Abstract

Liver fibrosis is the most common pathological outcome and the most severe complication of chronic liver diseases. Accumulating evidence suggests that miRNAs are involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, as well as the occurrence and development of various diseases. In this study, we found that the expression of let-7a was markedly decreased in the liver tissue samples and blood samples from patients with liver fibrosis compared with healthy volunteers. Furthermore, let-7a was downregulated in the liver tissues and blood samples in mouse models of liver fibrosis. Further analysis indicated that let-7a suppresses the activation level of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). In addition, overexpression of let-7a reduced cell viability and promoted apoptosis of HSCs. Western blot analysis showed that let-7a might inhibit HSCs through TGFβ/SMAD signaling pathway. The present study provides a potential accurate target and vital evidence to better understand the underlying pathogenesis for early diagnosis and treatment of liver fibrosis.

Keywords: miRNAs, hepatic stellate cells, liver fibrosis, TGFβ/SMAD

Introduction

Chronic liver diseases remain a major problem throughout the world and lead to considerable morbidity and mortality (1). The most common pathological outcome and the most severe complication of chronic liver diseases are liver fibrosis which are global health and economic burdens (2). Liver fibrosis characteristically show over-accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM), mainly type I fibrillar collagen (Collagen I) in response to chronic liver damage (3). Various etiological factors and stimuli can result in development of liver fibrosis, including viral hepatitis (hepatitis C and B), environmental carcinogens, excessive ethanol consumption, activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (4,5). Liver fibrosis is generally asymptomatic and is often overlooked by patients and their families. When patients are diagnosed with liver fibrosis, the strategies for treatment and therapeutic options are seriously limited (6). In addition, there are no vaccine or effective anti-fibrotic drugs so far, and the patients with liver fibrosis need to receive long-term and repeated drug treatments, which is difficult to accept (7). Therefore, it is necessary to search for a better therapy to directly prevent liver fibrosis, and a better understanding of pathogenesis underlying the development of liver fibrosis is urgently needed.

In recent years, therapy based on cells has been widely investigated in the area of tissue or organ protection (8). Therefore, we focus on the cells which are connected with the development of liver fibrosis. HSCs have been considered as a kind of lipocytes, which exhibit a key role in the process of liver fibrosis when the liver is damaged (9,10). HSCs are regarded as the potential aetiology because they are the key cell type which is in charge of ECM formation during hepatic fibrogenesis (11). Activation of HSCs is essential to the initiation and progression of liver fibrosis (12). When HSCs are activated, they become fibrogenic myofibroblasts and exhibit the function of fibrogenic myofibroblast-like cells, which can secrete α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), TIMP-1 and inhibit HSC cell apoptosis and collagen-I secretion (13–15). Excessive insoluble collagen I and matrix components in the intracellular and perisinusoidal spaces can bring severe compromise to the hepatic function (16,17).

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have been found to be the most abundant small non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) (18). miRNAs are a type of 18 to 25 nucleotides (nt) in length, single-stranded and evolutionary conserved endogenous RNAs (19). miRNAs can regulate the expression of post-transcriptional genes by incompletely binding with their target genes 3′-UTR. Accumulating evidence suggests that miRNAs are related to the cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis and development of various diseases (20). Recent studies have shown that miRNAs take part in the process of liver diseases, such as liver injury, hepatic cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and liver fibrosis (21–24). Moreover, there is increasing evidence that miRNAs are involved in various fibrotic diseases, including kidney, cardiac, cystic and pulmonary fibrosis (25–28). miRNAs may serve as antifibrotic or profibrotic genes during liver fibrosis. However, the mechanism effects of miRNAs need further investigation.

let-7a has been found to be involved in the development of chronic liver diseases (29). However, let-7a has not been indicated to be related to liver fibrosis. Here, we investigated the expression level of let-7a in patients with liver fibrosis to reveal the molecular mechanism of let-7a regulating the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Our study aimed to provide an accurate target and vital evidence to better understand the underlying pathogenesis for early diagnosis and treatment for liver fibrosis.

Patients and methods

Human liver samples

Liver samples were collected from patients and volunteers attending The Second Affiliated Hospital of Qiqihar Medical University (Qiqihar, China) from January, 2016 to March, 2017. Fibrotic liver samples were taken from 12 non-tumorous patients (6 males and 6 females; age range 20–40 years) who were diagnosed to have liver fibrosis. The tissues of patients were taken and after pathological examination the remaining tissues were treated with RNAKeeper (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) and stored at −80°C (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Normal liver tissues (n=12) were obtained from healthy liver transplant donors undergoing hepatic resection and regarded as controls in this study. All clinical samples were collected in The Second Affiliated Hospital of Qiqihar Medical University.

This study was approved by the Clinical Ethics Committee of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Qiqihar Medical University. All participants agreed with the research, participated in this study willingly and signed an informed consent before sample collection.

The control tissues and liver fibrosis tissues were stored at −80°C for further analysis. According to the pathological results of liver biopsy, the cases of the patients with liver fibrosis was 4 (S0), 4 (S1), 2 (S2), 1 (S3), 1 (S4). According to the different stage, the value of acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) of the patients with liver fibrosis was 0.98±0.10, 1.14±0.11, 1.38±0.40, 1.91±0.70 and 2.12±0.75 m/sec, respectively.

Collection of human blood samples

Blood samples were obtained from patients and volunteers in The Second Affiliated Hospital of Qiqihar Medical University from January, 2016 to October, 2017. Human blood samples were collected from 22 hospitalized patients who had liver fibrosis (11 males and 11 females; age range 21–40 years) and 22 age- and sex-matched healthy subjects according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board. The healthy volunteers who suffered from known acute or chronic diseases, who took medications or alcohol within 24 h or were aged less than 21 years were excluded. All human experiments were conducted according to the clinical Εthics Committee of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Qiqihar Medical University.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

The frozen liver samples were thawed and homogenized at 4°C prior to RNA isolation. TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to isolate the total RNAs from the liver samples, blood samples and cells according to the protocols. After isolation, RNAs were quantified by Nanodrop machine (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and RNAs were used in further experiments when the concentration was higher than 200 (ng/µl) and A260/280 ratio was 1.7–2.0. Single-stranded cDNAs were synthesized using reverse transcription kit (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.). For cDNA synthesis, a 10 µl reaction volume composed of 500 ng RNAs, 4 µl reverse transcriptase and double-distilled water (ddH2O) were added into 200 µl EP tubes. The reactions were initially incubated at 50°C for 15 min and then at 85°C for 5 sec.

qPCR

qPCR analysis was performed by using 10 µl SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.), 7 µl ddH2O, 1 µl cDNA and 2 µl sequence-specific primers under RT-qPCR machine (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The mixtures were placed in a 96-well plate and the conditions were: 95°C for 10 sec, 40 cycles at 95°C for 10 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. The relative expression levels of target genes were quantified by a LightCycler 480 System (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) on the basis of the threshold cycle (CT). U6 was regarded as a control gene for the expression of miRNAs. The expression of GAPDH was used to normalize the expression of other genes. All primers used in the present study were designed and synthesized by GenePharma, Shanghai, China. Primer sequences are listed in Table I.

Table I.

Primer sequences.

| Primers | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| U6 | GCTTCGGCAGCACATATACT | TTCACGAATTTGCGTGTCAT |

| GAPDH | TCCACTGGCGTCTTCACC | GGCAGAGATGATGACCCTTTT |

| hsa-let-7a | CGATTCAGTGAGGTAGTAGGTTGT | TATGGTTGTTCTGCTCTCTGTCTC |

| let-7a | GCGCCTGAGTAGTTG | CAGGGGGGGTCCGAGGT |

| Col-1 | GATTGAGAACATCCGCAGC | CATCTTGAGGTCACGGCAT |

| Col-4 | ATCTCTGCCAGGACCAAGTG | CGGGCTGACATTCCACAAT |

| α-SMA | GTCCCAGACATCAGGGAGTAA | TCGGATACTTCAGCGTCAGGA |

Cell culture

The HSC cell line LX-2 cells (cat. no. GD-C624092) were obtained from Changsha Yingrun Biotechnologies Co., Ltd. (Changsha, China). The cells were cultured in DMEM medium (Hyclone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, MT, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 100 µg/ml penicillin-streptomycin antibiotics (cat. no. C0222; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China) and 2 µM of L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). The cells were seeded in 25 cm2 flasks and grown in an incubator with 5% CO2 and 37°C (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cells were plated at a density of 5×105 cells/well and routinely subcultured using 0.25% trypsin when the confluence reached approximately 80%. The method of quantification was the 2−ΔΔCq method (30).

Cell transfection

To overexpress or silence let-7a, let-7a mimics, let-7a inhibitor, miR-NC and antagomir-NC were transfected into LX-2 cells. Transient transfections were carried out using transfection reagent X-treme (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) on the basis of previous studies. On the day prior to cell transfection, LX-2 cells were plated in 96-well or 6-well plates. Let-7a mimics, let-7a inhibitor, miR-NC and antagomir-NC were designed and synthesized by Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The concentration of let-7a-5p mimics and miR-NC was 100 nM. The concentration of let-7a-5p inhibitor and antagomir-NC was 50 nM. After 24 h transfection the cells were used for further experiments.

Cell viability analysis

LX-2 cells were placed at a density of 2×103 cells/well in 96-well plates (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA). After culture of 24 h, 20 µl volume of MTT solution (5 mg/ml, BioSharp, Hefei, China) was added and the cells were incubated for 4 h at 37°C in an incubator. Then about 150 µl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added and the plates were gently shaken. The optical density values (λ=490 nm) were detected using the enzyme linked immunosorbent assay. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

TUNEL staining

To measure the apoptosis levels of LX-2 cells, 1×105 LX-2 cells were grown in a small dish. The cells transfected with let-7a mimics, let-7a inhibitor, miR-NC and antagomir-NC were used for TUNEL staining. The culture medium in the dish was discarded, and cells were fixed in 4% PFA for 30 min at room temperature after being washed with PBS. After the closure and penetration procedures, TUNEL staining solution Vial1 and Vial2 were mixed at a ratio of 1:9 according to the instructions of the kit. Then, cells were incubated with the TUNEL reagent for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. After being washed with PBS, cells were incubated with Hoechst staining solution for 20 min at room temperature, and kept in the dark. Finally, the cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Ten images were randomly captured of every angle. The quantification of TUNEL staining was performed by measuring the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells.

Western blotting

Cells after transfection with let-7a were lysed in 500 µl volume of RIPA lysis buffer for 20 min in a 4°C freezer. After extraction, the concentration of total proteins was measured using BCA protein detection kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). After heat denaturation at 100°C for 10 min, equal amounts of extracted protein samples were separated by 8–10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membrane (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). After using 5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) to block non-specific protein binding at room temperature for 1 h, the membrane was incubated in anti-TGF-β or anti-SMAD antibody with a gentle shaking overnight at 4°C. Then, the membrane was incubated with secondary antibody and the signal was detected using an ECL system. The expression of GAPDH was used as loading control to quantify the expression of TGF-β and SMAD by using Image Studio software. For western blot analysis, anti-TGF-β (anti-rabbit; cat. no. CST3711; 1:1,000) anti-SMAD2 (anti-rabbit, cat. no. CST5339; 1:1,000), anti-SMAD3 (anti-rabbit, cat. no. 9513; 1:1,000) antibodies, the second antibody (anti-rabbit; cat. no. CST7074; 1:1,000), or the second antibody (anti-mouse; cat. no. 5571; 1:1,000) all from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., (Danvers, MA, USA) and GAPDH (anti-mouse; cat. no. sc-47724; 1:500) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., (Dallas, TX, USA).

Construction model of liver fibrosis

To generate the model of liver fibrosis, 20 female C57BL/6 mice (approximately 18–22 g) were purchased. Mice were kept at 25°C and raised for a week before experiments. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with olive oil vehicle (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and they served as the control. In addition, mouse model with liver fibrosis was intraperitoneally injected with CCl4 (0.5 µl/g, Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) which was normally used as hepatotoxic chemical twice weekly. After injections of 10 weeks, the mice were sacrificed and the liver tissues and blood samples were harvested.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed from three or more independent experiments. Analysis was performed by using GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Differences between the groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, followed by a Tukey's test for multiple comparisons. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparison between groups. P<0.05, P<0.01 and P<0.001 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Expression of let-7a in patients with liver fibrosis

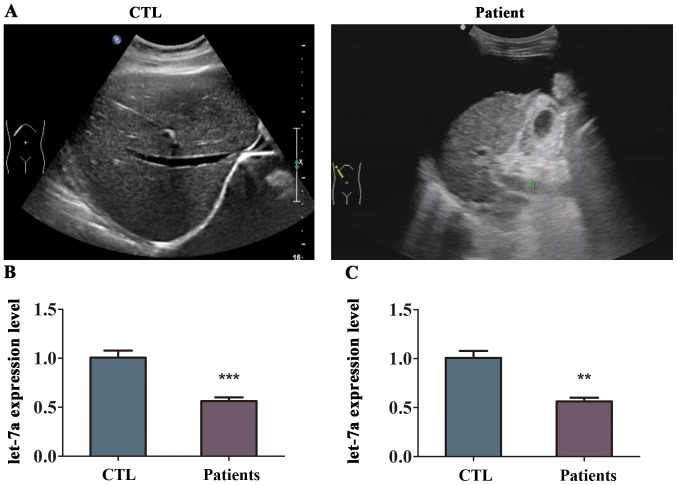

To determine whether let-7a is related to liver fibrosis, the expression of let-7a was detected in the tissues and blood samples from patients with liver fibrosis using RT-qPCR analysis. First, the analysis of supersonic inspection showed that the liver volume of patient with liver fibrosis was decreased and the tunica of liver was damaged compared with healthy volunteers (Fig. 1A). The echo in the liver from patient with liver fibrosis become deeper and weaker with uneven distribution, and the analysis showed that the hepatic vein was not clear (Fig. 1A). The level of let-7a was differentially expressed in the liver fibrosis tissues compared to normal liver tissues as indicated in Fig. 1B. The results of RT-qPCR revealed that the expression of let-7a was lower in the liver tissues from patients with liver fibrosis compared with that in healthy volunteers, and the difference was statistically significant (Fig. 1B). In addition, let-7a was markedly downregulated in the blood samples of patients with liver fibrosis (Fig. 1C). These results suggested that let-7a was reduced in patients with liver fibrosis.

Figure 1.

Expression of let-7a in patients with liver fibrosis. We collected the liver tissues and blood samples from patients with liver fibrosis and healthy controls, respectively. (A) The results of supersonic inspection from patient with liver fibrosis. (B) The expression levels of let-7a in the normal liver tissue and liver fibrosis tissue were measured by RT-qPCR. (C) The expression levels of let-7a in the blood samples from patients with liver fibrosis and healthy volunteers were measured by RT-qPCR. n=3 per group. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 compared with controls.

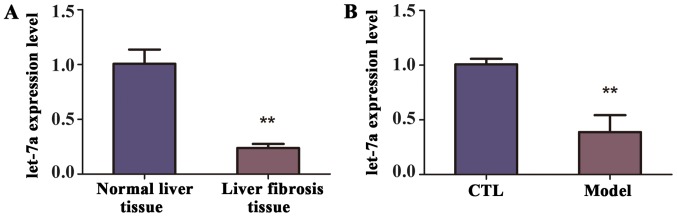

Validation of let-7a expression in mice with liver fibrosis

To identify the level of let-7a in the mice with liver fibrosis, a model of liver fibrosis was generated. Briefly, mice (n=10) were intraperitoneally injected CCl4 twice weekly for 10 weeks, while the control group (n=10) were treated with olive oil. The decreased expression of let-7a in the liver tissues from mice of liver fibrosis was revealed by RT-qPCR (Fig. 2A). Similarly, according to the RT-qPCR analysis, the expression of let-7a was observably decreased in the blood samples of mice with liver fibrosis compared with control group, and the difference was statistically significant (Fig. 2B). Therefore, we concluded that let-7a was reduced in the liver tissues and blood samples of mice with liver fibrosis.

Figure 2.

The expression of let-7a in model of liver fibrosis. Models of liver fibrosis and controls were constructed to validate whether expression of let-7a was dysregulated in the two groups. (A) RT-qPCR analysis validated the expression levels of let-7a in the normal liver tissue and liver fibrosis tissue from mice. (B) The expression levels of let-7a in the blood samples from controls and model of liver fibrosis were compared. **P<0.01 compared with controls.

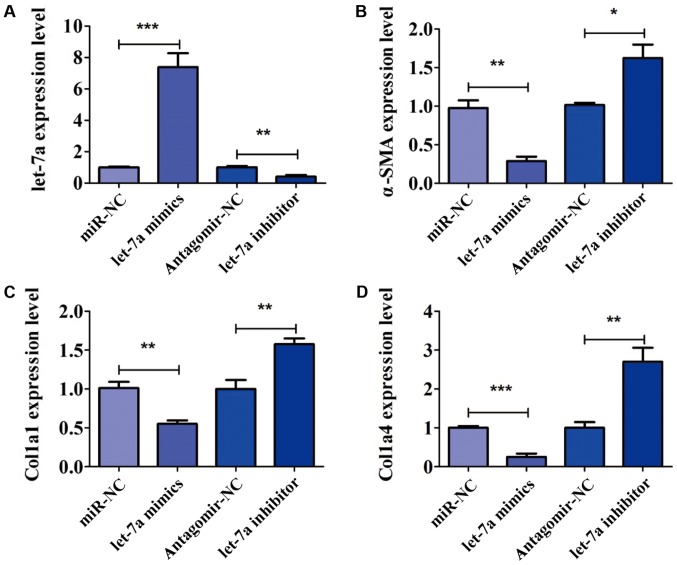

The role of let-7a in the activation of HSCs

To further confirm the role of let-7a in the activation of HSCs, LX-2 cells were transfected with let-7a mimics, let-7a inhibitor, miR-NC and antagomir-NC for 24 h. The expression of let-7a was detected by PCR analysis. The expression of let-7a was significantly increased after transfection of let-7a mimics, but decreased in the presence of let-7a inhibitor (Fig. 3A). After transfection, the expression of markers of HSC activation, including α-SMA, Col1a1 and Col1a4 was analyzed. We found that overexpression of let-7a significantly decreased the expression level of α-SMA, while the decrease in let-7a elevated the level of α-SMA (Fig. 3B). RT-qPCR assay indicated that LX-2 cells transfected with let-7a mimics decreased level of Col1a1, and the expression of Col1a1 was increased by transfection of let-7a inhibitor (Fig. 3C). In addition, the expression of Col1a4 was inhibited by let-7a mimics in comparison with miR-NC (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, the expression level of Col1a4 was higher in cells treated with let-7a inhibitor than that in group antagomir-NC (Fig. 3D). The above results confirmed that let-7a led to a marked decrease of HSC activation.

Figure 3.

let-7a decreases the activation of HSCs. To analyze the role of let-7a on the activation of HSCs, the cells were transfected with let-7a mimics, let-7a inhibitor, miR-NC and antagomir-NC for 24 h. After 24 h, the expression levels of liver fibrosis-related genes, including α-SMA, Col1a1 and Col1a4 were examined. (A) The transfection efficiency was detected by PCR analysis. (B) let-7a mimics reduced the expression level of α-SMA, while let-7a inhibitor accelerated the expression of α-SMA. (C) The effect of let-7a on the expression of Col1a1 was confirmed. (D) The expression of Col1a4 was lower in let-7a transfected cells than cells transfected with miR-NC. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 compared with controls.

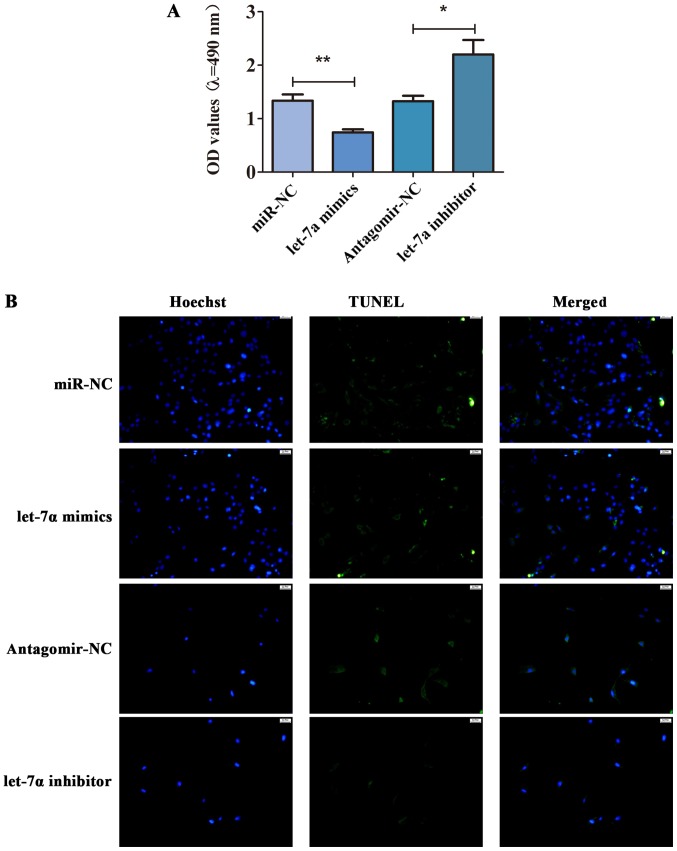

The effect of let-7a on cell viability and apoptosis of HSCs

To further study the role of let-7a in the cell viability and apoptosis of HSCs, MTT assay and TUNEL staining were performed. As shown in Fig. 4A, let-7a was overexpressed, and the cell viability was inhibited. Compared with antagomir-NC, the cell viability of HSCs transfected with let-7a inhibitor was enhanced (Fig. 4A). Besides, TUNEL staining displayed that let-7a promoted apoptosis of HSCs, while let-7a inhibitor decreased the apoptotic cells (Fig. 4B). These observations implied that let-7a inhibited the cell viability but promoted apoptosis in HSCs.

Figure 4.

let-7a regulates cell viability and apoptosis of HSCs. To study the effect of let-7a on cell viability and apoptosis of HSCs, the cells were transfected with let-7a mimics, let-7a inhibitor, miR-NC and antagomir-NC for 24 h. After 24 h, MTT and TUNEL assay were performed. (A) The effect of let-7a on cell viability of HSCs was determined by MTT assay. (B) The role of let-7a in apoptosis of HSCs was tested by TUNEL staining. *P<0.05; **P<0.01 compared with controls.

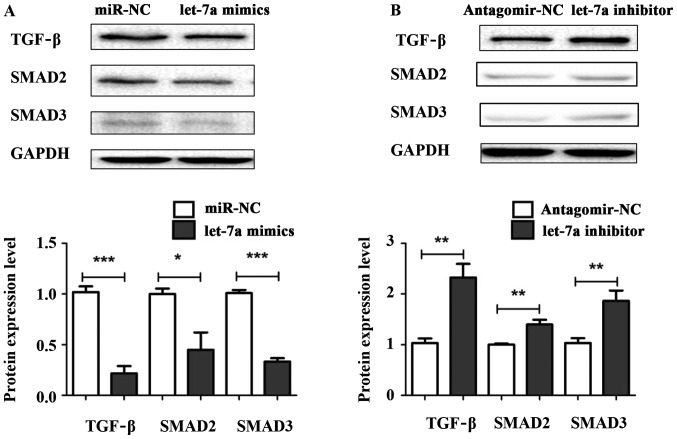

Let-7a suppresses liver fibrosis through TGF-β/SMAD signaling pathway

To explore the underlying mechanism of let-7a regulating liver fibrosis, let-7a mimics, let-7a inhibitor, miR-NC and antagomir-NC were transiently transfected into HSCs. The protein expression levels of TGF-β, SMAD2 and SMAD3 were measured by western blotting. The results showed that the expression levels of TGF-β, SMAD2 and SMAD3 were decreased in HSCs transfected with let-7a mimics compared with miR-NC (Fig. 5A). Conversely, the protein levels of TGF-β, SMAD2 and SMAD3 were significantly elevated in cells after transfection with let-7a inhibitor (Fig. 5B). Overall, our results indicate that let-7a may regulate the activation, cell viability and apoptosis of HSCs through TGF-β/SMAD signaling pathway.

Figure 5.

let-7a inhibites the protein expression of TGF-β/SMAD. To identify the mechanism of let-7a in HSCs, the protein expression levels of TGF-β, SMAD2 and SMAD3 were detected in the cells after transfection with let-7a. (A) Western blot analysis indicated that the expression levels of TGF-β, SMAD2 and SMAD3 were downregulated by let-7a mimics. (B) The expression levels of TGF-β, SMAD2 and SMAD3 were upregulated by let-7a inhibitor transfection. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 compared with controls.

Discussion

Fibrosis is a complicated process involving HSC activation, deposition of extracellular matrix and genetic and epigenetic changes including miRNA. Liver fibrosis is caused by viral hepatitis and alcoholic steatohepatitis, which leads to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (31,32). Emerging studies show that HSC is pivotal event in liver fibrosis (33,34). Therefore, in this study, our purpose is to investigate the role of let-7a in hepatic stellate cells and whether let-7a is dysregulated in the normal liver tissues and liver fibrosis.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a type of endogenous small non-coding RNAs, and microRNAs are related to the development of various diseases (35,36). miRNAs have been found to play a pro-fibrotic or anti-fibrotic role in HSC activation and be in connection with liver fibrosis. For example, miR-30a was downregulated in fibrotic liver tissues and isolated HSCs, and miR-30a suppresses HSC activation including cell proliferation, expression of α-SMA and collagen by targeting Snai1 protein (37). A study has shown that miR-185 suppressed fibrogenic activation of hepatic stellate cells by suppressing HSC activation through targeting RHEB and RICTOR. miR-212 promotes liver fibrosis via activating HSCs and TGF-β pathway through targeting SMAD7, which highlights that miR-212 can be regarded as a key biomarker or therapeutic target for liver fibrosis (38).

In this study, the results indicated that let-7a was markedly reduced in the liver tissues and blood samples from patients with liver fibrosis compared with healthy volunteers in clinic. In addition, the level of let-7a was decreased in liver tissues and blood samples in mice with liver fibrosis which were constructed by intraperitoneal injected with CCl4. Further analysis revealed that overexpression of let-7a decreased the mRNA level of markers of HSC activation, such as α-SMA, Col1a1 and Col1a4, suggesting that let-7a inhibited the activation level of HSCs. let-7a inhibitor increased the expression levels of these key genes, which were measured by RT-qPCR analysis. Besides, transfection of let-7a reduced cell viability and promoted apoptosis of HSCs. In contrast, let-7a inhibitor increased e cell viability and inhibited apoptosis of HSCs, which were in accordance with our hypothesis. Moreover, western blot analysis showed that let-7a might inhibit HSCs through TGFβ/SMAD signaling pathway. The present study provides new insights into the mechanisms behind the anti-fibrotic effect of let-7a. This study provided a potentially accurate target and vital evidence to better understand the underlying pathogenesis for early diagnosis and treatment of liver fibrosis.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding was received by Education Department of Heilongjiang Province General Program (12531788).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

YinghuiZ, YingboZ, JG, YL and KJ drafted the manuscript. YinghuiZ collected human blood samples. JG and YL helpedwith RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis. YinghuiZ and KJ performed PCR. YingboZ contributed to cell viability analysis. YinghuiZ and YingboZ wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Clinical Ethics Committee of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Qiqihar Medical University (Qiqihar, China). All participants agreed with the research, participated in this study willingly and signed an informed consent before sample collection.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.He X, Sun Y, Lei N, Fan X, Zhang C, Wang Y, Zheng K, Zhang D, Pan W. MicroRNA-351 promotes schistosomiasis-induced Liver fibrosis by targeting the vitamin D receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:180–185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715965115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao Q, Zhu X, Zhai X, Ji L, Cheng F, Zhu Y, Yu P, Zhou Y. Leptin suppresses microRNA-122 promoter activity by phosphorylation of foxO1 in hepatic stellate cell contributing to leptin promotion of mouse liver fibrosis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2018;339:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2017.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandel R, Saxena R, Das A, Kaur J. Association of rno-miR-183-96-182 cluster with diethyinitrosamine induced liver fibrosis in Wistar rats. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:4072–4084. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afonso MB, Rodrigues PM, Simão AL, Gaspar MM, Carvalho T, Borralho P, Bañales JM, Castro RE, Rodrigues CMP. miRNA-21 ablation protects against liver injury and necroptosis in cholestasis. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:857–872. doi: 10.1038/s41418-017-0019-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Ou Y, Dong J, Yang G, Zeng Z, Liu Y, Liu B, Li W, He X, Lan T. Osteopontin promotes collagen I synthesis in hepatic stellate cells by miRNA-129-5p inhibition. Exp Cell Res. 2018;362:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wan Y, McDaniel K, Wu N, Ramos-Lorenzo S, Glaser T, Venter J, Francis H, Kennedy L, Sato K, Zhou T, et al. Regulation of cellular senescence by miR-34a in alcoholic liver injury. Am J Pathol. 2017;187:2788–2798. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brea R, Motiño O, Francés D, García-Monzón C, Vargas J, Fernández-Velasco M, Boscá L, Casado M, Martín-Sanz P, Agra N. PGE2 induces apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells and attenuates liver fibrosis in mice by downregulating miR-23a-5p and miR-28a-5p. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2018;1864:325–337. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai Y, Huang G, Ma L, Dong L, Chen S, Shen X, Zhang S, Xue R, Sun D, Zhang S. Smurf2, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, interacts with PDE4B and attenuates liver fibrosis through miR-132 mediated CTGF inhibition. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2018;1865:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caviglia JM, Yan J, Jang MK, Gwak GY, Affo S, Yu L, Olinga P, Friedman RA, Chen X, Schwabe RF. MicroRNA-21 and Dicer are dispensable for hepatic stellate cell activation and the development of liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2018;67:2414–2429. doi: 10.1002/hep.29627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y, Yang S, Peng Y, Yang Z. The regulatory role of IL-6R in hepatitis B-associated fibrosis and cirrhosis. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2017;50:e6246. doi: 10.1590/1414-431x20176246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang N, Wu Y, Cao W, Liang Y, Gao Y, Hu L, Yang Q, Zhou Y, Tang F, Xiao J. Lentivirus-mediated over-expression of let-7b microRNA suppresses Liver fibrosis in the mouse infected with Schistosoma japonicum. Exp Parasitol. 2017;182:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2017.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen W, Zhao W, Yang A, Xu A, Wang H, Cong M, Liu T, Wang P, You H. Integrated analysis of microRNA and gene expression profiles reveals a functional regulatory module associated with liver fibrosis. Gene. 2017;636:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma X, Luo Q, Zhu H, Liu X, Dong Z, Zhang K, Zou Y, Wu J, Ge J, Sun A. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 activation ameliorates CCl4-induced chronic liver fibrosis in mice by up-regulating Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidant pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22:3965–3978. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang XC, Gusdon AM, Liu H, Qu S. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and inflammation. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:14821–14830. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i40.14821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel V, Joharapurkar A, Kshirsagar S, Sutariya B, Patel M, Patel H, Pandey D, Patel D, Ranvir R, Kadam S, et al. Coagonist of GLP-1 and glucagon receptor ameliorates development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2018;16:35–43. doi: 10.2174/1871525716666180118152158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ye Y, Li Z, Feng Q, Chen Z, Wu Z, Wang J, Ye X, Zhang D, Liu L, Gao W, et al. Downregulation of microRNA-145 may contribute to liver fibrosis in biliary atresia by targeting ADD3. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0180896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng GX, Li J, Yang Z, Zhang SQ, Liu YX, Zhang WY, Ye LH, Zhang XD. Hepatitis B virus X protein promotes the development of liver fibrosis and hepatoma through downregulation of miR-30e targeting P4HA2 mRNA. Oncogene. 2017;36:6895–6905. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tao R, Fan XX, Yu HJ, Ai G, Zhang HY, Kong HY, Song QQ, Huang Y, Huang JQ, Ning Q. MicroRNA-29b-3p prevents Schistosoma japonicum-induced liver fibrosis by targeting COL1A1 and COL3A1. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:3199–3209. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen J, Yu Y, Li S, Liu Y, Zhou S, Cao S, Yin J, Li G. MicroRNA-30a ameliorates Liver fibrosis by inhibiting Beclin1-mediated autophagy. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:3679–3692. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun J, Zhang H, Li L, Yu L, Fu L. MicroRNA-9 limits Liver fibrosis by suppressing the activation and proliferation of hepatic stellate cells by directly targeting MRP1/ABCC1. Oncol Rep. 2017;37:1698–1706. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schueller F, Roy S, Loosen SH, Alder J, Koppe C, Schneider AT, Wandrer F, Bantel H, Vucur M, Mi QS, et al. miR-223 represents a biomarker in acute and chronic liver injury. Clin Sci (Lond) 2017;131:1971–1987. doi: 10.1042/CS20170218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Demerdash HM, Hussien HM, Hassouna E, Arida EA. Detection of microRNA in hepatic cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis C genotype-4 in Egyptian patients. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:1806069. doi: 10.1155/2017/1806069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fittipaldi S, Vasuri F, Bonora S, Degiovanni A, Santandrea G, Cucchetti A, Gramantieri L, Bolondi L, D'Errico A. miRNA signature of hepatocellular carcinoma vascularization: How the controls can influence the signature. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:2397–2407. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4654-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu N, Meng F, Zhou T, Han Y, Kennedy L, Venter J, Francis H, DeMorrow S, Onori P, Invernizzi P, et al. Prolonged darkness reduces liver fibrosis in a mouse model of primary sclerosing cholangitis by miR-200b down-regulation. FASEB J. 2017;31:4305–4324. doi: 10.1096/fj.201700097R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sene LB, Rizzi VHG, Gontijo JAR, Boer PA. Gestational low-protein intake enhances whole-kidney miR-192 and miR-200 family expression and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in rat adult male offspring. J Exp Biol. 2018;221:221. doi: 10.1242/jeb.171694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu Y, Liu Y, Pan Y, Lu C, Xu H, Wang X, Liu T, Feng K, Tang Y. MicroRNA-135a inhibits cardiac fibrosis induced by isoproterenol via TRPM7 channel. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;104:252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.04.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glasgow AMA, De Santi C, Greene CM. Non-coding RNA in cystic fibrosis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2018;46:619–630. doi: 10.1042/BST20170469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miao C, Xiong Y, Zhang G, Chang J. MicroRNAs in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, new research progress and their pathophysiological implication. Exp Lung Res. 2018;44:178–190. doi: 10.1080/01902148.2018.1455927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai CY, Lin CY, Hsu CC, Yeh KY, Her GM. Liver-directed microRNA-7a depletion induces nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by stabilizing YY1-mediated lipogenic pathways in zebrafish. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2018;1863:844–856. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2018.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watany MM, Hagag RY, Okda HI. Circulating miR-21, miR-210 and miR-146a as potential biomarkers to differentiate acute tubular necrosis from hepatorenal syndrome in patients with liver cirrhosis: A pilot study. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2018;56:739–747. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2017-0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi SQ, Ke JJ, Xu QS, Wu WQ, Wan YY. Integrated network analysis to identify the key genes, transcription factors, and microRNAs involved in hepatocellular carcinoma. Neoplasma. 2018;65:66–74. doi: 10.4149/neo_2018_161215N642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schueller F, Roy S, Vucur M, Trautwein C, Luedde T, Roderburg C. The role of miRNAs in the pathophysiology of liver diseases and toxicity. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:19. doi: 10.3390/ijms19010261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin YC, Wang FS, Yang YL, Chuang YT, Huang YH. MicroRNA-29a mitigation of toll-like receptor 2 and 4 signaling and alleviation of obstructive jaundice-induced fibrosis in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;496:880–886. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.01.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Austermann C, Schierwagen R, Mohr R, Anadol E, Klein S, Pohlmann A, Jansen C, Strassburg CP, Schwarze-Zander C, Boesecke C, et al. microRNA-200a: A stage-dependent biomarker and predictor of steatosis and liver cell injury in human immunodeficiency virus patients. Hepatol Commun. 2017;1:36–45. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu W, Wang Y, Zhang D, Yu X, Leng X. MiR-7-5p functions as a tumor suppressor by targeting SOX18 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;497:963–970. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng J, Wang W, Yu F, Dong P, Chen B, Zhou MT. MicroRNA-30a suppresses the activation of hepatic stellate cells by inhibiting epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;46:82–92. doi: 10.1159/000488411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu J, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Li W, Zheng W, Yu J, Wang B, Chen L, Zhuo Q, Chen L, et al. MicroRNA-212 activates hepatic stellate cells and promotes liver fibrosis via targeting SMAD7. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;496:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.