics [4], [11]. In both age groups, the risk of complications or mortality associated with influenza infection are confounded by existing medical conditions in the individuals, making it more difficult to clearly ascertain the contribution of age.

Ethnicity

Susceptibility to influenza infection generally shows no association with ethnicity, as this data is confounded by socio-economic factors, but some research has been done to identify at risk groups [2]. In particular, indigenous ethnicity has been described as a risk factor with an elevated mortality rate or hospitalisation rate compared to European descendants in a study conducted in Canada [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]. Additionally, an interesting feature of the 1918 pandemic was that the mortality rate was relatively low in Chinese populations [17]. While this may be a result of poor record keeping, it is an interesting idea to bear in mind that some populations may respond better or worse to different influenza strains.

Gender

The sex of the individual has also been hypothesised to play a role in severity of influenza infection [18], [19], [20]. Higher morbidity associated with influenza infection in males compared to females has previously been demonstrated in one study [21], but generally there is little evidence for a contribution of sex in influenza infection. However, it is likely that this is due to the data not being separated into age groups as there is some evidence in certain age categories that sex may an important determinant of disease severity [18].

In the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, overall, more women than men were hospitalised. This may be indicative of the fact that women generally mount higher immune responses to viruses compared to men [18]. However, it is more likely a result of immunocompromise during pregnancy, as many of the hospitalised female patients were pregnant [22].

Genetic association with influenza virus infection

In recent years there has been an increase in evidence of a genetic association between the host and the severity of influenza infection, with a significant heritable contribution to fatal outcome clear [23], [24]. It has been known for several decades that different mouse strains respond to the same influenza infection in varying levels of severity, supporting the idea that genetic variance can affect influenza infection [25], [26], [27], [28], [29].

In humans, there is evidence that homozygosity for the CCR5-Δ32 allele, a naturally occurring variant of the chemokine receptor CCR5, is associated with increased susceptibility to West Nile Virus and Influenza virus infection [30]. A patient with homozygous null mutations in the Interferon Regulatory Factor 7 (IRF7) gene displayed a severely impaired antiviral response with reduced expression of type I and III interferons [31].

The anti-viral factor MXA (Mx1 in mice) also shows some natural genetic variance and investigations into the role of this variance in influenza susceptibility are on-going [32]. However, it has been shown that MXA restricts influenza A virus (IAV) infection in a strain-specific manner suggesting that this interaction may be more dependent on viral variance rather than host genetics [33], [34], [35]. Many common inbred laboratory mouse stains which are susceptible to influenza infection have an inactive Mx1 gene due to exon deletion or nonsense mutation which causes termination of translation to protein [26], [27], [28].

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in several genes have been found to be associated with influenza infection severity including TLR2 rs5743708, TLR3 rs5743313 & rs5743315, TLR4 rs4986790 & rs4986791 and CD55 rs22564978 [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]. These SNPs have been demonstrated to induce weakened host responses to influenza infection and impaired signalling function.

The most prevalent genetic association with influenza infection is the association between the C variant of the SNP rs12252 within interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 (IFITM3) and severe influenza [41], [42], which is discussed in more detail below. Interestingly, presence of the CC genotype of both IFITM3 rs12252 and TLR3 rs5743313 cumulatively led to an increased death risk with influenza infection [43].

The previous examples highlight how disruption of antiviral immunological responses can increase disease pathogenesis. SNPs affecting genes with direct influenza interactions have also been identified as risk variants for influenza virus infection. For example, SNPs in the antimicrobial genes Surfactant Protein A2 (SFTPA2) and Galectin-1 have been implicated as risk factors for severe influenza [44], [45]. These proteins are found in the airways, and can directly interact with influenza virus, limiting its replication. A SNP affecting the expression of Transmembrane Protease Serine 2 (TMPRSS2), a host protease involved in haemagglutinin cleavage, has also been associated with severe influenza infection [46].

A genome wide association study (GWAS) performed on a small cohort of 156 Spanish patients stratified into mild and severely infected individuals found only one risk variant [47]. This SNP, rs28454025, is located inside an intron of the PEAK1-Related Kinase-Activating Pseudokinase 1 (PRAG1) gene. Given this gene's role in neural development, the authors concluded that this was a false positive.

For all of the SNPs previously mentioned the confounding factor seems to be ethnicity, with most SNPs showing variable distribution across ethnic groups [48]. This and the lack of clinical samples for influenza infection have made it difficult to draw any firm conclusions about the association between genetic variants and influenza infection. Additional large-scale cohort studies will be required to investigate the role of genetics in influenza infection in the future.

IFITM3

As mentioned above, genetic variation within IFITM3 has been associated with influenza infection severity. The interferon (IFN) induced trans-membrane protein IFITM3 is an important anti-viral factor shown to restrict replication of around seventeen, mostly enveloped RNA viruses including influenza A virus (IAV), human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1), Ebola and Dengue virus [42], [49], [50], [51], [52]. Presence of IFITM3 impairs viral propagation, effects severity of infection and improves the cellular defence against viruses [42], [49], [52]. In addition to this role in virus restriction, IFITM3 has been shown to restrict cytomegalovirus [53] and Sendai virus [54] through restriction of cytokine production, mechanisms independent of direct viral restriction. This is interesting due to the finding that hypercytokinemia in influenza infection can lead to more rapid progression of disease in both humans [55] and mice [42].

IFITM3 rs34481144

The minor allele (A) of the rs34481144 SNP, found within the promoter of IFITM3, has recently been found to be associated with increased severity of IAV infection [56]. This SNP was shown to associate strongly with expression levels of IFITM3 mRNA, making it an Expression Quantitative Trait Locus (eQTL).

Further work implicated the A allele of this SNP in enhanced binding of CTCF to the IFITM3 promoter, which has a repressive effect on IFITM3 expression. Finally, this study associated the A allele with enhanced methylation on the IFITM3 promoter of CD8+ T cells in nasal washes, and general transcriptional repression of the IFITM3 genomic neighbourhood. The latter phenomenon was attributed to the fact that CTCF has been found to associate with broad changes in regional expression via alteration of chromosome topology.

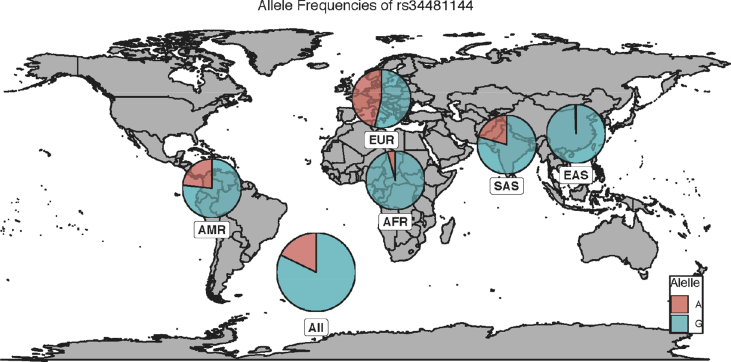

rs34481144 shows relatively even allele frequencies in European populations [Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) = 0.462] compared to the low frequency seen in East Asian populations (MAF = 0.006) [Fig. 1] [57].

Fig. 1.

Worldwide distribution of IFITM3 rs34481144. The distribution of the major (G) and minor (A) alleles of IFITM3 rs34481144 is shown according to their distribution worldwide. Abbreviations: EUR: European; SAS: South Asian; EAS: East Asian; AFR: African; AMR: American. Data taken from the 1000 genomes project.

IFITM3 rs12252

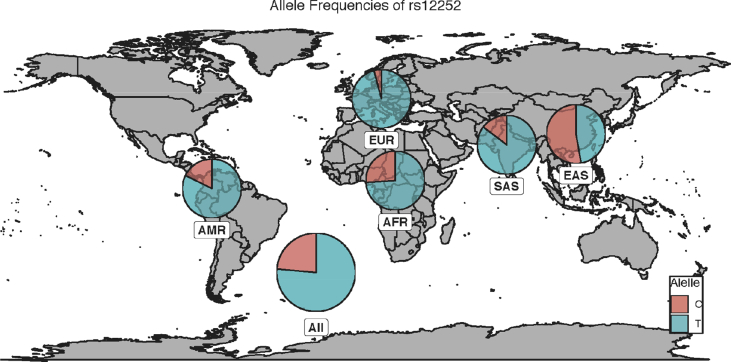

The rs12252 SNP is a synonymous SNP within the first exon of IFITM3 and has been associated with increased severity in influenza infection, as well as faster progression to AIDS with HIV-1 infection [41], [42], [58]. In opposition with rs34481144, this SNP is common in Asian populations (MAF = 0.528) but rare in European populations (MAF = 0.041) [Fig. 2] [59]. This makes combinatorial analyses between these two SNPs difficult, although it is potentially feasible in populations with intermediate allele frequencies for both alleles. Interestingly, Randolph et al reported that every instance of the CC rs12252 genotype (minor) was associated with the GG genotype (major) of rs34481144, indicating that, in European populations, the risk variants for each allele are on opposite haplotypes [60].

Fig. 2.

Worldwide distribution of IFITM3 rs12252. The distribution of the major (T) and minor (C) alleles of IFITM3 rs34481144 is shown according to their distribution worldwide. Abbreviations: EUR: European; SAS: South Asian; EAS: East Asian; AFR: African; AMR: American. Data taken from the 1000 genomes project.

There are some studies where this association between IFITM3 rs12252 and influenza severity has not been found [60], [61], [62]. However, this lack of association is likely due to the very low number of rs12252-CC patients included and the fact those most patients were from Caucasian, European populations. Especially as a recent meta-analysis confirmed the association between rs12252-CC and influenza severity [63].

When this SNP was first reported it was suggested that the C allele might create an alternative splicing site, generating a protein with a 21 amino acid deletion at the N-terminus [42]. Model experiments using Δ21-IFITM3 showed that this truncated version of the protein was mostly translocated to the plasma membrane and therefore it did not restrict viral infection by influenza or HIV-1 as well as it’s full length counterpart [64], [65], [66], [67]. Recently, however, it has been shown that the C-variant of rs12252 is capable of generating full-length IFITM3 protein, with the truncated version only present in negligible levels, if at all [60], [68]. This suggests that a truncated version of IFITM3 is unlikely to lead to the differences in viral restriction previously seen.

The mechanism behind why this SNP is so important in viral restriction is still unclear and a question that we feel will remain open until the mechanism of action of IFITM3 and indeed more information in general about this important protein is available. As such, for the remainder of this article we will focus on what is known about IFITM3 and present the remaining open questions that may be integral for determining the role of rs12252.

IFITM3 function

The mechanism of how IFITM3 restricts viruses has yet to be fully elucidated, however, it is likely that IFITM3 forms part of the membrane composition of endosomal compartments where it prevents viral entry into the cytosol [50], [64], [69]. Evidence for this comes from the fact that the early stages of influenza infection such as binding to the sialic acid receptor, endocytosis and trafficking to the late endosome are conserved in the presence of IFITM3 [50], [64], [70]. It was thought that IFITM proteins might reduce membrane fluidity through an increase of endosomal cholesterol altering the curvature of the membrane to impede hemifusion [69], [71]. However, a more recent study suggests that IFITM3 only functions to block release of viral particles post-hemifusion but prior to pore formation [72].

While it is clear that IFITM3 restricts viral infection by preventing release of viral particles into the cytoplasm, the mechanism by which it achieves this is still unclear. SNPs within IFITM3, rs12252 and rs34481144, have been demonstrated to alter severity of influenza infection [41], [42], [56]. Elucidation of the mechanism of action of IFITM3 is of high priority in order to help establish how these SNPs contribute to variability of influenza infection.

IFITM3 protein characteristics

IFITM3 structure

IFITM3 is one of five IFITM genes found in humans. While IFITM5 and IFITM10 have diverse functions and structures that are beyond the scope of this review, IFITM1, IFITM2 and IFITM3 are highly homologous and share similar functions suggesting that they have diverged from a single gene. IFITM2 and IFITM3 have very high homology, only differing by 16 amino acids, presumably, creating a very similar structure for each. IFITM1 however, has a shorter N-terminus and a longer C-terminus [73], [74].

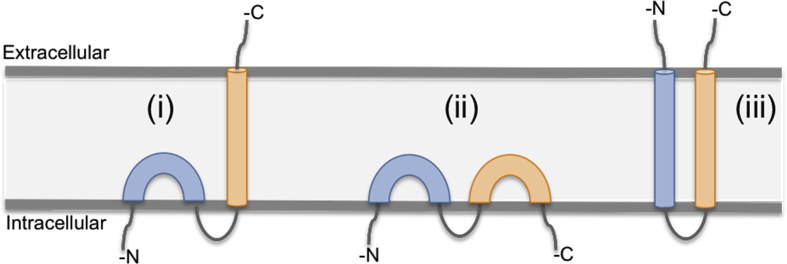

The IFITM3 protein is only 133 amino acids in length with two transmembrane domains, meaning that the majority of the protein structure is found within the membrane [75]. Due to this highly hydrophobic nature of the protein no crystal structures are available. Instead three membrane topology models for IFITM3 have been generated based on the data available [Fig. 3], suggesting that IFITM3 is either:

-

(i)

An intramembrane helix with a C-terminal transmembrane helix [79], [80];

-

(ii)

An intramembrane protein with both termini cytoplasmic [64], [78];

-

(iii)

A dual-pass protein with the C- and N-termini on the extracellular side of the membrane [40], [76], [77].

Fig. 3.

Topology models of IFITM3. The exact topology of IFITM3 is unknown due to its highly hydrophobic nature. However, there are three models that are currently considered: (i) An intramembrane helix with a C-terminal transmembrane helix; (ii) An intramembrane protein with both termini cytoplasmic; (iii) A dual-pass protein with the C- and N-termini on the extracellular side of the membrane. Adapted from Ref. [81].

Recent evidence from NMR studies suggests that the most likely conformation is most similar to model (i), with the hydrophobic region of IFITM3 adopting a topology containing two short intramembrane α-helices followed by a long transmembrane α-helix [81]. These short helices are predicted to induce membrane curvature, potentially maintaining endosomal compartments and preventing viral release.

Post-translational modifications of IFITM3

Several post-translational modifications of the IFITM3 protein have been described including S-Palmitoylation (S-PALM), phosphorylation and ubiquitination [64], [78], [82], [83].

S-PALM on membrane neighbouring cysteines was indicated to play an important role in the membrane association of IFITM3, with S-PALM-deficient mutants showing lower antiviral activity and less membrane association [78], [84]. Furthermore, S-PALM seems to be necessary for correct trafficking of the IFITM proteins, with John et al hypothesising that IFITM gets its S-PALM modification in the Golgi compartment, then traffics to the cell surface prior to endocytosis and incorporation into late endosomes and lysosomes [85].

Poly-ubiquitination on lysine amino acids (K24, K48 and K63) led to a reduction in antiviral activity of IFITM3, most likely due to an increase in protein degradation [64], [78]. Chesarino et al proposed NEDD4 as the main ligase for IFITM3 poly-ubiquitination and therefore as a potential target for drugs aiming to increase IAV resistance [82].

The phosphorylation of the tyrosine at position 20 of IFITM3 (Y20) was described as necessary for the co-localisation of IFITM3 with late endosomes and lysosomes and its antiviral function [64], [67], [85]. Interestingly, IFITM1, which lacks Y20, is located at the cell membrane rather than the acidic compartments [85]. Phosphorylation of Y20 decreases the ubiquitination of IFITM3 [83]. Taken together this suggests that post-translational modifications may help to control the level of IFITM3 expression within a cell as well as its locality.

IFITM3 localisation

It is widely agreed that IFITM3 must be located within the endosomal pathway of cells in order to restrict the range of viruses it does, however the exact compartment of this pathway or whether IFITM3 is present in all compartments is still under debate, despite several previous studies. Generally, this lack of a conclusive answer is due to a lack of suitable reagents for studying IFITM3 expression, with most commercial antibodies being cross-reactive for IFITM2. Researchers have thus used these cross-reactive antibodies, murine systems or overexpression tagged protein systems for any localisation experiments, all of which have their downfalls.

Using cross-reactive antibodies, it was shown that IFITM2/3 co-localised with the late endosomal marker Rab7 and the lysosomal markers LAMP1, LAMP2 and CD63 [50], [67], [85]. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts also exhibited co-localisation between IFITM3 and LAMP1 [82]. Using a haemagglutinin tag (HA) to IFITM3, Yount et al showed co-localisation with the endoplasmic reticulum (Calreticulin) and early endosomes (Rab5) [78]. Another study using FLAG-IFITM3 showed co-localisation between IFITM3 and the early endosome (EEA1) and lysosome (CD63) compartments [64].

Although some of this data is in agreement, the breadth of IFITM3 co-localisation in the various compartments serves to highlight the limitations of these investigations. Potentially, IFITM3 is expressed in all compartments, however, it is also possible that IFITM3 is expressed in one compartment and IFITM2 another and tagged systems may alter localisation. The latter was beautifully shown by Williams et al, who showed IFITM3 to co-localise with LAMP2 in the presence of a cross-reactive antibody and in a C-myc-tagged system but not in a FLAG-tagged system [67]. Determining the localisation of IFITM3 confidently will help to establish its mechanism in viral control.

Constitutive expression of IFITM3

It has recently been shown that stem cells highly express certain interferon stimulated genes (ISGs), including IFITM3, as an innate anti-viral mechanism [86]. Stem cells are refractive to IFN stimulation and so these ISGs are expressed constitutively as a protection mechanism that is lost with differentiation. This suggests that in differentiated cells expression of ISGs such as IFITM3 is low or non-existent constitutively but strongly induced by IFN stimulation.

However, it seems that in the case of IFITM3 it is not as simple as this, with data from multiple sources, including our own laboratory, showing that the constitutive expression of IFITM3 can vary by cell type. In mice, constitutive expression of IFITM3 has been demonstrated in the lung upper and lower airways, visceral pleura and tissue-resident leukocytes [87]. Additionally, following IAV infection in mice, IAV-specific tissue-resident memory T cells in the lung mucosa can withstand viral infection during a second challenge by maintaining expression of IFITM3 [88]. For humans, the protein atlas database shows data suggesting that both protein and RNA levels of IFITM3 are variable across cell types [89], [90].

Determining how the constitutive expression of IFITM3 varies on different cell types may potentially have implications for the mechanism of IFITM3 anti-viral protection with regards to viral tropism. It may be that viruses favour cells or organs with low intrinsic IFITM3 expression in order to give themselves an advantage at the early stages of infection. Studies focussing on the expression pattern of IFITM3 without the confounding effect of IFITM2 expression are an important area of IFITM3 research in the future.

Interferon induction of IFITM3

In humans, there are three types of IFN: Type I (IFN-α, IFN-β, IFN-ε, IFN-κ and IFN-ω), Type II (IFN-γ) and Type III (IFN-λ) [91], [92], [93], [94] with each type signaling through a different receptor [95], [96], [97], [98], [99]. IFITM3 is induced by cytokines such as IL-6 [87] but predominantly by interferons through the two IFN stimulated response elements (ISRE) and one gamma-interferon activation site (GAS) directly upstream of the promoter and enhancer regions. Previously, it has been shown that Type I and II IFNs highly induce IFITM3 expression [100]. The effect of Type III IFN stimulation has not been widely studied, although one mouse study stated that type III IFN did not induce IFITM3 expression while types I and II did [87].

The differential response of the IFITM3 gene to IFN stimulation may be a reflection of differences in IFN receptor expression on these cells. The IFNAR and IFNGR receptors are known to be ubiquitously expressed on all cell types compared to the limited expression of the type III IFN receptors.

Conclusions

With the apparent role of host genetics in susceptibility to influenza infection becoming clearer over recent years, the role of proteins like IFITM3 in viral restriction will become even more important. Despite knowledge of a genetic link between influenza infection severity and IFITM3 genotype, the mechanism for this link is still unknown. A better understanding of how rs12252 leads to such a differential outcome in infection is needed.

Funding

The authors of this review are funded by Medical Research Council, UK.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

Contributor Information

Dannielle Wellington, Email: Dannielle.Wellington@rdm.ox.ac.uk.

Tao Dong, Email: tao.dong@imm.ox.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Iuliano A.D., Roguski K.M., Chang H.H., Muscatello D.J., Palekar R., Tempia S. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet (London, England) 2018;391:1285–1300. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33293-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mertz D., Kim T.H., Johnstone J., Lam P.P., Science M., Kuster S.P. Populations at risk for severe or complicated influenza illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f5061. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO . 2011. Manual for the laboratory diagnosis and virological surveillance of influenza. Technical report. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemaitre M., Carrat F., Rey G., Miller M., Simonsen L., Viboud C. Mortality burden of the 2009 A/H1N1 influenza pandemic in France: comparison to seasonal influenza and the A/H3N2 pandemic. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aspinall R., Del Giudice G., Effros R.B., Grubeck-Loebenstein B., Sambhara S. Challenges for vaccination in the elderly. Immun Ageing. 2007;4:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nikolich-Žugich J. Ageing and life-long maintenance of T-cell subsets in the face of latent persistent infections. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:512–522. doi: 10.1038/nri2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Globerson A., Effros R.B. Ageing of lymphocytes and lymphocytes in the aged. Immunol Today. 2000;21:515–521. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01714-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Straub R.H., Cutolo M., Zietz B., Schölmerich J. The process of aging changes the interplay of the immune, endocrine and nervous systems. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;122:1591–1611. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pawelec G., Akbar A., Caruso C., Effros R., Grubeck-Loebenstein B., Wikby A. Is immunosenescence infectious? Trends Immunol. 2004;25:406–410. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mauskopf J., Klesse M., Lee S., Herrera-Taracena G. The burden of influenza complications in different high-risk groups: a targeted literature review. J Med Econ. 2013;16:264–277. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2012.752376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller M., Viboud C., Simonsen L., Olson D.R., Russell C. Mortality and morbidity burden associated with A/H1N1pdm influenza virus: who is likely to be infected, experience clinical symptoms, or die from the H1N1pdm 2009 pandemic virus ? PLoS Curr. 2009;1 doi: 10.1371/currents.RRN1013. RRN1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zarychanski R., Stuart T.L., Kumar A., Doucette S., Elliott L., Kettner J. Correlates of severe disease in patients with 2009 pandemic influenza (H1N1) virus infection. CMAJ. 2010;182:257–264. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mamelund S.E. Geography may explain adult mortality from the 1918-20 influenza pandemic. Epidemics. 2011;3:46–60. doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.La Ruche G., Tarantola A., Barboza P., Vaillant L., Gueguen J., Gastellu-Etchegorry M. The 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza and indigenous populations of the Americas and the Pacific. Euro Surveill. 2009;14 doi: 10.2807/ese.14.42.19366-en. pii=19366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flint S.M., Davis J.S., Su J.Y., Oliver-Landry E.P., Rogers B.A., Goldstein A. Disproportionate impact of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza on indigenous people in the top end of Australia's northern territory. Med J Aust. 2010;192:617–622. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson N., Barnard L.T., Summers J.A., Shanks G.D., Baker M.G. Differential mortality rates by ethnicity in 3 influenza pandemics over a century, New Zealand. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:71–77. doi: 10.3201/eid1801.110035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng K.F., Leung P.C. What happened in China during the 1918 influenza pandemic? Int J Infect Dis. 2007;11:360–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein S.L., Passaretti C., Anker M., Olukoya P., Pekosz A. The impact of sex, gender and pregnancy on 2009 H1N1 disease. Biol Sex Differ. 2010;1:5. doi: 10.1186/2042-6410-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viboud C., Eisenstein J., Reid A.H., Janczewski T.A., Morens D.M., Taubenberger J.K. Age- and sex-specific mortality associated with the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic in Kentucky. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:721–729. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs J.H., Archer B.N., Baker M.G., Cowling B.J., Heffernan R.T., Mercer G. Searching for sharp drops in the incidence of pandemic A/H1N1 influenza by single year of age. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quandelacy T.M., Viboud C., Charu V., Lipsitch M., Goldstein E. Age- and sex-related risk factors for influenza-associated mortality in the United States between 1997–2007. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179:156–167. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joseph K.S., Liston R.M. H1N1 influenza in pregnant women. BMJ. 2011:342. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3237. d3237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albright F.S., Orlando P., Pavia A.T., Jackson G.G., Cannon Albright L.A. Evidence for a heritable predisposition to death due to influenza. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:18–24. doi: 10.1086/524064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taubenberger J.K., Morens D.M. The pathology of influenza virus infections. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:499–522. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.154316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Srivastava B., Błażejewska P., Heßmann M., Bruder D., Geffers R., Mauel S. Host genetic background strongly influences the response to influenza a virus infections. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindenmann J. Resistance of mice to mouse-adapted influenza A virus. Virology. 1962;16:203–204. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(62)90297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindenmann J., Lane C.A., Hobson D. The resistance of A2G mice to myxoviruses. J Immunol. 1963;90:942–951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Staeheli P., Haller O., Boll W., Lindenmann J., Weissmann C. Mx protein: constitutive expression in 3T3 cells transformed with cloned Mx cDNA confers selective resistance to influenza virus. Cell. 1986;44:147–158. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90493-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krug R.M., Shaw M., Broni B., Shapiro G., Haller O. Inhibition of influenza viral mRNA synthesis in cells expressing the interferon-induced Mx gene product. J Virol. 1985;56:201–206. doi: 10.1128/jvi.56.1.201-206.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keynan Y., Juno J., Meyers A., Ball T.B., Kumar A., Rubinstein E. Chemokine receptor 5 Δ32 allele in patients with severe pandemic (H1N1) 2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1621–1622. doi: 10.3201/eid1610.100108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ciancanelli M.J., Huang S.X., Luthra P., Garner H., Itan Y., Volpi S. Infectious disease. Life-threatening influenza and impaired interferon amplification in human IRF7 deficiency. Science. 2015;348:448–453. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin T.Y., Brass A.L. Host genetic determinants of influenza pathogenicity. Curr Opin Virol. 2013;3:531–536. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dittmann J., Stertz S., Grimm D., Steel J., Garcia-Sastre A., Haller O. Influenza A virus strains differ in sensitivity to the antiviral action of Mx-GTPase. J Virol. 2008;82:3624–3631. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01753-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zimmermann P., Manz B., Haller O., Schwemmle M., Kochs G. The viral nucleoprotein determines Mx sensitivity of influenza A viruses. J Virol. 2011;85:8133–8140. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00712-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manz B., Dornfeld D., Gotz V., Zell R., Zimmermann P., Haller O. Pandemic influenza A viruses escape from restriction by human MxA through adaptive mutations in the nucleoprotein. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003279. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Esposito S., Molteni C.G., Giliani S., Mazza C., Scala A., Tagliaferri L. Toll-like receptor 3 gene polymorphisms and severity of pandemic A/H1N1/2009 influenza in otherwise healthy children. Virol J. 2012;9:270. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hidaka F., Matsuo S., Muta T., Takeshige K., Mizukami T., Nunoi H. A missense mutation of the Toll-like receptor 3 gene in a patient with influenza-associated encephalopathy. Clin Immunol. 2006;119:188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Antonopoulou A., Baziaka F., Tsaganos T., Raftogiannis M., Koutoukas P., Spyridaki A. Role of tumor necrosis factor gene single nucleotide polymorphisms in the natural course of 2009 influenza A H1N1 virus infection. Int J Infect Dis. 2012;16:e204–e208. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou J., To K.K., Dong H., Cheng Z.S., Lau C.C., Poon V.K. A functional variation in CD55 increases the severity of 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:495–503. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen C., Wang M., Zhu Z., Qu J., Xi X., Tang X. Multiple gene mutations identified in patients infected with influenza A (H7N9) virus. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25614. doi: 10.1038/srep25614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Y.H., Zhao Y., Li N., Peng Y.C., Giannoulatou E., Jin R.H. Interferon-induced transmembrane protein-3 genetic variant rs12252-C is associated with severe influenza in Chinese individuals. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1418. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Everitt A.R., Clare S., Pertel T., John S.P., Wash R.S., Smith S.E. IFITM3 restricts the morbidity and mortality associated with influenza. Nature. 2012;484:519–523. doi: 10.1038/nature10921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee N., Cao B., Ke C., Lu H., Hu Y., Tam H.C. IFITM3, TLR3, and CD55 genes SNPs and cumulative genetic risks for severe outcomes in Chinese patients with H7N9/H1N1pdm09 influenza. J Infect Dis. 2017;216:97–104. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herrera-Ramos E., Lopez-Rodriguez M., Ruiz-Hernandez J.J., Horcajada J.P., Borderias L., Lerma E. Surfactant protein A genetic variants associate with severe respiratory insufficiency in pandemic influenza A virus infection. Crit Care. 2014;18:R127. doi: 10.1186/cc13934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen Y., Zhou J., Cheng Z., Yang S., Chu H., Fan Y. Functional variants regulating LGALS1 (Galectin 1) expression affect human susceptibility to influenza A(H7N9) Sci Rep. 2015;5:8517. doi: 10.1038/srep08517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng Z., Zhou J., To K.K., Chu H., Li C., Wang D. Identification of TMPRSS2 as a susceptibility gene for severe 2009 pandemic A(H1N1) influenza and A(H7N9) influenza. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:1214–1221. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garcia-Etxebarria K., Bracho M.A., Galan J.C., Pumarola T., Castilla J., Ortiz de Lejarazu R. No major host genetic risk factor contributed to A(H1N1)2009 influenza severity. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135983. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Horby P., Nguyen N.Y., Dunstan S.J., Baillie J.K. The role of host genetics in susceptibility to influenza: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brass A.L., Huang I.C., Benita Y., John S.P., Krishnan M.N., Feeley E.M. IFITM proteins mediate the innate immune response to influenza a H1N1 virus, West Nile virus and dengue virus. Cell. 2009;139:1243–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Feeley E.M., Sims J.S., John S.P., Chin C.R., Pertel T., Chen L.M. IFITM3 inhibits influenza A virus infection by preventing cytosolic entry. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002337. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang I.C., Bailey C.C., Weyer J.L., Radoshitzky S.R., Becker M.M., Chiang J.J. Distinct patterns of IFITM-mediated restriction of filoviruses, SARS coronavirus, and influenza A virus. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001258. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Compton A.A., Bruel T., Porrot F., Mallet A., Sachse M., Euvrard M. IFITM proteins incorporated into HIV-1 virions impair viral fusion and spread. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:736–747. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stacey M.A., Clare S., Clement M., Marsden M., Abdul-Karim J., Kane L. The antiviral restriction factor IFN-induced transmembrane protein 3 prevents cytokine-driven CMV pathogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:1463–1474. doi: 10.1172/JCI84889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiang L.-Q., Xia T., Hu Y.-H., Sun M.-S., Yan S., Lei C.-Q. IFITM3 inhibits virus-triggered induction of type I interferon by mediating autophagosome-dependent degradation of IRF3. Cell Mol Immunol. 2017;15:858–867. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2017.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Z., Zhang A., Wan Y., Liu X., Qiu C., Xi X. Early hypercytokinemia is associated with interferon-induced transmembrane protein-3 dysfunction and predictive of fatal H7N9 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:769–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321748111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Allen E.K., Randolph A.G., Bhangale T., Dogra P., Ohlson M., Oshansky C.M. SNP-mediated disruption of CTCF binding at the IFITM3 promoter is associated with risk of severe influenza in humans. Nat Med. 2017;23:975–983. doi: 10.1038/nm.4370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.The Genomes Project C. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Y., Makvandi-Nejad S., Qin L., Zhao Y., Zhang T., Wang L. Interferon-induced transmembrane protein-3 rs12252-C is associated with rapid progression of acute HIV-1 infection in Chinese MSM cohort. AIDS. 2015;29:889–894. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zerbino D.R., Achuthan P., Akanni W., Amode M.R., Barrell D., Bhai J. Ensembl 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D754–D761. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Randolph A.G., Yip W.K., Allen E.K., Rosenberger C.M., Agan A.A., Ash S.A. Evaluation of IFITM3 rs12252 association with severe pediatric influenza infection. J Infect Dis. 2017;216:14–21. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mills T.C., Rautanen A., Elliott K.S., Parks T., Naranbhai V., Ieven M.M. IFITM3 and susceptibility to respiratory viral infections in the community. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:1028–1031. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lopez-Rodriguez M., Herrera-Ramos E., Sole-Violan J., Ruiz-Hernandez J.J., Borderias L., Horcajada J.P. IFITM3 and severe influenza virus infection. No evidence of genetic association. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35:1811–1817. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2732-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Prabhu S.S., Chakraborty T.T., Kumar N., Banerjee I. Association between IFITM3 rs12252 polymorphism and influenza susceptibility and severity: a meta-analysis. Gene. 2018;674:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.06.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jia R., Pan Q., Ding S., Rong L., Liu S.L., Geng Y. The N-terminal region of IFITM3 modulates its antiviral activity by regulating IFITM3 cellular localization. J Virol. 2012;86:13697–13707. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01828-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Compton A.A., Roy N., Porrot F., Billet A., Casartelli N., Yount J.S. Natural mutations in IFITM3 modulate post-translational regulation and toggle antiviral specificity. EMBO Rep. 2016;17:1657–1671. doi: 10.15252/embr.201642771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Foster T.L., Wilson H., Iyer S.S., Coss K., Doores K., Smith S. Resistance of transmitted founder HIV-1 to IFITM-mediated restriction. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:429–442. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Williams D.E., Wu W.L., Grotefend C.R., Radic V., Chung C., Chung Y.H. IFITM3 polymorphism rs12252-C restricts influenza A viruses. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110096. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Makvandi-Nejad S., Laurenson-Schafer H., Wang L., Wellington D., Zhao Y., Jin B. Lack of truncated IFITM3 transcripts in cells homozygous for the rs12252-C variant that is associated with severe influenza infection. J Infect Dis. 2017;217:257–262. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Amini-Bavil-Olyaee S., Choi Y.J., Lee J.H., Shi M., Huang I.C., Farzan M. The antiviral effector IFITM3 disrupts intracellular cholesterol homeostasis to block viral entry. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:452–464. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wee Y.S., Roundy K.M., Weis J.J., Weis J.H. Interferon-inducible transmembrane proteins of the innate immune response act as membrane organizers by influencing clathrin and v-ATPase localization and function. Innate Immun. 2012;18:834–845. doi: 10.1177/1753425912443392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Smith S., Weston S., Kellam P., Marsh M. IFITM proteins-cellular inhibitors of viral entry. Curr Opin Virol. 2014;4:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Desai T.M., Marin M., Chin C.R., Savidis G., Brass A.L., Melikyan G.B. IFITM3 restricts influenza A virus entry by blocking the formation of fusion pores following virus-endosome hemifusion. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004048. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lu J., Pan Q., Rong L., He W., Liu S.L., Liang C. The IFITM proteins inhibit HIV-1 infection. J Virol. 2011;85:2126–2137. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01531-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Siegrist F., Ebeling M., Certa U. The small interferon-induced transmembrane genes and proteins. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011;31:183–197. doi: 10.1089/jir.2010.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hickford D., Frankenberg S., Shaw G., Renfree M.B. Evolution of vertebrate interferon inducible transmembrane proteins. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:155. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Takahashi S., Doss C., Levy S., Levy R. TAPA-1, the target of an antiproliferative antibody, is associated on the cell surface with the Leu-13 antigen. J Immunol. 1990;145:2207–2213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Evans S.S., Lee D.B., Han T., Tomasi T.B., Evans R.L. Monoclonal antibody to the interferon-inducible protein Leu-13 triggers aggregation and inhibits proliferation of leukemic B cells. Blood. 1990;76:2583–2593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yount J.S., Karssemeijer R.A., Hang H.C. S-palmitoylation and ubiquitination differentially regulate interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 (IFITM3)-mediated resistance to influenza virus. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:19631–19641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.362095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bailey C.C., Kondur H.R., Huang I.C., Farzan M. Interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 is a type II transmembrane protein. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:32184–32193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.514356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Weston S. A membrane topology model for human interferon inducible transmembrane protein 1. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ling S., Zhang C., Wang W., Cai X., Yu L., Wu F. Combined approaches of EPR and NMR illustrate only one transmembrane helix in the human IFITM3. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24029. doi: 10.1038/srep24029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chesarino N.M., McMichael T.M., Yount J.S. E3 ubiquitin ligase NEDD4 promotes influenza virus infection by decreasing levels of the antiviral protein IFITM3. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005095. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chesarino N.M., McMichael T.M., Hach J.C., Yount J.S. Phosphorylation of the antiviral protein interferon-inducible transmembrane protein 3 (IFITM3) dually regulates its endocytosis and ubiquitination. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:11986–11992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.557694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yount J.S., Moltedo B., Yang Y.Y., Charron G., Moran T.M., Lopez C.B. Palmitoylome profiling reveals S-palmitoylation-dependent antiviral activity of IFITM3. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:610–614. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.John S.P., Chin C.R., Perreira J.M., Feeley E.M., Aker A.M., Savidis G. The CD225 domain of IFITM3 is required for both IFITM protein association and inhibition of influenza A virus and dengue virus replication. J Virol. 2013;87:7837–7852. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00481-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wu X., Dao Thi V.L., Huang Y., Billerbeck E., Saha D., Hoffmann H.-H. Intrinsic immunity shapes viral resistance of stem cells. Cell. 2018;172:423–438. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.018. e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bailey C.C., Huang I.C., Kam C., Farzan M. Ifitm3 limits the severity of acute influenza in mice. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002909. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Infusini G., Smith J.M., Yuan H., Pizzolla A., Ng W.C., Londrigan S.L. Respiratory DC use IFITM3 to avoid direct viral infection and safeguard virus-specific CD8+ T cell priming. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Uhlen M., Fagerberg L., Hallstrom B.M., Lindskog C., Oksvold P., Mardinoglu A. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347:1260419. doi: 10.1126/science.1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wu C., Jin X., Tsueng G., Afrasiabi C., Su A.I. BioGPS: building your own mash-up of gene annotations and expression profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D313–D316. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Levy D.E., Garcia-Sastre A. The virus battles: IFN induction of the antiviral state and mechanisms of viral evasion. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2001;12:143–156. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(00)00027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Samuel C.E. Antiviral actions of interferons. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:778–809. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.778-809.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kotenko S.V., Gallagher G., Baurin V.V., Lewis-Antes A., Shen M., Shah N.K. IFN-lambdas mediate antiviral protection through a distinct class II cytokine receptor complex. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:69–77. doi: 10.1038/ni875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sheppard P., Kindsvogel W., Xu W., Henderson K., Schlutsmeyer S., Whitmore T.E. IL-28, IL-29 and their class II cytokine receptor IL-28R. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:63–68. doi: 10.1038/ni873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Decker T., Muller M., Stockinger S. The yin and yang of type I interferon activity in bacterial infection. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:675–687. doi: 10.1038/nri1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Li X., Leung S., Kerr I.M., Stark G.R. Functional subdomains of STAT2 required for preassociation with the alpha interferon receptor and for signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2048–2056. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Li X., Leung S., Qureshi S., Darnell J.E., Jr., Stark G.R. Formation of STAT1-STAT2 heterodimers and their role in the activation of IRF-1 gene transcription by interferon-alpha. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5790–5794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Young H.A., Bream J.H. IFN-gamma: recent advances in understanding regulation of expression, biological functions, and clinical applications. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2007;316:97–117. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-71329-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Uze G., Monneron D. IL-28 and IL-29: newcomers to the interferon family. Biochimie. 2007;89:729–734. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lewin A.R., Reid L.E., McMahon M., Stark G.R., Kerr I.M. Molecular analysis of a human interferon-inducible gene family. Eur J Biochem. 1991;199:417–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]