Abstract

Background:

Multi-atlas segmentation, a popular technique implemented in the Automated Segmentation of Hippocampal Subfields (ASHS) software, utilizes multiple expert-labelled images (“atlases”) to delineate medial temporal lobe substructures. This multi-atlas method is increasingly being employed in early Alzheimer’s disease (AD) research, it is therefore becoming important to know how the construction of the atlas set in terms of proportions of controls and patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and/or AD affects segmentation accuracy.

Objective:

To evaluate whether the proportion of controls in the training sets affects the segmentation accuracy of both controls and patients with MCI and/or early AD at 3T and 7T.

Methods:

We performed cross-validation experiments varying the proportion of control subjects in the training set, ranging from a patient-only to a control-only set. Segmentation accuracy of the test set was evaluated by the Dice similarity coeffiecient (DSC). A two-stage statistical analysis was applied to determine whether atlas composition is linked to segmentation accuracy in control subjects and patients, for 3T and 7T.

Results:

The different atlas compositions did not significantly affect segmentation accuracy at 3T and for patients at 7T. For controls at 7T, including more control subjects in the training set significantly improves the segmentation accuracy, but only marginally, with the maximum of 0.0003 DSC improvement per percent increment of control subject in the training set.

Conclusion:

ASHS is robust in this study, and the results indicate that future studies investigating hippocampal subfields in early AD populations can be flexible in the selection of their atlas compositions.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, ASHS, high-field magnetic resonance imaging, mild cognitive impairment, multi-atlas label fusion

INTRODUCTION

The hippocampus and adjacent cortical regions play an important role in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) as they are early sites of neurofibrillary tangle pathology [1]. This has sparked interest in studying these medial temporal lobe (MTL) regions in vivo. While several studies have investigated generally larger MTL regions using T1-weighted MRI [2–4], studies of the role of more finegrained MTL subregions in AD and memory became feasible when using high-resolution T2-weighted images at high-field 3T and 7T MRI which allow for improved visualization of the inner structure of the hippocampus. So far, a considerable number of studies on the involvement of hippocampal subfields and extrahippocampal regions in AD, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [5] and even in preclinical AD [6] have been published in the last decade. However, these studies have been inconsistent with regard to which hippocampal subfields [5] and extrahippocampal cortical regions [3, 4, 7, 8] are involved in early stages of AD.

Most previous studies have a limited sample size, which may have contributed partly to the inconsistencies in the literature. More research in larger study populations is therefore needed to elucidate the role of MTL subregions in early AD. This would require automated segmentations, as the manual segmentation of hippocampal and extrahippocampal subregions is labor-intensive and not feasible in large sample sizes. Indeed, automated segmentation of hippocampal and extrahippocampal subregions is increasingly utilized [9, 10]; among others, the Automated Segmentation of Hippocampal Subfields (ASHS) tool based on multi-atlas segmentation is increasingly popular. Briefly, multi-atlas segmentation algorithms deformably register a set of expert-labelled MRI scans (called “atlases”) to the target MRI scan and combine them into a consensus segmentation [11]. However, when analyzing datasets including both controls and patients with MCI and/or AD, the best way to construct the training set (or the atlas set in the multi-atlas segmentation framework), namely the optimal patient to control atlas composition ratio in terms of segmentation accuracy, is unknown. As several large-scale studies are underway, including the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) 3 which aims to obtain a high-resolution 3T T2 sequence in over a 1000 participants [12], it is becoming increasingly important to know what atlas composition leads to the most reliable automated segmentation of a mixed dataset of control and patients. In this study, we tested different atlas compositions from scans of controls, patients with MCI and/or early AD acquired at 3T and 7T and evaluated the effect on segmentation accuracy in terms of overlap between automated and manual segmentations, as measured by the Dice similarity coefficient (DSC).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

3T:

Twenty-nine participants from a research study of aging and cognitive impairment conducted at the Penn Memory Center at the University of Pennsylvania were included. Fourteen participants received a diagnosis of amnestic MCI (referred to as the PAT-3T group) according to the Petersen et al. [13] criteria and 15 participants were cognitively normal controls (NC-3T) recruited from the community.

7T:

Patients with MCI, all but one amnesic MCI, or early-stage AD were recruited through the memory clinic of the University Medical Center Utrecht (UMCU) [14]. Diagnoses of possible and probable AD were made according to the the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke – Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association clinical criteria [15]. A diagnosis of MCI was based on Petersen criteria [13]. Participants without cognitive impairment (controls) were selected from two studies at the UMCU: (1) the Utrecht Diabetic Encephalopathy Study 2 (UDES2) [16] (25% of the subjects included in the current study had diabetes); and (2) the PREDICT-MR study [17]. Both UDES2 and PREDICT-MR recruited their subjects from general practices in Utrecht and surrounding areas. In total, 81 subjects (53 controls, 16 MCI, 12 AD) were available and 38 (19 controls, 12 MCI, 7 AD) of them were included in this study. The selection will be discussed in “MRI protocols and manual segmentations” section.

Both studies were carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Demographics of the control and patient groups of both study populations are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and volumes of different subregions and whole hippocampus for the manual segmentations of the study populations

| 3T dataset |

7T dataset |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Patients (MCI) | Controls | Patients (MCI & AD) | |

| Number | 15 | 14 | 19 | 19 (12 MCI, 7 AD) |

| Age (y) | 66.3 (9.1) | 71.9 (6.0) | 70.3 (2.5) | 75.4 (8.7) |

| Gender (% male) | 53.3 | 57.1 | 52.6 | 52.6 |

| MMSE | 29.5 (1.0) | 27.0 (1.7) | 28.7 (1.2) | 25.9 (2.3) |

| CA1 Volume | 1320.4 (163.9) | 1141.0 (238.8) | 1392.4 (268.4) | 1211.7 (247.7) |

| CA2 Volume | 24.7 (4.7) | 21.0 (6.0) | 55.0 (13.7) | 54.4 (12.7) |

| CA3 Volume | 90.6 (35.0) | 75.9 (17.8) | 115.9 (53.9) | 103.9 (25.3) |

| DG Volume | 757.8 (97.1) | 697.5 (143.6) | 760.3 (113.8) | 658.2 (153.7) |

| SUB Volume | 459.2 (63.6) | 417.4 (109.4) | 627.1 (136.5) | 554.3 (111.8) |

| ERC Volume | 609.8 (85.0) | 497.4 (126.5) | 513.4 (94.1) | 448.6 (98.0) |

| BA35 Volume | 551.3 (56.7) | 469.7 (113.1) | ||

| BA36 Volume | 1902.6 (276.0) | 1799.0 (293.9) | ||

| PHC Volume | 943.4 (163.2) | 950.7 (214.5) | ||

| Hippocampus Volume | 2652.7 (278.2) | 2352.7 (462.3) | 3084.9 (495.2) | 2722.2 (504.0) |

MCI, Mild Cognitive Impairment; AD, Alzheimer’s Disease; MMSE, Mini-Mental Status Examination; CA1–3, Cornu Ammonis 1–3; DG, Dentate Gyrus; SUB, Subiculum; ERC, Entorhinal Cortex; BA35/36, Brodmann Area 35/36; PHC, Parahippocampal Cortex. Volumes from left and right hemispheres were averaged. The patient group of the 7T dataset includes MCI and AD patients in this table. Supplementary Table 1 shows information for controls, MCI and AD of the 7T dataset separately.

MRI protocols and manual segmentations

3T:

MRI scans were acquired on a 3T Siemens Trio scanner with an 8-channel receive coil. For all participants, a T2-weighted scan with partial brain coverage angulated perpendicular to the long axis of the hippocampus was obtained with an in-plane resolution of 0.4×0.4mm2, 2mm slice thickness, and an acquisition time of 7:12min. Additionally, a T1-weighted scan was obtained at 1.0×1.0×1.0mm3 resolution during an acquisition time of 5:13min. For more details on this protocol, see Yushkevich et al. [9]. Manual segmentations were performed by author JP according to the protocol in Yushkevich et al. [9]. Cornu ammonis (CA) 1, CA2, CA3, dentate gyrus (DG), subiculum (SUB), entorhinal cortex (ERC), Brodmann area (BA) 35, BA36 [BA35 and BA36 are subregions of the perirhinal cortex (PRC)] and parahippocampal cortex (PHC) were segmented. Total hippocampal volume was defined as the sum of CA1, CA2, CA3, DG and SUB. Reliability values for manual and automated segmentations are reported in Yushkevich et al. [9].

7T:

All imaging was performed on a 7T MR scanner (Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands) with a volume transmit coil and a 16-channel receive coil (Nova Medical, Wilmington, Massachusetts) or 32-channel receive head coil (Nova Medical, Massachusetts) for participants included in the study later than May 2011. A T2-weighted turbo spin echo with 0.7×0.7×0.7mm3 resolution in an acquisition time of 10:15 minutes was obtained as well as a T1-weighted scan with 1.0×1.0×1.0mm3 resolution and an acquisition time of 1:57min. For more details on this protocol, see Wisse et al. [18]. From 81 available T2-weighted scans in total, scans from 10 controls, 4 MCI patients and 5 AD patients were considered to have relatively poor quality due to motion or other image artefacts, leaving 43 controls, 12 MCI patients and 7 AD patients for the current study. The MCI and AD patients from the 7T study population were combined (PAT-7T; n=19) and the 19 oldest subjects were selected from the control group (NC-7T) to approximate the mean age of the patient group. Manual segmentations were performed by author LW according to the protocol in Wisse et al. [18]. The same regions were segmented, but BA35, BA36 and PHC were not included in this protocol. Total hippocampal volume was defined as the sum of CA1, CA2, CA3, DG, SUB and a separate tail segment [8]. Reliability values for manual and automated segmentations are reported in Wisse et al. [18, 19]. The volumes of hippocampal subfields and the whole hippocampus from the manual segmentations are summarized in Table 1, averaged between the left and right hemispheres.

See Supplementary Figure 2 for a comparison of the two segmentation protocols.

Automatic segmentation of hippocampal subfields (ASHS)

A multi-atlas label fusion pipeline implemented in ASHS software [9] was used to automatically segment subregions of the MTL for both 3T and 7T images using corresponding atlases. ASHS combines deformable registration, joint label fusion [11], corrective machine learning [20], and bootstrapping, which are described in more detail in Supplementary Material 1.

Since some of the 7T T2-weighted MRI images in this study have poor contrast between gray matter and cerebrospinal fluid, the registration using only 7T T2-weighted images may be unreliable. In order to improve registration robustness, we extended the deformable registration step in ASHS, which originally only made use of T2-weighted MRI, to have multi-modal support. Specifically, we take the similarity of both T1-weighted and T2-weighted MRI between the source and target images into account during the optimization process. We have found this to greatly improve the robustness of the deformable registration step for 7T images and not to affect the segmentation accuracy for 3T images (data not shown).

Cross-validation experiments

Cross-validation experiments were performed separately for 3T and 7T to evaluate the accuracy of automatic segmentation for different atlas compositions. At 3T, in each cross-validation experiment, 3 NC-3T and 3 PAT-3T subjects were randomly assigned to the test set, and the remaining 12 NC-3T and 11 PAT-3T subjects were used to construct an atlas set of 11 subjects. The proportion of NC-3T was modulated (0/11, 1/11, 3/11, 5/11, 7/11, 9/11, and 11/11) across the cross-validation experiments, i.e., ranging from a PAT-only atlas to an NC-only atlas. For each given proportion of NC-3T, 10 experiments were conducted with random atlas/test assignment, for a total of 70 experiments. The expected number of times that each subject appeared in the test set was 2.0 [repetition times multiple by the probability that a subject is selected in the atlas set, in this case, 10×(3/15)=2.00]. At 7T, a similar design was followed, but with atlas set of size 16, 9 proportion levels (0/16, 2/16, . . . , 16/16), 13 experiments for each proportion level, for a total of 117 experiments, and expected number of times that each subject appears in the test set is equal to 2.14. Overall, a total of 420 3T and 702 7T bilateral segmentations were performed.

Segmentation accuracy for each subfield was measured as the DSC between its automatic and manual segmentations in each test set, and averaged between left and right hemispheres. For the compound labels including HIPPO (CA1–3, DG, and SUB) and ALL (all the gray matter labels), generalized DSC (GDSC) [21] was used. Importantly, GDSC of a compound label is generally lower than DSC of the corresponding binary label merging all the sublabels because GDSC takes the size of each sublabel into account and thus will be negatively affected by the relatively lower DSC of smaller sublabels.

Visual inspection was performed to assess the quality of the automatic segmentations and the failed cases were excluded from the specific cross-validation experiment as is a common procedure when utilizing an automated segmentation method. Because of the large number of total automatic segmentations produced in our experiments, we were not able to visually check all segmentations. Instead, we selected automated segmentations with the 5% highest and lowest entropy, the 5% lowest GDSC of the compound label “ALL”. In addition, we also included 60 randomly selected segmentations into the QC dataset to ensure that segmentations not flagged by the heuristics above did not contain significant failures. Entropy of automated segmentation is computed from the average entropy of the warped atlas labels at each voxel and is a useful indicator on ASHS pipeline failure. High entropy indicates a lot of disagreement between atlases (i.e., likely poor individual registration) and low entropy might indicate an error because the atlases agree too much (e.g., all voxels are assigned background label). Segmentations were labeled as ‘failed’ if there was a major deviation, defined as a segmentation extending well outside the anatomical structures of interest or under-segmentation of significant portions of the structures of interest. Note that if either of the bilateral segmentations failed, the case was excluded because we used DSC/GDSC averaged over both hemispheres for the statistical analyses. To assess the effect of excluding failed cases, we repeated all statistical analyses (next section) including them.

Statistical analysis

To determine if atlas composition is linked to segmentation accuracy, a two-level analysis (similar to mixed linear models) was applied. Each anatomical substructure or compound label was analyzed separately. First, for each subject, linear regression was performed with the proportion of NC (NC refers to either NC-3T or NC-7T, the same for PAT for either PAT-3T or PAT-7T) in the atlas set as the independent variable and segmentation accuracy as the dependent variable. Second, the regression coefficients from all subjects in each group (NC-3T, PAT-3T, NC-7T, PAT-7T) were entered into a one-sample t-test to test the hypothesis that there is no correlation between atlas composition and segmentation accuracy (the regression coefficients do not differ from 0). Since the regression coefficients within each group are correlated according to the experimental setup in this study, permutation tests with 104 iterations were used to generate a null distribution of the t-statistics which was used to compute the p-value of the observed t-statistics for each anatomical substructure in each subject.

In an additional analysis, we investigated whether the ASHS’ segmentation accuracy across the spectrum of proportion of control subjects in the atlas set differs between PAT and NC. For each label, a tailored two-step strategy was used to test this, accounting for the correlated nature of the samples. In the first step, two linear models were fit to the DSC/GDSC of all the test set samples. The independent variable of the first model was the proportion of control subjects in the atlas set and the second model additionally included the diagnosis of the subjects (with an interaction term). In the second step, ANOVA was performed to compare the output of the two models to obtain the observed F-statistics, which estimates the influence of including diagnosis in the model fitting. To obtain the null distribution of the observed F-statistics, we performed the analysis 104 times with the diagnoses of the subjects permuted. The p-value was computed as the proportion of times the generated F-statistics under the null distribution were larger than the observed statistic.

The analyses were performed separately for 3T and 7T imaging. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used for all the statistical analyses.

RESULTS

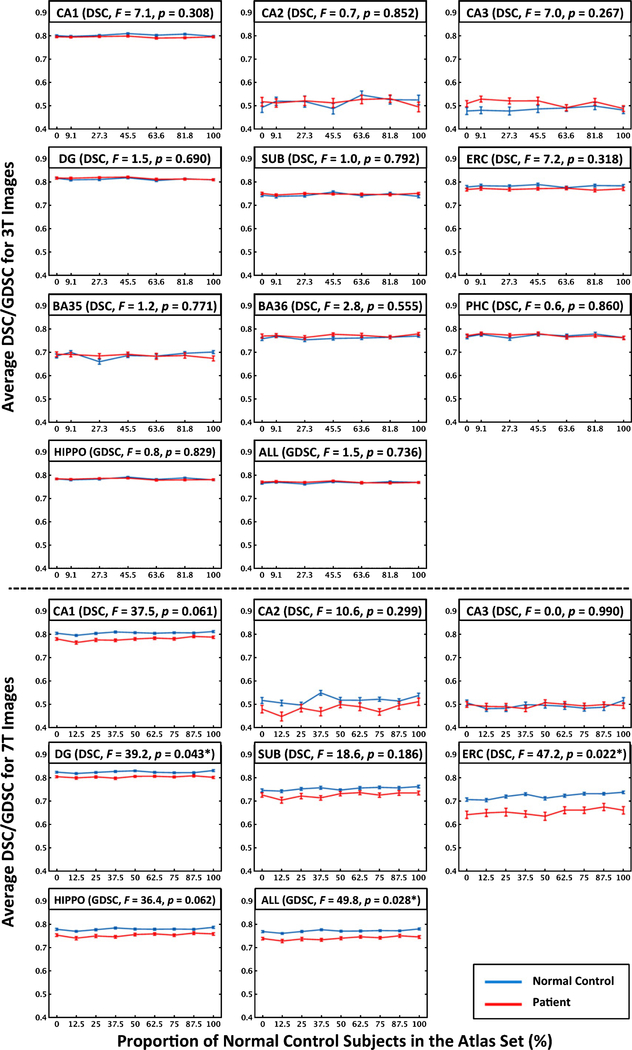

In the 7T experiments, in eleven cases out of 702, automatic segmentations were excluded due to mis-segmentation; none of the randomly selected segmentations failed. A common miss-segmentation was the undersegmentation of CA1 in the lateral portion of the hippocampus. The failed segmentations occurred in a small number of subjects (n=4) exhibiting very limited contrast between gray matter and cerebrospinal fluid on the 7T T2-weighted MRI. All automatic segmentations at 3T passed quality control. Figure 1 plots the average segmentation accuracy for each label at 3T and 7T versus the proportion of NC in the atlas set and the results of the statistical analysis testing whether segmentation accuracy differs between PAT and NC. At 3T, the overall segmentation accuracy did not differ between NC-3T and PAT-3T for any label; however at 7T, segmentation accuracy of DG, ERC, and ALL were significantly higher in NC-7T. There is no visible trend as to whether increasing the proportion of NC in the atlas set affects segmentation accuracy. This was confirmed by the analysis of the regression coefficients shown in Table 2. In 3T and in the PAT-7T group, none of the regression coefficients were significantly different from zero for any of the labels. In the NC-7T group, the regression coefficients for labels CA1, CA3, DG, SUB, ERC, and ALL were significantly above zero, however, the magnitude of the coefficients was very small, ranging from 0.0000 to 0.0003 DSC/GDSC per percent increment of NC-7T subject in the atlas set. For the largest observed regression coefficient, the expected difference in segmentation accuracy between a 100% NC-7T atlas set and a 100% PAT-7T atlas set is only 0.03 DSC. To be noted, experimental results of the 7T dataset did not notably change when including the 11 cases with failed segmentations.

Fig. 1.

Average DSC for labels of the substructures or GDSC for the compound labels, i.e., HIPPO and ALL, versus the proportion of normal control subjects in the atlas set of 3T (top) and 7T images (bottom). Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. Importantly, GDSC of a compound label is generally lower than DSC of the corresponding binary label merging all the sublabels, because GDSC takes the size of each sublabel into account and thus will be negatively affected by the relatively lower DSC of the smaller sublabels. F statistics and p value (*p<0.05) show whether segmentation accuracy (across all atlas compositions in the atlas set) differ between patients and controls for each label. Note that the comparison between 3T and 7T is not feasible because the segmentation protocols are different. The ranges of y-axis of all labels in this figure are set to be the same for easier comparison between labels. Zoomed-in view of each label is available in Supplementary Figure 1. HIPPO is the compound label of CA1–3, DG and SUB. ALL is the compound label of all the gray matter labels. of CA, cornu ammonis; DG, dentate gyrus; SUB, subiculum; ERC, entorhinal cortex; BA35/36, Brodmann area 35/36; PHC, parahippocampal cortex; HIPPO, hippocampus; DSC, Dice similarity coefficient; GDSC, generalized DSC.

Table 2.

Analysis of beta coefficients computed from linear regression of individual subjects’ DSC/GDSC versus percentage of control subjects in the atlas set

| Labels | CA1 | CA2 | CA3 | DG | SUB | ERC | BA35 | BA36 | PHC | HIPPO | All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3T | Normal controls | |||||||||||

| Mean | 0.0001 | 0.0003 | 0.0003 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | |

| STD | 0.0002 | 0.0009 | 0.0010 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | 0.0005 | 0.0003 | 0.0003 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | |

| t-stats | 1.803 | 1.430 | 0.988 | 0.800 | 0.668 | 0.686 | 1.292 | 0.339 | 1.466 | 1.465 | 1.376 | |

| p-value | 0.088 | 0.176 | 0.341 | 0.464 | 0.510 | 0.505 | 0.225 | 0.741 | 0.170 | 0.170 | 0.192 | |

| Patients with mild cognitive impairment | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | −0.0002 | −0.0001 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | −0.0002 | 0.0000 | −0.0001 | −0.0001 | −0.0001 | |

| STD | 0.0002 | 0.0006 | 0.0005 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | 0.0005 | 0.0003 | 0.0003 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | |

| t-stats | −0.559 | 0.262 | −1.400 | −1.760 | −0.436 | 0.053 | −1.629 | 0.335 | −0.627 | −1.512 | −1.052 | |

| p-value | 0.590 | 0.797 | 0.181 | 0.100 | 0.673 | 0.964 | 0.117 | 0.750 | 0.170 | 0.155 | 0.154 | |

| 7T | Normal controls | |||||||||||

| Mean | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | ||||

| STD | 0.0001 | 0.0005 | 0.0004 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | ||||

| t-stats | 3.164 | 1.328 | 2.213 | 2.097 | 4.851 | 4.828 | 3.536 | 4.517 | ||||

| p-value | 0.005* | 0.205 | 0.040* | 0.051 | <0.001* | <0.001* | 0.001* | <0.001* | ||||

| Patients with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||||

| STD | 0.0002 | 0.0006 | 0.004 | 0.0001 | 0.0003 | 0.0003 | 0.0001 | 0.0003 | ||||

| t-stats | 1.754 | 0.789 | 0.678 | −0.267 | 1.163 | 0.118 | 1.451 | 1.366 | ||||

| p-value | 0.086 | 0.452 | 0.525 | 0.808 | 0.263 | 0.912 | 0.162 | 0.200 | ||||

p<0.05

STD, standard deviation; CA1–3, cornu ammonis 1–3; DG, dentate gyrus; SUB, subiculum; ERC, entorhinal cortex; BA35/36, Brodmann area 35/36; PHC, parahippocampal cortex. p-value of the t-statistics from the one sample t-test was generated from permutation tests (10,000 iterations) for each label in each group (control and patient in 3T and 7T). Significant results are highlighted in bold. Note that the comparison between 3T and 7T is not feasible because their segmentation protocols are different.

DISCUSSION

In this study we measured the effect of modulating the proportion of controls in the atlas set on the accuracy of automated multi-atlas segmentation of hippocampal subfields and extrahippocampal cortical regions in studies of AD at 3T and 7T. The main finding is that the different atlas compositions did not differ in terms of segmentation accuracy at 3T, and although we found a significant increase in accuracy for the segmentation of controls with each control added to the atlas set for 7T, this increase was very small. The results suggest that multi-atlas segmentation using ASHS is robust to changes in atlas composition; however due to a relatively small number of subjects in this study, further replication will be necessary to confirm that this robustness can be generalized to other datasets.

To compare our segmentation accuracy of the whole hippocampus with the current literature, we also generated a binary segmentation of the hippocampus by merging the hippocampal subfield labels. The average DSCs of the whole hippocampus throughout all the experiments (including the ones that did not survive quality control) were 0.89±0.01 for 7T and 0.89±0.03 for 3T, which are comparable to the state-of-the-art methods [11, 22–25]. The DSC/GDSC values reported here for the subregions for 3T and 7T are similar to previously reported results in overlapping datasets [9, 19] but are slightly lower for some of the subregions, likely due to smaller overall atlas size in the experiments above. Interestingly, while we observed no significant difference in the segmentation accuracy between controls and MCI patients at 3T, we observed slightly, but significantly, lower DSC values (~0.03) for some labels for the patients as compared to the controls at 7T. This difference in segmentation accuracy could potentially be due to a difference in image quality (more motion artifacts and reduced contrast). It seems unlikely that this difference is due to differences in amount of atrophy, as both 3T and 7T groups show similar amounts of total hippocampal atrophy relative to the controls (~11%), or to severity of the disease population at 7T as the GDSC in the two patient groups, computed post hoc from the control-only atlas experiments, were comparable (GDSCs of the compound label “ALL” are 0.75±0.05 for AD and 0.74±0.05 for MCI patients). The segmentation accuracies for CA2 and CA3 were low, likely due to their relatively small sizes and perhaps because a large part of their boundaries are determined by heuristic rules in in vivo MRI. Indeed, these two subregions are difficult to segment, even manually, as indicated by the relatively low inter- and intra-rater reliability in prior studies [9, 19, 26, 27]. The 7T atlas did not include PRC and PHC labels, so accuracy for different atlas compositions should be evaluated in the future, especially since PRC is an early site for neurofibrillary tangle pathology [1].

The current result that the automated segmentation of hippocampal subfields and extrahippocampal regions using ASHS in controls and MCI or AD patients is at most mildly affected by atlas composition indicates that future studies can be flexible in choosing their atlases. Thus, researchers could either choose one of the existing atlases composed of elderly subjects, whether they include patients or not, or could construct their own atlas determined by their own needs. However, image quality and severity of the disease population should be taken into consideration both for atlas selection and when performing automated segmentation. The current findings have broad implications as most labs use either 3T or 7T imaging, the latter has seen increasing use (see review from Giuliani et al. [28], but also note the European Ultrahigh-Field Imaging Network for Neurodegenerative Diseases (EUFIND), an effort aiming to summarize and investigate the potential of ultrahigh-field imaging in neurodegenerative research). It should be noted that there is variability in MRI protocols at both 3T and especially at 7T, and many 7T acquisition protocols have different voxel dimensions. Indeed, most 7T groups acquire anisotropic voxels, as in the 3T data here, though with thinner slices.

Guidelines on how to compose the atlas set is especially relevant for large studies, such as ADNI-3, where manual segmentation becomes infeasible. Additionally, it might also be relevant to the harmonization effort for hippocampal subfield segmentation, as this group is planning to incorporate the harmonized protocol, once finished, in one of the existing algorithms [29, 30] (http://www.hippocampalsubfields.com). While the current findings give guidance for the atlas composition to automatically segment older populations including MCI or early AD patients, this should be replicated in larger samples sizes in future work. Moreover, as the 3T atlas did not include early AD patients, future studies should therefore confirm if the findings hold in a 3T dataset including this patient group. Relatedly, it is not clear whether these results hold for other diseases or age groups and future work should address this.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Monisa Javari, Marijke Assink, Sophie Heringa, Jurre Verwer, Femke Coenen, Elbrich Wiarda as well as the Utrecht Diabetes Encephalopathy Study Group and the Vascular Cognitive Impairment study group for their help collecting data and facilitating this study.

L.E.M.W. was supported by the donors of Alzheimer’s Disease Research, a program of the BrightFocus Foundation. R.T.S. was partially funded by R01NS085211 and R01EB017255. J.J.M.Z. was funded by the European Research Council, under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme, grant agreement n°337333. M.I.G. was supported by a grant from Alzheimer Nederland-Internationale Stichting Alzheimer Onderzoek (AN-ISAO) grant number 12504. D.A.W. was supported by National Institute of Health (grant numbers R01-AG010124, R01-AG055005). Y.D.R. receives funding from Alzheimer Nederland and ZonMw/Memorabel (grant number 733050503). P.A.Y. receives funding from National Institute of Health (grant numbers R01-AG056014 and R01-EB017255).

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/17-0932r1).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-170932.

REFERENCES

- [1].Braak H, Braak E (1995) Staging of Alzheimer’s disease-related neurofibrillary changes. Neurobiol Aging 16, 271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Barnes J, Bartlett JW, van de Pol LA, Loy CT, Scahill RI, Frost C, Thompson P, Fox NC, Gravano D, Doddrell DM, Toga AW, Morris JC, Oakley F, Schneider LS, Streim JE, Sunderland T, Teri LA, Tune LE (2009) A meta-analysis of hippocampal atrophy rates in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 30, 1711–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jauhiainen AM, Pihlajamäki M, Tervo S, Niskanen E, Tanila H, Hänninen T, Vanninen RL, Soininen H (2009) Discriminating accuracy of medial temporal lobe volumetry and fMRI in mild cognitive impairment. Hippocampus 19, 166–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Killiany RJ, Hyman BT, Gomez-Isla T, Moss MB, Kikinis R, Jolesz F, Tanzi R, Jones K, Albert MS (2002) MRI measures of entorhinal cortex vs hippocampus in preclinical AD. Neurology 58, 1188–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].de Flores R, La Joie R, Chételat G (2015) Structural imaging of hippocampal subfields in healthy aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience 309, 29–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wolk DA, Das SR, Mueller SG, Weiner MW, Yushkevich PA, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2017) Medial temporal lobe subregional morphometry using high resolution MRI in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 49, 204–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mueller SG, Schuff N, Yaffe K, Madison C, Miller B, Weiner MW (2010) Hippocampal atrophy patterns in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp 31, 1339–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wisse LEM, Biessels GJ, Heringa SM, Kuijf HJ, Koek DH, Luijten PR, Geerlings MI (2014) Hippocampal subfield volumes at 7T in early Alzheimer’s disease and normal aging. Neurobiol Aging 35, 2039–2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yushkevich PA, Pluta JB, Wang H, Xie L, Ding S, Gertje EC, Mancuso L, Kliot D, Das SR, Wolk DA (2015) Automated volumetry and regional thickness analysis of hippocampal subfields and medial temporal cortical structures in mild cognitive impairment. Hum Brain Mapp 36, 258–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Iglesias JE, Augustinack JC, Nguyen K, Player CM, Player A, Wright M, Roy N, Frosch MP, McKee AC, Wald LL, Fischl B, Van Leemput K (2015) A computational atlas of the hippocampal formation using ex vivo, ultra-high resolution MRI: Application to adaptive segmentation of in vivo MRI. Neuroimage 115, 117–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wang H, Suh JW, Das SR, Pluta J, Craige C, Yushkevich PA (2012) Multi-atlas segmentation with joint label fusion. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 35, 611–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Weiner MW, Veitch DP, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Cairns NJ, Green RC, Harvey D, Jack CR, Jagust W, Morris JC, Petersen RC, Salazar J, Saykin AJ, Shaw LM, Toga AW, Trojanowski JQ (2017) The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative 3: Continued innovation for clinical trial improvement. Alzheimers Dement 13, 561–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Petersen RC (2004) Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med 256, 183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Brundel M, Heringa SM, de Bresser J, Koek HL, Zwanenburg JJM, Jaap Kappelle L, Luijten PR, Biessels GJ (2012) High prevalence of cerebral microbleeds at 7Tesla MRI in patients with early Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 31, 259–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM (1984) Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 34, 939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Reijmer YD, Leemans A, Brundel M, Kappelle LJ, Biessels GJ, Utrecht Vascular Cognitive Impairment Study Group (2013) Disruption of the cerebral white matter network is related to slowing of information processing speed in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 62, 2112–2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wisse LEM, Biessels GJ, Stegenga BT, Kooistra M, van der Veen PH, Zwanenburg JJM, van der Graaf Y, Geerlings MI (2015) Major depressive episodes over the course of 7 years and hippocampal subfield volumes at 7 tesla MRI: The PREDICT-MR study. J Affect Disord 175, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wisse LEM, Gerritsen L, Zwanenburg JJM, Kuijf HJ, Luijten PR, Biessels GJ, Geerlings MI (2012) Subfields of the hippocampal formation at 7T MRI: In vivo volumetric assessment. Neuroimage 61, 1043–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wisse LEM, Kuijf HJ, Honingh AM, Wang H, Pluta JB, Das SR, Wolk DA, Zwanenburg JJM, Yushkevich PA, Geerlings MI (2016) Automated hippocampal subfield segmentation at 7T MRI. Am J Neuroradiol 37, 1050–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wang H, Das SR, Suh JW, Altinay M, Pluta J, Craige C, Avants B, Yushkevich PA (2011) A learning-based wrapper method to correct systematic errors in automatic image segmentation: Consistently improved performance in hippocampus, cortex and brain segmentation. Neuroimage 55, 968–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Crum WR, Camara O, Hill DLG (2006) Generalized overlap measures for evaluation and validation in medical image analysis. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 25, 1451–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Platero C, Tobar MC (2016) A fast approach for hippocampal segmentation from T1-MRI for predicting progression in Alzheimer’s disease from elderly controls. J Neurosci Methods 270, 61–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Coupé P, Manjón JV, Fonov V, Pruessner J, Robles M, Collins DL (2011) Patch-based segmentation using expert priors: Application to hippocampus and ventricle segmentation. Neuroimage 54, 940–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Collins DL, Pruessner JC (2010) Towards accurate, automatic segmentation of the hippocampus and amygdala from MRI by augmenting ANIMAL with a template library and label fusion. Neuroimage 52, 1355–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Leung KK, Barnes J, Ridgway GR, Bartlett JW, Clarkson MJ, Macdonald K, Schuff N, Fox NC, Ourselin S, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2010) Automated cross-sectional and longitudinal hippocampal volume measurement in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage 51, 1345–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Pipitone J, Park MTM, Winterburn J, Lett TA, Lerch JP, Pruessner JC, Lepage M, Voineskos AN, Chakravarty MM (2014) Multi-atlas segmentation of the whole hippocampus and subfields using multiple automatically generated templates. Neuroimage 101, 494–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dalton MA, Zeidman P, Barry DN, Williams E, Maguire EA (2017) Segmenting subregions of the human hippocampus on structural magnetic resonance image scans: An illustrated tutorial. Brain Neurosci Adv 1, 2398212817701448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Giuliano A, Donatelli G, Cosottini M, Tosetti M, Retico A, Fantacci ME (2017) Hippocampal subfields at ultra high field MRI: An overview of segmentation and measurement methods. Hippocampus 27, 481–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wisse LEM, Daugherty AM, Olsen RK, Berron D, Carr VA, Stark CEL, Amaral RSC, Amunts K, Augustinack JC, Bender AR, Bernstein JD, Boccardi M, Bocchetta M, Burggren A, Chakravarty MM, Chupin M, Ekstrom A, de Flores R, Insausti R, Kanel P, Kedo O, Kennedy KM, Kerchner GA, LaRocque KF, Liu X, Maass A, Malykhin N, Mueller SG, Ofen N, Palombo DJ, Parekh MB, Pluta JB, Pruessner JC, Raz N, Rodrigue KM, Schoemaker D, Shafer AT, Steve TA, Suthana N, Wang L, Winterburn JL, Yassa MA, Yushkevich PA, la Joie R, Hippocampal Subfields Group (2017) A harmonized segmentation protocol for hippocampal and parahippocampal subregions: Why do we need one and what are the key goals? Hippocampus 27, 3–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yushkevich PA, Amaral RSC, Augustinack JC, Bender AR, Bernstein JD, Boccardi M, Bocchetta M, Burggren AC, Carr VA, Chakravarty MM, Chételat G, Daugherty AM, Davachi L, Ding S-L, Ekstrom A, Geerlings MI, Hassan A, Huang Y, Iglesias JE, La Joie R, Kerchner GA, LaRocque KF, Libby LA, Malykhin N, Mueller SG, Olsen RK, Palombo DJ, Parekh MB, Pluta JB, Preston AR, Pruessner JC, Ranganath C, Raz N, Schlichting ML, Schoemaker D, Singh S, Stark CEL, Suthana N, Tompary A, Turowski MM, Van Leemput K, Wagner AD, Wang L, Winterburn JL, Wisse LEM, Yassa MA, Zeineh MM (2015) Quantitative comparison of 21 protocols for labeling hippocampal subfields and parahippocampal subregions in in vivo MRI: Towards a harmonized segmentation protocol. Neuroimage 111, 526–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.